Abstract

Local United Arab Emirates (UAE) inhabitants have shown heightened awareness and interest in renewable energy (RE), resulting in a rise in the installation of solar photovoltaic (PV) systems in their residences; however, electric utility earnings have decreased due to this tendency. Energy decision-makers are concerned about discriminatory resident access to incentives and publicly funded solar PV frameworks. To reduce solar PV installations, utilities and energy players have adjusted RE initiatives. Utility companies provide solar PV-assisted installations. Nonetheless, adopting such frameworks requires a comprehensive feasibility study of all elements to achieve a win–win condition for all stakeholders, namely energy consumers, grid operators, solar PV company owners, regulators, and financiers. This article predicts the success of numerous local UAE solar PV models using agent-based modeling (ABM) to assess stakeholders’ measurements and objectives. Agents represent prosumers who choose solar PV. The effects of their installation choices on stakeholder performance measures are studied over time. ABM results show that suitable solar community pricing policies can benefit all stakeholders. Therefore, enhanced RE implementation rates can grow equitably. Also, electric utility companies can recoup profit losses from solar PV installations, and solar PV firms can thrive. The proposed modeling technique provides a viable policy design that supports all parties, preventing injustice to any stakeholder.

1. Introduction and Motivation

Because local UAE citizens have become aware of the negative impacts of fossil fuels, a dominance, development, and shift towards RE systems has risen in the UAE market over the last decade [1]. According to studies, crude oil resources are limited and will not suffice for the total energy demand of future generations [2]. Solar PV distributed-generation systems have witnessed unprecedented growth and popularity due to their lower initial capital cost and enhanced reliability compared to other RE frameworks [3,4]. These shifts lead, in turn, to customer-driven models instead of a centralized electricity production system [5]. Solar PV distributed-generation projects, recognized for their rooftop PV systems, enable local UAE individuals to produce their own electricity. This contributes to reduced monthly electric bills, control and ownership of their energy infrastructure, and alleviation of harmful ecological impacts [6].

Nonetheless, because diverse customers in the UAE have followed the trend of solar PV installations for their facilities, the profit of many electric utility companies has diminished [7,8]. However, only homeowners can benefit from rooftop solar PV systems since renters cannot install these systems [9]. Additionally, the UAE is an oil-rich country. It exports crude oil to many countries [10]. Shifting to solar PV energy and RE will result in some impacts on the revenue of the crude oil trade [11].

These problems have raised concerns among RE actors, solar PV business owners, and UAE decision-makers. Only high-income homes can benefit from solar PV system installations. Furthermore, utility grid companies will have less revenue due to RE incentives, publicly funded solar PV systems, and customer-supporting programs.

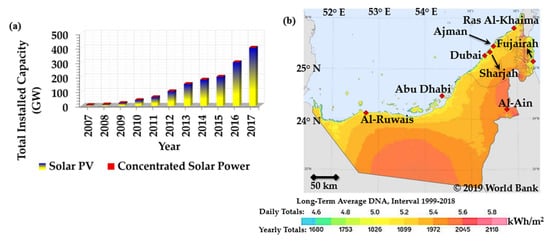

To tackle these problems, the UAE government has adopted a strategic energy mix plan for future decades. It implemented the Clean Energy Strategy (CES) 2050 to offer 44% of the country’s energy needs from RE by 2050, where 6% comes from nuclear, 12% comes from clean coal, and 38% comes from natural gas. In 2021, 127 TWh out of 135 TWh of total energy was provided by natural gas. Simultaneously, 5% (or 6.7 TWh) has been covered by recent utility-scale solar PV projects [12]. The country has witnessed a significant surge in implementing solar PV projects, as shown in Figure 1a. These schemes are driven by the UAE’s vision and commitment to raise the solar PV share. In addition, these promising solar PV transformations are driven by the significant availability of solar radiation in the UAE, as displayed in Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

(a) The growth of solar PV installations and concentrated solar power in the UAE, and (b) global horizontal irradiation map of the UAE [8].

Nonetheless, allowing many consumers to install solar PV systems will harm the revenue of electric utility companies. In this context, a comprehensive framework is needed to address the equity issue among all RE and UAE electric power stakeholders, ensuring that all parties benefit and no one loses or faces future injustice.

ABM can be utilized to predict customers’ behavior regarding the adoption of RE, specifically solar PV systems, when competitive RE frameworks are implemented to accelerate their prevalence and breadth. Accordingly, the ABM process can distinguish major impacts of these energy policies, subsidies, and incentives on the behavior of solar PV adoption among residents, and identify positive or negative impacts on all stakeholders. ABM is an influential optimization-simulation numerical approach. It can analyze RE systems by referring to socio-economic behavior, psychological aspects of the tendency to adopt RE projects, and technical-related metrics. This helps examine and estimate the efficiency, viability, and performance of RE strategies and policies proposed by governments under certain spatial boundary conditions and temporal frameworks. This analysis considers that many social interactions and dynamic human behavioral factors influence the behavior of the RE system. ABM is a novel strategy that can be harnessed to uncover critical insights into RE systems, which can provide equity to all energy stakeholders, including customers, grid operators, financiers, and energy policymakers, while ensuring satisfactory revenue for electric utility companies and solar business owners. ABM can clarify the conflicting advantage between stakeholders [13]. Therefore, comprehensive tactics can be identified and recognized to help overcome RE concerns related to RE equity, thereby reducing harm to parties’ equity in the UAE.

This paper’s sequence is structured as follows: Section 2 supplies a review of the relevant body of knowledge; Section 3 illustrates the ABM approach; Section 4 illustrates experiments conducted relying on the ABM strategy; Section 5 provides a summary of the experimental results and discussion of the findings with practical implications; Section 6 includes the paper’s conclusions; and Section 7 indicates future work directions.

2. Background and the Literature Review

Local UAE citizens utilize Net Metering (NetM) solar PV systems. This framework enables UAE individuals to gain money when there is excess production from a solar PV project [14]. Customers’ meters would move backward when the consumption is less than the solar energy production. The NetM solar PV programs, installed on the rooftops of local citizens’ homes, allow electricity utility companies to meet their needed RE portfolio standards. Through the RE portfolio, utility companies can supply a proportion of their electric energy from RE projects.

Compared to the UAE, over 70 countries are currently witnessing more significant corporate RE market growth [15]. NetM solar PV frameworks also raise the utility operational costs of the grid, the reason being that conventional electric networks’ infrastructure is neither designed nor well-prepared to install such dual-flow NetM solar PV programs [16]. Electric utility companies, as a whole, consider NetM programs a negative framework because of losses in total customer revenue [13].

In response to these issues, electric utility companies raise tariffs on customers, creating unfair fiscal burdens not only in the UAE but also in many other countries. This financial burden is more significant for low-income customers, who cannot install solar PV systems for their facilities. In addition, when utility companies change their energy strategies and policies, they may discourage installing solar PV systems. As a result, the growth, dominance, and prosperity of the solar PV business may decline. Also, the customer–utility relationship may be negatively influenced [17].

For this reason, similar problems noted in the UAE have occurred in other nations, resulting in adverse equity issues among different solar PV system stakeholders when these systems have been implemented. Publicly funded solar PV programs enable high-income people to access such systems. However, these financial subsidies and incentives cannot help low-income families, especially with low levels of innovation, awareness, and perception in RE [18].

To provide an interpretation of this phenomenon, it is crucial to predict, compare, and understand the various impacts in other countries when the same problem occurs. For example, in the USA, publicly funded solar PV programs have affected customer–utility relationships, a change that has similarly occurred in the UAE. Publicly funded frameworks have enabled only high-income citizens to benefit from such solar PV benchmarks; however, medium- and low-income people were not able to take advantage of these frameworks. These incentives can foster solar PV rooftop installations. They take into account tax exemptions, property, and tax credits at the federal and state levels [13].

In Malaysia, electric utility companies have formulated multiple net-metering compensation programs since 2011; however, due to insufficient financial returns, some NetM schemes, like the one implemented in 2016, have shown reluctance among prosumers compared to earlier electricity frameworks, including the Feed-in Tariff (FiT). Utility companies continued to formulate and plan new NetM schemes to ensure equity for all local citizens, including both high-income and low-income prosumers, such as NetM 2.0 and NetM 3.0. Nonetheless, such frameworks still require holistic investigations and thorough analysis to validate their feasibility and performance for all parties [19].

In Jordan, residential rooftop solar PV systems have been estimated by relying on different policies. The NetM and billing system contribute to the most practical savings, needing the shortest payback period (PBP). In addition, energy storage technologies (ESTs) provide 70% self-sufficiency and a zero-export situation. Nonetheless, ESTs necessitate higher capital investment costs. For the case of sell-all-buy-all, larger systems can utilize such a framework. The levelized cost of energy (LCOE) would reach 0.0696 USD/kWh, while the net present cost (NPC) would equal USD 619. Utilizing the FiT strategy would correspond to an LCOE of 0.055 USD/kWh. FiT optimizes energy policies [20].

In Singapore, different solar PV billing frameworks are implemented for the residential sector, such as NetM, FiT, and net billing (NetB). Nonetheless, current research often does not analyze the effect of these frameworks on prosumers’ energy behavior in the post-installation phase, such as the rebound impact on energy utilization. This problem could counteract the original design of energy policies. In this respect, it is essential to study pivotal variables that influence optimal and flexible residential solar PV system installations [21].

In Brazil, rooftop solar PV systems have expanded due to regulatory milestones in 2012, 2015, and 2022. These frameworks underscore the economic and financial benefits of NetM frameworks. Prosumers utilize solar PV systems under Distributed Generation with NetM and Grid Compensation (GDII). NetM and GDII have achieved superior fiscal performance compared to Full Injection Distributed Generation (FIDG) under certain consumption bands. Positive NPC outputs under GDII are realized from 230 to 310 kWh, considering an internal rate of return (IRR) of 270 to 310 kWh. Additionally, larger financial returns connected to utilities have exhibited lower operational costs, specifically where distribution system fees and lower-voltage maintenance charges are minimal [22].

Germany, Japan, and China have broadly succeeded in adopting solar PV frameworks, offering typical strategies and key advantages for other countries to adopt such RE benchmarks. They have benefited from a collection of subsidies, coupled with tax incentives, research and development (R&D) investment, academia, and FiT frameworks [23]. These schemes and metrics have reduced the overall cost of solar PV systems, enabling them to compete actively with fossil fuels. Besides these positive achievements, by 2023, China will have installed approximately 570 GW of solar PV projects; more than any other country [24].

In India, the government has planned for ambitious targets of solar PV projects. It aimed to have 280 GW of electric power from solar PV systems in the coming years, although regulations, customer–utility relationships, and negotiations between central and state governments have hampered India’s promising plans. Failure to achieve suitable agreements between parties and stakeholders resulted in a delay in the growth of solar PV. Specifically, the National Solar Mission program initiated and implemented by the Indian government was restricted by poor grid infrastructure, land acquisition problems, and inconsistent adoption of solar PV policies [25].

In response to RE framework challenges in all countries, it is essential to adopt proactive modeling strategies and intelligent investigative approaches that can efficiently provide meaningful insights on the viability, effectiveness, and equity of implemented RE regulations and an effective interpretation of people’s behavior, including all parties and stakeholders to which these RE benchmarks are applied. One of these active strategies is the ABM. ABM can be used to analyze complex models and sophisticated systems by conducting simulations to explore the interactions between agents, representing individuals and stakeholders. For RE, the importance of the ABM approach is reflected in its feasibility in offering practical translation and supplying useful statistical facts for RE decision-makers and RE policy actors. This enables them to carefully understand emergent, complex phenomena and individuals’ behavior triggered by a new RE law, which are typically vague, unclear, and difficult to interpret at the individual level. Through ABM, which is considered a flexible, helpful tool, those experts can model and investigate heterogeneity issues and complex data related to certain RE regulations recently enacted and applied within specific spatial and temporal constraints, i.e., specific territory and time. Therefore, they can distinguish some influential, practical, lawful items and other poorly formulated laws that may cause a number of socio-economic issues, reflected in inequity, more profit and financial margin for some parties, and/or injustice related to other technical, social, and legislative affairs.

To provide information on the feasibility, practicality, advantageous impacts, and core contributions of ABM, it is imperative to explore the available body of knowledge. This critical revision includes some viable examples of efficient ABM implementation, through which beneficial interpretations are provided concerning complex phenomena, certainly the solar PV implementation issue.

For instance, References [26,27,28] utilize ABM to investigate critical factors that influence RE adoption. Their critical outcomes confirmed a collection of demographic and technical indicators that affect the adoption and diffusion of RE resources. ABM is utilized to predict customer–utility relationships and electric power consumption behavior, enabling optimal management and enhanced decision-making.

To strengthen and confirm the above information on the importance, viability, and critical advantages of ABM, especially for solar PV projects, Table 1 indicates some recent ABM approaches implemented to achieve equity among stakeholders when adopting solar PV projects by local citizens (prosumers), with a particular focus on the Arabian Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries.

Table 1.

Some recent studies that have focused on ABM to achieve equity among stakeholders when prosumers install solar PV systems.

As a whole, it can be inferred from these case studies that cooperation is necessary between prosumers, government, private sector, solar PV business owners, grid operators, financiers, and other stakeholders. Therefore, academic efforts, R&D, policies, and NetM, billing, and FiT frameworks can be optimally designed and planned to provide beneficial impacts in favor of all parties, helping reshape the energy landscape and drive solar PV energy into rigorous transformation, growth, and dominance. Therefore, solar PV technology can thrive and prosper, considering superior equity, positive adoption behaviors, stability, profits for all parties, and other important socio-economic factors.

3. Agent-Based Modeling

AGM is conducted and verified by the NetLogo 6.0.4 software package. It is explained referring to the ODD framework, i.e., Overview, Design concepts, and Details.

3.1. Objective

The main goal of AGM is to foresee prosumer implementation behavior and their psychological and socio-economic response to various RE models, RE policies, and governmental energy subsidies and frameworks. Therefore, this approach can help decision-makers in optimally designing better energy strategies that enable RE to prosper and grow without triggering equity problems among certain stakeholders. Also, AGM aims to identify the effects of implementing RE-growth-acceleration approaches. Thus, a better understanding and key insights into key RE drivers can be recognized, aiding energy actors in using the most suitable energy development tactics to enhance overall RE performance, considering various stakeholders’ metrics. These metrics include NPC, revenue from solar PV systems, the overall clean electric power exported to the grid, and the overall prosumer involvement in RE models at each simulated time step. Critical examples of stakeholders’ metrics are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Critical metrics of interest linked to stakeholders.

ABM outcomes are utilized to make informed decisions regarding solar PV system design and RE growth policies, aiding stakeholder goals and achieving a comprehensive and fair RE share and growth for all parties.

3.2. Scales, Variables, and Entities

The conceptual ABM includes 200 UAE families, who act as agents (prosumers) and have installed solar PV systems for their homes. This typical number was captured from [13]. Their systems are connected to a hypothetical electric utility company, assumed to be an Abu Dhabi electric utility company. Table 3 illustrates critical demographic variables related to those families. These demographic data have been considered from the study [13]. Individuals aged 30 years or older were considered because fathers, who are mostly the decision-makers in a typical UAE family, are generally this age or older. Table 3 displays the typical salaries considered for the UAE.

Table 3.

Demographic data of the community of interest.

Every agent (family) has a distinguished identification index (i) and a community identification index (Ci), which indicates the community where families live. Table 4 shows how many families every community includes. The number of families chosen refers to the population density in each state in the UAE.

Table 4.

Key characteristics of communities of interest.

These numbers have been chosen as evidence of concept to utilize the ABM and design an RE system considering the urban scale. As shown in Table 3, each head of the family (father) is characterized by five demographic indicators: educational level (ELi), job title (JTi), age (Ai), residential location (LLi), and income (Ii). The values of ELi, JTi, LLi, and Ii remain constant during every simulation run; however, Ai rises with the simulation time. In addition, every family is categorized as living in an apartment, being a homeowner, or renting. This factor will remain fixed throughout the simulation run. It is assumed that 70% of agents rent properties, while 30% are home or apartment owners, according to the Dubai Rental Report [39]. It is presumed that only home or apartment owners would install rooftop solar PV systems, while renters would benefit from community solar PV programs. Therefore, 70% of UAE society will utilize solar community PV frameworks, while 30% of UAE people will install private rooftop solar PV systems. Also, it is presumed that each agent (head of family) will consume QEi amount of monthly electric power. ABM does not consider energy efficiency metrics. For this reason, the monthly electric consumption of each agent will remain constant during the simulation.

3.3. Overview of the Model

For every time step (monthly basis), every customer can decide and choose either to rely holistically on the grid, i.e., buy electricity from the grid, or to utilize a solar PV system (which can be achieved by (1) installing private solar rooftop PV systems, or (2) utilizing solar community programs). This solar PV-adoption decision is influenced by demographic variables, financial capability, awareness of the feasibility and importance of solar PV energy, and the effects of other agents. The effects of other agents mean that some families will see other families who have installed solar PV systems and benefited from these systems in reducing their monthly electric bills. Therefore, socio-economic behaviors and psychological changes are considered driving forces that influence a family’s decision to adopt solar PV systems, helping raise and accelerate solar PV growth and dominance. Families will study data from solar business owners, other families that have adopted solar PV systems, and the electric utility company to provide decisions on the economic feasibility and viability of installing such systems.

3.4. Solar PV Diffusion and Transformation

Agents who install private solar PV systems or utilize solar community frameworks will help achieve more prevalence, growth, evolution, and emergence of solar PV systems. This is because local UAE citizens will hear many success stories, compelling information, and positive experiences with solar energy. Therefore, positive psychological changes and socio-economic decisions to adopt solar PV will rise, contributing to enhanced RE growth and increased awareness.

3.5. Solar PV Adaptation

The adaptation behavior of agents (UAE families) will change towards solar PV energy. The environment will also change with increased diffusion, emergence, and growth of solar PV systems. The environment will also adapt, enabling enhanced solar PV adoption. This means that local UAE individuals will see changes in RE tax credits, electric tariffs, subsidies, a decline in prices of solar PV systems, and the emergence of many TV, radio, and social media advertisements, news, and changes in legislation, RE laws, and incentives, actively helping encourage RE adoption. Many successful projects and viable facts will convince families. They will adapt to the growing wave of solar PV installations and the promising solar PV investment climate by installing many solar PV systems, similar to others, as additional information and resources in society are provided.

3.6. Agent’s Objectives

The main objective of every agent (head of family/father) is to save as much money as possible on each monthly electric bill. Also, agents want to be exporters of clean electricity instead of being normal consumers, i.e., becoming investors in the RE business. These objectives are influenced by agents’ awareness, demographic factors, and financial capabilities.

3.7. Interactions

Interactions to adopt solar PV at the end include two factors. The first one is the community itself. When agents see many solar PV systems installed on the rooftops of homes in society, their decision will change. Positive interactions will drive them to these large installations. The second interaction factor is information. Agents will either ask other people who have installed solar PV projects regarding the feasibility, effectiveness, and cost-viability of these RE systems, or the media will influence decision-making. Agents will be driven by their positive psychological behavior and response to news on TV, radio, and social media regarding RE success stories. They will look for information and facts until they are convinced, and, therefore, they tend to install solar PV for their homes. Some fathers (heads of families) will also consult solar PV experts to provide clear answers on the practicality of solar PV systems. Every agent is presumed to be connected to two neighbors (N = 2), who will discuss with them the possible benefits of solar PV systems. Two customer agents, j and l, are assigned relying on a similarity index, such that [13]:

where Ai, Ii, Ei, and Ri are the agent’s age, income, educational level, and race; C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, and C6 are constants; C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, and C6 equal 0.0417, 6, 0.0167, 15, 0.05, and 5, respectively, according to [13]. Each demographic factor can possibly have an ultimate similarity of 0.25. This occurs when the two demographic factors for the two agents are the same. The minimum value of similarity is 0; this occurs when the two agents have different (opposite) demographic values.

3.8. Initialization

When numerical simulations start, it is presumed that every agent (head of the family, father) has not yet installed a solar PV system. The family pays for the grid to obtain electric power. The electric tariff is identified based on Dubai’s residential tariffs. It is presumed that the tariffs of all residents in the eight communities are within the green layer, i.e., the price of electricity in the UAE reaches 0.230 AED/kWh (or 0.0063 USD/kWh) [40]. The UAE government does not provide an income tax credit (ITC) for solar PV systems, but it offers incentives, such as a zero-rated Value Added Tax (VAT) and tax and duty-free advantages over the first ten years of solar PV installation [41].

3.9. Subsidiary Models

The ABM approach consists of three subsidiary models. These models are considered in the simulation process with a monthly time step corresponding to each agent.

3.9.1. The First Sub-Model: Estimation of the Agent’s Attitude

The agent’s attitude is reflected in his awareness level (ranging from 0 to 1) regarding the ecological importance of RE projects. Since individuals with a higher educational level have a significant chance to implement RE, the initial amount of the term, AWLi, is defined as the normalized product of agent i and educational level ELi, with K. K represents a random number (from 0 to 1). Because agents who have greater educational levels will have a higher tendency to buy solar PV systems for their dwellings, the educational level of AWLi can be estimated relying on the following formula [13]:

To illustrate, higher AWLi values indicate a greater likelihood of the agent purchasing a solar PV system or utilizing a community solar PV framework. When one homeowner buys a solar PV system, the AWi amount will rise by 1%. The reason for this is the visual interaction of agents, as they are influenced by beneficial solar PV impacts realized by other neighbors. The AWi would also increase in families who have not yet adopted solar PV systems due to social interaction through successful RE stories. The awareness scale of solar PV adopters after buying solar PV systems, AWLj,(After), can be identified referring to the following relationship [13]:

where AWLj,(After) and AWLj,(Before) are the scales of awareness of agent j before and after visual and news interactions. Agent j has not bought a solar PV system yet. AWLb is the awareness level of the RE adopter, agent b. Larger values of AWi indicate a greater likelihood that agents will interact by attending RE seminars, watching RE news, or surfing social media apps to see successful RE stories. In simulations, it is assumed that agents can attend only one seminar.

According to [13], agents view purchasing solar PV as a complex issue due to the extensive information and facts that must be recognized and understood before making a decision, including the solar PV literature and official procedures, incentives, regulations, installation processes, and NetM policies. Nonetheless, community solar PV frameworks can reduce many of these responsibilities because the UAE government handles the complex procedures of solar PV installations. In this respect, the complexity of solar PV installation can be expressed as follows [13]:

where RPCi is a random perceived complexity term, which ranges from 0 to 1. Smaller RPCi values suggest a greater possibility that an agent would purchase a solar PV system. Also, lower RPCi values are noted when the agent interacts with an RE adopter. Additionally, when an agent attends an RE seminar, RPCi will decrease by 0.1. Furthermore, every agent is identified by their ownership capability of the solar PV system, OCi. Greater OCi values indicate a stronger preference for solar PV community framework adoption. The value of OCi remains fixed during numerical simulations.

Additionally, every head of family (father) has a distinguished age-based level term, ABLi, which ranges from 0 to 1; this can be estimated through the following formula [13]:

where F is a random number. Greater ABLi values indicate a higher tendency to adopt solar PV systems since agents (fathers) have increased experience, awareness, and knowledge in PV with more age.

3.9.2. The Second Sub-Model: Evaluation of the Agent’s Fiscal Potential

AGM considers the optimism of agents (fathers) regarding the solar PV’s potential to achieve good profit for them. They are classified into five categories based on their optimism, Oi, regarding the viability of such RE systems, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Main agents’ categories referring to optimism of RE viability.

Data from Table 5 are captured from [13]. They indicate that high levels of optimism among local UAE citizens, primarily prosumers, would lead to positive changes in their psychological state, response, and behavior regarding the installation of solar PV systems as they anticipate rising electric tariffs in the future. At the same time, their optimism levels are high as the maintenance cost of solar PV systems is expected to decline in the coming years.

The Financial Capability Index (FCi) is used to express an agent’s (father’s) fiscal potential to purchase a solar PV system, which ranges between 0 and 1. Greater values near 1 indicate that the family has sufficient money to purchase and install a solar PV system. FCi can be estimated by referring to the following formula [13]:

where H is a random number. Agents will calculate the NPC of the solar PV system to predict if they are capable of purchasing a solar PV system. They also refer to a logical decision-making process to determine if they can install a solar PV system, as illustrated in Table 6.

Table 6.

Types of agents’ decisions to adopt a solar PV system.

From Table 6, homeowners with sufficient financial means rely on cash to purchase and install solar PV systems. They neglect other solar PV installation approaches, like taking loans, leasing, or benefiting from solar PV community frameworks. Homeowners with moderate fiscal capability choose loans or leasing to utilize solar PV systems. Renters, even with sufficient funds, may not install solar PV directly due to the extensive paperwork and complexities involved. They will encounter some difficulties in installing and utilizing solar PV systems. Ownership makes solar PV adoption more flexible. Solar PV frameworks can facilitate solar PV adoption for them.

To determine the present cost of the solar PV system, PAPV,install, the following equation is used [13]:

where WPV is the wattage (size) of the solar PV system to cover the total energy needs (in kW DC); ICPV is the installation cost of the system (USD/kW DC); TCIn is the income tax credit. In addition, the electric bill savings obtained per month, EBSPV,month, can be estimated as follows [13]:

where ECMonth is the electricity consumption per month; ETMonth is the monthly electric tariff, which increases per annum—referring to the agent’s EEC, i.e., expectation that the electric tariff will increase in the future; d is the annual discount rate, e.g., 5%, which is assumed as 5%. The lifespan of the solar PV system is 25 years. Simultaneously, to identify the present cost of solar PV maintenance, PMCPV, the following equation can be utilized [13]:

These formulas help evaluate the NPC of the solar PV system, NPCPV, such that [13]:

If an agent takes a loan to install a solar PV system, then the monthly payments should be identified. In this context, monthly payments, MPPVL, can be determined by the following formula [13]:

where PC is the principal cash; r is the interest rate (it is assumed to be 0.5%); N is the overall number of months. It is also crucial to distinguish the present value of the monthly payments, PAMP, which can be estimated by the equation outlined below [13]:

where T is the number of years related to the loan (e.g., 10 years). This gives an N of 120. Local UAE citizens also seek to determine the net present cost of the loan, NPCPV,Loan. This index can be calculated as follows [13]:

When a family decides to adopt a solar PV system by leasing, the leasing cost per month is identified by the solar PV system owner. It relies on the solar PV system wattage, the installation cost, the income tax credit, the solar PV owner’s expected rate of return (ROR)—presumed to be 5%—and the leasing interval, which is 25 years (the PV system’s lifespan). The total PV installation cost is similar to the cash paid in Equation (7). Nonetheless, solar PV owners retain benefits linked to the income tax credit instead of customers.

The net present value of the solar PV system leasing process can be identified through the following formula [13]:

where Y is 25 years (solar PV lifespan). Another important index is the present maintenance cost related to the solar PV system, PMCPV,Lease; this term can be calculated when the family leases it and is estimated by the following equation [13]:

where AMC is the rate of the maintenance cost per annum (presumed to be 3%); ICPV is the initial cost of the solar PV system. Also, the monthly leasing cost MLCi can be computed by the formula below [13]:

When the family rents an apartment and wishes to benefit from solar PV community frameworks, then the principal linked to the overall monthly energy bills should be estimated. This term can be identified as follows [13]:

where FPPV is the solar PV fixed premium; ETMonth is the monthly electric tariff, meaning the unit price of the electricity the agent pays equals (FPPV + ETMonth), which remains fixed throughout the entire community solar PV framework life; ECMonth is the electricity consumption per month. On the other hand, when local UAE prosumers want to utilize community solar PV systems, they may need to compute their NPC. In this respect, the NPC of the community solar PV framework can be evaluated by the following [13]:

3.9.3. Time-Step Decision Procedure

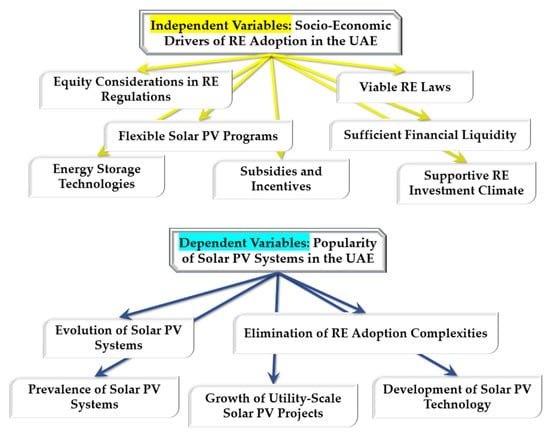

Before introducing the decision process conducted by agents, it is important to distinguish the main independent and dependent variables that need interpretation by the ABM method. Firstly, dependent indices are those whose values are controlled and monitored by independent variables. Independent variables do not change if other variables vary, but changing these independent indices would affect other variables that rely on them. Figure 2 displays the correlation between independent and dependent variables.

Figure 2.

ABM to uncover effects of independent variables on dependent indices.

To illustrate, the popularity of RE in the UAE (i.e., RE adoption, prevalence, growth, evolution, and the elimination of complex RE frameworks and implementation procedures) relies on certain independent variables that control it. Monitoring these indices positively can facilitate and accelerate RE adoption. Independent variables include sufficient financial liquidity, viable RE laws, equity considerations in RE regulations, flexible RE programs, the existence of efficient ESTs, the provision of subsidies and incentives, and the supply of a welcoming and supportive RE investment climate.

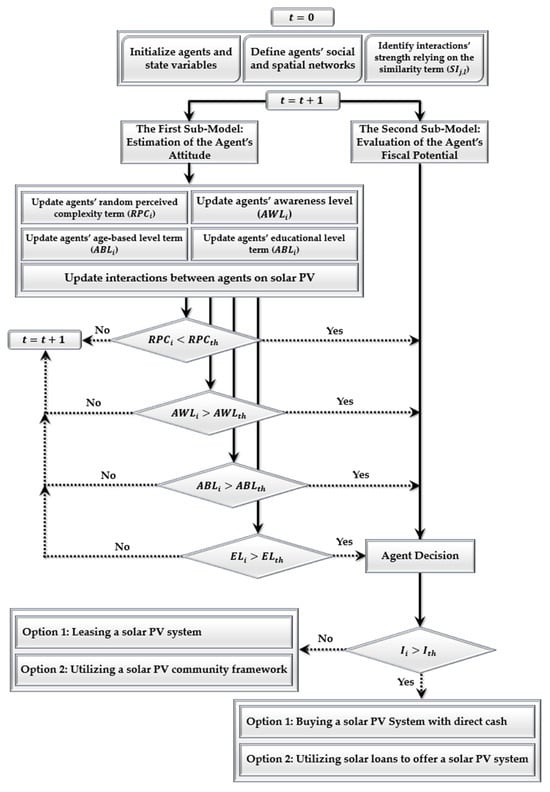

Next, the decision-making process conducted at each time step by agents, including owners and renters, is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Time-step decision procedure flowchart of agents to adopt solar PV energy (Author, 2025).

To elucidate, it can be inferred from this figure that the random perceived complexity (RPCi) should be less than the threshold RPCth so that agents can find installing a solar PV system a simple and viable process. Also, the awareness level should exceed the threshold awareness scale, which is initialized at 0.7. This means that an awareness level greater than 0.7 corresponds to sufficient scales of knowledge, consciousness, perceptions, and attitude among agents regarding critical solar PV benefits. Therefore, they can understand the risks and opportunities of their solar PV-adoption decision. Additionally, the age-based level term should be greater than the threshold age. The threshold age is 30 years, as expressed previously in Table 3. Agents with this age and above would have greater experience, skills, knowledge, realization, and perceptions in RE. Therefore, their solar PV installation decisions can be viable, suitable, and efficient. In addition, the educational level should be higher than the threshold. The threshold educational level here is a bachelor’s degree. However, people with master’s and doctoral degrees would have more knowledge, feasible facts, and recognition, helping to interpret and understand different dimensions of their solar PV-adoption decisions. Agents with a bachelor’s degree and greater experience would also have more information and knowledge to analyze the effectiveness and profitability of their solar PV installation decision.

The income of each agent also influences the agent’s decision. When the income is larger than the threshold income (which is AED 15,000 or USD 4084), agents might consider buying a solar PV system or taking a bank loan to provide one. When their income is less than the threshold income, they would think of leasing a solar PV system or utilizing solar PV community frameworks. The interaction probability among two families (agents) is presumed to be 0.6. When the awareness, age, or education is less than the threshold values, then t = t + 1, i.e., more time is considered to enable more interactions and allow for sufficient values of awareness, age, and education until a solar PV-adoption decision is made.

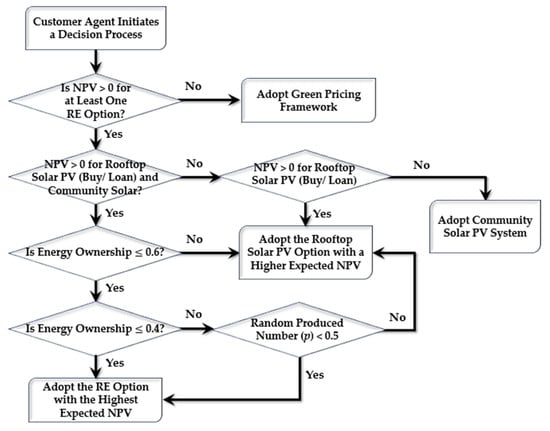

To simplify the process of making the solar PV-adoption decision, another simpler diagram similar to Figure 3 is introduced. It is captured from [42].

From Figure 4, it can be observed that if there is sufficient financial liquidity among agents, they would consider directly buying a solar PV system for their home because their financial capabilities are suitable to cover the NPC of the solar PV system. Comparatively, if they have less financing potential, they would consider adopting other solutions, such as a green pricing framework. If they have less fiscal liquidity, they would think of taking a bank loan. At the same time, if their financial liquidity is very low, they would consider adopting community solar PV systems, with the risks and responsibilities covered by the government. It should be noted that random numbers are utilized. These numbers are crucial to consider fairness and unpredictability, which are taken into account when conducting numerical simulations by the ABM processes.

Figure 4.

Simpler time-step decision process flowchart to install solar PV systems by agents [42].

3.10. Research Validation

To verify the results presented in the following sections, it is imperative to conduct a comparative analysis between the current research findings and the outcomes of other studies, particularly those that have investigated the trends of RE installations in the UAE. In this context, it is noteworthy that the UAE government has shown a serious attitude to and great interest in adopting various large-scale RE initiatives, which align with the positive perceptions and increased interest among local UAE citizens to buy and install solar PV projects.

Specifically, studies have reported that the UAE government has inaugurated some utility-scale solar PV projects, namely Al-Maktoum Solar Park (currently 3.9 GW and 5 GW by 2030). Referring to these RE implementation efforts, the total installed capacity of the UAE RE reached 596 MW in 2018, including 2 MW of wind, 594 MW of solar, and 100 MW of concentrated solar power [2]. In addition, the UAE government has considered some community initiatives, notably the Masdar project [43]. Established in 2006, Masdar has cooperated with many local and global corporations. It has advanced the prosperity and commercialization of various RE projects through green loans, like electric vehicles (EVs), solar PV installations, wind farms, and waste-to-energy systems. The UAE government enabled Masdar to support local UAE citizens and foreign investors, helping to add more sustainability and diversity to the current UAE economy.

Studies have also clarified that, in December 2022, Masdar established multiple shareholding partnerships with local and global companies to help increase its responsibility in supporting local and foreign RE customers. Besides these strategies, Masdar has created a resilient and balanced portfolio to supply long-term values and satisfactory operational outcomes whilst prioritizing favorable ecological and social impacts and controlling financial risks. With favorable and promising RE outputs, the UAE government has strengthened Masdar’s role in monitoring RE investments and overseeing the development, construction, transmission, distribution, and operation and maintenance (O&M) of electric utility networks [44].

For further validation, it is important to note that the UAE government, like the local UAE citizens’ RE adoption behavior, has shown increased interest in establishing further RE projects. These projects involve Al-Dhafra, Barakah Nuclear Power Plant, Shams, Noor Abu Dhabi, and Al-Ajban Solar Park. An explanation of the critical features of these RE projects is provided in Table 7.

Table 7.

Famous large-scale RE projects in the UAE [45,46,47].

In addition, the UAE government has administered some viable RE initiatives, particularly Shams Dubai. Through this initiative, local UAE customers can install solar PV projects on their homes; therefore, they can produce their own electric power to cover the electricity requirements of their dwellings. In turn, people can save on their monthly electric bills. Also, they can export surplus electric power to the electric grid of the Dubai Electricity and Water Authority (DEWA), which was launched in 2015. The citizens can, thus, receive credits for this RE retail through the NetM framework. Shams Dubai is a pivotal part of the 2050 Dubai Energy Strategy, whose major objective is to raise the overall clean energy supplied from RE resources to 75% [48].

In response to these positive environments of RE investment, many RE companies have been established in the UAE, such as Yellow Door Energy, ALEC Energy, Enviromena Power Systems, City Solar, Emirates Renewable Energy, Tek Solar, Al-Shirawi Solar, Green Bee, Ignite Power, and Enerqi. Link and SirajPower have differing numbers of employees, various global and local rankings, and varied scales of service.

Furthermore, some RE corporations, whose service areas extend to countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), have been established, such as ACWA Power and ENGIE. These companies are considered key players in the GCC zone. They are focused on constructing various large-scale RE projects and making proactive investments in low-carbon thermal energy projects to generate useful power [49].

4. ABM Experiments

ABM is utilized to explore the impact of agents’ (families’) decisions on influential performance indices related to solar PV business owners, policymakers, and electric utility companies within various RE models available for agents to select from. The outcomes have been analyzed relying on a time step of twenty-five years (300 months), considering fifty iterations. A time step of twenty-five years is chosen for simulations. After twenty-five years, it is possible that agents would implement a new RE system.

4.1. Experimental Levels and Indices

Seven experiments are conducted, resulting in variant model indices, as illustrated in Table 8. In experiment {1}, agents will utilize direct cash only as the best solution to install a solar PV system for their homes. In experiment {2}, the results explain less financial affordability. Therefore, the agents (families) may utilize loans to purchase a solar PV system. In experiments {3} and {4}, agents have less financial liquidity. They would tend to lease a solar PV system. In experiments {5}, {6}, and {7}, agents do not have sufficient fiscal liquidity. They would rely on solar PV community frameworks to provide a system for their homes.

Table 8.

RE models in seven experiments.

From Table 8, there are various RE models available for agents (families) to choose from. However, if the financial liquidity is high, they would prefer to buy a solar PV system directly. Nonetheless, because of the complexities of paperwork, community solar PV frameworks would be preferred. Agents in experiment {1} have many favorable options to either buy a solar PV system directly, take a loan to purchase a solar PV system, lease a solar PV system, or rely on a solar PV community framework with a competitive fixed premium rate, FPPV, of 0.0005 USD/kWh compared to other experiments (scenarios).

4.2. Outcomes of RE Models

The outcomes related to the RE models are expressed in Table 9.

Table 9.

Critical metrics of interest and their capture time linked to stakeholders.

These outcomes illustrate critical performance indices, which are connected with stakeholders’ objectives. The following sections explain the data in Table 9, corresponding to each stakeholder.

4.2.1. Electric Utility Companies

As can be seen in Table 9, electric utility companies are interested in identifying the present value of electric power revenues. This index is particularly important because these companies need to identify the best RE models that can be used by agents (families) without causing financial losses in revenue. Therefore, electric utility companies can recover financial losses, enabling users to install solar PV systems efficiently and flexibly. The electric utility companies receive significant revenues from regular customers who do not adopt solar PV systems. It can also earn revenue from agents who utilize community solar PV frameworks and pay the solar PV fixed premium FPPV plus the monthly electric tariff (FPPV + ETMonth). Moreover, the utility relies on overall clean power exported to the local network and the incremental rise in clean electricity by solar PV community frameworks. These metrics are imperative since they predict the effectiveness and feasibility of RE models, helping match the standard RE portfolio (SREP).

4.2.2. Electric Network Distributors

As noted in Table 9, electricity distributors aim to understand the total electricity demand to transmit electric power effectively. They also consider the operation and maintenance of the grid to enable efficient transmission of electricity to customers. Therefore, they can obtain a margin of profit without harming other stakeholders.

4.2.3. Prosumers

Prosumers are agents (families) who consume electricity and produce clean electric power from solar PV systems. As illustrated in Table 9, prosumers need to know the initial capital cost of solar PV systems to determine if they can purchase these systems. They also need to recognize the present worth of the revenue of the solar PV system to determine if these RE technologies are cost-viable for their living.

4.2.4. Solar Business Owners

As shown in Table 9, solar business managers need to identify the current price of their solar PV systems to enable agents to buy them flexibly. They also need to know the solar PV investment ratio to identify the system’s profitability. Solar business owners also consider operation and maintenance costs, especially for community solar PV frameworks, since agents rely on these systems to supply clean electric power. Knowing these indices support solar business decision-makers in understanding the financial impacts of providing families with purchased solar PV systems, leased solar PV systems, and solar PV community frameworks. The calculated present value of revenue for solar PV business owners includes all families who buy and lease solar PV systems, as well as those who utilize solar PV community frameworks.

4.2.5. Policymakers

As indicated in Table 9, policymakers rely on statistical data that express how many solar PV installers exist, including those for community and rooftop installations. Decision-makers also consider the ratio of local citizens who have access to solar PV systems, as well as the ratio of renters to homeowners. These statistics inform policymakers about potential strategic, holistic RE solutions that can accelerate, facilitate, and promote the equitable adoption of solar PV among families in the UAE.

5. Results

5.1. ABM Outcomes

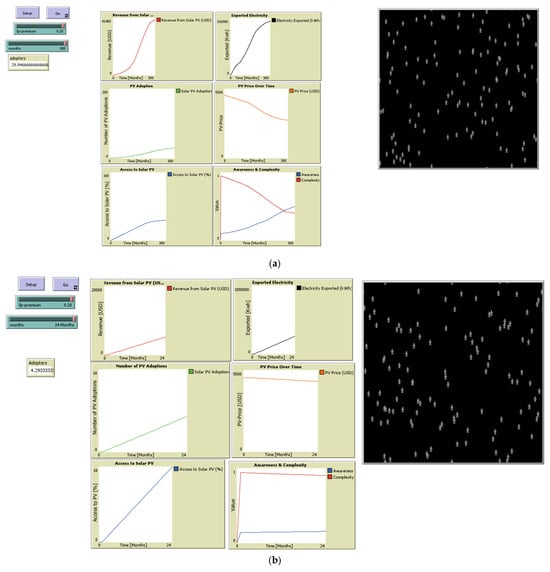

ABM is conducted by the NetLogo simulation software tool. Figure 5 shows the NetLogo agent-based model interface scenario outputs under different policies: (a) system state at 300 months, and (b) early-stage dynamics at 24 months. The left panel presents dynamic time-series outputs for six key metrics: revenue, exported electricity, adoption count, system price, access, and awareness/complexity. The right panel visualizes agent distribution, which represents household-level interactions with the energy system.

Figure 5.

NetLogo interface benchmark scenario outputs under current policy conditions: (a) System state at 300 months. (b) Early-stage dynamics at 24 months. The panels include time-series plots for revenue, exported electricity, PV adoption, system price, access, and awareness/complexity, alongside agent distribution across the simulated environment.

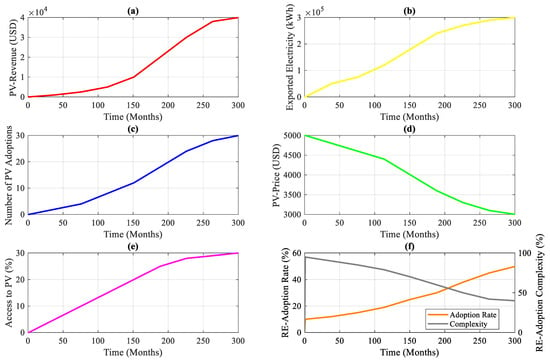

The results are displayed in Figure 6. It can be seen that the revenue over 300 months (25 years) increases until it reaches a final value of USD 176,000. The revenue is obtained from local citizens installing solar PV systems in their facilities, namely homes, commercial buildings, and factories. Figure 6 also shows that the clean electricity exported to the local grid would rise over the 300 months. It would reach a maximum value of 1,100,000 kWh. This means that there would be a surplus of clean electricity remaining after consumption.

Figure 6.

NetLogo simulation outcomes of (a) solar PV project revenues, (b) exported clean electricity, (c) number of solar PV adopters, (d) PV system price variation over time, (e) access to solar PV projects, and (f) RE awareness and complexity scales over 25 years (300 months).

Simultaneously, Figure 6c indicates that the number of solar PV adopters would reach more than 100 adopters after 25 years. The beneficial impacts would convince those people of solar PV energy. Additionally, Figure 6d explains that the price of solar PV systems would decline over the months. This observation is due to the significant interest in solar PV energy among UAE citizens. In terms of percentage, access to solar PV systems would increase to about 75% after 300 months. Furthermore, Figure 6f indicates that the awareness would rise until it reaches approximately 0.8 out of 1.0. In contrast, due to increased awareness, interest, and perceptions of solar PV systems, the complexity, misconceptions, and vague data will be eliminated after 25 years.

5.2. Current Baseline Benchmark Scenario

To ensure the validity and robustness of the results, a benchmark scenario was developed to serve as a means of comparative analysis. This scenario models the system’s behavior under the current policies, subsidies, and regulations, utilizing input parameters characterized by lower initial awareness, higher sustained PV system prices, and a higher perceived complexity scale (peaking at about 60% within two years). This scenario directly compares the time-series outcomes for all six key metrics (revenue, export, adopters, price, access, and awareness/complexity) over 24 months of solar PV installations.

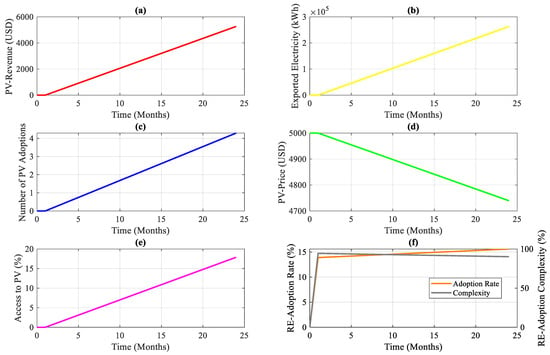

Figure 7a shows a steady increase in revenue from solar PV projects, indicating consistent financial returns and market growth. Figure 7b illustrates a linear rise in exported electricity, reaching approximately (6 × 105) kWh, which reflects expanding generation capacity. Figure 7c captures the growing number of PV adoptions, suggesting increased public engagement and technology diffusion. Figure 7d displays an upward trend in PV price, potentially due to premium system upgrades or market fluctuations. Figure 7e demonstrates a progressive increase in access to solar PV, underscoring successful infrastructure deployment and outreach. Finally, Figure 7f compares the scales of RE awareness and complexity, implying that, gradually, the levels of awareness in RE and solar energy are recording progressive enhancement and rise. In contrast, the complexity in these technologies is slowly declining, strengthening the importance of facilitating RE implementation laws, supportive solar PV frameworks, and helpful solar PV programs and guidelines until the evolution of RE and prevalence of solar PV technology in the main will increase and stabilize, removing any technical burdens.

Figure 7.

A baseline NetLogo ABM benchmark results of the current (a) solar PV project revenues, (b) exported clean electricity, (c) number of solar PV adopters, (d) PV system price variation over time, (e) access to solar PV projects, and (f) RE awareness and complexity scales over 2 years (25 months).

The benchmark scenario also clarifies that only about 30 adopters have installed solar PV projects within two years, which confirms that valuable and active RE policies are needed to increase the adoption rate, shown previously in Figure 6.

Collectively, each of the values of solar PV revenue, number of solar PV adopters, access to solar PV technology, exported clean electricity from solar PV systems, and solar PV price relies heavily on leveraged scales of awareness and very low rates of complexity. Significant RE awareness and very low complexity in RE would provide positive impacts on solar PV evolution. In turn, vague information, misconceptions, and any challenges would be eliminated when local UAE citizens want to install solar PV systems for their facilities, contributing to the enhanced expansion of solar PV technology in the UAE.

As a whole, the results underscore the importance of fair solar PV laws and efficient RE programs to achieve a mature and thriving landscape of solar PV technology, marked by remarkable economic viability, expanding access, and streamlined implementation.

The results of this study are consistent with those of Mittal et al. (2019) [13], who utilized ABM and found that solar PV energy attention, perceptions, and awareness would increase over time among US citizens due to the multiple implementations and installations of solar PV systems. Reference [13] also reported that due to increased awareness, the complexity and misconceptions related to solar PV energy laws and regulations would decline over time. Therefore, local US people would understand the risks, benefits, practicalities, and feasibility of solar PV energy. The same reference explained that the total green power exported to the grid would increase when local US citizens install and adopt more solar PV systems for their homes and facilities. Reference [26] also utilized ABM and found that solar PV installations would increase awareness and perceptions, thereby reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from fossil fuels. As a result, low-carbon policies are considered to expand and enhance the adoption of RE and solar PV systems. Additionally, the results of this work are compatible with References [27,28], who harnessed ABM to predict the impact of low-carbon strategies and energy storage approaches. These strategies aim to raise awareness, perceptions, and trust in RE and solar PV systems by increasing their resilience, reliability, and performance. In addition, References [27,28] clarified that ESTs could eliminate technical problems related to RE fluctuations due to solar radiation and wind speed variations throughout the day. Therefore, the number of local citizens who would install RE projects, like solar PV frameworks, would increase with time.

Overall, the adoption of solar PV systems among local UAE citizens will witness increasing rates over time because the vague data, complexities, and misconceptions will be removed when more and more UAE people install such RE projects for their facilities. In addition, complexities in solar PV policies, laws, regulations, and frameworks will gradually diminish, contributing to greater equity due to the expansion and increase in solar PV adoption. This rise in solar PV installations will urge UAE decision-makers to formulate fair RE policies and balanced regulations to satisfy all stakeholders in the electric power sector. These results are consistent with Reference [13].

In this respect, it is noteworthy to distinguish the contribution of this study, i.e., how this study differs from others. These results are promising for practitioners and researchers in the electricity sector because the findings prove the importance of considering awareness, interest, attitude, and knowledge in solar PV systems, whose careful analysis and treatment would remove much of the vague information, helping decision-makers formulate balanced laws to satisfy all stakeholders and promote equity for all parties without creating injustice concerns.

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis

Typically, the ABM process relies heavily on assumptions, such as thresholds of income, awareness, age, educational level, race, and tariff rates, among others, although these indices are deterministic. In comparison, the real-world behavior of these variables is stochastic. For this reason, it is necessary to implement a sensitivity analysis to validate the robustness of the ABM outputs. This analysis will enable researchers to understand which index, variable, or factor in the assumptions has a greater influence on the final ABM findings when they vary. Hence, sensitivity analysis could enable them to identify the most prominent variable affecting the final decision of solar PV adoption among UAE families and agents.

Consequently, Table 10 and Table 11 are presented. They explain the changes in awareness level and solar PV-adoption complexity when agents’ salaries and the number of solar PV systems installed vary. A what-if analysis was applied in Excel, which generated the sensitivity analysis results for the following two tables.

Table 10.

Prediction of the number of total installed solar PV systems among agents, referring to salaries and the educational level—sensitivity analysis.

Table 11.

Prediction of the awareness level change among agents referring to salaries and the educational level—sensitivity analysis.

From Table 10, it can be concluded that higher salaries along with greater educational levels would raise the overall number of installed solar PV systems, i.e., they would have positive impacts on the behavior of agents to adopt solar PV projects. This is because, with a higher educational degree and larger salaries, better information and knowledge, and enhanced financial capability can be provided. In addition, Table 11 shows that with a greater educational level and higher salaries, access to solar PV information and beneficial facts can be flexible. Therefore, the overall awareness of solar PV feasibility and profitability would increase.

6. Conclusions

This research was conducted to investigate the behavior, psychological change, and tendency of local UAE people to install solar PV systems, influenced by RE laws, solar PV frameworks, and some socio-economic factors. ABM is utilized to predict the performance of a collection of solar PV models. This study considers RE regulations and laws with a specific focus on equity to satisfy all stakeholders without causing injustice to certain parties. A total interval of 25 years (300 months) (lifespan of the solar PV system) is taken into account for the modeling and simulation process. The results of this study reveal the following:

- Over time, the awareness, perceptions, attitudes, and interest among local UAE citizens in adopting solar PV systems would increase. Therefore, complexities, misconceptions, vague regulations, and unfair laws would decline.

- The total clean electric power exported to the local UAE network would increase due to greater awareness and increased installations of solar PV systems among UAE families.

- By 300 months, the ratio of local citizens who would have satisfactory access to solar PV systems would account for roughly 80%.

- Due to increased awareness, the price of solar PV systems will progressively decline each year, reaching an affordable level in the future.

- Due to various amendments and modifications of different solar PV frameworks and regulations, sufficient scales of equity would be provided for all stakeholders. Additionally, the revenue from solar PV systems would increase annually, enhancing satisfaction among UAE customers, electric distribution operators, and grid owners.

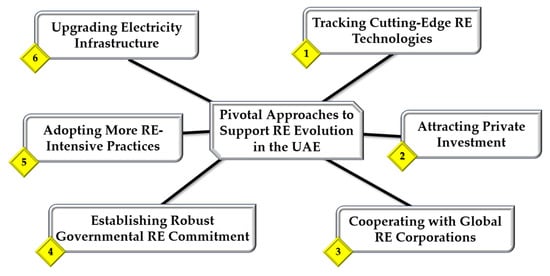

Referring to these research outcomes and critical insights, a conceptual framework is formulated—consisting of a number of concrete policies—to support decision-makers, solar PV companies, electric power providers, grid operators, and other stakeholders in supplying optimal rates of solar PV growth, RE expansion, and prosperity without adversely affecting the equity concerns of any party. Figure 8 illustrates these influential strategies.

Figure 8.

This study’s conceptual framework.

As can be seen from the first strategy, the UAE government can track breakthrough RE technologies. Global patents, innovations, and advancements in RE are witnessing a rapid increase. Therefore, the UAE government can follow up and implement novel RE solutions that are more efficient, viable, and equitable for all stakeholders.

Regarding the second solution, the UAE government can offer a risk-free investment climate by providing incentives and financing. This approach aims to encourage utilities and local UAE citizens to invest in and install various RE projects flexibly without encountering financial problems.

With respect to the third solution, the UAE government can collaborate with various large-scale RE organizations, which have abundant and long-term experience in RE, to eliminate risks and alleviate economic losses.

Concerning the fourth strategy, the UAE government can set a strong RE commitment. This step can be achieved through defining ambitious, clear RE targets and adopting supportive regulatory and policy environments.

Pertaining to the fifth approach, the UAE government can implement more RE-intensive practices by urging local UAE citizens and private businesses to implement RE technologies, which correspond to overall energy consumption alleviation.

Finally, through the sixth strategy, the UAE government can upgrade infrastructure by using cost-effective approaches, such as microgrids (MGs) and smart grids (SGs), and utility-scale energy storage techniques, including large molten salt tanks, phase change materials (PHMs), and novel versions of lithium-ion batteries.

7. Future Work Directions

Based on the main research outcomes, it is suggested to implement a few recommendations to enhance the effectiveness of the overall findings. These aspects are expressed in the following:

- ■

- To conduct semi-structured qualitative studies through interviews with highly experienced engineers, who hold some influential positions and higher managerial levels in MASDAR and Estidama.

- ■

- To conduct field visits and thorough inspections of the current electric network, grid distributors, and network operators, while exploring opportunities to integrate novel cost-effective solutions to enhance grid stability, efficiency, and performance, such as SGs, MGs, and new ESTs, which can address emerging challenges in electric network infrastructure.

- ■

- To reconduct the ABM process, considering real-time grid data and time-varying energy policies. Also, it is suggested to include other stakeholders to make AB&MS more comprehensive.

- ■

- To meet RE financiers and predict pivotal opportunities and key obstacles that may expand and hinder the broad solar PV investment and financing for private companies and local UAE citizens, respectively.

Author Contributions

K.Y.: Review, Writing, Survey, Questionnaire, Renewable Energy, Simulation, Modeling, Smart Energy Systems, Investigation, Data Analysis, Conceptualization. B.Y.: Conceptualization, Review, Writing. N.H.: Conceptualization, Review, Writing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

NetLogo simulation outcomes and ABM data can be provided upon request by the corresponding authors for replication and future work enhancements. In addition, the sensitivity analysis data in the Excel file can be provided upon request to reviewers or researchers interested in validating the robustness of the ABM outcomes and identifying the most prominent variables affecting solar PV-adoption decisions.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to acknowledge the academic peer reviewers for their research validation and estimation of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence this work.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABM | Agent-based modeling |

| BES | Battery energy storage |

| CES | Clean Energy Strategy |

| DEWA | Dubai Electricity and Water Authority |

| ESTs | Energy storage technologies |

| EU | European Union |

| EVs | Electric vehicles |

| FIDG | Full Injection Distributed Generation |

| FiT | Feed-in-tariff |

| GCC | Gulf Cooperation Council |

| GDII | Grid Compensation |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| GT | Game Theory |

| GW | Gigawatt |

| ICC | Initial capital cost |

| IRR | Internal rate of return |

| ITC | Income tax credit |

| kW | Kilowatt |

| LCOE | Levelized cost of energy |

| MGs | Microgrids |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NetB | Net billing |

| NetM | Net Metering |

| NPC | Net present cost |

| O&M | Operation and maintenance |

| ODD | Overview, Design concepts, and Details |

| PBP | Payback period |

| PHMs | Phase change materials |

| PV | Photovoltaics |

| R&D | Research and development |

| RE | Renewable energy |

| ROR | Rate of return |

| SGs | Smart grids |

| SREP | Standard RE portfolio |

| UAE | United Arab Emirates |

| VAT | Value Added Tax |

References

- Alnaqbi, S.A.; Alami, A.H. Sustainability and Renewable Energy in the UAE: A Case Study of Sharjah. Energies 2023, 16, 7034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, J.S.; Jafary, T.; Vasudevan, R.; Bahadur, J.K.; Ajmi, M.A.; Neyadi, A.A.; Soudagar, M.E.M.; Mujtaba, M.; Hussain, A.; Ahmed, W.; et al. Potential of Utilization of Renewable Energy Technologies in Gulf Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hammoumi, A.; Chtita, S.; Motahhir, S.; El Ghzizal, A. Solar PV Energy: From Material to Use, and the Most Commonly Used Techniques to Maximize the Power Output of PV Systems: A Focus on Solar Trackers and Floating Solar Panels. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 11992–12010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breyer, C.; Bogdanov, D.; Khalili, S.; Keiner, D. Solar Photovoltaics in 100 % Renewable Energy Systems. In Encyclopedia of Sustainability Science and Technology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndebele, T. Assessing the Potential for Consumer-Driven Renewable Energy Development in Deregulated Electricity Markets Dominated by Renewables. Energy Policy 2020, 136, 111057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izam, N.S.M.N.; Itam, Z.; Sing, W.L.; Syamsir, A. Sustainable Development Perspectives of Solar Energy Technologies with Focus on Solar Photovoltaic—A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarasamy, P.; Chopra, A.; Haddad, A. Exploring the Business Challenges in the Energy and Utility Sector of the United Arab Emirates. In Achieving Sustainable Business Through AI, Technology Education and Computer Science; Volume 2: Teaching Technology and Business Sustainability; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, T.; Mourad, A.H.I.; Hamed, F. A Review on Solar Energy Utilization and Projects: Development in and around the UAE. Energies 2022, 15, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhammami, H.; An, H. Techno-Economic Analysis and Policy Implications for Promoting Residential Rooftop Solar Photovoltaics in Abu Dhabi, UAE. Renew. Energy 2021, 167, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Boateng, O.; Al Jaberi, N.H.S. The Post-oil Strategy of the UAE: An Examination of Diversification Strategies and Challenges. Politics Policy 2022, 50, 380–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, M.S.; Al-Tamimi, K.A.M. Economic Impacts of Renewable Energy on the Economy of UAE. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2022, 12, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummieda, A.; Bouabid, A.; Moawad, K.; Mayyas, A. The UAE’s Energy System and GHG Emissions: Pathways to Achieving National Goals by 2050. Clean Energy 2023, 7, 962–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Krejci, C.C.; Dorneich, M.C. An Agent-Based Approach to Designing Residential Renewable Energy Systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 112, 1008–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamad, I.M. A Feasibility Study of Roof-Mounted Grid-Connected PV Solar System under Abu Dhabi Net Metering Scheme Using HOMER. In Proceedings of the 2018 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET), Dubai, Sharjah, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 6 February–5 April 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shaughnessy, E.; Heeter, J.; Shah, C.; Koebrich, S. Corporate Acceleration of the Renewable Energy Transition and Implications for Electric Grids. Renew. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 146, 111160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnusamy, V.K.; Kasinathan, P.; Madurai Elavarasan, R.; Ramanathan, V.; Anandan, R.K.; Subramaniam, U.; Hossain, E. A Comprehensive Review on Sustainable Aspects of Big Data Analytics for the Smart Grid. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansarin, M.; Ghiassi-Farrokhfal, Y.; Ketter, W.; Collins, J. A Review of Equity in Electricity Tariffs in the Renewable Energy Era. Renew. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 161, 112333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N.T.T.; Tran, K.T. Predicting the Intention to Install Solar Photovoltaic Panels in Emerging Market: The Role of Consumer Innovativeness, Knowledge, and Support for Government Incentives. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilham, N.I.; Dahlan, N.Y.; Hussin, M.Z.; Sintuya, H.; Setthapun, W. An Optimal Compensation Schemes Decision Framework for Solar PV Distributed Generation Trading: Assessing Economic and Energy Used for Prosumers in Malaysia. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrbai, M.; Al-Ghussain, L.; Al-Dahidi, S.; Ayadi, O.; Al-naser, S. Techno-Economic Assessment of Residential PV System Tariff Policies in Jordan. Util. Policy J. 2025, 93, 101894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Xu, J.; Tang, T.; Yuan, M.; Hwang, B.G. Agent-Based Modeling of Residential Photovoltaic Adoption and Diffusion: Implications for Energy Policy Design. Util. Policy J. 2025, 95, 101960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.M.F.; de Andrade Pinto, G.X.; dos Santos, D.O.; Antoniolli, A.F.G.; Naspolini, H.F.; Rüther, R. Uncovering the Beneficiaries: Exploring the Impact of New Distributed Solar Energy Legislation in Brazil. Renew. Energy 2025, 251, 123474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.; Rao, A.B.; Banerjee, R. Review of Solar PV Deployment Trends, Policy Instruments, and Growth Projections in China, the United States, and India. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 213, 115436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, T.S.; Kumar, P.U.; Ippili, V. Review of Global Sustainable Solar Energy Policies: Significance and Impact. Innov. Green Dev. 2025, 4, 100224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electricity Market Report 2023—Analysis, IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/electricity-market-report-2023 (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Zhao, C.; Zhou, M.; Li, J.; Fu, Z.; Liu, D.; Wu, Z. Evolutionary Pathways of Renewable Power System Considering Low-Carbon Policies: An Agent-Based Modelling Approach. Renew. Energy 2025, 244, 122686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussawar, O.; Mayyas, A.; Azar, E. Energy Storage Enabling Renewable Energy Communities: An Urban Context-Aware Approach and Case Study Using Agent-Based Modeling and Optimization. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 115, 105813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Tan, Q.; Ding, Y.; Liu, Y. Exploring the Diffusion of Low-Carbon Power Generation and Energy Storage Technologies under Electricity Market Reform in China: An Agent-Based Modeling Framework for Power Sector. Energy 2024, 308, 133060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiud, I.; Schukat, M.; Mason, K. An agent-based modeling approach for simulating solar PV adoption: A case study of Irish dairy farms. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 51, 100653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, S. An integrated agent-based simulation modeling framework for sustainable production of an Agrophotovoltaic system. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 420, 138307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhatova, A.; Kranzl, L.; Schipfer, F.; Heendeniya, C.B. Agent-based modelling of urban district energy system decarbonisation—A systematic literature review. Energies 2022, 15, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, M.; Salim, H.; Stewart, R.A.; Sahin, O. Residential solar photovoltaic adoption behaviour: End-to-end review of theories, methods and approaches. Renew. Energy 2021, 170, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, I.; Creutzig, F.; Filatova, T.; Foramitti, J.; Konc, T.; Niamir, L.; Safarzynska, K.; van den Bergh, J. Agent-based modeling to integrate elements from different disciplines for ambitious climate policy. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2023, 14, e811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandes, N.; Sanfilippo, A.; Al Fakhri, M. Modeling residential adoption of solar energy in the Arabian Gulf Region. Renew. Energy 2019, 131, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Fakhri, M.; Mohandes, N.; Sanfilippo, A. Modeling Solar PV Adoption in Qatar. In Proceedings of the 12th Artificial Economics Conference, Rome, Italy, 20–21 September 2016; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314193684_Modeling_Solar_PV_Adoption_in_Qatar ResearchGate (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Mohandes, N.; Bayhan, S.; Sanfilippo, A.; Abu-Rub, H. Decentralized PV Energy Trading: A Case Study of Residential Households in Qatar. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 153457–153470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsabbagh, M. Public perception toward residential solar panels in Bahrain. Energy Rep. 2019, 5, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, M.M.; Bansal, R.C. Solar energy development in the GCC region–A review on recent progress and opportunities. Int. J. Model. Simul. 2022, 43, 579–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Dubai Rental Report 2023. October 2023. Available online: https://www.cbre.ae/insights/figures/the-dubai-rental-report-2023#:~:text=Key%20Takeaways:%20In%20the%20year%20to%20July,registered%20in%20the%20same%20period%20in%202019 (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Government of Dubai. Slab Tariff. 2025. Available online: https://www.dewa.gov.ae/en/consumer/billing/slab-tariff (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- PVKnowHow. Unlocking Solar Manufacturing Success: A Comprehensive Guide to UAE Government Incentives. 2025. Available online: https://www.pvknowhow.com/countries/united-arab-emirates/solar-manufacturing-incentives-in-uae/#:~:text=Financial%20Incentives,from%20the%20Ministry%20of%20Finance (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Mittal, A.; Krejci, C.C.; Dorneich, M.C.; Fickes, D. An agent-based approach to modeling zero energy communities. Sol. Energy 2019, 191, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.F.; Tzes, A.; Yousaf, M.Z. Enhancing PV Power Forecasting with Deep Learning and Optimizing Solar PV Project Performance with Economic Viability: A Multi-Case Analysis of 10 MW Masdar Project in UAE. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 311, 118549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismael, N.I. Sustainability Criteria Used in Designing Energy-Efficient Smart Cities: A Study of Masdar City as a Model for One of the Smart Cities that Realize the Idea of Sustainable Development. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Bus. Sci. 2023, 4, 42–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UAE Government Gate Solar Energy Projects in the UAE. Available online: https://u.ae/en/information-and-services/environment-and-energy/water-and-energy/types-of-energy-sources/solar-energy (accessed on 21 September 2025).