Abstract

This paper proposes an analysis of different logics (heuristic and linear) of managing renewables scenarios including two different operating conditions and their relative degradation: fixed and variable point. The synergy between two storage technologies, such as Li-ion batteries and the hydrogen power-to-power solution (electrolyzer, H2 tank, and fuel cells), is evaluated to ensure the balance of the power grid. This paper presents a numerical model of the smart grid developed in MATLAB/Simulink. A detailed performance evaluation of each component was performed to meet an electrical load (30 kW-peak) of a smart renewable energy community. From the optimization process, a fuel cell of 6 kW, an electrolyzer of 18 kW, a tank of 40 m3 at 200 bars, as well as a battery of 75 kWh were selected. The fuel cell operates during autumn and winter due to the lack of photovoltaic power generation, while its contribution is reduced during the summer period. In the heuristic logic, the minimum and maximum hydrogen levels are 18% and 60% of the tank volume (40 m3), respectively, while in the linear logic, they are 33% and 65%. The average value of the state of charge (SOC) of the battery is similar in both logics (0.51 vs. 0.53). Regarding hydrogen produced from the electrolyzer, the linear logic allows it to produce a quantity 7% higher than the heuristic one; therefore, the linear logic allows it to properly manage the electrochemical systems. The dynamic operation results in more significant degradation of hydrogen systems, making them less suitable; thus, to preserve the devices (up to 25% of lifetime more), a fixed-point operation is recommended. The cost comparison does not show relevant differences between the two scenarios, while a steep increase in the costs is shown when the fuel cell is operated in dynamic mode. Finally, the total emissions associated with renewable microgrids are 30 times lower than the traditional grid scenario, demonstrating the potential of renewable energy communities.

1. Introduction

The need to meet the worldwide increasing demand for electricity (and more generally, energy) has caused a surge in the use of fossil fuels, leading to a rapid depletion of conventional sources, as well as an increase in global warming and other problems related to pollutant emissions. In 2023, the IEA [1] reported that global natural gas demand grew fvby 0.5%, leading to global emissions of 37.4 Gt CO2, an increase of 1.1 Gt CO2 compared to 2022. The need to limit this continuous growth represents an important driver for a deeper penetration of renewable resources to support electricity and thermal demand. Solar PV and wind-based electricity production showed the fastest growth (30% and 29%, respectively, equivalent to 135 and 125 TWh/year) [2]. Renewable electricity capacity additions reached approximately 507 GW in 2023, almost 50% higher than in 2022 [3]. The intermittent nature of the renewable sources poses a relevant challenge for energy providers: to guarantee continuous energy availability, a connection to the national transmission grid, as well as the use of either conventional electricity generators or electrical storage systems, is required. In isolated grids, auxiliary power units, often using diesel fuel, must be employed. This solution is inefficient, as these small auxiliary units usually have small efficiency (30%), and their emissions can be relevant [4,5]. Conversely, electricity storage systems can be successfully employed, with high efficiency, in applications where renewable energy sources are abundant, thus improving the matching between electricity production and load demand [6]. Electrochemical storage systems, namely batteries, have proven to be efficient and reliable for short–medium-term electricity storage (from minutes to a few days) [7]. However, many alternative solutions can be considered depending on global power/energy demand, final uses, storage duration, and capacity requirements. In this framework, hydrogen has attracted increasing interest in recent years due to its capability for long-term (seasonal) and large-scale energy storage as well as for the multiple end uses: smart mobility, power (co-)generation, chemicals (ammonia, methanol), hard to abate industry (steel, refineries, ceramic) [8,9]. In the power sector, almost all the relevant players sporadically declare the availability of multi-MW gas turbines working with pure hydrogen [10]. For small-range power applications (up to 1 MW), polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs) represent the optimal solution in terms of efficiency (around 50%) and intermittent operation (operative in less than 1 min) [11]. The heart of this technology is the MEA (membrane electrode assembly): a polymer membrane, as electrolyte, and two catalyst layers [12,13]. Several technical solutions and materials have been tested and industrially produced [14]. Since PEMFCs are fed with pure hydrogen (or, in very few cases and small power units, methanol), the only chemical product at the cathode is pure water. Furthermore, if green hydrogen is used, i.e., produced by water electrolysis and renewable electricity [15], greenhouse gas emissions could be fully neutralized. Admittedly, the penetration of hydrogen technology has several limitations. For instance, the entire hydrogen storage process (electrolysis, storage, and power production through fuel cells) is much less efficient (around 30%) than batteries (85%); the technology cost remains high (although this could decrease with mass production [16]); the start-up phase is longer compared to batteries [17]. Batteries are well-suited for short-term flexibility needs, but they are not ideal for long-term storage, as self-discharge becomes significant for weekly or longer storage [18]. Hydrogen-based energy storage, in contrast, is suitable for long-term (seasonal) energy storage [19]. Therefore, hybrid schemes including both hydrogen and battery storage (hybrid energy storage systems—HESS), are worth investigating and optimizing. Many researchers have successfully simulated hybrid energy systems, introducing hydrogen technologies for long-term storage of electricity energy produced by renewable sources. Bensmail et al. [20] modeled a hybrid photovoltaic/fuel cell system for stand-alone applications such as telecoms or pumping systems. Ceylan et al. [21] modeled a hybrid system combining photovoltaic and hydrogen technologies (electrolysis, storage and PEMFC), showing that coupling intermittent PV production with PEMFC is necessary to supply continuous electricity throughout the year. Additionally, the low-temperature (about 60–70 °C) heat produced by PEMFC was used for greenhouse heating via micro cogeneration. Castaneda et al. [22] introduced a sizing method for the techno-economic optimization of a hybrid system including photovoltaic panels, hydrogen, and battery systems. Their one-year simulations, based on hourly averaged data, revealed the operating performance of three control strategies and demonstrated reliable electricity supply for stand-alone applications, even when the technically optimal solution was not the most economical. In the paper by Lajnef et al. [23], the authors investigated a PV/FC generator coupled with a PEM electrolyzer for grid-connected power generation, with special attention to MATLAB/Simulink modeling of temperature dependence, concentration overpotential, and limiting current in the PEM electrolyzer model and the power conditioning system, including the DC/DC and DC/AC converters. Möller et al. [24] developed a Simulink model to analyze a household system fully powered by a PV system with hybrid storage (lithium-ion battery and hydrogen system). They found that including household heat significantly increases the required amount of decentralized stored hydrogen for energy-independent operation.

Efficient operation of integrated systems requires effective control of the devices to obtain optimized techno-economic solutions. The cited literature mostly used heuristic logic [25], which relies on empirical rules to provide approximate solutions quickly with low computational effort. Linear programming strategies represent a valuable alternative, allowing the optimization of a linear objective function defined by a set of integers or continuous variables subject to linear constraints [26]. Compared with the heuristic approach, linear programming techniques result in more accurate solutions at a greater computational cost.

The aim of this study is to design and optimally size a hydrogen-based renewable energy community (small-scale energy systems for domestic applications, with a mix of different renewable energy sources), developing an optimal control strategy to extend device lifetimes and minimize costs. The optimization was carried out using linear logic, and the results are compared with a heuristic control strategy. The system is modeled using Matlab/Simulink R2023-b [27]. The novelty of this work lies in the implementation of a linear optimization approach that accounts for the degradation of H2 devices (i.e., fuel cells and electrolyzer) and the battery pack based on their operating conditions. These technologies degrade along different pathways under variable or fixed-point operating conditions, leading to varying component lifespans [28]. While ageing processes significantly affect system performance and costs, they are rarely considered in the literature. Recent work on battery lifetime prediction, such as the SG–GRU approach in [29], shows how accurate monitoring of ageing and remaining useful life can significantly improve the control and reliability of energy storage systems. These studies reinforce the relevance of including degradation aspects in energy management strategies, which is one of the motivations of the present work. Unlike previous studies on hydrogen-based systems [21,22,23,24,25], this work integrates component degradation directly into the optimization objective of the EMS, allowing the system to select operating conditions that extend device lifetime and reduce replacement costs rather than assuming ideal efficiencies or fixed cycle counts. Table 1 highlights the main differences between the present study and previous works.

Table 1.

Comparison between this work and previous studies.

The paper is divided into three sections: firstly the numerical model describing the different components and their interaction is presented; in the second part, the conceptualization of the power demand, the input of the structural model, and the sizing of each component is discussed; in the last part, the results of the conducted simulation are shown and discussed, investigating whether the assessed system can match the demand of an energy community.

2. Model Description

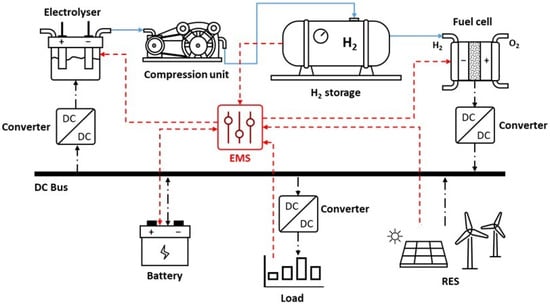

An overview of the HESS considered in the present work is provided in Figure 1. The hybrid system consists of a hydrogen integrated system (comprising an electrolyzer, a fuel cell, a volumetric compressor, and a gas storage tank), a battery pack, a renewable energy source (a photovoltaic system and/or a wind turbine—RES), and a load fed in DC. The hydrogen system (via the electrolyzer and the fuel cell) is connected to a DC bus through DC/DC converters. The battery pack, the load, and the RES are also connected to the DC bus. An Energy Management System (EMS) controls the entire system, according to the load request, the RES production, the state of charge of the batteries, and the hydrogen availability.

Figure 1.

Hybrid system layout (red dashed lines: signal exchange; blue lines: hydrogen line; black dot-dashed lines: electrical power).

The modeling of each system component is performed within the MATLAB/Simulink environment. In the case of the batteries and fuel cells, library models were used [30,31]. Conversely, the models of the electrolyzer, the volumetric compressor, and the gas storage tank, as well as the EMS, were developed ad hoc. As the primary focus of this study is on the EMS, the subsequent subsections will provide detailed information on its operation and optimization logic. Due to the large size of the technologies implemented, the behavior of each component has been checked against typical performance curves and degradation trends reported in the literature.

2.1. Energy Management System Framework

The primary function of a microgrid EMS is to supply power to the load as required, using a combination of generated power and storage resources, without wasting any energy. To achieve this, the EMS continuously communicates with the HESS components (Figure 1) to monitor and control their status and the load demand. The net power available to the HESS, (that is, the difference between the power generated by the RES and the load L), is used to determine the HESS behavior at each time instant. When , perfect balance is achieved between RES generation and load, leaving the HESS unchanged. When RES generation exceeds consumption (, the surplus power is stored in the HESS, putting the system in charge mode. Conversely, when ΔP < 0, a power deficit occurs, which must be supplied by the battery or the FC, putting the HESS in discharge mode. The HESS power balance at any time instant is given in Equation (1).

In Equation (1) and represent the power received and provided by the battery, respectively; is the power supplied by the fuel cell, is the power absorbed by the electrolyzer. Both charge and discharge modes of the HESS are subject to limitations due to the inherent characteristics of the devices. In the charge mode, for instance, the surplus energy can be stored in the battery and/or as hydrogen. In this case, the power supplied to the battery () is the minimum between the maximum recharge power allowed by the battery () and the available power (here assumed as C = 1), which is computed as the average energy available to recharge the battery () divided by the time interval (t). Similarly, the maximum power that can be supplied to the electrolyzer, , is the minimum between its rated maximum power, , and the available power computed as indicated earlier (, where is the average energy available for the electrolyzer). It is evident that in charge mode, the fuel cell is inactive, and the power provided by the battery () is zero. The limitations are reported in Equation (2) [32].

In discharge mode, described by Equation (3) [32], the HESS is again subject to limitations, now related to its power output. The battery power output () is defined as the minimum between its maximum discharge power () and the average energy it can provide () over a time interval. In discharge mode, the electrolyzer is inactive, but the fuel cell is operational. The power provided by the fuel cell () is the minimum between its maximum rated power () and the average available energy divided by the time interval.

In Equations (2) and (3), the available energy depends on the amount of energy already stored, represented by the state of charge of the battery pack and the hydrogen pressure level in the storage tank. These quantities are computed using the following relations [32]:

where Qbat is the capacity of the battery pack (in Coulombs), Vbat is the voltage (in V), is the total capacity of the hydrogen tank (in kg), is the hydrogen lower heating value (in kWh/kg), and and are the efficiency of the electrolyzer and the fuel cell, respectively.

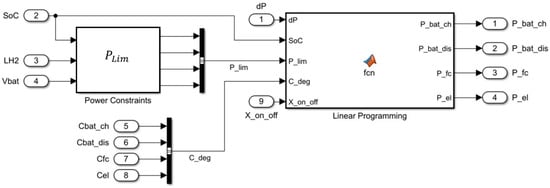

In Figure 2, the scheme of the EMS developed is reported, along with the inputs and outputs.

Figure 2.

Energy management system scheme.

Once the general behavior of the HESS is defined, the subsequent issue is the distribution of the net available power among all the system components. This is achieved through an optimization process in the EMS based on linear programming. The EMS aims to minimize the costs associated with the degradation of the involved devices and to extend the lifetime of the HESS. This is accomplished by defining an objective function f(t), which sums the costs related to power production/storage of each device according to their operating conditions and degradation status. The objective function is reported in Equation (5).

Each term on the right-hand side of Equation (5) consists of three factors: , , and (where the subscript i refers to the generic i-th device). represents the ratio of the device investment cost to the total plant cost and serves as a weighting factor to account for the size of the device and its replacement at the end of life. is a cost function related to the operating conditions of the device and its degradation status. is the power supplied from/to the devices at each timestep t. It is worth noting that for the battery pack the charge and discharge, costs are computed separately. The optimization problem is solved by using the “linprog” function from the MATLAB Optimization Toolbox.

The rationale behind Equation (5) is straightforward: to minimize the system cost, the EMS prioritizes the use of devices with the lowest replacement cost, thereby protecting those whose replacement would be more expensive. The definition of the cost function () for the battery, fuel cell, and electrolyzer are discussed in the following sections.

2.2. Cost Function () of the Devices

Degradation costs represent the economic losses caused by the degradation of the devices during their operation and are, therefore, associated with power production/storage within the microgrid. It is possible to assign a value to each device that is equal to its cost (CAPEX) [33]. It is assumed that, during operation, the device may degrade, reducing its initial value depending on operating conditions. When the residual value reaches zero, replacement becomes necessary. The financial loss resulting from the degradation of the i-th device over a specified time interval can be calculated by multiplying the capital expenditure (CAPEXi) by the partial degradation during that interval, as shown in Equation (6).

In Equation (6), is the degradation fraction at time step . Within this framework, the objective function in Equation (5) represents the value loss due to degradation in each time interval that should be minimized. In Equation (6), interest and inflation rates are neglected. This approximation is acceptable for short-term analysis or preliminary cost estimates [34].

The correlations used to calculate for the main components of the HESS (battery, electrolyzer, and fuel cell) are described in Section 2.3, Section 2.4 and Section 2.5. Other devices are also subject to degradation, but their impact on the overall system is less relevant, and their evaluation is here neglected.

2.3. Battery Degradation Function

This study considers a lithium-ion cell simulated using the battery model available in the Simulink library [35,36].

Battery degradation is modeled as a function of several operational parameters, with the Depth of Discharge (DoD) being the most influential. DoD is defined as the fraction of the total capacity discharged from the battery [37]. The battery SOC, a related quantity indicating the remaining capacity, is bounded by the upper and lower limits, thus defining the battery operating range. The model also accounts for charge (Crate,ch) and discharge (Crate,dis) rates, defined as the ratio between the maximum current absorbed or delivered, respectively, in one hour and the rated capacity (Crate = 1) [38]. Higher Crate values accelerate degradation due to increased heat generation and parasitic electrochemical reactions occurring when the actual current exceeds the nominal value. In smart community microgrids, the Crate is typically constrained below unity to mitigate these effects.

Operating temperature (Tbat) also affects degradation, with higher values accelerating aging. In the present system, Tbat cannot be directly controlled; therefore, current fluctuations are minimized to reduce temperature variations. The influence of weather conditions on Tbat is neglected.

Battery degradation is quantified through the variation in the state of health (SoH), defined as the ratio between actual and nominal capacity over a given time interval (Equation (7)).

Aging occurs as a gradual loss of capacity, and the battery is assumed to reach end-of-life when SoHend = 0.8, corresponding to 80% of the initial capacity (SoHstart = 1).

At each time step, the is updated by subtracting the hourly drop in SoH found through the aging function AGE(), from the state of health in the previous step , as reported in Equation (8).

In Equation (8), the term is a normalization factor representing the SoH variation over the useful lifetime of the battery. The aging function represents the fraction of total degradation occurring within the time interval , ranging from 0 at the beginning of life to 1 at the end.

Neglecting the normalization factor, Equations (7) and (8) can be rewritten as follows:

The ageing function consists of two contributions: calendar ageing , dependent on time, and cycle ageing , dependent on the battery operating conditions. These components are computed as follows [39]:

Total ageing is then:

depends on the absolute difference between the current state of charge SoC(tj) and the initial SoC(0) (assumed to be 0.5). depends on the charge and discharge powers, as well as the estimated number of cycles and the corresponding energy . These two quantities are functions of the DoD achieved during cycling and are typically evaluated using the characteristic Wöhler curve, which relates the number of cycles to DoD. As DoD increases, the number of cycles decreases sharply. According to [40], the Wöhler curve can be expressed empirically as:

where and [40]. This relation is valid for both the discharge and charge phases. For clarity, the depth of charge (DoC) is used during charging, while DoD is used during discharging. Thus, it writes:

The number of cycles and corresponding energy in charge and discharge modes are then obtained through Equations (16)–(19) as follows:

2.4. Fuel Cell Degradation Function

The evaluation of fuel cell degradation is based on the calculation of an hourly degradation factor (Drate), which quantifies the ohmic losses affecting the cell [34]:

where FU is the fuel utilization factor, T is the operating temperature, and is the current density inside the fuel cell. The increase in resistance relative to its initial value r0 leads to a corresponding voltage drop at the terminals, which can be written as a function of time as indicated by Equations (22) and (23).

Since the device is replaced when the operating voltage is 10% smaller than the rated voltage [41], the distributed degradation function can be computed as follows:

2.5. Electrolyzer Degradation Function

Electrolyzer degradation is evaluated using the concept of equivalent operating hours (heq) [42]. Assuming continuous operation at rated load (neglecting on/off cycles), heq coincides with the actual operating time. A linear voltage degradation model is adopted, expressed as:

where (lifeel) is the estimated useful life of the electrolyzer, assumed to be equal to 20,000 h [15]. This value is consistent with typical lifespans for electrolyzers used in light industrial applications [43].

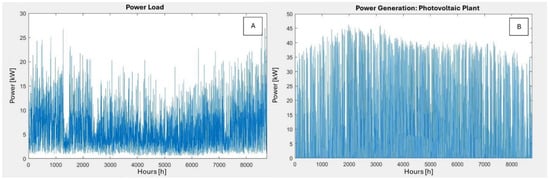

2.6. Net Power Evaluation

The hybrid system and the EMS was developed to study generic power curves as inputs, making the model adaptable to any type of energy source and load. The present paper considers an Italian case study of an energy community annual consumption, assuming a photovoltaic plant as the renewable energy source. The power curves for both the energy source and load are shown in Figure 3. The load includes the energy demand of 4 houses and 4 electric vehicle charging stations in a mountainous area of central Italy, near a small photovoltaic plant, with a total peak power of 42.60 kW. The thermal energy demand is met by heat pumps.

Figure 3.

Power demand of an energy community (A) and power generated from the photovoltaic system (B).

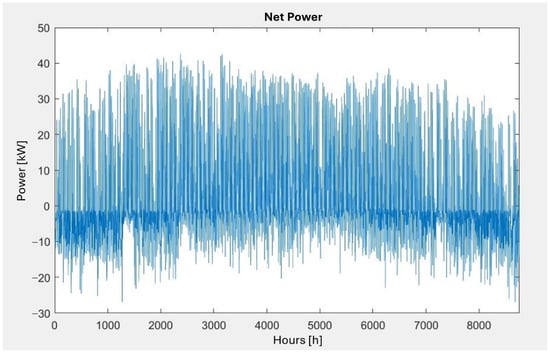

From these data, the net power, ΔP can be obtained by calculating the difference between the power generated by the RES and the load demand. Figure 4 shows the net power profile over one year. The net power data represents one of the main inputs to the EMS.

Figure 4.

Net power.

Positive values indicate energy surplus, while the negative ones refer to deficit. The corresponding values are summarized in Table 2. Two different seasonal trends are highlighted: a large surplus of electricity during the summer and part of the spring, and a deficit during winter and autumn, when solar energy production decreases while energy demand remains high. Thus, in the central part of the year, the surplus power is used for two primary functions: to refill the hydrogen tank (via the electrolyzer) and to charge the battery. Conversely, during winter and autumn, the electrolyzer is deactivated, and the battery pack together with the fuel cell operate to match the demand. The EMS is based on hourly resolution data, a choice that decreases the computational load but inevitably does not consider the short-term fluctuations that characterize real microgrids. Rapid variations in both load and irradiance can increase battery cycling and trigger more frequent transients in the fuel cell. Unfortunately, minute-by-minute data for load, renewable production, and the dynamic response of the electrochemical devices were not available for this study, limiting the temporal detail of the analysis.

Table 2.

Energy summary of the grid.

2.7. System Sizing

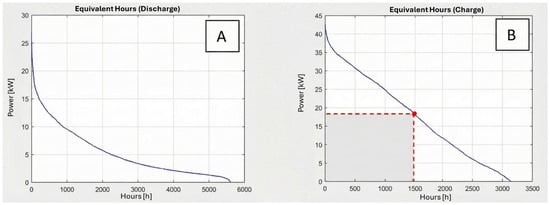

To meet the power demand, the design of both the fuel cells and the battery pack must be appropriately calibrated. In this study, commercial PEM fuel cells and batteries were employed and connected in parallel to deliver the required power. The control system was designed with the primary objective of maximizing hydrogen production, while the state of charge of the battery was considered of secondary importance. Consequently, the sizes of the electrolyzer and the fuel cell were selected with the aim of optimizing the hydrogen generation and exploiting the fuel cells as much as possible. For illustration, Figure 5 reports the frequency distribution of the hourly available (left) or required (right) ΔP for electrolyzer and FC, respectively.

Figure 5.

Power vs. equivalent hours for electrolyzer (A) and fuel cell (B).

The size of the electrolyzer is crucial to the sustainability of the system, as it regulates the hydrogen flow rate into the storage tank and therefore influences both the tank charging time and the battery SOC. The absorbed energy can be derived from the data plotted in Figure 5A by multiplying the nominal power of the electrolyzer by the equivalent operating hours. These hours correspond to the area of the rectangle subtended by a point on the duration curve (i.e., grey area in Figure 5B). The maximum rectangle area corresponds to the maximum hydrogen production achievable by the electrolyzer. Therefore, the subsequent step consists of identifying the equivalent hours of operation associated with the selected electrolyzer power. In this work, an 18 kW electrolyzer was selected, operating for 1547 h per year and producing 564 kg of green hydrogen (assuming an efficiency of 65% [44]). Following the same criteria, the nominal power of the fuel cell is defined by maximizing the rectangle area subtended by the duration curve in Figure 5B. This results in a fuel cell nominal power of 6 kW with an estimated hydrogen consumption of 574 kg over 1914 h/y of utilization, assuming a 58% efficiency. A comparison between annual hydrogen production and consumption shows that the former is slightly lower than that required by the fuel cell. However, it should be considered that the proposed system is not self-sustainable but has been designed to make optimal use of the single devices. In a real-world installation, this gap could be managed by occasionally supplementing hydrogen from external sources, limiting grid use during shortage periods, or oversizing the electrolyzer and PV system. The best approach depends on the desired level of reliability and the economic trade-off between extra equipment and the cost of hydrogen. In this work, the implementation of specific master-control constraints mitigates the risk of hydrogen depletion by activating the battery pack when the storage level falls below 10%, thereby reducing mechanical stress or tank failure. The initial hydrogen level was set to 0.6, and the tank volume was sized to exceed this level throughout the duration of the simulation. The simulation volume was determined to be 40 m3, corresponding to a capacity of about 660 kg at 200 bars, assuming a hydrogen density of 16.54 kg/m3. A compression stage is implemented for the storage. Mechanical compression usually consumes 2–10 kWh per kg of hydrogen, depending on the compression system [45]. This contribution is not explicitly modeled in the present work because it is out of the scope of the work. Mechanical compression typically requires 2–10 kWh per kilogram of hydrogen, depending on the compression technology used [45]. The ideal isentropic work was calculated following the equation in [46]; the calculation was carried out considering the maximum compression ratio implemented in the above-mentioned system (pressure of 8 bar from the electrolyzer to the storage pressure of 200 bar, i.e., β = 25), using k = 1.4, a standard reference value. The resulting ideal work was then adjusted using a typical isentropic efficiency of 0.7 and a motor efficiency of 0.9. The final specific energy requirement is 2.9 kWh/kg, which is fully consistent with values reported in the literature [46]. Based on the estimated annual hydrogen production of 564 kg/year, this corresponds to an annual electricity consumption of 1.63 MWh/year, i.e., approximately 3% of the photovoltaic surplus. It should also be noted that this value is strongly overestimated, as it assumes that all 564 kg/year are always compressed up to 200 bar; an unrealistic condition, given the actual pressure profile of the storage tank. For this reason, a detailed model of the compressor has not been directly implemented. However, the impact of the EMSs on its energy consumption has been estimated. The battery pack was sized to ensure an adequate coverage of the load demand. Furthermore, the sizing criterion adopted is that the related investment cost should be comparable with that of the other main technologies, not exceeding 50% of the total capital investment. A cost–benefit analysis is conducted for each device, considering both capital expenditure (CAPEX) and operational expenditure (OPEX). The specifications of a commercial lithium-ion battery with a nominal C-rate of 0.5 for both charge and discharge phases were assumed [47]. For the hydrogen systems, data for a PEMFC suitable for residential applications [48] and for an 18 kW alkaline electrolyzer were considered [49]. The projected lifespan of the plant was set to 20 years. The 20-year simulation assumes constant irradiance and load profiles, which represent a simplification. Long-term trends such as climate variability, shading evolution, and the increasing adoption of electric appliances and electric vehicles may substantially alter both generation and demand profiles. In addition, recent advances in the closed-loop regeneration of LFP batteries (e.g., [50]) highlight the need to evaluate end-of-life strategies and material recovery. Integrating recycling and circular-economy pathways into future models would enable a more comprehensive assessment of the environmental and economic impacts of hybrid PV–hydrogen–battery systems.

The cost of investment, Cinv (in EUR), is calculated using the following equation:

where Pnom (in kW) is the nominal power. Table 3 summarized the CAPEX, OPEX and cost of investiment of all the devices implemented in the model.

Table 3.

CAPEX, OPEX, and cost of investment of fuel cell, battery, and electrolyzer.

Table 4 summarizes the selected installed power and the parameters of the various devices that constitute the plant.

Table 4.

Summary of the size of devices.

In the next section, the dynamic behavior of the hybrid system is illustrated. The energy surplus is directed to the electrolyzer, allowing hydrogen to be produced and then stored in a pressurized tank. This stored hydrogen is subsequently used by a fuel cell when the energy demand exceeds the energy supplied by the renewable sources. The following simulations are carried out with the objective of minimizing grid interaction, thereby ensuring system independence.

3. Simulations and Results

Simulations were carried out considering the energy demand of the case study and the renewable power source generation during a whole year (8760 h). The electricity production period due to PV should provide enough power to match the seasonal demand in the summer where the solar irradiance is high, while the hydrogen technologies and the battery pack should compensate for the lack of energy when the energy produced from the photovoltaic cell is low. In the following subsections, the results of the simulation are presented. To emphasize the importance of an effective EMS and its impact on the lifetime of the devices, two different sets of comparisons were carried out:

- -

- Linear vs. heuristic EMS: the proposed linear programming EMS was compared with a widely used EMS approach, namely the rule-based Heuristic EMS [51].

- -

- Fixed vs. variable operating conditions: using the linear EMS, a comparison between a fixed and a variable operation mode is performed. In the fixed case, both fuel cell and electrolyzer can operate only in a fixed power range, namely for fuel cell, and for the electrolyzer. In the variable operation case, both the devices can operate from 0% to 100% of their rated power.

For each comparison, the power balance, the state of the HESS (SoC and LH2), the residual life of the devices, CO2, and the economic benefits of the EMS related to the degradation costs are reported. Finally, the proposed EMS was also compared with the available literature.

3.1. Linear vs. Heuristic EMS

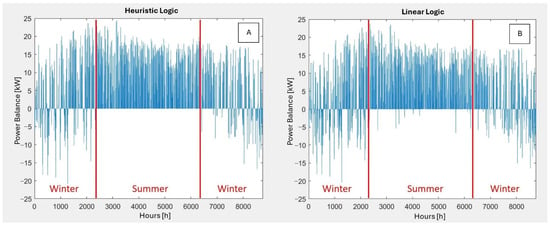

Figure 6 shows the grid power balance for the two implemented strategies, through the evaluation of electricity deficits and surpluses. The power balance was calculated using Equation (27):

where is the power generated by the use of stored energy, is the sum of all the powers related to the devices that absorb electricity (electrolyzer, load, and batteries during the charge phase), is the power from the fuel cell, is the power absorbed by the electrolyzer, is the amount of power absorbed by the battery pack in charging mode, and is the amount of power of the battery in discharging mode.

Figure 6.

Dynamic behavior of micro-grid with heuristic (A) and logic (B) control.

The surpluses are represented by the positive values in the balance curve, while the deficits are indicated by the negative values. The microgrid relies on the main grid for its electricity supply, as the microgrid cannot operate in stand-alone mode. This is due to the large load demand in some parts of the year, or to a large energy surplus that cannot be stored in storage systems. The overall grid balance is quite similar considering the two different strategies. The main difference is in the summer period, wherein the heuristic logic exhibits a complete absence of deficit, in contrast to the linear logic, which shows deficit situations, albeit to a limited extent. This is attributed to the high utilization of the battery during the discharge phase in the linear logic, which consequently results in lower average SoCs, leading to the increased surplus. A summary is presented in Table 5. The values confirm that the heuristic approach is more effective in terms of autonomy of the system.

Table 5.

Summary of energy surplus and deficit of the grid.

To highlight the global energy behavior, the hours of use of the fuel cell system, as well as the electrolyzer and battery performance, for the charge and discharge phases, are reported in Table 6 and Table 7, respectively.

Table 6.

Summary of the energy in charging phase for each device.

Table 7.

Summary of the energy in discharge phase for each device.

The difference in annual hydrogen production between the two ESMs is approximately 30 kg/year. This further confirms the impact of the EMS on the electrolyzer and, consequently, on the compressor. However, assuming the specific energy consumption for compression calculated in Section 2.7, this leads to a consumption of 0.087 MWh/year, so with a marginal variation in annual electricity use, the compressor has a very limited impact on the overall energy balance of the system.

During the year, the energy surplus is more efficiently exploited in the linear logic, as the energy stored in the battery, or as hydrogen, is higher. The use of energy-absorbing devices (i.e., electrolyzer and battery during the charging phase) exhibits an increase from the winter to the summer, while the working hours of the fuel cells and the battery discharge tend to decrease. Conversely, during the spring and summer months, when the cooling system operates at full capacity, the behavior is opposed. In this scenario, the fuel cell is more stressed in the heuristic logic, resulting in an energy level similar to that of the battery.

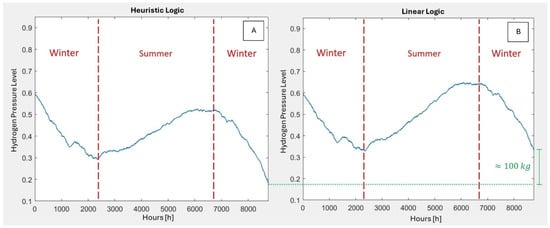

Figure 7 shows the average trend of the hydrogen storage for the heuristic logic (A) and the linear one (B).

Figure 7.

Hydrogen level for the heuristic (A) and linear (B) logic.

Both trends are similar, proving that the fuel cell continuously works during the autumn and the winter because of the lack of power generation from the photovoltaic cell while stopping into the summer period. The heuristic logic indicates that the minimum and maximum normalized levels of hydrogen are 0.18 and 0.60 (initial value), respectively, while the linear logic results in 0.33 and 0.6. It is evident that these values are associated with the diminished utilization of the fuel cell, a consequence of the battery capacity to match the demand. Using the heuristic model, it is evident that the annual requirement of hydrogen is higher than in the linear logic (100 kg higher).

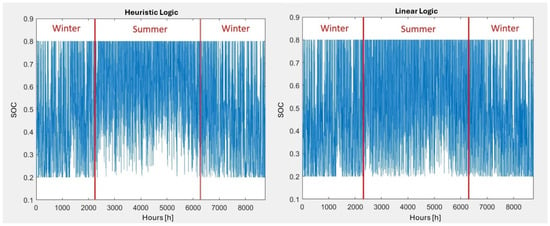

Figure 8 shows the annual behavior of the SOC related to the heuristic and linear logic.

Figure 8.

SOC for the heuristic (A) and linear (B) logic.

In both cases, the battery is less stressed during the summer period, due to the highest exploit of the energy produced from the renewable source. In the linear logic, the SOC is more fluctuant compared to the heuristic one, especially in the middle part of the year, because the battery utilization is favored during the discharge phase. However, the average value of the SOC is similar (0.51 in the linear logic vs. 0.53 of the first logic). Therefore, related to the battery system, no evident differences are noticed between the two logics. Since the system is designed to minimize the dependence on the grid, during extreme weather conditions, such as low solar irradiation or load peaks, grid support may be necessary. Possible strategies may include limiting the energy imported from the grid, peak-shaving policies, seasonal energy backup, and predictive analysis. All these strategies allow the microgrid to rely mainly on renewable energy.

3.2. Residual Life

Under different load profiles, each device experiences a specific degradation pattern. The residual life is defined as the remaining time before a device must be replaced. By evaluating the remaining life at the end of the simulation, it is possible to estimate the useful lifetime of each device based on the operating conditions it undergoes. It is important to mention that the residual life assessment also considers the on/off cycles of hydrogen systems. Specifically, for an on/off cycle within a step time (1 h), there is an overall degradation three times higher than occurring under fixed-point operation [52]. A similar assumption was adopted for the battery. Table 8 shows the computed residual life of the components after one year of operation.

Table 8.

Residual life of the battery, fuel cell, and electrolyzer.

For both control logics, a more pronounced degradation is observed in the fuel cell, while the electrolyzer exhibits similar behavior in both cases, and the battery, being the component least affected by aging, shows a slightly higher derating in the linear case. The lower degradation rate of the electrolyzer compared to the cell is mainly due its shorter operating time: 2693 h for the cell and 1547 h for the electrolyzer under the heuristic logic. Although the battery operates for more hours, it experiences less degradation due to its intrinsic characteristics, which provide a longer service life. The results are obtained considering that both the fuel cell and the electrolyzer run at a fixed point, a condition that best preserves the lifetime of these devices.

However, in typical stationary applications, fuel cells and electrolyzers run at variable operating point. For this reason, the lifetime under these two different operating conditions is also considered, taking into account the following constraints:

The battery control logic was unchanged. Table 9 shows the residual life values for the three components.

Table 9.

Residual life of battery, fuel cells, and electrolyzer with fixed and variable point conditions under linear and heuristic logic after a year.

As expected, dynamic operation leads to a significantly higher degradation of hydrogen systems (about 50%), thus making this operation mode less suitable. This outcome is well aligned with the literature and is mainly attributed to two important issues: degradation of the catalyst layer and poor control of the anode/cathode pressure [39]. On the other hand, the battery undergoes lower degradation under dynamic operation. This result may be controversial; however, it can be explained by the fact that, despite being subjected to continuous discharge cycles, the battery operates for a considerably shorter time than in the static case, thus resulting in a lower degradation rate [53]. Overall, in terms of degradation, the dynamic approach is a disadvantageous solution, leading to additional costs related to component replacement.

3.3. Economic Balance

In this section, the costs associated with one year of microgrid operation are analyzed. The most significant factor considered is the replacement cost, which represents the expenditure required to replace devices due to their degradation. This assessment accounts for both the purchase of new components and the removal or decommissioning of old ones. A device was assumed to require replacement when its residual life fell below 5%. Using the values calculated in Table 8 and assuming a useful life of the plant of 20 years, the number of replacements for all the main components and their associated costs were computed and reported in Table 10.

Table 10.

Number of replacements and replacement costs of battery, fuel cell, and electrolyzer in 20 years of operation, using the two logics.

The difference between the two control logics is not so clear and evident, with only a 6% cost saving observed under the linear logic. However, the outcome is more relevant when comparing systems operating at fixed point versus a variable point. The results are shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

Number of replacements and replacement costs of battery, fuel cell, and electrolyzer in 20 years of operation, using the two operating modes (heuristic logic).

Operating in the fixed-point regime can allow savings of 27% compared to the variable point case. This highlights that, although variable point operation provides greater system flexibility, it also leads to higher degradation and, consequently, increased economic expenditure.

3.4. CO2 Emissions

Focusing on emissions associated with power generation, referring to 2023 for the Italian electricity grid [54], an average value of 0.32 tCO2eq/MWh was considered in the calculation reported in Table 12.

Table 12.

Annual CO2 emissions as a function of EMS logic.

The total emissions associated with the renewable microgrid are approximately 30 times lower than those of a scenario where the same loads are supplied by the conventional grid. These results clearly demonstrate the benefits of implementing microgrids within smart energy communities.

3.5. Comparison with the Literature

The simulations indicate that the linear logic is the most effective approach for managing an electric grid with hydrogen technologies, both in terms of device degradation and CO2 emissions. For this reason, only the results obtained using the linear logic are compared with the existing literature. A hydrogen network [51] was taken as a reference, considering two different energy management strategies: EMS 1, where hydrogen systems are prioritized, and EMS 2, where priority is given to the battery. The results are summarized in Table 13 and Table 14 and compared with those obtained in this work.

Table 13.

Comparison between the literature results and the present study: energy flows.

Table 14.

Comparison between the literature results and the present study: device utilization.

The EMS 1 strategy has been shown to favor the use of hydrogen systems, with utilization rates of 32% and 18% for the fuel cell and electrolyzer, respectively (both operated at variable points). In contrast, EMS 2 implements an alternative logic, prioritizing battery usage; the results indicate that the battery was active for 67% of the time. In contrast, the linear EMS employed in this study does not reduce the power deficit compared to EMS 1, with a slightly higher deficit observed. However, it demonstrates superior capability in managing energy surplus, resulting in less wasted renewable energy than reported in the referenced work. Moreover, the fuel cells and batteries in EMS 1 and EMS 2 are subjected to greater stress, accelerating degradation. In contrast, the balanced use of electrochemical devices, as implemented in the linear EMS and discussed in the previous sections, can extend their operational lifespan.

The work of Zhang et al. [55], in which an electrolyzer was connected to a PV, shows the hydrogen level obtained in the tank.

In general, the trend shows lower hydrogen levels during the winter and higher levels in the summer. This pattern is mainly due to increased hydrogen production in the summer, which correlates with the greater energy surpluses generated by photovoltaics. A similar trend was also observed in the work used for the other discussion [51].

As done for the hydrogen level, SOC level was compared with the one observed in the work of Scamman et al. [55,56]. The results are similar to those observed for the hydrogen tank (Figure 7). During the summer, the battery remains fully charged and unused in the scenario where only the battery is present, with the SOC constant and equal to its upper limit. In contrast, when hydrogen systems are included, the SOC fluctuates near the maximum, reflecting continuous charging and discharging of the battery. In this context, a more obvious distinction of charge states is observed in the two seasons. This behavior agrees with that observed in this work and in the work of Ghirardi et al. [57].

4. Conclusions

A simulation model was developed to optimize the energy flow in a hybrid renewable power system integrated with hydrogen technologies. The main objective of the study was to evaluate the potential of a hydrogen-based power-to-power system as a storage solution, considering the degradation rate of the devices under different logics, heuristic and linear, and under two different operating conditions, variable and fixed point. The analysis was conducted using a case study located in central Italy, which provides representative climatic and load conditions for the model evaluation. The proposed model allows us to determine the contribution of each technology when a load-following strategy is adopted.

The main findings of the analysis can be summarized as follows:

- The linear logic has several advantages, including a lower total cost of ownership and higher green hydrogen production compared to the heuristic logic. However, the latter shows lower dependence on the main grid.

- Dynamic operation leads to greater deterioration, particularly in hydrogen systems where lifetime is further reduced by approximately 25% compared to static operation. This results in more frequent replacements to ensure process continuity, thus increasing overall operating costs.

- CO2 emissions from the renewable microgrid are roughly 30 times lower than in a scenario where the same loads are supplied by the conventional electric grid.

This study presents several limitations that open pathways for further development. First, in-house experimental validation was not included in the present work; however, it will be carried out in future activities to further strengthen the reliability and robustness of the proposed EMS. Moreover, the compression stage for hydrogen storage has not yet been modeled. Its inclusion in future versions of the framework is expected to slightly reduce the net hydrogen availability while increasing the system OPEX and will therefore provide a more accurate representation of real operating conditions. Future research will also explore scenario-based analyses, incorporating climate change projections and evolving load profiles over the system’s lifetime to assess the long-term resilience of the hybrid system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G.G., D.B. and P.V.; formal analysis, A.V.; investigation, A.V. and G.G.G.; data curation, A.V. and G.G.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.V. and G.G.G.; writing—review and editing, G.G.G., D.B. and P.V.; visualization, A.V.; supervision, D.B. and P.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are based on energetic outputs of a small town (private) and operational observation. Further details are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- International Energy Agency. CO2 Emissions in 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/co2-emissions-in-2023 (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Mišík, M. The EU needs to improve its external energy security. Energy Policy 2022, 165, 112930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agencyabriendomundo. Renewables 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2023 (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Lawrence, J.; Boltze, M. Auxiliary power unit based on a solid oxide fuel cell and fuelled with diesel. J. Power Sources 2006, 154, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palone, O.; Hoxha, A.; Gagliardi, G.G.; Di Gruttola, F.; Stendardo, S.; Borello, D. Synthesis of Methanol from a Chemical Looping Syngas for the Decarbonization of the Power Sector. J. Eng. Gas Turbine Power 2023, 145, 021018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla, A.; Sánchez, D.; García-Rodríguez, L. Assessment of power-to-power renewable energy storage based on the smart integration of hydrogen and micro gas turbine technologies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 17505–17525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, B.; Kamath, H.; Tarascon, J.-M. Electrical Energy Storage for the Grid: A Battery of Choices. Science 2011, 334, 928–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaz, S.; Manzoor, T.; Pandith, A.H. Hydrogen storage: Materials, methods and perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palone, O.; Barberi, G.; Di Gruttola, F.; Gagliardi, G.G.; Cedola, L.; Borello, D. Assessment of a multistep revamping methodology for cleaner steel production. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 381, 135146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, P.; Stolle, D.; Kullmann, F.; Linssen, J.; Stolten, D. A techno-economic analysis of future hydrogen reconversion technologies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 77, 1254–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, K.S.; Mishler, J.; Cho, S.C.; Adroher, X.C. A review of polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells: Technology, applications, and needs on fundamental research. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 981–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, G.G.; El-Kharouf, A.; Borello, D. Assessment of innovative graphene oxide composite membranes for the improvement of direct methanol fuel cells performance. Fuel 2023, 345, 128252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, G.G.; Palone, O.; Paris, E.; Borello, D. An efficient composite membrane to improve the performance of PEM reversible fuel cells. Fuel 2024, 357, 129993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, G.G.; Ibrahim, A.; Borello, D.; El-Kharouf, A. Composite Polymers Development and Application for Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Technologies—A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, M.; Fritz, D.L.; Mergel, J.; Stolten, D. A comprehensive review on PEM water electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 4901–4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. The Future of Hydrogen. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/the-future-of-hydrogen (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Maleki, A.; Pourfayaz, F. Optimal sizing of autonomous hybrid photovoltaic/wind/battery power system with LPSP technology by using evolutionary algorithms. Sol. Energy 2015, 115, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Placke, T.; Chau, K.T. Overview of batteries and battery management for electric vehicles. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 4058–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharel, S.; Shabani, B. Hydrogen as a Long-Term Large-Scale Energy Storage Solution to Support Renewables. Energies 2018, 11, 2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensmail, S.; Rekioua, D.; Azzi, H. Study of hybrid photovoltaic/fuel cell system for stand-alone applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 13820–13826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, C.; Devrim, Y. Design and simulation of the PV/PEM fuel cell based hybrid energy system using MATLAB/Simulink for greenhouse application. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 22092–22106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, M.; Cano, A.; Jurado, F.; Sánchez, H.; Fernández, L.M. Sizing optimization, dynamic modeling and energy management strategies of a stand-alone PV/hydrogen/battery-based hybrid system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 3830–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajnef, T.; Abid, S.; Ammous, A. Modeling, Control, and Simulation of a Solar Hydrogen/Fuel Cell Hybrid Energy System for Grid-Connected Applications. Adv. Power Electron. 2013, 2013, 352765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, M.C.; Krauter, S. Hybrid Energy System Model in Matlab/Simulink Based on Solar Energy, Lithium-Ion Battery and Hydrogen. Energies 2022, 15, 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahyaoui, I.; Ghraizi, R.; Tadeo, F. Operational cost optimization for renewable energy microgrids in Mediterranean climate. In Proceedings of the 2016 7th International Renewable Energy Congress (IREC), Hammamet, Tunisia, 22–24 March 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourbon, R.; Ngueveu, S.U.; Roboam, X.; Sareni, B.; Turpin, C.; Hernandez-Torres, D. Energy management optimization of a smart wind power plant comparing heuristic and linear programming methods. Math. Comput. Simul. 2019, 158, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, N.; Pattel, B.; Siddiqui, A. Digital Twin Development and cloud deployment for a DC Motor Control embedded system. In Digital Twin Development and Deployment on the Cloud; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 339–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agati, G.; Borello, D.; Migliarese Caputi, M.V.; Cedola, L.; Gagliardi, G.G.; Pozzessere, A.; Venturini, P. Effect of the Degree of Hybridization and Energy Management Strategy on the Performance of a Fuel Cell/Battery Vehicle in Real-World Driving Cycles. Energies 2024, 17, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Wu, X.; Liu, L.; Ye, J.; Wang, T.; Fu, L.; Wu, Y. Prediction of remaining useful life and state of health of lithium batteries based on time series feature and Savitzky-Golay filter combined with gated recurrent unit neural network. Energy 2023, 270, 126880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdin, Z.; Webb, C.J.; Gray, E.M. PEM fuel cell model and simulation in Matlab–Simulink based on physical parameters. Energy 2016, 116, 1131–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.W.; Aziz, J.A.; Kong, P.Y.; Idris, N.R.N. Modeling of lithium-ion battery using MATLAB/simulink. In Proceedings of the IECON 2013—39th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Vienna, Austria, 10–13 November 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 1729–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torreglosa, J.P.; García-Triviño, P.; Fernández-Ramirez, L.M.; Jurado, F. Control based on techno-economic optimization of renewable hybrid energy system for stand-alone applications. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2016, 51, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.; Brandt, J.; Tjarks, G.; Vanselow, A.; Hanke-Rauschenbach, R. Cost-optimized replacement strategies for water electrolysis systems affected by degradation. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 28, 101261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Zhang, R.; Xu, Y.; Ren, S. Robustly coordinated operation of an emission-free microgrid with hybrid hydrogen-battery energy storage. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 8, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, N.; Monem, M.A.; Firouz, Y.; Salminen, J.; Smekens, J.; Hegazy, O.; Gaulous, H.; Mulder, G.; Van den Bossche, P.; Coosemans, T.; et al. Lithium iron phosphate based battery—Assessment of the aging parameters and development of cycle life model. Appl. Energy 2014, 113, 1575–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, L.H.; Somasundaram, K.; Ye, Y.; Tay, A.A.O. Electro-thermal analysis of Lithium Iron Phosphate battery for electric vehicles. J. Power Sources 2014, 249, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Shin, Y.-J. Optimize the operating range for improving the cycle life of battery energy storage systems under uncertainty by managing the depth of discharge. J. Energy Storage 2023, 73, 109144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, F.; Ahmadi, P. Fundamentals of batteries. In Simulation of Battery Systems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Xiao, H.; Liu, R.; Zhang, L. Optimal battery capacity of grid-connected PV-battery systems considering battery degradation. Renew. Energy 2022, 181, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masaud, T.M.; El-Saadany, E.F. Correlating Optimal Size, Cycle Life Estimation, and Technology Selection of Batteries: A Two-Stage Approach for Microgrid Applications. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2020, 11, 1257–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruijn, F. The current status of fuel cell technology for mobile and stationary applications. Green Chem. 2005, 7, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, O.; Gambhir, A.; Staffell, I.; Hawkes, A.; Nelson, J.; Few, S. Future cost and performance of water electrolysis: An expert elicitation study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 30470–30492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsad, A.Z.; Hannan, M.A.; Al-Shetwi, A.Q.; Begum, R.A.; Hossain, M.J.; Ker, P.J.; Mahlia, T.I. Hydrogen electrolyser technologies and their modelling for sustainable energy production: A comprehensive review and suggestions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 27841–27871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronier, T.; Maréchal, W.; Geissler, C.; Gibout, S. Usage of GAMS-Based Digital Twins and Clustering to Improve Energetic Systems Control. Energies 2022, 16, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsubo, Y. Hydrogen compression and long-distance transportation: Emerging technologies and applications in the oil and gas industry—A technical review. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 25, 100836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.; Giovannini, C. Hydrogen Gas Compression for Efficient Storage: Balancing Energy and Increasing Density. Hydrogen 2024, 5, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Xing, Y.; Kwon, D.; Pecht, M. Accelerated degradation model for C-rate loading of lithium-ion batteries. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2019, 107, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigolotti, V.; Genovese, M.; Fragiacomo, P. Comprehensive Review on Fuel Cell Technology for Stationary Applications as Sustainable and Efficient Poly-Generation Energy Systems. Energies 2021, 14, 4963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, D.; Patel, M.K. Techno-economic implications of the electrolyser technology and size for power-to-gas systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 3748–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Yuan, L.; Liao, Y.; Shao, Y.; Hao, S.; Huang, Y. Efficient separation and selective Li recycling of spent LiFePO4 cathode. Energy Mater. 2023, 3, 300053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, J.; Segura, F.; Andújar, J.M.; Ferrario, A.M. The Economic Impact and Carbon Footprint Dependence of Energy Management Strategies in Hydrogen-Based Microgrids. Electronics 2023, 12, 3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.-L.; Lee, S.-M.; Yu, S. A Comprehensive Review of Degradation Prediction Methods for an Automotive Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell. Energies 2023, 16, 4772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, P.; Jossen, A. Impact of Dynamic Driving Loads and Regenerative Braking on the Aging of Lithium-Ion Batteries in Electric Vehicles. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, A3081–A3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale. Available online: www.isprambiente.gov.it (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Zhang, F.; Thanapalan, K.; Procter, A.; Carr, S.; Maddy, J.; Premier, G. Power management control for off-grid solar hydrogen production and utilisation system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 4334–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scamman, D.; Newborough, M.; Bustamante, H. Hybrid hydrogen-battery systems for renewable off-grid telecom power. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 13876–13887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghirardi, E.; Brumana, G.; Franchini, G.; Perdichizzi, A. H2 contribution to power grid stability in high renewable penetration scenarios. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 11956–11969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).