Abstract

An attempt was made to adapt the physical and chemical characteristics of rapeseed oil (Ro), including its density, viscosity and surface tension to diesel oil in the aspect of its use as a biofuel in diesel engines by adding 10 and/or 15 percent n-hexane to the oil and contacting the obtained mixture with ethanol. After establishing an equilibrium of ethanol extraction in the phase containing a mixture of Ro and n-hexane and the mixture components in ethanol, measurements of the viscosity, surface tension and density of oil phases were performed. The obtained values of these physicochemical parameters for the Ro and n-hexane mixture phase were close to those of diesel oil. Next, engine tests were carried out on the Ro+n-hexane mixture after its contact with ethanol under real driving conditions. The tests showed that the mixture of rapeseed oil with 10% n-hexane in contact with ethanol achieved the highest torque and power values among all Ro-based fuels, and that the decrease in these parameters compared to diesel fuel was the smallest. Moreover, compared to Ro and the mixture of Ro with 10% n-hexane, a higher energy efficiency was obtained, which is due to the favorable physicochemical properties of the fuel—the reduced viscosity and improved volatility.

Keywords:

fuel alternatives; rapeseed oil; n-hexane; ethanol; viscosity; density; surface tension; diesel engine; common rail 1. Introduction

The automotive sector is undergoing a significant transformation driven by stringent emission reduction targets and rapid advances in propulsion technologies. While electric vehicles (EVs), powered by electric batteries, are experiencing substantial growth, internal combustion engines (ICEs), which rely on the combustion of fuel, continue to play a crucial role and are expected to remain prevalent in the coming years, often in hybrid configurations. Although the push toward electrification is reshaping the automotive industry, ICEs—particularly as part of hybrid systems—will remain essential for addressing both consumer needs and environmental objectives in the foreseeable future [1,2,3,4]. The propulsion architecture of modern vehicles is being redefined under the dual pressure of emission regulations and technological innovation. Despite rapid developments in the field of electric mobility, ICEs still hold strategic relevance, particularly when integrated with hybrid powertrains. Alongside the advancement of electric powertrains, many researchers are investigating the use of vegetable oils and their blends as substitute energy sources for diesel engines. These investigations focus on modifying the physicochemical properties of such fuels—for example, through the addition of solvents—and evaluating their impact on engine performance. Many experimental studies show that properly formulated mixtures can improve viscosity, ignition characteristics and atomization, which in turn affect the combustion process and engine output. This body of research provides the current context and underscores the innovative nature of the present study [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

The production of biofuel is still a current and important research topic. This renewable fuel can be produced from various raw materials, including, among others, animal fats, cooking and plants oils and microalgae [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27], but, quite often, various vegetable oils are used for this purpose [28,29,30]. Previous research has explored both biodiesel derived from rapeseed oil (Ro) through transesterification [31,32,33,34,35,36,37] and the straightforward utilization of raw vegetable oils as replacements for diesel fuel [38,39,40,41,42]. The present study focuses on modifying raw rapeseed oil without transesterification. Unfortunately, the significant differences in viscosity between rapeseed oil and conventional diesel fuel (Df) prevent the direct use of unmodified rapeseed oil in diesel engines. Even though rapeseed oil is rich in unsaturated fatty acids like oleic, linoleic and α-linolenic acids, its viscosity, density and surface tension are greater than those of the individual components [43]. On the other hand, the lower heating value (LHV) of rapeseed oil is typically around 37–39 MJ·kg−1, which is about 10–15% lower than that of conventional diesel fuel (42–43 MJ·kg−1) [44,45]. This difference in energy content contributes to the lower torque and power observed for rapeseed oil-based fuels. In earlier studies, the results showed that introducing n-hexane (Hex) markedly changes the physicochemical characteristics of rapeseed oil, making them more similar to those of diesel fuel [46,47,48]. Since viscosity is directly dependent on pressure, this implies that a reduction in the intermolecular distance between the components of rapeseed oil, relative to their individual compounds, increases intermolecular forces and results in a higher viscosity. Therefore, to tailor the physicochemical properties of rapeseed oil to more closely resemble diesel fuel, it is necessary to add substances that not only exhibit lower values of these parameters but also have the ability to increase the intermolecular spacing within the oil matrix. The authors demonstrated that n-hexane and ethanol (Et) meet the aforementioned requirements as additives. In particular, 10% n-hexane added to rapeseed oil results in a more than threefold reduction in its viscosity. This effect was confirmed through both physicochemical analyses and experimental studies, in which a compression–ignition engine installed in a vehicle was fueled with this mixture. These changes positively influenced the combustion process and engine performance parameters such as torque and power, bringing them closer to the values observed when using conventional diesel fuel. Simultaneously, changes were noted in the combustion profile, including delayed auto-ignition and the disappearance of the kinetic combustion phase, which may affect NOx emissions. Taking this into account, the aim of the presented studies was focused on an alternative approach to ethanol utilization. The novelty of this approach lies in applying an alternative ethanol contacting method, where the Ro+Hex mixture is exposed to ethanol and then phase-separated.This process modifies the concentration of Hex, ethanol and some components of Ro and thus its structure, and in turn causes physicochemical properties that are different than direct ethanol addition. Moreover, the present paper integrates a detailed surface tension analysis (Lifshitz-van der Waals (LW) and acid-base (AB) components) with dynamic vehicle engine testing, providing a broader insight into both physicochemical mechanisms and practical fuel applicability. For this reason, mixtures of rapeseed oil (Ro) with 10% and 15% n-hexane were contacted with ethanol (Et), and then the measurements of the viscosity, surface tension and density were carried out. The concentrations of 10–15 vol% n-hexane and 2 vol% ethanol were chosen based on earlier results showing that 10 vol% n-hexane reduces Ro viscosity by over threefold, while higher concentrations bring negligible improvement [46,47,48]. The 2 vol% ethanol content provided a baseline for direct ethanol addition, allowing a comparison with the alternative ethanol contact method (RoHex/Et). The obtained results were compared with Ro, Df, Hex and Et, as well as mixtures of Ro with 10% and 15% n-hexane and 2% ethanol (RoHex10+Et2 and RoHex15+Et2). Taking into account the analysis of the psychochemical properties of such systems, the next mixtures for engine tests were selected. Also, for the surface tension components and parameters determination, the contact angle measurements of Ro, Df, Hex and Et, as well as all mixtures, were carried out on polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE). The obtained contact angle values were compared to those obtained on an engine valve.

An another important feature of the conducted research was the use of a test vehicle under real driving conditions simulated on a chassis dynamometer, which made it possible to analyze engine operation not only under steady-state conditions but also under dynamic load conditions, closer to actual vehicle use [49]. This clearly distinguished the study from standard engine bench tests. Another relevant aspect was that the experiments were carried out with the factory engine control unit (ECU) settings, without any interference in the control strategy, which allowed for an assessment of engine behavior under conditions corresponding to real vehicle operation. In addition, exhaust toxicity measurements were taken upstream of the aftertreatment system, ensuring that components such as the catalytic converter or diesel particulate filter did not affect the obtained results. This enabled a direct evaluation of the impact of the tested fuels on the combustion process.

The assessment covered key engine performance parameters such as torque, power, indicated mean effective pressure (IMEP), ignition delay, combustion development and its stability. In parallel, the emission of the main exhaust components—NOx, CO, CO2 and residual O2—was analyzed, as these currently represent a decisive criterion in driving tests and homologation procedures. This emphasizes that ecological evaluation is equally important as the analysis of mechanical performance, while the obtained results reflect both the properties of the tested alternative fuels and the influence of injection and combustion processes on diesel engine operation. The objective of the study was to demonstrate that the appropriate modification of rapeseed oil through the addition of n-hexane and ethanol contact can provide engine performance parameters and combustion characteristics closer to those of diesel fuel, while simultaneously reducing the emission of selected exhaust components. From a broader perspective, the expected outcome is to indicate a development path for second-generation biofuels that can meet both user operational requirements and increasingly stringent environmental regulations.

2. Methodology

2.1. Fuel Specifications

For the measurement and preparation of mixtures, the following materials were used: rapeseed oil (Ro), marketed as Kujawski (ZT “Kruszwica” S.A., Kruszwica, Poland), n-hexane (Hex, ReagentPlus ≥ 99%, Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA)) and ethanol (Et, 96% purity, POCH Poland). The study examined the following mixtures:

- Mixture of rapeseed oil with 10% n-hexane—RoHex10,

- Mixture of rapeseed oil with 15% n-hexane—RoHex15,

- Mixture of rapeseed oil with 10% n-hexane and 2% ethanol—RoHex10+Et2,

- Mixture of rapeseed oil with 15% n-hexane and 2% ethanol—RoHex15+Et2,

- Mixture of rapeseed oil with 10% n-hexane contacted with ethanol–RoHex10/Et,

- Mixture of rapeseed oil with 15% n-hexane contacted with ethanol–RoHex15/Et.

The RoHex10/Et and RoHex15/Et mixtures were made by first preparing a binary Ro and Hex mixture at a proper Hex percentage concentration. Next, this mixture, was shaken with the same volume of ethanol for 15 min with a speed of 100 rpm at a temperature of 293.15 K. The solutions obtained were left for 24 h at room temperature for the phase separation. After 24 h of settling, the mixture separated into oil and alcohol phases. The oil (Ro-rich) phase was carefully decanted and used for all subsequent physicochemical and engine measurements, while the alcohol phase was disposed of.

All mixture ratios presented in this study are expressed in volume percent (vol.%).

For the contact angle measurements, the plate made from the polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) (ZA, Tarnów, Poland) and the engine valve were used.

2.2. Experimental Setup

2.2.1. Engine Operating Tests

The tests were carried out using a diesel engine equipped with a common rail injection system, installed in a Fiat Qubo vehicle compliant with the Euro 5 emission standards. The test vehicle was fitted with a five-speed manual transmission. To enable operation with different fuels, an auxiliary fuel system was installed, consisting of an external fuel tank and an independent supply pump, which allowed quick switching between the tested fuel blends. Modifications to the fuel system were limited solely to the low-pressure section, operating at approximately 3 bar. After activating the auxiliary fuel supply line, the original low-pressure system was automatically disconnected. The high-pressure system remained in its factory configuration, ensuring identical injection conditions for all experimental runs. The technical specifications of the engine and a photograph of the test vehicle are presented in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1.

Technical data of the 1.3 Multijet engine used in the Fiat Qubo test vehicle.

Figure 1.

The experimental setup used to simulate vehicle operation under traction conditions consisted of the following components: 1. Fiat Qubo test vehicle equipped with a 1.3 Multijet engine; 2. computer workstation running AVL IndiCom V2.7; 3. Indimicro 602 system for in-cylinder pressure indication; 4. DF4FS-HLS chassis dynamometer; 5. auxiliary fuel tank forming part of the additional fuel supply system; 6. rotameter integrated with the Simex Multicon CMC-99 module; 7. Bosch KTS diagnostic interface; 8. exhaust gas concentration measurement system AVL SESAM i60 FT (Analyzers SESAM i60 FT consisting of SESAM i60 FT COMBI i60 FID/O2); 9. HSS—heated sampling system; 10. sampling location: upstream of the exhaust aftertreatment system (pre-aftertreatment).

The study utilized an AVL engine indicating system—IndiMicro 602—manufactured by AVL List GmbH (Graz, Austria)—in conjunction with the AVL SESAM i60 FT exhaust gas analysis system (model: SESAM i60 FT COMBI i60 FID/O2-2) for measuring the concentration of toxic exhaust components. Exhaust gas sampling was conducted upstream of the exhaust aftertreatment system (pre-aftertreatment), using a heated gas extraction setup (HSS—heated sampling system) to ensure the integrity of the sampled gases. The test bench setup is described in detail in reference [50]. The operating characteristics of the diesel engine, evaluated under conditions reflecting the vehicle’s traction load, were measured using a DF4FS-HLS chassis dynamometer. The test bench employed in the experiments is shown in Figure 1.

The functioning of a combustion engine in a traction vehicle is characterized chiefly by dynamic operating conditions. To evaluate the energy and environmental performance parameters of engines, driving tests were employed. Currently, the most commonly applied driving test for light-duty vehicles is the WLTP (Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicles Test Procedure) [51]. The tests were carried out on a direct-drive chassis dynamometer, where the vehicle was subjected to rolling resistance simulated by the dynamometer’s loading system. The analysis of the WLTP test cycle allowed for the selection of constant vehicle speeds on the 4th direct gear ratio of the transmission (static conditions), specifically at steady engine speeds corresponding to 50 km/h (approx. 1580 rpm) and 90 km/h (approx. 2860 rpm). Dynamic conditions were reproduced by measuring the engine’s maximum torque, which occurred during the acceleration phase. In the course of the study, the fundamental operating parameters of the engine were recorded, including engine power, torque and selected dynamic variables, at a high sampling frequency. The control system operated in its factory configuration, without any interference in the ECU software (SW version: 3044QA05), which allowed for the evaluation of the engine’s actual response to the applied fuel. Exhaust emission measurements were carried out in the exhaust line upstream of the aftertreatment system, such as the catalytic converter and diesel particulate filter, ensuring that the obtained results reflected solely the influence of the combustion process of the tested fuel blends on pollutant formation. This approach enabled an unambiguous assessment of the impact of the alternative fuels on the injection and combustion process, as well as on the generation of key exhaust components.

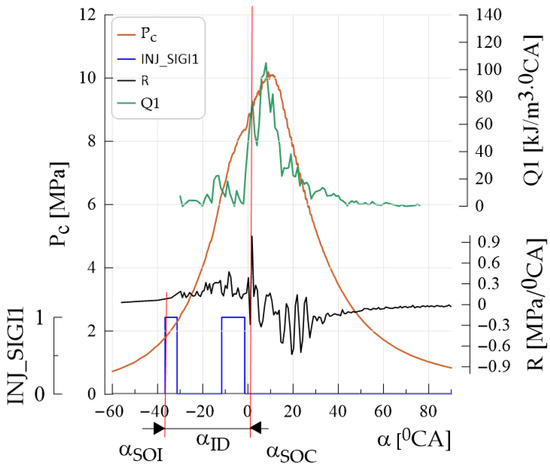

The main evaluated parameters and their graphical interpretation are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A graphical representation of the parameters required to determine the self-ignition angle is provided, including αSOI (start of injection), αSOC (start of combustion) and αID (ignition delay). The figure also illustrates the progression of the main injection event and key combustion characteristics, such as the heat release rate (Q1), heat generation profiles (I1), in-cylinder pressure (Pc), rate of pressure rise (R) and the injector control signal (INJ_SIGI1).

- Power—engine power [kW];

- Torque—engine torque [nm];

- MEP—indicated mean effective pressure [MPa];

- Pmax—maximum combustion pressure (Pcyl1) [MPa];

- R—pressure rise rate (Pcyl1_der) [MPa/0CA];

- ID—ignition delay [0CA];

- SOC—start of combustion [0CA];

- SOI—start of injection [0CA];

- 1I—heat discharge [kJ/m3];

- Q1—heat release rate [kJ/m3∙0CA].

During the tests, environmental (emission) parameters were recorded:

- CO—carbon monoxide: a toxic gas formed as a result of incomplete fuel combustion;

- CO2—carbon dioxide: the main product of hydrocarbon fuel combustion, an indicator of combustion efficiency;

- NO—nitric oxide: one of the main components of NOx, formed at high combustion temperatures;

- NO2—nitrogen dioxide: a component of NOx and a highly toxic gas;

- NOx—sum of nitrogen oxides (NO + NO2): a key regulated emission parameter;

- O2—oxygen: a basic component of air; its concentration in exhaust gases is used to assess combustion efficiency and to analyze the air–fuel ratio (λ).

2.2.2. Surface Tension Measurements

The equilibrium surface tension ) was determined using the Du Noüy ring method with a K9 tensiometer (Krüss, Hamburg, Germany). Prior to testing, the instrument was calibrated with water ( = 72.8 mN/m at 293.15 K) and methanol ( = 22.5 mN/m at 293.15 K). Before each measurement, the ring was rinsed with distilled water and heated to red-hot using a Bunsen burner. For every sample, more than ten consecutive readings were taken, with a standard deviation of ±0.1 mN/m. Temperature control was maintained using a jacketed vessel connected to a thermostatic water bath, providing an accuracy of ±0.01 K.

2.2.3. Density Measurements

Density (d) was determined at 293.15 K using a U-tube densitometer (DMA 5000, Anton Paar, Graz, Austria). According to the manufacturer, the device provides a repeatability of 1 × 10−5 g/cm3 for ultrapure water, with a temperature control precision of ±0.001 K. The instrument was calibrated before taking measurements. The uncertainty of the density measurements was 0.000002 g/cm3, and the standard deviation was ±0.0003.

2.2.4. Viscosity Measurements

Viscosity (η) was measured at 293.15 K using U-tube glass capillary viscometers (130 A Visco3, Huber Kaltemaschinenbau AG, Offenburg, Germany). The flow time of a fixed volume of liquid passing through the capillary under gravity was recorded. The capillary constant was 0.02981 mm2/s2. Viscosity values for the tested liquids and mixtures were calculated from a calibration curve generated using model liquids—formamide, oleic acid and glycerol—with known viscosities [46]. The measurements were performed with an accuracy of ±0.0001 mPa·s and an uncertainty of 0.0002 mPa·s, and the standard deviation was ±0.003.

For each mixture, three consecutive density and viscosity measurements were taken. Before conducting these measurements, both the densitometer and the viscometer were calibrated with distilled and deionized water, as well as methanol [52].

2.2.5. Contact Angle Measurements

Advancing contact angles (θ) on PTFE and the engine valve were determined using the sessile drop technique with a DSA30 measuring system (Krüss, Hamburg, Germany) inside a temperature-controlled chamber set to 293.15 ± 0.1 K. For each liquid, multiple drops were placed on the same solid surface, and at least 20 drops were analyzed to obtain the contact angle. The measurements showed good consistency, with the standard deviation for each data set being below 1.2.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Properties of Fuel Mixtures

The viscosity, density and surface tension of Ro depend on the intermolecular interactions of its components. According to van Oss et al. [53,54,55,56], these interactions can be divided into three groups. The most important are the Lifshitz–van der Waals interactions (LW), which are present in all substances. These interactions consist of the combined effects of dispersion forces, dipole–dipole interactions and induced dipole–dipole interactions. According to van Oss and co-workers [53,54,55,56], the dipole–dipole and induced dipole–dipole contributions account for less than 2% of the overall Lifshitz–van der Waals interactions in condensed phases. Hence, it can be assumed that in these phases the contribution of the LW interactions to the total ones is close to that of dispersion. Apart from LW, the total intermolecular interactions include acid–base (AB) interactions, related to the formation of hydrogen bonds and electrostatic (EL) ones. The surface tension of liquids and solids arises from the LW, AB and EL intermolecular forces acting at their interfaces, all of which depend on the distance between molecules. For rapeseed oil (Ro) and its constituents, the surface tension is governed primarily by LW and AB interactions [53,54,55,56,57,58]. However, the contribution of LW interactions to rapeseed oil and its components’ surface tension is considerably higher than AB ones [59]. For the same types of chemical groups, the interaction between them can have a different contribution to the surface tension of a given substrate depending on the distance between these groups. In the case of dispersion forces, a small decrease in the distance between chemical groups and/or small molecules can cause a big increase in these forces [59]. Of course, the change in the distance between chemical groups or small molecules strongly influences not only the surface tension of the given substrate but also its density and viscosity. The dispersive interactions, according to van Oss and Constanzo [54], assume maximum values at a distance of 1.56 Å, and they decrease rapidly with increasing intermolecular distance. This distance for most organic compounds in the liquid phase at 293.15 K is 2 Å. This results from the density of the given compound and its molecular volume.

Previous work [60] demonstrated that the molecular volume of a substance can be estimated from the bond lengths between specific atoms, the angles between those bonds and the average spacing between molecules by positioning the molecules or their fragments within an appropriately sized cubic framework. It appeared that the density of a given substance calculated in this way and its molar weight are comparable to the density determined in other ways [61,62]. Moreover, it also appeared that, at 293.15 K, the average distance between n-alkane molecules and alkyl groups in the hydrocarbon surfactants is close to 2 Å. Taking into account this concept of determining a molecule of a given substance, the density of the components of rapeseed oil was established and compared to that established in a different way [47]. It appeared that there is agreement between the values of density determined by different methods.

Because the viscosity depends directly on the pressure, this means that the decreased distance between the molecules of the Ro components, in comparison to that in single compounds, increases the interactions force, and viscosity increases. Therefore, to adjust some physicochemical properties of rapeseed oil to Df, it is necessary to add substances that not only have lower values of these properties but that have the ability to increase the distance between the oil component molecules.

It appeared that such a condition was fulfilled by the additives n-hexane (Hex) and ethanol (Et). The 10% n-hexane content in rapeseed oil reduces its viscosity more than three times (Table 2). Increasing the Hex content in Ro to 15% does not change its viscosity much (Table 2).

Table 2.

The physicochemical properties for Ro, Hex, Et, Df and the RoHex10, RoHex15, RoHex10+Et2, RoHex15+Et2, RoHex10/Et and RoHex15/Et mixtures [46,47,48].

Despite the fact that the viscosity of n-hexane is low and, at 293.15 K, is equal to only 0.3101 mPa s, the decrease in the viscosity of Ro is greater with the addition of n-hexane equal to 10 and 15% of its content than would appear in an ideal mixture. This means that the Hex influences the distance between the molecules of the fatty acids in the rapeseed oil. Unfortunately, the viscosity of rapeseed oil, even with 15% n-hexane, is much higher than that of diesel fuel (Table 2). A further decrease in the viscosity of Ro is observed when ethanol is added to the Ro+Hex mixture. Even a 2% ethanol content in a mixture of n-hexane with Ro containing 10% and 15% Hex decreases the viscosity of this mixture (Table 2). However, this decrease is not so significant that it can be clearly determined whether it results from the low viscosity of ethanol (1.2 mPa s) or is also based on the variation in the average spacing between the molecules that make up the mixture. An interesting fact is that, if Et is not added to the mixture of Ro and Hex but is contacted with this mixture, the decrease in the viscosity of the Ro+Hex mixture is greater (Table 2). The value of this viscosity at a 15% n-hexane content is only slightly more than twice that of diesel fuel (Table 2). Obviously, during the contact of the alcoholic phase with the Ro+Hex mixture, there is an exchange of substances between these phases. It cannot be ruled out that not only n-hexane but also fatty acid molecules go into the alcohol phase. It is possible that, as a result of such a transition, there is a greater increase in the average distance between the molecules of the components of the mixture than with the addition of alcohol to the mixture of n-hexane and rapeseed oil.

Changes in the density of rapeseed oil, which is greater than that of diesel fuel, due to the addition of n-hexane and ethyl alcohol to this oil are not as pronounced as the changes in viscosity [47,48] (Table 2).This indicates that adding n-hexane and ethanol to rapeseed oil alters not only the average spacing between the molecules in the mixture but also the strength of the interactions between fatty acid molecules that are separated by Hex and Et molecules. This interpretation is supported by the observed changes in the surface tension of rapeseed oil when modified with n-hexane and ethanol (Table 2).

It is worth noting that the surface tensions of rapeseed oil, n-hexane and ethanol, as well as the density values of these substances, indicate the non-ideal behavior of the Ro+Hex+Et mixture. The addition of n-hexane and ethanol to rapeseed oil can change not only its total surface tension but also the LW and AB components of this tension. The LW component of the studied mixtures’ surface tension can be calculated based on the contact angle of these mixtures on the PTFE surface (Table 2). It is interesting that the value of the contact angle () of the mixture of rapeseed oil with 10% n-hexane (RoHex10) on the PTFE surface is lower than that of rapeseed oil and close to the contact angle value of diesel fuel (Table 2). Increasing the amount of n-hexane in the mixture, as well as adding ethanol, did not affect the contact angle. It is worth noting that n-hexane spreads fully across the PTFE surface, while ethanol produces a much smaller contact angle compared with rapeseed oil (Table 2).

For the calculation of the LW component of the rapeseed oil, as well as its mixtures with n-hexane and ethanol, the following equation was applied [53,54,55,56]:

where is the Lifshitz–van der Waals component of the liquid surface tension, and is the Lifshitz–van der Waals components of the solid surface tension.

Of course, the acid–base component of the liquid surface tension is equal to . According to van Oss et al. [53,54,55,56], Equation (1) is fulfilled if or , as well as both of the values, results only from the Lifshitz–van der Waals intermolecular interactions and practically from dispersion forces. For the systems under study, the surface tension of PTFE arises solely from the Lifshitz–van der Waals intermolecular forces.

The values of LW and the AB components calculated from Equation (1) are rather unexpected (Table 2). Indeed, the LW component of the surface tension for the rapeseed oil mixtures containing 10% and 15% n-hexane (Table 2) is significantly lower than that of pure rapeseed oil, which appears to align with the fact that n-hexane’s surface tension arises solely from LW intermolecular interactions.

On the other hand, the AB component of the surface tension (Table 2) is greater than that of the oil itself, which is difficult to justify. The addition of ethanol causes an increase in the LW component of the surface tension but a decrease in the AB one. Taking into account the LW component of ethanol surface tension, which is higher than that of n-hexane, it is reasonable that the LW component of the rapeseed oil mixture with n-hexane and ethanol can be higher than that of the Ro mixture only with Hex. However, unlike n-hexane, ethanol has a nonzero AB component in its surface tension, and the AB component of the rapeseed oil mixture containing both n-hexane and ethanol is lower than that of the mixture with n-hexane alone.

When using Equation (1) to calculate the LW component of a solution’s surface tension, it should be noted that only the vapors of solution components with a surface tension higher than that of PTFE do not reduce its surface tension. Unfortunately, the surface tension of the n-hexane that is the component of the studied mixtures is not lower than the surface tension of PTFE (Table 2). In such case, Equation (1) assumes the following form:

where is the adsorbed layer pressure.

The maximum π value for n-hexane, defined as the difference between the surface tension of PTFE (20.24 mN/m [63]) and that of n-hexane, is 1.75 mN/m. Taking into account this value, the LW component of rapeseed oil mixtures with n-hexane and ethanol surface tension was calculated. It appeared that, for each mixture, the value of LW is insignificantly higher than the surface tension. This means that the value is lower than 1.75 mN/m but higher than zero, and the presence of n-hexane in the mixture decreases not only the LW but also the AB components of the rapeseed oil surface tension.

Based on the calculations, it can be inferred that the AB interactions in the rapeseed oil mixture with n-hexane and ethanol are comparable to those in diesel fuel. During the spreading of the mixture over the PTFE surface, an initial adsorbed layer appears to form. This spreading behavior likely occurs on engine components as well, as indicated by the contact angle measurements on the engine valve (Table 2).

3.2. Engine Test—Results

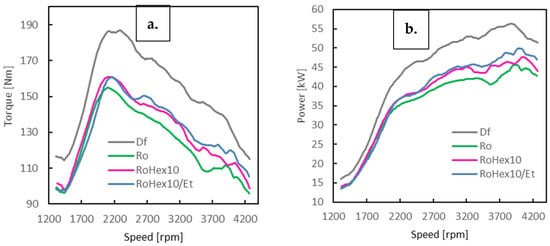

The mixtures RoHex10 and RoHex10/Et were selected for further research, since both the authors’ previous studies and the conducted physicochemical analyses clearly indicated that increasing the n-hexane content above 10% vol. does not lead to significant changes in the characteristics of the tested fuels. In particular, no notable improvement in energy-related parameters nor reduction in the emission of harmful exhaust components was observed. For this reason, continuing investigations with mixtures containing higher amounts of n-hexane were considered unjustified, and the optimal scope of further analyses was limited to a level ensuring stable rheological properties and full comparability with the reference fuels. The main findings of the study are presented in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 3.

Power (a) and torque (b) characteristics as a function of engine speed for the diesel engine fueled with Df, Ro, RoHex10 and RoHex10/Et.

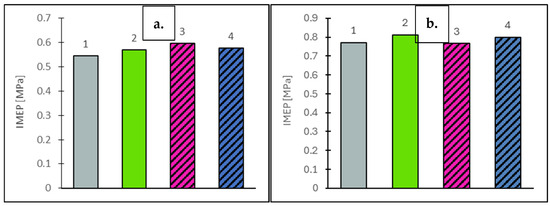

Figure 4.

Indicated mean effective pressure (IMEP) values at vehicle speeds of 50 km/h (a) and 90 km/h (b) for the engine supplied with the tested fuels: Df (bar 1), Ro (bar 2), RoHex10 (bar 3) and RoHex10/Et (bar 4).

Figure 5.

Maximum combustion pressure (Pmax) values at vehicle speeds of 50 km/h (a) and 90 km/h (b) for the engine supplied with the tested fuels: Df (bar 1), Ro (bar 2), RoHex10 (bar 3) and RoHex10/Et (bar 4).

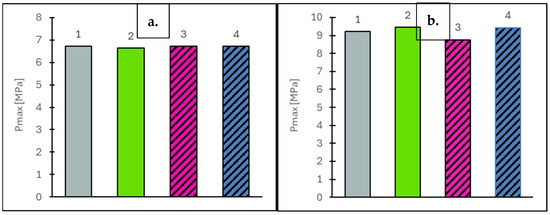

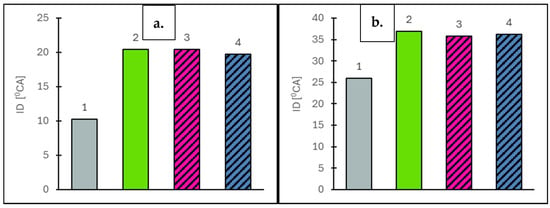

Figure 6.

Ignition delay (ID) values at vehicle speeds of 50 km/h (a) and 90 km/h (b) for the engine operating on the tested fuels: Df (bar 1), Ro (bar 2), RoHex10 (bar 3) and RoHex10/Et (bar 4).

During the engine operating tests (Figure 3, Table 3), the maximum torque and power outputs were identified. For diesel fuel (Df), the highest recorded values reached 186.9 Nm at 2235 rpm and 56.3 kW at 3849 rpm. When diesel was replaced with refined rapeseed oil, these parameters decreased to 155.8 Nm at 2102 rpm and 45.7 kW at 3907 rpm, forming the reference baseline for further comparisons. For the blend containing 10% n-hexane (RoHex10), an improvement in performance was observed: torque increased to 161.0 Nm at 2116 rpm, while power rose to 47.7 kW at 4035 rpm. This corresponds to an increase of approximately 3.3% in torque and 4.4% in power relative to pure rapeseed oil. The RoHex10/Et fuel—comprising rapeseed oil with 10% n-hexane contacted with ethanol—achieved 160.8 Nm at 2165 rpm and 50.7 kW at 3989 rpm, representing gains of around 3.2% in torque and 10.9% in power compared to Ro.

Table 3.

Maximum torque and peak engine power measured during chassis dynamometer testing.

It should be noted, however, that every rapeseed oil-derived fuel variant (Ro, RoHex10, RoHex10/Et) delivered lower torque and power outputs than conventional diesel fuel. These differences are mainly attributed to the distinct physicochemical properties of biofuels, including their lower calorific value and different combustion behavior. The analysis confirms that the addition of n-hexane improves the usability of rapeseed oil as an alternative fuel, and that the contact with ethanol (RoHex10/Et) further enhances engine power—likely due to the modified physicochemical characteristics of the mixture. A clear influence of fuel composition on torque, power output and acceleration was observed.

Based on the results obtained from engine tests under both static and dynamic conditions, it was found that the addition of 10% n-hexane to rapeseed oil, as well as 10% n-hexane contacted with ethanol, did not significantly affect the fuel pressurization and injection processes. This was primarily due to the design of the engine’s fuel injection system and its control algorithm. Additionally, the aforementioned mixtures did not cause any significant changes in the fuel pressure values measured upstream of the injectors. Based on the engine tests conducted under static conditions corresponding to vehicle speeds of 50 km/h and 90 km/h, it was found that the indicated mean effective pressure (IMEP) had the greatest influence on the energy performance parameters of the tested fuels. The measured IMEP values are presented in Figure 4. The test results showed that, at a lower vehicle speed (50 km/h), all rapeseed oil-based fuels (Ro, RoHex10, RoHex10/Et) exhibited higher IMEP values compared to diesel fuel. The highest value was recorded for RoHex10 (0.597 MPa), which represents an increase of +4.9% compared to Ro (0.569 MPa), +3.3% compared to RoHex10/Et (0.578 MPa) and +9.5% compared to Df (0.545 Mpa). Importantly, diesel fuel showed the lowest IMEP value among all tested fuels at this speed. At a higher vehicle speed (90 km/h), a similar trend was observed—the IMEP for Df (0.772 MPa) was again the lowest, while the highest value was achieved with Ro (0.813). The differences compared to diesel were as follows: +5.3% for Ro, +3.6% for RoHex10/Et (0.800 MPa) and −0.5% for RoHex10 (0.768 MPa), which was the only rapeseed-based mixture with a slightly lower IMEP than Df at this speed. All rapeseed oil-based fuels (with the exception of RoHex10 at 90 km/h) provided a higher indicated mean effective pressure than diesel fuel, confirming their favorable energy performance under static operating conditions. The addition of n-hexane—especially when combined with ethanol—had a positive effect on the combustion process, particularly at lower vehicle speeds. This effect was related to the pressure development in the combustion chamber, with the maximum combustion pressures shown in Figure 5, which followed a trend similar to that observed for IMEP.

Based on the conducted tests, it was found that the addition of n-hexane and ethanol in the form of a contacted mixture, RoHex10/Et, contributed to a reduction in ignition delay (ID) compared to pure rapeseed oil, particularly under lower engine speeds, corresponding to vehicle speeds of 50 km/h and 90 km/h. Both the direct addition of n-hexane (RoHex10) and the contact with ethanol (RoHex10+Et) showed a favorable effect on the ignition characteristics by slightly reducing the time required for fuel ignition. However, despite the improvements, all rapeseed-based fuels exhibited significantly longer ignition delay times compared to diesel fuel. This highlights the superior autoignition properties of diesel, which ignites more readily under compression due to its lower ignition delay and higher cetane number. A vehicle speed of 50 km/h achieves the following values: Df (10.25 deg); Ro (20.41 deg); RoHex10 (20.42 deg—virtually unchanged vs. Ro); and RoHex10/Et (19.71 deg values lower by −3.4% vs. Ro). A vehicle speed of 90 km/h achieves the following values: Df (25.97 deg); Ro (36.88 deg); RoHex10 (35.77deg values lower by −3.0% vs. Ro); and RoHex10/Et (36.21 deg values lower by −1.8% vs. Ro).

Diesel fuel showed the shortest ignition delay among all tested fuels—at both 50 km/h and 90 km/h—confirming its high ignition quality. The addition of n-hexane slightly improved the ignition behavior of rapeseed oil, although the reduction in delay was modest. The RoHex10/Et mixture, which included ethanol contact, provided the largest reduction in ignition delay relative to Ro, indicating that ethanol also contributes positively to improving ignition reactivity. Nevertheless, the ID values for all bio-based fuels remained significantly higher than those for diesel, with more than double the ignition delay in most cases. The results of the auto-ignition delay are shown in Figure 6.

The generation of toxic exhaust components is an inherent consequence of the combustion process. Among the main products of complete combustion is carbon dioxide. However, a local deficiency of oxygen leads to incomplete combustion, resulting in the additional formation of carbon monoxide in the exhaust gases. Nitrogen oxides (NOx) are produced during combustion, and their formation is strongly correlated with the combustion temperature, the presence of oxygen and the nitrogen content of the fuel. These compounds are generated as a result of rapid reactions between oxygen and nitrogen atoms at high temperatures.

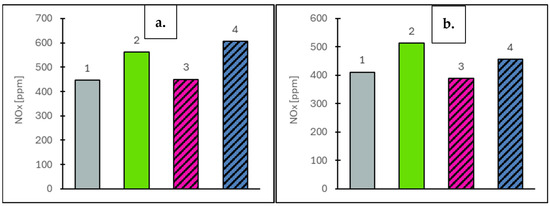

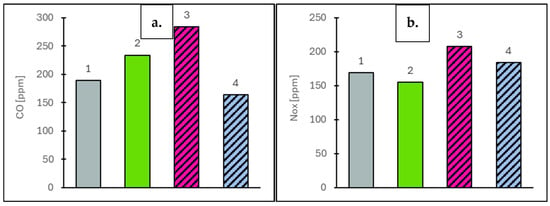

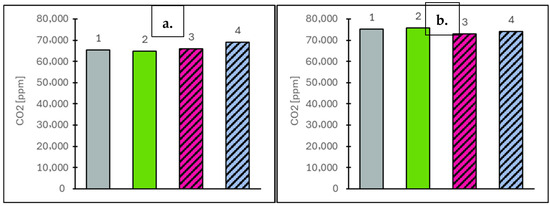

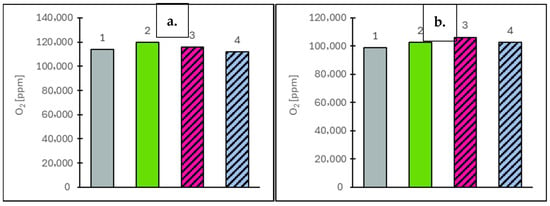

For the concentration of selected gaseous components, measurements were taken at two vehicle speeds: 50 km/h and 90 km/h. The EGR valve remained closed throughout, ensuring that the measured values reflected only the natural combustion characteristics of each fuel. The analysis focused on toxic components (NOx, CO), the greenhouse gas CO2 and oxygen (O2) as an indicator of combustion efficiency. For nitrogen oxides (NOx), which are primarily formed through high-temperature reactions between nitrogen and oxygen, concentrations were strongly dependent on combustion conditions. At 50 km/h, the highest NOx value was observed for RoHex10/Et at 607 ppm (8.0% higher than the value obtained for Ro). RoHex10 reached 450 ppm (19.9% lower than Ro) and Df showed 446 ppm (20.7% lower than Ro). At 90 km/h, a similar trend was observed: RoHex10/Et reached 457 ppm (10.9% lower than Ro), RoHex10 dropped to 389 ppm (24.2% lower) and Df dropped to 411 ppm (19.9% lower than Ro, which reached 513 ppm). The results of NOx concentration in the flue gas are shown in Figure 7. Carbon monoxide (CO), a toxic product of incomplete combustion, also varied with fuel type. At 50 km/h, RoHex10 recorded the highest CO concentration—284 ppm (21.4% higher than Ro)—while RoHex10/Et showed only 164 ppm (29.9% lower than Ro) and Df reached 189 ppm (19.2% lower than Ro). At 90 km/h, the highest CO levels were again found in RoHex10 (208 ppm, 34.2% higher than Ro), followed by RoHex10/Et (184 ppm, 18.7% higher than Ro). Df produced 169 ppm, which was 9.7% lower than Ro (155 ppm). The results of CO concentration in the flue gas are shown in Figure 8. As for carbon dioxide (CO2)—the main greenhouse gas and a key product of complete combustion—the highest value at 50 km/h was recorded for RoHex10/Et at 68.884 ppm (6.5% higher than Ro). RoHex10 reached 65.802 ppm (1.7% higher than Ro) and Df reached 65.299 ppm (0.9% higher than Ro). At 90 km/h, the highest CO2 level was found in Df—75.265 ppm (0.7% lower than Ro)—while RoHex10 had 72.997 ppm (3.7% lower than Ro) and RoHex10/Et had 73.953 ppm (2.4% lower than Ro). The results of CO2 concentration in the flue gas are shown in Figure 9. For the oxygen (O2) remaining in the exhaust, interpreted as an indicator of unutilized air, the highest concentrations were found in Ro—11.97% at 50 km/h and 10.26% at 90 km/h. RoHex10 recorded 11.58% (3.3% lower than Ro) and 10.63% (3.6% higher than Ro) and RoHex10/Et had 11.18% (6.6% lower than Ro) and 10.27% (0.1% higher than Ro), while Df recorded 11.37% (5.0% lower than Ro) and 9.89% (3.6% lower than Ro). The results of O2 concentration in the flue gas are shown in Figure 10. From the analysis, it can be concluded that RoHex10 generally produced the lowest NOx concentrations but also the highest CO emissions, indicating a less intense and less efficient combustion process. Diesel fuel demonstrated the most efficient combustion overall, with the lowest NOx and CO and slightly higher CO2, as well as the least residual O2. In contrast, Ro (pure rapeseed oil) ranked in the middle across most parameters. It produced the highest NOx, but lower CO than the modified blends, and left the most oxygen in the exhaust, possibly indicating a lower combustion intensity within the cylinder.

Figure 7.

Nitrogen oxide (NOx) values at vehicle speeds of 50 km/h (a) and 90 km/h (b) for the engine operating on the tested fuels: Df (bar 1), Ro (bar 2), RoHex10 (bar 3) and RoHex10/Et (bar 4).

Figure 8.

Carbon monoxide (CO) values at vehicle speeds of 50 km/h (a) and 90 km/h (b) for the engine operating on the tested fuels: Df (bar 1), Ro (bar 2), RoHex10 (bar 3) and RoHex10/Et (bar 4).

Figure 9.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) values at vehicle speeds of 50 km/h (a) and 90 km/h (b) for the engine operating on the tested fuels: Df (bar 1), Ro (bar 2), RoHex10 (bar 3) and RoHex10/Et (bar 4).

Figure 10.

Oxygen (O2) values at vehicle speeds of 50 km/h (a) and 90 km/h (b) for the engine operating on the tested fuels: Df (bar 1), Ro (bar 2), RoHex10 (bar 3) and RoHex10/Et (bar 4).

The injection system control algorithm maintained a constant start of injection (SOI) angle for all tested fuels, and the addition of n-hexane did not cause significant deviations in this respect. Similar relationships were observed for the boost pressure and the amount of air supplied to the cylinders, which indicates that the engine filling conditions remained comparable. Consequently, achieving the required torque was primarily a function of the injected fuel dose and the resulting combustion characteristics. In practice, with an identical driver wish signal (accelerator pedal position) and a constant SOI angle, the engine control unit (ECU) adjusted the injected fuel quantity by modifying the injector opening duration. Differences in the physicochemical properties of the fuels—such as viscosity, density, volatility and ignition quality—meant that, in order to achieve the same torque value, it was necessary to lengthen or shorten the injection duration accordingly.

Based on the analysis of one hundred consecutive engine cycles, the mean injection durations were determined for each fuel at vehicle speeds of 50 km/h and 90 km/h. At 50 km/h, the values were as follows: diesel fuel—566 µs; rapeseed oil—704 µs; RoHex10 blend—663 µs; and RoHex10/Et—642 µs. At 90 km/h, the corresponding values were the following: Df—513 µs; Ro—612 µs; RoHex10—580 µs; and RoHex10/Et—562 µs. These results clearly show that, for vegetable-based fuels, due to their lower energy efficiency and different physicochemical properties, the ECU compensated for the differences by extending the injection duration compared to diesel fuel. At the same time, the beneficial effect of rapeseed oil modification was evident—the addition of n-hexane, and particularly the RoHex10/Et blend, reduced the injection time compared to pure rapeseed oil, indicating improved atomization and combustion processes. The closest values to diesel fuel were obtained for RoHex10/Et, confirming its positive impact on the injection characteristics and its potential to ensure more stable engine operations. Consequently, obtaining comparable torque values at 50 km/h and 90 km/h was directly dependent on the ability of the tested fuel to effectively form the air–fuel mixture and ensure proper combustion development. It was therefore the fuel properties that determined the differences in injection duration required to achieve a stable and comparable engine operation. It should also be added that the surface tension directly affects liquid atomization because it is the primary force that prevents liquids from breaking up into smaller droplets. The higher the surface tension, the more difficult it is to break them up, leading to larger, more compact droplets. Reducing the surface tension (e.g., by adding a low-surface-tension liquid) facilitates atomization, resulting in the formation of smaller and more numerous droplets. Taking into account the facts mentioned above, it can be stated that RoHex10/Et could serve as a pre-commercial biofuel mixture after cetane optimization.

4. Conclusions

This study evaluated the suitability of rapeseed oil modified with n-hexane and ethanol as an alternative diesel fuel through physicochemical measurements and engine testing on a production vehicle. A mixture of rapeseed oil and n-hexane in contact with ethanol significantly approaches the viscosity, surface tension and density of diesel fuel. The RoHex10/Et mixture has the best physicochemical properties in terms of its practical application as a biofuel. For this mixture, the values of the mean effective pressure and engine torque were similar to those of diesel fuel. However, this mixture also produced markedly higher total hydrocarbon emissions due to the incomplete combustion associated with its lower cetane number and limited ignition quality.

The obtained results confirm that the proposed modification of the physicochemical properties of rapeseed oil is a promising method for improving crude vegetable oils without transesterification, offering benefits in terms of cost, simplicity and sustainability. Future research should focus on optimizing the ethanol content, applying effective ignition improvers and precisely tuning injection parameters, which would help reduce unfavorable environmental characteristics. The study contributes to the growing body of research supporting the transition toward low-emission, renewable and engine-compatible bio-derived fuels. The RoHex10/Et mixture, after optimizing the cetane-enhancing additive and repeating the tests, may serve as a good alternative to fossil fuels as a pre-commercial biofuel capable of operating in diesel engines without the need for major modifications to the fuel system.

Author Contributions

P.S., R.L., B.J., A.Z. and K.S.—signed the experiments, analyzed the experimental data, made figures, participated in the preparation of the manuscript and wrote the part of the manuscript; P.S., R.L., B.J., A.Z., K.S., K.G. and J.M.—conceived the concept of the studies, wrote the main part of the manuscript, supervised the studies and participated in the manuscript preparation, signed the experiments, analyzed the experimental data and made figures; P.S., R.L., B.J., A.Z. and K.S.—writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cotterman, T.; Fuchs, E.R.H.; Whitefoot, K.S.; Combemale, C. The Transition to Electrified Vehicles: Evaluating the Labor Demand of Manufacturing Conventional versus Battery Electric Vehicle Powertrains. Energy Policy 2024, 188, 114064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Rojas, J.C.; Costa-Castelló, R.; Flores-Campos, J.A.; Torres-San Miguel, C.R. Experimental Study on Using Biodiesel in Hybrid Electric Vehicles. Energies 2025, 18, 7162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sens, M. Hybrid Powertrains with Dedicated Internal Combustion Engines Are the Perfect Basis for Future Global Mobility Demands. Transp. Eng. 2023, 13, 100146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Biswas, A.; Rodriguez, R.; Keshavarz-Motamed, Z.; Emadi, A. Hybrid Electric Vehicle Specific Engines: State-of-the-Art Review. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 832–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabi, M.; Saha, U.K. Application Potential of Vegetable Oils as Alternative to Diesel Fuels in Compression Ignition Engines: A Review. J. Energy Inst. 2019, 92, 1710–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuortila, C.; Help, R.; SirviÃ, K.; Suopanki, H.; HeikkilÃ, S.; Niemi, S. Selected Fuel Properties of Alcohol and Rapeseed Oil Blends. Energies 2020, 13, 3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, G.; Płochocki, P.; Simiński, P.; Skrzek, T. The Experimental Verification of the Multi-Fuel IC Engine Concept with the Use of Jet Propellant-8 (JP-8) and Its Blends with Pure Rapeseed Oil. Int. J. Energy Environ. Eng. 2021, 12, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, G.; Skrzek, T. Combustion of Raw Camelina Sativa Oil in CI Engine Equipped with Common Rail System. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado-Deblas, L.; Estevez, R.; Hidalgo-Carrillo, J.; Bautista, F.M.; Luna, C.; Calero, J.; Posadillo, A.; Romero, A.A.; Luna, D. Outlook for Direct Use of Sunflower and Castor Oils as Biofuels in Compression Ignition Diesel Engines, Being Part of Diesel/Ethyl Acetate/Straight Vegetable Oil Triple Blends. Energies 2020, 13, 4836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado-Deblas, L.; Hidalgo-Carrillo, J.; Bautista, F.M.; Luna, C.; Calero, J.; Posadillo, A.; Romero, A.A.; Luna, D.; Estévez, R. Evaluation of Dimethyl Carbonate as Alternative Biofuel. Performance and Smoke Emissions of a Diesel Engine Fueled with Diesel/Dimethyl Carbonate/Straight Vegetable Oil Triple Blends. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Zhang, X.; Han, W.; Geng, Z.; Tessa Margaret Thomas, M.; Dankwa Jeffrey, A.; Wang, G.; Ji, J.; Liu, H. Macro and Micro Solubility between Low-Carbon Alcohols and Rapeseed Oil Using Different Co-Solvents. Fuel 2020, 270, 117511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado-Deblas, L.; López-Tenllado, F.J.; Luna, D.; Bautista, F.M.; Romero, A.A.; Estevez, R. Advanced Biofuels from ABE (Acetone/Butanol/Ethanol) and Vegetable Oils (Castor or Sunflower Oil) for Using in Triple Blends with Diesel: Evaluation on a Diesel Engine. Materials 2022, 15, 6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddada, Y.; Ravia, R.; Belkasmia, M.; Faqira, M.; Essadiqia, E.; Liub, Q.; Yubrajb, P. Valorization of orange waste for high-performance biodiesel: A comprehensive technical review. Int. J. Green Energy 2025, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadivelu, T.; Ramanujam, L.; Ravi, R.; Vijayalakshmi, S.K.; Ezhilchandran, M. An Exploratory Study of Direct Injection (DI) Diesel Engine Performance Using CNSL—Ethanol Biodiesel Blends with Hydrogen. Energies 2023, 16, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, D. Biofuels from Renewable Sources, a Potential Option for Biodiesel Production. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharia, P.; Saini, R.; Kudapa, V.K. A study on various sources and technologies for production of biodiesel and its efficiency. MRS Energy Sustain. 2023, 10, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, K.; Capareda, S.C.; Kamboj, B.R.; Malik, S.; Singh, K.; Arya, S.; Bishnoi, D.K. Biofuels Production: A Review on Sustainable Alternatives to Traditional Fuels and Energy Sources. Fuels 2024, 5, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Narayanan, I.; Selvaraj, R.; Varadavenkatesan, T.; Vinayagam, R. Biodiesel production from microalgae: A comprehensive review on influential factors, transesterification processes, and challenges. Fuel 2024, 367, 131547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Jaryal, S.; Sharma, S.; Dhyani, A.; Tewari, B.S.; Mahato, N. Biofuels from Microalgae: A Review on Microalgae Cultivation, Biodiesel Production Techniques and Storage Stability. Processes 2025, 13, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.A.I.; Zeeshan, S.; Khubaib, M.; Ikram, A.; Hussain, F.; Yassin, H.; Qazi, A. A review of major trends, opportunities, and technical challenges in biodiesel production from waste sources. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 23, 100675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadbakht, M.; Safieddin Ardebili, S.; Rahmani, M. A study on biodiesel production using agricultural wastes and animal fats. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2023, 13, 4893–4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S.; Kumar, D.; Singh, B.; Sachan, P.K. Biofuels and their sources of production: A review on cleaner sustainable alternative against conventional fuel, in the framework of the food and energy nexus. Energy Nexus 2021, 4, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, R.; Liu, J.J. A strategy for advanced biofuel production and emission utilization from macroalgal biorefinery using superstructure optimization. Energy 2021, 221, 119883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Naushad, M.; Iqbal, J.; Bathula, C.; AL-Muhtaseb, A.H. Challenges and Perspectives on Innovative Technologies for Biofuel Production and Sustainable Environmental Management. Fuel 2022, 325, 124845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisti, Y. Biodiesel from Microalgae. Biotechnol. Adv. 2007, 25, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigam, P.S.; Singh, A. Production of Liquid Biofuels from Renewable Resources. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2011, 37, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastianoni, S.; Coppola, F.T.; Colacevicin, A.; Borghini, F.; Focardi, S. Biofuel Potential Production from the Orbetello Lagoon Macroalgae: A Comparision with Sunflower Feedstock. Biomass Bioenergy 2008, 32, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakopoulos, D.C.; Rakopoulos, C.D.; Giakoumis, E.G.; Dimaratos, A.M.; Founti, A.M. Comparative environmental behavior of bus engine operating on blends of diesel fuel with four straight vegetable oils of Greek origin: Sunflower, cottonseed, corn and olive. Fuel 2011, 90, 3439–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Dinesha, P. Use of alternative fuels in compression ignition engines: A review. Biofuels 2017, 10, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabi, O.O.; Ogunwoye, F.O.; Gbadeyan, O.J.; Fasina, A.O.; Deenadayalu, N. Exploring the impact of diesel-vegetable oil blends as an alternative fuel in combustion chambers. Biofuels 2024, 16, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balat, M.; Balat, H. Progress in Biodiesel Processing. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 1815–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borugadda, V.B.; Somidi, A.K.R.; Dalai, A.K. Chemical/Structural Modification of Canola Oil and Canola Biodiesel: Kinetic Studies and Biodegradability of the Alkoxides. Lubricants 2017, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.C.; Yoon, S.K.; Choi, N.J. Using Canola Oil Biodiesel as an Alternative Fuel in Diesel Engines: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.C.; Yoon, S.K.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, N.J. Application of Canola Oil Biodiesel/Diesel Blends in a Common Rail Diesel Engine. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezki, B.; Essamlali, Y.; Aadil, M.; Semlal, N.; Zahouily, M. Biodiesel Production from Rapeseed Oil and Low Free Fatty Acid Waste Cooking Oil Using a Cesium Modified Natural Phosphate Catalyst. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 41065–41077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.M.; Wang, W.; Bujold, J. Biodiesel Production and Comparison of Emissions of a DI Diesel Engine Fueled by Biodiesel-Diesel and Canola Oil-Diesel Blends at High Idling Operations. Appl. Energy 2013, 106, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.H.; Bae, C.; Feng, Y.M.; Jia, C.C.; Bian, Y.Z. Preparation, Characterization, Engine Combustion and Emission Characteristics of Rapeseed Oil Based Hybrid Fuels. Renew Energy 2013, 60, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, K.P.; Singh, R.N. A Technical Review on Performance and Emission Characteristics of Diesel Engine Fueled with Straight Vegetable Oil. Curr. World Environ. 2023, 18, 462–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- No, S.Y. Inedible Vegetable Oils and Their Derivatives for Alternative Diesel Fuels in CI Engines: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, M.S. Experimental Investigation of Diesel Engine Emissions Using Blends of Waste Vegetable Oils. J. Eng. Sci. 2023, 51, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, L.; Carvalho, P.; Bastos, D.; Pires, N. Effects on Performance, Efficiency, Emissions, Cylinder Pressure, and Injection of a Common-Rail Diesel Engine When Using a Blend of 15% Biodiesel (B15) or 15% Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil (HVO15). SAE Tech. Pap 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevez, R.; Aguado-Deblas, L.; López-Tenllado, F.J.; Bautista, F.M.; Romero, A.A.; Luna, D. Study on the Performance and Emissions of Triple Blends of Diesel/Waste Plastic Oil/Vegetable Oil in a Diesel Engine: Advancing Eco-Friendly Solutions. Energies 2024, 17, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdziennicka, A.; Szymczyk, K.; Jańczuk, B.; Longwic, R.; Sander, P. Surface, Volumetric, and Wetting Properties of Oleic, Linoleic, and Linolenic Acids with Regards to Application of Canola Oil in Diesel Engines. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žaglinskis, J.; Rimkus, A. Research on the Performance Parameters of a Compression-Ignition Engine Fueled by Blends of Diesel Fuel, Rapeseed Methyl Ester and Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousoulidou, M.; Fontaras, G.; Ntziachristos, L.; Samaras, Z. Biodiesel blend effects on common-rail diesel combustion and emissions. Fuel 2010, 89, 3442–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longwic, R.; Sander, P.; Jańczuk, B.; Zdziennicka, A.; Szymczyk, K. Modification of Canola Oil Physicochemical Properties by Hexane and Ethanol with Regards of Its Application in Diesel Engine. Energies 2021, 14, 4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longwic, R.; Sander, P.; Zdziennicka, A.; Szymczyk, K.; Jańczuk, B. Changes of Some Physicochemical Properties of Canola Oil by Adding N-Hexane and Ethanol Regarding Its Application as Diesel Fuel. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, P.; Longwic, R.; Jańczuk, B.; Zdziennicka, A.; Szymczyk, K. The Use of Canola Oil, n-Hexane, and Ethanol Mixtures in a Diesel Engine. SAE Int. J. Fuels Lubr. 2021, 14, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Qu, L. Using a Chassis Dynamometer to Determine the Influencing Factors for the Emissions of Euro VI Vehicles. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2018, 65, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatarynow, D.; Longwic, R.; Sander, P.; Zieliński, Ł.; Trojgo, M.; Lotko, W.; Lonkwic, P. Test Stand for a Motor Vehicle Powered by Different Fuels. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpach, O.A. Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicles Test Procedures (WLTP). Natl. Transp. Univ. Bull. 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczyk, K.; Zdziennicka, A.; Jańczuk, B.; Lubas, J.; Jaworski, A.; Kuszewski, H.; Woś, P.; Longwic, R.; Sander, P. N-Hexane Influence on Canola Oil Adhesion and Volumetric Properties. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2025, 140, 103990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oss, C.J. Interfacial Forces in Aqueous Media, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oss, C.J.; Costanzo, P.M. Adhesion of Anionic Surfactants to Polymer Surfaces and Low-Energy Materials. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 1992, 6, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oss, C.J.; Good, R.J. Surface tension and the solubility of polymers and biopolymers: The role of polar and apolar interfacial free energies. J. Macromol. Sci. 1989, 26, 1183–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oss, C.J.; Chaudhury, M.K.; Good, R.J. Monopolar Surfaces. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 1987, 28, 35–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowkes, F.M. Attractive Forces At Interfaces. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1964, 56, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, R.J.; Elbing, E.R.J. Generalization of Theory for Estimation of Interfacial Energies. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1970, 62, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczyk, K.; Zdziennicka, A.; Jańczuk, B. Comparison of surface tension, density, viscosity and contact angle of ethyl oleate to those of ethanol and oleci acid. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 400, 124525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jańczuk, B.; Sierra, J.A.M.; González-Martín, M.L.; Bruque, J.M.; Wójcik, W. Properties of Decylammonium Chloride and Cesium Perfluorooctanoate at Interfaces and Standard Free Energy of Their Adsorption. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1997, 192, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szaniawska, M.; Szymczyk, K.; Zdziennicka, A.; Jańczuk, B. Adsorption Properties and Composition of Binary Kolliphor Mixtures at the Water–Air Interface at Different Temperatures. Molecules 2022, 27, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taraba, A.; Szymczyk, K.; Zdziennicka, A.; Jańczuk, B. Mutual Influence of Some Flavonoids and Classical Nonionic Surfactants on Their Adsorption and Volumetric Properties at Different Temperatures. Molecules 2022, 27, 2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jańczuk, B.; Zdziennicka, A.; Wójcik, W. Relationship between wetting of teflon by cetyltrimethylammonium bromide solution and adsorption. Europ. Polym. Sci. 1997, 33, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).