Abstract

Underground hydrogen storage (UHS) is emerging as a key enabler of the green energy transition, ensuring energy system stability and supporting large-scale integration of renewable sources. Despite its technological readiness, UHS deployment in Europe faces significant barriers due to the absence of a clear legal status and a dedicated regulatory framework. Current EU energy, climate, and environmental directives do not explicitly define hydrogen as a storage medium, creating legal ambiguity. Lessons from underground gas storage (UGS) and Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) provide valuable reference points; however, direct transfer of these frameworks is insufficient due to hydrogen’s the distinct physicochemical characteristics and associated safety and monitoring challenges. Major regulatory gaps have been identified in legislation, liability, ownership, technical standards, and monitoring. To address these issues, a hybrid UHS model is proposed—combining the operational practices of UGS with the regulatory rigour of CCS—to accelerate safe and efficient implementation of UHS in Europe and support the broader transition to green energy.

1. Introduction

1.1. Context and Significance of UHS

Underground hydrogen storage (UHS) represents a cornerstone of the emerging green energy infrastructure, providing the flexibility required to integrate intermittent renewable energy sources, stabilise electricity networks, and decarbonise industrial sectors [1,2,3,4,5]. The growing attention to UHS—reflected in numerous recent reviews [6,7] and review articles in this field today [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]—has yet to be matched by regulatory progress. Both European and national legal systems remain fragmented, lacking a coherent framework for UHS operations [11,17,18,19]. The absence of precise definitions for hydrogen stored underground across different phases of its life cycle, together with unclear provisions on ownership, liability, monitoring, and post-operational responsibility, creates major uncertainties for project developers. In practice, current regulation relies on analogies to frameworks for underground gas storage and CO2 storage, which fail to reflect hydrogen’s unique physicochemical behaviour—its high diffusivity, geochemical and microbiological reactivity, and potential explosiveness [8,16,19,20,21,22].

It should be emphasised that in the case of related UHS technologies, including natural gas storage, liability issues are usually regulated by national law, such as the Geological and Mining Law, but even these rarely refer to hydrogen as a medium stored underground. The so-called CCS (Carbon Capture and Storage) Directive [23] on the geological storage of CO2 establishes precise rules on liability, including its transfer to the state after the closure of a storage facility. However, it does not refer to hydrogen [24,25].

Technical reports, policy documents, and scientific publications consistently highlight the urgent need to harmonise and clarify the legal status of underground hydrogen storage:

- The IEA Hydrogen TCP Task 42 Report (2023) states that UHS development is unfeasible without a clear legal framework. Authorities require licencing and monitoring guidelines, while operators need regulatory stability to justify long timelines and high investment costs [19].

- The HyUnder report (2013) emphasises that early-stage energy transition technologies depend on favourable regulation to minimise investment [26].

- The HyStories project (2022–2023) notes that EU-wide UHS legislation is difficult due to varying national laws on energy, mining, and environmental protection [27].

- Regulations, Codes, and Standards Review for Underground Hydrogen Storage (2024) notes that regulations on underground natural gas storage could serve as a reference point for UHS legislation. At the same time, it points to technical gaps and fundamental differences in the physical properties of hydrogen and methane, which may require separate technological and regulatory solutions [28].

- The European Commission’s Hydrogen Strategy for a Climate-Neutral Europe (COM(2020) 301 final) emphasises the need to strengthen the EU’s role in shaping international technical standards, regulations, and definitions for hydrogen [2].

- The H2eart for Europe report (2024) emphasises that the absence of a dedicated regulatory framework at the EU level is a key barrier to UHS deployment. It highlights the need for harmonised permitting procedures, technical standards tailored to hydrogen, and the legal recognition of UHS as critical energy infrastructure [29].

- The RPT-EU_Underground Hydrogen Storage Targets report (2024) warns that without clear regulatory provisions and long-term policy support, the EU may face a hydrogen storage gap that threatens its decarbonisation objectives. It calls for binding storage targets (e.g., 45 TWh by 2030) and integration of UHS into EU energy and climate law [30].

- ISO 24078:2025 highlights that the development of underground hydrogen storage (UHS) requires not only technical advancements, but also regulatory support, including standardisation of monitoring procedures, safety guidelines, and long-term storage operation frameworks [31].

Similar conclusions can be drawn from normative and industry documents:

- DNV-RP-H101 (DNV-RP-H101, 2021) recommends a dedicated UHS licencing and monitoring system, noting that operators currently rely on gas and CCS rules [32].

- The EU Hydrogen Strategy also prioritises building a supportive regulatory framework and reducing cost gaps between conventional and low-carbon hydrogen [33].

All these studies and documents indicate that the development of UHS requires the creation of clear and consistent legal regulations. These should include a definition of hydrogen in the storage process, the scope and duration of the operator’s liability, procedures for the state or another authority to take over responsibility after the closure of the storage facility, environmental monitoring requirements, and rules for compensation for damage. It is expected that these regulations will take the form of European Union directives, which will then be implemented into the legal systems of Member States, but will contain sufficiently detailed regulations or standards to ensure reasonably uniform requirements and legal conditions for the entire European Union, Best Available Techniques (BATs) reference documents, and ISO and DNV standards.

The lack of a clear legal framework for hydrogen is currently a significant barrier to the implementation and scaling up of UHS projects both in the European Union and in individual Member States (many of which are likely waiting for earlier EU regulations in this area). Strategic documents and expert reports have repeatedly emphasised that read-across regulations from the CCS and UGS areas may be a transitional solution, but in the long term it is necessary to create regulations dedicated to UHS technology [19,26,27].

Current pilot UHS projects in the European Union, such as H2CAST Etzel in Germany and HyStock in the Netherlands, are being developed under existing legal frameworks for underground gas storage (UGS) and national mining and energy laws. To date, no dedicated or harmonised EU-wide legal framework exists specifically for hydrogen storage in geological formations. In Germany, the H2CAST Etzel project operates under the national Mining Act (Bundesberggesetz) and regulations applicable to underground natural gas storage, with additional risk and safety assessments specific to hydrogen [34]. In the Netherlands, the HyStock project by Gasunie has been authorised under the existing Dutch Mining Act. The hydrogen storage caverns at Zuidwending were granted a storage permit as gas storage infrastructure, though legislative amendments are underway to better reflect hydrogen-specific considerations [35]. Overall, most pilot UHS initiatives in the EU rely on a “read-across” regulatory approach—adapting legal regimes developed for natural gas storage—while awaiting dedicated legislative instruments tailored to hydrogen [27].

1.2. Purpose and Scope of the Article

The aim of this study is to analyse the legal status of hydrogen in the context of underground storage, with particular emphasis on the need to harmonise regulations at the European level. Key issues related to the legal status of hydrogen are discussed, ranging from the need to harmonise regulations, through an analysis of the existing legal framework and its limitations, to recommendations for future legislative directions.

The scope of the research includes the identification and assessment of existing regulations concerning gases stored underground (hydrogen, natural gas, CO2) and the indication of the consequences of their application for the functioning of UHS. The article addresses the issues of responsibility for injected and recovered hydrogen, and points to the need to develop dedicated reference documents (BATs) and international standards (ISO, DNV). An integral part of the analysis is the assessment of the possibility of adapting the experience and legal solutions developed in UGS and CCS technologies, together with recommendations, for the development of a uniform regulatory framework for UHS.

2. Methods

The research methodology employed in this article is based on a comparative regulatory analysis encompassing legal acts, standardisation documents, and the scientific literature related to underground gas storage. The aim of this approach is to systematically identify which elements of the existing regulatory frameworks for Underground Gas Storage (UGS) and Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) can be adapted to future legal frameworks for underground hydrogen storage (UHS). The analysis covered European Union legislation on energy, environment, installation safety, transport, and emissions; reference and normative documents, including BATs—Best Available Techniques reference documents on minimising environmental impacts of installations; ISO—technical standards on quality, safety, and management; DNV—guidelines and standards for energy infrastructure and risk assessment; EU ETS—the EU Emissions Trading System; and IPCC Guidelines—guidance on reporting greenhouse gas emissions and removals.

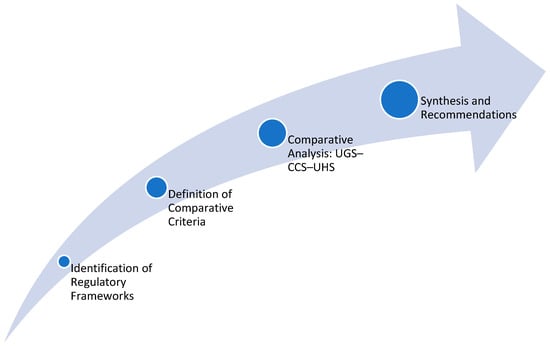

The research design included the following steps (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Methodological workflow for UHS regulatory analysis.

- Identification of regulatory frameworks—Applicable legal provisions and standardisation documents related to UGS, CCS, and UHS were identified. The scope of their applicability, regulatory objectives, and associated obligations for operators were analysed. This step addressed the following question: Which regulations determine the operation of underground gas storage installations in the EU?

- Definition of comparative criteria—To structure the comparative analysis, key regulatory areas relevant to the operation of underground gas storage installations were extracted. These include legal status and classification of the stored medium, permitting and licencing procedures, principles of ownership and responsibility for the gas, long-term liability and site closure, monitoring and reporting requirements; safety and risk assessment requirements, technical standards and reference documents (BATs, ISO, DNV), and links to climate policy and emission systems (EU ETS, IPCC). This analysis answered the following question: In which areas can the solutions applied in UGS and CCS serve as references for future UHS regulations?

- Comparative analysis (UGS–CCS–UHS)—Based on the criteria above, a comparison was conducted of three systems: UGS, as a mature operational model for gas storage; CCS, as an example of integrated legal frameworks for permanently stored substances; and UHS, as a technology lacking a dedicated regulatory system. This comparison enabled the identification of regulatory overlaps, gaps, and areas of incompatibility.

- Synthesis and recommendations—Based on the identified gaps and potential for adaptation from UGS and CCS, this study developed proposals for regulatory directions for UHS, guidelines for future technical standards, and a hybrid UHS model integrating operational experience from UGS and regulatory oversight elements from CCS.

This research approach enables a structured transition from identifying legal and regulatory gaps through comparative 78 green assessment of three existing systems to the development of coherent recommendations for the future legal framework for UHS. As a result, the applied methodology clearly determines which legislative solutions can be transferred from current systems, which require adjustment, and which need to be developed from scratch.

3. Results

The current legal status of hydrogen remains ambiguous and depends largely on the context of its use. Hydrogen can be treated as a raw material, fuel or energy carrier, and storage medium [2,36]. It is sometimes classified as a hazardous substance or a potential source of environmental emissions. The lack of regulatory consistency has numerous consequences for the planning, operation, and monitoring of underground hydrogen storage facilities. This is not an isolated phenomenon. Sometimes, a substance has a uniform definition in law—for the entire legal system of a given country—and sometimes it has different definitions in different areas/regulations. Therefore, the legal definition of a substance is important for its storage and related regulations. However, it does not have to be a single definition for the entire legal system.

3.1. Legal and Regulatory Framework of Underground Gas Storage in the European Union

Unlike natural gas, which has a clearly defined status in EU legislation, e.g., concerning common rules for the internal gas market [37], hydrogen has not been formally included in the underground storage licencing system. The proposed Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the internal markets for gas from renewable sources, natural gas, and hydrogen [38] does not explicitly include underground hydrogen storage in the existing regulatory framework. The definition of a hydrogen storage facility contained in this document does not exclude the operation of UHS, nor does it specify its rules. Instead, it provides for the possibility of temporarily exempting hydrogen infrastructure, including underground storage facilities, from certain regulatory obligations, provided that this promotes competition, security of supply, and decarbonisation, and does not interfere with the functioning of the EU internal market.

In EU strategic documents, hydrogen is recognised as a key energy carrier in the energy transition, particularly in the case of that from renewable sources (so-called green hydrogen) [36,38]. However, there is no formal definition of hydrogen as a storage medium, which makes it difficult to classify UHS installations. Hydrogen is sometimes treated as a dangerous substance, an emission, a fuel, or a market product.

Hazardous substance—Under the Seveso III Directive (2012/18/EU) [39], hydrogen is classified as a flammable and explosive substance. However, the directive is primarily in-tended for above-ground industrial installations, and its applicability to subsurface hy-drogen injection into geological formations is not explicitly defined. As a result, the extent to which Seveso III applies to underground hydrogen storage remains subject to regulatory interpretation and varies across Member States. Although the directive provides a frame-work for managing major accident hazards, there is ongoing debate over whether, and to what extent, its provisions should also govern hydrogen stored in deep geological environments.

Emission substance—Hydrogen is not a greenhouse gas, but its production (e.g., from natural gas) and potential leaks (hydrogen leakage) can indirectly affect the climate through reactions with methane and ozone. There is still ongoing debate as to whether and how these emissions should be included in reporting systems (EU ETS, IPCC).

Fuel and market product—Hydrogen can be considered a fossil fuel (grey hydrogen) or a renewable fuel (green hydrogen). This classification affects its legal status within the EU taxonomy and certification systems.

3.2. Regulatory Specificity of Hydrogen as a Storage Medium

The lack of clear regulations on the legal status of hydrogen results in ambiguities in key areas of UHS, such as licencing; responsibility for emissions; rules for trading hydrogen; and ownership of gas during storage; and thus, the issue of responsibility.

Unlike natural gas, which has a clearly defined status in EU law (e.g., Directive 2024/1788/EU [37]), hydrogen has not been formally included as a substance covered by the underground storage licencing system. The proposed Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the internal markets for gases from renewable sources, natural gas, and hydrogen (COM (2021) 804) introduces a definition of a hydrogen storage facility, which also covers underground structures, but does not specify the rules for their operation or the legal requirements for operators.

Hydrogen has not been clearly assigned to existing regulatory systems such as the EU ETS (emissions trading), Seveso III Directive, or IPCC guidelines on emission reporting. This omission makes it difficult to determine responsibility for potential emissions to the atmosphere and groundwater and limits the possibility of consistent environmental monitoring.

In the case of natural gas, continuity of ownership on the part of the operator is usually assumed. For hydrogen, there is no legal analogy, which leads to uncertainty regarding the division of responsibilities and risks. By comparison, in the geological storage of CO2, these issues have been clearly regulated in Directive 2009/31/EC (CCS Directive) [23]. It provides for the possibility of transferring responsibility for injected CO2 to state authorities once certain conditions have been met, such as long-term monitoring, no detectable leaks, and complete documentation of the operator’s activities. In the case of hydrogen, there is no equivalent to these solutions yet, even though the risks associated with its emissions and environmental impact may be equally significant.

3.3. Lack of a Comprehensive REGULATORY Framework and Consequences for UHS

There is currently no dedicated EU directive regulating underground hydrogen storage analogous to the CCS Directive. In practice, UHS projects are often classified under regulations developed for UGS or CCS, which leads to inconsistencies in interpretation and increases regulatory uncertainty [19,26,27].

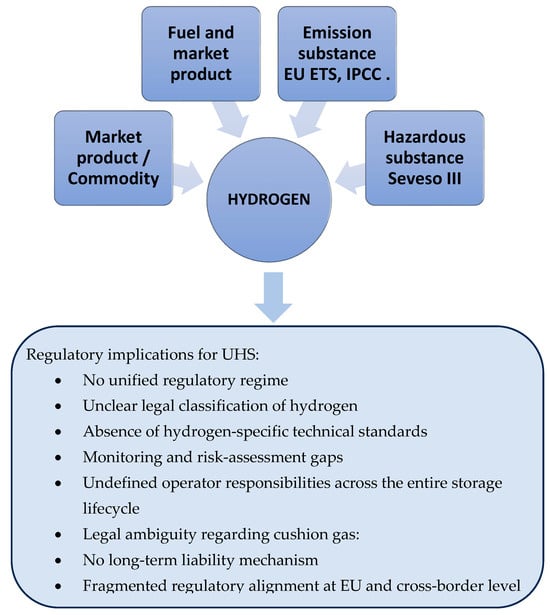

The lack of a clear legal classification of hydrogen creates significant challenges for its underground storage. This affects legal interpretation, operational practice, and regulatory consistency throughout the storage lifecycle. Key issues include the following (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Multiple legal identities of hydrogen and regulatory implications for UHS.

- Absence of dedicated standards and guidelines—Currently, there are no specific BATs (Best Available Techniques) documents or ISO or DNV standards directly applicable to UHS. As a result, operators rely on frameworks developed for natural gas storage (UGS) or Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), such as DNV-RP-H101 (2021), ISO 27914 (2017), and ISO 27916 (2019), which can lead to either overly cautious or overly simplified technical requirements.

- Regulatory gaps in monitoring and risk assessment—The lack of normative standards for leak detection, microbiological activity assessment, and geochemical monitoring makes it difficult to establish reliable oversight procedures specific to hydrogen storage.

- Unclear legal responsibilities across the storage lifecycle—There is no consistent framework defining operator obligations for environmental permits (e.g., IPPC), environmental reporting, or impact assessments. Moreover, key questions remain unanswered:

- ➢

- Who owns the hydrogen after injection into the geological formation?

- ➢

- Who is responsible for its safety during storage?

- ➢

- What rights apply to hydrogen recovery?

- ➢

- How is liability shared in cases of emissions, leaks, or after site closure?

- Lack of legal clarity on cushion gas—Hydrogen remaining in the formation post-closure has no defined legal status. It is uncertain whether responsibility transfers to the state or remains with the operator, and whether cushion gas is owned by the storage user or operator.

- Absence of long-term liability framework—Unlike CCS, which includes provisions for post-closure transfer of responsibility to public authorities, UHS lacks a clear mechanism for such handover, leaving operators and governments exposed to legal uncertainty.

- Fragmented regulatory alignment at the EU and cross-border levels—Differing national rules on energy, mining, and environmental protection hinder the development of harmonised UHS frameworks. This inconsistency creates legal and administrative barriers to cross-border UHS infrastructure. The lack of alignment with overarching EU climate policies (e.g., the European Green Deal [40], Fit for 55 [41], and Directive 2024/1788) further limits hydrogen’s strategic integration into the energy transition.

These regulatory shortcomings have been widely recognised. The IEA Hydrogen TCP Task 42 Report [19] stresses that UHS deployment is not feasible without a coherent regulatory framework. Licencing authorities require procedural clarity, while operators need predictable rules to justify long project timelines and investment risks [39]. Similarly, the HyUnder report (2013) emphasised early on that stable, technology-neutral regulation is key to reducing risk in emerging energy markets [26]. The HyStories project (2022–2023) underlines that EU-level legislation remains difficult due to national legal divergences [27].

Finally, the 2024 UHS Regulations and Standards Review acknowledges that natural gas storage rules may serve as interim references for UHS but highlights significant technical and physical differences between hydrogen and methane [28]. This is echoed by DNV-RP-H101 (2021), which calls for a dedicated licencing system, noting that hydrogen projects are still forced to rely on UGS or CCS legislation [29]. The EU Hydrogen Strategy also prioritises developing a supportive regulatory environment for hydrogen infrastructure and reducing cost disparities between conventional and low-carbon hydrogen [2,30].

Underground hydrogen storage currently operates in a landscape of regulatory uncertainty (Table 1). Existing energy, mining, and environmental legislation is primarily designed for natural gas and CO2, without offering dedicated legal pathways for hydrogen. This creates inconsistencies and legal ambiguity—with hydrogen variably classified as a fuel, a chemical substance, or an energy carrier depending on the context. The absence of a harmonised legal framework exposes investors and operators to regulatory risk, thereby posing a significant barrier to the development and scaling of UHS technologies.

Table 1.

Extended comparison of regulatory frameworks: UGS, CCS, and UHS.

4. Regulatory Comparisons, Standards, and Adaptation of Experiences

4.1. Comparative Analysis of Regulations: UGS, CCS, and UHS

The use of hydrogen as an energy medium, fuel, or substance stored underground requires its clear inclusion in legal systems. Compared with natural gas and carbon dioxide, hydrogen remains the least regulated medium for underground storage regarding classification, monitoring, liability, and permits for underground injection and withdrawal.

Natural gas—UGS (Underground Gas Storage)

The legal basis at the EU level is regulated by Directive 2024/1788 [37] on common rules for the internal market in natural gas and Directive 94/22/EC [42] on the granting and use of authorisations for the prospection, exploration, and production of hydrocarbons. Matters relating to the licencing of natural gas storage are covered by the national legislation of EU Member States.

Scope of regulation: Clear definition of natural gas as a fuel and storage medium, obligation to register and certify operators, requirements for third-party access, transparency and security, obligation to achieve minimum storage levels, environmental requirements, and supervision by national regulators (e.g., Energy Regulatory Office in Poland).

Operator responsibility: The operator bears full responsibility for safety, operation, and compliance with regulations, and there are clear reporting and supervision procedures in place by national and EU regulators.

Carbon dioxide—Carbon Capture and Storage

Legal basis at the EU level: Directive 2009/31/EC on the geological storage of CO2 [23]; standards: ISO 27914:2017 on the geological storage of CO2 [43] and DNV-RP-J203 [44]; and guidelines: IPCC Guidelines [45].

Scope of the regulation: Clear definition of CO2 as a captured and stored substance, mandatory monitoring plan approved by the supervisory authority, risk assessment (site characterisation), post-closure management, monitoring documentation requirement, and obligation to ensure reservoir integrity.

Liability: Operational phase—the operator bears full responsibility for emissions, environmental damage, control, and monitoring. Post-operational phase—possibility of transferring liability to the state after certain conditions are met.

Hydrogen—Underground Hydrogen Storage

Hydrogen is recognised in EU documents as an energy carrier. Nevertheless, there is no formal definition of hydrogen as a storage medium. Some Member States (e.g., Germany and The Netherlands) are introducing technical definitions of hydrogen in the context of infrastructure, but there is no uniform approach at the EU level with regard to its geological storage.

Scope of regulation: No comprehensive legal framework exists for UHS, nor is there a dedicated EU directive on the geological storage of hydrogen. The current approach is to temporarily apply analogies to the CCS framework [23] or UGS [37], which leads to inconsistencies in interpretation, difficulties in classifying projects, and unclear operator responsibilities.

Safety aspects and classification of hydrogen as a dangerous substance: According to the Seveso III Directive [39], hydrogen is classified as a flammable and explosive substance. This is relevant for above-ground installations but does not directly translate to underground injection. The Industrial Emissions Directive (Directive 2010/75/EU, 2010) may cover some operational aspects of UHS, but it does not refer to geological hydrogen storage technology.

Emissions, trade, and the environment: Hydrogen is not covered by the EU ETS as a greenhouse gas, but its production—especially from fossil fuels—can be classified as emissions. There are increasing calls for the inclusion of so-called hydrogen leakage in reporting mechanisms (IPCC, EU ETS) due to the possible indirect impact of hydrogen on atmospheric methane and ozone concentrations.

Table 2 shows that unlike natural gas and CO2, hydrogen does not have a dedicated and unambiguous legal status in the context of geological storage. Current solutions are based on the adaptation of CCS and UGS regulations. The lack of a legal framework for UHS limits regulatory certainty, hinders investment planning and creates a risk of inconsistency regarding liability, monitoring, and environmental protection.

Table 2.

Comparison of legal regulations for UHS, UGS, and CCS.

Although molecular hydrogen is not a classical greenhouse gas due to its lack of infrared absorption, its atmospheric release can lead to indirect climate effects. H2 reacts with hydroxyl radicals (OH), reducing the atmosphere’s capacity to oxidise methane (CH4), thereby prolonging methane’s atmospheric lifetime and enhancing its warming potential. Additionally, hydrogen can contribute to elevated levels of tropospheric ozone (O3) and stratospheric water vapour—both of which exert positive radiative forcing [46]. Recent model-based estimates place the 100-year global warming potential (GWP100) of H2 in the range of approximately 11.6 ± 2.8 kg CO2-eq per kg H2, with substantially higher values for shorter time-horizons (e.g., GWP20), depending on leakage rates and background atmospheric chemistry [46,47]. However, some recent studies suggest these values may be overestimated due to biases in OH reactivity modelling in current atmospheric chemistry models [48], As hydrogen infrastructure expands globally, robust monitoring and mitigation of hydrogen leakage will be essential to ensure that the climate benefits of a hydrogen-based energy system are not compromised.

4.2. Reference Documents and Technical Standards

Although no comprehensive and harmonised set of technical standards dedicated to underground hydrogen storage currently exists at the EU level, several standardisation efforts have recently been launched. ISO has begun incorporating hydrogen-specific terminology into its framework (e.g., ISO 24078:2025) [31], formally recognising UHS within hydrogen energy systems. In parallel, DNV has initiated joint industry projects focused on material qualification and safety aspects for underground hydrogen storage, indicating the emergence of future DNV-RP/ST documents. National initiatives, such as the Dutch National Agenda for Underground Hydrogen Storage, also announce forthcoming guidelines for UHS, particularly for salt cavern applications. These developments demonstrate rapid progress, yet they have not matured into a fully established normative system, and UHS continues to rely on regulatory tools adapted from UGS and CCS.

EU ETS and IPCC

There are currently no guidelines defining the status of hydrogen within the EU ETS and IPCC methodologies. As H2 is not a greenhouse gas, it has not been formally included in emissions trading mechanisms. However, hydrogen leakage can indirectly affect the climate, e.g., by reducing the concentration of OH in the atmosphere, affecting water vapour in the stratosphere, or extending the lifetime of methane.

Therefore, the following are necessary:

- Clear rules for reporting hydrogen losses;

- The inclusion of H2 emissions in environmental balances;

- Methods for offsetting indirect emissions;

- Classification of hydrogen as a neutral or potentially emitting medium.

BATs

BATs documents provide the basis for determining the best available techniques for environmental protection and technological risk management. The current BAT documents developed for CCS and UGS do not take into account the specific properties of hydrogen as a small-molecule gas, which easily diffuses and is susceptible to microbiological reactions. For this reason, hydrogen storage requires infrastructure resistant to hydrogen embrittlement and suitable for cyclic injection and withdrawal. Unlike CO2, hydrogen is not a medium intended for permanent storage

The necessary extensions to the BATs for UHS should include the following:

- Hydrogen detection techniques (at the ppb level);

- Selection of materials resistant to hydrogen degradation;

- Protection against diffusion and migration through microcracks;

- Microbiological monitoring;

- Procedures for cyclic gas injection and withdrawal;

- Methods to counteract surface emissions and tank integrity control.

ISO standards

Currently applicable ISO standards (ISO 27914:2017—Geological storage of carbon dioxide [43]; ISO 27916:2019—Carbon dioxide capture, transportation, and geological storage using enhanced oil recovery [49]) were developed with a view to the permanent storage of CO2 as a greenhouse gas. They do not take into account the specific nature of UHS, including the short-term and cyclical nature of storage, detection issues, and the impact of hydrogen on infrastructure and chemical and microbiological interactions in reservoir conditions.

Proposals for amendments to ISO standards for UHS should include the following:

- Definitions and classifications of UHS systems;

- Minimum design requirements for hydrogen storage facilities;

- Integrated standards for geophysical, geochemical and microbiological monitoring;

- Leak testing procedures;

- A framework for data management and reporting on compliance with standards.

DNV guidelines

Det Norske Veritas (DNV) develops technical recommendations that constitute industry standards for CCS and natural gas, among other things. The current documents are as follows:

Its current documents are DNV-RP-J203 [44]—recommended practice for geological storage of carbon dioxide—and DNV-RP-F107 [50]—risk assessment of pipeline protection, not directly referring to hydrogen storage. Their limitations include the lack of consideration of hydrogen reactivity with metals and sealing materials, models for monitoring uncontrolled hydrogen release from porous media, and specific risk assessments for hydrogen based on test injections.

Recommendations for new DNV guidelines on UHS should include the following:

- Selection of materials resistant to diffusion and hydrogen corrosion;

- Safety management models in the context of hydrogen explosivity;

- Predictive models for hydrogen migration and emission;

- Integration with digital risk management systems.

4.3. Adaptation of UGS and CCS Experience to UHS

In the absence of a dedicated regulatory framework for underground hydrogen storage, the current approach—also recommended by research projects (e.g., HyUnder, HyStories)—is regulatory read-across [51]. In the case of UHS, this involves adapting existing solutions from related UGS and CCS technologies (Table 3). This allows regulatory gaps to be filled and legal and operational continuity to be ensured during the transition period, until regulations dedicated to UHS are developed. However, due to the unique properties of hydrogen, some solutions from related technologies require significant modifications. The HyUnder project points out that the lack of clear responsibility is a key barrier to the development of UHS. Results of the HyStories project [52] emphasise the need for a consistent legal model (environmental and property responsibility). Hydrogen TCP Task 42 [19] highlights the need for a clear framework of operator and state responsibility in UHS.

Table 3.

Scope for possible adaptation of experience—comparison of UGS, CCS, and UHS.

4.4. Regulatory Scenarios for UHS

The lack of comprehensive legal regulations concerning underground hydrogen storage is a significant problem in the context of introducing and developing this technology. In addition, there are three possible ways of introducing regulations. These are the introduction of regulations by means of

- A regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council;

- An EU directive dedicated to the issue of underground hydrogen storage;

- A decision not to introduce regulations at the European Union level and to leave this issue to be regulated by individual Member States.

A regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council, as a generally applicable act (within the European Union), will lead to the harmonisation of the UHS regulatory framework. This is because it is general, binding in its entirety, and directly applicable in all Member States; in this respect, it is similar and comparable to a law in national law. In this case, the implementing regulations will be issued by the European Commission, which will shift the entire legislative burden to the European Union authorities.

Regarding the specific issue of underground hydrogen storage, the EU will still require implementation by individual Member States (EU). The implementation of such a directive will not result in the standardisation of norms concerning underground hydrogen storage, but rather in the harmonisation of the legal systems of individual Member States in this area. This is because, when implementing the provisions of the directive, individual Member States will then adapt the regulations to their legal systems. This solution will require the involvement of not only the European Union authorities but also the legislative authorities of the Member States in the entire legislative procedure. This will affect the time it takes for the regulations to come into force, as it will not only require (initially) the adoption of the directive, but also the introduction of statutory acts in individual Member States on the basis of the directive. The directives provide a period of time for their implementation into national law, but practice shows that some countries introduce regulations without undue delay, some within the implementation deadline, and some after that deadline. Therefore, the use of a directive to introduce a regime for underground hydrogen storage, although ultimately leading to harmonisation in this area of the legal systems of EU Member States, may (for a certain period of time) lead to situations where some Member States have appropriate regulations in place and others do not.

Finally, the last possible solution is to leave this aspect to be regulated by individual EU Member States. However, this solution will almost certainly not lead to the harmonisation of the UHS regulatory framework, and probably not even to the harmonisation of these frameworks (the legal regimes for underground hydrogen storage in individual countries are likely to differ significantly from one another). Furthermore, in such a case, the choice of this solution should be communicated to the Member States as soon as possible by the competent EU authority so that they can start working on their regulations.

Given that hydrogen is treated as a raw material, fuel or energy carrier, and storage medium, it is very important to define it for regulatory purposes. This is important because of the following:

- The exclusive competence of the European Union includes the customs union and the establishment of competition rules necessary for the functioning of the internal market;

- The shared competence of the EU and Member States includes the internal market, economic cohesion, the environment, energy, and research and technological development;

- Finally, the EU has exclusive competence to support, coordinate, or supplement the actions of Member States in areas such as industry (Articles 3–5 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)).

Classifying underground hydrogen storage as falling exclusively within one of these areas (e.g., only within the area of energy) will determine how this issue is regulated (jointly by the EU authorities and Member States). In this case, the most appropriate tool will be a directive; therefore, in this case there will be no harmonisation, but rather harmonisation of the regulatory framework for UHS within the EU. However, if certain aspects of underground hydrogen storage fall within other areas of competence of the European Union, these aspects should be regulated in accordance with the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (e.g., in the area of internal competition rules necessary for the functioning of the internal market, this will be an EU regulation, and for industry, it will be the legislative area of Member States, which the European Union can only support).

5. Recommendations for the UHS Regulatory Framework

The lack of clear and consistent regulations on underground hydrogen storage is one of the main barriers to the development of this technology in Europe. It is therefore necessary to develop a set of recommendations that will enable the harmonisation of regulations, ensure legal predictability for investors, and lay the foundations for the safe and effective implementation of UHS. Key areas requiring legislative, regulatory, and technical intervention are presented below.

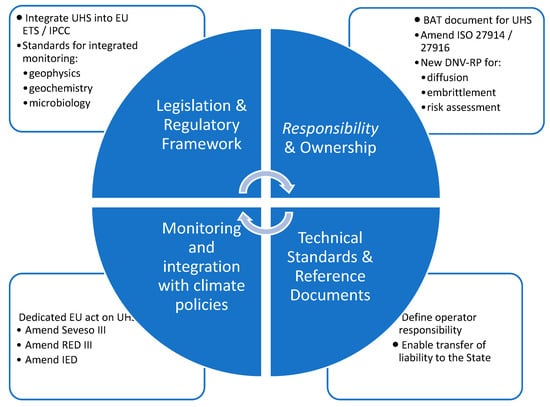

5.1. Areas of Recommendation

Recommendations concerning the legal and regulatory framework for UHS can be grouped into four main areas: legislation and regulation, liability and ownership, technical standards and monitoring systems, and integration with climate policy. Each of these areas requires separate but complementary actions, which in the long term should lead to the creation of a coherent UHS management system at the EU and national levels (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Key Areas of Recommendation for Developing the UHS Regulatory Framework and proposed actions.

Legislation and regulatory framework

The main challenge is the lack of a dedicated legal act on UHS in EU law. Currently, hydrogen is covered by scattered regulations—as a dangerous substance, fuel, or energy carrier—which leads to inconsistencies in interpretation. The introduction of separate regulations for UHS or the amendment of existing directives (Seveso III, RED III, Industrial Emissions Directive) would make it possible to clearly define the status of hydrogen and the rules for its underground storage in the context of safety, environmental protection, and energy transition. The following are proposed:

- The development of a dedicated EU legal act on UHS.

- Amending existing directives to include UHS:

- –

- Seveso III [39]—classification of hydrogen hazards;

- –

- RED III (Directive 2023/2413/EU) [36]—recognition of UHS as part of renewable energy infrastructure;

- –

- IED (Directive 2010/75/EU) [53]—H2 emissions and leaks in the integrated permit system.

Responsibility and ownership

One of the most problematic issues in UHS is the lack of a clearly defined framework for responsibility and ownership of hydrogen throughout the entire life cycle of the installation. Unlike carbon dioxide storage, where CCS Directive [23] provides for the possibility of transferring responsibility to the state after the closure of a storage site, there are no such solutions for hydrogen. In current and planned salt-cavern UHS projects (e.g., HyStock, HyCAVmobil, HPC Krummhörn), cushion gas is treated as the operator’s asset, and no CCS-type liability transfer to the state is foreseen. The introduction of similar mechanisms would reduce investment risk and ensure regulatory stability, while clearly defining the division of responsibilities between operators and the state. The following are proposed:

- Defining the framework for operator responsibility throughout the entire life cycle of a storage facility.

- Elements of the CCS liability framework (e.g., long-term monitoring, financial security backstop mechanisms) could inspire future solutions for UHS, particularly in scenarios of operator insolvency or orphaned storage sites, but a direct copy–paste of CCS post-closure transfer is neither realistic nor fully aligned with the nature of hydrogen as a commodity.

Technical standards and reference documents

The lack of dedicated technical standards for UHS is a significant gap that hinders the design and operation of storage facilities. To date, operators have been using documents developed for UGS and CCS, which do not take into account the specific properties of hydrogen. The development of a BAT document for UHS, the update of ISO 27914 [43] and ISO 27916 [49] standards, and the preparation of new DNV-RP guidelines would allow for a unified approach to risk assessment, installation safety, and environmental impact, as well as support the standardisation process on an international scale. The introduction of the following is proposed:

- A dedicated BATs document for UHS or an annex to the existing BATs.

- An amendment to ISO 27914 [43] and ISO 27916 [49] to include the specific characteristics of hydrogen.

- New DNV-RP guidelines for UHS (taking into account diffusion, hydrogen embrittlement, and risk assessment).

Monitoring and integration with climate policies

An integral part of future regulations should be the integration of UHS with environmental monitoring systems and EU climate policy. It is crucial to include UHS in the EU ETS and IPCC reporting methodology, which will allow for a reliable assessment of its role in reducing emissions. At the same time, standards for integrated monitoring systems covering geophysics, geochemistry, and microbiology should be developed to ensure safe operation and reliable assessment of the environmental impact of UHS. In this regard, the following are important:

- Integration of UHS into the EU ETS system and IPCC methodologies.

- Standards for integrated monitoring systems (geophysics, geochemistry, microbiology).

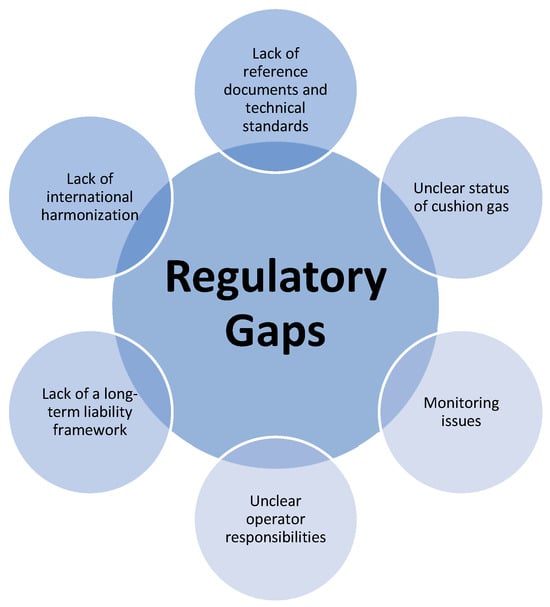

5.2. Key Gaps Requiring Regulation

Despite growing interest in underground hydrogen storage technology, there are a number of issues that require further analysis and clarification in future regulatory work. First, legal definitions and classification of stored hydrogen need to be established, as its status—whether it is to be treated as a fuel, energy carrier, chemical substance, or industrial gas—directly influences the choice of legal regimes and the jurisdiction of regulatory authorities (Figure 4). This issue is also linked to the status of buffer gas, which is necessary to maintain the functionality of the storage facility and requires clear ownership and settlement rules, especially when different technical gases are used for this purpose. Licencing and concession procedures also need to be clarified to specify the requirements for permits for the construction and operation of storage facilities and their relationship with geological and mining law.

Figure 4.

Gaps and Inconsistencies in Current UHS Regulation.

Another area is safety standards and emergency scenarios, which should define the obligations of operators regarding emergency plans, prevention, and risk minimisation, in line with the SEVESO III Directive. These measures must be complemented by a reporting and auditing system to ensure that data on injection, recovery, pressure, and safety are regularly reported to the supervisory authorities.

The integration of UHS into the broader context of European policies also requires defining its relationship to EU climate and energy policies, including the European Green Deal and the Fit for 55 package, to ensure that regulatory measures are consistent with decarbonisation objectives. Particular attention should be paid to the cross-border nature of the infrastructure, which means that rules for cooperation and coordination need to be developed for storage facilities located on the borders of EU Member States. Finally, an important element is the financial responsibility of operators, which should include financial security mechanisms such as insurance or guarantee funds, similar to the solutions known from CCS. Only comprehensive regulation of these issues will enable the creation of a coherent and secure legal framework for the development of UHS in Europe.

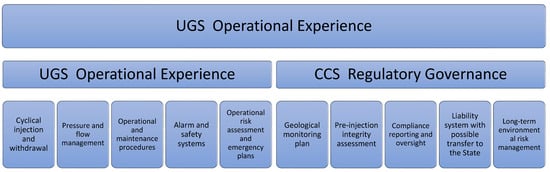

5.3. Hybrid UHS Model (UGS + CCS)

Underground hydrogen storage combines elements characteristic of two technologies: underground natural gas storage, including operational experience, operating procedures, and pressure and flow management, and geological CO2 storage, which provides models for monitoring planning, liability systems, regulatory oversight, and risk assessment.

A hybrid model (Figure 5) combining the operational flexibility of UGS with the regulatory rigour of CCS appears to be the optimal solution. However, it should be emphasised that the read-across approach to UHS has its limitations. These stem primarily from the specific nature of hydrogen, which requires dedicated risk assessment tools and the development of mechanisms for transferring responsibility to the state after the end of storage facility operation.

Figure 5.

Hybrid UHS Model.

Operational elements taken from UGS:

- Cyclical injection and withdrawal of hydrogen;

- Pressure and flow management;

- Operational and maintenance procedures;

- Alarm and security systems;

- Operational risk assessment and emergency plans.

Regulatory elements taken from CCS:

- Geological monitoring plan;

- Integrity assessment prior to injection;

- Compliance reporting and regulatory oversight;

- Liability system and the transfer of part of the responsibility to the state;

- Long-term environmental risk management.

The target hybrid UHS model ensures, on the one hand, practical feasibility and proven operational solutions characteristic of UGS and, on the other hand, high standards of safety, responsibility, and regulatory transparency developed within the framework of CCS.

6. Summary and Outlook

The analysis showed the following:

- At the European Union level, there are no clear regulations concerning hydrogen in the context of underground storage. Hydrogen is not fully covered by existing energy, climate, or environmental directives, which makes it difficult to classify it as a storage medium.

- The specific nature of hydrogen (physicochemical properties, safety, environmental risk) requires a different approach from UGS and CCS. Issues such as the ownership of hydrogen in geological structures and responsibility for long-term effects remain unregulated.

- Comparisons with UGS and CCS show that the experience gained with these technologies can provide an important knowledge base, but it is not possible to simply transfer the regulations. Dedicated solutions for UHS are needed, particularly in the areas of liability, risk transfer, monitoring, and integration with climate policies.

- Reference documents and standards (BATs, ISO, DNV, EU ETS, IPCC) remain insufficient. Updating them or developing new guidelines is essential to creating a coherent framework for the design, monitoring, and operation of UHS.

- The recommendations cover four main areas: legislation, liability and ownership, technical standards, and monitoring. In each of these areas, key gaps requiring urgent action have been identified.

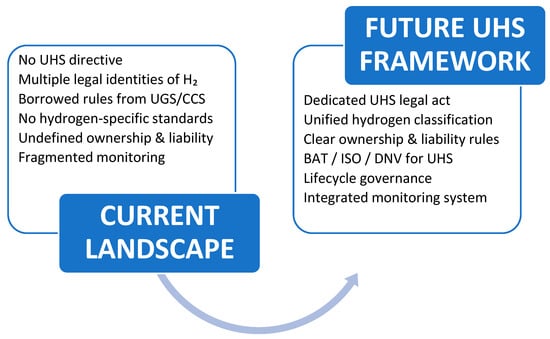

On this basis, a hybrid UHS model has been proposed, combining the operational and exploitation elements of UGS with the regulatory rigour and liability systems used in CCS. Such a model can ensure both environmental and social safety and the operational efficiency of the technology. Figure 6 illustrates the transition from the current regulatory landscape to a dedicated and integrated UHS framework, highlighting the key elements required to enable its safe and large-scale deployment.

Figure 6.

Regulatory Landscape to Desired UHS Framework.

Conclusions:

- It is necessary to start legislative work at the EU level quickly to avoid regulatory fragmentation in Member States. UHS should be included in the EU’s climate and energy security policy as a strategic technology.

- Key regulatory institutions (including the European Commission and national authorities) should set up working groups to develop guidelines dedicated to UHS. In the medium term, it is necessary to integrate UHS regulations with EU ETS mechanisms and to create a framework for liability and risk transfer similar to that for CCS.

In summary, the lack of a coherent regulatory framework is currently the main barrier to the development of UHS. The adoption of a hybrid model and the implementation of the recommended legislative and technical measures could enable the rapid and safe implementation of underground hydrogen storage as a key element of the European energy transition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, R.T.; formal analysis, R.T., P.T. and B.U.-M.; writing—original draft preparation and review and editing, R.T., P.T. and B.U.-M.; supervision, R.T.; funding acquisition, R.T. and B.U.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by AGH University of Krakow (Subsidy No. 16.16.190.779) and the Mineral and Energy Economy Research Institute of the Polish Academy of Sciences (research subvention).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BATs | Best Available Techniques |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| DNV | Det Norske Veritas |

| EU ETS | European Union Emissions Trading System |

| ISO | International Organisation for Standardisation |

| CCS | Carbon Capture and Storage |

| UGS | Underground Natural Gas Storage |

| UHS | Underground Hydrogen Storage |

References

- Bhandari, R.; Adhikari, N. A Comprehensive Review on the Role of Hydrogen in Renewable Energy Systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 82, 923–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COM/2020/301; Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions—Powering a Climate-Neutral Economy: A Hydrogen Strategy for a Climate-Neutral Europe. European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Ge, L.; Zhang, B.; Huang, W.; Li, Y.; Hou, L.; Xiao, J.; Mao, Z.; Li, X. A Review of Hydrogen Generation, Storage, and Applications in Power System. J. Energy Storage 2024, 75, 109307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku Duartey, K.; Ampomah, W.; Rahnema, H.; Mehana, M. Underground Hydrogen Storage: Transforming Subsurface Science into Sustainable Energy Solutions. Energies 2025, 18, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.; Guan, B.; Zhuang, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhu, L.; Ma, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhu, C.; Zhao, S.; Dang, H.; et al. Reshaping the Energy Landscape: Explorations and Strategic Perspectives on Hydrogen Energy Preparation, Efficient Storage, Safe Transportation and Wide Applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 97, 160–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianni, E.; Tyrologou, P.; Couto, N.; Carneiro, J.F.; Scholtzová, E.; Koukouzas, N. Underground Hydrogen Storage: The Techno-Economic Perspective. Open Res. Eur. 2024, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela Almeida, D.; Kolinjivadi, V.; Ferrando, T.; Roy, B.; Herrera, H.; Vecchione Gonçalves, M.; Van Hecken, G. The “Greening” of Empire: The European Green Deal as the EU First Agenda. Polit. Geogr. 2023, 105, 102925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernesto, J.; Fuentes, Q.; Santos, D.M.F. Technical and Economic Viability of Underground Hydrogen Storage. Hydrogen 2023, 4, 975–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hematpur, H.; Abdollahi, R.; Rostami, S.; Haghighi, M.; Blunt, M.J. Review of Underground Hydrogen Storage: Concepts and Challenges. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2023, 7, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, G.; Yan, W.; Chen, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, B.; Deng, P.; Zhang, C.; Liu, W.; Qi, H. Technical Challenges and Opportunities of Hydrogen Storage: A Comprehensive Review on Different Types of Underground Storage. J. Energy Storage 2025, 114, 115900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwakipunda, G.C.; Franck Kouassi, A.K.; Ayimadu, E.T.; Komba, N.A.; Nadege, M.N.; Mgimba, M.M.; Ngata, M.R.; Yu, L. Underground Hydrogen Storage in Geological Formations: A Review. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 17, 6704–6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miocic, J.; Heinemann, N.; Edlmann, K.; Scafidi, J.; Molaei, F.; Alcalde, J. Underground Hydrogen Storage: A Review. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2022, 528, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, M.F.; Khanal, A.; Khan, M.I.; Pandey, R. Current Status of Underground Hydrogen Storage: Perspective from Storage Loss, Infrastructure, Economic Aspects, and Hydrogen Economy Targets. J. Energy Storage 2024, 97, 112773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwo, G.O.; Tomomewo, O.S.; Oni, B.A. A Comprehensive Review of Underground Hydrogen Storage: Insight into Geological Sites (Mechanisms), Economics, Barriers, and Future Outlook. J. Energy Storage 2024, 90, 111844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivar, D.; Kumar, S.; Foroozesh, J. Underground Hydrogen Storage: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 23436–23462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, S.; Al-Shargabi, M.; Wood, D.A.; Longe, P.O.; Mehrad, M.; Rukavishnikov, V.S. Underground Hydrogen Storage: A Review of Technological Developments, Challenges, and Opportunities. Appl. Energy 2025, 381, 125172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bade, S.O.; Tomomewo, O.S. A Review of Governance Strategies, Policy Measures, and Regulatory Framework for Hydrogen Energy in the United States. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 78, 1363–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkowski, R.; Uliasz-Misiak, B.; Tarkowski, P. Storage of Hydrogen, Natural Gas, and Carbon Dioxide—Geological and Legal Conditions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 20010–20022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gessel, S.; Hajibeygi, H. Hydrogen TCP-Task 42: Underground Hydrogen Storage—Technology Monitor Report 2023; IEA Hydrogen TCP: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dopffel, N.; Jansen, S.; Gerritse, J. Microbial Side Effects of Underground Hydrogen Storage—Knowledge Gaps, Risks and Opportunities for Successful Implementation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 8594–8606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labus, K.; Tarkowski, R. Modeling Hydrogen–Rock–Brine Interactions for the Jurassic Reservoir and Cap Rocks from Polish Lowlands. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 10947–10962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkowski, R. Underground Hydrogen Storage: Characteristics and Prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 105, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive 2009/31/EC, Directive 2009/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the Geological Storage of Carbon Dioxide. Off. J. Eur. Union L140 2009, 5, 114–135. [Google Scholar]

- Fawad, M.; Mondol, N.H. Monitoring Geological Storage of CO2: A New Approach. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, A.; Blachowski, J. Remote Sensing Perspective on Monitoring and Predicting Underground Energy Sources Storage Environmental Impacts: Literature Review. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HyUnder Project HYUNDER. Available online: https://hyunder.eu/ (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Hystories Project Hystories. Available online: https://hystories.eu/project-hystories/ (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Louie, M.S.; Ehrhart, B.D. Regulations, Codes, and Standards Review for Underground Hydrogen Storage; Sandia National Lab. (SNL-NM): Albuquerque, NM, USA; Sandia National Lab. (SNL-CA): Livermore, CA, USA, 2024.

- Peterse, J.; Kühnen, L.; Lönnberg, H. The Role of Underground Hydrogen Storage in Europe; H2eart for Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Frontier Economics and Artelys. Why European Underground Hydrogen Storage Needs Should Be Fulfilled; Frontier Economics Ltd.: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ISO Standard ISO 24078:2025; Hydrogen in Energy Systems—Vocabulary. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- DNV-RP-H101; DNV-RP-N101 Risk Management in Marine and Subsea Operations. Recommended Practice 2021. Det Norske Veritas: Baerum, Norway, 2021.

- European Commission Hydrogen. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-systems-integration/hydrogen_en#eu-hydrogen-strategy (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- StoragEtzel H2CAST Green Hydrogen Storage in Etzel. Available online: https://www.storag-etzel.de/en/storage/hydrogen-h2cast (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Molenaar-Wingens, R.; In de Braekt, M.; van Angeren, J.R.; ten Hove, F. National Agenda for Underground Hydrogen Storage: Overcoming Barriers for an Essential Link in Energy Transition; Stibbe: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2023/2413; Directive (EU) 2023/2413 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 October 2023 Amending Directive (EU) 2018/2001, Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 and Directive 98/70/EC as Regards the Promotion of Energy from Renewable Sources, and Repealing Council Directive (EU) 2015/652. European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Directive 2024/1788; Directive 2024/1788 on Common Rules for the Internal Markets for Renewable Gas, Natural Gas and Hydrogen, Amending Directive (EU) 2023/1791 and Repealing Directive 2009/73/EC (Recast). European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024.

- COM/2021/804; Final, Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Internal Markets for Renewable and Natural Gases and for Hydrogen (Recast). European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- Directive 2012/18/EU, Directive 2012/18/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2012 on the Control of Major-Accident Hazards Involving Dangerous Substances, Amending and Subsequently Repealing Council Directive 96/82/EC Text with EEA Relevance. Off. J. Eur. Union 2012, 197, 77–113.

- European Council European Green Deal. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/green-deal/ (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- European Consilium Fit for 55: Shifting from Fossil Gas to Renewable and Low-Carbon Gases. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/fit-for-55-hydrogen-and-decarbonised-gas-market-package-explained/ (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Directive 94/22/EC; Directive 94/22/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 1994 on the Conditions for Granting and Using Authorizations for the Prospection, Exploration and Production of Hydrocarbons. European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 1994.

- ISO 27914:2017; Carbon Dioxide Capture, Transportation and Geological Storage—Geological Storage. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- DNV-RP-J203; Geological Storage of Carbon Dioxide. Det Norske Veritas: Baerum, Norway, 2021.

- Eggelston, S.; Buendia, L.; Miwa, K.; Ngara, T.; Tanabe, K. (Eds.) 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories—IPCC; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies: Hayama, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sand, M.; Skeie, R.B.; Sandstad, M.; Krishnan, S.; Myhre, G.; Bryant, H.; Derwent, R.; Hauglustaine, D.; Paulot, F.; Prather, M.; et al. A Multi-Model Assessment of the Global Warming Potential of Hydrogen. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Solomon, S.; Stone, K. On the Chemistry of the Global Warming Potential of Hydrogen. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1463450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.H.; Jacob, D.J.; Lin, H.; Dang, R.; Bates, K.H.; East, J.D.; Travis, K.R.; Pendergrass, D.C.; Murray, L.T.; Yang, L.H. Model Underestimates of OH Reactivity Cause Overestimate of Hydrogen’s Climate Impact. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.05127. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 27916:2019; Carbon Dioxide Capture, Transportation and Geological Storage—Carbon Dioxide Storage Using Enhanced Oil Recovery (CO2-EOR). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; p. 55.

- DNV-RP-F107; Risk Assessement of Pipeline Protection. Recommended Practice 2021. Det Norske Veritas: Baerum, Norway, 2021.

- Chesnut, M.; Yamada, T.; Adams, T.; Knight, D.; Kleinstreuer, N.; Kass, G.; Luechtefeld, T.; Hartung, T.; Maertens, A. Regulatory Acceptance of Read-Across. ALTEX 2018, 35, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hystories Hydrogen Storage Resource for Depleted Fields and Aquifers in Europe. Available online: https://hystories.eu/hydrogen-storage-resource-for-depleted-fields-and-aquifers-in-europe/ (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Directive 2010/75/EU, Directive 2010/75/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 November 2010 on Industrial Emissions (Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control) Text with EEA Relevance. Off. J. Eur. Union 2010, 334, 159–261.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).