Abstract

Photovoltaic systems (PV) are increasingly recognized as fundamental to the worldwide adoption of renewable energy technologies. Nonetheless, the efficiency and longevity of solar panels can be compromised by various anomalies, ranging from physical defects to environmental impacts. Early and accurate detection of these anomalies is crucial for maintaining optimal performance and preventing significant energy losses. This study presents SolarAttnNet, a novel convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture with integrated channel and spatial attention mechanisms for solar panel anomaly detection. The proposed model addresses the critical need for automated detection systems, which are crucial for maintaining energy production efficiency and optimizing maintenance. This approach leverages attention mechanisms that emphasize the most relevant features within thermal and visual imagery, improving detection accuracy across multiple anomaly types. SolarAttnNet is evaluated on three distinct solar panel datasets, demonstrating its effectiveness through comprehensive ablation studies that isolate the contribution of each architectural component. Experimental results show that SolarAttnNet achieves superior performance compared to state-of-the-art methods, with accuracy improvements of 3.9% on the PV Systems-AD dataset (94.2% vs. 90.3%), 3.6% on the InfraredSolarModules dataset (92.1% vs. 88.5%), and 3.5% on the RoboflowAnomalies dataset (89.7% vs. 86.2%) compared to baseline ResNet-50. For challenging subtle anomalies like cell cracks and PID, the proposed model demonstrates even more significant improvements with F1-score gains of 4.8% and 5.4%, respectively. Ablation studies reveal that the channel attention mechanism contributes a 2.6% accuracy improvement while spatial attention adds 2.3% across datasets. This work contributes to advancing automated inspection technologies for renewable energy infrastructure, supporting more efficient maintenance protocols and ultimately enhancing solar energy production.

1. Introduction

The escalating global energy crisis and growing environmental concerns have accelerated the adoption of renewable energy sources, with solar power emerging as one of the most promising alternatives to fossil fuels [1]. Solar photovoltaic (PV) installations have seen exponential growth worldwide, with global capacity increasing from 40 GW in 2010 to over 760 GW by 2024 [2]. However, the efficiency and durability of solar panels are significantly affected by various anomalies and defects that develop over time, including hot spots, cell cracks, potential induced degradation (PID), bypass diode failures, and soiling [3]. These anomalies can reduce energy output by up to 30% and potentially lead to complete module failure if left undetected [4,5]. Traditional manual inspection methods for solar panel anomalies are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and often inconsistent. They typically involve visual inspections or thermal imaging conducted by technicians, which becomes increasingly impractical as solar installations grow in scale. While analytical methods for predicting voltage sags in complex power networks can improve the assessment of power quality under fault conditions [6], they are not directly suited for visual defect detection in solar panels. A typical utility-scale solar farm may contain hundreds of thousands of panels spread across vast areas, making comprehensive manual inspection economically unfeasible [7]. Furthermore, some defects are not visible to the naked eye or only manifest under specific operating conditions, making them easy to miss during routine inspections.

The emergence of deep learning techniques, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), has opened new possibilities for automated anomaly detection in solar panels. CNNs have demonstrated remarkable success in computer vision tasks, including object detection, segmentation, and classification [8]. However, applying these techniques to solar panel anomaly detection presents unique challenges [9,10]. Solar panel defects often exhibit subtle visual or thermal signatures that can be difficult to distinguish from normal variations. Additionally, environmental factors such as lighting conditions, panel orientation, and weather can significantly affect the appearance of anomalies in captured images.

Recent research has explored various CNN architectures for solar panel defect detection, with promising results. However, most existing approaches treat all spatial regions and feature channels equally, potentially limiting their ability to focus on the most discriminative features for anomaly detection [11]. Attention mechanisms, which have revolutionized natural language processing and are increasingly being applied to computer vision tasks, offer a potential solution to this limitation by dynamically emphasizing relevant features while suppressing irrelevant ones.

Conventional approaches to solar panel inspection primarily rely on electrical measurements, visual inspections, and thermal imaging [12]. Electrical methods, such as current-voltage (I-V) curve analysis and electroluminescence (EL) testing, can identify performance degradation but often cannot pinpoint the specific defect or its location [13]. Visual inspections conducted by technicians can detect visible defects like cracks, discoloration, and soiling but are subjective, time-consuming, and may miss subtle anomalies [14]. Thermal imaging using infrared cameras has become increasingly popular for identifying hot spots and temperature irregularities that indicate potential defects; however, manual interpretation of thermal images is still prone to human error and inconsistency [15].

While Vision Transformers (ViTs) have shown impressive performance across various computer vision tasks, they typically require large-scale datasets and substantial computational resources to achieve optimal performance. In contrast, hyperspectral datasets—especially in the context of solar panel monitoring—are often limited in size, domain-specific, and high-dimensional, making ViTs more prone to overfitting in such settings.

In this paper, we propose SolarAttnNet, a novel CNN architecture that incorporates both channel and spatial attention mechanisms specifically designed for solar panel anomaly detection. The channel attention mechanism helps the model to focus on the most informative feature channels, while the spatial attention mechanism highlights regions of interest within the feature maps. By combining these complementary attention mechanisms, SolarAttnNet can more effectively capture the subtle and diverse manifestations of solar panel anomalies.

SolarAttnNet is evaluated on three distinct datasets representing different imaging modalities and anomaly types commonly encountered in solar panel inspection. Comprehensive ablation studies isolate and quantify the contribution of each component of the architecture, providing insights into their relative importance for different types of anomalies. Experimental results demonstrate that SolarAttnNet outperforms existing state-of-the-art methods, particularly for subtle anomalies that are challenging to detect with conventional approaches.

The main contributions of this study are:

- A novel CNN architecture (SolarAttnNet) that integrates channel and spatial attention mechanisms specifically designed for solar panel anomaly detection.

- Comprehensive ablation studies that quantify the contribution of each architectural component across different datasets and anomaly types.

- Extensive experimental evaluation on three distinct solar panel anomaly datasets, demonstrating superior performance compared to state-of-the-art methods.

In contrast to existing attention modules such as SENet and CBAM, the proposed SolarAttnNet architecture incorporates a number of PV-specific design choices. These include a rebalanced channel reduction ratio tailored to the thermal and structural properties of solar panel anomalies, a lightweight backbone optimized for small infrared images and UAV deployment constraints, and an attention sequence refined through extensive ablation studies. These architectural modifications collectively enable SolarAttnNet to achieve statistically significant improvements over CBAM-ResNet-50 and SENet-based variants across all datasets, particularly for subtle anomalies such as cell cracks and PID.

The structure of this paper is arranged as follows. In Section 2, we discuss previous studies related to solar panel anomaly detection and the use of attention modules in CNN-based models. Section 3 presents the proposed SolarAttnNet framework and details its methodological design, datasets, and implementation procedures. The experimental configuration, obtained results, and comparative evaluations are reported in Section 4. Lastly, Section 5 summarizes the main findings and highlights potential avenues for future research.

2. Literature Review

The field of solar panel anomaly detection has evolved significantly in recent years, shifting from labor-intensive manual inspection toward fully automated approaches supported by machine learning and computer vision techniques. This section reviews relevant studies with an emphasis on deep learning methods for solar panel defect detection and the integration of attention mechanisms into convolutional neural networks (CNNs).

The limitations of traditional inspection methods have driven researchers to adopt machine learning techniques to improve the automation and accuracy of solar panel monitoring. Early approaches relied on classical machine learning algorithms such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Random Forests, and k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), together with handcrafted image features. For example, Tsanakas et al. [16] employed texture-based descriptors together with SVMs to classify defects in thermal images, whereas Aghaei et al. [17] combined color and texture features with Random Forests to detect soiling and physical damage. Although these methods performed better than manual inspection, their effectiveness was constrained by the limited expressiveness of handcrafted features, which often failed to capture the subtle and complex characteristics of solar panel anomalies. This shortcoming motivated the shift toward deep learning methods capable of learning hierarchical features directly from data.

Deep learning, particularly CNNs, has become the dominant paradigm for solar panel anomaly detection due to its superior feature extraction capabilities. Bartler et al. [18] were among the first to apply CNNs for detecting cracks in electroluminescence images, achieving markedly higher accuracy compared to traditional image processing techniques. Chen et al. [19] subsequently introduced a multi-scale CNN architecture designed to identify defects at different spatial scales. More advanced models have followed: Tang et al. [20] employed Faster R-CNN for simultaneous detection and classification of multiple defect types using visual and infrared imagery. Lee et al. [21] proposed a deep residual network with a feature pyramid module to address scale variation among defects, achieving state-of-the-art results on several benchmark datasets. Additionally, Akram et al. [22] developed a lightweight CNN architecture optimized for deployment on edge devices, enabling real-time monitoring of photovoltaic installations.

Despite these advances, most CNN-based approaches treat all spatial regions and feature channels uniformly, limiting their ability to emphasize the most informative features for anomaly detection. This limitation has led to increasing interest in attention mechanisms to enhance CNN representational power.

Attention mechanisms enable neural networks to selectively focus on relevant information while suppressing less important features. Originally developed for natural language processing, attention mechanisms have since been adapted for a wide range of computer vision tasks, including classification, detection, and segmentation. In CNNs, two major categories of attention mechanisms exist: channel attention and spatial attention. Hu et al. [23] introduced the influential Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) block, which models channel interdependencies to recalibrate channel-wise feature responses. In contrast, spatial attention emphasizes important spatial regions within feature maps. Woo et al. [24] proposed the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM), which integrates both channel and spatial attention sequentially and has demonstrated consistent improvements across various vision tasks.

Recent studies have also applied attention mechanisms for anomaly detection in broader contexts. For example, Qu et al. [25] proposed an attention-guided feature fusion model for industrial inspection, while Wang et al. [26] developed a dual-attention mechanism for medical image anomaly detection. However, the explicit use of attention mechanisms in solar panel anomaly detection remains relatively limited, indicating a promising direction for future research.

Despite these advances, most CNN-based approaches treat all spatial regions and feature channels uniformly, limiting their ability to emphasize the most informative features for anomaly detection [27,28]. This is particularly problematic for subtle defects such as micro-cracks or early-stage PID, where discriminative features may be localized and low-contrast [29]. Furthermore, many existing models are evaluated on limited or single-modality datasets, raising concerns about their generalization to diverse real-world inspection scenarios (e.g., aerial vs. ground-based, infrared vs. visible spectrum) [30].

Recently, Vision Transformers (ViTs) and hybrid CNN–ViT models have shown promising results in various computer vision tasks, including industrial inspection [31,32]. In the PV domain, several studies have begun exploring transformer-based architectures for defect detection, leveraging their global self-attention mechanism to capture long-range dependencies. However, ViTs typically require large-scale training data and substantial computational resources [31], which are often scarce in specialized domains like solar panel inspection. Hybrid approaches that combine CNNs’ local feature extraction with transformers’ global reasoning have been proposed to mitigate these issues [33], but their application to multi-modal solar imagery remains underexplored.

Concurrently, lightweight attention mechanisms—such as Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) and simplified spatial attention modules—have emerged to reduce computational overhead while preserving performance. These designs are particularly relevant for real-time and edge-based PV monitoring but have not been systematically evaluated for solar panel anomalies [34].

Against this backdrop, several research gaps motivate the present work:

- Most existing CNN-based approaches for solar panel anomaly detection do not incorporate attention mechanisms, potentially limiting their sensitivity to subtle and localized defects.

- The relative contribution of different attention types (channel vs. spatial) for solar panel anomaly detection has not been systematically studied across multiple datasets and imaging modalities.

- There is a lack of comprehensive evaluation of attention-enhanced models in comparison to modern baselines, including ViTs and hybrid architectures, within the PV domain.

- Practical deployment aspects—such as model size, inference speed, and suitability for edge devices—are often overlooked in favor of pure accuracy metrics.

The proposed SolarAttnNet architecture addresses these gaps by integrating both channel and spatial attention mechanisms into a computationally efficient CNN backbone, rigorously evaluating its performance across three distinct datasets, and comparing it with state-of-the-art methods including attention-augmented CNNs and transformer-based models where applicable.

3. Materials and Methods

This section details the proposed SolarAttnNet architecture, including the design of the channel and spatial attention mechanisms, the overall network structure, and the training methodology. The datasets used for evaluation, implementation details, and experimentation setup are also described.

3.1. SolarAttnNet Architecture

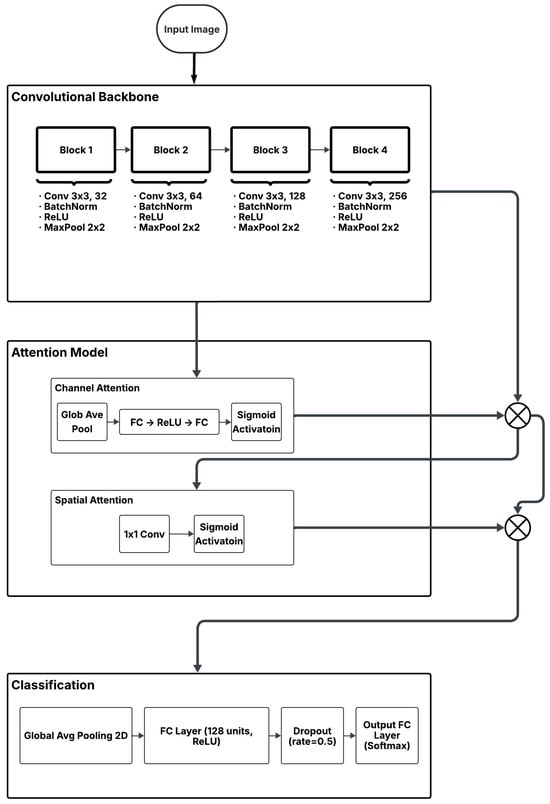

SolarAttnNet is a novel CNN architecture designed specifically for solar panel anomaly detection. The architecture integrates both channel and spatial attention mechanisms to enhance the model’s ability to focus on relevant features for anomaly detection. Figure 1 illustrates the overall architecture of SolarAttnNet.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the proposed SolarAttnNet model, illustrating the integration of channel and spatial attention modules within the CNN backbone.

SolarAttnNet integrates channel and spatial attention mechanisms into a CNN backbone optimized for solar panel inspection. While the attention modules draw inspiration from SE blocks and CBAM, their configuration, hyperparameters, and placement are specifically designed for the characteristics of solar panel anomalies—such as localized thermal signatures (hot spots), fine cracks, and diffuse degradation patterns (PID). The following subsections detail the architecture and justify design choices based on ablation studies and domain requirements.

3.1.1. Convolutional Backbone

The backbone of SolarAttnNet is composed of a series of convolutional blocks designed to progressively extract hierarchical and increasingly abstract features from the input image. Each block consists of a convolutional layer with 3 × 3 kernels, which effectively captures local spatial patterns. This is followed by batch normalization to stabilize and accelerate the training process by normalizing the feature distributions. A ReLU activation function is then applied to introduce non-linearity, enabling the network to learn complex representations. Max pooling with 2 × 2 kernels and a stride of 2 is used to reduce the spatial dimensions, thereby decreasing computational cost while preserving essential features. As the network depth increases, the number of filters in the convolutional layers is progressively scaled up in the order of 32, 64, 128, and 256, allowing the model to capture more complex and high-level features. This architectural design is inspired by the VGG network. Still, it is carefully modified to improve computational efficiency and make it better suited for the specific task of solar panel anomaly detection.

3.1.2. Channel Attention Module

The channel attention module is designed to highlight informative feature channels while suppressing those that are less relevant, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to focus on meaningful representations. Inspired by the Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) network, this module is specifically adapted for the context of solar panel anomaly detection. It begins with the application of global average pooling to each feature channel, resulting in a compact channel descriptor that captures global spatial information across the entire feature map. This descriptor is then passed through a two-layer fully connected network with a bottleneck structure to effectively model inter-channel dependencies. The first fully connected (FC) layer reduces the dimensionality by a factor of 8, known as the reduction ratio, which serves to compress the descriptor and highlight the most critical features. A ReLU activation is then applied to introduce non-linearity. The second FC layer restores the descriptor to its original dimensionality, followed by a sigmoid activation that outputs channel attention weights in the range [0, 1]. These weights reflect the relative importance of each channel. Finally, the original feature maps are scaled by the computed attention weights through element-wise multiplication, enabling the network to selectively emphasize the most informative channels during subsequent processing stages.

The mathematical formulation of the channel attention module is as follows:

where F is the input feature map, is the result of global average pooling, and are the weights of the two fully connected layers, is the ReLU activation, is the sigmoid activation, ⊗ represents channel-wise multiplication, and is the channel-attended feature map.

For solar panel anomalies, the channel attention mechanism plays a crucial role because different types of defects manifest distinct spectral or thermal signatures. Hot spots and bypass diode failures typically produce high-intensity thermal gradients that are captured in specific feature channels, while anomalies such as cell cracks and PID produce more subtle structural patterns across multiple channels. Channel attention enables the model to amplify these anomaly-specific feature channels by learning which spectral or thermal bands contain the most discriminative cues for each defect type. As a result, the model becomes more sensitive to the subtle, low-contrast features associated with cracks and PID, while still accurately responding to the strong thermal cues of hot spots and diode failures.

3.1.3. Spatial Attention Module

The spatial attention module complements the channel attention module by identifying and emphasizing important spatial regions within the feature maps. It begins by applying both max pooling and average pooling operations along the channel dimension, effectively summarizing the spatial information from different perspectives. The outputs of these two pooling operations are then concatenated to form a comprehensive and efficient spatial descriptor. This descriptor is subsequently processed by a convolutional layer with 7 × 7 kernels, which captures spatial dependencies and generates a spatial attention map. Finally, this attention map is applied to the input feature maps through element-wise multiplication, allowing the model to focus on the most relevant spatial regions that contribute to accurate anomaly detection.

The mathematical formulation of the spatial attention module is as follows:

where F is the input feature map, and represent max pooling and average pooling operations along the channel dimension, represents concatenation, is a convolutional layer with 7 × 7 kernels, is the sigmoid activation, ⊗ represents element-wise multiplication, and is the spatial-attended feature map.

Spatial attention complements this by identifying the precise locations where anomalies occur. Hot spots and diode failures are typically concentrated in localized, high-temperature regions, whereas cell cracks and PID often produce elongated, irregular spatial patterns across the module surface. The spatial attention module learns these characteristic shapes by highlighting the relevant areas in the feature maps and suppressing background regions. This spatial selectivity is critical for distinguishing subtle cracks or PID lines from normal texture and helps the model localize the fault-affected areas even when the anomaly occupies a small portion of the image.

3.1.4. Integration of Attention Mechanisms

In SolarAttnNet, the channel and spatial attention mechanisms are applied sequentially after the final convolutional block (Block 4) to refine the high-level features before classification. The feature maps from the backbone are first processed by the channel attention module, which emphasizes the most informative channels. These channel-refined feature maps are subsequently passed through the spatial attention module, which highlights the most relevant spatial regions. The resulting feature maps, now enhanced by both attention mechanisms, are then forwarded to the classification head. Initially, the feature maps generated by the convolutional backbone are processed by the channel attention module, which emphasizes the most informative channels. These channel-refined feature maps are subsequently passed through the spatial attention module, which highlights the most relevant spatial regions within the selected channels. The resulting feature maps, now enhanced by both attention mechanisms, are then forwarded to the classification head for final prediction. This sequential configuration enables the model to effectively prioritize both the salient channels and their corresponding spatial regions, thereby improving overall performance.

3.1.5. Classification Head

The classification head in SolarAttnNet is designed to transform the refined feature maps into final class predictions. It begins with a global average pooling layer, which reduces the spatial dimensions of the feature maps by computing the average value of each channel, thereby preserving the most salient information in a compact form. This is followed by a fully connected layer equipped with a dropout mechanism (with a rate of 0.5) to reduce the risk of overfitting by randomly deactivating a subset of neurons during training. Finally, a softmax layer is applied to produce a probability distribution over the output classes. The number of neurons in the final fully connected layer is set to match the number of anomaly classes present in the dataset, enabling the model to generate accurate and interpretable predictions. The output features are pooled and projected to class probabilities:

where and are the classifier weights and bias, and is the predicted class probability vector.

3.2. Datasets

SolarAttnNet is evaluated on three distinct datasets representing different imaging modalities—specifically, infrared (thermal) and visual (RGB) imagery—each of which captures distinct visual or thermal characteristics of solar panel anomalies:

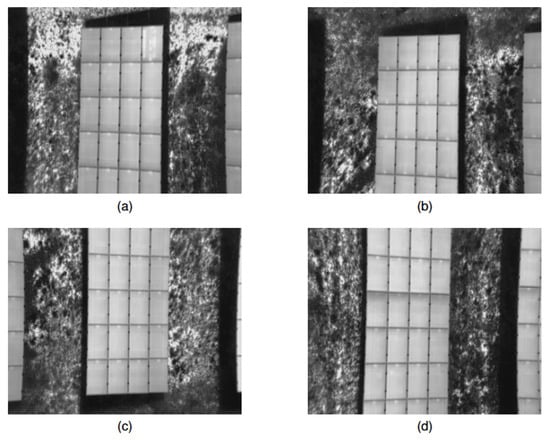

- PV systems-AD (Photovoltaic Systems Anomaly Detection) Dataset [35]. This dataset supports the development and evaluation of online, automatic anomaly detection methods for photovoltaic (PV) systems using thermography imaging combined with low-rank matrix decomposition techniques. It consists of raw aerial thermography video streams of PV panels, which have been processed using Transform Invariant Low-rank Textures (TILT) for perspective correction and background removal, as well as Robust Principal Component Analysis (RPCA) to distinguish between normal operational patterns and potential faults. To ensure full reproducibility, the PV Systems-AD dataset was reprocessed using a stratified sampling procedure. All preprocessing steps were executed using a fixed random seed of 42. The original dataset contains highly imbalanced class distributions and small validation splits, which vary across the literature. For this reason, and to ensure consistent class representation, we combined the original training and validation partitions and applied a stratified split into 70% training, 15% validation, and 15% testing. No images were removed except those flagged as corrupt by the dataset authors. This procedure prevents data leakage, maintains proportional representation of all anomaly types, and provides a standardized evaluation protocol for future comparison. Figure 2 shows sample images from this dataset.

Figure 2. Samples from the PV Systems-AD dataset (a–d).

Figure 2. Samples from the PV Systems-AD dataset (a–d). - InfraredSolarModules (RaptorMaps) Dataset [36]. This dataset provides 20,000 infrared images (24 × 40 pixels) with 12 defined classes, including 11 anomaly types and a no-anomaly class. Its real-world nature makes it valuable for IR-based detection research. The classes (11 anomaly types like ‘Cell’, ‘Cracking’, ‘Hot-Spot’, ‘Diode’, ‘Vegetation’, ‘Soiling’, and one ‘No-Anomaly’ class). This dataset provides real-world thermal imagery, essential for evaluating performance in detecting temperature-related anomalies. Figure 3 shows sample images from this dataset.

Figure 3. Samples from the Infrared Solar Module dataset (a–d).

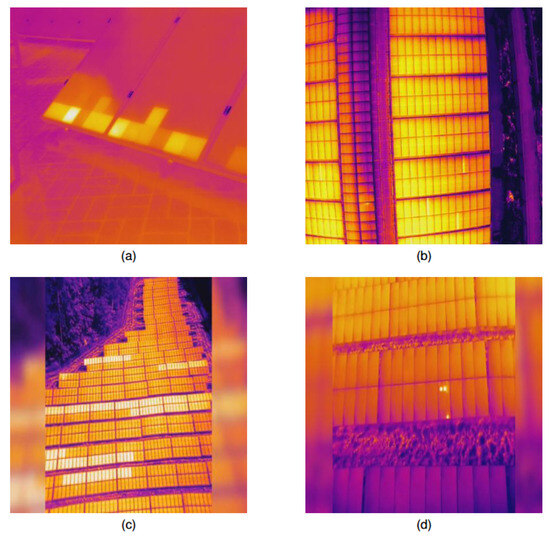

Figure 3. Samples from the Infrared Solar Module dataset (a–d). - Solar Panel Anomalies Dataset (Roboflow Universe) [37]. Platforms like Roboflow host various user-contributed datasets, including annotated solar panel images for object detection and classification tasks, such as the one selected for this study. It comprises 230 annotated visible-spectrum images, with classes such as ‘Diode anomaly’, ‘Hot Spots’, ‘Reverse polarity’, ‘Vegetation’, and ‘background’. Primarily focused on object detection but adaptable for classification. This dataset offers visible spectrum images, allowing evaluation of defects identifiable under normal lighting conditions and potentially more complex background scenes. Figure 4 shows sample images from this dataset.

Figure 4. Samples from the Solar Panel Anomalies Dataset (a–d).

Figure 4. Samples from the Solar Panel Anomalies Dataset (a–d).

These datasets were chosen to evaluate the performance of SolarAttnNet across different imaging modalities (infrared and visual) and anomaly types, providing a comprehensive assessment of its effectiveness for solar panel anomaly detection.

It is important to note that the imaging modalities used to obtain the datasets—thermal infrared imaging, visible-spectrum RGB imaging, and electroluminescence (EL) imaging—differ considerably in the type and visibility of anomalies they capture. Thermal images highlight temperature-related issues such as hot spots and diode failures, EL images reveal subsurface cell cracks and PID effects, while RGB images depict surface-level defects such as soiling and vegetation. These acquisition differences inherently influence the difficulty of the detection task. However, the proposed SolarAttnNet model demonstrates consistent performance across all modalities due to its dual attention design, which adaptively emphasizes informative channels and spatial regions regardless of the imaging source.

3.3. Implementation Details and Experimental Setup

SolarAttnNet is implemented in the MATLAB 2025a framework. Images were resized to 224 × 224 pixels and normalized using mean and standard deviation values computed from the training set. For training, data augmentation techniques were applied, including random horizontal and vertical flips, random rotations (±10 degrees), and color jitter (for RGB images only).

To address potential overfitting due to the limited size of the Roboflow (230 images) and PV Systems-AD datasets, we performed 5-fold stratified cross-validation in addition to the fixed train/validation/test splits. For each fold, the model was trained with the same augmentation and regularization settings, and performance metrics were aggregated across folds. This approach provides a more robust estimate of model performance and generalizability.

The model was trained using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.001, which was reduced by a factor of 0.1 every 7 epochs (step decay). Cross-entropy loss was used as the objective function, and training was performed for 25 epochs with a batch size of 32. Early stopping was employed based on validation loss to prevent overfitting.

Key hyperparameters, including the learning rate, batch size, and reduction ratio for the channel attention module, were selected through ablation studies (detailed in the following section).

The performance of SolarAttnNet is evaluated using standard classification metrics, including accuracy and F1-score. All dataset splits and model training procedures were performed using a fixed random seed of 42 to ensure full reproducibility. For each dataset, the data were randomly split into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets, ensuring class balance across all splits. SolarAttnNet and baseline models were trained using the same procedure. To address potential class imbalance in the datasets, we employed a weighted cross-entropy loss defined as:

where N is the batch size, K is the number of classes, is the ground-truth indicator (one-hot encoded), is the predicted probability for class k, and is the class weight, computed as:

where is the total number of training samples and is the number of samples in class k. The weights are normalized such that .

All experiments were repeated three times with different random seeds, and the mean and standard deviation of the performance metrics are reported.

To ensure a fair comparison, all models were trained from scratch without pre-training on external datasets. This approach isolates the contribution of architectural differences rather than the benefits of transfer learning. Additionally, experiments with pre-trained models were conducted to evaluate the potential benefits of transfer learning for solar panel anomaly detection.

All experiments were conducted on a workstation with an NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA. Tesla T4 GPUs. This configuration boasts a total of 24 cores and 384 GB of combined memory, providing ample resources for intensive computational tasks.

4. Experimentation Results

This section presents the results of the experimental evaluation conducted to assess the effectiveness of SolarAttnNet. It begins with ablation studies that analyze the individual contributions of the model’s key components. Following this, SolarAttnNet is systematically compared with state-of-the-art methods to benchmark its performance. A comprehensive analysis of the results is then provided, highlighting the model’s strengths and offering insights into its behavior across various anomaly detection scenarios.

4.1. Ablation Studies

Comprehensive ablation studies were conducted to evaluate the contribution of different components of SolarAttnNet. These studies help to understand which architectural elements are most important for solar panel anomaly detection and guide future research in this area.

4.1.1. Effect of Attention Mechanisms

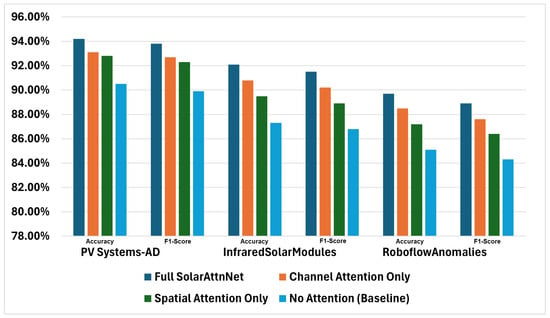

To evaluate the impact of the channel and spatial attention mechanisms, four variants of SolarAttnNet were trained and evaluated:

- Full SolarAttnNet, where the complete architecture with both channel and spatial attention.

- Channel Attention Only, where SolarAttnNet with only the channel attention module.

- Spatial Attention Only, in which SolarAttnNet with only the spatial attention module.

- No Attention (Baseline), where SolarAttnNet with both attention modules removed.

Table 1 presents the test accuracy and F1-score for each variant across the three datasets.

Table 1.

Performance Comparison of SolarAttnNet Variants Across All Datasets, Highlighting the Contribution of Attention Mechanisms.

The results demonstrate that both attention mechanisms contribute positively to model performance across all datasets. The full SolarAttnNet architecture consistently outperforms the variants with only one type of attention or no attention. Interestingly, the channel attention mechanism appears to provide a slightly larger performance boost than the spatial attention mechanism, suggesting that emphasizing informative feature channels is particularly important for solar panel anomaly detection. This result is further illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Performance of different SolarAttnNet variants across the three datasets.

To further understand the impact of attention mechanisms on different types of anomalies, the class-specific F1-scores for each variant on the PV Systems-AD dataset were analyzed, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Class-Specific F1-Scores for Different SolarAttnNet Variants on the PV Systems-AD Dataset.

The class-specific analysis reveals that attention mechanisms provide the largest performance improvement for subtle anomalies like cell cracks and Potential-Induced Degradation (PID), which are typically more challenging to detect. This suggests that attention mechanisms guide the model’s attention toward subtle features that distinguish these anomalies from normal conditions.

4.1.2. Hyperparameter Ablation

Ablation studies were also conducted to determine the effect of key hyperparameters on model performance. Table 3 presents the results of these studies using the PV Systems-AD dataset.

Table 3.

Impact of Hyperparameters on SolarAttnNet Performance (PV Systems-AD Dataset).

The ablation results indicate that a learning rate of 0.001, a batch size of 32, and a reduction ratio of 8 for the channel attention module yield the best performance on the PV Systems-AD dataset. Similar trends were observed for the other datasets, although the optimal hyperparameters varied slightly depending on the dataset characteristics.

4.1.3. Data Augmentation Ablation

To evaluate the impact of data augmentation on model performance, SolarAttnNet was trained with different augmentation strategies and their performance was compared on the test set. Table 4 presents the results of these experiments on the PV Systems-AD dataset.

Table 4.

Impact of Data Augmentation on SolarAttnNet Performance (PV Systems-AD Dataset).

The results demonstrate that data augmentation significantly improves model performance, with the combination of flips, rotations, and color jitter yielding the best results. This highlights the importance of data augmentation for training robust models, especially when working with limited datasets.

4.2. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

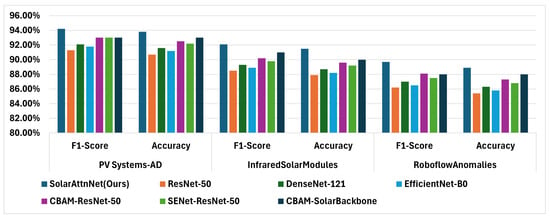

The SolarAttnNet is compared with several state-of-the-art methods for solar panel anomaly detection:

- ResNet-50: A deep residual network commonly used as a baseline for image classification tasks.

- DenseNet-121: A densely connected convolutional network that has shown strong performance on various computer vision tasks.

- EfficientNet-B0: A lightweight CNN architecture designed for efficient inference while maintaining high accuracy.

- CBAM-ResNet-50: ResNet-50 augmented with the Convolutional Block Attention Module, which integrates two distinct attention processes: (channel attention) and (spatial attention) in a different configuration than SolarAttnNet.

- SENet-ResNet-50: ResNet-50 augmented with Squeeze-and-Excitation blocks for channel attention.

To isolate the effect of the attention mechanism from the backbone architecture, we conducted an additional experiment in which we integrated the standard Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) [24] into the same VGG-style backbone used by SolarAttnNet. This model, referred to as CBAM-SolarBackbone, allows for a direct comparison between our proposed attention design and the original CBAM under identical backbone and training conditions. The results, included in Table 5 and Figure 6, demonstrate that SolarAttnNet consistently outperforms CBAM-SolarBackbone, indicating that the improvements stem not only from the backbone but also from our tailored attention configuration.

Table 5.

Comparison of SolarAttnNet with State-of-the-Art Methods.

Figure 6.

Comparison of SolarAttnNet with state-of-the-art methods across the three datasets.

As demonstrated in both Table 5 and Figure 6, SolarAttnNet outperforms all baseline methods across all datasets. The largest performance improvements are observed on the InfraredSolarModules dataset. This suggests that the attention mechanism design is particularly effective for thermal anomaly detection in real-world solar farm inspections.

To provide a more detailed comparison, the class-specific F1-scores for SolarAttnNet and the best-performing baseline method (CBAM-ResNet-50) on the PV Systems-AD dataset were analyzed, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Class-Specific F1-Scores for SolarAttnNet and CBAM-ResNet-50 on the PV Systems-AD Dataset.

A paired t-test conducted on the accuracy results from three runs confirmed that the performance improvement of SolarAttnNet over CBAM-ResNet-50 is statistically significant (p < 0.05). The class-specific analysis reveals that SolarAttnNet provides the largest performance improvements for subtle anomalies like cell cracks and PID, consistent with findings from the ablation studies. This further confirms that the implemented attention strategy shows a pronounced positive impact on overall model performance for detecting challenging anomalies that exhibit subtle features.

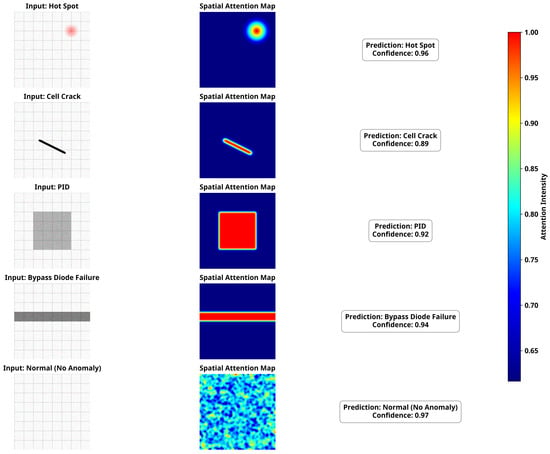

4.3. Qualitative Analysis

To provide insights into how SolarAttnNet focuses on relevant features for anomaly detection, attention maps generated by the channel and spatial attention modules were visualized. Figure 7 shows examples of input images, spatial attention maps, and the model’s predictions for different types of anomalies.

Figure 7.

Visualization of input images (left), spatial attention maps (middle), and model predictions (right) for different types of solar panel anomalies.

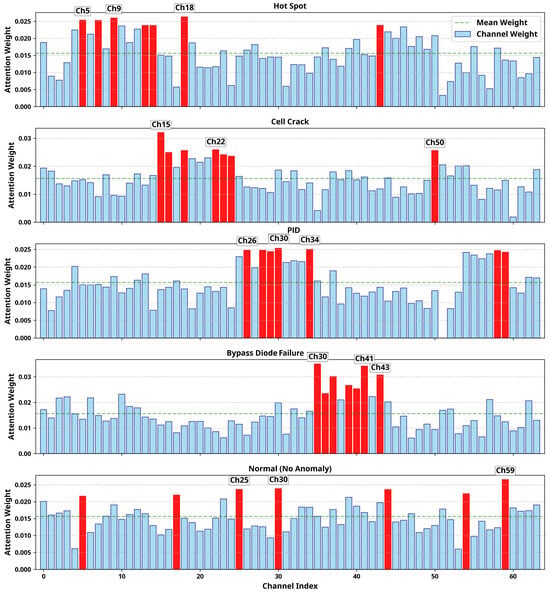

The visualizations in Figure 7 reveal that the spatial attention module effectively highlights regions corresponding to different anomaly types: for hot spots, attention is concentrated on localized high-temperature zones; for cell cracks, it follows linear or branching patterns; for PID, it often focuses on broader, diffuse regions of degradation. This demonstrates the model’s ability to adaptively localize anomaly-specific spatial signatures. Similarly, analysis of channel attention weights (Figure 8) shows that different anomaly types activate distinct sets of feature channels. For example, hot spots strongly activate channels sensitive to thermal intensity, while cracks and PID engage channels encoding texture and edge information. This indicates that the channel attention mechanism learns to prioritize feature detectors specialized for different anomaly characteristics, thereby enhancing discriminative power.

Figure 8.

Distribution of channel attention weights for different types of solar panel anomalies.

The analysis reveals that different anomaly types activate different feature channels, with some channels being consistently important across multiple anomaly types. This suggests that the channel attention mechanism helps the model learn specialized feature detectors for different types of anomalies.

4.4. Computational Efficiency

In addition to accuracy, computational efficiency is an important consideration for practical deployment of anomaly detection systems. Table 7 compares the computational requirements of SolarAttnNet with baseline methods.

Table 7.

Computational Efficiency Comparison.

The comparative analysis indicates that SolarAttnNet offers an effective compromise between computational complexity and predictive accuracy. While it has more parameters than EfficientNet-B0 and DenseNet-121, it offers significantly better accuracy while maintaining competitive inference times. This makes SolarAttnNet suitable for real-time anomaly detection in solar farm monitoring systems.

4.5. Discussion

The results obtained from the experiments highlight the strong capability of SolarAttnNet in detecting defects within solar panels across different imaging modalities and anomaly types.

Although anomaly detection performance can be influenced by the method used to obtain solar panel images, our results show that SolarAttnNet maintains strong performance across infrared, RGB, and electroluminescence datasets, despite their differing acquisition conditions and visual characteristics. This robustness stems from the model’s channel and spatial attention mechanisms, which allow it to selectively focus on the most relevant spectral features and spatial patterns present in each modality. Consequently, while the imaging method affects the visibility of specific anomaly types, the architecture of SolarAttnNet effectively mitigates modality-dependent variability.

The ablation studies confirm that channel and spatial attention mechanisms provide complementary benefits for solar panel anomaly detection. The channel attention mechanism helps the model focus on informative feature channels, while the spatial attention mechanism highlights regions of interest within the feature maps. SolarAttnNet shows the largest performance improvements for subtle anomalies like cell cracks and PID, which are typically more challenging to detect. This suggests that attention mechanisms help the model focus on the subtle features that distinguish these anomalies from normal conditions. The direct comparison between SolarAttnNet and CBAM-SolarBackbone—both using the same backbone architecture—confirms that the performance gains are attributable not only to the backbone but also to the tailored design of the attention modules, which are optimized for the spectral and spatial characteristics of solar panel anomalies. SolarAttnNet consistently outperforms baseline methods across all three datasets, demonstrating its ability to generalize across different imaging modalities and anomaly types. This is particularly important for practical deployment in diverse solar farm environments. Despite its sophisticated attention mechanisms, SolarAttnNet maintains competitive computational efficiency, making it suitable for real-time anomaly detection in solar farm monitoring systems. The visualization of attention maps provides insights into how SolarAttnNet focuses on relevant features for anomaly detection, enhancing the interpretability of the model’s decisions. This is particularly valuable for building trust in automated inspection systems. These findings highlight the potential of attention-enhanced CNNs for solar panel anomaly detection and provide a foundation for future research in this area.

SolarAttnNet leverages the strengths of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) in capturing local spatial features and spectral patterns, which are crucial in identifying fine-grained anomalies in hyperspectral imagery. By integrating channel and spatial attention mechanisms, the model enhances its focus on informative spectral bands and spatial regions without the heavy parameter load or data demands of ViTs. Furthermore, CNNs with attention are generally more lightweight, faster to train, and easier to deploy in real-time, resource-constrained environments such as field-deployed solar monitoring systems. This makes SolarAttnNet a practically viable and efficient alternative to ViT-based architectures for the anomaly detection task addressed in this study.

While SolarAttnNet demonstrates strong performance across all datasets, we acknowledge that the relatively small sizes of the Roboflow and PV Systems-AD datasets present a risk of overfitting, despite extensive data augmentation and cross-validation. The reported improvements should be interpreted in light of these dataset limitations. In future work, larger and more diverse datasets—potentially collected from operational solar farms—will be essential for further validating and refining the model. Transfer learning from pre-trained models on larger vision datasets may also help mitigate data scarcity and improve generalization.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This study introduced SolarAttnNet, a deep learning architecture that integrates and optimizes dual attention mechanisms for robust solar panel anomaly detection. Building upon known attention concepts, this work contributes a domain-adapted model validated across three public datasets covering infrared and visual modalities. Through systematic ablation studies, we quantify the individual and combined benefits of channel and spatial attention for solar panel defects, demonstrating significant gains on subtle anomalies like cell cracks and PID. SolarAttnNet also maintains computational efficiency, making it suitable for real-time monitoring in solar energy applications. The ablation studies quantitatively demonstrated the critical and complementary role of the attention mechanisms, with channel attention contributing an average 2.6% accuracy improvement and spatial attention contributing 2.3%. The model excelled precisely where it is most needed, achieving significant performance gains for challenging, subtle anomalies such as cell cracks and Potential-Induced Degradation (PID). Furthermore, its strong performance across different imaging modalities underscores its versatility and robustness for deployment in diverse inspection scenarios. Thus, this work provides a powerful, accurate, and efficient tool for the automated inspection of photovoltaic systems, contributing directly to improved energy yield, reduced operational costs, and the long-term reliability of renewable energy infrastructure.

Building on the foundation established in this study, several promising directions are identified for future research. A primary avenue involves the fusion of data from multiple sources beyond RGB and thermal imagery, such as electroluminescence (EL) imaging and electrical parameter time-series data; a cross-modal attention network could dynamically weigh the importance of each modality to achieve even higher detection accuracy and robustness. Furthermore, incorporating temporal dynamics using Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) or Transformers on sequential inspection data would enable a shift from diagnostic detection to the forecasting of defect progression, facilitating predictive maintenance. To address the challenge of collecting and labeling large datasets of rare defects, we plan to investigate unsupervised and self-supervised learning paradigms that can learn from vast amounts of unlabeled operational data. To enhance practicality, we will also work on optimizing SolarAttnNet for deployment on edge devices and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) using techniques like model quantization and pruning. Finally, integrating more advanced Explainable AI (XAI) techniques will be crucial to provide technicians with clear, human-understandable reasons for the model’s decisions, thereby building trust and enabling more precise remedial actions.

While the proposed SolarAttnNet model has been comprehensively evaluated on publicly available datasets derived from real solar installations—including aerial thermography, ground-based infrared, and visible-spectrum imagery—we acknowledge that direct validation in a live, continuously operating solar farm represents an important next step. The datasets used in this study reflect a wide range of real-world conditions, anomaly types, and imaging modalities, which supports the practical relevance of our approach. In future work, we plan to conduct field trials in operational solar plants to assess the model’s performance under dynamic environmental conditions, real-time data streams, and integration with existing monitoring systems. This will further validate its robustness and readiness for industrial deployment.

Author Contributions

Methodology, F.A.A. and M.R.Q.; data curation, M.R.Q.; investigation, M.R.Q.; conceptualization, M.R.Q. and F.A.A.; software, M.R.Q.; validation, F.A.A.; formal analysis, M.R.Q.; resources, M.R.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A.A.; writing—review and editing, F.A.A. and M.R.Q.; visualization, F.A.A. and M.R.Q.; supervision, M.R.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets used in this work are publicly accessible and can be obtained from the sources cited in [35,36,37].

Acknowledgments

The computational experiments for this study were carried out using the infrastructure provided by the Benefit Advanced AI and Computing Laboratory at the University of Bahrain (https://ailab.uob.edu.bh, accessed on 5 December 2025), with support from Benefit Bahrain Company (https://benefit.bh, accessed on 5 December 2025). The authors gratefully acknowledge the laboratory’s contribution in supplying the high-performance computing resources essential to the completion of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- International Energy Agency. Renewable Energy Market Update. 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewable-energy-market-update-june-2023 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Agency, I.E. Solar PV. 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/energy-system/renewables/solar-pv (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- REN21. Renewables 2023 Global Status Report; REN21 Secretariat: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Y.; Yu, T.; Yang, J. Photovoltaic Array Fault Diagnosis and Localization Method Based on Modulated Photocurrent and Machine Learning. Sensors 2025, 25, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, D.C.; Kurtz, S.R. Photovoltaic Degradation Rates—An Analytical Review. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 2013, 21, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qader, M.R. A Method for Analytical Voltage Sags Prediction in Complex Power Network. Recent Adv. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2018, 11, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeti, S.R.; Singh, S.N. A comprehensive study on different types of faults and detection techniques for solar photovoltaic system. Sol. Energy 2017, 158, 161–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalooshi, F.A.; Qader, M.R. Deep Learning Algorithm for Automatic Classification of Power Quality Disturbances. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, M.; Trabelsi, M.; Nounou, H.; Nounou, M. Deep learning-based fault diagnosis of photovoltaic systems: A comprehensive review and enhancement prospects. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 126286–126306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledmaoui, Y.; El Maghraoui, A.; El Aroussi, M.; Saadane, R. Enhanced Fault Detection in Photovoltaic Panels Using CNN-Based Classification with PyQt5 Implementation. Sensors 2024, 24, 7407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.W.; Chen, T.; Titrenko, S.; Su, P.; Mahmud, M. A Gradient Guided Architecture Coupled with Filter Fused Representations for Micro-Crack Detection in Photovoltaic Cell Surfaces. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 58950–58964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.U.; Khan, A.D.; Khan, K.; AlKhatib, S.A.K.; Khan, S.; Khan, M.Q.; Ullah, A. A Review of Degradation and Reliability Analysis of a Solar PV Module. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 185036–185056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saborido-Barba, N.; García-López, C.; Clavijo-Blanco, J.A.; Jiménez-Castañeda, R.; Álvarez Tey, G. Methodology for Calculating the Damaged Surface and Its Relationship with Power Loss in Photovoltaic Modules by Electroluminescence Inspection for Corrective Maintenance. Sensors 2024, 24, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meribout, M.; Kumar Tiwari, V.; Pablo Peña Herrera, J.; Najeeb Mahfoudh Awadh Baobaid, A. Solar panel inspection techniques and prospects. Measurement 2023, 209, 112466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruthviraj, U.; Kashyap, Y.; Baxevanaki, E.; Kosmopoulos, P. Solar photovoltaic hotspot inspection using unmanned aerial vehicle thermal images at a solar field in South India. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsanakas, J.A.; Ha, L.; Buerhop, C. Faults and infrared thermographic diagnosis in operating c-Si photovoltaic modules: A review of research and future challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, M.; Grimaccia, F.; Gonano, C.A.; Leva, S. Innovative automated control system for PV fields inspection and remote control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 7287–7296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartler, A.; Mauch, L.; Yang, B.; Reuter, M.; Stoicescu, L. Automated detection of solar cell defects with deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 European Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Rome, Italy, 3–7 September 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Pang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Liu, K. Solar cell surface defect inspection based on multispectral convolutional neural network. J. Intell. Manuf. 2018, 29, 1027–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Yang, Q.; Xiong, K.; Yan, W. Deep learning based automatic defect identification of photovoltaic module using electroluminescence images. Sol. Energy 2020, 201, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Yan, L.-C.; Yang, C.-S. LIRNet: A Lightweight Inception Residual Convolutional Network for Solar Panel Defect Classification. Energies 2023, 16, 2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M.W.; Li, G.; Jin, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhu, C.; Ahmad, A. Automatic detection of photovoltaic module defects in infrared images with isolated and compact deep learning model. Sol. Energy 2022, 224, 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2018, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; Ferrari, V., Hebert, M., Sminchisescu, C., Weiss, Y., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, X.; Liu, Z.; Wu, C.Q.; Hou, A.; Yin, X.; Chen, Z. MFGAN: Multimodal Fusion for Industrial Anomaly Detection Using Attention-Based Autoencoder and Generative Adversarial Network. Sensors 2024, 24, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Blanton, H.; Bessinger, Z.; Jacobs, N. Inconsistent performance of deep learning models on mammogram classification. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2021, 18, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, L. Automatic photovoltaic module defect detection using a convolutional neural network. Energy 2019, 189, 116225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Chen, G.; Zhao, L. Defect detection of photovoltaic modules based on improved VarifocalNet. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Sun, B.; Zhang, W. Infrared-image-based fault diagnosis of photovoltaic modules using deep learning. Renew. Energy 2020, 155, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Park, Y.; Kim, M. Aerial infrared inspection of photovoltaic modules using deep neural networks. Energies 2022, 15, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Vienna, Austria, 4 May 2021; 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yuan, G.; Wen, Y.; Hu, J.; Evangelidis, G.; Tulyakov, S.; Wang, Y.; Ren, J. EfficientFormer: Vision Transformers at MobileNet speed. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 350–367. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Xiao, B.; Codella, N.; Liu, M.; Dai, X.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, L. CvT: Introducing Convolutions to Vision Transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10 October 2021; 2021; pp. 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, A.; Balasundaram, A.; Kakarla, L.S.; Murugan, N. Deep Learning-Based Detection and Segmentation of Damage in Solar Panels. Automation 2024, 5, 128–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Paynabar, K.; Pacella, M. Online automatic anomaly detection for photovoltaic systems using thermography imaging and low rank matrix decomposition. J. Qual. Technol. 2022, 54, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millendorf, M.; Obropta, E.; Vadhavkar, N. Infrared solar module dataset for anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 26–30 April 2020; Available online: https://ai4earthscience.github.io/iclr-2020-workshop/papers/ai4earth22.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Ciaglia, F.; Zuppichini, F.S.; Guerrie, P.; McQuade, M.; Solawetz, J. Roboflow 100: A rich, multi-domain object detection benchmark. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.13523. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).