1. Introduction

The global transition towards renewable energy sources is driving an urgent demand for large-scale energy storage solutions capable of compensating the intermittency of solar and wind generation. Among the available technologies, Pumped Storage Hydropower (PSH) stands out as the most mature, reliable, and widespread option, with a long history of operation and proven ability to stabilize power systems [

1,

2]. PSH systems rely on the cyclic movement of water between two reservoirs at different elevations: surplus electricity is used to pump water to the upper reservoir during periods of low demand or high renewable production, and this potential energy is later released to generate electricity at times of peak demand. Such systems provide rapid response, long-duration storage, and grid flexibility, making them a cornerstone for supporting higher shares of renewable energy in modern power systems [

3]. Globally, PSH remains the backbone of grid-scale energy storage. According to the IEA Grid-Scale Energy Storage 2024 report, the global installed capacity of PSH reached approximately 179 GW in 2023, out of a total 1416 GW of grid-connected hydropower capacity, accounting for about 96% of worldwide grid-scale electricity storage. In the European Union, hydropower capacity amounts to around 153 GW, of which nearly 47 GW correspond to pumped-storage systems, mostly located in alpine regions. These figures confirm PSH’s role as the most mature and reliable long-duration storage technology, providing essential flexibility and balancing services to support the growing penetration of variable renewable energy sources [

4].

Alongside PSH, Floating Photovoltaic (FPV) systems represent a promising complementary technology. FPV involves the installation of solar modules on floating platforms placed over water surfaces such as reservoirs or lakes. Compared to ground-mounted systems, FPV reduces land occupation, limits water evaporation from the reservoir, and benefits from the natural cooling effect of water, which enhances module performance [

5,

6,

7]. When integrated with existing hydropower reservoirs, FPV provides additional synergies in terms of infrastructure, grid connection, and hybrid operation, further improving the sustainability and resilience of energy systems [

8,

9].

In the context of PSH, defining optimal operating strategies is crucial to maximize technical and economic performance while supporting renewable integration. Several optimization approaches have been reported in the literature. Linear Programming has been widely adopted for its computational efficiency and speed, but its linear assumptions limit accuracy in systems where head–flow–power relations are inherently nonlinear [

10]. Nonlinear Programming (NLP) overcomes these limitations by explicitly modeling nonlinear dependencies, providing deterministic and reproducible solutions well suited to PSH applications [

5,

11,

12]. Alternative heuristic methods, including genetic algorithms, have also shown promise in exploring large and complex optimization landscapes, though their lack of guarantees for global optimality reduces their applicability when precise scheduling is required [

13,

14]. Dynamic Programming has been widely applied to sequential reservoir optimization problems, offering rigorous coordination among multiple storage units. However, recent studies highlight that its computational complexity and scalability issues limit its applicability to continuous, large-scale systems such as those considered here [

15,

16]. Machine Learning (ML) techniques are increasingly deployed for inflow forecasting, predictive control, and market price prediction, improving the quality of real-time decisions; however, ML methods are less suited to directly solving the full-scale scheduling optimization problems [

17]. In contrast, NLP has been successfully applied in many studies of PSH operation [

12,

18,

19], demonstrating a good balance between model fidelity and computational tractability in capturing the nonlinear operational dynamics of pumped storage systems.

Although both PSH and FPV have been extensively studied as stand-alone technologies, the literature still lacks comprehensive analyses of their integration in real-world contexts, particularly in alpine regions where hydropower infrastructures are widespread and water availability is a pressing issue. Existing research has mainly focused on economic evaluations, with limited consideration of multi-objective approaches that jointly assess profitability, water availability, and environmental impacts [

20,

21]. This paper addresses this gap by analyzing the transformation of an existing hydropower facility in Trentino, Northern Italy, into a hybrid PSH–FPV system. The study develops a nonlinear optimization framework to evaluate different operational scenarios, aiming to maximize economic revenues while simultaneously accounting for water management and emission reduction objectives.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents the methodology, including the description of the input data, the scenario design, and the optimization model employed, with particular attention to the formulation of variables, objective functions, and constraints, and the modeling assumptions and the representation of FPV systems. It also includes model verification and robustness assessment to confirm the internal consistency of the optimization framework and the stability of its results under varying assumptions.

Section 3 introduces the metrics used to evaluate economic, environmental, and water-related impacts.

Section 4 reports the results of the scenario analysis, highlighting the performance of the baseline hydropower system and the improvements achieved through pumped storage and FPV integration.

Section 5 discusses the implications of these findings and draws the main conclusions of the study.

2. Materials and Methods

This study proposes a hypothetical upgrade of a real hydropower facility located in Trentino, Northern Italy, by introducing Pumped Storage Hydropower (PSH) operations and Floating Photovoltaic (FPV) systems. While the baseline hydropower plant, its catchment hydrology, and historical operational data are derived from real facilities, the PSH lower reservoir, pumping infrastructure, and FPV installations considered in this analysis represent hypothetical configurations that are not currently in operation. This section outlines the methodology adopted to evaluate the economic and environmental implications of this transition. It describes the model structure, input datasets, and scenario-based analysis used to quantify the performance of the proposed hybrid system.

2.1. Input Data

Input data are taken from the case-study hydropower facility, forming the basis for the evaluation of the proposed PSH–FPV hybrid system. In order to characterize the hydraulic potential of the scheme, the main parameters of the machine groups and the upper reservoir, such as design discharges, efficiency values, storage capacity, and elevation limits, were provided directly by the plant operator and constitute the reference framework for the present study.

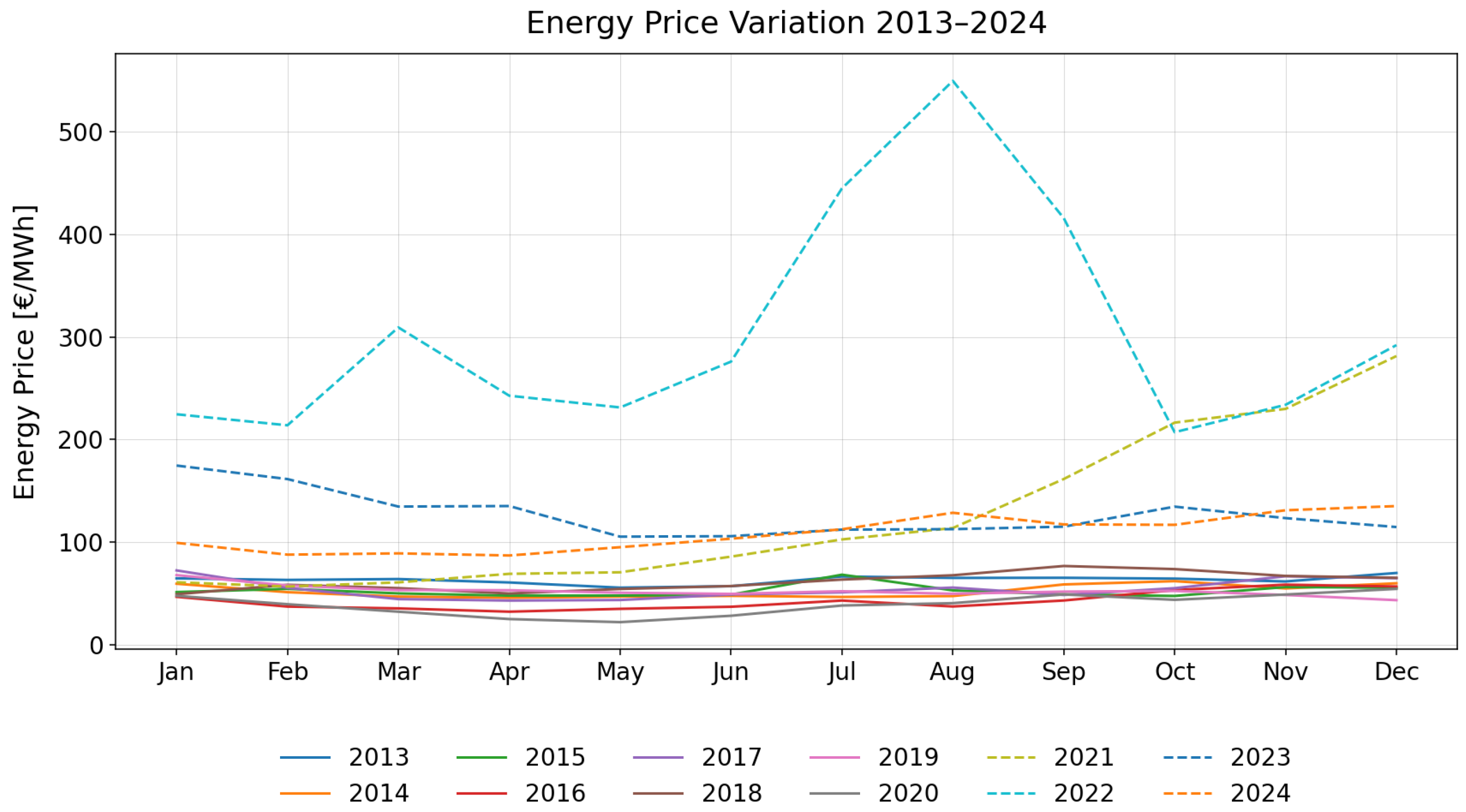

The analysis focuses on the years 2013 and 2014, selected within the decade 2010–2020. This period was considered representative of stable energy market conditions, prior to the significant price volatility observed after 2020 (

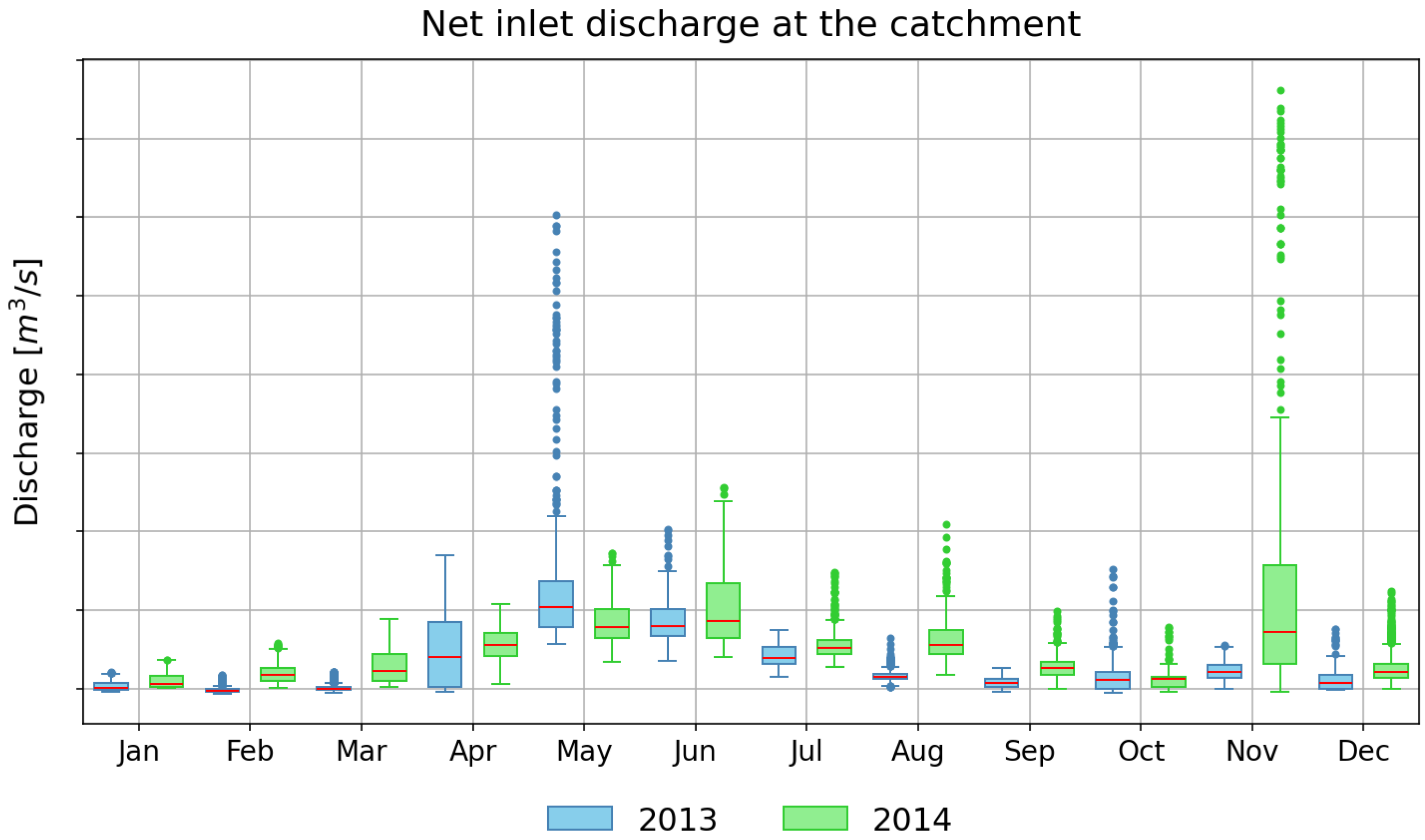

Figure A1). Within this timeframe, 2013 and 2014 were chosen as the two consecutive years exhibiting the largest contrast in annual precipitation, corresponding, respectively, to a wet and a dry hydrological regime. This combination allows the joint assessment of system performance under variable inflow patterns and market conditions. Hydrological data related to the catchment and the reservoir was also collected from the operator and complemented with data from the regional monitoring service. These include the inflow discharge, the minimum environmental flow, and precipitation records from the meteorological station located near the reservoir. The year 2013 is representative of a wet hydrological regime, with abundant precipitation especially during spring, whereas 2014 is characterized by significantly lower rainfall, making it a dry year. This contrast enables an assessment of the system’s response under different inflow distributions and highlights the influence of precipitation and snowmelt dynamics on the available discharge.

Figure 1 illustrates the monthly distribution of the net inlet discharge to the reservoir during 2013 and 2014. The visual analysis of this box plot reveals significant seasonal variability: in 2013, the spring and early summer months show high discharge values, due to snowmelt and intense rainfall, while the winter months remain more stable with lower discharges. This behavior is consistent with the characterization of 2013 as a wet year. In contrast, 2014 exhibits a more heterogeneous pattern, with distinct peaks during spring and late autumn, suggesting that although overall precipitation was lower, snowpack release contributed substantially to the observed discharge.

The historical hourly energy prices were retrieved from the Italian Energy Markets [

22]. The histogram (

Figure 2), shows the frequency distribution of prices. It is observable that 2013 had a higher average price of 62.99 € per MWh compared to 52.08 € per MWh in 2014.

2.2. Scenario Analysis

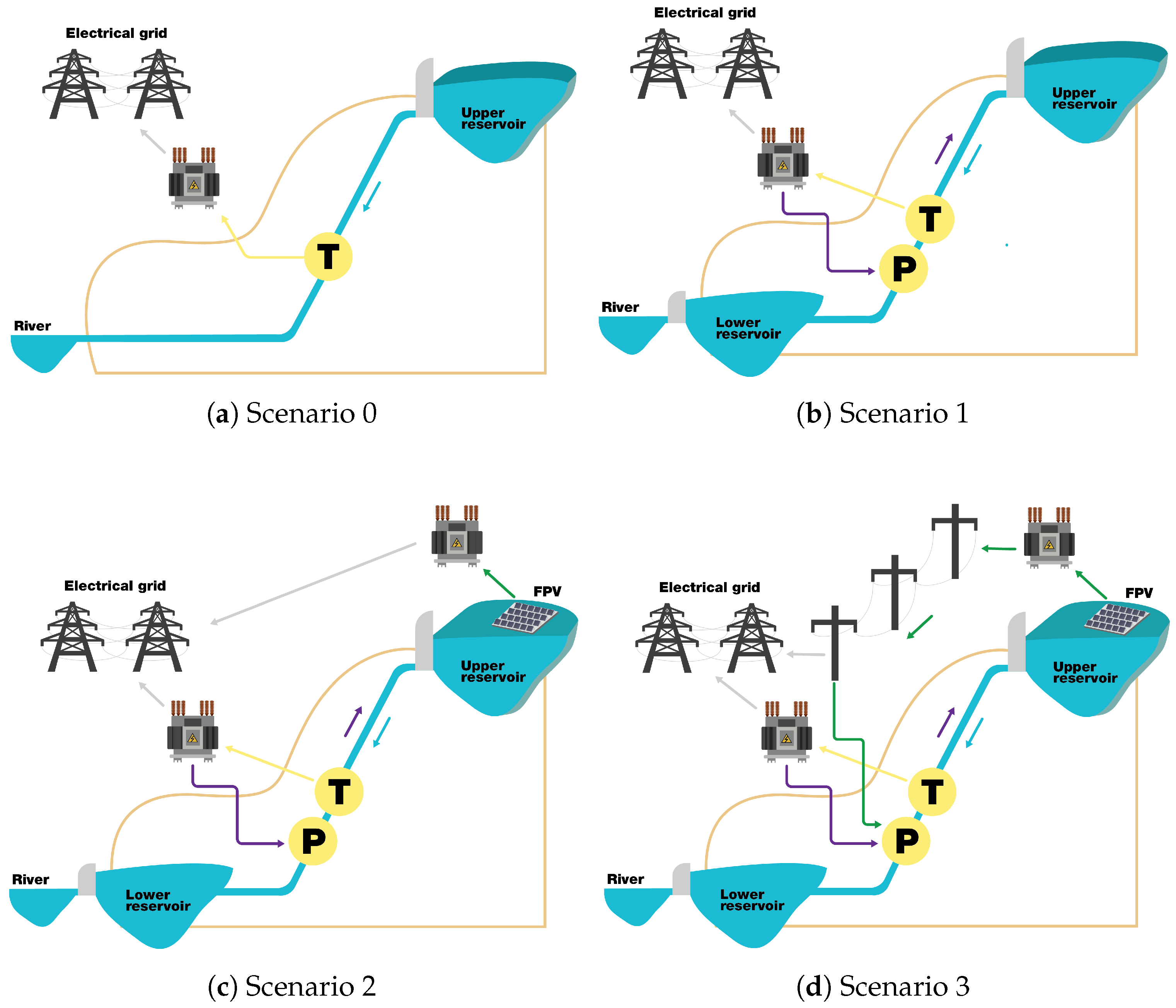

This analysis explores four distinct operational scenarios, as shown in

Figure 3. Each scenario is designed to test different technological configurations and evaluate their impacts on both economic performance and additional objectives, such as water availability and emission reduction.

Scenario 0—Baseline Operation: This scenario establishes the baseline performance of the system, operating under traditional conditions without any pumping mechanism. This scenario reflects the hydropower plant’s ‘as is’ state, focusing solely on the generation capabilities of its existing hydroelectric turbines.

Scenario 1—Pumped Storage Hydropower Plant: In this scenario, the system is augmented with a lower reservoir and an appropriate pumping system. This configuration facilitates reversible operations between the upper and lower reservoirs, optimizing the scheduling of both pumping and turbine operations. This scenario explores the enhanced flexibility of the PSH system to manage peak and off-peak electricity demands, which correspond to higher and lower energy prices, respectively.

Scenario 2—Independent Floating Photovoltaic and Pumped Storage: In this scenario, the addition of an FPV plant atop the reservoir is introduced. This FPV system operates independently, with the energy generated sold directly to the grid. The scenario evaluates the energy production and revenue increase from adding a solar power source to the PSH system outlined in Scenario 1. Importantly, it also allows for investigating potential benefits from a synergistic operation between the FPV and the pumped storage components.

Scenario 3—Integrated FPV and Pumped Storage: This scenario combines the features of pumped storage with the FPV plant, offering the flexibility to use the solar energy generated for either pumping operations or selling it to the grid. This scenario explores the potential for maximizing economic returns and operational efficiency through intelligent energy management and the self-sustaining utilization of renewable energy sources.

2.3. Optimization Model Description

The problem is structured as a Nonlinear Programming (NLP) model, which is particularly suitable for pumped storage hydropower applications since it can explicitly capture the non-linear relationships between water head, flow rate, and power generation [

5,

12]. The model simulates annual plant operation with hourly resolution (

), allowing the optimization of scheduling decisions over a typical management horizon. This methodological choice reflects the ability of NLP to efficiently represent nonlinear operational dynamics while avoiding unnecessary computational complexity, ensuring consistent, precise, and reproducible solutions tailored to PHS systems [

12,

18,

19]. The optimization framework was developed in Python using the open-source library Pyomo, with the SCIP solver employed to address the problem formulation [

23,

24].

2.3.1. Model Variables

The model’s input data, as detailed in

Section 2.1, are passed to the model as parameters, representing the essential data required for optimization. An additional time series treated as a parameter is the geodetic head, obtained by interpolating the upper reservoir volume, resulting from the optimization, within the storage–elevation curve to determine the corresponding water level (

), and subtracting the elevation of the turbine outlet (

).

The Decision Variables represent the unknowns of the model and, consequently, the investigated solutions, forming the output of the optimization process. The model includes several decision variables:

Turbine discharge () (m3/s): The actual water discharge passing through the turbine for energy production.

Pump discharge () (m3/s): The total water discharge that is pumped from the lower reservoir to the upper one.

FPV pump discharge () (m3/s): The pump discharge powered by FPV energy.

Grid pump discharge () (m3/s): The pump discharge powered by energy from the electrical grid.

FPV energy used for pumping () (MWh): FPV energy allocated to powering the pump discharge .

FPV energy not used for pumping () (MWh): FPV energy that is directly exported to the electrical grid.

The variables represent additional unknowns of the model, but unlike decision variables, they are strictly constrained and dependent on the decision variables. In other words, while decision variables can be freely chosen within their bounds, variables change in response to these choices according to specific model constraints. The model includes several such variables:

Upper reservoir volume () (m3): Active water volume in the upper reservoir at each time step.

Spillway volume () (m3): Water volume that spills from the upper reservoir when it reaches the maximum storage capacity.

Lower reservoir volume () (m3): Water volume in the lower reservoir at each time step.

Outflow volume () (m3): Water volume that outflows from the lower reservoir when it reaches its maximum capacity.

Emissions () (kg CO2): Carbon dioxide emissions related to pump operation.

2.3.2. Objective and Multi-Objective Function

The primary objective of the model is to maximize the yearly revenue. This is achieved by strategically managing the operations of turbines, pumps, and integrated FPV production to optimize financial returns over the annual cycle. The relevant functions for the revenue calculation are reported below, where

(MWh) is the energy generated by turbining.

(MWh) the energy consumed for pumping.

(€) the gross revenue at each time step.

(€/MWh) the hourly cost of energy.

and are the turbine and pump efficiencies, respectively.

To extend the analysis beyond purely economic objectives, two multi-objective formulations were introduced, explicitly valuing water availability and emission reduction. Both cases adopt a linear scalarization approach, which converts the multi-objective problem into a single-objective one by assigning weights to each criterion, ensuring Pareto-optimal solutions [

25]. Normalization is applied to balance objectives with different units.

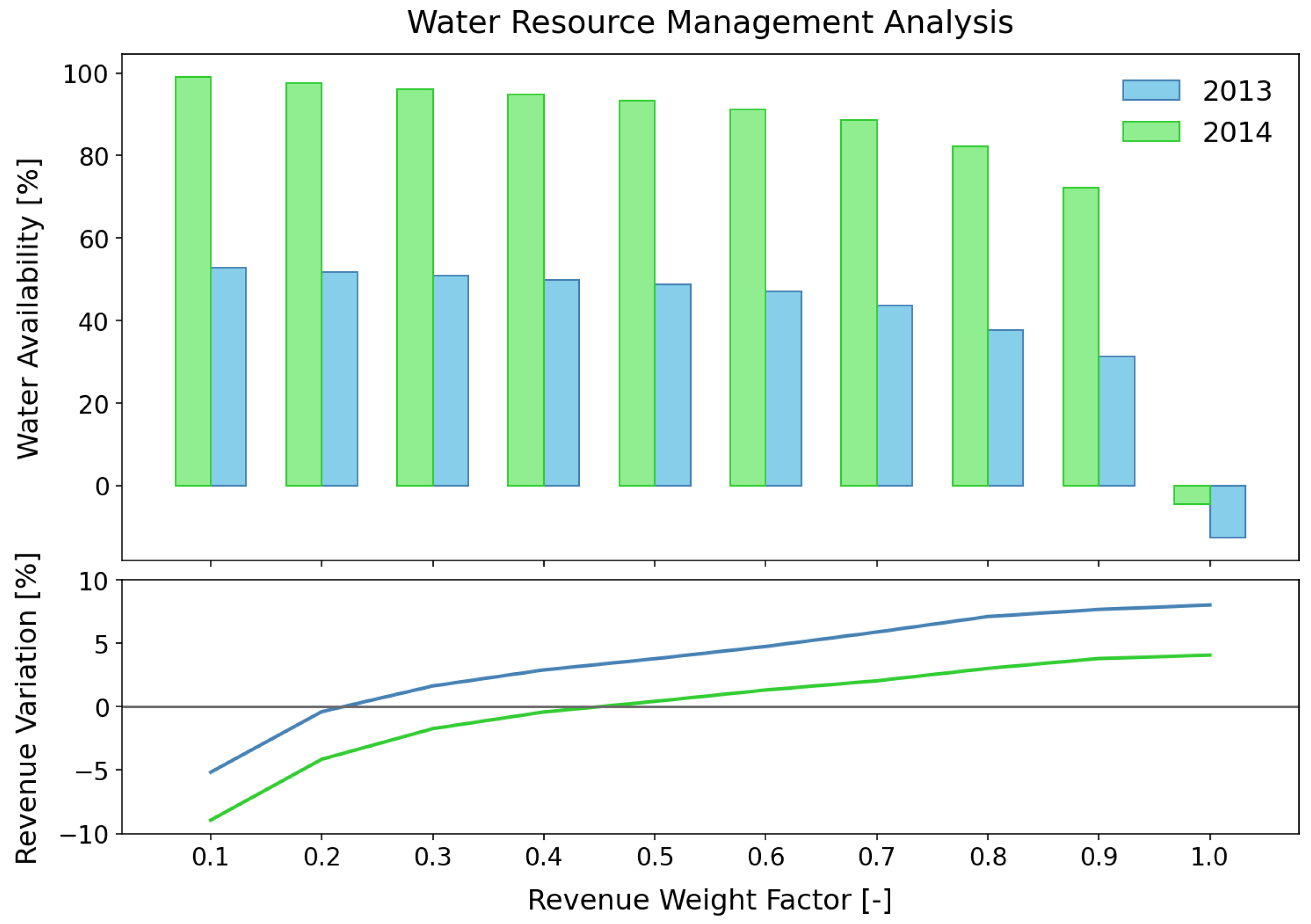

The first multi-objective function evaluates the operational flexibility of PSH in terms of water resource management. It considers the average annual storage in the upper reservoir and quantifies the associated trade-off with revenues:

where

w represents the revenue weighting factor, with a value of one emphasizing revenue maximization and a value of zero fully prioritizing water resource availability.

The second multi-objective function explores the environmental benefits of PSH–FPV integration, focusing on the CO

2 emissions associated with pumping energy consumption. Revenues and emissions are normalized with respect to Scenario 2. Here,

represents the emission factor associated with the national electrical grid, accounting for the energy mix and equal to 235.6

[

26], while

denotes the emission factor for the self-consumption of renewable energy, assumed to be 0

. The corresponding formulation is:

Although the overall objective function is maximized, the approach intentionally minimizes CO2 emissions by inversely relating them to the maximization process.

2.3.3. Model Constraints

The model constraints represent the physical, operational, and regulatory limits within which the system must operate. These constraints are necessary to model the system operation and ensure the feasibility of the solutions generated by the optimization process. The considered constraints are as follows:

Yearly Upper Reservoir Mass Balance: Ensures that the upper reservoir volume at the beginning and end of the year is the same, guaranteeing that annual inflows are fully utilized for production.

Turbine and Pump Operation: Fixes the discharge boundaries to ensure flow through turbines and pumps ranges from zero to their respective maximum capacities. The net head in generation mode is calculated using Equation (

12), considering hydraulic losses of 2% (efficiency,

), thereby reducing the available geodetic head.

The calculation of the net head

in pumping mode is instead reported with Equation (

13).

The calculation of the net head

in pumping mode is reported in Equation (

13). In this formulation, an additional head term

m is included to account for the elevation difference between the lower reservoir water level and the turbine outlet point.

Upper Reservoir Mass Balance: Defines the volume of the upper reservoir at each time step. Additionally, boundary limits are imposed to define the physically admissible water level oscillation.

where

refers to the number of seconds per hour, i.e., 3600.

The spilled volume is limited to non-negative values to prevent the model from erroneously supposing negative values, which would incorrectly represent an additional source of water. Ensuring that is crucial for allowing the system to expel excess water while maintaining the integrity of the reservoir’s boundary limit, reflecting actual system operation.

Lower Reservoir Mass Balance: Define the lower reservoir volume at each time step.

Overflow operation: Define the lower reservoir outflow operation principle. The outflow volume is limited to non-negative values for the same reason as the spilled volume. That also allows the possibility of expressing the constraint as a non-strict inequality instead of an equality that wouldn’t work with a not-full reservoir.

Pump Water Availability: Ensures there is enough water in the lower reservoir to allow pumping with a certain discharge.

Pump Discharge Balance: Ensures that the total pump discharge is equal to its two components.

FPV Energy Balance: Ensures that the total FPV energy is used for pumping or exported to the grid.

FPV Energy-Pump Discharge Coherence: Imposes coherence between the FPV energy used for pumping and the related discharge.

Grid Access Capacity: Imposes the grid access capacity, limited to 190 MW.

CO2 emission: Compute

emissions connected to pump operation.

To reduce computational burden and ensure solver stability, some steps were handled in post-processing. In particular, the effect of reservoir level variation on the geodetic head was accounted for iteratively rather than as a decision variable, given that the maximum fluctuation represents only about 5% of the average head. This approach allows realistic head profiles without compromising model efficiency [

20]. In addition, the priority of FPV self-consumption over grid imports was imposed in post-process to obtain realistic estimates of emissions from pumping operations.

2.4. Modeling of Floating Photovoltaic Systems

The energy performance of FPV systems was evaluated under three representative layouts, air-cooled, water-cooled, and vertical-axis tracking, selected from the literature to capture the influence of cooling mechanisms and the main advantages and limitations of these categories [

7,

27,

28,

29]. Simulations were performed using the Pvlib-Python package [

30], which provides tailored tools for solar position, irradiance modeling, shading, and system performance analysis [

31]. Hourly meteorological data were retrieved from the PVGIS database, which supplies typical meteorological years (2005–2020) following ISO 15927-4 [

32], including solar irradiance components, air temperature, wind speed, and sun position [

33].

For technical specifications, crystalline silicon (c-Si) technology was adopted as it is the most widely used and efficient option [

34]. A representative mono-Si module and a string inverter were selected in line with the recommendations of Ranjbaran et al. [

35], with datasheet values complemented using Pvlib fitting functions [

30]. Tilt and azimuth were defined according to both PVGIS recommendations and FPV structural constraints: 15° tilt for the air-cooled and tracking systems, horizontal layout for the water-cooled system, and 180° azimuth for the fixed configuration [

7,

27]. Panel spacing followed literature values to balance shading and accessibility [

34,

36].

A critical factor for FPV performance is the operating temperature of photovoltaic modules, as it directly affects energy yield [

37]. However, the literature shows no consensus on the actual magnitude of the cooling benefit provided by water surfaces. While some studies report significant reductions in module temperature and corresponding gains in energy yield [

38,

39,

40], others highlight that conventional pontoon-based systems exhibit only modest differences compared to land-based PV [

28,

41]. This variability reflects both the diversity of floating structures and the absence of FPV-specific temperature models in widely used simulation tools, which still rely on formulations originally developed for ground-mounted systems [

39]. As a result, estimating FPV performance requires careful consideration of the underlying assumptions and modeling approaches. In this work, module temperature was modeled considering the limitations of standard approaches such as the Sandia and Faiman models [

39], which underestimate wind effects in FPV systems [

39,

42]. Following Dörenkämper et al. [

40], a simplified method based on a single U-value was applied to account for cooling dynamics in the absence of reliable wind data. Energy production was then simulated in Pvlib, with temperature corrections based on the PVSyst approach and system losses modeled following PVWatts v5 [

43]. Adjusted loss factors are reported in

Appendix B (

Table A5), while shading was calculated explicitly with dedicated Pvlib functions consistent with the system geometry [

44,

45]. Albedo instead was estimated hourly using the model of Dvoracek & Hannabas, which captures its variability with solar altitude [

34,

36,

38,

46].

To evaluate FPV performance, the air-cooled system, based on open “small-footprint” pontoons, was modeled with a heat transfer coefficient of

W/(m

2 K), consistent with field tests in the Netherlands and Singapore [

28]. The water-cooled configuration, inspired by the Ocean Sun membrane concept, was assigned a conservative value of

W/(m

2 K), reflecting the upper range of experimental and modeling results [

28,

40,

47]. Finally, for the vertical-axis tracking system, thermal assumptions similar to the air-cooled case were applied, given its comparable open structure design. The water gain, defined as the percentage increase in specific energy output, was estimated by modeling a baseline ground-mounted PV system using the Faiman temperature model, the most widely used and recommended by IEC 61853-2 [

39,

48,

49].

2.5. Assumptions

Given the limited availability of data for the specific test case, the study relies on several assumptions to enable a consistent analysis of the potential transition from a conventional hydropower plant to a PSH system. The main parameters considered are the storage capacity of the lower reservoir, the maximum discharge rate of the pump group, and its efficiency. In sizing the lower reservoir, the upper limit has been set by referring to Italian regulatory thresholds, which classify dams exceeding one million cubic meters of volume under stricter technical and legislative requirements. Remaining below this limit simplifies authorization procedures and reduces the overall economic burden, making it a pragmatic assumption for this analysis. Regarding pumping operations, dedicated centrifugal pumps are assumed instead of reversible units such as Francis turbines, since the existing Pelton turbines are not reversible and their replacement is not planned [

50,

51]. Centrifugal pumps are suitable for high-head applications and can achieve efficiencies in the range of 85–90% under optimal conditions [

2]. For the study, a nominal efficiency of 85% is adopted, with the possibility of evaluating improvements up to 90% in subsequent calculations. The hydraulic losses are assumed to be consistent with those applied to generation operations, with an additional head margin included to account for the lower elevation of the reservoir. These assumptions provide a reasonable framework to evaluate the potential benefits and operational mechanisms of the proposed PSH configuration. It is important to clarify that the model does not perform a full techno-economic assessment, as operational costs, maintenance, investment and other financial outlays are not considered. The purpose of this work is to investigate operational optimization under given market conditions, focusing on performance improvements and trade-offs rather than overall project feasibility. Including detailed cost parameters would require additional site-specific and financial assumptions, which are beyond the intended scope of this study. Instead, the objective function is formulated to maximize revenues, calculated from the gross income of energy sales, while additional multi-objective formulations account for water availability and emission reduction. All results are expressed in relative terms (percentages) rather than absolute monetary values, in order to ensure comparability across different scenarios and years. This simplified framework allows the analysis to highlight the potential benefits of introducing pumping operations and integrating an FPV plant, providing a clear basis for evaluating both economic and non-economic improvements without the complexity of a full economic model.

2.6. Model Verification and Robustness Assessment

This section ensures that the proposed optimization framework operates correctly and consistently under all modeled conditions. Rather than validating against real plant data, the analysis verifies the mathematical soundness, numerical stability, and internal consistency of the model, ensuring that physical laws, operational constraints, and solver convergence are fully respected.

2.6.1. Mathematical Verification

The proposed optimization framework was verified to ensure mathematical correctness, physical consistency, and solver convergence. All governing equations were checked for dimensional coherence and physical soundness, confirming that mass and energy conservation are respected under all operational scenarios. The constraints defining turbine operation, pumping, reservoir volumes, and grid exchange were systematically inspected to guarantee feasibility within physical and operational limits. Solver logs confirmed successful termination under default convergence criteria, and no infeasible or unbounded solutions were encountered across the entire scenario set.

Table 1 demonstrates that the model is internally consistent and numerically robust, providing a reliable basis for the subsequent scenario and sensitivity analyses.

2.6.2. Sensitivity Analysis on Hypothetical Parameters

Since both the PSH and FPV components represent hypothetical configurations, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to verify that the model outcomes are not biased by arbitrary assumptions. Each key design and operational parameter was perturbed within a realistic technical range derived from literature and engineering feasibility.

Table 2 summarizes the tested parameters, their baseline assumptions, and the adopted sensitivity ranges.

4. Results

This section presents the findings of the study, which is aimed to investigate the economic and environmental benefits of transitioning from a traditional hydropower system to a hybrid plant composed of a pumped storage system coupled with a photovoltaic installation. The results are discussed in the context of enhancing efficiency, sustainability, and the potential scalability of such integrated energy systems.

4.1. Scenario 0—Baseline Operations

This baseline scenario represents the traditional hydropower configuration. The scheduling of turbine operations was obtained through a pure economic optimization, aimed at maximizing revenues under the given inflow and price conditions.

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of energy prices and the corresponding turbine dispatch. Turbine activity clearly shifts towards higher price periods, while low-price hours often coincide with nearly full reservoir levels and high inflows, where operation helps to avoid spillage. In this configuration, the turbine operated 2252 h in 2013, corresponding to a capacity factor of 25.5%. In 2013, baseline operations resulted in a gross revenue of €23.5 million, an annual generation of 325 GWh, and approximately 240 million cubic meters of water turbinated throughout the year. This scenario serves as the reference to investigate the impact of adding pumping operations.

4.2. Scenario 1

This scenario introduces the PHS configuration, its design parameters and the assessment of its economic and water-related implications.

To identify an optimal and economically viable combination of lower reservoir size and pump nominal discharge, an iterative optimization process was applied. The two interdependent variables were analyzed using the KneeLocator method in Python [

54], which identifies the knee point beyond which further increases yield diminishing returns. The procedure was repeated until convergence was reached, resulting in a reservoir volume of

m

3 and a maximum pump discharge of 14 m

3/s, values representing a good trade-off between performance and investment cost.

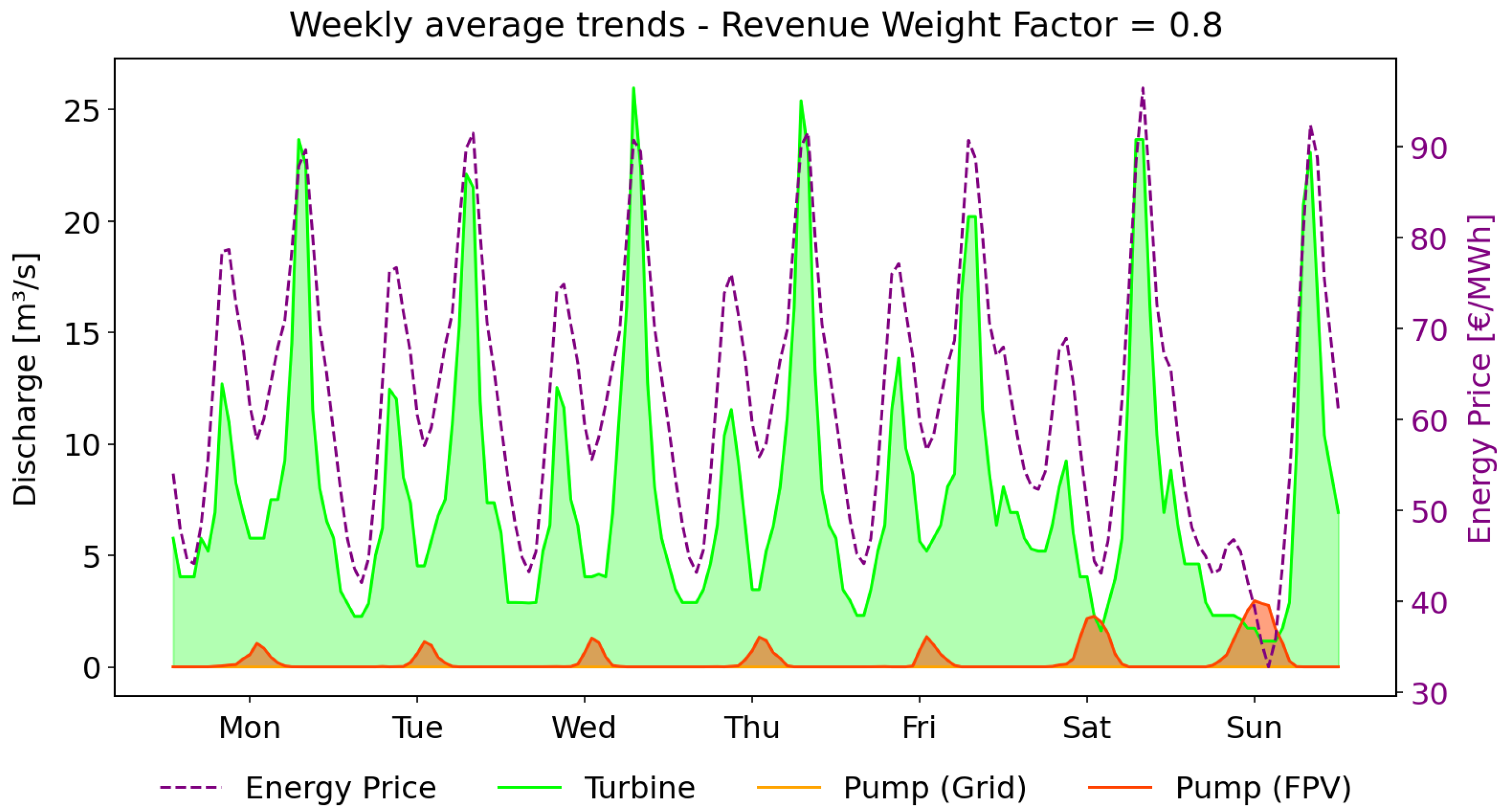

With respect to Scenario 0, the inclusion of pumping operations leads to a revenue increase of 8.0% in 2013 and 4.1% in 2014, confirming the added economic value of the PSH configuration. In 2013, the turbine and pump operated for 2945 and 1449 h, corresponding to capacity factors of 33.1% and 16.2%. An improvement in pump efficiency from 85% to 90% would further raise revenues by approximately 1.4%. The CO

2 emissions associated with the pumping energy consumption amount to

kg CO

2. The weekly dynamics shown in

Figure 5 which highlights the complementarity of operations: turbine discharges closely follow high-price peaks, especially on weekdays, while pumping is concentrated at night or off-peak periods. This confirms that the optimization effectively exploits price volatility to enhance plant profitability and system flexibility.

From a water management perspective, the results show that Scenario 1 maintains sufficient volumes not only for pumping operations but also for alternative uses such as irrigation and snowmaking, highlighting the multifunctional value of the reservoirs. The creation of a lower reservoir would introduce a new and reliable water source, while the existing upper reservoir already constitutes a substantial storage asset with potential benefits linked to its higher elevation and associated energy head.

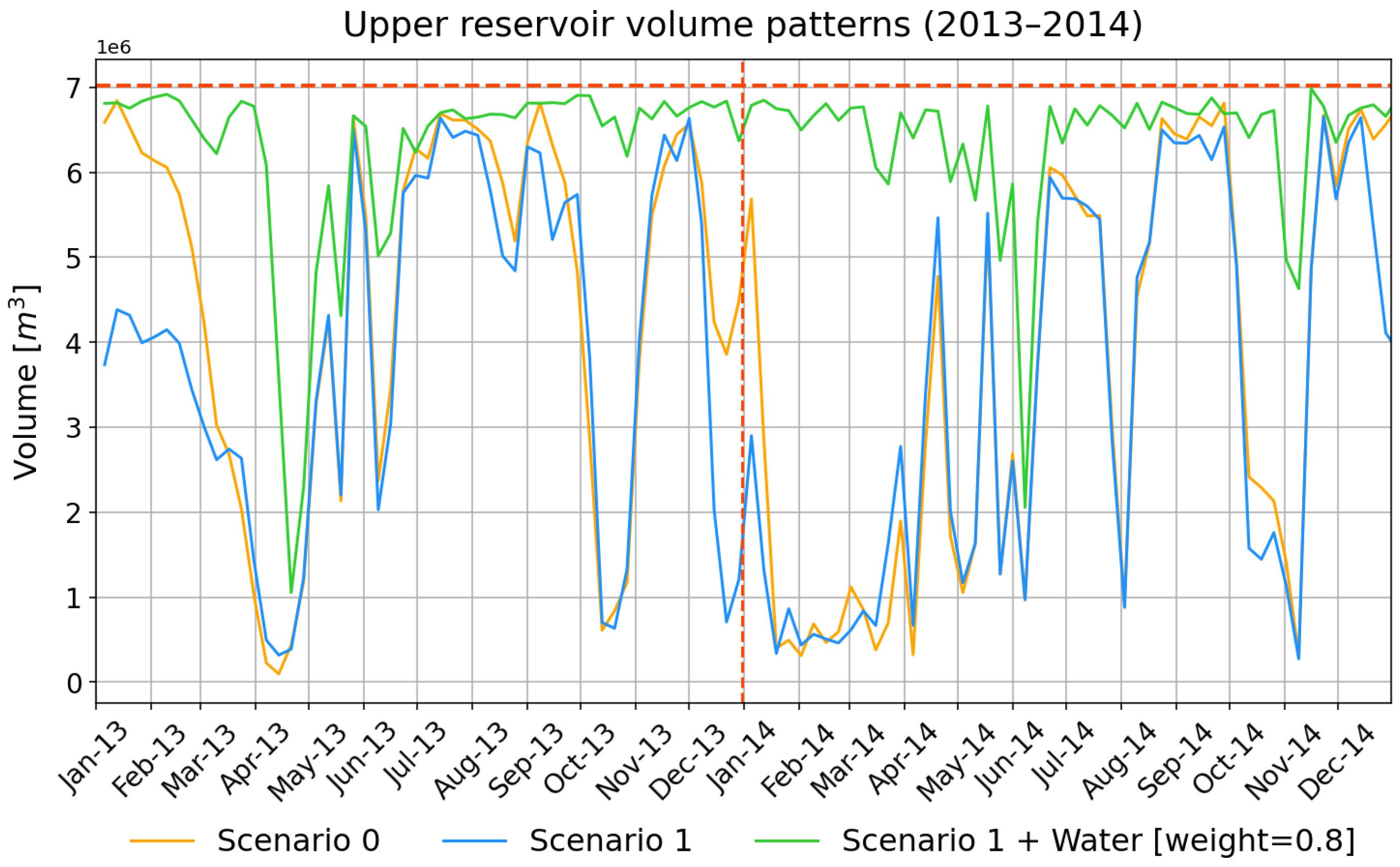

Figure 6 compares the upper reservoir volumes in Scenarios 0 and 1, showing that although the dynamics change, the system maintains adequate storage levels to support multiple purposes. This underlines the potential of the PSH configuration to contribute simultaneously to energy storage and regional water availability. To evaluate this aspect under the pure economic maximization approach,

Figure 6 compares the upper reservoir volumes in Scenario 0 and Scenario 1. The results show that Water Availability does not increase; on the contrary, the upper reservoir volume is often lower than in the reference case. This is reflected in the Water Availability metric, which reaches −12.7% in 2013 and −4.6% in 2014.

After analyzing the pure economic maximization approach, the focus now shifts to a multi-objective perspective where water resources are explicitly valued alongside revenues. This framework highlights that PSH–FPV integration can simultaneously provide economic and resource benefits, enabling trade-offs between profitability and sustainable management. As reported in

Figure 7 in 2013, deviating from the maximum revenue by only 20% increases water availability from −12.7% to 37.7%, with a minimal 0.9% loss in revenue. In 2014 improvements in water availability are even more significant: a Pareto-optimal solution with a weight of 0.8 results in nearly a 90% increase in Water Availability at the cost of just a 1.1% revenue reduction. These outcomes, achieved without external water extraction, underscore the capacity of optimized scheduling to deliver balanced gains in both economic performance and water sustainability.

In contrast to lower revenue efficiency, the potential benefits in water resource availability are significantly higher.

Figure 8 illustrates the comparison of upper reservoir patterns with and without pumping operations, considering results with weights of 1 and 0.8. This latter weight may represent a viable balance, prioritizing water resources without substantially compromising economic outcomes.

4.3. Scenario 2

Scenario 2 evaluates the integration of FPV with pumped storage, where the FPV system operates independently, with the energy generated sold directly to the grid, focusing on performance and revenue effects in the absence of operational coupling. All other parameters, including Water Availability and reservoir dynamics, remain the same as in Scenario 1, since pumping operations are not affected.

Three FPV configurations were tested: air-cooled system, water-cooled system and vertical-axis tracking. The findings show that, beyond land saving, FPV systems benefit from improved thermal management, with energy gains of about 2–3% when operating on water. The highest thermal advantage was observed for the water-cooling configuration, consistent with literature findings [

28]. Performance was assessed through standard indicators such as specific energy (SE), annual energy production (AEP), power density (PD), energy density (ED), capacity factor (CF), and performance ratio (PR), which are summarized in

Table A6. While water cooling provides efficiency and space-saving benefits, tracking systems significantly improve most performance metrics; therefore, the vertical-axis tracking configuration was selected as the reference option for Scenario 2, as it represents a promising solution to enhance energy yield and cost-effectiveness in floating applications [

7,

27,

34,

55].

Building on this configuration, the analysis evaluates different FPV coverage factors on the reservoir surface to assess their impact on plant revenues relative to Scenario 1. Five coverage levels were considered, ranging from 10% to 60%. Values below 10% were excluded as the additional FPV generation would be negligible compared to hydropower output, while values above 60% were not considered due to potential environmental and recreational impacts, as well as the reduced usable surface resulting from reservoir level fluctuations. As shown in

Figure 9, revenues increase almost linearly ranging from, ranging from ≈3% to >20 % as coverage expands from 10% to 60%. Based on these results, a coverage factor of 40% was selected as the optimal trade-off between energy gains, reservoir use, and potential environmental constraints, and is adopted as the reference configuration for subsequent analyses.

4.4. Scenario 3

This scenario explores the direct integration of FPV generation into PSH operations, evaluating both economic and environmental implications. In this configuration, the electricity produced by FPV is directly used for pumping, thereby reducing reliance on grid electricity. The model yields a revenue efficiency (

) equal to zero, indicating that no significant economic benefit arises from arbitraging FPV electricity when comparing Scenario 3 with Scenario 2. Consequently, the overall operational strategy of the PSH plant remains unchanged across all selected coverage factors. For instance, with an FPV plant of 48 MW

p corresponding to 40% reservoir coverage, only about 7% of PV output is used for pumping, since solar availability does not coincide with the most advantageous off-peak pumping hours (

Figure 10). Under the pure economic optimization, however, the use of FPV electricity for pumping still reduces CO

2 emissions by 7.2% in 2013 and 7.8% in 2014 compared to Scenario 2, highlighting the potential of FPV–PSH integration to improve sustainability even when economic impacts are limited.

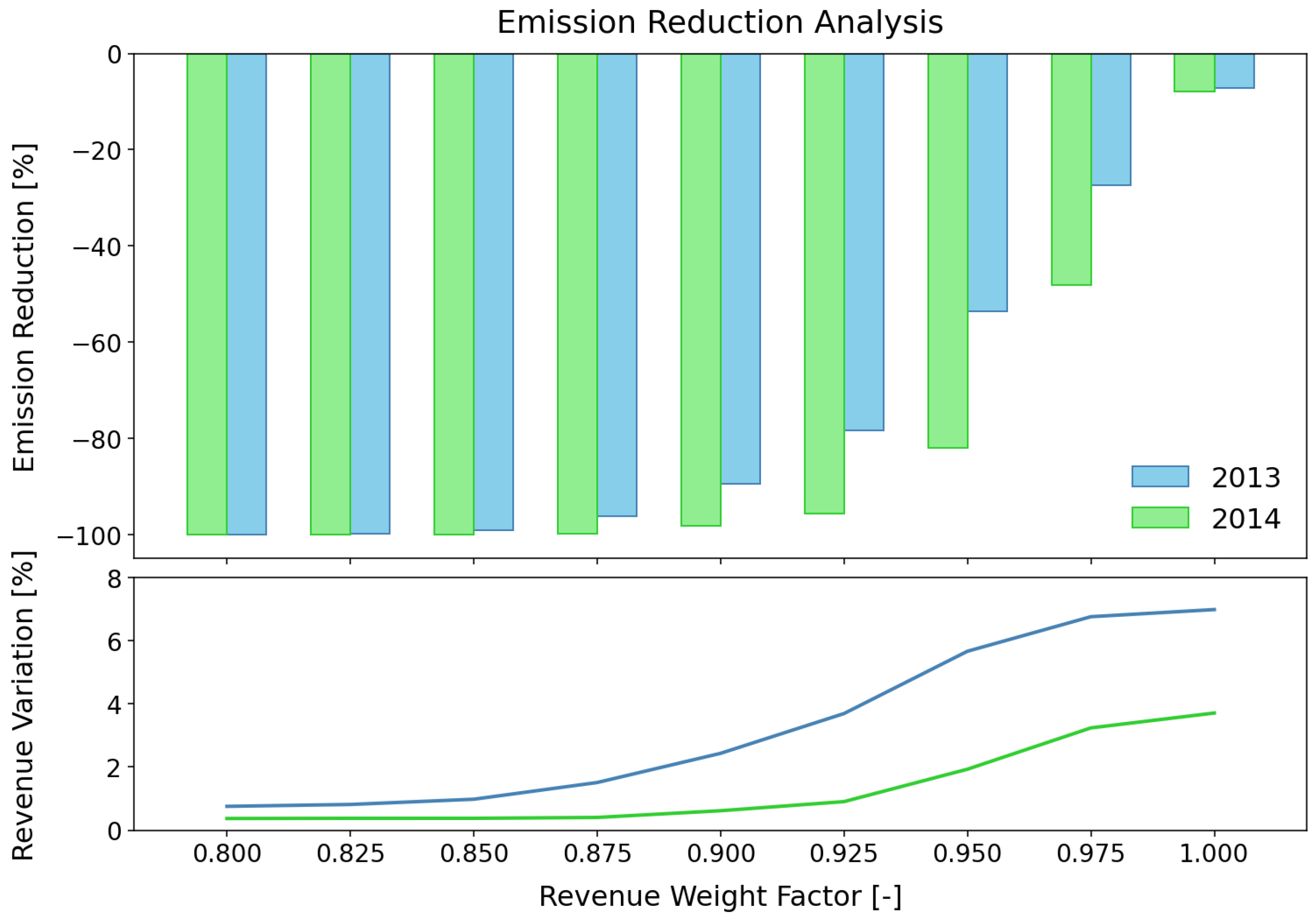

After analyzing the pure economic maximization approach, the focus now shifts to a multi-objective perspective where emission reduction is explicitly valued alongside revenues. This framework highlights that PSH–FPV integration can deliver drastic CO

2 reductions with only minor economic trade-offs, enabling a direct assessment of the decarbonization potential of pumping operations. The Pareto-optimal solutions (

Figure 11) reveal a logarithmic trend with a pronounced initial curvature: even small deviations from the revenue-maximizing solution lead to sharp declines in emissions. With a weight of 0.85, CO

2 emissions are reduced by more than 99% compared to Scenario 2, while the revenues associated with pump activity decrease by only 6.0 and 3.3 percentage points in 2013 and 2014, respectively. These results demonstrate that optimized scheduling can achieve near-complete decarbonization of pumping operations, confirming that the primary value of PSH–FPV integration lies in its capacity to cut emissions almost entirely, with economic impacts remaining comparatively modest.

Figure 11, together with

Figure 12, illustrates the reduced use of the solar resource. The latter shows that the highest energy utilization, obtained with a weight of 0.8, corresponds to a scenario where pumping operations are carried out exclusively during periods of solar availability. Nevertheless, the self-consumption rate reaches only 28.65%, indicating that allocating more PV output to pumping is less advantageous than directly selling it to the grid.

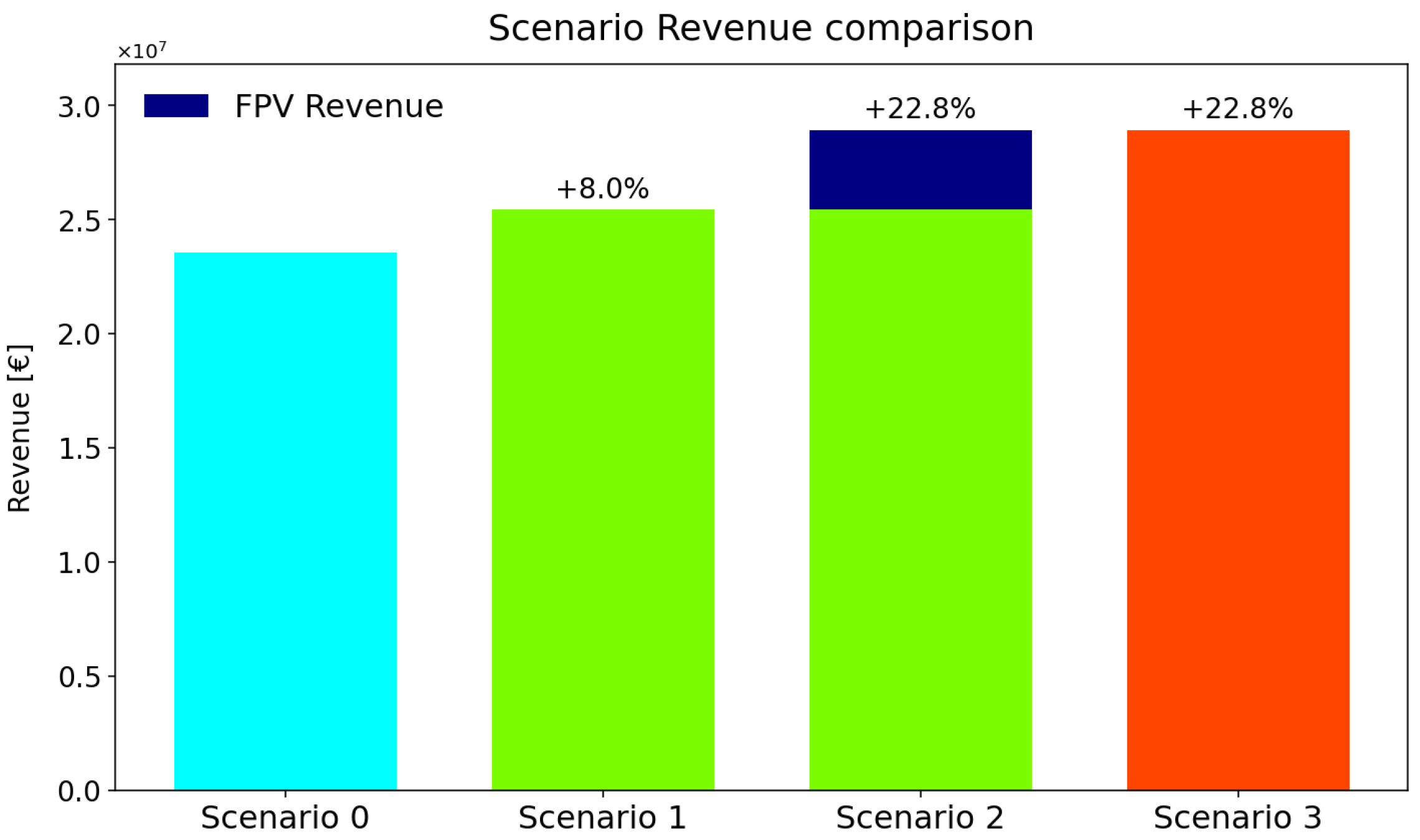

4.5. Scenario Comparison

Figure 13 compares annual revenues across the different scenarios. Scenario 1 (PSH) increases revenues by 8.0% over Scenario 0 (baseline scenario) due to the addition of the pumping operation. While Scenarios 2 and 3, considering a vertical-axis tracking FPV plant with a coverage factor of 40 % show a gain in revenue of around 13% from the additional FPV production, however, FPV integration does not improve the arbitrage strategy of the PSH system, as operational patterns remain largely unaffected.

Table 3 summarizes the results, comparing the pure-revenue optimization with the two multi-objective analysis.

4.6. Sensitivity and Uncertainty Analysis

This section extends the robustness assessment by quantifying model sensitivity to key design and operational parameters. The analysis evaluates how variations in pump discharge, lower reservoir volume, and FPV coverage influence the model outputs and overall revenue efficiency.

Table 1 and

Table 2 summarize the verification of model consistency and parameter sensitivity, while the 3D plot (

Figure 14) illustrates the combined impact of pump discharge and lower reservoir size on system performance. The sensitivity analysis confirms the robustness of the model with respect to design parameter uncertainty. A ±10% variation in pump efficiency results in a ±1.5% change in total revenues, while a ±20% variation in the hypothetical lower reservoir volume leads to a ±2.3% revenue change. Regarding FPV integration, variations in the reservoir coverage factor produce different levels of revenue increase, as shown in

Figure 9; however, no additional economic benefit from pumping operations emerges, indicating that FPV generation does not modify the underlying arbitrage strategy. The multi-objective logarithmic trade-offs between revenue and water availability, and between revenue and emission reduction (

Figure 7 and

Figure 11), remain consistent across all tested parameter ranges, indicating that the qualitative conclusions on the benefits of PSH and FPV–PSH hybrid systems are insensitive to design assumptions.

Scenario validation confirms that the optimized schedules exhibit the expected economic and physical behavior. Turbine operations concentrate during market peak-price periods (

Figure 4), while pumping is scheduled during off-peak hours (

Figure 5), demonstrating that the model correctly exploits electricity price arbitrage. The resulting multi-objective Pareto fronts are smooth and monotonically convex (

Figure 7 and

Figure 11), confirming a well-posed optimization without numerical artifacts. This behavior is consistent with the findings of recent PSH optimization studies, which show that economically rational pumping and turbining schedules naturally follow electricity price signals [

14,

19]. Similarly, hybrid FPV–PSH analyses indicate that the FPV contribution primarily increases total energy production without necessarily altering the underlying arbitrage strategy [

53,

56].

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study evaluates the integration of a hypothetical PSH–FPV to a real alpine hydropower facility. While the PSH lower reservoir, pump infrastructure, and FPV systems are not currently operational, the analysis is grounded in realistic technical and economic parameters derived from existing literature on comparable hybrid systems [

14,

19,

53,

56]. The sensitivity analysis (

Table 2) confirms that key outcomes—a 4–8% revenue increase due to PSH integration, the logarithmic revenue–water trade-off, and a near-complete reduction of pumping-related emissions—remain stable under ±10% variations in design parameters. This robustness provides confidence in the framework’s applicability for preliminary feasibility assessments, even though the specific infrastructure remains hypothetical. A full empirical validation would require either operational data from a built PSH-FPV installation under comparable hydrological and market conditions, which are currently scarce in the literature, or a pilot-scale demonstration of the proposed configuration. Instead, the multi-objective optimization framework and robust sensitivity analysis provide stakeholders with defensible estimates of potential performance to inform upgrade decisions. Nevertheless, similar simulation-based approaches have been successfully adopted for techno-economic evaluation of prospective hybrid systems [

19,

53,

56], indicating that the present multi-objective optimization and sensitivity framework can provide defensible insights to guide future upgrade decisions. The optimization results confirm that PSH remains the principal driver of economic and operational improvements in hybrid systems. By exploiting electricity price volatility, PSH effectively complements generation with pumping, enhancing revenue stability and overall plant flexibility. Beyond economics, however, the analysis shows that operational choices also influence water resource availability: under purely revenue-maximizing schedules, upper-reservoir levels decline compared to baseline operations. Multi-objective optimization reveals that this trade-off follows a logarithmic pattern, whereby small revenue concessions unlock disproportionately large gains in water availability. This effect is particularly evident in 2014, the dry year of the dataset, when the relative water availability benefits are amplified compared to 2013. With a weight factor of 0.8, corresponding to a 20% deviation from the maximum revenue, water availability increases by approximately 50% in 2013 and by nearly 87% in 2014, emphasizing the stronger influence of flow regulation under dry conditions. These findings are especially relevant given the increasing pressure on alpine water resources and highlight PSH’s dual role as both an energy storage asset and a water management tool.

FPV systems act as a complementary technology, adding renewable capacity while leveraging existing hydropower infrastructure. In this study, operation on water provided an energy gain of about 2–3%. Among the layouts, water-cooled configurations delivered the highest thermal benefit, though their overall effect remained secondary compared to tilt angle or tracking. Vertical-axis tracking achieved the largest increase in energy yield, confirming the indications from the literature that it represents a promising solution to enhance energy yield in floating applications. These trade-offs indicate that FPV’s main value lies not only in marginal efficiency improvements but also in space optimization and enhanced sustainability. When FPV is integrated without direct coupling, revenues scale nearly linearly with reservoir coverage, yet PSH operating patterns remain unaffected. In contrast, direct PSH–FPV coupling produces only modest economic changes but opens the door to significant emission reductions.

Multi-objective optimization demonstrates that near-zero pumping-related emissions can be achieved with limited revenue loss, confirming the environmental potential of hybridization. Nevertheless, grid sales remain the economically preferable outlet for PV production, limiting the share of self-consumption.

The novelty of this work lies in addressing a gap in the literature: while PSH and FPV have been extensively studied as stand-alone technologies, few analyses have jointly evaluated their integration in real-world alpine contexts under multi-objective frameworks. By explicitly considering trade-offs between revenues, water availability, and emissions, this study demonstrates that hybrid PSH–FPV systems can be optimized not only for profitability but also for sustainability objectives. The identification of logarithmic trade-off patterns provides a practical decision-making tool for stakeholders, showing that modest sacrifices in revenue can deliver substantial environmental and resource co-benefits.

In conclusion, PSH remains the backbone of economic performance, while FPV enhances sustainability and spatial efficiency. Their hybrid integration strengthens system resilience but also requires balancing competing objectives: maximizing revenue, ensuring water availability, and reducing emissions. These results offer valuable guidance for designing future hybrid infrastructures in alpine regions and beyond, aligning with broader European goals of energy transition, water security, and decarbonization.

Building on the results of this work, future research should explore additional renewable coupling and market integration. The inclusion of wind generation could enhance flexibility and seasonal storage potential. Extending the present framework toward a full techno-economic analysis that includes investment and O&M costs would further support long-term feasibility assessment. Moreover, emerging market structures and evolving regulations for energy storage may introduce dedicated products or compensation schemes, whose effects could be simulated to assess business opportunities and policy impacts. Finally, transitioning from retrospective scheduling to a predictive framework would enable dynamic electricity-market participation, where real-time price and inflow forecasting can support hydropower management in daily or weekly operation.