Abstract

This study draws on the experience of selected European micro-regions in Germany, Poland, and Romania, representing different stages of a just transition, to identify applicable strategies for the Ukrainian context. The research aims to assess the spatial and economic preconditions for transformation, compare them across regions, and propose adaptation pathways. Methodologically, it combines spatial–economic analysis, comparative assessment, and critical evaluation of EU strategic approaches. The results reveal substantial disparities: European coal regions generally benefit from high population density, diversified economies dominated by the tertiary sector, strong research and education infrastructure, and cross-border advantages. In contrast, Ukrainian micro-regions are marked by demographic decline, low population density, rural settlement patterns, and complex security conditions. Based on these findings, the study recommends a localized transformation model emphasizing targeted investments, the strategic use of cross-border location, and the repurposing of existing specialized logistics and production infrastructure for new economic activities. The proposed approach contributes to the discourse on just transition by aligning regional development strategies with local structural capacities and constraints. The results obtained may be applicable in other European countries.

1. Introduction

The just transition of coal regions has become a central pillar of Europe’s pathway toward climate neutrality by 2050. Its conceptual foundation draws on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which emphasise the need for integrated, long-term territorial development aligned with environmental, social, and economic objectives [1,2]. In coal-dependent regions, the transition involves the interlinked processes of decarbonisation (SDG 7, SDG 13), economic diversification (SDG 8, SDG 9), reduction in inequalities (SDG 10), and enhancement of social inclusion and gender equality (SDG 5). This multidimensional character highlights both the systemic nature of the challenge and the need for context-specific policy solutions [3].

While research on coal phase-out has traditionally focused on energy transition and environmental efficiency [4], there is increasing recognition that structural change produces uneven social and economic impacts across regions, communities, and population groups [5]. Well-designed interventions—built on procedural, distributive, and restorative elements of just transition justice—help reduce resistance, facilitate behavioural adaptation, and strengthen stakeholder support for the transition process [6,7,8]. Despite this, empirical evidence shows that outcomes differ significantly across coal regions, even when they operate within similar national or EU policy frameworks [9,10,11,12]. This underscores the relevance of the place-based development approach, which stresses that effective transition trajectories depend on spatial conditions, institutional capacity, and endogenous resources [13,14,15,16,17].

These considerations are particularly relevant for Ukraine, a candidate country for EU membership that is at an early stage of designing a just transition policy for its coal regions. In addition to long-standing socio-economic challenges, Ukraine faces severe disruptions caused by the Russian invasion, including large-scale damage to energy infrastructure and the forced reallocation of public resources toward defence and security needs. As a result, the country increasingly relies on decentralisation, energy diversification, and regional resilience-building, making the lessons from the EU’s coal transition highly pertinent for adaptation under crisis conditions [18,19,20].

Despite a growing body of literature, several research gaps remain.

First, existing studies rarely integrate spatial–economic disparities and institutional asymmetries into a unified analytical model, even though these factors shape the adaptive potential of coal territories.

Second, most comparative analyses focus on national or regional levels, whereas microregional (LAU-level) differences—which are crucial for just transition—remain under-examined.

Third, limited attention has been given to how security-related constraints and wartime fiscal reallocation affect transition planning in non-EU coal regions.

Fourth, although just transition justice, place-based development, and regional resilience theories offer relevant insights, they have not yet been synthesised into a consistent framework capable of explaining why similar coal legacies produce divergent transformation trajectories.

Fifth, the role of public investment management as a mechanism enabling spatially balanced and socially inclusive transition remains insufficiently explored.

To address these gaps, this study develops a conceptual framework that links spatial–economic preconditions, institutional capacity, transition mechanisms, and transition outcomes for coal microregions. Integrating principles of just transition justice, place-based development, and regional resilience, the framework provides a basis for cross-country comparison and explains how structural conditions, governance quality, and security-related pressures interact to shape transition pathways.

Against this background, the study addresses the following research questions:

- (1)

- How do spatial and economic factors shape the readiness of coal microregions for a just transition?

- (2)

- What lessons from EU coal regions can be adapted to enhance the governance and financing frameworks for transition in Ukraine?

- (3)

- How can public investment management support spatially balanced and socially inclusive regional adaptation?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Framework

This study builds on three complementary strands of theory: (i) just transition justice, which emphasises distributional, procedural and recognitional dimensions of phasing out carbon-intensive industries; (ii) place-based development, which highlights the role of territorially embedded assets, constraints and institutions in shaping development trajectories; and (iii) regional and economic resilience, which focuses on how territories absorb, adapt to and transform under external shocks.

The concept of a just transition, which serves as a fundamental framework for the transformation of coal regions within the European Union, has a long historical trajectory dating back to the 1970s and encompasses a broad spectrum of scholarly interpretations. This diversity provides a robust interdisciplinary context for its evolution and comprehension. Academic discourse identifies five thematic strands that structure the conceptual understanding of the just transition: as a labor-oriented paradigm; as an integrated framework for justice; as a theory of socio-technical transition; as a scientific foundation for governance; and as a phenomenon of public perception [8,21,22].

This variety of perspectives enables the just transition to be perceived as a multidimensional process of socio-economic, governance, and cultural transformation, directed toward ensuring the rights and opportunities of key stakeholders—workers, employers, consumers, and local communities. At its conceptual core, the just transition emphasizes the recognition and inclusion of multiple dimensions of inequality and opportunity. From a human rights perspective, it seeks to reduce or eliminate existing disparities, foster social inclusion, and promote equality.

Within the framework of climate justice, particular attention is devoted to addressing the disproportionate effects of climate change: across different groups of stakeholders, among countries, regions, and local communities, and across intergenerational dimensions.

The practical significance of implementing the just transition concept stems from the uneven distribution of climate impacts and the asymmetry of mitigation efforts. Consequently, actions within the just transition process are designed to counterbalance these inequalities by maximizing benefits and minimizing adverse effects on workers and their communities.

The security context significantly alters the nature of resource distribution and social outcomes within the framework of a just transition in Ukraine. The prioritization of defense financing generates competition for limited resources, as a considerable share of both budgetary and donor funds is redirected toward the national security sector. This reorientation of financial flows results in the strengthening of structural constraints on the implementation of territorial development policies, deepens regional and social inequalities, and increases the number of economically and socially marginalized groups—particularly in communities that lose a substantial share of employment opportunities amid local market transformations.

Thus, the specific spatial and economic conditions of coal region development, combined with the complex security environment and fiscal limitations of wartime, reshape the potential trajectories of a just transition in Ukraine—ranging from accelerated adaptation to deepened inequality and delayed transformation.

In this regard, the place-based development approach [23,24] offers an essential conceptual complement to the theory of just transition. It emphasizes the importance of endogenous resources, institutional capacities, and local knowledge as drivers of regional transformation. Applying this approach to just transition policies allows for a better alignment between local needs, socio-economic structures, and policy instruments, thus enhancing the effectiveness and legitimacy of transition strategies. In the context of European coal regions—including those undergoing transition both within the EU and in neighboring countries such as Ukraine—where security challenges, institutional asymmetries, and uneven access to investments persist, a place-based approach becomes particularly relevant as it promotes spatially differentiated, context-sensitive, and institutionally grounded solutions.

Consequently, the concept of a just transition acquires a broader meaning—as an institutional mechanism for balancing between the priorities of security, economic adaptation, and social integration. It is directed not only toward ecological and energy transformation but also toward preventing population marginalization and strengthening the resilience of territorial communities as a component of national security [25,26].

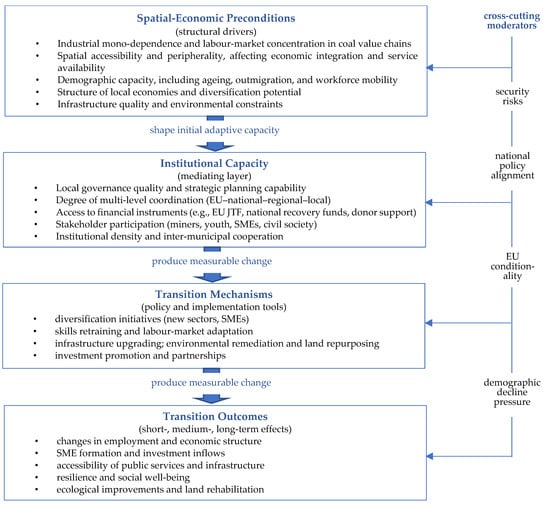

Figure 1 summarises the conceptual framework used in this article. It links three core blocks: (1) spatial–economic preconditions of coal microregions; (2) institutional capacity to design and implement just transition policies; and (3) transition outcomes in terms of diversification, social cohesion and environmental improvements.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework linking spatial–economic preconditions, institutional capacity, transition mechanisms, and transition outcomes in coal microregions.

Within this framework we formulate three hypotheses.

H1.

Coal microregions with more diversified local economies, better connectivity and stronger urban linkages are more likely to follow opportunity-oriented transition pathways, whereas peripheral, mono-functional coal territories face higher risks of socio-economic decline and out-migration even when access to support instruments formally exists.

H2.

Institutional capacity mediates the effect of spatial–economic preconditions on transition outcomes: similar coal legacies may produce different trajectories depending on the ability of local actors to mobilise resources, coordinate stakeholders and align local strategies with EU and national just transition policies.

H3.

In contexts marked by heightened security risks, such as Ukraine, the effectiveness of just transition instruments depends not only on economic structure and governance quality, but also on the reallocation of public resources to defence and critical infrastructure, which can delay or re-prioritise transition investments.

The empirical analysis operationalises this framework by (i) constructing indicators that capture spatial–economic preconditions of coal microregions in selected EU countries and in Ukraine; (ii) assessing institutional capacity through the presence and quality of strategic documents, funding access and multi-level governance arrangements; and (iii) comparing observed and planned transition outcomes across cases. In doing so, the study moves beyond descriptive comparisons and uses the conceptual framework as a lens to interpret differences in transition pathways between EU and Ukrainian coal microregions.

2.2. Research Methods

The study uses a mixed methodological approach that combines analysis of primary and secondary sources and quantitative and qualitative methods for empirical data collection and triangulation. Such a combination ensures a balanced integration of empirical data and conceptual interpretation and allows for cross-validation (triangulation) of results.

The research process was structured into several interrelated stages (Table 1), each aimed at deepening the understanding of how public investment and institutional mechanisms contribute to regional transition and sustainable development.

Table 1.

Research Framework and Analytical Stages.

The authors acknowledge their direct involvement in the implementation of the project on developing action plans for the just transition of coal microregions in Lvivska and Volynska oblasts of Ukraine. This engagement provided valuable access to empirical data, local perspectives, and practical insights that significantly enriched the analysis presented in this study.

To mitigate potential bias arising from this involvement, the authors employed a set of methodological safeguards. Data triangulation was ensured through the integration of primary and secondary sources, including official statistics, policy documents, and independent analytical reports. Multiple authors with diverse institutional affiliations participated in data interpretation and manuscript preparation, which promoted critical discussion and balanced viewpoints. The study’s conclusions were derived solely from systematically collected evidence and comparative analysis, rather than from subjective experiences or project-related evaluations.

This reflexive approach allowed the authors to combine insider understanding with academic rigor, ensuring both contextual depth and analytical objectivity in examining just transition processes in Ukraine and the EU.

2.3. Research Zones and Processes

The EU experience provides an essential reference point for Ukraine, particularly through the Just Transition Mechanism (JTM) and the Cohesion Policy framework, which operationalize multi-level governance and territorial justice principles. These instruments illustrate how financial, institutional, and participatory mechanisms can guide economic restructuring and social inclusion in coal-dependent regions.

By comparing EU and Ukrainian coal microregions, this study identifies transferable policy models and institutional practices that can inform Ukraine’s transition strategy under conditions of fiscal limitation and security risk.

Four coal regions in the EU countries were selected in order to find the answers to the abovementioned questions: Ruhr region and Saar coalmining region in Germany, Silesian voivodeship in Poland, Jiu Valley coal intensive micro-region in Romania. They are substantially different in their key characteristics and initial transition conditions and are at different stages of just transition. The selection of coal regions is determined by their ability to represent different configurations of spatial, economic, and institutional conditions in the process of just transition. Each of them corresponds to distinct stages of transition and governance models:

- -

- Ruhr region (Germany)—a completed transition in an agglomeration-type region with high population density and a predominance of private ownership of coal mines. During the transformation process, the focus was placed on the development of a scientific and innovation base, which allows for assessing the impact of agglomeration effects on economic diversification throughout the transition.

- -

- Saar coal-mining region (Germany)—a region with a transitional economy and state ownership of coal mines. This case enables the examination of the role of institutional leadership and mechanisms for attracting large investors in facilitating regional transition.

- -

- Silesian voivodeship (Poland)—a region in the active phase of transition. Its selection is driven by the need to analyze transition planning and implementation, as well as the specific patterns of resource allocation within a polycentric industrial region, where partial continuation of coal mining (due to demand for coking coal) and an extended transition period are envisaged.

- -

- Jiu Valley coal microregion (Romania)—a region at the initial stage of transition. The choice is based on the specific conditions of the microregion, including spatial peripherality, low population density, and strong dependence on a single industry.

- -

- Coal microregions of Lvivska and Volynska oblasts (Ukraine)—peripheral border territories with low population density and different histories of investment intervention, which enables the comparison of institutional capacities under wartime threats.

The regions selected for comparison make it possible to construct a contrasting matrix of observations across the main parameters: type of spatial organization (agglomerated/peripheral), ownership model of coal mines (state/private), sources of transformation financing, and stage of transition. This provides an empirical basis for comparing how different combinations of spatial conditions and institutional capacities determine transition outcomes—in accordance with the conceptual model of the influence of spatial conditions and institutional capacity on the results of transition (Table 2). This approach to the analysis is driven by the aspiration not only to detect the short-term consequences of the transition but also to identify the role of various tools applied in transition, and to adopt practical algorithms for reformatting the economies of the coal microregions of Lvivska and Volynska oblasts in Ukraine for their long-term development.

Table 2.

Comparative characteristics of coal-mining regions in the EU and Ukraine.

Here is some brief information about selected coal regions in the EU.

The Ruhr region in northwestern Germany has been the center of European coal mining and steelmaking since the mid-1800s. At the present stage, it is an industrial region with a high population density. In the context of post-war reconstruction and strengthening of the sector’s position, about 70% of the total number of people employed in the region worked in the coal and metallurgical industries [36], and as of 1980, these industries accounted for ½ of the regional GDP. Given these aspects, the Ruhr region had a rather weak foundation for economic restructuring in subsequent periods due to the dominance of large coal companies and the underdevelopment of small and medium-sized business and the education sector (until 1961, there were no higher education or technical institutions here). However, unlike other coal regions proposed for comparison, the reason for the region’s transition is the loss of competitive position of the hard coal mined here compared to cheaper imported coal, and the gradual diversification of fuel types. Therefore, the transition of the region was not caused by change in environmental priorities, but by market conditions.

The region’s transition was based on an integrated structural policy (1966–2018), which involved a gradual reduction in coal production (by 2 million tonnes annually) and the levelling of the role of the coal mining sector against the background of a developed metallurgical industry. Despite the industry’s dependence on coal, the reduction in raw material production in the region did not affect steel mills and enterprises in related sectors, as coal imports compensated for the shortfall [28]. Accordingly, a significant number of miners found employment in metallurgical enterprises and related sectors. Targeted social support, subsidies, and early retirement programmes have been introduced to support laid-off coal industry workers, with expenditure on these programmes reaching €18 billion between 1968 and 2020 [37].

With a developed steel industry as the basis for the region’s economic resilience and an agglomeration spatial organisation that ensures a high population density, the Ruhr’s just transition policy was focused on developing the science, education, leisure, and mobility sectors. This approach yielded positive results, prevented population emigration amid mine closures, and helped increase the region’s investment attractiveness for the long-term development of new industries [12].

Analyzing the transformation of the Ruhr coal region as a completed process, it is generally regarded as successful in terms of structural economic change and the formation of a new regional identity. At the current stage, its economy is represented by well-developed sectors such as services, logistics, information technologies, and education. The formation of regional identity has been largely driven by the preservation of industrial architecture and its promotion as a key element of cultural heritage and tourism development.

However, the long transformation process has not entirely eliminated the negative consequences of economic decline and the closure of coal enterprises. The region’s economic growth rate remains below the national average, unemployment levels are higher, and many municipalities demonstrate lower fiscal capacity compared to the average indicators across Germany. This situation results from the prolonged structural transition and the reduction in tax revenues to local budgets [38].

Among the key factors explaining these economic outcomes are several specific characteristics of the Ruhr’s transformation. First, during the 1950s–1980s, the focus was primarily on overcoming the economic crisis rather than on the environmental modernization of industry [39,40,41,42]. As a result, significant subsidies were directed toward enhancing the competitiveness and protecting the local coal and steel industries. Second, the predominantly private ownership structure of coal mines became an important factor slowing the economic transformation of the region, due to resistance from coal companies. Third, the transformation process was marked by a somewhat excessive subjectivization of financial support policies for the population, primarily because of the significant political influence of coal companies and trade unions. This led to the marginalization and neglect of a considerable portion of stakeholders in the decision-making process.

The Saar coal region (Germany) was part of various states during the first half of the 20th century and reunited with Germany in 1957. Compared to the Ruhr region, it is a less populated area and is the second smallest federal land in terms of population [29]. Despite being the second largest coal-producing region after the Ruhr, the volume of production and the number of people employed in the mines here are significantly lower.

Compared to the Ruhr region, where land and mines were owned by coal enterprises (which significantly slowed down the pace of transition), much greater influence of the federal land government on the transition process was Saar’s significant advantage. As coal enterprises were state-owned and federally owned, land and property became the basis for attracting large industrial enterprises (primarily in the automotive industry) to the territory during the transition period. Between 1960 and 1970, 25,000 new jobs were created in the region [29].

Although Saar’s transition was more rapid due to the involvement of large companies, in the long term it resulted in the region’s “shift” to a new form of dependence—from the coal mining sector to the automotive industry. To mitigate this impact, the regional authorities focused on developing knowledge-intensive sectors of the economy in the late 1990s. While this had positive effects on economic diversification, the impact was limited due to the incomplete interaction between enterprises and research organisations [34,35,36].

Silesian voivodeship (Poland) is currently the largest mining region in the EU, although the industry has been in decline here for 30 years. By 2030, 16 mines and four power plants are scheduled to be closed and reorganised in the region. According to the plans, this will lead to a 25% reduction in coal production, an 80% reduction in electricity production at traditional power stations, and 12,342 job cuts [32]. The coal region transition plan provides for the gradual implementation of measures until 2049. A specific feature of the region is the presence of mines where valuable coking coal is extracted, which is included on the EU’s list of critically important raw materials [43] and meets 1/3 of the EU’s demand [44]. This may indicate the need to preserve the mines.

Silesian voivodeship has a highly urbanised and polycentric settlement network, which is typical of historically industrialised regions. The Silesian agglomeration, one of the largest in Central and Eastern Europe, has emerged here, encompassing closely located cities with strong socio-economic ties.

The implementation of the region’s just transition policy is based on dividing communities into three types: municipalities undergoing the transition of the mining industry (64 communities); municipalities (about 20) that are losing their socio-economic functions as economic and social centres of the region; growth centres (about 15). Each type has different objectives and, accordingly, different support and development tools are used. In general, transition measures in the regions are focused on: (1) developing innovation and stimulating research and development activities; (2) creating new jobs in small and medium-sized businesses in sectors related to green and innovative activities and clean mobility [45]; (3) reducing the outflow of human capital (according to official estimates, the population of the voivodeship will decrease by 18.8% between 2018 and 2050 [27]); (4) overcoming regional disparities in unemployment rates and low professional activity among women in the labour market through proactive social policies and measures to adapt potential employees to changing labour market requirements (development of vocational and higher education); (5) tackling energy poverty among households in the region and improving the energy efficiency of residential buildings; (6) ensuring the efficient operation of industrial infrastructure following the closure of coal-mining enterprises; and (7) radically improving the state of the natural environment [46,47].

Jiu Valley coal microregion is located in the Hunedoara județ in Romania. Due to its mountainous location, this area was sparsely populated until the second half of the 20th century. As a result of coal mining, the Jiu Valley has developed into one of Romania’s industrial centres. The expansion of coal mining attracted new residents to the area (population increased 33-fold, from 5000 in 1868 to 165,000 in 1992 [48]).

In 1990, 17 coal-mining areas were in operation here, but since 1997 the industry has been in decline, leading to the closure of most mines. Currently, four mines and two coal-fired power plants remain operational. The decline of the coal mining industry has led to depopulation (by 1/5 over 30 years). In particular, the mass emigration of the first generation of immigrants who arrived here during the mining boom [30]. Another problem is the loss of the main source of income for local budgets and the reduction in the network of social service providers (education, culture, social services, and healthcare) [30,31].

At the present stage, the spatial and economic specificity of the microregion lies in its location within the Western region of Romania, which is one of the most dynamic in terms of economic development. This creates potential opportunities for integrating the depressed coal microregion into broader economic chains, attracting investment, transferring innovative practices, and utilising the transport, logistics, educational, and market advantages of the Western region.

Given its mountainous location and ethnographic richness, tourism, ecotourism, woodworking, furniture manufacturing, textile industry, energy, food industry, and environmental management have been identified as the microregion’s competitive advantages during the transition phase [48]. According to the Territorial Just Transition Plan, the areas of transition for the microregion coincide with most of those for Silesian voivodeship: sustainable mobility, research and innovation ecosystem, increasing the adaptability of the local economy and job creation, digitalisation, renewable energy sources, improving the energy efficiency of residential buildings, proactive social policy, training, and ecology [25]. However, given the different spatial-economic and cultural-social conditions, the instruments for achieving this must differ.

3. Results

3.1. Spatial–Economic Preconditions of Coal Microregions (Evidence for H1)

Coal microregions of Lvivska and Volynska oblasts are located in Lvivsko-Volynskyi coal basin in western Ukraine, close to the border with Poland. These are rear regions relative to the combat zone.

Although the coal basin consists of three coal-bearing areas, coal mining is only carried out in two of them, which were developed during the Soviet era. At the time of the establishment of the Ukrainian state in the 1990s, Europe was already experiencing a prolonged decline in the coal mining industry. Therefore, significant reserves of high-quality coal discovered in Lvivska oblast outside the coal microregion have not been exploited due to reduced investment in the industry and decreased demand for coal. These deposits remain undeveloped despite their likely strategic importance as a source of coking coal.

In terms of functional type, the coal microregions of western Ukraine are classified as rural areas in the border zone. Analysing general demographic and geographical parameters (Table 1), we can note:

- -

- a rather large area of coal microregions (3304.61 km2)—in terms of this indicator, they can be compared with the coverage area of the Ruhr coal microregion and the Saar region;

- -

- the peripheral location of microregions relative to oblast centres Lviv (for coal microregion of Lvivska oblast) and Lutsk (for Volynskyi coal microregion), which are also the largest cities in the regions and are characterised by agglomeration effects on surrounding territories. This impact on both coal microregions is weak;

- -

- the absence of large cities as economic growth hubs and strong centres of positive influence on the surrounding territory in terms of centre-periphery interactions. There are 237 settlements (mostly rural) in the coal microregions, with Sheptytskyi (88,200 people, the centre of the coal micro-region of Lvivska Oblast) and Novovolynsk (57,400 people, the centre of Volynskyi coal microregion) being the largest cities.

These indicators collectively demonstrate a structurally vulnerable spatial profile typical for peripheral mono-functional coal territories.

The identified spatial patterns directly correspond to the “preconditions” block of the conceptual framework, showing how peripherality, weak connectivity, and low economic density form structural constraints on transition readiness.

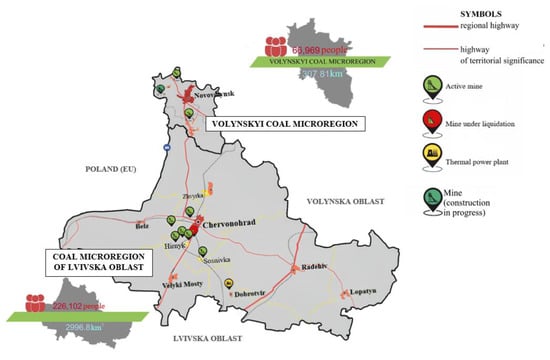

When comparing the coal microregions of western Ukraine (Figure 2), it is clear that the coal microregion of Lvivska oblast occupies 90.7% of the total area and is home to 77.1% of the population of coal-mining areas. The coal microregion of Lvivska oblast is characterised by large area and several urban centres, which have developed as centres of social and economic influence on the surrounding territories. Volynskyi coal microregion is located in a compact area around the single urban centre of Novovolynsk as social and economic hub of the territory. The population density here is significantly higher.

Figure 2.

Map of coal microregions in Lvivska and Volynska oblasts.

Regional peripherality and the absence of agglomerations and large urban centres have a significant impact on population change and density. The average population density in the microregions is low compared to coal-mining regions in the EU. However, in the overall Ukrainian context, it is higher than the national average because of the developed settlement network in the western regions. The level of population declined over twenty years (2001–2021) in both microregions is the same and amounts to over 9%, while the average for both regions fluctuates between 4–5%.

In contrast to EU coal regions such as Ruhr, Upper Silesia or Central Germany—where large urban centres anchor diversification—Ukrainian coal microregions lack strong functional urban nodes, significantly lowering their adaptive capacity.

A specific feature of the development of coal microregions in western Ukraine is that they constitute a single spatial and functional system. Both microregions are characterised by similar geological and geographical features, peculiarities of the development of industrial, manufacturing, and, importantly, transport infrastructure (shared road and rail corridors), existing border infrastructure and prospects for its further development (bordering Poland), similar aspects of demographic and socio-economic development, environmental problems, etc. However, they are divided administratively: at the regional level, the microregions are managed from two different centres, Lviv (Lvivska oblast) and Lutsk (Volynska oblast).

The economic development of this territory within separate administrative regions over the course of decades has been based on the application of various approaches. This has led to certain peculiarities in the structure of the microregions’ economies, various trends towards reducing coal mining activities in the territory, peculiarities in the formation of territorial communities in the context of the administrative-territorial reform in 2014–2020, etc. Let us examine this aspect in detail.

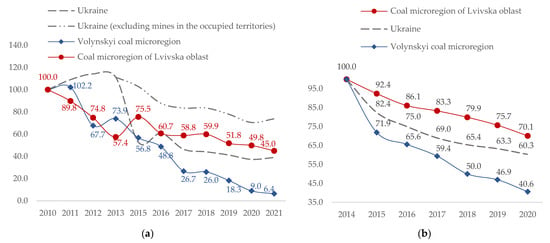

The decline of the coal mining industry in Ukraine is a long-term trend that began in the 1990s. As of 2004, five of the twelve mines in the coal microregion of Lvivska oblast and eight of ten in Volynskyi coal microregion have been liquidated. The rate of decline in coal production in western Ukraine is significantly faster than in Ukraine as a whole: in 2021, mines in Volynska oblast produced only 6.4% of the 2010 volume, and those in Lvivska oblast produced 45.0% (Figure 3). Problems in the sector confirm the trend of coal-mining enterprises losing their position as the largest employers: 29.9% of jobs were lost in six years in the microregion of Lvivska oblast and 59.4% in that of Volynska. Interestingly, a steady decline in the number of jobs has been recorded at all mines and separate divisions of coal-mining enterprises [15,35,36]—i.e., the trend is well-established.

Figure 3.

(a) Comparison of coal production dynamics in Ukrainian mines and coal microregions of Lvivska and Volynska oblasts, 2010–2021, % (2010 is the base year (100%); Ukraine (excluding mines in occupied areas)–2015 was selected as the base year for 2015–2021); (b) Comparison of the dynamics of the number of full-time employees at coal-mining enterprises in Ukraine and coal microregions of Lvivska and Volynska oblasts, 2014–2020, % (2014 is the base year (100%). Source: compiled based on [49].

Many of the reasons for the deterioration of the situation are common to both Ukraine and EU countries: outdated technology, declining demand for coal, structural unprofitability of the industry, and unequal conditions of competition compared to imports. The following features are typical only for domestic coal mining realities: loss of sales markets amid the collapse of the USSR, an inefficient system of management of state-owned coal enterprises (most mines in Lvivska and Volynska oblasts were state-owned), low level of process automation, outdated equipment, higher accident and injury rates, etc. Probably the main reason is the long-term unprofitability of state-owned coal-mining enterprises, which is associated with inefficient mechanisms for managing coal mining processes and the sale of coal products on the energy market. This is evidenced by the ratio of miners employed by state-owned coal-mining enterprises and the coal they extract to the total volume: 50% of miners, who extract only 10% of coal [50].

Despite the steady deterioration of the coal mining sector throughout the coal microregions of western Ukraine, it is evident that these trends were more pronounced in Volynskyi coal microregion. At the present stage, the dependence of the local economy on this sector is significantly lower compared to the coal microregion of Lvivska oblast: only 5% of those employed compared to 15% in the coal microregion of Lvivska oblast; 0.2% of generated added value compared to 0.8% in Lvivska oblast [51]; 2.3% of personal income tax revenues paid by coal-mining enterprises in the own revenues of budgets of the territorial communities of the microregion compared to 10.7% in the communities of the coal microregion of Lvivska oblast [35,36].

The evidence confirms H1: spatial peripherality, weak agglomeration linkages, limited economic diversification and demographic vulnerability significantly reduce the adaptive capacity of coal microregions. More compact and economically concentrated territories (e.g., Volyn microregion) demonstrate higher transition readiness compared to more dispersed, rural and polycentric territories (e.g., the Lviv microregion).

3.2. Institutional Capacity and Divergent Transition Trajectories (Evidence for H2)

Due to the rapid closure of coal mines at a national level, Ukraine decided to introduce a special investment regime in Novovolynsk for a period of 30 years [52,53], with the aim of stimulating the creation of new jobs by introducing a number of tax incentives. This regime was in place for twenty years (2001–2022) and resulted in the attraction of powerful industrial enterprises to the city.

The effectiveness of introducing a special regime for investment activity is evidenced by comparative indicators of industrial activity at the present stage: there are an average of 7.5 industrial enterprises per 10,000 inhabitants in Volynskyi coal microregion, while only 4.5 in the coal microregion of Lvivska oblast. In terms of the density of industrial enterprises per unit of area, Volynskyi microregion also has an advantage—360 enterprises per 1000 km2 against 210 in that of Lvivska oblast, indicating more intensive development of production infrastructure within the special investment regime zone.

However, the spatial features of microregions should not be overlooked: Volynskyi coal microregion is characterised by its compact territory, which is almost ten times smaller than microregion of Lvivska oblast, and its concentration around a single urban centre—Novovolynsk. In contrast, the coal microregion of Lvivska oblast covers a much larger predominantly rural area with several urban centres, forming a more dispersed model of spatial organisation with a characteristic polycentric structure. Therefore, it is logical that the density of industrial enterprises is lower here.

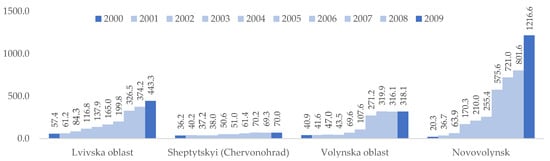

To ensure the reliability of the analysis of the effectiveness of the special investment regime, it is worth focusing on comparing the dynamics of economic development in the key coal centres of the microregions–Sheptytskyi (formerly Chervonohrad) and Novovolynsk. The special regime in Novovolynsk resulted in the attraction of significant amounts of foreign direct investment (Figure 4), whereas it is not the case in Sheptytskyi. Between 2001 and 2009, 15 investment projects with a total estimated cost of $36.7 million were implemented in the special zone, 14 of which were the result of foreign investment [54].

Figure 4.

Dynamics of foreign direct investment per capita in Sheptytskyi, Novovolynsk, and Lvivska and Volynska oblasts in 2001–2009, $. Source: compiled based on [54,55,56].

Over the eight years of the special regime, the share of industrial products manufactured within the special zone in the total industrial output of the region increased from 0.5% to 12.8%. In the economic structure of Novovolynsk, the coal mining sector, which accounted for 40.7% of industrial output in the early 2000s, has been overtaken by the processing industry (47.5% in 2009). The special regime resulted in the creation of 2218 new jobs [54]. At the present stage (2020/2015), the positive effect of the city’s development continues—Novovolynsk is characterised by the highest economic growth rates compared to other cities of Volynska oblast [15]. The city is one of the main industrial centres of Volynska oblast.

Conversely, the development of Sheptytskyi is linked to the coal mining industry. Although in decline, it played and continues to play a key role in the city’s economy (Figure 5). The preservation of most mines (seven mines are currently in operation) has played a restraining role in the context of the transition of the local economy, as they not only are centres of employment for the city’s residents but also provide their employees with better pay and social security conditions.

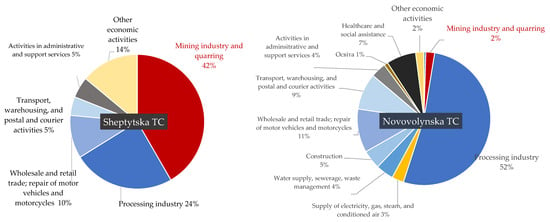

Figure 5.

Economic structure of Sheptytska and Novovolynska territorial communities by the amount of taxes paid to budgets of all levels by business entities (excluding budgetary institutions), 2023. Source: compiled based on [57].

Therefore, we can conclude that there are various tasks for the effective transition of coal microregions in western Ukraine:

- -

- Novovolynsk, as the centre of Volynskyi coal microregion, has already undergone the main stage of economic transition: it has diversified economy, a significant number of jobs in various sectors, and one of the highest rates of economic development in the region. However, just transition in the microregion must take place outside the city—in two rural communities where mines and other separate divisions of the coal-mining enterprise are the main economic development entities: budget-forming and largest employers;

- -

- The coal microregion of Lvivska oblast is only just entering a phase of significant transition, and Sheptytskyi, as the centre of coal mining and the largest city, requires perhaps the most attention in this context. On the other hand, the microregion covers a large area and, accordingly, local communities vary in their dependence on the coal mining sector. This allows for a territorially oriented approach to the transition of each community’s economy, taking into account the advantages and strengths of each community (e.g., the agricultural orientation of Radehivska and Lopatynska communities; the advantages of narrow specialisation (energy) of Dobrotvirska community, the developed logistics infrastructure of Sheptytska and Sokalska communities).

These differences illustrate the mediating role of institutional capacity in the conceptual framework: governance tools, incentives and strategic planning transform structural disadvantages into diversification opportunities.

Thus, the institutional mechanism causally explains why similar coal legacies lead to different transition trajectories: Novovolynsk’s targeted incentives generated new industrial growth, while Sheptytskyi’s economy remained path-dependent on coal.

Compared with EU regions, where multi-level programming and strong regional authorities have coordinated transition (e.g., JTF programmes in Poland, Germany, Czechia), Ukraine’s institutional landscape is uneven and produces territorially divergent outcomes.

These findings support H2: regions with similar coal legacies follow different transition trajectories due to institutional asymmetries. Stronger institutional capacity—expressed through strategic planning tools, targeted incentives (such as the special investment regime) and municipal economic leadership—transforms structural disadvantages into diversification opportunities. Where such mechanisms are absent, mono-functionality and coal dependency persist, delaying transition readiness.

3.3. Security-Driven Fiscal Reallocation and Transition Mechanisms (Evidence for H3)

In 2023–2024, plans were developed for the just transition of coal microregions in Lvivska and Volynska oblasts. They are based on adapting EU approaches to Ukrainian conditions. The key transition areas include [35,36]:

- -

- economic diversification through the effective use of post-industrial territories, the creation of economic centres with tax preferences and favourable conditions for business development, and support for the development of small businesses;

- -

- achieving environmental sustainability and a green transition of microregions’ economies through the development of renewable energy sources, restoration of environmental components, modernisation of municipal infrastructure, and effective waste management;

- -

- building up the logistical capacity of microregions based on their border location and diversified well-developed transport infrastructure;

- -

- development of the educational and vocational training systems in line with labour market demand and professional reorientation of laid-off workers from coal-mining enterprises;

- -

- improving the quality of social services, taking into account the needs of all segments and groups of the population.

However, several comments should be made considering the cases of economic transition in Ukrainian coal regions.

In the context of significant structural transformations of Ukraine’s public finance and investment policies under martial law. The full-scale war has reoriented national fiscal priorities toward defense and security, resulting in large-scale resource redistribution. This redistribution follows a hierarchical priority model, where expenditures for national security, critical infrastructure restoration, and basic social protection occupy the top level. However, the mechanisms of public investment management remain institutionally preserved through medium-term planning instruments—such as the Public Investment Management reform and the State Regional Development Fund—that ensure the continuity of capital expenditures aimed at regional recovery and development. Consequently, the process represents not a suspension but a functional restructuring of public investment flows, emphasizing resilience, energy security, and reconstruction projects that indirectly support coal regions and other transition territories.

This reflects the “security shock” mechanism incorporated in the conceptual framework, altering the transition mechanisms block by changing the timing, scale and financing logic of planned interventions.

Although such reallocation temporarily limits the scale of investments in economic diversification and decarbonization of coal-dependent territories, it does not marginalize their development goals. On the contrary, these goals are now being reframed within the concept of a “just recovery”, which integrates the principles of just transition into the national recovery and resilience agenda. This approach ensures that interventions in reconstruction—such as modernization of energy infrastructure, labor reskilling, support for SMEs, and development of renewable energy clusters—serve both immediate recovery needs and long-term sustainability objectives. In this way, Ukraine’s coal regions retain their strategic role in the national transformation process, evolving from zones of industrial decline into platforms for innovation, green growth, and social resilience once macroeconomic and security conditions stabilize.

This wartime fiscal restructuring is qualitatively different from EU experiences, where transition is financed primarily through cohesion funds without defence-driven resource competition.

The evidence confirms H3: in Ukraine, just transition is directly shaped by security-related fiscal trade-offs. Defence and critical infrastructure priorities reallocate public spending away from long-term diversification projects, yet the institutional architecture of public investment management remains intact. This leads to a functional restructuring—not suspension—of transition mechanisms, embedding just transition objectives within the broader framework of “just recovery”.

Overall, the empirical results empirically validate all three hypotheses and demonstrate how spatial–economic structures, institutional capacity and wartime fiscal constraints jointly shape the transition trajectories of coal microregions.

4. Discussion

We have provided a general overview of Ukraine’s coal microregions, as well as those of some EU countries. They were examined in such a way as to ensure analysis and identify the effectiveness of the European just transition policy at different stages: in Germany—after completion, in Poland—in the active phase, and in Romania—at its initial stage. Having outlined the general development features of the coal regions in the EU, we can note different approaches to transition resulting from different initial conditions.

To summarise, the competitive advantages of the Ruhr and Silesia, which form the basis for their just transition, include the presence of developed agglomerations and high population density, which creates the conditions for the development of the tertiary sector, in particular science, higher education, and innovation, and also ensures the investment attractiveness of these territories for businesses.

The Saar region of Germany, being both peripheral and rural, had a distinct advantage in a form of a combination of specific production and transport infrastructure and the benefits of its cross-border location. Scientific research shows that economic transition is more effective in the short term when new projects are linked to industries that are already developed in the region [29,58]. The success of Saar’s economic transition lies in the effectiveness of its regional policy, which involved economic reorientation based on the principle of “commonality” of the initial conditions for establishing production with the involvement of enterprises, namely: specific infrastructure, a workforce with appropriate skills, etc. [58]. Based on its developed coal mining and steel industries, the region has managed to attract powerful automotive manufacturing companies.

In terms of spatial and economic features, Ukraine’s coal microregions show significant similarities to the Jiu Valley microregion in Romania. They are united by their peripheral location relative to major economic centres, low population density, predominantly rural territory, and significantly lower GRP volumes. The combination of these factors severely limits the possibilities for economic diversification and complicates the attraction of investment to microregions. To offset their impact, the just transition of the Jiu Valley (a mountainous area) is based on economic sectors that are traditional for the microregion (but unique in the national context): tourism, animal husbandry, wood processing, and RES [48]. It is precisely through the application of a “localised” approach in the context of the just transition policy for this microregion that an attempt has been made to achieve positive results in more complex conditions. However, given the initial stage of implementation, the consequences of its application cannot be predicted.

4.1. Theoretical Reflections and Critical Reassessment of Existing Frameworks

Findings from Section 3. also provide an opportunity to critically evaluate how established theoretical approaches explain transition processes in coal-dependent regions, especially when applied to the Ukrainian context.

Just transition justice theory (Schuitema & Banerjee, 2022 [8]) highlights the importance of procedural, distributive and restorative justice in managing structural change. However, this framework implicitly assumes stable institutional environments in which fairness mechanisms can be implemented through predictable compensation schemes, broad stakeholder participation and balanced redistribution. Evidence from Section 3.3. shows that in Ukraine, transition processes unfold under persistent security risks and fiscal pressures that require prioritising defence, energy security and critical infrastructure. Under such conditions, distributive and restorative justice become asymmetric and delayed, as long-term transition goals are outweighed by urgent security-related needs. Furthermore, the theory pays insufficient attention to spatial disparities: as demonstrated in Section 3.1., the deep peripherality of Ukrainian coal microregions, weak labour mobility and fragmented settlement patterns limit the practical feasibility of just transition measures even when they are formally well-designed. The Ukrainian case therefore reveals an important gap in just transition justice theory, namely its limited ability to account for contexts where security pressures and structural territorial disadvantages fundamentally constrain the operationalisation of fairness principles.

Regional and economic resilience theories (Hassink, 2010 [15]) conceptualise transition readiness through the capacity of regions to resist shocks, recover and reorient their development trajectory. While this analytical lens is useful, our findings demonstrate two critical limitations. First, resilience theory tends to understate the role of institutional asymmetry. As shown in Section 3.2., the Lviv and Volyn microregions have similar coal legacies but follow markedly different transition trajectories due to governance quality, local leadership and the presence of targeted incentives such as the special economic regime. This indicates that institutional capacity can override structural economic features, becoming the primary determinant of transition outcomes. Second, resilience frameworks generally treat shocks as temporary and cyclical. In Ukraine, however, security risks represent long-term, systemic disruptions that continuously reshape labour markets, investment flows and public finance. Existing resilience theory provides limited tools for assessing transition trajectories under conditions of permanent uncertainty and non-cyclical shocks.

These observations suggest that both just transition justice theory and resilience-based frameworks require adaptation when applied to territories facing security constraints, institutional fragmentation and pronounced spatial disparities. The Ukrainian case thus highlights the need for theoretical models that incorporate long-term instability, uneven institutional capacity and place-based vulnerabilities into the analysis of transition pathways.

4.2. Attracting Investment in Conditions of Security Threats and Unfavourable Spatial and Economic Conditions

The advantages of the microregions of Lvivska nad Volynska oblasts include their border locations near Poland, logistical potential, availability of cheap labour (compared to EU countries) and a large number of potential investment sites. However, the situation for Ukraine’s microregions is complicated by the unpredictable security situation of the Russian-Ukrainian war. Although the coal microregions of Lvivska and Volynska oblasts are geographically among the most remote from the zone of active hostilities, the consequences of the war for their development are evident and constitute a decline in the investment attractiveness of these territories due to security risks. This makes attracting investors, particularly foreign ones, significantly more difficult.

In such conditions, there is a need to partially offset security threats by offering the most favourable conditions for doing business in a given territory. For this purpose, industrial parks have been registered in both microregions: Chervonohrad (62 ha, Greenfield status) and Novovolynsk (21.99 ha, Greenfield status). As both projects are in the launch phase, it is too early to talk about their effectiveness. However, given the positive experience of Novovolynsk in Ukraine [50] and the Wałbrzych Special Economic Zone in Poland [53], the use of such a mechanism is justified, particularly in view of the possibility of managing the process of attracting investors from specific sectors of the economy.

At the same time, the experience of developing industrial parks in Ukraine shows that local economic actors are largely unable to ensure the effective functioning of investment parks: there are even problems with parks located in communities on the outskirts of large developed cities, where there is significant demand for investment sites. On the other hand, since 2024, the state has increased its involvement in the development of such investment zones by offering to co-finance their construction: up to 50% of the estimated cost of construction works for engineering and transport infrastructure facilities or compensation for connection to networks, which is a costly procedure [59].

The Novovolynsk and Chervonohrad industrial parks are characterised by their specific location in the border regions and are based on the developed logistics and production infrastructure, which gives them certain advantages for a clearly defined group of investors. Therefore, one could argue about their potential as centres of industrial development and innovation in the near future. Meanwhile, the real effectiveness of these transition tools will largely depend on the ability of local authorities to ensure quality management, create a favourable business environment, and establish communication with potential investors.

On the other hand, the use of industrial parks as a tool for attracting investors does not contribute to solving all the problems of microregion development. Both parks are located in or near major cities. Meanwhile, the coal microregions of western Ukraine are characterised by the presence of significant rural areas with a developed agricultural sector. Therefore, as in the case of the Jiu Valley microregion, the development of renewable energy and the cultivation of so-called energy crops has been intensified as one of the areas for development in these territories.

At the same time, an analysis of EU support for renewable energy development [11] indicates insufficient effectiveness. EU funds generally do not subsidise large RES projects due to the high financial capacity of the companies implementing them. Accordingly, financial support is provided for the implementation of small projects in the process of just transition of coal regions, which, accordingly, have lower effectiveness and lower impact from implementation, and are accompanied by higher implementation risks. In other regions, this approach has led to a decline in the attractiveness of the small RES project support instrument in the context of managing a just transition in the regions. For instance, no RES installation projects were financed in the Jiu Valley, whereas the largest share of funding for RES projects was spent in the Silesian voivodeship—about 3% [11].

Across all these observations, Ukraine represents a case where spatial disadvantages are compounded by security-related uncertainty. In terms of regional resilience theory, this produces a “double exposure” effect–structural peripherality and conflict-induced investment risk—which sharply reduces transition readiness compared to EU coal regions with stable institutional and security environments.

4.3. Improving the Quality of Human Capital vs. Preserving Human Resources—Which Approach Underpins a Just Transition?

To transform rural areas with low population density and depopulation (coal microregions in Lvivska and Volynska oblasts have lost 9% of their population over twenty years; this rate is twice as high as the average for both regions), the main task is to preserve existing human resources. Achieving this goal requires the implementation of a set of measures:

- -

- adapting social policy to the needs of residents in the transition zone—the peripheral location of microregion communities significantly impacts the quality and accessibility of social services. During the Soviet period of development of Ukrainian territories, which coincided with the rise in coal mining, both Novovolynsk and Sheptytskyi were developing as mining cities with a fairly well-developed system of social services. The decentralisation reforms implemented between 2014 and 2020 have brought about significant changes in the system of social service provision to residents throughout Ukraine, ensuring the transfer of powers for their provision to the level of communities and regions. Therefore, conditions have been created in which it is possible to adapt social policy to the specific needs of residents (miners, women, young people, etc.) in these areas;

- -

- stimulating social and professional activity among regions—utilising the unique labour potential of microregions in the process of just transition requires not only promoting the existing qualifications of the working-age population but also developing future resources and preserving their unique skills, experience, and established traditions (in particular, preserving the potential of generations of energy workers who were employed at the Dobrotvirska Thermal Power Plant); as well as ensuring synergy in the interaction between the vocational education system in the region and local employers;

- -

- improving logistical accessibility within communities and of important centres—the peripheral location of microregions makes it difficult for their residents to access the wider system of services developing with large urban centres, in particular higher education for young people. Given the low population density in coal mining microregions and the large number of small settlements, ensuring easy and comfortable access for the population both between settlements within the microregion and to important regional centres is one of the conditions for retaining people in these areas.

When analysing examples of coal region transition, educational component is an important condition for the effectiveness of this process. The development of the educational system in coal-mining microregions is important for two reasons: firstly, it is a tool for adapting the population to new labour market conditions; secondly, it is a factor in mitigating the rate of population outflow in conditions of a lack of educational opportunities in the relevant territory, and conversely, a factor in attracting young people to areas with a developed education system [60,61]. In regions with agglomeration settlement systems and high population density (Ruhr, Silesia), priority is given to the development of higher education and ensuring a successful combination of educational, research, and innovation factors to improve the quality of human capital and the opportunities for its more effective use. In rural coal-mining regions, it is worth focusing on the development of vocational education: firstly, transforming this system in line with the conditions and specifics of the labour market and taking into account the needs of investors; secondly, focusing on attracting scientific components. Obviously, it is the combination of science and higher education that seems natural. However, it is the approach of combining scientific and vocational education that is being implemented in Ukraine’s coal mining microregions, which, in our opinion, is an important indication of the application of a territorial approach to just transition policy.

These findings also align with just transition justice theory, which stresses that fairness in outcomes is linked to fairness in access. In peripheral Ukrainian microregions, the inability to guarantee equal access to education, mobility and social services creates structural disadvantages that must be compensated by targeted, place-based human capital policies.

4.4. Issues Regarding the Effectiveness of the Approach to the Just Transition of a Single Spatial-Functional Zone with Different Administrative and Management Systems

Lvivsko-Volynskyi coal basin in Ukraine is managed by dividing it administratively into two coal microregions, each of which is integrated into the regional management system of Lvivska and Volynska oblasts. This approach carries risks: both in terms of synchronisation/consistency of management mechanisms, competition for resources and opportunities, fragmentation in spatial and strategic planning, and the risk of failing to take into account common advantages (which is extremely important).

Similar development conditions are typical of the Ruhr region in Germany, which is also administratively located within several federal lands (NUTS 2 level). The success of the region’s economic transition policy is the result of the emergence of management structures that extend beyond the administrative boundaries of individual lands [62].

Over a period of more than 50 years, the policy for the development of the coal region has been transformed in line with changing conditions and approaches [13,62,63]. Since the change in the direction of development of the coal region was based on economic (rather than environmental) reasons, national and regional authorities provided financial support to coal-mining enterprises by subsidising them during the early stages of the industry’s decline. A RAG fund (Ruhrkohle Aktiengesellschaft) was established as a separate management structure to provide organisational and financial support to economic entities in the coal mining sector. The existence of this structure facilitated a unified approach to the transition of the sector in different administrative units of the Ruhr coal region.

However, a common approach to strategic planning for the development of the entire territory as a single functional zone was not applied in the early stages, which in modern conditions is recognised as a weakness of the process [64,65].

According to the plans for the just transition of Ukraine’s coal micro-regions, the parties involved in their implementation include regional authorities, local governments, the Association of Coal Communities of Ukraine (created in the context of just transition [66]), etc. It appears that the development of a unified approach to the implementation of a just transition policy in both microregions of Lvivsko-Volynskyi coal basin has not yet been finalised. Analysing both transition plans, we can clearly see a single vector and common goals for development. However, it is important to maintain constant interaction in resolving practical issues and, importantly, to identify and constantly coordinate the use of the joint competitive advantages of the microregions. This requires not only joint action by local authorities within the Association of Coal Communities of Ukraine, but also at the regional level—by structural units of Lvivska and Volynska oblast state administrations.

This reflects a broader insight from place-based development theory: functional territories require functional governance. Without cross-regional coordination, transition efforts risk fragmentation, duplication of interventions and inefficient allocation of scarce resources. Strengthening inter-oblast cooperation thus becomes a structural precondition for achieving coherent and balanced transition outcomes in the Lviv–Volyn coal basin.

5. Conclusions

This study provides the first spatial–economic comparative assessment of coal microregions in the European Union and Ukraine, integrating territorial, institutional and security-related dimensions into a single analytical framework. By operationalising a conceptual model linking spatial–economic preconditions, institutional capacity and transition outcomes, the paper generates new empirical and theoretical insights into how coal-dependent regions adapt to structural change.

The results confirm H1, demonstrating that spatial peripherality, weak agglomeration linkages, limited diversification and demographic vulnerability significantly reduce transition readiness. More compact and economically concentrated microregions (e.g., Volyn) display stronger adaptive potential compared to larger, more dispersed and polycentric territories (e.g., Lviv), underscoring the importance of spatial–economic asymmetries in shaping transition trajectories.

Evidence also supports H2: institutional capacity mediates the effects of structural legacies. The comparison between Novovolynsk and Sheptytskyi illustrates how targeted incentives, governance quality and municipal leadership can transform structural disadvantages into diversification opportunities. Conversely, where institutional capacity is weak, mono-functionality and coal dependency persist even under similar transition policy frameworks.

Finally, H3 is confirmed through the analysis of Ukraine’s wartime fiscal environment. Security-driven resource reallocation alters transition mechanisms by prioritising defence, energy security and critical infrastructure. However, rather than marginalising coal regions, this process embeds transition goals into the broader framework of “just recovery”, ensuring continuity of long-term objectives through a restructured system of public investment management.

- -

- Theoretical contributions.

The study advances just transition scholarship by critically examining how existing frameworks perform under conditions of long-term instability and institutional asymmetry. It demonstrates that classical just transition justice theory insufficiently accounts for contexts where security risks limit the feasibility of procedural and distributive fairness. It also extends regional and economic resilience theory by showing that continuous, non-cyclical shocks—such as those caused by war—reshape transition trajectories more profoundly than temporary disturbances, and that institutional capacity may outweigh structural economic factors in determining adaptability. The research further contributes to place-based development theory by emphasising how spatial–economic heterogeneity conditions transition readiness in ways not fully reflected in EU-oriented models.

- -

- Practical contributions.

The proposed comparative model offers a replicable tool for assessing transition readiness at the microregional level, enabling policymakers to differentiate interventions based on spatial–economic vulnerabilities, governance capacity and security constraints. The findings highlight the need for territorially sensitive investment strategies, strengthened institutional coordination, and integration of transition planning with public investment management and national recovery frameworks.

- -

- Policy implications.

For Ukraine, the results suggest that just transition policies must be embedded within broader recovery and resilience strategies, prioritising: (i) targeted investment incentives in peripheral territories, (ii) capacity building for local governments, (iii) coordinated governance across administratively divided coal basins, and (iv) protection of human capital through improved access to education, transport and social services. For the EU, the findings illustrate how transition instruments may require adaptation when applied in non-EU contexts facing security-related disruptions.

- -

- Limitations and future research.

This study relies primarily on spatial–economic and institutional indicators, which, while analytically robust, do not fully capture behavioural and social dimensions of transition. Data comparability across countries may also be constrained by differences in statistical systems and temporal coverage. Future research should incorporate longitudinal datasets, micro-level surveys, and simulation models to assess how changes in governance, investment flows and security conditions shape dynamic transition pathways over time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.S. and L.B.; methodology, K.P.; software, I.C.; validation, O.I., I.S. and L.B.; formal analysis, K.P.; investigation, L.B.; resources, I.C.; data curation, I.C.; writing—original draft preparation, I.S. and O.I.; writing—review and editing, O.I.; visualization, J.C.; supervision, I.S.; project administration, O.I.; funding acquisition, J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Markard, J.; van Lent, H.; Wells, P.; Yap, X.-S. Neglected developments undermining sustainability transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2021, 41, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.; Malekpour, S. Unlocking and accelerating transformations to the SDGs: A review of existing knowledge. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 1939–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennich, T.; Persson, A.; Beaussart, R.; Allen, C.; Malekpour, S. Recurring patterns of SDG interlinkages and how they can advance the 2030 Agenda. One Earth 2023, 6, 1465–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cala, M.; Szewczyk-Swiatek, A.; Ostrega, A. Challenges of Coal Mining Regions and Municipalities in the Face of Energy Transition. Energies 2021, 14, 6674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higher Education Institutions, Community Engagement and Just Transition; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024.

- Otto, I.M.; Donges, J.F.; Cremades, R. Social tipping dynamics for stabilizing Earth’s climate by 2050. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 2354–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Brulle, R.J. Climate Change and Society: Sociological Perspectives; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, A.; Schuitema, G. How Just Are Just Transition Plans? Perceptions of Decarbonisation and Low-Carbon Energy Transitions among Peat Workers in Ireland. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 88, 102616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves Dias, P.; Kanellopoulos, K.; Medarac, H. EU Coal Regions: Opportunities and Challenges Ahead; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Smilevska, N. Financing Possibilities for Just Transition in the Western Balkans; CEE Bankwatch Network: Prague, Czech Republic, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- EU Support to Coal Regions. Limited Focus on Socio-Economic and Energy Transition; Special report; European Court of Auditors; Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, J.; Roser, F.; Maxwell, V. Coal Phase-Out and Just Transitions. Lessons Learned from Europe; New Climate Institute: Cologne, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kamińska, K.; Nowakowska, A. Polityka Zorientowana Terytorialnie Jako Metoda Adaptacji do Zmian Klimatu: Place-Based Policy as A Method for Climate Change Adaptation. Stud. Miej. 2023, 46, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grześczyk, A.; Niewitała-Re, M. Territorial and Distributional Aspects of Just Transition in the Draft Updated German National Energy and Climate Plan; Report; Reform Institute in Cooperation with Ecologic Institute: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hassink, R. Regional resilience: A promising concept to explain differences in regional economic adaptability? Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storonyanska, I.; Patytska, K.; Dub, A.; Benovska, L. «Green» transformation of coal microregions of the ukrainian-polish borderland: Problems and directions of process intensification. In Polish-Ukrainian Borderland as an Area of Transformation; Miszuk, A., Shubalyi, O., Eds.; Maria Curie-Skłodowska University Press: Lublin, Poland, 2025; pp. 325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, J.G.; Gaurav, K.; Singh, A.K.; Atul, K. Just transition beyond extraction: A spatial and comparative case study of two coal mining areas in India. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 126, 104136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, W.; Zdurco, A. The spatial dimension of coal phase-out: Exploring economic transformation and city pathways in Poland. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 99, 103058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- On the Ratification of the Paris Agreement. Law of Ukraine No. 1469-VIII of July 14, 2016. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/en/1469-19?lang=uk#Text (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Nationally Determined Contributions Registry. United Nations. Climate Change. Available online: https://unfccc.int/NDCREG (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Wang, X.; Lo, K. Just transition: A conceptual review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 82, 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hizliok, S.; Sheer, A. What Is the Just Transition and What Does It Mean for Climate Action? The London Shool of Economics and Political Science 2024. Available online: https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/explainers/what-is-the-just-transition-and-what-does-it-mean-for-climate-action/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Barca, F. An Agenda for a Reformed Cohesion Policy. A Place-Based Approach to Meeting European Union Challenges and Expectations, Independent Report Prepared at the Request of Danuta Hübner, Commissioner for Regional Policy, Brussels. 2009. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/regi/dv/barca_report_/barca_report_en.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Palavicini-Corona, E.I. Does local economic development really work? Assessing LED across Mexican municipalities. Geoforum 2013, 44, 303–315. Available online: http://econ.geo.uu.nl/peeg/peeg1224.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Neuhuber, T. One and the Same or Worlds Apart? Linking Transformative Regional Resilience and Just Transitions Through Welfare State Policies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]