Abstract

Decarbonizing building energy use requires efficient heat pumps and low-impact geothermal exchangers. A novel standalone TRNSYS Type was developed for a patented shallow horizontal ground heat exchanger (HGHE), called flat-panel (FP), designed at the University of Ferrara. Beyond simulating the FP in isolation, the Type enables coupling with other components within heat-pump configurations, allowing performance assessments that reflect realistic operating conditions. The Type was implemented in TRNSYS models of a ground-source heat pump (GSHP) and of a dual air and ground source heat pump (DSHP) to verify Type reliability and evaluate potential DSHP advantages over GSHP in terms of efficiency and ground-loop downsizing. The performance of the system was analyzed under varying HGHE lengths and DSHP control strategies, which were based on onset temperature differential . The results highlighted that shorter HGHE lines yielded higher specific HGHE performance, while higher reduced HGHE operating time. Concurrently, the total energy extracted from the ground decreased with increasing and reduced length, thus supporting long-term thermal preservation and allowing HGHE to operate under more favorable conditions. Exploiting air as an alternative or supplemental source to the ground allows significant reduction of the HGHE length and the related installation costs, without compromising the system performance.

1. Introduction

Ground-source heat pump (GSHP) systems represent a well-established pathway to reduce building energy consumption and emissions by exploiting the near-constant temperature of the shallow subsurface as a low-grade heat source/sink [1]. Compared to air-source heat pumps, GSHPs typically deliver higher seasonal performance factors in heating-dominated climates and maintain efficiency under adverse ambient conditions. Nevertheless, installation costs and site constraints, like those associated with drilling deep boreholes or securing adequate trench space, significantly hinder the wider adoption of this technology [2,3]. With the aim to reduce capital costs and foster the applicability in urban contexts or in retrofit interventions where boreholes are impractical, shallow horizontal ground heat exchangers (HGHEs) are frequently adopted [4]. Significantly lower costs and simplified installation are achieved due to the shallow installation depth of HGHEs. Nevertheless, the reduced depth also results in the utilization of seasonal heat storage, so that the operational performance of HGHEs is strongly affected by local climatic boundary conditions. This negative aspect, together with the spatial footprint required by trenches and the thermal coupling achievable per unit trench length, can still be limiting in high-density contexts [5,6,7]. To address this issue, a novel type of HGHE, consisting of a flat-panel (FP) positioned horizontally and edgeways in a shallow trench, was developed at the University of Ferrara (UNIFE) in 2012 and then patented (UNIFE patent EP2418439A2) [8]. Conventional HGHEs have long relied on pipe-based geometries arranged in one or multiple layers. FP departs from pipe-centric designs by using planar, hollow panels oriented vertically within trenches typically 1–2.5 m deep. The panel aspect ratio and wall contact create more uniform soil-collector coupling compared to sparse pipe arrays and achieve the highest effective heat-transfer area per trench length. A detailed description of its configuration and high performance is reported in Refs. [9,10].

In parallel, analytical and numerical modeling tailored to planar trench collectors have been formulated to capture the three-dimensional conduction in the surrounding soil and the FP geometry, thereby enabling more accurate seasonal predictions for FP-HGHEs compared to adaptations of pipe-based models [11,12,13]. Literature includes comparative system-level studies in which FP-HGHEs are coupled to dual-source heat pumps (DSHPs) or hybrid HPs, suggesting that smart source switching between air and ground can reduce the required ground loop length while maintaining overall system efficiency.

DSHP systems allow heat extraction from the air or ground, depending on which source is more favorable. DSHPs can mitigate long-term thermal imbalance in the ground, protect soil temperatures from excessive drift, and reduce ground-loop length by shifting the load to the air during periods of mild ambient conditions. This shift can lower first costs while preserving, or even improving, seasonal performance relative to a pure GSHP in certain climates and load profiles [14,15,16]. Consequently, the performance of these systems strongly depends on the control strategy adopted. A large number of studies have compared fixed temperature thresholds, temperature-difference-based switching, and time-scheduled or optimized controls, often using simulation to balance instantaneous COP against ground sustainability targets [17,18].

TRNSYS is a widely used transient simulation environment for building energy systems which employs ready-to-use component models, called Types, to simulate system units [19]. For horizontal ground heat exchangers, Type 997 models multi-level horizontal pipe arrays using a finite-difference conduction network and multilayer soil representation [20]. Differently, for vertical borefields, Type 557 implements the Duct Ground Heat Storage (DST) model, a hybrid analytical-numerical formulation well-validated in GSHP literature [20]. These Types have underpinned thousands of design and research simulations, enabling whole-system studies that include compressors, hydronic loops, control logic, and building loads [21]. Nevertheless, no dedicated TRNSYS Type exists for FP-HGHEs, i.e., planar trench collectors with geometry-consistent heat-transfer modeling. Currently, the only way to simulate them is to either approximate the FP using pipe-array Types (risking geometry/physics mismatch) or rely on co-simulation with external CFD/FEA models, which complicates parametric studies and routine design. Addressing this gap is essential if FP-HGHEs are to be evaluated on equal footing with established pipe-based configurations in realistic duty cycles and with controller interactions. In passive-solar/dual-source layouts, a tiered tank temperature plus an indoor hysteresis scheme realizes a three-stage sequence (solar-direct → solar-assisted heat pump (SAHP)-water-source → air-source heat pump (ASHP)) [22]. Complementarily, GSHP–ASHP composite studies advocate GSHP as the base load with ASHP for peak-shaving under cold/mild periods, highlighting climate-responsive source allocation [23]. These insights motivate encapsulating the FP-HGHE together with a GSHP into a single TRNSYS component, so that a controller-assembled DSHP can plug in coupled to an ASHP branch under supervisory switching.

Against this background, a novel standalone TRNSYS Type was developed to simulate the patented HGHE developed at the University of Ferrara. Beyond simulating the FP in isolation, the key contribution of the Type is the ability to couple it with other units when integrated in a HP system. The aim was to move from detailed component-level modeling towards integration in plant systems, thereby allowing a more realistic assessment of its performance in actual applications and under real-world operating conditions. Type 206 was implemented into TRNSYS models of both a GSHP and of a dual air and ground source heat pump (DSHP), serving two purposes: (i) to verify the reliability of the modeling framework, and (ii) to examine whether DSHPs can outperform conventional ground-coupled systems by improving efficiency and allowing ground-loop downsizing.

2. Materials and Methods

The novel standalone TRNSYS Type 206 was developed to simulate the patented FP-HGHE designed at UNIFE [8], which is characterized by the following dimensions: 2 m (length) × 1 m (height) × 0.03 m (thickness). A detailed description of the FP and its high performance is reported in Refs. [9,10].

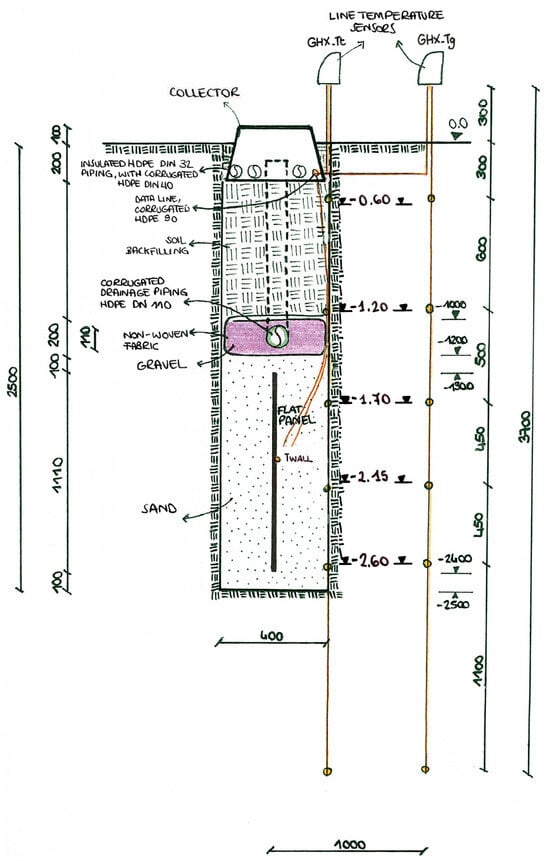

Figure 1 shows a geothermal line composed of 3 FP units before installation in the trench at the TekneHub laboratory at UNIFE, while a cross-sectional schematic of the FP-HGHE installation in the trench, reporting the main significant dimensions, is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

A geothermal line composed of 3 FPs before to be installed in the trench at the TekneHub laboratory of UNIFE.

Figure 2.

Cross-sectional schematic of the FP-HGHE installation in the trench [24].

The study was conducted in two stages: the development of the novel standalone TRNSYS Type 206 and its validation against the Matlab model (MATLAB R2014a) used for its development and experimental data; and the implementation of the novel Type to conduct a comparative analysis of the performance between a GSHP system and a DSHP system. The Type was modeled and tested in TRNSYS18.

2.1. Development of the Novel TRNSYS Type 206

Type 206 was developed in Fortran 2018 code (ISO/IEC 1539-1:2023) [25] based on the Matlab model described and validated in Ref. [26]. Here, the analytical model provides the accurate representations of heat transfer processes in the subsurface by predicting the dynamics of thermal fields induced by FP-HGHEs. The model accounted for atmospheric temperature fluctuations at the ground surface, an arbitrary geometry of FP-HGHEs operating in time-varying heating/cooling modes, and anisotropy and uncertain spatio-temporal variability of thermal conductivity of the ambient soil. Green’s functions were used to derive a general three-dimensional analytical solution of the problem with an arbitrary source (FP-HGHE shape) and its two-dimensional application to FP-HGHEs. The validation of the model through the comparison with experimental data demonstrated its ability to provide accurate fit-free predictions of soil-temperature fields generated by FP-HGHEs. Furthermore, the study results showed that a single FP-HGHE may affect soil temperature by several degrees at distances on the order of 1 m.

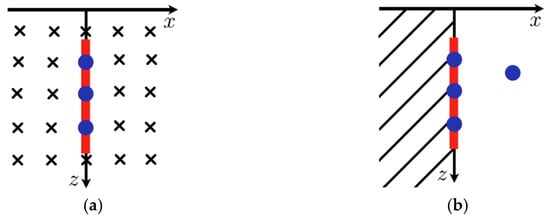

A scheme of the two-dimensional domain with an example of the node grid is illustrated in Figure 3a, where the x-axis corresponds to the horizontal direction (the ground surface), the z-axis represents the vertical direction pointing downwards, and the red line indicates the FP. The domain is discretized into a defined number of nodes where the temperature is computed. Some nodes (blue dots) correspond to the position of the FP, whilst others (black crosses) are located at specific positions within the ground.

Figure 3.

Two-dimensional domain of the Matlab model (a) and of the TRNSYS model (b) [27].

The model also considers the main thermo-physical properties of the ground, the position and geometrical features of the FP. Furthermore, the Matlab model takes into account the power demand of the system connected to the FP, which is expressed in W per·m2 of heat exchange surface and per time-step. The model also assumes an external surface temperature varying sinusoidally according to Equation (1):

where is the average temperature of soil in stable layer [°C], is the yearly amplitude of thermal oscillation at the ground surface [°C], is the annual external surface temperature frequency [1/day], is the time of the year [day], and is the coldest day of the year [day]. The model demonstrated a strong ability to predict the ground temperature distribution, as shown by its agreement with the experimental data reported in Ref. [26].

Within the development of the novel TRNSYS Type, the two-dimensional domain illustrated in Figure 3 was effectively simplified. In more detail, the domain was limited to a subset of nodes, preserving accuracy and significantly reducing simulation time. Indeed, the Matlab model was designed to resolve the temperature field across the entire ground domain, whereas the TRNSYS model aims at evaluating the outlet temperature of the water leaving the FP. Consequently, while the former required temperatures at all nodes, the latter can be formulated using only the temperatures of the nodes located on the FP. Besides these nodes, the domain of the TRNSYS model includes an additional, arbitrarily positioned node which can be selected as an output to evaluate the ground temperature at a specific position, as illustrated in Figure 3b.

Parameters, inputs, and outputs of Type 206 are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters, inputs, and outputs of Type 206.

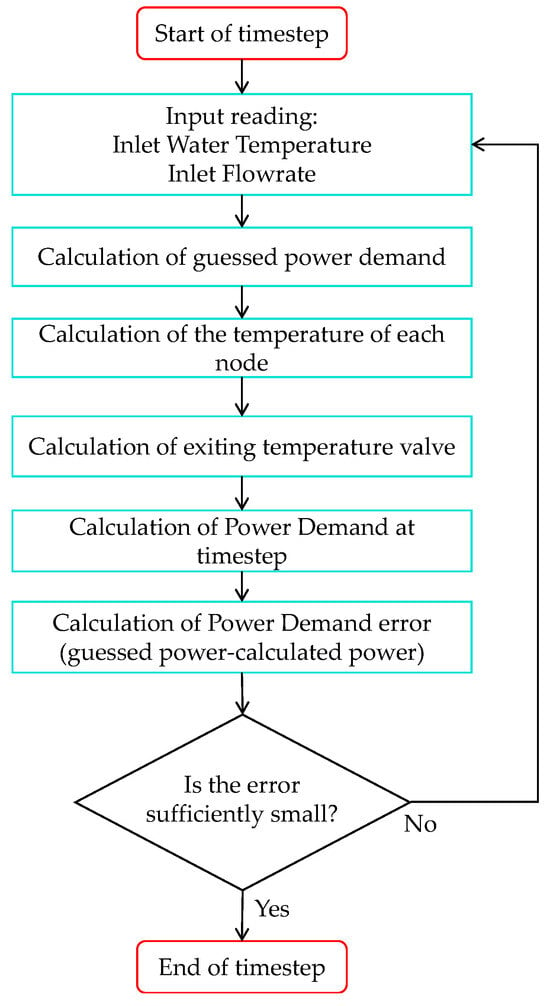

One of the key contributions of Type 206 is that it can simulate the patented FP and, more importantly, simulate it coupled with components similarly to when it is integrated in a realistic multisource HP system. For this reason, the inlet water temperature and flow rate are provided as inputs to the Type (Table 1). At each time step, the TRNSYS Type forms an initial guess of the heat demand following the logic reported in Figure 4. The guess is based on the difference between the outlet temperature from the previous time step and the current inlet temperature. The model then solves for all node temperatures and obtains an updated outlet temperature. Using the current inlet-outlet temperature difference, it computes a revised power demand and evaluates the error between this value and the initial guess. If the error is below a prescribed tolerance, the Type returns the node temperatures to the TRNSYS kernel and the simulation advances; otherwise, the procedure iterates until convergence is reached. The number of iterations per time step is reported among the outputs (output n.5 in Table 1), and it indicates how many iterations the Type requires to reach convergence. A cap of 100 iterations per time step is enforced. If this limit is exceeded, the Type ceases iterating, uses the last computed power to solve for the node temperatures, and issues a non-convergence warning to TRNSYS. If the number of warnings in a simulation exceeds the TRNSYS threshold, the simulation is stopped (this is standard TRNSYS behavior and is independent of the Type code). In addition, Type 206 implements further warning and error checks to prevent unreliable results: the simulation is stopped if node temperatures diverge or if parameter and input values are inconsistent.

Figure 4.

Simplified logic of Type 206 [27].

2.2. Comparative Analysis with TRNSYS HGHE Type 997

Existing TRNSYS HGHE Types include the standard TESS Type 997 and Type 999, which is essentially the multi-instance-compatible counterpart of Type 997. To evaluate the performance of Type 206, a comparative analysis was conducted with Type 997. The comparison was based on the equivalence demonstrated in [9], where it is shown that under specific conditions, a FP-HGHE installed in a 1 m trench has approximately the same behavior as a group of 8 straight pipes 1 m long installed in two parallel layers. The liquid flows in the same direction in each pipe, going from a supply collector to an exit collector.

By comparing Type 206 with Type 997, we can assess the performance of the novel FP-HGHE system against a well-established, benchmark model. This comparison also allows for a more realistic evaluation of the FP-HGHE’s potential in actual applications, considering both the physical and geometrical similarities between the two systems.

Geometrical properties of the two components used for the comparison are reported in Table 2, while the soil thermophysical properties and the external air properties are reported in Table 3. A node discretization of 0.2 m was adopted for Type 206, while 4 nodes per pipe were considered on the horizontal pipes of Type 997. The analysis was carried out over a 1-year period; a constant water flow rate was assumed, while inlet water temperature and the external surface temperature were considered to vary sinusoidally from 9 to 24 °C for the former, and from 5 to 27 °C for the latter.

Table 2.

Geometrical properties of the FP-HGHE and of the horizontal pipes considered in the comparative analysis.

Table 3.

Parameters considered in both the Type and the Matlab model.

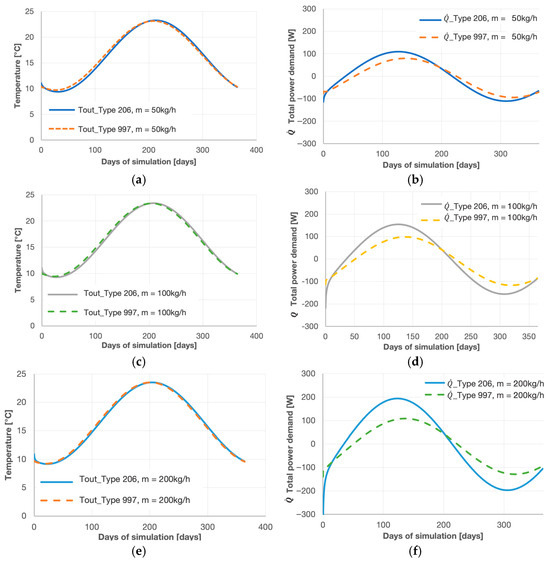

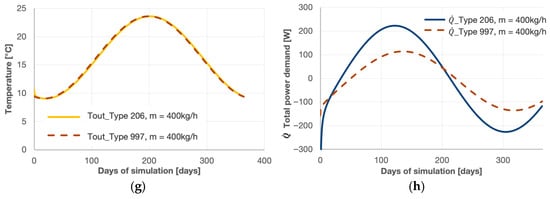

Two outputs were compared, the outlet water temperature and the total power demand, for four different values of water flow rate, i.e., 50 kg/h, 100 kg/h, 200 kg/h, and 400 kg/h. The results for outlet water temperature, illustrated in Figure 5a,c,e,g, show little to no variation over the year across all flow rates. Maximum temperature difference is equal to 0.6 °C. Conversely, since thermal power is proportional to the product of flow rate and temperature difference, discrepancies in thermal power increase with flow rate. Consequently, the minimal temperature offset can also translate into a significant power gap at high flow rates (Figure 5b,d,f,h).

Figure 5.

Outlet water temperature (a,c,e,g) and total power demand (b,d,f,h) from Type 206 and Type 997 with a flow rate of 50 kg/h (a,b), 100 kg/h (c,d), 200 kg/h (e,f), 400 kg/h (g,h).

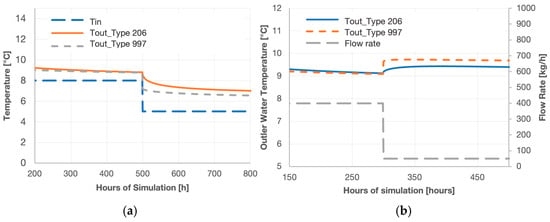

Type 206 and Type 997 were also compared under transient conditions involving step changes in inlet water temperature and flow rate, while all other inputs and parameters were held identical to those used in the previous analysis. The outlet water temperature was evaluated as the response variable. Results for two representative step transient tests reported in Figure 6 showed that, when varying either the inlet water temperature (Figure 6a) or the flow rate (Figure 6b), Type 206 presented a continuity in the value of the outlet liquid temperature, while the same parameter in Type 997 was characterized by a step in the value.

Figure 6.

Comparison between Type 206 and Type 997 during an inlet temperature step transient (a) and a flow rate transient (b).

2.3. Validation Against the Matlab Model

To validate the new Type, the results produced by Type 206 were compared with those of the Matlab model. The evaluation was conducted over the same period and case study as in [26], in which the Matlab model was validated by comparison of its predicted soil thermal field induced by a FP with experimental data. Measurements were collected at a field site of the Department of Architecture of the University of Ferrara (Italy). A detailed description of the FP design and operation is provided in Ref. [10].

The simulation period was from October 2nd (275) to April 30th (day 485). The parameters considered in both the Type and the Matlab model are reported in Table 3. Regarding the domain, a FP node discretization of 0.2 m was adopted in the Type, while a square domain grid of about 104 nodes spaced 0.1 m in both the x and z directions was employed in the Matlab model.

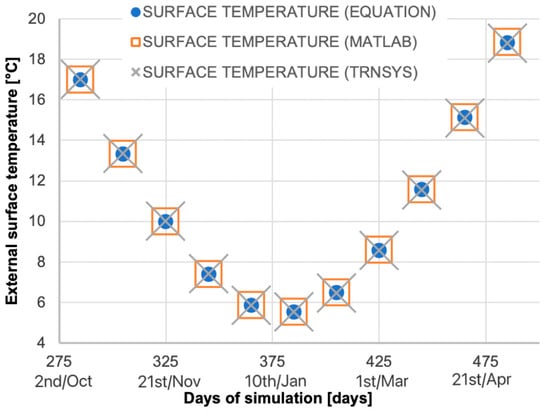

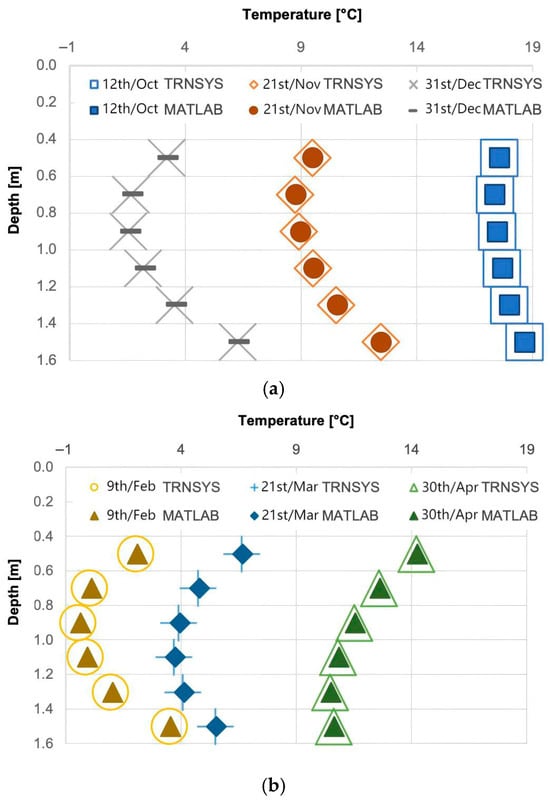

Figure 7 illustrates the values of the external surface temperature as evaluated through Equation (1) of the mathematical model [26], the first line of the Matlab temperature matrix (which represents the surface), and Type 206 by setting parameters 11 and 12 (the x and z coordinates for temperature evaluation) equal to 0. The results of node-temperature profiles as functions of depth and time, computed with the Matlab model and Type 206, are illustrated in Figure 8. For both the analyses, the results from the three models are in close agreement, with negligible differences between them.

Figure 7.

External surface temperature evaluated through the mathematical model, the Matlab model, and Type 206 [27].

Figure 8.

Node temperature evaluated through the Matlab model and Type 206 for the 12th October, 21st November, and 31st December (a), and for the 9th February, 21st March, and 30th April (b) [27].

2.4. Validation Against Experimental Data

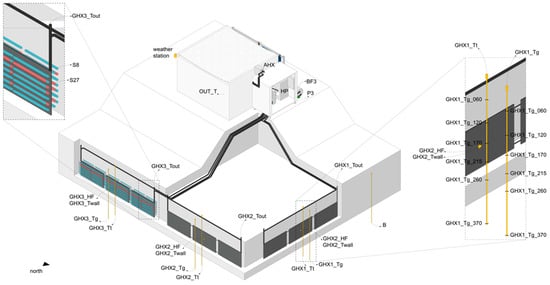

Type 206 was validated at the system level against the experimental data collected from the monitoring of the small-scale prototype of the IDEAS system, installed at the TekneHub laboratory of the University of Ferrara within the H2020 project IDEAS [28]. The prototype integrates a 6 kW water-to-water multi-source heat pump (MSHP) system devoted to the air-conditioning of a small mockup building (40 m3). On the source side, the MSHP is coupled with three main thermal sections exploiting the ground, sun, and air. The geothermal section operates with three 6 m-long geothermal loops, each one composed of 3 FPs (Figure 1 and Figure 9). Different backfilling materials were used for the three lines: sand (GHX1), a mixture of sand and paraffin-based granules (GHX2), and cylindrical high-density polyethylene (HDPE) containers filled with hydrated salts (GHX3). A cross-sectional schematic of the FP-HGHE installation in the trench backfilled with sand, reporting the main significant dimensions, is illustrated in Figure 2. Each geothermal line is equipped with a monitoring system including the following sensors, as reported in Figure 2 and Figure 9:

Figure 9.

Axonometric view of the IDEAS prototype, with focus on the three geothermal lines GHX1, GHX2, and GHX3, and the monitoring system [24].

- One Pt100 at the outlet of the line, to measure the outlet water temperature ;

- One Pt100 positioned at the center of the second FP, as temperature of the FP, ;

- Two digital multi-point probes installed in the ground at different distances from the FP line, one at about 0.20 m in correspondence of the trench wall, identified as , and the other one at nearly 1.00 m, identified as ;

- One flow meter measuring the water flow rate.

A detailed description of the IDEAS small-scale prototype is reported in Ref. [24].

For the comparison, a period of the heating season when only the geothermal line backfilled with sand (GHX1) was operational was considered. Then, the TRNSYS model was configured for case reproduction in terms of layout and operating conditions. The analysis focuses on three representative temperature outputs: the outlet fluid temperature of the geothermal line , the temperature measured at the center of the second FP , i.e., at a depth of 2.00 m, and the temperature measured at a depth of 1.70 m, 1.00 m away from the FP line, .

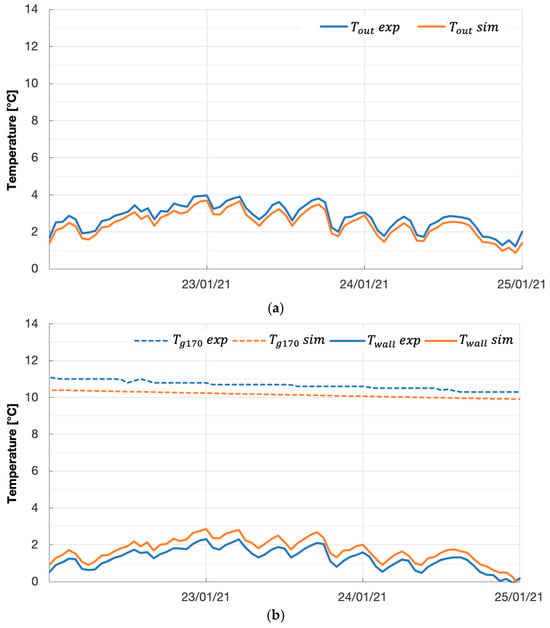

The comparative analysis highlighted a strong agreement between the simulation and experimental data across all the temperatures, with deviations consistently below 0.6 °C. Comparison between simulated results for outlet water temperature and experimental data are illustrated in Figure 10a, reporting an average difference of 0.33 °C. The small discrepancy confirms the reliability of Type 206 in reproducing the thermal performance of the FP-HGHE at the system level, which is critical for energy balance and control strategy assessments. The temperature measured at the center of the second FP, , and the one measured at a depth of 1.70 m, 1.00 m away from the FP line, , were compared with the corresponding simulation results (Figure 10b), with an average difference of 0.43 and 0.51, respectively. The slightly higher deviations observed for and may be due to local thermal disturbances related to the prototype, such as non-uniform backfilling conditions, soil heterogeneities, or sensor tolerances.

Figure 10.

(a) Experimental and simulated Tout, outlet water temperature; (b) experimental and simulated Twall, temperature at the center of the second FP, and Tg170, temperature at a depth of 1.70 m, 1.00 m away from the FP line.

2.5. Implementation of Type 206 in TRNSYS Models of a GSHP and of a DSHP System

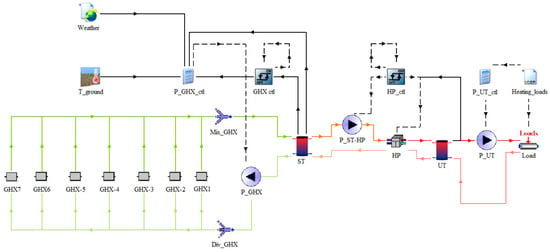

With the dual objectives of showing the reliability of the new Type at system level and investigating the higher efficiency of DSHP systems over GSHP systems, Type 206 was implemented in TRNSYS models of both a GSHP and a DSHP system.

Outdoor environmental conditions (like external air temperatures, solar radiation, etc.) continuously acquired by the weather station [29] installed outside the TekneHub laboratory of the University of Ferrara for the year 2024 were used to generate the weather data file used by Type 15, the weather data processor. The hourly heating load profile of a 100 m2 apartment in a 1980s building located in Ferrara and evaluated according to the outdoor air temperature profile of the year 2024 was used to inform Type 9a, the data reader for generic data files. The simulation period considered was the heating period defined for climate zone E, to which Ferrara belongs according to the national framework, i.e., from October 15th to April 15th. Peak load and total energy demand were equal to 7.9 kW and 11.5 MWh, respectively.

The GSHP system model (Figure 11) consisted of a water-to-water HP ( = 9 kW) simulated with Type 927, and of a user loop and a source loop. On the user side, Type 534 was used to simulate the 500 L user tank, which was equipped with 2 ports. One inlet/outlet port was connected with the HP, with a water mass flow rate of 640 kg/h, while a second port was connected with the user pump on the user side, with a load-modulated mass flow rate to provide space heating. Control of the HP operation was carried out via a differential controller with hysteresis (Type 2b), where setpoint temperature of the outlet water on the user side was set equal to 45 °C with an upper and lower dead band temperature of 5 °C and 0 °C, respectively. Accordingly, the HP was turned on whenever the user tank needed to be recharged to the seasonal target temperature. On the source side, the HP was connected with the 500 L source tank equipped with 2 ports as well (Type 534); one inlet/outlet port provided water to the HP through a pump, activated according to the HP. The second inlet/outlet port was connected to the geothermal field. The pump GHX positioned on the outlet port of the source tank provided inlet water to 6 lines of 7 FPs (Type 206) per line in parallel (with a total number of 42 FPs, equal to a total length of 84 m of geothermal line); outlet water was connected to the source tank on the top inlet port. Control of the pump GHX was carried out via a differential controller with hysteresis (Type 2b), where the setpoint of the average water temperature of the source tank () was set equal to 10 °C with an upper and lower dead band temperature of 2 °C and 2 °C, respectively. Therefore, the pump GHX was activated when the average temperature in the source tank fell below 8 °C and was turned off when temperature exceeded 12 °C. Furthermore, the control strategy was configured to charge the source tank under favorable ground conditions: the pump GHX was activated when ground temperature exceeded the average tank temperature by at least 1 °C, i.e., > ( + 1) (the same control rule was adopted with outdoor air temperature in the DSHP system). Both control rules are subject to the constraint that and the outlet temperature from the source tank are greater than −2 °C (i.e., −2 °C).

Figure 11.

TRNSYS model of the GSHP system.

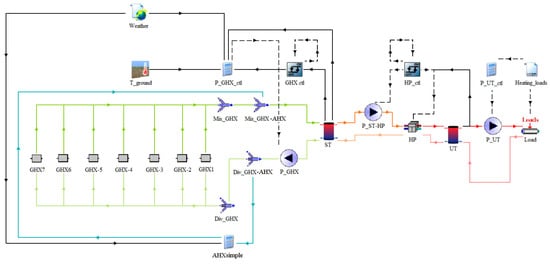

The TRNSYS model of the DSHP system (Figure 12) was composed of the same components as the GSHP one, integrated with the possibility to exploit the air source when more favorable conditions than the ground were available. The air heat exchanger (10 kW) was modeled in TRNSYS as a black box governed by a system of equations where the -NTU method for heat exchangers was solved for a fixed heat exchanger. The same modeling approach had been implemented and validated by UNIFE to calibrate the TRNSYS model of the IDEAS multisource HP system with experimental measurements within the H2020 project IDEAS [28]. A comprehensive description of the work carried out is reported in Ref. [24].

Figure 12.

TRNSYS model of the DSHP system.

With regards to the control strategy, the ground source was used when the outdoor air temperature was below 5 °C, < 5 °C, to avoid frosting conditions under cold and harsh climates, and when the ground temperature exceeded outdoor air temperature by an onset temperature differential , i.e., > ( + ). The operating condition for which > −2 °C had to always be satisfied to avoid the frosting of the working fluid within the FP. In all other conditions, the DSHP exploited the air source only. The control strategy also included a switching delay to prevent frequent transitions between the sources. A minimum time, equal to 20 min, was imposed, during which the system must remain in the current operating state before switching the energy source again. Furthermore, a ±1.0 K hysteresis was implemented around the air temperature setpoint (5 °C) and around the value considered to switch between the air and ground source. In addition, a non-centered hysteresis band of ±1.5 K around the ground temperature setpoint (−2 °C), i.e., ranging from −2.5 to −1 °C, was adopted to avoid the frosting of the working fluid when switching to the ground source. Regarding the response time of the actual controller, because this parameter is typically shorter than 1 min while the adopted simulation timestep was 10 min, it was not considered in the model, as its impact on the system’s long-term energy balance is negligible.

3. Simulations

Depending on the control logic, a DSHP draws heat from the ground, while a conventional outdoor air unit is engaged as an alternative sink/source for heat rejection or extraction. Consequently, the ground heat exchanger can be sized smaller than in a GSHP, leading to notable savings in installation costs. Within this framework, a comparative analysis has been carried out between a GSHP system and a DSHP system modeled in TRNSYS, under different operating conditions.

A HGHE field composed of 6 lines, each comprising 7 FPs in parallel (42 FPs in total), equal to a total length of 84 m of geothermal line, was adopted as the reference configuration. To explore leveraging DSHP benefits to shorten the HGHE line, four shorter total lengths were analyzed for the DSHP system, besides the reference case: 70 m, 56 m, 42 m and 28 m, corresponding to line length reduction of 17%, 33%, 50%, and 67%, respectively. The parameter , surface-to-length ratio, was defined to relate the required GHX length to the building floor surface, and thus to the heating demand. According to the configurations mentioned before, five values were considered, = 1.2 (reference), 1.4, 1.8, 2.4, and 3.6.

Furthermore, the effect of ground-source utilization intensity on overall system performance was also examined. The operating strategy adopted for the DSHP, which allowed the use of the ground when the ground temperature exceeded the outdoor air temperature by an onset temperature differential , was explored by considering six different values of : 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 °C. Higher values result in reducing the DSHP system runtime, yet largely preserve the ground resource, potentially improving its instantaneous advantage over to the air source when activated.

The study included a total of 31 cases analyzed: 1 reference configuration, represented by the GCHP, and 30 scenarios for the DSHP system.

4. Results and Discussion

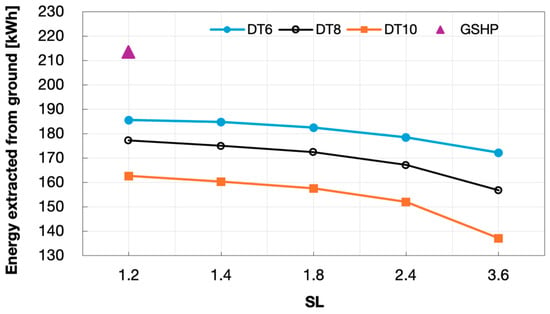

The total energy extracted from the ground by the different HGHE configurations (identified with the parameter ) in relation to the DSHP operating strategy (based on the value) is reported in Figure 13, whilst the specific energy extracted per m of HGHE line under the different is reported in Figure 14. The analysis of the results achieved for values lower than 6 highlighted that, for the same ratio, no differences were observed compared with those obtained at = 6. Therefore, only the results for > 6 have been reported.

Figure 13.

Total energy extracted from the ground in relation to SL and DT.

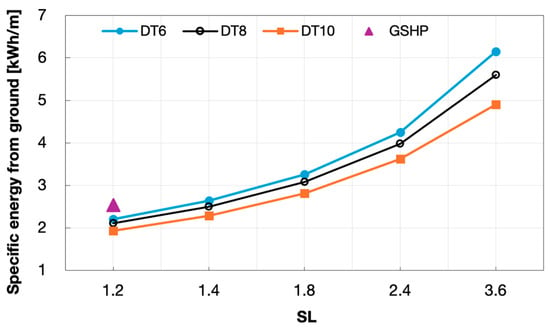

Figure 14.

Specific energy extracted from the ground in relation to SL and DT.

According to the defined control rule for the DSHP system, the ground is exploited when its temperature exceeds the outdoor air temperature by the onset differential (). However, outdoor air temperature is the fast-varying driver of source switching in winter, whereas ground temperature changes slowly. For this reason, the study focused on periods covering a broad outdoor air temperature range. Analysis of the weather data monitored during the year considered, i.e., 2024, highlighted the fourth week of January as the most representative of the winter period. Indeed, it simultaneously covered the operative winter temperature spectrum, ranging from the lowest values of outdoor air temperature reached during the winter in 2024, equal to −3 °C, up to the highest values of about 19 °C. In addition, the selected week in January presented the high heating-degree conditions that make performance differences under the various most visible. Finally, it yielded frequent transitions between air and ground, enabling a clearer comparison of the defined control strategies.

Analysis of the results of the total energy extracted from the ground highlighted that lower values were achieved by higher values of , i.e., by shorter HGHE lines, as is obvious. Furthermore, due to the reduced operating times defined by higher values of , the energy extracted by the same line decreased accordingly.

Differently, the specific energy significantly increased for higher ratios, as the length of the line was reduced considerably from the reference case, up to 67%. Additionally, for the same HGHE line, the energy variations associated with different operating times are initially small at low and become larger with increasing ; that is, with shorter HGHE line length. With regards to the reference case represented by the GSHP system, characterized by a ratio of 1.2 (HGHE line of 84 m), it allowed the extraction of about 15% more energy than the corresponding DSHP configuration with = 6. Nevertheless, the specific energy of the same reference case was drastically lower compared to the values achieved by shorter HGHE lines in the DHSP system. A line with ratio = 3.6 allowed the extraction of about 93%, 120%, and 142% more energy per m of HGHE line when adopting an operating strategy with = 10, 8, and 6, respectively.

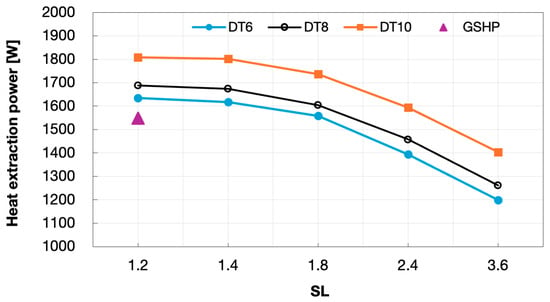

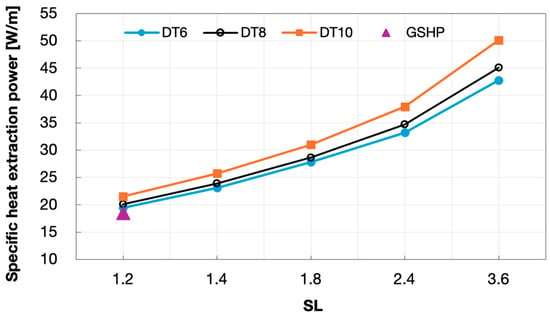

The values of heat extraction power and specific heat extraction power for the different HGHE configurations in relation to the DSHP operating strategies are reported in Figure 15 and in Figure 16, respectively. Similarly to the trend observed for the energy, the power extracted decreased according to the length of the HGHE line. Higher values of power for higher were observed when the same HGHE length was considered, due to the lower operating times. Conversely to the trend of the energy extracted, the power achieved by the reference case with the GSHP system was 5% lower than the corresponding case ( = 1.2 and = 6), always due to the higher operating time. Taking into account the specific heat extraction power, it increased for higher ratios and especially in relation to the highest values of . Once again, for the same HGHE line, energy differences due to changes in operating time were modest at low ratios and increase progressively as rises. Considering the specific heat extraction power of the GHSP reference case, a considerably higher increase than that observed for the specific energy was ensured by the case with ratio = 3.6. Indeed, the 28 m HGHE line in the DSHP system allowed extraction of a specific power approximately 232%, 245%, and 272% higher than the one achieved with the GSHP reference when adopting an operating strategy with = 6, 8, and 10, respectively.

Figure 15.

Heat extraction power from the ground in relation to SL and DT.

Figure 16.

Specific heat extraction power from the ground in relation to SL and DT.

Considering the influence of the parameters and on DSHP performance, it was observed that the total energy extracted from the ground decreases as increases. This enhances the long-term thermal preservation of the ground. In contrast, the heat-extraction power increases with , which is representative of the operating time of the HGHE line. Moreover, as the ratio increases, i.e., as the HGHE length required per·m2 of building area decreases, the average heat-extraction power rises markedly, as does the specific energy obtained from the ground. Consequently, the operating time of the GHX loop decreases as and/or increase.

5. Conclusions

A novel standalone TRNSYS Type has been developed to simulate a patented horizontal ground heat exchanger (HGHE), called Flat-Panel (FP), designed at the University of Ferrara. Besides the capacity of simulating the FP itself in isolation, the key contribution of Type 206 consisted of the possibility to couple it with other components when integrated in a HP system. The objective was to go beyond detailed component-level modeling towards its integration in plant systems, in order to enable a more realistic assessment of its performance in actual applications.

The Type was integrated in TRNSYS models of a ground source heat pump (GSHP) system and of a dual air and ground source heat pump (DSHP) system, (i) to verify the Type reliability, and (ii) to investigate the potential benefits of a DSHP over conventional GCHPs in terms of higher efficiency and size reduction. The performance of the system was analyzed under varying HGHE lengths and DSHP control strategies.

The simulation results demonstrated that shortening the HGHE line substantially increases the specific performance of the ground loop, while the DSHP control with higher onset temperature differential reduces the HGHE operating time. The total energy extracted from the ground decreases with increasing and with shorter lines, thus supporting the long-term thermal preservation of the ground source.

By leveraging air as an alternative or supplemental source when conditions are favorable, DSHPs enable significant reductions in HGHE length and associated installation costs, while maintaining system performance. Using the air heat exchanger as a complementary extraction/rejection unit also helps preserve the ground source and allows the HGHE to operate under more favorable conditions.

Limitations of the present study include the assumptions regarding the external surface temperature, which is considered to vary sinusoidally, and the actual surface thermal boundary conditions such as rainfall, snow cover, and vegetation coverage, which are not taken into account in the model. For this reason, future work will explore the impact of these factors to refine the simulation results and improve the model accuracy.

Moreover, future developments of the study will include a comprehensive analysis carried out throughout multiple years, to consider the thermal performance both during the heating and cooling season, with the aim to evaluate the long-term sustainability of the system and the effectiveness of the adopted control strategies. Among the aspects considered in this study, which are aimed at preventing potential ground thermal depletion or soil thermal imbalances, particular emphasis was placed on the proper sizing of the geothermal source, to avoid undersizing the ground loop and imposing high thermal loads per meter that may cause pronounced local cooling and long-term performance degradation. Equal importance was given to an appropriate spatial distribution of the FP-HGHEs lines, achieved by adopting sufficient spacing between trenches to limit thermal interference (3 m were also maintained in small-scale and large-scale prototypes of the IDEAS system installed in Ferrara). On the building side, a thermal storage tank was adopted to smooth short-term load fluctuations and enhance overall system performance. Finally, the primary objective of the work was limiting the operating hours of the geothermal loop so that the ground was used only when it was genuinely advantageous, with priority given to more disposable sources, such as ambient air, whenever outdoor conditions were favorable.

In addition, future work over multiple years will consider the implementation of geothermal free cooling during summer, thus contributing to the seasonal thermal rebalancing of the ground and mitigating long-term temperature drift; the integration of an additional heat source, such as solar energy; or, alternatively, the exploitation of other available waste-heat sources for ground regeneration. In more detail, the integration of the DSHP system with solar energy and the successful thermal recharge of the ground through PV/T panels during the cooling period was one of the performance results of the small-scale and large-scale prototypes of the IDEAS system installed in Ferrara within the H2020 project IDEAS, as reported in Ref. [24].

Against this background, the study will extend the validation of the TRNSYS Type at system level. The verification will be based on data collected from the multi-year monitoring of the large-scale prototype of the IDEAS system installed in Ferrara. The prototype includes a multi-source HP (MSHP) that exploits the ground, sun and air. The geothermal loop consists of 7 lines comprising a total of 41 FP-HGHEs, with a total ground loop length of 82 m. The prototype has been in continuous operation and monitoring since the beginning of 2022, and its performance dataset includes seasonal heating and cooling cycles. The system-level experimental verification plan will include the steps reported below.

- TRNSYS model configuration for case reproduction: the TRNSYS system-level model will be configured to replicate the actual geometry, boundary conditions, and operational parameters of the IDEAS prototype (number of FPs and their arrangement in lines, control logic, weather conditions for each season, etc.).

- Validation metrics and comparison: the model outputs will be compared to experimental data in terms of outlet temperature of the ground loop and of the MSHP; ground and storage tank temperature evolution; switching behavior and timing between the energy sources; seasonal heat extraction and system COP; and thermal drift in ground temperature across seasons.

- Uncertainty and sensitivity analysis.

- Long-term performance assessment: assessment of the model’s ability to predict long-term thermal behavior and sustainability of the ground loop by analyzing several heating and cooling seasons.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and S.C.; methodology, S.C.; simulation, S.C. and Y.S.; data curation, S.C. and Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.; writing—review and editing, S.C.; visualization, S.C.; supervision, M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because they were generated using TRNSYS simulation models and contain configuration files that are specific to the research project.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASHP | air-source heat pump |

| DSHP | dual-source heat pump |

| GSHP | ground-source heat pump |

| FP | flat-panel |

| HDPE | high-density polyethylene |

| HGHE | horizontal ground heat exchanger |

| HP | heat pump |

| MSHP | multi-source heat pump |

| SAHP | solar-assisted heat pump |

References

- Mahmoud, M.; Ramadan, M.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Ghani Olabi, A. Ground Source Heat Pumps. In Renewable Energy-Wave, Geothermal, and Bioenergy; Abdul, G.O., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; Volume 2, pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, P.; Jathunge, C.B.; Darbandi, A.; Fry, N.; Shor, R.; Mohamad, A.; Wemhöner, C.; Mwesigye, A. Development, modeling, and optimization of ground source heat pump systems for cold climates: A comprehensive review. Energy Build. 2024, 320, 114646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internation Energy Agency, The Future of Heat Pumps, Chapter 1, pp. 17–43. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/the-future-of-heat-pumps (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Hou, G.; Taherian, H.; Song, Y.; Jiang, W.; Chen, D. A systematic review on optimal analysis of horizontal heat exchangers in ground source heat pump systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 154, 111830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bina, S.M.; Fujii, H.; Tsuya, S.; Kosukegawa, H.; Naganawa, S.; Harada, R. Evaluation of utilizing horizontal directional drilling technology for ground source heat pumps. Geothermics 2020, 85, 101769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najib, A.; Zarrella, A.; Narayanan, V.; Bourne, R.; Harrington, C. Techno-economic parametric analysis of large diameter shallow ground heat exchanger in California climates. Energy Build. 2020, 228, 110444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simms, R.B.; Haslam, S.R.; Craig, J.R. Impact of soil heterogeneity on the functioning of horizontal ground heat exchangers. Geothermics 2014, 50, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Publication Server, EP2418439. Available online: https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/043708728/publication/EP2418439A2?q=pn%3DEP2418439A2 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Bortoloni, M.; Bottarelli, M. On the sizing of a flat-panel ground heat exchanger. Int. J. Energy Environ. Eng. 2015, 6, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottarelli, M. A preliminary testing of a flat panel ground heat exchanger. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2013, 8, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M.; Amadeh, A.; Hakkaki-Fard, A. A numerical study on utilizing horizontal flat-panel ground heat exchangers in ground-coupled heat pumps. Renew. Energy 2020, 147, 996–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Ven, A.; Bayer, P.; Koenigsdorff, R. Analytical solution for the simulation of ground thermal conditions around planar trench collectors. Geothermics 2024, 124, 103123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani, M.H.; Hakkaki-Fard, A. A hybrid analytical-numerical model for predicting the performance of the Horizontal Ground Heat Exchangers. Geothermics 2022, 101, 102369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanowski, M.; Cazorla-Marín, A.; Montagud-Montalvá, C. Energy Analysis and Cost-Effective Design Solutions for a Dual-Source Heat Pump System in Representative Climates in Europe. Energies 2022, 15, 8460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.S.; Park, J.W.; Kim, S.H. Measurement and Verification of Integrated Ground Source Heat Pumps on a Shared Ground Loop. Energies 2020, 13, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widiatmojo, A.; Chokchai, S.; Takashima, I.; Uchida, Y.; Yasukawa, K.; Chotpantarat, S.; Charusiri, P. Ground-Source Heat Pumps with Horizontal Heat Exchangers for Space Cooling in the Hot Tropical Climate of Thailand. Energies 2019, 12, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Gates, S. Comparative study of control strategies for hybrid GSHP system in the cooling-dominated climate. Energy Build. 2015, 89, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Fadejev, J.; Kurnitski, J. Modeling an alternate operational ground source heat pump for combined space heating and domestic hot water power sizing. Energies 2019, 12, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.A.; Beckman, W.A.; Mitchell, J.W.; Duffie, J.A.; Duffie, N.A.; Freeman, T.L.; Mitchell, J.C.; Braun, J.E.; Evans, B.L.; Kummer, J.P. TRNSYS, Version 18; Solar Energy Laboratory, University of Wisconsin-Madison: Madison, WI, USA, 2018.

- TESS. General Descriptions—TESS Libraries (TRNSYS 18): Type 997 Horizontal Ground Heat Exchanger. Available online: https://www.trnsys.com/tess-libraries/GeneralDescriptions_TESSLibs18.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- De Rosa, M.; Ruiz-Calvo, F.; Corberán, J.M.; Montagud, C.; Tagliafico, L.A. A novel TRNSYS type for short-term borehole heat exchanger simulation: B2G model. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 100, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, P.; Li, J.; Lei, T.; Li, R.; Novakovic, V. Application of heat pump assisted solar evacuated tube water heater operated within passive solar house in severe cold region. Renew. Energy 2024, 237, 121629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xia, X. Air source assisted ground source composite heat pump system: Life cycle carbon emissions and simulation analysis. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2023, 45, 12441–12452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CORDIS-EU Research Results. Novel building Integration Designs for Increased Efficiencies in Advanced Climatically Tunable Renewable Energy Systems. Deliverables; Documents, Reports; Experimental Results of the Prototype (Winter) & (Summer). Deliverable 3.5. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/815271/results (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- ISO/IEC 1539-1:2023; Programming Languages—Fortran—Part 1: Base Language. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Ciriello, V.; Bottarelli, M.; Di Federico, V.; Tartakovsky, D. Temperature fields induced by geothermal devices. Energy 2015, 93, 1896–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CORDIS-EU Research Results. Novel Building Integration Designs for Increased Efficiencies in Advanced Climatically Tunable Renewable Energy Systems. Deliverables; Other; ITES-MES Numerical Model. Deliverable 3.3. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/815271/results (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- CORDIS-EU Research Results. Novel Building Integration Designs for Increased Efficiencies in Advanced Climatically Tunable Renewable Energy Systems. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/815271/results (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Weather Station Vantage Pro2. Available online: https://www.davisinstruments.com/vantage-pro2/ (accessed on 8 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).