Abstract

Electricity generation is the largest contributor to anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This review synthesizes life cycle assessment (LCA) evidence for major power generation technologies published from 2015 to 2025. Using a structured screening approach, it identifies consistent cross-technology patterns and the methodological factors driving variation in reported results. Unabated coal and oil show the highest life cycle intensities; natural gas varies widely with methane management; and nuclear, geothermal, hydropower, wind, and solar power generally fall one to two orders of magnitude lower. Differences arise mainly from upstream processes, siting conditions, and system boundary definitions. Key mitigation levers include plant efficiency improvements, methane abatement, carbon capture and storage (CCS), and low-carbon manufacturing. The review also highlights how emerging policies—including the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and China’s carbon-footprint standards—are integrating life cycle and Scope-2 accounting. Standardized, AR6-aligned LCA practices and transparent upstream data remain essential for credible, comparable electricity-sector decarbonization.

1. Introduction

Electricity generation is one of the largest sources of anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and thus represents a decisive arena for achieving global climate targets. The power sector contributes over 40% of global energy-related CO2 emissions, making the carbon intensity of electricity a key determinant of both direct emissions and the embodied carbon of electricity-intensive industries such as steel, aluminum, and chemicals [1,2]. Recent analyses show that the electricity generation sector alone accounts for 52.9% of carbon footprints among Chinese-listed companies, underscoring its systemic importance for national and global decarbonization [3]. As electrification expands rapidly across transport, industry, and buildings, understanding the life cycle carbon footprint of electricity supply has become increasingly critical to ensure that renewable transitions deliver genuine climate benefits.

The electricity carbon footprint (ECF), typically expressed in CO2 equivalents per kilowatt-hour (CO2e/kWh), quantifies total GHG emissions associated with electricity generation from resource extraction to decommissioning [4,5]. Compared with conventional production-based inventories, ECF accounting reveals upstream and downstream emissions that are often overlooked, providing a more holistic view of the true climate burden of power systems [6]. This perspective is particularly relevant for low-carbon and renewable technologies, whose operational emissions are near zero but whose material and infrastructure requirements remain carbon-intensive [7].

Over the past two decades, life cycle assessment (LCA) has been widely applied to quantify the carbon footprints of various electricity generation technologies. Results consistently show that fossil fuel-based systems, especially coal-fired power, remain the most carbon intensive, while natural gas exhibits lower but highly variable footprints depending on methane management and fuel logistics [8,9]. In contrast, renewable technologies such as wind and solar photovoltaics display substantially lower life cycle emissions, though results vary with manufacturing processes, lifetimes, and regional contexts [10,11]. Hydropower and nuclear power demonstrate additional complexity: reservoir emissions and fuel cycle assumptions can lead to diverging outcomes across studies [12,13,14,15]. These differences not only reflect technological heterogeneity but also methodological choices, including system boundaries, database selection, and allocation procedures [16,17].

Despite extensive progress, key challenges remain. Reported life cycle intensities often diverge by factors of two to five for the same technology, reflecting inconsistent assumptions and incomplete upstream data [18]. Debates persist over the inclusion of biogenic carbon in hydropower, the treatment of methane leakage in natural gas systems, and the proper accounting of land use change in biomass power. These methodological discrepancies limit comparability across studies and hinder the effective use of LCA results for policy and investment.

Therefore, this review aims to synthesize and harmonize recent life cycle evidence (2015–2025) across fossil, renewable, and nuclear power technologies. It seeks to (i) establish an up-to-date picture of life cycle GHG intensities across major generation pathways, (ii) identify the methodological and contextual factors that drive cross-study variability, and (iii) clarify how life cycle evidence can support emerging policy instruments such as the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and China’s developing carbon-footprint standards. By consolidating these aspects, the review highlights consistent cross-technology patterns, explains key sources of uncertainty, and provides a foundation for developing more standardized and IPCC AR6-aligned LCA protocols that can strengthen both scientific comparability and regulatory applicability.

2. Methodology

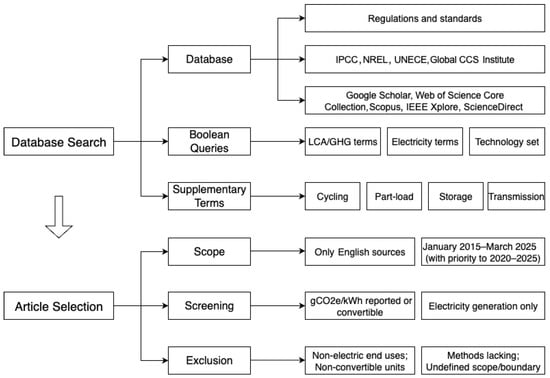

This review applies a focused narrative synthesis to evaluate life cycle greenhouse gas (GHG) intensities across major electricity generation technologies. The approach combines (i) a structured literature search, (ii) harmonized eligibility and screening rules, and (iii) interpretive synthesis of heterogeneous LCA evidence. The objective is to ensure methodological transparency while accommodating the diversity of system boundaries, functional units, and modeling conventions characteristic of the electricity LCA literature. The technology scope covers coal, natural gas/NGCC, oil-fired generation, CCS-equipped systems, hydropower, and wind (onshore/offshore), solar (PV/CSP), biomass/BECCS, nuclear, geothermal, and ocean energy technologies. The review window spans January 2015 to March 2025, supplemented by selectively cited pre-2015 studies only where necessary to contextualize methodological developments or to reference foundational syntheses that continue to serve as authoritative benchmarks in electricity LCA research.

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

Peer-reviewed studies were retrieved independently from Google Scholar, Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, and ScienceDirect using Boolean combinations that paired general LCA-related terms (“life-cycle assessment”, “GHG intensity”, “carbon footprint”) with technology-specific keywords (e.g., “coal LCA”, “NGCC methane”, “PV manufacturing emissions”, “wind turbine embodied carbon”, “hydropower reservoir CH4”). Broader system-effect modifiers (e.g., “cycling”, “part-load”, “storage”, “transmission expansion”) were also incorporated to capture operating-profile influences. For full transparency, the complete list of Boolean search strings and technology-specific keyword sets used across all databases is provided in the Supplementary File. Backward and forward citation searches identified additional relevant studies. Because each database returns overlapping but not identical records—including editorials, policy papers, non-convertible LCAs, and technical briefs—database-specific retrieval counts do not provide meaningful reproducibility; instead, transparency is ensured through explicit eligibility criteria and consistent screening procedures.

2.2. Screening and Eligibility Rules

Screening proceeded in two stages. First, titles and abstracts were screened to remove non-LCA studies, non-electricity analyses, and publications lacking methodological content. Second, full-text assessments evaluated whether a study (a) reported or could be converted to g CO2e/kWh, (b) specified a functional unit, system boundary, and global warming potential (GWP) time horizon, and (c) provided sufficient methodological detail to recover assumptions. Studies with unclear or non-convertible units, incomplete boundaries, or missing inventory information were excluded. Conference abstracts, media summaries, and unofficial regulatory drafts were omitted. Policy and standards documents were included only when officially issued or endorsed and when electricity-specific treatment was explicit.

2.3. Evidence Base and Scope

Across all databases, the searches produced several hundred initial records. After removing duplicates and applying the screening criteria described above, 172 references were retained in the final evidence base. Of these, approximately 111 are peer-reviewed life cycle or carbon footprint studies that report quantitative GHG intensities for one or more electricity generation technologies. An additional ~18 publications are systematic reviews or meta-analyses, which synthesize prior LCA evidence and help contextualize methodological variation across studies. A further ~12 studies provide energy system, operational, or environmental mechanisms that inform the interpretation of life cycle drivers without being LCAs themselves. The remaining ~31–41 documents consist of policies, standards, regulations, and official technical reports used to link the technical findings to evolving governance frameworks.

Given the narrative, cross-technology nature of this review—and the heterogeneity of underlying methods, reported units, system boundaries, and GWP choices—aggregate-level retrieval counts are more appropriate than PRISMA-style database-specific reporting, which would imply a level of harmonization unsupported by the literature. The overall workflow for evidence identification, screening, and synthesis is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Methodological Workflow for this Review.

2.4. Managing Methodological Heterogeneity and Potential Biases

Consistent with best practices for narrative LCA reviews, this study applies interpretive rather than numerical harmonization. When studies differed in boundary definitions (e.g., cradle-to-gate vs. cradle-to-grave), GWP choices (AR4/AR5/AR6), or upstream modeling assumptions (e.g., methane leakage in gas systems, reservoir biogeochemistry in hydropower, manufacturing-grid carbon intensity in PV/wind), their results were grouped and interpreted within comparable methodological categories rather than recomputed. Outliers were retained and contextualized with respect to their underlying drivers instead of being statistically removed. Geographic and technological biases were mitigated through broad database coverage, cross-comparison of independent datasets, and prioritization of recent studies with transparent inventory documentation.

2.5. Treatment of Technical Descriptors

Life cycle GHG emissions are consistently reported in grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per kilowatt-hour (g CO2e/kWh) using 100-year GWPs from the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) unless the original study specifies otherwise. The functional unit is defined as net electricity generated (kWh). System boundaries follow standard LCA classifications and may include construction, upstream fuel processing, transport, operation, and decommissioning. Commonly used technical descriptors—such as capacity factor, power density, upstream fuel pathway characteristics, or reservoir methane processes—are interpreted following conventional definitions in the electricity LCA literature. For studies with multiple operating or load-factor scenarios, values were extracted as originally reported, and scenario-specific assumptions were preserved rather than recalculated; operating profile effects are incorporated qualitatively in Section 6.2.

3. Fossil Fuel-Based Power

A comprehensive assessment of fossil-based power requires a systematic examination of life cycle emissions across coal, natural gas, and oil-fired technologies. These conventional generation pathways continue to dominate global electricity production despite increasing renewable energy deployment, necessitating detailed understanding of their environmental impacts throughout the entire value chain. The complexity of fossil fuel carbon footprints extends beyond direct combustion emissions to encompass upstream extraction, processing, transportation, and downstream waste management processes, each contributing distinct emission profiles that vary significantly across technologies and operational contexts.

3.1. Coal Power

Coal-fired power generation remains the most carbon-intensive electricity generation pathway globally. Recent LCA syntheses report emissions typically ranging from approximately 751 to 1095 g CO2e/kWh, with a widely cited median around 820 g CO2e/kWh, although the precise range depends on coal quality, plant efficiency, and system boundary assumptions [19,20]. In China, coal power continues to dominate electricity supply and constitutes the single largest obstacle to power sector decarbonization, accounting for roughly 44% of national CO2 emissions [21].

The bulk of coal’s life cycle carbon footprint arises from combustion, which generally contributes more than 80% of total emissions [16,19,22]. Nevertheless, upstream processes such as mining, coal preparation, and transport are also non-negligible. Diesel consumption in extraction, beneficiation energy use, and coal mine methane (CMM) releases can meaningfully increase the upstream carbon burden of coal power with the magnitude varying by region and supply chain configuration (e.g., methane management, transport distance and mode). Recent reviews identify CMM as a particularly important driver of upstream variability [23], while energy use and emissions during the mining process also vary considerably with extraction techniques [24]. Transport-related contributions depend strongly on mode and distance, with long-haul movement and higher shares of road transport generally resulting in greater upstream emissions [20].

Plant efficiency is widely recognized as the most critical technological factor shaping emission intensities. Subcritical units generally operate at 33–37% efficiency, whereas supercritical and ultra-supercritical designs can achieve 42–48%, reducing specific emissions by up to 100–250 g CO2e/kWh [19,20]. While China’s coal fleet has approached international best-practice efficiency levels, opportunities for further improvements remain limited, underscoring the need for structural transformation and the deployment of carbon capture and storage (CCS) [21]. Coal quality is another determinant of carbon intensity: lignite and sub-bituminous coals, with their lower heating values and higher moisture content, tend to exhibit 15–25% higher emissions per unit of electricity than bituminous coals, leading to systematic regional differences depending on local resource availability [20,25,26].

CCS remains the most direct technological pathway for deep decarbonization of coal-fired power. Post-combustion capture systems with around 90% capture rates can dramatically reduce stack emissions, yet LCAs typically report net reductions in the range of 60–85% once energy penalties and the infrastructure required for transport and storage are included [21,27,28]. These penalties are typically reported as net efficiency losses of about 8–12 percentage points in earlier OECD/IEA assessments, while more recent studies suggest a somewhat wider range of ~8–14 percentage points, increasing upstream fuel use and moderating the overall benefit [29,30,31]. According to recent UNECE data, coal plants equipped with CCS achieve between 147 and 469 g CO2e/kWh, considerably lower than unabated coal but still above most renewable options [19].

In addition to technology and fuel characteristics, operational dynamics are emerging as an increasingly important factor in life cycle performance. With the growing share of variable renewable energy (VRE), coal units are more frequently operated in load-following modes that involve ramping, start-ups, and part-load operation. Recent LCA studies that account for these conditions demonstrate that effective emission intensities rise substantially relative to steady full-load operation [32]. This evidence highlights that dynamic operational characteristics, together with technological upgrades and CCS deployment, must be considered to fully capture the climate implications of coal-fired power.

3.2. Natural Gas Power

Natural gas-fired power generation generally exhibits lower life cycle emissions than coal. Recent assessments report an average intensity of around 645 g CO2e/kWh, with values spanning ~330–1400 g CO2e/kWh across different jurisdictions, largely reflecting plant efficiency and methane management [33]. Modern combined-cycle gas turbine (NGCC) units typically fall in the 430–550 g CO2e/kWh range, compared with ~620 g for open-cycle plants, while liquefied natural gas (LNG)-based systems often exceed these values due to liquefaction and transport burdens [34,35,36,37]. These results confirm a clear advantage over coal but highlight the sensitivity of gas footprints to upstream and supply chain conditions.

Methane leakage is the most critical and uncertain driver of this variability. Conventional systems with strong management often report leakage near ~1% [37], whereas unconventional shale operations show higher intensities due to flowback venting, flaring, and dense well development. Satellite- and aircraft-based observations further suggest that actual methane emissions can exceed inventories by factors of 1.2–1.7 in some regions, indicating systematic underestimation [38,39]. Given methane’s 100-year GWP of 27–30× CO2 [40], even modest leakage rates can materially inflate the life cycle footprint of natural gas. Regional clustering of shale wells and associated infrastructure may create emission hotspots, though mitigation measures such as green completions can reduce methane by up to ~90% under favorable conditions [41,42].

Infrastructure also imposes a notable carbon burden in the gas supply chain. Pipeline compression and processing add incremental emissions, while LNG systems are particularly energy-intensive: liquefaction consumes 6–10% of the gas’s energy content, long-distance shipping adds ~50 g CO2e/kWh, and regasification further increases the footprint. Collectively, LNG infrastructure can account for 20–30% of total life cycle emissions [37,43,44], underscoring the strong dependence of gas carbon intensity on transport mode and distance.

At the generation stage, efficiency and operating profile remain decisive. Simple-cycle plants are inherently less efficient, while combined-cycle units achieve lower emission intensities under baseload conditions. However, empirical studies show that partial-load operation significantly erodes these advantages: NGCC plants running at 60% load experience ~10% efficiency losses, and at 40% load losses exceed 15%, raising per-MWh emissions by 15–25% relative to full-load operation [45,46]. With increasing requirements for flexible ramping to balance renewables, such operational penalties are becoming more relevant, though gas turbines still retain superior part-load performance compared with coal units.

CCS can substantially reduce the life cycle carbon footprint of natural gas NGCC plants, though its effectiveness depends on capture efficiency, upstream practices, and system integration. Under best-case conditions, CCS-equipped NGCC facilities may approach the carbon intensity of renewable options [47]. Upstream mitigation measures, such as tighter methane control, further enhance its effectiveness [48]. Case-specific assessments—for example, an Iraqi NGCC with post-combustion capture—report GWP reductions of about 28% compared to unabated plants [49]. Yet CCS deployment entails significant energy penalties: recent studies indicate efficiency losses on the order of 8–12 percentage points, raising fuel demand and moderating net benefits [50]. Economically, widespread adoption remains constrained by high capture costs and uncertain carbon pricing, with recent estimates placing break-even levels above current market prices [47,51].

3.3. Oil-Fired Power

Oil-fired power generation plays only a marginal role in today’s global electricity mix yet remains one of the most carbon-intensive fossil options, with life cycle emissions often comparable to or exceeding those of coal. According to NREL’s harmonized dataset, lifecycle values typically range from 722 to 907 g CO2e/kWh, with higher intensities linked to low plant efficiencies and energy-intensive upstream processes [52]. A detailed case study of a 500 MW oil-fired steam turbine plant in Sudan reported a lifecycle impact of approximately 1.08 kg CO2e/kWh, underscoring the scale of emissions associated with this technology [53].

Most emissions originate from the combustion phase—typically over 80% of total lifecycle impacts—but upstream extraction, refining, and transport add non-negligible contributions. Crude oil production often involves flaring and venting, particularly in offshore or heavy-oil fields, while refinery operations are highly energy-intensive, adding roughly 50–120 g CO2e/kWh depending on crude characteristics [53]. These upstream processes collectively amplify total GHG intensity, and maritime transport further elevates emissions, especially for imported fuel oils used in isolated grids.

The inherently low efficiency of oil-fired steam turbines—commonly 30–35%—exacerbates their lifecycle intensity and limits their economic competitiveness. Recent system modeling in Japan highlights that such plants, with long technical lifetimes (36–46 years) and low-capacity factors (~30%), contribute to carbon lock-in when replacement with renewables or gas is delayed [54]. Similar patterns are observed in developing economies where oil power remains in operation: in Pakistan, techno-economic analyses show that replacing oil-based generation with local lignite via UCG-IGCC could reduce lifecycle CO2 emissions by over 80% while improving efficiency to about 44%, though the levelized cost remains around 0.09 USD/kWh [55].

The deployment of CCS in oil-fired power plants is virtually nonexistent. With the rapid decline of oil-based generation capacity and the aging of existing units, retrofitting CCS is technically feasible but economically unjustified due to high costs and limited remaining lifetimes [56,57]. Accordingly, current decarbonization strategies prioritize the phase-out of oil-fired power, particularly in small island and off-grid systems where such plants persist for reliability reasons. In these regions, hybrid configurations combining renewables and battery storage are emerging as the primary replacement pathway [56,57].

4. Renewable Power

Renewable energy technologies such as hydropower, wind, solar, and biomass have become central to global decarbonization pathways. While their operational emissions are close to zero, LCAs reveal that upstream and infrastructure-related processes still contribute measurable carbon footprints. The following sections examine the life cycle characteristics of major renewable power technologies and their key drivers of emission variability.

4.1. Hydropower

Hydropower presents a complex case study in renewable energy assessment, with emissions varying considerably. Comprehensive reviews reveal hydropower emissions ranging from 0.11 to 54.7 g CO2e/kWh, with median values of 7.6 g CO2e/kWh and mean emissions of 12.8 g CO2e/kWh [58]. Run-of-river facilities generally lie at the low end [58,59], whereas reservoir-based projects show substantial variability driven by three well-established sensitivity factors.

The most significant factor influencing hydropower’s carbon footprint is reservoir-related emissions, which can constitute over 90% of total life cycle emissions, particularly in tropical regions [60]. Recent syntheses show that methane emissions are strongly influenced by temperature, organic carbon content, reservoir age, and residence time, producing far higher intensities in warm regions than in temperate or boreal systems [61,62]. This climate dependence is reflected in regional LCAs. Assessments of 34 hydropower plants in the Yangtze River Basin reveal life cycle intensities of 5.43–49.36 g CO2e/kWh, with ecosystem restoration contributing 1.22–30.35% of total emissions [63]. In contrast, Icelandic LCAs report substantially lower intensities of 0.5–21.1 g CO2e/kWh, dominated by construction-related emissions given the negligible reservoir emissions in cold basins [64]. These results underscore that reservoir GHG processes—not construction, not materials—drive most of the observed global variation.

The second major determinant is power density, defined as installed capacity per unit of flooded area. Empirical analyses consistently demonstrate that projects with higher power density—including run-of-river, high-head, and narrow-valley impoundments—yield substantially lower GHG intensities because emissions are distributed over larger electricity outputs. Conversely, low-density reservoirs with extensive inundation areas—common in tropical regions—tend to occupy the high-emission end of reported ranges [65]. Project design can also shift effective power density: LCAs from Iceland show that extending existing dams rather than constructing new impoundments can reduce construction emissions by up to 95% [64].

The third source of variation arises from methodological differences in how system boundaries are defined, particularly regarding whether reservoir processes and supporting infrastructure are included. Recent analysis of a pumped-storage project shows that indirect upstream emissions can be 2.8 times higher than direct on-site and reservoir emissions [66], meaning an assessment that excludes upstream processes would report only about one quarter of total GWP. Likewise, another report that including biogenic CH4 and CO2 emissions from Québec reservoirs increases the electricity carbon footprint from roughly 17 g CO2e/kWh to 34.5 g CO2e/kWh, effectively doubling the reported intensity [67]. In contrast, recent LCAs of closed-loop pumped-storage systems that exclude reservoir emissions and decommissioning stages yield much lower results, underscoring that boundary scope—rather than physical performance alone—drives major differences across studies. Data limitations further contribute to methodological inconsistencies and may lead to substantial under- or overestimation of reservoir-related emissions [60].

Taken together, reservoir biogeochemistry, power density, and boundary assumptions explain most of the dispersion observed across hydropower LCAs. Reservoir processes define the overall range of feasible values, power density governs structural differences across project types, and boundary definitions determine the degree of methodological consistency. Recognizing these sensitivities is essential when interpreting hydropower results relative to other generation technologies or applying them in policy and system-planning contexts.

Beyond GHG emissions, water consumption represents another critical dimension of hydropower sustainability. Mekonnen and Hoekstra estimated average water footprints of 68 m3/GJ for 35 artificial reservoirs, with significant variations due to differences in flooded area per unit capacity and climatic conditions [68]. Norwegian studies revealed substantial variation in life cycle water consumption rates, emphasizing the need for standardized assessment methodologies [68].

4.2. Wind Power

Wind energy demonstrates consistently low carbon footprints across diverse geographic and technological contexts, though emissions vary with turbine design, material composition, and operational efficiency. LCAs typically report emissions between 7 and 56 g CO2e/kWh, with most modern installations clustering around 10–15 g CO2e/kWh [58,69,70,71]. Recent harmonized reviews confirm that wind power maintains among the lowest life cycle GHG intensities of any large-scale generation technology [70].

Material inputs constitute the dominant source of wind power’s carbon footprint, with steel procurement and related products like pig iron contributing significantly to emissions [69,72]. The manufacturing phase accounts for approximately 80–90% of total life cycle emissions, while operation and maintenance contribute minimally to the overall carbon footprint [73]. Transportation and installation phases typically represent 5–10% of total emissions, varying with project location and turbine size [74,75,76].

Technological improvements continue to reduce wind power’s carbon intensity. Larger turbines with higher capacity factors demonstrate lower emissions per unit of electricity generated, reflecting economies of scale in manufacturing and improved energy capture efficiency [77]. Offshore wind installations, while requiring more intensive materials and installation processes, often achieve superior capacity factors that offset higher embodied emissions [78].

Geographic factors significantly influence wind power’s environmental performance. Coastal regions benefit from superior wind resources and more consistent generation patterns, improving overall system efficiency [77]. However, offshore installations face additional challenges related to transmission infrastructure and maintenance accessibility, potentially affecting long-term emissions profiles. Recent comparative studies further highlight regional differences in offshore wind LCAs, with European projects generally exhibiting lower manufacturing-stage carbon intensities due to cleaner electricity mixes and more mature supply chain processes [76], whereas Asian case studies report higher embodied emissions linked to more carbon-intensive manufacturing pathways and longer component transport distances [70]. Studies in Afghanistan’s Badakhshan province demonstrated how regional wind characteristics and grid integration capabilities influence both technical and environmental performance [73].

The integration of wind power with energy storage systems presents both opportunities and challenges for emission reduction. While storage enhances grid stability and renewable utilization, battery manufacturing and replacement cycles add to system-level carbon footprints. Recent system-level analyses of coupled wind–CCES configurations indicate that although storage integration improves overall energy efficiency and curtails curtailment losses, it also shifts part of the environmental burden to the storage subsystem through material and energy inputs [79,80]. Comprehensive assessments must therefore account for these trade-offs to accurately evaluate wind power’s contribution to decarbonization objectives.

4.3. Solar PV and CSP

Solar PV technology exhibits substantial variation in life cycle carbon footprints, ranging from 18 to 180 g CO2e/kWh depending on manufacturing location, technology type, and operational context [81]. Manufacturing processes dominate PV emissions, typically accounting for 70–90% of total life cycle impacts. Silicon purification, cell production, and module assembly represent the most carbon-intensive phases, with emissions varying significantly based on electricity grid composition in manufacturing regions [82,83,84].

Crystalline silicon technologies generally demonstrate higher manufacturing emissions than thin-film alternatives, though superior efficiency and longer lifespans often result in comparable or lower life cycle emissions per unit of electricity generated [82]. Recent technological improvements, including higher efficiency cells and extended operational lifespans, continue to reduce solar PV’s carbon intensity [83]. Studies indicate potential emissions reductions of 50–70% through manufacturing process optimization and renewable energy integration in production facilities [84,85].

Geographic deployment significantly influences solar PV’s environmental performance. Higher solar irradiation levels directly translate to improved energy yields and lower emissions per kWh generated. Analysis across different global regions demonstrates how local climate conditions, particularly solar radiation and temperature, affect system performance and carbon intensity [86,87,88]. Urban deployment considerations include building integration opportunities and distributed generation benefits, though these must be balanced against potential efficiency losses from suboptimal orientations and shading.

Recycling and end-of-life management represent emerging considerations in solar PV assessment. While current recycling infrastructure remains limited, studies indicate significant potential for materials recovery and emissions reduction through circular economy approaches [82]. Silicon, silver, and aluminum recovery can substantially reduce manufacturing emissions for new modules, though economic viability and technological scalability remain challenges.

Concentrated Solar Power (CSP) technologies exhibit different emissions profiles due to their thermal storage capabilities and alternative materials requirements [89,90]. While manufacturing emissions may be higher due to mirrors, receivers, and thermal storage systems, CSP’s ability to provide dispatchable renewable energy offers system-level benefits that can offset higher embodied emissions [91]. In addition, recent LCA studies on combined PV-and-storage systems indicate that such configurations can reduce the average carbon intensity per kilowatt-hour of delivered electricity [92,93]. However, limited deployment and higher costs have restricted comprehensive LCAs of CSP technologies.

Behavioral responses to solar PV adoption present unexpected challenges for emissions reduction. Studies in Australia revealed a 15% increase in electricity consumption following PV installation, indicating rebound effects that partially offset carbon benefits [94]. Similar patterns observed in Phoenix and San Diego suggest that emissions impacts may vary geographically based on local electricity grids and consumer behavior patterns.

4.4. Biomass Power

Biomass energy exhibits the widest variation in life cycle carbon footprints among renewable technologies, ranging from carbon-negative values (−1550 g CO2e/kWh) in ecosystem restoration scenarios to net-positive emissions exceeding fossil fuel alternatives (+1000 g CO2e/kWh) under unfavorable land use conditions [95,96]. This extraordinary variation reflects fundamental uncertainties about biomass carbon accounting and land use change impacts.

Feedstock selection critically determines biomass energy’s environmental performance. Agricultural residues and organic wastes generally yield lower footprints than dedicated energy crops, as they avoid land use change and utilize materials that would otherwise release carbon through decay [97]. Comparative assessments in the United States show that biodiesel production pathways can achieve favorable GHG balances, while wood-based bioenergy often leads to incremental carbon emissions due to forestry expansion and processing energy demand [97].

Land use change represents the most significant uncertainty in biomass assessment. Converting forests to energy crops or collecting forest residues can generate substantial carbon emissions that may require decades to offset through biomass utilization [98]. Carbon payback times vary considerably based on previous land use, biomass type, and conversion efficiency. Studies indicate payback periods ranging from 2 to 3 years for agricultural residues to several decades for forest-derived biomass [99].

Methodological approaches to biomass carbon accounting remain contentious. Some studies treat biomass as carbon-neutral based on regrowth assumptions, while others emphasize temporal dynamics and carbon debt considerations [95]. The choice between treating biomass as a commodity, waste, or by-product significantly influences allocation of environmental impacts. Municipal solid waste incineration can achieve nearly carbon-neutral hydrogen production through avoided burden allocation, while dedicated crop production may result in net positive emissions.

Regional variations in biomass sustainability reflect different agricultural practices, land availability, and conversion technologies. Studies in G7 countries found biomass energy production increased ecological footprints through land degradation, resource depletion, and biodiversity impacts [100]. However, biomass grown on marginal lands for ecosystem restoration demonstrated carbon-negative electricity generation (−1130 to −650 g CO2e/kWh) and carbon-neutral heat production [95].

Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) represents a potential pathway for negative emissions, though LCAs reveal significant variability [101,102,103]. Landscape-scale studies report CO2 uptake ranging from −324 to −1727 g CO2e/kWh of electricity, depending on biomass accounting methodologies [95]. However, low energy conversion efficiency and potential land use conflicts limit BECCS scalability and effectiveness [104].

The integration of biomass energy with other renewable technologies offers potential synergies for emissions reduction. Co-firing biomass with coal can reduce overall power plant emissions while utilizing existing infrastructure. However, operational challenges including ash deposition, fouling, and corrosion can reduce system efficiency and increase maintenance requirements [105]. These technical limitations highlight the need for continued research into biomass utilization technologies and their environmental implications.

Sustainability assessment frameworks for biomass energy must address multiple dimensions beyond carbon emissions, including biodiversity impacts, water consumption, air quality effects, and socioeconomic considerations. The complexity of these interactions necessitates comprehensive approaches that consider regional contexts, temporal dynamics, and system-level effects. Future research should focus on developing standardized methodologies for biomass assessment that account for land use change uncertainties and provide clear guidance for sustainable biomass utilization pathways.

5. Nuclear and Emerging Technologies

The transition toward low-carbon power systems necessitates a comprehensive understanding of alternative generation technologies beyond conventional renewables. Nuclear power and emerging technologies such as geothermal and ocean energy represent critical components of the future energy portfolio, each presenting unique life cycle carbon footprint characteristics and assessment challenges. While these technologies offer substantial low-carbon potential, their environmental impacts extend beyond operational emissions to encompass complex upstream and downstream processes that require sophisticated analytical frameworks [106,107]. The assessment of these technologies reveals significant methodological gaps and data limitations that constrain accurate environmental impact quantification, particularly for emerging ocean energy systems where deployment remains limited [108,109].

5.1. Nuclear Power

Nuclear power presents one of the most contentious yet potentially transformative low-carbon generation options, with LCAs revealing both significant environmental benefits and complex methodological challenges. Recent comprehensive analyses demonstrate that nuclear energy exhibits GHG emissions ranging from 8 to 64 g CO2e/kWh across different assessment methodologies. Notably, a 2024 French LCA study reports a substantially lower value of only 3.7 g CO2e/kWh for nuclear power, underscoring both the technological maturity of France’s nuclear fleet and the sensitivity of nuclear LCA results [110]. Also, consolidated reviews show that process-based, input-output (IO), and hybrid LCA approaches yielding averages of 16.97, 24.89, and 27.63 g CO2e/kWh respectively [106]. These values substantially exceed previously accepted ranges of 5–22 g CO2e/kWh established by the UK’s Committee on Climate Change and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) median of 12 g CO2e/kWh, highlighting significant uncertainty in nuclear LCA methodologies and the influence of assessment boundaries on results.

The life cycle carbon footprint of nuclear power is predominantly influenced by front-end fuel cycle processes, particularly uranium enrichment methods and the energy mix employed during construction and fuel processing [111,112]. Under worst-case scenarios considering no technological improvements through 2050, maximum lifecycle emission intensity could reach 110 g CO2e/kWh [113,114], emphasizing the critical importance of background energy systems in determining nuclear’s environmental performance [115,116]. This sensitivity to upstream processes distinguishes nuclear from renewable technologies where operational emissions dominate environmental impacts.

Nuclear-based hydrogen production pathways demonstrate the technology’s potential for deep decarbonization across multiple sectors. LCAs of five nuclear hydrogen production methods reveal significant variations in environmental performance, with high-temperature electrolysis achieving the lowest impacts at 0.4768 kg CO2e/kg H2, while thermochemical cycles range from 1.201 to 1.346 kg CO2e/kg H2 [117]. Comparative analysis with steam methane reforming (SMR) demonstrates nuclear hydrogen’s substantial environmental advantages, with nuclear-based electrolysis producing 70% fewer CO2 emissions than conventional SMR processes, which generate approximately 9 kg CO2e/kg H2 [118]. These findings underscore nuclear energy’s potential role in industrial decarbonization and energy storage applications.

Harmonized life cycle indicators reveal that nuclear hydrogen exhibits consistently low carbon footprints and acidification impacts compared to fossil alternatives, though non-renewable energy footprints remain unfavorable due to uranium mining and processing requirements [119]. The development of small modular reactors represents a critical knowledge gap, with insufficient detailed carbon footprint data available for these emerging nuclear technologies despite their potential for enhanced safety and deployment flexibility.

Waste management and decommissioning represent significant environmental hotspots in nuclear life cycles, though quantitative data remains limited. The long-term nature of nuclear waste storage and the complexity of decommissioning processes create substantial uncertainty in LCAs, particularly regarding end-of-life emissions and resource requirements. Recent analysis of anthropogenic uranium imprints in Baltic Sea sediments demonstrates the long-term environmental persistence of nuclear activities, with documented releases of reactor-derived 236U highlighting the importance of comprehensive environmental monitoring throughout nuclear facility lifecycles [120].

The role of nuclear power in achieving carbon neutrality goals varies significantly across national contexts. In South Korea, nuclear phase-out policies could necessitate increased reliance on LNG, potentially compromising CO2 emission reduction targets and requiring careful evaluation of alternative low-carbon pathways [121]. Conversely, analysis of Indonesia’s energy transition suggests nuclear power plants become essential after hydropower capacity maximization, with nuclear deployment by 2030 required to achieve significant emission reductions under carbon pricing scenarios [122].

5.2. Geothermal Power

Geothermal power provides a stable, low-carbon source of baseload electricity, yet its life cycle carbon footprint varies considerably depending on geological conditions, technology type, and system boundaries. Recent LCA syntheses place the GHG intensity of geothermal electricity between 6 and 38 g CO2e/kWh, depending on plant design, resource chemistry, and regional energy mix [123]. A comprehensive NREL meta-analysis further disaggregated these values by technology, reporting median emissions of 32.0, 47.0, and 11.3 g CO2e/kWh for enhanced geothermal systems (EGS), flash, and binary cycle plants, respectively [124]. These results reaffirm the strong influence of site characteristics and technological configuration on life cycle outcomes.

Upstream phases—particularly drilling, well construction, and plant installation—are dominant contributors to embodied emissions. Recent LCAs have highlighted that the environmental profile of geothermal systems is highly sensitive to drilling depth and material requirements, especially in EGS applications [125]. A 2024 study on CO2-based EGS configurations in Poland demonstrated that substituting conventional working fluids with supercritical CO2 can lower certain operation-phase emissions, though additional energy inputs for compression partly offset these gains [126]. For conventional organic Rankine cycle ORC-based binary plants, measured footprints such as those at Germany’s Molasse Basin typically range from 15 to 24 g CO2e/kWh, with construction and component manufacturing accounting for most impacts [127,128,129].

In regions with high-gas geothermal fluids, non-condensable gas (NCG) release—chiefly CO2 and H2S—can substantially elevate total emissions [130]. The World Bank reported that certain flash systems in Tuscany and western Turkey exhibit direct emissions of several hundred g CO2e/kWh, primarily due to in situ CO2 venting from deep reservoirs [131]. Consequently, the geochemical composition of the resource and the reinjection strategy are critical determinants of a project’s long-term climate performance.

From a methodological perspective, recent reviews highlight that geothermal LCA results remain highly variable due to differences in system boundaries, data quality, and assumptions regarding reservoir emissions and reinjection efficiency. These methodological inconsistencies partly explain the wide range of reported results and underscore the importance of adopting transparent, site-specific assessment frameworks rather than uniform global averages [125,132].

Despite these variations, geothermal power remains one of the lowest-emitting dispatchable energy sources. Ongoing improvements in drilling efficiency, well design, and fluid management—combined with CO2 reinjection and hybrid systems coupling geothermal with solar or storage—can further reduce life cycle emissions [133,134,135]. Achieving consistent methodological standards across regions will be essential to fully realize geothermal energy’s potential contribution to deep decarbonization.

5.3. Ocean Energy (Tidal, Wave, OTEC)

Ocean energy technologies represent the most nascent category of renewable generation, with extremely limited LCA data available despite growing interest in wave, tidal, and ocean thermal energy conversion systems [136,137]. The scarcity of comprehensive LCA studies reflects both the early stage of technology development and the complexity of assessing environmental impacts in marine environments [109]. Available assessments reveal significant variations in carbon footprints across different ocean energy converter types, with offshore wave energy converters reporting 33.8–64 g CO2 eq/kWh, oscillating water column systems at 86 g CO2 eq/kWh, and attenuators and point absorbers ranging from 43.7 to 104.5 g CO2 eq/kWh [108].

The life cycle environmental impacts of ocean energy systems are dominated by raw material extraction and manufacturing phases, with structural components and foundations accounting for the majority of environmental burdens [136]. Analysis of wave energy conversion systems demonstrates that raw material extraction contributes 92.5% of fossil fuel depletion impacts and 87.8% of GWP, primarily due to steel procurement and associated pig iron production and coal-fired power generation [138,139]. This concentration of impacts in upstream processes mirrors patterns observed in other renewable technologies but presents unique challenges for ocean energy due to the harsh marine operating environment requiring robust materials and structures [140].

Ocean liming for carbon dioxide removal represents an emerging application of ocean-based technologies with complex environmental implications. LCA of ocean liming processes identifies limestone calcination as the primary environmental hotspot, with significant CO2 emissions during capture and storage phases [107,141]. However, optimized systems using clean and energy-efficient kilns can achieve negative carbon footprints of −1031 kgCO2eq per ton of lime, demonstrating potential for net carbon removal when properly implemented [107].

Significant research gaps persist, particularly for small-scale and low-energy marine systems. Most current studies focus on high-energy offshore environments, leaving nearshore and hybrid configurations underexplored [108]. Integration with other offshore industries—such as wind or aquaculture—may reduce material intensity through shared infrastructure, though methodological frameworks to evaluate these synergies remain underdeveloped.

Future progress requires the establishment of standardized marine LCA protocols and the incorporation of real-world monitoring data from demonstration projects. Developing harmonized, multi-criteria assessment methods tailored to marine energy systems—similar to geothermal initiatives under the GEOENVI framework—will be essential to improve the reliability and comparability of environmental evaluations as ocean energy moves toward commercial maturity.

6. Cross-Technology Comparisons

The life cycle intensities reported in Section 3, Section 4 and Section 5 derive from studies that differ in methodological scope, background datasets, and system boundaries. For comparability, all values are expressed in g CO2e/kWh, converted from original units when data permit. While this does not fully eliminate heterogeneity, it allows a coherent, technology-spanning interpretation of recent LCA evidence. The analysis in this section therefore emphasizes robust ordering and representative ranges rather than precise global averages.

6.1. Life Cycle GHG Intensities: The Big Picture

Cross-technology evidence places unabated fossil options at the high end, with coal typically spanning concentrations of 751–1095 g CO2e kWh−1 (hereafter in g CO2e kWh−1; widely cited median ~820) [19,20]; natural gas spanning ~330–1400 with an average ~645 (modern NGCC plants generally 430–550) [33,34,35,36,37]; and oil spanning 722–907 (with case evidence around 1080) [52,53]. In contrast, non-biogenic renewables and nuclear cluster are one–two orders lower: hydropower has a range of 0.11–54.7 (median 7.6, mean 12.8) [58]; wind has a range of 7–56, with most modern projects having ~10–15 [58,69,70,71]; utility-scale PV has a range of 18–180 [81,82,83,84,85]; nuclear power has a range of 3.7–64, with method-specific averages of ~16.97 (process), 24.89 (IO), and 27.63 (hybrid) [106,110]; and geothermal power has a range of 6–38 overall, with NREL medians by technology of 11.3 (binary), 32.0 (EGS), and 47.0 (flash) [123,124]. Biomass exhibits the widest spread—from carbon-negative cases to values exceeding fossil benchmarks depending on feedstock and land use dynamics [95,97,98,99,100]. A consolidated summary of these ranges and central estimates is shown in Table 1. These cross-technology contrasts remain robust under alternative system boundaries, though absolute values are sensitive to selected assumptions.

Table 1.

Technical factor comparison table.

Across technologies, the underlying evidence base proved too heterogeneous to support a formal meta-analysis with statistically consistent weighted means or interquartile ranges. Some of the most widely cited values—particularly for hydropower, nuclear, and some geothermal technologies—originate from earlier meta-reviews or differ substantially in system boundaries, GWP factors, and capacity-factor assumptions, making recomputation into harmonized distributions neither mathematically valid nor methodologically defensible. For these reasons, this review reports representative central tendencies and ranges from high-quality LCAs (2015–2025) while refraining from synthetic aggregation that would imply unwarranted precision.

In light of this dispersion, a simple decision-oriented recommendation framework helps guide the selection of representative values. Under conservative assumptions—appropriate for screening analyses, regulatory thresholds, or upper-bound risk appraisal—upper-range values for each technology are more appropriate (e.g., ~900 g CO2e/kWh for coal; ~650–800 for natural gas depending on methane control; ~40–60 for utility-scale PV; ~20–40 for nuclear, geothermal, and offshore wind; and ~20–45 for hydropower in warm basins). Under optimistic assumptions, suitable for best-practice benchmarking and forward-looking decarbonization scenarios, lower-range values better represent high efficiency, decarbonized supply chains, and strict upstream control (e.g., ~750 g for modern coal fleets; 430–550 for NGCC; 25–40 for PV with low-carbon manufacturing; 10–20 for wind, nuclear, and binary geothermal; and <10 g CO2e/kWh for high-power-density hydropower).

6.2. Dominant Drivers of Variability

Cross-technology dispersion is shaped first by upstream supply chains. For coal and gas, coal-mine methane, fuel processing, and long-distance transport or LNG can add more than 100 g CO2e kWh−1; methane leakage alone can shift gas from firmly below coal into overlap with low-efficiency coal plants [33,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. Oil’s extraction, refining, and transport typically contribute a further 50–120 g CO2e kWh−1 [53]. For PV and wind, materials and manufacturing dominate, and the carbon intensity of the manufacturing grid is a first-order determinant of embodied emissions [69,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85].

Technology design and operating profile then determine realized performance: higher thermal efficiencies (e.g., ultra-supercritical coal; combined-cycle gas) reduce intensities, whereas cycling, start-ups, and part-load operation raise per-MWh emissions relative to steady baseload [32,45,46]. Offshore wind often begins with higher embodied burdens but can offset them via superior capacity factors [70,77,78]. Hydro variability hinges on reservoir greenhouse gas fluxes and power density, with siting and basin characteristics driving the widest spreads [58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. Geothermal outliers are linked to deep drilling and materials intensity as well as NCG release where reinjection is incomplete [124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131]. Finally, regional context—resource quality, logistics, and background grid mixes during construction and manufacturing—systematically shifts outcomes across all technologies [77,82,83,84,85,124,125,126,127,128,129].

6.3. Technology-Specific Abatement Levers

Mitigation opportunities emerge along both supply chains and plant design. Efficiency upgrades in coal fleets (subcritical → ultra-supercritical) typically cut ~100–250 g CO2e kWh−1, while NGCC retains a structural advantage over open-cycle units at high-capacity factors [19,20,21,33,34,35,36,37,45,46]. Tighter methane control—including leak detection, green completions, and super-emitter targeting—materially lowers gas life cycle emissions [38,39,40,41,42].

CCS at ~90% capture can reduce stack emissions by 60–85%, accounting for 8–14 percentage-point energy penalties [21,27,28,29,30,31,50]. Coal + CCS (~147–469 g CO2e kWh−1) undercuts unabated coal but remains above most renewables; NGCC + CCS can approach low-carbon ranges where upstream methane is tightly managed [19,47,48,49,50,51].

For renewables, careful reservoir siting and higher power density limit hydropower variability [58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65]; decarbonizing manufacturing electricity and increasing recycled content drive structural reductions for PV and wind [82,83,84,85]; and complete reinjection of NCG, combined with prudent site selection, keeps geothermal toward the lower end [124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131]. Hybrid PV-plus-storage systems have also been shown to reduce average life cycle emissions per delivered kWh [92,93]. Biomass and BECCS can deliver net removals when residues or wastes are used and LUC carbon debt is avoided, though results remain context- and method-dependent [95,101,102,103,104].

6.4. System-Level Interactions and Portfolio Insights

Rising VRE shares increase cycling of coal and gas, elevating per-MWh emissions; NGCC performs better than coal at part-load yet still incurs ~10–25% increases at low loads [32,45,46]. Storage reduces curtailment but adds embodied impacts and replacement cycles, so system LCAs must include storage manufacturing and lifetimes [79,80]. Superior resources (offshore wind, high-irradiance PV) often offset higher embodied infrastructure via higher capacity factors, but marine foundations and long transmission must be fully credited in comparisons [70,77,78]. Long-lived coal/oil assets risk carbon lock-in, particularly at low-capacity factors where specific intensities worsen; orderly phase-out paired with firm low-carbon capacity (nuclear, geothermal, and selectively CCS) limits system footprints [53,54,55,56,121,122].

6.5. Cross-Study Harmonization Insights

Although the reviewed LCAs differ in regional scope, boundary choices, and methodological assumptions, several consistent cross-technology patterns emerge when results are interpreted through an interpretive harmonized lens. Much of the dispersion in reported intensities is attributable to a limited set of methodological drivers—such as upstream methane accounting, choice of GWP factors, and inclusion or exclusion of construction and land use processes—rather than to inherent performance differences among technologies. Recognizing these drivers helps avoid over-interpreting outliers and enables more comparable interpretation across studies.

Additionally, several studies show differences stemming from the use of different background LCI databases—such as ecoinvent, GREET, and national inventories—which diverge in process coverage, regionalization, and upstream fuel pathway assumptions. These database-level inconsistencies further underscore the need for an interpretive rather than numerical harmonization approach. Although this review does not provide a detailed comparison of database differences, it recognizes that systematically assessing these structural inconsistencies is an important direction for future research.

The structural composition of life cycle emissions remains stable across the literature even where numerical values differ. Fossil technologies are dominated by upstream fuel-cycle emissions, wind and PV by material production and manufacturing electricity mixes, hydropower by reservoir processes and power density, and nuclear and geothermal by construction and drilling intensity. These recurring patterns allow cross-technology comparisons to focus on underlying drivers rather than absolute numbers.

6.6. Implications for Decarbonization Strategy

Replacing unabated coal and oil with VRE (wind/PV) complemented by firm low-carbon capacity (nuclear, geothermal, NGCC with stringent methane control and, where feasible, CCS) delivers the largest near-term life cycle gains [19,33,47,58,70,81,106,110,119]. Upstream methane/CMM abatement is a cross-cutting priority [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. Bioenergy should be context-first—favor residues/wastes, avoid LUC debt, and deploy BECCS only under robust sustainability constraints [95,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104]. Decarbonizing PV/wind/nuclear supply chains and increasing recycled content lock in structural reductions [69,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,106,110,119]. Portfolio planning must internalize cycling, storage turnover, and transmission build-out—which can introduce additional network losses and therefore requires attention to grid efficiency—to avoid underestimation of system footprints [32,45,46,70,77,78,79,80].

Despite methodological dispersion, the ordering is stable, unabated coal > oil ≈ high-leakage gas ≫ nuclear/geo/hydro/wind/PV (context-dependent), with biomass spanning negative to fossil-like outcomes. Portfolios pairing rapid VRE growth with clean manufacturing, stringent upstream methane control, and firm low-carbon capacity minimize life cycle emissions while preserving reliability [19,33,47,58,70,81,106,110,119].

7. Policy Perspectives

7.1. Global and National Policy Landscape

Global electricity decarbonization is now shaped by an expanding web of trade, disclosure, and product-level carbon regulations that embed life cycle principles into compliance and market access. The Paris Agreement and IPCC AR6 have established the scientific and political basis for this transition, promoting full-chain transparency of emissions and consistent methodologies for embodied carbon accounting [142,143].

At the international level, the European Union (EU) has taken the lead in linking trade, product thresholds, and corporate disclosure through a “three-pillar” framework: the CBAM, the Battery Regulation, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) [144,145,146,147]. Together, these instruments require importers and manufacturers to disclose product-level life cycle carbon footprints, including electricity-related emissions, verified by third-party auditors [144]. The United States follows a similar path via California’s Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act (SB 253) and the SEC Climate Disclosure Rule [148,149,150], mandating Scope 2 electricity emissions reporting. The United Kingdom, Japan, Korea, Australia, and Canada integrate electricity emissions into their emissions trading scheme ETS frameworks and product carbon labeling systems [151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159].

These measures demonstrate a clear global trend: international regulation rarely isolates “ECFs” as a standalone category but rather embeds them across product carbon footprints, Scope 2 disclosure, and border mechanisms, ensuring that electricity intensity, source, and verification outcomes are central to compliance and trade access. Representative international policies are summarized in Table 2, which highlights how major jurisdictions have incorporated electricity-related carbon accounting requirements into climate, trade, and disclosure frameworks [144,145,146,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159].

Table 2.

Representative International Regulations Related to ECFs.

At the national level, China has transitioned from top-level planning to systematic implementation of carbon-footprint management. The 2021 Carbon Peaking Action Plan and 2023 Opinions on Establishing a Product Carbon Footprint Management System [160,161,162] proposed developing accounting rules, background databases, and application scenarios. The 2024 Implementation Plan for Establishing a Carbon Footprint Management System—issued jointly by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE), National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), and State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR)—explicitly prioritized electricity among the first products for which footprint standards will be formulated [163]. With the support and guidance of the central authorities [164,165], subsequent guidance from Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) and MEE further refined standard-setting procedures for industrial products, aligning Chinese approaches with ISO 14067 and international LCA norms [166,167]. Table 3 summarizes key Chinese policy documents, showing the progression from strategic planning toward standardized, verifiable carbon-footprint governance in which electricity plays a central role [160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167].

Table 3.

Major Chinese Policy Documents Related to Carbon Footprint Governance.

7.2. Integrating LCA Evidence into Policy and Market Instruments

Effective low-carbon governance requires translating LCA evidence into concrete policy and market tools. Traditional metrics limited to operational emissions often underestimate upstream methane leakage, materials production, and infrastructure burdens. Integrating LCA findings enables more targeted and efficient interventions along electricity supply chains.

First, carbon pricing mechanisms—including emission trading systems and carbon taxes—can better reflect technology-specific life cycle intensities, rewarding genuinely low-carbon portfolios such as renewables, nuclear, and geothermal, while accounting for upstream variability in fossil pathways [168,169]. Similarly, renewable energy incentives (e.g., green certificates, contracts-for-difference) should adopt life cycle benchmarks rather than direct-emission thresholds.

Second, standardization and data alignment are essential. Harmonizing methods with ISO 14067, GHG Protocol Scope 2 Guidance, and IPCC AR6 factors would enhance international comparability and support cross-border mechanisms such as CBAM [143,170,171]. Establishing open, AR6-aligned databases for grid-specific life cycle emission factors can strengthen both national carbon inventories and corporate disclosure frameworks [19].

Third, integrating life cycle indicators into green finance, procurement, and power-system planning ensures that investments and policies consider embedded carbon and resource impacts. Coupling LCA data with digital MRV systems will further improve transparency, reduce uncertainty, and connect scientific evidence to decision-making [172].

8. Conclusions

This review summarizes a consistent cross-technology ordering of life cycle GHG intensities. Unabated coal and oil occupy the upper range; natural gas is lower but highly contingent on upstream methane control and LNG logistics; nuclear, geothermal, hydropower, wind, and utility-scale PV cluster one–two orders lower. Biomass spans carbon-negative to fossil-like outcomes depending on feedstock and land use dynamics. Variability reflects the combined influence of upstream supply chains (mining, methane/CMM for fossils; materials and manufacturing for wind and PV), siting conditions (reservoir fluxes and power density for hydropower; drilling depth and NCG for geothermal), and operational dynamics (cycling, start-up, and part-load behavior). Plant efficiency remains critical within each technology, yet system-wide and upstream factors dominate cross-technology differences in life cycle intensity.

The significance is twofold. First, the findings suggest that rapid expansion of variable renewables—wind and PV—combined with firm low-carbon capacity—nuclear and geothermal—and with well-sited hydropower where reservoir emissions are controlled delivers the largest system-level reductions in life cycle emissions without compromising reliability. Second, they show that decarbonizing manufacturing supply chains (cleaner electricity and higher recycled content for wind/PV components and hydropower civil works) and tightening upstream emission control (methane/CMM management, prudent hydro siting, geothermal reinjection) may deliver structural gains that conventional operational metrics overlook. Importantly, the results also provide a quantitative foundation for emerging regulatory frameworks that now integrate life cycle and Scope-2 accounting—such as the EU CBAM, U.S. and UK disclosure regimes, and China’s developing carbon-footprint standards—highlighting the increasing convergence between scientific assessment and compliance requirements in the electricity sector.

Future research should prioritize (i) standardized, AR6-aligned LCA protocols with explicit treatment of reservoir fluxes, methane super-emitters, and land use change; (ii) measurement-informed methane/CMM inventories and LNG-chain data; (iii) dynamic, scenario-based LCAs that integrate cycling, storage turnover, transmission build-out, and decarbonized manufacturing for wind, PV, and hydropower; (iv) high-resolution regional datasets for geothermal NCG handling and hydro morphology/power density; and (v) robust sustainability criteria for biomass/BECCS focused on residues and wastes.

Bridging life cycle evidence with policy design—through standardized metrics, transparent datasets, and interoperable disclosure systems—will sharpen policy signals, improve comparability across technologies, and steer investment toward the most effective abatement options in the power sector.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/en18246413/s1, Table S1: Search strategy for fossil-fuel-based electricity technologies; Table S2: Search strategy for renewable electricity technologies; Table S3: Search strategy for nuclear, geothermal, ocean energy and policy/governance literature.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W., G.X. and L.G.; methodology, X.W. and G.X.; software, J.T.; validation, G.X., L.G., Y.W. and W.N.; formal analysis, G.X. and X.W.; investigation, X.W., L.G. and J.T.; resources, L.G. and W.N.; data curation, J.T., Y.W. and W.N.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W. and G.X.; writing—review and editing, L.G., J.T., Y.W. and W.N.; visualization, G.X. and J.T.; supervision, G.X.; project administration, G.X.; funding acquisition, G.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Economic and Technical Research Institute of State Grid Jiangsu Electric Power Co., Ltd., project titled “Research on the Impact of Power Carbon Footprint on Low-Carbon Transition of Key Industries in Jiangsu and Grid Enterprises’ Response Strategies”, grant number SGJSJY00GHWT2500072. The APC was funded by the same institute.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this study. All data discussed in this review are drawn from publicly available peer-reviewed publications and official regulatory documents retrieved.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors were employed by the Economic and Technical Research Institute of State Grid Jiangsu Electric Power Co., Ltd. All authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AASB | Australian Accounting Standards Board |

| ACS | American Chemical Society |

| AR6 | Sixth Assessment Report (IPCC) |

| BECCS | Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage |

| CARB | California Air Resources Board |

| CBAM | Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism |

| CCGT | Combined Cycle Gas Turbine |

| CCS | Carbon Capture and Storage |

| CFP | Carbon Footprint |

| CMM | Coal Mine Methane |

| CO | Carbon Monoxide |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| CO2e/CO2e | Carbon Dioxide Equivalent |

| CPC | Communist Party of China (Central Committee) |

| CSDS | Canadian Sustainability Disclosure Standards |

| CSP | Concentrated Solar Power |

| CSRD | Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive |

| CSSB | Canadian Sustainability Standards Board |

| ECF | Electricity Carbon Footprint |

| EEA | European Environment Agency |

| EGS | Enhanced Geothermal Systems |

| EPD | Environmental Product Declaration |

| ESRS | European Sustainability Reporting Standards |

| ETS | Emissions Trading System |

| EU | European Union |

| EU CBAM | European Union Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| GO | Guarantees of Origin |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| GX-ETS | Japan Green Transformation Emissions Trading Scheme |

| ICAP | International Carbon Action Partnership |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| IEEE | Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers |

| IO | Input–Output |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| JEMAI | Japan Environmental Management Association for Industry |

| K-ETS | Korea Emissions Trading System |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LNG | Liquefied Natural Gas |

| LUC | Land Use Change |

| MEE | Ministry of Ecology and Environment (China) |

| MIIT | Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (China) |

| NCG | Non-Condensable Gas |

| NDRC | National Development and Reform Commission (China) |

| NGCC | Natural Gas Combined Cycle |

| NREL | National Renewable Energy Laboratory |

| ORC | Organic Rankine Cycle |

| OTEC | Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion |

| PPA | Power Purchase Agreement |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| RECs | Renewable Energy Certificates |

| SAMR | State Administration for Market Regulation (China) |

| SEC | U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission |

| SMR | Steam Methane Reforming |

| UCG-IGCC | Underground Coal Gasification–Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| UK ETS | United Kingdom Emissions Trading Scheme |

| UNECE | United Nations Economic Commission for Europe |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| US | United States |

| US EPA | U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |

| USA | United States of America |

| USD | United States Dollar |

| VRE | Variable Renewable Energy |

References

- Zhao, M.; Zhou, Y.; Meng, J.; Zheng, H.; Cai, Y.; Shan, Y.; Guan, D.; Yang, Z. Virtual Carbon and Water Flows Embodied in Global Fashion Trade—A Case Study of Denim Products. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 303, 127080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.-P.; Kang, L.-L.; Wang, Y.-J.; Wang, Y.-R.; Wang, Y.-T.; Li, J.-G.; Jiang, L.-Q.; Ji, R.; Chao, S.; Zhang, J.-B.; et al. Magnetic Biochar Catalyst from Reed Straw and Electric Furnace Dust for Biodiesel Production and Life Cycle Assessment. Renew. Energy 2024, 227, 120570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Guan, D. Value Chain Carbon Footprints of Chinese Listed Companies. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zib, L.; Byrne, D.M.; Marston, L.T.; Chini, C.M. Operational Carbon Footprint of the U.S. Water and Wastewater Sector’s Energy Consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.; Ingwersen, W.W.; Jamieson, M.; Hawkins, T.R.; Cashman, S.; Hottle, T.; Carpenter, A.; Richa, K. Derivation and Assessment of Regional Electricity Generation Emission Factors in the USA. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2023, 28, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddik, M.A.B.; Chini, C.M.; Marston, L. Water and Carbon Footprints of Electricity Are Sensitive to Geographical Attribution Methods. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 7533–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Chen, L.; Yang, M.; Msigwa, G.; Farghali, M.; Fawzy, S.; Rooney, D.W.; Yap, P.-S. Cost, Environmental Impact, and Resilience of Renewable Energy under a Changing Climate: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 741–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehl, M.; Arvesen, A.; Humpenöder, F.; Popp, A.; Hertwich, E.G.; Luderer, G. Understanding Future Emissions from Low-Carbon Power Systems by Integration of Life-Cycle Assessment and Integrated Energy Modelling. Nat. Energy 2017, 2, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agwu, O.E.; Ayodele, B.V.; Mustapa, S.I. Sustainability of Natural Gas in Transition to Low-Carbon Economy. In Sustainable Utilization of Natural Gas for Low-Carbon Energy Production: Attaining Low-Carbon Energy Production Through Sustainable Natural Gas Utilization; Ayodele, B.V., Mustapa, S.I., Sarkodie, S.A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 221–232. ISBN 978-981-9762-82-8. [Google Scholar]

- Nugent, D.; Sovacool, B.K. Assessing the Lifecycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Solar PV and Wind Energy: A Critical Meta-Survey. Energy Policy 2014, 65, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Tang, J.; Shan, R.; Li, G.; Rao, P.; Zhang, N. Spatiotemporal Analysis of the Future Carbon Footprint of Solar Electricity in the United States by a Dynamic Life Cycle Assessment. iScience 2023, 26, 106188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, L.; Pfister, S. Hydropower’s Biogenic Carbon Footprint. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Levin, T.; Botterud, A. Evolution of Grid Services for Deep Decarbonization: The Role of Hydropower. Curr. Sustain. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krūmiņš, J.; Kļaviņš, M. Investigating the Potential of Nuclear Energy in Achieving a Carbon-Free Energy Future. Energies 2023, 16, 3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Boulch, D.; Buronfosse, M.; Le Guern, Y.; Duvernois, P.-A.; Payen, N. Meta-Analysis of the Greenhouse Gases Emissions of Nuclear Electricity Generation: Learnings for Process-Based LCA. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2024, 29, 857–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, G.; Violante, A.C.; De Iuliis, S. Environmental Impact of Electricity Generation Technologies: A Comparison between Conventional, Nuclear, and Renewable Technologies. Energies 2023, 16, 7847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Cai, M.; Yu, B.; Qin, S.; Qin, X.; Zhang, J. Life Cycle Assessment of Greenhouse Gas Emissions with Uncertainty Analysis: A Case Study of Asphaltic Pavement in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 411, 137263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Qiao, K.; Hu, C.; Su, P.; Cheng, O.; Yan, N.; Yan, L. Study on Life-Cycle Carbon Emission Factors of Electricity in China. Low-Carbon Technol. 2024, 19, 2287–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNECE. Life Cycle Assessment of Electricity Generation Options; United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, T.; Jin, P.; Song, D.; Chen, B. Tracking the Carbon Footprint of China’s Coal-Fired Power System. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 177, 105964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, J. Transition of China’s Power Sector Consistent with Paris Agreement into 2050: Pathways and Challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 132, 110102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, M.; Heath, G.A.; O’Donoughue, P.; Vorum, M. Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Coal-Fired Electricity Generation. J. Ind. Ecol. 2012, 16, S53–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karacan, C.Ö.; Field, R.A.; Olczak, M.; Kasprzak, M.; Ruiz, F.A.; Schwietzke, S. Mitigating Climate Change by Abating Coal Mine Methane: A Critical Review of Status and Opportunities. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2024, 295, 104623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, J. Comparison of Underground Coal Mining Methods Based on Life Cycle Assessment. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 879082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]