Annual Flow Balance of a Naturally Ventilated Room with a Façade Opening Covered by Openwork Grating

Abstract

1. Introduction

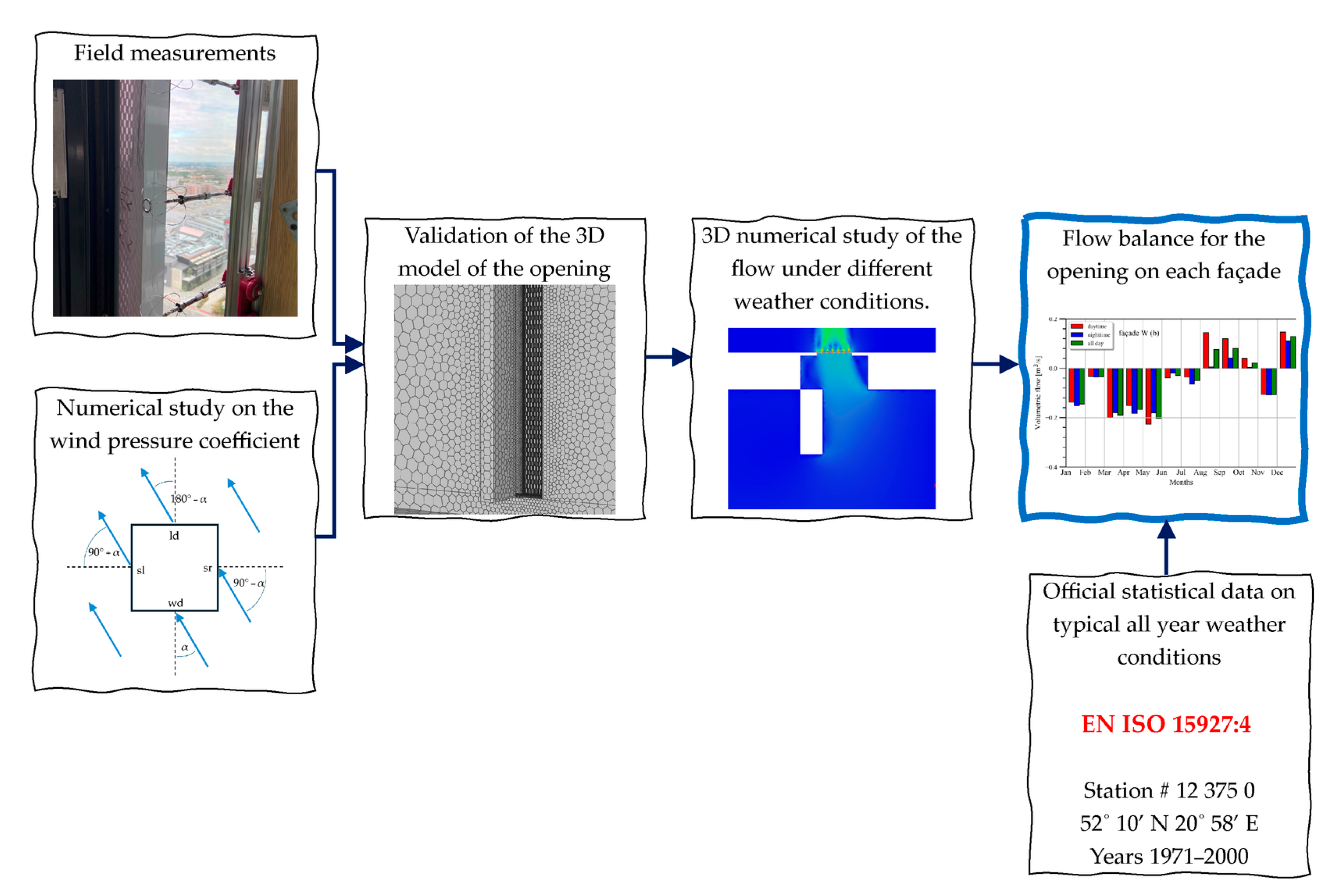

2. Materials and Methods

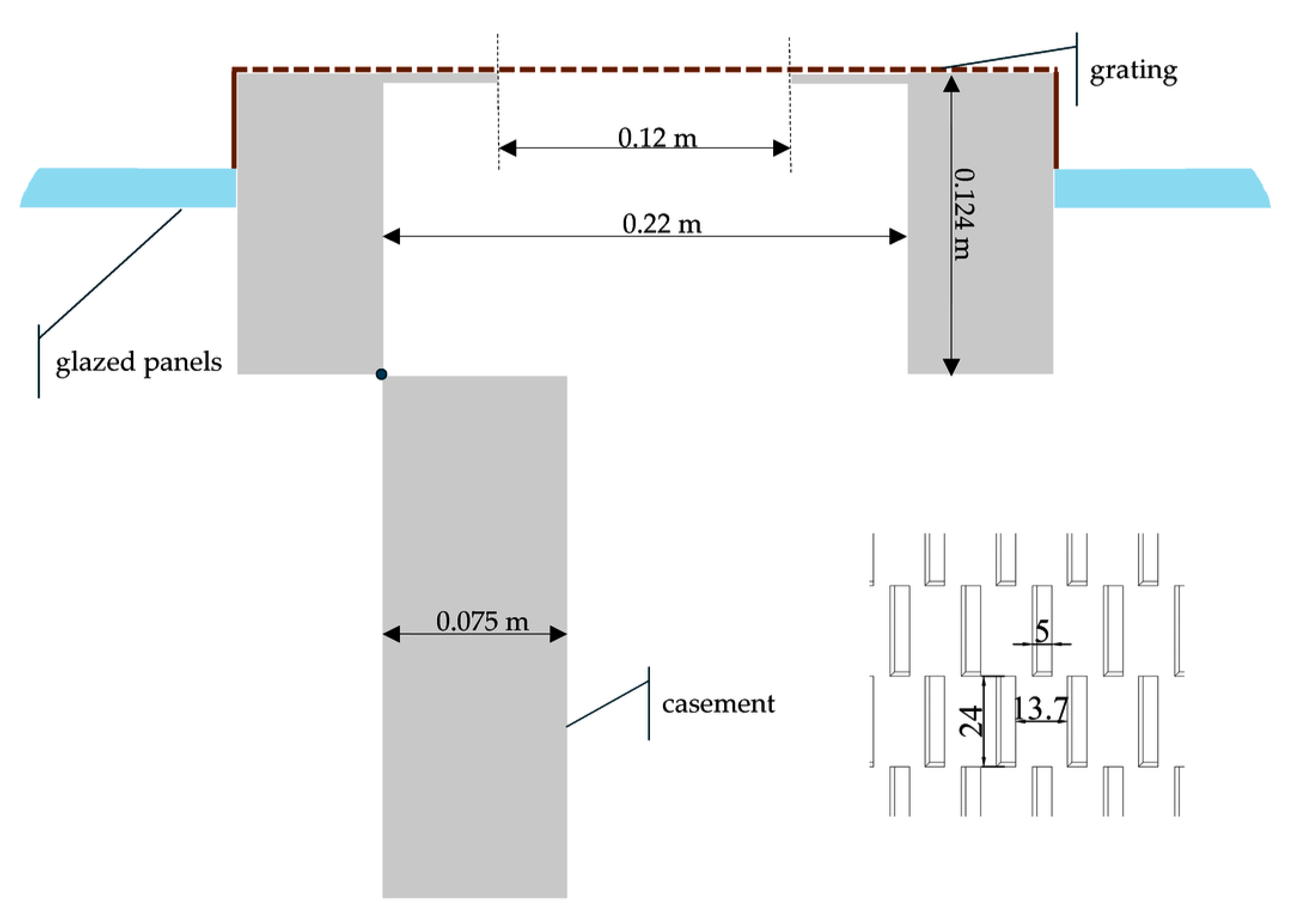

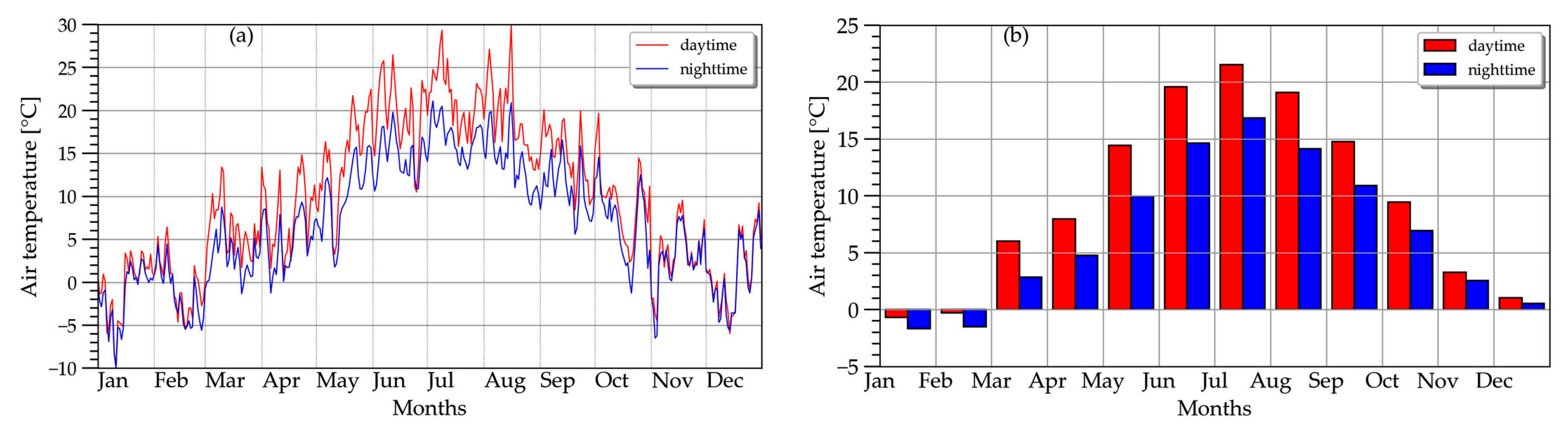

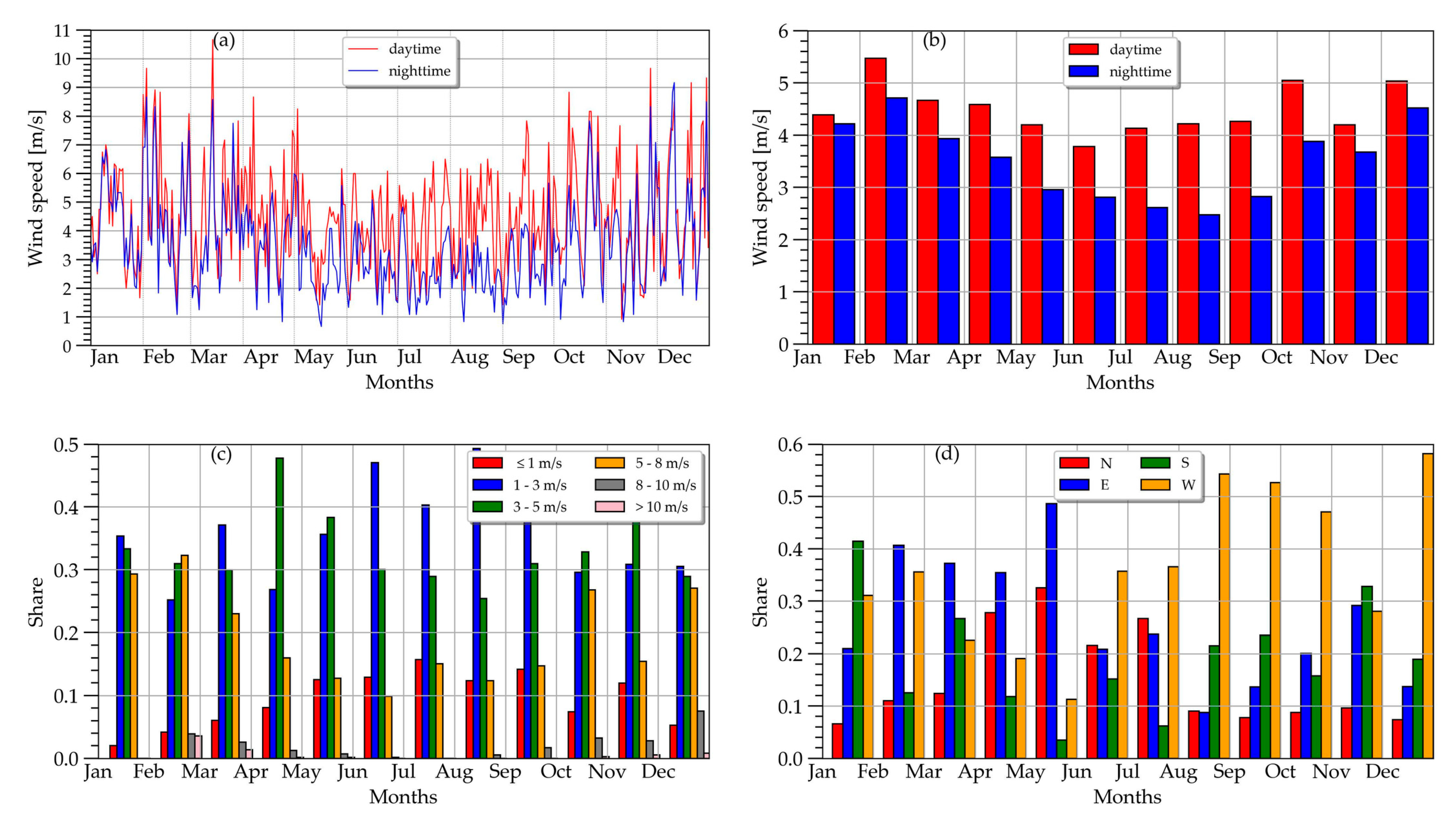

2.1. Experiment Description

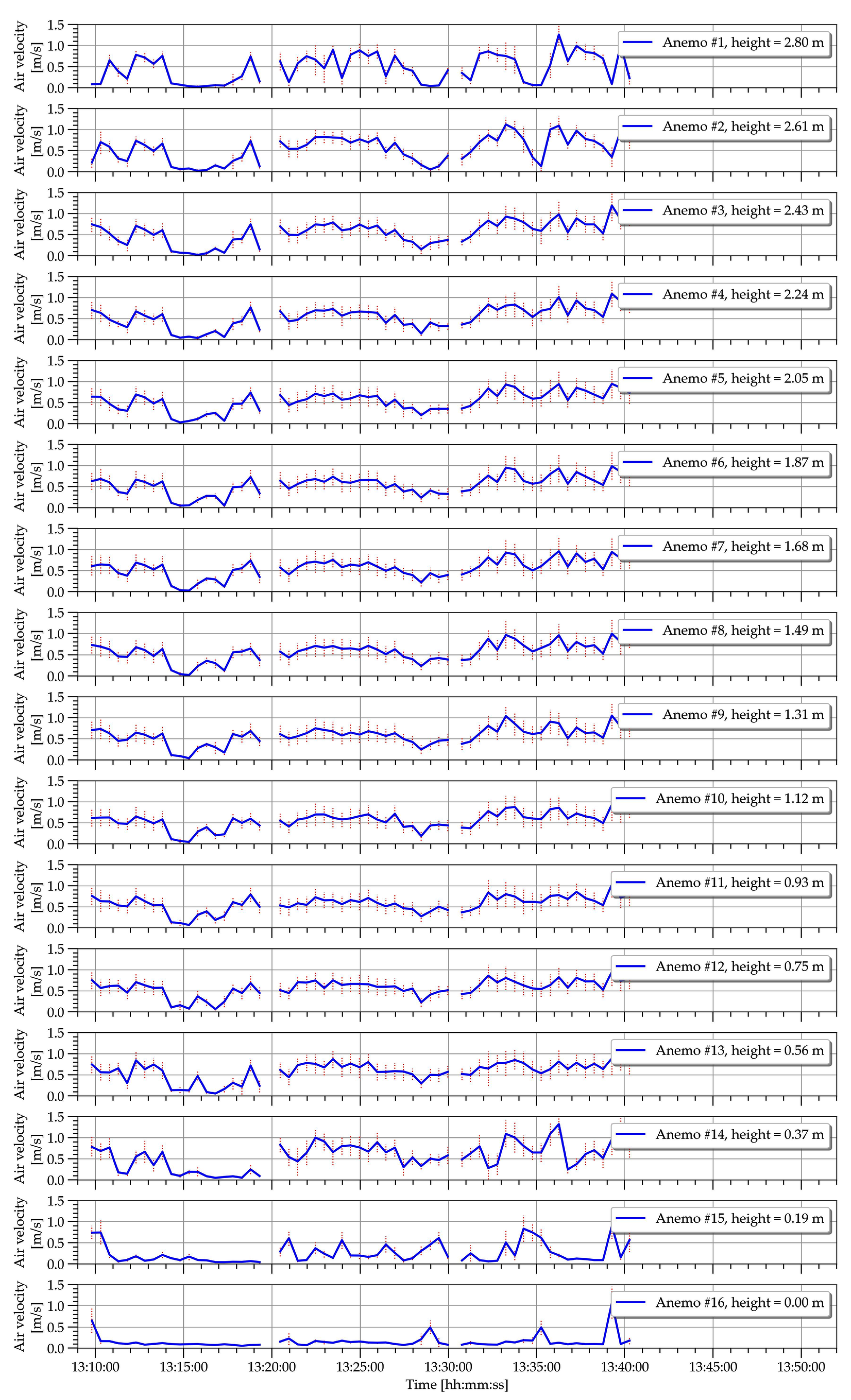

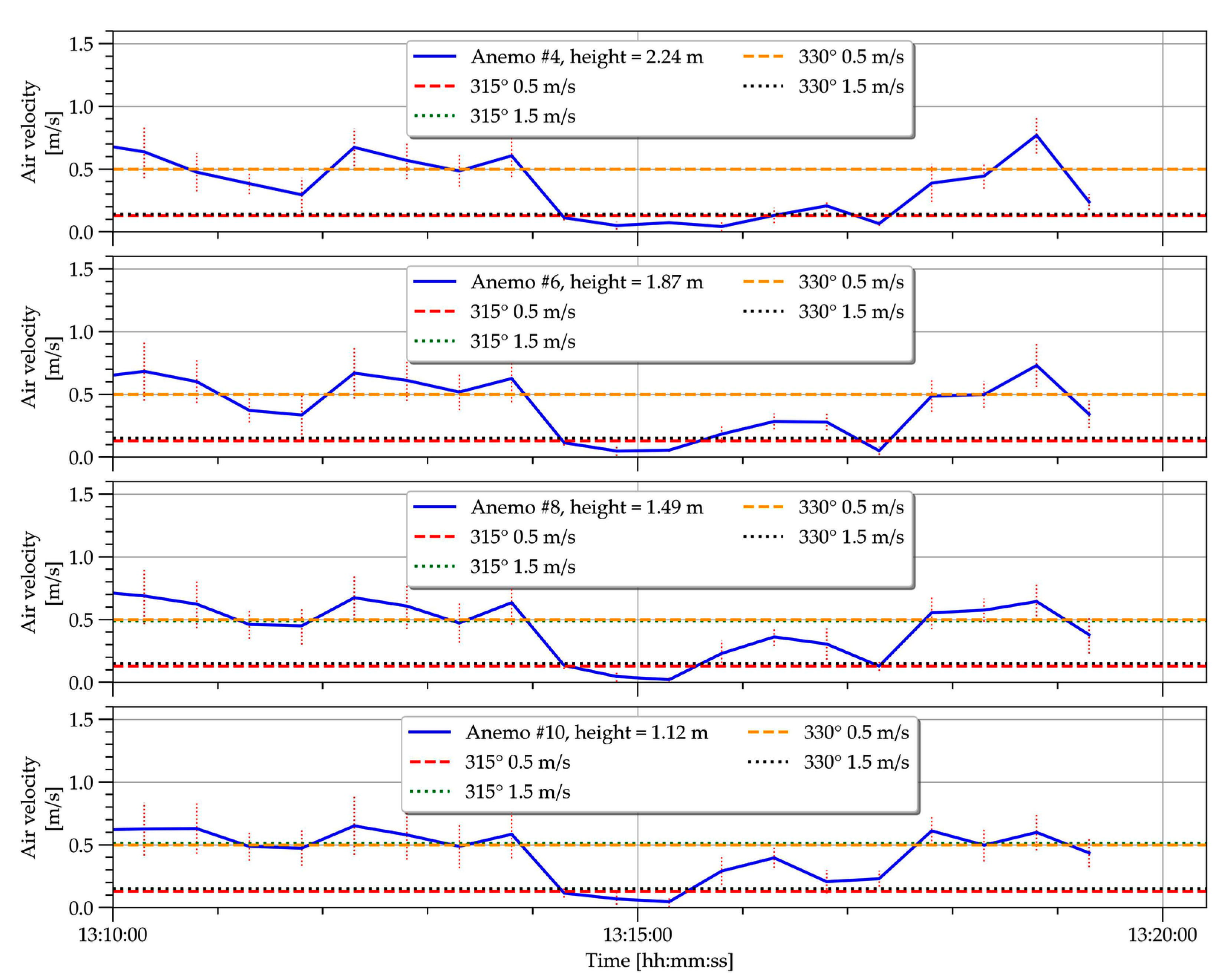

2.2. Experimental Data

2.3. Interpretation of the Experimental Data

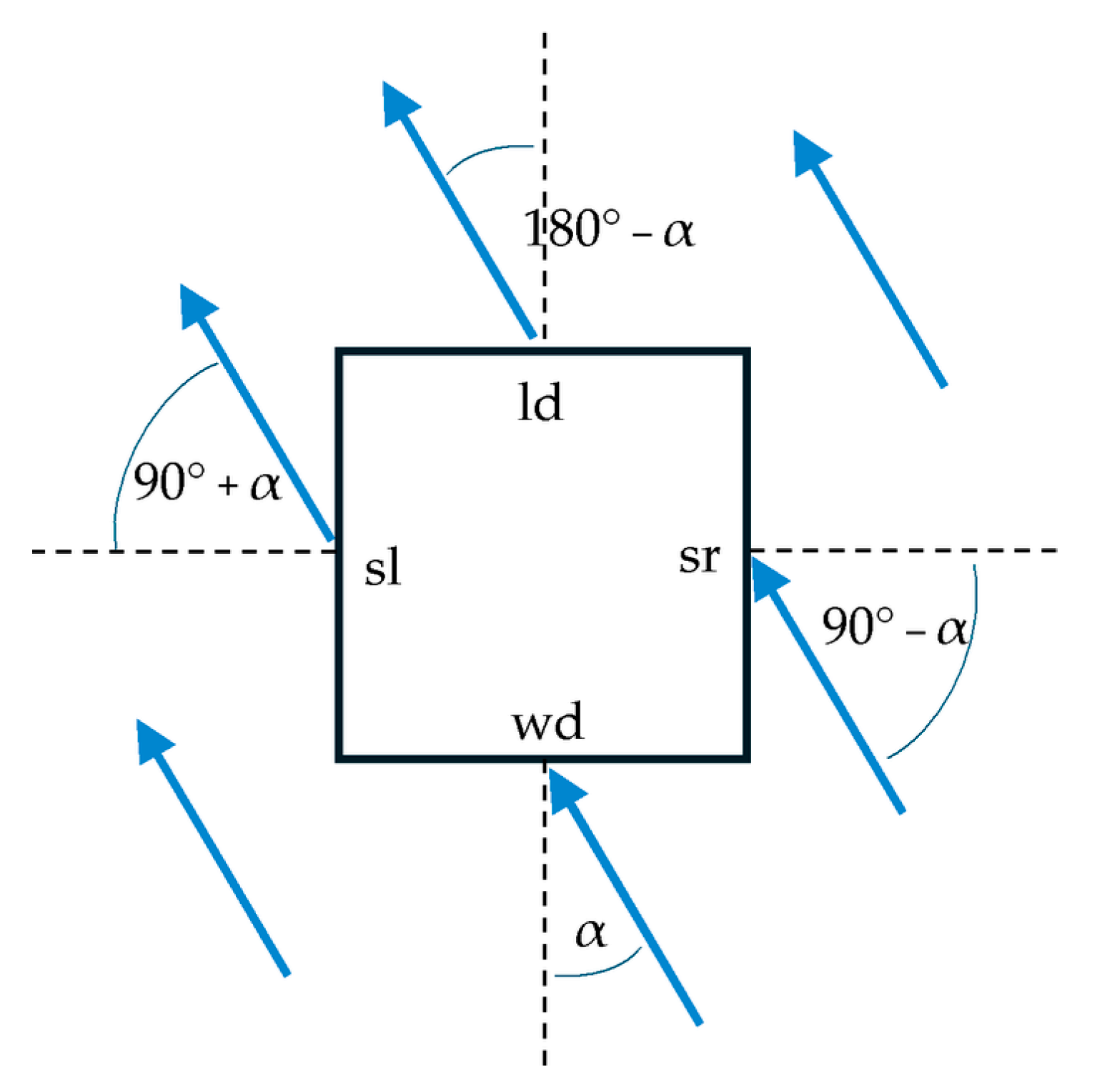

2.4. The Numerical Model of the Opening

- The first submodel was applied when the wind blew onto the examined façade at a relatively small angle, corresponding to positive values of the pressure coefficient. This submodel also included a volume corresponding to the building exterior. This structure allowed for an accurate reproduction of the wind’s impact on the elements of the window opening. In the considered weather data, the wind velocity ranged up to 15 m/s, so values of 1, 5, 10, and 15 m/s were examined. Due to the opening’s asymmetry, the inflow angle was varied from −55 to 55° in 5° increments.

- The second submodel was used for cases with negative values of the pressure coefficient. It was simplified, and the wind effect was modeled by applying a relevant negative pressure value on a plane near the façade surface (not shown in Figure 12, because the exact position of the pressure plane did not affect the results). This approach was appropriate because, for a façade with negative wind pressure, the airflow due to the wind is residual, and the air velocity near the opening is very low. Only the suction effects are important in this case, so using such a submodel speeds up the calculations. The negative pressure varied from −1 to −250 Pa, with incremental spacing, corresponding to a square dependence between air velocity and pressure.

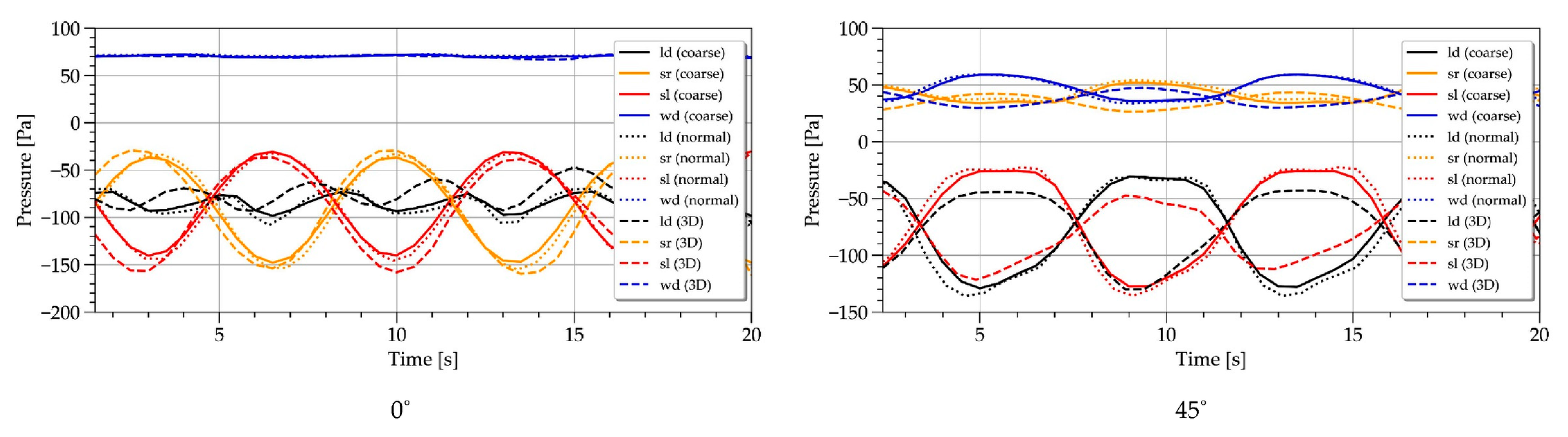

2.5. Mesh Sensitivity Analysis

2.6. Model Validation

3. The Performance Characteristics of the Opening

4. Results and Discussion—The Annual Flow and Energy Balance

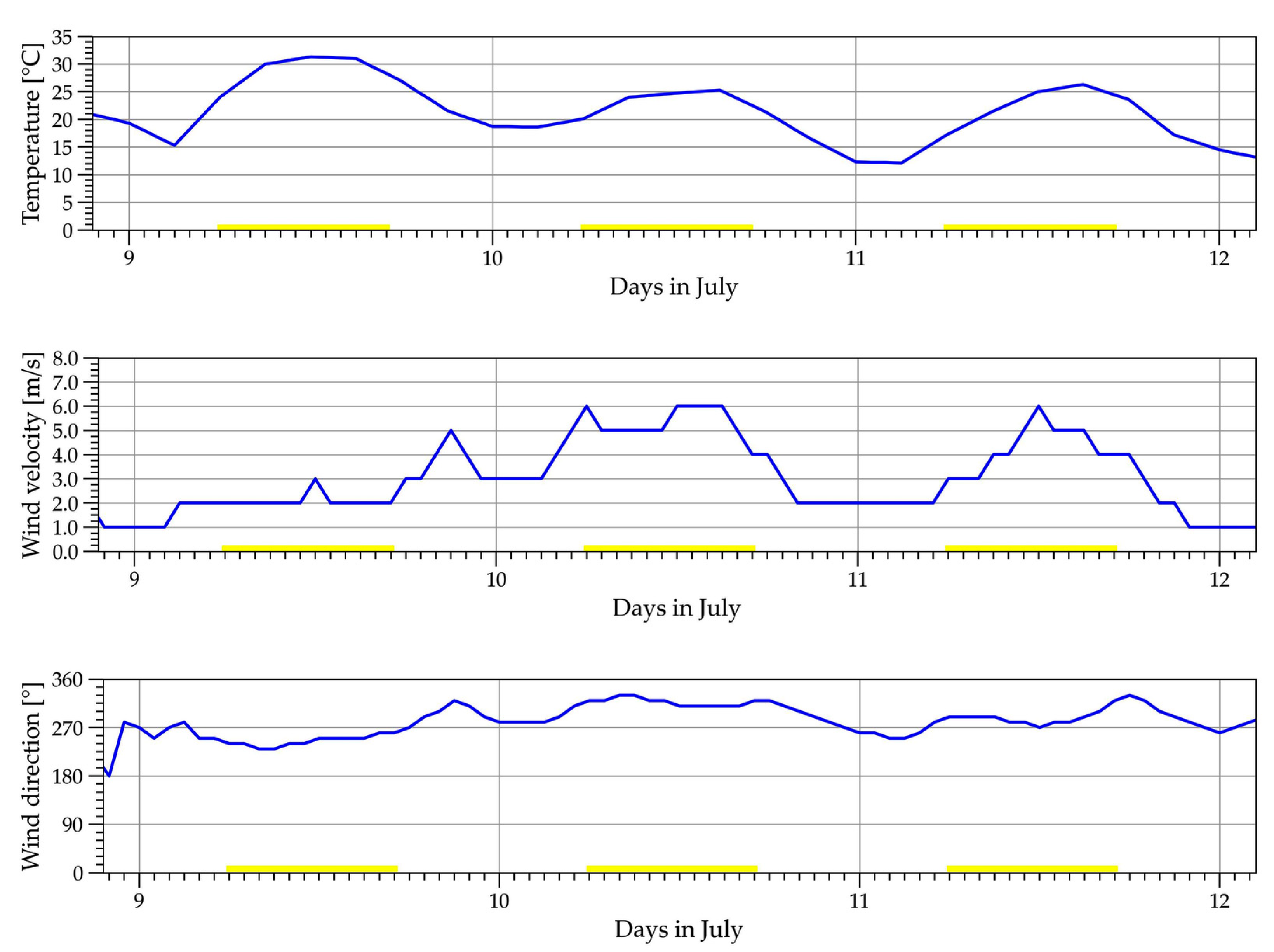

4.1. Flow Balance

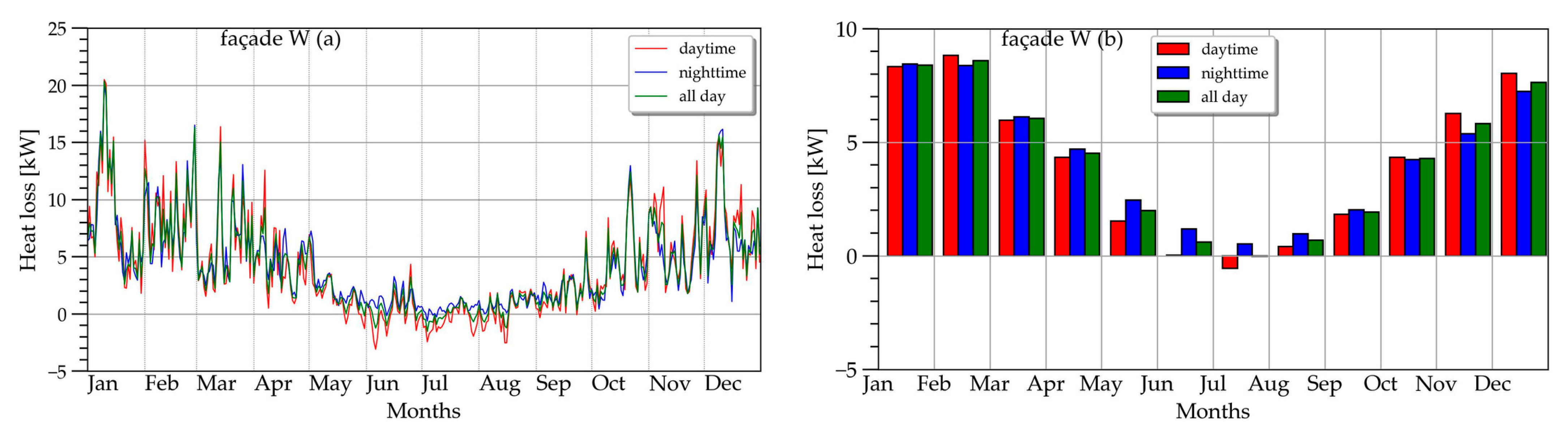

4.2. Heat Loss Balance

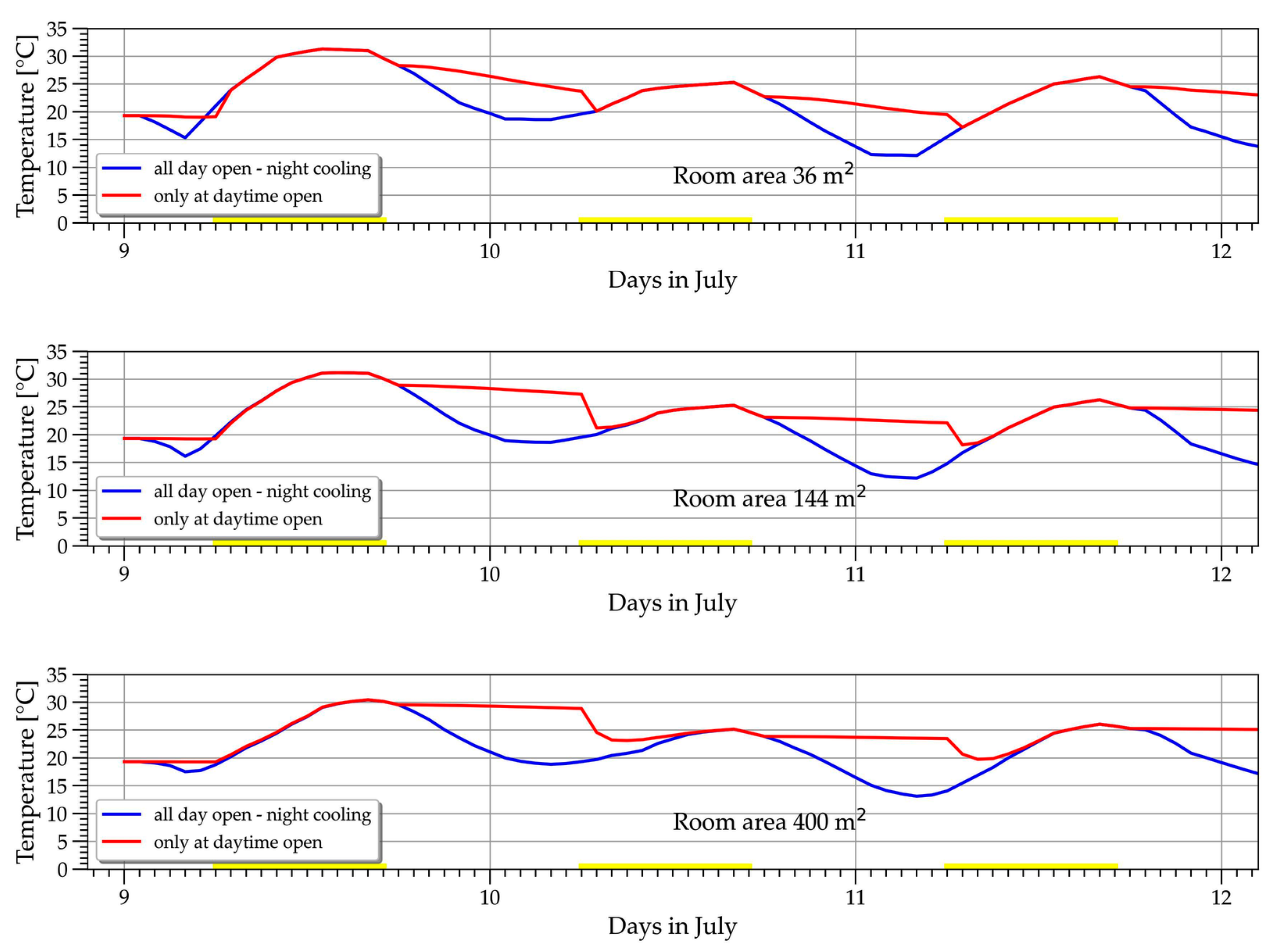

4.3. Estimation of the Night Cooling Potential

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paone, A.; Bacher, J.-P. The Impact of Building Occupant Behavior on Energy Efficiency and Methods to Influence It: A Review of the State of the Art. Energies 2018, 11, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoure, A.N.; Genovese, P.V. Implementing natural ventilation and daylighting strategies for thermal comfort and energy efficiency in office buildings in Burkina Faso. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 3319–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Meena, C.S.; Raj, B.P.; Saini, L.; Kumar, A.; Gopalakrishnan, N.; Kumar, A.; Balam, N.B.; Alam, T.; Kapoor, N.R.; et al. Indoor air quality improvement in COVID-19 pandemic: Review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 70, 102942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seinre, E.; Kurnitski, J.; Voll, H. Building sustainability objective assessment in Estonian context and a comparative evaluation with LEED and BREEAM. Build. Environ. 2014, 82, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Muhieldeen, M.W.; Razman, R.; Ee, J.Y.C.; Chiong, M.C. The potential effects of window configuration and interior layout on natural ventilation buildings: A comprehensive review. Cleaner Eng. Technol. 2024, 23, 100830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, G.A.; Sinha, S.L.; Verma, T.N.; Dewangan, S.K. Energy consumption and thermal comfort assessment using CFD in a naturally ventilated indoor environment under different ventilations. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 50, 102557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawendi, S.; Gao, S. Impact of windward inlet-opening positions on fluctuation characteristics of wind-driven natural cross ventilation in an isolated house using LES. Int. J. Vent. 2018, 17, 93–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elghamry, R.; Hassan, H. Impact of window parameters on the building envelope on the thermal comfort, energy consumption and cost and environment. Int. J. Vent. 2020, 19, 233–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Mak, C.M. Effects of different wind directions on ventilation of surrounding areas of two generic building configurations in Hong Kong. Indoor Built Environ. 2021, 31, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Kikumoto, H.; Ooka, R. Effect of wind direction on natural ventilation in a multiple-room house via field measurements and numerical simulations. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2024, 248, 105718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Lee, W.L. Influence of window opening degree on natural ventilation performance of residential buildings in Hong Kong. Sci. Technol. Built Environ. 2020, 26, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, K.R.; Rong, L.; Zhang, G.; Abkar, M. Comparison of analysis methods for wind-driven cross ventilation through large openings. Build. Environ. 2019, 154, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Weerasuriya, A.U.; Wang, J.; Li, C.Y.; Chen, Z.; Tse, K.T.; Hang, J. Cross-ventilation of a generic building with various configurations of external and internal openings. Build. Environ. 2022, 207, 108447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, A.; Król, M. Experimental and numerical research on the solar updraft at a tall building façade. Build. Environ. 2023, 240, 110466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiques, M.; Tarragona, J.; Gangolells, M.; Casals, M. Energy implications of meeting indoor air quality and thermal comfort standards in Mediterranean schools using natural and mechanical ventilation strategies. Energy Build. 2025, 328, 115076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfeh, M.K.; Sohankar, A.; Shahsavari, A.R.; Rastan, M.R.; Ghodrat, M.; Nili, M. Experimental and numerical evaluation of wind-driven natural ventilation of a curved roof for various wind angles. Build. Environ. 2021, 205, 108275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aflaki, A.; Mahyuddin, N.; Mahmoud, Z.A.-C.; Baharum, M.R. A review on natural ventilation applications through building façade components and ventilation openings in tropical climates. Energy Build. 2015, 101, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein-Montalvo, L.; Ding, L.; Hultmark, M.; Adriaenssens, S.; Bou-Zeid, E. Kirigami-inspired wind steering for natural ventilation. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2024, 246, 105667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziarani, N.N.; Cook, M.J.; O’Sullivan, P.D. Experimental evaluation of airflow guiding components for wind-driven single-sided natural ventilation: A comparative study in a test chamber. Energy Build. 2023, 300, 113627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahpour, M.; Naeini, H.G.; Mirzaei, P.A. Generic geometrical parametric study of wind-driven natural ventilation to improve indoor air quality and air exchange in offices. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramponi, R.; Angelotti, A.; Blocken, B. Energy saving potential of night ventilation: Sensitivity to pressure coefficients for different European climates. Appl. Energy 2014, 123, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Sandberg, M.; Fujita, T.; Lim, E.; Umemiya, N. Numerical analysis of wind-induced natural ventilation for an isolated cubic room with two openings under small mean wind pressure difference. Build. Environ. 2022, 226, 109694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Luo, Z.; Grimmond, S.; Blunn, L. Use of wind pressure coefficients to simulate natural ventilation and building energy for isolated and surrounded buildings. Build. Environ. 2023, 230, 109951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mise, D.; Irrenfried, C.; Meile, W.; Brenn, G.; Kozmar, H. Wind-driven natural ventilation of cubic buildings in rural and suburban areas. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 87, 108740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yuan, X.; Yang, W.; Chan, M.; Tian, L. Impact of outdoor particulate matter 2.5 pollution on natural ventilation energy saving potential in office buildings in China. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, T.; Waring, M.S. Impact of natural versus mechanical ventilation on simulated indoor air quality and energy consumption in offices in fourteen U.S. cities. Build. Environ. 2016, 104, 320–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, X.; Yang, J.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Xu, F. Indoor PM2.5 and building energy consumption in nine typical residential neighborhoods in Nanjing under different ventilation strategies caused by traffic-related PM2.5 dispersion. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 95, 110168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienvenido-Huertas, D.; Sanchez-García, D.; Rubio-Bellido, C. Analyzing natural ventilation to reduce the cooling energy consumption and the fuel poverty of social dwellings in coastal zones. Appl. Energy 2020, 279, 115845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, Y. A multi-factor optimization method based on thermal comfort for building energy performance with natural ventilation. Energy Build. 2023, 285, 112893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Wei, J.; Lau, S.-K.; Gu, Z.; Leng, J. A two-level optimization approach for underground natural ventilation based on CFD and building energy simulations. Energy Build. 2024, 310, 114102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Chen, Y.; Malkawi, A.; Liu, Z.; Freeemen, R.B. Energy saving potential of natural ventilation in China: The impact of ambient air pollution. Appl. Energy 2016, 179, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tognon, G.; Marigo, M.; De Carli, M.; Zarrella, A. Mechanical, natural and hybrid ventilation systems in different building types: Energy and indoor air quality analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salihi, M.; Chhiti, Y.; Fiti, M.E.; Harmen, Y.; Chebak, A.; Jama, C. Enhancement of buildings energy efficiency using passive PCM coupled with natural ventilation in the Moroccan climate zones. Energy Build. 2024, 315, 114322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hu, Z.; Ge, F.; Liu, X. Analysis of cooling performance and energy consumption of nocturnal radiation and natural ventilation combined mechanical refrigeration system for outdoor prefabricated substation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 230, 120650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdari, M.; Dennis, K.; Gharabaghi, B.; Siddiqui, K.; Aliabadi, A.A. Implications of latent and sensible building energy loads using natural ventilation. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasi, R.; Ruggiero, F.; Berardi, U. Natural ventilation effectiveness in low-income housing to challenge energy poverty. Energy Build. 2024, 304, 113836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tong, Z.; Malkawi, A. Investigating natural ventilation potentials across the globe: Regional and climatic variations. Build. Environ. 2017, 122, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalam, N.Z.; Farrokhzad, M.; Nazif, H. Investigation of optimal natural ventilation in residential complexes design for temperate and humid climates. Sustain. Energy 2021, 27, 100500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, A.C.O.; Filho, C.R.A.; Souza, R.V.G. The potential of mixed-mode ventilation in office buildings in mild temperate climates: An energy benchmarking analysis. Energy Build. 2023, 297, 113445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, R.; Ma, Z.; Ning, H.; Cao, J. Exploring the natural ventilation potential of urban climate for high-rise buildings across different climatic zones. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 475, 143722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamdad, K.; Matour, S.; Izadyar, N.; Law, T. Introducing extended natural ventilation index for buildings under the present and future changing climates. Build. Environ. 2022, 226, 109688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, A.C.O.; Souza, R.V.G. Climate change impact on energy savings in mixed-mode ventilation office buildings in Brazil. Energy Build. 2024, 318, 114418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, M.; Król, A.; Koper, P.; Bielawski, J.; Krajewski, G.; Węgrzyński, W. Wind driven natural flow through the different types of openings on the façade—An experimental investigation. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 71, 106491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popiołek, Z.; Melikov, A.K.; Jorgensen, F.E.; Finkelstein, W.; Sefker, T. Impact of natural convection on the accuracy of low-velocity measurements by thermal anemometers with omnidirectional sensor. ASHRAE Trans. 1998, 104, 1507–1518. [Google Scholar]

- Awbi, H.B. Ventilation of Buildings, 2nd ed.; Spon Press: Oxfordshire, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- De Gids, W.; Phaff, H. Ventilation rates and energy consumption due to open windows—A brief overview of research in the Netherlands. Air Infiltration Rev. 1982, 4, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- van Hinsberg, N.P. Aerodynamics of smooth and rough square-section prisms at incidence in very high Reynolds-number cross-fows. Exp. Fluids 2021, 62, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdusemed, M.A.; Ahuja, A.K. Effect of Wind Incidence Angle on Wind Pressure Distribution on Square Shape Tall Building. Int. J. Res. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2016, 6, 4. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 15927-4:2005; Hygrothermal Performance of Buildings—Calculation and Presentation of Climatic Data—Part 4: Hourly Data for Assessing the Annual Energy Use for Heating and Cooling. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- Polish Ministry of Investments and Development. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/archiwum-inwestycje-rozwoj/dane-do-obliczen-energetycznych-budynkow (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Polish Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Polish Climate 2024. Available online: https://imgw.pl/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/RAPORT-IMGW-PIB-Klimat-Polski-2024.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

| Literature Items | Mentioned Issue | Presented Research |

|---|---|---|

| [7,8,9] | The angle of wind inflow on a façade with windows is critical to the amount of air entering the building. | This statement was confirmed, and extensive numerical studies on this issue were carried out. |

| [21,22,23] | Study on the value of the wind pressure coefficients (Cp) for a façade with windows because this value strongly affects the accuracy of predicted airflow rates for natural ventilation | In the research presented, the distribution of the Cp coefficient for the analyzed facades was determined. |

| [28,29,30] | The use of natural ventilation allows for potential energy savings. | This topic was addressed in the research. |

| [38,40] | Orientation of the building with respect to the incoming wind (wind angle) is a key factor for the effectiveness of natural ventilation. | The presented conclusions are consistent. |

| Variable | Range | Accuracy | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | −29–70 °C | ±0.5 °C | 0.1 °C |

| Flow velocity | 0.1–40.0 m/s | ±3% | 0.1 m/s |

| Wind direction | 0–360° | 5° | 1° |

| Pressure | 100–1600 hPa | ±1.5 hPa | 0.1 hPa |

| Relative humidity | 10–90% RH | ±2% RH | 0.1% RH |

| Mesh | No of Cells | No of Faces | No of Nodes | Growth Rate | Orthogonal Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 665,118 | 4,311,785 | 3,377,272 | 1.1 | 0.21 |

| Dense | 952,937 | 6,334,374 | 5,060,408 | 1.1 | 0.22 |

| Case | Mesh | Mass Flow Rate [kg/s] | Volumetric Flow Rate [m3/s] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 m/s 0° | Normal | 0.473 | 0.386 |

| Dense | 0.476 | 0.389 | |

| 5 m/s 60° | Normal | 0.192 | 0.157 |

| Dense | 0.201 | 0.163 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Król, M.; Król, A.; Koper, P.; Węgrzyński, W. Annual Flow Balance of a Naturally Ventilated Room with a Façade Opening Covered by Openwork Grating. Energies 2025, 18, 6569. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246569

Król M, Król A, Koper P, Węgrzyński W. Annual Flow Balance of a Naturally Ventilated Room with a Façade Opening Covered by Openwork Grating. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6569. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246569

Chicago/Turabian StyleKról, Małgorzata, Aleksander Król, Piotr Koper, and Wojciech Węgrzyński. 2025. "Annual Flow Balance of a Naturally Ventilated Room with a Façade Opening Covered by Openwork Grating" Energies 18, no. 24: 6569. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246569

APA StyleKról, M., Król, A., Koper, P., & Węgrzyński, W. (2025). Annual Flow Balance of a Naturally Ventilated Room with a Façade Opening Covered by Openwork Grating. Energies, 18(24), 6569. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246569