Abstract

The advent of digital transformation, social learning, and the increasing use of artificial intelligence is driving requisite changes in the development of data centres, which are buildings designed to process and store data. Green innovation is an integral component of the sustainable development of data centre units. Solutions utilising green and blue infrastructure in data centres are being currently introduced with the objective of optimising energy consumption and reducing energy demand. The primary aim of the research is to analyse the utilisation of biomass production and blue–green infrastructure in data centres. The article provides a consolidated set of key performance indicators (KPIs): energy efficiency, water use, waste heat utilisation, renewable energy integration, hourly carbon-free matching, embodied carbon, and land use impacts, that can be used to compare different data centre designs. Traditional PUE-centric evaluations are broadened by added metrics such as biodiversity/green area, intensity, and 24/7 CFE, reflecting the broader, multi-dimensional sustainability challenges highlighted in the current literature. Twelve international case studies described in the literature were compared and the feasibility of the Polish pilot project in Michalowo was assessed to illustrate specific cases related to energy-saving solutions and the use of renewable energy sources in data centres.

1. Introduction

Data centres for data storage and processing are linked to the increasing demand for data storage in the process of digitalisation, the development of the use of artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), big data analytics, and widespread access to cloud computing. This will lead to a significant increase in demand for electricity. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) report, there are more than 8000 data centres worldwide, of which around 33% are located in the US, 16% in Europe, and almost 10% in China. In Europe, there are around 1240 data centres, mainly concentrated in cities such as Frankfurt, London, Amsterdam, Paris, and Dublin. The data centre services sector is growing. In the European Union alone, data centre electricity consumption is estimated to be just under 100 TWh in 2022, representing almost 4% of the EU’s total electricity demand. Data centre electricity consumption in the European Union is estimated to reach almost 150 TWh by 2026. Data centres account for 1 to 1.5 percent of global electricity consumption. Electricity demand in data centres is mainly driven by two processes: data processing and cooling, together accounting for about 80 percent of data centre electricity consumption [1].

In response to the projected increase in electricity demand resulting from the growth of the data centre sector and the energy transition process led by the European Union, measures have been implemented to monitor data centre energy efficiency (in terms of data centre performance over the last full calendar year according to key performance indicators relating to energy consumption, power use, temperature set points, waste heat use, water consumption, and renewable energy use, among others) [2].

Heightened concerns about climate change have simultaneously led to major political decisions and regulatory frameworks across the EU. The European Green Deal sets out a roadmap toward a climate-neutral economy by 2050 [3], supported by intermediate targets such as the Fit for 55 package, which mandates a 55% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 compared to 1990 levels [4]. A key step in this process occurred on 12 March 2024, when the European Parliament adopted the revised Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD). Finalised after negotiations that began with the European Commission’s 2021 proposal and culminating in a political agreement in December 2023, the updated EPBD reinforces the building sector’s role in achieving EU climate objectives. It introduces mandatory life cycle carbon footprint assessment and disclosure in line with the EN 15978 [5] and Level(s) [6] frameworks. This fact, with rising commodity prices, means that maintaining data centre-related infrastructure will require investment in renewable energy sources, which, despite the high initial investment cost, will prove to be more cost-effective in the long term. The green data centre market is estimated to reach US$73.87 billion by 2024. There are national and international players in the market, such as IBM Corporation, Cisco Technology Inc, Dell EMC Inc, and Fujitsu. North America has the largest share of the green data centre market, and data centres account for approximately 2% of total electricity consumption in the US [7,8,9].

Therefore, improving the energy efficiency of data centres using renewable energy sources, including biomass production and blue–green infrastructure, is particularly important (especially considering the climate crisis) [9,10,11]. Based on hazard identification, a cause-and-effect relationship between CO2 emissions and energy production was identified in studies using data from the G7 [12]. This justifies research into the development and implementation of sustainable data centre design, and the implementation principles, of so-called Green Data Centres. An analysis of the state of research and the literature shows that the concept of the Green Data Centre is mainly associated with issues of energy efficiency, renewable energy sources, and the optimisation of cooling systems [13,14,15]. However, other design and implementation elements that shape a sustainable Green Data Centre environment using green and blue infrastructure also deserve attention [16,17,18].

The rapid expansion of digital infrastructure has turned data centres into one of the most energy-intensive components of the modern economy. One of the most important metrics for a data centre is power usage efficiency (PUE). PUE is a metric representing the ratio of power used for computing, to the power used for cooling and other appliances. Moreover, unlike most industrial facilities, data centres convert nearly all consumed electricity into heat, making them an exceptional and continuous source of low-grade thermal energy [19]. These characteristics position waste heat recovery (WHR) as a unique sustainability opportunity exclusive to the data centre typology.

Data centres produce a stable, predictable, and easily accessible stream of heat due to constant IT equipment operation and controlled environmental conditions. The uniformity of this thermal output allows for highly efficient integration with heat exchange and recovery systems [20].

In addition to energy efficiency, the optimisation of the carbon footprint throughout the life cycle of a data centre is becoming a critical dimension of sustainability assessment. The Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) approach allows the quantification of both embodied and operational emissions, according to EN 15978 [5].

Green infrastructure refers to natural and semi-natural areas, defining biologically active volumes and surfaces with biomass, vegetation, and organisms living in the city. It has technical infrastructure, and its task is to provide ecosystem, economic, and social services. Vegetation in the city has different functions, uses, and impacts and is realised on the ground, in the soil, and in substrates in open areas, and outside and inside buildings. The urban greening system is linked to the water management system [21,22,23].

Blue infrastructure refers to land use elements and technical facilities that enable the collection, storage, and treatment of rainwater and snowmelt, and the infiltration of water into the ground.

Recent reviews of sustainable data centre performance have focused primarily on energy-efficiency metrics such as PUE, advanced cooling, and server-side optimisation [14,24]. At the same time, a growing body of research highlights the role of life cycle carbon assessment and whole-building environmental performance based on EN 15978 and other LCA frameworks [18].

Increasing attention is also being paid to water stewardship—including WUE, greywater reuse, thermal storage, and site-scale hydrological retention—yet these elements remain substantially underrepresented in technology-centric reviews. Recent studies on green cooling and hybrid HVAC systems [17] emphasise water’s pivotal role in decarbonised operations.

Another rapidly emerging research area concerns 24/7 carbon-free energy (CFE) and demand-side flexibility. Workload shifting, carbon-aware scheduling, and multi-element flexibility models have been shown to reduce operational emissions beyond traditional renewable procurement strategies [16,25]. These approaches extend the scope of sustainability assessment from infrastructure design to real-time operational optimisation.

However, contemporary reviews rarely address land use-based strategies—particularly blue–green infrastructure, ecosystem services, biomass production, and biogas co-location—which significantly influence local energy balances, resilience, and water management. Although some studies mention biogas–data centre integration [26], a systematic synthesis of these spatial planning aspects is missing.

To support comparability across heterogeneous data centre projects, we introduce a consolidated set of key performance indicators (KPIs) that capture energy efficiency, water use, waste heat utilisation, renewable energy integration, hourly carbon-free matching, embodied carbon, and land use impacts (Table 1). These KPIs are drawn from recent research on energy-efficient and carbon-aware data centre operation, water stewardship, waste heat recovery, and building life cycle analysis, and they provide a unified framework for assessing both technical performance and site-scale environmental outcomes. The inclusion of metrics such as biodiversity/green area intensity and 24/7 CFE match extends beyond traditional PUE-centric evaluations and reflects the broader, multi-dimensional sustainability challenges highlighted in the contemporary literature.

Table 1.

KPI definitions.

The article includes a practitioner-oriented comparison of twelve international case studies reported in the literature, and provides a feasibility assessment for a Polish pilot project in Michalowo, demonstrating the integrated use of biogas-based power supply, adsorption chillers using waste heat, blue–green water retention, and biodiversity-enhancing infrastructure.

In the study, six research questions were prepared and thoroughly examined:

- (1)

- Is it possible to implement green innovations and pro-environmental solutions in data centre facilities?

- (2)

- What environmental issues are crucial to implement in a data centre?

- (3)

- Are blue and green infrastructures part of Green Data Centre development?

- (4)

- Are there examples of realised and designed sustainable data centres with pro-environmental solutions?

- (5)

- Is it possible to define typologies, recommendations, and guidelines for Green Data Centres?

- (6)

- Is it possible to design and implement a Green Data Centre in Poland?”

2. Materials and Methods

The objective of this research was to formulate design recommendations for Green Data Centres and innovative sustainable solutions incorporating green energy with blue–green infrastructure and biomass production, aimed at optimising energy use and reducing overall energy demand. Numerous studies on data centres indicate that this is a current and pressing issue, necessitating the development of appropriate solutions [15,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

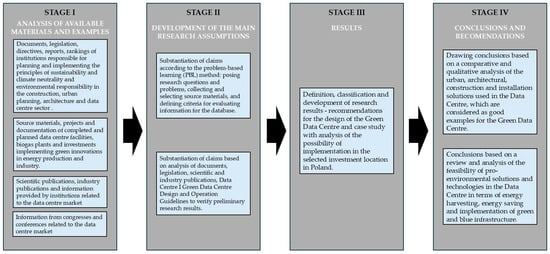

Throughout the process of this study, the analyses of available materials and examples were carried out, based on four types of sources: (1) documents, legislation, directives, reports, rankings of institutions responsible for planning and implementing the principles of sustainability, climate neutrality, and environmental responsibility in the construction, urban planning, architecture, and data centre sectors; (2) source materials, projects and documentation of completed and planned data centre facilities, biogas plants, and investments implementing green innovations in energy production and industry; (3) scientific publications, industry publications, and information provided by institutions related to the data centre market; and (4) information from congresses and conferences related to the data centre market [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Scheme of methods.

Grounded in library and information science, bibliometrics utilises quantitative analysis to explore bibliographic data, enabling a detailed understanding of a research field’s intellectual landscape, and is widely used in contemporary studies [33,34,35,36]. Global scientific output has steadily increased over the past decade, with overall publication volumes growing 4–6% per year and doubling roughly every 17 years [37]. Research in sustainability-related fields, including Green Data Centres, has expanded even faster, with some studies reporting annual growth rates above 13% [38]. This trend highlights the need to contextualise the increases in publications on green and blue infrastructure solutions within the general growth of scientific output.

A comprehensive bibliometric dataset on sustainable data centres was compiled using Publish or Perish 7 [39], a software tool that retrieves bibliographic records primarily from Scopus and computes citation-based metrics, including the annual citation count (ACC). The ACC metric, defined as the total number of citations divided by the number of years since publication, was used to normalise citation impact across publications of different ages.

The search strategy aimed to capture the intersection between data centre research and sustainability-oriented topics. The following Boolean query was employed:

- (“data centre” OR “data centre” OR datacentre)

- AND (sustainab* OR “renewable energy” OR “green computing” OR “energy efficiency”)

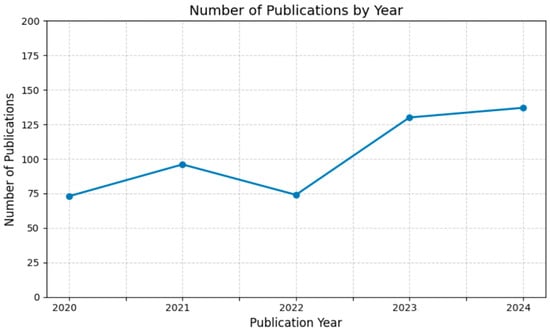

To ensure the inclusion of highly influential studies while accounting for the technical limitation of a maximum of 200 records per query in Publish or Perish, an ACC threshold of ten was applied [Figure 2]. Data were collected on a year-by-year basis, with each year treated as a discrete batch, enabling comprehensive temporal coverage of the period 2020–2024 and minimising truncation effects in years with high publication volumes.

Figure 2.

Number of publications per year with the ACC threshold of ten or more.

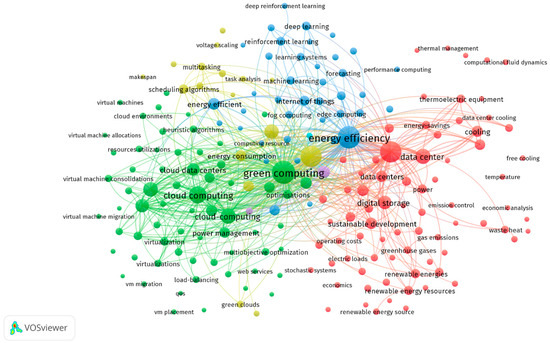

Following data collection, all exported records were merged and de-duplicated based on the DOI and title. The curated dataset was then subjected to bibliometric analysis using VOSviewer 1.6.20, which facilitated the visualisation and mapping of co-authorship networks, keyword co-occurrence, and citation relationships. Complementary analyses and graphical representations have been prepared using Python Jupyter Notebook 7.4.5 [40], leveraging its data processing and visualisation capabilities to enhance the interpretability of the bibliometric results.

This approach allowed for a systematic, high-quality mapping of the literature on sustainable data centres, providing insights into both the evolution of research focus and the influence of seminal studies over time [Figure 3]. The combination of ACC-based filtering, year-by-year batching, and advanced visualisation tools ensured that the dataset was both comprehensive and analytically robust, overcoming inherent limitations in data retrieval from Scopus.

Figure 3.

Keyword cloud for the searches performed.

Additional searches have been performed on different timeframes, and keywords also provided more outcomes. The most recent studies analysed were published in the 2022–2025 time period.

Upon the “Green Data Centre” search in article titles, abstracts and keywords, 162 documents were found.

Upon the “Sustainability” AND “Data centre” search in article titles, abstracts, and keywords, limited to engineering and articles, 333 documents were found.

Upon the “Data centre” AND “biomass” search in article titles, abstracts, and keywords, limited to engineering and articles, 46 documents were found.

Upon the “Sustainability” AND “Methodology” AND “Data centre” search in article titles, abstracts, and keywords, limited to engineering, 104 documents were found.

Upon the “Sustainability” AND “Methodology” search in article titles, abstracts, and keywords, AND the “Data centre” search in keywords, limited to articles, 24 documents were found.

The following data was then carefully analysed and organised in an ordered structure, alongside main attitudes. This approach was employed in contemplations of the definitions of the features that were to be evaluated.

The literature related to the topic of this study can be synthesised into several key aspects: (1) multi-functional and hybrid data centres; (2) power supply from renewable energy sources; (3) minimising the carbon footprint over the entire life cycle of the building; (4) use of passive solutions, optimisation, and flexibility of the building plan; (5) use of blue and green infrastructure; (6) integration of biologically active areas into the building structure; (7) energy-efficient solutions in facility management; (8) use of closed-loop economy solutions; (9) management of water resources; and (10) water retention.

Related to these findings in literature, 12 examples were chosen to be studied for their presence and the degree of their aspects, as they occur distinctively for green data centres. Given the versatility of this outspread and the effective approach of problem-based learning (PBL), the chosen examples stand for an illustration of broader appearances.

In accordance with the problem-based learning (PBL) framework, well rooted and used extensively in many disciplines [41,42,43], claims were substantiated by formulating research questions, identifying and selecting source materials, and defining information assessment criteria for the database. Further validation was achieved through document and legislative analysis, supported by the scientific and professional literature, as well as design and operational guidelines for data centres and Green Data Centres, ensuring the reliability of preliminary findings.

Furthermore, 12 examples of modern data centres were analysed for the above-mentioned features and solutions. These examples were: Data Centre Edge ConneX Gridamatic-Huston; Verne Global (Keflavik, Iceland)—headquarters of the BMW Group and business development organisation Climate Action; Microsoft (Cheyenne, Wyoming); eBay Data Centre (Phoenix, Arizona; and South Jordan, Utah); Echelon Data Centres—DUB20; Hewlett Packard Data Centre (Wynard, UK); NTT America in San Jose; Equinix in Silicon Valley; Facebook Data Centre (Lulea, Sweden); Apple Data Centre (Maiden, North Carolina); Google (Hamina, Finland); and Citi Data Centre (Frankfurt, Germany).

The results of the research are provided, followed by recommendations for the development of designs for Green Data Centres. Basing on the verified approach of using the case study as a method [44], the feasibility of their implementation at a selected investment site in Poland is assessed.

Following that, the results are discussed, and the examined materials are comparatively evaluated. The insights gained form the basis for recommendations, which are summarised in the concluding Section 6. The formulation of the conclusions is based on a comparative and qualitative analysis of urban, architectural, structural, and installation solutions applied in Data Centres, identified as exemplary models for Green Data Centre design. Conclusions are derived from a review and analysis of the feasibility of pro-environmental solutions and technologies in Data Centres, with particular emphasis on energy harvesting, energy efficiency, and the integration of green and blue infrastructure.

3. Results

For many companies in the data centre market, increasing energy efficiency and using environmentally friendly solutions when building such facilities has become a priority. One example is EdgeConneX, which focuses on innovative ways to use technology to achieve energy efficiency. It has implemented an ESG sustainability strategy and plans to become a carbon-neutral, waste-neutral, and water-neutral data centre provider by 2030. This will be made possible by developing and operating a data centre platform powered by 100% renewable energy [45].

Achieving a green data centre with innovative green solutions requires the collaboration of many organisations involved in the development of the facility. A good example of this is the zero carbon data centre Data Plant Wyoming.

The fuel cell at Data Plant Wyoming uses biogas produced at the Dry Creek facility. Biogas is produced as a by-product of municipal wastewater treatment. Anaerobic bacteria produce biogas while stabilising solids removed from wastewater. The fuel cell electrochemically converts biogas into electricity. The resulting energy powers a Microsoft IT server container. In this case, Siemens collaborated with Microsoft and FuelCell Energy to design and install energy-monitoring equipment in the data centre. The project also required collaboration with industry representatives, the University of Wyoming, the Business Council, Cheyenne LEADS, the Cheyenne Board of Public Utilities, the Western Research Institute, and partners from state and local governments [46].

- Summary of analyses of exemplary Green Data Centres

As a result of the analyses of source materials of Data Centre facilities using various pro-environmental solutions, a typology of pro-environmental solutions found in the analysed group of facilities was developed. The selection of facilities for analysis and technical solutions was carried out based on established criteria, centred on analyses of publications concerning Green Data Centres. The data from the analysed cases with green energy solutions are presented below in Table 2, and the division of green innovations and pro-environmental solutions applied in the Data Centre Case studies are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Summary of the best analysed cases using green energy.

Table 3.

Green innovations and pro-environmental solutions applied in the Data Centres case studies. "X" indicates a specific solution used in a given centre.

- 1.

- The use of artificial intelligence to track and measure the 24 h delivery of carbon-free energy (CFE).

Example facility: Data Centre Edge ConneX Gridmatic-Huston [51,52].

- 2.

- Power supply from renewable energy sources, e.g., geothermal and hydropower.

Example facility: Verne Global (Keflavik, Iceland)— the headquarters of the BMW Group and the business development organisation Climate Action [53,54].

- 3.

- Renewable energy supply of biogas fuel cells from wastewater treatment plants.

Example facility: Microsoft (Cheyenne, Wyoming) [55].

- 4.

- Power supply from renewable solar energy sources.

Example facility: eBay Data Centre (Phoenix, Arizona; and South Jordan, Utah) [55].

- 5.

- Power from renewable fuel cell biogas from organic matter (manure, sewage sludge, and food waste).

Example facility: Echelon Data Centres-DUB20 [56].

- 6.

- Power supply from renewable wind energy sources.

Example facility: Hewlett Packard Data Centre (Wynyard, UK) [55].

- 7.

- Power from renewable energy sources: fuel cells from a mixture of natural gas and biogas from a dairy farm.

Example facility: NTT America in San Jose [56].

- 8.

- Power supply from renewable energy sources: biogas fuel cells, an electrochemical process of air, and fuel resulting in water and carbon dioxide.

Example facility: Equinix in Silicon Valley [57].

- 9.

- Innovative air and liquid cooling systems with chilled water energy storage system, HVAC absorbing.

Example facility: Facebook Data Centre (Lulea, Sweden) [54] and Apple Data Centre (Maiden, North Carolina) [54].

- 10.

- Seawater cooling.

Example facility: Google (Hamina, Finland) [54].

- 11.

- Green roof for water retention and insulation to keep the building temperature constant throughout the year.

Example facility: Citi Data Centre (Frankfurt, Germany) [54].

It is worth noting that all of the top-rated data centres base their energy management on renewable sources. A favourable climate—usually associated with low temperatures and constant wind fronts—is also a key factor in the operation of these facilities. It is also worth noting the innovative solutions for air exchange and water use within the buildings, which are also used in these types of facilities. Despite the implementation of numerous pro-environmental solutions related to green and blue infrastructure, few buildings hold global LEED or BREEM certifications. The facilities described above mostly have very similar architectural forms and proportions, rarely incorporating plant elements (e.g., green roofs) into the buildings [47,48,49,50,51,52,53].

- Research summary: Recommended solutions for Green Data Centre:

It is recommended that hybrid solutions are implemented by combining biomass and power generation functions in the Green Data Centre land use. Green and blue infrastructure, properly designed for the data centre, can form the basis of a self-sufficient data centre. Facility management solutions are also recommended.

- Case Study: Example of implementation of recommended green innovations in Green Data Centre in Poland.

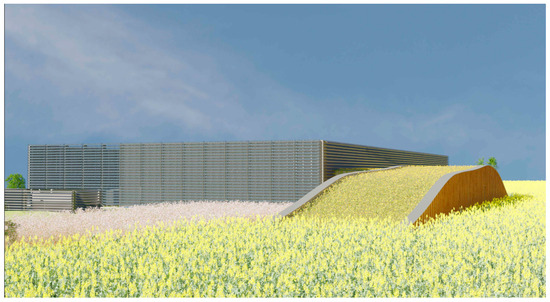

An example of the application of sustainable solutions and green and blue infrastructure in Poland is the analysed investment “Green Data Centre”, prepared for implementation in Poland in the city of Michalowo (Figure 4). The data for the analysis was provided by the investor and designers, with permission to publish non-confidential parts. The Data Centre investment was planned to use green energy from biomass in connection with the existing biogas plant with an electrical capacity of 600 kW and a thermal capacity of 595 kW. There is a photovoltaic farm next to the biogas plants, which can supplement the energy supply. The data centre is to be powered entirely by the neighbouring biogas plants or photovoltaic farm.

Figure 4.

Localization of data centre in Michalowo (Poland).

The spatial layout of the facility was dictated by the requirements of the local plan and functional assumptions. Two buildings were designed, connected by a security sluice with access control and a guard house with a car park roof and a gas drying station. The office building (containing conference rooms, offices, central control room, and social facilities) is a single storey brick building with a green roof and green walls. The building is greened to improve thermal performance and energy efficiency, and to increase the biologically active area. The data centre building (includes IT room, technical rooms, reception area, and warehouses) is a steel frame building with externally shading photovoltaic louvres. To improve energy performance and implement solutions that are favourable to building, life cycle analysis and carbon footprint analysis are conducted.

Blue and green infrastructure solutions are planned for the site (Figure 5 and Figure 6), as follows:

Figure 5.

Visualisation of the Green Data Centre planned for implementation in Poland (bird’s eye view).

Figure 6.

Visualisation of the Green Data Centre planned for implementation in Poland (perspective).

- -

- A system of open rainwater retention basins

- -

- Planting of flowering greenery, including fruit trees.

These solutions will be implemented for biomass production, increased biodiversity, improved ecosystem services, and harmonious integration into the spatial and environmental context.

Buildings will be heated with heat from a local biogas plant, using ‘green energy’ to minimise emissions from energy production. The building will be supplied with two MV lines from two independent gas units of the biogas plant. A further two MV lines are planned for subsequent phases of the project. Two diesel generators with a capacity of 1000 kVA each are planned for the back-up power supply of the server room. In subsequent phases of the investment, further generators will be provided, namely two gas-fuelled generators of 600 kVA each. There will be a built-in transformer station, and the servers will be supplied from two independent power feeds. Each of the feeders will provide an independent power supply sequence from the gas generator source through the MV distribution network, MV switchgear, MV/nn transformer, LV switchgear, UPS, and busbars, with outlet cassettes to the consumer network of busbars in the IT rooms. Fire protection circuit breakers shall be installed in the installation. The buildings will be mechanically ventilated with separate ventilation systems for the office building and the technical building. The office building will be ventilated using a supply and exhaust air handling unit with heat recovery. The amount of ventilation air will be selected based on the projected number of workstations and the projected number of users of the facility.

The process building will be ventilated with the minimum number of air changes for process rooms (0.3–0.5 air changes per hour). In addition, the use of high-capacity fans is foreseen in the gas-extinguishing rooms, to allow for post-extinguishing ventilation. In the process building a precision air-conditioning system for the designed IT chamber will be used, consisting of precision air-conditioning cabinets located in the room immediately adjacent to the IT chamber.

- -

- Pump stations and chilled water loops supplying the air-conditioning cabinets.

- -

- Chillers and adsorption chillers providing the walk-in source for the plant.

All precision air-conditioning units will have n + 1 redundancy. The precision air-conditioning cabinets will be located in the technical room adjacent to the IT chamber to inject cooled and treated air into the underfloor space. Exhaust air will be drawn in from the underfloor space ceiling of the IT chamber. Cabinets will be equipped with an air filter, chilled-water cooler, evaporative humidifier, and a chilled water heat exchanger. A chilled water cooler, evaporative humidifier, and controller will be included for automatic parameter control. The controllers of the individual units are integrated into a single system, enabling redundancy management and turnkey operation. There will be a cooling water supply to cabinets. Chilled water will be supplied to the air-conditioning cabinets via loops in the supply and return pipes. A system of two compressor chillers is envisaged as the source of cooling for the projected installation. The use of adsorption chillers is related to the possibility of obtaining waste heat from nearby biogas plants. Such a solution will increase the energy efficiency of the investment, reduce operating costs, and significantly reduce electricity consumption by the precision air-conditioning system.

The IT chambers, UPS rooms, and electrical switchgear rooms are protected by a fire-extinguishing gas (SUG) system. If a fire is detected in one of the rooms served, gas will be released into the room space, and the air will be removed via a relief valve.

Inergen inert gas characteristics are as follows:

- -

- Gas of natural origin, with no negative impact on the environment;

- -

- Causes no risk of poisoning;

- -

- Odourless gas; not an irritant;

- -

- Reduces the oxygen level in the room, but to a safe degree that allows people to breathe freely;

- -

- Does not react chemically with extinguished objects or human skin;

- -

- Leaves no soiling, haze, or corrosive effect and can be used in server rooms, archives, museums, book collections, or electrical switchboards

4. Green Innovations and Recommendations for Green Data Centres

- Multi-functional and hybrid data centres—combining Data Centre functions with production, e.g., biomass, electricity.

- Power supply from the following renewable energy sources: geothermal, hydro, solar, and wind power, supplied from fuel cells using biogas derived from organic materials or biomass.

The use of local natural conditions for the cooling system, e.g., water or air cooling and the use of waste heat.

- 3.

- Minimised carbon footprint over the entire life cycle of the building (construction, operation, and disposal), e.g., by using low-emission concrete and steel materials and biodegradable materials.

- 4.

- The use of passive solutions, optimisation, and flexibility in the building plan.

- 5.

- The use of blue and green infrastructure with water retention systems in land development.

- 6.

- The integration of biologically active areas into the building structure, through the use of green roofs and green walls.

- 7.

- Energy-efficient solutions in facility management, e.g., the use of artificial intelligence to measure carbon-free energy (CFE) provision and smart LED lighting.

- 8.

- The use of closed-loop economy solutions, such as modern forms of recycling (in the case of IT, pyrolysis, and bioleaching) and the use of recyclable electronic equipment.

- 9.

- Management of water resources (reuse of greywater or rainwater with a treatment system and regulation of water demand and consumption).

- 10.

- Water retention (open or closed retention basins or canals).

- 11.

- Optimisation of carbon footprint:

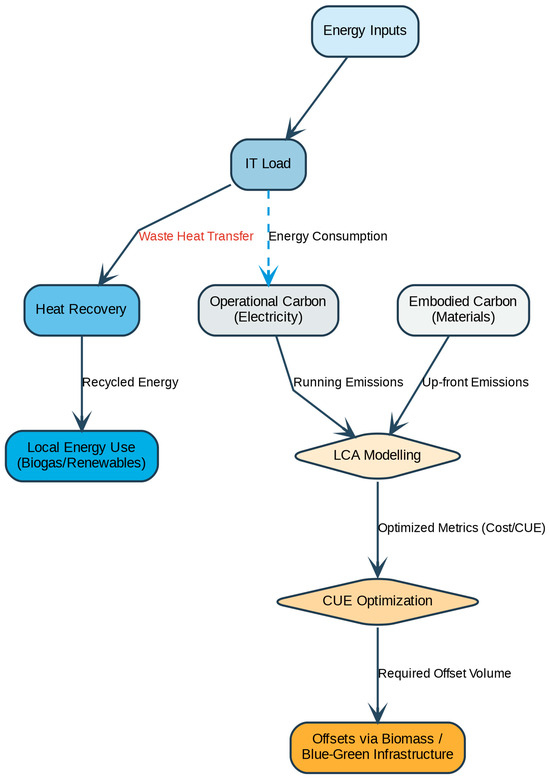

Implementation of low-carbon design strategies that target both the embodied and operational emissions, capturing the whole life cycle of the data centres: combining renewable power procurement, embodied carbon reduction in materials (e.g., low-clinker concrete and recycled steel), and AI-driven workload migration to optimise the real-time carbon intensity of consumed electricity (Figure 7). The integration of dynamic carbon modelling tools supports carbon neutrality targets across design, construction, and operation. This results in higher Carbon Usage Effectiveness (CUE).

Figure 7.

Conceptual framework illustrating the carbon optimisation flow in Green Data Centres.

5. Discussion

The conducted research revealed international publications on the development of Green Data Centres. The analysis of the state of research indicates that there is considerable recognition of the issues in the field of energy-saving solutions and the use of renewable energy sources for data centres. It is indicated that: “Data centre operators must take a leadership role in implementing green technologies and practices, recognising that the long-term benefits far outweigh the initial challenges. The integration of renewable energy, energy-efficient hardware, and advanced cooling systems must become integral components of data centre strategies. (…) Green data centres, through their commitment to sustainability, not only mitigate their environmental footprint but also pave the way for a more conscientious and responsible digital future” (…) “Cooling systems in data centres are critical for maintaining optimal operating temperatures for servers and other hardware” [58].

These are conclusions with which it is difficult to argue. Further published studies analysed elaborate on Green Data Centres in the context of energy efficiency and carbon footprint optimisation [24,59,60,61,62,63,64].

The cost optimisation of green energy is an important research issue. These studies directly indicate the benefits and recommendations of using renewable energy sources in data centre design [65,66]. Research has also been conducted to develop an energy-efficient and carbon-reducing system model named Green Energy Efficiency and Carbon Optimisation (GEECO). The solution involves a series of modules to optimise energy consumption in data centres while maintaining high performance levels with the User Interface (UI) module. Tasks are categorised using the Shortest Processing Time (SPT), Longest Processing Time (LPT), and Longest Setup Times First (LSTF) algorithms to prioritise and schedule them efficiently [13].

Some researchers have been developing studies on the broader context of Sustainable Green Data Centre. Analysing various technical solutions in terms of sustainable design and operation [28,67,68,69].

The indicated published studies are in line with the purpose and conclusions of the research described in this article. The issue of sustainable Green Data Centres requires solutions in various aspects of the design, which consider different criteria for selecting solutions, introducing innovative green solutions in the form of hybrid technologies and combining functions within data centre investments.

The Green Data Centre is based on the sustainability concept with seven critical components: ICT Governance, Energy, Equipment Life Cycle, Green Technology, Benchmarking, and Business Continuity [70,71].

The “Green Data Centre” focuses on reducing energy consumption and carbon emissions through renewable energy sources, energy-efficient equipment, and a cooling system using outside air. The building should apply solutions in the areas of data centre design, management and planning, renewable energy, cooling management system, waste heat reuse, energy efficiency, and water efficiency. In the parameter comparison for Green Data Centres, the performance of eight data centres in terms of parameters was analysed, in terms of PUE energy consumption, PUE heat recovery and reuse system, WUE waste consumption, and place” [71,72,73,74]. The indicated publications make little mention of the application of green and blue infrastructures. The use of biogas plants and the use of biomass are signalled, but without a focus on the broader context of environmental design, biodiversity, and resilience. Also marginal are the issues of water retention and the potential for use in cooling or energy storage in data centre design. Thus, key aspects of shaping a sustainable built environment are sometimes overlooked in data centre design. Even more valuable should be the presented study and selected example case studies indicating the implementation of such solutions. Conducted research and conclusions that constitute proposals for the guidelines for sustainable Green Data Centres are voices in the discussion on land use, shaping architectural and infrastructural solutions of data centres. It is recommended to introduce hybrid solutions, and to combine the functions of biomass production and power generation in the development of Green Data Centres. Green AND blue infrastructures properly designed for data centres can form the basis for data centre self-sufficiency.

6. Conclusions

As a result of the research work, solutions to the analysed issues and research problems were obtained:

The research has shown that it is possible to apply pro-environmental solutions related to energy efficiency, the use of renewable energy sources, energy, and biomass production, with the use of blue–green infrastructure in land development and architectural and construction solutions.

The analysis of source materials and the research conducted showed that the key issues for data centres are the acquisition and production of energy in an environmentally friendly way, as well as heat recovery and cooling installations, and energy-efficient solutions in the buildings. The research underlines that future optimisation of Green Data Centres must not only rely on PUE improvement, but also integrate dynamic carbon tracking and LCA modelling, enabling continuous monitoring and compensation of carbon emissions through renewable energy generation, waste heat recovery, and on-site blue–green systems.

- Analyses of the Sustainable Data Centre model indicate the need for green and blue infrastructure solutions shaping the resilience and self-sufficiency of the Green Data Centre.

- The analysis of source materials and the conducted research has shown that there are realised data centre facilities with pro-environmental “green solutions”. There are also rankings of Green Data Centres that are examples of good practice in sustainable solutions in this sector of activity. Sample Green Data Centre realisations were analysed in the research process.

- As a result of the research, guidelines for Green Data Centre have been identified, which summarise the research process conducted. Recommendations were identified and described in the results of the research. Combining Data Centre functions with biomass production and energy production from biogas plants was shown as particularly important green innovations for data centres. It is also important to introduce mitigation solutions to climate change and, in particular, to reduce the effects of climate change, including risks such as heavy rains, floods, and droughts. To this end, it is recommended to introduce blue–green infrastructure not only for biomass production, but also for water retention and in terms of shaping biodiversity and ecosystem services.

- As a result of the research, it was shown that there are data centre facilities in Poland where environmentally friendly solutions are implemented. In addition, as a result of the research, we managed to establish cooperation with the investor and designers who independently prepared the project and are implementing an investment in Poland, in Michalowo, by implementing green solutions in accordance with the results of the research and the catalogue of solutions for the Green Data Centre.

7. Limitations and Future Research

Although this review integrates energy-efficiency, operational decarbonisation, and site-planning dimensions, several limitations should be acknowledged.

- Survivor bias in case-study selection.

Published case studies overwhelmingly document successful or innovative implementations. Less successful, discontinued, or commercially confidential projects are rarely reported, which may unintentionally overestimate technological maturity or achievable performance.

- 2.

- Limited quantification of blue–green infrastructure benefits.

Although the review identifies opportunities arising from water retention, biodiversity enhancement, cooling synergy, and biomass production, the available literature offers limited quantitative evidence—for example, measured reductions in water use (L/kWh), quantified WHR contributions to thermal loads, or LCA-based estimates of embodied-carbon reduction from nature-based interventions.

- 3.

- Bibliometric and literature search constraints.

Despite the use of structured search queries, the academic literature tends to lag behind the fast-moving industrial practice. This may underrepresent operator-level sustainability data, hourly CFE datasets, emerging flexibility metrics, and engineering reports not indexed in scientific databases.

In the area of sustainable data centres, a few future research directions could be identified:

- Include negative and partial-success cases to mitigate publication and survivor bias and better understand barriers to adoption.

- Integrate LCA approaches, comparing biogas/fuel cell integration, adsorption–chiller cooling, district–heating coupling, and blue–green configurations.

- Advance spatial and GIS-based modelling to optimise the co-location of biogas plants, renewable sources, and hydrological retention aligned with local infrastructure and climate constraints.

Author Contributions

M.G.-S.: Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing-original draft preparation, writing-review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition; E.M.: Validation, data curation, writing-original draft preparation, writing-review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition; P.B.: Validation, data curation, writing- review and editing; M.P.-M. Software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing original draft preparation, writing-review and editing, visualisation; M.P.: Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing-original draft preparation, writing- review and editing; O.A.: Methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing-original draft preparation, writing- review and editing; K.R.-N.: Methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing-original draft preparation writing-review and editing; T.W.: Validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing-original draft preparation, visualisation; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research was funded by Warsaw University of Technology within the Excellence Initiative: Research University (IDUB) programme, supported by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, ARCHIURB—grant number CPR-IDUB/236/Z01/2024.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgmentss: We would like to acknowledge the financial and organisational support given by the team from the Warsaw University of Technology for the Excellence Initiative: Research University (IDUB), the Science Committee of the Warsaw University of Technology, and the Research Team of the Faculty of Architecture at the Warsaw University of Technology. We would like to thank Wężyk Architekci Ltd. and Archibiuro Ltd. and Eko Dane Ltd. for providing materials for analysis and documentation of the “Green Data Centre” investment containing solutions subject to analysis and illustrating the conclusions of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Tomasz Wężyk was employed by the company Wężyk Architekci Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- IEA. Electricity 2024; IEA: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/electricity-2024 (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Directive (EU) 2023/1791 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 September 2023 on Energy Efficiency and Amending Regulation (EU) 2023/955 (Recast). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ%3AJOL_2023_231_R_0001&qid=1695186598766#d1e32-90-1 (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- European Council. European Green Deal. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/green-deal/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- European Council. Fit for 55: EU Emissions Trading System. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/fit-for-55-eu-emissions-trading-system/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- European Committee for Standardization (CEN). EN 15978: Sustainability of Construction Works—Assessment of Environmental Performance of Buildings—Calculation Method; CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Level(s): A Common EU Framework for Sustainable Buildings. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/levels_en (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Mordor Intelligence. Green Data Central Market—Growth, Trends and Forecast 2020–2025. Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/global-green-datacenter-market-industry (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Luo, J.; Li, H.; Liu, J. How Green Data Center Establishment Drives Carbon Emission Reduction: Double-Edged Sword or Equilibrium Effect? Sustainability 2025, 17, 6598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-C.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, Q. How does information and communication technology affect energy security? International evidence. Energy Econ. 2022, 109, 105969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liu, W. Carbon reduction effects of digital technology transformation: Evidence from the listed manufacturing firms in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2024, 198, 122999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murino, T.; Monaco, R.; Nielsen, P.S.; Liu, X.; Esposito, G.; Scognamiglio, C. Sustainable Energy Data Centres: A Holistic Conceptual Framework for Design and Operations. Energies 2023, 16, 5764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voumik, L.C.; Islam, M.A.; Ray, S.; Mohamed Yusop, N.Y.; Ridzuan, A.R. CO2 Emissions from Renewable and Non-Renewable Electricity Generation Sources in the G7 Countries: Static and Dynamic Panel Assessment. Energies 2023, 16, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Faruk, F.B.; Rajbongshi, D.; Efaz, M.M.K.; Islam, M.M. GEECO: Green Data Centers for Energy Optimization and Carbon Footprint Reduction. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katal, A.; Dahiya, S.; Choudhury, T. Energy efficiency in cloud computing data centers: A survey on software technologies. Clust. Comput. 2023, 26, 1845–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chountalas, P.T.; Chrysikopoulos, S.K.; Agoraki, K.K.; Chatzifoti, N. Modeling Critical Success Factors for Green Energy Integration in Data Centers. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Han, K.; Han, T.; Wang, Y.; Han, Y.; Lin, J. Data-Driven Distributionally Robust Optimization of Low-Carbon Data Center Energy Systems Considering Multi-Task Response and Renewable Energy Uncertainty. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 102, 111937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazanfari-Rad, S.; Ebneyousef, S. A Survey of Renewable Energy Approaches in Cloud Data Centers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Technology and Energy Management, ICTEM, Mazandaran, Babol, Iran, 8–9 February 2023; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, S.; Gou, Z. A Comprehensive Analysis of Green Building Rating Systems for Data Centers. Energy Build. 2023, 284, 112874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.; Østergaard, P.A.; Mathiesen, B.V. Turning waste heat from data centres (ICT) into usable heat. Energy Effic. 2019, 12, 1569–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antal, M.; Cioara, T.; Anghel, I.; Gorzeński, R.; Januszewski, R.; Oleksiak, A.; Piatek, W.; Pop, C.; Salomie, I.; Szeliga, W. Reuse of data center waste heat in nearby neighborhoods: A neural networks-based prediction model. Energies 2019, 12, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newkirk, A.C.; Hanus, N.; Payne, C.T. Expert and Operator Perspectives on Barriers to Energy Efficiency in Data Centers. Energy Effic. 2024, 17, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyya, R.; Ilager, S.; Arroba, P. Energy-Efficiency and Sustainability in New Generation Cloud Computing: A Vision and Directions for Integrated Management of Data Centre Resources and Workloads. Softw. Pract. Exp. 2024, 54, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, B.; Denny, E.; Fitiwi, D.Z. The Benefits of Low-Carbon Energy Efficiency Technology Adoption for Data Centres. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2023, 20, 100447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldossary, M.; Alharbi, H.A. An eco-friendly approach for reducing carbon emissions in cloud data centres. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 72, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, X.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, X.; Peng, Y. A forecast-driven workload scheduling scheme for carbon-aware data centres with wind integration. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2025, 48, 101216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, A.; Noor, K.N.; Abir, T.A.; Rana, S.; Ali, M. Design and analysis of sustainable green data center with hybrid energy sources. J. Power Energy Eng. 2021, 9, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, J.; Han, Y.; Han, K.; Han, J.; Han, T.; Wei, Y.M. Comprehensive Evaluation of All-Element Flexibility Resources in Data Centers: Considering Synergistic Benefits of Computing, Electricity, and Heat. Appl. Energy 2025, 399, 126442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdecchia, R.; Lago, P.; De Vries, C. The future of sustainable digital infrastructures: A landscape of solutions, adoption factors, impediments, open problems, and scenarios. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2022, 35, 100767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, N.; Kaur, N.; Singh Saini, K.; Verma, S.; Abu Khurma, R.; Castillo Valdivieso, P.Á. Maximizing Resource Efficiency in Cloud Data Centers through Knowledge-Based Flower Pollination Algorithm (KB-FPA). Comput. Mater. Contin. 2024, 79, 3757–3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Han, K.; Lin, J.; Han, J.; Song, K.; Tang, H.; Han, T. Bi-level optimization and sustainability assessment of data center integrated energy system based on emergy theory. Energy 2025, 334, 137689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.V.; Karri, G.R. An Efficient Multi-Objective Task Scheduling for Green Cloud Computing Using Hybrid GSCOA Algorithm. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2025, 48, 101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölbling, S.; Kirchengast, G.; Briese, C.; Thüminger, H. Energy Use and Carbon Emissions in High-Performance Computing: A Case Study for Universities and Reduction Strategies. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2025, 19, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysikopoulos, S.K.; Chountalas, P.T.; Georgakellos, D.A.; Lagodimos, A.G. Green Certificates Research: Bibliometric Assessment of Current State and Future Directions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahers, J.-B.; Athanassiadis, A.; Perrotti, D.; Kampelmann, S. The place of space in urban metabolism research: Towards a spatial turn? A review and future agenda. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 221, 104376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munaro, M.R.; Tavares, S.F.; Bragança, L. Towards circular and more sustainable buildings: A systematic literature review on the circular economy in the built environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornmann, L.; Mutz, R. Growth rates of modern science: A bibliometric analysis based on the number of publications and cited references. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Science Foundation (NSF). Publication Output by Region, Country, or Economy and by Scientific Field, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. 2023. Available online: https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsb202333/publication-output-by-region-country-or-economy-and-by-scientific-field (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Harzing, A.W. Publish or Perish. 2007. Available online: https://harzing.com/resources/publish-or-perish (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Granger, B.E.; Pérez, F. Jupyter: Thinking and Storytelling with Code and Data. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2021, 23, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colmenares-Quintero, R.F.; Caicedo-Concha, D.M.; Rojas, N.; Stansfield, K.E.; Colmenares-Quintero, J.C. Problem based learning and design thinking methodologies for teaching renewable energy in engineering programs: Implementation in a Colombian university context. Cogent Eng. 2023, 10, 2164442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento-Rojas, J.; Aya-Parra, P.A.; Perdomo, O.J. Proposal of Design and Innovation in the Creation of the Internet of Medical Things Based on the CDIO Model through the Methodology of Problem-Based Learning. Sensors 2022, 22, 8979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Melia, D.; Gutiérrez-Bahamondes, J.H.; Iglesias-Rey, P.L.; Martinez-Solano, F.J. Exploring the synergy of problem-based learning and computational fluid dynamics in university fluid mechanics instruction. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2024, 32, e22782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavarda, R.; Bellucci, C.F. Case study as a suitable method to research strategy as practice perspective. Qual. Rep. 2022, 27, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EdgeConneX. Sustainability. Available online: https://www.edgeconnex.com/company/sustainability/ (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Cheyenne Leads. Ceremony to Mark Biogas-Powered Microsoft Data Plant Operation. Available online: https://cheyenneleads.org/ceremony-to-mark-biogas-powered-microsoft-data-plant-operation/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Eaton. (n.d.). Eaton Enables Always-On Operations for 100 Percent Renewable Power Data Center. Verne Global. Available online: https://www.eaton.com/content/dam/eaton/markets/data-center/Verne-Global-Eaton-enables-always-on-operations-for-100-percent-renewable-power-data-center.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Microsoft. Wyoming (West Central US) Data Center Overview. Microsoft Data Centers. 2024. Available online: https://datacenters.microsoft.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Wyoming%20%28West%20Central%20US%29.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Data Center Knowledge. (n.d.). eBay Goes Live with Its Bloom-Powered Data Center. Available online: https://www.datacenterknowledge.com/energy-power-supply/ebay-goes-live-with-its-bloom-powered-data-center (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Best CTR. Case Study: eBay Data Center; 2014. Available online: https://www.bestctr.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/CaseStudy_eBayDatacenter.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Carbon Wire. Redefining Sustainability in Data Center Infrastructure. Available online: https://carbonwire.org/carbon-voices/redefining-sustainability-in-data-center-infrastructure/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- EdgeConneX. Structure Research State of Environmental Impact Report: A Closer Look. Available online: https://www.edgeconnex.com/company/edge-blog/structure-research-state-of-environmental-impact-report-a-closer-look/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Verne Global. Available online: https://verneglobal.com/ (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- GreenBiz. 12 Green Data Centers Worth Emulating. Available online: https://www.greenbiz.com/article/12-green-data-centers-worth-emulating-apple-verne (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Data Data Center Dynamics. Echelon Given Go-Ahead for 100 MW Ireland Campus. Available online: https://www.datacenterdynamics.com/en/news/echelon-given-go-ahead-100mw-ireland-campus/ (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Data Center Dynamics. Echelon Data Centres to Make Biogas at County Wicklow, Ireland Campus. Available online: https://www.datacenterdynamics.com/en/news/echelon-data-centres-to-make-biogas-at-county-wicklow-ireland-campus/ (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Data Center Knowledge. Equinix Using Bloom Biogas Fuel Cells at Silicon Valley Data Center. Available online: https://www.datacenterknowledge.com/hyperscalers/equinix-using-bloom-biogas-fuel-cells-at-silicon-valley-data-center (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Chidolue, O.; Ohenhen, P.E.; Umoh, A.A.; Ngozichukwu, B.; Fafure, A.V.; Ibekwe, K.I. Green Data Centers: Sustainable Practices for Energy-Efficient It Infrastructure. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 2024, 5, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osibo, B.; Adamo, S. Data Centers and Green Energy: Paving the Way for a Sustainable Digital Future. Int. J. Latest Technol. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. 2023, 12, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamkhari, M.; Mohsenian-Rad, H. Energy and performance management of green data centers: A profit maximization approach. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2013, 4, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, P.; Wang, K.; Sun, Y.; Zeng, D.; Wang, X.; Guo, S. Joint workload scheduling and energy management for green data centers powered by fuel cells. IEEE Trans. Green Commun. Netw. 2019, 3, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Shen, H. Minimizing the operation cost of distributed green data centers with energy storage under carbon capping. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 2021, 118, 28–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basmadjian, R. Flexibility-Based Energy and Demand Management in Data Centers: A Case Study for Cloud Computing. Energies 2019, 12, 3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.; Rahman, A.A. Techniques to implement in green data centers to achieve energy efficiency and reduce global warming effects. Energies 2011, 3, 372–389. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Li, P.; Sun, Y. Minimizing Energy Cost for Green Data Centers by Exploring Heterogeneous Energy Resources. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2021, 9, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, R.; Vignesh, S.; Tamarapalli, V. Optimizing Green Energy, Cost, and Availability in Distributed Data Centers. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2017, 21, 500–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuja, J.; Gani, A.; Shamshirband, S.; Ahmad, R.W.; Bilal, K. Sustainable cloud data centers: A survey of enabling techniques and technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, S.; Jambari, D.I. Capacity Planning for Green Data Center Sustainability. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2018, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.; Rahman, A.A. Validation of green IT framework for implementing energy-efficient green data centers: A case study. Int. J. Green Econ. 2012, 6, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naufal Austen, M.F.; Subroto, A. Enabling Practical Decision Making for Sustainable Green Data Center Planning. J. Ekon. 2023, 28, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorowar, I.B.; Shawon, M.A.; Mozumder, D.; Hossain, J.H.; Islam, M.M. Design and Functional Implementation of Green Data Center. In Proceedings of the International Conference on IoT Based Control Networks and Intelligent Systems, Bengaluru, India, 21–22 June 2023; pp. 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peoples, C.; Parr, G.; McClean, S.; Scotney, B.; Morrow, P. Performance evaluation of green data centre management supporting sustainable growth of the internet of things. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2013, 34, 221–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, K.; Khan, S.U.; Zomaya, A.Y. Green data center networks: Challenges and opportunities. In Proceedings of the 2013 11th International Conference on Frontiers of Information Technology, Islamabad, Pakistan, 16–18 December 2013; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 229–234. [Google Scholar]

- Building Energy Codes Working Group. International Review of Energy Efficiency in Data Centres for IEA EBC Building Energy Codes Working Group; Ballarat Consulting for the Building Energy Codes Working Group (BECWG): Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).