Abstract

This study evaluated a bench-scale side-stream bio-electrochemical anaerobic digestion (SBEAD) system for rapid reactivation of deteriorated food-waste anaerobic digestion (AD) and benchmarked it against internal-electrode bio-electrochemical AD (BEAD). At an organic loading rate (OLR) of 4.0 kg-COD/m3/d, AD deteriorated (Volatile fatty acids (VFAs) > 6000 mg/L and a pH drop) and methane yield declined to 0.12 L-CH4/g-COD. In contrast, BEAD maintained performance at the same OLR, sustaining a methane yield of 0.25 ± 0.02 L-CH4/g-COD and a COD removal of 77.3 ± 4.5%. Within 20 days of converting the deteriorated AD into SBEAD, VFAs decreased to 4387 mg/L and pH recovered from 6.61 to 7.35, while COD removal and methane yield increased to 64.8% and 0.21 L-CH4/g-COD. At OLR 7.0 kg-COD/m3/d, SBEAD sustained high performance (COD removal 75.2 ± 3.6%, methane yield 0.25 ± 0.01 L-CH4/g-COD), whereas BEAD deteriorated with impaired internal mixing (VFAs 9500 mg/L, pH < 6.39, COD removal 44.0% and methane yield 0.11 L-CH4/g-COD). Despite additional recirculation energy, higher OLR tolerance may reduce required digester volume and capital cost, thereby improving overall cost efficiency. Future development and validation of operational strategies are expected to further improve the practicality and efficiency of the SBEAD system for full-scale implementation.

1. Introduction

Anaerobic digestion (AD) is a carbon-neutral technology that converts organic waste into biogas for energy recovery and waste reduction [1,2,3,4]. It has been widely applied in wastewater treatment plants, livestock wastewater facilities, and food waste treatment systems [5,6,7]. Among these organic waste streams, food waste is widely recognized as one of the most common constituents of household waste [8]. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Food Waste Index Report, approximately 1.05 billion tonnes of food waste is generated globally each year [9]. The report further indicates that food waste is managed through routes including landfilling, composting, and anaerobic digestion. While composting and landfilling are common management routes, they provide limited direct energy recovery and may be associated with environmental burdens (e.g., fugitive greenhouse-gas emissions), thereby supporting the relevance of controlled treatment options such as anaerobic digestion.

However, process instability frequently occurs when highly biodegradable organic waste, such as food waste, flows into the AD reactor. As a highly biodegradable organic waste, food waste accelerates hydrolysis and acidogenesis reactions, resulting in a quick accumulation of hydrogen ions (H+) and volatile fatty acids (VFAs) in the AD reactor. These negative factors reduce methanogenic activity and cause acidification of the inside of the AD reactor, leading to decreased biogas production and a higher risk of process failure [5,10,11,12]. To improve process stability and overcome these limitations of conventional AD of food waste, several strategies, such as two-stage anaerobic digestion and co-digestion, have been proposed [13,14]. However, these approaches generally require increased operational complexity or careful substrate balancing and still exhibit limited ability to directly stabilize methanogenic activity under high organic loading conditions. Thus, strategies that can rapidly reactivate methanogenesis and stabilize deteriorated food-waste AD are of practical interest.

In this context, bio-electrochemical anaerobic digestion (BEAD) has recently gained great attention as an innovative approach to enhance the performance and stability of the AD. The BEAD integrates a microbial electrolysis cell (MEC) with AD, where the application of a low external voltage stimulates electroactive microbial activity, accelerates substrate degradation, and improves methane production and process stability [15,16,17]. Several studies have reported that the BEAD can suppress the accumulation of H+ and VFAs and maintain microbial activity, even under unstable operating conditions [18,19,20]. As a result, BEAD can sustain biogas production and enhance the overall stability and performance of the AD process [21,22,23]. These electro-stimulated effects further suggest that BEAD-derived configurations may function not only as a preventive measure but also as a reactivation tool that accelerates recovery of methane production and key stability indicators after process deterioration. Despite these advantages of the BEAD, conventional BEAD reactors still face several limitations in the practical commercialization and full-scale application. Conventional BEAD reactors are typically designed with electrodes installed inside the digester, which can lead to spatial constraints for electrode installation and difficulty in maintenance, as well as mixing disturbance and limited mass transfer in full-scale processes [24,25]. For these reasons, the performance of BEAD has been verified mainly at the laboratory-scale [17,21,26], while studies on its long-term and larger-scale application to high loading and unstable substrates, such as food waste, remain limited.

Recently, a side-stream bio-electrochemical anaerobic digestion (SBEAD) system, comprising a main AD reactor coupled with an external side-stream bio-electrochemical module, has been proposed to overcome limitations of conventional BEAD reactors. In this configuration, bio-electrochemical reactions are spatially separated from the main AD reactor, and the side-stream module is hydraulically connected to the reactor via a recirculation loop. Electro-activated sludge is continuously circulated between the module and the main reactor, allowing the bio-electrochemical effects to influence overall digestion performance [27,28]. In addition, this module-based design facilitated operation and maintenance by isolating electrodes and electrochemical components from the main reactor. However, studies specifically focusing on SBEAD remained scarce, and existing investigations had largely been confined to laboratory-scale systems, with limited evaluation at larger reactor volumes. This gap was particularly critical because internal-electrode BEAD could face scale-up-relevant operational constraints as reactor volume increased, highlighting the need to evaluate side-stream configurations as a practical alternative.

Accordingly, this study aimed to demonstrate the feasibility of SBEAD at a larger, bench scale as a practical strategy for strengthening food-waste AD, while assessing scale-up-relevant limitations associated with internal-electrode BEAD. Under stepwise increases in organic loading rate (OLR), conventional AD and internal-electrode BEAD were first evaluated to capture deterioration trends under high loading. Subsequently, the AD reactor was converted to an SBEAD system by coupling an external side-stream module, and process resilience was evaluated. Finally, the performance of SBEAD was compared with that of internal-electrode BEAD, and the extent to which the side-stream configuration could mitigate key scale-up limitations inherent to internal-electrode designs was assessed, thereby indicating its potential as a practical operational strategy for food-waste AD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Configuration of Reactors and Equipment

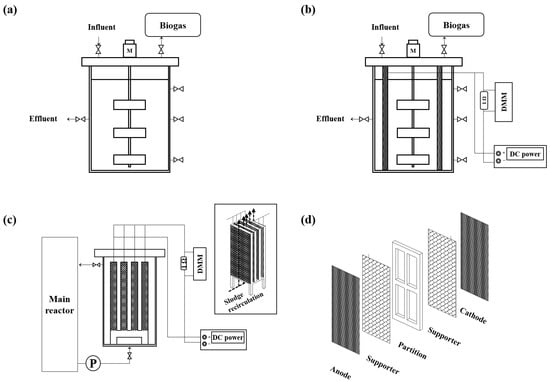

The configurations of the AD and BEAD and SBEAD setups, along with the side-stream module and electrode stacks, are illustrated in Figure 1. Both the AD and BEAD reactors had a working volume of 100 L and were constructed from transparent acrylic in a cylindrical shape, measuring 50 cm in diameter and 60 cm in height. Each reactor was equipped with a centrally mounted impeller to ensure homogeneous mixing. In the BEAD reactor, the electrode stacks were installed directly inside the main reactor. In contrast, the SBEAD system employed an external side-stream module that was physically separated from the main AD reactor. The external side-stream module, also made of transparent acrylic, had a rectangular column shape (10 cm × 10 cm × 80 cm) and was fitted with inlet and outlet valves. These valves facilitated the circulation of bulk sludge between the AD reactor and the external side-stream module via a pump. The external side-stream module had a working volume of 6 L, and the total effective volume of the SBEAD system, including the module, was maintained at 100 L, identical to the AD and BEAD reactors. The power consumption of this circulation pump was monitored using a digital power meter (SK-302G, SKM Electronics, Busan, Republic of Korea) connected to the pump controller. Each electrode stack used in both the BEAD reactor and the side-stream module consisted of an anode-supporter-partition-supporter-cathode configuration. The anode and cathode were made of carbon cloth, while stainless-steel mesh supporters held the electrodes in place. In the BEAD reactor, two sets of electrode stacks were installed, providing a total electrode surface area of 0.72 m2. Similarly, the side-stream module contained four smaller electrode stacks, resulting in the same total electrode surface area as that of the BEAD reactor. All electrode stacks were connected to a DC power supply (2230-30-1 Triple Channel, Keithley Instruments, Cleveland, OH, USA) for bio-electrochemical stimulation and to a digital multimeter (DMM) (2701 Ethernet-based DMM, Keithley Instruments, Cleveland, OH, USA) for current monitoring. The biogas generated from the reactors was collected using a Tedlar bag (CEL Scientific Corp., Santa Fe Springs, CA, USA).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of (a) anaerobic digestion reactor, (b) bio-electrochemical anaerobic digestion reactor, (c) side-stream bio-electrochemical anaerobic digestion system, and (d) electrode stack.

2.2. Inoculum and Substrate

The inoculum and food waste used in this study were collected from a food waste recycling facility located in Cheongju, Republic of Korea. The inoculum consisted of anaerobic digested sludge obtained from a mesophilic AD reactor. Prior to use, both the inoculum and food waste were screened (2 mm) to remove coarse impurities and inert materials. The inoculum was then added to the reactors for start-up, and the processed food waste was stored at 4 °C prior to feeding to minimize degradation. The physicochemical characteristics of the inoculum and food waste are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of inoculum and food waste.

2.3. Sequencing Batch Reactor Operation

The experimental design was conducted in stages using two parallel reactors. During the initial steps (Steps 1–3), a conventional AD reactor and a BEAD reactor were operated simultaneously. The initial pH of both reactors was approximately 7.5 at the start of operation. In the BEAD reactor, a constant voltage of 0.4 V was applied to the internal electrodes throughout the operation. The OLR was initially set at 2 kg-COD/m3/d and was progressively increased stepwise to evaluate process performance. At Step 3, process instability was observed in the AD reactor under increased OLR conditions. In response, the AD reactor was converted to a SBEAD system by implementing an external side-stream bio-electrochemical module. During this period, bulk sludge was recirculated from the AD reactor to the side-stream module at a flow rate of 300 L/d, and the electrodes installed in the side-stream module were supplied with the same voltage (0.4 V) as that applied to the BEAD reactor. Subsequently, the SBEAD system and the BEAD reactor were operated in parallel, and the OLR was further increased stepwise up to 7 kg-COD/m3/d to assess process stability and performance under higher loading conditions. All reactors were operated under mesophilic conditions in a temperature-controlled chamber maintained at 35.0 ± 2.0 °C throughout the experimental period. The operational conditions are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Operational conditions of each configuration at each step.

2.4. Analysis Methods

The pH was measured using a pH meter (Orion 420+, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The total chemical oxygen demand (TCOD) of the effluent from each reactor was analyzed using the closed reflux and colorimetric method [29]. VFAs, including acetate, propionate, and butyrate, were quantified using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, YL 9100, Young-Lin Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea). Biogas production was quantified using a mass flow meter (KMF-20, KEMIK Corporation, Seongnam-si, Republic of Korea) at 24 h intervals. Methane composition in biogas was analyzed using gas chromatography (GC, Series 580, GOW-MAC, Bethlehem, PA, USA) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector. Because this study was conducted as a single long-term run, replicate experimental runs were not performed; therefore, the reported mean ± standard deviation represents temporal variability within each operational step rather than between-run variability. In addition, to enable consistent comparisons across variables monitored at different frequencies (e.g., current density recorded at 10 min intervals, pH measured daily, and other parameters analyzed three times per week), datasets were time-aligned prior to statistical analysis. In the case of the SBEAD system, only data obtained after process recovery were used for Step 4. Descriptive statistics (mean ± standard deviation) were calculated using Microsoft Excel 2016 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA)

2.5. Calculation

Methane production was normalized to standard conditions using the ideal gas law, as expressed in Equation (1):

where Vbiogas is the measured biogas volume (L), MCH4 is the methane content in the biogas (%), T and P are the temperature (K) and pressure (atm) at standard (T1 and P1) and operational conditions (T2 and P2), respectively.

The Current density was calculated based on the current values measured during the operation period, as shown in Equation (2):

where I is the current (A), A is the total electrode surface area (m2). The calculations followed the methods described by Park et al. [11]

Coefficient of Variation (CoV) was calculated from the TS measured in sludge samples collected from the top, middle, and bottom sections to evaluate the mixing uniformity inside the reactors, as shown in Equation (3):

where TSi and TSavg are the TS concentrations (mg/L) at each sampling position and their average value, respectively. n is the number of samples.

The net energy recovery was calculated as the difference between the energy produced from methane, the electrical energy consumed by the bio-electrochemical system and the pump energy consumption, as expressed in Equation (4):

where WCH4 is the methane energy recovery (kJ), calculated using methane production (L) and the Gibbs free energy change in methane combustion (−818 kJ/mol). WE is the electrical energy consumed by the voltage supply (kJ), obtained by multiplying the measured current (A) from the DMM by the applied voltage (0.4 V) and the measurement interval (600 s). Wpump is the energy consumed by the sludge circulation pump (kJ), determined from the power values recorded by the digital power meter. CODinf is the amount of substrate fed at each operating step (g-COD). To evaluate the energy recovery from a system perspective, the total COD fed was used rather than the COD removed. In calculating the net energy recovery, the common energy consumption for mechanical mixing and heating was excluded from all three reactors.

Lastly, the construction cost was estimated under practical installation conditions based on the components and unit prices described in Table 3, which were referenced from the study by Xie et al. [25].

Table 3.

Components and unit prices used for construction cost estimation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Performance Comparison Between AD and BEAD Under Moderate OLRs

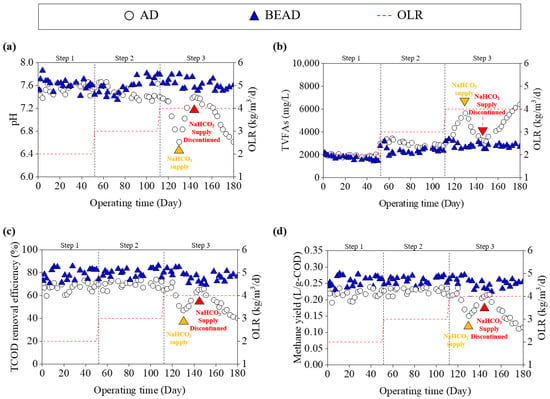

Figure 2 presents the performance comparison between the AD and BEAD reactors under varying OLRs. During Steps 1 and 2, both reactors performance. The pH values were 7.54 ± 0.08 and 7.49 ± 0.11 for the AD reactor, and 7.62 ± 0.09 and 7.58 ± 0.14 for the BEAD reactor. Furthermore, Figure 2b indicates that both reactors operated without VFA accumulation. Among the VFAs quantified, acetate, propionate, and butyrate were detected at low concentrations and no notable differences were observed between the AD and BEAD reactors (Figure S1). In contrast, the COD removal efficiency of the BEAD reactor was 79.0 ± 4.9% and 80.1 ± 3.6% in Steps 1 and 2, respectively, while the AD reactor achieved efficiencies of 67.1 ± 8.9% and 70.1 ± 3.0%. Consequently, the methane yield of the BEAD reactor was recorded at 0.26 ± 0.02 L-CH4/g-COD and 0.26 ± 0.01 L-CH4/g-COD, representing increases of 18.6% and 14.0%, respectively, compared to the AD reactor. The methane content 62.8 ± 6.7% and 58.9 ± 3.8% for AD reactor, whereas the BEAD reactor exhibited values of 63.1 ± 7.2% and 64.3 ± 2.2% during the same steps (Figure S2). Previous studies have indicated that bio-electrochemical systems often exhibit higher organic removal efficiency and enhanced methane yields compared to conventional anaerobic digestion, even under conditions where pH and VFA concentrations remain comparable [17,30,31]. This enhancement suggests that bio-electrochemical stimulation may improve the conversion efficiency of organic substrates, allowing higher COD removal and methane production.

Figure 2.

Variations in (a) pH, (b) volatile fatty acids, (c) chemical oxygen demand removal efficiency, and (d) methane yield of anaerobic digetion and bio-electrochemical anaerobic digestion reactors under different organic loading rates.

However, at Step 3, the AD reactor experienced process instability. VFAs rapidly accumulated to 5647 mg/L, and the pH dropped to 6.61. In Step 3, VFAs increased mainly in the form of acetate and propionate. Consequently, both the COD removal efficiency and methane yield decreased by 32.8% and 34.8%, respectively, compared to Step 2. In addition, the methane content decreased to 42.6%, indicating a deterioration in biogas quality under these conditions. Previous studies have shown that while the OLR at which AD systems fail can vary, VFA accumulation and pH reduction are consistently observed when the OLR exceeds a certain threshold, leading to decreases in COD removal efficiency and methane yield, ultimately resulting in process failure [32,33]. To mitigate rapid VFA accumulation and the associated pH decline, NaHCO3 was temporarily supplied on Day 130, resulting in a transient recovery of reactor performance. However, this improvement was not sustained after alkalinity supplementation was discontinued on Day 147, suggesting that external buffering provides only conditional mitigation. Consistently, Jiang et al. (2012) reported that pH decline under high loading could not be effectively controlled by alkali additions and that bicarbonate supplementation showed no sustainable beneficial effect [34]. In contrast, the BEAD reactor maintained operation without significant VFA accumulation or pH decrease. Previous studies have reported that bio-electrochemical stimulation can enhance anaerobic digestion performance by facilitating electron transfer processes and improving resistance to upset under elevated loading conditions [20,35]. In particular, enhanced conversion of acetate and propionate, leading to reduced VFA accumulation, has been observed in bio-electrochemical systems [36]. The suppressed VFA accumulation observed in the BEAD reactor in this study are consistent with these previously reported findings. As a result, these differences in VFA accumulation were reflected in the overall digestion performance of the BEAD reactor. The COD removal efficiency and methane yield of the BEAD reactor were measured at 77.3 ± 4.5% and 0.25 ± 0.02 L-CH4/g-COD, respectively, which were comparable to those in Steps 1 and 2. The methane yield obtained in this study was within the range reported in previous studies [36,37,38], and was of a similar order to methane yields reported for other AD-enhancement strategies for food waste (e.g., conductive additive–amended AD or two-stage AD) [39,40]. Beyond methane yield, previous studies have also reported that the BEAD system outperformed conventional AD systems at higher OLRs and could be operated stably at OLRs of up to 14–20 kg-COD/m3/d [27,41]. This finding suggests that the BEAD system could serve as a promising alternative to address the limitations of conventional AD systems.

3.2. Evaluation of AD Performance Recovery via a Side-Stream Module

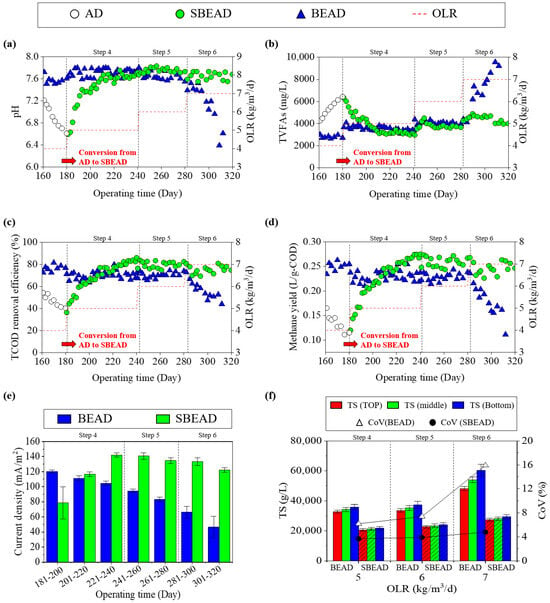

Figure 3 presents a performance comparison between the BEAD and SBEAD reactors following the implementation of the side-stream module. After the onset of process instability in the AD reactor, bio-electrochemical stimulation was applied to the bulk sludge via the side-stream module using a recirculation pump and a DC power supply. Under these conditions, the SBEAD reactor exhibited a gradual recovery of digestion performance over a period of approximately 20 days, consistent with previous studies on indirect bio-electrochemical stimulation via a side-stream module [28]. The accumulated VFAs rapidly decreased to 4387 mg/L, and the pH recovered from 6.61 to 7.35, remaining within an optimal range. Consequently, the COD removal efficiency increased from 40.4% to 64.8%, while the methane yield rose from 0.12 L-CH4/g-COD to 0.21 L-CH4/g-COD. In parallel, the methane content recovered from 42.6% to 63.4%. As the SBEAD reactor recovered, the organic loading rate was gradually increased in steps to compare its efficiency with that of the BEAD reactor. After the recovery at Step 4, the SBEAD reactor demonstrated slightly higher COD removal efficiency and methane yield (76.8 ± 6.1% and 0.25 ± 0.02 L-CH4/g-COD) compared to the BEAD reactor (70.3 ± 3.8% and 0.23 ± 0.01 L-CH4/g-COD). This trend continued into Step 5, where the COD removal efficiency and methane yield of the SBEAD reactor were 79.8 ± 2.9% and 0.26 ± 0.01 L-CH4/g-COD, respectively, while those of the BEAD reactor were 70.2 ± 2.6% and 0.23 ± 0.01 L-CH4/g-COD. Previous studies have suggested that the enhanced performance of the SBEAD system may be associated with indirect enhancement of bio-electrochemical activity in the bulk sludge, through recirculation of electro-activated sludge exposed to an externally applied voltage in the side-stream module [27,28]. Consistent with this interpretation, the pronounced VFA reduction and pH recovery observed in this study suggested that indirect bio-electrochemical stimulation via sludge recirculation accelerated bulk-phase VFA conversion and improved pH stability, thereby mitigating acidification under high-loading stress.

Figure 3.

Variations in (a) pH, (b) volatile fatty acids, (c) chemical oxygen demand removal efficiency, (d) methane yield, (e) average current density, and (f) coefficient of variation in the side-stream bio-electrochemical anaerobic digestion system and bio-electrochemical anaerobic digestion reactor under different organic loading rates.

As operations progressed to Step 6, a distinct difference emerged between the SBEAD and BEAD reactors. In the BEAD reactor, VFAs accumulated to 9500 mg/L, and the pH dropped to below 6.39. Consequently, both the COD removal efficiency and methane yield sharply declined to 44.0% and 0.11 L-CH4/g-COD, respectively, accompanied by a pronounced decrease in methane content to its lowest observed value of 41.9%. In contrast, the SBEAD reactor experienced only a slight increase in VFA concentration to 4416 ± 306 mg/L, accompanied by a pH remained at 7.65 ± 0.07, which remained within a typical operating range. The COD removal efficiency and methane yield of the SBEAD reactor were 75.2 ± 3.6% and 0.25 ± 0.01 L-CH4/g-COD, respectively, indicating robust operation with only a minor reduction in digestion efficiency. As shown in Figure 3e, despite both systems employing electrodes of identical material and total surface area, the current density in the SBEAD system remained relatively constant during the operational period (121.9 mA/m2 at Day 301–320), whereas that in the BEAD system gradually decreased to 46.6 mA/m2 over the same period. Such a reduction in current density in BEAD systems may be influenced by factors such as increased internal resistance and limitations in mass transfer, which can restrict effective electron transport under the given operating conditions [42,43]. Figure 3f indicates relatively non-uniform mixing in the BEAD system, which is consistent with the observed reduction in current density. The coefficients of variation (CoV), calculated based on TS measured at the top, middle, and bottom sections of the reactor, were 3.7% and 3.9% for the SBEAD system at Steps 4 and 5, respectively. In contrast, the CoV values for the BEAD system were higher, at 6.2% and 7.4% during the same steps. This disparity became more pronounced at Step 6, where the CoV increased to 4.8% in the SBEAD system and 15.9% in the BEAD system, indicating relatively non-uniform mixing in the BEAD system. Previous studies have also demonstrated that increased mixing intensity improves mass transfer, thereby enhancing current density [44]. From an operational perspective, these findings suggest that incorporating a side-stream module can serve as an effective strategy to enhance process robustness and resilience against shock loading in AD systems, potentially alleviating limitations of BEAD configurations that may become more pronounced as reactor volume increases.

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Performance, Energy Efficiency, and Economic Feasibility Among Systems

Table 4 summarizes the overall performance comparison among the AD and BEAD reactors and the SBEAD systems. Throughout the operational period, the three systems exhibited distinct responses to increasing OLRs, which may be associated with differences in process stability, electrochemical stimulation, and mass transfer characteristics. Briefly, the AD reactor exhibited process instability at Step 3 due to VFA accumulation, whereas the BEAD reactor maintained stable performance up to Step 5 through bio-electrochemical stimulation but became unstable at Step 6. In contrast, the SBEAD system demonstrated improved process stability and mixing uniformity under elevated loading conditions. These differences in operational performance provide the basis for the comparative evaluation of energy efficiency among the three configurations.

Table 4.

Comparative summary of performances for each configuration.

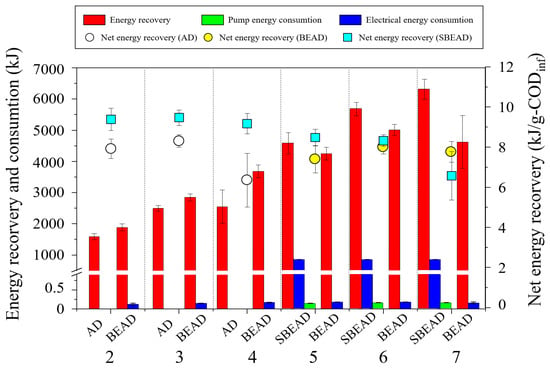

The energy balance for each configurations is illustrated in Figure 4. The AD reactor demonstrated net energy recoveries of 7.94 and 8.33 kJ/g-CODinf at Steps 1 and 2, respectively, but this value decreased to 6.33 kJ/g-CODinf at Step 3 due to an overall decline in process efficiency under higher OLR conditions. The BEAD reactor showed recoveries of 9.41 and 9.49 kJ/g-CODinf at Steps 1 and 2, respectively. The increases in energy recovery (295 and 349 kJ) were significantly greater than the electrical energy consumption (0.15 and 0.17 kJ), leading to an overall increase in net energy recovery. These results highlight the BEAD reactor’s advantages in terms of energy recovery efficiency. However, as operations progressed, the BEAD reactor experienced a gradual decline in net energy recovery, dropping to 8.50 kJ/g-CODinf and 8.35 kJ/g-CODinf at Steps 4 and 5, and further decreasing to 6.60 kJ/g-CODinf at Step 6, a level similar to that observed when the AD reactor became unstable. The SBEAD system achieved recoveries of 7.43 kJ/g-CODinf and 8.03 kJ/g-CODinf at steps 4 and 5, with higher gross energy recoveries than the BEAD reactor (331 and 670 kJ). However, although its electrical energy consumption was comparable to that of the BEAD reactor, the additional pump energy consumption (864 kJ) offset this advantage, resulting in lower net energy recovery. At Step 6, the SBEAD system exhibited a recovery of 7.79 kJ/g-CODinf. Even when the BEAD reactor failed and the energy consumption gap between the BEAD reactor and SBEAD system widened to 1693 kJ, the SBEAD system still demonstrated lower net energy recovery than the AD reactor. Consequently, the application of the side-stream module may be considered energetically disadvantageous, necessitating strategies to overcome this limitation. Although not investigated in this study, potential approaches could include replacing conventional mechanical mixing with sludge recirculation. Additionally, inspired by the immediate recovery in process stability and efficiency observed during module operation, the module could be operated intermittently, only when process instability occurs. Verification of these strategies in future studies could further enhance the practicality and overall energy efficiency of the SBEAD system.

Figure 4.

Comparison of net energy recovery and energy balance of the anaerobic digestion reactor, the bio-electrochemical anaerobic digestion reactor and the side-stream bio-electrochemical anaerobic digestion system.

While the SBEAD system exhibited lower net energy recovery due to additional energy consumption, it offered a clear advantage in terms of construction costs. A higher allowable OLR enables treatment of the same organic loading with a smaller reactor volume, thereby reducing overall construction requirements. To evaluate this aspect, preliminary cost estimation was conducted assuming a COD treatment capacity of 100 tons per day, with the results summarized in Table 5. The estimated total construction costs were USD 20,838,667 for the AD, USD 13,694,133 for the BEAD, and USD 12,259,129 for the SBEAD, indicating that the SBEAD system required the lowest construction investment among the three configurations. Although the SBEAD system requires additional auxiliary components such as pumps and pipelines, these costs were more than compensated by the smaller reactor volume required to treat the same organic loading, enabled by its higher allowable OLR, resulting in an overall reduction in capital expenditure. Beyond capital cost considerations, the side-stream configuration offers additional operational advantages by isolating electrochemical components from the main digester, thereby facilitating maintenance and reducing the risk of long-term performance deterioration. Taken together, these characteristics indicate that the SBEAD system provides a balanced trade-off among process stability, constructability, and operational robustness, supporting its potential for high-load anaerobic digestion. Nevertheless, before full-scale implementation, further studies are required to optimize operating conditions and to conduct pilot-scale commissioning with long-term operation to validate field reliability and lifecycle performance.

Table 5.

Estimated construction cost for each configuration.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically compared the performance of AD and BEAD reactors, and SBEAD systems under varying organic loading conditions. The results demonstrated that bio-electrochemical stimulation enhanced process stability and methane production compared with the AD reactor, particularly under elevated loading conditions. The integration of a side-stream module further improved mixing uniformity and operational robustness, mitigating operational limitations observed in the internal-electrode BEAD reactor. Despite these advantages, several limitations should be noted. First, this work was conducted at a bench scale under controlled conditions; therefore, the long-term stability and operability of SBEAD under realistic full-scale variability remain to be validated. Second, although SBEAD improved robustness under high loading, further optimization is required to reduce recirculation-related energy demand and to identify optimal operating windows (e.g., recirculation ratio, applied voltage, and module hydraulic conditions) for maximizing net energy recovery.

From a practical perspective, key current challenges for SBEAD implementation include reducing recirculation energy demand while maintaining sufficient bioelectrochemical stimulation, and establishing robust operating windows (e.g., recirculation ratio, module HRT, and applied voltage) under variable food-waste characteristics. Future research should focus on optimizing operational strategies (e.g., intermittent recirculation/voltage application, energy-efficient mixing alternatives, and advanced process control) and validating the system at pilot/full scale with longer operation periods to confirm durability, net-energy benefits, and economic feasibility under realistic operating conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/en19010160/s1. Figure S1. Volatile fatty acid composition of (a) anaerobic digestion reactor, (b) bio-electrochemical anaerobic digestion reactor, and (c) side-stream bio-electrochemical anaerobic digestion system under different organic loading rates. Figure S2. Variations in methane content of anaerobic digestion reactor, bio-electrochemical anaerobic digestion reactor, and side-stream bio-electrochemical anaerobic digestion system under different organic loading rates.

Author Contributions

H.Y.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, review and editing, visualization. S.J.: validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing—review and editing, visualization. J.P.: validation, writing—review and editing. H.J.: conceptualization, validation, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was conducted during the research year of Chungbuk National University in 2024 and was supported by Chosun University in 2025 (Grant No.: K208702005).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Styles, D.; Yesufu, J.; Bowman, M.; Prysor Williams, A.; Duffy, C.; Luyckx, K. Climate mitigation efficacy of anaerobic digestion in a decarbonising economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 338, 130441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbarao, P.M.; D’Silva, T.C.; Adlak, K.; Kumar, S.; Chandra, R.; Vijay, V.K. Anaerobic digestion as a sustainable technology for efficiently utilizing biomass in the context of carbon neutrality and circular economy. Environ. Res. 2023, 234, 116286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, E.; Li, X.; Cui, X.; Guo, J.; Dong, R. Potential biomethane production from crop residues in China: Contributions to carbon neutrality. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 148, 111360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, L.; Pan, S.; Wang, S. Low-carbon emitting university campus achieved via anaerobic digestion of canteen food wastes. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 335, 117533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, K.R.; Leong, H.Y.; Khoo, K.S.; Vo, D.-V.N.; Anjum, H.; Chang, C.-K.; Show, P.L. Effects of anaerobic digestion of food waste on biogas production and environmental impacts: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 2921–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawer, M.U.B.; Naqvi, S.R.; Ali, I.; Arshad, M.; Juchelková, D.; Anjum, M.W.; Naqvi, M. Anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge for biogas & biohydrogen production: State-of-the-art trends and prospects. Fuel 2022, 329, 125416. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Qiao, W.; Westerholm, M.; Huang, G.; Taherzadeh, M.J.; Dong, R. Microbiological and technological insights on anaerobic digestion of animal manure: A review. Fermentation 2023, 9, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foundation, L.S.R. World Risk Poll 2024 Report: A World of Waste—Risks and Opportunities in Household Waste Management; Lloyd’s Register Foundation: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Programme, U.N.E. Food Waste Index Report 2024: Tracking Progress to Halve Global Food Waste; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Shen, C. Microbial community acclimation during anaerobic digestion of high-oil food waste. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilarska, A.A.; Kulupa, T.; Kubiak, A.; Wolna-Maruwka, A.; Pilarski, K.; Niewiadomska, A. Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste—A Short Review. Energies 2023, 16, 5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, F. Anaerobic co-digestion of food waste and excess sludge by humus composites: Characteristics and microbial community structure. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, M.N.I.; Wahid, Z.A. Achievements and perspectives of anaerobic co-digestion: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 194, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisowmeya, G.; Chakravarthy, M.; Devi, G.N. Critical considerations in two-stage anaerobic digestion of food waste—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-G.; Heo, T.-Y.; Kwon, H.-J.; Shi, W.-Q.; Jun, H.-B. Effects of voltage supply on the methane production rates and pathways in an anaerobic digestion reactor using different electron donors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 9459–9468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabib, A.; Abdallah, M.; Shanableh, A.; Sartaj, M. Effect of substrates and voltages on the performance of bio-electrochemical anaerobic digestion. Renew. Energy 2022, 198, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, B.; Sun, C.; Chen, L.; Wang, K.; Li, Q.; Chen, R. The separate and synergistic role of biochar and electric field to facilitate mesophilic anaerobic digestion of food waste slurry. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 61, 105262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Xiao, C.; Workie, E.; Zhang, J.; He, Y.; Tong, Y.W. Bioelectrochemical enhancement of methanogenic metabolism in anaerobic digestion of food waste under salt stress conditions. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 13526–13535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yin, W.; Pu, R.; Bao, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, F.; Ding, C.; Bai, X. Alternating current-driven bioelectrochemical regulation prevents acidogenic accumulation in carbohydrate-rich anaerobic digestion. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 517, 164459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.-K.; Yu, H.-C.; Kim, K.-T.; Ahn, Y.; Feng, Q.; Song, Y.-C. Continuous augmentation of anaerobic digestion with electroactive microorganisms: Performance and stability. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 413, 131523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Hua, J.; Cheng, J.; Yue, L.; Zhou, J. Microbial electrochemistry enhanced electron transfer in lactic acid anaerobic digestion for methane production. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 358, 131983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madondo, N.I.; Kweinor Tetteh, E.; Rathilal, S.; Bakare, B.F. Effect of an Electromagnetic Field on Anaerobic Digestion: Comparing an Electromagnetic System (ES), a Microbial Electrolysis System (MEC), and a Control with No External Force. Molecules 2022, 27, 3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.J.; Wang, W.Q.; Chen, C.; Xie, P.; Liu, W.Z.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X.T.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, A.J.; Lee, D.J.; et al. Bioelectrochemical system for the enhancement of methane production by anaerobic digestion of alkaline pretreated sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 304, 123000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, I.; Ghangrekar, M.M. Pilot-Scale Case Performance of Bioelectrochemical Systems. Microb. Electrochem. Technol. Fundam. Appl. 2023, 2, 555–582. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Zou, X.; Chang, Y.; Liu, H.; Cui, M.-H.; Zhang, T.C.; Xi, J.; Chen, C. A feasibility investigation of a pilot-scale bioelectrochemical coupled anaerobic digestion system with centric electrode module for real membrane manufacturing wastewater treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 368, 128371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Fessler, M.; Jin, B.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Y. Insights into the impact of polyethylene microplastics on methane recovery from wastewater via bioelectrochemical anaerobic digestion. Water Res. 2022, 221, 118844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-G.; Kwon, H.-J.; Sposob, M.; Jun, H.-B. Effect of a side-stream voltage supplied by sludge recirculation to an anaerobic digestion reactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 300, 122643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-G.; Lee, B.; Kwon, H.-J.; Park, H.-R.; Jun, H.-B. Effects of a novel auxiliary bio-electrochemical reactor on methane production from highly concentrated food waste in an anaerobic digestion reactor. Chemosphere 2019, 220, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Public Health Association; American Water Works Association; Water Environment Federation. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Sun, D.; Dang, Y.; Lei, Y.; Ji, J.; Lv, T.; Bian, R.; Xiao, Z.; Yan, L.; Holmes, D.E. Enhancing biomethanogenic treatment of fresh incineration leachate using single chambered microbial electrolysis cells. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 231, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, X.-T.; Chen, K.-Y.; Wang, Z.-H.; Xu, X.-J.; Zhou, X.; Xing, D.-F.; Ren, N.-Q.; Lee, D.-J.; Chen, C. The underlying mechanism of enhanced methane production using microbial electrolysis cell assisted anaerobic digestion (MEC-AD) of proteins. Water Res. 2021, 201, 117325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurus, K.; Kremmeter, N.; Ahmed, S.; Kazda, M. High-resolution monitoring of VFA dynamics reveals process failure and exponential decrease of biogas production. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2023, 13, 10653–10663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, B.; Patil, S.M.; Saha, S.; Kurade, M.B.; Ha, G.-S.; Govindwar, S.P.; Lee, S.S.; Chang, S.W.; Chung, W.J.; Jeon, B.-H. Rapid recovery of methane yield in organic overloaded-failed anaerobic digesters through bioaugmentation with acclimatized microbial consortium. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 764, 144219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Heaven, S.; Banks, C. Strategies for stable anaerobic digestion of vegetable waste. Renew. Energy 2012, 44, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Song, Y.-C.; Kim, D.-H.; Kim, M.-S.; Kim, D.-H. Influence of the temperature and hydraulic retention time in bioelectrochemical anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 2170–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.-S.; Kondaveeti, S.; Min, B. Bioelectrochemical methane (CH4) production in anaerobic digestion at different supplemental voltages. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 245, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Reddy, C.N.; Min, B. In situ integration of microbial electrochemical systems into anaerobic digestion to improve methane fermentation at different substrate concentrations. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2019, 44, 2380–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, H.T.; Min, B. Enhanced methane fermentation of municipal sewage sludge by microbial electrochemical systems integrated with anaerobic digestion. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2019, 44, 30357–30366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yan, F.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Nie, H.; Jiang, H.; Qian, M.; Zhou, H. Influence of organic loading rate on the performance of a two-phase pressurized biofilm (TPPB) system treating food waste. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2017, 26, 2047–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambaye, T.G.; Rene, E.R.; Dupont, C.; Wongrod, S.; Van Hullebusch, E.D. Anaerobic digestion of fruit waste mixed with sewage sludge digestate biochar: Influence on biomethane production. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Feng, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Zi, H. Influence of Organic Loading Rate on Methane Production from Brewery Wastewater in Bioelectrochemical Anaerobic Digestion. Fermentation 2023, 9, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, G.; Kim, K.-Y.; Logan, B.E. Impact of surface area and current generation of microbial electrolysis cell electrodes inserted into anaerobic digesters. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426, 131281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-G.; Jiang, D.; Lee, B.; Jun, H.-B. Towards the practical application of bioelectrochemical anaerobic digestion (BEAD): Insights into electrode materials, reactor configurations, and process designs. Water Res. 2020, 184, 116214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-G.; Lee, B.; Shi, P.; Kim, Y.; Jun, H.-B. Effects of electrode distance and mixing velocity on current density and methane production in an anaerobic digester equipped with a microbial methanogenesis cell. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 27732–27740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.