1. Introduction

Electricity tariffs serve as the cornerstone of a functional and sustainable electricity system. They are essential not only for enabling utilities to recover the capital and operating costs associated with power generation, transmission, and distribution, but also for ensuring affordability for end-users and offering a fair rate of return to investors. Tariff structures play a critical role in shaping consumer behavior, influencing load profiles, and guiding investment in infrastructure and demand-side technologies [

1].

Traditional electricity pricing has relied heavily on flat-rate tariffs, which charge customers a single rate per kilowatt-hour regardless of the time of use. While simple to understand and administer, flat rates do not reflect the real-time cost variations associated with electricity generation and grid operations [

2]. To address this, many jurisdictions have introduced time-differentiated tariffs that encourage customers to shift their electricity usage away from high-demand periods.

Time-varying pricing mechanisms, such as Time-of-Use (TOU), Real-Time Pricing (RTP), and event-based tariffs, have gained interest in response to the growing complexity of electricity systems and the integration of variable renewable energy sources [

3]. These pricing models provide financial incentives for consumers to modify their electricity consumption in alignment with grid needs. One type of event-based tariff, Critical Peak Pricing (CPP), represents an advanced form of dynamic pricing where extremely high rates are applied during a limited number of critical peak periods during each year’s heating season. CPP aims to reduce demand during moments of extreme grid stress, typically driven by weather-related spikes in residential or commercial usage.

In addition to encouraging load shifting, time-sensitive pricing structures have proven effective in deferring investments in costly infrastructure upgrades by flattening demand curves [

4]. For example, reducing peak demand during high-stress periods through dynamic pricing can avoid or delay the need for new generation or transmission capacity. This not only improves operational efficiency but also supports long-term decarbonization goals.

However, the transition to dynamic pricing poses several challenges, particularly related to consumer awareness, behavioral inertia, and the upfront costs of enabling technologies [

5]. These barriers may limit the effectiveness of such tariffs among vulnerable populations, raising concerns around affordability and fairness. Designing dynamic pricing programs that are inclusive and supported by targeted education and financial incentives will be critical to ensuring a just energy transition.

As electrification expands into sectors such as transportation and heating, electricity providers are under increased pressure to deploy more sophisticated tariff models that balance grid reliability, affordability, and equity. This paper contributes to demand-side management by analyzing how time-of-use and event-based tariffs can impact the choice of electricity tariff for residential customers in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia when compared with the existing domestic service tariff [

6]. Specifically, it investigates the equilibrium point at which the annual cost under the time-of-use and event-based tariffs structures equals the domestic service tariff for customers with identical total electricity consumption. Using algebraic equilibrium analyses and examples of consumption loads, the paper identifies the point where the energy consumption and cost of the two time-varying tariffs equals the flat rate. By quantifying this threshold, the study aims to inform both policymakers and electricity providers on how to structure tariffs that balance affordability, efficiency, and fairness. For energy consumers, the analysis provides a practical framework to evaluate whether switching to a time-varying tariff will reduce their electricity costs based on their seasonal consumption patterns. The paper offers data-driven insights to help consumers make informed tariff choices and optimize their energy use as compared to the findings in a tariff-evaluation report from Nova Scotia’s principal electricity supplier.

2. Background

Understanding the efficacy of time-varying tariff models necessitates a comparative evaluation of tariff structures implemented across diverse regulatory contexts. Around the world, electricity providers have implemented a spectrum of tariff designs aimed at balancing operational reliability, economic efficiency, and equity in power distribution. These tariff structures are not only financial instruments for revenue recovery and cost allocation but also behavioral tools to influence when and how electricity is consumed. As the energy transition accelerates and grids accommodate increasing shares of variable renewables such as wind and solar, pricing mechanisms become essential for achieving grid flexibility and cost-effectiveness.

The most prominent and widely adopted tariff models include flat-rate pricing, TOU pricing, and event-based. Flat-rate tariffs are characterized by simplicity and uniformity, making them highly accessible for mass-market customers, while TOU rates reward users who shift consumption to off-peak periods. Meanwhile, event-based tariffs offer a dynamic and responsive structure that targets specific moments of grid stress by levying very high prices during pre-designated critical hours. Each tariff type reflects distinct regulatory control and system conditions, from customer protection to real-time market integration.

To contextualize the analysis,

Section 2.1,

Section 2.2 and

Section 2.3 describe the three major tariff structures relevant to this study: flat-rate, time-of-use, and event-based tariffs. Each subsection outlines the principles, rate mechanisms, and international examples that inform the comparative analysis conducted in

Section 3 and discussed in

Section 4.

2.1. Flat-Rate Tariffs

Flat-rate tariffs apply a consistent per-kilowatt-hour charge irrespective of time-of-day or seasonal grid conditions. They are the most straightforward pricing model and remain prevalent in markets where smart meter penetration is limited or where administrative ease is prioritized over cost-reflective efficiency. Flat-rate pricing is often used as a default or legacy option for customers who opt out of more complex plans. However, they fail to signal the cost of peak demand or renewable intermittency, potentially increasing the need for costly infrastructure investments. Examples of flat-rate tariffs include:

Singapore (Standard Tariff): As of 2024, SP Group (Singapore) charges a uniform rate of approximately SGD 0.299/kWh for residential users [

7]. This tariff is applied consistently across all hours, days, and seasons, without distinction between peak and off-peak periods.

Ireland (Standard Rate): Before widespread deployment of smart meters, Electric Ireland (Belfast, NI, UK) charged most households a static rate of roughly €0.32/kWh [

8]. The simplicity of this rate remains attractive to certain demographics, though it provides no incentive for behavioral change in electricity usage.

2.2. Time-of-Use (TOU) Tariffs

TOU pricing introduces temporal granularity to electricity rates by segmenting the day into multiple pricing bands typically off-peak and on-peak based on historical consumption patterns and grid load. This model helps shift load away from congested periods, thereby flattening demand curves and reducing reliance on expensive peaking generation. TOU tariffs are enabled by smart meters and require well-informed consumers to adjust their routines accordingly, examples include:

2.3. Event-Based Tariffs

Event-based tariffs represent a more targeted approach to load management. Rather than fixed price bands, event-based tariffs impose steep price hikes during a limited number of designated “critical events” typically periods of high demand or system stress. These tariffs are often paired with advanced notification systems (e.g., day-ahead alerts) and are especially designed to effectively curtail the demand during the most expensive hours of the year [

12], examples include:

In France, the EDF Tempo tariff rates for July 2025, valid until 31 July, vary by day type and season. Blue days (300 days, year-round, including Sundays) cost 0.1552 €/kWh during peak hours (06:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m.) and 0.1288 €/kWh during off-peak hours (10:00 p.m. to 06:00 a.m.). White days (43 days, mostly fall/spring) are 0.1792 €/kWh (peak) and 0.1447 €/kWh (off-peak). Red days (22 days, 1 November to 31 March, winter only) are 0.6586 €/kWh (peak) and 0.1518 €/kWh (off-peak) [

13].

In Nova Scotia, the Critical Peak Pricing (CPP) pilot program was effective by Nova Scotia Power on 1 November 2024 and is scheduled to run until 31 October 2025. The pilot aims to test how dynamic pricing can reduce peak demand during winter months [

14]. Participants are notified by 4:00 p.m. the day before via email or SMS, allowing them time to shift or reduce usage. The CPP structure, with its sharp price differential and targeted event scheduling, is designed to curtail electricity use during the most expensive and high-stress hours on the grid.

2.4. Comparison and Key Differences

Flat-Rate tariffs emphasize administrative ease and customer simplicity but fall short in managing peak demand or supporting renewable integration. TOU tariffs use temporal signals to shift demand across predictable intervals, providing economic and operational benefits with moderate complexity [

15]. Event-based tariffs offer sharp and responsive price signals during extreme conditions, making them suitable for reducing demand during the most critical periods [

16].

The choice of tariff model involves complex trade-offs between transparency, cost reflectiveness, consumer comprehension, and system flexibility. As smart grid technologies mature, the success of dynamic pricing increasingly hinges on consumer awareness, real-time communication systems, and supportive policy frameworks, including targeted subsidies and automation incentives.

3. Methodology and Analysis

Nova Scotia Power is a vertically integrated electricity utility serving approximately 520,000 customers, or about 95% of residents and businesses in Nova Scotia [

17]. As a privately owned subsidiary of Emera Inc., Nova Scotia Power is regulated by the Nova Scotia Utility and Review Board (NSUARB) and is responsible for the province’s generation, transmission, and distribution of electricity. By law, Nova Scotia Power must develop and implement tariffs, including open-access transmission tariffs, distribution tariffs, and spill or interconnection tariffs as mandated under the Electricity Act (2004), while ensuring that costs are borne by retail suppliers and their customers rather than Nova Scotia Power’s general customer base [

18].

This study adopts a two-stage approach to compare the financial implications of Nova Scotia Power’s dynamic electricity pricing models, time-of-use (TOU) and critical-peak pricing (CPP), with Nova Scotia Power’s domestic service tariff Standard Residential Service (SRS) tariff. The primary objective is to determine the equilibrium point at which a residential customer’s annual electricity cost under a dynamic tariff becomes equal to that under the flat-rate SRS tariff. By identifying these thresholds, the analysis aims to guide residential customers in selecting the most cost-effective tariff option based on actual consumption patterns.

In

Section 3.1, the SRS tariff is compared with the TOU tariff. The TOU tariff is divided into three pricing periods: non-winter, winter off-peak, and winter peak hours. A series of equations are derived to determine how a customer’s annual electricity consumption must be distributed across these time blocks to match the cost of the SRS tariff. The analysis reveals a critical consumption ratio between non-winter and winter peak periods that must be met for the TOU and SRS tariffs to be cost-equivalent. This mathematical relationship enables the identification of the specific conditions under which TOU becomes a more economical option than SRS.

Section 3.2 applies a similar approach to the SRS-TOU comparison to evaluate the CPP tariff against the SRS tariff. The CPP model introduces increased electricity rates during a limited number of “critical peak” events, typically triggered by projected periods of system stress or high demand. This part of the analysis focuses on determining the number of critical peak events and the percentage of electricity consumption during those periods that would result in total annual costs equaling those under the flat SRS rate. By modeling different usage scenarios and varying the share of consumption during peak events, the analysis identifies a threshold at which CPP becomes cost-effective or, conversely, burdensome, to the customer.

Both parts of the methodology involve modeling Nova Scotia Power’s tariff structures and applying them to a range of different consumption profiles. These sections include detailed calculations, illustrative tables, and a discussion of the practical implications of each tariff option.

3.1. Comparing SRS with TOU

In this section, we are interested in determining the point at which a customer’s SRS cost is equal to the TOU cost. The equilibrium point is defined as the point at which the number of kilowatt-hours and the total cost of the two tariffs are equal.

The TOU service has three rates: one for April to October (non-winter) and two for November to March (winter); the winter off-peak rate of

$0.1856 is equal to the SRS rate. The SRS rate and TOU rates are shown in

Table 1.

This puts several restrictions on finding the equilibrium point:

Since the winter off-peak rate equals the SRS rate, the equilibrium point can be met if all TOU kilowatt-hours are consumed during the winter off-peak hours. This is not possible if the TOU consumer uses electricity during the non-winter and winter peak hours.

The non-winter rate and the winter peak rate are unable to meet the equilibrium requirements without being combined with another rate, as the following charts show.

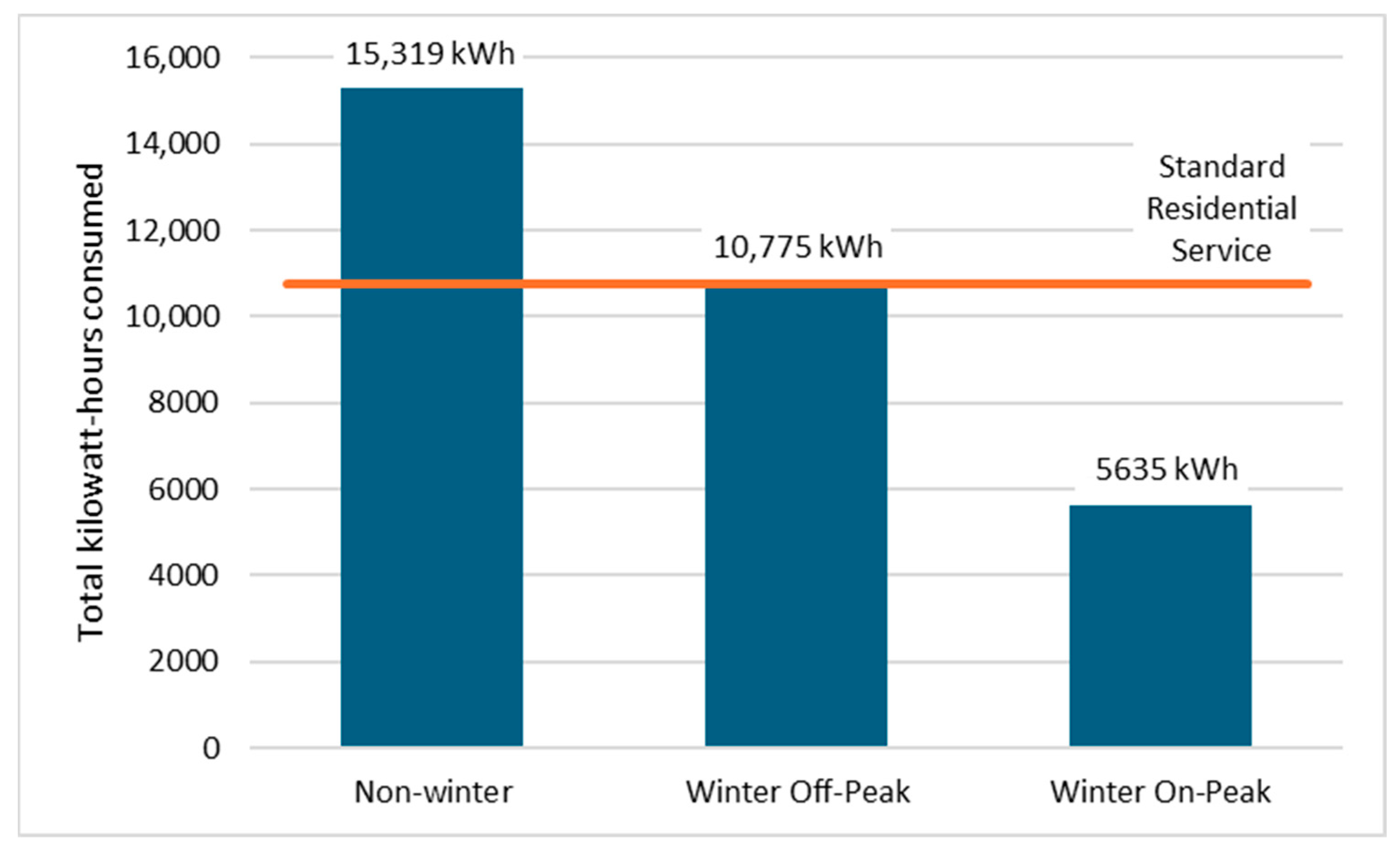

In

Figure 1, we see the volume of kilowatt-hours consumed by a consumer paying

$2000 for each of the TOU’s three rates. The Standard Residential Service and the Winter Off-Peak totals are the same at 10,775 kWh; the winter peak rate has the highest cost per kilowatt-hour rate and limits the volume purchased to 5635 kWh, while the lowest-cost-per-kilowatt-hour is the non-winter rate lets the customer purchase 15,319 kWh.

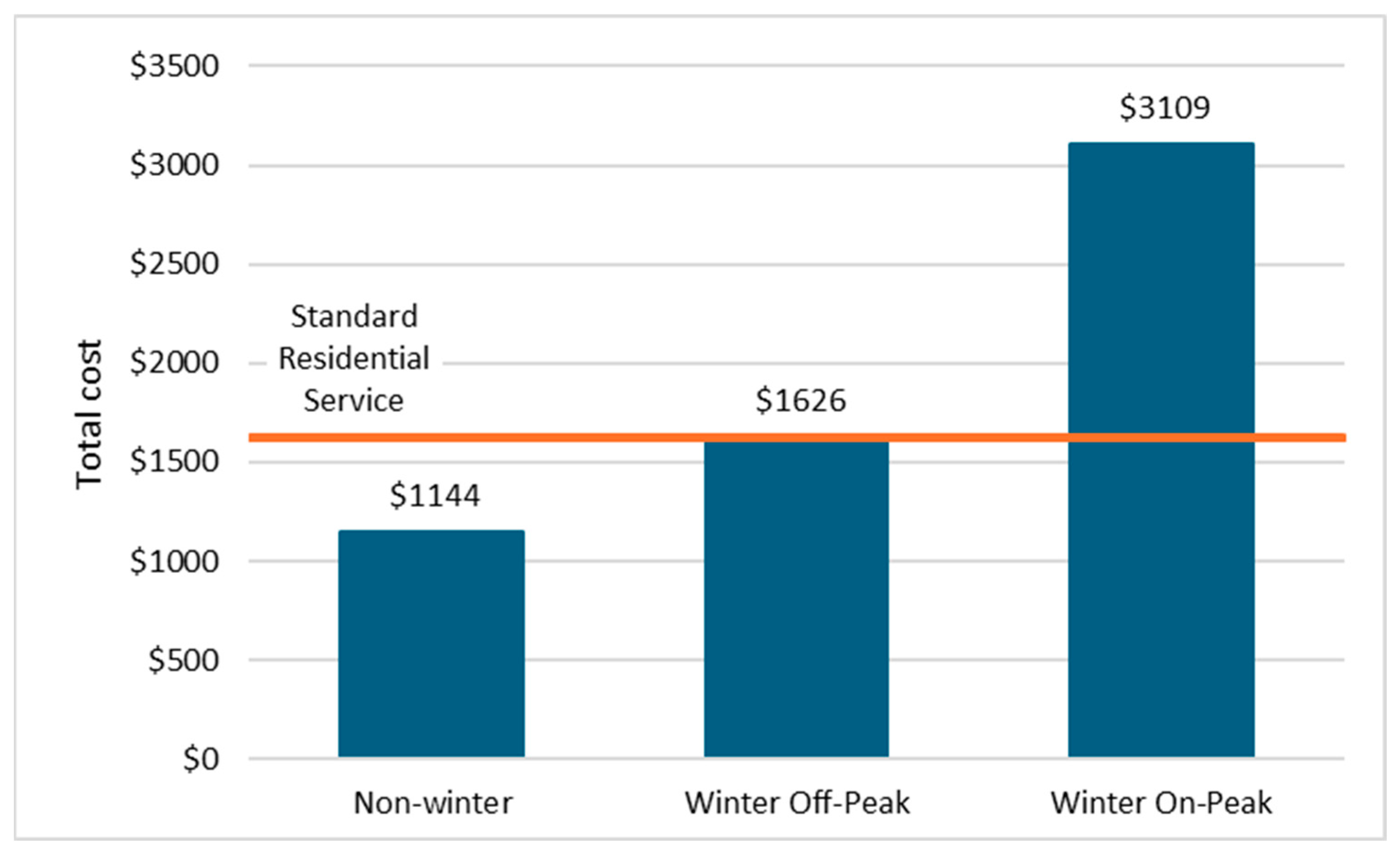

The cost of purchasing 8760 kWh during one of the three pricing periods is shown in

Figure 2. The lowest total cost is

$1144 with the non-winter rate and the highest is

$3109 for the winter peak rate. As before, since the per-kilowatt-hour rates are equal for the Standard Residential Service and winter off-peak, the costs are the same at

$1626.

Unless a customer only uses electricity during the winter off-peak hours, all three TOU rates must be considered when determining the SRS-TOU.

3.1.1. Method

The equilibrium SRS-TOU point occurs when the SRS energy cost equals the TOU energy cost and the total energy consumed in kilowatt-hours is equal. The SRS cost is the produce of the volume of electricity used (SRS.kWh) and the rate (SRS.Rate), while the TOU cost consists of three electricity volumes (NW.kWh, WOP.kWh, and WP.kWh) and the corresponding rates (NW.Rate, WOP.Rate, and WP.Rate). The equilibrium point can be expressed in terms of energy and cost:

The cost equilibrium point is:

The energy equilibrium point is:

or

The total kilowatt-hours available for the non-winter and winter peak consumption is (this is equivalent to SRS.kWh − WOP.kWh):

The cost of the reduction in the winter off-peak kilowatt-hours (WOP.kWh) must equal the cost of the non-winter (NW.kWh) and winter peak (WP.kWh) consumption:

Replacing WP.kWh with Total.kWh − NW.kWh (from Equation (4)) gives:

or

Rearranging Equation (7) gives:

By replacing Cost with Total.kWh × SRS.Rate, (from Equation (5)), we find:

Applying the respective rates to Equation (10) gives:

The ratio of the difference between the winter non-peak and peak rates and the difference between the non-winter and winter-peak rates is a constant, 0.7546, and can be applied to any total consumption to find the SRS-TOU equilibrium point.

The winter-peak consumption, WP.kWh, is therefore 1 − 0.7546 or 0.2453. This means there must be 3.0756 non-winter kilowatt-hours consumed for every one kilowatt-hour of winter-peak consumption (the ratio of the non-winter consumption and the winter-peak consumption) to achieve the equilibrium point. When the non-winter-to-winter-peak ratio exceeds 3.0756, an SRS customer would pay less for their electricity charges if they subscribed to the TOU tariff and should consider switching from the SRS tariff to the TOU tariff.

3.1.2. Application

By applying Equation (12), we can determine the cost and volume of energy used for the non-winter and winter-peak TOU periods are to be in equilibrium with the same cost and volume of an SRS customer; examples of this are shown

Table 2.

The total number of kilowatt-hours to be divided between the non-winter and winter peak periods range from 1 kWh to 21,900 kWh. For example, if 4380 kWh were available, the customer would need to use 3305.3 and 1074.7 during the non-winter and winter-peak periods, respectively. The cost of the non-winter and winter-peaks is $812.97, which is equal to the SRS cost for an equivalent amount of electricity.

In all examples considered, there is a constant non-winter-to-winter-peak ratio of 3.076 for the equilibrium to be reached. That is, for every kilowatt-hour of winter-peak use, 3.076 kilowatt-hours of non-winter electricity must be consumed.

The above examples only consider the total volume of electricity a customer consumes during the non-winter and winter-peak hours. It is not necessary to account for the winter non-peak hours because the cost of electricity during the winter non-peak equals the SRS cost.

The TOU equilibrium ratio of 3.0756 is derived from fixed-tariff rates and deterministic load allocations. To assess its robustness, sensitivity checks were conducted by varying TOU rates and consumption ratios within ±5%. The resulting threshold varied only between 2.96 and 3.19, indicating limited sensitivity to minor deviations in load profiles or measurement errors. However, significant changes in seasonal usage patterns or rate design could alter this ratio, suggesting that the model’s applicability depends on stable rate structures.

3.2. Comparing SRS with CPP

The equilibrium point for the CPP rate and the SRS rate is the point at which the number of kilowatt-hours and the total cost of the service are equal for both rates.

The CPP has two rates, one for all non-event hours during the year and a second for up to 18 four-hour events that can occur between 1 November and 31 March of the following year. The SRS and CPP rates are summarized in

Table 3.

3.2.1. Method

The SRS-CPP equilibrium point occurs when the cost of using the SRS rate equals the cost of the CPP rates, both with and without events throughout the year (1 April to 31 March). Up to 18 four-hours critical peak events can occur between 1 November and 31 March. The equilibrium point is expressed algebraically as follows (.NEv refers to all non-events and .Ev to all events between 1 November and 31 March):

The total CPP kilowatt-hours consumed (both during non-events and events) are constrained by:

Replacing CPP.Ev.kWh on the righthand side of Equation (13) with Equation (14), SRS.kWh − CPP.NEv.kWh, gives:

Equation (15) can be rewritten as:

or:

Incorporating Equation (18) into Equation (13) we find:

Rearranging Equation (19) allows us to determine the number of non-event kilowatt-hours possible:

Equation (20) can be simplified to:

Applying the rates in

Table 3 to Equation (21) gives the number of CPP non-event kilowatt-hours:

The ratio of the differences in the SRS and CPP event rates and the differences in the CPP non-event and event-rates is 0.98253, reducing Equation (22) to simply:

The SRS-CPP equilibrium point is reached when the CPP non-event load is 98.253% of the SRS load. This limits the customer’s load to 1.747% of the SRS load during all events, regardless of the number of events. If the customer can use less than 1.747% of the SRS load, the CPP tariff will cost less than the SRS tariff; however, exceeding the 1.747% limit will mean the SRS tariff is less expensive.

3.2.2. Application

The SRS-CPP equilibrium point can be obtained from the number of CPP non-event kilowatt-hours (from Equation (23)) and the number of SRS kilowatt-hours, allowing us to determine the number of CPP event kilowatt-hours using Equation (14). Examples of this are shown in

Table 4.

For example, if a consumer used 13,140 kilowatt-hours in a year (Row 1), the number of non-event and event kilowatt-hours are limited to 12,910.48 (Row 2) and 229.52 (Row 3), respectively, at the equilibrium point. The total number of CPP kilowatt-hours is 13,140 (Row 4, the sum of Rows 2 and 3).

The cost breakdown is shown in rows 5 through 8 of

Table 4, with an SRS cost of

$2438.915 for the 13,140 kilowatt-hours customer (Row 5). The final three rows are the CPP non-event cost (

$2046.569; Row 6), the CPP event cost (

$392.347; Row 7), and the total CPP cost (

$2438.915; Row 8). The total CPP and SRS kilowatt-hours are equal, as are the total costs, indicating that the equilibrium point has been reached.

The available number of CPP-event kilowatt hours is independent of the number of events; as the number of events increases, the cost per event decreases. However, the total cost remains the same.

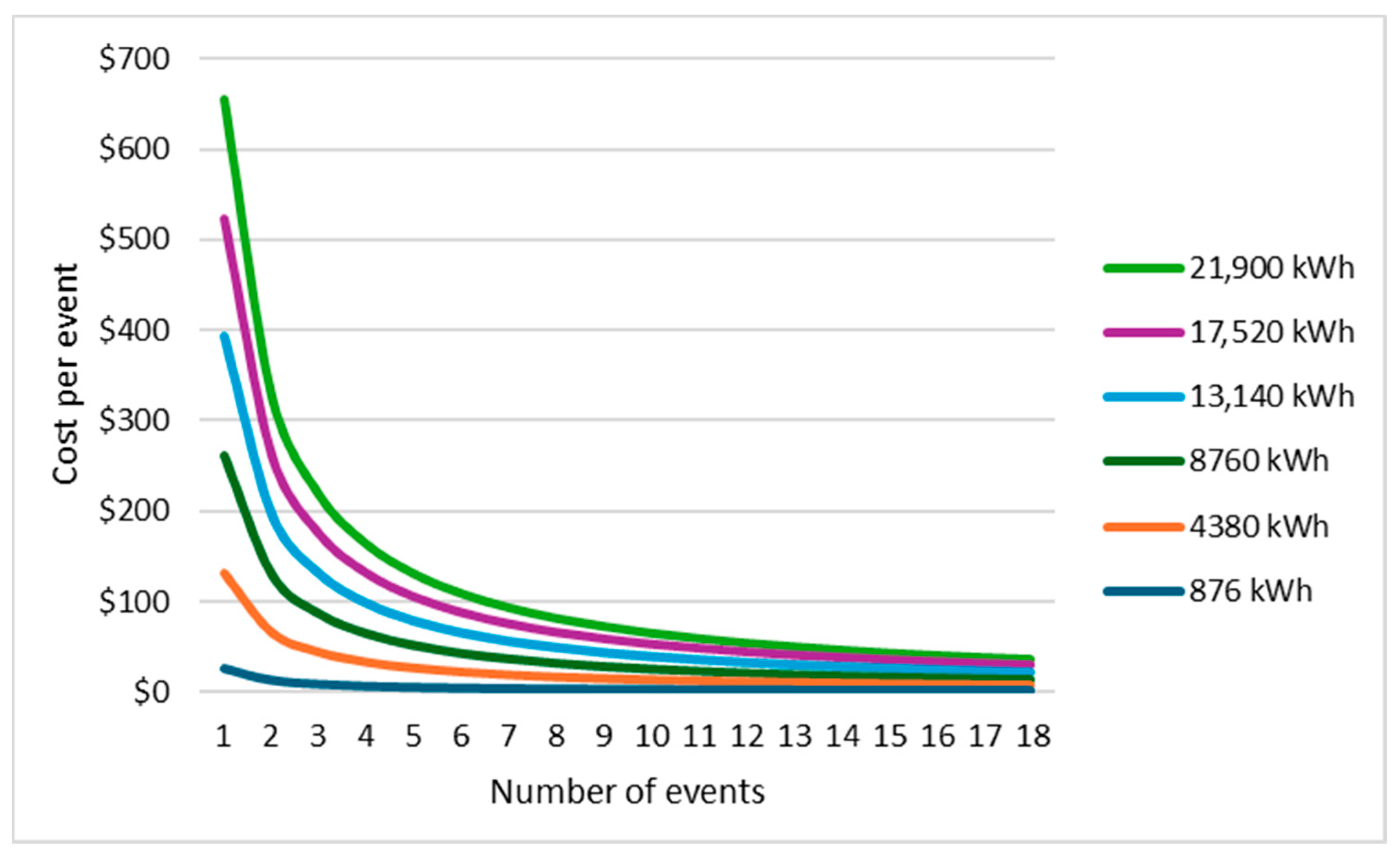

For example, to meet the SRS-CPP equilibrium point, a household consuming 13,140 kilowatt-hours would need to use 229.52 kilowatt-hours, this is regardless of the number of events; this effect is illustrated in

Figure 3 for several SRS consumption values (from

Table 4). If there was one event, the equilibrium would be met if the customer used 229.52 kilowatt-hours during the event for a cost of

$392.347 (from

Table 4), and during that event, the customer would need to consume more than 22.952 kilowatt-hours during the event for a cost of

$392.347.

The equilibrium cost per event for any annual consumption can be expressed as follows:

For example, if five CPP events occur for a customer consuming 13,140 kilowatt hours, the cost for all events is $392.347−5 or $78.47 per event.

4. Discussion

4.1. Time-of-Use (TOU) Tariff

The equilibrium point for the Time-of-Use rate and SRS rate shows that to switch from SRS to TOU, the SRS customer’s non-winter load must be at least 3.07 times greater than their winter-peak load. However, for most SRS customers, the opposite is usually true, with the winter-peak load being greater than the non-winter load because of less daylight hours and colder days requiring the use of electric heating.

The TOU rate structure favors those customers with a summer peak load, such as a customer driving an electric vehicle or with a heavy air conditioner load, or both. If the customer was to charge their vehicle during the non-peak hours during the winter months (November to March), the TOU rate would equal the SRS rate. In this scenario, the TOU customer would always pay less than the SRS customer.

The structural equivalence between the winter off-peak and SRS rates simplifies the Nova Scotia TOU tariff by limiting the equilibrium equation to one variable, the winter peak rate. While this simplifies the Nova Scotia TOU tariff, it limits the external application of the method in regions where off-peak rates diverge from flat-rate benchmarks. In markets with distinct off-peak differentials, the equilibrium ratio would shift, requiring recalibration using local tariff parameters.

4.1.1. Application of TOU

An SRS customer contemplating a switch to TOU must determine their total annual non-winter consumption (SRS.NW.kWh) and their winter peak consumption (SRS.WP.kWh). These values can be obtained directly from hourly or interval data, such as those provided by a smart meter from their provider. The non-winter to winter-peak ratio is calculated as:

If this ratio exceeds the threshold value of 3.0756, the TOU tariff becomes the more economical option. This threshold is derived from the linear cost-equivalence model presented in

Section 3.1.1 and represents the point at which the annual cost of electricity under TOU equals that under the SRS rate for identical total consumption.

The ratio method avoids the need for intermediate calculations when both non-winter and winter-peak consumption figures are available. However, the result remains sensitive to marginal changes in consumption distribution across TOU periods. Customers with dynamic or seasonal load profiles, particularly those with elevated summer usage from EV charging, may find that even small shifts in usage can influence whether TOU is advantageous.

4.1.2. Improving the Non-Winter to Winter-Peak Ratio

Changing from the SRS rate to the TOU rate requires the non-winter-to-winter-peak ratio to exceed 3.075, which can be achieved by increasing the non-winter consumption and decreasing the winter-peak consumption. This can be achieved in any of three ways, assuming the SRS load remains constant: First, shifting all or part of the winter peak load to the winter off-peak; second, shifting all or part of the winter off-peak load to the non-winter; and finally, shifting all or part of the winter peak to the non-winter.

Some of these changes are easier said than done. For example, shifting from the winter peak to the non-winter might not be possible if there are season-specific loads, such as heating and lighting during the winter months. Similarly, the TOU rate might not be appropriate for customers with a high winter-peak load and a low non-winter load since it might not be possible to achieve the non-winter-to-winter-peak ratio.

If an SRS customer reduces their winter peak load, for example, by replacing a baseboard heating system with a heat pump, this might improve the non-winter-to-winter-peak ratio. This could also be achieved by increasing the non-winter load, for example, by purchasing an electric vehicle.

4.2. Critical Peak Pricing (CPP) Tariff

The CPP structure introduces a degree of uncertainty into household electricity consumption planning. Electrically intensive activities, such as preparing large meals or operating baseboard (resistance) heating during cold evenings may coincide with critical peak events. This unpredictability can be inconvenient for consumers, particularly given that event notifications are issued at 4:00 p.m. on the day prior, and up to two events may be scheduled within a single day. Such limited advance notice can restrict the ability of households to adjust their usage patterns effectively, especially in situations where flexibility is constrained by comfort or routine.

4.2.1. Choosing the CPP

At the start of the heating season (November to the following March), CPP customers have no indication of the number of events that can happen or when they will occur. However, Equation (24) allows us to determine the number of event kilowatt-hours permitted for an annual number of SRS kilowatt-hours. This requires the customer to have a record of past annual kilowatt-hours consumed.

Table 5 can be used as a guide for a customer to decide whether to use the CPP. For example, if the customer’s non-event consumption is below the non-event limit, but the customer’s consumption during events is above the event limit, it is necessary to check equation to decide which rate to use. If the customer exceeds both the non-event and event limits, the SRS will be less expensive.

Notwithstanding the above, customers are not given the option to unilaterally select SRS or CPP once the heating season has started, they must decide long before the start of the heating season.

The CPP equilibrium assumes a regulatory cap of 18 annual events, each lasting four hours. If the number of events increases or their duration is extended, the share of event-period consumption rises, proportionally increasing total costs and reducing cost neutrality. For example, a doubling of event duration (from four to eight hours) would approximately double event exposure, shifting the equilibrium from 1.75% to around 3.5% of total consumption. Thus, tariff performance remains sensitive to event frequency and duration, underscoring specificity of the method to the rate structure.

4.2.2. Load Shifting

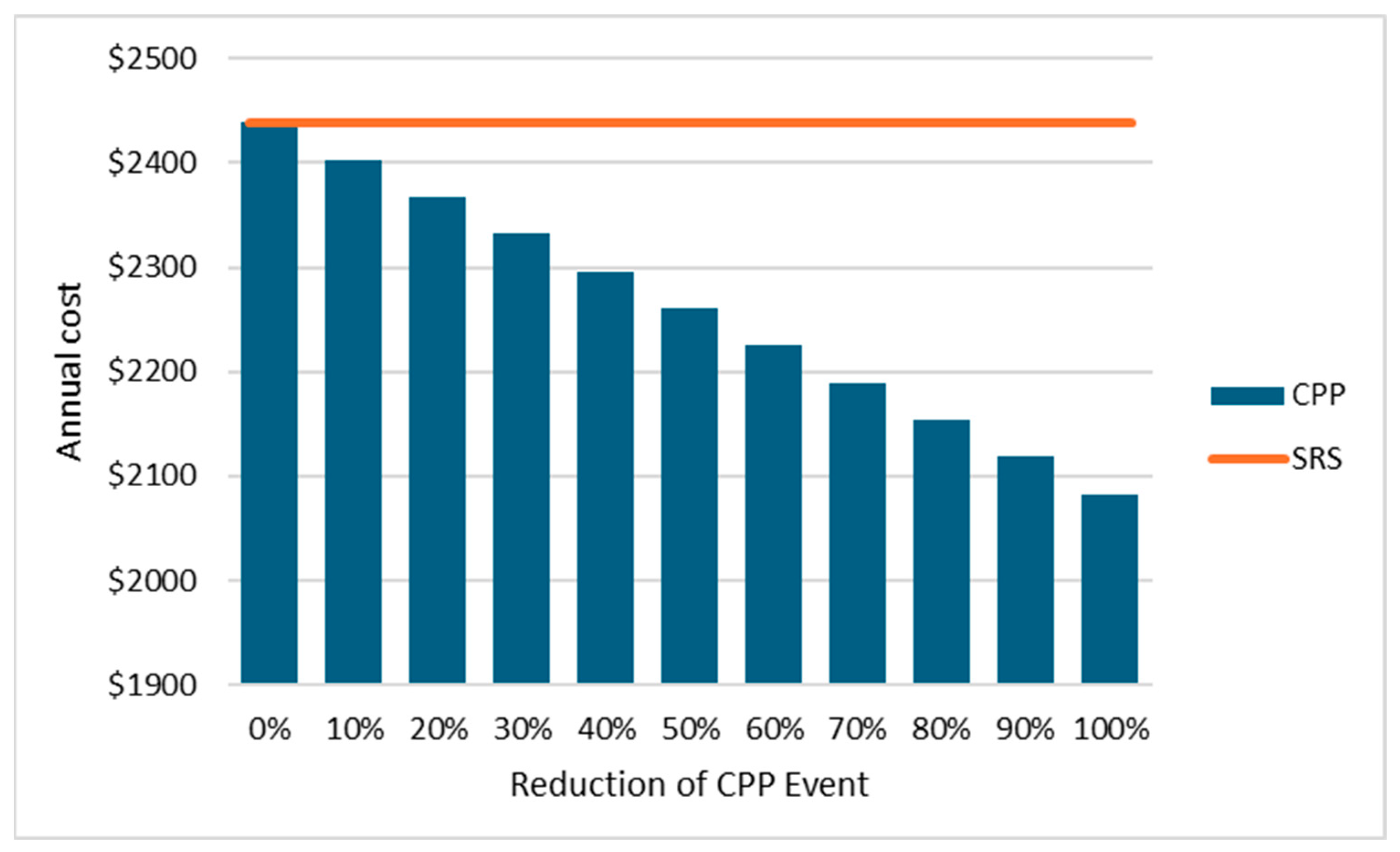

One of the arguments for time-varying pricing is that it can encourage consumers to change their consumption habits, either reducing it or shifting it to a non-peak time. Both actions will reduce a customer’s overall costs.

Figure 4 shows the effect of shifting consumption from CPP events to non-events, assuming the same total consumption of 13,140 kilowatt-hours. If 50% of the event load is shifted, the CPP cost is

$2260 and a savings of

$178 is realized. If 90% of the load is shifted, the total savings are

$320. Savings such as these could be achieved if, for example, the consumer did not have a baseboard heater but used a storage heat (charged overnight) or a secondary heating source such as wood or propane; a heat pump could reduce costs further, even if operated during the events.

The electricity supplier faces a potential problem if loads are shifted immediately after the event ends. In these situations, a secondary or delayed peak could occur, with the supplier being forced to meet the shifted loads. This could occur if, for example, large numbers of electric vehicles began charging at the end of an event.

4.3. The Customer’s Dilemma

The dilemma facing an electricity customer considering changing from the SRS tariff to a time-varying tariff is not only whether to change tariffs, but which new tariff to select, TOU or CPP. This decision is complicated by the fact the customer must know their hourly consumption for the upcoming year. One approach is to use the previous year’s hourly consumption data (from 1 April to 31 March) and determine its effect depending on the tariff.

With TOU, the customer needs to determine their electricity use during the non-winter hours and winter peak hours from their hourly consumption data. If the ratio shown in Equation (25) is applied and exceeds 3.0756, they can switch to the TOU tariff.

The CPP tariff is more complicated since there is no indication at the start of the year of the number of events or when the events will occur. For example, between 1 November 2024 and 31 March 2025, three events occurred on 22 December 2024 (5:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m.) and 23 December 2024 (7:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m.) [

20]; the timing of these events could have been disruptive for a residential customer with plans for seasonal festivities such as Christmas. However, by using their previous year’s hourly consumption and calculating the energy consumed during the events that occurred, if this is less than 1.747% of the year’s total energy, they can change their tariff to CPP.

Nova Scotia Power’s customers have access to their hourly consumption data; a customer could take this data and apply the methods described in this paper to determine whether they should switch from SRS to either the TOU or CPP tariff. Alternatively, prior to the sign-up date for the tariffs, Nova Scotia Power could notify its residential customers of the potential benefits, if any, of changing tariffs using the previous year’s data.

4.4. Nova Scotia Power’s Review of Its Time-Varying Pricing Rates

In 2024, Nova Scotia Power conducted a study of its Time-Varying Pricing rate for 2023. The study focused on participants, load shifting by consumer class, and winter peak load reductions. It assumes static consumption profiles and does not account for behavioral variability, appliance efficiency, or future rate adjustments. Additionally, external factors such as weather fluctuations, income levels, or adoption of new technologies (e.g., EVs, heat pumps) could alter consumer responses to time-varying tariffs. As such, the equilibrium results should be interpreted as indicative thresholds rather than exact predictions for individual households.

The findings of this study align with Schittekatte et al. and Matisoff et al., who concluded that time-of-use pricing tends to benefit households with flexible summer loads, while critical peak pricing achieves broader participation and higher demand reduction [

3,

5]. The identified equilibrium thresholds for Nova Scotia confirm that CPP offers greater accessibility for most households, consistent with global evidence that event-based tariffs provide more equitable and manageable cost savings for typical consumers.

The relative advantage of CPP over TOU in Nova Scotia is partly attributable to its winter-dominant load profile, where heating demand drives peak consumption. In cooling-dominant regions, such as southern U.S. states or other regions including Mediterranean climates, TOU structures may become more attractive due to predictable summer peaks and opportunities for automated load shifting. Moreover, as electric vehicle (EV) adoption increases, TOU pricing becomes particularly relevant during the “driving season” from May to October, when higher mobility leads to increased home charging demand. TOU tariffs can incentivize EV owners to shift charging to off-peak hours, leveraging overnight baseload capacity and mitigating evening peak stress. Hence, the model’s outcomes are most applicable to heating-oriented markets, but its implications extend to emerging electrification patterns—such as EV charging—where TOU pricing could complement seasonal variations in load behavior.

4.4.1. Program Participation and Behavioral Insights

Who Could Participate

The TOU and CPP initiatives were voluntary pilot programs offered by Nova Scotia Power [

21]. Residential, Small General, and General Demand customers were eligible, although most enrollees were residential. Recruitment mainly occurred in September and October each year through bill inserts, email campaigns, and online advertisements. In Year 3, approximately 189,000 printed and 324,000 digital notices were distributed, generating 31,149 webpage visits and 2916 confirmed conversions. Despite extensive outreach, total participation remained below 1 percent of Nova Scotia Power’s residential base, indicating limited public awareness, motivation to enroll, or understanding of the programs.

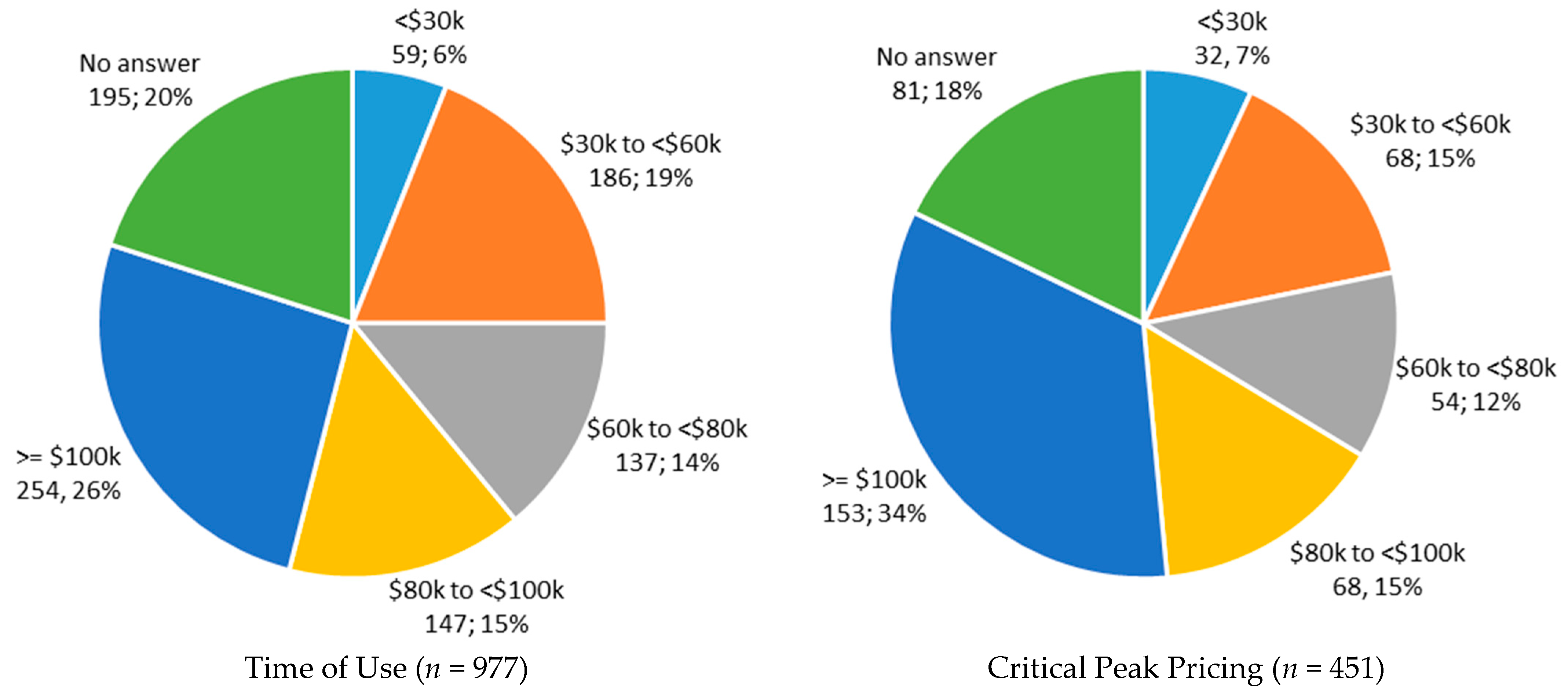

Who Did Participate

Participation data revealed that the pilot programs predominantly attracted higher-income and electrically heated households. In Year 3, 1629 new TOU and 651 new CPP customers joined the programs with approximately 70% of participants using electric heating, well above the provincial average of around 47% [

22]. Income profiles show that 41 percent of TOU and 49% of CPP participants reported annual household incomes exceeding

$80,000, suggesting that early adopters were more affluent and technically engaged, often owning to programmable or remotely controllable heating systems.

Table 6 summarizes participation trends across three program years, while

Table 7 shows Year 3 enrolment interest and acceptance rates.

Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of participants by heating source, highlighting that electrically heated households formed the largest share of program participants compared to oil or other heating systems. The strong bias toward electrically heated homes suggests that customers who already depend on electricity for space heating are more responsive to time-varying tariffs, as these consumers can more readily adjust their heating schedules to reduce costs during peak periods. This also indicates that the TOU and CPP initiatives primarily appealed to households with higher potential for short-term demand flexibility.

Why They Stayed

Survey feedback (summarized in

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10) indicates that participants mainly remained in the programs for financial and behavioral reasons rather than technology upgrades. The most frequent motivation was saving money through off-peak rates (60% to 76%) and finding it easier to plan around peak periods. Behavioral shifts were widespread: 82% changed laundry timing, 63% ran dishwashers overnight, and 62% kept lights off during peak hours. Heating-related changes also increased to 47%, showing greater awareness of heating schedules. Despite these adaptations, technology upgrades remained limited: only 16% installed smart thermostats and 14% added smart plugs.

4.4.2. Alternative Approaches Beyond TOU and CPP

While the TOU and CPP tariffs tested in Nova Scotia provided useful insights into consumer responsiveness to time-varying electricity prices, global experience suggests several alternative mechanisms that can achieve similar or greater behavioral impacts with fewer equity or participation concerns. This section reviews three notable approaches: (1) Ireland’s national TOU experiment, (2) the United Kingdom’s Octopus Power “Powerups” incentive model, and (3) real-time pricing (RTP) frameworks based on bi-level programming optimization models.

The Irish Smart Meter Trials

Ireland’s national smart meter trials (2010–2011) tested several TOU tariff structures with varying peak-to-off-peak price differentials [

23]. The trials demonstrated that even modest price spreads less than 2:1 between peak and off-peak rates can yield measurable demand reductions of 8–10% during peak hours. Importantly, behavioral engagement, rather than large price differentials, drove most of the observed changes.

Participants responded most positively when tariffs were coupled with clear communication, in-home displays, and feedback on usage patterns. This suggests that the effectiveness of TOU pricing is not solely a function of the price ratio, but of the informational and behavioral context in which consumers operate. Ireland’s experience also highlights that simpler pricing signals with transparent benefits can generate trust and sustained participation, an important lesson for Nova Scotia, where recruitment and retention remain limited.

The Octopus Power “Powerups” Model (United Kingdom)

The UK’s Octopus Energy Powerups initiative provides an alternative to punitive peak pricing [

24]. Instead of imposing higher prices during critical periods, Octopus offers customers time-limited discounts to encourage consumption shifts toward low-demand hours. For example, participants receive notice a few hours before a “Powerup” period—typically overnight or during high renewable generation—and can use electricity at sharply reduced or even zero marginal cost.

This “positive reinforcement” approach has achieved notable consumer buy-in, reducing resistance often seen with CPP programs that rely on price penalties. Early results show high participation rates and a strong sense of engagement, as customers perceive these events as rewards rather than restrictions. Importantly, this aligns with behavioral economics research showing that consumers respond more consistently to incentives framed as gains rather than losses.

For Nova Scotia, incorporating reward-based mechanisms within a future demand response portfolio could enhance equity and participation, especially among low-income or risk-averse consumers who may otherwise avoid dynamic tariffs.

Real-Time Pricing via Bi-Level Programming Models

A more advanced alternative to TOU and CPP is real-time pricing (RTP), where prices fluctuate continuously based on actual system conditions. The work by Li et al. demonstrates how a bi-level programming framework can effectively coordinate real-time price signals with consumer response models [

25].

In Li et al.’s approach, the upper-level optimization problem represents the system operator’s objective of minimizing overall operating costs, while the lower-level model captures the aggregated response of consumers (including households and EV owners) seeking to minimize their electricity expenditures under these dynamic prices. The study found that real-time pricing can yield up to 15% reduction in peak load and 12 percent lower system operating costs compared to static TOU schemes.

Such models, if adapted to Nova Scotia’s grid conditions, could allow more granular demand flexibility while maintaining system stability. However, successful implementation would require robust metering infrastructure, automated control systems, and consumer education to mitigate complexity and ensure fairness.

5. Conclusions

This paper examined the financial implications to residential customers of two time-varying pricing (TVP) structures introduced by Nova Scotia Power, Time-of-Use (TOU) and Critical Peak Pricing (CPP), in comparison to the existing SRS tariff. The study identified the specific consumption patterns under which each TVP rate would become more cost-effective than the flat-rate SRS structure.

In the case of TOU, the analysis revealed that for a customer to benefit over the SRS rate, their non-winter electricity consumption must be at least 3.0756 times greater than their winter-peak usage. This consumption profile is atypical for most Nova Scotian households, which tend to have high electricity usage during winter peaks due to electric heating and days with less daylight. As a result, the TOU structure would not offer cost savings for most SRS customers unless they have unusually low winter peaks or non-winters loads, such as electric vehicle charging or extensive air conditioning use.

In contrast, the CPP model allows for significant savings even with minimal behavioral adjustments. The equilibrium analysis showed that a customer using 13,140 kWh annually could shift just 1.75% of their consumption (approximately 229.5 kWh) away from critical peak periods to match the cost of the SRS rate. If that same customer entirely avoided usage during CPP events, they would reduce their annual electricity bill by $813. Even partial reductions in event consumption, such as shifting 50% or 90% of event load, would still result in savings of $178 and $320, respectively.

The findings indicate that the TOU model requires a disproportionately high ratio of non-winter to winter-peak consumption to yield savings over the SRS rate, a condition unlikely to be met by most households, particularly those with winter-dominant loads. Whereas, the CPP model offers more favorable cost outcomes under typical residential consumption patterns, provided customers can manage their electricity use during the limited number of critical peak events. The relative simplicity of achieving cost parity with the SRS tariff under the CPP framework requiring only modest reductions in event-period usage suggests that it presents a more practical and financially beneficial option for most residential customers. Therefore, the CPP tariff structure holds greater potential for promoting both affordability and demand-side responsiveness within Nova Scotia’s residential electricity sector.

Future Work

When introducing new tariffs, both policymakers and electricity providers on how to structure tariffs that balance affordability, efficiency, and fairness. The methods described in this paper show how new tariffs can be compared with existing ones, allowing customers to understand the potential costs and benefits of changing tariffs.

Future work will also examine how improvements in consumer education and communication can increase the adoption and effectiveness of time-varying pricing programs in Nova Scotia. Given the low participation rates in both TOU and CPP, a key priority is ensuring that households clearly understand the potential bill impacts of each tariff. One practical approach we are engaged in is encouraging Nova Scotia Power to adjust its bimonthly billing format to include simple cost comparisons among the SRS, TOU, and CPP rates based on each customer’s actual consumption. This would provide households with personalized, transparent information on the potential savings available under different rate structures. Similarly, we are also discussing with Nova Scotia Power possible enhancements to its customer web portal to allow users to instantly compare their costs across the three tariffs using their own historical usage data. Evaluating the impact of such educational tools and decision-support features would help clarify how better information can improve or enhance program participation, consumer choice, and system-level benefits in emerging TVP frameworks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.H.; methodology, L.H.; software, L.H.; validation, L.H.; investigation, L.H. and M.H.S.; resources, L.H. and M.H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.H. and M.H.S.; writing—review and editing, L.H. and M.H.S.; visualization, L.H.; supervision, L.H.; project administration, L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sandy Cook for proofreading the final draft of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CPP | Critical Peak Pricing |

| CPP.NEv.kWh | Annual energy consumption during Critical Peak Pricing non-event periods (kWh) |

| CPP.Ev.Cost | Annual energy cost during Critical Peak Pricing non-event periods ($) |

| CPP.Ev.kWh | Annual energy consumption during Critical Peak Pricing event periods (kWh) |

| CPP.Ev.Cost | Annual energy cost during Critical Peak Pricing event periods ($) |

| NSUARB | Nova Scotia Utility and Review Board |

| RTP | Real Time Pricing |

| SRS | Standard Residential Service |

| SRS.kWh | Annual energy consumption for Standard Residential Service tariff (kWh) |

| TOU | Time of Use |

| TOU.NW.kWh | Annual non-winter energy consumption for TOU tariff (kWh) |

| TOU.WOP.kWh | Annual winter off-peak energy consumption for TOU tariff (kWh) |

| TOU.WP.kWh | Annual winter peak energy consumption for TOU tariff (kWh) |

| TOU.NW.Cost | Annual non-winter energy consumption for TOU tariff ($) |

| TOU.WOP.Cost | Annual winter off-peak energy consumption for TOU tariff ($) |

| TOU.WP.Cost | Annual winter peak energy consumption for TOU tariff ($) |

| NSP | Nova Scotia Power |

References

- Energy Sustainability Directory. Energy Sustainability Directory. Retrieved from Energy Sustainability Directory—Term—TOU Tariffs. Available online: https://energy.sustainability-directory.com/term/tou-tariffs/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Faruqui, A.; Sergici, S. Household response to dynamic pricing of electricity: A survey of 15 experiments. J. Regul. Econ. 2010, 38, 193–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schittekatte, T.; Mallapragada, D.; Joskow, P.; Schmalensee, R. Electricity Retail Rate Design in a Decarbonized Economy: An Analysis of Time-of-Use and Critical Peak Pricing. Energy J. 2024, 45, 25–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Alcaraz, G. Dynamic pricing and area-time specific marginal capacity cost for distribution investment deferment. In Proceedings of the IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting, Detroit, MI, USA, 24–28 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Matisoff, D.C.; Beppler, R.; Chan, G.; Carley, S. A review of barriers in implementing dynamic electricity pricing to achieve cost-causality. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 093006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSP Nova Scotia Power—Standard Residential Service Rate. Available online: https://www.nspower.ca/your-home/residential-rates/standard-residential (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- SP Group. SP Group, Singapore. 2025. Available online: https://www.spgroup.com.sg/our-services/utilities/tariff-information (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Electric Ireland. Electric Ireland, Belfast, Northern Ireland. 2025. Available online: https://www.electricireland.ie/switch/new-customer/price-plans?priceType=E (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Ontario Energy Board. Ontario Energy Board, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. 2025. Available online: https://www.oeb.ca/consumer-information-and-protection/electricity-rates (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- PGE. Pacific Gas and Electric, California, USA. 2025. Available online: https://www.pge.com/assets/pge/docs/account/rate-plans/residential-electric-rate-plan-pricing.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Aurora Energy Aurora Energy. 2025. Available online: https://www.auroraenergy.com.au/residential/products/residential-all-prices (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- MIT CEEPR MIT Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research. 2022. Available online: https://ceepr.mit.edu/electricity-retail-rate-design-in-a-decarbonizing-economy-an-analysis-of-time-of-use-and-critical-peak-pricing/ (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- EDF. 2025. Available online: https://particulier.edf.fr/fr/accueil/gestion-contrat/options/tempo/details.html? (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- NSP Nova Scotia Power—Critical Peak Pricing. 2025. Available online: https://www.nspower.ca/your-home/residential-rates/critical-peak (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Zaki, D.A.; Hamdy, M. A Review of Electricity Tariffs and Enabling Solutions for Optimal Energy Management. Energies 2022, 15, 8527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabobank, R. 2023. Available online: https://www.rabobank.com/knowledge/d011381352-rethinking-electricity-tariff-design-in-the-era-of-empowered-customers (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- NSP Nova Scotia Power—Who We Are. 2025. Available online: https://www.nspower.ca/about-us/who-we-are (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Canlii Canadian Legal Information Institute. 2025. Available online: https://www.canlii.org/en/ns/laws/stat/sns-2004-c-25/latest/sns-2004-c-25.html (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- NSP Nova Scotia Power—Time-of-Use Rate Pilot. 2025. Available online: https://www.nspower.ca/your-home/residential-rates/time-of-use (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- NSP Nova Scotia Power—Upcoming Critical Peak Events. 2025. Available online: https://www.nspower.ca/your-home/residential-rates/critical-peak-pricing/critical-peak-events#events (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Nova Scotia Energy Board. Time-Varying Pricing Pilot Program—2023/24 (Year Three) Evaluation Report. Matter No. M11823. 2024. Available online: https://uarb.novascotia.ca/fmi/webd/UARB15 (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Natural Resources Canada, Office of Energy Efficiency. Residential Sector, Nova Scotia, Table 21: Heating System Stock by Building Type and Heating System Type. 2024. Available online: https://oee.nrcan.gc.ca/corporate/statistics/neud/dpa/showTable.cfm?type=CP§or=res&juris=ns&year=2022&rn=21&page=0 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Commission for Energy Regulation. CER Electricity Smart Metering Customer Behaviour Trials (CBT) Findings Report; Commission for Energy Regulation: Dublin, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Octupus Energy Octupus Energy. 2025. Available online: https://octopus.energy/power-ups/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Li, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, G.; Mu, Y.; Zhao, D.; Chen, C.; Shen, B. Optimal scheduling of isolated microgrid with an electric vehicle battery swapping station in multi-stakeholder scenarios: A bi-level programming approach via real-time pricing. Appl. Energy 2018, 232, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).