Abstract

This study presents a scenario-based modeling framework to evaluate potential decarbonization pathways for Portugal’s road transport sector. The model simulates the evolution of a light-duty vehicle (LDV) fleet under varying degrees of electrification and biofuel integration, accounting for energy consumption, CO2 emissions and market shares of alternative propulsion technologies. Coupled with projected energy mix trajectories, the framework estimates final energy demand and well-to-wheel (WTW) emissions for each scenario, benchmarking outcomes against national and European climate targets. A key structural limitation identified is the long vehicle survival rate—averaging 14 years—which constrains fleet renewal and delays the transition to full electrification. Diesel-powered light commercial vehicles exhibit even slower replacement dynamics, rendering the Portuguese targets of full electrification by 2030 highly improbable without targeted scrappage and incentive programs. Scenario analysis indicates that even with accelerated electric vehicle (EV) uptake, battery electric vehicles (BEVs) would comprise only 12% of the fleet by 2030 and 77% by 2050. Electrification scenario raises electricity demand fortyfold by 2050, stressing generation and infrastructure. Scenarios that consider diversification of energy sources reduce this strain but require triple electricity for large-scale green hydrogen and synthetic fuel production.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the global surge in energy demand has intensified concerns over fossil fuel reliance and associated greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The transport sector is particularly critical, with approximately 91% of its final energy demand met by petroleum-based products [1]. In 2022, transport represented 31% of Europe’s final energy consumption, ranking as the highest among all sectors [1]. In Portugal, the sector remains similarly dependent, with petroleum-based diesel and gasoline, covering 90% of transport energy in 2019 and GHG emissions rising 10% between 2014 and 2019 [2].

To mitigate CO2 emissions, biofuels and synthetic fuels have emerged as viable alternatives to fossil gasoline and diesel. In Portugal, biofuel incorporation is primarily focused on diesel substitutes, particularly biodiesel. According to Decree-Law No. 84/2022, fuel suppliers must ensure a minimum incorporation of 11.5% low-carbon fuels (energy basis), rising to 13% by 2025 [3]. Biodiesel, suitable for compression-ignition engines, is produced through the transesterification of oils and fats into long-chain fatty acid methyl esters (FAME). The main feedstock consists of used cooking oils (UCOs)—mainly of vegetable origin but sometimes containing animal fats—representing over 50% of the input mix, increasing from 57% in 2018–2019 to 61% in 2020 [4]. Besides serving as a renewable substitute, biodiesel is often blended with fossil diesel to improve lubricity and cetane number [4]. An advanced alternative is hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO), also known as renewable diesel or HEFAs (Hydrotreated Esters and Fatty Acids). Produced through hydroprocessing, HVO offers better cold-flow properties, oxidation stability, and lower NOₓ emissions, while maintaining full compatibility with conventional diesel engines. It can be produced in dedicated units or retrofitted petroleum refineries [4].

For gasoline, alternatives include bioethanol and ETBE (Ethyl Tertiary Butyl Ether), typically blended at 5–20% and 5–15% v/v, respectively, without requiring engine modification [5]. Given these blending limitations, synthetic gasoline has gained attention. A notable example is Porsche’s Chilean pilot plant, which synthesizes fuel from captured CO2 and green hydrogen (H2) via methanol (CH3OH) intermediates through the methanol-to-gasoline (MtG) process [6].

Besides conventional internal combustion vehicles, electric propulsion technologies have gained prominence, particularly battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs), which combine electric motors with combustion engines in series, parallel or full hybrid configurations. More recently, hydrogen fuel-cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) have emerged, using electric motors powered by the reaction of compressed hydrogen and oxygen in a fuel cell, emitting only water (H2O). Although FCEVs are often labeled “zero-emission,” this depends on the hydrogen source. Only green hydrogen—produced via electrolysis using renewable electricity—ensures a low-carbon lifecycle. However, as of 2021, global hydrogen production remained predominantly fossil-based: 47% from natural gas, 27% from coal, 22% from oil, and merely 4% from electrolysis [7,8,9].

To tackle emissions across all vehicle categories, the European Commission proposed the Euro 7 regulation, succeeding Euro 6 with a technology- and fuel-neutral approach. Unlike its predecessor, Euro 7 sets uniform pollutant limits for all propulsion systems—gasoline, diesel, hybrid, and electric—ensuring consistent emission standards across technologies [10]. In parallel, the European Union (EU) has reinforced its climate and energy policy framework to reduce transport-related greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. Regulation (EU) 2023/851 [11], adopted on 19 April 2023, amends Regulation (EU) 2019/631 [12], strengthening CO2 performance standards for new passenger cars and light commercial vehicles. It mandates a 55% GHG reduction by 2030 (relative to 1990 levels) and climate neutrality by 2050. From 2035, the fleet-wide CO2 target for new vehicles will be zero g/km, effectively banning the sale of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles [13].

In 2023, average CO2 emissions from newly registered cars in the EU-27 were approximately 108 g/km, 2 g/km lower than in 2022. The values varied by country: Spain exceeded the average (117 g/km), while Sweden achieved 62 g/km. Italy was the only major market to exceed WLTP CO2 emission target of 119 g/km. Portugal’s fleet average CO2 emission remained below both the EU average and target [14,15]. CO2 emissions in ICE vehicles correlate directly with fuel consumption—about 26.5 g/km per L/100 km for diesel and 23–24 g/km for gasoline, depending on fuel composition [16]. Market dynamics also shape fleet emissions: diesel’s sales share fell from ~28% in 2020 to 13.6% in 2023, while HEVs rose to 25.8%, BEVs to 14.6%, and PHEVs to ~8% of new car sales [15]. In Portugal, BEVs reached 17.5% of new sales (January–August 2024), second only to gasoline vehicles (37.2%). In the same period within the EU, HEVs and gasoline had similar sale shares (29.7% and 34.9%, respectively). BEVs only represented 12.6% [17].

While BEVs emit no tailpipe GHGs, their lifecycle emissions depend on the electricity mix—renewables supplied ~85% of Portugal’s 46.31 TWh generation in 2024 [18]. Despite operational advantages, battery production remains energy- and resource-intensive, accounting for roughly 50% higher manufacturing emissions than conventional cars [19,20]. Nonetheless, a BEV operating under real-world conditions can already achieve a 65% GHG reduction compared to a gasoline counterpart and by 2030, BEV lifecycle GHGs are expected to fall by up to 76% due to cleaner power grids and improved battery efficiency, assuming a vehicle lifetime of 14 years and 200,000 km. FCEVs exhibit comparable production-phase impacts, mainly from carbon fiber-reinforced plastics (CFRPs) used in hydrogen storage [21,22]. Electrified powertrains—HEV (28%), PHEV (61%), BEV (76%) and FCEV (56%)—also present GHG lifecycle advantages over ICE vehicles in the 2030 timeframe [21]. Similar results can be found in an ICCT report, although, enhancing the impact of H2 pathway in the FCEV life-cycle GHG emissions: if H2 is obtained from renewable sources, life cycle GHG emissions are similar to those from BEVs; however, if H2 is obtained from natural gas, GHG emissions are comparable to those from HEVs [23,24].

Also, for light-duty vehicles, the JEC Well-to-Wheel (WTW) [25] analysis found that most alternative fuels outperform conventional gasoline and diesel in energy and emission efficiency. BEVs and FCEVs powered by renewable electricity or hydrogen achieve low g CO2/km values, similar to biodiesel. HEVs reduce TTW energy consumption (MJ/km) by up to 27%, with greater gains in gasoline engines than diesel (only up to 21%), while PHEVs can provide an up to ~40% reduction in WTW gCO2/km. The JEC study also highlighted that no single fuel pathway offers a large-scale, short-term decarbonization solution. Instead, meaningful GHG reductions require a diversified mix of technologies and fuels, including renewables, hydrogen, and biofuels [25]. Similar conclusions were obtained by a Ricardo study prepared for Concawe [26,27], where low-carbon fuels scenarios play a central role, with bio-based and synthetic components reaching 68% of transport energy by 2050. An alternative ERTRAC [28] scenario envisions a more diverse fleet: BEVs and PHEVs comprise 64% of European light-duty vehicles, with the remainder split between HEVs and ICEVs. Despite differing strategies, all three scenarios achieve ~85% GHG reductions by 2050.

The ICCT [29] assessed EU CO2 targets under four market scenarios: until 2025, all align with a “Moderate Ambition” pathway; thereafter, reliance on PHEVs and low-carbon fuels is expected to meet the 2030 WLTP-based 70% CO2 target. However, this combination fails to meet 2035 goals under the same pathway. An “Adopted Policies” scenario achieves compliance but with higher cost. The study cautions that CO2 credit mechanisms for synthetic fuels may unintentionally extend to biofuels which—despite being cheaper—carry greater environmental and climate risks.

According to the IEA’s Net Zero by 2050 roadmap [30], the global economy is projected to grow 40% by 2030 while reducing energy consumption by 7%. This requires a 4% annual improvement in energy efficiency, nearly triple the historical rate [31]. Supported by clean electricity expansion, EV sales are expected to rise from 5% to over 60% of global car sales by 2030. By 2050, electricity should supply 74% of road transport energy, with hydrogen vehicles contributing ~16% [30].

Portugal has committed to achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, as established in the Roadmap for Carbon Neutrality 2050 (RNC2050) [32]. This strategic plan defines the main decarbonization pathways and policy measures required to meet long-term emission goals, identifying fleet electrification as the core strategy, complemented by hydrogen for heavy-duty transport. For light-duty vehicles (LDVs), electric mobility is projected to represent 36% of the total demand by 2030, reaching full electrification by 2050. Combined with a growing share of renewable electricity, these measures are expected to reduce GHG emissions by 43% by 2030 and 98% by 2050 relative to baseline levels.

The National Energy and Climate Plan (PNEC), initially launched in 2020 and revised in 2024 [33,34] under the EU Governance Regulation for Energy and Climate Action, sets more ambitious intermediate targets. The updated plan aims for 80% renewable electricity generation by 2026—four years ahead of the previous schedule—positioning Portugal to achieve climate neutrality by 2045. The revised GHG reduction target was raised to 55% by 2030 (relative to 2005 levels). Within the transport sector, the PNEC prioritizes sustainable mobility and energy decarbonization through public transport expansion, electrification, and the use of renewable non-biological fuels, particularly green hydrogen.

In this context, the present study develops and applies a scenario-based modeling framework to assess potential decarbonization pathways for Portugal’s road transport sector. The model simulates the evolution of the LDV fleet under different combinations of electric mobility adoption and biofuel integration, incorporating parameters such as energy consumption, CO2 emissions, and market shares of alternative propulsion technologies. Coupled with projected vehicle sales trends and energy mix evolution, the model estimates final energy demand and well-to-wheel (WTW) CO2 emissions for each scenario. The results are then benchmarked against PNEC2030 and RNC2050 targets, enabling an assessment of the coherence, feasibility, and effectiveness of national decarbonization strategies within the broader European policy framework.

2. Materials and Methods

The model divides the input variables essentially into 3 large groups: Fleet forecast (Section 2.1); Vehicle propulsion systems (Section 2.2); and Energy source (Section 2.3). Three different scenarios were addressed by adjusting parameters that impact the vehicle sales forecasts and introduction of energy sources, as well as their production pathways, with the aim of achieving total energy consumption and associated CO2 emissions.

2.1. Fleet Forecast

Modeling the yearly evolution of the Portuguese vehicle fleet requires defining vehicle sales trajectories consistent with demographic and economic trends. Historical sales data for all vehicle categories were obtained from the Portuguese Automobile Association (ACAP) [35], serving as the basis for calibration of future growth rates. To preserve a relatively stable motorization rate (number of vehicles per 1000 inhabitants), the annual sales growth was adjusted to yield an average increase of 0.4% per year over the next 25 years. The motorization rate was modeled using a normalized sigmoid function that captures the typical evolution of an automotive market—from its initial growth phase through expansion to eventual market saturation [36,37,38].

A central assumption of the modeling framework is that the Portuguese automotive market is nearing saturation. Although the motorization rate has shown a modest upward trend over the past decade [39], demographic projections indicate a population decline of approximately 8% relative to current levels by mid-century [40]. This demographic contraction constrains potential fleet expansion, implying that future vehicle growth will mainly depend on replacement dynamics rather than net additions.

In addition to market growth rates, the model incorporates vehicle survival curves, which describe the probability of a vehicle remaining in service over time. Vehicle survival reflects the likelihood of failure before the expected lifespan, total loss after accidents, or replacement by a new or used vehicle. Consequently, annual survival curves quantify the number of vehicles withdrawn from circulation after k years [36]. To represent this behavior, a Weibull probability distribution was employed, as expressed in Equation (1) [36], where represents the vehicle age, is the predicted vehicle lifetime and is a shape parameter, defined as 35 for passenger vehicles and 40 for light-duty vans.

The vehicles currently in circulation were divided by age category. By consulting the ACEA report Vehicles on European Roads [41] and the National Inventory Report produced by the Portuguese Environment Agency (APA) [42] that defines the national fleet in 2021 by technology type and, more relevant in this case, by EURO standard, it was possible to divide the current nearly 4,500,000 vehicles into age categories. Table 1 summarizes the fleet data.

Table 1.

Distribution of the fleet of passenger cars and light-duty vans over 10 years old in 2021 by EURO standard (adapted from [42]).

The distribution of passenger and commercial vehicle fleets by propulsion type is mostly dominated by diesel (58.5% in passenger vehicles and 99.5% in LDVans), gasoline (36.5% in passenger vehicles and 0.2% in LDVans), HEVs (1.6% in passenger vehicles), LPG or natural gas, PHEVs (1% in passenger vehicles), and BEVs (0.9% in passenger vehicles and 0.2% in LDVans). There were no registered H2 vehicles.

Based on the defined survival rate, the current vehicle fleet, and the projected annual sales growth rate, a transition matrix can be established to estimate the number of newly circulating vehicles, disaggregated by propulsion technology, for all vehicles sold from 2023 onwards (Table 2). The total number of vehicles circulating in a given year ( is provided by Equation (2), where is the total number of new vehicles sold in year , represents all vehicles sold since 2023 and still circulating in year and includes all existing vehicles pre-2023 that are still circulating in year . Equation (1) plays an important role in determining the surviving vehicles to calculate and by indicating the probability of a vehicle still being part of the fleet.

Table 2.

Calculation matrix for vehicles in circulation.

According to data from the European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) [43], battery electric vehicles (BEVs) became the second most sold vehicle type in 2023, representing 18.2% of total sales. Meanwhile, internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) continued to decline, with their diesel share dropping from 17.8% in 2022 to 12% in 2023, and gasoline falling from 42% to 36%. Among hybrids, plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) grew notably, partially offsetting the decrease in conventional hybrids (HEVs). For light commercial vehicles, diesel remained predominant in 2023, though its share decreased from 95.1% to 90.8%. Electrically chargeable vans (BEVs + PHEVs) expanded rapidly, doubling their market share from 4.3% to 8.6%. Based on registration data [44], BEVs account for roughly 8% of this share, while PHEVs represent only 0.6%.

Future sales evolution until 2050 will depend on the scenario assumptions defined in Section 2.4. Vehicle market dynamics were modeled using a logistic growth function (Equation (3)) representing the saturation behavior of the Portuguese fleet. The propulsion technology market share in year depends on the maximum ( and minimum () share considered, the technology growth rate , the growth factor , considering the initial year when a given technology is introduced , and the studied year . These parameters are specific for each propulsion technology and change according to the scenarios studied. The number of vehicles sold each year for each vehicle technology is obtained from applying Equation (3) to in Equation (2) (the total number of new vehicles sold in year ).

2.2. Vehicle Propulsion Systems

For the annual mileage for each technology, data from the National Inventory report produced by the APA [42] were consulted. This document, in addition to the total number of vehicles in circulation in 2021 (Table 1), also provides data on annual vehicle km for combustion vehicles, organized by the corresponding Euro standard. Taking into account the number of vehicles of each technology and the vehicle km associated with each of them, it is then possible to obtain an average value of kilometers traveled per year () for each propulsion system j (Equation (4)).

where is the type of technology (Diesel, gasoline, HEV, PHEV, LPG, BEV, H2), is the number of vehicles of a given technology and is the annual vehicle km. There are some technologies for which the APA report [42] insufficiently defines the annual kilometers so a different approach was adopted, especially for PHEVs, FCEVs, and BEVs. Starting with BEVs, a 2021 study by Nissan concluded that, in Europe, BEVs traveled only 600 km more than combustion vehicles on average [45]. Given the difference in kilometers between gasoline and diesel vehicles, a weighted average value was considered for the annual mileage of BEVs to account for the number and mileage of diesel and gasoline vehicles.

For plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), the same annual mileage as for conventional hybrids (HEVs) was assumed. In addition to these mainstream technologies, hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs) were also considered, although they remain at an early stage of market development. Due to the limited availability of operational data and the inherent lack of range constraints, FCEVs were assumed to exhibit annual mileage comparable to diesel vehicles, which typically cover the greatest distances per year. This assumption prevents any artificial limitation on this emerging technology.

After estimating the annual mileage for each propulsion technology, certain inconsistencies were identified. On average, diesel vehicles travel approximately 40% more kilometers per year than gasoline vehicles, a difference that can be attributed to their predominant use in professional and commercial applications, where annual utilization rates are typically higher. Since the APA dataset [42] does not distinguish between private and commercial vehicle usage, a uniform average value of 9263 km per year was adopted for all propulsion types to ensure consistency across the model.

Table 3 shows the values considered for each technology, with the values in bold resulting from the hypotheses considered and the remaining directly taken from [42].

Table 3.

Average annual mileage adopted for each type of technology (adapted from [42]).

Another relevant aspect is the decline in vehicle mileage with age. This behavior was modeled using an exponential decay function, as proposed by the U.S. Department of Transportation [46], where the annual vehicle kilometers traveled () for a vehicle with age are expressed as a function of vehicle age according to Equation (5).

When , data for vehicle technology is obtained from Table 3.

The total annual energy consumption based on energy consumed per km (MJ/km) is intrinsically linked to CO2 emissions for combustion vehicles, which are also available in the APA report (CO2/km) [42]. Diesel emits approximately 2650 g CO2/L, while gasoline vehicles have an emission factor of approximately 2300–2400 g CO2/L, depending on the exact fuel composition. These factors can be further validated using the UNECE [47], allowing to calculate the consumption in L/100 km or MJ/km by multiplying it by the correspondent fuel density and Lower Heating Value (LHV). The emission factor adopted for LPG vehicles was 1616 g CO2/L [48]. The HEV data was obtained from the APA report (CO2/km) [42] and it was assumed that these vehicles use gasoline internal combustion engines. The energy consumption was then calculated similarly to gasoline vehicles.

For battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), the absence of tailpipe emissions necessitates an energy-based approach independent of CO2-to-energy conversion factors. For BEVs, 2023 sales data were analyzed, selecting the ten best-selling European models [49] and real-world energy consumption was obtained from the Spritmonitor database [50]. The weighted average resulted in 0.69 MJ/km.

For PHEVs, data were gathered for the most popular models with internal combustion engine (ICEV) counterparts. Comparing the average gasoline energy consumption revealed that PHEVs use approximately 52% less fuel than the equivalent ICE vehicles. As Spritmonitor [50] does not report electricity use, it was assumed that PHEV electric energy consumption per kilometer is comparable to BEVs—justified by similar average weights, as the best-selling PHEVs are typically SUVs.

For fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), the Toyota Mirai was used as reference. According to Spritmonitor [50], its hydrogen consumption is approximately 0.99 kg H2/100 km (converted to MJ/km from H2 LHVs).

National Inventory report data [42] demonstrates that commercial vehicles typically consume more energy per kilometer, a phenomenon that may be associated with these vehicles being typically larger and used for light goods transport. Considering that the average energy use of a passenger ICEV (diesel) is 2.62 MJ/km and a LDVan ICEV (diesel) is 3.16 MJ/km, a ratio of 1.2 is obtained, indicating that diesel LDVan ICEVs use 20% more energy than LDVs. Due to the low representation of other technologies in this fleet, it was assumed that the consumption of BEVs, HEVs, PHEVs, and FCEVs would have a similar relationship to that of ICEVs (diesel) for passenger and commercial vehicles.

Table 4 presents the energy consumption values adopted for each propulsion technology. A distinction is made between EURO 6 vehicle consumption and the overall fleet average to more accurately represent the performance of new vehicles entering the fleet. This differentiation ensures that recently registered vehicles—typically more efficient due to technological improvements and stricter emission standards—are properly characterized. Cells left blank correspond to technologies either absent from the market or not covered under the EURO 6 standard, such as battery electric vehicles (BEVs). In these cases, it was assumed that the energy consumption of new vehicles equals the average consumption for that technology class. This approach provides a consistent baseline across propulsion types, ensuring comparability in the energy modeling framework while maintaining alignment with available market and regulatory data.

Table 4.

Energy consumption per km by vehicle type (adapted from [42]).

Finally, to calculate the total energy consumed (in MJ) in year , simply multiply the consumption per km in MJ/km (available in Table 4 for each propulsion system ) by the number of vehicles and the average number of km traveled per year , according to Equation (6).

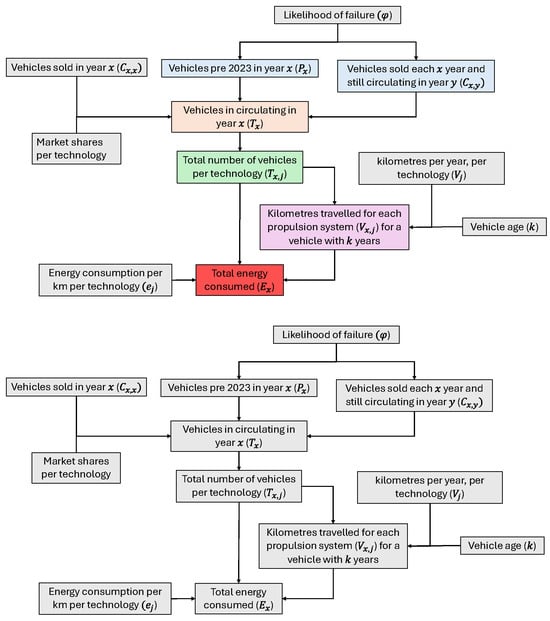

Figure 1 presents a block diagram with the data flow used within this work, including the main variables used and their relationships.

Figure 1.

Block diagram of data for total energy calculation.

To estimate total fleet energy consumption, an average vehicle age was defined. The Portuguese vehicle fleet reached an average age of 13.6 years in 2022 [15], a figure that has been steadily rising over the past two decades; thus, 14 years was assumed for 2023. Fleet-specific CO2 emissions (g/km) were derived from the APA National Inventory Report [42], consistent with the fuel consumption data, as summarized in Table 5. For plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEVs), emissions were assumed to equal 52% of those from gasoline ICEVs based on the previously described assumptions. For commercial vehicles, emissions were estimated as 1.2 times higher than those of passenger cars, reflecting their greater mass and fuel demand. Values in bold were calculated based on the assumptions described.

Table 5.

CO2 emissions/km by vehicle type (adapted from [42]).

The total CO2 emissions in year in a Tank-to-Wheel (TTW) perspective are obtained from Equation (7) using information from CO2 emissions per km (available in Table 5), the number of vehicles and the average number of km traveled per year . The data flow is similar to the one presented in Figure 1, just using CO2 emission factors instead of energy factors.

2.3. Energy Source

The well-to-wheel (WTW) assessment requires accounting for variables associated with the energy source of each propulsion system. Beyond tailpipe (TTW) emissions from combustion vehicles, it is necessary to include the well-to-tank (WTT) emissions arising from the conversion of primary energy into final energy. To quantify this, emission factors were defined to relate the energy produced (MJ) to the corresponding CO2 emissions (g CO2), as presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

CO2 emissions g/MJ by vehicle type (adapted from [25]).

Most of these factors were directly derived from a JEC study for the European Commission [25], which analyzed the emission intensities within the current EU energy mix. However, special consideration was given to electricity, synthetic fuels, and hydrogen, as their emission factors depend strongly on the production pathway.

For electricity, the emission factor is highly sensitive to the national energy mix. To ensure representativeness for Portugal, data were obtained from the European Environment Agency, which provides country-specific electricity emission factors across the EU [51]. This factor is the only one assumed to vary over time, progressively declining to zero (0 g CO2/MJ) in line with carbon-neutrality targets. The rate of reduction will depend on the assumptions associated with each scenario defined later in this study.

Regarding synthetic fuels and hydrogen, it was assumed that both are produced exclusively using renewable electricity, as only this condition ensures alignment with carbon-neutral production pathways. In the specific case of synthetic fuels, due to the early stage of technological development, the production process was modeled following the Porsche eFuel methodology [6,52] and information from Concawe [53].

The WTW CO2 emissions can be calculated from Equation (8) for each propulsion system considering the TTW CO2 emissions , the TTW energy used and the respective CO2 emission factor ( in g/MJ) associated with the energy production stage of each energy vector (obtained from Table 6).

The annual WTW CO2 emissions is obtained by summing the TTW and WTT impacts of each propulsion technology.

2.4. Scenario Definition

2.4.1. Scenario 1: Technological Replacement and Transition to Electrification

Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) represent the cornerstone of the decarbonization strategy to meet increasingly stringent emission targets and achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. BEV market penetration is projected to expand rapidly, reaching 52% of light-duty and 70% of commercial vehicles by 2030, and 85% and 80%, respectively, by 2050. The combined effects of limited alternative fuel deployment and higher taxation on fossil fuels drive the gradual phase-out of Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles (ICEVs) and hybrid technologies (PHEVs, HEVs), with combustion-based vehicle sales ceasing after 2040.

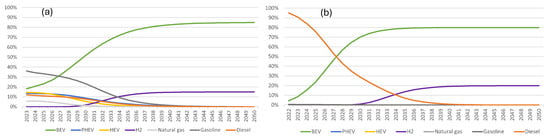

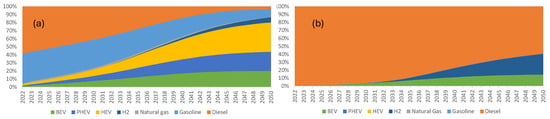

Following the RNC2050 [32] and PNEC [34] pathways, commercial fleet electrification accelerates significantly, while Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles (FCEVs) emerge after 2030, supported by green hydrogen production. By 2050, FCEVs are expected to represent 15% of the passenger and 20% of the commercial vehicle market as they are favored for their range and payload advantages. These assumptions lead to the following coefficients for Equation (3). Regarding passenger vehicles: for Natural Gas, , and ; for HEVs, , and ; for PHEVs, , and ; for BEVs, , and and; for Hydrogen, , and ; and for gasoline and diesel, the remaining share is divided 75–25% following the trend of last year’s sales. For light-duty vans: for Natural Gas, , and ; for HEVs, , and ; for PHEVs, , and ; for BEVs, , and and; for Hydrogen, , and ; and for gasoline and diesel, the remaining share is divided 0.5–99.5% following the trend of last year’s sales. These parameters yield the market evolution in Figure 2, where full renewable electricity generation is achieved by 2040, surpassing the RNC2050 targets [32].

Figure 2.

Scenario 1 market share (%) evolution between 2023 and 2050 of: (a) light-duty passenger vehicles; (b) light-duty vans.

2.4.2. Scenario 2: Transition to Alternative Energy Sources (Diesel and Gasoline)

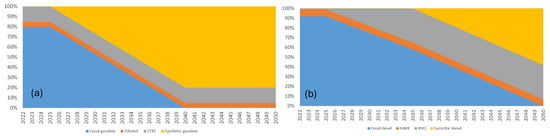

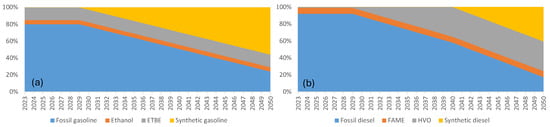

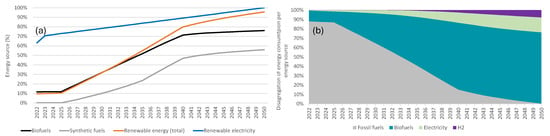

In this scenario, carbon neutrality is achieved primarily through the decarbonization of energy sources rather than a complete shift in propulsion technologies. The strategy relies on the progressive substitution of fossil fuels—diesel and gasoline—with synthetic and bio-based alternatives. The transition begins in 2026, with synthetic gasoline gradually replacing fossil gasoline at an average rate of 5% per year, reaching 27% by 2030 and 80% by 2040. The remaining 20% corresponds to the current E5 gasoline blend, composed of ethanol (5%) and ETBE (15%), which is assumed constant over time due to engine compatibility constraints [5]. Figure 3a presents the market evolution of fossil gasoline and substitutes.

Figure 3.

Scenario 2 evolution of fuel type (% of energy in the fleet) between 2023 and 2050 of: (a) Fossil gasoline and substitutes; (b) Fossil diesel and substitutes.

For diesel, the initial focus is on Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil (HVO), given its high compatibility with fossil diesel [16]. FAME blending remains limited to 7% [4], while the HVO share increases by about 4% per year, reaching 35% by 2035. Beyond this point, feedstock limitations and the expansion of green hydrogen production drive the gradual substitution of fossil diesel with synthetic diesel, completing the phase-out of fossil fuels by 2050 (Figure 3b).

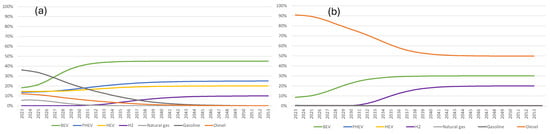

In this scenario, the widespread adoption of biofuels and synthetic fuels substantially reduces the reliance on plug-in electric vehicles (PHEVs and BEVs) to achieve carbon neutrality. Figure 4a presents the light-duty passenger share market. These assumptions lead to the following coefficients for Equation (3). Regarding passenger vehicles: for Natural Gas, , and ; for HEVs, , and ; for PHEVs, , and ; for BEVs, , and and; for Hydrogen, , and ; and for gasoline and diesel, the remaining share is divided 75–25% following the trend of last year’s sales. For light-duty vans: for Natural Gas, , and ; for HEVs, , and ; for PHEVs, , and ; for BEVs, , and and; for Hydrogen, , and ; and for gasoline and diesel, the remaining share is divided 0.5–99.5% following the trend of last year’s sales.

Figure 4.

Scenario 2 market share (%) evolution between 2023 and 2050 of: (a) light-duty passenger vehicles; (b) light-duty vans.

The BEV market rapidly saturates, reaching a 20% share of passenger light-duty vehicles by 2030, while PHEVs expand to 25% by 2040, coinciding with the phase-out of fossil gasoline. Hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) emerge as the fastest-growing technology, benefiting from higher efficiency and full compatibility with carbon-neutral fuels. Their market share rises to 26% in 2030 and 40% by 2050. The phase-out of ICEVs becomes unnecessary, as they retain a residual 5% share by 2050.

Fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) experience delayed uptake due to the prioritization of hydrogen for synthetic fuel production between 2030–2035, reaching only 10% in passenger vehicles but up to 40% in commercial fleets, where they help mitigate NOₓ and particulate emissions. Despite these shifts, diesel remains dominant in commercial transport (45% in 2050, as seen in Figure 4b, and 100% renewable electricity is achieved only by 2050 as no additional effort is made to obtain this goal earlier).

2.4.3. Scenario 3: Technology Replacement and Transition to Alternative Energy Sources

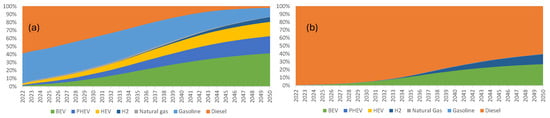

An intermediate scenario was defined between the two previously considered, which were based on optimistic assumptions regarding the rapid adoption of BEVs (Scenario 1) and biofuels (Scenario 2).

In this new scenario, although synthetic fuels remain part of the strategy, their introduction is delayed until 2030, aligning with current plans for hydrogen production as outlined in RNC2050 [32]. Until then, HVO is gradually introduced as a partial substitute for fossil diesel, reaching a maximum blend rate of 35% by 2040.

This delayed entry of synthetic fuels prevents the complete elimination of fossil fuels, which still account for approximately 24% (gasoline) and 17% (diesel) of total consumption in 2050. The evolution of gasoline and diesel blends is illustrated in Figure 5a,b, respectively.

Figure 5.

Scenario 3 evolution of fuel type (% of energy in the fleet) between 2023 and 2050 of: (a) Fossil gasoline and substitutes; (b) Fossil diesel and substitutes.

Battery electric vehicles (BEVs) continue to show strong market growth, particularly until 2030, when they reach a 40% share. However, limitations in charging infrastructure and persistently high battery production costs prevent BEVs from exceeding a 45% market share by 2040. Additionally, the introduction of alternative fuels to replace fossil gasoline and diesel between 2030 and 2035 makes combustion engine vehicles—especially PHEVs and HEVs—a viable pathway toward carbon neutrality. By 2050, these technologies account for 25% and 20% of the passenger light-duty vehicle market, respectively, effectively marking the end of conventional ICEVs. The remaining 10% is occupied by fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), which begin entering the market between 2030 and 2035. The sales trajectory of these technologies is illustrated in Figure 6a. In the commercial vehicle segment, diesel ICEVs remain dominant, still holding a 50% market share in 2050. The other half is replaced by BEVs (30%) and FCEVs (20%). The transition follows a similar pattern to passenger vehicles, with BEVs leading adoption until 2030–2035, after which, hydrogen-powered vehicles gain greater market relevance. This evolution is also depicted in Figure 6b.

Figure 6.

Scenario 3 market share (%) evolution between 2023 and 2050 of: (a) light-duty passenger vehicles; (b) light-duty vans.

These assumptions lead to the following coefficients for Equation (3). Regarding passenger vehicles: for Natural Gas, , and ; for HEVs, , and ; for PHEVs, , and ; for BEVs, , and and; for Hydrogen, , and ; and for gasoline and diesel, the remaining share is divided 75–25% following the trend of last year’s sales. For light-duty vans: for Natural Gas, , and ; for HEVs, , and ; for PHEVs, , and ; for BEVs, , and and; for Hydrogen, , and ; and for gasoline and diesel, the remaining share is divided 0.5–99.5% following the trend of last year’s sales.

3. Results

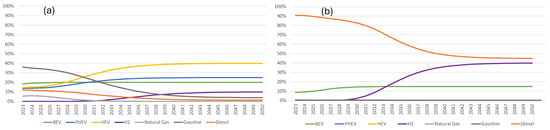

3.1. Scenario 1: Technological Replacement and Transition to Electrification

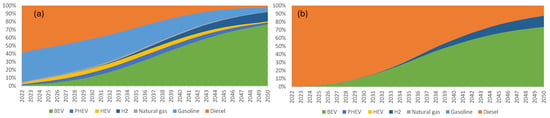

In a scenario where BEVs account for over half of total vehicle sales by 2030, a significant transformation of the vehicle fleet is expected. Figure 7a,b present the expansion of BEVs in circulation is accompanied by a decline in combustion engine vehicles, including conventional ICEVs, PHEVs, and HEVs. Hybrid vehicles (HEVs and PHEVs) peak in fleet share between 2030 and 2040, representing approximately 11% of passenger light-duty vehicles. However, their gradual decline leads to a return to 2022 levels—around 3%—by 2050. ICEVs lose dominance rapidly, ceasing to be the most prevalent technology by 2040.

Figure 7.

Scenario 1 fleet composition (%) between 2023 and 2050 of: (a) light-duty passenger vehicles; (b) light-duty vans.

This fleet transition has a substantial impact on direct (tank-to-wheel) emissions. By 2030, total exhaust emissions are reduced by 26% compared to 2022. The exponential growth of electric vehicles from 2030 onward enables a dramatic reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, reaching a 93% decrease by 2050.

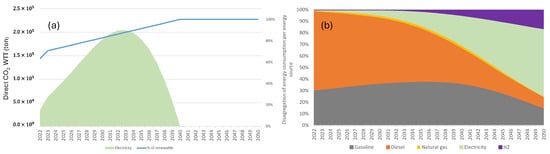

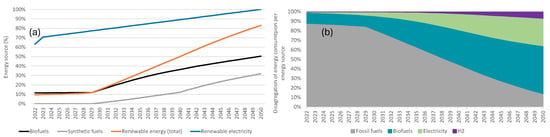

Although tank-to-wheel (TTW) emissions decline with the expansion of zero-exhaust vehicles, upstream emissions from electricity generation remain a critical challenge. The carbon footprint of both FCEVs (hydrogen production) and BEVs depends strongly on the electricity generation mix. If the 2023 emission factor is maintained through to 2050, well-to-tank (WTT) emissions would drop by about 50%, yielding an overall well-to-wheel (WTW) reduction of 82%. However, this would not meet the RNC2050 [32] objective of 99% renewable electricity by 2050. Accordingly, this scenario adopts a more ambitious pathway, achieving 100% renewable generation by 2040 (Figure 8a), which enables 90% WTT and 93% WTW reductions by 2050 (Table 7).

Figure 8.

(a) Electricity well-to-tank CO2 emissions and share of renewables for electricity production; (b) share of fuel used.

Table 7.

Total fleet CO2 emissions.

While the 98% transport GHG reduction target in RNC2050 [32] is not fully achieved, the results remain consistent with the broader EU goal of a 90% GHG reduction. Regarding renewable integration, the PNEC [34] sets a 23% renewable energy share in transport by 2030; however, under this scenario, the target is only met in 2036, reaching ~13% in 2030. Nonetheless, by 2050, it is expected to have a 77% renewable share.

A mid-term goal of 40% GHG reduction by 2030 is also missed—passenger vehicles and light-duty vans only achieve 26% WTW reduction. Despite steady TTW and WTW declines (Table 7), electricity demand growth causes WTT emissions to rise until 2033, when renewables account for 88% of electricity generation (Figure 8a).

As expected, the growing penetration of electric vehicles leads to a substantial increase in electricity demand within the light-duty vehicle (LDV) sector. As shown in Figure 8b, electricity consumption rises sharply—from approximately 707 × 106 MJ (17 kTep) in 2022, representing less than 1% of total LDV energy use, to nearly 685 kTep (≈58%) of final energy consumption by 2050.

Figure 8b also highlights the increasing role of hydrogen, which accounts for 16% of final energy demand by 2050. In contrast, fossil fuel consumption follows a steady downward trend. Due to the initially higher market share of gasoline-powered ICEVs compared to diesel, gasoline consumption experiences a temporary rise, peaking at 38% in 2035. Beyond this point, the growing dominance of battery electric vehicles (BEVs) drives a sharp decline in fossil fuel use, which by 2050 represents only 24% of total energy consumption—15% from gasoline and 9% from diesel.

The higher energy efficiency of BEVs is the main driver of the progressive reduction in total energy demand, resulting in decreases of approximately 24% by 2030 and 71% by 2050 relative to the 2022 baseline.

3.2. Scenario 2: Transition to Alternative Energy Sources (Diesel and Gasoline)

Figure 9a illustrates the long-term evolution of the passenger car fleet up to 2050. The introduction of alternative fuels to diesel and gasoline supports the growth of hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs), making them the dominant technology in the light-duty passenger fleet—rising from 2% in 2022 to 37% by 2050. Plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) follow a similar upward trend, reaching 24%, while battery electric vehicles (BEVs) account for 20% of the fleet by 2050. The remaining share includes fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) at 7%, and internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) at 13%, whose persistence is enabled by the increasing use of biofuels and synthetic fuels rather than a complete technological phase-out. In the case of commercial vehicles (Figure 9b), despite a gradual shift toward BEV and particularly FCEV technologies, diesel ICEVs remain predominant, still representing approximately 60% of the fleet in 2050, followed by FCEVs (26%) and BEVs (15%).

Figure 9.

Scenario 2 fleet composition (%) between 2023 and 2050 of: (a) light-duty passenger vehicles; (b) light-duty vans.

Table 8 summarizes WTW CO2 emissions. Even when using synthetic fuels, combustion generates amounts of CO2 comparable to fossil fuels. Combined with the lower share of BEVs relative to Scenario 1, fleet emissions decrease by only 25% in 2030 and 68% in 2050 compared to 2022, falling short of both national and European targets. However, for biofuels and synthetic fuels, the distinction between direct and net emissions is crucial, since these fuels are produced using captured CO2 and the emitted carbon is later recycled in fuel synthesis, yielding near-zero net emissions.

Table 8.

Total fleet CO2 emissions.

The gap between direct and net emissions widens from 1.5 Mton in 2022 to 5.0 Mton in 2050, leading to WTW CO2 emissions declining by 97% in 2050, confirming the potential to achieve carbon neutrality-result unattainable even in Scenario 1 with an almost fully electrified fleet. Although full renewable electricity is only achieved in 2050, its use in synthetic fuel production ensures an extremely low emission factor (0.9 MJ/g CO2) and a correspondingly small carbon footprint.

In this scenario, the rapid introduction of carbon-neutral alternative fuels offers another renewable alternative in the transportation sector besides electricity. The fact that these can be implemented without the need for a radical technological change offsets the slower transition to 100% renewable electricity and helps achieve the renewable energy incorporation targets set by the PNEC (23% by 2030), since by 2030, 32% of the energy used in light-duty vehicles will come from renewable sources. This evolution in the share of renewable energy incorporation is summarized in Figure 10a.

Figure 10.

(a) Share of renewables in fuels; (b) share of fuel used.

Total energy consumption decreases by 27% in 2030 and 48% in 2050 relative to 2022. This reduction stems primarily from the transition to more efficient propulsion systems, particularly battery electric (BEVs) and hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs). Similar to Scenario 1, the deployment of fully electric powertrains drives a marked rise in electricity demand up to 2035, when synthetic gasoline represents over half of total gasoline use and synthetic diesel begins penetrating the commercial segment.

The evolution of electricity consumption and alternative fuel use is depicted in Figure 10b, highlighting a sharp increase in biofuel and synthetic fuel demand, peaking at 1723 ktep in 2040—a 262% rise compared with 2022.

As shown in Figure 10b, the variation in fuel consumption over time can be divided into three distinct phases:

• Phase 1 (until 2025):

During this initial stage, no significant change occurs in the blending rates of alternative fuels. At the same time, internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) begin to be gradually replaced by battery electric vehicles (BEVs), resulting in an 11% decrease in biofuel consumption compared to 2022.

• Phase 2 (2025–2040):

With the introduction of synthetic fuels, their incorporation in blends for light-duty vehicles increases rapidly and exponentially, rising from 424 ktep in 2025 to 1723 ktep in 2040—a 262% increase relative to 2022. This growth parallels the market expansion of hybrid vehicles, which became the dominant alternative to conventional ICEV during this period.

• Phase 3 (after 2040):

By 2040, fossil gasoline is completely phased out and fully replaced by synthetic gasoline. Its incorporation stabilizes at 80%, leading to a slower overall growth rate in synthetic fuel consumption. Although synthetic diesel also begins to enter the market at this stage, its impact remains limited, given that diesel-powered vehicles account for only about 28% of the fleet, while gasoline vehicles represent roughly 50%.

Furthermore, the introduction of fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) around 2035, primarily replacing diesel-powered commercial ICEVs, contributes to a gradual reduction in conventional fuel consumption. The combined transition effects between energy sources are evident in Figure 10.

Regarding the total WTW energy, it is important to note that the results presented do not consider the electricity required to produce hydrogen via electrolysis. This aspect has implications in this scenario due to the greater market penetration of FCEVs and because one of the initial assumptions is the production of synthetic fuels using green hydrogen. This means that the total electrical energy required to produce this energy will be higher than calculated.

3.3. Scenario 3: Technology Replacement and Transition to Alternative Energy Sources

The substitution of fossil fuels by alternative energy carriers drives moderate fleet modifications, as illustrated in Figure 11. Regarding passenger vehicles, fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) enter the market around 2030, maintaining a limited share of~6% by 2050, while conventional internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) persist at~13%, despite sales ending by 2045. For commercial vehicles, diesel-powered ICEVs remain dominant throughout the projection horizon, representing~60% of the fleet in 2050 (Figure 11b). Among electric technologies, battery electric vehicles (BEVs) exhibit the fastest growth, rising from negligible levels in 2022 to 10% of the passenger fleet by 2030—a tenfold increase. Growth stabilizes after 2040 as synthetic fuels become widespread, yet BEVs ultimately dominate by 2050, accounting for~40% of light-duty passenger vehicles. A similar but slower trend is observed in light commercial vehicles, where BEVs reach 27% market share by 2050, while diesel ICEVs remain the leading technology.

Figure 11.

Scenario 3 fleet composition (%) between 2023 and 2050 of: (a) light-duty passenger vehicles; (b) light-duty vans.

With the introduction of biofuels and synthetic fuels between 2035 and 2040, internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) regain viability as a pathway toward carbon neutrality. Nevertheless, conventional ICEVs continue to decline gradually, being replaced by more efficient hybrid technologies, such as hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), with the latter showing slightly higher market penetration.

Although HEVs currently dominate the hybrid segment, representing 3% of the passenger car fleet compared to 2% for PHEVs, the expansion of charging infrastructure makes plug-in technologies more attractive for reducing GHG emissions. Moreover, PHEVs benefit directly from the use of synthetic fuels starting in 2035, becoming the second most prevalent technology in the national fleet by 2050.

For light commercial vehicles, alternative powertrains such as BEV and later FCEV gain traction, reaching 27% and 12% market shares, respectively, by 2050.

With this fleet transformation and transition to more efficient propulsion technologies, it is possible to reduce direct WTW emissions by 24% by 2030 and 76% by 2050, as shown in Table 9. However, to truly understand the true magnitude of the CO2 reduction, it is necessary to analyze the net emissions, indicating that the difference between net and direct emissions begins to increase with the introduction of synthetic fuels, particularly from 2035 onwards.

Table 9.

Total fleet CO2 emissions.

As previously noted, the gap between net and direct CO2 emissions from synthetic fuels results from their production pathway, which combines captured atmospheric CO2 with hydrogen derived from renewable electricity. Although a fully renewable grid is only achieved by 2050, it is assumed that synthetic fuels are produced exclusively using renewable energy.

The late introduction of synthetic fuels and slower BEV deployment lead to the lowest renewable incorporation rate among the scenarios—15% in 2030, rising to 83% by 2050 (Figure 12a). Until 2035, the emphasis on electric mobility drives a nearly sevenfold increase in electricity demand (Figure 12b). Beyond this point, biofuels and synthetic fuels gain prominence, with hybrid technologies contributing significantly to reducing total energy consumption. Despite similarities to Scenario 1, fossil fuels still compose part of gasoline and diesel blends in 2050, with approximately 73% of residual WTW CO2 emissions stemming from these fuels.

Figure 12.

(a) Share of renewables in fuels; (b) share of fuel used.

The evolution of synthetic fuel consumption, shown in Figure 12b, follows a trend similar to that of Scenario 2, although the previously identified “Phase 3” is absent. In this case, incorporation levels continue to grow steadily until 2050, albeit at a slower pace. This continuous increase is largely attributed to the more conservative introduction of hydrogen-powered vehicles, which would otherwise replace a significant portion of diesel-based internal combustion vehicles, particularly in the commercial sector.

Unlike the previous scenarios, however, fossil fuels maintain a notable share even in 2050, corresponding to 254 ktep, or approximately 14% of the total energy consumption. The remaining final energy demand is predominantly covered by biofuels (50%) and electricity (29%), while hydrogen accounts for the smallest fraction, around 7%. These results, along with the temporal evolution of the energy mix, are presented in Figure 12b.

4. Discussion

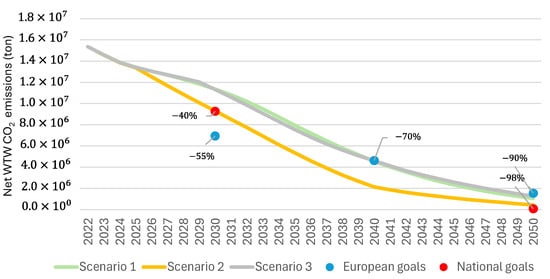

A comparative analysis of the three projected scenarios highlights that, in all cases, Net WTW CO2 emissions are reduced by over 90%, in line with the 85–90% GHG reduction targets established in the RNC2050 [32]. Figure 13 illustrates the evolution of net WTW CO2 emissions over time, together with benchmark points corresponding to the PNEC emission-reduction milestones.

Figure 13.

Net WTW CO2 emissions for the 3 studied scenarios and National and European targets.

Among all cases, Scenario 2 delivers the largest emission reduction, driven by the early and widespread adoption of synthetic fuels. By directly substituting fossil fuels with low-carbon alternatives, it enables faster mitigation without requiring an immediate fleet overhaul. The introduction of biofuels and synthetic fuels around 2025 allows the existing ICEV fleet—representing about 95% of total vehicles—to rapidly benefit from reduced carbon intensity, resulting in a sharp emission decline between 2022 and 2030. In contrast, Scenario 1, based solely on full electrification, faces slower progress due to the time needed for fleet renewal. Despite BEV shares increasing by ~5%/year from 2022–2035, they only represent 25% of the passenger fleet by 2035, highlighting that altering the energy source is a more effective near-term decarbonization pathway. Scenario 3 adopts a hybrid approach, combining moderate electrification with controlled synthetic fuel integration. While limited fossil fuel use persists beyond 2050, its outcomes remain comparable to Scenario 1, suggesting that a balanced strategy may offer a more feasible and cost-effective route to long-term carbon neutrality.

The PNEC2030 [34] and RNC2050 [32] targets encompass all transport modes, including heavy-duty, rail, and aviation. To isolate light-duty vehicles (LDVs), data from the EEA [54] were used. The results show that road transport contributes over 70% of transport-related CO2, with LDVs accounting for ~52%. Assuming this share remains constant through 2050, the RNC2050 [32] targets can be directly compared to the modeled scenarios, as summarized in Table 10.

Table 10.

Tank-to-Wheel net CO2 emissions (Mton) for light-duty vehicles (passenger and commercial).

The results in Table 10 confirm that achieving the 2030 decarbonization goals will be highly challenging, particularly if electric mobility remains the sole strategy towards carbon neutrality.

The improved efficiency of advanced propulsion systems and the gradual phase-out of internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) resulted in a steady decline in total final energy consumption across all three scenarios. Among the evaluated technologies, battery electric vehicles (BEVs) are the most energy-efficient, consuming approximately 3.8 times less energy per kilometer than ICEVs and half that of hybrid vehicles. Consequently, the scenario with the highest BEV penetration exhibits the largest energy savings.

Scenario 2 eliminates fossil gasoline by 2040, replacing it entirely with synthetic fuels, while Scenario 3 retains a residual share beyond 2050. In contrast, Scenario 1 (despite ending ICEV sales after 2040) fails to fully phase out combustion engines due to the absence of synthetic fuel deployment, diverging from RNC2050 [32] targets. Continued gasoline use indicates the persistence of ICEVs, HEVs, and PHEVs, underscoring the challenge of achieving full electrification without regulatory or fiscal incentives.

Diesel and electricity trends are more complex: diesel remains dominant in heavy-duty transport (≈60% from LDVs), while electricity accounts for roughly 92% of total road transport consumption. Under Scenario 1, BEV expansion drives electricity demand to levels 40 times higher than 2022, corresponding to a 73-fold increase in BEV fleet size by 2050—imposing significant pressure on power generation and charging infrastructure.

A mixed approach, as in Scenarios 2 and 3, mitigates infrastructure strain by utilizing existing fuel distribution networks. However, large-scale green hydrogen (H2) production for synthetic fuels still imposes substantial electricity requirements. In Scenario 2, synthesizing 907 ktep of gasoline and 273 ktep of diesel by 2050 demands approximately three times more electricity than Scenario 1. This trade-off underscores the critical dependence of synthetic fuel strategies on renewable electricity availability—without which increased power demand could offset decarbonization gains.

5. Conclusions

A key structural constraint in achieving full electrification lies in the vehicle’s survival curve: with an average fleet age of 14 years, accelerating turnover would require large-scale scrappage and incentive programs. Similar challenges affect light commercial vehicles, where diesel ICEVs dominate and renewal is slower, making the RNC target of full electrification by 2030 unrealistic without dedicated replacement policies. Although national goals encompass the entire transport sector, road transport remains central, accounting for over 70% of the total emissions in EU-27, with LDVs contributing about 62% in 2022 in Portugal [55].

Scenario 1, aligned with the National Roadmap for Carbon Neutrality (RNC2050), assumes electric mobility as the main driver of GHG reduction. However, its milestones—36% EV penetration by 2030 and full electrification by 2050—appear overly ambitious. Even with rapid market growth, BEVs would comprise only 12% of the fleet in 2030 and 77% in 2050, requiring nearly all new sales to be electric. Comparisons with RNC2050 projections are limited by data aggregation by energy sources rather than transport mode. For gasoline, predominantly used in LDVs, the deviation between this study (1035 ktep) and the 2022 national balance (1121 ktep [56]) is 7.6%.

Considering future standards, if EURO 7 enters into force by 2026, its penetration remains limited. In Scenario 1, EURO 7 ICEVs peak at 15% of the fleet by 2035, while in Scenario 2 they reach 33%, rising to 60% by 2050. These estimates align with ACEA [57], which foresees EURO 7 vehicles representing only 10% of the European fleet by 2035.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.O.D. and P.C.B.; methodology, J.S. and P.C.B.; validation, G.O.D. and P.C.B.; formal analysis, J.S., G.O.D. and P.C.B.; investigation, J.S.; resources, J.S.; data curation, J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S.; writing—review and editing, G.O.D. and P.C.B.; supervision, G.O.D. and P.C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was carried out within the scope of the project BE.Neutral–Mobility Agenda for Carbon Neutrality in Cities (contract no. 35) funded by the Plano de Recuperação e Resiliência (PRR) through the European Union’s Next Generation EU programme. The authors also acknowledge the financial support of Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) through LARSyS (project UIDB/50009/2025).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Eurostat. Final Energy Consumption in Transport—Detailed Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Final_energy_consumption_in_transport_-_detailed_statistics (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- International Energy Agency. Portugal 2021 Energy Policy Review; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Presidency of the Council of Ministers. Decree Law No. 84/2022. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/en/detail/decree-law/84-2022-204502328 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Entidade Reguladora dos Serviços Energéticos. Análise do Mercado de Biocombustíveis 2018–2020; Entidade Reguladora dos Serviços Energéticos: Lisbon, Portugal, 2024; Available online: https://www.erse.pt/media/eknhoezr/relat%C3%B3rio-biocombust%C3%ADveis.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Rosa, M. Situação Actual Dos Biocombustíveis e Perspectivas Futuras. In Gazeta de Física; Sociedade Portuguesa de Física: Lisbon, Portugal, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Porsche Newsroom Innovation. Sustainability. Performance. Available online: https://newsroom.porsche.com/dam/jcr:ac039d97-97ed-4b22-8c9d-0e6c7363197e/PAG-Media-Workshop-Innovation-Sustainability-Performance-en.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Sanguesa, J.A.; Torres-Sanz, V.; Garrido, P.; Martinez, F.J.; Marquez-Barja, J.M. A Review on Electric Vehicles: Technologies and Challenges. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 372–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmers, V.R.J.H.; Achten, P.A.J. Non-Exhaust PM Emissions from Electric Vehicles. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 134, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency Hydrogen. Available online: https://www.irena.org/Energy-Transition/Technology/Hydrogen (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) 2024/1257 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 April 2024 on Type-Approval of Motor Vehicles and Engines and of Systems, Components and Separate Technical Units Intended for Such Vehicles, with Respect to Their Emissions and Battery Durability (Euro 7), Amending Regulation (EU) 2018/858 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Repealing Regulations (EC) No 715/2007 and (EC) No 595/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Regulation (EU) No 582/2011, Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/1151, Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/2400 and Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/1362Text with EEA Relevance. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=OJ:L_202401257 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- European Parliament. Regulation (EU) 2023/851 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 April 2023 Amending Regulation (EU) 2019/631 as Regards Strengthening the CO2 Emission Performance Standards for New Passenger Cars and New Light Commercial Vehicles in Line with the Union’s Increased Climate Ambition. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/851/oj/eng (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- European Parliament. Regulation (EU) 2019/631 of the European Parliament and of the Council—Of 17 April 2019—Setting CO2 Emission Performance Standards for New Passenger Cars and for New Light Commercial Vehicles, and Repealing Regulations (EC) No 443/2009 and (EU) No 510/2011. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/631/oj/eng (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- European Commission. Cars and Vans-Climate Action-European Commission. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/transport-decarbonisation/road-transport/cars-and-vans_en (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- The Internation Council on Clean Transportation. European Vehicle Market Statistics-Pocketbook 2024/25; International Council on Clean Transportation Europe: Berlin, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA). The Automobile Industry-Pocketguide 2024/2025; ACEA: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mickūnaitis, V.; Pikūnas, A.; Mackoit, I. Reducing Fuel Consumption and CO2 Emission in Motor Cars. Transport 2007, 22, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA). New Car Registrations: -0.1% in August 2025 Year-to-Date; Battery-Electric 15.8% Market Share. ACEA—European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association. 2025. Available online: https://www.acea.auto/pc-registrations/new-car-registrations-0-1-in-august-2025-year-to-date-battery-electric-15-8-market-share/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Ritchie, H.; Rosado, P. Electricity Mix. In Our World in Data; Global Change Data Lab: Oxford, UK, 2020; Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/electricity-mix (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Kelly, J.C.; Kim, T.; Kolodziej, C.P.; Iyer, R.K.; Tripathi, S.; Elgowainy, A.; Wang, M. Comprehensive Cradle to Grave Life Cycle Analysis of On-Road Vehicles in the United States Based on GREET; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Elgowainy, A.; Han, J.; Ward, J.; Joseck, F.; Gohlke, D.; Lindauer, A.; Ramsden, T.; Biddy, M.; Alexander, M.; Barnhart, S.; et al. Current and Future United States Light-Duty Vehicle Pathways: Cradle-to-Grave Lifecycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Economic Assessment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 2392–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo Energy and Environment. Lifecycle Analysis of UK Road Vehicles; Ricardo Energy and Environment: Shoreham-by-Sea, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.C.; Wallington, T.J.; Arsenault, R.; Bae, C.; Ahn, S.; Lee, J. Cradle-to-Gate Emissions from a Commercial Electric Vehicle Li-Ion Battery: A Comparative Analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 7715–7722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri, M.; Bieker, G. Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Passenger Cars in the European Union: A 2025 Update and Key Factors to Conside; International Council on Clean Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bieker, G. A Global Comparison of the Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Combustion Engine and Electric Passenger Cars—White Paper; International Council on Clean Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Joint Research Centre. JEC Well-to-Tank Report V5: JEC Well to Wheels Analysis: Well to Wheels Analysis of Future Automotive Fuels and Powertrains in the European Context; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2020.

- Powell, N.; Hill, N.; Bates, J.; Bottrell, N.; Biedka, M.; White, B.; Pine, T.; Carter, S.; Patterson, J.; Yucel, S. Impact Analysis of Mass EV Adoption and Low Carbon Intensity Fuels Scenarios—Summary Report; Ricardo: Shoreham-by-Sea, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ricardo. Impact Analysis of Mass EV Adoption and Low-Carbon Intensity Fuels Scenarios; Ricardo: Shoreham-by-Sea, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Road Transport Research Advisory Council (ERTRAC). Carbon-Neutral Road Transport 2050: A Technical Study from a Well-to-Wheels Perspective; European Road Transport Research Advisory Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mock, P.; Díaz, S. Pathways to Decarbonization: The European Passenger Car Market in the Years 2021–2035; International Council on Clean Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency. Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5 °C Goal in Reach (2023 Update); International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency. Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Portuguese Republic. Roteiro Para a Neutralidade Carbónica 2050 (RNC2050); Portuguese Republic: Lisbon, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Presidency of the Council of Ministers. Resolution n. 149/2024; Presidency of the Council of Ministers: Rome, Italy, 2024.

- Portuguese Republic. Plano Nacional de Energia e Clima 2021–2030 (PNEC 2030); Portuguese Republic: Lisbon, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ACAP. Available online: http://acap.pt/index.php?route=base/pt/estatisticas (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Baptista, P. Evaluation of the Impacts of the Introduction of Alternative Fuelled Vehicles in the Road Transportation Sector. Ph.D. Thesis, Instituto Superior Técnico, Lisbon, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dargay, J.; Gately, D.; Sommer, M. Vehicle Ownership and Income Growth, Worldwide: 1960–2030. Energy J. 2007, 28, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatawneh, A.; Torok, A. Potential Autonomous Vehicle Ownership Growth in Hungary Using the Gompertz Model. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2023, 29, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portuguese Environment Agency. Relatório do Estado do Ambiente 2024; Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente: Lisbon, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistics Institute. Projeção População Residente 2018–2080; Instituto Nacional de Estatística: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA). Vehicles on European Roads (2024); ACEA: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Portuguese Environment Agency. National Inventory Report 2023 Portugal; Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente: Lisbon, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA). New Car Registrations: +13.9% in 2023; Battery Electric 14.6% Market Share. 2024. Available online: https://www.acea.auto/pc-registrations/new-car-registrations-13-9-in-2023-battery-electric-14-6-market-share/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA). New Commercial Vehicle Registrations: Vans +14.6%, Trucks +16.3%, Buses +19.4% in 2023. 2024. Available online: https://www.acea.auto/cv-registrations/new-commercial-vehicle-registrations-vans-14-6-trucks-16-3-buses-19-4-in-2023/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Nissan Reveals European EV Drivers Are Travelling Further than Petrol and Diesel Motorists. Available online: https://europe.nissannews.com/en-GB/releases/nissan-reveals-european-ev-drivers-are-travelling-further-than-petrol-and-diesel-motorists (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Lu, S. Vehicle Survivability and Travel Mileage Schedules; National Highway Traffic Safety Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). Manual on Tests and Criteria for the Determination of Fuel Consumption and CO₂ Emissions of Light-Duty Vehicles (WLTP Guidelines). UNECE Regulation No. 101—Uniform Provisions Concerning the Approval of Passenger Cars Powered by an Internal Combustion Engine or an Electric Motor with Regard to the Measurement of the Emission of Carbon Dioxide and Fuel Consumption; UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories: Volume 2—Energy, Chapter 2: Stationary Combustion; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES): Hayama, Japan, 2006; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- 2023 (Full Year) Europe: Top 20 Best-Selling Electric Car Models—Car Sales Statistics. Available online: https://www.best-selling-cars.com/europe/2023-full-year-europe-top-20-best-selling-electric-car-models/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- MPG and Cost Calculator and Tracker—Spritmonitor. Available online: https://www.spritmonitor.de/en/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- European Environment Agency. Greenhouse Gas Emission Intensity of Electricity Generation in Europe. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/greenhouse-gas-emission-intensity-of-1 (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Porsche eFuels Pilot Plant in Chile Officially Opened. Available online: https://newsroom.porsche.com/en/2022/company/porsche-highly-innovative-fuels-hif-opening-efuels-pilot-plant-haru-oni-chile-synthetic-fuels-30732.html (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Yugo, M.; Soler, A. Concawe Review; Concawe: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Transport in Europe. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/greenhouse-gas-emissions-from-transport (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- European Environment Agency Climate. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/sustainability-of-europes-mobility-systems/climate (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- DGEG—Direção Geral de Energia e Geologia. Balanço Energético Nacional 2022; DGEG: Lisbon, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA). A Mere 10% of Combustion Engine Cars on EU Roads Set to Fall under Euro 7 Rules in 2035. 2023. Available online: https://www.acea.auto/figure/a-mere-10-of-combustion-engine-cars-on-eu-roads-set-to-fall-under-euro-7-rules-in-2035/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).