Abstract

Bioethanol can be efficiently produced from lignocellulosic biomass via two-phase processes, consisting of enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation. To enhance economic and energy efficiency, a system combining separate hydrolysis and fermentation of biomass with a direct-ethanol solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC) is proposed in this work. The system comprises six units: a pretreatment reactor unit, a conditioning unit, a high-solids hydrolysis unit, a seed train unit, an ethanol recovery unit, and an SOFC unit. Exergy analysis based on a thermodynamic model indicates a total exergy efficiency of approximately 0.72. Within the high-solids hydrolysis unit, one piece of equipment exhibits the lowest exergy efficiency of 0.21, at a biomass flux of 71,510 kg/h. The other main exergy destruction exists in the conditioning unit and is followed by seed train unit, accounting for 5.61 and 2.77 of total exergy destruction ratios, respectively. In addition, the tentative parametric analysis for reaction kinetics is performed with varying reaction orders. The results indicate that ammonia gas in a specific unit can follow first- or second-reaction order, whereas acetic acid and sulfuric acid exhibit zero-reaction order, due to the gradual conversion of cellulose to glucose. This work provides key insights for the practical design and operation of the proposed separate hydrolysis and fermentation–SOFC system.

1. Introduction

Bioethanol is considered one of the most promising biofuels due to its low CO2 emissions; consequently, technology routes for its production have been extensively studied through simulations and experiments. Lignocellulosic biomass represents the world’s largest renewable source for bioethanol and is widely available in agricultural residues, forestry waste, and food scraps such as sugarcane bagasse without competing for food resources [1]. Using cellulase enzymes, a separate hydrolysis and fermentation (SHF) route has been developed following the conventional approach: enzymatic hydrolysis is first performed, followed by inoculation with co-fermenting microorganisms [2]. This route remains an active research area because it can potentially enhance enzyme activity and shorten fermentation time [3]. However, the energy efficiency of bioethanol production will inherently limit the potential for renewable energy utilization. Moreover, economic feasibility is not always guaranteed due to uncertainties such as fluctuations in feedstock availability caused by weather variations. These challenges often require excessive optimization of production technology routes, complicating the identification of efficient strategies for further development and full commercialization. A solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC) offers greater accessibility compared with other fuel cell technologies. Their performance can be enhanced by bioethanol-based fuels due to the high energy intensity of hydrogen production, enabling carbon-neutral power generation. Therefore, integrating SHF and an ethanol-fueled SOFC is increasingly necessary to improve the economic and energy efficiency of bioethanol production.

Bioethanol production via biochemical methods represents a promising approach due to its high conversion rate and low energy consumption, independent of fuel shortages [4]. These methods primarily include an anaerobic digestion route and fermentation route [5]. Bioethanol can be derived from sugar-containing biomass through fermentation in the SHF process. After breaking down the biomass structure, the polysaccharides are converted into mono- and disaccharides by enzymatic hydrolysis [1]. In 2018, bioethanol production via fermentation of cellulosic biomass was recognized as the world’s largest bioprocess, with sales exceeding 85 million tons [1].

To evaluate the effects of factors such as feedstock type and bacteria strain on bioethanol productivity, process route designs and parameter optimizations are commonly employed. Process route designs identify the optimal flowsheet that achieves objectives such as minimizing cost or environmental emissions [6]. And then parameter optimizations further quantify economic and environmental trade-offs, supporting more informed decision-making [6].

The interest in bioprocess synthesis and design has historically relied on model-based optimization methods, particularly mathematical programming techniques. Sankoju and Shastri [7] developed a multi-objective mixed-integer linear programming model to maximize farmers’ profits, minimize ethanol costs, and reduce water withdrawals while meeting the lignocellulosic ethanol production targets. Building on similar principles, Liñán et al. [8] designed an integrated scheduling and economic nonlinear model predictive control framework to find optimal decisions among staggered reactors operating simultaneously, economically distributing feed flows through coupled scheduling and control interactions. Similarly, Ramos et al. [9] proposed a comprehensive superstructure-based approach for the optimal design of integrated biorefineries, considering economic, environmental, and social dimensions of sustainability. To address the challenges of large-scale optimization, Pedrozo et al. [10] advanced this line of research by simultaneously optimizing biorefinery structure and the associated heat exchanger network.

Meanwhile, the commercialization of bioethanol is hindered by high costs and uncertainties in the cellulosic biofuel supply chain. Consequently, recent studies have focused on similar process cases under different scenarios [11]. Ge et al. [12] established several cellulosic biofuel conversion pathways based on biochemical reaction dynamics, including SHF, simultaneous saccharification and fermentation, and simultaneous saccharification and co-fermentation. These studies provided important insights into the kinetic characteristics of biochemical conversion processes. Complementing these biochemical perspectives, considerable research has also examined the thermodynamic and thermochemical aspects of bioethanol production, aiming to identify efficiency bottlenecks and potential system-level improvements. In this context, Ortiz et al. [13] performed a detailed exergy analysis to evaluate various pretreatment methods for producing bioethanol from lignocellulosic biomass, thereby offering a quantitative basis for assessing energy utilization.

Throughout lignocellulosic biomass conversion, hydrolysis conditions are a major influencing factor. Pratto et al. [14] highlighted that the main advantage of the SHF route lay in its ability to perform hydrolysis and fermentation sequentially under their respective optimal operating conditions. Hence, they analyzed key input variables including enzyme dosage and biomass loading to determine multi-criteria optimal decisions. Extending this framework, Benalcázar et al. [15] identified critical parameters that simultaneously reduced ethanol production costs and greenhouse gas emissions, thus bridging process optimization with sustainability goals. To address inherent uncertainties in feedstock composition and kinetic parameters affecting enzymatic hydrolysis, Fenila et al. [16] identified optimal operating decisions through solving optimization problems with both deterministic and stochastic parameters. Building on this, Li et al. [17] developed a mixed multi-stage stochastic programming model using a hybrid scenario tree to capture fluctuations in product demand and yield, while Jabbarzadeh et al. [18] proposed a robust stochastic possibilistic mixed-integer programming model for optimal decisions for supply chain design and planning in bioethanol production under uncertainty.

The above process route designs and parameter optimizations of the bioprocess serve as key enablers for integrating multiple processing technologies and identifying potential pathways based on various criteria. Although these optimizations can yield significant cost reductions, the economic feasibility of bioethanol production from lignocellulosic feed stocks remains a major challenge [19]. Moreover, trade-offs between system economics and robustness for decision makers with different risk attitudes should be provided [20]. Therefore, it is necessary to search for and explore simple, low-cost alternatives, particularly for combined systems that account for both upstream and downstream operational efficiency.

Recently, significant interest has focused on combined systems comprising a biomass gasifier and an SOFC, which operate at similarly high temperatures, particularly from thermodynamic and thermochemical perspectives. To emphasize differences in energy efficiency and overall system performance, Petersen et al. [21] compared a high-pressure combined heat and power system with a low-pressure utility boilers system integrated with gas engines fueled by biogas. Following process integration efforts, Alherbawi et al. [22] developed a hybrid biorefinery process capable of producing jet biofuel from multiple biomass feedstocks and further assessed its economics potential and environmental lifecycle performance. Extending to power generation and liquid hydrogen production, Asadabadi et al. [23] introduced a novel biomass-based system including an SOFC and conducted a comprehensive 4E analysis. Further advancing in this direction, Wang et al. [24] performed a detailed parametric study to examine the influence of operating variables on the performance of a biomass gasification-based SOFC, particularly in terms of power output, exergy efficiency, and environmental indices. Beyond system efficiency, the integration of bioenergy utilization with CO2 capture technologies has also received substantial attention [25,26]. In this context, Wang et al. [27] investigated a direct power generation system combining biomass gasification and an SOFC using a water–gas shift membrane reactor–burner to convert syngas while enabling low-cost CO2 separation for economic carbon capture. The results were extended to compare with the conventional biomass-based power systems and showed that the biomass gasification-based SOFC power system achieved favorable thermodynamic performance [4,28].

Although the systems integrating biomass gasification with an SOFC achieve clean and efficient energy conversion, regulatory issues remain that limit yield and optimal operation [25]. Moreover, direct comparisons between bioethanol production via gasification–fermentation and hydrolysis fermentation reveal that the latter offers a lower selling price, mainly due to the higher capital costs of the former [21]. However, no previous study has investigated the direct integration of the SHF process with an ethanol-fueled SOFC, and studies related to the reaction kinetics and thermodynamic of such combined systems remain limited. Several works only explored the thermodynamic and process optimization of SHF-based bioethanol production, and others examined the efficient utilization of bioethanol in SOFC systems.

Therefore, in this paper, the objectives are shown as follows:

- (1)

- The conceptualization of a system combining SHF with direct-ethanol SOFC is devised.

- (2)

- The combined system’s performance is evaluated using thermodynamic methods in terms of exergy destruction and exergy efficiency, revealing matching characteristics and overall system efficiency. And the exergy values of streams in the proposed system and equipment are calculated.

- (3)

- Detailed investigation of the activation energy and thermodynamic parameters to assess the effects of reaction time and temperature on the conversion of xylose to ethanol is introduced through developing the typical reaction kinetic models [29].

The investigation can provide a theoretical basis for system designers and operators and a comprehensive understanding of cost-effectiveness and fuel flexibility for the combined system [10]. This work therefore fills an evident research gap by establishing the first comprehensive thermodynamic and reaction-kinetic assessment of such integration, offering new insights into the potential of coupling bioethanol production with SOFC technology for enhanced renewable energy utilization.

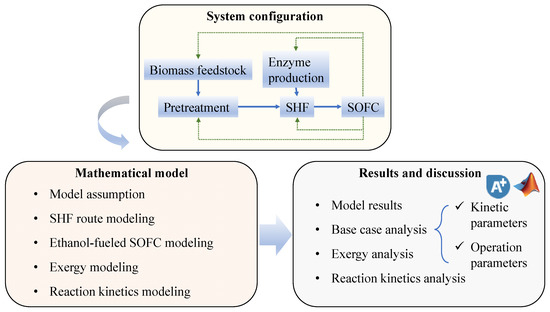

The remainder of this paper is structured as shown in Figure 1. Firstly, the system description for this study is introduced in Section 2.1. Section 2.2 presents the main mathematical models of the proposed system. The results and discussions are presented in Section 3, including the exergy and parametric analyses. Finally, Section 4 presents the conclusions.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the analysis procedure used in this paper.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Design

2.1.1. System Description

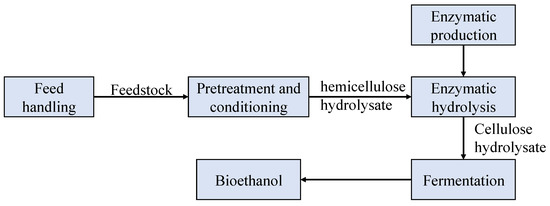

Figure 2 illustrates the schematic diagram and underlying operating principle of the SHF route. A mixture of biomass feedstock, water, and sulfuric acid is fed into the Pretreatment Hydrolysis Reactor, where most hemicellulose carbohydrates are converted into soluble sugars [2]. In this step, the biomass is initially pretreated to obtain a hemicellulose hydrolysate and a solid residue primarily composed of cellulose. The cellulose-rich residue is then subjected to enzymatic hydrolysis through mixing with cellulase, yielding a cellulose hydrolysate. Both hydrolysates are then co-fermented with fermentative microorganisms in a bioreactor, followed by ethanol recovery through distillation.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the SHF system.

2.1.2. System Integration Scheme

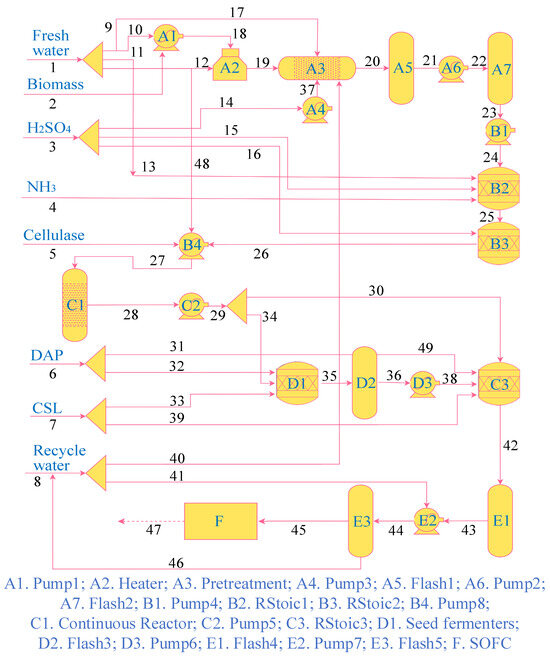

Considering the highly energy-intensive nature of hydrogen production, the direct-ethanol SOFC, supplied by ethanol through the above route, is expected to enable efficient and carbon-neutral power generation. As depicted in Figure 3, the integrated process ensures bioethanol production efficiency by combining sequential fractionation of lignocellulosic components with simultaneous saccharification and co-fermentation [2]. The proposed system comprises a pretreatment reactor unit, a conditioning unit, a high-solids hydrolysis unit, a seed train unit, an ethanol recovery unit, and an SOFC unit [2]. The pretreatment reactor unit includes pumps and a furnace for steam-heating and potential acid impregnation of the biomass, followed by a horizontal stirred bed reactor for operating at a higher pressure and fairly severe conditions of up to 158 °C, later followed by two flash tanks (Flash 1 and Flash 2). The pretreatment products are sent to the conditioning unit, where a stoichiometric reactor (RStoic 1) is employed to ensure the miscibility of the hydrolyzed biomass suspension. Ammonia gas mixed with water is introduced to adjust the pH of the suspension. The high-solids hydrolysis unit is employed to perform enzymatic saccharification of the cellulosic biomass in a continuous high-solids reactor. Such saccharification alters the flow characteristics of the lignocellulosic matrix, allowing the cellulosic biomass pump to supply multiple bioreactors (RStoic 3) [2]. After enzymatic hydrolysis, a portion of the saccharified slurry is diverted for production seeding. Several reactions and conversions are studied in the seed fermenter to assess microorganism growth and sugar metabolism. The seed train unit converts most incoming sugars to ethanol, which is then fed to the production fermenters and recovered. Pure ethanol vapor is cooled by heat exchange with the regeneration condensate and finally condensed with cooling water and pumped to storage [2]. The ethanol removes water from the adsorbent, after which the mixture is condensed and returned to the rectification column (Flash 5). The bioethanol is then fed into the SOFC as fuel for power generation.

Figure 3.

Detailed configuration of the proposed system.

The application scenario of the proposed system targets regions with locally available lignocellulosic biomass and relatively concentrated energy demand. Such conditions are typical of small industrial parks, agricultural processing zones, or centralized island systems, where long-distance energy transport is either economically or technically impractical. In these settings, the proposed system can utilize local crop residues to generate both electricity and bioethanol, thereby improving energy security and reducing dependence on costly fossil fuel imports. Overall, the integrated system design enables efficient resource utilization, supports local energy self-sufficiency, and improves sustainability across the energy supply chain.

2.2. System Modeling

2.2.1. The Assumptions

The proposed system combining SHF with SOFC is introduced and developed in Aspen Plus V14 and Matlab R2024a using steady-state models [4,30]. The following assumptions are made to facilitate the system modeling.

- (1)

- All gases are assumed to behave ideally [4,30].

- (2)

- The entire process is isothermal, and there are no heat and pressure losses [4,30].

- (3)

- Heat losses from equipment to the environment are neglected [25].

- (4)

- Arabinan, mannan, and galactan are assumed to have the same reactions and conversions as xylan [2].

- (5)

- The treated water is assumed to be clean and fully reusable [2].

It is assumed that the proposed system has ideal gas behavior for all gas-phase species. Under the operating conditions considered in this study (up to 750 °C and 7.07 bar), both CO2 and H2O exist as superheated gases, and their compressibility factors are close to unity. Hence, deviations from ideal gas behavior are expected to be minimal.

2.2.2. SHF Route

Biomass hydrolysis is a process in which the saccharification of lignocellulosic biomass, mainly composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, occurs under specific temperatures and catalysts. This process breaks down cellulose and hemicellulose into monosaccharides. The primary objective is to subsequently convert these monosaccharides into products such as fuel ethanol through chemical and biochemical processing. Common catalysts include mineral acids and cellulase. Hydrolysis catalyzed by acid is termed acid hydrolysis, which includes dilute acid hydrolysis and concentrated acid hydrolysis, whereas hydrolysis using cellulase is termed enzymatic hydrolysis [2]. The hydrolysis reaction equations are as follows.

Several mathematical models have been developed to model the formation of key products during the SHF route [31]. The Gompertz model is one of the most frequently applied approaches for characterizing bioethanol production, as it reflects the relationship between bioethanol concentration and the lag phase of fermentation [31]. To streamline the analysis, both bioethanol productivity and glucose utilization are considered in this study. The productivity of bioethanol relative to the amount of sugar consumed is expressed as follows [31].

The glucose utilization, as well as the conversion of glucose, is defined as follows [31]:

where icglucose is the initial glucose molar concentration. fcglucose is the final glucose molar concentration.

2.2.3. Direct-Ethanol SOFC

The direct utilization of liquid biofuels in SOFCs refers to feeding them directly into the anodes for electricity generation. This offers improved stability and cleaner operation for power production, benefiting from the reduced likelihood of carbon deposition [32]. Because of its high volumetric lower heating value and non-toxic nature, bioethanol has become the most extensively studied liquid biofuel for direct SOFC applications, which typically operate within a relatively low temperature range [32]. Thus, when bioethanol undergoes complete electrochemical oxidation, the corresponding anode reaction can be expressed as follows [32].

Accordingly, the cathodic reaction, in which oxygen is served as the oxidant, can be represented as follows [32].

The principal chemical reactions considered in the direct-ethanol SOFC model are presented below [32].

Based on the Nernst equation, the open-circuit potential between the anode and cathode for these reactions can be determined as follows [32].

where F is the Faraday constant. RC is the ideal gas constant. TSOFC is the operating temperature of SOFC [4]. p denotes the partial pressure of C2H5OH, H2O, and CO2 at anode and O2 at cathode. E0 is the standard potential, which depends on the Gibbs free energy change in the reaction, and is expressed as follows [32]:

where represents the difference in molar Gibbs free energy between the products and reactants of the electrochemical reaction under the given temperature and pressure conditions [4]. The standard potential E0, derived from , varies with temperature, and its value differs depending on the specific electrochemical oxidation process. And the type of fuel involves at each temperature, such as 550 °C, is selected, and the corresponding E0 is 1.17 V [32]. Although this theoretical voltage of a direct-ethanol SOFC is lower than that of other SOFC types, it exhibits higher specific energy and higher reversible energy efficiency [32].

The current density of the direct-ethanol SOFC is calculated by the following relation [25]:

where z is the molar amount of bioethanol. n denotes the number of electrons transferred for each oxygen atom involved in this electrochemical reaction. N is the number of SOFCs, which is defined as 10,000. A is the cell area, which refers to the literature [25].

2.2.4. Exergy Analysis

According to the second law of thermodynamics, when macroscopic kinetic and potential energies are neglected, the exergy of a mixture consists of physical and chemical exergy, defined as follows [33,34].

where EXche presents chemical exergy. EXphy denotes the physical exergy and is calculated as follows [33,34]:

where is inlet molar flux. T is the temperature. h and s are the specific enthalpy and entropy, respectively. And subscript 0 stands for the environmental reference state [33,34].

The physical exergy of biomass is typically negligible; thus, its total exergy can be defined by its chemical exergy as follows [33,34]:

where m is the mass flow rate. represents the lower heating value. is the multiplication factor, which is calculated as follows [33,34]:

where , , , and denote the mass fraction of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen in the biomass, respectively. The specific chemical exergy of each component is obtained from the literature [35].

In addition, under steady-state conditions, the exergy balance is applied to evaluate the system’s performance through the degree of exergy destruction, which serves as a useful indicator for optimizing the thermodynamic efficiency of the system or a specific piece of equipment, described as follows [33,34]:

where EXI and EXO denote the input and the output exergy of the system or the equipment, respectively, while EXD represents the corresponding exergy destruction.

Given that the quality of energy associated with the proposed system’s inputs and outputs differs, both the exergy efficiency and the exergy destruction ratio are adopted as criteria for assessing the system thermodynamic performance, which are defined as follows:

The exergy balances of all equipment in the proposed system are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Exergy balances of all equipment in the proposed system.

2.2.5. Development of Reaction Kinetics

The main limitation in producing bioethanol from lignocellulosic biomass is the energy-intensive nature of the process, which can be mitigated through the thermodynamics analysis described above. However, several key aspects of the chemical reactions, particularly the effects of reaction time and temperature, remain insufficiently understood. In particular, the detailed mechanisms governing cellulose hydrolysis by cellulases throughout the reaction are not yet fully established. Because no single mechanism-based model exists, it remains challenging to perform rational reaction engineering to optimize reactor performance or improve process design. To address this gap, this study adopts a parameter-based approach to evaluate the overall kinetics of the proposed integrated system.

The reaction rates in this study are expressed using a power law model, where the aforementioned reactions are treated as homogeneous catalytic processes, as shown below [29]:

where r is the reaction rate, and c is concentration of reactants at time t. k is reaction rate constant. and denote the reaction orders of respective reactants, while the conversion of reactant A is also defined as its concentration change relative to the initial value [29]. Also, c can be further simplified through the initial molar ratio of reactant A to B. Thus, the reaction rate of reactant A is concluded as follows [29]:

where is the initial molar ratio of reactant A to B.

Based on the literature, eight possible combinations of reaction orders are examined to investigate the reaction kinetics [29]. By integrating Equation (17) for each combination, eight corresponding reaction kinetic models are obtained. These models are then linearized to allow graphical determination of the reaction rate constant, denoted as follows [29]:

The above combinations of reaction orders are employed to examine the sensitivity of the proposed system to kinetic assumptions. Each combination represents different rate-controlling operating conditions. Higher corresponds to fuel-concentration-controlled behavior, while higher denotes diffusion- or oxidant-controlled reactions. These variations directly alter the predicted fuel conversion, reaction heat release, and internal temperature distribution. For instance, when = 1 and = 0, the reaction rate responds linearly to fuel concentration and yields stable thermal behavior, whereas = 2 and = 1 produce a sharper temperature rise, indicating potential localized generation. Such comparisons provide physical insight into how the assumed kinetics governs system performance and helps identify appropriate control strategies during future system operation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. System Performance Calculation and Parameters Settings

To examine the thermodynamic behavior, reaction kinetics, and parameter influences of the proposed system, the input conditions for calculation and analysis primarily include the system integration scheme, the characteristics of the lignocellulosic biomass, and key operating parameters [33,34]. The reaction kinetics and the thermodynamic performance, specifically the exergy destruction and exergy efficiency of the equipment, are then calculated, followed by a systematic evaluation of the effects of different reaction order combinations on system performance.

The type and composition of the feedstock introduce considerable influence on both system design and overall economic feasibility. In particular, feedstock characteristics may influence the major components within the bioconversion processes. Moreover, from the perspective of potential sugar, the variations in feedstock composition directly affect the achievable bioethanol yield. In this study, the milled corn stover is selected as the feedstock, referring to the literature [2], as it is one of the most abundant agricultural residues and can therefore be readily sourced. The average dry weight percentages of its principal components in the milled corn stover are given by the literature, summarized in Table S1 [2]. The molecular formulas of the compounds are taken from References [2,36], in which the majority can be found in the native aspen component and the minority is replaced by the component with very close performance; for example, acetate is described by the native aspen component acetic acid [2]. The remaining components are taken directly from other studies, for instance, protein represented by wheat gliadin [37]. The mass flow rate of the feedstock entering the system is 71,510 kg/h. In the high-solids hydrolysis unit, the pretreated hydrolysate is first fed into a continuous enzymatic hydrolysis reactor to mix with the cellulase enzyme stream and maintain the temperature at 48 °C, after which the pressure is increased to 4.08 bar. Then, the mixed stream is split and fed into a stoichiometric reactor to conduct the fermentation and also fed into the seed train unit to give the reactions and conversions of microorganism growth and sugar metabolism [2]. The key design parameters taken from the literature are summarized in Table S2 [2].

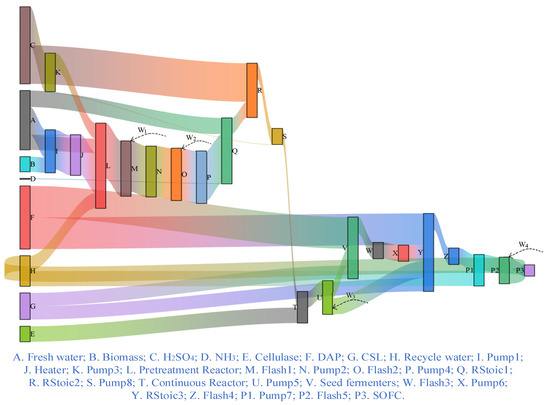

Figures in this section are presented to visually illustrate the distribution and interaction of energy and material flows within the proposed system. These Figures are intentionally used instead of data tables because the quantitative relationships and multidimensional variations cannot be effectively conveyed in tabular form. The Figure layouts are designed to enlarge key labels and adjust colors to improve visual contrast. The captions explicitly describe the main parameters and variation trends, enabling the figures to communicate the essential information more clearly and intuitively.

The main assumptions driving the simulation are summarized in Section 2.2.1. It should be noted that the results from Aspen Plus are not subject to model validation in this work, as this process simulation software is constructed using standard thermodynamic packages and reaction models that have been extensively validated in studies. And the purpose of the simulation is to provide a conceptual and thermodynamic assessment of the proposed system rather than replicate specific experimental results. Such a framework is consistent with previous system-level studies that use Aspen Plus to explore process feasibility and performance trends [4,24]. In this work, the simulation inputs and property methods have been selected according to verified process data reported in previous studies, ensuring the reliability of the derived results. In addition, Aspen Plus and Matlab are used independently in this study. The steady-state process simulation is completed in Aspen Plus, and thermodynamic evaluation is dependent on these data, while the parameter-based analysis for investigating the overall kinetics of the proposed system is realized in the software environment Matlab. No direct data coupling or co-simulation was implemented between the two platforms.

This work analyzes the thermodynamic performance and reaction kinetics of the proposed system; however, no additional rectification columns are included for product recovery, resulting in a low-purity bioethanol stream. Although the present model is expected to provide valuable insight into the thermodynamic behavior of the system, several simplifications should be acknowledged. Heat integration, material degradation, and detailed reaction kinetics are not considered in this work. These assumptions are made to improve model clarity and computational efficiency, with emphasis placed on the exergy and reaction kinetic analysis.

3.2. Thermodynamic Analysis

This work applies the second law of thermodynamics to develop the exergy analysis of the proposed system by accounting for the distinct thermodynamic values of different energy forms and quantities [33,34]. It is widely recognized that the second law of thermodynamics is a well-established principle, forming the foundation for understanding the irreversibility of natural processes and determining the direction of spontaneous changes. In this study, attention is centered on assessing thermodynamic performance and overall feasibility of the proposed system without considering the operational mechanisms of the equipment. Accordingly, the exergy parameters in this study can be reasonably determined based on Aspen Plus. Moreover, the thermodynamic modes of SOFC, such as the relative exergy balance, are also mature and have been validated and successfully employed in previous thermodynamic analyses [34]. From this, it is both reasonable and acceptable to adopt the present model to approximate the thermodynamic performance of the proposed system.

Based on the exergy balance model, the input, output, and destruction of exergy for each piece of equipment are determined, thus offering valuable insights into potential areas for system optimization, particularly the equipment exhibiting a relatively high exergy destruction ratio or notably low exergy efficiency. As shown in Table 2, the highest exergy destruction existed in RStoic 3 with 902.21 kW, while RStoic 1 follows with 736.44 kW. Conversely, minimal exergy destruction is also observed in certain pumps and flashes, accounting for a minor fraction. The exergy efficiencies of the individual equipment are determined based on the data presented in Table 2. Relatively high exergy efficiency is observed in most of the equipment with about 0.99, and minimal exergy efficiency is found in RStoic 3 with 0.21, while RStoic 1 and SOFC follow with 0.24 and 0.29, respectively. As a key parameter for assessing exergy performance, the exergy destruction ratio is calculated using the data provided in Table 2. It can be seen that the values of the exergy destruction ratios in most of the equipment are relatively low. This is mainly because energy integration is not considered in this work; it is assumed that enough electricity is utilized to drive the overall system. Nevertheless, if such a strategy was applied, the total exergy efficiency would likely be enhanced, as part of the waste heat could be recuperated to lessen external exergy demand and to mitigate exergy losses associated with irreversible heat transfer. Hence, the exergy destruction ratio of most of the equipment in this work is relatively high. The relatively high values occurred only in RStoic 3, RStoic 1, and seed fermenters with 3.74, 3.17, and 2.76, respectively. At the same time, the high exergy destruction ratio of SOFC is mainly caused by the complex chemical reactions that occur in the cathode and anode, leading to irreversible loss. According to the above exergy efficiency of each piece of equipment, it can be found that the exergy efficiency of the proposed system is about 0.72. It can be explained that the relatively high exergy destruction due to the irreversible losses of chemical reactions decreases the system’s exergy efficiency.

Table 2.

Exergy parameters of equipment in proposed system.

Based on the simulation results, Figure 4 which is a Sankey diagram visualizes the exergy flow across each component within the proposed system to highlight the dominant loss sources. For simplicity, energy integration is not involved in the proposed system so that the auxiliary power consumption for certain equipment is neglected. The black boxes correspond to each piece of equipment, with each color indicating the exergy flow carried by the respective streams, enabling a direct visualization of input exergy, output exergy, and exergy destruction associated with each piece of equipment in the Sankey diagram. The system-level exergy flow of the entire system starts from the input exergy associated with biomass, fresh water, H2SO4, NH3, diammonium phosphate (DAP), corn steep liquor (CSL), recycle water, and cellulase and terminates at the SOFC. For a single piece of equipment, such as RStoic 3, the input exergy is represented by the sum of NO. 30, NO. 31, NO. 38, and NO. 39 streams, which come from Pump 5, DAP, Pump 6, and CSL, respectively. while output exergy is the exergy flow of stream NO. 42, which moves toward Flash 4, as well as the difference between the input and output exergy, which is the exergy destruction with 902.21 kW. On the whole, exergy destruction accumulates as the flow passes through each piece of equipment, gradually reducing the total exergy available within the system. In view of the overall system, the exergy efficiency is found to be about 0.72. Part of stoichiometric reactors in the conditioning unit, the high-solids hydrolysis unit exhibits the higher exergy destruction, accounting for approximately 60% of total system loss. This is primarily due to significant temperature gradients and inherent chemical irreversibility. Such behavior is consistent with previously reported studies [23] and indicates that the stoichiometric reactor is the dominant source of thermodynamic inefficiency within the integrated system. From a practical perspective, enhancing reactor heat management, improving catalyst activity, and increasing heat recovery effectiveness between hot and cold streams could substantially reduce this exergy loss and improve the overall system performance. Except for the above stoichiometric reactors, the SOFC unit accounts for the largest share of exergy destruction ratio (≈2.51), mainly due to electrochemical irreversibility and heat dissipation. This indicates that improvements in cell design and thermal management would yield the most significant gains in system performance. These results provide practical guidance for identifying key targets in future system optimization and scale-up design.

Figure 4.

Sankey diagram showing the exergy flow through the proposed system.

Although previous studies have reported systems integrating biomass gasification with SOFC, these process routes differ fundamentally from the proposed system. The former one involves high-temperature oxidation and syngas fermentation, whereas the SHF route in the proposed system provides the co-fermenting microorganism after the enzymatic hydrolysis. Due to these intrinsic differences in feedstock state, reaction pathways, and system boundaries, a direct quantitative comparison is beyond the scope of this work. Therefore, this study limits the discussion to qualitative aspects previously summarized in the literature, highlighting that the proposed system offers a complementary route for the integration of bioenergy utilization rather than a direct alternative to gasification–SOFC systems.

3.3. Base Case Analysis

The integrated system is developed according to the lignocellulosic biomass SHF process and direct-ethanol SOFC, including large-scale processes and numerous reactions, particularly complex bioreactions. These characteristics posed significant challenges to perform a systematic analysis of the integrated system using a full mechanism model of the reaction. As described in Section 2.2.5, since overall reaction order is unknown, a parameter-based methodology for modeling the reaction kinetic is introduced. To manage complexity, this study divided the problem into a series of sub-cases, each containing eight potential combinations of the reaction order. The analysis is then started from and with the fixed value, which are both equal to 0. This is adopted as a base case, upon which alternative cases are developed and subsequently evaluated in greater detail. All analyses are carried out using commercial software framework comprising Aspen Plus and Matlab, in which the former is employed to model the steady-state process and the latter provides the data analysis with solving the equations.

3.3.1. Effects of Reaction Time and Concentration on the SHF Route

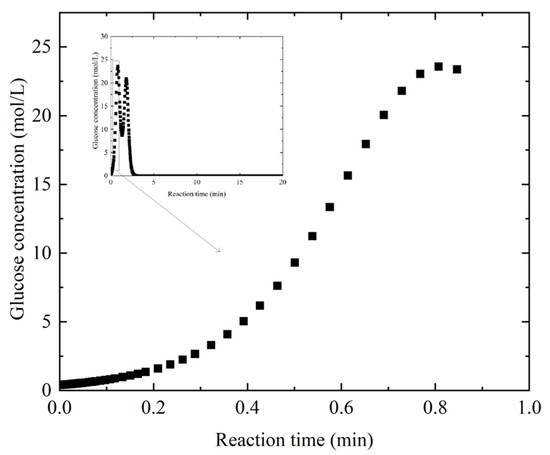

Cellulose, which consists entirely of glucose, is the most abundant renewable polysaccharide within the lignocellulosic biomass and is served as the primary target for bioconversion into liquid biofuels such as bioethanol [38]. In this study, corn stover is chosen as the feedstock due to relatively low lignin and high cellulose content and hemicellulose fractions. From this perspective, the first challenge lies in achieving complete enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose to glucose, ensuring efficient substrate utilization for subsequent biofuel production [38]. With a glucose utilization value of 0.95 and a bioethanol productivity value of 36.6, the primary reaction takes place in the seed fermenters, which also explains one reason for the high exergy destruction in this equipment, as discussed in Section 3.2. Figure 5 shows the variation in glucose concentration as a function of reaction time. The horizontal axis represents the reaction time, which has total duration of 20 min, and the vertical axis represents the glucose concentration, which ranges from 0 to 30 mol/L. To more clearly illustrate the behavior of the curve over a specific interval, the regions corresponding to a reaction time of 0–1 min and a glucose concentration of 0–25 mol/L are shown in an enlarged view. Overall, the concentration exhibits a steady rise as the reaction progresses, reflecting the gradual conversion of cellulose into glucose, and eventually converges to a relatively stable value, being able to convert to bioethanol. But a fluctuation in the concentration appeares to last for a certain period of time. In this work, the total cellulase loading, representing the enzyme protein concentration responsible for cellulose hydrolysis, is determined, following the literature which typically assumes a finite maximum conversion to glucose [3]. Furthermore, previous studies indicate that pretreated biomass streams containing more than 20% total solids are difficult to handle using pumps, making it challenging to accurately assess system performance through modeling [3]. Although enzymatic hydrolysis involves multiple reactions, including variations in rate constants, the time-resolved dynamics of product formation and enzyme state transitions, such as the release of cellobiose units by complexed or active enzyme, are not tracked in the present simulation. Thus, the reaction rate in this study represented through the simplified power law models can be directly simulated directly using ode45 solver in Matlab software, enabling the state dynamics to be discretized into a set of differential–algebraic equations.

Figure 5.

Effect of reaction time on glucose concentration.

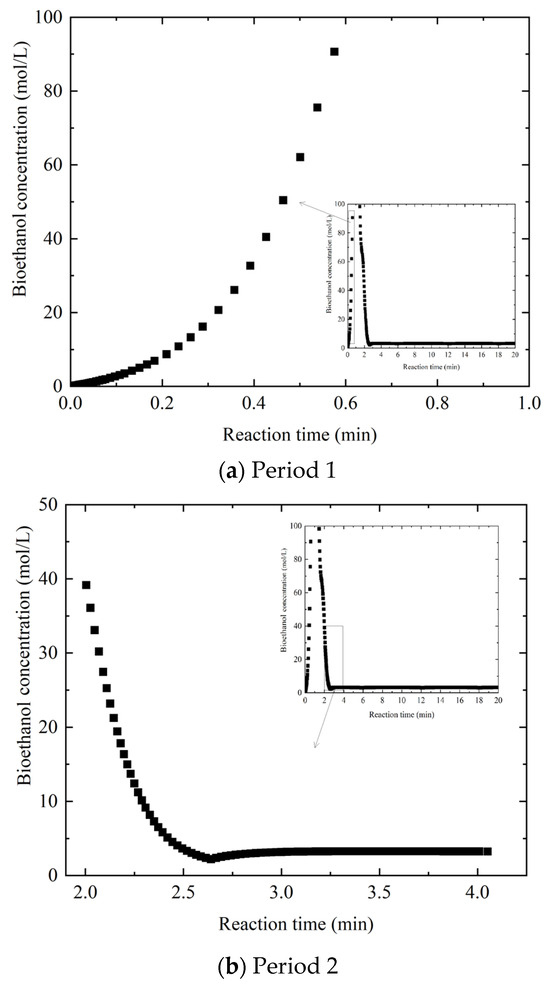

The above fluctuation acts as disturbances to downstream processing units of the proposed system, as shown in Figure 6. The horizontal axis represents the reaction time, which has total duration of 20 min, and the vertical axis represents the bioethanol concentration, which ranges from 0 to 100 mol/L. To more clearly illustrate the behavior of the curve over a specific interval, the regions corresponding to a reaction time of 0–1 min and a glucose concentration of 0–100 mol/L and those with a reaction time of 2–4 min and a glucose concentration of 0–50 mol/L are shown in an enlarged view. The bioethanol concentration displays a generally upward trend over the reaction time; however, it is influenced by fluctuations in glucose concentration, as illustrated in the two enlarged plots representing distinct time intervals. Although the glucose concentration eventually reaches convergence and remains stable, bioethanol does not follow the same pattern, instead continuing to fluctuate until the later phases of the simulation. In the end, the system settles at a comparatively low bioethanol concentration, which primarily results from the limited steady-state concentration of glucose, inherently constraining the maximum yield of bioethanol. The persistent mismatch between glucose stabilization and bioethanol production highlights the complex relationship between substrate availability and metabolic conversion in lignocellulosic biorefining [38].

Figure 6.

Effect of reaction time on bioethanol concentration for different periods.

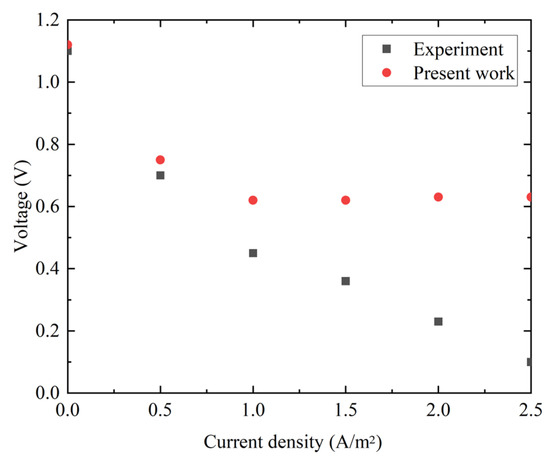

3.3.2. Effects of Voltage and Current Curves on the Direct-Ethanol SOFC

To evaluate the effect of operating voltage on the performance of the direct-ethanol SOFC in the proposed system, as well as to perform model validation with data from the literature [39], the simulations are conducted across a current density range corresponding to operating voltages from 1.12 V to 0.63 V, as illustrated in Figure 7. As the current density rises, which is supported by both the simulation results obtained in this study and the experimental data given by the literature [39], the inherent voltage losses become increasingly obvious, leading to a continuous decline in the output voltage. It can be found that the simulation results during specific operating intervals exhibit strong agreement with the experimental data. The relative error in the voltage output is less than 5% when the current density changes from 0 to 0.5 A/m2, while the value becomes more noticeable by ignoring the voltage loss in this study, which is generated by activation over-potentials in anode/cathode. Indeed, both the mechanism and the data-driven modeling of SOFC have been extensively studied in the recent literature, whereas the research of the highly integrated SHF process and SOFC will try to find possible better solution for achieving appropriate energy efficiency during biofuel production and utilization. Therefore, the investigation of this work is focused on analyzing the feasibility of the overall system through thermodynamic evaluation rather than pursuing further model validation.

Figure 7.

Effects of voltage and current curves on the direct-ethanol SOFC.

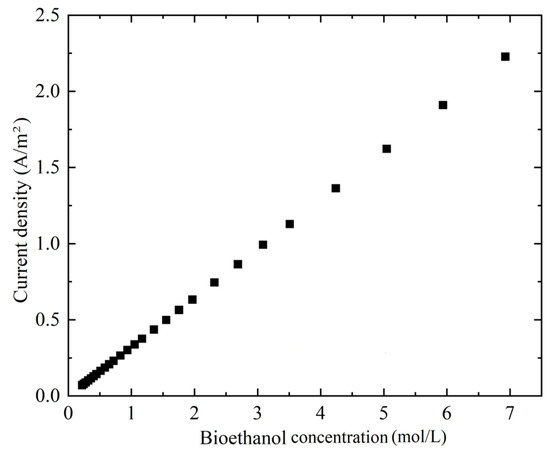

3.3.3. Effects of Concentration of Bioethanol and Current Curves on the Direct-Ethanol SOFC

The involvement of bioethanol in the SOFC plays a pivotal role in linking bioproduct generation with electrochemical conversion processes. Accordingly, this section focuses on examining how bioethanol output directly affects the current density. As depicted in Figure 8, an increase in bioethanol concentration supports the power generation. A near-linear relationship emerges between bioethanol concentration and current density, although the comparatively higher current density appears at the lower bioethanol concentration. This trend implies that the rate-determining effect of the bioethanol-driven SOFCs can be considered. The observed enhancement can primarily be attributed to two underlying factors. First, the sufficient supply of bioethanol within the electrochemically active zone, particularly near the anode–electrolyte interface of the SOFC, promotes an increase in current density. Second, an increase in current density results in greater overpotential heat generation within the membrane electrode assembly, which could favor more complete bioethanol conversion from the thermodynamic perspective. Thus, it can be found that reducing the amount of the supplied bioethanol diminishes both the electrochemical performance and the possible bioproduct integration, particularly when the SOFC operates as part of a broader energy hub incorporating multiple energy sources for conversion and utilization. On the other hand, supplying an excessively high quantity of bioethanol introduces additional parasitic energy consumption. Consequently, in practice, optimizing the bioethanol feed rate to be transported into the SOFC becomes an important consideration for system designers, representing a trade-off between long-term durability and overall energy efficiency [40,41].

Figure 8.

Effects of bioethanol concentration and current characteristics on the SOFC at an operating temperature of 750 °C.

3.4. Reaction Kinetic Analysis

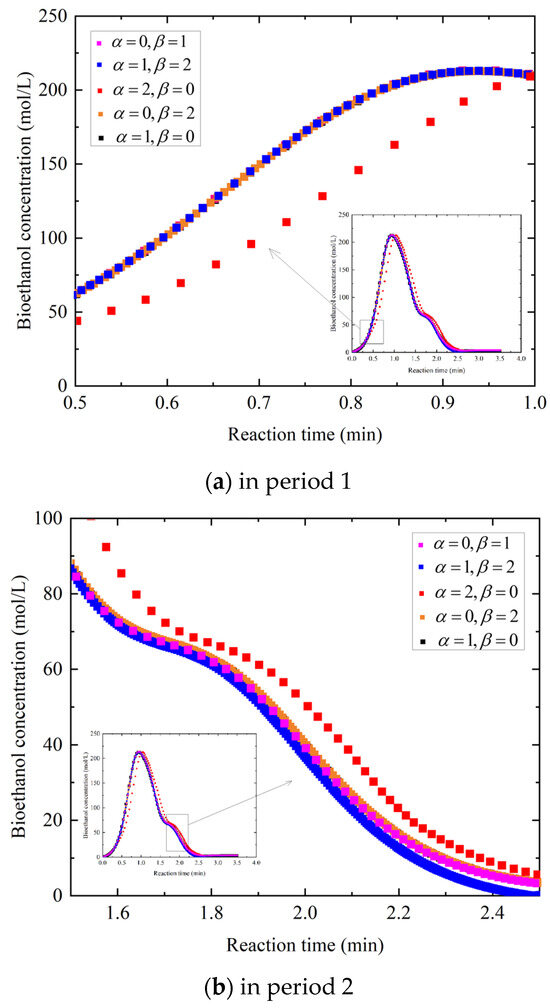

After evaluating system performance in the base case, seven main sub-cases are built to analyze the reaction kinetic generated from the reaction order considerations of (1) = 1 and = 0, (2) = 0 and = 1, (3) = 1 and = 1, (4) = 2 and = 0, (5) = 0 and = 2, (6) = 1 and = 2, and (7) = 2 and = 1. As shown in Section 2.2.5, the bioethanol concentration data obtained from the SHF process are utilized to plot the linearized reaction kinetic models, incorporating the aforementioned combinations of and for three reactions under a specific operating condition. Figure 9a,b provides a graphical representation considering effects over broad time and length scales, while different orders of reactants show different reaction rate constants for the three selected reaction kinetic models. The horizontal axis represents the reaction time, which has total duration of 4 min, and the vertical axis represents the bioethanol concentration, which ranges from 0 to 250 mol/L. To more clearly illustrate the behavior of the curve over a specific interval, the regions corresponding to a reaction time of 0.5–1 min and a glucose concentration of 0–250 mol/L and those with a reaction time of 1.5–2.5 min and a glucose concentration of 0–100 mol/L are shown in an enlarged view. The largest reaction rate constant in the base case, in which and are both equal to 0, is for the reaction in RStoic 1 with 0.21, and the lowest is for the reaction in RStoic 2 with 0.006, although the graphical representation of reaction kinetic models with the base case is not considered. Comparing to the base case, the reaction rate constants in the above sub-cases are calculated, except the two with = 1 and = 1 and = 2 and = 1, since the equations for the other sub-cases yield the real roots, whereas these two roots are imaginary. For = 1 and = 0, the reaction rate constants in RStoic 1 are the same with 0.11, while the one in RStoic 2 is extremely close with the base case. For = 0 and = 1, the reaction rate constants in RStoic 1 are the same with 65.29, while the one in RStoic 2 is 0.092. For = 2 and = 0, the reaction rate constants in RStoic 1 are 0.05 and 0.18, respectively, while the one in RStoic 2 is extremely close with the base case. For = 0 and = 2, the reaction rate constants in RStoic 1 are 0.097 and 2.16, respectively, while the one in RStoic 2 is extremely close with the base case. For = 1 and = 2, the reaction rate constants in RStoic 1 are 0.11 and 3.94, respectively, while the one in RStoic 2 is extremely close with the base case. The rate constant serves as a key kinetic parameter that quantifies the intrinsic speed of a chemical reaction, where larger values imply faster rate of conversion. In RStoic 1, ammonia gas may have either first- or second-reaction order, whereas both acetic acid and the sulfuric acid follow a zero-reaction order. Such an unpredictable value suggests that the reactants introduce a limited overall influence on the reaction rate within the RStoic 1 and RStoic 2. Given the acid excess in these reactions, the impact of declining acid concentration on the increase in bioethanol concentration appears to be negligible.

Figure 9.

Effect of reaction kinetic models with different combinations of and on the bioethanol concentration in different periods.

4. Conclusions

This study proposes a novel system combining SHF with a bioethanol-fueled SOFC. The system comprises a pretreatment reactor unit, a conditioning unit, a high-solids hydrolysis unit, a seed train unit, an ethanol recovery unit, and an SOFC unit. Bioethanol produced in the SHF subsystem is fed into the SOFC subsystem to enhance overall system efficiency. The thermodynamic performance of the system is systematically investigated through exergy analysis. Additionally, typical reaction orders are selected to further explore the operational behavior. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Exergy analysis reveals that the major source of exergy occurs in the high-solids hydrolysis unit, in which Rstoic 3 and Continuous reactor have the relatively low exergy efficiency, reaching 0.21 and 0.51, respectively, due to a chemical reaction in the larger vessels. The other main exergy destruction occurs in the conditioning unit, which generates high irreversible losses due to the chemical reactions, in which the exergy efficiency of Rstoic 1 and Rstoic 2 reach 0.24 and 0.29, respectively.

- (2)

- The bioethanol concentration increased with the reaction time due to gradual hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass slurry. The reactants introduce a limited overall influence on the reaction rate within RStoic 1 and RStoic 2. Given the excess acid in these reactions, the effect of declining acid concentration on the increase in bioethanol concentration appears to be negligible.

In summary, the proposed integrated system achieves a total exergy efficiency of about 0.72. These results confirm that the coupling of SHF route and SOFC enables efficient conversion of lignocellulosic biomass into electricity. This work plays a pivotal role in enabling the centralized and efficient utilization of biomass resources while introducing a comprehensive framework for evaluating both thermodynamic performance and reaction kinetic. This work offers valuable theoretical and methodological support for advancing biomass conversion processes and provides practical guidance for accelerating the technological maturity and large-scale deployment of biorefinery systems. On the other hand, the designed system is particularly suitable for areas with both abundant biomass resources and localized energy demands, such as small industrial parks or self-sustained islands. In such scenarios, centralized biomass utilization can effectively overcome challenges in transport and storage while enhancing energy conversion efficiency. Thus, the proposed system not only supports decentralized clean energy deployment but also provides a practical approach to achieving regional carbon neutrality and sustainable bioenergy development.

However, it is recognized that incorporating heat recovery schemes and degradation effects could further refine the results and provide a more realistic representation of long-term system performance. Future work will aim to expand the current model to include these aspects and evaluate their quantitative influence on overall efficiency. Additionally, energy integration strategies will be explored to enhance system performance through improved waste heat recovery.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/en18246456/s1. Table S1. Proximate analysis of characteristics of biomass material (dry basis). Table S2. Input parameters of the proposed system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G. and Y.L.; methodology, S.G.; software, S.G. and Y.L.; validation, S.G.; formal analysis, S.G. and Y.L.; investigation, S.G. and Y.Z.; resources, S.G. and Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.G. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, S.G. and Y.Z.; visualization, S.G.; supervision, S.G. and Y.Z.; project administration, S.G. and Y.Z.; funding acquisition, S.G. and Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, under grant number 22408027 and 22478057, and also by the Changzhou Science and Technology Program, under grant number CJ20240071.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| Symbols | |

| c | concentration of reactants |

| E | open-circuit potential |

| EXD | exergy destruction |

| EXI | input exergy |

| EXO | output exergy |

| EX | exergy |

| F | Faraday constant |

| fc | final molar concentration |

| h | enthalpy |

| ic | initial molar concentration |

| k | reaction rate constant |

| m | mass flow rate |

| N | number of SOFCs |

| P | partial pressure |

| r | reaction rate |

| R | exergy destruction ratio |

| RC | ideal gas constant |

| s | entropy |

| T | temperature |

| U | glucose utilization |

| Y | bioethanol productivity |

| z | molar amount |

| inlet molar flux | |

| lower heating value | |

| multiplication factor | |

| mass fraction | |

| exergy efficiency | |

| reaction order | |

| reaction order | |

| initial molar ratio of reactants | |

| SOFC | solid oxide fuel cell |

| SHF | separate hydrolysis and fermentation |

References

- Naveed, M.H.; Khan, M.N.A.; Mukarram, M.; Naqvi, S.R.; Abdullah, A.; Haq, Z.U.; Ullah, H.H.; Mohamadi, A. Cellulosic biomass fermentation for biofuel production: Review of artificial intelligence approaches. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 189, 113906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbird, D.; Davis, R.; Tao, L.; Kinchin, C.; Hsu, D.; Aden, A. Process Design and Economics for Biochemical Conversion of Lignocellulosic Biomass to Ethanol: Dilute-Acid Pretreatment and Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Corn Stover; Technical Report NREL/TP-5100-47764; National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Valles, A.; Álvarez-Hornos, F.J.; Martínez-Soria, V.; Marzal, P.; Gabaldón, C. Comparison of simultaneous saccharification and fermentation and separate hydrolysis and fermentation processes for butanol production from rice straw. Fuel 2020, 282, 118831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Dong, C.; Hu, X.; Xue, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X. Techno-economic evaluation of a combined biomass gasification-solid oxide fuel cell system for ethanol production via syngas fermentation. Fuel 2022, 324, 124395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallel, F.; Neifar, M.; Kacem, I.; Chaabouni, S.E. Optimization of enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation of bleached garlic straw for bioethanol production. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2024, 26, 2880–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albahri, T.A.; Khor, C.S.; Elsholkami, M.; Elkamel, A. A mixed integer nonlinear programming approach for petroleum refinery topology optimisation. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2019, 143, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankoju, A.S.; Shastri, Y. Regional sustainability of food–energy–water nexus considering water stress using multi-objective modeling and optimization. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2025, 205, 109433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, D.A.; McCormick-Mantilla, J.A.; Ricardez-Sandoval, L.A. Economic nonlinear model predictive control and scheduling of multiple fed-batch fermenters in a lignocellulosic biorefinery. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2025, 201, 109223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.; Testa, R.L.; Ramos, F.D.; Estrada, V.; Diaz, M.S. Process Systems Engineering Approach for the Sustainable Design of Cyanobacteria-Based Integrated Biorefineries and Their Heat Exchanger Network. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 3538–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrozo, H.A.; Casoni, A.I.; Ramos, F.D.; Estrada, V.; Diaz, M.S. Simultaneous design of macroalgae-based integrated biorefineries and their heat exchanger network. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2022, 164, 107885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Q.; Luo, Z.; Sun, H.; Wei, Q.; Shi, J.; Li, L.; Wang, K.; Zhou, J. Process evaluation of simulated novel cellulosic ethanol biorefineries coupled with lignin thermochemical conversion. Renew. Energy 2024, 231, 120965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Li, L.; Yun, L. Modeling and economic optimization of cellulosic biofuel supply chain considering multiple conversion pathways. Appl. Energy 2021, 281, 116059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, P.S.; Oliveira, S., Jr. Exergy analysis of pretreatment processes of bioethanol production based on sugarcane bagasse. Energy 2014, 76, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratto, B.; Santos-Rocha, M.S.R.; Longati, A.A.; Júnior, R.S.; Cruz, A.J.G. Experimental optimization and techno-economic analysis of bioethanol production by simultaneous saccharification and fermentation process using sugarcane straw. Bioresource Technol. 2020, 297, 122494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benalcázar, E.A.; Noorman, H.; Filho, R.M.; Posada, J.A. Decarbonizing ethanol production via gas fermentation: Impact of the CO/H2/CO2 mix source on greenhouse gas emissions and production costs. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2022, 159, 107670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenila, F.; Shastri, Y. Stochastic optimization of enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2020, 135, 106776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, L. Modeling and optimization of bioethanol production planning under hybrid uncertainty: A heuristic multi-stage stochastic programming approach. Energy 2022, 245, 123285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbarzadeh, A.; Shamsi, M. Designing a resilient and sustainable multi-feedstock bioethanol supply chain: Integration of mathematical modeling and machine learning. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 123794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Tao, S.; Hu, L.; Zhang, X.; Lin, X. Process optimization for deep eutectic solvent pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis of sugar cane bagasse for cellulosic ethanol fermentation. Renew. Energy 2021, 177, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ji, L.; Yin, J.; Huang, G. Optimal design and robust operational management of regional bioethanol supply chain with various technological choices and uncertainty fusions. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2024, 182, 108565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, A.M.; Okoro, O.V.; Chireshe, F.; Moonsamy, T.; Görgens, J.F. Systematic cost evaluations of biological and thermochemical processes for ethanol production from biomass residues and industrial off-gases. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 243, 114398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alherbawi, M.; McKay, G.; Al-Ansari, T. Development of a hybrid biorefinery for jet biofuel production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 276, 116569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadabadi, M.J.R.; Balali, A.; Moghimi, M.; Ahmadi, R. Comparative analysis of a biomass-fueled plant coupled with solid oxide fuel cell, cascaded organic Rankine cycle and liquid hydrogen production system: Machine learning approach using multi-objective grey wolf optimizer. Fuel 2025, 380, 133269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Dahan, F.; Chaturvedi, R.; Almojil, S.F.; Almohana, A.I.; Alali, A.F.; Almoalimi, K.T.; Alyousuf, F.Q.A. Thermodynamic performance optimization and environmental analysis of a solid oxide fuel cell powered with biomass energy and excess hydrogen injection. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 1142–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Yu, Z.; Liu, W.; Ji, S. Investigation of a novel near-zero emission poly-generation system based on biomass gasification and SOFC: A thermodynamic and exergoeconomic evaluation. Energy 2023, 282, 128822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Samanta, S.; Roy, S.; Smallbone, A.; Roskilly, A.P. Fuel cell integrated carbon negative power generation from biomass. Appl. Energy 2023, 331, 120449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Al-attab, K.A.; Heng, T.Y. Optimization of solid oxide fuel cell system integrated with biomass gasification, solar-assisted carbon capture and methane production. J. Clean Prod. 2024, 449, 141712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatef, M.; Gholamian, E.; Mahmoudi, S.M.S.; Mehr, A.S. Enhancing efficiency and reduced CO2 emission in hybrid biomass gasification with integrated SOFC-MCFC system based on CO2 recycle. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 313, 118611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Lam, M.K.; Cheng, Y.W.; Uemura, Y.; Mansor, N.; Lim, J.W.; Show, P.L.; Tan, I.S.; Lim, S. Reaction kinetic and thermodynamics studies for in-situ transesterification of wet microalgae paste to biodiesel. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2021, 169, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoghi, M.; Gharaie, S.; Hosseinzadeh, N.; Zare, A. 4E analysis and optimization comparison of solar, biomass, geothermal, and wind power systems for green hydrogen-fueled SOFCs. Energy 2024, 313, 133740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abada, S.; Tebbouche, L.; Bessah, R.; Kechkar, M.; Berrached, A.; Saber, M.; Aziza, M.; Amrane, A. Experimental study and kinetic modelling of bioethanol production from industrial potato waste. Biomass Convers. Bior. 2022, 14, 7735–7741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Liu, B.; Jia, L.; Yan, D.; Li, J. Liquid biofuels for solid oxide fuel cells: A review. J. Power Sources 2023, 556, 232437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, W.; Zhu, P.; Yao, J.; Zhang, S.; Ren, J.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Z. Combined biomass gasification, SOFC, IC engine, and waste heat recovery system for power and heat generation: Energy, exergy, exergoeconomic, environmental (4E) evaluations. Appl. Energy 2020, 279, 115794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Wu, Z.; Guo, L.; Yao, J.; Dai, M.; Ren, J.; Kurko, S.; Yan, H.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Z. Achieving high-efficiency conversion and poly-generation of cooling, heating, and power based on biomass-fueled SOFC hybrid system: Performance assessment and multi-objective optimization. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 240, 114245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Exergy Calculator. Online Tool Available Exergoecology Portal. Available online: http://www.exergoecology.com (accessed on 1 May 2018).

- Wooley, R.; Putsche, V. Development of an ASPEN PLUS Physical Property Database for Biofuels Components; National Renewable Energy Lab.: Golden, CO, USA, 1996; Volume 38. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, S.R.J. Hawley’s Condensed Chemical Dictionary, 15th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 30–56. [Google Scholar]

- Jeoh, T.; Cardona, M.J.; Karuna, N.; Mudinoor, A.R.; Nill, J. Mechanistic Kinetic Models of Enzymatic Cellulose Hydrolysis—A Review. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017, 114, 1369–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ou, C.; Chen, J. A new analytical approach to model and evaluate the performance of a class of irreversible fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2008, 33, 4161–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Xu, H.; Tan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Cai, W.; Chen, M.; Ni, M. Thermal modelling of ethanol-fuelled Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Appl. Energy 2019, 237, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Peng, S.; Jing, Y.; Wei, S.; Zhang, Q.; Ding, H.; Li, H. Exploration of separate hydrolysis and fermentation and simultaneous saccharification and co-fermentation for acetone, butanol, and ethanol production from combined diluted acid with laccase pretreated Puerariae Slag in Clostridium beijerinckii ART44. Energy 2023, 279, 128063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).