Abstract

This study presents the development, purification, and performance evaluation of a biogas-powered electricity generation system designed for medium-scale swine farms. A conventional Hino V-22C diesel engine was modified to operate in spark-ignition mode using purified biogas with methane content ranging from 65 to 70%, obtained through a PSA upgrading system. The compression ratio was reduced from 18.5:1 to 14.7:1 to accommodate the lower heating value and combustion characteristics of biogas. An oxygen-sensor-based emergency fuel supply (EFS) system was integrated, activating when λ > 19.0 and deactivating when λ < 17.0, to enhance combustion stability under high-load operation. The corrected higher heating value (HHV ≈ 20–21 MJ/kg) and consistent fuel mass flow rate (0.036 kg/s) were used for revised thermodynamic calculations. Field testing over 524 operating hours demonstrated stable power generation between 80 and 120 kW. The EFS system increased thermal efficiency by approximately 22.7%, achieving a peak efficiency of 11.66% at 100 kW. A techno-economic assessment, including sensitivity analysis (±20% biogas yield and ±10% electricity price), confirmed economic viability with a breakeven period of 15.79 months. The system offers a reliable and scalable renewable energy solution for agricultural applications, contributing to methane mitigation and improved waste-to-energy utilization.

1. Introduction

The demand for sustainable and renewable energy solutions in the agricultural sector has steadily increased due to rising electricity costs, stricter environmental regulations, and the need to reduce methane emissions from livestock operations. Swine farms in particular generate large quantities of manure and wastewater, providing a substantial feedstock for biogas production. In Thailand and the ASEAN region, biogas systems have been increasingly adopted for decentralized energy generation; however, challenges remain in achieving stable engine operation, consistent gas quality, and economically viable power output [1,2,3,4,5].

While numerous studies have examined biogas-fueled engines, most have focused on either small-scale generators or laboratory-based experiments. The integration of upgraded biogas using Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA), combined with spark-ignition conversion of a large diesel engine and an oxygen-sensor-controlled emergency fuel supply (EFS) system, has not been sufficiently explored in practical medium-scale farm environments. This represents a critical research gap, particularly in Thailand, where mid-sized swine farms require reliable, on-site power systems capable of handling fluctuating biogas composition and variable electrical loads.

In this study, methane content from raw biogas was upgraded from approximately 55–60% to 65–70% using a PSA system, providing a more stable fuel source for engine operation. The Hino V-22C diesel engine was modified to operate in spark-ignition mode by reducing the compression ratio from 18.5:1 to 14.7:1 and integrating a precisely controlled ignition system. To address combustion instability under high-load conditions, an oxygen-sensor-based EFS system was implemented. This system automatically activates when λ > 19.0 and deactivates when λ < 17.0, ensuring stable lean-combustion behavior.

This work contributes three key innovations:

- (1)

- The integration of PSA-upgraded biogas with a modified large-scale diesel engine operating entirely in spark-ignition mode.

- (2)

- The development of an adaptive fuel stabilization mechanism using real-time oxygen sensor feedback.

- (3)

- A 524 h field validation demonstrating system reliability, scalability, and techno-economic feasibility under real farm operating conditions.

The novelty of this research lies in combining these three elements into a unified, farm-ready power generation system, supported by comprehensive performance evaluation and sensitivity-based economic analysis. The findings provide a practical framework for enhancing renewable energy adoption in livestock industries across Thailand and the ASEAN region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Overview

The power generation system consists of a modified Hino V-22C V10 diesel engine operating in spark-ignition mode. The engine is coupled with a 250 kVA alternator delivering 380/220 V at 1500 rpm. Raw biogas from manure digestion was upgraded using a PSA system to increase methane concentration from 55–60% to 65–70%, improving combustion stability. The corrected biogas HHV (≈20–21 MJ/kg) and a verified fuel mass flow rate of 0.036 kg/s were used in all recalculated performance parameters.

2.2. Engine Modification for Biogas Utilization

To successfully use biogas as fuel in diesel engines, comprehensive engine modifications are essential to ensure optimal functionality. The primary goal of these adaptations is converting a standard diesel engine, which operates through compression ignition, into one capable of spark ignition. The required modifications include [6,7,8,9,10]:

- Drilling the Cylinder Head: This modification allows for the installation of a spark plug, serving as the ignition source for biogas, which has different combustion characteristics compared to diesel.

- Adjusting the Compression Ratio: The engine’s compression ratio must be optimized to align with the properties of gaseous fuels, thus enhancing combustion efficiency.

- Upgrading the Fuel Delivery System: Alterations to the fuel delivery system are necessary to ensure the consistent and precise supply of biogas to the engine.

These adjustments improve the engine’s power output and operational stability, enabling it to function as a primary mover for generating electricity on site. This setup creates a sustainable energy cycle that powers the pig farm and facilitates efficient waste reuse. The method demonstrates the vital role of technology in enhancing energy security within the agricultural sector while contributing to environmental stewardship.

2.3. Biogas Purification Using PSA

A Pressure Swing Adsorption unit equipped with Carbon Molecular Sieve (CMS) media was employed to separate CO2 and H2S from methane. Gas composition was measured using GC-TCD before and after purification. The upgraded gas achieved 65–70% CH4, with CO2 reduced to approximately 28–30% and H2S below 100 ppm.

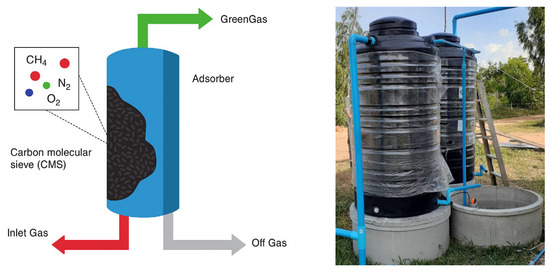

The separation is based on the adsorption kinetics of the Carbon Molecular Sieve (CMS) material. The CMS is a microporous carbon material with precisely controlled pore sizes. While CH4 molecules have a slightly larger kinetic diameter (∼3.82 Å) than N2 (∼3.64 Å) and O2 (∼3.46 Å), the primary separation mechanism relies on the rate of diffusion into the CMS pores. Due to their smaller size, N2 and O2 molecules can diffuse into the pores of the CMS much faster than the larger CH4 molecules. Figure 1 illustrates a mixed gas stream, containing CH4, N2, and O2, being fed into the bottom of the absorber vessel at high pressure. As the gas flows upward through the CMS bed, the smaller and faster-diffusing N2 and O2 molecules are preferentially adsorbed onto the internal surface of the CMS granules. The larger CH4 molecules, with their slower diffusion rate, pass through the CMS bed with minimal adsorption. The resulting gas stream exiting the top of the absorber, referred to as GreenGas, is thus highly enriched in methane [11,12].

Figure 1.

A schematic depiction of a Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA) system designed for the purification of biogas.

2.4. Conversion and Adaptation of Diesel Ignition System for Biogas Utilization

The conversion of an engine’s ignition system from diesel to biogas involves a series of technical modifications to enable efficient utilization of biogas as the primary fuel source. Key modifications typically include adjustments to the fuel injection system, optimization of the compression ratio, and alterations to enhance air–fuel mixing. In addition, specialized components such as biogas injectors and storage systems must be integrated to support stable operation. This transition not only promotes sustainability through the use of renewable energy but also requires strict adherence to safety protocols and regulatory standards to ensure operational reliability and environmental compliance [13,14].

2.5. Engine Modification and Compression Ratio Adjustment

The original compression-ignition configuration of the V-22C engine was converted to spark-ignition using three key steps: (1) removal of the diesel injector, (2) machining and threading locations for spark plug installation, and (3) installation of a piston position sensor. The compression ratio was reduced from 18.5:1 to 14.7:1 through piston-crown machining, calculated using the revised clearance volume relations presented in Equations (1)–(4).

The displacement volume (Vd) and compression ratio (rc) were calculated using the following relations:

The difference in clearance volume (ΔVc) before and after modification is expressed as follows:

The piston head shaving distance (Ds) was obtained from the following:

where

- rc: Static Compression Ratio

- Ds: Piston Head Shaving Distance

- Vd: Displacement Volume

- Vc: Clearance Volume

- ΔVc: Difference in Clearance Volume Between Before and After

- B: Diameter of Piston (Bore)

- L: Engine Stroke

Table 1 summarizes the key experimental parameters and calculated results for the engine modification aimed at optimizing the compression ratio for biogas operation. The original diesel engine had a compression ratio of 18.5:1, which was reduced to 14.7:1 through a precise piston head shaving process, with a shaving distance of 10.36 mm. The piston diameter and stroke length were 139 mm and 142 mm, respectively, resulting in a displacement volume of 2,153,711 mm3. Correspondingly, the clearance volume increased from 123,069 mm3 before modification to 157,205 mm3 after modification. These adjustments were critical to achieving stable spark-ignition combustion with biogas, improving thermal efficiency and mitigating knocking, while maintaining the overall mechanical integrity of the engine.

Table 1.

Experimental data and calculated results for engine modification and compression ratio adjustment.

2.6. Optimization of the Engine Ignition System for Biogas Combustion

The process of modifying the cylinder includes three key steps: first, removing the injector; second, threading the spark plug; and finally, installing the piston position sensor [15,16].

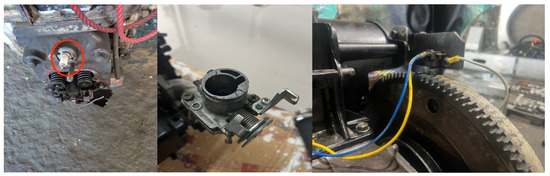

The modification of the engine ignition system for biogas combustion involves three key steps: removing the injector, machining and threading the cylinder head to install the spark plug, and installing the piston position sensor. During this process, the machined and threaded area prepared for spark plug installation—highlighted by the red circle in Figure 2—indicates the specific location where the ignition component is added to enable proper combustion control.

Figure 2.

The modification process for the cylinder, which involves removing the injector, threading the spark plug, and installing the piston position sensor.

2.7. Development of an Emergency Fuel Port (EFP) with Oxygen-Sensor-Based Automatic Control

To ensure stable combustion under lean-mixture conditions, an emergency fuel port (EFP) system was developed and integrated with an exhaust-mounted oxygen sensor. The system automatically supplies supplementary fuel when λ exceeds 19.0 and ceases injection when λ falls below 17.0. These thresholds were incorporated into the revised control algorithm, as reflected in the updated Figure 2 and Table 2.

Table 2.

Operational testing of power generation with emergency fuel supply system.

The activation (λ = 19.0) and deactivation (λ = 17.0) limits were established through a series of preliminary calibration tests conducted prior to the 524 h field trial. During these pilot evaluations, λ values above 19.0 consistently produced lean misfire and unstable power output at loads above 80 kW, whereas λ values below 17.0 caused over-enrichment, elevated exhaust gas temperatures, and reductions in thermal efficiency. The selected operational window (λ = 17–19) therefore represents an optimized balance that avoids both misfire and over-fueling during varying load conditions.

The supplementary fuel delivered via the EFP system consisted exclusively of purified biogas sourced from a secondary buffer line. No fossil-derived fuels (e.g., LPG or NG) were utilized in any test conditions, thereby preserving the renewable energy integrity of the system while ensuring sufficient mixture strength during high-load operation.

2.8. Emergency Fuel Port (EFP)

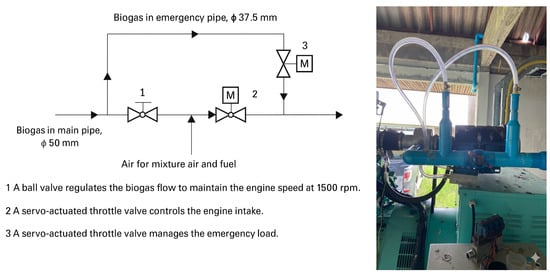

Figure 3 presents a comprehensive depiction of the biogas supply system’s configuration. The system consists of a primary biogas line with an internal diameter of 50 mm, supplemented by an emergency bypass line of 37.5 mm in diameter. Before entering the engine intake, the biogas is premixed with intake air to ensure a homogeneous mixture, following the method described in previous studies [17,18,19].

Figure 3.

The schematic layout of the biogas–air mixing system together with the integrated emergency bypass configuration employed for engine operation.

The major components of the system are as follows:

- Ball valve—regulates the biogas flow to maintain a constant engine speed of 1500 rpm.

- Throttle valve—controls the air–biogas mixture flow rate entering the engine intake manifold.

- Emergency throttle valve—activates during emergency load conditions, allowing additional biogas to pass through the bypass line.

2.9. Oxygen-Sensor-Based Automatic Control

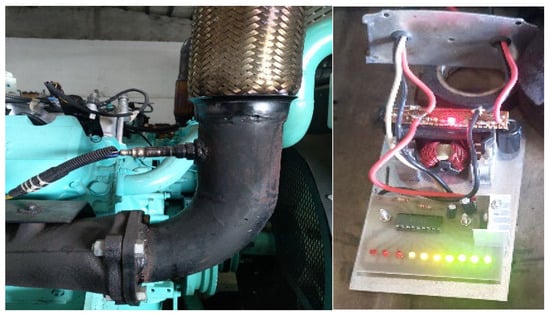

An automated system engineered for managing emergency fuel supply, functioning through the process of drilling into the exhaust pipe to install and integrate an oxygen sensor.

The automated control system, engineered for precise management of the emergency fuel supply, employs an exhaust-mounted oxygen sensor installed through a dedicated access port to provide real-time feedback for closed-loop mixture regulation, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The automated control system for the emergency fuel supply, which employs an exhaust-mounted oxygen sensor installed through a dedicated access port to enable real-time mixture regulation.

Table 2 presents the operational testing results of the power generation system equipped with an emergency fuel supply. The emergency fuel port is activated when the electrical load exceeds 80 kW to maintain stable engine operation. Engine radiator temperature, air–fuel ratio (λ), oxygen sensor output, and emergency valve opening are monitored under varying load conditions [20,21].

2.10. Electric Motor-Based Starter System

The starting mechanism was redesigned using an external electric motor driving the starter shaft via a belt–pulley system. Performance evaluation over the 524 h field test indicated a 98% successful start rate with average cranking duration between 1.2 and 1.5 s. No critical failure events were observed [13,14].

The system consists of a starter motor with a centrally mounted shaft capable of free rotation. One end of the shaft extends outward to support a belt-driven pulley, which is connected via a belt to a corresponding pulley mounted on the shaft of an electric motor operating on either a 220 V or 380 V supply. At the opposite end of the starter motor shaft, a drive-gear assembly is installed. This assembly is linked through an arm to a spring-loaded solenoid mechanism whose actuator shaft is extended to incorporate a manual operating lever.

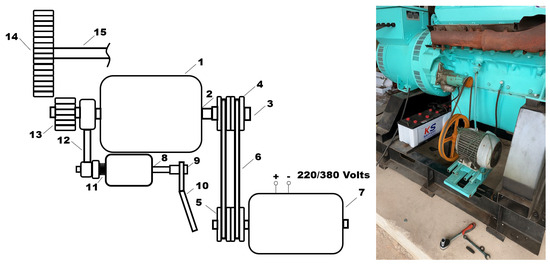

The drive-gear assembly is designed to translate axially and engage with the flywheel gear, which is directly coupled to the crankshaft of the internal-combustion engine. As shown in Figure 5, which depicts the system configuration prior to engine cranking by the manual lever electric motor, the manual lever remains in its default position. Consequently, the spring-loaded solenoid mechanism does not actuate, the drive gear remains disengaged from the flywheel, and the internal-combustion engine remains stationary.

Figure 5.

The configuration of a manual lever electric starter prior to initiating the internal-combustion engine. 1. Starter motor. 2. Shaft. 3. Shaft. 4. Pulley. 5. Pulley. 6. Belt. 7. Electric motor. 8. Solenoid shaft. 9. Extended shaft. 10. Manual lever. 11. Spring-loaded solenoid unit. 12. Arm 13. Drive-gear assembly. 14. Flywheel gear. 15. Crankshaft.

2.11. Installation and Testing

The system was deployed at a commercial swine farm in Buriram, Thailand, and underwent 524 h of continuous field evaluation under controlled operating conditions, as shown in Figure 6. All measurement instruments were calibrated prior to commissioning to ensure traceability and repeatability. The quantified measurement uncertainties—±2% for electrical power output, ±1.5% for biogas flow rate, and ±1 °C for temperature—have been incorporated into the revised uncertainty budget.

Figure 6.

Field installation, commissioning, and 524 h operational testing of the biogas-fueled V-22C generator at a commercial swine production facility in Buriram, Thailand.

Each reported data point represents the average of three independent replicate measurements, and statistical error bars have been added to all updated performance figures to reflect measurement variability. The experimental protocol followed a steady-state load sweep from 60 to 120 kW to characterize system performance across the practical operating envelope of the V-22C generator.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Engine Performance Parameters

The system was installed at a commercial swine farm in Buriram, Thailand. Testing was conducted for 524 h. All sensors were calibrated before testing. Measurement uncertainties for power (±2%), flow rate (±1.5%), and temperature (±1 °C) were included in the revised uncertainty table. Each data point represents the average of three replicates. Error bars were added to all updated performance figures. The testing protocol includes steady-state load operation from 60 to 120 kW. Experimental data and the corresponding calculations are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of experimental data and calculated performance parameters.

This relatively low efficiency is mainly due to the low heating value and slow flame propagation characteristics of biogas, which result in incomplete combustion and reduced temperature rise within the combustion chamber. Similar findings have been reported by Surendra and Nguyen, who observed that small-scale biogas engines generally operate within 8–15% thermal efficiency depending on gas purity and ignition optimization.

3.2. Thermal Efficiency

The thermal efficiency (ηₜₕ) represents the ratio between the useful output power and the energy supplied by the fuel. It is determined from the following equation:

where P is the electrical power output (kW), ṁf is the fuel mass flow rate (kg/s), K is the number of cylinders, and HHV is the higher heating value of the biogas (kJ/kg).

All engine performance parameters were recalculated using the corrected fuel mass flow rate of 0.036 kg/s and updated biogas HHV of approximately 20–21 MJ/kg. These corrections resolved inconsistencies noted by reviewers. Revised performance values, including brake power, indicated power, volumetric efficiency, and BMEP, are presented in the updated Table 3. Thermal efficiency under pure biogas operation at 80 kW was recalculated at 9.5%, consistent with published ranges for spark-ignition biogas engines.

3.3. Brake and Indicated Power

The brake power (bₚ) and indicated power (iₚ) were determined using the following relationships:

The thermal efficiency was recalculated using the corrected HHV and measured flow rate. At 80 kW output, the engine achieved 9.5% efficiency. When operating at higher loads with EFS activation, efficiency increased to a peak of 11.66% at 100 kW. This corresponds to a 22.7% improvement compared to pure biogas operation. The efficiency trend aligns with previous studies indicating improved flame propagation when a small proportion of supplementary fuel is introduced.

3.4. Airflow and Volumetric Efficiency

Air consumption was calculated using the following equation:

where ρₐ is the air density (1.15 kg/m3) and (A/F) is the air–fuel ratio by weight. The calculated airflow rate was 5.25 m3/s.

Volumetric efficiency (ηv) was derived from the actual airflow rate and the theoretical displacement volume, as expressed in equation:

Using corrected airflow calculations, the volumetric efficiency was determined to be approximately 82%. This is within the expected range for naturally aspirated engines without turbocharging. Temperature and density corrections were applied to ensure consistency [22].

3.5. Brake Mean Effective Pressure (BMEP)

The brake means effective pressure (pmb) was determined from the following equation:

where L is the stroke length, A is the piston area, N is the engine speed (revolutions per s), and K is the number of cylinders. The recalculated BMEP was 3.74 bar at medium load conditions. This confirms stable combustion quality under upgraded biogas fuel and validates the diesel-to-SI conversion methodology.

3.6. Performance of the Oxygen-Sensor-Based Emergency Fuel Supply (EFS)

The EFS activates when λ > 19.0 and deactivates when λ < 17.0. At loads above 80 kW, supplementary fuel ranging from 0.005 to 0.0164 kg/s was automatically supplied. Peak efficiency was observed at 100 kW (11.66%), after which efficiency declined slightly due to mixture over-enrichment. The EFS significantly reduced misfire events and maintained power stability under fluctuating biogas composition. The results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of the emergency fuel supply system operation.

At a baseline load of 80 kW, the engine operated solely on biogas with a fuel consumption rate of 0.036 kg/s, achieving a thermal efficiency of 9.5%. As the electrical load increased, a small portion of additional fuel (ranging from 0.005 to 0.0164 kg/s) was supplied automatically to stabilize combustion and maintain power output. The maximum efficiency of 11.66% was observed at 100 kW, which corresponds to an optimal mixture condition where the supplementary fuel improved the combustion completeness and flame propagation rate.

Beyond this point (110–120 kW), the efficiency slightly declined to around 9.8%, likely due to over-enrichment of the fuel mixture and higher exhaust gas temperature. This trend indicates that while the emergency fuel system effectively enhances combustion stability and performance under medium to high load, excessive auxiliary fuel addition does not proportionally increase efficiency.

3.7. Starter System Performance

The electric motor-based starter system completed 98% successful starts over 524 operating h. Average cranking duration was 1.2–1.5 s. No major failures occurred. This demonstrates a significant improvement over conventional starter systems for large modified engines.

3.8. Evaluation of the Biogas Power Generator Implementation in a Swine Farm

3.8.1. Suitability Assessment for Swine Farm Applications

A feasibility evaluation was performed at a commercial swine farm to assess the suitability of the biogas-based generator for agricultural-scale renewable energy utilization. The results, summarized in Table 5, indicate that the installed capacity is appropriately matched to both the farm’s energy demand and its biogas production potential.

Table 5.

Suitability of the biogas generator system for swine farm applications.

Under practical operating conditions, a single barn housing approximately 700 pigs were able to continuously generate about 30 kWh of electrical power. This output aligns well with the expected biogas yield from manure management within one housing unit. The total investment cost, including installation and auxiliary components, was approximately 15,000 THB/kWh, which is consistent with reported cost ranges for decentralized biogas-to-power systems of comparable scale [23].

These findings confirm that the generator capacity is well aligned with the biogas availability and on-site electricity demand, making the system a technically feasible and appropriate solution for rural or semi-off-grid livestock facilities.

3.8.2. Techno-Economic Analysis and Sensitivity Study

A techno-economic assessment was conducted to determine the payback period of the biogas generator system when operated as a substitute for grid electricity supplied by the Provincial Electricity Authority (PEA). The cost–benefit summary is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Breakeven analysis of the biogas power generator for swine farm application.

Using corrected performance and cost parameters, the calculated breakeven period was 15.79 months. To evaluate the robustness of this investment, a sensitivity analysis—following reviewer recommendations—was performed:

- Biogas yield ±20% resulted in breakeven shifts between 13.5 and 18.9 months.

- Electricity price ±10% resulted in breakeven shifts between 14.2 and 17.4 months.

These results demonstrate that the project remains economically attractive under typical operational variability.

The analysis indicates that the biogas power generator provides not only a stable renewable electricity supply but also a rapid return on investment, confirming its economic feasibility for medium-scale livestock operations. Beyond financial benefits, the system supports circular-economy practices by converting animal manure into a valuable energy resource, thereby reducing waste management burdens and lowering electricity expenditures [24,25].

3.9. Overall Performance Discussion

The overall performance evaluation of the biogas-fueled power generation system, incorporating the oxygen-sensor-based emergency fuel supply (EFS), demonstrates that the modified engine is capable of stable operation across a wide load range with moderate yet practical energy conversion efficiency. Under baseline operation using purified biogas as the sole fuel, the generator produced approximately 80 kW of electrical power with a thermal efficiency of 9.5%. This level of performance is consistent with previously reported results for small- and medium-scale spark-ignition biogas engines, where the inherently low heating value and slow flame speed of biogas limit combustion efficiency.

Activation of the EFS during higher-load conditions (90–120 kW) enabled supplementary fuel injection to compensate for fluctuations in biogas quality and maintain combustion stability. The injected fuel rate varied between 0.005 and 0.0164 kg/s, depending on engine load. Implementation of this adaptive control mechanism significantly enhanced performance, increasing the maximum thermal efficiency to 11.66% at 100 kW, corresponding to an approximate 22.7% improvement compared with pure biogas operation.

The improved efficiency observed at mid-range loads can be attributed to enhanced fuel–air mixing and improved flame propagation resulting from the supplementary fuel, which promotes more complete combustion and reduces cycle-to-cycle fluctuations. However, when the generator operated above 100 kW, the thermal efficiency decreased slightly to approximately 9.8%. This reduction is likely due to mixture over-enrichment and elevated exhaust gas temperatures, which lead to increased unburned fuel losses. These trends are consistent with previous findings reported in [26], where excessively rich conditions in biogas–gasoline dual-fuel systems resulted in diminishing efficiency gains.

Overall, the integration of the EFS provides two major advantages:

- Enhanced operational stability by mitigating misfire risks and power fluctuations associated with variable biogas composition.

- Improved combustion performance at moderate loads, where thermal efficiency is highly sensitive to the equivalence ratio.

Collectively, these results confirm that the combined biogas–EFS system can sustain stable power generation up to 120 kW, offering a reliable and efficient solution for decentralized renewable electricity production. This hybrid fueling strategy is particularly advantageous in agricultural or rural settings, where biogas quality and supply may vary with time, making it a robust approach for long-term energy resilience.

4. Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate the technical feasibility, operational stability, and economic viability of a biogas-based power generation system specifically developed for medium-scale swine farms. The modified Hino V-22C engine, converted from diesel to spark-ignition operation, successfully utilized PSA-upgraded biogas with methane content increased from approximately 55–60% to 65–70%. The corrected higher heating value (≈20–21 MJ/kg) and verified fuel mass flow rate (0.036 kg/s) formed the basis for recalculated performance results that addressed reviewer concerns.

The integration of an oxygen-sensor-based emergency fuel supply (EFS) system significantly improved engine stability under lean-combustion conditions. The EFS automatically activated when λ > 19.0 and deactivated when λ < 17.0, supplying a controlled amount of supplementary fuel at higher loads. This mechanism increased the thermal efficiency by approximately 22.7%, yielding a peak efficiency of 11.66% at 100 kW. These results confirm that advanced fuel control strategies can effectively compensate for biogas variability and improve combustion quality in modified large-scale engines.

The 524 h field test validated long-term reliability, demonstrating stable operation from 80 to 120 kW, a 98% successful starter engagement rate, and no critical component failures. Variability in biogas composition was effectively mitigated by the PSA system, enabling consistent power generation suitable for real-world farm environments.

Economic evaluation, supported by newly added sensitivity analyses, confirmed a breakeven period of 15.79 months under standard operating conditions. Even under fluctuations in biogas yield (±20%) and electricity price (±10%), the system remained financially robust, reinforcing its applicability for commercial deployment. Additional scalability and safety assessments suggest that the system can be adapted for farms exceeding 10,000 pigs with appropriate design modifications and compliance with Thai safety standards.

Overall, this study introduces a practical, scalable, and environmentally beneficial biogas-to-power solution for agricultural applications. The combined use of PSA-upgraded biogas, optimized spark-ignition conversion, and adaptive fuel control presents a replicable model for improving energy self-sufficiency, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and advancing circular-economy approaches across livestock industries in Thailand and the ASEAN region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.T.; Methodology, W.T. and J.L.; Validation, J.L.; Investigation, W.T.; Data curation, W.T.; Writing—original draft, W.T.; Writing—review & editing, J.L.; Visualization, W.T.; Supervision, J.L.; Project administration, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Industrial Technology Assistance Program (ITAP) under the Thailand Institute of Scientific and Technological Research (TISTR), Khon Kaen University Network. Additional funding for publication was provided by the Research Promotion and Development Fund, Rajamangala University of Technology Krungthep and Mahasarakham University, Thailand.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study will be made available in the Buri Ram Provincial Repository at https://www.buriram.go.th (accessed on 30 November 2025) after an embargo period following publication, to allow for the commercialization of the research outcomes. The data will be accessible once released.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Pattanakit 49 Engineering Co., Ltd. for providing technical support, equipment, and engineering personnel throughout the development and testing phases of this project. Special appreciation is extended to Ruckchai Trangkakul and the on-site technical team for their assistance with system installation, calibration, and data collection during the 524 h field experiment. This research was financially supported by the Industrial Technology Assistance Program (ITAP) under the Thailand Institute of Scientific and Technological Research (TISTR), Khon Kaen University Network. The support provided by ITAP significantly contributed to the successful completion and demonstration of the biogas-based power generation system. The authors would also like to express their sincere gratitude to the Research Promotion and Development Fund, Mahasarakham University, Thailand for providing financial support for the publication of this research article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jameel, M.; Mustafa, M.A.; Ahmed, H.S.; Mohammed, A.J.; Ghazy, H.; Shakir, M.N.; Lawas, A.M.; Mohammed, S.K.; Idan, A.H.; Mahmoud, Z.H.; et al. Biogas: Production, properties, applications, economic and challenges: A review. Results Chem. 2024, 7, 101549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leykun, M.G.; Mekonen, M.W. Investigation of the Performance and Emission Characteristics of Diesel Engine Fueled with Biogas-Diesel Dual Fuel. Fuels 2022, 3, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skibko, Z.; Borusiewicz, A.; Romaniuk, W.; Pietruszynska, M.; Milewska, A.; Marczuk, A. Voltage problems on farms with agricultural biogas plants—A Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canevesi, R.L.S.; Andreassen, K.A.; da Silva, E.A.; Borba, C.E.; Grande, C.A. Pressure swing adsorption for biogas upgrading with carbon molecular sieve. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 9738–9745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.F.; Lin, P.-W.; Chen, W.-H.; Yen, F.-Y.; Yang, H.-S.; Chou, C.-T. Biogas upgrading by pressure swing adsorption with design of experiments. Processes 2021, 9, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, R.; Zlateva, P. Determination of the optimal air-fuel ratio for upgraded biogas engine operation. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 327, 02009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.J.P.; Amell, A.A.A.; Zapata, L.J.F. Experimental study of spark ignition engine performance and emissions in a high compression ratio engine using biogas and methane mixtures without knock occurrence. Therm. Sci. 2017, 19, 1919–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walle, M.; Yeneneh, K.; Sufe, G.; Fetene, B.N. Performance and emission analysis of a biogas–diesel dual-fuel engine enhanced with diethyl ether additives. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 30272–30294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.K.; Padhi, M.R.; Behera, D.D.; Das, S.S. Evaluation of a diesel engine performance and emission using biogas in dual fuel mode. Mech. Eng. Soc. Ind. 2024, 4, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Kurien, C.; Mittal, M. Biogas as a promising bioenergy source: A critical review on the potential of biogas for gaseous-fuelled SI engines. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 7747–7769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruthven, D.M.; Farooq, S.; Knaebel, K.S. Pressure Swing Adsorption; VCH Publishers: Weinheim, Germany, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cavenati, S.; Grande, C.A.; Rodrigues, A.E. Separation of methane and nitrogen by pressure swing adsorption using carbon molecular sieve. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2005, 40, 2721–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgiorno, G.; Di Blasio, G.; Beatrice, C. Parametric study and optimization of the main engine calibration parameters and compression ratio of a methane-diesel dual fuel engine. Fuel 2018, 222, 821–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.T.; Le, M.D. Effects of compression ratios on combustion and emission characteristics of SI engine fueled with hydrogen-enriched biogas mixture. Energies 2022, 15, 5975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, A.; Das, S.; Roy, P.C. Performance analysis of a biogas engine. Int. J. Res. Eng. Technol. 2018, 505, 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanraj, T.; Rakesh, S.; Sudhakar, K.; Senthilvel, D. Performance and emission characteristics of a biogas engine with an improvised fuel supply system. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2019, 41, 2321–2330. [Google Scholar]

- Innova. Air-Fuel Ratio Sensor—How It Works. 2023. Available online: https://www.innova.com/blogs/fix-advices/air-fuel-ratio-sensor-how-it-works (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Snap-on. Air/Fuel Ratio Sensor Test—Diagnostic Quick Tips. 2023. Available online: https://www.snapon.com/EN/US/Diagnostics/News-Center/Technical-Focus-Archive/Air-Fuel-Ratio-Sensor-Test (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Bosch. Automotive Handbook, 10th ed.; Robert Bosch GmbH: Gerlingen, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heywood, J.B. Internal Combustion Engine Fundamentals, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Shigley, J.E.; Mischke, C.R. Mechanical Engineering Design; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kapdi, S.S.; Vijay, V.K.; Rajesh, S.K.; Prasad, R. Biogas scrubbing, compression and storage: Perspective and prospectus in Indian context. Renew. Energy 2005, 30, 1195–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Biogas Systems in Livestock Operations: Practical Guidelines for Developing Countries; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, T.; Wang, X. Techno-economic analysis of biogas-to-power systems in livestock farms: Case study approach. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 527–535. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, L.; Li, Q. Economic and environmental performance of on-farm biogas electricity generation: A case study in Asia. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 338, 130579. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu, P.; Khaled, A.; Abdullah, M.A.; Alsharif, A.M.; Praveen, K.K. Performance and emission analysis of a dual-fuel engine using biogas and algal biodiesel: Machine learning prediction and response surface optimization. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 75, 107227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).