Abstract

Enhancing the evaporator configuration of plate heat exchangers is essential for improving the overall efficiency of organic Rankine cycle (ORC) systems. To investigate the evaporator’s heat transfer characteristics, an experimental ORC test rig was developed. The experiments were conducted at saturation temperatures of 62.8–86.2 °C, mass fluxes of 5.0–16.6 kg/(m2·s), and heat fluxes of 3.1–9.2 kW/m2, spanning subcooled boiling, saturated two-phase, and superheating regions. The heat flux showed minimal variation with heat source temperature, whereas higher mass fluxes resulted in substantial increases in generator power and thermal efficiency due to enhanced convection and vaporization. The overall and refrigerant heat transfer coefficients rise with heat source temperature and mass flux, peaking under moderate conditions and declining as the superheating region becomes constrained. Comparison with existing correlations reveals pronounced deviations, indicating their limited applicability under the present operating conditions. A nondimensional correlation was established using dimensional analysis and multivariate regression to predict heat transfer across the subcooled boiling, saturated two-phase, and superheating regions. The proposed correlation yielded a mean absolute percentage error of 15.9%, demonstrating good predictive accuracy and providing a reliable theoretical basis for performance evaluation and design optimization of plate evaporators in ORC systems.

1. Introduction

With the rapid growth of renewable energy and the increasing demand for industrial waste heat recovery, the efficient utilization of low-grade heat has become increasingly important [1,2]. Approximately 70% of total primary energy is ultimately discharged as waste heat during energy conversion and utilization processes [3]. However, owing to its low thermodynamic quality and the lack of efficient recovery technologies, more than 60% of waste heat below 100 °C remains underutilized worldwide [4]. To address this challenge, the Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) provides an effective solution for converting medium-temperature and low-temperature thermal energy, and it has been widely applied in geothermal power generation, biomass utilization, and industrial waste heat recovery [5,6,7]. As a critical component of ORC systems, the heat exchanger significantly affects both thermal efficiency and operational stability [8,9,10]. Among the different types, plate heat exchangers (PHEs) are widely used in ORC systems due to their compact design, high heat transfer efficiency, and ease of maintenance [11,12,13].

Numerous studies have investigated the impact of heat exchanger performance on the overall behavior of ORC systems. Zheng et al. [14] investigated the influence of working fluid flow rate on the overall heat transfer coefficient (HTC) and operational characteristics across different ORC regions. They found that increasing the heat transfer areas of the evaporator and condenser led to enhancements in net power output and thermal efficiency, with increases of up to 9.44% and 7.91%, respectively. Luo et al. [15] investigated the thermal performance of ORC heat exchangers under various off-design operating conditions using experimental tests and modeling analysis. Their simulation model allowed a segmented assessment of HTC variations across both the heat source and refrigerant sides, as well as the distribution of heat exchanger areas. Peris et al. [16] performed multi-variable thermo-economic optimization of heat exchangers using empirical data, achieving an 11.7% reduction in investment cost while improving thermal efficiency by 0.48%. Zhang et al. [17] examined how various PHE design correlations affect the thermodynamic, economic, and environmental performance of ORC systems. Their results indicated that the condensers were particularly sensitive to the chosen heat transfer correlations, resulting in a relative difference of 11.2% in electricity production cost. These findings collectively highlight that accurate estimation of HTC and appropriate selection of design correlations are essential for performance prediction and efficiency optimization in ORC systems.

The heat transfer process within an evaporator generally comprises subcooled boiling, saturated two-phase, and superheating regions. Numerous studies have examined the heat transfer characteristics of each region in PHEs. In subcooled boiling region, Hsieh et al. [18] analyzed the subcooled flow boiling of R134a in a vertical PHE at saturation temperatures of 21.6 and 26.7 °C, with liquid inlet subcooling ranging from 10 to 15 °C. Agostini et al. [19] compared the HTCs of R245fa at a saturation temperature of approximately 38.1 °C, with subcooling levels ranging from 0.6 to 18.3 °C. The results indicated that downstream subcooling had negligible effects on HTC in the saturated region, whereas in the subcooled boiling regime, HTC progressively decreased with increasing subcooling. As for the superheating region, Imran et al. [20] established a model to estimate the HTC in a brazed PHE with R245fa, considering saturation temperatures of 62.7 and 69.4 °C and inlet vapor qualities of 0.1–0.8, thereby covering both the saturated two-phase boiling and preheating regions. Longo et al. [21] formulated a novel framework for refrigerant boiling in brazed PHEs. The model was validated against experimental data obtained under outlet vapor superheating of 5–10 °C and can be extended to other conditions with outlet vapor superheating.

In contrast, the saturated two-phase region has been more extensively studied than the subcooled boiling and superheating regions, and numerous HTC correlations have been developed for this region [22,23,24,25,26]. Zhang et al. [27] conducted a detailed study on the saturated boiling heat transfer behavior of R134a, R1234yf, and R1234ze(E) over saturation temperatures ranging from 60 to 80 °C. They explored how the heat transfer rates varied with different outlet vapor qualities, which ranged from 0.5 to 1.0. Desideri et al. [28] advanced predictive correlations for saturated two-phase boiling within PHEs employing R245fa and R1233zd(E), targeting saturation temperatures of 100, 115, and 130 °C, where inlet vapor quality ranged from 0.1 to 0.4, and outlet conditions corresponded to 0.5–1. In recent studies, Zheng et al. [29] quantitatively characterized quasi-local HTCs and associated area distributions across different boiling stages in a PHE, encompassing preheating, subcooled boiling, saturated flow, and superheating regions. Although several improved prediction methods have been proposed for evaporators accounting for subcooled liquid at the inlet and superheated vapor at the outlet, most existing studies are restricted to a single heat transfer region or to combinations of two regions, such as the subcooled region in combination with the saturated two-phase region, or the saturated two-phase region in combination with the superheating region. In both experimental setups and operational ORC systems, the evaporator typically operates across multiple thermal regimes, including subcooled boiling, saturated two-phase flow, and superheating [30,31,32,33]. Furthermore, the HTC varies by an order of magnitude across different regions, with values in the saturated two-phase region being significantly higher than those in the subcooled boiling or superheating regions. Consequently, developing predictive models that comprehensively encompass all three regions is essential for the accurate design of ORC evaporators.

Based on the above analysis, an experimental platform for the ORC system was established in this study to investigate the heat transfer characteristics of a plate evaporator under various operating conditions, including saturation temperatures of 62.8–86.2 °C, mass fluxes of 5.0–16.6 kg/(m2·s), heat fluxes of 3.1–9.2 kW/m2, inlet subcooling degrees of 30–54 °C, and outlet superheating degrees of 20–49 °C. The effects of heat source temperature and mass flux on both the overall and refrigerant HTCs, as well as ORC operational performance, were first analyzed. The experimentally obtained refrigerant HTCs were subsequently compared with existing predictive methods. Finally, a unified nondimensional correlation was developed using dimensional analysis and multivariate regression, applicable across the subcooled, saturated two-phase, and superheating regions. This correlation effectively captures the combined effects of multiple heat transfer mechanisms and overcomes the limitations of conventional empirical models. The results of this study provide a new theoretical basis and practical guidance for predicting heat transfer performance and optimizing the design of PHEs in ORC systems.

The manuscript comprises four main sections. Section 2 details the design of the experimental setup, and data processing procedures, along with a review of existing heat transfer methods. Section 3 presents the analysis of experimental data, evaluates the predictive performance of current models, and proposes a new unified correlation for predicting the HTC across different regions. Section 4 presents a summary of the key findings derived from the study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Apparatus

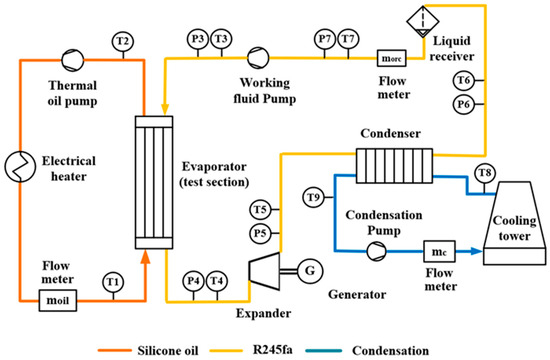

Figure 1 and Figure 2 present the experimental apparatus in both schematic and photographic views. The system comprises three main circuits: the heat source loop, the ORC loop, and the heat sink loop. The heat source loop includes an electric heater and a thermal oil pump. Silicone oil is employed as the working medium to simulate the heat source. The electric heater provides a maximum heating power of 20 kW, and an integrated temperature controller enables the heat source temperature to be adjusted between 100 °C and 130 °C. The heat sink loop comprises a cooling tower and a condensation pump. The cooling tower, installed outdoors, supplies cooling water to the condenser. The cooling water temperature varies with ambient conditions, and a regulating valve is used to adjust the flow rate to maintain stable operating conditions.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the experimental apparatus.

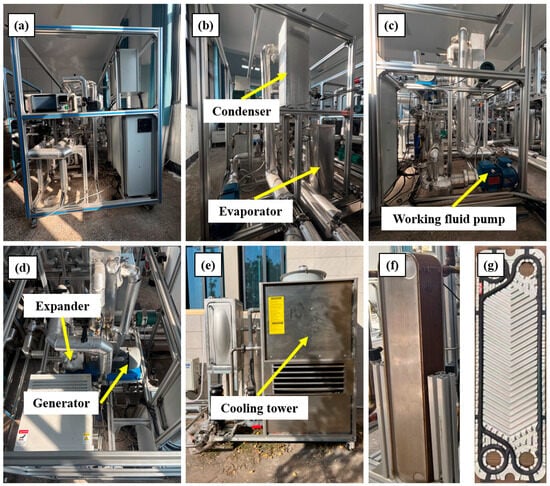

Figure 2.

Photographs of the experimental test rig: (a) frontal view, (b) back view, (c) lateral view, (d) top view, (e) cooling tower, (f) PHE, and (g) a plant of PHE.

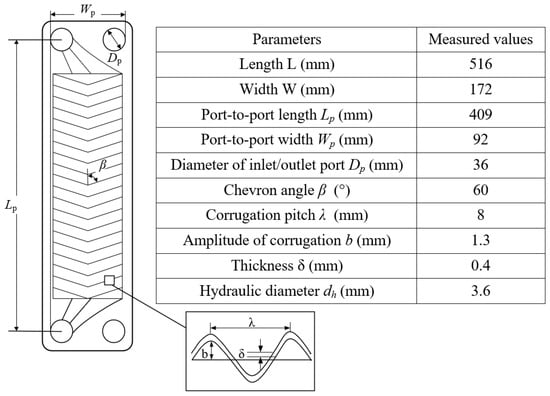

In the ORC loop, the pump pressurizes R245fa before it enters the evaporator, where it absorbs heat from the thermal oil and is subsequently converted into superheated vapor. This vapor then flows through the expander, converting thermal energy into mechanical power to drive the generator for electrical output. After expansion, the vapor is condensed into subcooled liquid in the condenser and then directed to the receiver tank for storage. The expander is a scroll-type unit operating at a rotational speed between 1000 and 3000 rpm, with a maximum output power of 2 kW. It is directly coupled to a permanent magnet synchronous generator rated at 2.2 kW. The working fluid pump is a horizontal, magnetically driven gear pump equipped with a frequency inverter, allowing precise flow rate control within the ORC system. The test section employs a brazed PHE consisting of 30 stainless-steel plates, forming 15 thermal oil channels and 14 working fluid channels. Figure 3 shows a schematic view of the chevron-patterned plates, highlighting the main dimensional specifications. The experimental apparatus was customized by Beijing SanCan Research and Learning Technology Co., Ltd. in Beijing, China. R245fa is supplied by Honeywell (China) Co., Ltd. in Shanghai, China, while silicone oil is provided by Suzhou Youleng New Materials Technology Co., Ltd. in Suzhou, China.

Figure 3.

Schematic and geometric details of a chevron-type plate.

2.2. Data Reduction

The heat transfer surface area of the evaporator Aeva can be calculated from its geometric dimensions as follows:

where Nwf indicates the total number of channels on the refrigerant side.

The dimensionless parameter φ, which accounts for the additional surface area introduced by the sinusoidal corrugation of the plates, is determined as follows:

The corrugation parameter γ is defined as follows:

The effective flow area for the working fluid channel A0, is expressed as follows:

The geometric characteristics of the chevron plates were determined based on the definitions proposed by Martin [34]. The hydraulic diameter dₕ for a working-fluid passage bounded by a pair of chevron plates can be calculated as follows:

The HTC of the refrigerant αwf is expressed as follows:

where U represents the overall HTC, αoil is the HTC of the thermal oil, δwall refers to the plate thickness, while kwall indicates the thermal conductivity of the plate.

The HTC is critical for determining the design efficiency and operational performance of heat exchangers. Direct measurement of the HTC is challenging because an evaporator includes multiple heat transfer regions, each characterized by distinct HTC values, and the relative area of each region varies with operating conditions. In this study, the evaporator’s heat transfer surface area is known, allowing the overall HTC to be obtained from experimental data. Nevertheless, since the area of each individual region is unknown, the overall thermal conductance UA is used as a lumped parameter. The UA value has been widely adopted to evaluate its economic and operational efficiency without requiring detailed calculation of the HTC in each section [35,36].

The overall heat transfer coefficient U was computed using the log mean temperature difference (LMTD) method and is expressed as follows:

where mwf denotes the mass flow rate of the refrigerant, and hwf,in and hwf,out represent the inlet and outlet enthalpies of the refrigerant at the evaporator, respectively.

The UA of each region of the heat exchanger is defined as follows:

where hwf,sat,l and hwf,sat,v represent the enthalpies of the saturated liquid and saturated vapor states of the refrigerant, respectively.

The HTC of the thermal oil αoil is defined as [27]:

where Reoil represents the Reynolds number of thermal oil, Proil represents the Prandtl number of the thermal oil, μoil represents the dynamic viscosities based on mean thermal oil temperature, and μwall represents the dynamic viscosities based on wall temperature.

The thermal efficiency of ORC ηorc, represents the ratio between the net generator power Wgen and the heat absorbed in ORC evaporator, which can be expressed as follows:

2.3. Uncertainty Analysis

In this study, key components are instrumented with temperature and pressure sensors positioned at both the inlet and outlet, including evaporator, condenser and expander, flow meters are installed in each loop to monitor real-time fluid flow, and the detailed location are indicated in Figure 1. Table 1 summarizes the details of the measurement instruments used in the experimental setup. A centralized data acquisition system collects all sensor signals, which are then recorded on a computer. A custom-built LabVIEW interface is developed for real-time monitoring, visualization, and logging of key system variables, enabling efficient tracking of system dynamics during the experiments. A sampling interval of 1 s is adopted to ensure sufficient temporal resolution for transient performance analysis. To assess the reliability of the measured data and calculated performance indicators, an uncertainty analysis was conducted using the root sum of squares method. This method allows the estimation of uncertainty in a calculated result by propagating the uncertainties of all contributing independent variables. The uncertainty propagation is expressed as follows [37]:

where δy1, δy2, …, δyn correspond to the uncertainty in the values directly measured during the experiment. The uncertainty of refrigerant heat transfer coefficient is from 5.2% to 14.8%.

Table 1.

Specifications of measurement instruments.

2.4. Review of Existing Heat Transfer Correlations

The saturated two-phase region takes up the largest share of UA and has the greatest impact on overall performance. Accordingly, three representative correlations were selected in this study to estimate saturated two-phase boiling heat transfer [29,38,39]. In addition, a correlation accounting for subcooled boiling heat transfer was considered, covering refrigerant inlet subcooling from 10 to 15 °C [18]. Another method combining saturated two-phase boiling and superheating boiling was also employed, covering refrigerant outlet superheating from 5 to 10 °C [21].

2.4.1. Amalfi Prediction Method

The Amalfi correlation is based on an extensive dataset of 1903 heat transfer measurements, encompassing a wide range of boiling conditions, including saturated, adiabatic, and subcooled boiling regimes. This comprehensive dataset has shown consistent reliability across various operating conditions, different plate designs, and multiple working fluids. The model incorporates several dimensionless numbers to account for the effects of flow behavior and geometric parameters.

where αTP denotes the HTC in the saturated two-phase region. The following variables are used: x for thermodynamic quality, ρ for density, g for gravitational acceleration, σ for surface tension, Δhlv for vaporization latent heat, and λm for homogeneous thermal conductivity. The subscripts l,sat/v,sat refer to the saturated liquid and saturated vapor states, respectively. β* presents the ratio of the chevron angle β to the largest chevron angle investigated in the current databank (70°). Bd represents Bond number, Rev and Relo represents the vapor and liquid Reynolds numbers, respectively. Bo represents Boiling number.

2.4.2. Han Prediction Method

The Han correlation is widely used in the design of PHEs due to its detailed characterization of the interaction between complex plate geometry and saturated two-phase flow. The correlation introduces two geometric dimensionless parameters, along with equivalent Reynolds and Boiling numbers, to quantify heat transfer intensity under different boiling conditions.

where G and GEq denote the mass flux and the equivalent mass flux, respectively. Ge1 and Ge2 present dimensionless geometric parameters, pco presents the corrugation pitch, ReEq presents the equivalent Reynolds, and BoEq presents the equivalent Boiling numbers.

2.4.3. Zheng Prediction Method

Heat transfer in the saturated boiling state is governed by both convective and nucleate boiling mechanisms, each contributing to the overall heat transfer [40]. Following the general structure of the Chen model [41], the Zheng correlation incorporates two components. The suppression factor (S) and enhancement factor (E) scale the contributions of nucleate and convective boiling to the overall HTC, incorporating several dimensionless numbers and thermophysical properties.

where αlo corresponds to the convective boiling HTC, calculated based on the Dittus–Boelter relation [42], whereas αpool corresponds to that of pool boiling, determined using Cooper’s formulation [43]. P*/Pcrit represent the reduced/critical pressure, with M representing the molar mass.

where ρm represents the mean density.

2.4.4. Hsieh Prediction Method

Hsieh et al. [18] developed a subcooled flow boiling correlation that extends the single-phase convection heat transfer model. By incorporating the Froude number (Fr), Boiling number (Bo), and Jakob number (Ja), their correlation accounts for the variation in boiling heat flux with cross-channel superheat and captures the convective effects of flow boiling. The HTC in the subcooled flow boiling αr,sub can be correlated as:

where αr,l is the HTC determined from the single-phase heat transfer.

2.4.5. Longo Prediction Method

The Longo et al. [21] correlation, which is widely used for modeling saturated refrigerant boiling conditions, was coupled with a single-phase heat transfer coefficient correlation to predict the average heat transfer coefficient during boiling with outlet vapor superheating tests. When the evaporator operates under both boiling and superheating conditions, the overall refrigerant HTC of the evaporator αave,clc is calculated as the area-weighted average of the HTC in the boiling region αb and that in the superheating region αs. The boiling HTC αb as the maximum of the average convective boiling HTC αcb and the average nucleate boiling heat transfer coefficient αnb. αs is determined by applying a single-phase heat transfer model.

where CRa accounts for the effect of the arithmetic mean roughness, Ra of the plates as defined in ISO4287/1. Qb and Qs represent the heat transfer rate, Ub and Us represent the overall HTC, and Tln,b and Tln,s represent the LMTD. The subscripts b/s refer to the boiling and the superheating regions, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Steady-State Operation Test

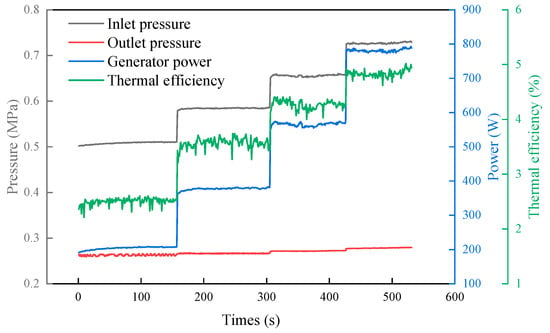

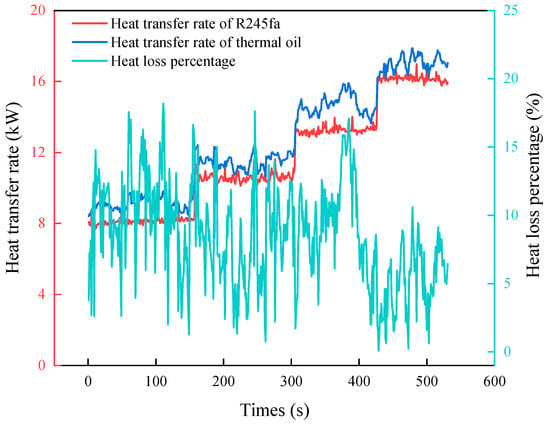

Operational stability was evaluated through tests conducted at a constant thermal oil flow rate, with the temperature maintained at 120 °C. During the tests, the refrigerant mass flux was gradually increased from 5.0 kg/(m2·s) to 9.8 kg/(m2·s). Figure 4 and Figure 5 present the system’s thermodynamic performance, showing variations in expander inlet and outlet pressures, generator power, thermal efficiency, and the evaporator energy balance under different refrigerant mass fluxes.

Figure 4.

The variations in the expander inlet and outlet pressures, generator power and thermal efficiency.

Figure 5.

The energy balance of the evaporator under different mass fluxes.

As the mass flux increases, both the evaporation and condensation pressures rise, primarily due to a higher pump pressure ratio and an increased heat load resulting from the intensified refrigerant flow. Maintaining a constant expander rotational speed requires an increase in shaft resistance, which leads to higher expander output power. The rise in condensation pressure is primarily due to a slight increase in condensation temperature at constant mass flux, resulting from the higher refrigerant heat load. With increasing mass flux, both the generator power and thermal efficiency improve and remain stable under each test condition. At the same time, the evaporator heat flux increases accordingly. The energy loss represents the relative deviation between the heat transfer rates of the thermal oil and refrigerant sides, referenced to that of the thermal oil side [44]. The average energy loss was approximately 8.5%. These results indicate that the experimental setup exhibits reliable operational stability and maintains a consistent energy balance across varying operating conditions.

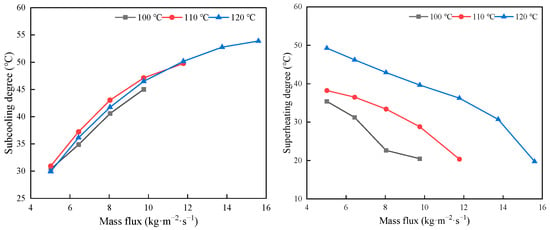

3.2. Heat Source Temperature and Mass Flux Effects

Experiments were carried out at heat source temperatures of 100 °C, 110 °C, and 120 °C, with corresponding saturation temperatures between 62.8 and 86.2 °C and mass fluxes of ranging from 5.0 to 16.6 kg/(m2·s). The corresponding heat flux ranged from 3.1 to 9.2 kW/m2. The inlet subcooling degree of the evaporator changed from 29.9 °C to 53.9 °C, while the outlet superheating degree varied between 19.7 °C and 49.3 °C. As the heat source temperature increases, a wider range of mass fluxes can be applied in the ORC system.

Figure 6 illustrates the variations in subcooling and superheating degree under these operating conditions. The subcooling degree increases with mass flux, primarily due to a slight rise in condensation temperature, while the refrigerant temperature at the evaporator inlet remains nearly constant. As a result, the operating pressure and corresponding saturation temperature increase, leading to a higher subcooling degree. In contrast, the superheating degree decreases with increasing mass flux. Under low mass flux conditions, the refrigerant outlet temperature remains relatively stable, as the working fluid can absorb sufficient heat from the heat source. However, as the mass flux increases, the heat transfer capacity of the heat source eventually becomes the limiting factor. Consequently, the reduced temperature difference between the thermal oil and the refrigerant lowers the heat transfer driving potential. This results in the refrigerant absorbing less heat, leading to a decrease in outlet temperature and a significant reduction in the superheating degree. In addition, the variation in subcooling degree across different heat source temperatures is relatively small, indicating that the condensation-side heat transfer is primarily governed by mass flux and is less sensitive to the heat source temperature. Conversely, increasing the heat source temperature significantly enhances the superheating degree. A higher temperature improves the heat exchange capacity of the evaporator, leading to an elevated refrigerant outlet temperature and an expanded superheating region, reflecting enhanced thermal performance.

Figure 6.

Variations in subcooling and superheating degrees.

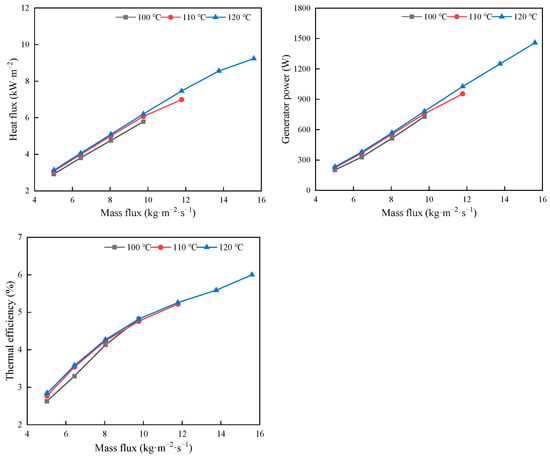

Figure 7 shows the variations in heat flux, generator power, and thermal efficiency. Since the superheating region absorbs considerably less heat than the saturated two-phase region, the overall heat flux increases only slightly with rising heat source temperature, as the superheating portion contributes minimally to the total heat transfer. Similarly, both the generator power and thermal efficiency show only minor increases with heat source temperature, whereas they rise significantly with increasing mass flux. These results indicate that optimal performance is achieved at higher heat source temperatures and mass fluxes [45]. Figure 8 shows the variations in LMTD, overall HTC, and refrigerant HTC. At low mass flux, increasing the heat source temperature leads to a rise in LMTD, which slightly reduces the overall HTC. However, at higher mass fluxes, the LMTD initially decreases and then increases as the heat source temperature rises. Accordingly, at a heat source temperature of 100 °C, the increase in overall HTC is less pronounced. However, at 110 °C with a mass flux of 9.8 kg/(m2·s) and at 120 °C with a mass flux of 13.8 kg/(m2·s), the overall HTC reaches maximum values of 338.1 and 385.0 W/(m2·K), respectively, before beginning to decrease. Similarly, the refrigerant HTC exhibits the same trend, reaching maximum values of 1286.1 W/(m2·K) at 110 °C and 1401.8 W/(m2·K) at 120 °C, before subsequently decreasing. The increase in both overall and refrigerant heat transfer coefficients is primarily attributed to enhanced convective heat transfer at higher mass fluxes, particularly within the subcooled and saturated two-phase regions. Enhanced thermal coupling between the working fluid and the heat source promotes more effective vaporization, leading to higher vapor quality and enthalpy at the expander inlet. Consequently, both generator power and thermal efficiency are significantly enhanced at higher mass fluxes and heat source temperatures.

Figure 7.

Variations in heat flux, generator power and thermal efficiency.

Figure 8.

Variations in LMTD, overall HTC and refrigerant HTC.

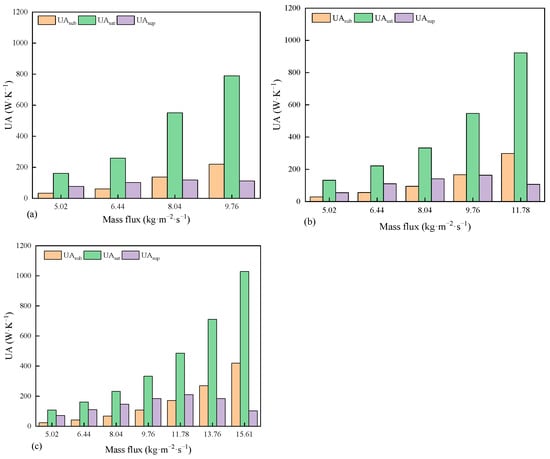

Figure 9 illustrates the variations in UA in different heat transfer regions. Among the three regions, the saturated two-phase region exhibits the highest UA. As the mass flux increases, UA in both the subcooled boiling and saturated two-phase regions rises significantly. This trend is primarily due to the sharp increase in Reynolds number with mass flux, as it is the dominant factor affecting the overall HTC [14]. By contrast, at higher mass fluxes, larger heat transfer areas are required in the subcooled and saturated regions to meet the thermal load, which consequently reduces the available area for heat exchange in the superheating region. Consequently, UA in the superheating region initially increases and then decreases, providing further explanation for the observed trend in the overall and refrigerant heat transfer coefficients. In the subcooled and saturated phases, nucleate boiling and two-phase convection are the dominant heat transfer mechanisms, while single-phase convective heat transfer primarily governs the superheating phase. This results in distinct UA characteristics for each of the three regions.

Figure 9.

Variations in UA in different regions under various heat source temperatures: (a) 100 °C, (b) 110 °C, and (c) 120 °C.

3.3. Evaluation of Prediction Methods

Model accuracy was evaluated using the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), which quantifies the average relative deviation between predicted and experimental values. MAPE is defined as follows:

where datai,pred, datai,exp and N refer to the predicted heat transfer coefficient, experience HTC and the total data number.

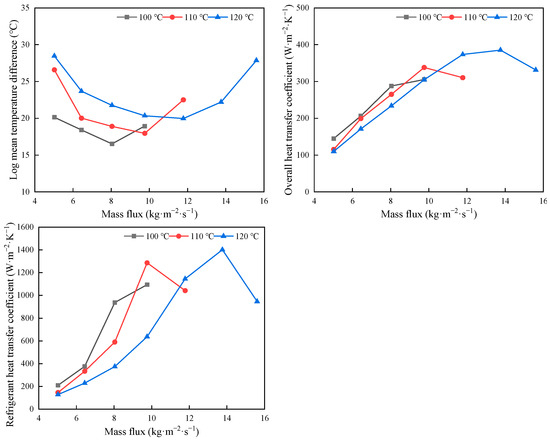

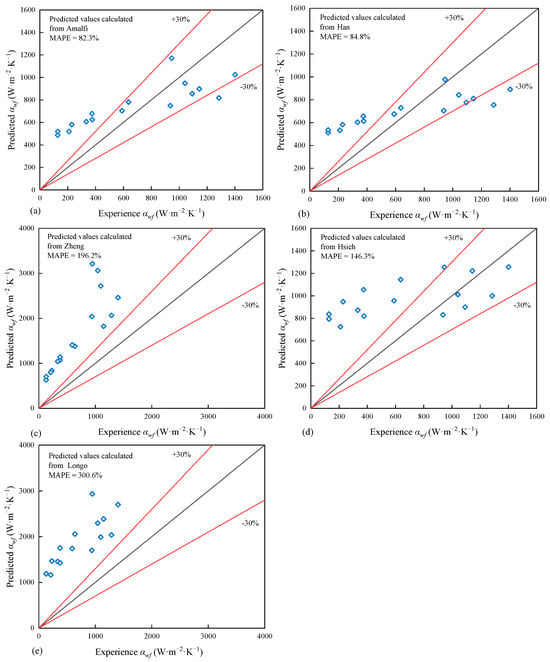

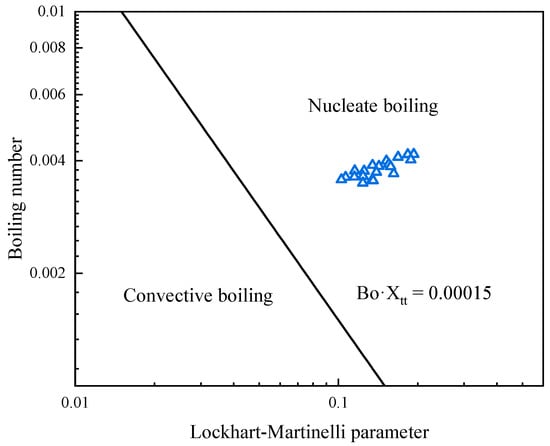

Figure 10 illustrates the comparison of predicted and experimental HTCs using the selected correlations. Among them, the methods proposed by Zheng and Longo show the poorest agreement with the experimental results, with MAPE values of 196.2% and 300.6%, respectively. None of their predicted data fall within the ±30% deviation band. Both correlations are founded on the combined effects of convective and nucleate boiling mechanisms; however, their nucleate boiling sub-models considerably overestimate the HTC. The transition between boiling regimes is quantified by the Thonon et al. [46], defined through the product of the Lockhart–Martinelli parameter (Xtt) and the Bo. When Xtt·Bo > 0.00015, nucleate boiling dominates. As illustrated in Figure 11, the application of this criterion to our experimental data reveals that all data points fall within the nucleate boiling regime. This finding provides a compelling explanation for the poor performance of the Zheng and Longo correlations.

Figure 10.

Experimental results compared to predictive results using: (a) Amalfi, (b) Han, (c) Zheng, (d) Hsieh and (e) Longo.

Figure 11.

Comparison of experimental results with the Thonon et al. [46] criterion.

The Hsieh correlation also exhibits relatively poor predictive performance, with a MAPE of 146.3%. It consistently overpredicts the HTC at low mass fluxes, with all prediction points located above the +30% deviation band, and gradually approaching the ±30% deviation band as the mass flux increases. This overestimation primarily results from the strong sensitivity of subcooled boiling HTC to refrigerant mass flux. In addition, the applicable range of the Hsieh correlation (50–200 kg/(m2·s)) is far beyond the operating conditions of this study, where the maximum mass flux is only 15.6 kg/(m2·s), leading to significant deviations. In contrast, the correlations proposed by Amalfi and Han more closely with the experimental observations, yielding MAPE values of 82.3% and 84.8%, respectively. At low mass flux conditions, all prediction points fall above the +30% deviation band, indicating a tendency toward overestimation. As the mass flux increases, the prediction points gradually shift downward and approach the −30% deviation band, suggesting increasing underestimation. This behavior reflects their dimensionless formulation, which incorporates the combined effects of the Boiling number, Reynolds number, and two-phase flow characteristics, enabling them to capture the dominant heat transfer trends observed in the experiments more effectively. Considering that the present experiments cover the subcooled boiling region, saturated two-phase region, and superheating region, the use of dimensionless correlations represents the most reasonable and applicable approach for predicting HTC in this study.

3.4. Development of a New Predictive Correlation

To develop a predictive correlation that can accurately capture heat transfer in the subcooled boiling, saturated two-phase, and superheating regions, this study adopts a modeling approach inspired by Amalfi. The method is structured into three main steps, providing a systematic framework to analyze key variables, perform non-dimensional analysis, and establish a power-law correlation for the Nusselt number (Nu).

First, the key variables influencing the HTC are systematically analyzed to establish a physically meaningful correlation. The refrigerant HTC is influenced by both the geometric configuration of the plate and the flow–thermal characteristics. By assuming that the HTC depends on these key parameters, a general physical relationship can be formulated. The resulting correlation is expressed as follows:

where ρ represents densities, u represents the superficial velocities, (ρₗ − ρᵥ)g is the gravitational term, q represents the heat flux, k represents the thermal conductivity, and the subscripts l/v refer to the liquid and vapor phases, respectively.

Second, a non-dimensional analysis is conducted to systematically relate the HTC to the key physical effects. By algebraically manipulating the governing variables, the refrigerant Nu is expressed as a function of a set of carefully selected dimensionless groups. These groups represent the combined influences of inertia, viscosity, surface tension, and latent heat associated with phase change, capturing the dominant mechanisms governing boiling heat transfer. The selected non-dimensional groups and the general form of the resulting correlation are:

Finally, a power-law model combined with multivariate regression is employed to relate the Nu to the selected dimensionless groups through a set of empirical coefficients. These coefficients are determined using the least-squares fitting method. By eliminating unnecessary dimensionless groups, a simplified yet accurate empirical correlation is obtained. The final predictive expressions for the Nu and the HTC α are shown below:

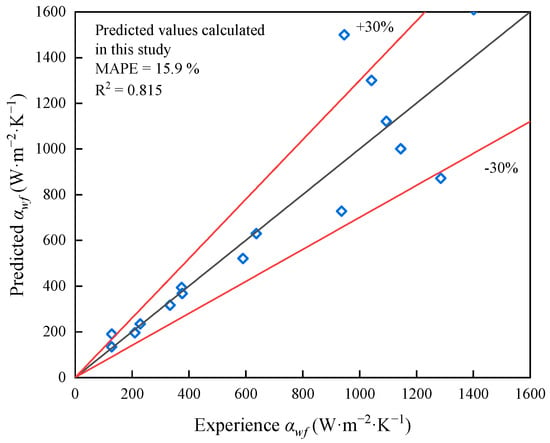

Figure 12 illustrates the comparison of predicted and experimental HTCs in this work. The results from the proposed correlation agree closely with the experimental values, particularly under low mass flux conditions, where the predictions almost perfectly match the experimental values. At higher mass flux conditions, only a few data points show relatively larger deviations, while the overall trend remains well captured. The MAPE is 15.9%, and the coefficient of determination is 0.815, indicating that the developed correlation accurately captures the refrigerant heat transfer characteristics across all three regions. Therefore, this correlation provides a reliable theoretical basis for performance prediction, system optimization, and subsequent design improvements.

Figure 12.

Comparison of predicted and experimental HTCs in this study.

4. Conclusions

This study experimentally analyzed the heat transfer behavior of refrigerant within the evaporator of an organic Rankine cycle (ORC) system. Experiments were conducted under various operating conditions, including heat source temperatures of 100, 110, and 120 °C, with corresponding saturation temperatures ranging from 62.8 to 86.2 °C. The experiments covered a range of mass fluxes (5.0–16.6 kg/(m2·s)), heat fluxes (3.1–9.2 kW/m2), inlet subcooling degrees (29.9–53.9 °C), and outlet superheating degrees (19.7–49.3 °C). Along the flow path of the evaporator, the refrigerant experienced subcooled boiling, saturated two-phase boiling, and superheating processes. The following conclusions can be drawn:

- (1)

- The heat flux exhibited only a slight increase with rising heat source temperature because the heat absorbed in the superheating region was relatively limited compared with that in the saturated two-phase region. In contrast, both generator power and thermal efficiency increased significantly with mass flux, primarily due to enhanced convection and greater refrigerant circulation through the subcooled and saturated two-phase regions. This enhancement promoted more efficient vaporization, resulting in higher vapor quality and enthalpy at the expander inlet, improving system performance.

- (2)

- Both the overall and refrigerant heat transfer coefficients increased with rising mass flux and heat source temperature, reaching peak values under moderate conditions. This trend is primarily attributed to intensified convective boiling and improved thermal coupling between the heat source and the refrigerant. With a further rise in mass flux, the heat transfer area demand increased within the subcooled and saturated two-phase regions, leading to insufficient energy exchange in the superheated region and consequently lowering the heat transfer coefficients.

- (3)

- The correlations proposed by Zheng, Longo, and Hsieh showed considerable discrepancies, particularly overestimating the heat transfer coefficient under nucleate boiling conditions. In contrast, the dimensionless correlations proposed by Amalfi and Han demonstrated higher predictive accuracy, although they tend to slightly overestimate at lower mass fluxes and underestimate at higher mass fluxes.

- (4)

- A unified predictive correlation, applicable to the subcooled boiling, saturated two-phase, and superheating regions, was developed using nondimensional analysis combined with multivariate regression. The resulting correlation yielded a mean absolute percentage error of 15.9%, demonstrating its ability to accurately capture the heat transfer characteristics across all regions of the evaporator. This correlation provides a reliable theoretical basis for performance prediction, and system optimization of evaporators of ORC systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C.; methodology, C.W. and H.S.; software, Y.C.; validation, Y.C., C.W. and J.Z.; formal analysis, Y.C.; investigation, J.Z.; resources, J.Z.; data curation, Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.C.; writing—review and editing, Y.C.; visualization, C.W.; supervision, C.W. and H.S.; project administration, J.Z.; funding acquisition, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council [grant number EP/Y022149/1]. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a ‘Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY)’ license to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Hideyuki Sakai was employed by the company Pure Energy Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ORC | Organic Rankine cycle |

| PHE | Plate heat exchanger |

| HTC | Heat transfer coefficient |

| LMTD | Log mean temperature difference |

| Re | Reynolds number |

| Pr | Prandtl number |

| Bd | Bond number |

| Bo | Boiling number |

| Fr | Froude number |

| Ja | Jakob number |

| Nu | Nusselt number |

| MAPE | Mean absolute percentage error |

References

- Liu, G.; Ji, D.; Markides, C.N. Progress and prospects of low-grade thermal energy utilization technologies. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 254, 123859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obiora, S.C.; Bamisile, O.; Hu, Y.; Ozsahin, D.U.; Adun, H. Assessing the decarbonization of electricity generation in major emitting countries by 2030 and 2050: Transition to a high share renewable energy mix. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, C.; Muritala, I.K.; Pardemann, R.; Meyer, B. Estimating the global waste heat potential. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 1568–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Han, U.; Jung, Y.; Kang, Y.T.; Lee, H. Advancing waste heat potential assessment for net-zero emissions: A review of demand-based thermal energy systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 202, 114693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecompte, S.; Huisseune, H.; van den Broek, M.; Vanslambrouck, B.; De Paepe, M. Review of organic Rankine cycle (ORC) architectures for waste heat recovery. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, G.; Li, L.; Yang, Q.; Tang, B.; Liu, Y. Expansion devices for organic Rankine cycle (ORC) using in low temperature heat recovery: A review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 199, 111944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Shu, G.; Tian, H.; Deng, S. A review of modified Organic Rankine cycles (ORCs) for internal combustion engine waste heat recovery (ICE-WHR). Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 92, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, C.; Wang, S.; Xu, X.; Li, Q. Thermo-economic comparison of subcritical organic Rankine cycle based on different heat exchanger configurations. Energy 2017, 123, 728–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, J.; Chowdhury, K. Appropriate number of stages of an ORC driven by LNG cold energy to produce acceptable power with reasonable surface area of heat exchangers. Cryogenics 2022, 128, 103599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Xu, J.; Chen, H. A new design method for Organic Rankine Cycles with constraint of inlet and outlet heat carrier fluid temperatures coupling with the heat source. Appl. Energy 2012, 98, 562–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoilin, S.; Broek, M.V.D.; Declaye, S.; Dewallef, P.; Lemort, V. Techno-economic survey of Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 22, 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, O.; Abadi, G.B.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, K.C. Experimental study of the effect of brazed compact metal-foam evaporator in an organic Rankine cycle performance: Toward a compact ORC. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 173, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Kim, D.; Yun, S.; Kim, Y. Two-phase flow patterns and pressure drop of a low GWP refrigerant R-1234ze(E) in a plate heat exchanger under adiabatic conditions. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 145, 118816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Luo, X.; Luo, J.; Chen, J.; Liang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H. Experimental investigation of operation behavior of plate heat exchangers and their influences on organic Rankine cycle performance. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 207, 112528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Lu, P.; Chen, K.; Luo, X.; Chen, J.; Liang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Y. Experimental and simulation investigation on the heat exchangers in an ORC under various heat source/sink conditions. Energy 2023, 264, 126189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peris, B.; Navarro-Esbrí, J.; Mateu-Royo, C.; Mota-Babiloni, A.; Molés, F.; Gutiérrez-Trashorras, A.J.; Amat-Albuixech, M. Thermo-economic optimization of small-scale Organic Rankine Cycle: A case study for low-grade industrial waste heat recovery. Energy 2020, 213, 118898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hu, X.; Wu, D.; Huang, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Wen, C. A comparative study on design and performance evaluation of Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) under different two-phase heat transfer correlations. Appl. Energy 2023, 350, 121724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.Y.; Chiang, L.J.; Lin, T.F. Subcooled flow boiling heat transfer of R-134a and the associated bubble characteristics in a vertical plate heat exchanger. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2002, 45, 1791–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, B.; Thome, J.R.; Fabbri, M.; Michel, B.; Calmi, D.; Kloter, U. High heat flux flow boiling in silicon multi-microchannels—Part II: Heat transfer characteristics of refrigerant R245fa. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2008, 51, 5415–5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Usman, M.; Yang, Y.; Park, B.-S. Flow boiling of R245fa in the brazed plate heat exchanger: Thermal and hydraulic performance assessment. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2017, 110, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, G.A.; Mancin, S.; Righetti, G.; Zilio, C. A new model for refrigerant boiling inside Brazed Plate Heat Exchangers (BPHEs). Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2015, 91, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, G.A.; Mancin, S.; Righetti, G.; Zilio, C. Hydrocarbon refrigerants boiling local heat transfer coefficients inside a Brazed Plate Heat Exchanger (BPHE). Int. J. Refrig. 2023, 156, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, J.; Haglind, F. An experimental study of flow boiling heat transfer and pressure drop of hydrofluoroolefin and hydrocarbon mixtures in a plate heat exchanger. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2025, 212, 109762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaranatha Raju, M.; Ashok Babu, T.P.; Ranganayakulu, C. Investigation of flow boiling heat transfer and pressure drop of R134a in a rectangular channel with wavy fin. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2020, 147, 106055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, W.-C.; Fang, Y.-D.; Chen, Q.-H.; Xu, L.-J.; Yang, H.-N.; Huang, Y.-Q. Experimental investigation on the flow boiling of R134a in a plate heat exchanger with mini-wavy corrugations. Int. J. Refrig. 2024, 162, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, G.A.; Mancin, S.; Righetti, G.; Zilio, C. Local heat transfer coefficients of R32 and R410A boiling inside a brazed plate heat exchanger (BPHE). Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 215, 118930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Desideri, A.; Kærn, M.R.; Ommen, T.S.; Wronski, J.; Haglind, F. Flow boiling heat transfer and pressure drop characteristics of R134a, R1234yf and R1234ze in a plate heat exchanger for organic Rankine cycle units. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2017, 108, 1787–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desideri, A.; Zhang, J.; Kærn, M.R.; Ommen, T.S.; Wronski, J.; Lemort, V.; Haglind, F. An experimental analysis of flow boiling and pressure drop in a brazed plate heat exchanger for organic Rankine cycle power systems. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2017, 113, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Kærn, M.R.; Kabelac, S.; Haglind, F. Experimental analysis of quasi-local non-equilibrium boiling heat transfer with the refrigerants R1234ze(E) and R1234yf in a gasketed plate heat exchanger. Int. J. Refrig. 2025, 170, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-C.; Feng, Y.-Q.; Shuai, Y.; Lai, J.-H.; Leung, M.K.H.; Wei, Y.; Hsu, H.-Y.; Hung, T.-C. Experimental validation of a 0.3 kW ORC for the future purposes in the study of low-grade thermal to power conversion. Energy 2023, 285, 129422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Hsu, P.-P.; He, Y.-L.; Shuai, Y.; Hung, T.-C.; Feng, Y.-Q.; Chang, Y.-H. Investigations on experimental performance and system behavior of 10 kW organic Rankine cycle using scroll-type expander for low-grade heat source. Energy 2019, 177, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo Noguera, A.L.; Mendoza Castellanos, L.S.; Pedraza-Corzo, H.D.; Rua, D.J.; Silva Lora, E.E.; Melian Cobas, V.R. Comprehensive methodology for the integrating of the organic rankine Cycle-ORC with diesel generators in off-grid areas: Application to a Colombian case study. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2024, 23, 100828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatigati, F.; Coletta, A.; Di Bartolomeo, M.; Cipollone, R. The dynamic behaviour of ORC-based power units fed by exhaust gases of internal combustion engines in mobile applications. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 240, 122215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, H. A theoretical approach to predict the performance of chevron-type plate heat exchangers. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 1996, 35, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yuan, Z.; Li, W.; Yang, J.; Zhu, J. Strengthening mechanisms of two-stage evaporation strategy on system performance for organic Rankine cycle. Energy 2016, 101, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Huang, R.; Yang, Z.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y. Performance investigation of a novel zeotropic organic Rankine cycle coupling liquid separation condensation and multi-pressure evaporation. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 161, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, R.J. Describing the uncertainties in experimental results. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 1988, 1, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalfi, R.L.; Vakili-Farahani, F.; Thome, J.R. Flow boiling and frictional pressure gradients in plate heat exchangers. Part 2: Comparison of literature methods to database and new prediction methods. Int. J. Refrig. 2016, 61, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.-H.; Lee, K.-J.; Kim, Y.-H. Experiments on the characteristics of evaporation of R410A in brazed plate heat exchangers with different geometric configurations. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2003, 23, 1209–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gungor, K.E.; Winterton, R.H.S. A general correlation for flow boiling in tubes and annuli. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1986, 29, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.C. Correlation for Boiling Heat Transfer to Saturated Fluids in Convective Flow. Ind. Eng. Chem. Process Des. Dev. 1966, 5, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittus, F.W.; Boelter, L.M.K. Heat transfer in automobile radiators of the tubular type. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 1985, 12, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.G. Saturation Nucleate Pool Boiling—A Simple Correlation. In First U.K. National Conference on Heat Transfer; Simpson, H.C., Hewitt, G.F., Boland, D., Bott, T.R., Furber, B.N., Hall, W.B., Heggs, P.J., Rowe, P.N., Saunders, E.A.D., Spalding, D.B., Eds.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1984; pp. 785–793. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Haglind, F. Experimental analysis of high temperature flow boiling heat transfer and pressure drop in a plate heat exchanger. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 196, 117269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-F.; Li, M.-J.; Ren, X.; Duan, X.-Y.; Wu, C.-J.; Xi, H.; Feng, Y.-Q.; Gong, L.; Hung, T.-C. Effect of heat source supplies on system behaviors of ORCs with different capacities: An experimental comparison between the 3 kW and 10 kW unit. Energy 2022, 254, 124267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thonon, B.; Vidil, R.; Marvillet, C. Recent Research and Developments in Plate Heat Exchangers. J. Enhanc. Heat Transf. 1995, 2, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).