A Novel Approach to Improving Heat Transfer and Minimizing Fouling in Tube Bundles: Insert Elements Inspired by Venetian Blinds

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Previous Studies on Improving Heat Transfer in Tube Bundles, Especially Boiler Tube Banks

1.2. A New Solution for Intensifying Heat Transfer Outside the Tubes—Insert Elements Shaped Similarly to Window Blinds System

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Numerical Methods

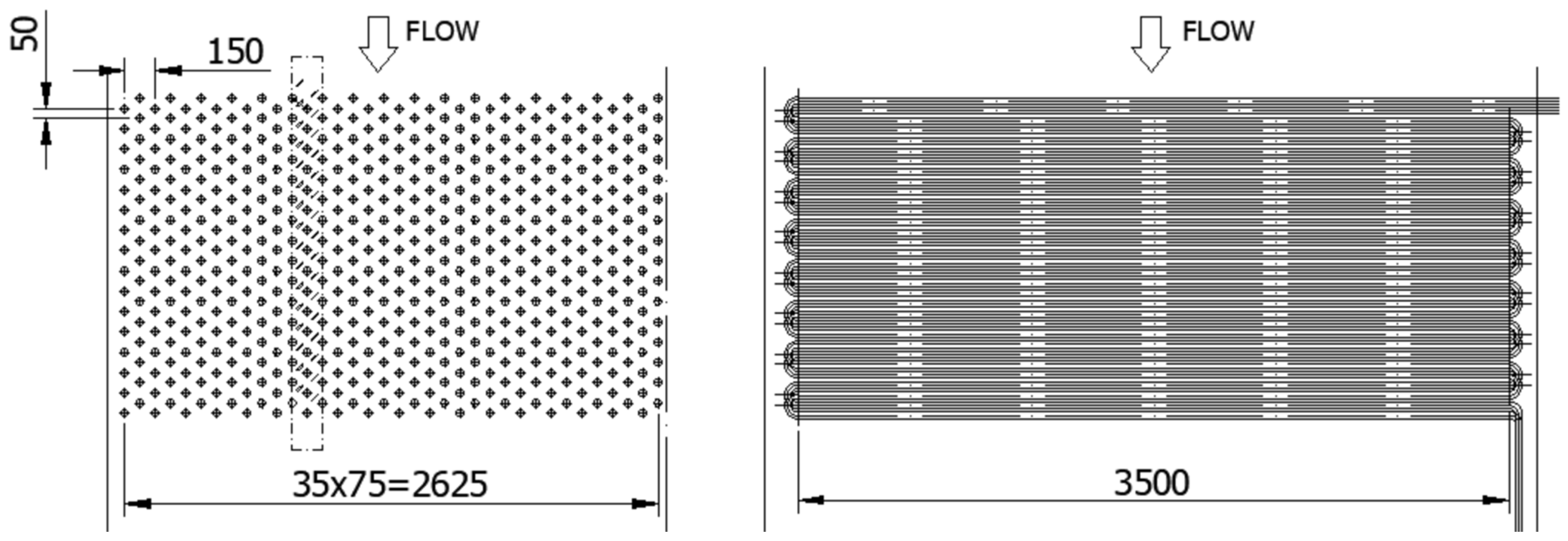

2.2. Geometry Selection

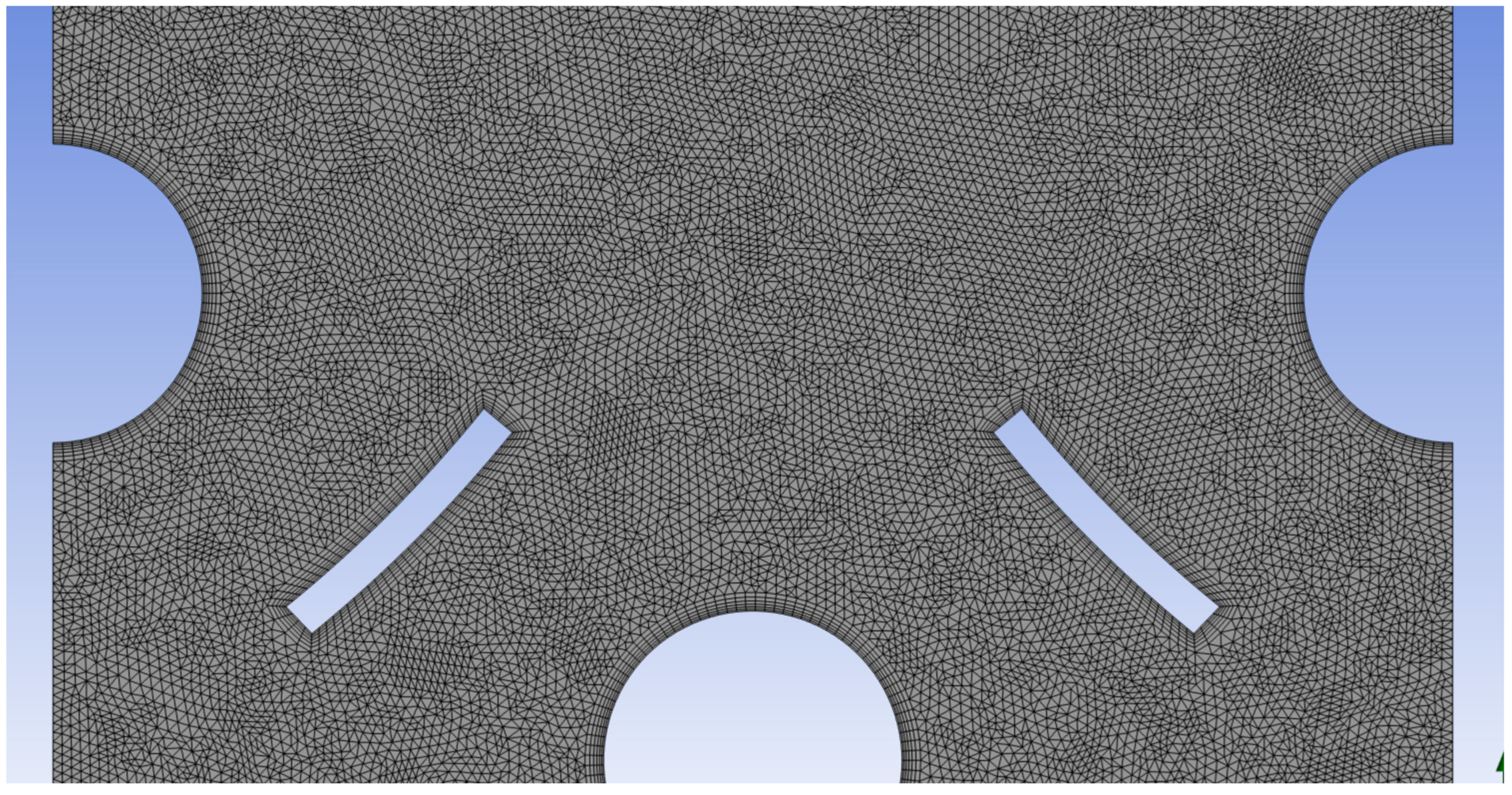

2.3. Numerical Model 2D and Boundary Conditions

- Rosin–Rammler distribution;

- Average particle diameter dave = 63 µm;

- Maximum particle diameter dmax = 253 µm;

- Minimum particle diameter dmin = 1 µm;

- Spreading parameter n = 1.398;

- 6 classes of particles;

- 1.2 kg/s for full load.

3. Results and Discussion

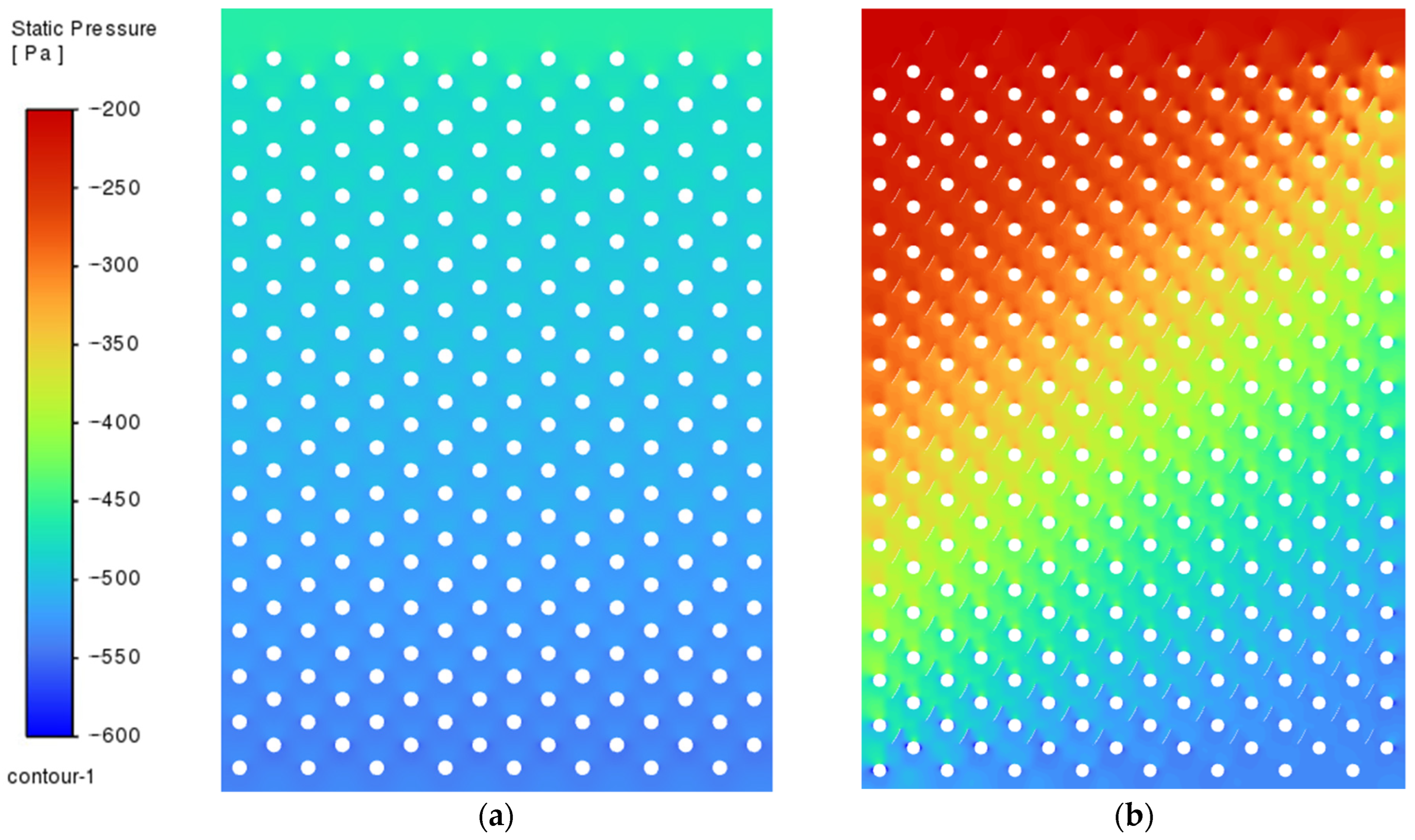

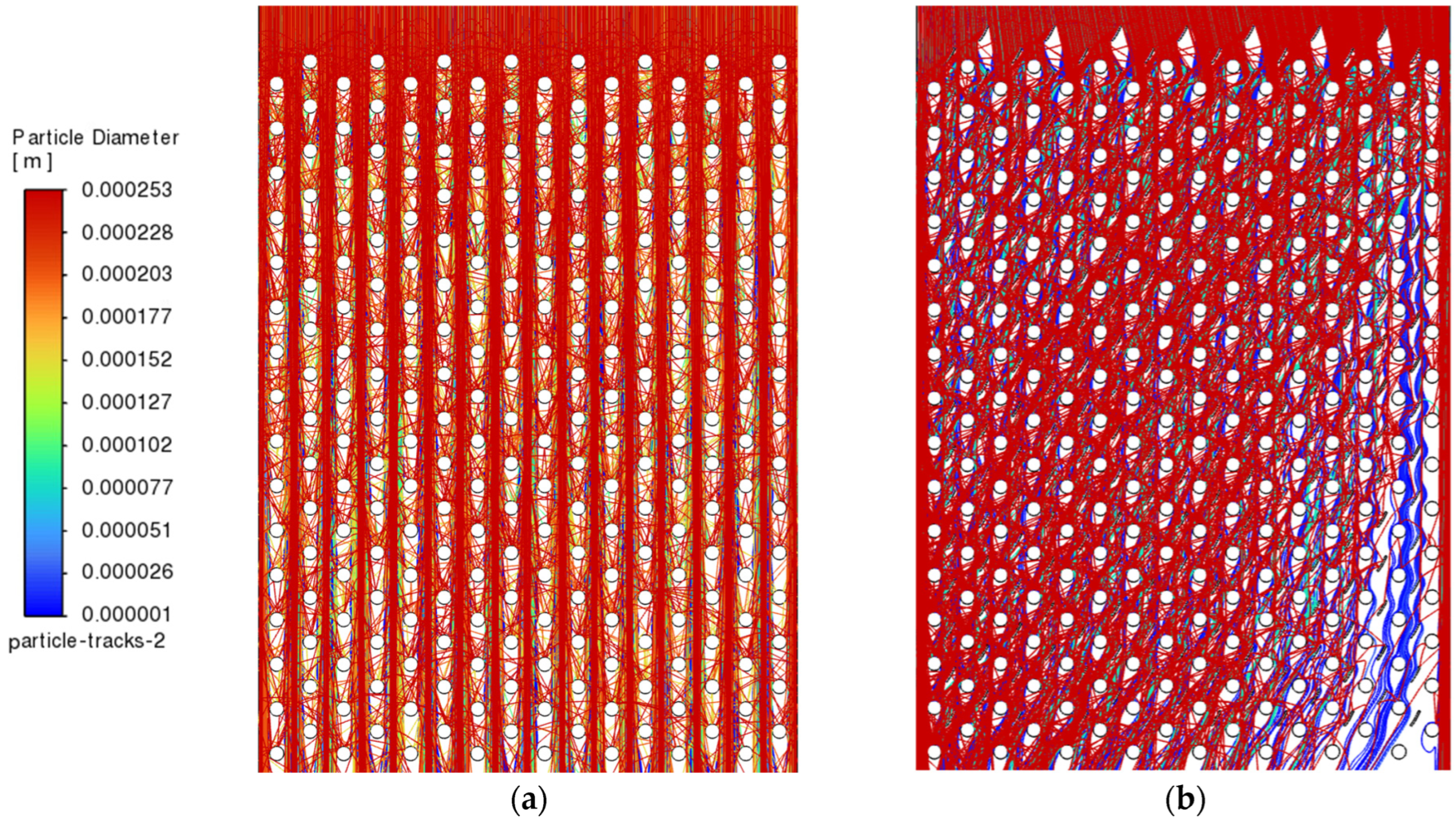

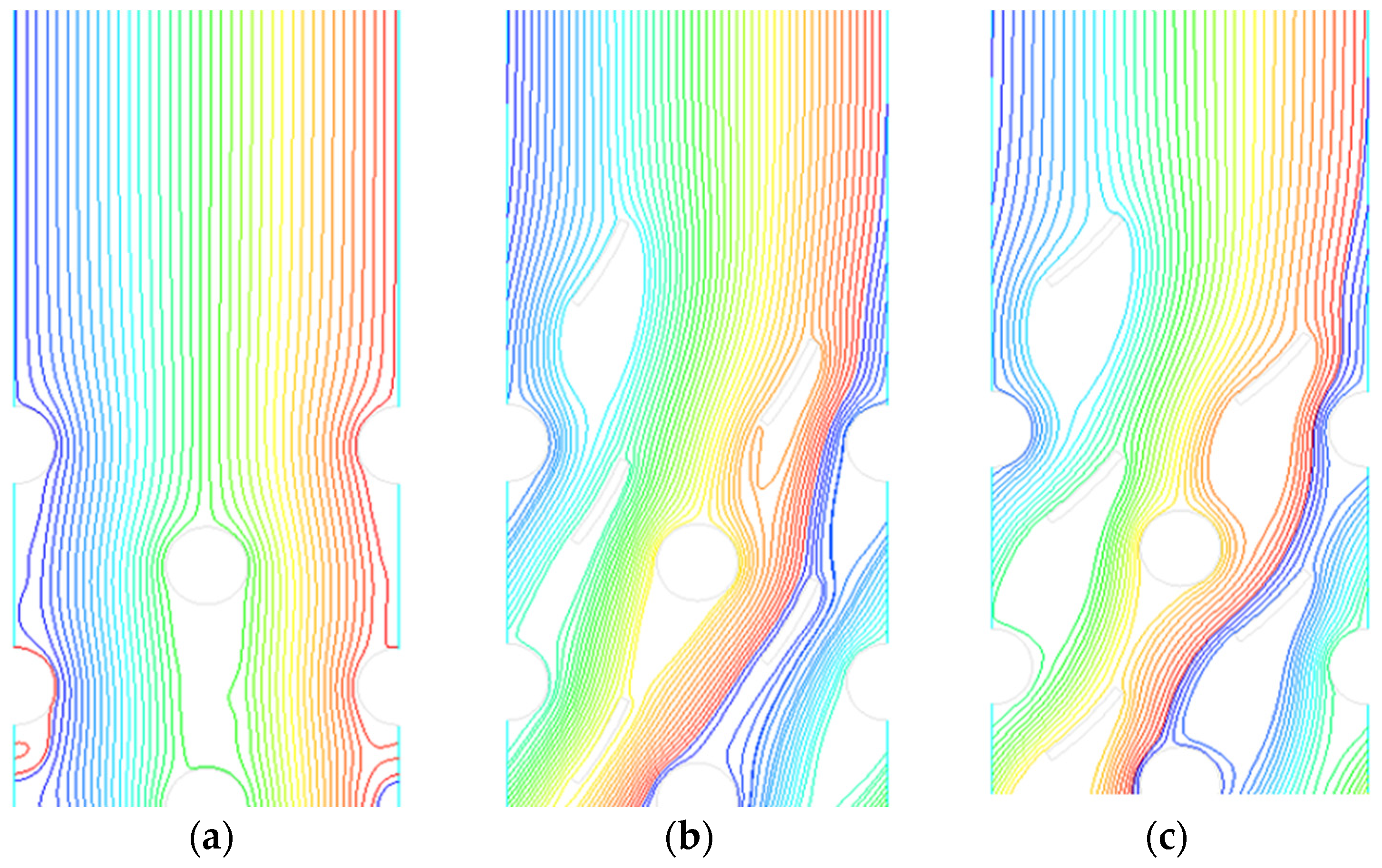

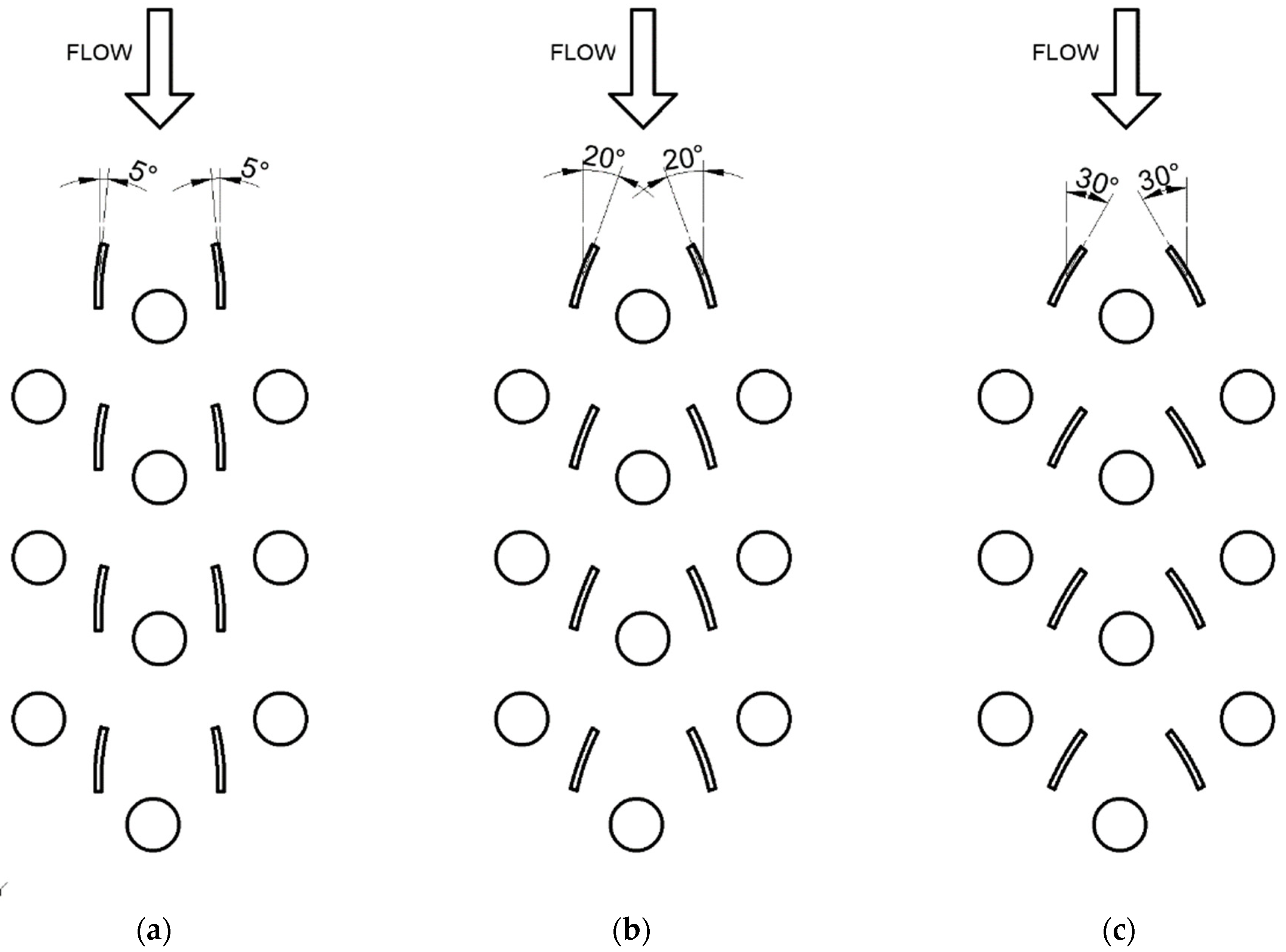

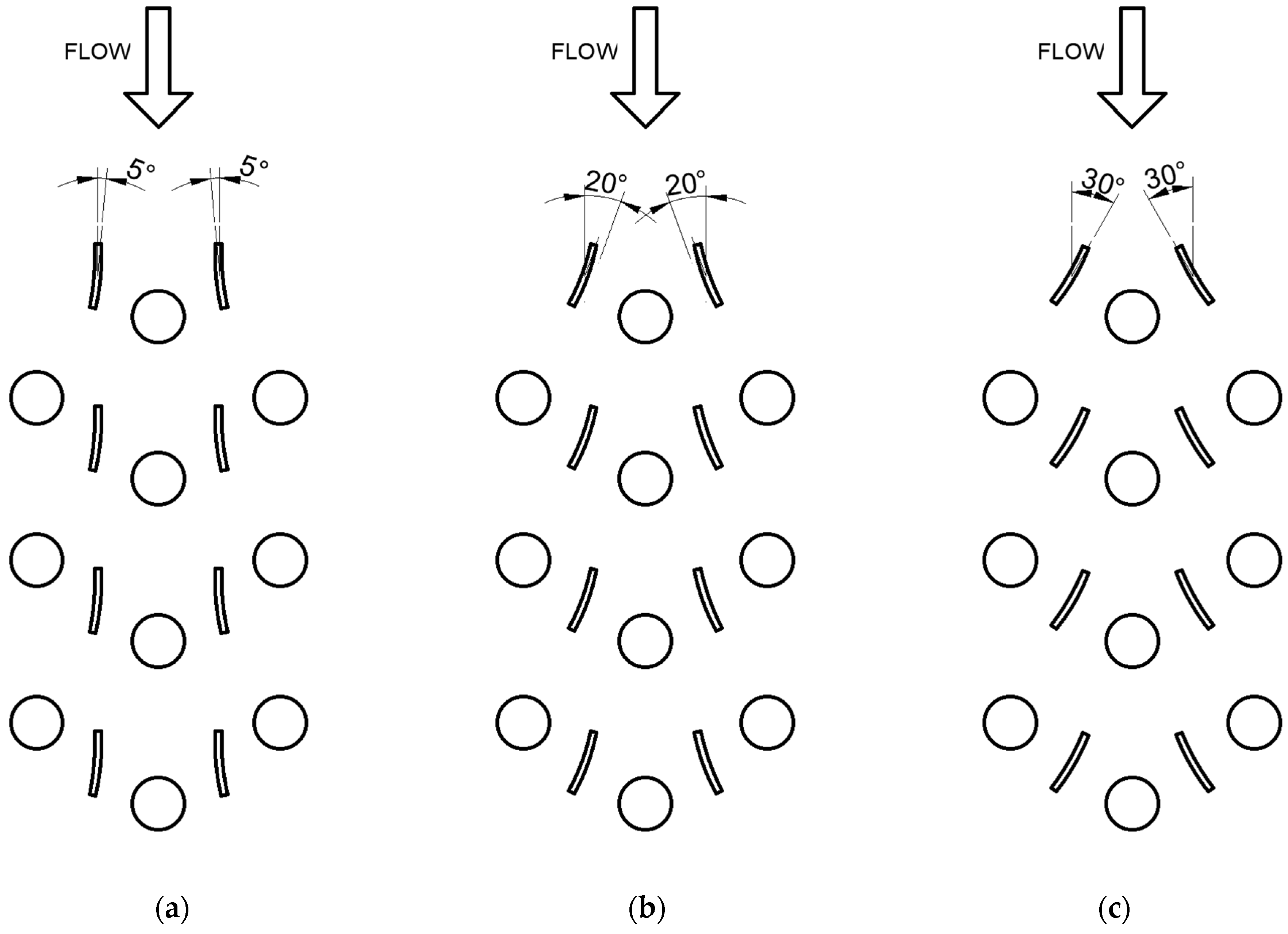

3.1. Flow, Heat Transfer, and Particle Trajectories Tests for Insertion of Inserts in a System of Nonsymmetric ( ( Arrangement

3.2. Flow and Heat Transfer Tests for Inserts in a Symmetric System ( )

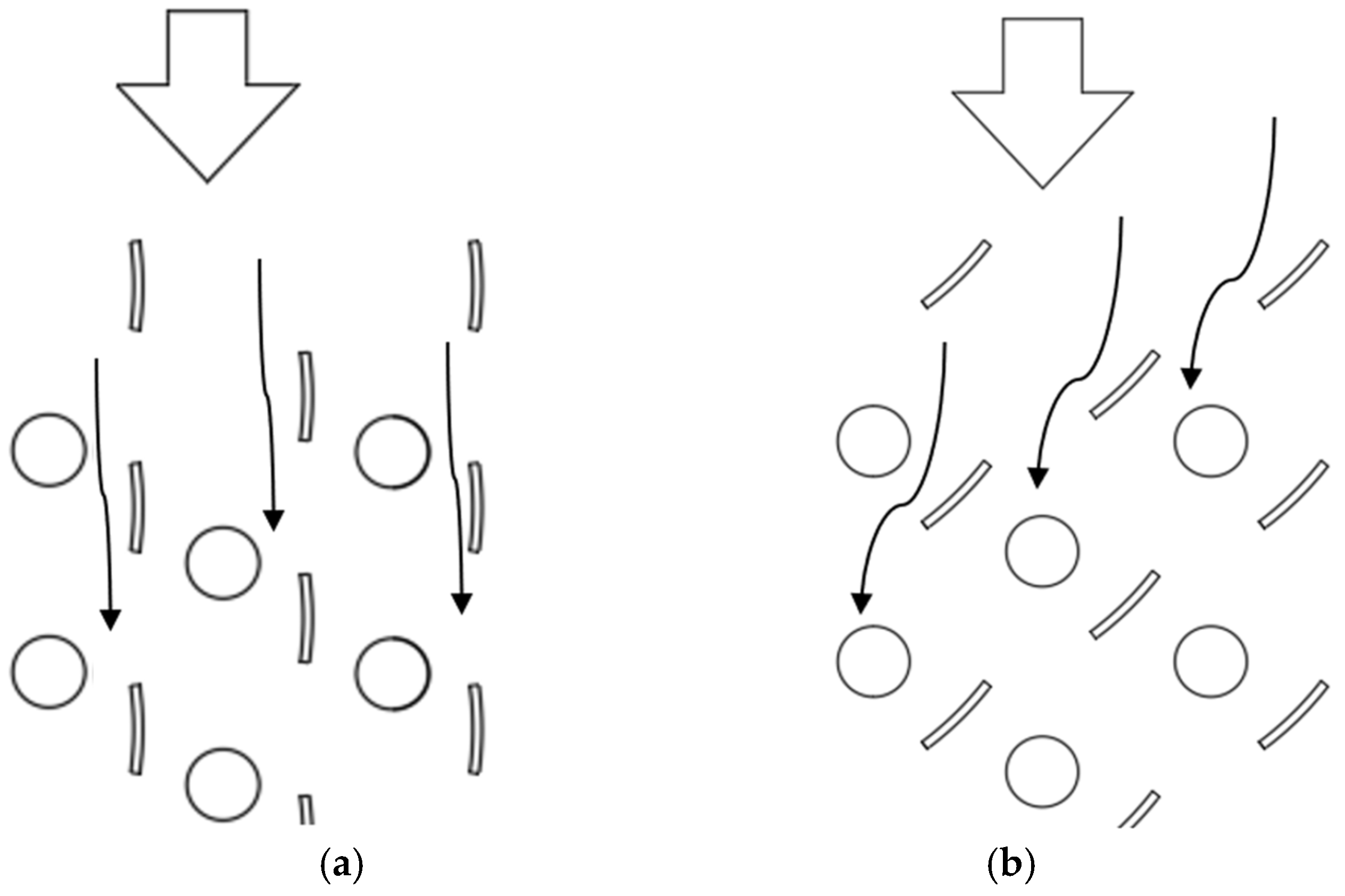

3.3. Ash Particle Trajectory for Inserts in Window Blinds System

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stevanovic, V.D.; Wala, T.; Muszynski, S.; Milic, M.; Jovanovic, M. Efficiency and Power Upgrade by an Additional High Pressure Economizer Installation at an Aged 620 MWe Lignite-Fired Power Plant. Energy 2014, 66, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, M.; Pronobis, M. Konvektiver Wärmeübergang Bei Querangeströmten Membranrohren. VGB Kraftwerkstechnik 1982, 62, 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Лисейскин, И.Д.; Андреевa, А.Я.; Патина, Т.М. Исследoвание Теплooтдачи и Азрoдинамическoгo Сoпрoтивления в Мембранных Кoнвективных Пучках Труб с Прoфильными Прoставками. Тepлoэнepeтика 1974, 9, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Pronobis, M. Přenos Tepla ve Svazcích Žebrowaných Trubek. Energetika 1987, 37, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Pronobis, M.; Kalisz, S.; Wejkowski, R. Model Investigations of Convective Heat Transfer and Pressure Loss in Diagonal Membrane Heating Surfaces. Heat Mass Transf. 2002, 38, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czepelak, J.; Gaiński, J.; Pronobis, M. Modelluntersuchungen Des Wärmeaustausches Und Strömungswiderstandes an Den Heizflächen Mit Diagonalflossen. Heat Mass Transf. 1996, 31, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, H. Untersuchpungen an Querstrom–Wärmeaustauschern Mit Verschiedenen Rohrformen. Mittelungen der VGB 1961, 73, 260–276. [Google Scholar]

- Wejkowski, R. Heat Transfer and Pressure Loss In Combined Tube Banks With Triple-Finned Tubes. Heat Transf. Eng. 2016, 37, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Жукаускас, A. Кoнвективный Перенoс в Теплooбменниках. Наука. Мoсква 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Czepelak, J.; Pronobis, M. Výména Tepla v Prične Žebrovaných Trubkových Svazcích. Strojirenstvi 1990, 40, 119–122. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Ma, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z. Experimental Investigation of Heat Transfer and Pressure Drop Characteristics of H-Type Finned Tube Banks. Energies 2014, 7, 7094–7104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, L.; Gao, G.; Zhu, X. Heat Transfer and Flow Resistance in Crossflow over Corrugated Tube Banks. Energies 2024, 17, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erguvan, M.; MacPhee, D.W. Energy and Exergy Analyses of Tube Banks in Waste Heat Recovery Applications. Energies 2018, 11, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Meng, Z.; Feng, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Gao, X. Improvement of Heat Transfer Correlation for Fluoroplastic Steel Heat Exchanger and Theoretical Analysis of Application Characteristics. Energies 2024, 17, 5054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wejkowski, R. Triple-Finned Tubes—Increasing Efficiency, Decreasing CO2 Pollution of a Steam Boiler. Energy 2016, 99, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Calautit, J.K. A Parametric Investigation of the Heat Transfer Enhancement of Tube Bank Heat Exchanger with Reversed Trapezoidal Profile Fins. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2023, 42, 101914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raje, M.; Dhiman, A.K. Three-Dimensional Analysis of the Thermal and Hydraulic Performance of Finned and Un-Finned Tubes in a Staggered Array. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2022, 36, 101532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, C.R.; Kumar, P.; Roy, S.; Kanungo, D. CFD Analysis of an Economizer for Heat Transfer Enhancement Using Serrated Finned Tube Equipped with Variable Fin Segments. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangrulkar, C.K.; Dhoble, A.S.; Chakrabarty, S.G.; Wankhede, U.S. Experimental and CFD Prediction of Heat Transfer and Friction Factor Characteristics in Cross Flow Tube Bank with Integral Splitter Plate. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2017, 104, 964–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinkowski, M.; Taler, D.; Węglarz, K.; Taler, J. Advancements in Analyzing Air-Side Heat Transfer Coefficient on the Individual Tube Rows in Finned Heat Exchangers: Comparative Study of Three CFD Methods. Energy 2024, 307, 132754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, L.; Wang, J. Multi-Objective Optimization of Elliptical Tube Fin Heat Exchangers Based on Neural Networks and Genetic Algorithm. Energy 2023, 269, 126729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Lan, P.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Peng, F.; Hong, J. Multi-U-Style Micro-Channel in Liquid Cooling Plate for Thermal Management of Power Batteries. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 256, 123984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świrski, J. Badania Erozji Popiołowej i Ocena Zużycia Rur Kotłowych Wskutek Jej Działania. Prace Instytutu Energetyki 1875, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Meuronen, V. The Erosion Rate of Convective Heat Exchanger Tubes in a Steam Boiler by Tube Diameter and Wall Thickness Measurements. J. Inst. Energy 2003, 76, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wojnar, W. Erosion of Heat Exchangers Due to Sootblowing. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2013, 33, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Yang, W.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zeng, G. Dynamic Simulation on Ash Deposition and Heat Transfer Behavior on a Staggered Tube Bundle under High-Temperature Conditions. Energy 2020, 190, 116390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wei, W.; Zhao, L.; Xie, N.; Yang, T.; Jiang, K. Multi-Objective Optimization of PEMFC Performance at Different Altitudes through Integrated RSM, NSGA-II, EWM, and TOPSIS Methodology. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 177, 151615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polish Patent Pat.242770 Silesian University of Technology Bundles of Heat Exchanger 2022. Available online: https://api-ewyszukiwarka.pue.uprp.gov.pl/api/collection/e286c96fa1c3c04766ff1f5fe2ac99f8 (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Fluent. User’s Guide, 2006. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/doc/49062969/FLUENT-6-3-26-User-s-Guide (accessed on 19 November 2025).

| Parameter | Unit | Full Boiler Load | Min Boiler Load |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tube bundle velocity | m/s | 4.7 | 3.2 |

| Gas inlet temperature | K | 710 | 732 |

| Average temperature of the inner wall of the tube | 483 | 483 | |

| Outlet pressure | Pa | −1000 | −698 |

| Ash particle flux | kg/s | 0.2 | 0.14 |

| Temperature of particles | K | 710 | 732 |

| Parameter | Unit | Base Plain Tubes | Tubes + Inserts ( ) 5° | Tubes + Inserts ( ) 20° | Tubes + Inserts ( ) 30° | Tubes + Inserts ) ( 5° | Tubes + Inserts ) ( 20° | Tubes + Inserts ) ( 30° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tin | K | 710 | 710 | 710 | 710 | 710 | 710 | 710 |

| tout | K | 663.9 | 655.3 | 646.2 | 640.2 | 656 | 643.6 | 636.3 |

| Δt | K | 46.1 | 54.7 | 63.8 | 69.8 | 54 | 66.4 | 73.7 |

| Δttmod–Δtbase | K | −8.6 | −17.7 | −23.7 | −7.9 | −20.3 | −27.6 | |

| Δtmod/Δtbase | 1.19 | 1.38 | 1.51 | 1.17 | 1.44 | 1.60 | ||

| pin | Pa | −924.1 | −815.2 | −612.8 | −450.3 | −820.2 | −590 | −335.1 |

| pout | Pa | −1000 | −1000 | −1000 | −1000 | −1000 | −1000 | −1000 |

| Δp | Pa | −75.9 | −184.8 | −387.2 | −549.7 | −179.8 | −410 | −664.9 |

| Δpmod–Δpbase | Pa | 108.9 | 311.3 | 473.8 | 103.9 | 334.1 | 589 | |

| Δpmod/Δpbase | 2.43 | 5.10 | 7.24 | 2.37 | 5.40 | 8.76 | ||

| Vmax | m/s | 9.8 | 11.1 | 12.0 | 13.9 | 11.24 | 12.7 | 14.6 |

| Δpmod/Δpbase/Δtmod/Δtbase | 2.05 | 3.69 | 4.78 | 2.02 | 3.75 | 5.48 |

| Parameter | Unit | Base Plain Tubes | Tubes + Inserts ( ) 5° | Tubes + Inserts ( ) 20° | Tubes + Inserts ( ) 30° | Tubes + Inserts ) ( 5° | Tubes + Inserts ) ( 20° | Tubes + Inserts ) ( 30° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tin | K | 732 | 732 | 732 | 732 | 732 | 732 | 732 |

| tout | K | 670.7 | 667 | 657 | 650.2 | 668.3 | 655.5 | 645.7 |

| Δt | K | 61.3 | 65 | 75 | 81.8 | 63.7 | 76.5 | 86.3 |

| Δttmod–Δtbase | K | 3.7 | −13.7 | −20.5 | −2.4 | −15.2 | −25 | |

| Δtmod/Δtbase | 1.06 | 1.22 | 1.33 | 1.04 | 1.25 | 1.41 | ||

| pin | Pa | −659.5 | −612.1 | −513.9 | −436 | −615 | −502.8 | −377.9 |

| pout | Pa | −700 | −700 | −700 | −700 | −700 | −700 | −700 |

| Δp | Pa | −40.5 | −87.9 | −186.1 | −264 | −85 | −197.2 | −322.1 |

| Δpmod–Δpbase | Pa | 47.4 | 145.6 | 223.5 | 44.5 | 156.7 | 281.6 | |

| Δpmod/Δpbase | 2.17 | 4.60 | 6.52 | 2.10 | 4.87 | 7.95 | ||

| Vmax | m/s | 6.7 | 7.5 | 9.0 | 9.52 | 7.7 | 8.7 | 10 |

| Δpmod/Δpbase/Δtmod/Δtbase | 2.05 | 3.76 | 4.88 | 2.02 | 3.90 | 5.65 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wejkowski, R. A Novel Approach to Improving Heat Transfer and Minimizing Fouling in Tube Bundles: Insert Elements Inspired by Venetian Blinds. Energies 2026, 19, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010162

Wejkowski R. A Novel Approach to Improving Heat Transfer and Minimizing Fouling in Tube Bundles: Insert Elements Inspired by Venetian Blinds. Energies. 2026; 19(1):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010162

Chicago/Turabian StyleWejkowski, Robert. 2026. "A Novel Approach to Improving Heat Transfer and Minimizing Fouling in Tube Bundles: Insert Elements Inspired by Venetian Blinds" Energies 19, no. 1: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010162

APA StyleWejkowski, R. (2026). A Novel Approach to Improving Heat Transfer and Minimizing Fouling in Tube Bundles: Insert Elements Inspired by Venetian Blinds. Energies, 19(1), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010162