Abstract

Balancing (real-time) market price forecasting is a vital enabler for renewable integration, storage arbitrage, and risk-aware trading, yet the literature remains fragmented and underdeveloped. This review addresses these shortcomings by systematically categorizing and evaluating studies across prediction horizons, modeling paradigms, and data-engineering practices. We show that enriching forecasts with auxiliary features, such as day-ahead prices, net imbalance volumes, renewable forecast errors, and meteorological inputs, substantially reduces error relative to price-only baselines. Probabilistic frameworks, while invaluable for providing risk envelopes in bidding strategies, are still underexploited. Typical reported accuracy spans mean absolute percentage errors of approximately 3–10% for very short-term (1–6 h ahead) horizons, 10–20% for mid-term horizons (12–24 h ahead), and around 25% for longer horizons (24–36 h ahead), with spikes and rapid ramps driving most residual error. From this synthesis, we identify the following four critical research gaps: (1) inadequate modeling of price spikes and ramps, (2) limited innovation in pre- and post-processing techniques, (3) sparse adoption of profit-driven (revenue-aware) evaluation, and (4) weak segmentation of distinct temporal regimes. By mapping prevailing methodologies, benchmarking performance, and highlighting emerging paradigms, such as feedback-driven, risk-aware, feature-enriched pipelines, this review delineates the state of the art and proposes a research agenda focused on maximizing economic value.

1. Introduction

Electricity price forecasting plays a key role in energy markets by supporting the optimization of trading decisions, reducing financial exposure, and contributing to grid reliability. As variable renewable energy penetration continues to increase, the use of intelligent systems for scheduling and market trading is becoming essential [1,2]. By the end of 2024, global cumulative installed capacity reached 1133 GW for wind power and 1865 GW for solar power [3], and high day-ahead market (DAM) prices are increasingly encouraging these producers to participate more actively in spot markets.

These variable renewable energy producers commit to delivering a specific amount of energy at a given time. If they fail to meet this commitment, the transmission system operator must correct the imbalance. This real-time correction creates a cost, known as the imbalance cost. Wind generators are especially vulnerable to this cost because of their intermittent nature and less accurate day-ahead forecasts. While imbalance cost originates from forecast errors, its amount is not solely determined by forecasting accuracy; rather, it is significantly influenced by market prices. While imbalance costs represent a financial risk for variable renewable generators, elevated electricity prices in day-ahead markets (DAMs) and balancing markets (BMs) simultaneously present economic opportunities. Renewable power plants with low operating costs can achieve substantial profits when market prices are high, which is a dynamic that has been particularly evident across various European markets in recent years.

Participating in electricity markets involves inherent risks, and intraday and imbalance price forecasting is gaining importance for optimal bidding strategies [4]. Despite the growing relevance of this, research on imbalance price forecasting remains substantially limited compared to the extensive literature on wind power [5] and day-ahead price forecasting [6]. To mitigate risks effectively, bidding strategies must account for price uncertainties. Forecasts play a critical role in quantifying the uncertainty of imbalance prices and in tracking their evolution over time to infer dispatch conditions. They are essential not only for effective participation in balancing markets but also for optimizing bidding strategies in day-ahead and intraday markets [7].

In addition, Virtual Power Plants (VPPs) optimize profitability by aggregating and coordinating distributed energy resources for strategic participation in day-ahead, intraday, and balancing markets. They employ price forecasting algorithms, energy-storage arbitrage (charging when prices are low and discharging when prices peak), and demand-side flexibility to minimize operational costs and imbalance penalties [8]. Accurate balancing market price forecasts can cut imbalance costs tied to day-ahead bids of variable renewables by up to 87.6%, yielding profit improvements of 6.6% under specific scenarios [9]. VPPs can increase gains by revenue stacking across multiple market timeframes [10], if the balancing prices are accurately estimated. Accurate balancing price forecasts can also enable optimal storage scheduling, thereby increasing revenues for VPPs [11].

This review pays attention to statistical and computational intelligence methods that predict the price for a specific time point or interval in the future. They are of great practical interest, since they are used as exogenous variables in optimal bidding optimization problems. In the literature, past studies typically focus on market structure, auction rules, and bidding protocols [4]. Some studies use uncommon error evaluation procedures, which makes them difficult to assess and compare. Also, the test periods of some methods are too short to draw a conclusion. By taking these into account, the present review makes significant effort to compare the methods in order to (i) find out the expected error ranges of current methods depending on the forecast horizons and (ii) highlight the recent trends and existing challenges.

Early studies on balancing market dynamics have primarily focused on electricity market design to facilitate the large-scale integration of variable renewable energy sources [12], as well as on identifying and mitigating imbalance risks through improved system flexibility, grid coordination, and pricing mechanisms [12,13]. Other research has addressed the uncertainty inherent in market conditions and has proposed risk-aware bidding strategies for day-ahead and intraday markets using optimization techniques under uncertainty [14]. While much of the literature emphasizes system-level or policy-oriented perspectives, only a limited number of studies have examined the balancing market from the generator’s viewpoint, which focuses on profit-maximizing strategies under uncertain conditions [15,16,17]. This shift reflects a growing recognition of the need for predictive tools and market mechanisms that support generation companies in navigating price volatility and operational uncertainty [18]. In response, this review aims to synthesize current forecasting approaches for balancing market prices, highlighting hybrid and probabilistic models, the prediction of extreme events such as price spikes and ramps, and the use of diverse market features to improve forecast accuracy.

1.1. Motivation

Over the past five to six years, electricity prices have shown a significant upward trend in spot markets. This shift has created significant profit opportunities, particularly for producers and operators of renewable generating units with low marginal costs and minimal maintenance expenditures. Unlike producers with fixed-price or long-term government-backed contracts, those participating in spot trading have been able to leverage periods of elevated market prices. However, for renewable sources such as wind and solar, the main challenge remains in the balancing or real-time markets. Due to their intermittent and non-dispatchable nature, these sources face considerable forecasting difficulties and imbalance cost exposure. Therefore, from the perspective of renewable generators, improving forecasting accuracy for the balancing or real-time market becomes important not only to manage risks but also to contribute to grid reliability.

1.2. Contribution

This work offers the first dedicated and systematic review focused exclusively on price forecasting in balancing and real-time electricity markets, a domain often overshadowed by the much larger bodies of research on wind power and day-ahead price forecasting. While balancing market studies date back nearly three decades, their progress has been constrained by the inherent complexity of market mechanisms and by restricted or opaque data availability. To address this gap, our review systematically structures the literature by methodology and forecast horizon, enhancing accessibility for both academic and practitioner audiences. It catalogs 48 forecasting studies, classifying them by pre-processing, forecasting architecture, and hybrid design, while also identifying contributions that extend beyond price to alternative targets such as imbalance volume (IV), price premium (P), load (L), and classification tasks (C). It complements this by categorizing prediction horizons, explicitly linking accuracy degradation to lead time. Beyond methodological benchmarking, the review extends to revenue optimization, profit-aware evaluation, data latency constraints, and spike/ramp forecasting, where these aspects are explicitly synthesized.

1.3. Structure of the Review

Section 2 presents both point-based and probabilistic forecasting frameworks, detailing model selections, prediction horizons, and their relative performances. It covers pre-processing and post-processing techniques. Section 3 focuses on the integration of diverse market features to enhance forecast performance. Section 4 compares forecasting accuracy across different time horizons. Section 5 presents alternative prediction targets beyond price. Section 6 discusses market scope, test-period design, and metric selection, offering guidance for establishing benchmarks. Section 7 discusses revenue optimization and extreme events. This section highlights adaptive AI/data-driven forecasting frameworks incorporating feedback steps that recalibrate model parameters in response to financial outcomes. It underscores emerging methodologies such as reinforcement learning and volatility regime detection, aimed at improving forecast responsiveness and maximizing economic utility in the high-variance balancing environment. Finally, Section 8 outlines open challenges and provides future research directions.

2. Forecasting Methodologies

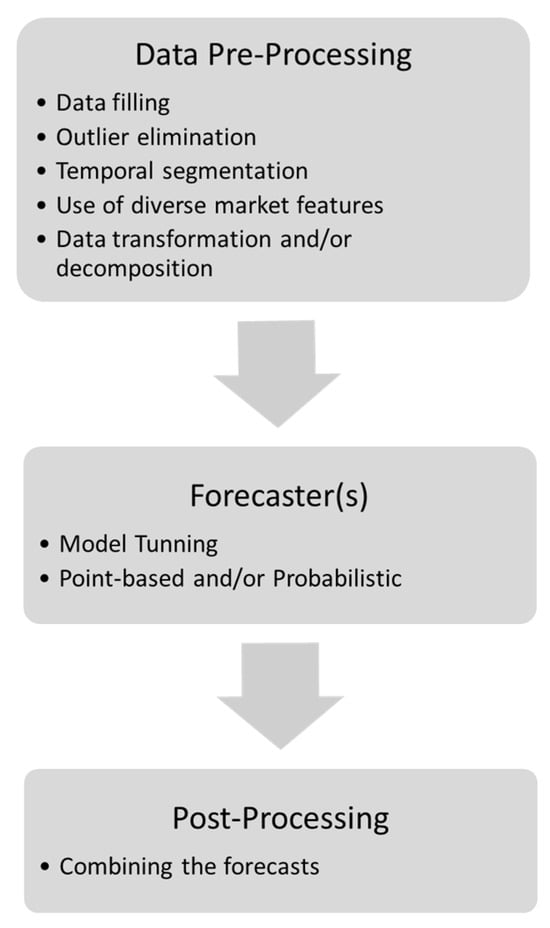

A three-stage pipeline is typically adopted for electricity balancing price forecasting (Figure 1). (i) Pre-processing. Missing values are imputed, extreme outliers removed, and the 5 to 15 min settlement series are resampled; exogenous drivers, including net-imbalance volume, renewable-generation output, weather variables, and day-ahead prices, are fed, after which data transforms or multiresolution decompositions (e.g., log scaling and discrete wavelet transform) are applied. (ii) Forecaster(s). Hyperparameter-optimized models are trained on the engineered feature set as follows: gradient-boosted trees and sequence models (LSTM/Transformer) are prevalent for point forecasts, whereas quantile-regression forests and Bayesian temporal CNNs dominate full-probabilistic pipelines, often coupled with loss functions to capture abrupt price excursions. (iii) Post-processing. Individual outputs are fused through weighted averaging or stacking, lowering MAE/RMSE and delivering prediction forecasts and intervals.

Figure 1.

Forecasting pipeline.

The remainder of this section therefore treats point-based and probabilistic forecasting frameworks separately, detailing the model choices, prediction horizons, and their performances.

2.1. Point-Based Forecasting Methods

In electricity price forecasting for balancing and real-time markets, point-based (deterministic) forecasting methods remain predominant. These approaches aim to generate a single and actionable prediction for market prices. Classical time series models such as ARIMA [19,20,21], SARIMA [22,23], ARMA [24,25], and ARMAX [26] are employed due to their simplicity and interpretability. Meanwhile, machine learning methods such as Support Vector Regression (SVR) [27], Random Forest (RF) [24,28], XGBoost [15,20,21], and LightGBM [15,29] have become increasingly popular for their nonlinear learning capabilities and robustness to high-dimensional data. Neural network-based methods like MLP [30], LSTM [31,32], and GRU [19,27] are also well represented, especially in recent hybrid deep learning frameworks GRU+CNN [27,33] and GRU+LightGBM [29]. These point-based models are typically preferred in forecasting tasks that require direct price estimation for market bidding or imbalance risk control, as the interpretability of a single numerical output is straightforward. Table 1 lists the methods used for forecasting and demonstrates the dominance of non-hybrid methods.

Recently, a Seasonal Attention-Based Bidirectional LSTM (SA-BiLSTM) framework for forecasting electricity imbalance prices in the British balancing market, using data from 2016 to 2019, was proposed by Deng et al. [15]. The model introduces a seasonal attention mechanism to enhance temporal feature extraction from 48 half-hourly periods each day, addressing inherent seasonality and autocorrelation structures in imbalance price dynamics. The SA-BiLSTM delivers point forecasts for 1- to 4-step ahead horizons and is evaluated against ten other deep learning and ML models (LSTM, BiLSTM, GRU, SVR, MLP, TCN, Transformer, XGBoost, ANN, and LightGBM). Empirical results show that SA-BiLSTM outperforms all benchmarks, achieving the lowest RMSE of 12.709 for 1-step (30 min) ahead, 17.169 for 4-step (2 h) ahead, and maintaining better forecast accuracy across all horizons.

There are also studies on the real-time locational marginal price (LMP). For instance, Feijoo et al. [34] present a new hybrid model, called the K-SVR, for LMP forecasting for real-time market. This model is tested by using publicly available data from the Pennsylvania–New Jersey–Maryland (PJM) market for the years 2005–2006, 2011–2012, and 2014–2015. They obtained hourly forecasting results, with MAPE1 values of 5.17% in 2006, 1.172% in 2012, and 4.341% for test days in 2015. The lower forecasting error in 2012 compared to 2006 and 2015 is reported to be mainly due to the lower variability in LMP data. This can be attributed to low frequency and lower magnitudes of spikes. Having said that, the authors conclude that when the forecasting data are more stable, i.e., have a lower variance, as in the case of 2011–12 data, K-SVR was able to obtain relatively superior results compared to the cases with high variability.

Forecasting balancing market (real-time) prices prior to the closure of the day-ahead market is challenging, as day-ahead prices serve as a key reference signal. Ma et al. [35] propose a neural network-based LMP forecasting approach utilizing the Decoupled Extended Kalman Filter (DEKF) with UD factorization and sequential updating. Neural networks are trained to predict real-time LMPs both before and after the day-ahead market is cleared. These two models are evaluated on the following two different markets: PJM (with training data from July 2000 to June 2002) and New England (with training data from March to June 2003). Results indicate that incorporating day-ahead market information improves real-time LMP forecasting accuracy significantly, with MAPE values of 20.02% and 17.29% before and after market clearance, respectively. Notably, the study also demonstrates the transferability of a predictive model across different markets.

Separating forecasts by calendar context (weekends and holidays) can reduce error. Building on this insight, a method integrating the recurrent neural network (RNN) and fuzzy c-means (FCM) for forecasting locational marginal prices (LMPs) in a deregulated electricity market was presented by Hong and Hsiao [36]. To account for the volatility of LMPs, weekdays, Saturdays, and Sundays were considered separately. Actual market data from the Kenney and Benning areas of the PJM market, covering the period from 1 April to 31 May 1999, were used to demonstrate the applicability of the proposed approach. Mean absolute error (MAE) values for one-hour-ahead LMP forecasts were found to range from 2.30 to 3.76 across the different day types and locations. It was shown that separating the data by day type led to better forecasting performance than grouping all data together.

Several methods, including linear statistical baselines (e.g., ARIMA and SARIMAX), classical machine learning methods (e.g., RF, XGBoost), and deep learning architectures (e.g., SH-DNN, MH-RNN) across different forecast horizons ranging from 1 to 6 h ahead were compared recently by O’Connor et al. [21]. Results indicate that prediction accuracy decreases considerably as the forecast horizon increases. For example, the best-performing model (MH-RNN) achieves a MAE of ~7.6 EUR/MWh at 1 h ahead, which rises to approximately 11 EUR/MWh at 6 h ahead, indicating a 45% degradation in forecast precision over longer horizons. The authors acknowledge the inherent limitations of point-based forecasting models, particularly their inability to accurately capture extreme price events, and briefly suggest probabilistic forecasting as a valuable direction for future research. This recognition aligns with the understanding that probabilistic approaches can be better suited for risk management, decision-making under uncertainty, and system reliability planning.

2.2. Probabilistic Forecasting Methods

Probabilistic forecasting methods are recognized for their value in risk quantification and uncertainty management. These approaches provide a distribution or interval of possible outcomes, making them especially useful for risk-averse applications such as hedging, reserve planning, and imbalance cost exposure mitigation. Well-established probabilistic techniques identified in the literature include Quantile Regression (QR) [37] and Quantile Regression Forests (QRF) [25], Gaussian Processes (GP) [38], Probabilistic Neural Networks (PNN) [17], and Monte Carlo-based methods (MCM) [39]. Two-step approaches, such as the Two-Step Probabilistic Approach (TSPA) [30], are particularly noteworthy as they first perform regime classification and subsequently estimate the corresponding conditional distributions. These models enhance decision-making under uncertainty by estimating confidence bounds or quantiles.

A two-stage hybrid approach, in which accurate point estimates are first generated and reliable prediction intervals are subsequently constructed through uncertainty quantification, was proposed by Tahmasebifar et al. [40]. Their pipeline approach and hybrid method, WT-MI-ELM-MLE-PSO, incorporates Wavelet Transform (WT) pre-processing, Extreme Learning Machine (ELM), the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), and the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm, to predict both point estimates and probabilistic intervals of electricity prices in real-time markets. To show the effectiveness of the proposed approach, the study uses load and price data from New South Wales, a region of the five-zone Australian National Electricity Market. The prices for the four considered weeks of the four determined seasons in 2008 are estimated for one hour ahead. The average values of the point forecasting indexes in the real-time market are by MAE 0.50 $/MWh for February, 1.91 $/MWh for May, 1.80 $/MWh for August, and 0.70 $/MWh for November; by MAPE 2.13% for February, 4.70% for May, 4.53% for August, and 2.86% for November; and by RMSE 0.73 $/MWh for February, 2.68 $/MWh for May, 2.64 $/MWh for August, and 1.04 $/MWh for November.

Carefully designed model architectures, particularly those incorporating well-suited kernel functions, can lead to substantial improvements in both forecasting accuracy and uncertainty quantification. For instance, Mori and Nakano [38] propose an efficient method that makes use of the Gaussian Process (GP) of hierarchical Bayesian estimation with the Mahalanobis kernel for the prediction of LMPs. For one-hour-ahead LMP prediction, the hourly LMP of real data (from 1 to 31 July in 2011, 2012 and 2013) of Independent System Operator New England (ISO-NE) is applied. According to the results, the proposed Method C achieved a 21.2% reduction in the average error.

A probabilistic forecasting methodology was developed by Ji et al. [41] to predict real-time locational marginal prices (LMPs) using a time-inhomogeneous Markov Chain with forecast horizons of 6 and 8 h. The real-time LMP is computed through the product of predicted price state transition matrices, which are estimated using the Monte Carlo method. To validate the proposed approach, historical five-minute load profile data from ISO New England, averaged over three independent days, are used to construct a representative 24 h load profile on the PJM 5-bus system. Two point prediction metrics, namely maximum a posteriori (MAP) and minimum absolute error (MAE), are employed to evaluate forecasting performance. Forecast accuracy is measured using a comparable metric of the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), yielding average values of 14.25% for MAP and 11.75% for MAE predictions across five buses.

Klæboe et al. [42] benchmark probabilistic forecasting models for the balancing market premium in Norway’s NO2 price zone. Balancing market premium is defined as the difference between the balancing and the day-ahead market prices. However, the study ultimately shows that the tested forecasting methods fail to produce sufficiently accurate and reliable results for the balancing market premium. This highlights the inherent volatility and unpredictability of the balancing market, which limits the practical applicability of standard point-based and probabilistic models. Independently of this, Maciejowska et al. [43] predicted the sign of the difference between the day-ahead and balancing market prices. The best-case accuracy achieved in this study is 57.3%, whereas Dinler [44] reported a higher accuracy of 61.08% for a similar forecasting task in the Turkish market. It should be noted that this moderate level of accuracy cannot be translated into economical gains directly, since the magnitude of the difference is also important. These two alternative forecast targets are denoted by P and IVC in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

In probabilistic forecasting, the performance metrics, such as Prediction Interval Coverage Probability (PICP), Average Coverage Error (ACE), Prediction Interval Normalized Average Width (PINAW), Winkler score, Coverage Width Criterion (CWC), and Continuous Ranked Probability Score (CRPS), are essential for interpreting results and for capturing the fundamental trade-off between reliability (the proportion of realizations contained within the predicted intervals) and sharpness (the narrowness of those intervals). For example, Tahmasebifar et al. [40] report improved ACE, PINAW, and CWC alongside RMSE and MAPE when comparing their hybrid model, while Mori and Nakano report empirical coverage at ±σ, ±2σ, and ±3σ (e.g., 89.8%, 100%, and 100% with a Mahalanobis kernel) as an implicit calibration check [38]. Recent imbalance forecasting work further emphasizes the reliability–sharpness trade-off using quantile loss, Winkler score, and CRPS, defining reliability as the fraction of realized values below forecast quantiles [32].

2.3. Pre-Processing and Post-Processing

Both pre-processing and post-processing play a critical role in improving prediction accuracy. Pre-processing is not limited to handling missing data or eliminating outliers; advanced transformation techniques such as Fourier Transform (FT) [20], Wavelet Transform (WT) [27], k-NN [45], LSTM [44], and CNN model [33] have been shown to effectively extract hidden patterns, especially when targeting a specific forecasting horizon. Despite this, most studies still focus on conventional approaches like normalization or rolling averages [31], often overlooking the transformative potential of a deeper signal decomposition. Table 1 presents the pre-processing methods along with their corresponding studies.

Table 1.

Methods used in the literature.

Table 1.

Methods used in the literature.

| Pre-Processing | Non-Hybrid | Hybrid | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA LOF LSTM QCAE CNN WT GoogLeNet FT k-NN STL SHAP | [31] [29] [44] [27] [27,33] [20,27,40] [33] [20] [45] [29] [29] | MLR SARMA ARMA ARM EXO DDM ANN SARIMA MLP TSPA GP MLFFN MCM OPF ARIMA RA LSTM ARMAX MWA DEKF AR HMM SSM CS ARX PM GB RF RBF GRNN PNN LNN RNN TFT RSM ARMFST3 | [46](IV) [42](IV) [42](P), [24,25,47] [42](P) [42](P) [42](IVC) [15,24,36,48] [22,23],[49](IV, P, IVC) [15,19,30,35,38], [50](IV),[51](IVC) [30] [30,38] [52] [39] [53] [31,54],[55](L),[19,20,21,24,27,33],[50](IV), [32](IV) [31] [31],[46](IV), [19,20,45,56],[51](IV), [15,48,57,58] [26,47] [26] [35] [19,41] [49](IV, P, IVC) [47] [47] [42](P),[43](P) [43](IVC) [28],[32](IV) [20,21,24,28],[46](IV), [51](IVC), [59](IVC),[55](L) [50](IV),[55](L) [50](IV) [50](IV),[17,25] [50](IV) [48] [48] [48] [60](IV) | FL BDLM GARCH AR_GARCH LightGBM Naive LassoB GAMLSS-L CNN SVR DNN GRU HFnet LASSO LSTNet-Skip k-NN HM CROST PatchTST VAR LR DT XGBoost BiLSTM SA- BiLSTM TCN Transformer SH-DNN LEAR MH- RNN- DNN QR QRF RAND HIST | [55](L) [48,61] [61] [61] [15,29], [51](IVC) [59](IVC) [17,21],[42](P) [17] [17] [19,20,27] [15,19,20,21,27] [27] [15,19,27,29,48] [27] [20,33] [33] [56](S) [19,21] [42](IVC) [42](IV) [56] [19] [19,45],[60](IV), [10] [19] [15,20,21,57], [51](IVC) [15],[32](IV) [15] [15] [15] [21] [21] [21] [25,37],[32](IV), [57] [25],[32](IV),[57] [42](IV) [42](IV) | SARIMA+ MP k-NN+ SVM+ SVR ELM+ PSO QR+ XGBoost RNN+ FCM LoR+ SVC+ RF+ SGB+ XGBoost W-GRU W-HFnet GRU+ CNN Prophet+ TFT+ k-NN LSTM+ GRU BiLSTM+ GRU CNN+ LSTM CNN+ BiLSTM GRU+ LightGBM RF+ LightGBM+ MLP+ XGBoost GHTnet (GRU+ CNN) SLGSEF (STL+ LightGBM+ GRU+SHAP) | [62] [34] [40] [28] [36] [44] [33] [33] [19,20,27,33] [56] [19] [20] [20] [20] [29] [51](IVC) [33] [29] |

Abbreviations: ANN: Artificial Neural Networks; AR: Auto-Regressive; AR_GARCH: Autoregressive Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity; ARIMA: Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average; ARM: ARMA with Markov Model for State; ARMA: Auto-Regressive Moving Average; ARMAX: Autoregressive Moving Average with Exogenous Variables; ARMFST3: AR-Multi-Factor Skew-t type 2 Density Model; ARX: Autoregressive model with exogenous inputs; BiLSTM: Bidirectional LSTM; BDLM: Bayesian Dynamic Linear Model; CNN: Convolutional Neural Network; CS: Cubic Spline; DDM: Duration-Dependent Markov; DEKF: Decoupled Extend Kalman Filter; DF: Data Fusion; DNN: Deep Neural Network; DRNN: Diagonal Recurrent Neural Network; DT: Decision Tree; DWT: Discrete Wavelet Transform; ELM: Extreme Learning Machine; FCM: fuzzy-c- means; FL: Fuzzy Logic; FT: Fourier Transform; GAMLSS-L: GAMLSS with Lasso; GARCH: Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity; GB: Gradient Boosting; GHTnet: Tri-Branch CNN-GRU Network; GM: Grey Model; GP: Gaussian Process; GRNN: Generalized Regression Network; GRU: Gated Recurrent Unit; HFnet: Holiday-feature GRU; HIST: Random from Historical Values (Markov state-based); HM: Hour-specific Markov; HMM: Hidden Markov Model; k-NN: k-Nearest Neighbor; LassoB: Lasso with Bootstrap; LEAR: Lasso Estimated Autoregressive Regression; LightGBM: Light Gradient Boosting Machine; LNN: Linear Neural Network; LOF: Local Outlier Factor; LoR: Logistic Regression; LR: Linear Regression; LSTM: Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network; LSTNet-Skip: Long- and Short-Term Time-series Network with Skip Connections; MC: Markov Chain; MCM: Monte Carlo Method; MH-RNN-DNN: Multi-Headed Hybrid DL with LSTM & DNN Branches; MI: Mutual Information; MLFFN: Multi-layer Feed-Forward Neural Network; MLP: Multi-Layer Perceptron Network; MLR: Multiple Linear Regression; Multi-Layer Perceptron Network; MWA: Moving Weighted Average; MP: Markov Process; OPF: Optimal Power Flow; PatchTST: Transformer-Based Time Series Model; PM: Probit Model; PNN: Probabilistic Neural Network; QCAE: Quadruple-branch Convolutional AutoEncoder; QR: Quantile Regression; QRF: Quantile Regression Forest; RA: Rolling Average; RAND: Random from Distribution (Markov state-based); RBF: Radial Basis Function; RF: Random Forest Algorithm; RNN: Recurrent Neural Network; RSM: Regime-Switching Model; SA-BiLSTM: Seasonal Average BiLSTM; SARIMA: Seasonal Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average; SARMA: Seasonal Autoregressive Moving Average; SGB: Stochastic Gradient Boosting; SH DNN: Single-Headed Deep Neural Network; SHAP: Shapley Additive Explanation; SSM: State Space Model; STL: Seasonal-Trend decomposition using Loess; SVC: Support Vector Classifier; SVM: Support Vector Machine; SVR: Support Vector Regression; TCN: Temporal Convolutional Network; TFT: Temporal Fusion Transformer; TSPA: Two-Step Probabilistic Approach; VAR: Vector Auto-Regressive; W-GRU: Wavelet GRU; W-HFnet: Wavelet HFnet; WT: Wavelet Transform; and XGBoost: Extreme Gradient Boosting. IV: Used for (Net) Imbalance Volume Prediction; L: Used for Load Prediction; IVC: Used for Imbalance Volume Classification (i.e., Prediction of Surplus or Shortage); C: Used for classifying the sign of the difference between DAM and BM prices; S: Used for Spike Occurrence Prediction; P: Used for Balancing Market Premium Prediction (i.e., the price difference between balancing and day-ahead markets).

Table 2.

Prediction horizons.

Table 2.

Prediction horizons.

| Short-Term (A Few Min–60 Min) | Medium-Term (1–12 h) | Long-Term (12–24 h) | Very Long-Term (24 Hour and Longer) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 m 5 m,…, 50 m 15 m 15 m,…, 60 m 30 m 30 m–60 m | [24,27,29] [45] [31] [10,33], [46](IV), [25,54], [60](IV) [30,57,58] [17,48,61] [15,21,37] | 1 h 1 h, 1.5 h, 2 h 1 h,…, 2.5 h 1 h,…, 3 h 1 h,…, 6 h 1 h,…, 8 h 1 h,…, 12 h 2 h 4 h 6 h,…,12 h 6 h, 8 h | [42](IV, IVC, P) [34,36,38], [49](IV, P, IVC), [46](IV), [20],[43](P, IVC), [40] [15] [58] [19] [30] [21] [28,52,63], [56](S), [59] (IVC), [51](IV, IVC), [37] [45,64] [32](IV) [35] [41] | 12 h,…, 24 h 13.5 h,…, 24 h 18 h,…, 24 h 24 h | [52,63],[56](S), [59](IVC), [51](IV, IVC), [37],[42](IV, P, IVC), [35] [49](IV, P, IVC) [47] [44](C) [40] | 24 h,…, 32 h 24 h,…, 36 h 24 h,…, 37.5 h 24 h,…, 42 h 24 h,…, 3 years 48 h 1 w–1 mo | [35] [42](IV, P, IVC), [49](IV, P, IVC) [47] [44](C) [55](L) [23] [50](IV) |

IV: Used for (Net) Imbalance Volume Prediction; L: Used for Load Prediction; IVC: Used for Imbalance Volume Classification (i.e., Prediction of Surplus or Shortage); C: Used for classifying the sign of the difference between DAM and BM prices; S: Used for Spike Occurrence Prediction; P: Used for Balancing Market Premium Prediction (i.e., the price difference between balancing and day-ahead markets).

Applying an LSTM autoencoder as a pre-processing step significantly improved the performance of multiple classifiers in the Turkish balancing market case study. Without the autoencoder, individual models such as Random Forest or Logistic Regression achieved accuracies around 57–59%, whereas with the autoencoder the hybrid ensemble reached over 61% accuracy [44]. This translated into tangible reductions in imbalance costs, with yearly savings of 6–11%. Similarly, in the Romanian imbalance volume forecasting study, adding a pre-processing stage where the imbalance sign was predicted and then incorporated into the dataset markedly improved forecasts. Across daily, monthly, and 8-month test horizons, including the imbalance sign reduced MAE and RMSE by nearly half and increased R-squared from 0.94 to 0.98 [51]. This demonstrates that pre-processing not only stabilizes the data against price extremes but also enriches the feature space with predictive signals, thereby strengthening both statistical fit and practical forecasting accuracy. Pre-processing can also include scaling and outlier trimming (e.g., capping prices above £140) such as in [15]. In another study [56], pre-processing involves variance-stabilizing transformations (arcsinh) to mitigate the effect of price extremes. As a result, the entire framework demonstrates competitive accuracy as follows: an RMSE of 35, outperforming strong baselines such as AE-LSTM (RMSE 49) and PatchTST (RMSE 42).

Post-processing, surprisingly, is less emphasized in the literature, although it holds strong potential for refining deterministic forecasts. Only a few studies apply the output fusion, such as in GRU+LightGBM [29], CNN+BiLSTM [20], W-GRU [33], or weighted output blending in [29], which have demonstrated significant improvements in accuracy. These approaches support the premise that post-hoc ensembling of multiple model outputs mitigates model-specific weaknesses and more effectively captures heterogeneous price dynamics.

3. Use of Diverse Market Features

In balancing and real-time markets, accurate price forecasting critically depends on the inclusion of features that reflect the underlying components influencing price formation. The availability and systematic utilization of such market-specific indicators are essential for improving forecast accuracy. The forecasting method involves the utilization of exogenous inputs in its implementation. While many studies incorporate standard market data such as load, renewable generation, and historical prices, only a limited number of works have explored the inclusion of fuel-related indicators, particularly natural gas prices which can significantly influence short-term marginal costs in the case of gas-dominated power supply. In line with the growing recognition of market-specific signals, such as imbalance volumes, up- and down-regulation activation requests, frequency deviations, regulation mileage, and reserve offer prices, the inclusion of Day-Ahead Market (DAM) prices in real-time or balancing price forecasting models has been explicitly emphasized in several studies. For instance, Ma et al. [35] demonstrated that omitting day-ahead market information significantly deteriorates forecasting accuracy. It can be said that forecasting balancing prices accurately before DAM closure can be challenging.

Inspired by this reasoning, Deng et al. [15] incorporates a range of fundamental features including de-rated margin (scarcity indicator), imbalance volume (IV), demand forecast errors, and wind/solar forecast errors. Importantly, while not explicitly built for spike classification, the model demonstrates improved performance under volatile or extreme conditions due to its attention-based design, implicitly improving the ability to anticipate significant price ramps. Simple ARMAX and Least Squares models in [26] incorporate a wide range of features, including cross-border electricity prices, national demand forecasts, generation capacities, outages, traded volumes, wind speeds, and temperatures.

The inclusion of demand contributes to improving forecast accuracy. Using demand data from Swedish power system, Brolin and Söder [39] describe a probabilistic model based on nonlinear time series processes with Monte Carlo simulations of the real-time balancing market prices. They also use exogenous variables such as hourly day-ahead spot market prices and hourly real-time balancing prices. In addition, the inclusion of market variables increases the likelihood of accurately modeling complex, nonlinear behaviors in these markets. For example, Bara and Oprea [51], Lucas et al. [28], and Molin [45] emphasize the predictive value of multi-dimensional features. Collectively, these findings reinforce the necessity of using a comprehensive, multi-source feature set to capture latent drivers of balancing and real-time market behavior.

Bara and Oprea [51] and Dinler [44] conduct a correlation analysis between the candidate market variables and the target variable to identify the most relevant predictors for the forecasting model. This analysis is used to filter and select the features for the proposed model. Specifically, both studies examine the Pearson correlation coefficients between variables such as total electricity consumption, system load, wind power generation, and the target imbalance volumes. The results demonstrate correlations between the selected features and the price, underscoring the importance of their incorporation into the forecasting framework.

Wind variability and demand are highlighted as primary price drivers in the Irish I-SEM market [25] and PJM [34]. Recent studies show that particularly influential explanatory variables include the Net Imbalance Volume, which directly reflects short-term supply–demand mismatches, and the Loss of Load Probability, which captures scarcity conditions [28,46]. Calendar effects, such as monthly seasonality and de-rated capacity margins, further enhance forecast accuracy by embedding system stress linked to seasonal load and availability patterns [15,43]. As previously emphasized, the day-ahead market price again emerges as a strong source of explanatory power [35].

4. Forecasting Horizons and Accuracy Dependency

The selection of forecasting horizons critically influences model design and ultimately prediction reliability. The majority of recent studies focus on short- to medium-term forecasting horizons, typically spanning from 5 min up to 12 h [24,27,28,29,52,63], in alignment with the real-time operational requirements of system operators. Long-term (12–24 h) and very long-term (>24 h) forecasting horizons have also been explored in works such as [23,35,47,52,56,63], which are particularly relevant for trading and bidding strategies in day-ahead market contexts.

Table 2 categorizes prediction horizons into short-term (a few minutes to 60 min), medium-term (1–12 h), long-term (12–24 h), and very long-term (>24 h). Despite progress in short- and medium-term forecasting (5 min–12 h), long-term predictions (12–24 h) remain elusive. For example, Klæboe et al. [42], attempting to predict the balancing market premium price (i.e., the price difference between balancing and day-ahead market), reported poor results and high error variability, even with multiple models applied in the NO2 price zone of Norway.

Forecasting accuracy sharply decreases as the horizon increases. For instance, Dimoulkas et al. [49] demonstrate that for a 1 h-ahead prediction in the Nordpool market using a Hidden Markov Model (HMM), the MAE for premium price forecasting was 0.74. However, when the horizon was extended to 12–36 h, the error increased significantly, reaching 1.2, which is illustrating the difficulty of longer-horizon prediction.

While short-term point-based forecasts using (e.g., LSTM [31,45,46,48], ANN [15,24,48], and SVR [15,21,27]) remain dominant for their direct usability in bidding and scheduling, there is a growing shift toward hybrid and deep learning-driven models that can accommodate richer feature sets and more volatile behavior. Still, horizon sensitivity and feature inclusion remain critical bottlenecks for achieving high accuracy, particularly beyond 12 h forecasts.

The choice of forecasting methodology also plays a critical role in determining accuracy. Early methods such as ARIMA, ARMAX, and MLP were often limited to short-term applications due to their inability to capture nonlinearity and multivariate dependencies. More recent deep learning models, including SA-BiLSTM [15] and hybrid Transformer-based architectures like the Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) [48], have demonstrated stronger capabilities in managing complex patterns and seasonality.

Forecast accuracy is tightly coupled with the model’s ability to integrate external features, especially day-ahead market prices, imbalance volumes, renewable forecast errors, and weather variables. Studies such as that of Ma et al. [35] demonstrate that including day-ahead price information substantially improves real-time LMP prediction accuracy, reducing MAPE from 20.02% to 17.29% when forecasts are made after day-ahead clearing. In another example, Deng et al. [15] utilize a rich feature set including de-rated margins, demand forecast errors, and wind/solar errors, contributing to superior short- and medium-term horizon accuracy.

When comparing hybrid versus non-hybrid models, the results clearly favor hybrid architectures, particularly when pre-processing techniques such as wavelet transforms or decomposition-based LSTM encoding are applied. For example, the hybrid CNN+BiLSTM [20] combination yielded robust performance improvements under volatile conditions. Similarly, GRU+LightGBM [29] and GHTnet [33] have shown that post-processing through ensemble blending can significantly reduce residual forecast errors.

Results show that the prediction errors in balancing markets are higher than those in day-ahead markets. Reducing forecast errors in balancing markets under identical forecast horizons remains difficult, a challenge largely attributable to the prevalence of price spikes and ramp events.

As a benchmark, Mean Absolute Percentage Errors (MAPEs) in balancing market price forecasting typically range between the following:

- From 3% to 10% MAPE for forecasts from 1 to 6 h ahead.

- From 10% to 20% MAPE for horizons from 12 to 24 h.

These approach 25% as the horizon extends to 36 h.

5. Alternative Forecast Targets and Auxiliary Variables

As an alternative approach, forecasting related variables such as imbalance volumes (IV) has been explored, given their strong correlation with balancing prices. Accurate prediction of such alternative forecasts can serve as informative proxies, offering valuable signals for understanding and anticipating balancing market behavior. Therefore, several studies focused on predicting imbalance volumes (IV) [32,42,46,49,50,51,60], imbalance direction or classification (IVC) [42,43,49,51,59], the premium or difference between balancing and day-ahead market prices (P) [42,43,49], and load (L) [55] prediction. These auxiliary variables offer valuable early-warning indicators for market participants and system operators, enabling more proactive bidding, hedging, and dispatch decisions. In addition, predicting whether the balancing price will exceed or fall below the day-ahead price (C) may guide directional trading decisions and can be employed for reducing imbalance cost [44]. Moreover, studies addressing spike occurrence prediction (S) [56] contribute to understanding and managing risk exposure in highly volatile market intervals. Table 1 and Table 2 use the following abbreviations: IV: imbalance volume prediction; L: load prediction; IVC: imbalance volume classification (surplus or shortage); C: classification of the sign of the price difference between DAM and BM; S: spike occurrence prediction; and P: balancing market premium prediction (price difference between BM and DAM).

Considering the methods used for forecasting the alternative targets, Imbalance Volume (IV) prediction is addressed using a diverse set of models, including ARIMA [32,50], SARMA [42], ANN [49], LSTM [46,51], BiLSTM [32], PNN [50], and ARMFST3 [60]. Imbalance Volume Classification (IVC), which involves identifying the system state as surplus or shortage, employs methods such as Random Forest (RF) [51,59], Hidden Markov Model (HMM) [49], LightGBM [51,59], MLP [51], PM [43], HM [42], and a newer hybrid RF+ LightGBM+ MLP+ XGBoost method [51]. For Balancing Market Premium (P), models such as ARM and EXO [42], ARX [42,43], and HMM [49] are implemented. For spike occurrence (S) prediction, which targets extreme market events, it has been handled with techniques such as k-NN [56]. Load (L) forecasting [55], another signal correlated with market imbalance, has leveraged RF, RBF, and Fuzzy Logic (FL). Lastly, the classification of the sign of price difference between day-ahead and balancing markets (C) has incorporated a hybrid RF+ SVC+ LoR+ SGB+ XGBoost framework [44]. The methodological diversity observed across these forecasting problems highlights the importance of aligning model structure with the specific characteristics of each target variable, and it underscores the growing reliance on hybrid and deep learning-based approaches in the recent literature.

Predicting the aforementioned auxiliary variables remains a non-trivial task. A Hidden Markov Model (HMM)-based method is described in [49] for the imbalance volume (IV), premium forecasting (P), and state of the balancing market (IVC). The proposed HMM model, which uses a combination of a Markov switching state model, can generate 1 h-ahead and 12–36 h-ahead forecasts. In line with this, Garcia and Kirschen [50] provide a forecasting approach for the net imbalance volume (IV). They consider two forecasting horizons: a month-ahead forecast and a week-ahead forecast. They demonstrate that for monthly forecast, the proposed method accomplishes the 20% error reduction in the forecasted volume. For weekly forecasts, they compare accuracy across working and non-working days, using multi-dimensional ANNs and one-dimensional methods. The results indicate that ANNs outperform the other approaches in all test cases.

Bara and Oprea [51] introduce a hybrid forecasting approach for predicting imbalance volumes (IVs) in the balancing market by first classifying the imbalance sign (IVC). The proposed pipeline begins with imbalance sign prediction, which incorporates an element of uncertainty awareness into the subsequent LSTM-based forecasting process. The results demonstrate significant accuracy improvements when the imbalance sign is included as a predictive feature, reducing MAE from 1.037 to 0.725 and increasing R-squared from 0.939 to 0.982 across the January–August 2022 period.

Alternatively, Dinler [44] proposes a method that combines a LSTM autoencoder with advanced classification algorithms to predict IVC before DAM closure. It generates predictions for a relatively long forecast horizon (18 to 42 h ahead) and utilizes the results to adjust wind power volume bids accordingly. The study also runs correlation analysis on the diverse market data and employs country-specific regulatory formulas. Extensive real-world testing over a one-year period showed that the approach consistently reduced imbalance costs between 6.258% and 11.195% across four wind power plants.

6. Market Scope, Test-Period Design, and Performance Metric Selection

Comprehensive forecasting requires combining data from both market and system operators within a region. Table 3 lists the markets/regions considered in the surveyed studies. Many works use publicly available datasets released by market and transmission system operators. Notably, two studies [19,25], openly release their code along with the dataset.

Thirty-one studies explicitly disclose the length of the test period, covering a total of 33 distinct cases, yet their lengths vary widely. Out of these 33 tests the median test length is 2 months, and only 45% cover at least a full season (≥3 months). Concretely, 18% evaluate < 1 month (e.g., 1 day, 6 days, 20 days, and 3 weeks), another 15% exactly 1 month, 30% 1–3 months, 6% > 3 months but <1 year (e.g., 4–8 months), and 30% ≥ 1 year [17,20,21,25,26,30,31,32,43,44] (including multi-year tests). The analysis also reveals potentially non-representative sampling choices, e.g., market-specific windows within the same study (2 months for ISO-NE vs. 3 months for PJM) [35] and non-holiday subsets (≈2.5 months) [42], which can inflate apparent accuracy if challenging regimes are under-sampled.

For balancing markets, where seasonality (load and wind/RES profiles), scarcity episodes (tight capacity margins and high imbalance volume), and calendar effects shape the distribution, short windows are unlikely to capture regime diversity or tail behavior (spikes). As a result, point-error metrics computed on days-to-weeks or single-month samples risk optimistic generalization and unstable conclusions about model superiority. By contrast, a contiguous year (or multi-season design) is methodologically justified; it spans winter-to-summer shifts, holiday clusters, maintenance/forced-outage patterns, and structural breaks, enabling robust hyperparameter tuning and fair comparison across models.

Recommended practice, therefore, can be to (i) prefer ≥ 1-year out-of-sample evaluation or, at minimum, multi-season blocked/rolling back-tests; (ii) report regime-conditional performance (e.g., normal vs. scarcity/spike days; holiday vs. non-holiday) alongside aggregate errors; and (iii) document inclusion/exclusion criteria (holidays and extreme events) and market splits explicitly. When only short windows are feasible, authors should complement results with rolling-origin tests across disjoint weeks/months and provide uncertainty bands or sensitivity analyses to guard against period-selection bias.

Table 3.

Market/Region.

Table 3.

Market/Region.

| Market | Ref. |

|---|---|

| Ontario (Canada) electricity market NYISO, New York City Irish balancing market (I-SEM) Dutch balancing market Southern Norway (NO1) Polish market UK energy market U.S. PJM market Queensland (Australia) spot market Belgian imbalance market U.S. Midcontinent independent market (MISO) U.S. ISO New England Swedish Nord Pool market New South Wales (Australia) Nord Pool NO2 (Norway) Turkish electricity market Greek balancing market England and Wales market Romanian market ERCOT (Texas, USA) Japanese electricity market Austrian balancing (real-time) market Nordic power market German balancing market | [19] [20,24,27,33] [21,25] [22] [23] [26,43,55] [15,28,37,48,50,61] [29,34,35,36,47] [29] [10,30,32,54,58] [31] [35,38,41] [39,49] [40] [42] [44] [46,57] [52] [51] [56] [59] [60] [62] [17] |

As summarized in Table 4, most studies evaluate forecasts with unit-valued errors such as MAE and RMSE (reported in the native currency per MWh), while a non-trivial subset additionally employs percentage- or scale-free criteria (e.g., MAPE, sMAPE, and NMAE/NRMSE). Unit-valued metrics are indispensable for operational interpretation because they measure error directly in “currency per energy” and thus align with financial impacts, but they hinder comparisons across hours with different price levels or across years and markets with shifting price regimes. Scale-free metrics address this by normalizing error (to a mean, range, or to the magnitude of the observation/forecast), enabling more meaningful cross-period and cross-market benchmarking. However, MAPE suffers from the following two well-known issues in electricity price applications: it is undefined (or numerically unstable) when prices are zero or near zero, and it weights over- and under-estimation asymmetrically. Consistent with the studies listed in Table 4, sMAPE is therefore preferable as a percentage indicator because its symmetric denominator mitigates the zero-price pathology and balances positive/negative deviations. In practice, it could be recommended to report both classes in tandem, MAE/RMSE for monetary interpretability and sMAPE plus NRMSE/NMAE for scale-robust comparison, while documenting the chosen normalization scheme to ensure reproducibility and fair assessment.

Table 4.

Performance metrics.

Table 4.

Performance metrics.

| Metric | Ref. |

|---|---|

| MAE | [15,17,19,21,22,27,28,29,33,34,36,40,42,46,48,50,51,56,57,58] |

| RMSE | [15,17,19,21,22,26,29,31,34,40,46,48,50,51,56,57,58,61] |

| MAPE | [15,20,24,33,34,35,40,41,49,50,51,52,55,56] |

| R-squared | [28,29,46,48,51] |

| Pinball Loss | [30,32,48,57,61] |

| Continuous Ranked Probability Score (CRPS) | [17,30,32,57] |

| sMAPE | [21,27,49] |

| Winkler Score | [32,40] |

| nMAE | [30,57] |

| Model Confidence Set (MCS) | [19] |

| Aggregate Pinball Score | [25] |

| Explained Variance Score | [28] |

| MSE | [28] |

| MRE (Mean Relative Error) | [29] |

| IAE (Integral of Absolute Error) | [29] |

| NRMSE | [30] |

| Pseudo R-squared | [37] |

| MAP (Maximum a Posteriori) | [41] |

| Area Under the Curve (AUC) value | [51] |

| IQR (Interquartile Range) | [55] |

7. Revenue Optimization and Extreme Events

Production and price uncertainties remain persistent challenges for variable renewable energy producers and Virtual Power Plants (VPPs), as highlighted by works such as that by Ramos et al. [65], addressing uncertainty, and Chen et al. [66], examining the limitations of pricing strategies. Quantifying revenue gains and formulating economically viable operational strategies continue to be non-trivial tasks. In balancing price forecasting, market features, such as net imbalance volumes or day-ahead market prices, are often incorporated as exogenous inputs. However, in many cases, when these input values are themselves forecasted within the forecasting methodology, their associated errors can contribute more to error propagation than to accuracy, as reported in [42,44,67].

Nolden et al. [68] highlight the presence of transaction costs in real-world cases and report that, at the current stage of market development, these costs can surpass contractual revenues, posing a critical barrier to the economic viability of flexibility services. They quote that, in the context of the UK market, “it is difficult to create a business case for flexibility because we don’t know how many flexibility events there will be, and we don’t know what the prices will be in a competitive market.” This highlights the broader systemic challenge caused by the absence of intelligent forecasting frameworks, which ultimately limits accuracy. Regulatory price caps are further criticized as distortions that impede efficient price formation and add complexity to data-driven analysis.

7.1. Real-World Constraints

The deployment of balancing price forecasting models faces a pronounced real-world mismatch with back-tests that rely solely on clean, synchronously sampled historical data. Market and regulatory trading constraints (e.g., bid-offer spreads, minimum bid sizes, curtailment limits, limit-up/limit-down caps, and occasional market halts) bound executable strategies, while regulatory interventions can override price formation in extreme events. As mentioned above, transaction costs compound these frictions, eroding returns. Latency further degrades model efficiency; settlement prices, net-imbalance volumes, weather forecasts, and other exogenous features often arrive at different cadences or with multi-hour publication delays, forcing actors either to trade on stale signals or to estimate the missing features. In addition, sudden flexibility events, such as rapid increases or sharp drops in balancing prices caused by unexpected system imbalances, can significantly increase the propagation of forecasting errors over time. These abrupt changes are difficult to predict accurately and can cause the model’s initial errors to grow larger, especially in multi-step or recursive forecasting frameworks. Consequently, benchmark results that ignore asynchronous data arrival, trading frictions, and operational constraints systematically overstate economic performance; rigorous evaluation frameworks must embed these realities to yield actionable, profit-relevant insights for balancing market participants.

Latency, in this context, refers to the delay between when imbalance information becomes available and when operational decisions can actually be taken. Riveros et al. [54] demonstrate that micro-CHP aggregators could reduce weekly system costs by about 5% through near real-time optimization, but this outcome assumes immediate access to Net Regulation Volume (NRV) signals. In practice, imbalance prices and NRV are only published after the 15 min settlement period, which prevents operators from acting instantaneously and substantially reduces the realizable benefit. Smets et al. [58] similarly show, in a Belgian balancing market case study, that although improved forecasting approaches can increase profits for storage systems up to 176%, the perfect-foresight benchmark performs substantially better. This persistent gap arises because operators must rely on forecasts rather than actual imbalance prices. As latency increases, decisions are made further from real time, and consequently, arbitrage profits decline.

Statistical accuracy in price forecasting does not directly translate into financial returns; therefore, a real-time profit-and-loss accounting module is essential. Although most of the electricity price forecasting literature still emphasizes statistical forecast accuracy, a growing but still limited body of research highlights the importance of profit-aware evaluation and explicit risk quantification. For instance, Maciejowska et al. [43] calculate yearly profits and quantify downside risk with the Value at Risk (VaR) metric in the Polish balancing market to benchmark the performance of their statistical models. Riveros et al. [54] explicitly evaluate their CHP rescheduling strategy in the Belgian market in terms of ex post profits. He and Song [53] incorporate probabilistic LMPs and rival strategies into a multi-criteria bidding model where expected payoff, market share, and risk jointly determine optimal bids. Similarly, Li and Park [47] model wind farm bidding in the U.S. PJM market by embedding penalty costs for forecast deviations, ensuring ex post profit maximization.

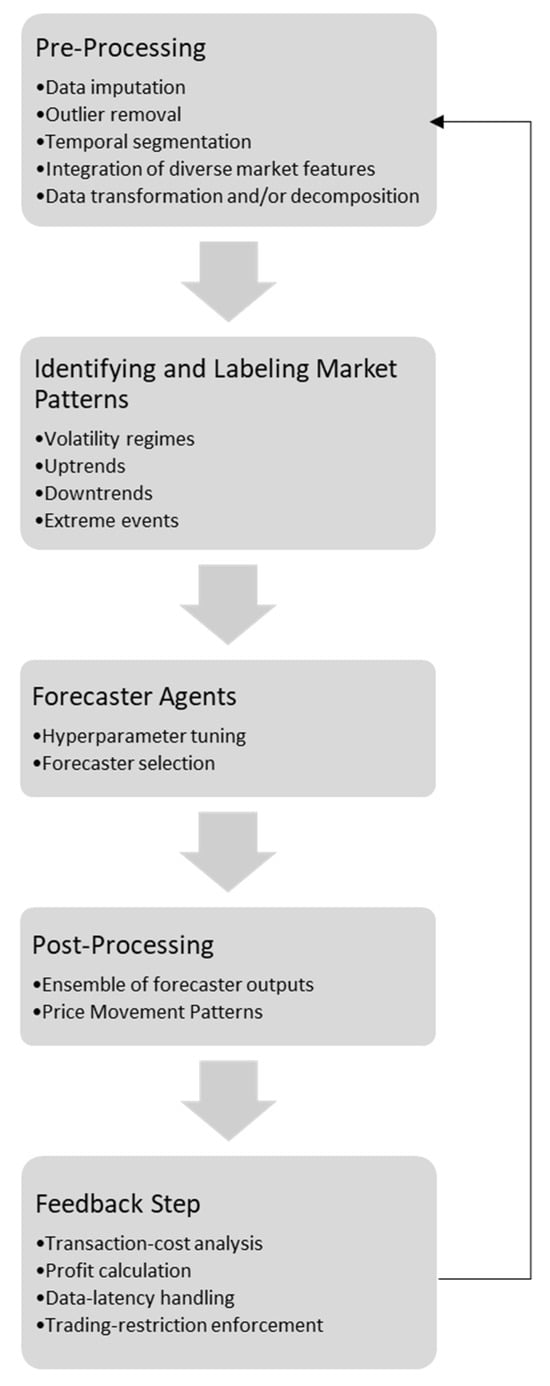

Inspired by this rationale, Figure 2 incorporates an explicit feedback mechanism into the price forecast pipeline. This loop enables the framework to incorporate realized market behaviors and executed trading profits. The following refinements are also provided through this feedback mechanism: (i) refining model hyperparameter tuning; (ii) improving feature selection and dimensionality reduction; (iii) adapting forecasting modules to limit error propagation; (iv) enhancing post-processing ensembling; and (v) dynamically extracting price-movement patterns and regime labels. Collectively, these feedback-driven refinements may ensure that forecasts remain both economically actionable and operationally aligned.

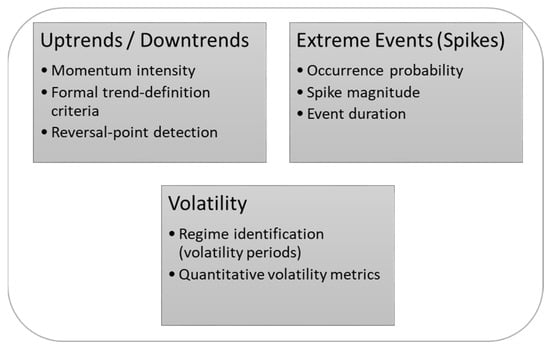

7.2. Identifying Price Movement Patterns

In many current forecasting pipelines, directional trends, volatility regimes, and extreme price spikes are omitted, despite their impact on balancing price dynamics. Explicitly extracting these movement patterns (see Figure 3) can materially improve forecast accuracy. However, directly modeling trends, volatility shifts, and spikes within the core forecaster is fraught with difficulty due to their non-stationary and chaotic nature. Therefore, allocating a pre-processing or post-processing module to identify and label trend phases, volatility regimes, and spike events and subsequently refining and tuning model parameters and prediction algorithms can produce more robust and operationally valuable forecasts.

7.3. Profit-Sensitive Feedback Loop

Neither production nor price forecast accuracy translates directly into economic gain. Adoption of profit-driven (revenue-aware) evaluation is essential in real-world applications, as outlined in [44]. A dynamic revenue (or profit) accounting layer can reflect those, including transaction costs [69], data latency [44], trading constraints [70], and intermittent regulatory interventions [68]. Accordingly, re-injecting realized settlement prices and profit-and-loss figures, net of bid–ask spreads, imbalance fees, curtailment ceilings, and compliance charges, into the workflow may allow the loop to achieve the following:

- Continuously tune pre-processing parameters, tightening outlier filters, or ramp detectors.

- Dynamically re-label market regimes, keeping pattern-recognition components synchronized with prevailing volatility, liquidity, and policy conditions.

- Adaptively re-weight or retrain forecasters, halting model drift and mitigating data latency-driven error.

Figure 2.

Feedback-driven balancing market forecasting framework.

Figure 3.

Characterization of price movement patterns.

Without a profit-sensitive feedback loop, forecast errors may propagate to distort bidding decisions and decouple conventional accuracy metrics from the objectives of maximizing net revenue and minimizing imbalance penalties. Even when nominal forecast errors are low, operational value can be eroded due to factors such as transaction costs [68] and insufficient risk-awareness [67]. In this feedback layer, reinforcement learning approaches [71,72] offer substantial potential for decision-making under uncertainty, as featured in [73], yet they remain underutilized in balancing market price forecasting.

Recent work on the Irish market explicitly incorporates participation and per-MWh transaction fees, and it enforces realistic battery energy storage system constraints (capacity, ramp limits, round-trip efficiency, and state of charge bounds), alongside a non-negative expected profit filter and daily trade caps [25]. However, execution latency/slippage and explicit regulatory price caps are not parameterized, and several asset life-cycle items (e.g., warranty, insurance, end-of-life, and incentives) are excluded.

7.4. Spike and Ramp Event Forecasting

Balancing or real-time markets are often characterized by extreme price spikes and steep ramps, which constitute the primary drivers of imbalance-related expenses. Identifying the frequency, likelihood, and magnitude of such spikes and ramps is crucial, as they carry significant informational value for risk management. Despite their importance, the existing literature on spike and ramp forecasting remains limited.

Although spikes and ramps are not explicitly forecasted, several works have shown that employing more advanced price forecasting models can lead to a reduction in errors associated with such extreme events [17,21,33,56]. Improved predictors are often better at capturing the underlying dynamics and volatility patterns, which results in more accurate forecasts even during periods of sharp price deviations [21,33,44].

A contribution in the domain of spike forecasting is presented by Peng et al. [56], who propose a hybrid deep learning framework explicitly designed to address the challenge of extreme price events (spikes) in the ERCOT market, focusing on the Houston load zone. The framework is built upon the Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) architecture, enhanced by a concatenated fusion strategy and complemented by a KNN-based classification model to assess the likelihood of price spikes (defined as prices exceeding $150/MWh). Although the TFT model is inherently probabilistic (producing quantile outputs), the framework is applied in a deterministic, point-based manner through fusion with predicted spike likelihood and day-ahead prices, yielding single-value forecasts suitable for operational decision-making. However, spike classification alone achieved an accuracy of only ~51%, indicating the need for further refinement.

8. Conclusions

Accurate forecasting of electricity prices in balancing and real-time markets remains one of the most demanding challenges in power-system analytics. Price formation mechanisms in these markets exhibit complex dependencies that extend well beyond the traditional fundamental supply–demand equilibrium [74]. Horizon sensitivity and judicious feature inclusion become critical bottlenecks beyond 12 h lead times, underscoring the need for hybrid models that blend probabilistic reasoning, ensemble post-processing, and real-time feature engineering.

Empirical benchmarks confirm that forecast error escalates with forecasting horizon. Literature surveys show that Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) in balancing and real-time market price forecasts typically ranges from 3 to 10% for 1–6 h horizons, climbs to 10–20% for 12–24 h ahead, and approaches 25% when the horizon extends to 36 h. These values are systematically higher than those for day-ahead markets.

However, despite this critical operational necessity, research on balancing market price formation dynamics, system imbalance volume forecasting, and extreme event prediction remains markedly limited compared to day-ahead and intraday market studies. The scarcity of research is particularly evident in the context of high-magnitude imbalance events, the accurate prediction of which is critical for both transmission system operators and market participants.

Balancing market price forecasting has been relatively underexplored, with the existing literature showing significant methodological and practical gaps, outlined as follows:

Pre-processing and post-processing gaps

- Sophisticated transformation and feature engineering methods are underemployed.

- Post-processing techniques are rarely used, even though they are known to improve forecasts.

Limited adoption of hybrid/ensemble methods

- Although hybrid models and machine learning ensembles consistently outperform single learners, as known in the wind power forecasting domain, they are underexplored.

Neglected auxiliary targets and indicators

- Auxiliary variables (balancing volume, imbalance sign, price premium, spike/ramp likelihood) provide valuable leading signals but are seldom modeled in the pre-processing and/or post-processing stage of the price forecast methodology.

- Incorporating exogenous drivers, such as natural gas prices, fuel mix, cross-border flows, and renewable power forecasts yields accuracy gains.

Underexplored temporal segmentation

- Separating forecasts by critical hours (e.g., ramp periods and scarcity windows) or by calendar context (weekends and holidays) can reduce error and enhance decision relevance but receives little attention.

Spike and ramp prediction deficit

- Only a limited number of studies have developed dedicated models for spike or ramp magnitudes and occurrence likelihood, despite their financial impact.

Revenue-aware evaluation

- Few studies embed real-world transaction costs, latency effects, or revenue feedback loops, yet these elements are crucial for aligning statistical accuracy with economic value.

Closing these gaps will require parallel advances in hybrid forecasting model development and the application of robust pre- and post-processing techniques. The incorporation of additional external inputs, adoption of spike-sensitive algorithms, and use of ensemble strategies are expected to significantly improve the reliability and accuracy of forecasts in highly volatile balancing market operations.

As a future line of work, a spike-aware approach is planned to be implemented for balancing price forecasting, as outlined in the pipeline shown in Figure 2. In this framework, periods of normal behavior and periods with price spikes are distinguished using statistical detection techniques such as z-score thresholds or adaptive interquartile range methods. For each regime, ensemble weights can be optimized separately so that the most effective component models receive greater emphasis when a spike is detected. Forecasting accuracy and robustness can then be evaluated using risk-sensitive metrics, including symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error (sMAPE) and tail-oriented measures such as Value-at-Risk (VaR) and Conditional Value-at-Risk (CVaR), thereby quantifying risk and promoting profit-aware evaluation. During inference, the method would combine the outputs of all base models with regime-specific weights, resulting in a hybrid ensemble where model blending is explicitly conditioned on the predicted spike status. To further diagnose and refine performance from a profit-aware perspective, the following two additional measures may be incorporated: the maximum number of consecutive hours in which forecasting errors exceed 30% or 50%, which highlights persistent failures; and the proportion of forecasts where the absolute percentage error falls below fixed thresholds (e.g., 10% or 15%), which provides an indicator of reliability of the method.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

Author is affiliated with Nordtek Green LLC. The author declares that this relationship did not influence the research process or its outcomes, and no conflict of interest—financial, commercial, or otherwise—exists between the author, the company, and the content of this work.

Abbreviations

| BM | Balancing Market |

| C | Classification of the sign of the price difference between DAM and BM |

| CRPS | Continuous Ranked Probability Score |

| DAM | Day-Ahead Market |

| DERs | Distributed Energy Resources |

| ISO | Independent System Operator |

| ISO-NE | Independent System Operator New England |

| IVC | Imbalance Volume Classification (surplus/shortage) |

| IV | (Net) Imbalance Volume |

| L | Load |

| LMP | Locational Marginal Price |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MAP | Maximum a Posteriori |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| NMAE | Normalized Mean Absolute Error |

| NRMSE | Normalized Root Mean Squared Error |

| NRV | Net Regulation Volume |

| OPF | Optimal Power Flow |

| P | Balancing market premium Prediction (BM-DAM price difference) |

| PICP | Prediction Interval Coverage Probability |

| PINAW | Prediction Interval Normalized Average Width |

| PJM | Pennsylvania–New Jersey–Maryland interconnection |

| RESs | Renewable Energy Sources |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| R-squared | R2 coefficient of determination |

| S | Spike occurrence prediction |

| sMAPE | Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| SOC | State of Charge |

| TSO | Transmission System Operator |

| VPP | Virtual Power Plant |

| VaR | Value-at-Risk |

| CVaR | Conditional Value-at-Risk |

| CWC | Coverage Width Criterion |

References

- Teixeira, R.; Cerveira, A.; Pires, E.J.S.; Baptista, J. Advancing Renewable Energy Forecasting: A Comprehensive Review of Renewable Energy Forecasting Methods. Energies 2024, 17, 3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Botterud, A.; Zhang, K. Optimal Wind Power Uncertainty Intervals for Electricity Market Operation. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2018, 9, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Renewable Capacity Statistics Report. 2025. Available online: https://www.irena.org/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Hirth, L.; Ziegenhagen, I. Balancing power and variable renewables: Three links. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 1035–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, I.; Dinler, A. Current status of wind energy forecasting and a hybrid method for hourly predictions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 123, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.; Bahloul, M.; Prestwich, S.; Visentin, A. A Review of Electricity Price Forecasting Models in the Day-Ahead, Intra-Day, and Balancing Markets. Energies 2025, 18, 3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorji, P.; Lachowicz, S.; Bass, O. Optimization of size and siting of distributed generation in unbalanced distribution systems: A literature review. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 249, 112039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loßner, M.; Böttger, D.; Bruckner, T. Economic assessment of virtual power plants in the German energy market—A scenario-based and model-supported analysis. Energy Econ. 2017, 62, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irigoyen Tineo, A. A Study on the Profitability of Virtual Power Plants and Their Potential for Compensation of Imbalances. Master Thesis, KTH, Stockholm, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata, J.; Vandewalle, J.; D’Haeseleer, W. A comparative study of imbalance reduction strategies for virtual power plant operation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2014, 71, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Z.; Mokryani, G.; Campean, F.; Hu, Y.F. Comprehensive review of VPPs planning, operation and scheduling considering the uncertainties related to renewable energy sources. IET Energy Syst. Integr. 2019, 1, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Harmsen, R.; Crijns-graus, W.; Worrell, E.; Van Den Broek, M. Identifying barriers to large-scale integration of variable renewable electricity into the electricity market: A literature review of market design. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 2181–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno-lorenzo, M.; Moreno, M.Á.; Usaola, J. Analysis of the imbalance price scheme in the Spanish electricity market: A wind power test case. Energy Policy 2013, 62, 1010–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojavan, S.; Zare, K. Risk-based optimal bidding strategy of generation company in day-ahead electricity market using information gap decision theory. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2013, 48, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Inekwe, J.; Smirnov, V.; Wait, A.; Wang, C. Seasonality in deep learning forecasts of electricity imbalance prices. Energy Econ. 2024, 137, 107770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, L.E.; González, J.S.; Manuel, J.; Santos, R.; Manuel, J.; Fernández, R. Optimal bidding of wind farms in electricity markets considering the influence of system deviation. In Proceedings of the IEEE 21st International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM), Lisbon, Portugal, 27–29 May 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narajewski, M. Probabilistic Forecasting of German Electricity Imbalance Prices. Energies 2022, 15, 4976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Jing, Z. Decision-making and cost models of generation company agents for supporting future electricity market mechanism design based on agent-based simulation. Appl. Energy 2025, 391, 125881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsani, B.; Pineau, P.; Charlin, L. Price forecasting in the Ontario electricity market via TriConvGRU hybrid model: Univariate vs. multivariate frameworks. Appl. Energy 2024, 359, 122649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajigholam Saryazdi, A. A Novel Hybrid Deep learning Model for Electricity Price Forecasting. SSRN 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.; Collins, J.; Prestwich, S.; Visentin, A. Electricity Price Forecasting in the Irish Balancing Market. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2024, 54, 101436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves-Ávila, J.P.; Hakvoort, R.A.; Ramos, A. Short-term strategies for Dutch wind power producers to reduce imbalance costs. Energy Policy 2013, 52, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaehnert, S.; Farahmand, H.; Doorman, G.L. Modelling of prices using the volume in the Norwegian regulating power market. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Bucharest PowerTech Innov Ideas Towar Electr Grid Futur, Bucharest, Romania, 28 June–2 July 2009; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; He, D.; Harley, R.; Habetler, T. A Random Forest Method for Real-Time Price Forecasting in New York Electricity Market. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE PES General Meeting|Conference & Exposition, National Harbor, MD, USA, 27–31 July 2014; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, C.; Collins, J.; Prestwich, S.; Visentin, A. Optimising quantile-based trading strategies in electricity arbitrage. Energy AI 2025, 20, 100476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordasiewicz, Ł. Price forecasting in the balancing mechanism. Rynek Energii 2011, 94, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Schell, K.R. QCAE: A quadruple branch CNN autoencoder for real-time electricity price forecasting. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 141, 108092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, A.; Pegios, K.; Kotsakis, E.; Clarke, D. Price forecasting for the balancing energy market using machine-learning regression. Energies 2020, 13, 5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cu, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y. A Time Series Decomposition-Based Interpretable Electricity Price Forecasting Method. Energies 2025, 16, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, J.; Boukas, I.; De Villena, M.M.; Mathieu, S.; Cornelusse, B. Probabilistic Forecasting of Imbalance Prices in the Belgian Context. In Proceedings of the 2019 16th International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM), Ljubljana, Slovenia, 18–20 September 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, L.R.; Nair, A.S.; Ranganathan, P. Short-Term Forecast for Locational Marginal Pricing (LMP) Data Sets. In Proceedings of the 2018 North American Power Symposium (NAPS), Fargo, ND, USA, 9–11 September 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toubeau, J.; Bottieau, J.; Member, S.; Wang, Y. Interpretable Probabilistic Forecasting of Imbalances in Renewable-Dominated Electricity Systems. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2022, 13, 1267–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Schell, K.R. GHTnet: Tri-Branch deep learning network for real-time electricity price forecasting. Energy 2022, 238, 122052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feijoo, F.; Silva, W.; Das, T.K. A computationally efficient electricity price forecasting model for real time energy markets. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 113, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Luh, P.B.; Kasiviswanathan, K.; Ni, E. A neural network-based method for forecasting zonal locational marginal prices. In Proceedings of the IEEE Power Engineering Society General Meeting, Denver, CO, USA, 6–10 June 2004; Volume 1, pp. 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.Y.; Hsiao, C.Y. Locational marginal price forecasting in deregulated electricity markets using artificial intelligence. IEE Proc. Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2002, 149, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagfors, L.I.; Bunn, D.; Kristoffersen, E.; Toftdahl, T. Modeling the UK electricity price distributions using quantile regression. Energy 2016, 102, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, H.; Nakano, K. Application of Gaussian process to locational marginal pricing forecasting. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2014, 36, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brolin, M.O.; Söder, L. Modeling swedish real-time balancing power prices using nonlinear time series models. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE 11th International Conference on Probabilistic Methods Applied to Power Systems, Singapore, 14–17 June 2010; pp. 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmasebifar, R.; Sheikh-El-Eslami, M.K.; Kheirollahi, R. Point and interval forecasting of real-time and day-ahead electricity prices by a novel hybrid approach. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2017, 11, 2173–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Kim, J.; Thomas, R.J.; Tong, L. Forecasting real-time locational marginal price: A state space approach. In Proceedings of the 2013 Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems and Computers, Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 3–6 November 2013; pp. 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klæboe, G.; Eriksrud, A.L.; Fleten, S.E. Benchmarking time series based forecasting models for electricity balancing market prices. Energy Syst. 2015, 6, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]