Abstract

Facing the decarbonization trend in power systems, there appears to be a growing requirement on agile response and delicate supply from electricity suppliers. To accommodate this request, it is of key significance to precisely extrapolate the upcoming power load, which is well acknowledged as VSTLF, i.e., Very Short-Term Power Load Forecasting. As a time series forecasting problem, the primary challenge of VSTLF is how to identify potential factors and their very long-term affecting mechanisms in load demands. With the help of a public dataset, this paper first locates several intensely related attributes based on Pearson’s correlation coefficient and then proposes an adaptive Informer network with the probability sparse attention to model the long-sequence power loads. Additionally, it uses the Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) for ablation and interpretation analysis. The experiment results show that the proposed model outperforms several state-of-the-art solutions on several metrics, e.g., 18.39% on RMSE, 21.70% on MAE, 21.24% on MAPE, and 2.11% on R2.

1. Introduction

Driven by the decarbonization trend in power systems, it is of key significance to accurately predict upcoming power loads and efficiently respond to them for energy suppliers. On the one hand, with the high-quality development of globalization, we are witnessing a booming trend in the electricity load around the world. For instance, China’s national electricity load in 2023 has reached 9.2 billion kilowatt hours with the increase rate as high as 6.7%. On the other hand, the carbon emission of the power industry still accounts for over 40% of the total, and its CO2 intensity is 0.56 kg per kilowatt hour, which is still higher than the average in the Asia Pacific market. The decarbonization demand not only calls for the continuous expansion of green energy but also urges us to improve the management, operation, and maintenance of current power grids [1,2]. One of the core issues behind this trend is accurately forecasting the upcoming power demand.

As a time series analysis task, power load forecasting aims to infer the requirement of the next period by historical modeling. Overall, there are four different timescales for power planning: very short-term, short-term, medium-term, and long-term [3]. The very short term, known as Very Short-Term Load Forecasting (VSTLF), spans from minutes to hours, focusing on agile operation and safety management, including equipment maintenance, load distribution, unit on/off, and pricing. Because of its significant role in safety, reliability, and efficiency, VSTLF has drawn considerable attention for years [4]. Since the aleatoric uncertainty, VSTLF is the most challenging job for its narrow time window nature. Also, as a long-term time series problem, the primary challenge of VSTLF is how to identify potential factors and quantify their affecting mechanisms, especially the long-term ones, in load history.

Although many researchers have introduced diverse solutions, it is still an open question for most power grids to continuously improve precision and interpretability when predicting very short-term power loads. After conducting a literature review, we found that most researchers tend to model VSTLF as Machine Learning (ML) problems, i.e., shallow models or deep models. Employed ML models include Auto-Regressive and Moving Average (ARMA), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Gaussian Regression (GR), and Random Forest (RF). These shallow ML models are convergent with small-scale power load history, but their fitting performance cannot be efficiently improved with the extending pace of the data. On the contrary, because of their capability of parsing large load dataset, deep neural networks have recently become popular for addressing VSTLF with diverse metrics, e.g., Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks, Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) and Transformers. The driving forces behind this trend include: (1) deep models’ powerful nonlinear modeling capabilities (through cascading multiple hidden layers), which can effectively model complex correlations across time, weather, and season attributes; (2) their end-to-end fitting nature, including preprocessing, feature engineering and parameter backpropagating, which can lay off considerable human workload and speed up the model construction process. However, it is still a challenge to build a powerful model which can achieve both high prediction performance and high interpretability. In this paper, we propose an improved Transformer network with interpretable capability, called Informer, to fine capture the affecting correlations in very long sequences.

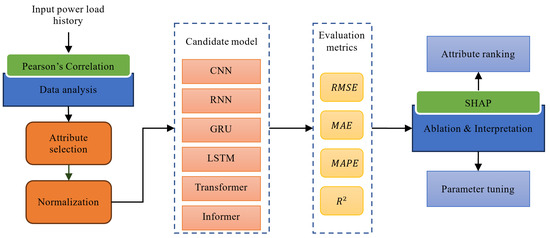

We depict the framework of this study in Figure 1. Based on historical power loads, we first apply statistical analysis, anomaly detection, and normalization to preprocess the data and roughly identify the most significant attributes on VSTLF, and then train several deep neural networks where the Informer model turns out to be more efficient. For evaluation, we compare our model with several cut-edge solutions on four regression metrics. Finally, we conduct the ablation and interpretation test to interpret the deep model and rank feature importances. The contribution of this study is twofold: (1) A revised Transformer model (Informer) for effectively and efficiently modeling VSTLF’s very long-term correlations. (2) Attributing importance scores, which may provide insights for future feature engineering.

Figure 1.

The framework of this study.

2. Related Work

As a popular direction, power load forecasting has long been modeled as a machine learning problem, wherein both shallow models and deep models are adopted.

2.1. Shallow Models

Sansa et al. [5] took the ARMA model to forecast a winter day’s solar radiation, and they also applied the Dickey–Fuller test to study the stationarity of this series. Based on ARMA and SVM, Nie et al. [6] proposed a hybrid model to predict the linear fundamental and nonlinear sensitive parts of the power load. First, they utilized ARMA to predict the daily load and then used SVM to correct the predicted deviation. Sharma et al. [7] introduced a stepwise learning approach and developed a linear state–space model. They used timely local linear correlation to approximate the underlying nonlinear problem and effectively extended the standard GR model. He et al. [8] designed a power load forecasting model based on SVR with electricity price data, which significantly improved the prediction performance. Lu et al. [9] proposed an RF model to forecast the power load of the next day, and their contribution lies in the integration of expert selection strategies; thus, they are able to capture uncertain situations, such as high temperatures, religious activities, and holidays. Hu et al. [10] designed a data-driven evolutionary ensemble learning prediction model that combined multimodal evolutionary algorithms, fully weighted vector angles, and shift density estimation to develop an intelligent decision support scheme to improve the performance of ensemble learning models based on random vector functional linkage networks.

Recently, shallow models are rare to spot because of their limited forecasting performance. But, when the data needed are quite limited, most of them are still adequate in practice.

2.2. Deep Models

With the rapid development of deep learning technologies, many neural network-based models have recently become common to observe. The driving force behind this phenomenon is that deep models can provide powerful nonlinear modeling capabilities by cascading multiple hidden layers; hence, they can more effectively fit complex correlations across time, weather, and seasonal attributes. For instance, Liu et al. [11] proposed an Elman network-based model with an adapted Particle Swarm Optimization method for backpropagation. They highlighted the difference between the prediction of the network and the result of the particle swarm fitness function. This move can adapt to many nonlinear laws and learn independently after inputting the climate data and historical load data. Aseeri [12] applied GRU to forecast day-ahead power loads, and the empirical results showed that the proposed forecasting methodology yields outstanding performance. Specifically, they highlighted the distinction between network prediction and particle swarm’s fitting result. They have validated that this technique can generate into many nonlinear laws and independently mine latent knowledges from load history. Lai et al. [13] proposed a Radial Basis Function (RBF) network and trained it by minimizing the local generalization errors in short-term and medium-term load forecasting. LSTM and wavelet decomposition were utilized to extract time series features. Finally, multiple RBF networks were fused into an ensemble model based on the local generalization error-decreasing method. Wan et al. explored a composite model which comprised CNN, LSTM, and the attention mechanism to address the challenge of information loss due to excessively long input time series data [14,15]. Moreover, Wang et al. [4] made good use of a time CNN to extract latent patterns on temporal correlations beneath power loads; meanwhile, they built a composite model through integrating the CNN with the lightweighted gradient elevator approach. Alsharekh et al. [16] published a two-stage predicting framework, i.e., data preprocessing and core attribute mining upon deep residual CNN. Additionally, the output is forwarded to an LSTM network to learn sequential knowledge. Ullah et al. [17] applied CNN and LSTM to discover spatiotemporal correlations and generate corresponding feature maps, and then forwarded them to a GRU network for learning. Fan et al. [1] proposed a new hybrid model where Empirical Wavelet Decomposition is used to extract statistical features, the LSTM/RNN model is selected as the learning model, and the Bayesian optimization algorithm is adopted to optimize the parameters. Focusing on the security concern across distribution transformer supply zones, Feng et al. introduced a federated model-agnostic meta-learning approach with pre-training, which can address the heterogeneous problem in different zones [18]. Facing the multi-node load forecasting issue in power networks, Tan et al. applied load data from the New Zealand distribution network and proposed a soft sharing multi-task method upon the gated temporal convolutional network and GRU [19].

To sum up, deep models have significantly accelerated VSTLF in several scenarios using many a metric, and many closely correlated features have been observed in practice. However, due to latent very long-term affecting factors, e.g., precipitation, humidity, temperature and holidays, it is still a challenge to efficiently mine and understand these correlations, and train high-performance models with guaranteed interpretability.

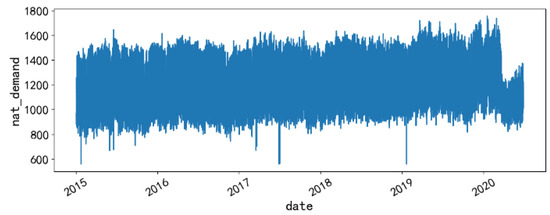

3. Dataset

To best understand the power load history and foster the development of an efficient VSTLF model, we select a real electricity load history dataset supported by the Republic of Panama, where three cities of the country, i.e., David, San Diego, and Tocumen, are considered. The history period spans from 2015 to 2020, and the sampling frequency is once per hour, resulting in a total volume of 48,048 samples without any missing values. The data distribution is shown in Figure 2. The dataset includes 16 attributes, such as precipitation, relative humidity, temperature, and wind speed for each city, school, holiday_ID, holiday, and load history (nat_demand) for the country. And, our forecasting goal is the national electricity load in the next hour. Attributes with their explanations and Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) are shown in Table 1. The mean of VIFs is 6.33, illustrating that a multicollinearity issue is present in the dataset.

Figure 2.

Power load distribution of the dataset.

Table 1.

Attributes of the dataset.

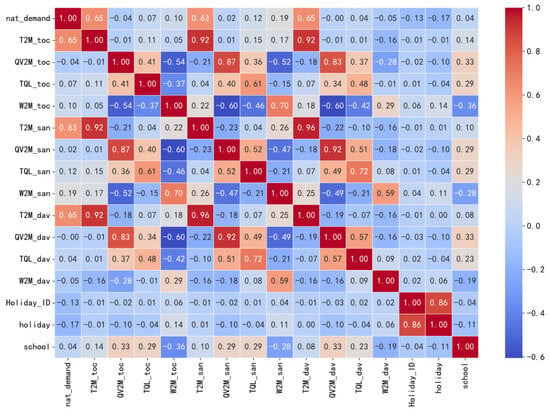

We adopt Pearson’s correlation analysis to evaluate every feature’s significance to the power load, and the results are depicted in Figure 3. Since QV2M_dav has little contribution, we have removed it from the attribute list. Through box-plot-oriented detection, we found that there are outliers concerning some features. Specifically, for any outliers that underflow the lower inner fence, we reset their value to Q25% −1.5IQR; whereas, for any outliers that overflow the upper inner fence, we reset their value to Q75% + 1.5IQR. Among them, Q25% and Q75% are the upper and lower quartiles, respectively, and IQR denotes the Interquartile Range of each attribute.

Figure 3.

Analysis using Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

Then, we normalize these features using the classic maximum and minimum method (see Equation (1)):

where is the original feature value, is the normalized feature value, and and are the minimum and maximum values of the corresponding feature, respectively. Moreover, after obtaining the final output of our model, we perform the inverse normalization according to Equation (2) to arrive at the original regression values.

4. Methodology

As state-of-the-art solutions, deep neural network-based models are widely applied in VSTLF. However, since the long sequence in the time series, the very short prediction window and the quantity of latent affecting attributes, it is still an open question calling for better solutions. In this section, we train a revised Transformer model to fit the dataset, called Informer [20], to better mine the complicated correlations in the extended power load time sequences.

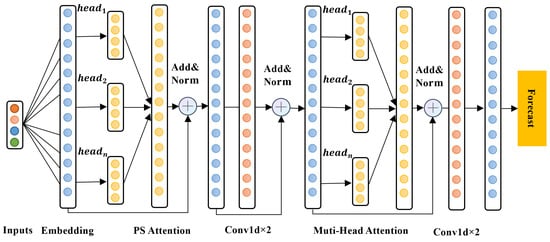

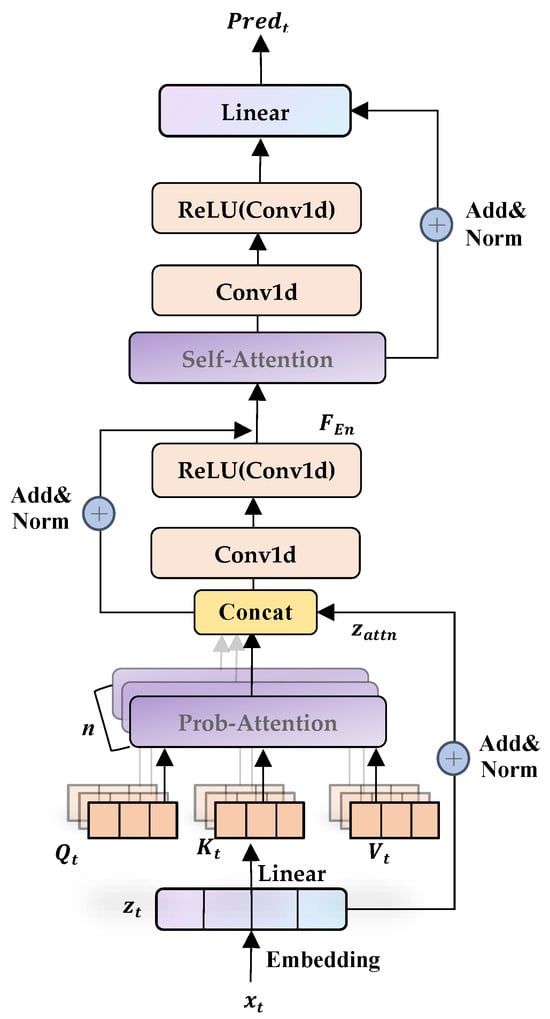

The architecture of the proposed model is shown in Figure 4, where the normalized data are processed through some layers before arriving at the ultimate output for forecasting. Along the processing sequence, these layers are embedding, Probability Sparse (PS) attention, convolution, multi-head attention, and second convolution. The primary contribution of this network lies in the PS attention layer, which selects important attention weights through probability sampling and significantly improves computational efficiency of long sequences as compared with traditionally fully connected attention mechanisms, while ensuring the accuracy of attention distribution.

Figure 4.

The proposed model.

The workflow of the model is depicted in Figure 5 in detail, and its corresponding algorithm is depicted in Algorithm 1. At the beginning, we apply three different types of embeddings to vectorize the power load history into X, i.e., token-oriented, position-oriented, sequence-oriented embeddings. As so, the feature space of the time series data is converted into a high-dimensional feature vector highlighted for subsequent processing (line 1). Then, we compute X’s query Q, key K and value V by a linear layer (line 2) and a multi-head attention activation function (SoftMax, line 3), the output of which is further forwarded into the PS attention layer to capture global correlations across time sequences, wherein each head works independently to calculate its attention weight and explore corresponding features.

Figure 5.

The Informer architecture.

Based on the classic attention mechanism, the PS attention method selects sparse attention weights through probability sampling, with which the computing complexity is greatly reduced from O(L2) to O(LlogL), where L is the input length. Specifically, the PS attention adopts a randomly generated matrix to mask QKT queries, which can be updated by continuous backpropagation. By limiting the quantity of queries, the PS attention is valuable and efficient for very long sequence correlations. With respect to our model, the attention score E is further normalized using the dimension of weight matrices, in case the value of QKT is oversized (line 3). To ensure that the current power load can only be derived from previous time steps, a Triangular Causal Mask (maskc, a lower triangular matrix) is generated. After that, we take the SoftMax function to calculate the attention score. Finally, we apply another stochastically generated probability mask for dropout (line 4). Through a second SoftMax, we arrive at the final attention score by concatenation (line 5).

Then, a convolutional layer is proposed to down sample the feature vector, which can shorten sequence length and enhance the capability, as well as the efficiency, of attribute engineering; after the convolution process, we activate its output based on the ReLU function (line 6). Next, we calculate the layer normalization and residual connectivity (line 7) and settle on the product of the encoder as (line 8). With this processing technique, the training process will be accelerated and stabled.

Base on the encoder, we then move onto the decoder. The detail is adding and normalizing all muti-heads’ attention scores (line 9) and concatenating it with (line 10). In the following process, we compute the layer normalization and residual connectivity (line 11) and predict the power load using another linear layer (line 12).

| Algorithm 1: Informer |

| Input: : embedding for token, positional and time feature WQ, WK, WV, : weight matrices for attention computing : weight matrices of the linear transformation : Outputs of attention heads bf1, bf2: biases for embedding and feed forward : dimension of weight matrices ReLU(x): activation function of σ(x): activation function Softmax(x): activation function Softmax Dropout: A model training hyperparameter that represents the probability of randomly dropping neurons. Bernoulli: The Bernoulli distribution, which represents success (denoted as 1) and failure (denoted as 0). : : Output: : the output power demand at the next time series |

| 1 Calculate the Embedding of input as 2 Calculate the Q, K, V matrices as 3 Calculate a head attention score as 4 Calculate a head Probability Sparse Attention as 5 Calculate the Muti-head PS Attention as 6 Calculate the 1D convolution as 7 Calculate layer normalization and residual connectivity as 8 Compute the output of encoder as 9 Calculate the Muti-head Self Attention of Decoder as 10 Calculate 1D convolution of Informer Decoder: 11 Calculate layer normalization and residual connectivity as 12 Calculate the prediction at time t as |

5. Experimental Results

In this section, we build the testbed, select four evaluation metrics, validate our model, and compare its performance with several state-of-the-art deep neural networks and their combinations, such as the Transformer, Transformer-LSTM, Transformer-BiLSTM, etc. The VSTLF task is simulated by adopting seven hours of power loads to forecast the next hour’s demand. The testbed is built on a high-performance computing server with PyCharm 2022 in Anaconda 3 and PyTorch. A detailed configuration of the environment is shown in Table 2. And the code of this study has been published at https://github.com/598875122/VSTLF (accessed on 23 July 2024).

Table 2.

The testbed setting.

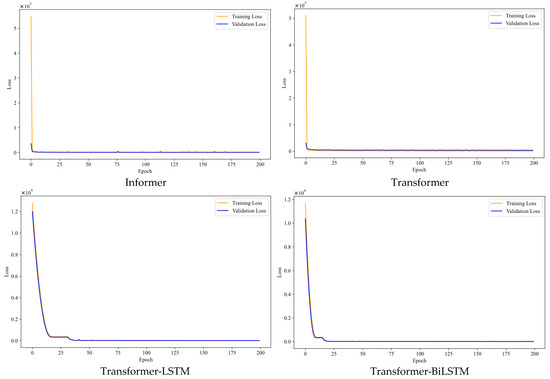

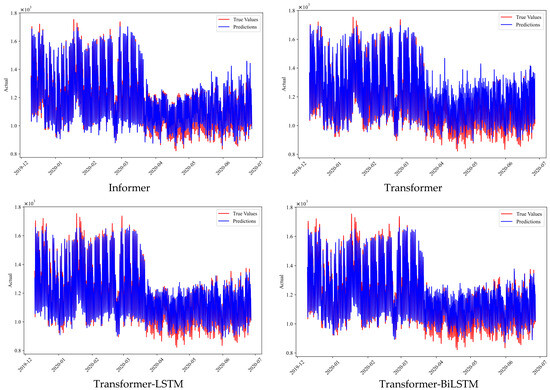

In the training process, we select MSE as the loss function. Additionally, we also pick Root Mean Square Error (RMSE, Equation (3)), Mean Absolute Error (MAE, Equation (4)), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE, Equation (5)) and Coefficient of Determination (R2, Equation (6)) as metrics to evaluate our model. Wherein, denotes the ground-truth value and denotes the forecasted value, respectively. Detailed settings for super parameters are listed in Table 3 and their losses are shown in Figure 6. We record their forecasting procedures in Figure 7.

Table 3.

Related hyperparameter settings.

Figure 6.

Losses of different models.

Figure 7.

Fittings of different models.

5.1. Training and Validation

Based on 5-fold cross validation, Figure 6 and Figure 7 compare training losses and validation losses of Informer, Transformer, Transformer-LSTM, and Transformer-BiLSTM in 200 epochs. From these figures, we can observe that single models converge faster than compound ones and Transformer-LSTM takes about double the time (25 epochs) to fit than Transformer-BiLSTM does (12.5 epochs). Moreover, comparing training and validation curves, hybrid models maintain shorter distances than individual ones. In detail, Transformer-BiLSTM slightly overtakes Transformer-LSTM in “how soon the validation curve merges into the training loss”, i.e., 12.5 epochs versus 42 epochs. For the stability of loss curves, Informer and Transformer-LSTM fluctuate on some level, but Transformer and Transformer-BiLSTM appear smooth.

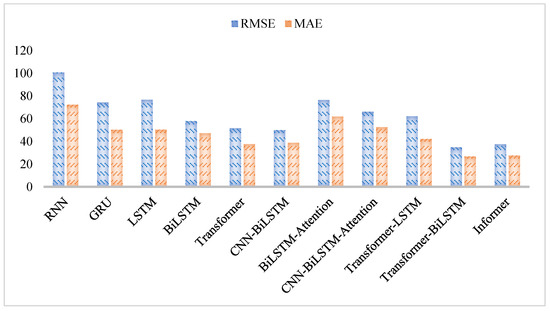

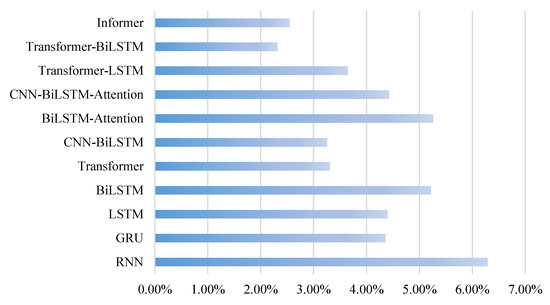

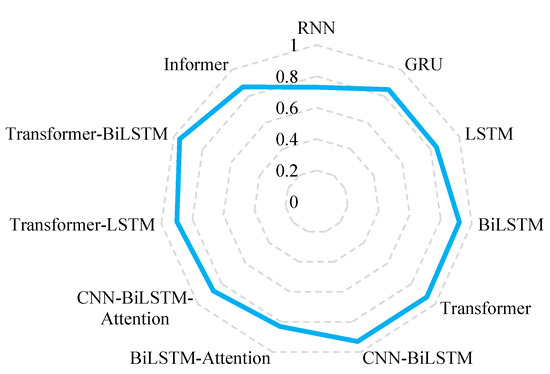

We take extra models (RNN, GRU, LSTM, BiLSTM, CNN-BiLSTM, BiLSTM-Attention, and CNN-BiLSTM-Attention) and compare their performances in Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 and Table 4. From these results, we can see that the Informer model outperforms the rest on almost all metrics. This scene can be explained by the PS attention, which not only combines the probability mask and the dropout mechanism and enhances the model’s regularization ability on a longer series, but also retains the Multi-Head Attention mechanism and improves embedding capability.

Figure 8.

Model performance on RMSE and MAE.

Figure 9.

Model performance on MAPE.

Figure 10.

Model performance on R2.

Table 4.

Performance comparison.

In addition to Informer, the Transformer-BiLSTM also achieves great performance, where its score on R2 is better than Informer’s. This phenomenon validates the theory that, by using a hybrid model integrating two models with good capability on capturing long sequence correlations, we can also approach the regression peak. From Transformer-LSTM’s inefficiency, we might say that correctness with backward modeling is essential for VSTLF. Also, we find that most hybrid models perform better than single models, e.g., CNN-BiLSTM vs. BiLSTM, Transformer-BiLSTM vs. Transformer, which echoes state-of-the-art studies found by previous researchers. However, there are noises, e.g., BiLSTM with attention vs. BiLSTM, CNN-BiLSTM with attention vs. BiLSTM. Though attention mechanisms are pervasively applied in a variety of fields recently, they do not perform well in our scenarios, i.e., the attention calculation procedure not only falls short to unveil latent correlations among sequential power loads, but also misleads models to arrive at inappropriate weight matrices.

Overall, the Transformer family overtakes the LSTM family, and the classic RNN architecture holds the base line. This case validates Transformer’s powerful ability in modeling long-term relationships and its generalization competence as a cutting-edge technique for a wide range of applications.

On the metric of training cost (see Table 4), RNN can become convergent in the least time (520.07 s). With respect to the Transformer family, the vanilla model with the basic attention fits the fastest (2059.43), while the Transformer with BiLSTM is lags way behind (3390.80 s). The phenomenon that the Informer with the sparse attention requires more time to mine the power demand pattern could be explained by the fact that the PS attention with mask matrices is more difficult to train than the dense attention. The ranking list of fitting times echoes the complexity differences across diverse models.

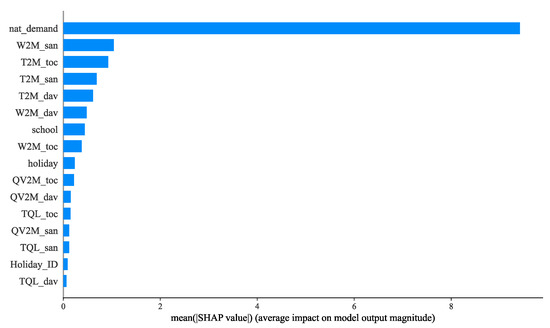

5.2. Ablation and Interpretation

To further understand the proposed model as well as the public dataset, we conducted several ablation and interpretation tests to quantify each attribute’s contribution to the VSTLF task. It is acknowledged that deep neural networks are often referred to as “black box models” because of their difficulty with interpretability. To address this issue, we applied the Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) method [21] to improve our models’ local interpretability and global interpretability. We constructed a linear model based on the optimal Shapley value, and then use this to explain the output. Also, through interpretability analysis, we could quantify every attribute’s contribution on the short-term power load predictive task.

Figure 11 shows the details of feature importance ranking. The top five attributes are (nat_demand), San Diego’s wind speed (W2M_san), Tocumen’s temperature (T2M_toc), San Diego’s temperature (T2M_san), and David’s temperature (T2M_dav), whereas San Diego’s precipitation (TQL_dav), holiday ID, and David’s precipitation (TQL_dav) denote the least impact. Although there is the problem of multicollinearity (see Table 1), this ranking list still provides an important message, e.g., temperature is of greater significance than relative humidity and the wind speed of San Diego is more representative than the speeds of the other two cities. In practice, one can remove any highly duplicated attributes before model fitting.

Figure 11.

Attribute ranking with SHAP.

To further weigh their significance, we enumerated four feature selection strategies and retrained the Informer model. The first strategy is raw-16, which stands for the complete set of all attributes; the second strategy is Pearson-15, which denotes 15 features without QV2M_dav because of its limited impact; the third strategy is Pearson-5 representing the top five features using Pearson’s method; and the last strategy is SHAP-5, which only adopts the top five attributes sorted by SHAP. Their fitting results on RMSE, MAE, MAPE and R2 are shown in Table 5. To further analyze the multicollinearity of the top five features, we calculated their VIFs in Table 6. Based on Table 6, we know that the problem of multicollinearity still exists, especially among the three cities’ temperatures. Our solution suggests that a revised Transformer is not a pure linear regression model and its effectiveness is preserved.

Table 5.

Performance comparison of Informers with different attribute sets.

Table 6.

The VIF distribution among the top 5 attributes.

From Table 5, we can see that the SHAP-5 subset achieves the best performance on every individual metric. It not only overtakes Person-5 but also surpasses the other two (with much larger attribute sets) by a considerable margin. The result validates that the SHAP interpretation is more suitable than the Pearson correlation coefficient. This could be attributed to their differences on theoretical bases. SHAP takes effect based on the Shapley value of game theory, whereas Pearson’s correlation coefficient only works in linear correlations. From this phenomenon, we can argue that there exists nonlinear connections among these attributes. Last but not the least, because the performance on the attribute subset (SHAP-5) is better than the complete set (raw-16), we argue that the filtered 11 attributes not only contribute less to VSTLF, but they are also accompanied by substantial noises.

6. Conclusions

With the decarbonization trend in energy systems, it is important to precisely predict the next hour’s power loads. In this paper, we introduced a revised Transformer-based model with the Probability Sparse attention mechanism, which performs better on long-term correlation mining in VSTLF onto a Panama power load dataset. The experiment results and comparisons demonstrate that it overtakes many state-of-the-art solutions on several metrics by considerable margins, e.g., 18.39% on RMSE, 21.70% on MAE, 21.24% on MAPE, and 2.11% on R2. But, the training cost of the revised model is three times longer than the vanilla Transformer. We also adopt the SHAP interpretation to rank attribute significances and verify that the SHAP fits VSTLF better than the Pearson correlation coefficient technique does. The top five attributes found contributing to VSTLF are power demand, San Diego’s wind speed, Tocumen’s temperature, San Diego’s temperature, and David’s temperature. In the future, we plan to cut the attention part’s time complexity and then validate the model with more datasets.

Author Contributions

Z.Y.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Software. J.L.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. H.W.: Methodology, Validation, Visualization. C.L.: Validation, Visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is partially supported by Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No. 22010500900 and NO. 21DZ1205000).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

It is adopted under the GUN General public License v3.0.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ernestojaguilar/shortterm-electricity-load-forecasting-panama (accessed on 6 April 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Fan, G.-F.; Han, Y.-Y.; Li, J.-W.; Peng, L.-L.; Yeh, Y.-H.; Hong, W.-C. A hybrid model for deep learning short-term power load forecasting based on feature extraction statistics techniques. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ghadi, Y.; Adnan, M.; Ali, M. Load forecasting techniques for power system: Research challenges and survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 71054–71090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, Q.; Wu, X.; Tang, J.; Shi, Y.; Xie, C. Review of load forecasting based on artificial intelligence methodologies, models, and challenges. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 210, 108067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Zeng, X.; Kong, Y.; Sun, S.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y. Short-Term Load Forecasting for Industrial Customers Based on TCN-LightGBM. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 36, 1984–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansa, I.; Boussaada, Z.; Mazigh, M.; Mrabet Bellaaj, B. Solar radiation prediction for a winter day using ARMA model. In Proceedings of the 2020 6th IEEE International Energy Conference (ENERGYCon), Gammarth (Virtual), Tunis, Tunisia, 28 September–1 October 2020; pp. 326–330. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, H.; Liu, G.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Hybrid of ARIMA and SVMs for short-term load forecasting. Energy Procedia 2012, 16, 1455–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Majumdar, A.; Elvira, V.; Chouzenoux, E. Blind Kalman filtering for short-term load forecasting. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 35, 4916–4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Liu, R.; Han, A. Short-Term Power Load Probability Density Forecasting Method Based on Real Time Price and Support Vector Quantile Regression. Proc. CSEE 2017, 37, 768–775. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Kong, Z.; Zhang, C. Short-term load forecasting based on hybrid optimized random forest regression. Eng. J. Wuhan Univ. 2020, 53, 704–711. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Qu, B.; Wang, J.; Liang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, K.; Li, Y.; Qiao, K. Short-term load forecasting using multimodal evolutionary algorithm and random vector functional link network based ensemble learning. Appl. Energy 2021, 285, 116415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yin, Y. Power load forecasting considering climate factors based on IPSO-elman method in China. Energies 2022, 15, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aseeri, A.O. Effective RNN-Based Forecasting Methodology Design for Improving Short-Term Power Load Forecasts: Application to Large-Scale Power-Grid Time Series. J. Comput. Sci. 2023, 68, 101984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.S.; Yang, Y.; Pan, K.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, H.; Ng, W.W.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, T.; Shahidehpour, M. Multi-view neural network ensemble for short and mid-term load forecasting. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 36, 2992–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, A.; Chang, Q.; Khalil, A.-B.; He, J. Short-term power load forecasting for combined heat and power using CNN-LSTM enhanced by attention mechanism. Energy 2023, 282, 128274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Huang, W.; Hu, G.; Li, J. Ultra-short term power load forecasting based on CEEMDAN-SE and LSTM neural network. Energy Build. 2023, 279, 112666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharekh, M.F.; Habib, S.; Dewi, D.A.; Albattah, W.; Islam, M.; Albahli, S.J.S. Improving the efficiency of multistep short-term electricity load forecasting via R-CNN with ML-LSTM. Sensors 2022, 22, 6913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, F.U.M.; Ullah, A.; Khan, N.; Lee, M.Y.; Rho, S.; Baik, S.W. Deep Learning-Assisted Short-Term Power Load Forecasting Using Deep Convolutional LSTM and Stacked GRU. Complexity 2022, 2022, 2993184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Shao, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, F. Short-term Load Forecasting of Distribution Transformer Supply Zones Based on Federated Model-Agnostic Meta Learning. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2025, 40, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Hu, C.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Li, Z. Multi-node load forecasting based on mulfti-task learning with modal feature extraction. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 112, 104856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, S.; Peng, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, W. Informer: Beyond Efficient Transformer for Long Sequence Time-Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Fifth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-21), Virtual Conference, 2–9 February 2021; Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 11106–11115. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 3–9 December 2017; Neural Information Processing Systems Foundation: Long Beach, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).