1. Introduction

The development of fuel cell technology and the growing interest in the use of hydrogen in transportation make the analysis of processes related to its application in fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) increasingly important. Understanding the aspects of energy flow within the powertrain is crucial for further advancement of this technology and for optimizing it for practical applications [

1].

Fuel cell electric vehicles are characterized by a specific approach to energy management, encompassing both the generation of electricity from hydrogen and its storage in a traction battery. Analyzing these aspects is important for both vehicle manufacturers and fleet operators seeking to optimize operating costs, particularly given the limited availability of independent public data on FCEV performance.

It is worth noting that, while fuel cell-powered vehicles have not yet played a significant role in the European automotive market in terms of their share in the overall powertrain structure (less than 3% in 2022), the number of FCEVs is steadily increasing. Across the European Union, over the past decade, the number of vehicles in category M1 (passenger cars) and N1 (light commercial vehicles) has risen nearly twentyfold, reflecting the growing interest in this technology. A similar trend can be observed in Poland, where the hydrogen vehicle sector has been expanding dynamically—between 2021 and 2025, the fleet of such vehicles increased more than fourfold.

Based on the number of newly registered FCEVs, a similar upward trend can be observed for the years 2015–2022, with the exception of 2023. Over the analyzed period, the number of FCEV registrations increased significantly, confirming the development of the hydrogen mobility market in Europe. Despite a noticeable decline in new registrations in 2023 compared to the peak recorded in 2022, the previous years of intensive growth suggest that this drop may be attributable to external factors such as market volatility or supply constraints [

2,

3].

An analysis of the 2023 data shows that the highest number of FCEV registrations was recorded in France (306) and Germany (273), which together accounted for approximately 72% of all new registrations in Europe. Poland, on the other hand, stands out with the highest number of registrations (83) among other European countries that did not exhibit notable activity in this regard, which may reflect the early stage of hydrogen vehicle adoption in these markets. Between 2018 and 2023, the most frequently registered fuel cell vehicle model in Europe was the Toyota Mirai (2702 units), making it the most popular model in the category of vehicles with the analyzed powertrain [

2,

3].

Hydrogen production costs are strongly linked to the applied production technology and can determine the direction of development and implementation of this technology as a propulsion source. The current cost of hydrogen for end-use transport ranges from USD 1.7 to USD 12 per kilogram, depending on the region and hydrogen source [

4].

Hydrogen produced from fossil fuels, such as natural gas and coal, is the cheapest option due to the steam methane reforming (SMR) and coal gasification processes. These methods benefit from high efficiency, large-scale production, and low feedstock costs, resulting in hydrogen prices ranging from USD 1.7 to 6.1 per kilogram for natural gas without CCUS, USD 1.9 to 7.6 per kilogram for natural gas with CCUS, and USD 1.9 to 4.4 per kilogram for coal gasification. However, to achieve hydrogen purity above 99%, as required for transportation and industrial applications, additional purification steps are necessary, such as pressure swing adsorption (PSA). While fossil fuel-derived hydrogen is currently the cheapest, it has significant environmental drawbacks, especially when produced without carbon capture and storage [

2].

By contrast, hydrogen produced through electrolysis, which uses electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen, is considerably more expensive, with costs ranging from USD 3.7 to 12 per kilogram, depending on the energy source. Electrolysis using wind power results in hydrogen prices ranging from USD 3.7 to 12 per kilogram, solar electrolysis from USD 3.8 to 11.6 per kilogram, and nuclear electrolysis from USD 3.7 to 6.5 per kilogram. The primary reason for the higher cost of hydrogen from renewable sources is that electricity price constitutes the dominant component of hydrogen production costs via electrolysis, accounting for 25% to 45% in the case of solar-powered hydrogen [

4].

It should be emphasized that several key factors could significantly reduce the cost of hydrogen produced via electrolysis in the coming years. It is projected that the price of electrolyzers will decrease substantially as production volumes increase and further optimization of their design and technology takes place. In addition, the cost of renewable electricity has dropped considerably over the past decade, with photovoltaic cell prices falling by 80% between 2010 and 2020. Moreover, with natural gas prices declining from their peak of USD 9.385/MMBtu in 2022, renewable hydrogen could become cost-competitive with fossil fuel-based hydrogen by 2030. It is also worth noting that electricity prices of around USD 20/MWh would enable hydrogen production costs as low as USD 1/kg, assuming 70% efficiency and a net lower heating value (LHV). Under such conditions, renewable hydrogen would become a viable alternative to fossil fuel-based hydrogen [

4].

An analysis of maps illustrating the quantitative distribution of public charging and hydrogen refueling stations in EU countries in 2024 reveals significant disparities (

Figure 1). The number of EV charging points far exceeds the number of hydrogen stations. In Poland, 13,400 charging points are available, compared with approximately 190,000 in Germany, France, and the Netherlands. In terms of hydrogen refueling stations, Germany has the highest number (113), while Poland operates 7 stations, indicating that in some countries, FCEV infrastructure is still in the early stages of development [

2,

3,

5,

6]. However, forecasts for 2030 indicate a clear expansion of hydrogen refueling infrastructure. In Germany, the number of stations is expected to increase by 62%, reaching around 300. In Poland, growth of about 85% is projected (40 stations), reflecting the country’s growing commitment to hydrogen mobility [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Semi-fast AC charging stations offer power of up to 50 kW, while DC fast charging stations, allowing batteries to be charged to 80% in about 30 min, offer powers ranging from 50 kW to 350 kW [

11].

Furthermore, as part of the Fit for 55 package introduced by the European Commission in 2021, it was proposed to replace the existing Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Directive (AFID) with a new Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation (AFIR). One of its key requirements is the mandatory deployment of publicly accessible hydrogen refueling stations every 150 km along the core network corridors of the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T), which includes highways, railways, ports, and airports. This regulation is set to be fully implemented by 2030, ensuring a more coherent and accessible hydrogen infrastructure across Europe [

12].

Figure 1.

Comparison of the number of publicly available CNG and hydrogen refueling points in European Union countries in 2024 [

6,

13].

Figure 1.

Comparison of the number of publicly available CNG and hydrogen refueling points in European Union countries in 2024 [

6,

13].

Currently, there are seven hydrogen refueling stations operating in Poland, two of which offer hydrogen refueling exclusively at a pressure of 350 bar, a typical value for hydrogen-powered trucks and buses (

Figure 2) [

14,

15,

16]. The remaining five stations allow refueling at a higher pressure of 700 bar, which is the standard adapted to the needs of fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), particularly passenger cars that require both short refueling times and extended driving range [

17]. These stations are located along key national and international transport corridors that form part of the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T), such as the A1, A2, and A4 highways. Positioning the stations along these routes is of strategic importance for the development of low-emission transport, including the future use of hydrogen in long-haul and heavy-duty transportation.

In recent years, there has been a marked increase in interest in alternative propulsion technologies, including hybrid and electric vehicles, with particular attention given to hydrogen-powered fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs). Advances in hydrogen technology, improvements in energy conversion efficiency, and the decreasing cost of hydrogen production have made fuel cells increasingly competitive compared to conventional energy sources in the automotive sector [

19]. As highlighted in recent studies [

20], the main advantage of FCEVs lies in their ability to combine long driving range with short refueling time, representing a balance between the strengths of internal combustion engine vehicles and battery electric vehicles. Contemporary designs, such as the Toyota Mirai and Hyundai Nexo, employ sophisticated energy management systems that integrate a 100–130 kW fuel cell stack with a 1–2 kWh high-voltage battery, enabling energy recuperation and optimized power distribution between the sources [

21,

22].

Current research focuses mainly on three key areas: energy efficiency, energy management strategies, and the influence of real-world conditions on fuel consumption. Numerous publications [

23,

24] have analyzed Energy Management System (EMS) algorithms responsible for the dynamic power split between the fuel cell and the battery. Traditional rule-based strategies are increasingly being replaced by optimization methods such as dynamic programming, model predictive control (MPC), and reinforcement learning, which can reduce hydrogen consumption by 10–15% without compromising performance. In parallel, hybrid simulation models that combine chassis dynamometer and on-road (Real Driving Conditions—RDC) data are being developed, providing a more realistic assessment of energy losses in individual driving phases.

Comparative analyses have shown that FCEVs demonstrate higher energy efficiency in extra-urban driving cycles, whereas in urban conditions losses are dominated by frequent acceleration and braking events [

25,

26]. Nevertheless, hybridization of the powertrain allows energy recovery of approximately 15–25% under city driving conditions. Operational studies of the Toyota Mirai conducted in various countries revealed that real-world hydrogen consumption ranges between 0.8 and 1.2 kg/100 km, corresponding to an energy demand of roughly 20 kWh/100 km—values comparable to those of mid-size battery electric vehicles [

27,

28]. Differences in measured results largely stem from route profiles and driving behavior, underscoring the need for further standardization of testing methodologies.

Despite the growing number of publications, a clear research gap remains regarding the comprehensive analysis of energy flow within FCEV systems under real driving conditions. Most existing studies rely on simulations or laboratory tests that fail to fully capture the variability of load profiles, road topography, and the effects of ambient temperature on fuel cell efficiency [

29,

30]. Moreover, much of the research in this field remains proprietary, carried out for specific industrial clients and unavailable for independent verification. The studies conducted by the authors of this paper aim to provide more accessible, real-world insights into vehicles available to everyday users. Few existing publications consider the dynamic interactions between the fuel cell and the high-voltage battery, particularly in relation to Eco and Normal driving modes. There is also a lack of data on long-term fuel cell degradation during real-world operation, which limits comprehensive assessments of lifetime energy efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

The current state of knowledge confirms the high efficiency and strong potential of fuel cell vehicles as a key element of the transition toward climate-neutral transport. Nevertheless, further experimental investigations are needed to evaluate real-world energy flow in hybrid FCEV drivetrains across diverse climatic and driving conditions. Such analyses are essential for validating the effectiveness of energy management strategies and identifying opportunities for optimizing hydrogen and electrical energy consumption in everyday vehicle operation.

Recent surveys indicate that the deployment of fuel-cell vehicles and supporting hydrogen refueling infrastructures is gaining momentum globally, but significant regional disparity remains in infrastructure density and vehicle-to-station ratios [

31]. Although the hydrogen vehicle market is still nascent in many countries, analysing the upstream components of fuel-cell and hydrogen-station technologies provides essential context for assessing real driving condition performance of FCEVs [

32]. The integration of fuel cell technologies with the expanding hydrogen production and refueling infrastructure is recognized as a critical pathway for the sustainable advancement of electromobility, underscoring the importance of continued analysis of hydrogen-powered vehicles and their operational ecosystems [

33].

With the growing importance of this research area, recent publication trends show a clear increase in interest in aspects related to fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) and real driving emissions (RDE) testing across various scientific publishers (

Figure 3). Although the number of publications on electric vehicles (EVs) significantly exceeds that for FCEVs, a greater growth rate in scientific studies between 2020 and 2024 was recorded for FCEVs (+27%). This indicates strong engagement from engineering and industrial communities in the development of hydrogen technology, particularly regarding its application in modern powertrain systems. For comparison, Elsevier, which has published a smaller number of articles related to FCEVs, recorded a substantial increase of approximately 83% in this area during the same period. Moreover, Elsevier also reported a significant rise (+78%) in publications focused on real driving emissions (RDE) testing.

By contrast, data presented by the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) reveal a marked decline in publications concerning WLTC and NEDC test procedures (−46%), while studies on RDE testing also decreased, although to a much lesser extent (−16%). This suggests that chassis dynamometer-based tests (WLTP and NEDC) are gradually losing research interest compared to test methods conducted in dynamic and real-world conditions, due to a shift in research priorities toward more realistic vehicle evaluation criteria [

34,

35].

The publication dynamics observed in industry-oriented outlets (SAE) and academic publishers (Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) highlight the multidimensional nature of FCEV research, contributing to the advancement of zero-emission mobility solutions.

The current development of passenger vehicle models indicates two prevailing trends in the availability of zero-emission drivetrains: battery electric vehicles (EVs) and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs). Therefore, a parametric analysis of selected zero-emission vehicle models was conducted, highlighting certain disparities in the relationship between curb weight—which comprises, among others, the mass of the powertrain, body, equipment, and battery pack—and vehicle range in the WLTP mixed cycle (

Figure 3).

Battery electric vehicles (EVs) typically employ high-voltage batteries with capacities ranging from approximately 60 to 100 kWh, the weight of which can reach several hundred kilograms. In contrast, fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), represented here by the Toyota Mirai, use significantly smaller-capacity batteries of only a few kilowatt-hours—around 1.2 kWh in the case of the Toyota Mirai—making the contribution of the battery mass largely negligible. Moreover, the mass of the Mirai’s fuel cell system is only 24 kg, making it several times lighter than a high-voltage battery [

11].

As a result, the curb weight of FCEVs is generally lower than that of EVs, while at the same time offering greater driving range. This advantage of hydrogen-powered vehicles enables a favorable balance between efficiency and performance (

Figure 4) (

Table 1) [

37].

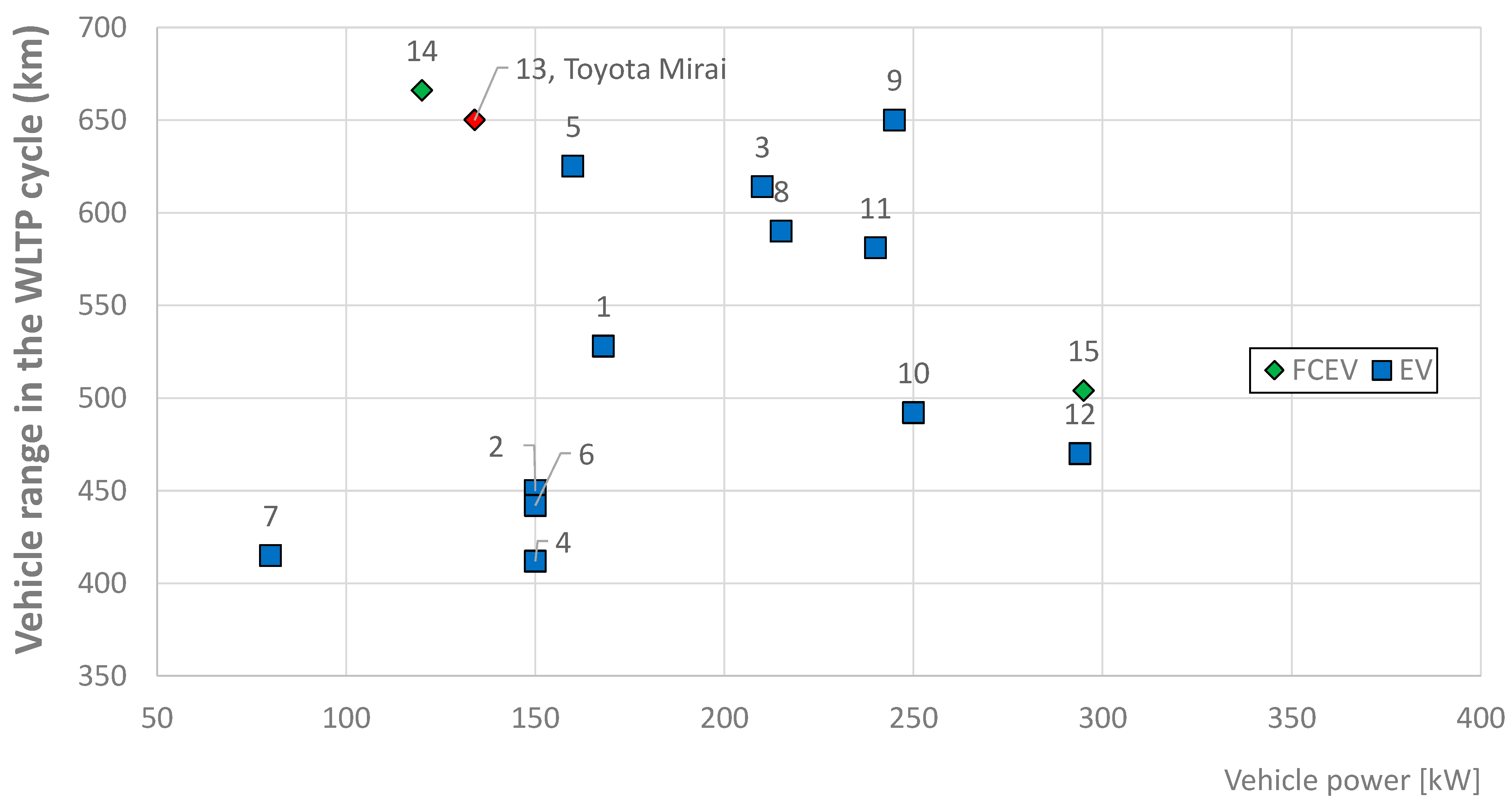

For both battery electric vehicles (EVs) and fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), there is no clear linear relationship between power output and driving range (

Figure 5). EVs tend to exhibit a slight decrease in range as power exceeds approximately 250 kW. However, at lower and medium power levels (150–250 kW), range varies significantly across different models. FCEVs, including the Toyota Mirai, stand out with relatively low output power (around 135 kW) yet a high range (approximately 650 km). This indicates that FCEVs are capable of achieving considerably greater range without the need to increase power. Compared with EVs in a similar power class, the Toyota Mirai achieves a longer range, underscoring the advantage of hydrogen-powered vehicles in terms of energy storage [

38].

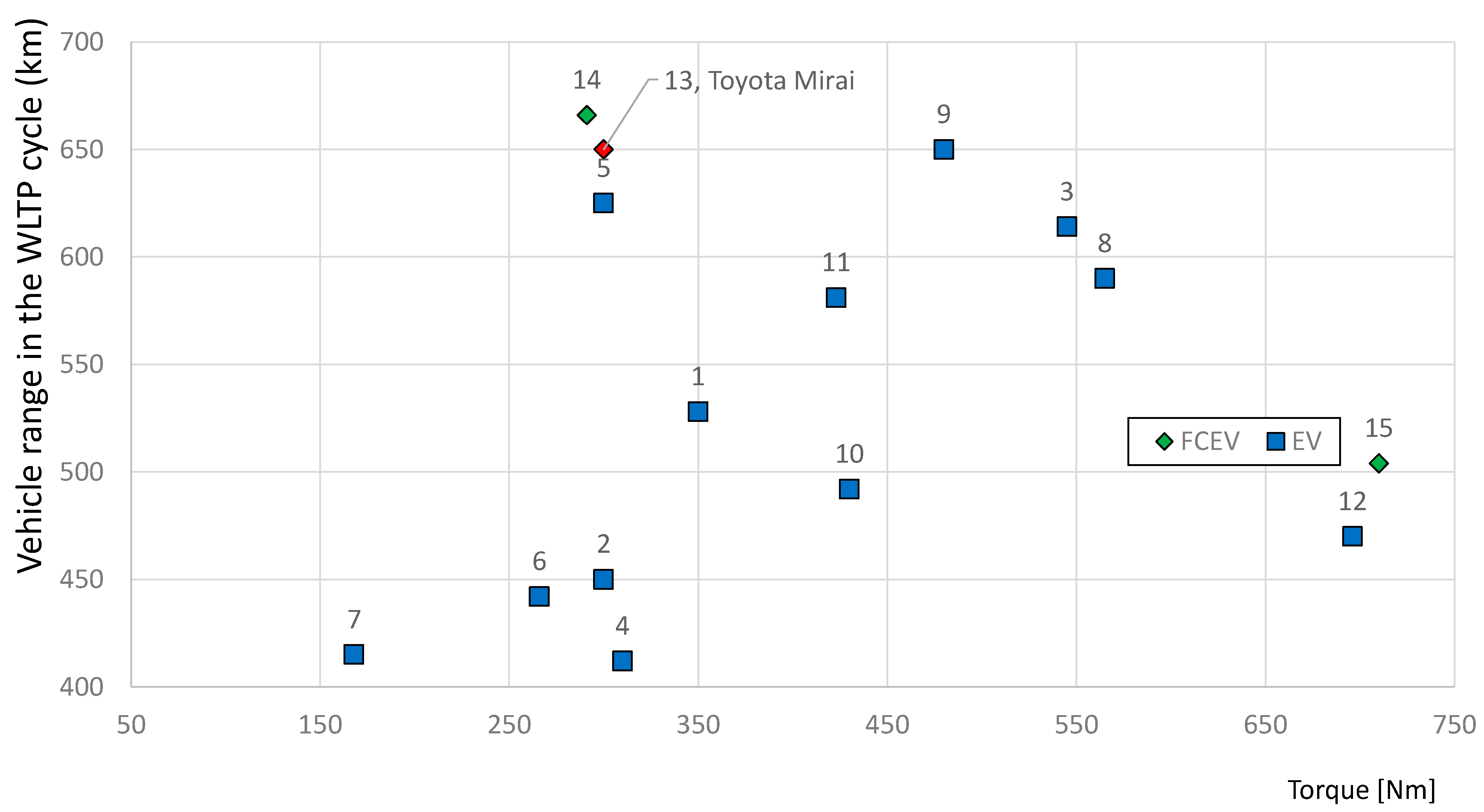

The relationship between torque and range, illustrated in

Figure 6, also shows no clear correlation. Hydrogen vehicles, in addition to having a higher average range than the analyzed EVs, exhibit torque values comparable to certain EVs (around 300 Nm), since in both cases the torque is generated by an electric motor transmitting power to the wheels. Meanwhile, some EVs (Volkswagen ID.7, Mercedes EQS, Jaguar I-PACE EV400) with substantially higher torque (550–600 Nm) achieve noticeably lower ranges.

The presented comparative analysis suggests a tendency whereby increasing power—and consequently torque—in certain EVs may negatively impact driving range, compared with hydrogen vehicles, which demonstrate higher efficiency in energy utilization. This advantage is mainly due to the greater volumetric power density of the fuel cell. As a result, FCEVs achieve longer driving ranges while simultaneously benefiting from lower overall vehicle mass. Considering the representativeness of the vehicles for the study due to availability, a Toyota Mirai vehicle was selected, which will be described in the next chapter.

The structure of this article is as follows.

Section 2—Materials and Methods describes the experimental setup, measurement methodology, and testing conditions applied in accordance with the Real Driving Emissions (RDE) procedure, detailing the parameters monitored during on-road testing of the Toyota Mirai fuel cell vehicle.

Section 3—Results presents the outcomes of the energy-flow analysis, including the operational characteristics of the fuel cell stack, high-voltage battery, and traction motor across the urban, rural, and highway driving phases.

Section 4—Discussion provides a comparative interpretation of the results obtained for the ECO and Normal driving modes, emphasizing the dynamic interaction between the vehicle’s energy sources and its onboard management strategy. Finally,

Section 5—Conclusions summarizes the key findings, highlights the innovative aspects of the study, and outlines future research directions aimed at improving energy management algorithms for hybrid fuel cell–battery systems under real driving conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

The Real Driving Conditions (RDC) testing procedure enables the assessment of energy consumption during actual vehicle operation, in accordance with the requirements of the Real Driving Emissions (RDE) tests. This procedure involves conducting the test over a period of 90–120 min and within an ambient temperature range of −7 °C to 30 °C [

50]. Parameters analyzed during the tests must be measured at a constant sampling frequency of 1.0 Hz, and the cold start period (the time during which the coolant temperature is below 70 °C) must not exceed 5 min. The delay before the start of the drive, defined as the time between the initiation of the test and the vehicle’s movement, must not exceed 15 s, while a single vehicle stop should not last longer than 180 s. The maximum absolute altitude difference during the tests is 1300 m, and the total absolute altitude gain must not exceed 1200 m per 100 km. The vehicle load, including the weight of the vehicle, the driver, and testing equipment, must not exceed 90% of the vehicle’s payload capacity, while auxiliary devices (including air conditioning and heating) should be used as intended during the drive.

The procedure also requires testing under diverse road conditions, divided into three driving phases: urban, rural, and highway. During the test, the vehicle should maintain continuous movement at a speed not exceeding 145 km/h. Exceeding this limit by up to 15 km/h is permissible, but for no more than 3% of the total highway phase duration. Regarding average speeds, the vehicle should maintain below 60 km/h in the urban phase, between 60 km/h and 90 km/h in the rural phase, and above 90 km/h in the highway phase. The time allocation for each phase, based on distance traveled, is 34% for the urban phase, 33% for the rural phase, and 33% for the highway phase [

51].

Research on electric vehicles (EVs) and fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) based on the RDC testing methodology has been conducted by the Institute of Internal Combustion Engines and Drives at Poznan University of Technology [

52,

53,

54] where a characteristic route and test procedure were developed to evaluate the drive system. Consequently, the present study was also carried out in accordance with the RDE (RDC) testing guidelines.

The aim of this study is to examine the electric energy flow in a fuel cell electric vehicle under real-world operating conditions. The results of the analysis may provide insights into the efficiency of hydrogen utilization and potential opportunities for improving energy management in such powertrain systems.

One of the key aspects of analyzing the design of fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) is identifying the energy flow processes, including the operational characteristics of the electric motor. This involves examining the interaction between the fuel cell, the energy storage system (battery), and the electric motor, which together deliver traction power in response to varying energy demands during driving. The characteristics of energy flow in an FCEV depend on various factors such as route topology, traffic conditions, energy management strategy, and vehicle dynamics (acceleration and braking phases), including the use of regenerative systems.

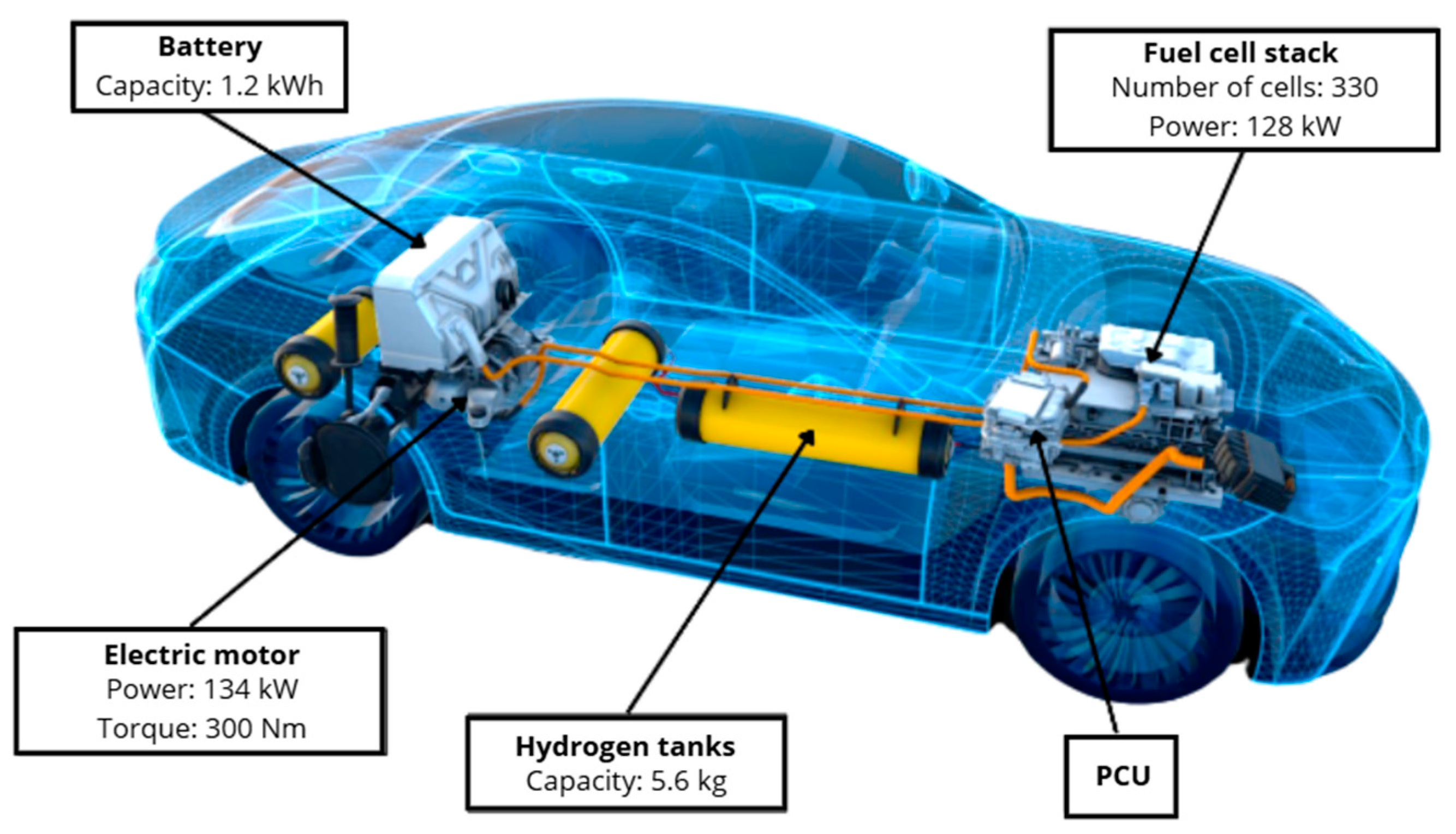

In the second-generation Toyota Mirai tested under real-world driving conditions, it is possible to identify the components responsible for propulsion, as well as for fuel and energy storage (

Figure 7). The powertrain delivers a torque of 300 Nm to the vehicle’s rear axle (RWD—Rear Wheel Drive). The fuel cell, managed by the Power Control Unit (PCU), produces an output power of 128 kW, while the electric motor integrated into the rear axle provides 134 kW. The total capacity of the three hydrogen tanks is 5.6 kg, and the high-voltage battery has a capacity of 1.2 kWh.

The Electronic Control Unit (ECU) is responsible for managing the powertrain system, adapting it to the driver’s needs and the required driving force (

Figure 8). The drive mode selector allows the user to choose between the following driving modes [

12]:

Normal mode—control characteristics adapted to standard driving conditions,

Eco (economy) drive mode—control characteristics that enable reduced fuel consumption by generating torque more smoothly than in NORMAL mode, according to the degree of accelerator pedal depression, while also limiting the performance of the air conditioning system and window heating,

Sport mode—control characteristics adapted for dynamic driving, providing enhanced acceleration through optimized control of the transmission and EV system, as well as increasing steering response.

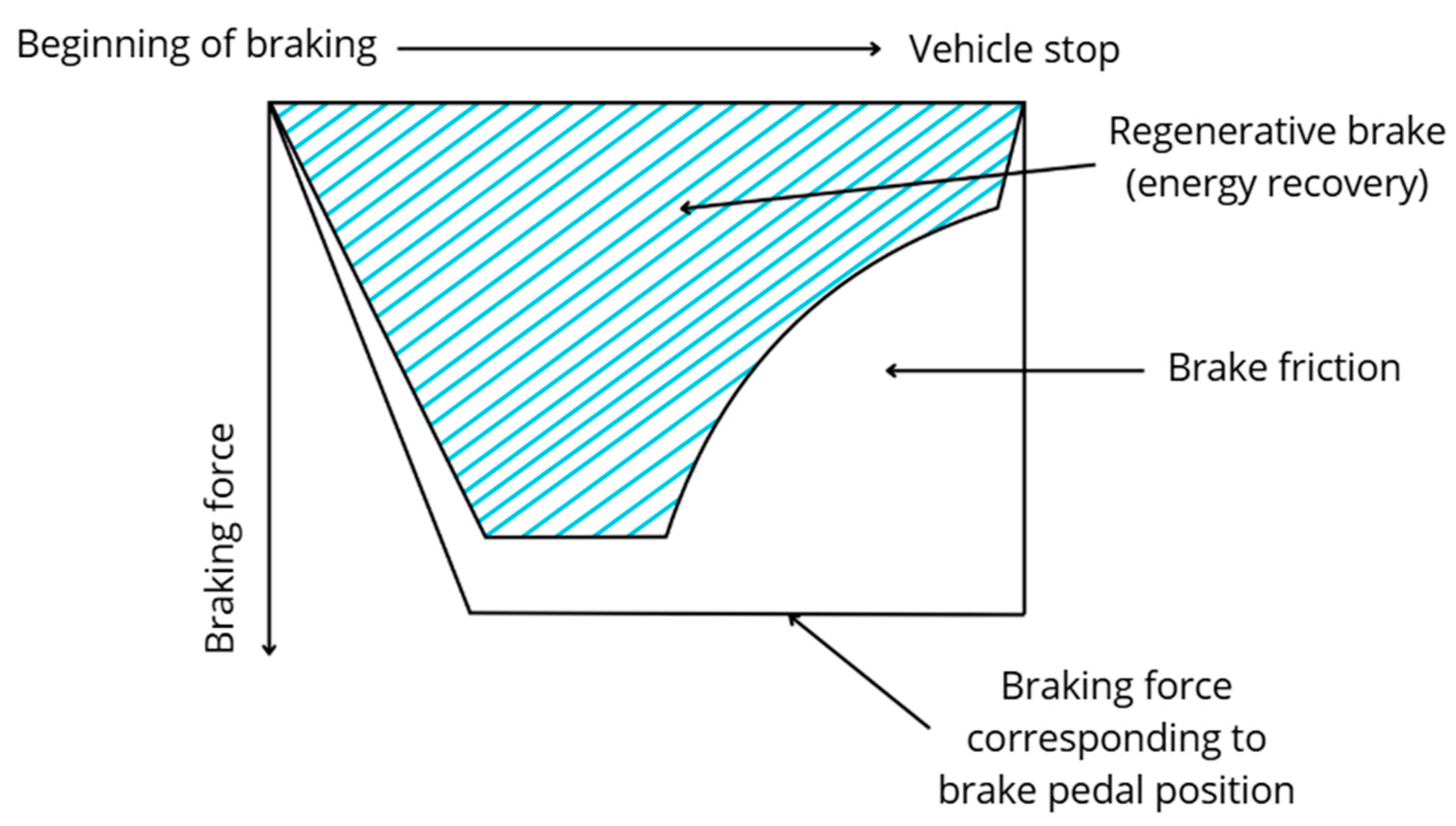

The ECU of the braking control system in the Toyota Mirai detects the degree of brake pedal depression and transmits the calculated value of the regenerative braking force request to the High Voltage (HV) battery ECU (

Figure 9). Based on this requested value, the ECU manages the braking system while simultaneously sending the actual regenerative braking control signal to the Vehicle Stability Control ECU. The electrical energy generated during braking is used to charge the HV battery [

12].

The information provided by the manufacturer, however, remains rather general. Therefore, the research presented in this study offers a diagnostic insight into the interaction of powertrain components. A cognitive assessment of how operating conditions affect the energy consumption of the powertrain may contribute to improving vehicle efficiency.

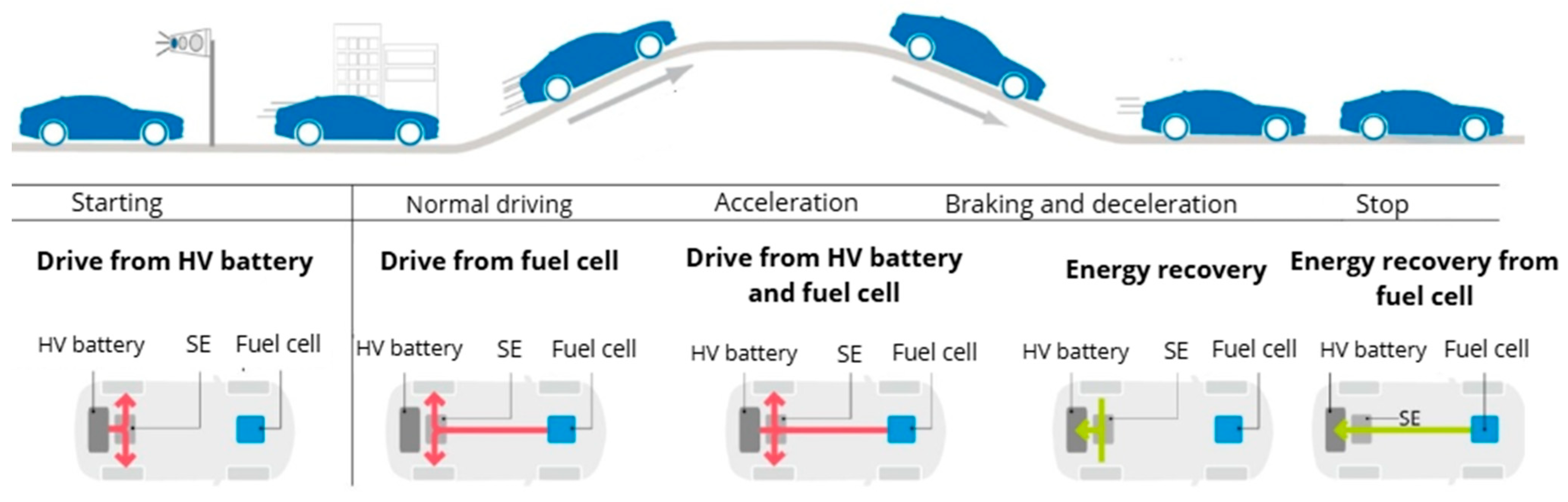

The drive force control system in the tested vehicle actively manages power distribution based on road conditions in order to optimize performance and efficiency (

Figure 10). During take-off, the system draws power exclusively from the high-voltage battery (red color corresponds to energy consumption modes). This allows the electric motor to respond instantly, providing smooth acceleration from a standstill. In this phase, the fuel cells remain inactive while the battery directly powers the motor. During normal driving, the electric motor is powered solely by the fuel cells, whereas during acceleration, the control module coordinates both the fuel cells and the HV battery. The fuel cells provide the base power, while the battery supplements it, delivering an additional power boost to the motor. This dual energy-source configuration ensures strong acceleration when needed, for example, during overtaking or uphill driving.

When braking, the control system initiates energy recovery through regenerative braking (the modes marked in green in

Figure 10 recover or produce energy stored in the battery). Kinetic energy is converted into electrical energy by the motor, which operates as a generator. The recovered energy is then stored in the HV battery. Furthermore, when the battery voltage drops, the control module allows electric energy generated by the fuel cells to be delivered directly to the battery, ensuring that it remains in an optimal state of charge [

56].

The study included tests carried out under real driving conditions (RDC), using dedicated measurement equipment such as a GPS recorder and an OBD (On-Board Diagnostics) data logger (

Figure 10). During the measurements, key parameters related to vehicle performance and energy flow systems were monitored. These included, among others, the state of charge (SOC) of the high-voltage (HV) battery, the voltage and current of the HV battery, the voltage and current of the fuel cell, as well as the torque and rotational speed of the electric motor.

Two measurement sessions were conducted for comparative analysis. In the first test, the vehicle’s powertrain was set to operate in ECO mode, aimed at reducing overall energy consumption. The second test was performed in Normal mode, designed to provide balanced performance. This approach enabled a focused assessment of the impact of different driving modes on the operation of the vehicle’s propulsion system.

During the tests, conducted in the city of Poznań and its surrounding areas, two driving modes of the Toyota Mirai vehicle equipped with a 4 × 2 drivetrain were analyzed. The first drive was performed in Eco mode, while the second was carried out in Normal mode. In both modes, the test vehicle covered a route of 82.85 km, with an average driving time of approximately 107–114 min (

Figure 11). Despite differences in the speed profiles of the individual runs, the average speed in both cases was approximately 45 km/h.

Figure 12 also presents the relative altitude profile of the test route, which ranged from 51 to 134 m. The steepest gradient of the route was located along the highway section, marked in purple.

Measurements were conducted over two working days, on 12 and 16 December 2024. Both measurement sessions took place within the same time window: 11:30–13:20. During the measurement week, ambient temperatures ranged from −3 to 11 °C. However, during the test drives, the air temperature remained stable at 2 °C (Eco mode) and 7 °C (Normal mode). To ensure consistency of measurement conditions, the air conditioning system was set identically for both runs.

3. Results

The measurements were evaluated for compliance with the requirements of the RDE (Real Driving Emissions) testing procedure, which stipulates the execution of three distinct driving phases: urban, rural, and highway. Each of these phases requires covering a specified road section while maintaining speeds within the defined limits. Each measurement session was fully compliant with the RDE testing requirements. The recorded speed profile clearly indicates the division of the driving cycle into three distinct parts (

Figure 13). Both runs, covering a distance of 82.85 km, lasted 107 min (ECO mode) and 114 min (Normal mode), respectively, which is consistent with the required RDE testing standards. Additionally, during the tests the vehicle covered 28.9–33.2 km in urban traffic, 23.5–28.7 km on rural routes, and 25.2–26.1 km on the highway. It is worth noting that in the urban sections the average speed in both cases remained at approximately 24 km/h—within the required range of 15 to 40 km/h—which characterizes both runs as highly comparable.

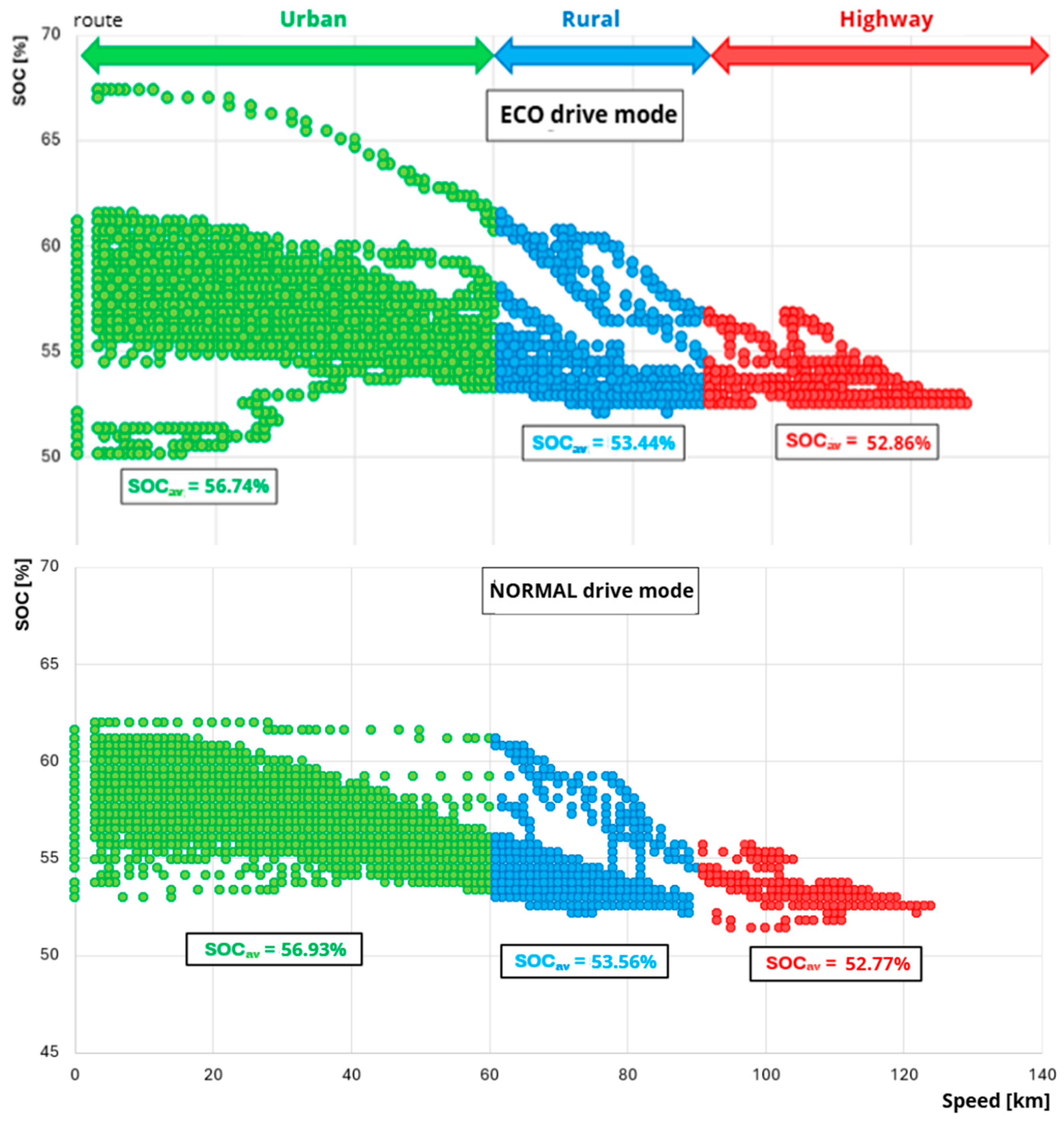

The Toyota Mirai powertrain is equipped with a high-voltage lithium-ion battery that charges and discharges depending on driving conditions such as acceleration and regenerative braking. The recovered energy is reused to power the vehicle, similar to the operation of hybrid and electric cars. The study identified the distribution of the battery’s state of charge (SOC) across each driving phase relative to vehicle speed, taking into account the average values for each phase (

Figure 13).

It can be observed that as vehicle speed increases, the average SOC levels of the high-voltage battery decrease. This is related to the fact that the opportunity for regenerative braking diminishes at higher speeds. Furthermore, the actual SOC also depends on the specific characteristics of the test route, as even a single deceleration event may result in a significant energy recovery. During both test cycles, the SOC remained within a relatively narrow range of 50–67.5%, utilizing only a small fraction of the total HV battery capacity of 1.2 kWh. Limited SOC fluctuations are a typical feature of hybrid systems, where the primary energy source (in this case, the fuel cell) powers the vehicle’s drivetrain, while the battery mainly serves as a buffer for storing surplus energy or energy recovered during braking.

The greatest SOC variations were observed during low-speed driving conditions not exceeding 60 km/h (urban driving). Across the entire test range, the HV battery SOC fluctuated by ∆SOC = 17.26% in ECO mode and ∆SOC = 10.59% in Normal mode. It is noteworthy that despite differences in SOC distribution and initial SOC levels between the two test runs, the average SOC values for the individual driving phases remained very similar (

Figure 14).

The operating characteristics of the powertrain can be divided into energy consumption phases (vehicle acceleration) with positive torque, and energy recovery phases (braking) with negative torque. To illustrate the specific operation of the Toyota Mirai’s powertrain components, the distribution of torque as a function of vehicle speed was analyzed for both driving modes (ECO and Normal).

The study results show that the maximum torque values of the electric motor, which draws energy from both the fuel cell and the HV battery, remain within the range of (−100) to 280 Nm across the entire speed range in Normal mode. In contrast, ECO mode reduces the available torque to approximately 180 Nm. The HV battery charging range resulting from regenerative braking (negative torque) is significantly narrower in ECO mode, where energy recovery is limited mainly to urban driving conditions. In Normal mode, however, the high-voltage battery operates within a broader speed range (0–60 km/h) compared to ECO mode (0–30 km/h). Due to the narrower operating range of the HV battery in ECO mode, the fuel cell operates with greater intensity than in Normal mode, where the battery can supply a larger share of the electric motor’s demand (

Figure 15).

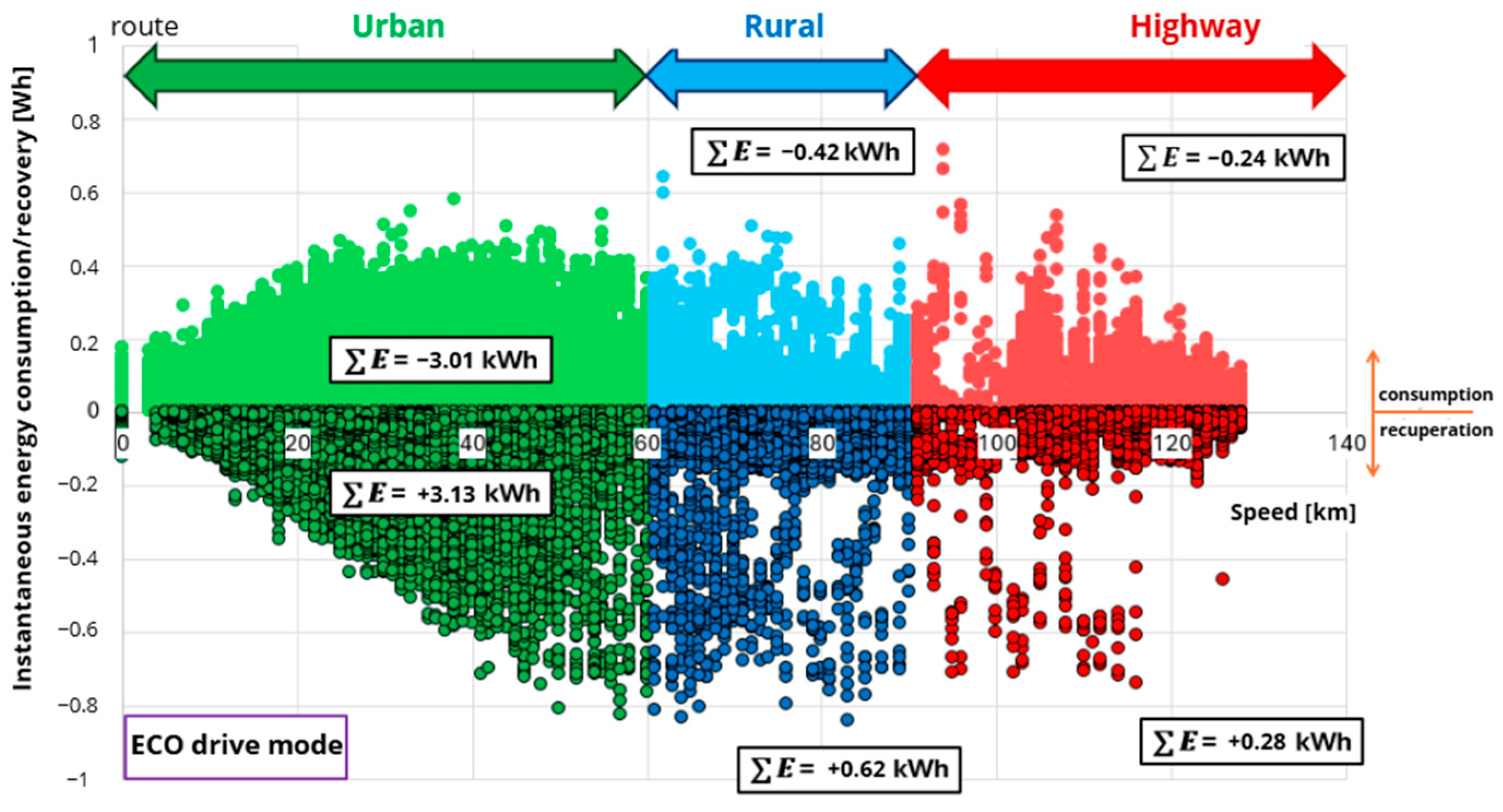

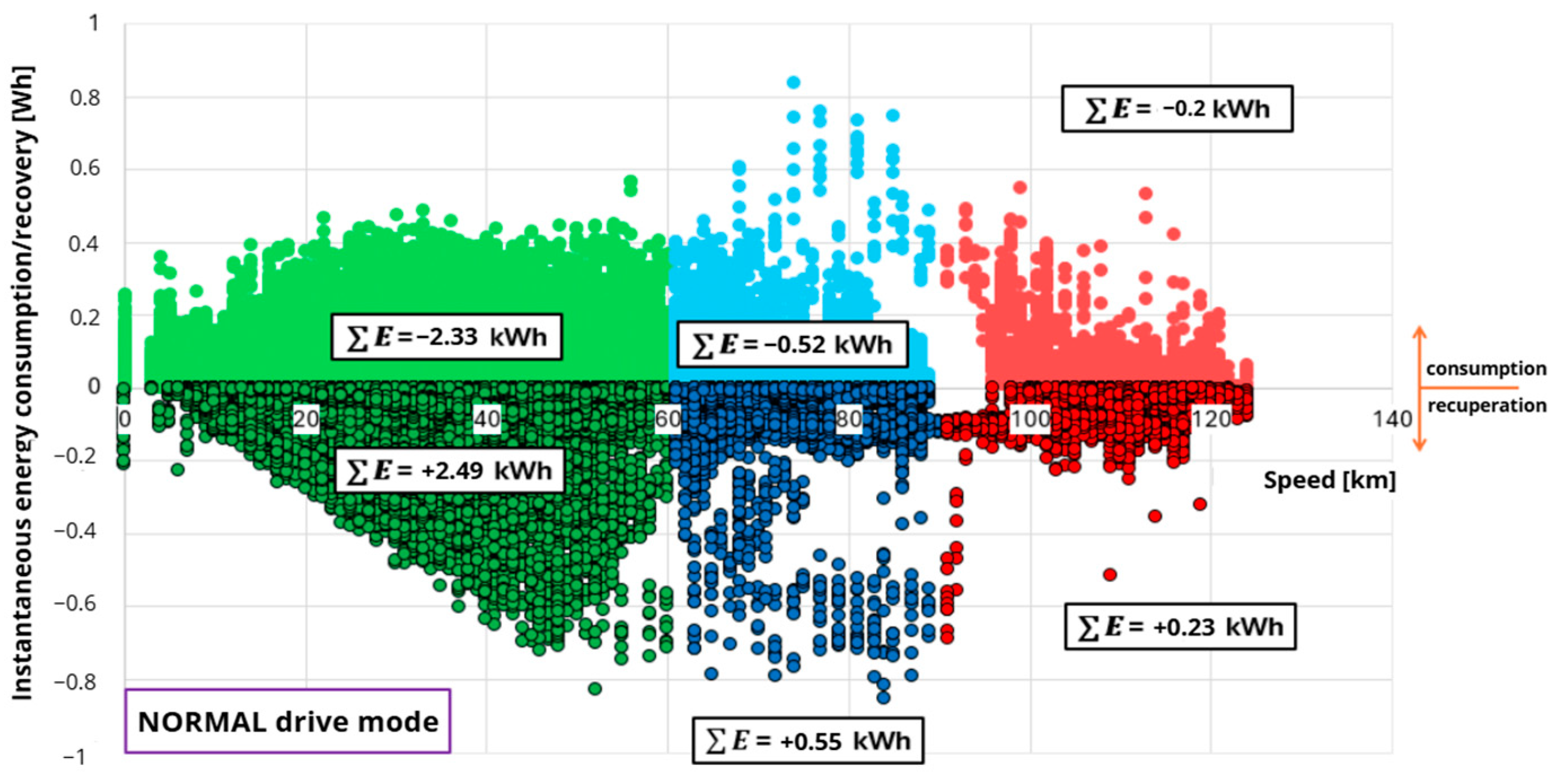

Focusing on the energy flow analysis of the tested vehicle, instantaneous values of energy consumption and recovery recorded during the test runs can be distinguished (

Figure 16). These values, measured with a sampling frequency of 1 Hz, range from −0.8 to 0.8 Wh.

In the case of the fuel cell (

Figure 17), only energy consumption can be identified, used exclusively to power the electric motor driving the rear axle. In both driving modes, the unit values of fuel cell energy consumption range from 0 to 2.5 Wh. For urban driving, cumulative energy consumption is higher in ECO mode, while in rural and highway phases, the total energy demand is slightly higher in Normal mode.

4. Discussion

Based on the obtained results of the energy consumption analysis of the Toyota Mirai and Toyota bZ4X powertrains, it can be concluded that, using both the first and the second calculation method, the average energy consumption in the test—whether considering the fuel cell (Toyota Mirai) and the HV battery (Toyota bZ4X), as well as the consumption of these components (Method I), or the total energy used to power the vehicle (Method II) per 100 km—is higher in the case of the Toyota bZ4X. This is due to the fact that the Toyota bZ4X is a fully electric vehicle (EV), powered exclusively by a high-voltage battery, which may result in higher energy demand compared to the Toyota Mirai, where the primary energy source is a hydrogen-powered fuel cell. Additionally, the greater mass of the Toyota bZ4X (by 160 kg) may also contribute to the higher energy consumption of the powertrain.

The analysis of energy recovery under urban driving conditions showed that the Toyota bZ4X achieves higher values of this parameter (3.1 kWh), which is related to the larger capacity of its HV battery (64.5 kWh) compared to the Toyota Mirai (1.2 kWh). In the Toyota bZ4X, the traction battery plays a fundamental role in powering the vehicle and allows for the accumulation of a significantly greater amount of energy recovered during braking.

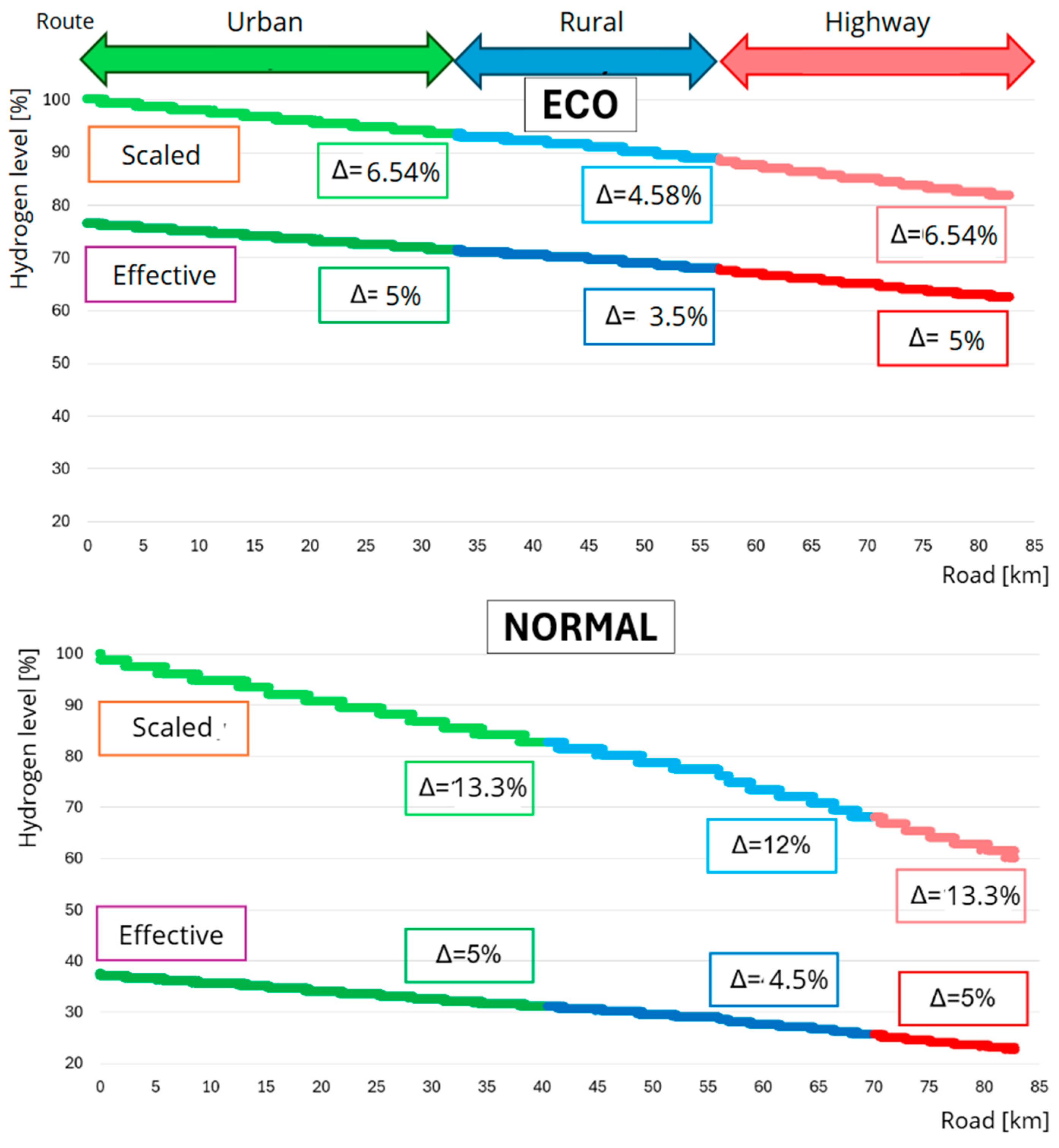

Analyzing the operating characteristics of the hydrogen supply system, a comparison of hydrogen consumption was presented, determined on the basis of observed changes in hydrogen tank levels during road tests (

Figure 18).

Since the initial hydrogen levels in the tanks differed, the presented values were normalized. In both ECO and Normal driving modes, under urban and highway conditions, the actual hydrogen consumption was identical, amounting to 5%. However, when these values are referenced to the normalized levels, it becomes apparent that hydrogen consumption in Normal mode is twice as high as in ECO mode. rural In contrast, in the normalized values, hydrogen consumption in this mode is more than three times higher compared to ECO mode.

The fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV) analyzed in this study, the Toyota Mirai, despite employing a different type of energy supply system, can be compared with the battery electric vehicle (BEV) Toyota bZ4X, which uses a conventional lithium-ion battery as its energy source. The energy intensity of the latter was evaluated in

Figure 17. The comparison of the powertrain systems of both vehicles was carried out using two calculation methods for the Normal driving mode, ensuring consistency of assessment and enabling evaluation of their efficiency in terms of average energy consumption and energy recovery as operational parameters under real driving conditions.

In both Method I and Method II, the energy of individual powertrain components (HV battery/fuel cell) was determined using the following Relation (1):

where

U—voltage of the battery/fuel cell [V];

I—current of the battery/fuel cell [A];

ΔT—current flow time [s].

Method I assumes that the energy consumption and recovery of the HV battery and the fuel cell are expressed as the total energy accumulated during the test for each phase of a single cycle. The energy values presented below refer to the results obtained from the energy intensity tests of the fuel cell electric vehicle (Toyota Mirai) conducted in this study.

The values of energy recovery to the HV battery are specified only for the urban driving phase, since the effectiveness of regenerative braking is greatest under these conditions. HV battery (Toyota Mirai):

Fuel Cell (Toyota Mirai):

The average fuel cell energy consumption for the Toyota Mirai over the entire RDC test, determined based on the results for the individual driving phases, is

Based on the obtained average energy consumption of the fuel cell during the test, it is possible to estimate the energy consumption of this component per 100 km using the following Equation (2):

Knowing the distance traveled and the average fuel cell energy consumption values during each phase of the test, the energy consumption per 100 km was determined:

In Method II, energy consumption is defined as the total energy used to propel the vehicle, calculated as the sum of the energy supplied by the fuel cell and the HV battery, minus the energy recovered through regenerative braking, in accordance with Equation (3):

where

—total energy consumed during the test [kWh];

—fuel cell energy consumption [kWh];

—high-voltage battery energy consumption [kWh];

—energy recovered through regenerative braking [kWh].

This, based on the fuel cell and HV battery energy consumption values for the Toyota Mirai, as well as the recovered energy, the total energy consumption of the tested vehicle in the RDC test was determined.

HV Battery (Toyota Mirai):

Fuel Cell (Toyota Mirai):

Similarly to Method I, using Equation (2), the estimated energy consumption per 100 km of the Toyota Mirai powertrain was obtained:

For the Toyota bZ4X, the total energy used to propel the vehicle during the test is determined in a similar manner as for the Toyota Mirai; however, the contribution of the fuel cell is not considered (4):

Using the above relationship, the total energy used to propel the Toyota bZ4X during the test was calculated:

HV Battery (Toyota bZ4X):

The total energy consumption obtained above for the HV battery of the Toyota bZ4X during the test was converted to energy consumption per 100 km, based on Equation (2):

Based on the obtained results of the powertrain energy consumption for the Toyota Mirai and Toyota bZ4X (

Figure 19), it can be concluded that, using both the first and second calculation methods, the average energy consumption in the test—for the fuel cell (Toyota Mirai) and the HV battery (Toyota bZ4X), as well as the energy consumption of these components (Method I) and the total energy used for vehicle propulsion (Method II) per 100 km—is higher in the case of the Toyota bZ4X. This is due to the fact that the Toyota bZ4X is a battery electric vehicle (EV) powered exclusively by a high-voltage battery, which may result in higher energy demand compared to the Toyota Mirai, where the primary energy source is the hydrogen-powered fuel cell. Additionally, the greater mass of the Toyota bZ4X (by 160 kg) may also contribute to higher powertrain energy consumption. Analysis of energy recovery under urban driving conditions showed that the Toyota bZ4X achieves higher values of this parameter (3.1 kWh), which is related to the larger capacity of its HV battery (64.5 kWh) compared to the Toyota Mirai (1.2 kWh). In the Toyota bZ4X, the traction battery plays a central role in vehicle propulsion and enables the storage of a significantly larger amount of energy recovered during braking.

Based on the conducted research on energy flow analysis for two driving modes (ECO and Normal) in a fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV), a summary of the key operating parameters of the powertrain was obtained and is presented in

Table 2.

Taking into account the parameter values shown in the table, as well as the energy consumption analysis of the powertrain for ECO and Normal driving modes discussed in this work, the following conclusions can be drawn from the study:

The ECO driving mode contributes to an average increase of 63% in ∆SOC across the entire test range. This results from the implementation of an energy recovery maximization strategy in ECO mode, leading to more dynamic high-voltage battery charging cycles compared to the more stable behavior in Normal mode.

The ECO mode shows an average reduction of approximately 51% in maximum torque, which is associated with minimizing energy consumption.

The ECO mode demonstrates an increase in both energy recovery (by an average of 19.8%) through regenerative braking and energy consumption (by an average of 10%) in each of the three driving phases for the high-voltage battery. In urban driving, where regenerative braking is most effective, the energy recovered into the high-voltage battery is 25.7% higher compared to Normal mode.

The ECO mode results in an average increase of 8.5% in fuel cell energy consumption under urban driving conditions (

Figure 20). This is due to the fact that the high-voltage battery operates within a narrow speed range (0–30 km/h), forcing the fuel cell to work more intensively in this range to supply the electric motor. Conversely, in rural and highway driving, energy consumption from the fuel cell is higher in Normal mode.

The ECO driving mode shows an increase in the power generated by the high-voltage battery, averaging 11.44% across the entire test range, and 17% under urban driving conditions, where the difference in cumulative values is most significant (

Figure 21). This is due to the fact that, particularly in urban traffic characterized by frequent stopping and starting, ECO mode is the most efficient. Additionally, the cumulative power generated by the fuel cell is twice as high in Normal mode under urban driving conditions, while across the entire test range, the fuel cell delivers on average 36% more power in Normal mode than in ECO mode.