A Comprehensive Review of Data-Driven and Physics-Based Models for Energy Performance in Non-Domestic Buildings

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- Prioritizing Energy Performance of Non-Domestic Buildings: Unlike most studies, which discuss energy modeling of houses or buildings in general, indirectly and projectively, the review at hand aims specifically at non-domestic buildings such as commercial, industrial, and institutional buildings. In so doing, it addresses a critical knowledge gap regarding the specific parameters impacting energy consumption in these gigantic, complex buildings.

- 2.

- Comparative Study of Data-Driven and Physics-Based Models

- 3.

- Emphasis on Data Limitations and Strategies for Practical Model Improvement

- 4.

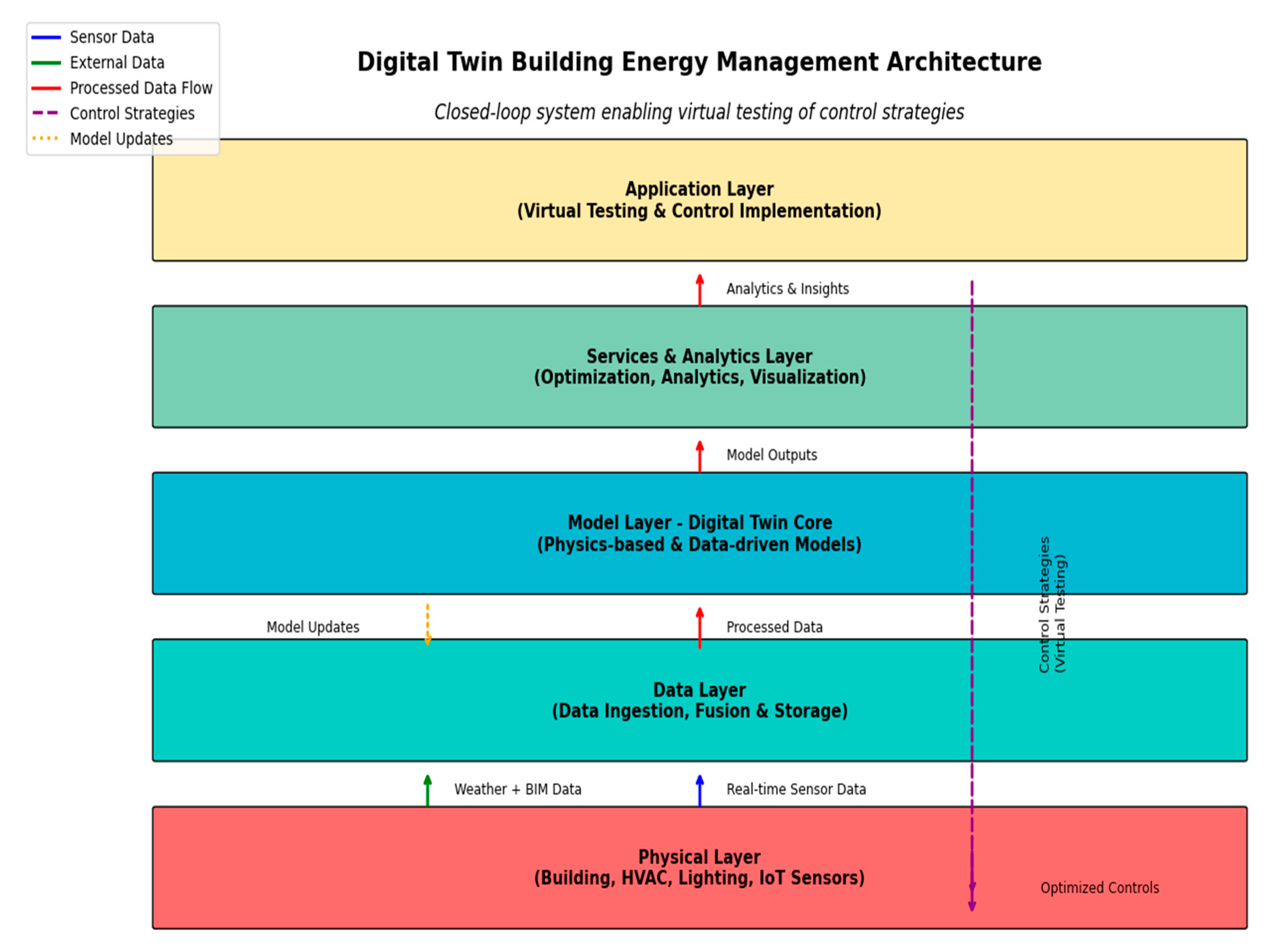

- Integration of New Data Sources for Improved Prediction: The review points to the integration of various data sources, operational data, weather data, and building attributes to improve the accuracy of prediction. It details how big data, IoT sensors, and smart meters can be leveraged to improve energy management systems’ accuracy and scale.

- 5.

- Research Horizons and Literature Gaps

- 6.

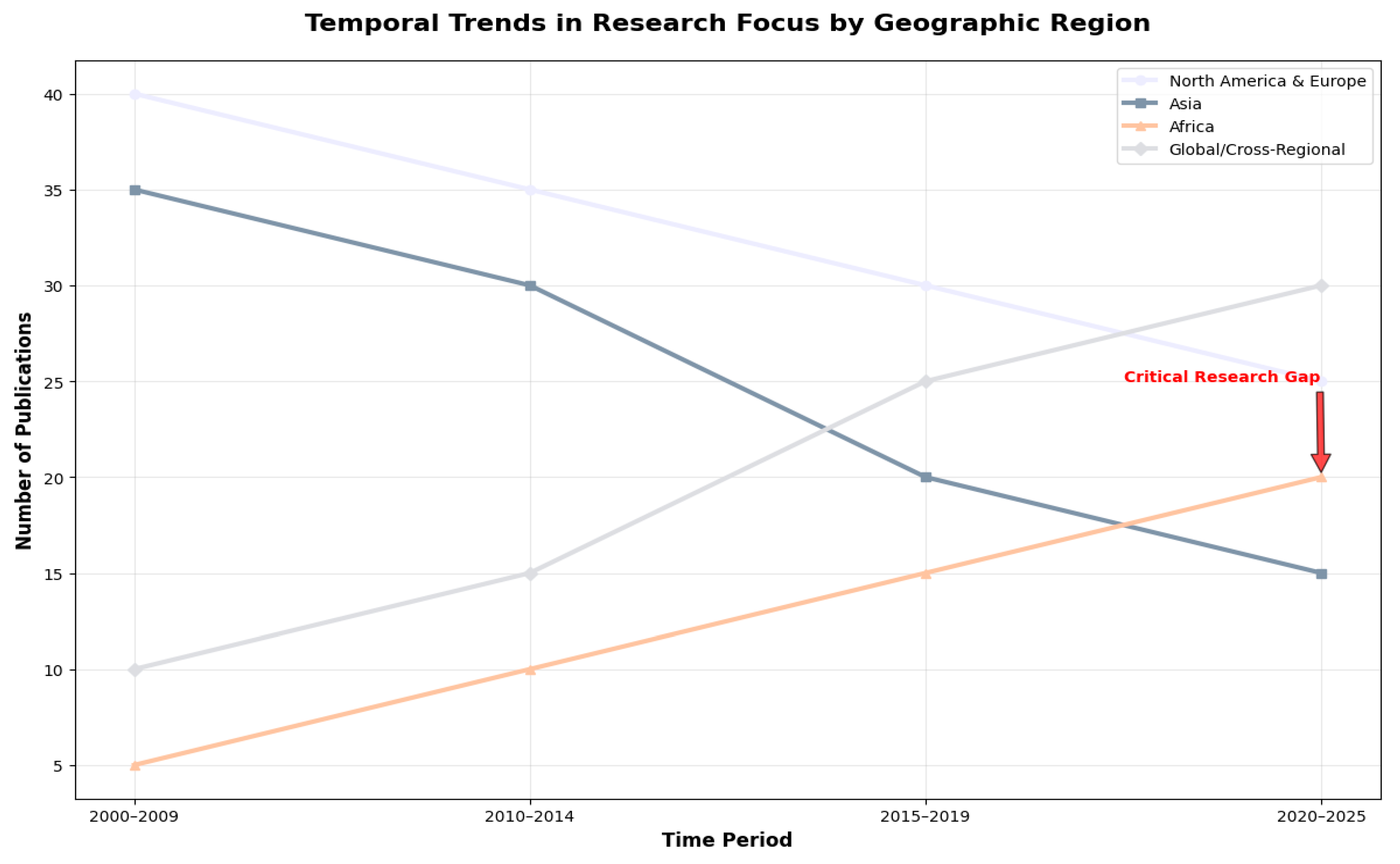

- Regional and Temporal Analysis

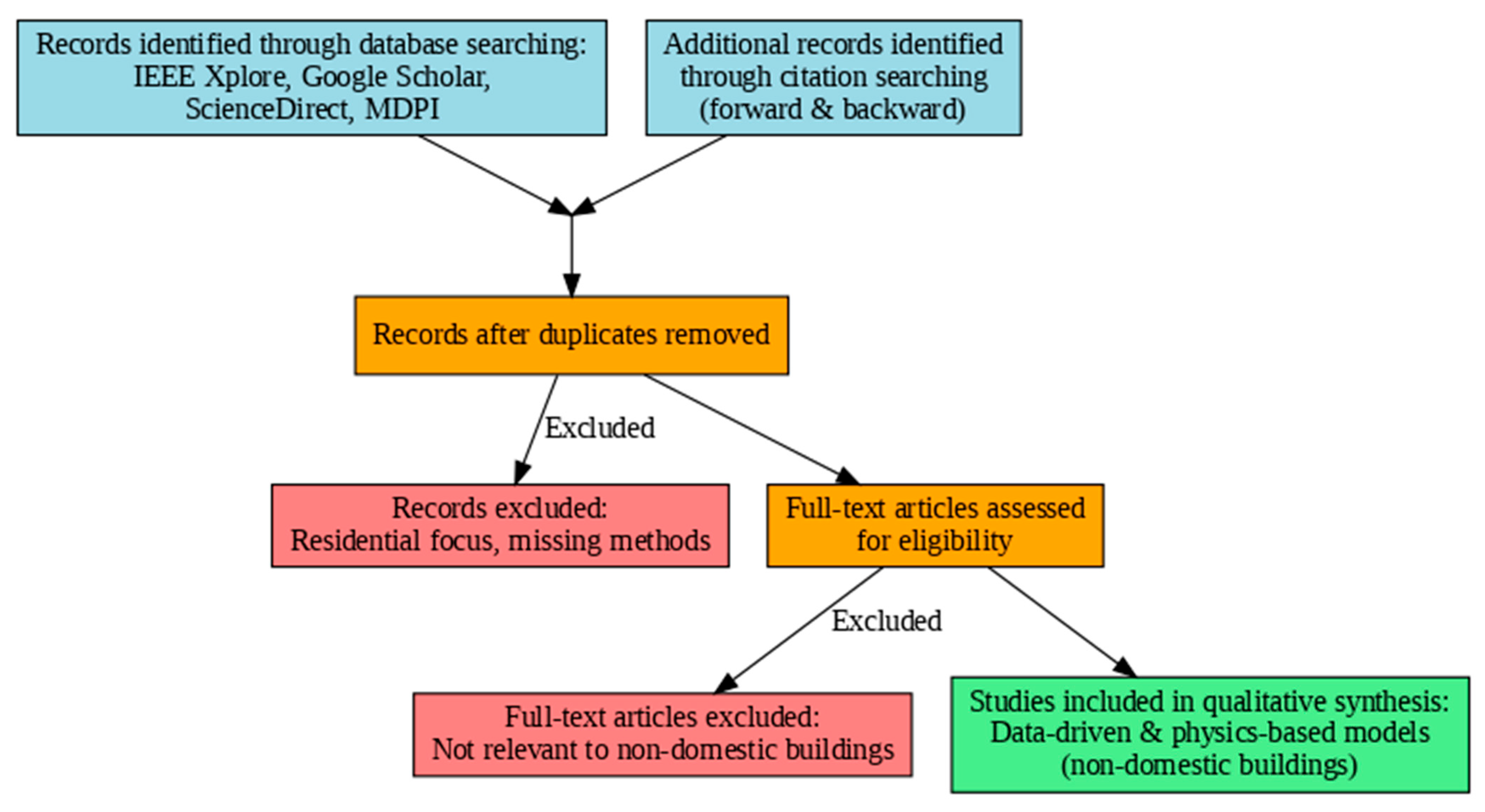

2. Survey of Papers Related to Data-Driven and Physics-Based Models for Energy Performance in Non-Domestic Buildings

2.1. Barriers and Enabling Mechanisms for Improving Energy Performance in Non-Domestic Buildings

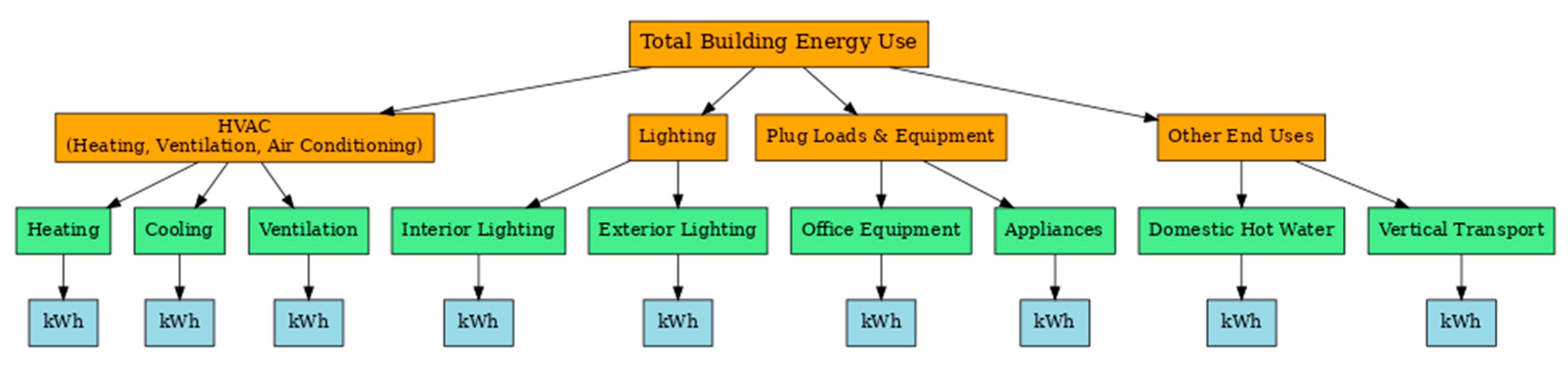

2.2. Building Energy Performance Assessment

2.2.1. Physics-Based Engineering Calculations

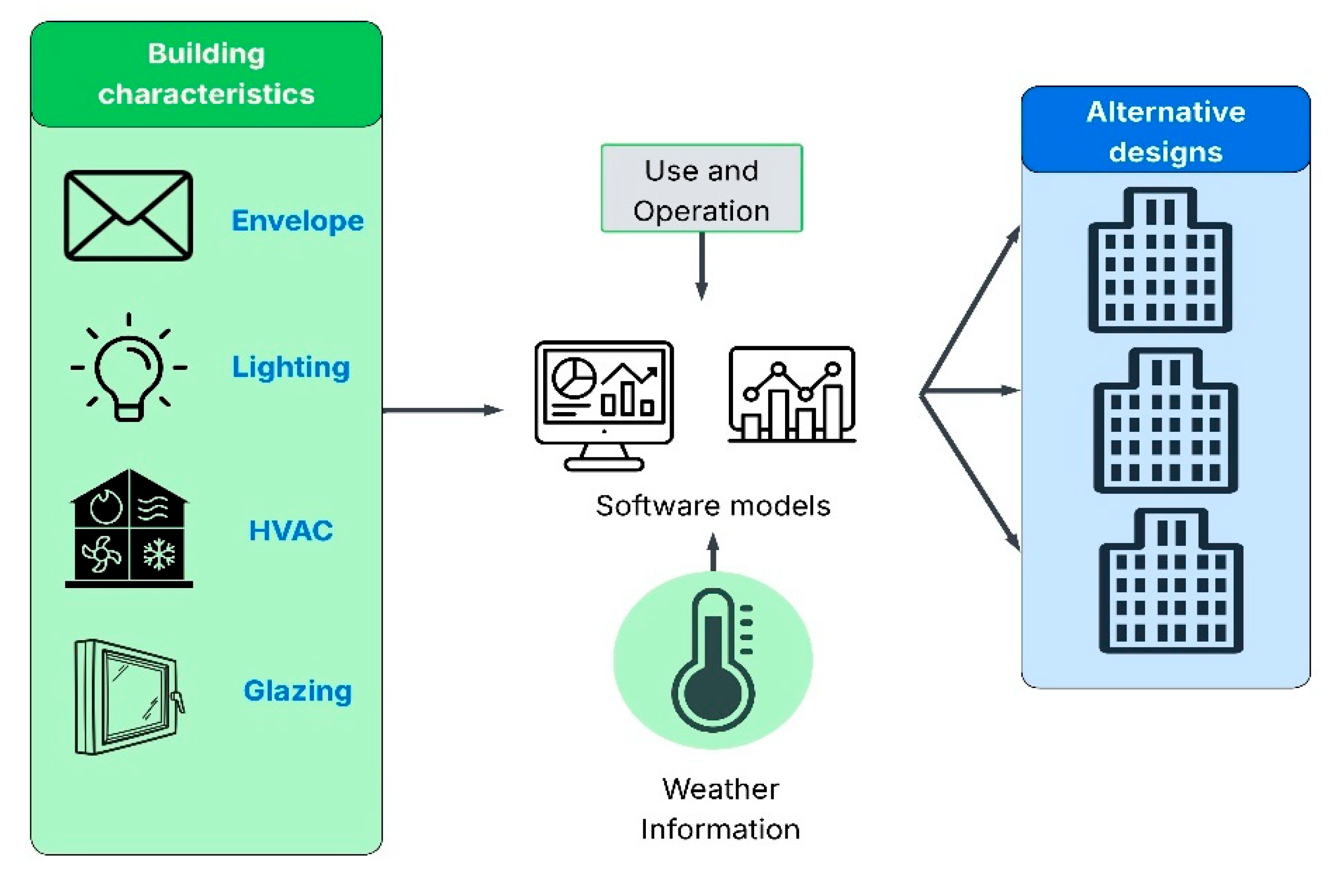

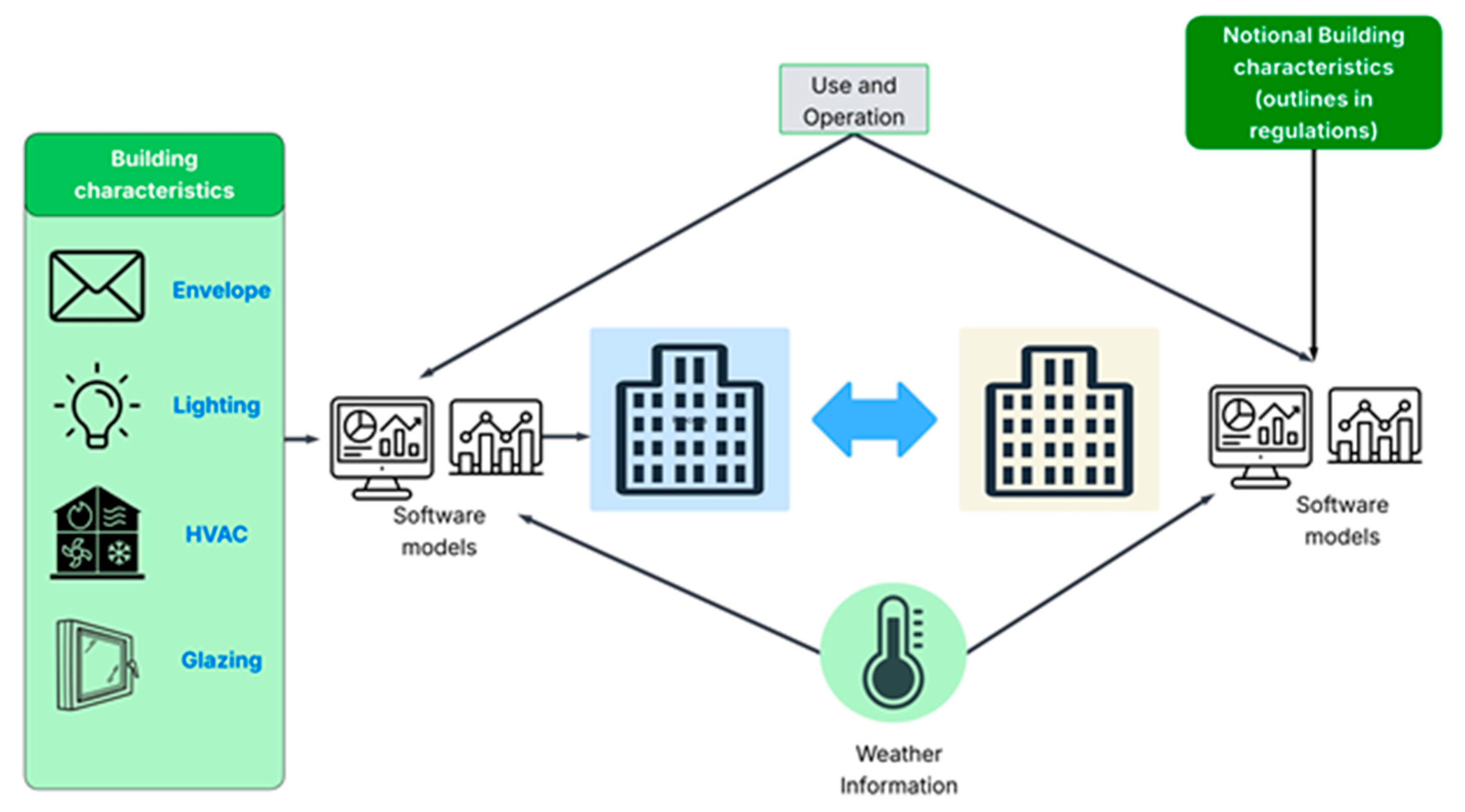

2.2.2. Simulation Method for Energy Performance in Non-Domestic Buildings

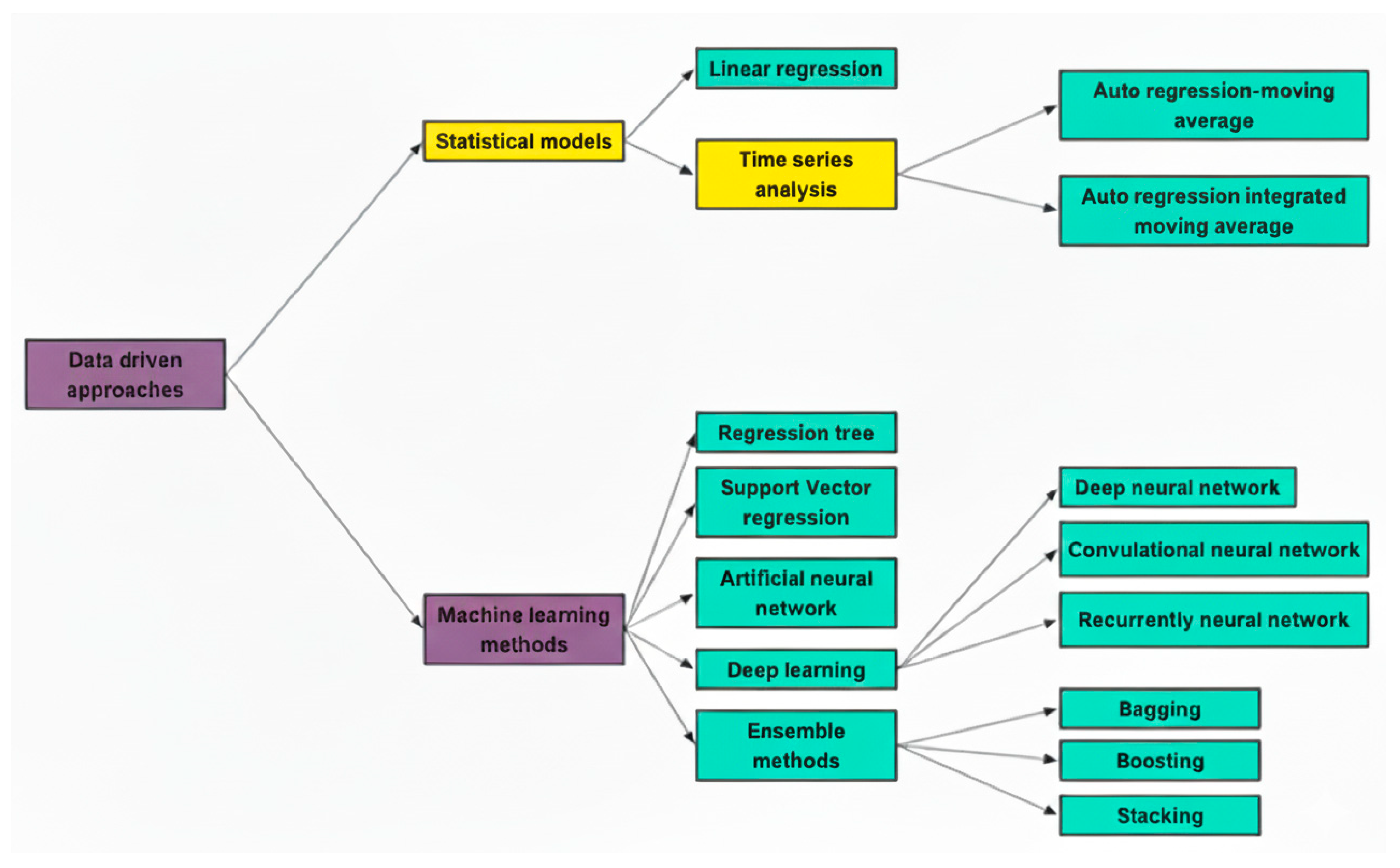

2.2.3. Statistical Models for Energy Performance in Non-Domestic Buildings

2.2.4. Machine Learning for Energy Performance in Non-Domestic Buildings

- (a)

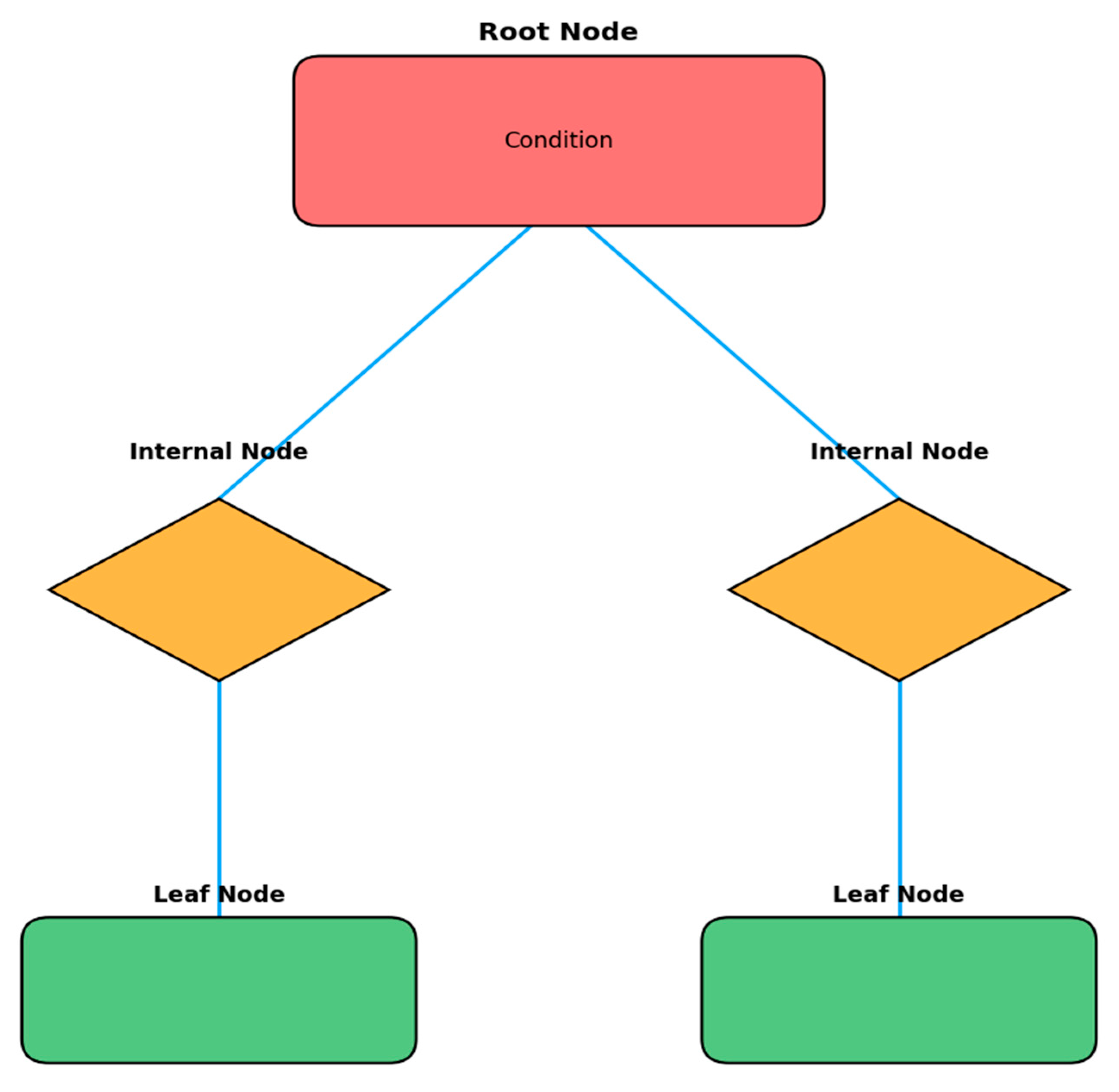

- Classical Machine Learning Approaches

- (b)

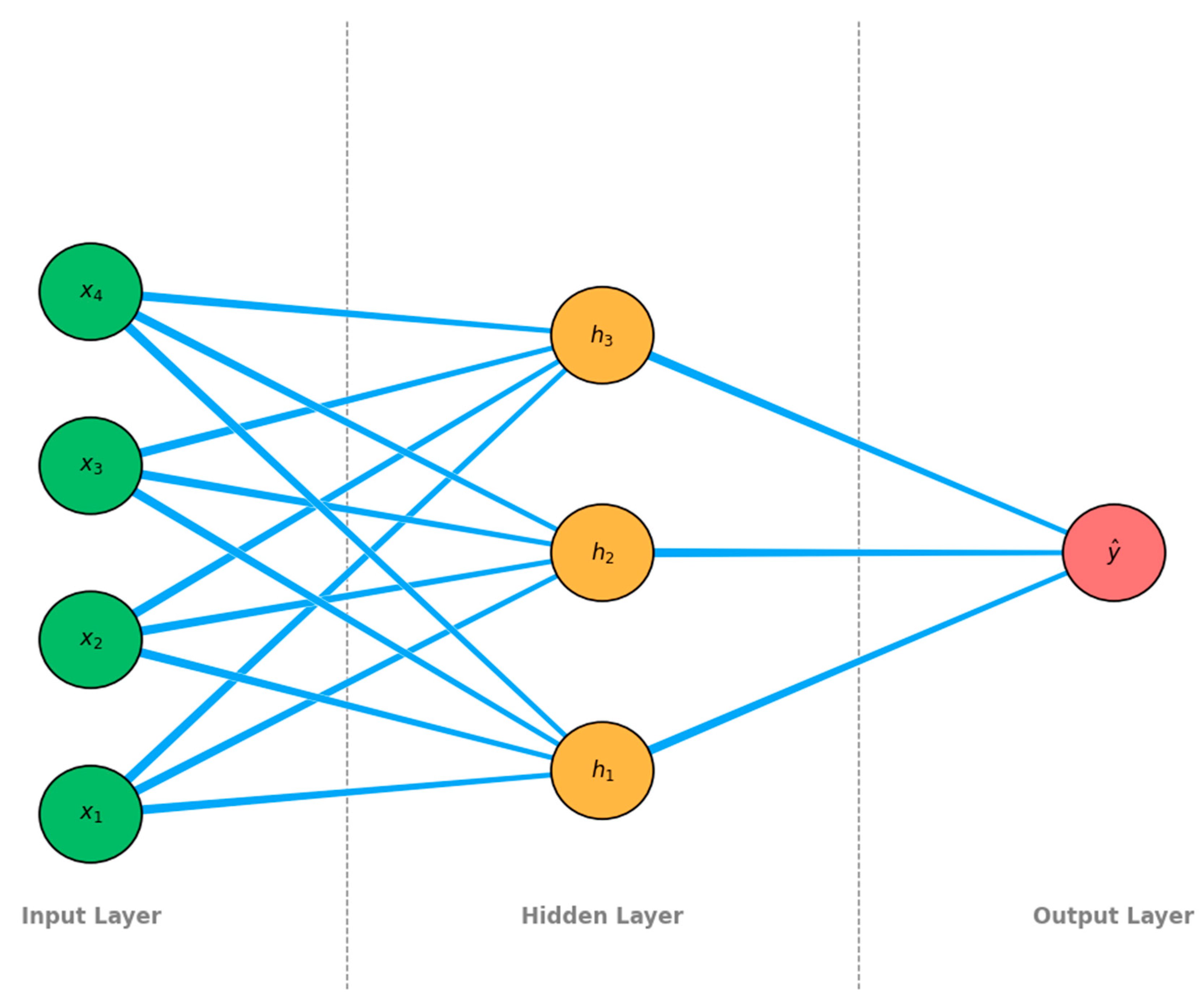

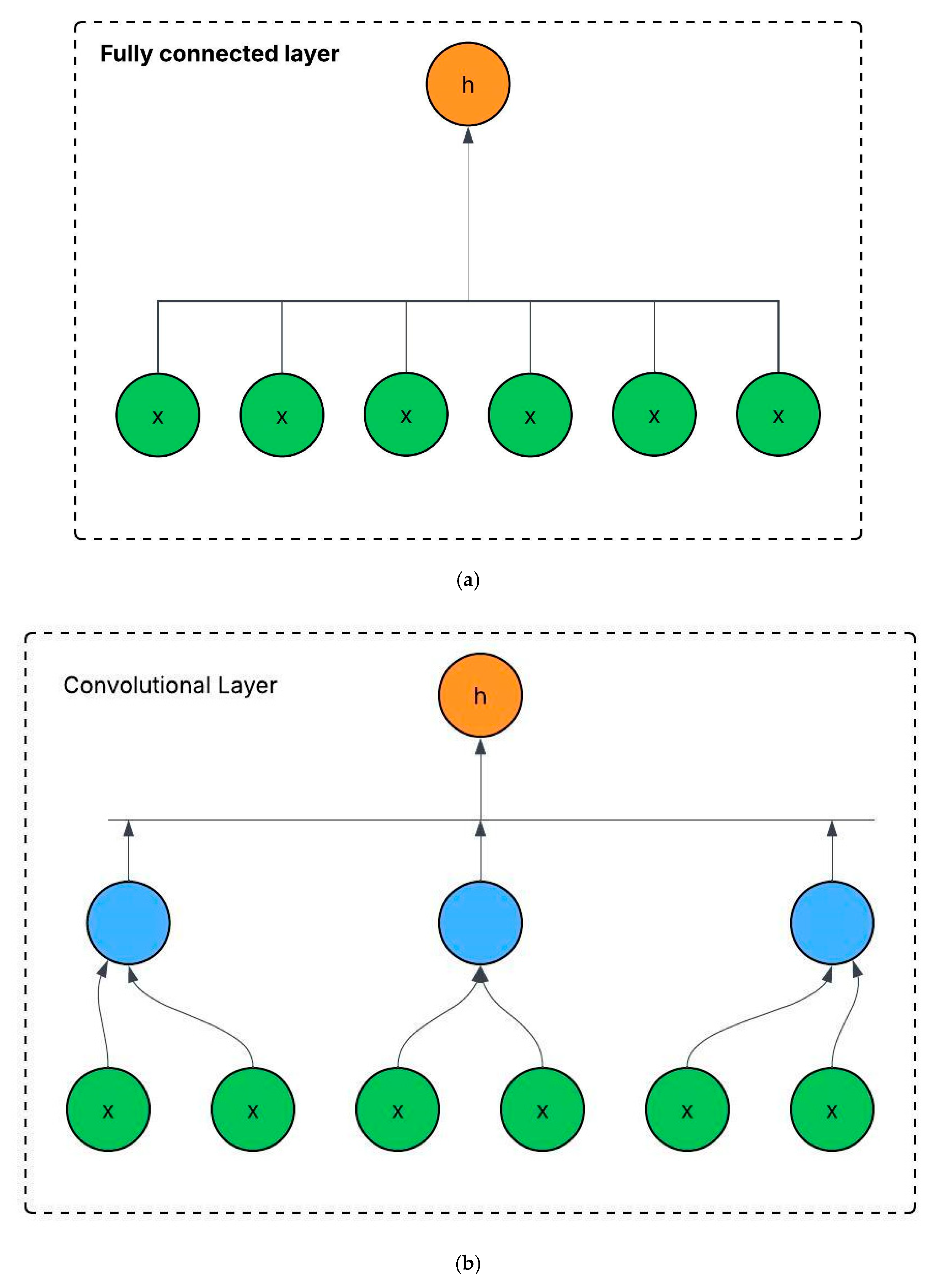

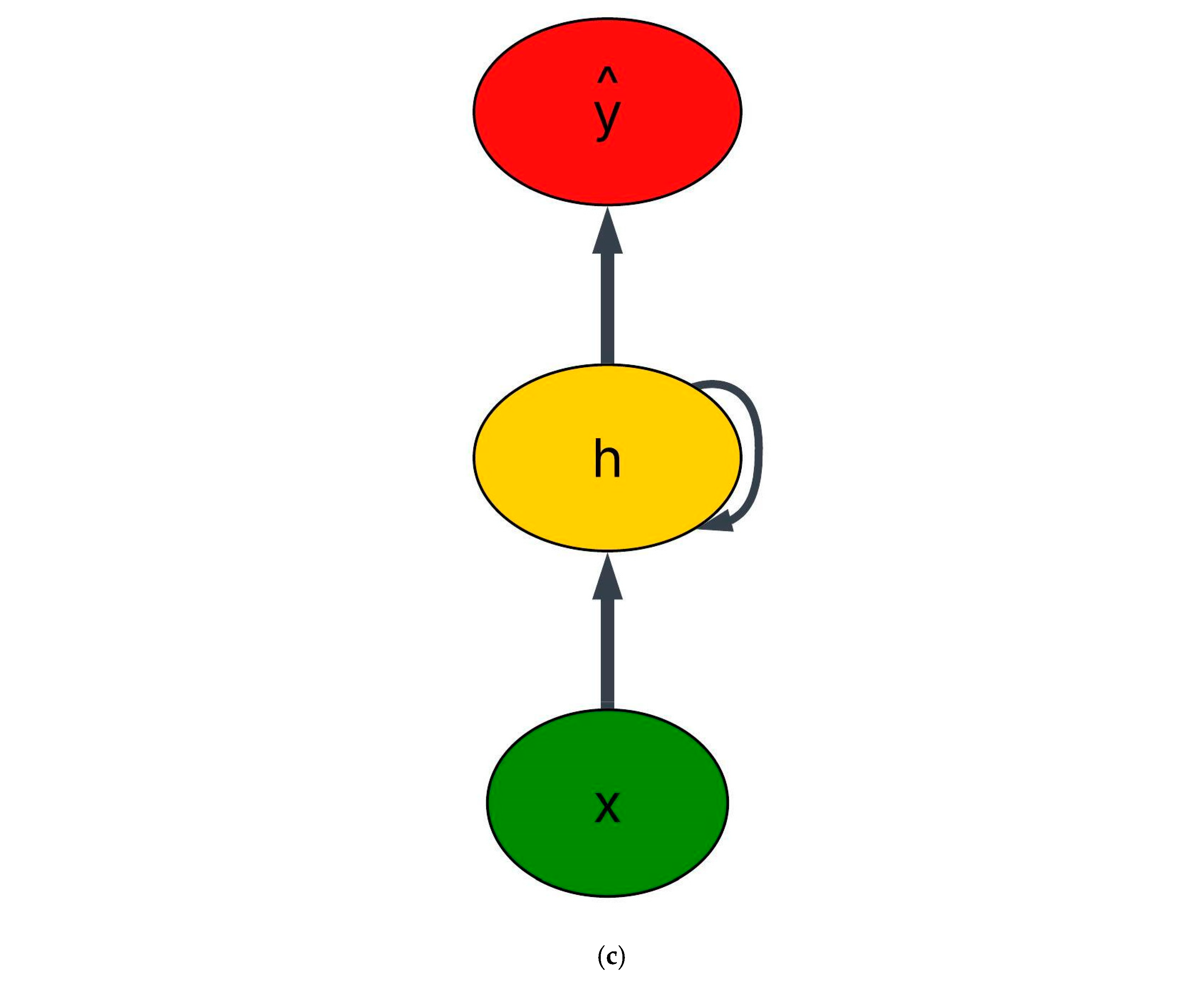

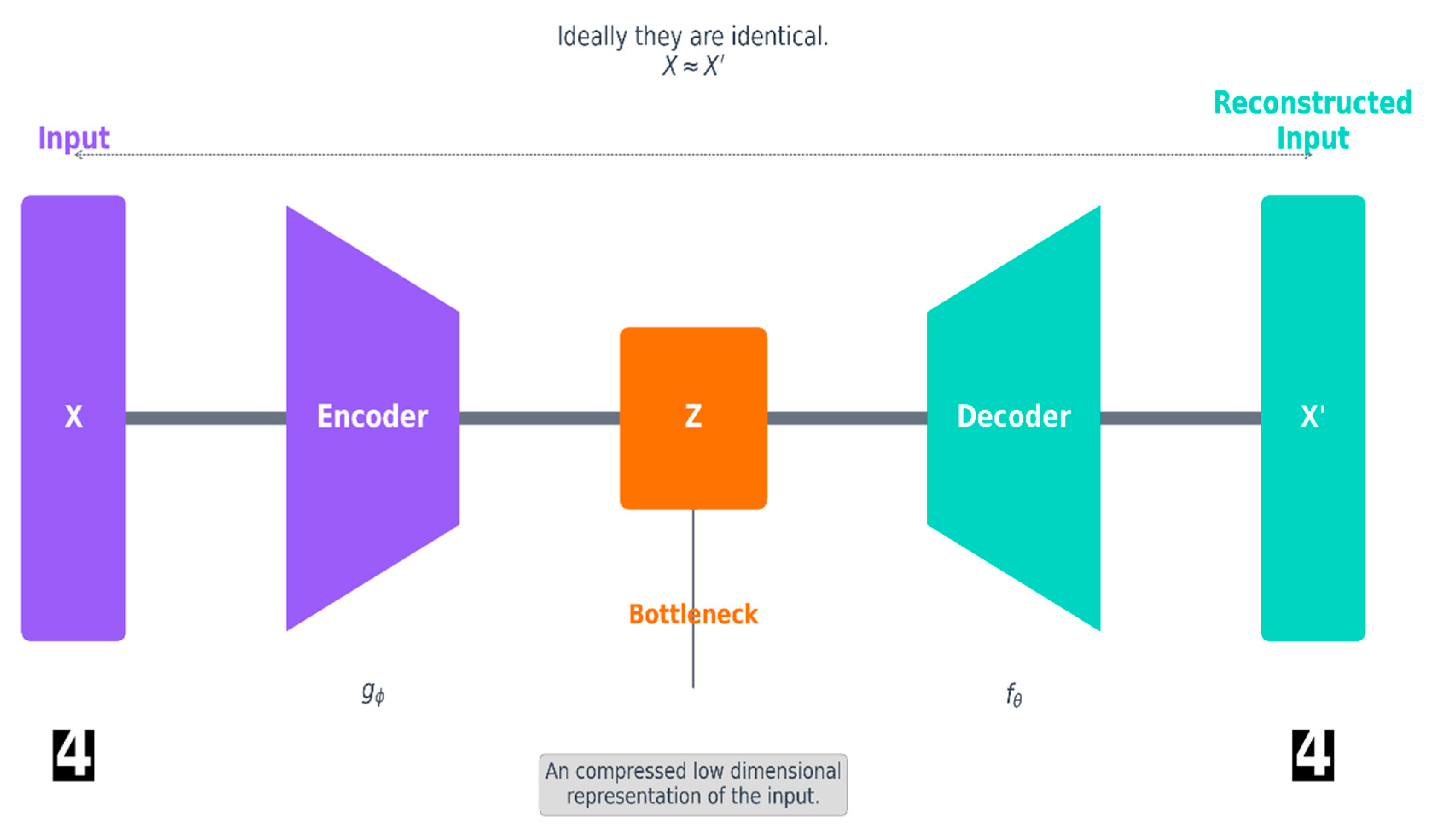

- Deep Learning Models

- (c)

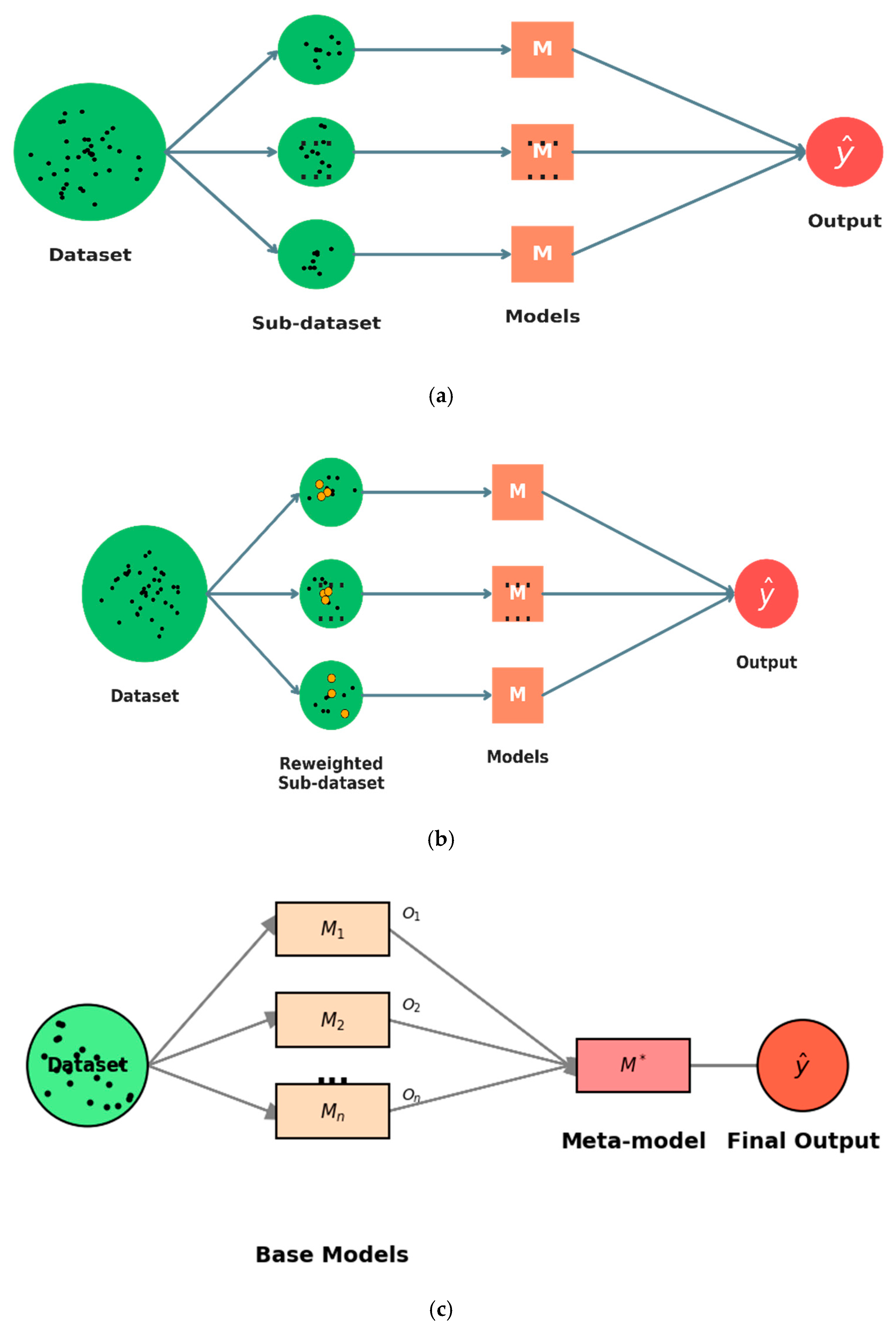

- Ensemble Models

- (d)

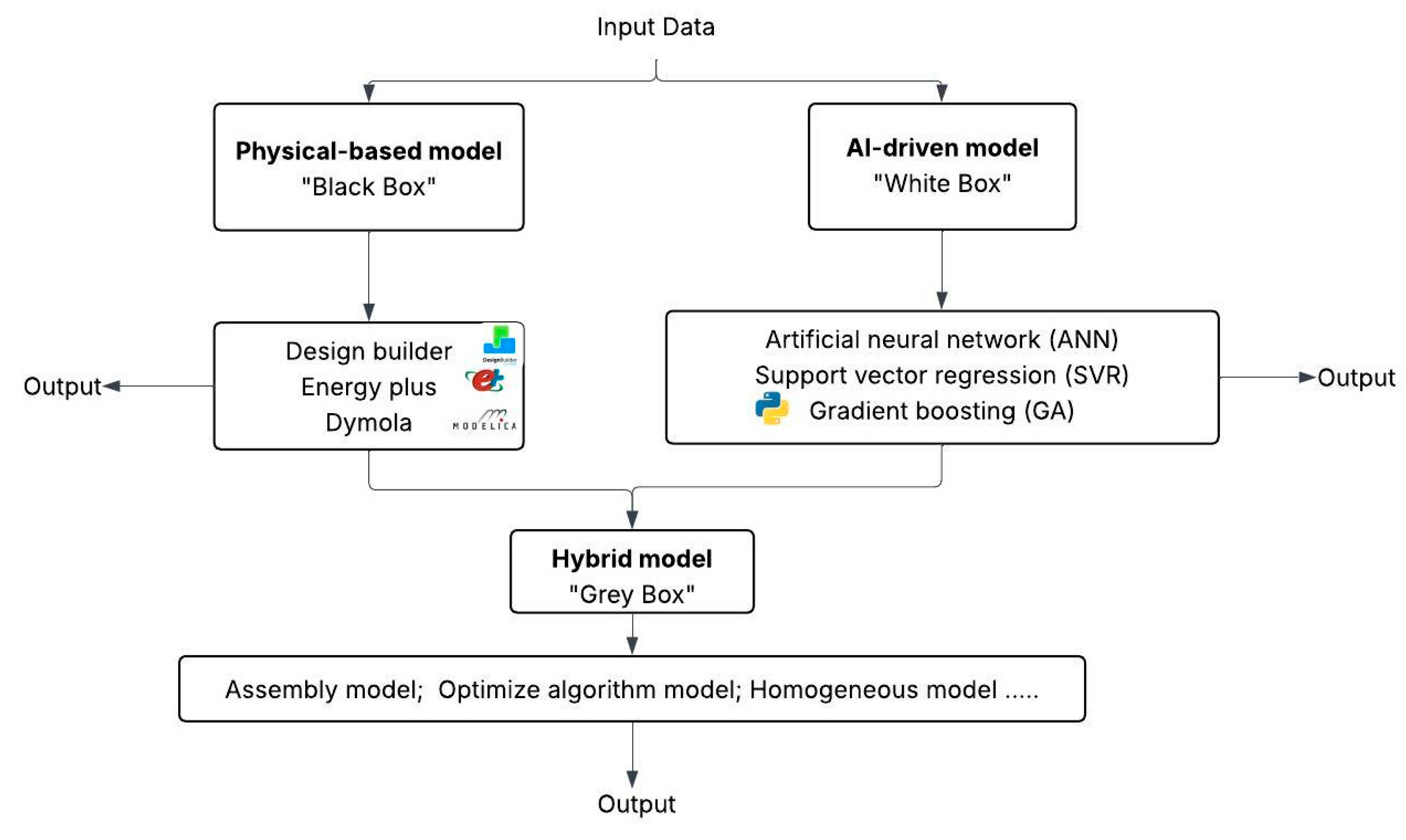

- Hybrid and Multi-Category Models

- (e)

- Frameworks for Model Integration and Collaboration

- Sequential Calibration Framework: In this architecture, a physics-based model generates an initial simulation. A data-driven model is then used to calibrate the simulation outputs against real-world measurement data, learning the residual error. The final prediction is the sum of the simulation output and the data-driven correction term. This is particularly effective for simulation calibration and post-retrofit evaluation, where the physical model provides a structurally sound baseline and the ML component fine-tunes it for a specific building.

- Surrogate-Assisted Optimization Framework: Here, a data-driven model is trained to act as a fast-to-evaluate surrogate for a computationally expensive physics-based simulation. This surrogate is then embedded within an optimization loop to rapidly explore thousands of design or control options (e.g., setpoint schedules, retrofit packages). This framework is invaluable for design-phase optimization and real-time optimal control, where directly using the simulation would be prohibitively slow.

- Physics-Informed Learning Framework: This is a tighter form of integration, where physical laws are embedded directly into the loss function or architecture of a neural network. For example, a Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) for building temperature forecasting would have been a loss function comprising both the data mismatch (compared to sensor data) and the residual of the governing heat equation. This penalizes physically implausible solutions, significantly improving generalizability and robustness, especially in data-sparse regimes.

- (f)

- Regional and Temporal Analysis of Research Focus

2.2.5. Evaluation Metrics

2.2.6. Comparative Performance Analysis

2.2.7. Quantitative Benchmarks from Contemporary Research

2.2.8. Conclusion for Energy Performance in Non-Domestic Buildings Using ML

3. Methodologies for Data Preparation

3.1. Current State of Building Energy Consumption Data

3.2. Data Preprocessing Methods

3.3. Data Fusion Methods

3.4. Transfer Learning

4. Barriers, Challenges, and Lessons Learned

4.1. Practical Implementation Barriers

4.2. Policy and Economic Barriers

5. Current Trends and Open Research Areas on Data-Driven Energy Performance Models

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Acronym | Definition |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Networks |

| AR | Auto Regression |

| BEMS | Building Energy Management System |

| BMS | Building Management System |

| CV-RMSE | Coefficient of Variation of the Root Mean Square Error |

| DEA | Data Envelopment Analysis |

| DSM | Demand Side Management |

| EEM | Energy Efficiency Measures |

| EMS | Energy Management System |

| EPBD | Energy Performance of Buildings Directive |

| ESP-r | Energy Systems Performance Research |

| EUI | Energy Use Intensity |

| FFN | Feedforward Neural Network |

| GMM | Gaussian Mixture Model |

| GP | Gaussian Process |

| GPR | Gaussian Process Regression |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| ISO | International Organisation for Standardisation |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MLR | Multivariate Regression Models |

| MRM | Multivariate Regression Models |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| RNNs | Recurrent Neural Networks |

| SVM | Support Vector Machines |

References

- Global Warming of 1.5 °C. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Opoku, E.E.O.; Boachie, M.K. The environmental impact of industrialization and foreign direct investment. Energy Policy 2020, 137, 111178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yu, S.; Sun, Y.-F. Restructuring effects of industrial and energy structures on sectoral CO2 emission peak trajectories in China. iScience 2024, 27, 110541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, V.N. Energy factors affecting environmental pollution for sustainable development goals: The case of India. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2024, 43, 410–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leherbauer, D.; Schulz, J.; Egyed, A.; Hehenberger, P. Demand-side management in less energy-intensive industries: A systematic mapping study. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 212, 115315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M.; Vasilakopoulou, K. Present and future energy consumption of buildings: Challenges and opportunities towards decarbonisation. e-Prime 2021, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Chakraborty, M. Energy Efficiency in Buildings. In Sustainable Fuel Technologies Handbook; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 457–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Li, Z. Is more use of electricity leading to less carbon emission growth? An analysis with a panel threshold model. Energy Policy 2020, 137, 111121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhr, H. The rise of the Global South and the rise in carbon emissions. Third World Q. 2021, 42, 2724–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.J.R. The Rising Threat of Atmospheric CO2: A Review on the Causes, Impacts, and Mitigation Strategies. Environments 2023, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Change: Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide|NOAA Climate.gov. Available online: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-atmospheric-carbon-dioxide (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Hansen, J.E.; Sato, M.; Simons, L.; Nazarenko, L.S.; Sangha, I.; Kharecha, P.; Zachos, J.C.; von Schuckmann, K.; Loeb, N.G.; Osman, M.B.; et al. Global warming in the pipeline. Oxf. Open Clim. Change 2023, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Torres, M.; Pérez-Lombard, L.; Coronel, J.F.; Maestre, I.R.; Yan, D. A review on buildings energy information: Trends, end-uses, fuels and drivers. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhshan, S.R.S.; Maulud, K.N.A.; Jaafar, W.S.W.M.; Karim, O.A.; Pradhan, B. Energy Consumption and Spatial Assessment of Renewable Energy Penetration and Building Energy Efficiency in Malaysia: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buildings—Energy System—IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/energy-system/buildings (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Use of Energy in Commercial Buildings—U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Available online: https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/use-of-energy/commercial-buildings.php (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Kathirgamanathan, A.; De Rosa, M.; Mangina, E.; Finn, D.P. Data-driven predictive control for unlocking building energy flexibility: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, S.; Ying, X.; Shu, J. Influencing Factors on Air Conditioning Energy Consumption of Naturally Ventilated Research Buildings Based on Actual HVAC Behaviours. Buildings 2023, 13, 2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awoyera, P.O.; Effiong, J.; Nagaraju, V.; Haque, A.; Mydin, A.O.; Onyelowe, K. Alternative construction materials: A point of view on energy reduction and indoor comfort parameters. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, R.; Jahangir, M.H. The effect of occupant distribution on energy consumption and COVID-19 infection in buildings: A case study of university building. Build. Environ. 2021, 190, 107561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayat, H.; Kashani, A. Reducing material and energy consumption in single-story buildings through 3D-printed wall designs. Energy Build. 2025, 333, 115497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, D.; Matera, N.; Cornaro, C.; Oliveti, G.; Romagnoni, P.; De Santoli, L. EnergyPlus, IDA ICE and TRNSYS predictive simulation accuracy for building thermal behaviour evaluation by using an experimental campaign in solar test boxes with and without a PCM module. Energy Build. 2020, 212, 109812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, P.; Chu, Y.; Li, W.; Wu, Y.; Ni, L.; Bao, Y.; Wang, K. Short-term electrical load forecasting using the Support Vector Regression (SVR) model to calculate the demand response baseline for office buildings. Appl. Energy 2017, 195, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yu, J.; Zhou, M.; Quan, W.; Cheng, R. Joint Forecasting Model for the Hourly Cooling Load and Fluctuation Range of a Large Public Building Based on GA-SVM and IG-SVM. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Wen, X.; Li, C.; Shao, J.; Xu, J. Predicting the energy consumption in buildings using the optimized support vector regression model. Energy 2023, 273, 127188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatasou, S.; Santamouris, M.; Geros, V. Modeling and predicting building’s energy use with artificial neural networks: Methods and results. Energy Build. 2006, 38, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, F.; Bianco, N.; Iovane, T.; Mastellone, M.; Mauro, G.M. Conceptualization, development and validation of EMAR: A user-friendly tool for accurate energy simulations of residential buildings via few numerical inputs. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 102647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Wei, H.-H.; Chi, H.L.; Ni, M. Influence of Occupant Behavior for Building Energy Conservation: A Systematic Review Study of Diverse Modeling and Simulation Approach. Buildings 2021, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfren, M.; Aste, N.; Moshksar, R. Calibration and uncertainty analysis for computer models—A meta-model based approach for integrated building energy simulation. Appl. Energy 2013, 103, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexakis, K.; Benekis, V.; Kokkinakos, P.; Askounis, D. Genetic algorithm-based multi-objective optimisation for energy-efficient building retrofitting: A systematic review. Energy Build. 2025, 328, 115216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owolabi, A.B.; Yahaya, A.; Li, H.X.; Suh, D. Analysis of the Energy Performance of a Retrofitted Low-Rise Residential Building after an Energy Audit. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillone, B.; Danov, S.; Sumper, A.; Cipriano, J.; Mor, G. A review of deterministic and data-driven methods to quantify energy efficiency savings and to predict retrofitting scenarios in buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 131, 110027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thravalou, S.; Michopoulos, A.; Alexandrou, K.; Artopoulos, G. Energy retrofit strategies of built heritage: Using Building Information Modelling tools for streamlined energy and economic analysis. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1196, 012115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlander, J.; Thollander, P. Barriers to implementation of energy-efficient technologies in building construction projects—Results from a Swedish case study. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 11, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardar, A.; Islam, R.; Anantharaman, M.; Garaniya, V. Advancements and obstacles in improving the energy efficiency of maritime vessels: A systematic review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 214, 117688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, F.; Lindberg, O.; Ramadhani, U.; Shadram, F.; Munkhammar, J.; Widén, J. Analysis of large-scale energy retrofit of residential buildings and their impact on the electricity grid using a validated UBEM. Appl. Energy 2024, 361, 122937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuominen, P.; Reda, F.; Dawoud, W.; Elboshy, B.; Elshafei, G.; Negm, A. Economic appraisal of energy efficiency in buildings using cost-effectiveness assessment. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 21, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, T.; Pató, Z. Towards effective implementation of the energy efficiency first principle: A theory-based classification and analysis of policy instruments. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 115, 103613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiks, E.R.; Stenner, K.; Hobman, E.V.; Fischle, M. Evaluating energy behavior change programs using randomized controlled trials: Best practice guidelines for policymakers. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 22, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labaran, Y.H.; Mathur, V.S.; Muhammad, S.U.; Musa, A.A. Carbon footprint management: A review of construction industry. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2022, 9, 100531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zhang, L. A bi-objective optimization of energy consumption and investment cost for public building envelope design based on the ε-constraint method. Energy Build. 2022, 266, 112133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.; Yan, G.; Abed, A.M.; Elattar, S.; Khadimallah, M.A.; Jan, A.; Ali, H.E. The effect of carbon dioxide emissions on the building energy efficiency. Fuel 2022, 326, 124842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adom, P.K. An evaluation of energy efficiency performances in Africa under heterogeneous technologies. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 1170–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachega, M.A.; Yao, X.; Liu, Y.; Ahmed, D.; Li, H.; Mintah, C. Energy efficiency evaluation of oil producing economies in Africa: DEA, malmquist and multiple regression approaches. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2021, 2, 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agradi, M.; Adom, P.K.; Vezzulli, A. Towards sustainability: Does energy efficiency reduce unemployment in African societies? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 79, 103683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gava, E.; Seabela, M.; Ogujiuba, K. Energy Efficiency, Consumption, and Economic Growth: A Causal Analysis in the South African Economy. Economies 2025, 13, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- African Union Summit Adopts Bold Strategies for Clean and Sustainable Energy and Transport Pathways|African Union. Available online: https://au.int/en/pressreleases/20250219/african-union-summit-adopts-bold-strategies-clean-and-sustainable-energy-and (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Zambia Energy Efficiency Strategy and Action Plan—Ministry of Energy Integrated Resource Plan. Available online: https://www.moe.gov.zm/irp/?wpdmpro=zambia-energy-efficiency-strategy-and-action-plan-rar (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Oyejobi, D.; Firoozi, A.A. Innovations in energy-efficient construction: Pioneering sustainable building practices. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2025, 26, 100957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Wu, J.; Zhao, J.; Nogueira, M.; Lloret, J. Green buildings: Requirements, features, life cycle, and relevant intelligent technologies. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2024, 4, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhu, M.; Lv, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Yin, R.; Yang, Y.; Jia, X.; Wang, X.; Zeng, F.; et al. Building energy simulation and its application for building performance optimization: A review of methods, tools, and case studies. Adv. Appl. Energy 2023, 10, 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, C.; Schlueter, A. Review of data-driven energy modelling techniques for building retrofit. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 144, 110990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgstein, E.; Lamberts, R.; Hensen, J. Evaluating energy performance in non-domestic buildings: A review. Energy Build. 2016, 128, 734–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Haghighat, F.; Fung, B.C. A review of the-state-of-the-art in data-driven approaches for building energy prediction. Energy Build. 2020, 221, 110022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himeur, Y.; Elnour, M.; Fadli, F.; Meskin, N.; Petri, I.; Rezgui, Y.; Bensaali, F.; Amira, A. AI-big data analytics for building automation and management systems: A survey, actual challenges and future perspectives. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 4929–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Li, P.; Wang, F.; Osmani, M.; Demian, P. Building Information Modeling (BIM) Driven Carbon Emission Reduction Research: A 14-Year Bibliometric Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.P.; Bragança, L.; Mateus, R. BIM-Based Sustainability Assessment: Insights for Building Circularity. In Creating a Roadmap Towards Circularity in the Built Environment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume Part F1844, pp. 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarczyk, M. Building energy characteristic evaluation in terms of energy efficiency and ecology. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 306, 118284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, M.; Babar, M.A.; Chauhan, M.A. Architectural Design Space for Modelling and Simulation as a Service: A Review. J. Syst. Softw. 2020, 170, 110752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, E.; O’BRien, W.; Carlucci, S.; Hong, T.; Sonta, A.; Kim, J.; Andargie, M.S.; Abuimara, T.; El Asmar, M.; Jain, R.K.; et al. Simulation-aided occupant-centric building design: A critical review of tools, methods, and applications. Energy Build. 2020, 224, 110292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natividade, J.; Cruz, C.O.; Silva, C.M. Improving the Efficiency of Energy Consumption in Buildings: Simulation of Alternative EnPC Models. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degerfeld, F.B.M.; Piro, M.; De Luca, G.; Ballarini, I.; Corrado, V. The application of EN ISO 52016-1 to assess building cost-optimal energy performance levels in Italy. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 1702–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thebuwena, A.C.H.J.; Samarakoon, S.M.S.M.K.; Ratnayake, R.M.C. Optimization of energy consumption in vertical mobility systems of high-rise office buildings: A case study from a developing economy. Energy Effic. 2024, 17, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaisar, I.; Zhao, Q. Energy baseline prediction for buildings: A review. Results Control Optim. 2022, 7, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wang, B.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, H. Benchmarking Evaluation of Building Energy Consumption Based on Data Mining. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahee, A.; Abdoos, M.; Aslani, A.; Zahedi, R. Reducing the energy consumption of buildings by implementing insulation scenarios and using renewable energies. Energy Inform. 2024, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, D.; McCallum, P.; Patidar, S.; Semple, S. Accommodating new calculation approaches in next-generation energy performance assessments. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2024, 17, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Fennell, P.; Korolija, I.; Fang, Z.; Tang, R.; Ruyssevelt, P. Review of non-domestic building stock modelling studies under socio-technical system framework. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, O.; Fakhoury, S.; Aldalou, G.; Almasri, G. Energy Auditing and Conservation for Educational Buildings: A Case Study on Princess Sumaya University for Technology. Process Integr. Optim. Sustain. 2022, 6, 901–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.P. Sustainability Performance Simulation Tools for Building Design. In Sustainable Built Environments; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 589–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, G.; Johra, H.; Georges, L.; Austbø, B. Synconn_build: A python based synthetic dataset generator for testing and validating control-oriented neural networks for building dynamics prediction. MethodsX 2023, 11, 102464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, J.; Soper, J.; Jones, P.; Bordass, W.; Grigg, P. Energy performance of occupied non-domestic buildings: Assessment by analysing end-use energy consumptions. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 1997, 18, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EnergyPlus Simulation Software. Available online: https://energyplus.net (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- DOE2.com Home Page. Available online: https://www.doe2.com/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- ESP-r|University of Strathclyde. Available online: https://www.strath.ac.uk/research/energysystemsresearchunit/applications/esp-r/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Bjørnskov, J.; Jradi, M.; Wetter, M. Automated model generation and parameter estimation of building energy models using an ontology-based framework. Energy Build. 2025, 329, 115228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobha, G.; Rangaswamy, S. Machine Learning. In Handbook of Statistics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 38, pp. 197–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjøstheim, D.; Otneim, H.; Støve, B. Time Series Dependence and Spectral Analysis. In Statistical Modeling Using Local Gaussian Approximation; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 261–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaee, T.; Khani, S.; Ravansalar, M. Artificial intelligence-based single and hybrid models for prediction of water quality in rivers: A review. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2020, 200, 103978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Kim, Y.-S.; Srebric, J. Predictions of electricity consumption in a campus building using occupant rates and weather elements with sensitivity analysis: Artificial neural network vs. linear regression. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 62, 102385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscitelli, M.S.; Giudice, R.; Capozzoli, A. A holistic time series-based energy benchmarking framework for applications in large stocks of buildings. Appl. Energy 2024, 357, 122550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home|ashrae.org. Available online: https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/bookstore/standards-15-34 (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Milić, V.; Rohdin, P.; Moshfegh, B. Further development of the change-point model—Differentiating thermal power characteristics for a residential district in a cold climate. Energy Build. 2020, 231, 110639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.; Yeung, I.M. Benchmarking by convex non-parametric least squares with application on the energy performance of office buildings. Appl. Energy 2017, 203, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delnava, H.; Khosravi, A.; Assad, M.E.H. Metafrontier frameworks for estimating solar power efficiency in the United States using stochastic nonparametric envelopment of data (StoNED). Renew. Energy 2023, 213, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyuncuoğlu, M.U.; Yeşilyurt, M.E.; Akbaş-Yeşilyurt, F.; Şahin, E.; Elbi, M.D. A New Approach to Efficiency Measurement: Hybrid JAYA Algorithm and Data Envelopment Analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 268, 126342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabmaldar, A.; Sahoo, B.K.; Ghiyasi, M. A generalized robust data envelopment analysis model based on directional distance function. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 311, 617–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favero, M.; Luparelli, A.; Carlucci, S. Analysis of subjective thermal comfort data: A statistical point of view. Energy Build. 2023, 281, 112755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, W.; Qin, C.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Tu, J. Evaluation of supervised machine learning regression models for CFD-based surrogate modelling in indoor airflow field reconstruction. Build. Environ. 2024, 267, 112173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.-L.; Jiang, B.; Lu, J.; Hua, J.; Swamy, M.N.S. Exploring Kernel Machines and Support Vector Machines: Principles, Techniques, and Future Directions. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amasyali, K.; El-Gohary, N. Building Lighting Energy Consumption Prediction for Supporting Energy Data Analytics. Procedia Eng. 2016, 145, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrablecová, P.; Ezzeddine, A.B.; Rozinajová, V.; Šárik, S.; Sangaiah, A.K. Smart grid load forecasting using online support vector regression. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2018, 65, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, A.; Al Zohbi, G.; Salau, A.O.; Maitra, S.K. Prediction of building cooling load: An innovative design for GA-SVM and IG-SVM system for the estimation of hourly precision and computational fluctuation range. Adv. Build. Energy Res. 2024, 18, 668–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massana, J.; Pous, C.; Burgas, L.; Melendez, J.; Colomer, J. Short-term load forecasting in a non-residential building contrasting models and attributes. Energy Build. 2015, 92, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabunko, V.; Lim, C.; Brahim, S.; Mathew, S. Developing building benchmarking for Brunei Darussalam. Energy Build. 2014, 85, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Cai, X.; Dai, L. Prediction of building HVAC energy consumption based on least squares support vector machines. Energy Inform. 2024, 7, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradzadeh, A.; Mansour-Saatloo, A.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A. Performance Evaluation of Two Machine Learning Techniques in Heating and Cooling Loads Forecasting of Residential Buildings. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, G.L.; Patle, A. on performing classification using svm with radial basis and polynomial kernel functions. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Emerging Trends in Engineering and Technology, ICETET 2010, Washington, DC, USA, 19–21 November 2010; pp. 512–515. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, R.K.; Smith, K.M.; Culligan, P.J.; Taylor, J.E. Forecasting energy consumption of multi-family residential buildings using support vector regression: Investigating the impact of temporal and spatial monitoring granularity on performance accuracy. Appl. Energy 2014, 123, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.E.; New, J.; Parker, L.E. Predicting future hourly residential electrical consumption: A machine learning case study. Energy Build. 2012, 49, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.; Chen, Y.; Han, C.; Duan, Z. Research on the Decision-Making Method for the Passive Design Parameters of Zero Energy Houses in Severe Cold Regions Based on Decision Trees. Energies 2024, 17, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Yang, C.; Wang, Z. Prediction of building energy consumption for public structures utilizing BIM-DB and RF-LSTM. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 4631–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, R.; Srinivasan, R.S.; Ahrentzen, S. Random Forest based hourly building energy prediction. Energy Build. 2018, 171, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahouar, A.; Slama, J.B.H. Day-ahead load forecast using random forest and expert input selection. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 103, 1040–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hong, T.; Piette, M.A. Building thermal load prediction through shallow machine learning and deep learning. Appl. Energy 2020, 263, 114683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Cheng, F.; Ma, X.; Hu, G. Short-term prediction of building energy consumption employing an improved extreme gradient boosting model: A case study of an intake tower. Energy 2020, 203, 117756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Dong, H.; Zheng, W.; Li, S.; Huang, Y.; Xi, L. Review and prospect of data-driven techniques for load forecasting in integrated energy systems. Appl. Energy 2022, 321, 119269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulloch-Pitts Neuron—Mankind’s First Mathematical Model of a Biological Neuron|by Akshay L Chandra|TDS Archive|Medium. Available online: https://medium.com/data-science/mcculloch-pitts-model-5fdf65ac5dd1 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Rosenblatt’s Perceptron, the First Modern Neural Network|by Jean-Christophe B. Loiseau|TDS Archive|Medium. Available online: https://medium.com/data-science/rosenblatts-perceptron-the-very-first-neural-network-37a3ec09038a (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- El Alaoui, M.; Rougui, M. Examining the Application of Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) for Advancing Energy Efficiency in Building: A Comprehensive Reviews. J. Sustain. Res. 2024, 6, e240001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, R.; Rodríguez, F.; Castilla, M.; Arahal, M. A prediction model based on neural networks for the energy consumption of a bioclimatic building. Energy Build. 2014, 82, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalakakou, G.; Santamouris, M.; Tsangrassoulis, A. On the energy consumption in residential buildings. Energy Build. 2002, 34, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, P.A.; Zamarreño, J.M. Prediction of hourly energy consumption in buildings based on a feedback artificial neural network. Energy Build. 2005, 37, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Hu, C.; Liu, G.; Xue, W. Building’s electricity consumption prediction using optimized artificial neural networks and principal component analysis. Energy Build. 2015, 108, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platon, R.; Dehkordi, V.R.; Martel, J. Hourly prediction of a building’s electricity consumption using case-based reasoning, artificial neural networks and principal component analysis. Energy Build. 2015, 92, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-M.; Paterson, G.; Mumovic, D.; Steadman, P. Improved benchmarking comparability for energy consumption in schools. Build. Res. Inf. 2014, 42, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Wan, K.K.; Lam, T.N. Artificial neural networks for energy analysis of office buildings with daylighting. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, M.; Andersson, S.; Östin, R. Development and validation of a method aimed at estimating building performance parameters. Energy Build. 2004, 36, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayatian, F.; Sarto, L.; Dall’o’, G. Application of neural networks for evaluating energy performance certificates of residential buildings. Energy Build. 2016, 125, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, F.; Bianco, N.; De Stasio, C.; Mauro, G.M.; Vanoli, G.P. Artificial neural networks to predict energy performance and retrofit scenarios for any member of a building category: A novel approach. Energy 2017, 118, 999–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombaycı, Ö.A. The prediction of heating energy consumption in a model house by using artificial neural networks in Denizli–Turkey. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2010, 41, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kialashaki, A.; Reisel, J.R. Modeling of the energy demand of the residential sector in the United States using regression models and artificial neural networks. Appl. Energy 2013, 108, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antanasijević, D.; Pocajt, V.; Ristić, M.; Perić-Grujić, A. Modeling of energy consumption and related GHG (greenhouse gas) intensity and emissions in Europe using general regression neural networks. Energy 2015, 84, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.H.; Fiorelli, F.A.S. Comparison between detailed model simulation and artificial neural network for forecasting building energy consumption. Energy Build. 2008, 40, 2169–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, D.; Ungureanu, F.; Hernández-Guerrero, A. Simulation models for the analysis of space heat consumption of buildings. Energy 2009, 34, 1447–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, C.; Eang, L.S.; Yang, J.; Santamouris, M. Forecasting diurnal cooling energy load for institutional buildings using Artificial Neural Networks. Energy Build. 2016, 121, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, T.; Andersson, S. Long-term energy demand predictions based on short-term measured data. Energy Build. 2001, 33, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekici, B.B.; Aksoy, U.T. Prediction of building energy consumption by using artificial neural networks. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2009, 40, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, S.; Elmtiri, M.; Kling, W.L.; Le Corre, O.; Lacarrière, B. Pseudo dynamic transitional modeling of building heating energy demand using artificial neural network. Energy Build. 2014, 70, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Nakhi, A.E.; Mahmoud, M.A. Cooling load prediction for buildings using general regression neural networks. Energy Convers. Manag. 2004, 45, 2127–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Lian, Z.; Yao, Y.; Yuan, X. Cooling-load prediction by the combination of rough set theory and an artificial neural-network based on data-fusion technique. Appl. Energy 2006, 83, 1033–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng-Wen, Y.; Jian, Y. Application of ANN for the prediction of building energy consumption at different climate zones with HDD and CDD. In Proceedings of the 2010 2nd International Conference on Future Computer and Communication, ICFCC 2010, Wuhan, China, 21–24 May 2010; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, M.R.; Robinson, M.D.; Fumo, N. Prediction of residential building energy consumption: A neural network approach. Energy 2016, 117, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydinalp, M.; Ugursal, V.I.; Fung, A.S. Modeling of the appliance, lighting, and space-cooling energy consumptions in the residential sector using neural networks. Appl. Energy 2002, 71, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, R.; Nishant, R.; Emrouznejad, A. Modeling Residential Energy Consumption. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 166–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadeh, A.; Ghaderi, S.; Sohrabkhani, S. Annual electricity consumption forecasting by neural network in high energy consuming industrial sectors. Energy Convers. Manag. 2008, 49, 2272–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kialashaki, A.; Reisel, J.R. Development and validation of artificial neural network models of the energy demand in the industrial sector of the United States. Energy 2014, 76, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoqian, J.; Bing, D.; Le, X.; Latanya, S. Adaptive gaussian process for short-term wind speed forecasting. Front. Artif. Intell. Appl. 2010, 215, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosicki, E.; Abed-Meraim, K.; Hua, Y. A weighted linear prediction method for near-field source localization. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2005, 53, 3651–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Sa-Ngasoongsong, A.; Beyca, O.; Le, T.; Yang, H.; Kong, Z.; Bukkapatnam, S.T. Time series forecasting for nonlinear and non-stationary processes: A review and comparative study. IIE Trans. 2015, 47, 1053–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, Y.; Choudhary, R.; Augenbroe, G. Calibration of building energy models for retrofit analysis under uncertainty. Energy Build. 2012, 47, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, Y.; Zavala, V.M. Gaussian process modeling for measurement and verification of building energy savings. Energy Build. 2012, 53, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; O’neill, Z.; Wagner, T.; Augenbroe, G. An Inverse Model with Uncertainty Quantification to Estimate the Energy Performance of an Office Building. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286062289_An_inverse_model_with_uncertainty_quantification_to_estimate_the_energy_performance_of_an_office_building (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Noh, H.Y.; Rajagopal, R. Data-driven forecasting algorithms for building energy consumption. SPIE 2013, 8692, 86920T. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, P.; Khan, M.E.; Andersen, M. Gaussian-Process-Based Emulators for Building Performance Simulation. In Proceedings of the 15th IBPSA Conference 2017, San Francisco, CA, USA, 7–9 August 2017; pp. 1701–1709. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart, M.C.; Heo, Y.; Zavala, V.M. Measurement and verification of building systems under uncertain data: A Gaussian process modeling approach. Energy Build. 2014, 75, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastav, A.; Tewari, A.; Dong, B. Baseline building energy modeling and localized uncertainty quantification using Gaussian mixture models. Energy Build. 2013, 65, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; O’NEill, Z.; Dong, B.; Augenbroe, G. Comparisons of inverse modeling approaches for predicting building energy performance. Build. Environ. 2015, 86, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Malkawi, A. A new methodology for building energy performance benchmarking: An approach based on intelligent clustering algorithm. Energy Build. 2014, 84, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M.; Mihalakakou, G.; Patargias, P.; Gaitani, N.; Sfakianaki, K.; Papaglastra, M.; Pavlou, C.; Doukas, P.; Primikiri, E.; Geros, V.; et al. Using intelligent clustering techniques to classify the energy performance of school buildings. Energy Build. 2007, 39, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitani, N.; Lehmann, C.; Santamouris, M.; Mihalakakou, G.; Patargias, P. Using principal component and cluster analysis in the heating evaluation of the school building sector. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 2079–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieri, S.P.; Tzouvadakis, I.; Santamouris, M. Identifying energy consumption patterns in the Attica hotel sector using cluster analysis techniques with the aim of reducing hotels’ CO2 footprint. Energy Build. 2015, 94, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petcharat, S.; Chungpaibulpatana, S.; Rakkwamsuk, P. Assessment of potential energy saving using cluster analysis: A case study of lighting systems in buildings. Energy Build. 2012, 52, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ning, C.; Deb, C.; Zhang, F.; Cheong, D.; Lee, S.E.; Sekhar, C.; Tham, K.W. k-Shape clustering algorithm for building energy usage patterns analysis and forecasting model accuracy improvement. Energy Build. 2017, 146, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y. Learning deep architectures for AI. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 2009, 2, 1–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teso-Fz-Betoño, A.; Zulueta, E.; Cabezas-Olivenza, M.; Teso-Fz-Betoño, D.; Fernandez-Gamiz, U. A Study of Learning Issues in Feedforward Neural Networks. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 1–23. Available online: https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262035613/deep-learning/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Humaidi, A.J.; Al-Dujaili, A.; Duan, Y.; Al-Shamma, O.; Santamaría, J.; Fadhel, M.A.; Al-Amidie, M.; Farhan, L. Review of deep learning: Concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hong, T.; Piette, M.A. Data fusion in predicting internal heat gains for office buildings through a deep learning approach. Appl. Energy 2019, 240, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaei, H.J.; Silva, P.C.d.L.e.; Guimarães, F.G.; Lee, M.H. Short-term load forecasting by using a combined method of convolutional neural networks and fuzzy time series. Energy 2019, 175, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mienye, I.D.; Swart, T.G.; Obaido, G. Recurrent Neural Networks: A Comprehensive Review of Architectures, Variants, and Applications. Information 2024, 15, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, C.; Lauret, P.; Bastide, A. Machine Learning to speed up Computational Fluid Dynamics engineering simulations for built environments: A review. Build. Environ. 2025, 267, 112229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Song, M.; Wang, J. Deep learning-based feature engineering methods for improved building energy prediction. Appl. Energy 2019, 240, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Srikumar, V.; Smith, A.D. Predicting electricity consumption for commercial and residential buildings using deep recurrent neural networks. Appl. Energy 2018, 212, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Fang, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.; Ding, Y.; Jiang, X.; Ji, Y. Using long short-term memory networks to predict energy consumption of air-conditioning systems. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 55, 102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Moon, J.; Hwang, E.; Kang, P. Recurrent inception convolution neural network for multi short-term load forecasting. Energy Build. 2019, 194, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjeev Kumar, T.M.; Kurian, C.P.; Varghese, S.G. Ensemble Learning Model-Based Test Workbench for the Optimization of Building Energy Performance and Occupant Comfort. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 96075–96087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Srinivasan, R.S. A novel ensemble learning approach to support building energy use prediction. Energy Build. 2018, 159, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.; Dilkina, B.; Hubbs, J.; Zhang, W.; Guhathakurta, S.; Brown, M.A.; Pendyala, R.M. Machine learning approaches for estimating commercial building energy consumption. Appl. Energy 2017, 208, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, J.; Spanier, D.; Panten, N.; Abele, E. Very short-term load forecasting on factory level—A machine learning approach. Procedia CIRP 2019, 80, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, J.; Deng, N.; Zhou, Z.; Gao, F. Multi-criteria comprehensive study on predictive algorithm of heating energy consumption of district heating station based on timeseries processing. Energy 2020, 202, 117714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Guo, Y.; Ahmad, T. A novel energy demand prediction strategy for residential buildings based on ensemble learning. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 3411–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsanas, A.; Xifara, A. Accurate quantitative estimation of energy performance of residential buildings using statistical machine learning tools. Energy Build. 2012, 49, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, S.; Azar, E.; Woon, W.-L.; Kontokosta, C.E. Evaluation of tree-based ensemble learning algorithms for building energy performance estimation. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2018, 11, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Fannon, D.; Eckelman, M.J. Predictive modeling for US commercial building energy use: A comparison of existing statistical and machine learning algorithms using CBECS microdata. Energy Build. 2018, 163, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Han, Y.; Xu, P. Methods for benchmarking building energy consumption against its past or intended performance: An overview. Appl. Energy 2014, 124, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barja-Martinez, S.; Aragüés-Peñalba, M.; Munné-Collado, Í.; Lloret-Gallego, P.; Bullich-Massagué, E.; Villafafila-Robles, R. Artificial intelligence techniques for enabling Big Data services in distribution networks: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 150, 111459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadi, M.R.; Mirshekali, H.; Shaker, H.R. Explainable artificial intelligence for energy systems maintenance: A review on concepts, current techniques, challenges, and prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 216, 115668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, Y.; Sri Preethaa, K.R.; Wadhwa, G.; Choi, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lee, D.-E.; Mi, Y. Enhancing Building Energy Efficiency with IoT-Driven Hybrid Deep Learning Models for Accurate Energy Consumption Prediction. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daki, H.; Saad, B.; El Hannani, A.; Haidine, A.; Ouahmane, H. Forecasting Energy Consumption in Educational Buildings with Big Data Analytics. In ICT for Smart Grid-Recent Advances, New Perspectives, and Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Li, Z.; Rahman, S.M.; Vega, R. A hybrid model approach for forecasting future residential electricity consumption. Energy Build. 2016, 117, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardioli, G.; Kerrigan, R.; Oates, M.; O’dOnnell, J.; Finn, D. Data Driven Approaches for Prediction of Building Energy Consumption at Urban Level. Energy Procedia 2015, 78, 3378–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweidtmann, A.M.; Zhang, D.; von Stosch, M. A review and perspective on hybrid modeling methodologies. Digit. Chem. Eng. 2024, 10, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althaus, P.; Redder, F.; Ubachukwu, E.; Mork, M.; Xhonneux, A.; Müller, D. Enhancing Building Monitoring and Control for District Energy Systems: Technology Selection and Installation within the Living Lab Energy Campus. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Guo, M.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Z.; Ji, Y. Physical energy and data-driven models in building energy prediction: A review. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 2656–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnuwaiser, M.A.; Javed, M.F.; Khan, M.I.; Ahmed, M.W.; Galal, A.M. Support vector regression and ANN approach for predicting the ground water quality. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2022, 99, 100538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghattas, B.; Manzon, D. Machine Learning Alternatives to Response Surface Models. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I.H. AI-Based Modeling: Techniques, Applications and Research Issues Towards Automation, Intelligent and Smart Systems. SN Comput. Sci. 2022, 3, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, I.U.; Kumar, A.; Rathore, P.S. Machine learning approaches for wind power forecasting: A comprehensive review. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, S.M. Physics-informed machine learning meets renewable energy systems: A review of advances, challenges, guidelines, and future outlooks. Appl. Energy 2025, 402, 126925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Zayed, T.; Lafhaj, Z. Enhancing Construction Performance: A Critical Review of Performance Measurement Practices at the Project Level. Buildings 2024, 14, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutahri, Y.; Tilioua, A. Machine learning-based predictive model for thermal comfort and energy optimization in smart buildings. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T. Chapter 4—Prediction of photovoltaic power generation output and network operation. In Integration of Distributed Energy Resources in Power Systems; Funabashi, T., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 77–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosamo, H.; Hosamo, M.H.; Nielsen, H.K.; Svennevig, P.R.; Svidt, K. Digital Twin of HVAC system (HVACDT) for multiobjective optimization of energy consumption and thermal comfort based on BIM framework with ANN-MOGA. Adv. Build. Energy Res. 2023, 17, 125–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satan, A.; Zhakiyev, N.; Nugumanova, A.; Friedrich, D. Hybrid feature-based neural network regression method for load profiles forecasting. Energy Inform. 2025, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golafshani, E.; Chiniforush, A.A.; Zandifaez, P.; Ngo, T. An artificial intelligence framework for predicting operational energy consumption in office buildings. Energy Build. 2024, 317, 114409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, R.; Rague, B. Machine Learning. In The Beginner’s Guide to Data Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 155–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’AMico, A.; Ciulla, G.; Traverso, M.; Brano, V.L.; Palumbo, E. Artificial Neural Networks to assess energy and environmental performance of buildings: An Italian case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 239, 117993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, B.; Deb, S.; Datta, S.; Ustun, T.S.; Cali, U. Review on smart grid load forecasting for smart energy management using machine learning and deep learning techniques. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 3654–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.; Khan, W.; Katic, K.; Maassen, W.; Zeiler, W. Accuracy of different machine learning algorithms and added-value of predicting aggregated-level energy performance of commercial buildings. Energy Build. 2020, 209, 109705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazemi, T.; Darwish, M.; Radi, M. Renewable energy sources integration via machine learning modelling: A systematic literature review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Xia, Y.; Yan, Z.; Gao, H.; Qiu, D.; Guerrero, J.M.; Li, Z. Coordinated operation of multi-energy microgrids considering green hydrogen and congestion management via a safe policy learning approach. Appl. Energy 2025, 401, 109705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, K.; Aref, M.; Almalki, M.M.; Mossa, M.A. Optimizing fast charging protocols for lithium-ion batteries using reinforcement learning: Balancing speed, efficiency, and longevity. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalo, F.D.A.; Santamaría, B.M.; Burgos, M.J.M. Assessment of Building Energy Simulation Tools to Predict Heating and Cooling Energy Consumption at Early Design Stages. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GitHub—wwzjustin/CER-Smart-Meter-Project-by-Irish-Social-Science-Data-Archive.: CER Smart Meter Project by Irish Social Science Data Archive. Available online: https://github.com/wwzjustin/CER-Smart-Meter-Project-by-Irish-Social-Science-Data-Archive (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Part of Energy Data Set (REDD). Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/pawelkauf/redd-part (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Energy Information Administration (EIA)-Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey (CBECS). Available online: https://www.eia.gov/consumption/commercial/ (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Hong, T.; Pinson, P.; Fan, S. Global energy forecasting competition 2012. Int. J. Forecast. 2014, 30, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Pinson, P.; Fan, S.; Zareipour, H.; Troccoli, A.; Hyndman, R.J. Probabilistic energy forecasting: Global Energy Forecasting Competition 2014 and beyond. Int. J. Forecast. 2016, 32, 896–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Xie, J.; Black, J. Global energy forecasting competition 2017: Hierarchical probabilistic load forecasting. Int. J. Forecast. 2019, 35, 1389–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Building Performance Database|Building Technology and Urban Systems. Available online: https://buildings.lbl.gov/cbs/bpd (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Miller, C.; Meggers, F. The Building Data Genome Project: An open, public data set from non-residential building electrical meters. Energy Procedia 2017, 122, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.; Kathirgamanathan, A.; Picchetti, B.; Arjunan, P.; Park, J.Y.; Nagy, Z.; Raftery, P.; Hobson, B.W.; Shi, Z.; Meggers, F. The Building Data Genome Project 2, energy meter data from the ASHRAE Great Energy Predictor III competition. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Chen, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Huang, B. A Review on Data Preprocessing Techniques Toward Efficient and Reliable Knowledge Discovery from Building Operational Data. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 652801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wu, H. A Review of Data-Driven Building Energy Prediction. Buildings 2023, 13, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantuano, C.; Omoyele, O.; Hoffmann, M.; Weinand, J.M.; Panella, M.; Stolten, D. Data imputation methods for intermittent renewable energy sources: Implications for energy system modeling. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 339, 119857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-Y.; Cho, S.-B. Predicting residential energy consumption using CNN-LSTM neural networks. Energy 2019, 182, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; de Wilde, P.; Attia, S.; Zuo, J. Challenges in predicting the impact of climate change on thermal building performance through simulation: A systematic review. Appl. Energy 2025, 382, 125331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuemei, L.; Lixing, D.; Jinhu, L.; Gang, X.; Jibin, L. A Novel Hybrid Approach of KPCA and SVM for Building Cooling Load Prediction. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, WKDD 2010, Phuket, Thailand, 9–10 January 2010; pp. 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Song, J.; Shi, D.; Reyna, J.L.; Horsey, H.; Feron, S.; Zhou, Y.; Ouyang, Z.; Li, Y.; Jackson, R.B. Impacts of climate change, population growth, and power sector decarbonization on urban building energy use. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulou, E.; Zafeiropoulos, A.; Terroso-Sáenz, F.; Şimşek, U.; González-Vidal, A.; Tsiolis, G.; Gouvas, P.; Liapis, P.; Fensel, A.; Skarmeta, A. Providing Personalized Energy Management and Awareness Services for Energy Efficiency in Smart Buildings. Sensors 2017, 17, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, Y.; Arbabi, H.; Ward, W.O.; Mayfield, M. Learning from other cities: Transfer learning based multimodal residential energy prediction for cities with limited existing data. Energy Build. 2025, 338, 115723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Ma, S.; Hao, J.; Han, D.; Huang, D.; Yan, S.; Li, T. An electricity load forecasting model for Integrated Energy System based on BiGAN and transfer learning. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 3446–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Gong, G.; Li, G.; Chun, L.; Li, W.; Peng, P. A hybrid deep transfer learning strategy for short term cross-building energy prediction. Energy 2021, 215, 119208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, G.; Johra, H.; Georges, L.; Austbø, B. Transfer learning in building dynamics prediction. Energy Build. 2025, 330, 115384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harputlugil, T.; de Wilde, P. The interaction between humans and buildings for energy efficiency: A critical review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 71, 101828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmeter, C.F.; Zelenyuk, V. Combining the virtues of stochastic frontier and data envelopment analysis. Oper. Res. 2019, 67, 1628–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mystakidis, A.; Koukaras, P.; Tsalikidis, N.; Ioannidis, D.; Tjortjis, C. Energy Forecasting: A Comprehensive Review of Techniques and Technologies. Energies 2024, 17, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Dorjgochoo, S.; Park, H.; Lee, S. Personalized Federated Transfer Learning for Building Energy Forecasting via Model Ensemble with Multi-Level Masking in Heterogeneous Sensing Environment. Electronics 2025, 14, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Qi, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Elchalakani, M. Machine Learning Applications in Building Energy Systems: Review and Prospects. Buildings 2025, 15, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhou, J.; Liang, Y.; Yu, H.; Jing, R. Climate change impacts on city-scale building energy performance based on GIS-informed urban building energy modelling. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 125, 106331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Feng, H. Integrating urban building energy modeling (UBEM) and urban-building environmental impact assessment (UB-EIA) for sustainable urban development: A comprehensive review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 213, 115471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daissaoui, A.; Boulmakoul, A.; Karim, L.; Lbath, A. IoT and Big Data Analytics for Smart Buildings: A Survey. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 170, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Shah, A.; Leung, P.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q. A comprehensive review of the applications of machine learning for HVAC. DeCarbon 2023, 2, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, A.; AlMaeeni, S.; Attia, H.; Takruri, M.; Altunaiji, A.; Sanduleanu, M.; Shubair, R.; Ashhab, M.S.; Al Ali, M.; Al Hebsi, G. Smart City: Recent Advances in Intelligent Street Lighting Systems Based on IoT. J. Sens. 2022, 2022, 5249187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakawati, B.; Mousa, A.; Draidi, F. Smart energy management in residential buildings: The impact of knowledge and behavior. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y. A review of IoT applications in healthcare. Neurocomputing 2024, 565, 127017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, A. Deep learning-based optimization of energy utilization in IoT-enabled smart cities: A pathway to sustainable development. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 2946–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuna, G.; Ediga, P.; Akshatha, S.; Anupama, P.; Sanjana, T.; Mittal, A.; Rajvanshi, S.; Habelalmateen, M.I. Smart energy management: Real-time prediction and optimization for IoT-enabled smart homes. Cogent Eng. 2024, 11, 2390674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Xia, M.; Chen, Q.; Chen, F. A data-model fusion dispatch strategy for the building energy flexibility based on the digital twin. Appl. Energy 2023, 332, 120496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, A.; Arendt, K.; Johansen, A.; Sangogboye, F.C.; Kjærgaard, M.B.; Veje, C.T.; Jørgensen, B.N. A digital twin framework for improving energy efficiency and occupant comfort in public and commercial buildings. Energy Inform. 2021, 4, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renganayagalu, S.K.; Bodal, T.; Bryntesen, T.-R.; Kvalvik, P. Optimising Energy Performance of buildings through Digital Twins and Machine Learning: Lessons learnt and future directions. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Applied Artificial Intelligence, ICAPAI 2024, Halden, Norway, 16 April 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Xu, X. A hybrid evolutionary and machine learning approach for smart building: Sustainable building energy management design. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 65, 103709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henzel, J.; Wróbel, Ł.; Fice, M.; Sikora, M. Energy Consumption Forecasting for the Digital-Twin Model of the Building. Energies 2022, 15, 4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnecco, V.M.; Vittori, F.; Pisello, A.L. Digital Twins for Decoding Human-Building Interaction in Multi-Domain Test-Rooms for Environmental Comfort and Energy Saving Via Graph Neural Networks. Energy Build. 2022, 279, 112652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, V.G.; Ruiz, G.R.; Bandera, C.F. Empirical and Comparative Validation for a Building Energy Model Calibration Methodology. Sensors 2020, 20, 5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agouzoul, A.; Tabaa, M.; Chegari, B.; Simeu, E.; Dandache, A.; Alami, K. Towards a Digital Twin model for Building Energy Management: Case of Morocco. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 184, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.-K.; Park, D.-H.; Park, H.; Kwak, Y.; Kim, S.-H. Energy Planning of Pigsty Using Digital Twin. In Proceedings of the ICTC 2019—10th International Conference on ICT Convergence: ICT Convergence Leading the Autonomous Future, Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 16–18 October 2019; pp. 723–725. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Herrero, J.M.; Lopez-Guede, J.M.; Abascal, I.F.; Zulueta, E. Energy and thermal modelling of an office building to develop an artificial neural networks model. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Niu, J.-L. Optimal building envelope design based on simulated performance: History, current status and new potentials. Energy Build. 2016, 117, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Task | Objective | Key Metrics | Common Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Term Load Forecasting | Predict energy use over a short period (e.g., hourly, daily) | Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Coefficient of Variation of RMSE (CV(RMSE)) | ARIMA, LSTM, RNNs, SVR [23,24] |

| Energy Benchmarking | Compare a building’s energy performance against similar buildings or standards. | Energy Use Intensity (EUI), Energy Cost | Regression Analysis, Neural Networks, Cluster Analysis [25,26] |

| Simulation Calibration | Adjust a physics-based model to match real-world energy consumption data | Coefficient of Determination (R2), CV(RMSE) | Inverse Modeling, Optimization Algorithms (e.g., Genetic Algorithms) [27,28,29] |

| Post-Retrofit Evaluation | Assess the energy savings achieved after implementing efficiency measures | Savings, Energy Use Reduction | Baseline Models, Inverse Regression Models [30,31,32,33] |

| Architecture | Core Strength | Typical Forecasting Horizon | Data Requirements | Key Limitations for Building Energy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCN (1D) | Excellent at extracting local, translation-invariant patterns (e.g., daily load shapes) | Short-Term (Hourly, Daily) | Moderate | Struggles with long-term dependencies (e.g., the effect of a cold day several days prior). Primarily spatial, it requires careful framing for time series. |

| LSTM/GRU | Designed to capture long-term temporal dependencies and sequential patterns. | Short to Medium-Term (Hourly to Weekly) | High | Computationally intensive to train. It can be slow for very long sequences. May forget irrelevant historical information. |

| Transformer | Superior at modeling extremely long-range dependencies via self-attention mechanisms. All parts of the sequence are related directly. | All horizons excel in the long term | Very High | High computational and memory complexity; requires massive amounts of data to train effectively from scratch; prone to overfitting on small building datasets. |

| Hybrid (e.g., CNN-LSTM) | CNN extracts features from sub-sequences; LSTM models the temporal evolution of these features. | Short to Medium-Term | High | Complex model architecture, requiring careful tuning. Combines the computational demands of both components. |

| Study Reference | Combined Categories | Hybrid Approach Description | Reported Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| [110] | Ensemble + DL | RF used for feature selection, LSTM for sequence prediction | Higher accuracy than individual models |

| [32] | Data-Driven + Physics-Based | Physics laws embedded as constraints in neural network training | Improved generalizability, reduced data needs |

| [110] | Signal processing + ensemble ML | CEEMDAN for decomposition, XGBoost for regression | Enhanced prediction stability and accuracy |

| [179] | Multiple ML (stacking) | Predictions from 4 base models into a meta-learner (LR) | Superior accuracy and robustness |

| Region | Number of Studies (Sample) | Primary Modeling Focus | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Americas | ~35% | Advanced ML, Simulation Calibration | Strong policy drivers, high data availability |

| Europe | ~30% | ||

| Statistical Benchmarking, DL, Hybrid Models | Driven by EPBD, focus on existing building stock. | ||

| Asia | ~25% | SVM, ANN, Ensemble methods | Rapid urbanisation, growing smart building focus |

| Africa | ~10% | Classical ML, statistical models | Emerging field, challenges with data scarcity |

| References | Model Category | Example Models | MAE | R2 | RMSE | CV | Scalability | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [76,77] | Statistical Models | Linear Regression, ARIMA | 8–15% | 0.70–0.85 | 10–20% | 0.12–0.25 | Moderate | High |

| [88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149] | Machine Learning | SVM, Random Forest, XGBoost | 5–12% | 0.80–0.95 | 8–15% | 0.08–0.20 | High | Moderate |

| [150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161] | Deep Learning | LSTM, CNN, Autoencoders | 3–8% | 0.90–0.98 | 5–10% | 0.05–0.15 | High | Low |

| [162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174] | Ensemble Methods | Bagging, Boosting, Stacking | 4–10% | 0.85–0.97 | 6–12% | 0.07–0.18 | High | Moderate to Low |

| [175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185] | Hybrid Models | GP + ANN, LSTM + SVM | 2–6% | 0.92–0.99 | 4–8% | 0.04–0.12 | Moderate | Low |

| Study and Focus | Core Methodology | Application Context | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unit Commitment with Renewables (Alazemi et al., 2024) [201] | An “add-on tailor” model for prediction error correction, using advanced regression or ML. | Improving day-ahead unit commitment by enhancing the accuracy of renewable generation and reverse predictions. | RMSE Reduction: 15–30% in wind/solar forecasting vs. baseline models. Economic Impact: 2–5% reduction in total operational costs for the grid |

| Multi-Energy Microgrid Operation (Jia et al., 2025) [202] | Safe policy learning (safe reinforcement learning) | Coordinating electricity, heat, and green hydrogen storage in microgrids while managing network congestion. | Achieved ~12% lower operating costs compared to rule-based strategies. Zero constraint violations during testing, ensuring system reliability. |

| Fast Charging for Batteries (Sayed et al., 2025) [203] | Random Forest-enhanced electro-thermal-degradation model. | Optimizing electric vehicle charging protocols to balance speed, battery temperature, and long-term health. | Reduced by 25% compared to standard constant-current protocols. Limited capacity fade to <2% over 1000 simulated cycles, significantly better than conventional fast-charging. |

| Reference | Method | Data Sources | Accuracy | Deployment | Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [54] | Engineering Calculations | Simplified building information | Variable | Design. End-use evaluations. Highly flexible. | Limited accuracy. |

| [60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204] | Simulations | Detailed building information | High | Design. Compliance. Complex buildings. Cases where high accuracy is necessary. | Dependent on user skill and significant data collection. |

| [76,77] | Statistical | Dataset of existing buildings | Average | Benchmarking systems. Simple evaluations. | Dependent on statistical data. Limited accuracy. |

| [88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185] | Machine Learning | Large dataset | Average to high | Buildings with highly detailed data collection. Complex problems with many parameters. | Model construction is complicated. Do not consider direct physical characteristics. |

| Dataset | Dataset Source | Description | Building Type | Survey Content | Spatial Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CER Smart Metering Project [205] | Irish Social Science Data Archive | Half-hourly meter data from 5000 Irish homes and small businesses is utilized in the Smart Electricity Metre Customer Behavior Test Project (CBT) to evaluate the effect on consumer electricity consumption. | Residential and Small/Medium Enterprises | - | Smart meter data |

| Energy Disaggregation Data Set (REDD) [206] | Massachusetts Institute of Technology | Contains consumption data for six families spanning eighteen days in the spring of 2011 and is used for energy disaggregation research, which identifies the contributions of individual appliances from a composite electrical signal. | Residential Buildings | Electricity meter, Appliance | |

| Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey (CBECS) [207] | U.S. Department of Energy and Environmental Protection Agency | Approximately 6 million commercial buildings have been assessed, according to the most recent study conducted in 2018 | Commercial Buildings | Building information, equipment information | Regional, Single-building |

| National Non-Domestic Building Stock (NDBS) [68] | UK Department for Environment and Transport | Creates a comprehensive profile of the non-residential buildings in England and Wales by integrating real data at the building level, including information on energy use and efficiency, the geometry, and materials of each non-residential building | Non-residential buildings, including industrial buildings | Building physical characteristics, building geometric dimensions, and the main equipment overview | Single-building |

| Global Energy Forecasting Competition [208,209,210] | Dr. Tao Hong’s team | GEFCOM, which focused on short-term load forecasting using hourly load and outside temperature data, was held in 2012, 2014, and 2017 | Distribution Area | Hourly meteorological data (temperature) and load data, holiday information | Distribution area |

| Building Performance Database (BPD) [211] | Lawrence Berkeley National Lab | The extensive dataset of energy-related information for US residential and business structures | Building energy consumption; Regional energy consumption | building type, location, and physical characteristics | Regional, Single-building |

| The Building Data Genome Project [212,213] | Clayton Miller et al. | Data on energy use for buildings serving a range of purposes, including households, workplaces, schools, and healthcare institutions, in nations like the USA and the UK | Building energy consumption | The whole building’s electricity meter data | Single-building |

| Technique | Application Details | Reported Performance Gain |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-Building Transfer Learning [224] | An LSTM model pre-trained on a source office building (1 year of data) was fine-tuned on a target building with only two weeks of data. | 20% lower MAPE compared to a model trained from scratch only on the two weeks of target data. |

| Geographical Transfer with Adjustment [225] | Forecasting energy use for a school in Canada by transferring knowledge from schools in different regions, with seasonal and trend adjustments. | 11.2% improvements in prediction accuracy (R2) over a model using only one month of the target school’s data. |

| Data Augmentation with GANs [223] | Used a Bidirectional GAN (BiGAN) to generate synthetic building load data to augment a small real dataset for model training. | Achieved comparable accuracy to models trained with 80% more real data, effectively mitigating data scarcity. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Phiri, L.; Olwal, T.O.; Mathonsi, T.E. A Comprehensive Review of Data-Driven and Physics-Based Models for Energy Performance in Non-Domestic Buildings. Energies 2025, 18, 6481. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246481

Phiri L, Olwal TO, Mathonsi TE. A Comprehensive Review of Data-Driven and Physics-Based Models for Energy Performance in Non-Domestic Buildings. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6481. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246481

Chicago/Turabian StylePhiri, Lukumba, Thomas O. Olwal, and Topside E. Mathonsi. 2025. "A Comprehensive Review of Data-Driven and Physics-Based Models for Energy Performance in Non-Domestic Buildings" Energies 18, no. 24: 6481. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246481

APA StylePhiri, L., Olwal, T. O., & Mathonsi, T. E. (2025). A Comprehensive Review of Data-Driven and Physics-Based Models for Energy Performance in Non-Domestic Buildings. Energies, 18(24), 6481. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246481