Abstract

Novel A-D-A (acceptor–donor–acceptor)-type molecules were synthesized and tested in organic photovoltaics (OPV) devices. For a pristine film of compound 1b with a 2,2′-(naphtho[2,3-b]thiophene-4,9-diylidene)dipropanedinitrile A unit and carbazole-based donor D unit, efficient exciton splitting by intermolecular electron transfer was proved. The observation of the out-of-phase electron spin echo in the pristine 1b film unambiguously testifies to a high yield of charge-transfer state formation. Despite this, the yield of free charge generation in pristine 1b is low due to the fast geminate and non-geminate recombination. This process is detrimental for OPV performance when the compound capable of exciton self-splitting is used as an acceptor component of the bulk heterojunction (BHJ) active layer because of the fast charge recombination within this component. Exciton self-splitting can be of general significance for push–pull OPV acceptors or donors in bulk heterojunctions, although it can be masked by other photophysical processes in the BHJ active layer. This is the reason why molecules with a strong intermolecular charge-transfer band are not suitable components of the active layer of efficient OPV devices.

1. Introduction

Organic photovoltaics is a rapidly developing field of renewable energetics [1]. The feature of the OPV device is its active layer. Due to efficient light absorption in organic materials, active layers can be as thin as ~100 nm, enabling lightweight and flexible OPV devices. In addition, active layer materials of OPV devices are solution processable, which is a prerequisite for low-cost, large-scale manufacturing. Typically, the OPV active layer material is a blend of donor and acceptor organic compounds, which form the so-called bulk heterojunction (BHJ) [2,3]. Proper alignment of the energy levels of the frontier electronic orbitals (HOMO and LUMO) of the donor and the acceptor components is essential for efficient BHJ. In combination with the optimal size of donor and acceptor domains, it ensures a high yield of charge separation and exciton splitting with charge-transfer state (CTS) formation at the donor–acceptor interface [4,5]. Usually, semiconducting polymers are used as the donor materials in the BHJ active layer. For several decades, fullerene derivatives were the dominant acceptor materials, providing the highest power conversion efficiency (PCE) [6]. Recent advances in non-fullerene acceptors (NFAs) have yielded materials superior to fullerenes, demonstrating power conversion efficiencies (PCEs) as high as 20% [7,8]. However, the synthesis of highly efficient NFAs is challenging due to their complex structure, which is characterized by a large, polyconjugated, multi-heterocyclic core [9,10]. The resulting high expense poses a significant barrier to the commercial-scale production of these compounds. This drives the search for efficient NFAs possessing a simpler chemical structure, such as non-fused ring NFAs [9,11].

The design of NFAs from simple electron acceptor (A) and electron donor (D) units enables the possibility of fine tuning their electronic structure while maintaining their synthetic simplicity. A partial intramolecular electron density shift from D to A units (push–pull effect) in such systems can be used to promote charge delocalization and broaden the optical absorption range [12]. To achieve a good photovoltaic performance of the NFA, the electron-accepting and electron-donating properties of its units should be adjusted. Previously, we tested the photovoltaic properties of A-D-A-type molecules with 2,2′-(anthra[2,3-b]thiophene-5,10-diylidene)dipropanedinitrile (ATDPDN) A units (Figure 1) in BHJ blends with polymer donors [13]. For those blends, the strong localization of photogenerated electrons at the ATDPDN unit of the acceptor molecule was identified as the main origin of poor photovoltaic performance. In this paper, similar molecules with a different A unit, namely, 2,2′-(naphtho[2,3-b]thiophene-4,9-diylidene)dipropanedinitrile (NTDPDN) (Figure 1), were synthesized and tested as the acceptor component of the BHJ blend. The OPV performance of the NTDPDN-based NFA was rather poor. The detailed characterization of the newly synthesized compounds in combination with quantum–chemical calculations allowed us to identify an additional photophysical process involving the NFA, which limits OPV performance. We revealed splitting of the exciton within the acceptor phase with the generation of an electron and hole at different acceptor molecules. For simplicity, we call it exciton self-splitting. Although exciton self-splitting results in the photogeneration of electrons and holes, they are located in the same acceptor domain, in contrast to a BHJ, where electrons and holes are separated spatially into the acceptor and the donor domains, respectively. For this reason, electrons and holes produced by exciton self-splitting have high chances to recombine either geminately or non-geminately.

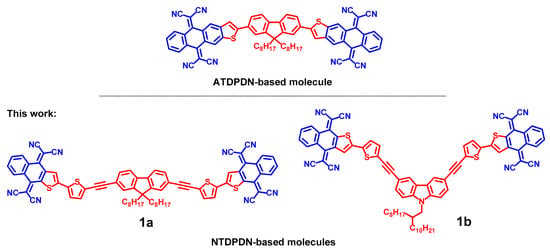

Figure 1.

The structure of the A-D-A-type molecules. The donor fragments are shown in red; the acceptor fragments are shown in blue. The ATDPDN-based molecule was studied in Ref. [13].

To trace exciton self-splitting, we used out-of-phase electron spin echo (ESE) for a pristine NTDPDN-based compound. Out-of-phase ESE is a specific pulse EPR technique which is able to detect the signal of correlated pairs of electron spins. Usually, such a pair consists of the spins of the positive and the negative charges produced from the same electronically excited state (a geminate charge pair). The intensity of the out-of-phase ESE signal is modulated with the frequency of magnetic interaction between the spins forming the geminate pair when the delay between the echo-forming microwave pulses is varied [14]. Therefore, analysis of this dependence allows measurement of the distance between the coupled spins [15,16]. It was also used for reconstruction of the electron–hole distance distribution for the charge-transfer state for various photovoltaic BHJ blends [17]. For the pristine NTDPDN-based compound studied in the present work, this distribution appeared to be surprisingly similar to that of efficient polymer/fullerene BHJ blends. However, the efficiency of the OPV devices with the pristine NTDPDN-based compound as the active layer was very low. This shows that efficient exciton self-splitting does not ensure good OPV performance. Moreover, exciton self-splitting in the NFA could deteriorate the performance of the donor/acceptor BHJ blend if strong charge recombination within the acceptor phase occurs.

2. Materials and Methods

Compounds 1a and 1b (Figure 1) were synthesized in several steps. Assembly of the 2,2′-(naphtho[2,3-b]thiophene-4,9-diylidene)dipropanedinitrile (NTDPDN) molecules 1 was accomplished via the Sonogashira coupling of pre-prepared 2-(5-iodothien-2-yl)naphtho[2,3-b]thiophene-4,9-dione with 2,7-diethynyl-9,9-dioctyl-9H-fluorene or 3,6-diethynyl-9-(2-octyldodecyl)-9H-carbazole followed by a Knoevenagel condensation of quinone precursors with malononitrile (for details of synthesis and characterization, see the Supplementary Materials).

The surface roughness and the thickness of 1b film were measured using a SMART atomic force microscope (AIST-NT, Zelenograd, Russia). For the latter measurement, a scratch was made on the 1b film by a sharp needle, and the depth of the scratch was assigned to the film thickness. The 1b film was deposited on a flat glass by spin-coating.

EPR measurements were performed using an approach very similar to that described in [18]. They are described in the Supplementary Materials.

The photoluminescence (PL) spectrum and decay of the 1b film deposited on the glass substrate from chloroform solution were conducted using an FLSP-920 spectrofluorimeter (Edinburgh Instruments, Edinburgh, UK). PL measurements of the 1b solution were measured at a concentration of 0.01 mg/mL.

All measurements, except EPR and ESE, were performed in ambient air at room temperature. The equipment and experimental conditions are described in detail in the Supplementary Materials.

3. Results

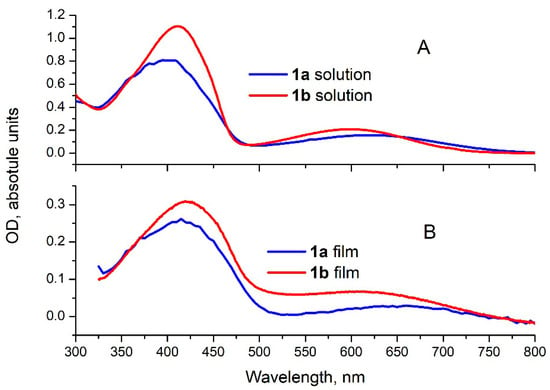

Compounds 1a and 1b consist of two strongly electron-accepting NTDPDN units connected by the fluorene- or the carbazole-based donor linker (1a and 1b, respectively). They are structurally similar to previously reported ATDPDN-based compounds used as electron acceptors [13]. The optical absorption spectra of compounds 1a and 1b in solution (Figure 2) have a broad line in the visible range with the maximum at 410 and 405 nm and peak extinction coefficients of 1.1 × 104 M−1cm−1 and 0.8 × 104 M−1cm−1 for 1a and 1b, respectively. These spectra also exhibit a weak low-energy shoulder, extending to ca. 750 nm for 1a and 770 nm for 1b. We assign this shoulder to the intramolecular charge-transfer band. The absorption spectra of the thin films and the solutions look very similar, showing a slight broadening and red shift of the main peak. Although compounds 1a and 1b exhibit a relatively low extinction coefficient, it remains suitable as an active layer material in OPV devices.

Figure 2.

Optical absorption spectra of chloroform solution (panel (A)) and thin films (panel (B)) of 1a and 1b (red and blue lines, respectively).

The LUMO energy levels for compounds 1a and 1b (Table 1) were straightforwardly determined from the pronounced reversible reduction peak in cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves (Figure S17):

where ERedonset is the voltage corresponding to the onset of the reduction peak, and e is the elementary charge. No oxidation peak was observed for 1a. The corresponding peak for 1b is arguable and likely originated from an impurity. We assume that the oxidation processes for the studied compounds are masked by the solvent. Therefore, HOMO energy was estimated as a difference between LUMO energy and the optical “bandgap” Eg calculated from the onset of the absorption spectrum of the compounds in solution. DFT calculations confirm these results, providing the energy of the frontier orbitals and the “bandgap” within 0.2 eV of the experimental values. The calculated HOMO of compounds 1 is mainly localized on the central donor fragment neighboring thiophene rings (Figures S18 and S19), while the calculated LUMO of 1b is localized in one of the NTDPDN fragments. Loss of the two-fold symmetry of this orbital is caused by a minor change in the conformation of 1b during geometry optimization. Symmetrical distribution of the electron density was predicted by DFT calculation for compound 1a (Figure S19). However, for 1a in a solid matrix, we expect distortion of the conformation of 1a due to interaction with its surroundings, which would cause a loss of symmetry and localization of the LUMO electron density at one NTDPDN fragment. The solution optical absorption spectra of 1 are reasonably reproduced by DFT calculations (Figure S21). In the calculated spectra, the majority of the transitions are within the range 350–500 nm, which correspond to the main absorption band of the experimental spectra. Additionally, there are a few transitions at longer wavelengths, corresponding to the shoulder of the experimental spectra. These transitions should be assigned to intramolecular charge-transfer bands. This is evident from the initial and the final molecular orbitals of the transition with the longest wavelength (872.5 nm) of 1b, which is obtained by DFT calculations (Figure S20). The initial orbital is very similar to the HOMO of 1b, while the final orbital is very similar to its LUMO, with the electron density localized at one NTDPDN fragment. This similarity justifies our approach to estimation of the HOMO energy of compounds 1a and 1b as the difference of the experimental values of the LUMO energy and the bandgap, which is based on the assumption ELUMO − EHOMO = Eg.

ELUMO [eV] = −e(ERedonset + 4.8),

Table 1.

Energy of frontier electronic orbitals and excited state energy of compounds 1a and 1b.

The main difference of the electronic structure of compounds 1a and 1b from that of the similar anthrathiophene-based OPV acceptor (compound 3b in the work of Baranov et al. [13]) is the stronger degree of LUMO localization in the former ones. This is caused by the smaller size of the polycondensed part of the acceptor unit in compounds 1a and 1b (naphtathiophene vs. anthrathiophene for the compounds reported in [13]). This explains the decrease in LUMO energy by 0.2–0.3 eV for compounds 1a and 1b compared to the anthrathiophene-based compounds of the similar structure [13].

The optimized geometric structure of 1a and 1b in the ground state is shown in Figure S22. The corresponding bond and dihedral angles are shown in Tables S1 and S2. DFT calculation revealed that the donor fragment is planar for both molecules. In the NTDPDN fragment, the angle between the thiophene ring and the naphthalene core is about 30 angular degrees. This is consistent with HOMO delocalization across the entire donor fragment of 1a and 1b and its extension to the thiophenes of the naphtathiophene moieties (Figure 1, Figures S18 and S19). Accordingly, LUMO is concentrated at the naphthalene part of the naphtathiophene moieties and the dicyanovinyl groups. Overall, these molecules have a nearly planar structure in the ground state, which ensures fast intramolecular electron transfer.

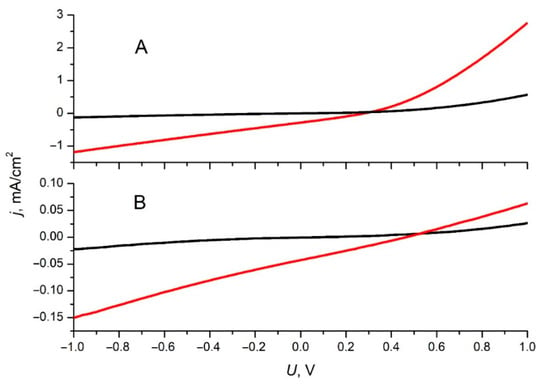

As shown in Table 1, the HOMO and LUMO energy of compounds 1a and 1b make it a suitable electron acceptor in BHJ OPV devices in combination with most donor polymers. Only compound 1b will be discussed further. The current density–voltage curve for an OPV device with the PBDB-T/1b active layer shows that all photovoltaic parameters of this device are poor (Figure 3, Table 2). This curve demonstrated a nearly linear dependence in the working region, which could be attributed to the electric shunting of the active layer caused by pinholes. However, the dark current density–voltage curve for this device does not show such dependence, which means that electric shunting is negligible. Linear current–voltage dependence below VOC could be explained by the electric field dependent rate of free charge photogeneration (dissociation of the charge-transfer state) [19] according to Onsager theory in the weak electric field limit [20,21]. However, since the performance of the PBDB-T/1b device is unexpectedly low compared to the reference OPV device with the PBDB-T/PC60BM active layer (see Figure S23 for IV-curves), we suggest that some additional process occurs in PBDB-T/1b BHJ, which acts detrimentally on its OPV performance. We propose that this process is exciton self-splitting within the 1b phase.

Figure 3.

Current density–voltage curves for OPV devices with a PBDB-T/1b active layer (A) and pristine 1b active layer (B). The curves are measured under white light illumination with an incident power density 100 mW/cm2 (red lines) and without illumination (black lines).

Table 2.

Photovoltaic parameters of the device with PBDB-T/1b and pristine 1b active layer.

To prove this, we tested analogous OPV devices with pristine 1b as the active layer material. In this case, the current density–voltage curve shows linear dependence, while the dark current is very small (Figure 3B).

Since the OPV device with the pristine 1b active layer is functional but has low efficiency (Table 2), 1b can be considered as a poor material for single-component organic solar cells (SCOSCs). Although the mechanism of photoelectric conversion in SCOSCs is not fully understood, it is certain that both electrons and holes are generated upon illumination of their active layer material [22]. As it is mentioned above, a linear IV-curve for the illuminated device points to the electric field dependence of the yield of free charges produced by dissociation of the CTS.

An AFM image of 1b film casted from chloroform shows a significant surface roughness of about 15 nm (Figure S24). However, the roughness is much smaller than the 1b film thickness determined from the depth of the scratch (~400 nm). Therefore, no pinholes can be formed in 1b film, which confirms once again that its low photovoltaic efficiency is not caused by 1b layer shortcuts.

The XRD pattern of a bulk polycrystalline 1b powder shows multiple wide diffraction peaks (Figure S25), indicating that the powder sample has poor crystallinity. The XRD pattern of the 1b film has only two diffraction peaks, which are located at 4.66° and 9.25° with FWHM = 0.383°. Using the Scherrer equation and taking into account the instrumental peak broadening of approximately 0.05°, we can calculate the size of the coherent scattering region as 23 nm for 1b. This value is in good agreement with the surface roughness of the 1b film, which allows suggesting that this is the average size of the 1b crystallines in the film. A comparison of the diffraction patterns reveals that the strong 5.84° peak present in the powdered 1b is absent in the thin film, indicating that 1b molecules adopt a preferred orientation in the thin films with respect to the substrate. In order to test this assumption, we recorded the 2D GIXD diffraction pattern of the 1b thin film. The 2D diffraction pattern of the 1b peaks (Figure S26) features a single smeared diffraction spot, indicating that a preferred orientation is indeed present in both thin films, albeit it is not very strong.

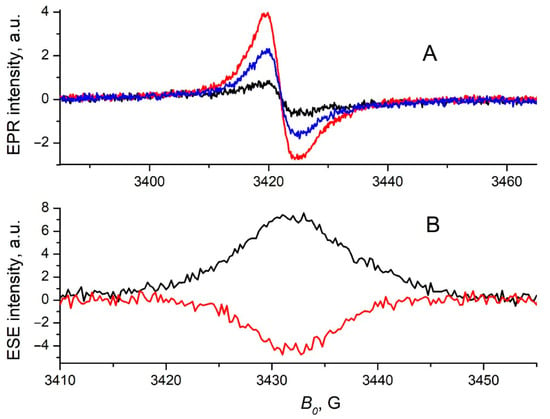

We used EPR spectroscopy to clarify the mechanism of the charge photogeneration in pristine 1b and to prove that the charge-transfer state is indeed formed upon illumination of this material. The continuous wave (CW) EPR signal of the 1b film, prepared in the dark, was weak, but it increased upon illumination (Figure 4A). When the light was switched off, this signal slowly decayed (on the timescale of minutes at 80 K), but it did not reach the initial (dark) value. The EPR signal is centered close to the free electron g-value and has the width of about 10 G. Very similar behavior was observed previously in light-induced EPR (LEPR) experiments with polymer/fullerene and polymer/NFA BHJ blends, for which the underlying mechanism is well understood [23,24,25]. In light of this concept, the increase in the EPR signal under illumination is caused by photogenerated charges. Free charges recombine non-geminately when the light is switched off. Some fraction of charges is trapped and contributes to the persistent LEPR signal. A similar EPR signal shape and its dependence on illumination for 1b and donor/acceptor BHJ blends suggest an identical charge photogeneration process. For 1b film, free electrons and holes are generated with some yield upon light absorption, which implies electron transfer from a photoexcited 1b molecule to a neighboring 1b molecule. This also indicates that the geminate electron and hole in 1b migrate from each other, producing free charges. DFT calculations suggest that a free electron is localized on the electron-accepting NTDPDN unit of 1b, while a hole is localized on the electron-donating carbazole-based unit.

Figure 4.

Panel (A): Continuous wave EPR traces for pristine 1b film measured in dark before illumination (black line), under illumination with λ = 630 nm (red line) and in dark after illumination (blue line). Panel (B): The in-phase echo-detected EPR spectrum of the thermalized photoinduced charges in pristine 1b film obtained without synchronization of the laser pulse with microwave echo-forming pulses (black line) and out-of-phase echo-detected EPR spectrum of the charge-transfer state in pristine 1b film obtained at DAF = 200 ns (red line). Temperature is 80 K, τ = 300 ns.

A strong in-phase ESE signal was obtained in the pristine 1b film without synchronization of the laser pulse with the microwave echo-forming pulses (Figure 4B). It is consistent with strong light-induced CW EPR in this compound. Both these signals originated from thermalized photogenerated charges [17]. Synchronization of the laser pulse with the microwave echo-forming pulses with small DAF (200 ns) resulted in the appearance of the out-of-phase ESE signal for 1b film (Figure 4B). A small DAF is needed to detect short-living paramagnetic species in the ESE experiment, which reveals the typical lifetime of the charge-transfer state in OPV BHJ blends in the microsecond range [26]. Since this signal can be produced only by spin-correlated charge pairs, this implies an efficient generation CTS in 1b. Previously, no out-of-phase ESE signal was observed in the single-component films of NFAs and polymer donors in analogous experiments [27] due to the low yield of photoinduced charge separation in those systems. For the 1b film, the out-of-phase ESE was centered at the same magnetic field as that of the in-phase ESE of thermalized photogenerated charges (Figure 4B). This points to the common origin of these signals. Evidently, they are produced by the same paramagnetic species—electrons and holes localized on 1b molecules.

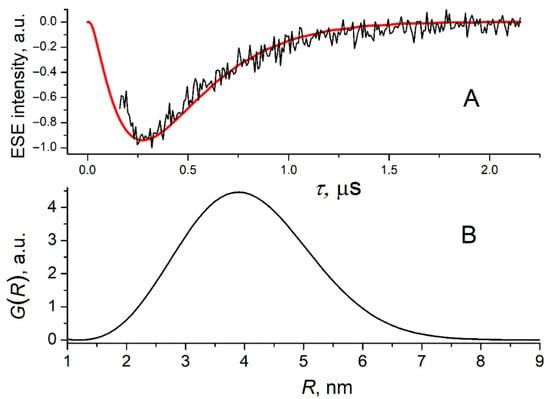

The shape and the intensity of the out-of-phase ESE trace for the pristine 1b film (Figure 5) are similar to those obtained previously for the OPV blends of donor polymers with fullerenes or NFAs [18]. The experimental out-of-phase ESE dependence on the interval between the echo-forming microwave pulses Mx(τ) (ESE envelope modulation or ESEEM) was numerically simulated:

where G(R) is the electron–hole distance distribution function, R is the distance between the centers of spin density distributions of the electron and the hole constituting CTS, θ is the polar angle for the vector of the external magnetic field B0 in the reference frame of the principal axes of the Zero-Field Splitting tensor, which is determined by the magnetic dipolar interaction between the spins of the electron and the hole, and T2 is the transversal relaxation time for electron spins. The dipolar frequency ωd is

where γ is the free electron gyromagnetic ratio and ħ is the Planck constant. The value T2 = 1.35 μs was determined from a monoexponential approximation of two-pulse ESE decay for pristine 1b (Figure S27). The resulting electron–hole distance distribution function for CTS in 1b is again similar to that for OPV BHJ blends reported previously with the most-probable electron–hole distance in the range of 3.5–4 nm [18]. This relatively long distance implies that during charge thermalization after exciton self-splitting, several further charge transfer steps between 1b molecules occur. To prove that the out-of-phase ESE signal in 1b film indeed originates from intermolecular electron transfer, we performed the similar ESE experiment with a laser excitation of 1b molecules isolated in a glassy toluene matrix. In this case, no light-induced ESE signal was observed, indicating that the isolated 1b molecule does not form long-living CTS upon illumination. In other words, the lifetime of the intramolecular CTS in 1b is much smaller than 100 ns (the temporal resolution of our ESE experiment).

Figure 5.

Panel (A): Out-of-phase ESEEM of the pristine 1b (black line) and its numerical simulation according to Equation (1) (red line). Panel (B): Electron–hole distance distribution function for CTS in pristine 1b, obtained as from numerical simulation of the out-of-phase ESEEM. Temperature is 80 K.

It is important to distinguish the intramolecular CTS in 1b detected by the out-of-phase ESE from the intramolecular CTS, which is responsible for the charge-transfer band in the optical spectrum of 1b. The latter can be considered as an electronically excited state with the electron and the hole localized at different fragments of the same 1b molecule. A strong interaction between the electron and the hole leads to the coupling of their spins to the singlet spin state, which does not produce an EPR signal. However, intramolecular charge transfer may precede electron transfer from a photoexcited 1b molecule to a neighboring 1b molecule when the optical transition close to the maximum of 1b absorption spectrum is excited (for example, by illumination at 527 nm in our out-of-phase ESE experiments). In this case, fast exciton dynamics would lead to the formation of the excited state with the lowest energy (intramolecular CTS), which corresponds to the electric polarization of the 1b molecule. Presumably, this polarization facilitates subsequent intermolecular electron transfer. A similar effect is known for photosynthetic light-induced electron transfer. In that case, polarization of the primary excited state (the special pair of the bacterial photosynthetic reaction center) with partial charge separation within the dimer of bacteriochlorophyll molecules ensures the directional electron transfer to the chain of the electron acceptors [28,29]. This similarity extends the analogy between the light-induced charge separation process in natural photosynthesis and organic photovoltaics. Initially, it was proposed on the basis of a similar shape of time-resolved EPR spectra of plant photosystems and polymer/fullerene BHJ blends [30]. The major idea behind this analogy is that both processes require several electron transfer steps between acceptor molecules for reaching the charge separation distance of several nanometers.

The luminescence spectrum of 1b in solution is solvent-dependent (Figure S28). In non-polar solvent (toluene), the PL maximum is observed at 620 nm, while in polar solvent (chloroform), it is shifted to 800 nm. The optical absorption spectra of 1b in these solutions are similar, but the maximum of the charge-transfer band is shifted to a shorter wavelength for the toluene solution. The PL decay time for 1b in these solutions is markedly different (Figure S29). The longer PL decay of 1b in toluene (1.25 ns) compared to chloroform (~60 ps) is typical for compounds undergoing photoinduced intramolecular charge transfer. It is explained by an enhanced interaction between the molecular orbitals of the compound and polar molecules of the solvent [31]. For the chloroform solution, the screening of the Coulombic interaction is strong, which facilitates the intramolecular charge transfer. Due to the high rate of this process, the emitting state is the charge transfer state, and the PL lifetime shortens dramatically. For non-polar solvent, the dielectric screening of the Columbic interaction between the positive and the negative charges within the intramolecular charge transfer state is weak. This leads to an increase in the energy of the intramolecular CTS, which is manifested in the blue shift of the corresponding band in the optical absorption spectrum. This also leads to a low efficiency of the intramolecular charge transfer for the case of excitation of molecular orbitals of 1b, localized on the donor and acceptor moieties, by the light at 450 nm wavelength. In this case, the emitting states correspond to localized orbitals, which can be viewed as the exciton localized on the donor or the acceptor fragments of an 1b molecule. Accordingly, the PL of 1b was much weaker in chloroform solution than in toluene solution, although in both cases, it was too weak to measure the PL quantum yield.

The photoluminescence spectrum of the 1b film (Figure S30) is notably similar to that in toluene solution, showing the maximum at about 700 nm and extending beyond 800 nm. The PL decay for the 1b film has a very weak and slow component with the decay time of 440 ns (Figure S31), which could be attributed to emission from the intermolecular CTS. In this case, the recombination of the electron and the hole is slowed down compared to that for the intramolecular CTS, so the PL lifetime is close to the CTS lifetime estimated from the out-of-phase ESE experiment at temperature 80 K (several microseconds). According to the ESE measurement, the electron and the hole are separated by several nanometers within the intermolecular CTS. Since the rate of the electron transfer falls exponentially with the increase in its distance, a relatively low rate of recombination is expected for the intermolecular charge-transfer state [26]. The difference between the PL lifetime and the out-of-phase ESE decay time can be explained, taking into account that the evolution of the charge-transfer state at the cryogenic temperature is slowed down compared to that at room temperature due to slowed charge diffusion.

In contrast to exciton splitting in a donor/acceptor BHJ blend, exciton self-splitting in pristine 1b does not require exciton diffusion. Therefore, this process can be highly efficient if it is energetically allowed. The driving force for electron transfer from the 1b exciton to the neighboring 1b molecule is mainly ensured by the deep HOMO of 1b governed by the strong electron-accepting property of the NTDPDN unit. Although exciton self-splitting in pristine 1b is expected to be fast and efficient, its photovoltaic performance is rather poor. The plausible explanation is the fast recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes in pristine 1b, which either geminate (within CTS) or non-geminate. The free electrons and holes in the 1b phase are not spatially separated in different phases, in contrast to BHJ materials, where electrons are within the acceptor phase while holes are within the donor phase. For this reason, the reduction in the Langevin recombination rate [32,33,34] does not apply for pristine 1b or other SCOSC active layer materials. Therefore, non-geminate recombination in pristine materials is orders of magnitude faster than that in BHJ materials. Also, since both the electron and hole are strongly localized in 1b, their diffusion is slow; therefore, the geminate recombination is also efficient [35]. The low jSC caused by fast geminate and non-geminate charge recombination is a common problem of SCOSC materials [22,36].

The detrimental effect of exciton self-splitting within an OPV acceptor material is also significant when it is blended with some donor material to form BHJ. This process can enhance the photovoltaic performance only if hole transfer from the acceptor HOMO to the hole HOMO or to the anode is highly optimized. This is not the case for the PBDB-T/1b composite. Based on the similarity of 1b to anthrathiophene-based acceptors [13,35], low charge mobility is expected for 1b. Despite efficient exciton self-splitting in 1b, a significant fraction of electrons and holes generated by this process could undergo recombination within the 1b phase. Presumably, these two effects are responsible for the very poor photovoltaic performance of 1b as a component of the donor/acceptor BHJ. Therefore, the excessively strong push–pull effect in the D-A-type compound used as the acceptor can deteriorate the OPV performance of a potentially efficient BHJ active layer due to exciton self-splitting.

It is highly probable that exciton self-splitting is not limited by the acceptor phase and can occur at the donor phase of some BHJ blends. In this case, it also can cause an unwanted process: the recombination of electrons and holes in the same phase. Therefore, this process is of general significance for BHJ blends, and it is not limited to the specific 1b material studied in the present work. Exciton self-splitting, even when masked by other processes, can still deteriorate the performance of efficient OPV systems. In view of this result, the recent observation of charge photogeneration in pristine non-fullerene acceptor Y6 [37] cannot be unambiguously considered as a process contributing to the high photovoltaic efficiency of Y6. While OPV devices with a Y6-based BHJ active layer have efficiency over 15%, the devices with a pristine Y6 active layer have moderate efficiency below 5%. This reduction is partly due to the efficient charge recombination within Y6, as evidenced by its low external quantum efficiency, contrasting to its strong light absorption. Therefore, exciton self-splitting in Y6 can be detrimental for the photovoltaic performance of the Y6-containing BHJ active layer under certain conditions.

4. Conclusions

Novel A-D-A type molecules with strong electron acceptor units, intended for use in the active layer of OPV devices, clearly demonstrate exciton self-splitting. This channel of photoinduced charge loss was not considered previously. The photoinduced charge-transfer state was detected in the out-of-phase electron spin echo experiments for the pristine 1b film, which proves the efficiency of exciton self-splitting. For the BHJ blend of 1b with a donor polymer PBDB-T, exciton self-splitting in 1b triggers the process involving holes at 1b HOMO, namely the geminate and non-geminate charge recombination within 1b domains. These processes partly explain the rather poor photovoltaic performance of the PBDB-T/1b BHJ blend. Out-of-phase electron spin echo spectroscopy, as a sensitive tool for detecting charge-transfer state formation, can be used for checking the efficiency of exciton self-splitting in films of pristine OPV acceptors or donors. This technique directly evidences that the molecules with the strong intermolecular charge-transfer band are not suitable components of the active layer of efficient OPV devices.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/en19010104/s1, Scheme S1: Synthesis of 1; Figure S1: 1H NMR spectrum (600 MHz, CDCl3) of 3; Figure S2: 13C NMR spectrum (151 MHz, CDCl3) of 3; Figure S3: 1H NMR spectrum (400 MHz, CDCl3) of 4; Figure S4: 13C NMR spectrum (151 MHz, CDCl3) of 4; Figure S5: 1H NMR spectrum (400 MHz, CDCl3) of 5; Figure S6: 13C NMR spectrum (126 MHz, CDCl3) of 5; Figure S7: 1H NMR spectrum (400 MHz, CDCl3) of 6; Figure S8: 13C NMR spectrum (126 MHz, CDCl3) of 6; Figure S9: 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz, CDCl3) of 2a; Figure S10: 13C NMR spectrum (126 MHz, CDCl3) of 2a; Figure S11: 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz, CDCl3) of 2b; Figure S12: 13C NMR spectrum (126 MHz, CDCl3) of 2b; Figure S13: 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz, CDCl3) of 1a; Figure S14: 13C NMR spectrum (126 MHz, CDCl3) of 1a; Figure S15: 1H NMR spectrum (500 MHz, CDCl3) of 1b; Figure S16: 13C NMR spectrum (126 MHz, CDCl3) of 1b; Figure S17: Cyclic voltammetry curves for compounds 1a and 1b (red and blue lines, respectively) in CH2Cl2 solution; Figure S18: HOMO and LUMO for compound 1a (upper and lower figures, respectively) obtained by DFT calculations. The alkyl chains attached to the central fragment are replaced by methyl groups.; Figure S19: HOMO and LUMO for compound 1b (left and right figures, respectively) obtained by DFT calculations. The alkyl chains attached to the central fragment are replaced by methyl groups; Figure S20: Initial and final orbitals corresponding to the longest wavelength optical transitions of 1b (left and right figures, respectively), obtained by DFT calculations; Figure S21: Optical absorption spectra for 1a and 1b (upper and lower panels, respectively), obtained by DFT calculations; Figure S22: Optimized ground state structure of 1a (the upper figure) and 1b (the lower figure) with the characteristic angles. The dihedral angles are shown by the intersection of planes. The alkyl chains attached to the central fragment are replaced by methyl groups; Figure S23: Current density–voltage curve for OPV device with PBDB-T/PC60BM active layer. Red line: under white light illumination with incident power density100 mW/cm2; black line: in dark; Figure S24: AFM image of 1b film cast from chloroform; Figure S25: X-ray diffraction pattern for 1b powder and film; Figure S26: 2D GIXD pattern for 1b film; Figure S27: Two-pulse ESE decay for light-induced charges in pristine 1b obtained without synchronization of lased pulse with microwave echo-forming pulses (black line) and its approximation by monoexponential decay (red line). Temperature 80K, magnetic field corresponds to the maximum of ED EPR spectrum of pristine 1b film; Figure S28: Absorption and photoluminescence spectra of 1b in chloroform and toluene solutions. Excitation wavelength is 450 nm for PL spectra; Figure S29: Photoluminescence decay of 1b solutions in chloroform and toluene, measured at the corresponding emission maxima; Figure S30: Photoluminescence spectrum of 1b film. Excitation wavelength is 375 nm; Figure S31: Photoluminescence decay of 1b film (black line) and its monoexponential approximation (red line). Excitation wavelength is 375 nm; Table S1: The bond angles and dihedral angles for the optimized geometry of 1a; Table S2: The bond angles and dihedral angles for the optimized geometry of 1b.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.V.K.; methodology, L.V.K.; software, A.A.D. validation, L.V.K.; formal analysis, A.S.S.; investigation, D.S.B., E.S.K., M.N.U., I.A.M., A.A.D., M.S.K., V.I.S., A.S.S., E.A.M., L.V.K.; resources, M.N.U.; data curation, I.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S.B.; writing—review and editing, L.V.K.; visualization, E.S.K.; supervision, L.V.K.; project administration, L.V.K.; funding acquisition, L.V.K., V.I.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Russian Science Foundation, grant № 23-73-00072.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Multi-Access Chemical Service Center Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Science for carrying out analytical measurements. The authors are thankful to E. M. Glebov for assistance in measuring the photoluminescence of 1b film and to V. A. Zinov’ev for performing the AFM experiment. Steady state and time-resolved photoluminescence measurements of 1b solutions were supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of Russian Federation project № FSUS-2021-0014.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OPV | Organic photovoltaics |

| EPR | Electron paramagnetic resonance |

| BHJ | Bulk heterojunction |

| A | Acceptor |

| D | Donor |

| HOMO | Highest occupied molecular orbital |

| LUMO | Lowest unoccupied molecular orbital |

| PCE | Power conversion efficiency |

| NFA | Non-fullerene acceptor |

| ATDPDN | 2,2′-(anthra[2,3-b]thiophene-5,10-diylidene)dipropanedinitrile |

| NTDPDN | 2,2′-(naphtho[2,3-b]thiophene-4,9-diylidene)dipropanedinitrile |

| ESE | Electron spin echo |

| CTS | Charge transfer state |

| DFT | Density functional theory |

| ITO | Indium tin oxide |

| PEDOT:PSS | Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate |

| PFN | Poly(fluorine-co-benzotriazole) |

| FM | Field’s metal |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| PBDB-T | Poly[[4,8-bis[5-(2-ethylhexyl)-2-thienyl]benzo[1,2-b:4,5-b′]dithiophene-2,6-diyl]-2,5-thiophenediyl[5,7-bis(2-ethylhexyl)-4,8-dioxo-4H,8H-benzo[1,2-c:4,5-c′]dithiophene-1,3-diyl]] polymer |

| PC60BM | [6,6]-phenyl-C60-butyric acid methyl ester |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| GIXD | Grazing incidence diffraction patter |

| SCOSC | Single-component organic solar cells |

| LEPR | Light-induced EPR |

| ESEEM | ESE envelope modulation |

| CW | Continuous wave |

| DAF | Delay After Flash |

| CV | Cyclic voltammetry |

| PL | Photoluminescence |

References

- Leandro, P.G.M.; Salvadori, F.; Izquierdo, J.E.E.; Cavallari, M.R.; Ando Junior, O.H. The Advancements and Challenges in Organic Photovoltaic Cells: A Focused and Spotlight Review Using the Proknow-C. Energies 2024, 17, 4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deibel, C.; Dyakonov, V. Polymer–Fullerene Bulk Heterojunction Solar Cells. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2010, 73, 096401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeger, A.J. 25th Anniversary Article: Bulk Heterojunction Solar Cells: Understanding the Mechanism of Operation. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brabec, C.J.; Zerza, G.; Cerullo, G.; De Silvestri, S.; Luzzati, S.; Hummelen, J.C.; Sariciftci, S. Tracing Photoinduced Electron Transfer Process in Conjugated Polymer/Fullerene Bulk Heterojunctions in Real Time. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2001, 340, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.C.; Fréchet, J.M.J. Polymer–Fullerene Composite Solar Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P.R.; Kim, M. Polymer Solar Cells: P3HT:PCBM and Beyond. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2018, 10, 013508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yao, H.; Bi, P.; Hong, L.; Zhang, J.; Zu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Qin, J.; Ren, J.; et al. Single-Junction Organic Photovoltaic Cell with 19% Efficiency. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2102420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Sun, S.; Xu, R.; Liu, F.; Miao, X.; Ran, G.; Liu, K.; Yi, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, X. Non-Fullerene Acceptor with Asymmetric Structure and Phenyl-Substituted Alkyl Side Chain for 20.2% Efficiency Organic Solar Cells. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 975–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Brabec, C.J.; Kyaw, A.K.K. Non-Fused Ring Electron Acceptors for High-Performance and Low-Cost Organic Solar Cells: Structure-Function, Stability and Synthesis Complexity Analysis. Nano Energy 2023, 114, 108661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, B.; Ahmad, F.; Sehar Abbasi, M.; Najam, T.; Shoaib Ahmad Shah, S.; Alrowaili, Z.A.; Al-Buriahi, M.S. Synthetic Accessibility-Informed Designing of Efficient Organic Semi-Conductors for Organic Solar Cells. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2023, 831, 140852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papkovskaya, E.D.; Wan, J.; Balakirev, D.O.; Dyadishchev, I.V.; Bakirov, A.V.; Luponosov, Y.N.; Min, J.; Ponomarenko, S.A. Improving the Efficiency of Organic Solar Cells via the Molecular Engineering of Simple Fused Non-Fullerene Acceptors. Energies 2023, 16, 3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureš, F. Fundamental Aspects of Property Tuning in Push–Pull Molecules. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 58826–58851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranov, D.S.; Krivenko, O.L.; Kazantsev, M.S.; Nevostruev, D.A.; Kobeleva, E.S.; Zinoviev, V.A.; Dmitriev, A.A.; Gritsan, N.P.; Kulik, L.V. Synthesis of 2,2′-[2,2′-(Arenediyl)Bis(Anthra[2,3-b]Thiophene-5,10-Diylidene)]Tetrapropanedinitriles and Their Performance as Non-Fullerene Acceptors in Organic Photovoltaics. Synth. Met. 2019, 255, 116097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salikhov, K.M.; Kandrashkin, Y.E.; Salikhov, A.K. Peculiarities of Free Induction and Primary Spin Echo Signals for Spin-Correlated Radical Pairs. Appl. Magn. Reson. 1992, 3, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzuba, S.A.; Gast, P.; Hoff, A.J. ESEEM Study of Spin-Spin Interactions in Spin-Polarised P+QA− Pairs in the Photosynthetic Purple Bacterium Rhodobacter Sphaeroides R26. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1995, 236, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fursman, C.E.; Hore, P.J. Distance Determination in Spin-Correlated Radical Pairs in Photosynthetic Reaction Centres by Electron Spin Echo Envelope Modulation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999, 303, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukina, E.A.; Popov, A.A.; Uvarov, M.N.; Suturina, E.A.; Reijerse, E.J.; Kulik, L.V. Light-Induced Charge Separation in a P3HT/PC 70 BM Composite as Studied by out-of-Phase Electron Spin Echo Spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 28585–28593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.A.; Uvarov, M.N.; Kulik, L.V. Mode of Action of the Third Component in Ternary Organic Photovoltaic Blend PBDB-T/ITIC:PC70BM Revealed by EPR Spectroscopy. Synth. Met. 2021, 277, 116783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannanov, A.L.; Savchenko, P.S.; Luponosov, Y.N.; Solodukhin, A.N.; Ponomarenko, S.A.; Paraschuk, D.Y. Charge Photogeneration and Recombination in Single-Material Organic Solar Cells and Photodetectors Based on Conjugated Star-Shaped Donor-Acceptor Oligomers. Org. Electron. 2020, 78, 105588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsager, L. Initial Recombination of Ions. Phys. Rev. 1938, 54, 554–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liraz, D.; Tessler, N. Charge Dissociation in Organic Solar Cells—From Onsager and Frenkel to Modern Models. Chem. Phys. Rev. 2022, 3, 031305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncali, J.; Grosu, I. The Dawn of Single Material Organic Solar Cells. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1801026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Yokoi, Y.; Hasegawa, N.; Kuroda, S.; Iijima, T.; Sato, T.; Yamamoto, T. Quadrimolecular Recombination Kinetics of Photogenerated Charge Carriers in the Composites of Regioregular Polythiophene Derivatives and Soluble Fullerene. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 107, 083708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukina, E.A.; Uvarov, M.N.; Kulik, L.V. Charge Recombination in P3HT/PC 70 BM Composite Studied by Light-Induced EPR. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 18307–18314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklas, J.; Poluektov, O.G. Charge Transfer Processes in OPV Materials as Revealed by EPR Spectroscopy. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1602226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.A.; Lukina, E.A.; Reijerse, E.J.; Lubitz, W.; Kulik, L.V. Out-of-Phase ELDOR Spectroscopy: A Precise Tool for Investigating Structure and Dynamics of Charge-Transfer States in Organic Photovoltaic Blends. J. Chem. Phys. 2025, 162, 014201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukina, E.A.; Kulikova, A.V.; Uvarov, M.N.; Popov, A.A.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Kulik, L.V. Structure of the Charge-Transfer State in PM6/Y6 and PM6/Y6:YT Composites Studied by Electron Spin Echo Technique. Nanomanufacturing 2023, 3, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatypov, R.A.; Khmelnitskiy, A.Y.; Khristin, A.M.; Shuvalov, V.A. Femtosecond Absorption Band Formation at 1080 and 1020 Nm as an Indication of Charge-Separated States PAδ+ PBδ− and P+BA− in Photosynthetic Reaction Centers of the Purple Bacterium Rhodobacter Sphaeroides. Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 2010, 430, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Romero, E.; Jones, M.R.; Novoderezhkin, V.I.; Van Grondelle, R. Both Electronic and Vibrational Coherences Are Involved in Primary Electron Transfer in Bacterial Reaction Center. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklas, J.; Beaupré, S.; Leclerc, M.; Xu, T.; Yu, L.; Sperlich, A.; Dyakonov, V.; Poluektov, O.G. Photoinduced Dynamics of Charge Separation: From Photosynthesis to Polymer–Fullerene Bulk Heterojunctions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 7407–7416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slama-Schwok, A.; Blanchard-Desce, M.; Lehn, J.M. Intramolecular Charge Transfer in Donor-Acceptor Molecules. J. Phys. Chem. 1990, 94, 3894–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaee, S.; Stolterfoht, M.; Neher, D. The Role of Mobility on Charge Generation, Recombination, and Extraction in Polymer-Based Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1703355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuhara, T.; Tamai, Y.; Ohkita, H. Nongeminate Charge Recombination in Organic Photovoltaics. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2020, 4, 4321–4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Van Der Zee, B.; Liu, W.; Markina, A.; Fan, H.; Yang, H.; Cui, C.; Li, Y.; Blom, P.W.M.; et al. Reduced Bimolecular Charge Recombination in Efficient Organic Solar Cells Comprising Non-Fullerene Acceptors. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobeleva, E.S.; Popov, A.A.; Baranov, D.S.; Uvarov, M.N.; Nevostruev, D.A.; Degtyarenko, K.M.; Gadirov, R.M.; Sukhikh, A.S.; Kulik, L.V. Origin of Poor Photovoltaic Performance of Bis(Tetracyanoantrathiophene) Non-Fullerene Acceptor. Chem. Phys. 2021, 546, 111162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, N.; Brabec, C.J. Single-Component Organic Solar Cells with Competitive Performance. Org. Mater. 2021, 03, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sağlamkaya, E.; Musiienko, A.; Shadabroo, M.S.; Sun, B.; Chandrabose, S.; Shargaieva, O.; Lo Gerfo, M.G.; Van Hulst, N.F.; Shoaee, S. What Is Special about Y6; the Working Mechanism of Neat Y6 Organic Solar Cells. Mater. Horiz. 2023, 10, 1825–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.