Abstract

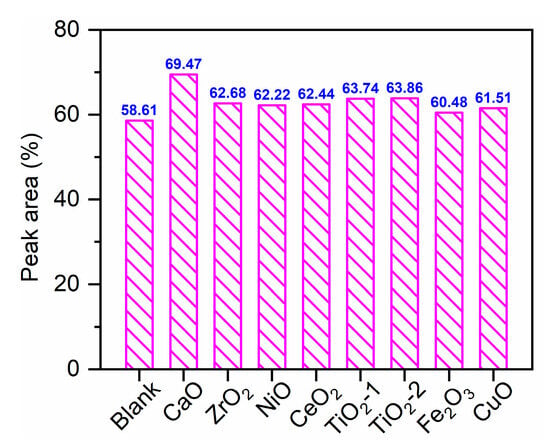

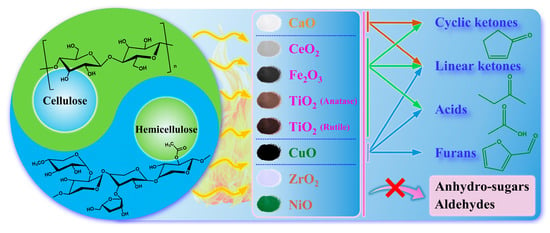

Incomplete diesel combustion emits soot and CO. The use of biomass-derived, oxygen-containing diesel additives has been proposed as an effective mitigation strategy. Among these, long-chain ethers have been widely regarded as one of the most promising additive classes. Guided by this, carbonyl compounds were targeted as intermediates for the synthesis of long-chain ethers. Py-GC/MS was used to assess eight oxides (CaO, ZrO2, NiO, CeO2, TiO2 (rutile), TiO2 (anatase), Fe2O3, CuO) during fast pyrolysis of native holocellulose. Relative content of carbonyl compounds was increased by all catalysts, with CaO exhibiting the highest value (69.47%). CaO raised the content of linear ketones from 18.25% to 27.61%, while it sharply reduced the relative content of acetic acid (from 11.56% to 3.19%). TiO2 (rutile) increased cyclic ketones from 11.09% to 15.01%. CuO boosted furans and acids to 17.48% and 17.91%, respectively. Levoglucosan dropped from 11.24% to 4.83% over CuO, which also increased furfural content from 3.25% to 5.63%.

1. Introduction

Advances in transportation and equipment electrification have increased the replacement of gasoline-powered machinery by electric drives. Nevertheless, in demanding sectors—mining, heavy-duty transport, and construction—compression-ignition engines were not readily displaced because of their superior thermal efficiency and reliability. Consequently, the development of sustainable alternatives to diesel remained of long-term practical importance [1]. Conventional diesel is composed primarily of oxygen-free hydrocarbons and under compression-ignition conditions this composition hampered complete combustion and led to particulate matter and nitrogen oxides, posing environmental and health risks [2]. Based on prior studies, long-chain ethers have been recognized as promising oxygenated fuels or blending components owing to favorable compatibility, clean combustion, and low environmental impact, making them potential next-generation alternatives to petroleum diesel [3,4,5]. Lignocellulosic biomass, intrinsically oxygenated, served as an ideal carbon source for such fuels [6]. Fast pyrolysis has yielded up to ~75 wt% bio-oil on millisecond timescales, providing an efficient route to platform compounds and liquid fuels. However, the compositional complexity of crude bio-oil has limited its direct use [7]. A petroleum-refining paradigm was adopted historically—enrich hydrocarbon-like fractions, then obtain diesel substitutes by C–C coupling and hydrodeoxygenation—but this route required near-complete deoxygenation, large hydrogen inputs, and severe conditions, rendering it cost-intensive and difficult to sustain [8,9].

To address these limitations, a hydrogen-free process chain was proposed in our previous work: in situ enrichment of carbonyls (aldehydes, ketones, and carbonyl-containing furans) by catalytic fast pyrolysis (CFP), followed by transfer hydrogenation and etherification to form long-chain ethers [10]. Techno-economic analyses indicated that CFP was cost-competitive at industrial scales while highlighting key cost drivers, such as feedstock cost, total capital investment, bio-oil yield, catalyst cost [11]. Vasalos et al. found that a 500 ton/day beechwood CFP process using ZSM-5 as the catalyst in a circulating fluidized-bed required a total investment of $78.55 million and delivered a production cost near $615/ton of upgrading bio-oil [12]. Doubling capacity to 1000 ton/day lowered unit cost to $572/ton, while feedstock price and catalyst usage strongly influenced economics. For example, biomass price from $57 to $114/ton led to higher production cost, up to $841/ton. In addition, a fourfold increase in ZSM-5 usage also caused higher production cost, up to $784/ton. Therefore, low-cost feedstocks, maximizing upgrading bio-oil yield and inexpensive catalysts are crucial in a CFP process.

To enhance carbonyl yield and selectivity in bio-oil, direct catalytic upgrading of pyrolysis vapors emerged as a key focus [13,14,15]. Prior work emphasized carboxylic-acid ketonization in bio-oil commonly using pure or mixed metal oxides as catalyst [16,17], whereas studies on real vapor mixtures were scarce. Mante et al. [18] investigated the ketonization reaction of sugar maple pyrolysis gas in the presence of different metal oxides (anatase TiO2, Ni/TiO2, Pt/TiO2, CeOx-TiO2, CeO2, ZrO2, MgO, CaO/CeO2, and Mn/TiO2) by means of a fast thermal cracker. It was shown that the ceria-based catalysts could effectively convert hydroxy-carbonyl compounds, dehydrated sugars and carboxylic acids into acetone, 2-butanone, pentanone, C6/C7 ketone, cyclopentanone and 2-cyclopentanone, with the highest ketonization activity in pure CeO2, obtaining ketone products in 23.5% carbon yield. Gupta et al. [19] explored the effect of CaO on the catalytic pyrolysis of oak by Py-GC/MS at 500 °C. The results showed that CaOOH (CaO partial hydration product) promoted the conversion of carboxylic acids to fatty ketones and furfural to cyclopentanone/2-cyclopentenone. Shao et al. [20] investigated the effect of CeO2 on the pyrolysis gas of sugarcane bagasse by using a two-stage fixed bed, and the highest ketone yield (33.68%) was obtained at 380 °C. The team further investigated the ketonization reaction of pyrolysis gases from bagasse holocellulose using ZrO2 as catalyst, and found that the highest carbon yield of carbonyl compounds (aldehydes and ketones) was obtained at 400 °C (53.59%) [21]. A series of Fe-doped CeO2 catalysts were prepared for the catalytic ketonization reaction of xylan by Wu et al. [22]. It was found by characterization that moderate amount of Fe doping (20–33%) significantly increased the oxygen vacancies and basic sites of CeO2. The catalytic experiments showed that the ketone yield of 33% Fe-CeO2 was 38% higher than that of pure CeO2, and the selectivity for linear ketones (acetone, 2-butanone) of 57% Fe-CeO2 was up to 85%.

Despite these insights, a systematic understanding of how individual oxides act across the multi-pathway network and how crystal phase, acidity/basicity, and vacancies interact remained limited. More specifically, how do basic, acidic or reducible oxide surfaces redirect anhydrosugars and sugar-fragment intermediates into linear ketones, cyclic ketones, acids, and furans? Which surface properties govern the formation of ketones? Can acetic acid be selectively suppressed or converted (via surface ketonization) while increasing targeted carbonyls? Do rutile and anatase TiO2 exhibit distinct product distribution due to differences in acidity/defect structures? Therefore, native holocellulose was employed, and Py-GC/MS was used to examine CaO, ZrO2, NiO, CeO2, TiO2 (rutile/anatase), Fe2O3, and CuO for their effects on pyrolysis product distributions, with emphasis on carbonyl compounds. The findings provided fundamental data and mechanistic insight for controlling oxygenated bio-oil composition and producing long-chain ethers.

2. Materials and Methods

The native holocellulose used in this work was prepared from corn stover collected from agricultural fields in Lianyungang, Jiangsu Province, China. The corn stover was dried, ground, and sieved to obtain 80–100 mesh particles. The native holocellulose was prepared via delignification [23]. Briefly, 20 g of biomass was wrapped in 300-mesh gauze and placed in a Soxhlet extractor (Beijing Beibo Bomei Glass Co. Ltd. Beijing, China) containing benzene/ethanol (2:1, v/v). Extraction was performed at 90 °C for 13 h. After air-drying, the extractive-free biomass was transferred to a conical flask, to which 650 mL of deionized water (32.5 mL/g dry biomass) was added. The mixture was then heated to 75 °C in a water bath under stirring at 1000 rpm. Hourly, 5 mL of glacial acetic acid (0.25 mL/g dry biomass) and 6 g of sodium chlorite (0.3 g/g dry biomass) were added to the flask, and this process was repeated four times. During the reaction, chlorine dioxide (ClO2) and chlorine gas (Cl2) were generated in situ, thereby promoting lignin oxidation and depolymerization. After 4 h, the suspension was cooled to room temperature and filtered under vacuum. The filter cake was rinsed with deionized water until the filtrate reached neutral pH, followed by three washes with acetone. The resulting solid was dried in an oven at 105 °C for 24 h and stored in a desiccator until use. This study evaluated eight nanoscale metal oxides—CaO, ZrO2, NiO, CeO2, TiO2 (rutile, TiO2-1), TiO2 (anatase, TiO2-2), Fe2O3, and CuO—as catalysts. All nanoscale metal oxides (analytical grade) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co. Ltd. Shanghai, China. The pore structure characteristics of the catalyst were determined using a specific surface area and porosity analyzer (BSD-PM1, Beijing, China). Specific surface area and pore size distribution were calculated based on the BET and BJH methods [24], and the results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Specific surface area, pore volume, and average pore diameter of catalysts.

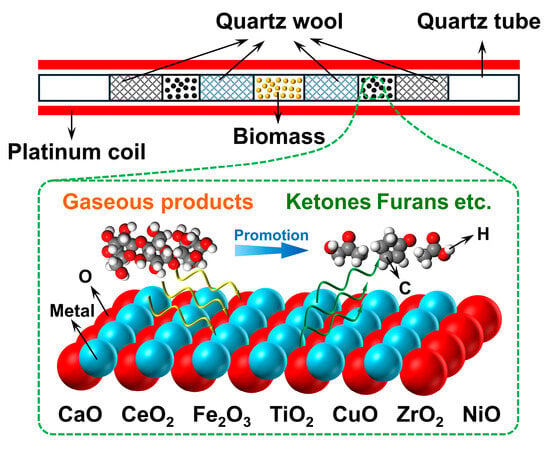

Catalytic fast pyrolysis of holocellulose over these oxides was examined using a Pyroprobe 6200 (CDS Analytical, Oxford, PA, USA). For sample preparation, 0.50 mg of native holocellulose was weighed and placed at the center of a miniature quartz tube, secured at both ends with quartz wool. Two portions of 0.50 mg metal oxide catalyst were weighed and placed on both sides of the holocellulose bed. The catalyst/holocellulose configuration is shown in Figure 1. The catalysts were arranged on both sides of the holocellulose to form a fixed-bed configuration, ensuring that pyrolysis vapors passed through the catalyst layer. Quartz wool separated the catalyst from the holocellulose, ensuring ex situ catalytic pyrolysis. Under nitrogen, the quartz tube was rapidly heated from ambient temperature to 600 °C using a platinum coil at 20 °C/ms, then held for 15 s to ensure complete pyrolysis. For noncatalytic controls, an equal volume of quartz sand was placed on both sides of the holocellulose to maintain a consistent gas-phase residence time.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of pyrolysis and catalytic conversion over metal oxides.

Volatile products were analyzed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS; Agilent 7890B/5977, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Pyrolysis volatiles were immediately transferred to the GC-MS and separated on an Rxi-VMS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 1.4 μm); the injector temperature was maintained at 300 °C. High-purity helium (99.999%) served as the carrier gas at 1.0 mL/min with a split ratio of 1:50. The GC oven program was: 40 °C for 3 min, ramp 4 °C/min to 280 °C, then hold for 3 min. The MS operated in electron-ionization (EI) mode at 70 eV, scanning m/z 45–450. Compounds were identified from total-ion chromatograms using the NIST 17 mass spectral library. In all experiments, the holocellulose mass was held constant, and GC-MS quantitation assumed a linear relationship between chromatographic peak area and compound quantity [25]. Accordingly, product variations were obtained from normalized peak areas across conditions, and relative contents of products were derived from peak-area percentages. Each experiment was repeated at least three times to ensure data reproducibility and each data-point in the tables and figures below represented the average values.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Catalytic Effects on Product Distribution

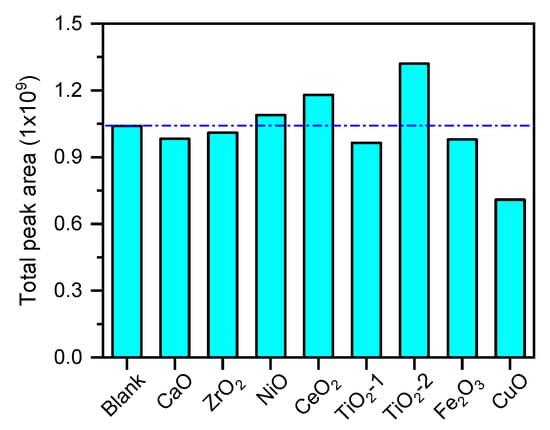

Figure 2 presents the total GC–MS peak areas for all detected products from native holocellulose pyrolysis under both noncatalytic and metal-oxide-catalyzed conditions. The total peak area under noncatalytic conditions was approximately 1.04 × 109. The catalysts exhibited significant effects on total condensable product yield, as reflected by the total peak area: TiO2-2 increased the peak area to 1.32 × 109. CeO2 and NiO also enhanced the peak area, with increases of approximately 13.46% and 4.81%, respectively; by contrast, CaO, ZrO2, TiO2-1, and Fe2O3 slightly reduced it. Conversely, CuO substantially decreased the total peak area to 0.71 × 109. Given the consistent experimental conditions, the total GC–MS peak area serves as a semiquantitative measure of the relative abundance of condensable organic vapors. Based on this, it can be inferred that oxides such as TiO2-2 and CeO2, which feature specific crystal facets, surface acid sites, and tunable oxygen vacancies, effectively promote the formation and stabilization of liquid-phase products while suppressing excessive gaseous by-products, thereby increasing the overall liquid yield. This finding aligns with previous research demonstrating that solid acids and metal oxides with oxygen defects can increase organic liquid yield and GC–MS signal intensity in fast pyrolysis [26]. In contrast, CuO and other strongly basic or oxidizing surfaces promoted the formation of small-molecule gases (CO, CO2, light hydrocarbons) and reduce the yield of condensable vapors by facilitating condensation–carbonization reactions, thereby decreasing the total product peak area. This trend is consistent with systematic studies of metal-oxide acidity/basicity in lignocellulosic pyrolysis, which show that strongly basic oxides favor conversion of oxygenated fragments into gaseous products, thereby reducing the relative proportion of the condensable liquid phase [27].

Figure 2.

Total peak area for all products of holocellulose pyrolysis and catalytic pyrolysis.

All the identified compounds were classified into seven groups based on functional groups to clearly present changes in product distributions, as shown in Table 2. In noncatalytic holocellulose pyrolysis products, aldehydes (21.60%), linear ketones (18.25%), and sugars (14.99%) exhibited high selectivity, while cyclic ketones were measured to be lower (11.09%). The other category (7.83%) was found to contain minor amounts of hydrocarbons, esters, alcohols, and lignin-derived aromatic compounds. The product distributions were significantly altered by the introduction of various catalysts, and a pronounced selectivity control effect was demonstrated. Specifically, CuO exhibited the highest catalytic activity for furan formation, achieving a selectivity of 17.48%, which was substantially higher than that of any other catalyst. CaO and TiO2-1 were also shown to promote furan formation strongly, yielding 14.51% and 14.22%, respectively. These behaviors were interpreted as being driven by distinct catalytic mechanisms: the strong basicity of CaO was considered to have facilitated sugar cracking, whereas furan production was promoted on TiO2-1 via surface acidity and oxygen-vacancy sites. In contrast, ZrO2, NiO, TiO2-2, and Fe2O3 were found to have minimal effects on furan formation, while CeO2 significantly suppressed it, yielding only 11.99% selectivity.

Table 2.

Peak area% of identified products from non–catalytic and catalytic pyrolysis of holocellulose.

With respect to aldehyde formation, only NiO (22.12%) and ZrO2 (21.80%) showed enhanced selectivity; all other catalysts were found to suppress aldehyde production compared to the noncatalytic case. Notably, the formation of linear ketones was enhanced by all metal oxides. Among them, CaO, CuO, TiO2-1, Fe2O3, and CeO2 exhibited particularly strong catalytic effects. In particular, CaO and CuO were the most effective, achieving linear-ketone selectivities of 27.61% and 22.52%, respectively, which were significantly higher than those of other catalysts. It was plausible that acidic intermediates were effectively neutralized by these catalysts and that the conversion of sugar intermediates to linear ketones was accelerated via dehydration, C–C cleavage, and ketonization [28]. For cyclic-ketone formation, TiO2-1 was observed to provide the most substantial enhancement (15.01%), followed by CaO (14.37%), CeO2 (13.90%), and TiO2-2 (12.91%). In contrast, ZrO2 (11.34%) and NiO (11.30%) had minimal effects, whereas cyclic-ketone formation was significantly suppressed by CuO (9.16%). Owing to its strong oxidation, dehydrogenation, and decarboxylation capabilities, CuO was inferred to have rapidly oxidized enol-dicarbonyl and other cyclic precursors into acids or to have further fragmented them, thereby reducing cyclic-ketone yields and significantly increasing acid production, consistent with reports that acid and CO2/COx formation were promoted by CuO during biomass pyrolysis [29].

Regarding acid formation, the strongest catalytic effect was observed for CuO (17.91%), followed by Fe2O3 (16.14%) and CeO2 (14.34%). In stark contrast, acid formation was strongly suppressed by CaO, yielding only 3.88% selectivity. This trend was found to align with the Mars–van Krevelen mechanism operative on reducible metal oxides (e.g., CuO, Fe2O3, CeO2, TiO2), wherein alcohol/aldehyde intermediates from sugar cleavage were selectively dehydrogenated/oxidized at metal–oxygen sites, thereby promoting carboxylic-acid formation. Conversely, ketonization/decarboxylation was promoted by strong basic O2− sites on CaO, carboxylic acids were rapidly consumed, and linear ketones and CO2 were produced, explaining the markedly reduced acid selectivity and the concurrent increase in linear ketones (27.61%) observed with CaO [30].

Sugar selectivity was generally decreased by reducible metal oxides. The extent of this reduction was found to correlate positively with the catalyst’s capacity to promote secondary reactions such as dehydration, dehydrogenation, and oxidation: the strongest effect was observed for CuO, which reduced selectivity to 7.83%, followed by TiO2-1 (9.23%), TiO2-2 (10.15%), Fe2O3 (11.67%), and CeO2 (11.61%). All values were significantly lower than that of noncatalytic pyrolysis (14.99%). This behavior was attributed to Lewis-acid sites that catalyzed the dehydration and ring-opening rearrangement/condensation of pyran-/furan-type sugar fragments, while surface reducible oxygen species further converted primary alcohols and aldehydes into ketones and acids, collectively reducing sugar selectivity. On CuO, the cascade of dehydration followed by dehydrogenation/oxidation was most pronounced, resulting in the highest acid selectivity and the lowest sugar selectivity. In contrast, sugar selectivity was only slightly reduced by CaO (12.48%), indicating that strong basic sites were directing sugar units toward enolization, aldol condensation, and ketonization rather than deep oxidation; consequently, acid formation was suppressed and linear ketones were preferentially generated [30].

3.2. Catalytic Effects on Sugars and Furans

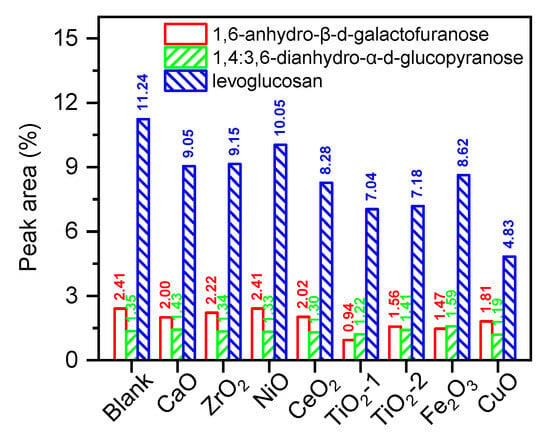

Figure 3 further illustrates the distribution of three characteristic carbohydrate derivatives—1,6-anhydro-β-D-galactofuranose, 1,4:3,6-dianhydro-α-D-glucopyranose, and levoglucosan (LG)—under the influence of various metal oxide catalysts during holocellulose pyrolysis. LG exhibited the highest selectivity (11.24%) among the sugar products from noncatalytic pyrolysis, suggesting that holocellulose primarily underwent end-group transglycosylation and intramolecular dehydration, thereby retaining the pyranose skeleton to form LG. The proportions of the other two anhydrosugars were significantly lower (2.41% and 1.35%), indicating that rapid heating favored single-step transglycosylation over multistep dehydration rearrangement. The addition of metal oxides generally reduced LG selectivity. The selectivity increased in the order: CuO (4.83%) < TiO2-1 (7.04%) < TiO2-2 (7.18%) < CeO2 (8.28%) < Fe2O3 (8.62%) < CaO (9.05%) < ZrO2 (9.15%) < NiO (10.05%). The selectivities of the two anhydrosugars also decreased overall, with the most pronounced reduction being observed for TiO2-1 (1,6-anhydro-β-D-galactofuranose: 0.94%; 1,4:3,6-dianhydro-α-D-glucopyranose: 1.22%). This overall trend indicated that each oxide attenuated the primary dehydration/transglycosylation pathways, which preserved the sugar skeleton, to varying degrees and redirected intermediates toward secondary reactions, including cleavage, cyclization, and oxidation. Mechanistically, the formation of anhydrosugars required complete preservation of the sugar ring and glycosidic bond structure, together with the kinetic favorability of intramolecular dehydration. In the presence of surface Lewis acid sites or reducible oxygen, C–O and C–C bonds in sugar intermediates were preferentially activated. This promoted reactions such as dehydrogenation, aldol condensation, ring-opening rearrangement, and subsequent ketonization/oxidation, thereby leading to significant attenuation of the sugar-derived signals. CeO2 and Fe2O3, leveraging their redox pairs (Ce4+/Ce3+, Fe3+/Fe2+) and oxygen vacancies, facilitated mild dehydrogenation and selective oxidation of polyols/hemiacetals, thereby reducing LG yield and enhancing subsequent ketone/acid selectivity [31]. CuO exhibited the most pronounced suppression of LG and the strongest acid-forming effect. This indicated that the Mars–van Krevelen cycle, facilitated by highly mobile surface oxygen, rapidly oxidized sugar intermediates and primary LG into acidic products via C–C cleavage, thereby achieving the most thorough deep-conversion pathway (sugars to acids/COx). This behavior was consistent with literature reports that CuO significantly enhanced acid production and suppressed the formation of reducing oxygenates in biomass catalytic pyrolysis [29]. In contrast, although CaO also reduced LG yield, the decrease was relatively modest and was accompanied by a significant increase in linear ketones (Table 2). This reflected a dominant reaction pathway involving α-hydrogen deprotonation, enolization, aldol condensation, and ketonization, driven by strong solid-base O2− sites. This pathway consumed sugar intermediates while avoiding deep oxidation, thereby suppressing acid formation and only moderately attenuating the sugar-derived signals [30]. It was inferred that although the amphoteric nature of ZrO2 and the moderate acidity of NiO could initiate partial dehydration and ring-opening, their strength was insufficient to promote subsequent deep-conversion reactions, resulting in only mild LG depletion.

Figure 3.

The GC–MS peak area ratio of sugar products from holocellulose pyrolysis and catalytic pyrolysis.

The analysis of furan products in Table 3 revealed the diversion effect and secondary reaction characteristics imparted by different metal oxides on the transformation of C6 intermediates into C5/C4 oxygenated cyclic compounds. On the whole, a significant enhancement in selectivity toward furan products was observed with CuO, particularly furfural (from 3.25% to 5.63%), furan (from 0.33% to 1.15%), and γ-butyrolactone (from 0.58% to 1.14%). In contrast, the selectivity for 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) was markedly reduced from 1.93% to 1.34%. This suggested that the highly mobile surface oxygen of CuO preferentially oxidized sugar/polyol intermediates toward furfural and lactone formation, and was accompanied by C–C cleavage. This reflected a deep conversion pathway governed by dehydrogenation and selective oxidation [29]. Secondary reactions were enhanced by TiO2-1, particularly dehydration, decarbonylation, and decarboxylation. This led to a significant increase in the selectivity for furan (1.19%), furfural (4.01%), and 3-methylfuran (0.19%; detected only with TiO2-1, CuO, and CeO2 catalysts), while the selectivity for 2-furanmethanol (1.61%) and HMF (1.25%) was significantly reduced. A similar influence on furan product distribution was observed for TiO2-2 as for TiO2-1, though the changes were less pronounced: furan (0.43%), furfural (3.77%), 2-furanmethanol (1.97%), and HMF (1.53%), suggesting that TiO2-2 possessed lower acidity and fewer oxygen vacancies than TiO2-1, resulting in a weaker driving force to promote secondary reactions [32]. The regulation of furan products by CaO was reflected by a slight increase in furfural selectivity (3.51%), a significant enhancement in γ-butyrolactone yield (0.82%), and a decrease in HMF (1.49%), indicating that CaO promoted α-hydrogen deprotonation and enolization via its O2− sites, thereby inhibiting deep dehydration. Some C6 fragments were converted to C5 furans through retro-aldol dehydration, whereas the remaining intermediates were diverted toward ketonization and lactonization pathways rather than oxidation [33]. Fe2O3 and CeO2, as reducible oxides, exhibited a character of mild oxidation and limited dehydration: HMF selectivity was decreased (to 1.63% and 1.46%, respectively) and γ-butyrolactone selectivity was increased (to 0.74% and 0.73%, respectively). ZrO2 and NiO had a minimal effect on furan product distribution, though a slight decrease in HMF selectivity was still observed.

Table 3.

Mean peak area% of identified furans.

3.3. Catalytic Effects on Acids, Aldehydes and Ketones

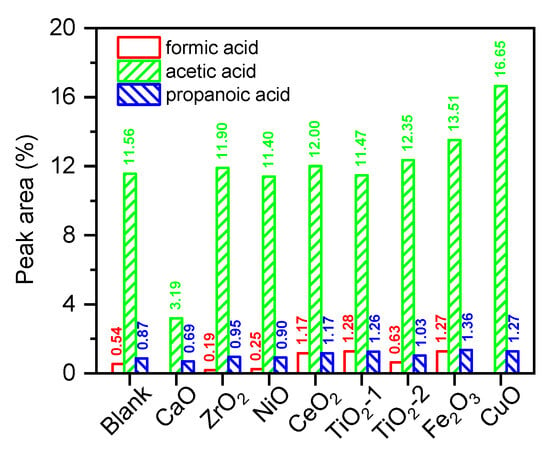

Figure 4 shows that among the three representative low-carbon carboxylic acids—formic acid, acetic acid, and propionic acid—acetic acid had the highest proportion and its selectivity was highly dependent on the catalyst type. Acetic acid selectivity was generally enhanced by reducible oxides. The most substantial increase was observed for CuO, from 11.56% (non–catalytic) to 16.65%, followed by Fe2O3 (13.51%), TiO2-2 (12.35%), and CeO2 (12.00%). In contrast, TiO2-1, NiO, and ZrO2 had negligible effects. Conversely, the strong solid base CaO significantly suppressed acetic acid formation, reducing its selectivity to 3.19%. These results highlighted two competitive mechanisms. First, the Mars–van Krevelen cycle was operative on reducible oxides (e.g., CuO, Fe2O3, CeO2), in which surface–active oxygen species selectively dehydrogenated and mildly oxidized alcohol/aldehyde intermediates from sugar cleavage, thereby promoting acetic acid formation. CuO exhibited the strongest effect, due to the facile reduction and high oxygen mobility of the Cu2+/Cu+ redox couple, leading to the most significant enhancement in acetic acid yield [29]. Second, O2− sites on the CaO surface were highly active for salt formation (salinization) and subsequent ketonization/decarboxylation of carboxylic acids. Specifically, acetic acid first formed calcium acetate, which then underwent bimolecular ketonization to produce acetone, CO2, and H2O, thereby significantly reducing the detectable free acetic acid in GC–MS analysis [34]. This pathway also accounted for the experimental results presented in Table 2, in which CaO catalysis led to a significant increase in linear ketone yield.

Figure 4.

The GC–MS peak area ratio of acid products from holocellulose pyrolysis and catalytic pyrolysis.

Based on the comprehensive analysis, the primary source of acetic acid was the thermal cracking and deacetylation of acetyl groups, followed by ketene hydration [35]. Catalysts with stronger acidity or redox activity (e.g., TiO2, Fe2O3, CuO, CeO2) were found to accelerate both acetyl group dissociation and the secondary oxidation of carbonyl/aldehyde intermediates, thereby amplifying the acetic acid signal. Concurrently, these catalytic sites promoted β-cleavage of C2–C3 fragments, generating minor amounts of propionic and formic acids [36]. In contrast, the strong basicity of CaO neutralized acidic intermediates and captured acetic acid as solid calcium acetate, effectively removing it from the volatile phase and thereby drastically reducing the detectable acidity in GC–MS. This observation aligned with the established consensus that alkaline earth oxides suppress acid formation and promote decarboxylation/decarbonylation pathways during biomass pyrolysis [37].

A detailed analysis of the aldehyde products in Table 4 revealed that hydroxyacetaldehyde (HAA) was the predominant aldehyde, with a selectivity of 15.35% during non–catalytic holocellulose pyrolysis. However, HAA was significantly consumed by oxides with strong Lewis acidity and reducibility, which concurrently increased the yield of unsaturated small–molecule aldehydes. For instance, HAA selectivity was reduced to 7.53% by TiO2-1, while the selectivities of 2-propenal and 2-butenal were increased to 1.08% and 1.69%, respectively. Similarly, HAA was decreased to 8.76% and 9.74% by CuO and Fe2O3, respectively, while 2-propenal formation was enhanced to 2.14% and 1.21%. In contrast, the amphoteric oxide ZrO2 and the moderately acidic NiO had little effect on HAA selectivity, which remained ~15% (15.06% and 15.49%, respectively). HAA was primarily formed via retro–aldol cleavage and ring–opening rearrangement of glucose fragments during fast pyrolysis, and it was readily dehydrated on acid/redox sites to form C3 and C4 unsaturated aldehydes or was oxidized to carboxylic acids [33].

Table 4.

Mean peak area% of identified aldehydes and ketones.

The significant increase in 2-propenal yield observed with CuO, Fe2O3, and TiO2-1 was attributed to the synergistic acid- and redox-site-catalyzed dehydration of HAA and glyceraldehyde intermediates, a mechanism consistent with the established pathway for solid-acid-catalyzed dehydration of C3 polyols to form 2-propenal [38]. In contrast, HAA selectivity was reduced from 15.35% to 8.60% by the strong solid base CaO, while the selectivities of propanal (0.75%), 2-butenal (1.34%), and the branched-chain aldehyde 2,2-dimethyl-propanal (0.51%) were markedly increased. These results suggested that α-hydrogen deprotonation and enolization were induced by CaO via its O2− sites, promoting aldol condensation (including intramolecular reactions) and β-elimination, thereby redirecting C6 fragments toward C3–C4 aldehydes. Simultaneously, partial carboxylation followed by ketonization/decarboxylation allowed aldehydes and acids to undergo dynamic redistribution on the alkaline surface [39]. Furthermore, the selectivity of butanedial varied only modestly across all catalytic systems (3.67–4.06%), indicating that it functioned as a relatively stable intermediate formed during early-stage cracking, with low sensitivity to catalyst surface properties.

Table 4 revealed significant differences in the production of linear ketones among the metal oxide catalysts. First, small–molecule linear ketones underwent sequential transformations involving dehydration, cracking, and dehydrogenation/dehydroxylation. For instance, the selectivity of 1-hydroxy-2-propanone was 6.92% in non-catalytic pyrolysis. Following catalysis by TiO2-1, Fe2O3, and CuO, its selectivity was decreased to 5.38%, 5.86%, and 4.81%, respectively, while the selectivity of acetone was concurrently increased to 9.35%, 8.94%, and 11.43%. This inverse relationship suggested that the dehydration–dehydrogenation pathway converting hydroxyketones to simple ketones was accelerated. Similarly, acetone selectivity was increased to 10.11% by CaO, and the yields of 2-butanone (from 0.47% to 3.00%) and 2-pentanone (from 0.19% to 0.92%) were markedly enhanced, consistent with the established role of basic sites in promoting retro-aldol cleavage and ketonization, thereby stabilizing methyl-ketone intermediates [37]. Conversely, the selectivity for unsaturated and dicarbonyl linear ketones was significantly increased in the presence of acidic oxides. For example, the selectivities of 3-buten-2-one and 2,3-butanedione were enhanced to 0.96% and 1.80%, respectively, by TiO2-1, indicating that Lewis acid centers and surface defect sites catalyzed a reaction sequence involving dehydration, rearrangement, and decarbonylation [40]. In contrast, ZrO2 and NiO exhibited milder catalytic effects, exerting a lesser influence on the formation of linear ketones. The formation of ketones such as acetone, 2,3-butanedione, and 3-pentanone was significantly enhanced in the presence of CuO and TiO2-1. The formation of 2-butanone and 1-hydroxy-2-propanone was promoted by CaO via its strong basicity, whereas the influence of ZrO2 and NiO was comparatively weak, leading to only slight increases in the selectivity of products such as acetone and 1-hydroxy-2-butanone.

Cyclic ketones were formed through the rearrangement and condensation of sugar and furan precursors, reflecting their transformation into cyclic structures. Catalysis by TiO2-1 resulted in peak selectivities of 2-cyclopenten-1-one (1.93%), 1,2-cyclopentanedione (0.49%), 2-hydroxy-2-cyclopenten-1-one (4.71%), and 3-methyl-1,2-cyclopentanedione (4.38%). This trend was consistent with the established role of acid centers in promoting the rearrangement and cyclization of furan alcohols to form cyclopentenones and cyclohexenones [41]. TiO2-2 had a minimal effect on the formation of cyclic ketones. Notably, the selectivity for 2-cyclopenten-1-one reached only 1.23% under TiO2-2 catalysis. This was likely attributable to the weaker acidic sites and distinct surface structure of the anatase phase, resulting in less pronounced promotion of cyclization reactions compared to the rutile phase [33]. Cyclic ketones (particularly substituted cyclopentenones) were significantly enhanced by CaO. For instance, the selectivities of 2-methyl-2-cyclopenten-1-one and 2,3-dimethyl-2-cyclopenten-1-one increased from 1.03% to 1.75% and from 0.48% to 1.27%, respectively. The strong basicity of CaO was proposed to promote sugar cracking and enolization, thereby generating favorable precursor intermediates for the formation of cyclic ketones. Despite its strong reducibility, CuO exhibited an inhibitory effect on the formation of cyclic ketones, particularly for 2-hydroxy-2-cyclopenten-1-one, which reached a selectivity of only 1.45%. Catalysis by CeO2 resulted in distinct characteristics for the formation of cyclic ketones, notably achieving a selectivity of 4.56% for 2-hydroxy-2-cyclopenten-1-one. A comparison with the furan product data in Table 3 revealed that both CaO and TiO2-1 exhibited strong catalytic activity for the formation of cyclic ketones and furan products. For example, the formation of 2-methyl-2-cyclopenten-1-one was enhanced by CaO, and the production of furans such as furfural was promoted. This indicated that CaO facilitated both sugar cracking and the production of oxygenated products, primarily through its strong basicity and catalytic cracking activity [32]. Furthermore, sugar cracking to form cyclic ketones was promoted and furan production was enhanced by TiO2-1 through the synergistic effect of its Lewis acid sites and oxygen vacancies. In contrast, other catalysts, such as ZrO2 and NiO, exhibited weaker catalytic effects, primarily facilitating mild cracking and oxidation reactions.

3.4. Catalytic Effects on Carbonyl Compounds and Formation Mechanism

Figure 5 presents the relative distribution of non–acidic carbonyl compounds—primarily aldehydes, ketones, and carbonyl-containing furans—from holocellulose pyrolysis, demonstrating that all metal oxides enhanced carbonyl compound selectivity to varying degrees. CaO exhibited the most pronounced effect, achieving 69.47% selectivity—an increase of approximately 10.9% relative to non–catalytic pyrolysis. TiO2-1 and TiO2-2 followed (63.74% and 63.86%), while NiO, CeO2, and ZrO2 showed moderate enhancements (62.22–62.68%). Fe2O3 and CuO provided the smallest increases, yielding 60.48% and 61.51%, respectively. Table 2 and Table 4 revealed that CaO increased linear ketone selectivity from 18.25% to 27.61%, with significant enrichment of specific monomers including 2-butanone, 2-pentanone, 1-hydroxy-2-propanone, 1-hydroxy-2-butanone, and 1-acetoxy-2-propanone. Additionally, several cyclopentenones, such as 2-methyl-2-cyclopenten-1-one, were enriched, culminating in the highest total carbonyl selectivity observed for CaO. This mechanism was attributed to the O2− sites of the solid base mediating α-hydrogen deprotonation and enolization of sugars and acid intermediates, followed by aldol condensation, ketonization, and partial decarboxylation. This pathway rapidly consumed acids, converting them into symmetrical and asymmetrical ketones [30]. Both crystal phases of TiO2 also enhanced carbonyl compound selectivity, but their pathway favored cyclization coupled with mild oxidation: TiO2-1 significantly increased cyclic ketone selectivity (from 11.09% to 15.01%), notably enriching 2-hydroxy-2-cyclopenten-1-one and 3-methyl-1,2-cyclopentanedione (to 4.71% and 4.38%, respectively). Conversely, TiO2-1 reduced the yield of primary aldehydes such as HAA from 21.60% to 16.63%, demonstrating a secondary conversion characteristic of aldehyde to ketone or cyclic-ketone. This was consistent with the known mechanism whereby Lewis acid sites and oxygen vacancies on the TiO2 surface synergistically polarized C=O and C–O bonds, promoting dehydration and intramolecular cyclization [32]. The enhanced selectivity for carbonyl compounds over CeO2 arose from the combined effects of mild oxidation and moderate enrichment of cyclic ketones: the combined yield of linear and cyclic ketones was increased from 29.34% to 35.24%, while aldehyde yield was decreased to 18.73% (Table 2). This indicated that the Ce4+/Ce3+ redox pairs, in concert with oxygen vacancies, selectively dehydrogenated and oxidized aldehyde and alcohol intermediates, promoting a stepwise conversion pathway from aldehydes to ketones and furanones [31]. ZrO2 and NiO maintained a high aldehyde selectivity (21.80% and 22.12%, respectively; Table 2) but only mildly enhanced the formation of ketones, achieving ~19% for linear ketones and ~11% for cyclic ketones. Consequently, they exhibited only a moderate overall increase in carbonyl compounds as shown in Figure 5. Although CuO significantly enhanced the selectivity of carbonyl-containing furans (e.g., furfural and 2(5H)-furanone) and increased acetone selectivity to 11.43%, its highly active surface oxygen species over-oxidized primary aldehydes and ketones to carboxylic acids via C–C cleavage. It should be emphasized that the trend in Figure 5 was consistent with the marked decline of sugars in Figure 3 and the marked increase in acids on CuO/Fe2O3 and the marked decrease on CaO in Figure 4. The relative content of carbonyl compounds in this study differed from that reported by Liu et al. (51.4%) due to variations in biomass sources, holocellulose preparation methods, reaction temperatures, and other conditions. However, the product distribution patterns remained largely consistent [42]. Compared to pretreatment techniques such as torrefaction, CaO-catalyzed fast pyrolysis significantly increased the relative content of carbonyl compounds [43].

Figure 5.

GC–MS peak area ratio of carbonyl compounds from pyrolysis and catalytic pyrolysis.

The reaction network for cellulose and hemicellulose during catalytic pyrolysis comprised three primary pathways, as illustrated in Figure 6: (1) a dehydration and sugar rearrangement pathway yielding anhydrosugars (e.g., LG) and furans; (2) a cleavage and retro–aldol condensation pathway, accompanied by secondary condensation, producing linear and cyclic ketones; (3) a deacetylation and oxidative cracking pathway generating low–molecular–weight carboxylic acids, primarily acetic acid, along with minor amounts of formic and propionic acid. First, cellulose underwent transglycosylation and dehydration, thereby forming LG—a classic primary pyrolysis pathway. This pathway dominated under weak to moderate acidic conditions, whereas strong Lewis acids and metal oxide surface defects promoted secondary reactions of LG [44]. A comparison with Figure 3 revealed that all metal oxides significantly reduced LG yield compared to non–catalytic pyrolysis. The inhibitory strength decreased in the order: CuO > TiO2 > CeO2 > Fe2O3 ≈ CaO ≈ ZrO2, with NiO exhibiting the weakest effect. This indicated that the strong surface acidity and high oxidation potential of CuO and TiO2 were effective in disrupting LG stabilization, thereby triggering subsequent cracking and rearrangement reactions [44]. Correspondingly, the total yield of carbonyl-containing volatile compounds (ketones, aldehydes, and carbonyl-containing furans) shown in Figure 5 was higher for all catalytic conditions compared with the non–catalytic process, which indirectly confirmed the rapid conversion of LG. Hemicellulose, which is rich in acetylated xylan, generated furfural through deacetylation and subsequent triple-dehydration pathways. As shown in Table 3, CuO most significantly enhanced furfural yield, followed by TiO2-1, TiO2-2, and Fe2O3, whereas CeO2 slightly suppressed it. This trend aligned with the oxidative dehydrogenation capability of CuO and the Lewis-acid activation by TiO2 of acetyl groups in hemicellulose, both of which accelerated the dehydration cascade of pentose intermediates [45]. Notably, furanols could undergo the Piancatelli rearrangement at acid sites to form cyclopentenone structures. Table 4 demonstrated that TiO2-1 most effectively promoted the formation of 2-cyclopenten-1-one and 3-methyl-1,2-cyclopentanedione, a finding that was consistent with the abundance of Lewis acid sites on TiO2-1, which readily facilitated the rearrangement of furan derivatives to cyclopentenones [46]. Regarding linear ketones, Table 4 indicated that the yields of acetone and its precursor, 1-hydroxy-2-propanone, increased significantly over CuO and CaO but were lower over NiO. This suggested that CuO and CaO preferentially catalyzed the retro–aldol cleavage of the C6 sugar skeleton, generating C2–C3 fragments (e.g., HAA, glyoxal, and acetone precursors) that were subsequently converted to acetone via ketonization and decarbonylation. Integrating Figure 3 and Figure 4, CuO significantly enhanced acetic acid yield while drastically reduced LG, indicating that it opened a pathway of sugar to acid/ketone. In this pathway, LG formation was suppressed, leading to the accumulation of HAA and acetyl fragments, which subsequently underwent oxidation and ketonization to produce acetic acid and acetone [47]. In contrast, although TiO2-1 provided a limited enhancement in acetone yield, it strongly promoted the formation of cyclic ketones. This indicated a preference for the acid-catalyzed rearrangement and condensation of furans and unsaturated carbonyl compounds into cyclopentenones, rather than the ketonization of small-molecule acids to form acetone. Regarding acid products, Figure 4 showed that acetic acid yield was highest over CuO, followed by Fe2O3 and TiO2-2, while CeO2 and ZrO2 produced yields comparable to non–catalytic pyrolysis. This trend was linked to the combined effects of hemicellulose deacetylation (direct acetic acid release) and the oxidation and asymmetric cleavage of C2 and C3 fragments derived from cellulose chain scission [45]. The strong oxidative and dehydrogenation properties of CuO drove fragments along the energetically favorable pathway of aldehyde to acid, leading to a substantial increase in acetic acid yield. The concurrent increase in acetone yield over both CuO and CaO reflected the parallel and interconnected nature of the acid-ketone branches: acetic acid could undergo surface ketonization on the oxide surface, or carbonyl condensation between fragments could generate higher ketones [30]. Although TiO2-1 and TiO2-2 promoted acetic acid formation to some extent, their primary catalytic contribution was enhancing cyclization and rearrangement reactions, which explained the synergistic effect observed: an increase in cyclic ketones coupled with a decrease in LG and furanose derivatives [46].

Figure 6.

Reaction network for product formation over metal oxides.

4. Conclusions

The effects of eight metal oxides—CaO, ZrO2, NiO, CeO2, TiO2-1 (Rutile), TiO2-2 (Anatase), Fe2O3, and CuO—on the product distribution from the fast pyrolysis of native holocellulose were systematically investigated, with particular focus on carbonyl compounds. The total GC–MS peak area was substantially increased by TiO2-2 (from 1.04 × 109 to 1.32 × 109) and was decreased by CuO (to 0.71 × 109). All catalysts increased the overall selectivity for carbonyl compounds (aldehydes, ketones, and carbonyl-containing furans), with CaO exhibiting the highest value at 69.47%—an increase of approximately 10.9% over the non-catalytic pyrolysis of 58.61%. CaO dramatically increased the selectivity of linear ketones from 18.25% to 27.61%, significantly enhancing the selectivity of 2-butanone (0.47% to 3.00%), 2-pentanone (0.19% to 0.92%), and acetone (6.17% to 10.11%); CuO also raised acetone to 11.43%. TiO2-1 significantly increased cyclic-ketone selectivity from 11.09% to 15.01%, notably enriching 2-hydroxy-2-cyclopenten-1-one (4.71%) and 3-methyl-1,2-cyclopentanedione (4.38%), whereas CuO markedly suppressed cyclic ketones (to 9.16%). CuO increased acetic acid from 11.56% to 16.65% and raised total furans selectivity to 17.48%; Fe2O3 and CeO2 also increased acids, whereas CaO reduced acids to 3.88%. The decrease in LG yield—to 4.83%, 7.04%, and 7.18% over CuO, TiO2-1, and TiO2-2, respectively—was consistent with an acceleration of secondary conversion pathways of anhydrosugars. In the future, the following research directions were recommended: (i) long-duration, continuous ex situ runs to quantify product yields and catalyst stability/regeneration in a pilot-scale CFP unit; (ii) development of Ca-based catalysts to maximize ketones while suppressing acids; (iii) exploration of catalytic reaction mechanisms through theoretical simulations; and (iv) economic evaluation of the entire CFP system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; methodology, J.C.; software, Y.L.; validation, L.Y. and F.L.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, J.C.; resources, F.G.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, J.C.; visualization, F.G.; supervision, F.G.; project administration, F.G.; funding acquisition, Y.L. and F.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant number 2023M733750), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant number 2024QN11084).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CFP | Catalytic fast pyrolysis |

| TiO2-1 | Rutile TiO2 |

| TiO2-2 | Anatase TiO2 |

| LG | Levoglucosan |

| HAA | Hydroxyacetaldehyde |

| HMF | 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural |

References

- Omari, A.; Heuser, B.; Pischinger, S.; Rüdinger, C. Potential of long-chain oxymethylene ether and oxymethylene ether-diesel blends for ultra-low emission engines. Appl. Energy 2019, 239, 1242–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Awadh, M.; Goh, K.O.M. Machine learning and experimental emission assessment in high temperature air premixed charged compression ignition engines using the Pugh matrix. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, R. Preparation of carbonyl precursors for long-chain oxygenated fuels from cellulose ethanolysis catalyzed by metal oxides. Fuel Process. Technol. 2020, 206, 106468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Bao, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, R. The regulated emissions and PAH emissions of bio-based long-chain ethers in a diesel engine. Fuel Process. Technol. 2021, 214, 106724. [Google Scholar]

- Farouk, S.M.; Tayeb, A.M.; Abdel-Hamid, S.M.; Osman, R.M.; Mustafa, H.M. Enhanced performance and reduced emissions in compression-ignition engine fueled with biodiesel blends synthesized via CaO and MgO nano catalysts. BMC Chem. 2025, 19, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulis, D.B.; Lavoine, N.; Sederoff, H.; Jiang, X.; Marques, B.M.; Lan, K.; Cofre-Vega, C.; Barrangou, R.; Wang, J.P. Advances in lignocellulosic feedstocks for bioenergy and bioproducts. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, K.; Tao, Y.; Yang, Q.; Xu, L.; Liu, C.; Ma, L.; Xiao, R. Biomass directional pyrolysis based on element economy to produce high-quality fuels, chemicals, carbon materials–A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 69, 108262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, J.; Shao, S.; Hu, X.; Cai, Y. Aldol condensation/hydrogenation for jet fuel from biomass-derived ketone platform compound in one pot. Fuel Process. Technol. 2021, 215, 106768. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, Q.; Wang, H. Tandem Reactions for the Synthesis of High-Density Polycyclic Biofuels with a Double/Triple Hexane Ring. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 19158–19165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, F.; Yang, L.; Guo, F.; Wu, S.; Xiao, R. Directional synthesis and application of long-chain ethers from biomass-derived carbonyls. Fuel 2024, 372, 132266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Sarker, M.; Rahman, M.M.; Li, C.; Chai, M.; Cotillon, R.; Scott, N.R. Multi-scale complexities of solid acid catalysts in the catalytic fast pyrolysis of biomass for bio-oil production–a review. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2020, 80, 100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasalos, I.; Lappas, A.; Kopalidou, E.; Kalogiannis, K. Biomass catalytic pyrolysis: Process design and economic analysis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2016, 5, 370–383. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Kong, L.; You, X.; Wu, S.; Yang, C.; Xiong, M.; Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Gao, C. Coproduction of High-Value Oils and Carbon Nanotubes via Polystyrene Pyrolysis with Biomass-Derived Iron Catalysts. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 13628–13641. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, S.; Cao, Y.; Ye, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, R. Enhanced selective production of aldehydes and ketones by catalytic upgrading of pyrolysis vapor from holocellulose over red mud-based composite catalysts. Fuel 2024, 355, 129367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Liu, H.; Dong, J.; Song, J.; Deng, S.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hong, W. Enhancing ketones and syngas production by CO2-assisted catalytic pyrolysis of cellulose with the Ce–Co–Na ternary catalyst. Energy 2022, 250, 123799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Hu, W.; Jaegers, N.R.; Gao, F.; Hu, J.Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y. Elucidation of the roles of water on the reactivity of surface intermediates in carboxylic acid ketonization on TiO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 145, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Church, A.L.; Cordon, M.J.; Li, C.; Hunt, R.D.; Choi, J.-S.; Bai, L.; Li, Z.; Parks, J.E.; Hu, M.Z. Mechanistic insights and rational design of Ca-doped CeO2 catalyst for acetic acid ketonization. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 11068–11077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mante, O.D.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Senanayake, S.D.; Babu, S.P. Catalytic conversion of biomass pyrolysis vapors into hydrocarbon fuel precursors. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 2362–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Papadikis, K.; Konysheva, E.Y.; Lin, Y.; Kozhevnikov, I.V.; Li, J. CaO catalyst for multi-route conversion of oakwood biomass to value-added chemicals and fuel precursors in fast pyrolysis. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 285, 119858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Liu, C.; Xiang, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, R.; Cai, Y. In situ catalytic fast pyrolysis over CeO2 catalyst: Impact of biomass source, pyrolysis temperature and metal ion. Renew. Energy 2021, 177, 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Ye, Z.; Liu, C.; Hu, X.; Sun, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, R. Catalytic pyrolysis of holocellulose followed by integrated aldol condensation and hydrogenation to produce aviation fuel. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 264, 115644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Ding, K.; Lin, G.; Sun, H.; Zhang, S. Enhancing the ketonization ability of CeO2 for deoxygenation of biomass-derived sugars by Fe doping. Fuel 2024, 361, 130689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Bhagia, S.; Smith, M.D.; Petridis, L.; Ong, R.G.; Cai, C.M.; Mittal, A.; Himmel, M.H.; Balan, V.; Dale, B.E. Cellulose–hemicellulose interactions at elevated temperatures increase cellulose recalcitrance to biological conversion. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, V.H.; Hoang, H.Y.; Nguyen, A.T.; Doan, V.-D.; Tran, V.A. Synthesis and adsorption behavior of Zn2SiO4 nanoparticles incorporated with biomass-derived activated carbon as a novel adsorbent in a circular economy framework. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 193, 107554. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X.-F. Catalytic upgrading of biomass fast pyrolysis vapors with Pd/SBA-15 catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 2573–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranzi, E.; Frassoldati, A.; Grana, R.; Cuoci, A.; Faravelli, T.; Kelley, A.P.; Law, C.K. Hierarchical and comparative kinetic modeling of laminar flame speeds of hydrocarbon and oxygenated fuels. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2012, 38, 468–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hu, X.; Guo, H.; Wei, T.; Dong, D.; Hu, G.; Hu, S.; Xiang, J.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y. Pyrolysis of poplar, cellulose and lignin: Effects of acidity and alkalinity of the metal oxide catalysts. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2018, 134, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Shen, Y.; Xia, M.; Tu, L.; Luo, J.; Geng, Y.; Gao, T.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, M. A highly efficient step-wise biotransformation strategy for direct conversion of phytosterol to boldenone. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 283, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, G.; Rutter, A.; Pollard, A.; Davis, J.; Matovic, D. The effects of weathering on the pyrolysis of low-carbon fuels: Railway ties and asphalt shingles. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 138, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, H. Solid base catalysts: Generation of basic sites and application to organic synthesis. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2001, 222, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montini, T.; Melchionna, M.; Monai, M.; Fornasiero, P. Fundamentals and catalytic applications of CeO2-based materials. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 5987–6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busca, G. Acid catalysts in industrial hydrocarbon chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5366–5410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patwardhan, P.R.; Satrio, J.A.; Brown, R.C.; Shanks, B.H. Influence of inorganic salts on the primary pyrolysis products of cellulose. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 4646–4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitthisa, S.; Sooknoi, T.; Ma, Y.; Balbuena, P.B.; Resasco, D.E. Kinetics and mechanism of hydrogenation of furfural on Cu/SiO2 catalysts. J. Catal. 2011, 277, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Zhang, B.; Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Chen, X.; Fei, B. Synergistic effects of tung oil and heat treatment on physicochemical properties of bamboo materials. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Xu, H.; Yin, X.; Wang, S. H2SO4 assisted hydrothermal conversion of biomass with solid acid catalysis to produce aviation fuel precursors. Iscience 2023, 26, 108249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettler, M.S.; Mushrif, S.H.; Paulsen, A.D.; Javadekar, A.D.; Vlachos, D.G.; Dauenhauer, P.J. Revealing pyrolysis chemistry for biofuels production: Conversion of cellulose to furans and small oxygenates. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 5414–5424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, Z.; Najafi Chermahini, A.; Dinari, M. Glycerol adsorption and mechanism of dehydration to acrolein over TiO2 surface: A density functional theory study. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 563, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Ge, Q.; Zhu, X. Research progress in ketonization of biomass-derived carboxylic acids over metal oxides. Acta Chim. Sin. 2017, 75, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Iglesia, E. Experimental and theoretical evidence for the reactivity of bound intermediates in ketonization of carboxylic acids and consequences of acid–base properties of oxide catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 18030–18046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotoso, T.; Herrera, L.V.; Vann, T.; Briggs, N.M.; Gomez, L.A.; Barrett, L.; Jones, D.; Pham, T.; Wang, B.; Crossley, S.P. Stabilization of furanics to cyclic ketone building blocks in the vapor phase. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 254, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, R. Fast pyrolysis of holocellulose for the preparation of long-chain ether fuel precursors: Effect of holocellulose types. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 338, 125519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, R. Fast pyrolysis of torrefied holocellulose for producing long-chain ether precursors in a fluidized bed. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 341, 125770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayes, H.B.; Broadbelt, L.J. Unraveling the reactions that unravel cellulose. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 7098–7106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbecq, F.; Wang, Y.; Muralidhara, A.; El Ouardi, K.; Marlair, G.; Len, C. Hydrolysis of hemicellulose and derivatives—A review of recent advances in the production of furfural. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hronec, M.; Fulajtárova, K.; Soták, T. Highly selective rearrangement of furfuryl alcohol to cyclopentanone. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 154, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagaki, A. Rational design of metal oxide solid acids for sugar conversion. Catalysts 2019, 9, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).