Abstract

Solar power forecasting is important for energy management and grid stability, yet many deep learning studies use a large set of meteorological and time-based variables because of the belief that more inputs improve model performance. In practice, a large feature set can introduce redundancy, increase computational effort, and reduce clarity in model interpretation. This study examines whether dependable forecasting can be achieved using only the most influential variables, presenting a minimal feature deep learning approach for short term prediction of solar power. The objective is to evaluate a Transformer model that uses only two key variables, solar irradiance and soil temperature at a depth of ten centimetres. These variables were identified through feature importance analysis. A real world solar power dataset was used for model development, and performance was compared with RNN, GRU, LSTM, and Transformer models that use the full set of meteorological inputs. The minimal feature Transformer reached a Mean Absolute Error of 1.1325, which is very close to the result of the multivariate Transformer that uses all available inputs. This outcome shows that essential temporal patterns in solar power generation can be captured using only the strongest predictors, supporting the usefulness of reducing the size of the input space. The findings indicate that selective feature reduction can maintain strong predictive performance while lowering complexity, improving clarity, and reducing data requirements. Future work may explore the adaptability of this minimal feature strategy across different regions and environmental conditions.

1. Introduction

Until 2021, South Korea relied on coal, gas, and nuclear power for 90% of its primary energy generation [1]. In 2020, greenhouse gas emissions resulting from the use of fossil fuel-based energy sources reached 598 million tons, placing the country 9th among the world’s highest greenhouse gas emitters [2]. To address this issue, the government announced the Korean Green New Deal in 2020, setting a target of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. As part of this, it finalized the “2050 Carbon Neutral Scenario and the Upgraded 2030 Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC)” with the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 40% compared to 2018 levels by 2030 [3].To meet these targets, the government aims to reduce its dependence on coal, gas, and nuclear power, and increase the share of renewable energy in electricity generation. However, as of 2020, the share of renewable energy in domestic power generation was only 7.4%, which is significantly lower than that of other countries such as Norway (98.4%), Brazil (84.1%), and New Zealand (80%). To improve the use of renewable energy, the government established the “Renewable Energy 3020 Implementation Plan,” which includes expanding renewable energy facilities to a total capacity of 48.7 GW by 2030 [4]. Consequently, technologies that enable efficient operation of solar power plants, which account for many renewable energy sources, have emerged as a critical area of research.

The transition toward renewable energy has increased the demand for efficient solar power generation and management. Solar energy is inherently intermittent due to its dependence on meteorological conditions such as cloud cover, temperature fluctuations, and atmospheric pressure. This variability poses challenges for energy distribution, grid stability, and storage management. To mitigate these issues, solar power forecasting has become essential for optimizing energy generation, ensuring a stable power supply, and improving integration into existing electrical grids. Reliable predictions allow grid operators to anticipate fluctuations, balance energy loads, and minimize reliance on backup power sources, which makes forecasting a crucial component in the widespread adoption of solar energy.

Recent advancements in machine learning and deep learning have significantly improved solar power forecasting capabilities. Traditional statistical models, such as autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) [5] and support vector regression (SVR) [6], have been widely used for time-series forecasting. However, these methods often struggle with complex, non-linear relationships between meteorological variables and solar power generation. In contrast, deep learning architectures, including Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [7], Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) [8], Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks [9], and Transformers [10], have demonstrated superior performance in capturing long-term dependencies, learning from large datasets, and adapting to fluctuating weather conditions. As a result, these models have been widely adopted in renewable energy forecasting applications.

A common assumption in deep learning-based forecasting is that increasing the number of input features enhances prediction accuracy [11]. Deep learning models for solar forecasting typically use various weather and time-related factors, such as solar irradiance, wind speed, humidity, temperature, and atmospheric pressure. The idea is that incorporating more features helps improve predictions. While using multiple features can improve solar forecasting, too many can introduce redundancy, increase computational load, and lead to overfit ting, where the model learns noise instead of meaningful patterns [12]. Some variables may be highly correlated or have little impact on predictions, making feature selection an important step in optimizing performance. This approach helps identify the most relevant variables while discarding those that add little value. Various methods, including statistical correlation analysis [13], principal component analysis (PCA) [8], and mutual information ranking, have been used to reduce input dimensionality. Despite these advancements, deep learning models for solar forecasting continue to rely on extensive feature sets, as removing variables could degrade predictive performance.

In contrast, this study challenges the conventional multivariate approach by demonstrating that a deep learning model trained on only two carefully selected features can perform comparably to models using a full set of meteorological inputs [14]. The use of a minimal feature set can lead to several advantages in solar forecasting. First, reducing the number of input variables can simplify model training, decreasing computational costs and making the approach more accessible for real-time energy management applications. Second, models trained on fewer but more meaningful features may be more interpretable, allowing researchers and engineers to better understand the relationships between critical environmental factors and solar power generation. Lastly, reducing dimensionality can enhance model generalization, as it minimizes the risk of learning spurious correlations in the training data that do not hold in real-world scenarios [15].

Deep learning models, particularly Transformer architectures [10], have demonstrated strong performance in time-series forecasting due to their ability to capture long-range dependencies and dynamic relationships between inputs. However, their effectiveness in solar forecasting has been primarily explored in the context of multivariate modeling, where multiple input variables are provided to the network. The Transformer-based model proposed in this study utilizes only two selected features, eliminating the need for a comprehensive set of meteorological inputs. This streamlined approach is designed to determine whether a minimalist feature selection strategy can maintain predictive accuracy while improving model efficiency.

The need for dependable solar power forecasting continues to grow as renewable energy adoption expands and power systems face increasing variability from changing environmental conditions. Forecasting models must provide stable guidance for energy planning, grid operation, and the management of distributed generation, yet many existing approaches depend on large numbers of meteorological variables that increase complexity without clear evidence of improved forecasting behavior. This situation creates strong motivation for exploring simplified modeling strategies that reduce input requirements while still capturing essential patterns in solar power generation. A minimal feature perspective offers a practical direction for improving accessibility, lowering computational burden, and supporting real time forecasting environments, which forms the foundation for the present study.

2. Literature Review and Research Gaps

Solar power forecasting has been widely studied using different modeling approaches, including statistical methods, machine learning models, and deep learning architectures. These techniques aim to improve forecasting accuracy by leveraging historical weather and power generation data while considering the variability in meteorological conditions. This section categorizes previous research into three key areas: statistical models, machine learning approaches, and deep learning techniques.

2.1. Statistical Models for Solar Power Forecasting

Statistical models have been widely used in solar power forecasting due to their ability to analyze historical trends and capture seasonal variations in time-series data. These models rely on mathematical relationships between input variables and power generation, if past trends can effectively predict future outcomes. While these approaches are useful for long-term forecasting, they often struggle to handle sudden weather fluctuations or complex non-linear relationships. Commonly used statistical methods include autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) [16], generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity (GARCH) [17], multilinear regression techniques [18], and hybrid statistical models [19].

Messida et al. [20] applied Multilinear Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS) combined with Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) data to forecast PV power output from a solar plant in Borkum, Germany. The model utilized solar irradiance, temperature, humidity, wind speed, and historical power output as input features. Performance evaluation using RMSE, MAE, MAPE, and nRMSE showed that the model achieved nRMSE values between 18–23% and MAPE between 22–28%. The study found that forecasting performance was highly dependent on cloud cover, with the best results obtained under overcast conditions. When compared to previous studies, this approach demonstrated competitive performance relative to other regression-based NWP forecasting methods.

Alsharif et al. [21] study focused on global solar radiation forecasting using ARIMA and SARIMA models. The research analyzed 37 years (1981–2017) of hourly solar radiation data from the Korean Meteorological Administration and applied ARIMA (1,1,2) for daily predictions and SARIMA (4,1,1) for monthly predictions. The results demonstrated that ARIMA models were effective in capturing seasonal trends, achieving an RMSE of 104.26 for daily forecasts and 33.18 for monthly forecasts, with R2 values of 68% and 79%, respectively. However, the study also highlighted that ARIMA models could struggle with short-term variability and sudden fluctuations in solar radiation. In another work, hybrid ARIMA models were combined with Random Forest (RF) and Bagging Classification and Regression Trees (BCART) to improve short- and mid-term wind power forecasting. The model incorporated wind speed, wind direction, air temperature, air pressure, and air density at hub height as predictive variables. The hybrid ARIMA-RF and ARIMA-BCART models outperformed standalone ARIMA, achieving an NMAE reduction of 18–26%. The study demonstrated that combining statistical forecasting with machine learning techniques could enhance accuracy, especially in scenarios where non-linear interactions exist between variables.

Lago et al. [22] study explored daily electricity load forecasting using an ARIMA-GARCH model applied to intraday electricity demand data from ten European countries. This model integrated time-series decomposition and volatility modeling to capture fluctuations in energy demand. The results showed that the ARIMA-GARCH approach achieved a MAPE of 1–3%, outperforming traditional forecasting methods. The study emphasized the importance of volatility modeling in electricity load prediction, particularly for grid operations requiring high levels of reliability. To further improve forecasting accuracy, researchers have integrated hybrid ARIMA models with Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) and Support Vector Machines (SVMs) for wind speed and power generation forecasting. By decomposing time-series data into linear (ARIMA) and non-linear (ANN/SVM) components, the study found that hybrid models provided forecasting accuracy improvement of up to 5.5% for wind speed and 3% for wind power generation. However, the authors noted that hybrid models offered only limited benefits when ARIMA models were already performing well, suggesting that their effectiveness depends on the characteristics of the dataset.

Das et al. [23] approach on Support Vector Regression (SVR) was optimized using Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to forecast solar power generation based on online weather reports and historical solar power generation data from three different PV systems. The model outperformed GA-SVR, ANN, and Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) models, achieving an nRMSE of 2.841% and a correlation coefficient of 0.8614. The results highlighted that PSO-optimized SVR reduced computational costs while maintaining high accuracy, making it suitable for industrial applications in grid-connected PV systems.

Lastly, Shi et al. [24] evaluation on hybrid forecasting approaches compared ARIMA, ANN, and SVM for wind power prediction. The study found that ARIMA-ANN and ARIMA-SVM hybrid models improved forecasting accuracy by up to 5.5% for wind speed and 3% for wind power generation. However, the researchers emphasized that hybrid models were not always superior to standalone models and that their effectiveness depended on the complexity of the forecasting problem. While statistical models provide a strong foundation for renewable energy forecasting, their reliance on historical trends makes them less effective for handling highly volatile weather conditions. To address these limitations, machine learning techniques have been increasingly adopted to capture non-linear dependencies, optimize feature selection, and improve overall forecasting accuracy.

2.2. Machine Learning-Based Approaches for Solar Power Forecasting

Machine learning models have gained prominence in solar power forecasting due to their ability to capture complex, non-linear relationships between meteorological parameters and energy generation. Unlike traditional statistical methods, machine learning algorithms can leverage large datasets, optimize feature selection, and adapt to dynamic weather conditions. Various techniques, including Support Vector Machines (SVM) [25], Random Forest (RF) [26], Gradient Boosting (GB) [27], k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) [28], and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) [29], have been applied to solar irradiance prediction, PV power forecasting, and wind energy estimation.

Hiremath et al. [30] used meteorological data from the NSRDB dataset to predict Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI) using a range of models, including Linear Regression (Gradient Descent), Decision Trees, RNNs, RF, LSTM, SVM, CVNN, and LightGBM. The researchers applied Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for feature selection, and among all models tested, CVNN achieved the lowest MSE (58.7) and RMSE (7.6), outperforming other machine learning models. The findings demonstrated that machine learning significantly improves solar irradiance forecasting, with CVNN showing the highest potential for future applications integrating satellite data and deep learning techniques. Buonanno et al. [31] examined PV power forecasting by combining machine learning with numerical weather prediction (NWP) models. Using historical PV power generation data, the authors tested LSTM, XGBoost, and LightGBM. The results indicated that linear models improved RMSE by at least 3.7% compared to two NWP-based baseline methods, demonstrating that machine learning can enhance PV power forecasting beyond traditional NWP models. For short-term intra-hour solar forecasting, researchers evaluated kNN and Gradient Boosting (GB) models using Pyranometer measurements of GHI and Direct Normal Irradiance (DNI) along with sky images. The results showed an RMSE skill improvement of 8–24% for GHI and 10–30% for DNI, with CRPS skill scores of 42% (GHI) and 62% (DNI). The study highlighted that GB outperformed kNN for point forecasts, while kNN was more effective for probabilistic forecasts, suggesting that different models are suited for different forecasting tasks.

Rafi et al. [32] study analyzed 149,015 instances of meteorological data from Bangladesh using Random Forest (RF), Decision Trees (DT), Linear Regression (LR), and XGBoost (XGB). The RF model achieved the highest accuracy with R2 = 0.96 and RMSE = 0.267, significantly outperforming DT (R2 = 0.857), LR (R2 = 0.915), and XGB (R2 = 0.931). The study emphasized that feature engineering played a crucial role in improving forecasting accuracy, with the RF model proving to be highly reliable for solar energy resource assessment in Bangladesh. Munshi et al. [33] applied Random Forest (RF) to weather prediction using meteorological data from the India Meteorological Department (IMD), Pune, including temperature, surface pressure, and humidity. The RF model achieved an MSE of 0.750 and an R2 score of 0.97, outperforming statistical regression models and Support Vector Machines (SVM). The study suggested that RF models can estimate solar radiation and wind speed, eliminating the need for costly measuring instruments in remote locations.

Vladislavleva et al. [34] focused on wind energy forecasting in Australia applied Symbolic Regression (Genetic Programming) using DataModeler to predict wind energy output based on wind gust speed and dew point temperature. The model achieved an R2 of 85.5% for test data, demonstrating that symbolic regression techniques can effectively model wind energy generation with minimal input variables, making them particularly useful for small-scale wind farms. In Alice Springs, Australia, researchers tested Linear Regression, Polynomial Regression, Decision Tree Regression, Support Vector Regression (SVR), Random Forest Regression, LSTM, and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) Regression for PV power forecasting. The study found that humidity, temperature, and solar radiation were the most influential factors, while daily precipitation had a minimal effect. However, forecasting under cloud-cover conditions remained challenging due to data limitations, highlighting the need for improved models that can handle weather uncertainties.

Yousif et al. [35] studied on PV electricity production under hot weather conditions, researchers compared Self-Organizing Feature Maps (SOFM), Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Polynomial Function Models. The SOFM model achieved the best performance with an MSE (Training) of 0.0007, an MSE (Validation) of 0.0005, and an R2 of 0.9555, outperforming MLP and SVM models. This study emphasized that SOFM effectively captures non-linear relationships between weather conditions and PV output, making it suitable for extreme climate scenarios. A comparative study between ARIMA, Linear Regression (LR), and Random Forest (RF) for solar and wind power generation forecasting in India found that ARIMA outperformed RF and LR, achieving the lowest MAE, MSE, and RMSE values for both solar and wind energy predictions. The findings indicated that machine learning models can capture complex relationships, but traditional time-series models remain competitive in structured forecasting scenarios.

Bajpai et al. [36] studied on hybrid approach combining clustering, classification, and regression was tested against SVR with Radial Basis Function (RBF) and Random Forest (RF) for PV power forecasting. The hybrid model achieved the best performance with an RMSE of 109.48, outperforming SVR (RMSE = 178.23) and RF (RMSE = 120.74). The results suggested that hybrid models can significantly enhance forecasting accuracy by leveraging multiple learning techniques. For PV power forecasting in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, a study compared SVR, ANN, and a Persistence Model. The SVR model achieved an nRMSE of 3.08%, MAE of 34.57 W, and MBE of 11.34 W, outperforming ANN and Persistence Models. The findings suggested that SVR-based models provide stable forecasts across different weather conditions, with deviations within an acceptable range (≤10%). Lastly, an ANN-based model for solar energy generation prediction was evaluated on historical solar energy production data and corresponding weather variables. The ANN model achieved prediction errors ranging between 0.5% and 9%, demonstrating its effectiveness for grid control and energy market operations.

2.3. Deep Learning-Based Approaches for Solar Power Forecasting

Deep learning has emerged as a powerful tool for solar power forecasting, offering the ability to capture complex temporal dependencies and spatial correlations in energy generation data. Unlike traditional statistical and machine learning models, deep learning architectures such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks [37], Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [38], Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [39], and hybrid models combining CNNs and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [40] shown strong capability in modeling nonlinear relationships, greater adaptability to varying weather conditions, and improved generalization across datasets.

2.3.1. LSTM-Based Approaches

Qing et al. [41] investigated hourly day-ahead solar irradiance prediction using LSTM, Backpropagation Neural Networks (BPNN), Linear Regression (LR), and a Persistence Model. Using two datasets: Cape Verde (2 years) and MIDC (9 years training, 1-year validation), the LSTM model outperformed BPNN by 18.34% (Cape Verde dataset) and 42.9% (MIDC dataset) in RMSE. The study found that LSTM-based structured output prediction significantly improves accuracy compared to single-output models, reducing overfitting and capturing dependencies between different hours of the same day. A separate study examined short-term PV power forecasting using LSTM, Extreme Learning Machine (ELM), General Regression Neural Network (GRNN), and Recurrent Neural Network (RNN). The researchers utilized historical PV power data and synthetic weather forecast data while applying data normalization and handling missing values. The LSTM model improved accuracy by 33% compared to the hourly sky forecast and 44.6% compared to the daily sky forecast, proving superiority of LSTM in time-series forecasting.

The LSTM-based model by Yu et al. [42] was tested for short-term solar irradiance forecasting under complicated weather conditions. The study incorporated historical global horizontal irradiance (GHI) data, clearness index, and weather classification using k-means clustering. The LSTM model achieved R2 > 0.9 for hourly forecasts on cloudy and mixed days, significantly outperforming RNN, ANN, and SVR. These results demonstrated that introducing the clearness-index and classifying weather conditions improved forecast accuracy, making LSTM models more generalizable across different locations. The study on low-cost PV power prediction done by Khortsriwong et al. [43] used publicly available weather reports and PV power measurements from two PV systems in Oldenburg. The LSTM model, trained with air temperature, humidity, cloudiness, precipitation, clear-sky PV power, and maximum PV power from the last five days, achieved its best accuracy with a 90-day training set. The results showed that publicly available weather data can be effectively used for energy management, though not for grid stabilization.

2.3.2. CNN-Based and Hybrid Models

The study on Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) with multiple inputs by Ghimire et al. [44] was applied to wave power generation forecasting using open-sea testing data from a Wave Energy Converter (WEC). The model transformed 1D time-series data into 2D image data, significantly improving forecast performance. The CNN outperformed ANN, SVM, Model Tree (MT), Bagged Trees (BT), and Regularized Linear Regression (RLR), achieving RMSE = 3.11, MAE = 1.92, and R2 = 0.96.

A CNN-LSTM architecture (DSCLANet) with a self-attention mechanism was applied for short-term solar power forecasting using the DKASC Alice Springs Solar Dataset in the work of Alharkan et al. [45]. The model leveraged meteorological parameters and historical solar power output, achieving MSE = 0.0136, MAE = 0.0304, and RMSE = 0.0458, improving over existing state-of-the-art models. This study concluded that combining CNNs with LSTMs enhances both spatial and temporal feature extraction, significantly reducing prediction error.

Perera et al. [46] introduced Hierarchical Temporal Convolutional Neural Networks (HTCNN) for day-ahead regional solar power forecasting across 101 locations in Western Australia. The model, which utilized historical power generation and weather data, achieved a Fractions Skill Score (FSS) of 40.2% and reduced forecast error by 6.5%. The HTCNN-based approach demonstrated the ability to leverage both aggregated and individual time series for large-scale regional forecasting, outperforming other deep learning models. A hybrid CNN-LSTM model was evaluated for solar power generation prediction using the Traditional Encoder—Single Deep Learning (TESDL) framework and nearly a year of solar-intensity readings. The SVM-based forecast model improved accuracy by 27% over conventional methods, while deep learning approaches outperformed traditional forecasting techniques. In another study, a six-layer feedforward Deep Neural Network (DNN) was used for sensorless PV power forecasting in grid-connected buildings. The model, trained on publicly available weather forecast data, achieved an MAE of 2.9%, demonstrating that deep learning can effectively forecast PV power output without requiring on-site meteorological sensors.

The CNN model called “SUNSET” specialized by Sun et al. [47] was applied for 15-min ahead solar power forecasting using minutely averaged PV output and sky images. The hybrid model achieved a forecast skill improvement of 16.3% in cloudy conditions and 15.7% in all weather conditions, proving that sky image data is crucial for high-accuracy solar forecasting. A hybrid CNN-GRU deep learning model was tested for very short-term (5-min intervals) wind power generation forecasting using wind power data from Bodangora and Capital wind farms in Australia. The CNN-GRU model improved MAE by 1.59%, RMSE by 3.73%, and MAPE by 8.13% compared to other models, proving that CNNs extract complex features while GRUs learn time dependencies effectively.

2.3.3. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Advanced Deep Learning Models

Wang et al. [48] explored the use of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) combined with CNNs for weather classification in day-ahead PV power forecasting. The model processed solar irradiance data and meteorological weather types, reclassifying 33 weather types into 10 classes. GAN-based data augmentation significantly improved classification accuracy, allowing CNNs to outperform traditional models such as SVM, MLP, and kNN. The study concluded that GAN-based weather classification enhances PV power forecasting by identifying the best model for different weather conditions.

Weng et al. [49] specialized on wind power forecasting and their study introduced Extended Attention-based LSTM with Quantile Regression (EALSTM-QR) using numerical weather prediction (NWP) data. The model demonstrated better probability integral transform (PIT) distribution and improved probability density function (PDF) reliability compared to traditional machine learning approaches. Lastly, Massaoudi et al. [50] analyzed the performance of various deep learning models for PV power forecasting at a 1.5 MWp floating PV plant. The models included RNN, CNN, LSTM, GRU, Bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM), CNN-LSTM, and CNN-GRU. The BiLSTM model achieved the best accuracy with MAE = 34.67 kW, MAPE = 10.56%, and RMSE = 75.06 kW, while the CNN model performed the worst (MAE = 191.62 kW, MAPE = 62.43%, RMSE = 250.35 kW). These results highlighted that temporal models outperform spatial models in PV forecasting with hybrid models offering additional benefits.

2.3.4. Solar Power Generation Forecasting Methodology

The power output of a solar power plant is highly dependent on external environmental conditions, which can impose limitations on energy generation. To address the variability in solar power production, this study employs a structured forecasting approach consisting of two main stages. In the first stage, climate and operational data essential for model development are collected and preprocessed, including data acquisition, handling of missing values, and normalization to ensure consistency. In the second stage, a machine learning model is developed and evaluated to predict future power generation based on climatic conditions. The model captures the relationship between environmental variables and solar power output, enabling reliable forecasting across different weather scenarios. By integrating diverse environmental influences, the proposed forecasting model supports the stable operation of solar power plants and facilitates optimized energy management strategies.

This study introduces a minimal feature approach for solar power forecasting by examining whether two essential environmental variables can support forecasting performance comparable to models that rely on large sets of meteorological data. The main contributions are as follows. First, a focused feature selection strategy is applied to identify the most influential variables for forecasting. Second, a Transformer model is developed using only solar irradiance and soil temperature at a depth of ten centimeters, offering a simplified alternative to conventional multivariate designs. Third, experimental results demonstrate that reduced input dimensionality can maintain strong forecasting behavior while lowering complexity and improving clarity in model interpretation. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents an overview of previous research. Section 3 describes the dataset and feature selection process. Section 4 introduces the Transformer based forecasting model and experimental evaluation. Section 5 concludes the study and outlines future research directions.

3. Datasets

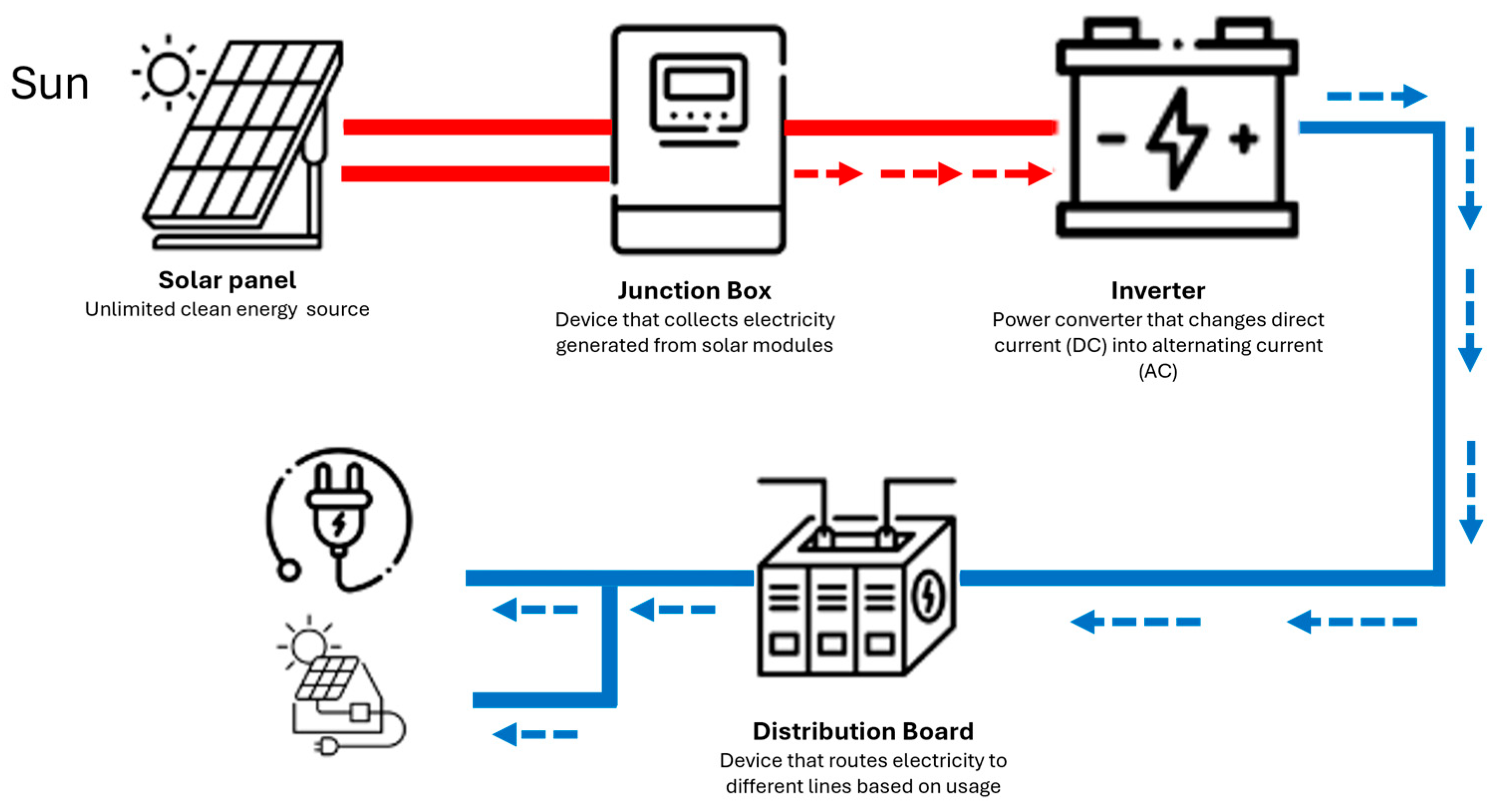

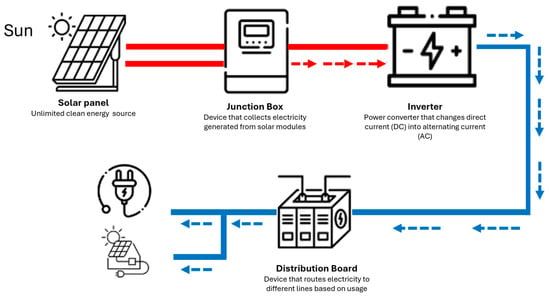

The methodology proposed in this study is developed based on a photovoltaic (PV) system operating in Gangjin County, South Korea. The solar power generation system consists of five main components: solar panels (modules), a junction box, an inverter, a distribution board, and electricity meters for both purchasing and selling power. The solar panels (modules) are the core component of the system, where multiple solar cells are combined to form panels, and multiple panels are assembled into modules. The junction box collects the electricity generated by solar modules, while the inverter converts the DC (direct current) power produced by the solar cells into AC (alternating current) power for household use. The distribution board directs the electricity to different circuits based on its usage, and the electricity meters record both the power consumed and the power fed back into the grid. In this study, the primary focus for solar power generation forecasting is on the solar panels (modules), as they are directly responsible for converting solar energy into electricity. As shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

System architecture of photovoltaic power plants.

Solar power forecasting requires a combination of real-world power generation data and meteorological data to develop predictive models. The dataset used in this study consists of historical photovoltaic (PV) power generation records and corresponding weather parameters collected over an extended period. These datasets are carefully preprocessed and structured to ensure consistency, reliability, and suitability for machine learning and deep learning models. The solar power generation data provides information on the hourly energy output of a photovoltaic system. This data represents the amount of electricity generated at different times of the day and is directly influenced by external environmental conditions. The dataset includes cumulative power generation values, voltage and current measurements of the PV system, and efficiency metrics of the solar panels. This data was sourced from operational PV plants in Gangjin County, Jeollanam-do, South Korea, covering a time range of 2019–2021, ensuring a comprehensive representation of solar energy production trends.

The meteorological data was provided in separate yearly datasets, each containing hourly observations. These datasets were combined into a unified collection after confirming that the measurement formats and variable definitions were consistent across years. To ensure data reliability, the merged records were reviewed for missing values and irregular entries. Periods of system downtime and incomplete measurements were removed before model development. Outliers caused by sensor malfunction or abnormal weather reporting were examined using distribution checks, and values that fell outside the realistic operating range of the photovoltaic system were excluded. These steps resulted in a clean and consistent dataset suitable for predictive modeling.

The solar power plant analyzed in this study operates based on the photoelectric effect, where solar panels convert sunlight into electrical energy by absorbing solar irradiance. The higher the irradiance, the more energy is absorbed, leading to an increase in power generation. Utilizing this characteristic, the power generation data serves as a key performance indicator for the plant and is systematically measured for analysis. Climate data represents atmospheric and environmental factors that influence power generation. In this study, 35 meteorological variables are used as environmental data, including solar irradiance, wind speed, sunshine duration, 10 cm deep soil temperature, and cloud cover, among others. These variables are essential for understanding the impact of external conditions on solar power output and play a critical role in the forecasting process.

Table 1 provides an overview of the solar power generation and climate data collected for model development. The power generation data, which serves as a key indicator of the plant’s operational status, consists of cumulative power generation records from a solar power facility in Gangjin County, Jeollanam-do, South Korea, spanning a three-year period from 2019 onward. The climate data was obtained from the Korea Meteorological Administration’s Open Data Portal and includes 35 meteorological variables recorded at a weather station 6.9 km from the location of solar power plant. These climate variables capture essential atmospheric conditions that influence solar power generation. The data was collected at hourly intervals, ensuring a high-resolution dataset suitable for predictive modeling. Excluding periods of system downtime, a total of 8962 observations were recorded, providing a robust dataset for forecasting solar power output.

Table 1.

Variables for power generation prediction.

The database is designed to systematically store and manage 8962 recorded data points collected through sensor measurement as shown in Table 2. Each data entry is assigned a unique measurement index in the first column, which sequentially numbers the recorded values in chronological order. The second to sixth columns (x1 to x35) contain environmental data at the time of observation, representing key meteorological factors that influence solar power generation. These include parameters such as solar irradiance, wind speed, soil temperature, humidity, and other relevant atmospheric variables. The final column (y) represents the measured power generation value, which serves as the primary performance indicator of the solar power plant under the given environmental conditions. This structured data format enables efficient data retrieval and processing, facilitating the development of machine learning based predictive models for solar power forecasting.

Table 2.

Data structure and examples.

3.1. Data Standardization and Definition of Model Input and Output

To minimize the impact of variations caused by differences in measurement units among collected data, standardization [51] is applied as a preprocessing step for environmental variables. Standardization is a commonly used technique to transform numerical variables, ensuring consistency in their distribution while reducing potential biases in analysis. This process is also employed to prevent losses in model training speed and performance that may arise from extensive computational operations. In this study, standardization is performed using the mean and standard deviation of the dataset, a widely used approach in machine learning applications. After standardization, the transformed input data follows a distribution with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, enabling a more stable and efficient learning process. The formula used for standardization is as follows:

The standardized value x(standard)i is calculated by subtracting the mean of the dataset from each individual data point xi and then dividing the result by the standard deviation (std(x)). Standardization is performed individually for each feature, preventing discrepancies caused by differences in measurement units. Table 3 presents the standardized values for features x1~x36, demonstrating how each variable has been transformed to maintain consistency across the dataset.

Table 3.

Standardized Data structure and examples.

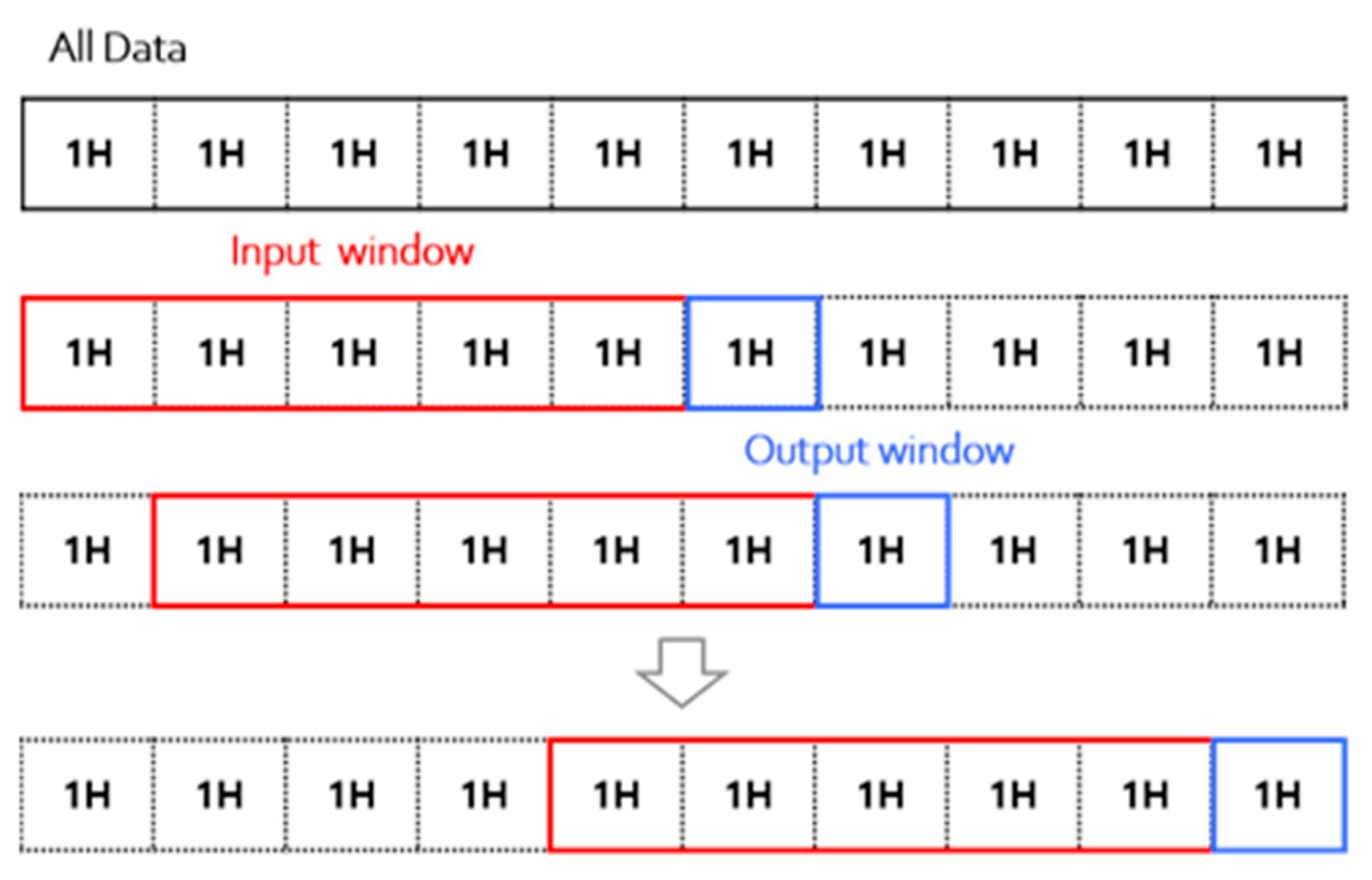

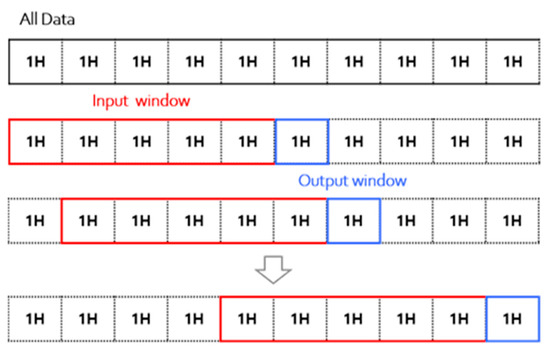

In this study, a sliding window [52] approach is applied to convert climate and power generation data into a sequence-based format suitable for time-series forecasting. The sliding window technique involves defining a fixed window size and sequentially extracting input-output pairs from historical data. For model training, a window size of 5 is used, meaning that the model takes the past 5 h of climate and power generation data as input. The output window size is set to 1, predicting the power generation value 1 h ahead as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Sliding window for input/output data.

A window size sensitivity analysis was additionally performed to evaluate the influence of different temporal contexts on forecasting performance. Sliding windows of 3, 5, 8, and 12 h were examined. The model performed better with a 5-h window than with a 3-h window (3-h: MAE = 1.3734, RMSE = 1.9682; 5-h: MAE = 1.2260, RMSE = 1.7693), indicating that extending the look-back period enhances the model’s ability to capture short-term fluctuations in solar power generation. Window sizes of 8 and 12 h were not evaluated, as applying longer look-back periods requires a larger dataset to generate enough training sequences. These findings show that the 5-h window provides a practical balance between temporal context and data availability.

Additionally, due to the time-series nature of the data, the model incorporates past power generation values to capture trends and patterns. Specifically, the past power generation value was added as the 36th input variable (x36) by applying a sliding window approach, which transforms sequential data into input–output pairs. This method allows the model to use the power generation value from 36 steps earlier as an additional feature, enhancing its ability to learn temporal dependencies, as shown in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 4.

Standardized data structure after applying the sliding window (5-h input, 1-h output).

Looking at Table 4, the operational environment data from the first to the fifth monitoring time points is recorded, while the power generation at the sixth time point is measured as 7.2. This indicates that the features of the operational environment observed from monitoring indices 1 to 5 influence the measured power generation of 7.2 at the sixth time point. In Table 4, the monitoring data for variables x1 to x36 across the 5-time intervals is used as input data for the machine learning model. The power generation data at the 6th time point is used as the output data. The input data undergoes a standardization preprocessing step before being fed into the model.

In the previous development of solar power generation forecasting model using solar facilities and climate data [53], all available meteorological variables were used for multivariate solar power forecasting. This study incorporated temperature, humidity, wind speed, solar radiation, and other environmental factors to evaluate deep learning models, including RNN [40], GRU [53], LSTM [37], and Transformer models [54]. As shown in Table 5, all models performed similarly in univariate settings, the Transformer model showed the best performance in the multivariate analysis, demonstrating its ability to capture complex relationships in solar power data. In contrast, this study used XGBoost’s SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values to select only the most relevant variables instead of using all available features. Feature importance analysis identified solar irradiance and temperature as the key predictors, allowing a minimal feature selection approach for the Transformer model. Despite using all variables, the performance of model remains comparable to the multivariate Transformer model from the paper as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Model performance comparison.

This study highlights that deep learning models do not require a high-dimensional feature set to produce reliable solar power predictions. Selecting only the most relevant features can maintain strong predictive performance while significantly reducing computational complexity, reinforcing the effectiveness of XGBoost-based feature selection in Transformer-based forecasting models. The higher multivariate MAE values for GRU (3.84) and RNN (4.51) result from the difficulty these models face when using all 36 meteorological variables. Both architectures are sensitive to high-dimensional inputs, and RNN-based models are further limited by vanishing-gradient effects, which reduce their ability to learn meaningful patterns in multivariate settings. In contrast, the Transformer handles large feature sets more effectively through its attention mechanism, allowing it to focus on the most relevant variables. This difference explains the stronger multivariate performance of the Transformer compared to GRU and RNN.

3.2. Feature Selection Approach

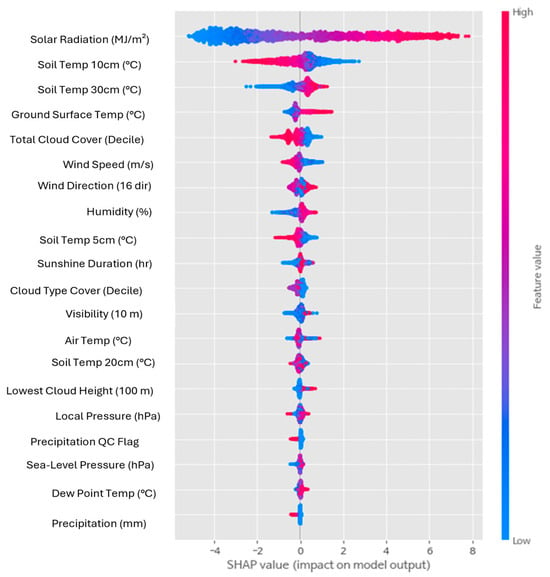

XGBoost [55] is applied for feature selection to identify the most significant variables influencing solar power generation. Using SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values [56], the contribution of each feature in the dataset is assessed. This approach determines which variables have the highest impact on the prediction model. Instead of using all available meteorological and solar facility variables, only the most relevant ones are selected to improve model efficiency. Feature importance analysis [57] reveals that solar irradiance and 10 cm soil temperature are the two most influential predictors, making them the primary inputs for the Transformer model.

By selecting only two key features, the dimensionality of the input data is reduced while maintaining strong predictive capabilities. High-dimensional datasets often contain redundant or weakly correlated variables that can introduce noise and increase computational costs. Removing less relevant features improves model interpretability and training efficiency. The selection of solar irradiance is expected, as it directly influences solar panel output, while 10 cm soil temperature likely plays a role in capturing environmental conditions affecting solar energy production. This minimal feature selection approach ensures that the model focuses on the most impactful variables without being affected by unnecessary data.

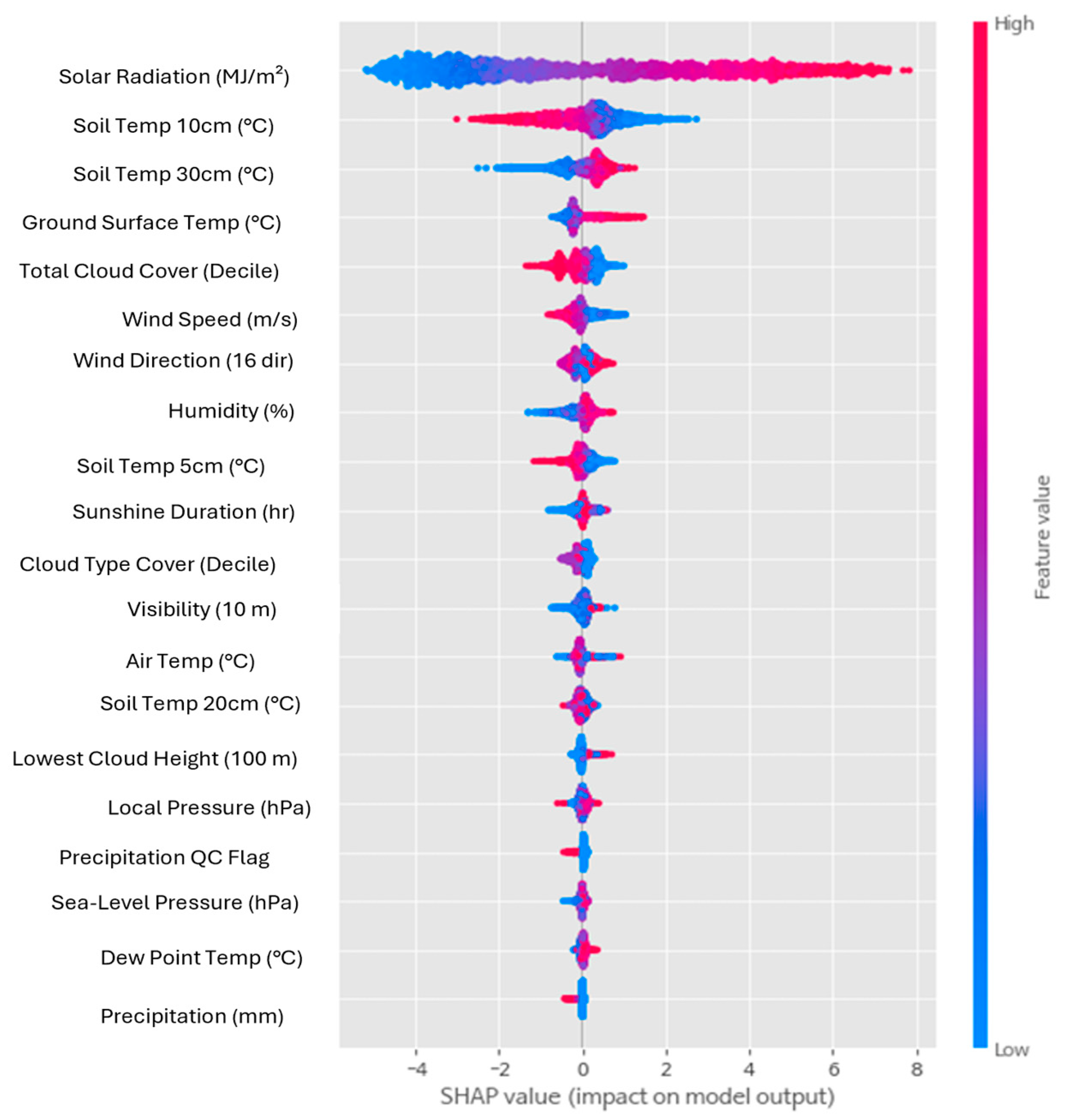

Figure 3 visualizes how each feature contributes to the model’s predictions. The horizontal axis represents the SHAP value, indicating whether a feature increases or decreases the predicted solar power output. The colour scale reflects the actual feature values, with red representing higher values and blue representing lower ones.

Figure 3.

The SHAP summary plot illustrates feature importance in the XGBoost model.

Solar irradiance shows the largest spread of SHAP values, confirming that variations in irradiance strongly influence the model output. Higher irradiance values consistently push predictions upward, while low irradiance values decrease them. Soil temperature at 10 cm depth exhibits a similar trend, reinforcing its importance as an environmental indicator. Lower-ranked variables such as cloud height, local pressure, and rainfall show SHAP values clustering near zero, indicating negligible influence on prediction accuracy. This visualization clearly distinguishes impactful predictors from weak ones, supporting the decision to adopt a minimal-feature Transformer model.

To validate the minimal feature approach, an ablation study was conducted using four input configurations: (i) irradiance only, (ii) temperature only, (iii) irradiance + temperature, and (iv) irradiance + temperature + historical power. The results show that irradiance alone provides stronger predictive ability (MAE 2.00) compared with temperature alone (MAE 2.66), confirming that temperature contributes less directly to short-term power fluctuations. Combining irradiance and temperature improves accuracy (MAE 1.91), indicating complementary information between the two variables. The best performance is achieved when historical power is added (MAE 1.68), demonstrating that recent power output carries important temporal information not fully captured by environmental variables alone. These findings confirm that each variable contributes uniquely, and the selected minimal feature set (solar irradiance and soil temperature at 10 cm depth) is justified while historical power further enhances forecasting performance.

3.3. Feature Importance Analysis

Solar power generation is primarily influenced by environmental factors that determine how much energy can be captured and converted into electricity [58]. Among these factors, solar irradiance and soil temperature at 10 cm depth are the two most significant contributors. Solar irradiance represents the amount of sunlight energy reaching the surface, directly affecting the photovoltaic (PV) system’s ability to generate power [59]. The stronger the solar irradiance, the more energy is absorbed by the solar panels, leading to higher power production. However, the efficiency of this energy conversion is also dependent on temperature, as higher temperatures tend to reduce the efficiency of PV cells. By focusing on these two variables, the model simplifies feature selection while retaining the most essential information needed for accurate predictions. Solar irradiance is the fundamental driver of solar power generation. It determines the available energy input for a solar panel system and is influenced by factors such as cloud cover, atmospheric conditions, and seasonal changes. During peak sunlight hours, when irradiance levels are highest, power generation reaches its maximum capacity. Conversely, during cloudy or night conditions, irradiance drops significantly, leading to a corresponding decrease in energy production. In solar forecasting, capturing irradiance trends allows models to anticipate daily and seasonal variations, ensuring that predictions align with real-world fluctuations in energy availability. By including solar irradiance as an input feature, the Transformer model learns to establish a strong correlation between light intensity and power output, making it a crucial predictor of future generation levels.

While irradiance dictates how much energy is available, temperature [60] influences how efficiently this energy is converted into electricity. Solar panels experience efficiency losses as temperature increases due to the inherent properties of semiconductor materials used in photovoltaic cells. Most solar panels have a negative temperature coefficient, meaning that for every degree Celsius increase in temperature, the power output of panel decreases by a certain percentage. This is the reason that excessive heat increases the resistance of the solar cells, leading to lower voltage and reduced efficiency. By incorporating temperature as an input variable, the Transformer model accounts for these efficiency losses, allowing it to make more precise power generation predictions under varying weather conditions. Without temperature as a factor, a model might overestimate power output during high-irradiance conditions, failing to account for heat-induced efficiency drops. By selecting only solar irradiance and soil temperature at 10 cm depth as input features, the model achieves an optimal balance between prediction accuracy and computational efficiency. Unlike traditional multivariate models that incorporate numerous meteorological variables, this streamlined approach reduces complexity while maintaining high predictive performance. The model effectively captures the core dependencies that drive solar power production, ensuring robust forecasting across different environmental conditions. Additionally, reducing the number of features minimizes the risk of overfitting, leading to a model that generalizes well to unseen data. This demonstrates that a minimal yet well-chosen feature set can achieve state-of-the-art performance in solar forecasting, reinforcing the importance of intelligent feature selection in deep learning applications for renewable energy management.

4. Transformer-Based Solar Forecasting Model

The Transformer model [61] is a deep learning architecture originally introduced for natural language processing (NLP) tasks [62], however it has been widely adopted for time-series forecasting due to its ability to efficiently capture long-term dependencies. Unlike traditional sequence-based models such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, which process data sequentially, the Transformer model utilizes a self-attention mechanism to weigh the importance of different time steps in a sequence simultaneously. This allows the model to learn complex temporal patterns without being constrained by the limitations of sequential processing, making it particularly effective for handling long time-series data where historical dependencies influence future predictions. Compared to traditional deep learning models like RNNs, LSTMs, and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs), the Transformer model has several key advantages. RNNs and their variants process time-series step by step, meaning that long-term dependencies can be difficult to capture due to the vanishing gradient problem. LSTMs and GRUs improve on this by introducing gates that help retain information over longer time spans, but they still suffer from computational inefficiencies when dealing with very long sequences. In contrast, the Transformer model processes the entire sequence in parallel, allowing it to learn relationships between different time points more effectively. This significantly reduces training time and allows the model to leverage global dependencies in time-series data, which is crucial for accurate forecasting.

Another major advantage of the Transformer model is its scalability and interpretability. Since it does not rely on sequential recurrence, it can handle large time-series datasets more efficiently than LSTMs and GRUs, which struggle with increasing sequence lengths. The self-attention mechanism in Transformers assigns varying levels of importance to different time steps, making it easier to interpret which past observations contribute most to future predictions. This is particularly beneficial in solar power forecasting, where energy generation is influenced by multiple interrelated temporal factors such as solar irradiance and soil temperature at 10 cm depth fluctuations. As a result, the Transformer model not only achieves higher forecasting accuracy but also provides greater insight into how past data influences future predictions, making it a powerful alternative to traditional time-series models.

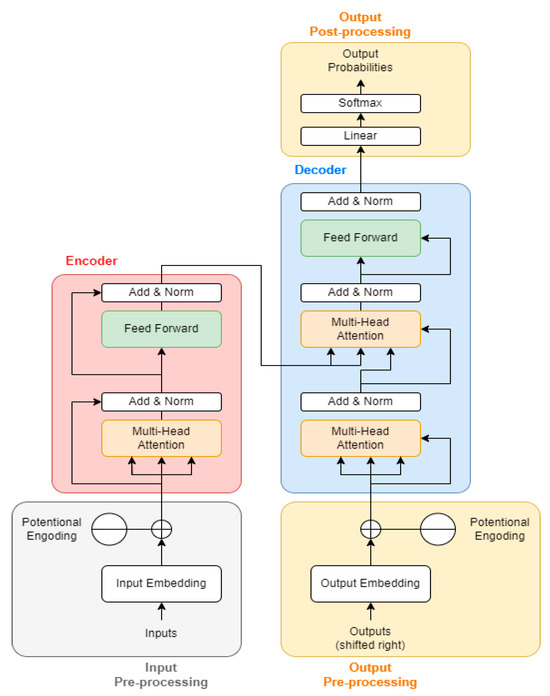

4.1. Model Architecture

The Transformer model used in this study was configured with a compact architecture suitable for hourly solar power forecasting. The model includes two Transformer encoder blocks, each consisting of a 128-dimensional head size, two attention heads, and a feed-forward dimension of 2. The encoder blocks apply Layer Normalization, Multi-Head Attention, and a lightweight feed-forward network, followed by residual connections. A global average pooling layer is applied before passing the output to an MLP consisting of a 64-unit dense layer and a final regression layer.

Hyperparameters were tuned experimentally by evaluating different combinations of head sizes (64–256), number of attention heads (1–4), feed-forward dimensions (2–16), number of Transformer blocks (1–4), and dropout rates (0–0.3). The final configuration was selected based on validation loss performance and computational efficiency. A dropout rate of 0.1 was used for both attention and MLP layers to reduce overfitting. Optimization was performed using the RMSprop optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.01 and ReduceLROnPlateau for adaptive learning-rate scheduling. Early stopping with patience of 200 epochs was applied to prevent overfitting and ensure stable convergence.

Transformer model was developed for solar power forecasting using a minimal set of input features. The input dataset consists of two meteorological variables solar irradiance and temperature pre-selected based on their high importance scores determined using SHAP with XGBoost (Section 3). To account for temporal dependencies, the model also includes the past power generation value as an additional input (x36).

The data were structured using a sliding window approach with a window length of five hours, allowing the model to use data from the previous five-time steps to predict the power output one hour ahead. This approach enables the model to capture short-term variations in weather and their effects on solar generation.

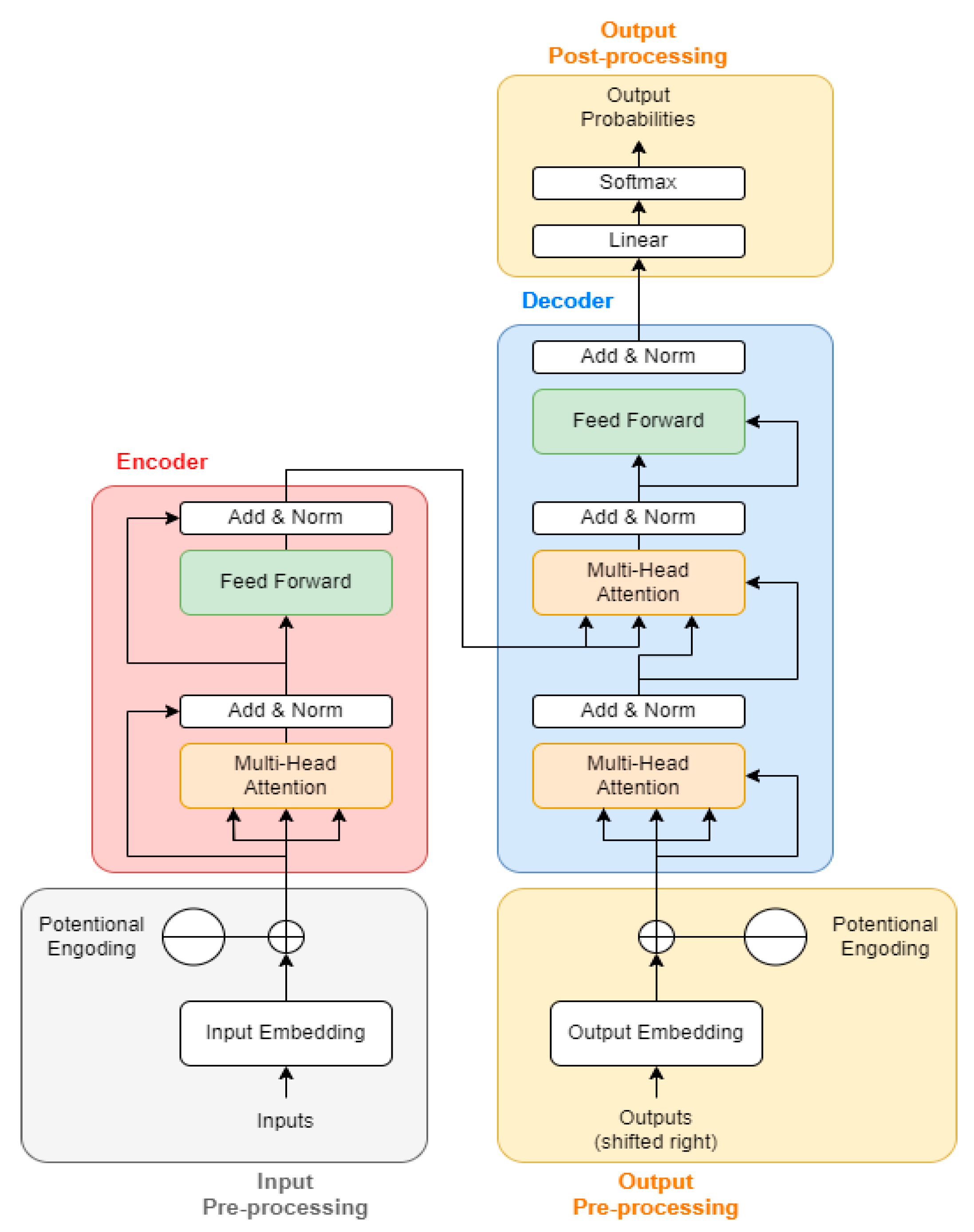

Unlike traditional recurrent architectures such as LSTM or GRU, which process data sequentially, the Transformer processes all time steps in parallel, allowing it to efficiently learn relationships across time. This parallelism enables faster computation and better modeling of both short-term fluctuations and long-term trends in solar power generation. The Transformer architecture consists of several main components: input embeddings, multi-head self-attention, positional encoding, feed-forward layers, and an output layer. The model structure can be seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Transformer Architecture [63].

4.2. Implementation of Transformer Model

The Transformer utilizes a self-attention mechanism to evaluate the relative importance of time steps within the input sequence [54]. Unlike SHAP, which identifies which features are most important, the self-attention mechanism determines which past observations contribute most to the next-hour prediction. This enables the model to focus on critical historical patterns while maintaining efficiency in processing sequential data. The self-attention mechanism is defined in Equation (2).

where , , and are learned representations of input sequences. The softmax function ensures that the sum of attention scores is 1. stabilizes gradients during training.

A key challenge with Transformers is that they do not have an inherent sense of sequence order, unlike recurrent architectures. To address this, positional encoding is used to provide information about the order of time steps in the input sequence. The positional encoding mechanism introduces sinusoidal functions that assign unique patterns to each time step, ensuring that the model understands their relative positioning. This allows the Transformer to effectively capture temporal patterns without relying on explicit recurrence. The positional encoding function is defined in Equations (3) and (4).

where represents the position of the time step and is the dimensionality of the embedding. By encoding positional information directly into the input representation, the model can learn dependencies across different time steps without requiring sequential processing, making it more scalable and computationally efficient.

In addition to self-attention and positional encoding, the Transformer incorporates feed-forward layers that refine the learned representations and introduce non-linearity [64]. Each time step in the sequence is passed through a fully connected feedforward network (FFN), which consists of multiple dense layers with activation functions such as ReLU [65]. The ReLU activation enables the model to learn complex, nonlinear relationships between the meteorological inputs and power generation output. The standard feedforward network is derived in Equation (5).

, are learned weight matrices. , are biases and the ReLU activation function introduces non-linearity.

The combination of self-attention and feedforward layers ensures that the model captures both global dependencies across time and local patterns in the data, making it well-suited for applications where historical trends influence future predictions. In this study, the model receives input sequences composed of solar irradiance, soil temperature at 10 cm depth, and past power generation values collected over five consecutive hours. These time-series inputs allow the Transformer to learn how fluctuations in environmental conditions affect subsequent power output. The final component of the Transformer model is the output layer, which generates the predicted power generation value for the next time step. The output is typically a single numerical value corresponding to future solar power output, and a linear layer is applied to reduce the output to the desired dimension, as represented in Equation (6):

Overall, the Transformer effectively models the temporal dynamics of solar irradiance, soil temperature at 10 cm depth, and power generation data. Its ability to capture both short- and long-term dependencies enables accurate next-hour solar power forecasting under varying environmental conditions.

4.3. Training and Validation

To ensure that the model was evaluated on truly unseen data, a temporal split was applied to preserve chronological order. Earlier observations were assigned to the training portion of the dataset, and later observations were reserved exclusively for validation and testing. This structure prevents future information from influencing the learning process and reflects a realistic deployment scenario in which forecasts are generated for time periods that were not available during model development. The temporal ordering also ensures that model behavior is evaluated under operational conditions that mimic real-world forecasting tasks, rather than relying on randomly shuffled samples that could introduce information leakage.

Before training, the dataset was divided into a 70% training set and a 30% validation set while preserving the temporal order of the observations. This approach ensures that earlier data are used for model learning, whereas later data are reserved for evaluation, preventing the mixing of past and future information and providing a realistic assessment of forecasting performance.

The dataset was standardized using StandardScaler (Python 3.11, PyTorch 2.2.2, NumPy 1.26, and Scikit-Learn 1.4), and all input variables were reshaped into the required time-series format. The Transformer model was trained using the Adam optimizer, with Mean Squared Error (MSE) [66], as the loss function to quantify the difference between predicted and actual values. Throughout training, both training and validation losses were monitored to track learning progress. An increase in validation loss alongside a decrease in training loss was interpreted as a sign of overfitting, in which case techniques such as early stopping or regularization can be applied.

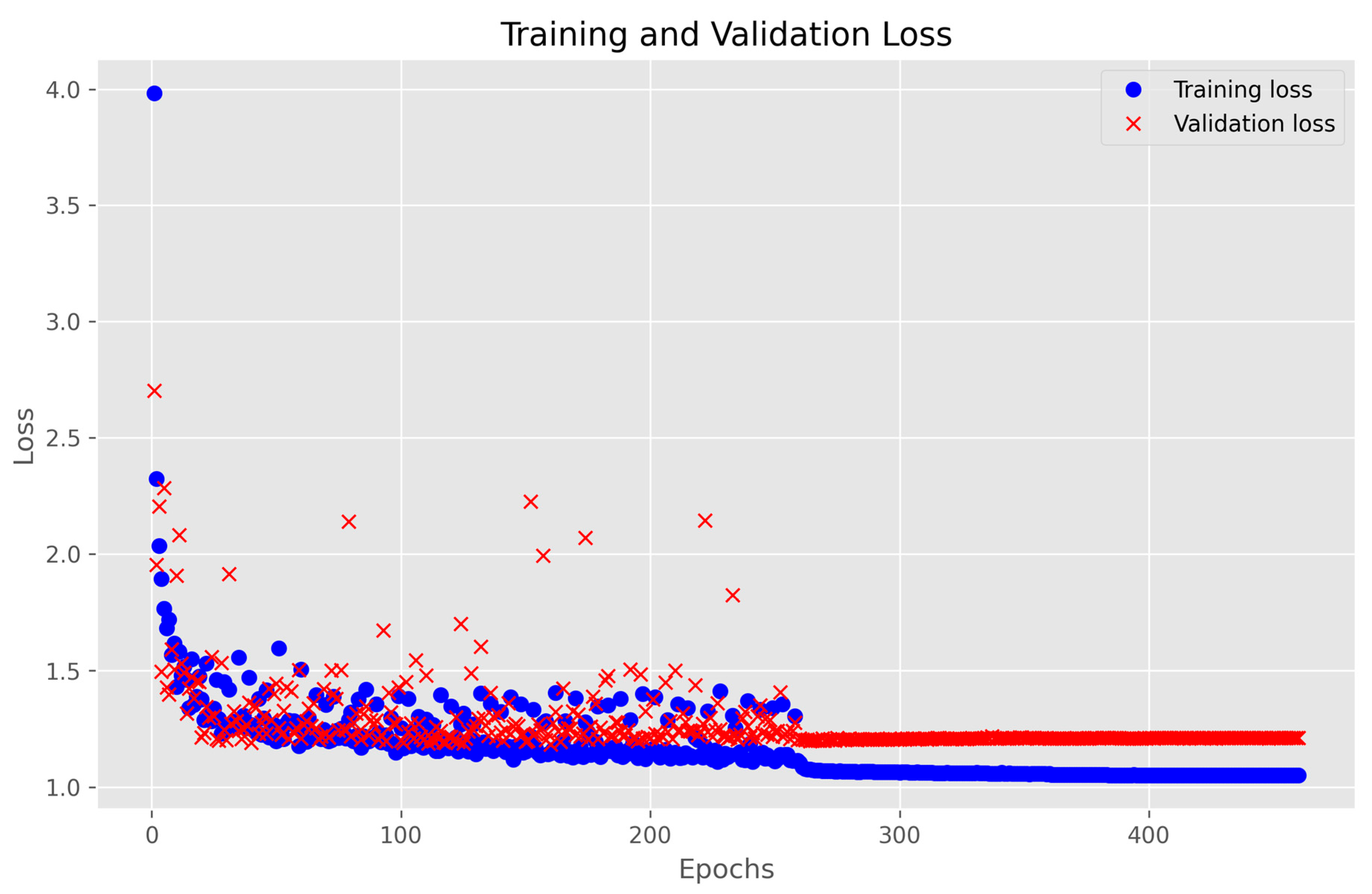

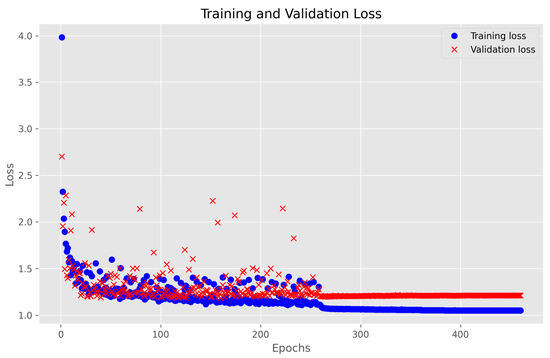

For validation, the reserved dataset was used to evaluate how well the model performs on unseen data. The data were formatted into the same time-series structure before being passed into the model for inference. The final trained model was saved for potential future deployment, and loss curves were visualized to assess convergence behaviour and determine whether additional hyperparameter tuning might be needed. Figure 5 illustrates the evolution of training and validation performance across epochs.

Figure 5.

Training and Validation Loss Curve of the Transformer Model.

The graph presents the training loss (blue dots) and validation loss (red crosses) as the model learns to minimize the error between predicted and actual solar power values. At the beginning of training, both the training loss (blue dots) and validation loss (red crosses) are relatively high, indicating that the model is still adjusting its parameters. However, there is a sharp decline in loss within the first 50 epochs, suggesting that the model quickly learns meaningful patterns from the input data. This steep decrease reflects the model’s ability to minimize the error between predicted and actual solar power values efficiently.

As training progresses between 50 and 300 epochs, the loss continues to decline, though at a slower rate. The training and validation losses remain closely aligned, which indicates that the model is generalizing well to unseen data without overfitting. This is a crucial aspect of time-series forecasting, where overfitting could lead to poor performance on new environmental conditions. The slight fluctuations in validation loss during this phase are expected, as the model encounters different data distributions across batches. In the final phase (300–500 epochs), the training loss stabilizes around 1.0, signalling that the model has converged, and additional epochs result in only minimal improvements. The validation loss remains consistent with the training loss, further confirming that the model is not overfitting. If the validation loss had started increasing while the training loss continued decreasing, it would have indicated overfitting, requiring techniques such as early stopping or dropout regularization. However, the alignment of both losses suggests that the model is well-optimized for solar power prediction.

In addition, the behaviour of the self-attention mechanism was examined to understand which temporal patterns the model prioritizes during training. The analysis shows that the Transformer assigns higher attention to hours immediately preceding rapid changes in solar output, such as early-morning ramp-up, late-afternoon decline, and short-term fluctuations caused by cloud movement. This indicates that the model relies more heavily on recent variations rather than uniformly weighting the full input window. These patterns help explain how the model identifies turning points in power generation and support its ability to generate stable short-term forecasts.

To evaluate model robustness under different climatic patterns and prevent temporal leakage, a seasonal cross-validation analysis was conducted. The dataset was divided into four non-overlapping seasonal subsets Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter and the model was trained on three seasons while the remaining season served as the test set. The results show that forecasting accuracy varies moderately across seasons: Spring (MAE 1.3166, RMSE 1.8264), Summer (MAE 1.3738, RMSE 1.9299), Fall (MAE 1.1544, RMSE 1.5881), and Winter (MAE 1.2541, RMSE 1.7086). Performance is strongest in Fall and Winter, while summer shows slightly higher error due to increased irradiance variability during monsoon periods. This evaluation confirms that seasonal factors influence model behavior, and the transformer architecture maintains stable performance across all seasonal conditions.

4.3.1. Prediction Performance Evaluation

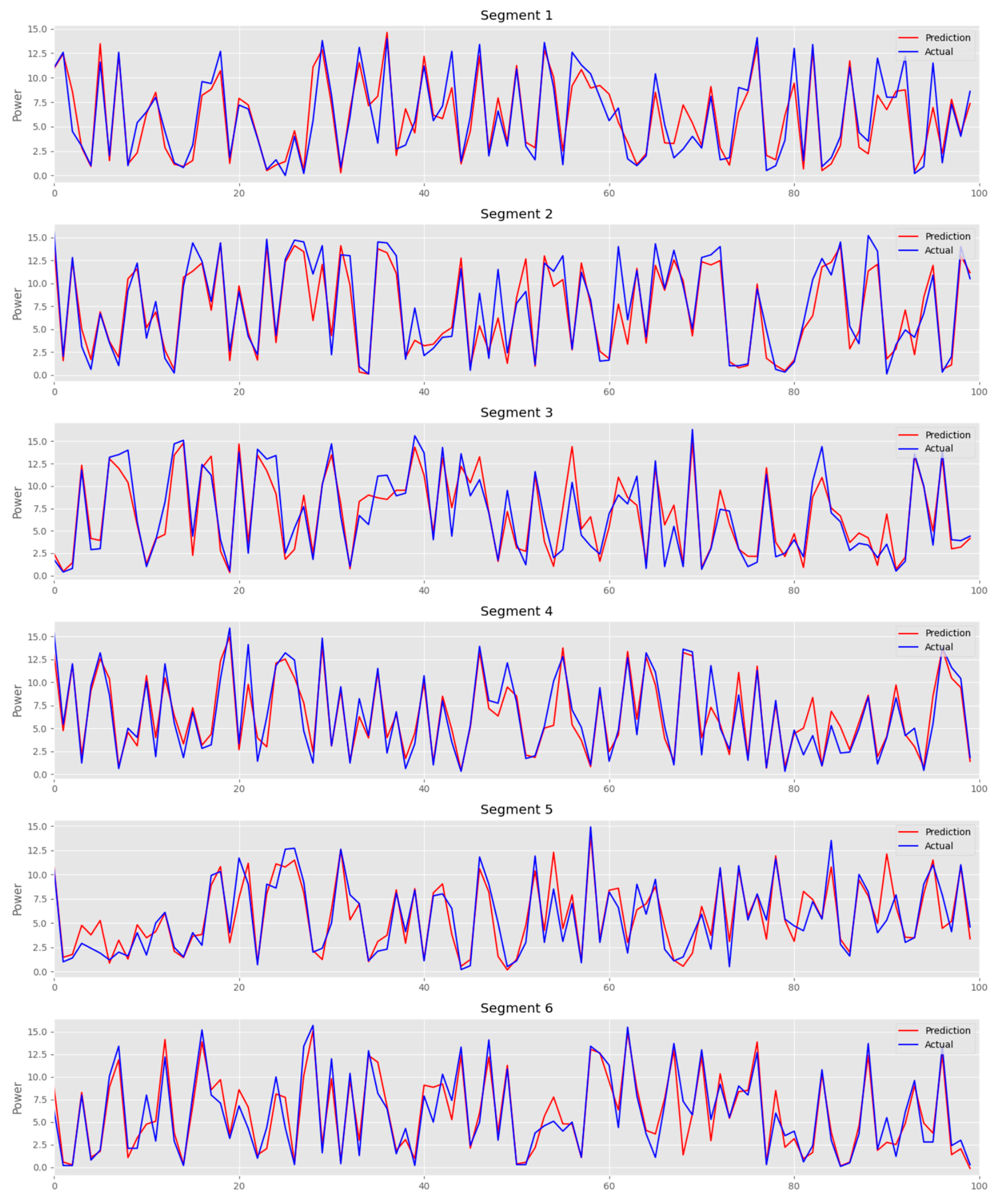

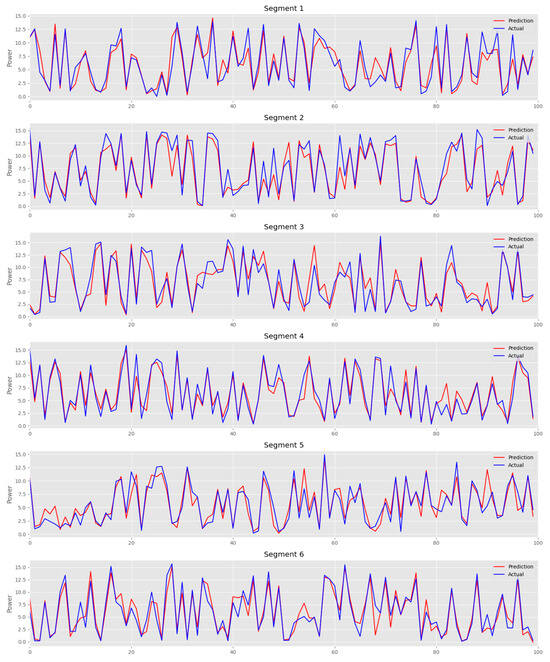

The performance of the Transformer model is evaluated using Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) as key metrics [67]. The model achieved an RMSE of 1.619, indicating that, on average, its predictions deviate by 1.62 units from the actual observed power values. This measure accounts for both the magnitude and variance of errors, making it a reliable indicator of forecasting accuracy. Additionally, the MAE is calculated as 1.1325, reflecting the model’s ability to minimize absolute prediction errors. The low RMSE and MAE values confirm that the Transformer-based approach effectively captures trends in solar power generation while maintaining a high level of precision. Figure 5 presents a visual comparison between predicted solar power values (red line) and actual observed values (blue line) across multiple time windows. Each subplot represents a different segment of the dataset, demonstrating how the model performs under varying conditions.

The strong alignment between the predicted and real values in most cases indicates that the model accurately captures both seasonal variations and short-term fluctuations in power output as shown in Figure 6. The ability to track peaks and troughs in energy production highlights the model’s effectiveness in learning temporal dependencies and generating accurate forecasts. Despite the overall strong performance, minor deviations are visible in certain time intervals, particularly during rapid power fluctuations. These discrepancies may be attributed to abrupt environmental changes, such as cloud cover, temperature shifts, or atmospheric variations, which are not fully captured by the selected input features. However, the consistency of predictions across different time windows suggests that the model generalizes well and is not overfitting to the training data, ensuring stable performance on unseen observations.

Figure 6.

Predicted vs. Actual Solar Power Generation (Segmented Time Windows).

In addition, the model’s performance may be more limited during rare but impactful events such as storms, heavy pollution episodes, or atypical cloud cover patterns. These conditions often cause sudden and irregular changes in solar irradiance that cannot be fully represented using only irradiance and soil temperature at 10 cm depth as input variables. Since such events involve additional atmospheric factors, including aerosol concentration, cloud optical thickness, and wind-driven weather shifts, the model may produce larger errors during these periods. This highlights that while the minimal two-feature configuration performs well under typical conditions, performance during extreme or rapidly changing events should be interpreted with caution.

Moreover, to evaluate the Transformer model in a broader forecasting context, additional experiments were performed using several classical statistical and machine-learning benchmarks. These models Linear Regression, Random Forest, XGBoost, LightGBM, k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), winter (SVR), and a shallow Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) serve as lightweight alternatives to traditional time-series methods such as ARIMA, particularly when exogenous variables are included. Evaluating the Transformer against these simpler baselines provides a clearer understanding of the performance gain achieved by the proposed approach.

For a fair comparison, all benchmark models, MAE values ranged from 1.22 to 1.34, and RMSE values ranged from 1.74 to 1.85. SVR and MLP yielded the strongest baseline results (MAE ≈ 1.23), but the Transformer model achieved a lower MAE of 1.1325 and an RMSE of 1.619, outperforming every classical model. These findings demonstrate that the Transformer not only surpasses other deep learning architectures but also consistently outperforms widely used statistical baselines. This confirms that the Transformer is more effective at capturing nonlinear temporal dependencies in solar power generation, even when trained on a minimal feature set consisting only of irradiance and soil temperature at 10 cm depth.

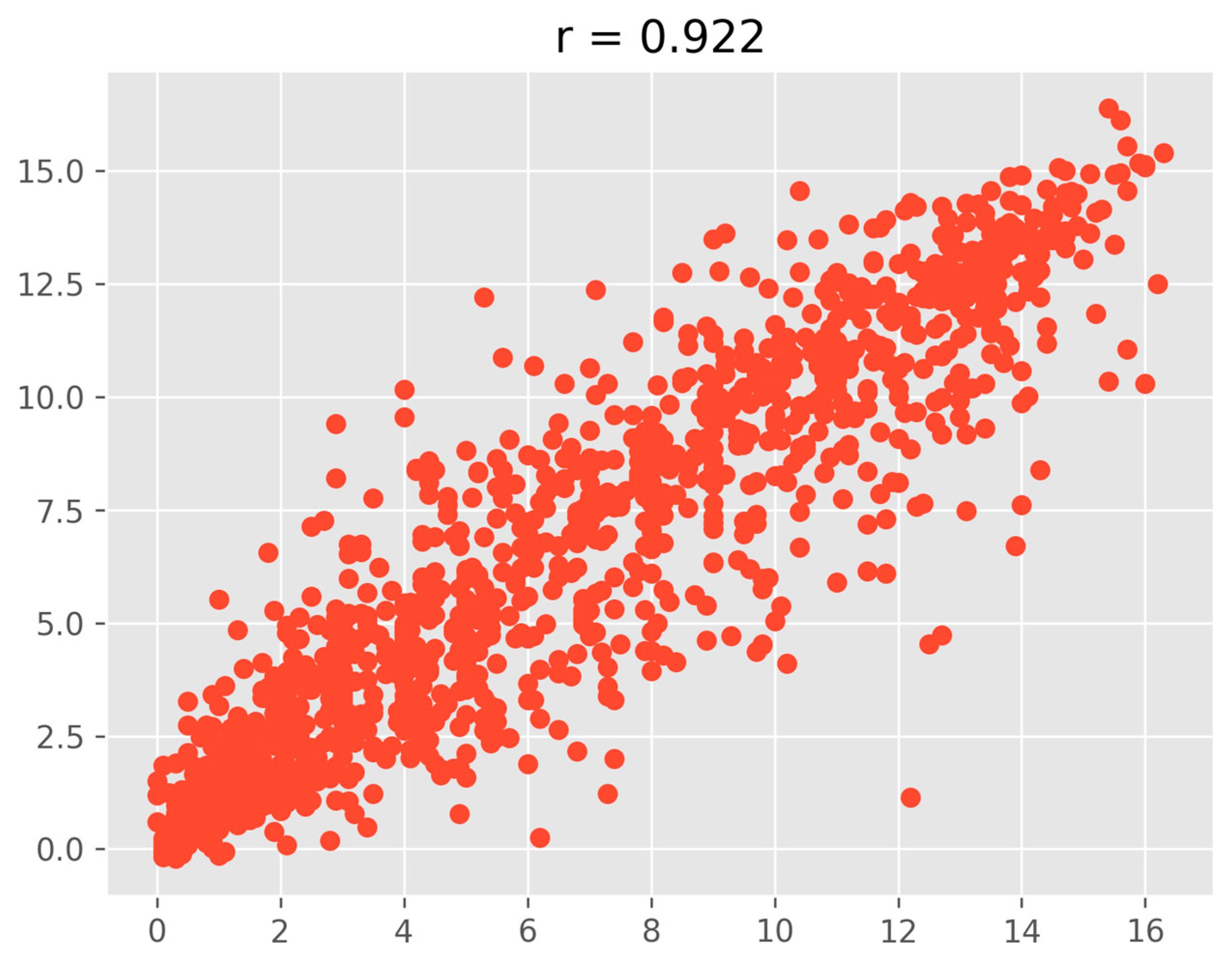

4.3.2. Correlation Analysis and Model Performance Evaluation

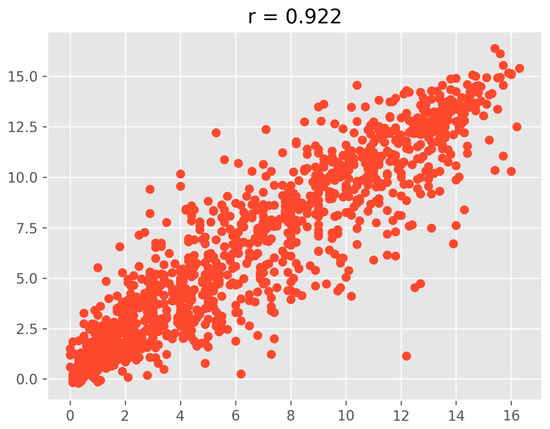

Analyzing the correlation between predicted and actual solar power values provides insight into the ability of the model to capture the underlying patterns in power generation. A strong correlation indicates that the model effectively learns temporal dependencies and generalizes well across different conditions. By measuring this relationship, it is possible to assess how accurately the Transformer model predicts solar power generation under varying environmental factors. A high correlation suggests that the model’s predictions align closely with real-world variations, making it a reliable tool for renewable energy forecasting and power grid optimization. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r = 0.922) quantifies the linear relationship between the predicted and actual values [68]. This high correlation indicates a strong positive relationship, meaning that as actual solar power generation increases or decreases, the predicted values follow a similar trend. A correlation value close to 1.0 suggests that the model successfully captures power fluctuations with minimal deviation. This result demonstrates that the model effectively learns key influencing factors without excessive noise, reinforcing its suitability for time-series forecasting.

To further validate the model’s performance, the R2 score (coefficient of determination) was computed, resulting in a value of 0.922 as show in in Figure 7. This means that 92.2% of the variance in solar power generation is explained by the model’s predictions, highlighting its effectiveness in minimizing errors. Additionally, the adjusted R2 score of 0.849 accounts for the number of predictor variables, ensuring that the model’s accuracy is not artificially inflated. The combination of a high Pearson correlation and R2 score confirms that the Transformer-based approach delivers accurate and generalizable solar power forecasts. Figure 7 presents a scatter plot comparing predicted and actual solar power values, visually representing the correlation. The clustering of points along the diagonal axis suggests that most predictions closely align with the actual values.

Figure 7.

Scatter Plot of Predicted vs. Actual Solar Power Values.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This study demonstrated that a Transformer model using only solar irradiance and soil temperature at 10 cm depth as input variables achieved an MAE of 1.1325, closely aligning with the multivariate Transformer model from the previous study (MAE 1.14). This confirms that a small set of highly relevant features can still provide meaningful and accurate predictions. The ability of the Transformer to capture temporal dependencies from only two variables highlights its strength in modeling nonlinear dynamics in solar power generation.

To contextualize the model’s performance, additional experiments were conducted using well-established machine learning benchmarks, including Linear Regression, Random Forest, XGBoost, LightGBM, KNN, Support Vector Regression, and a shallow MLP. The baseline models produced MAE values ranging from 1.22 to 1.34, all of which were outperformed by the Transformer. These results further validate the Transformer’s superiority over both deep learning counterparts and classical statistical models on the same minimal feature set.

Quantitative ablation analysis confirmed the contribution of each variable. Using irradiance alone yielded an MAE of 2.00, temperature alone produced an MAE of 2.66, and combining the two reduced the MAE to 1.91. Incorporating historical power improved performance further to an MAE of 1.68, demonstrating the complementary roles of environmental and temporal features. Seasonal evaluation also revealed stable behaviour, with MAE values of 1.3166 in Spring, 1.3738 in Summer, 1.1544 in Fall, and 1.2541 in Winter, showing that the Transformer maintains reliable predictions across varying climatic periods.

Although the model performs well with irradiance and soil temperature at 10 cm depth alone, several meteorological factors such as wind speed, cloud cover, and humidity were not included. Incorporating a small number of additional features may further reduce forecasting errors and improve robustness during abrupt weather fluctuations. Moreover, the three-year dataset does not capture long-term climatic cycles, suggesting that extending the dataset across additional years, regions, and seasonal conditions would provide a more comprehensive assessment of the model’s adaptability.

The intermittency of solar energy also highlights the importance of thermal energy storage systems, which help stabilize short-term fluctuations in power generation. Previous work shows that integrating forecasting models with thermal storage strategies improves system reliability and operational flexibility [69]. Considering such integration may provide additional insights into how short-term predictions support energy management in practical deployments.

Although the results indicate strong forecasting behavior under the conditions studied, the findings may not fully generalize beyond the specific location and climate represented in the dataset. The data reflects the environmental characteristics of a single region and a limited multi year period, which may not capture broader variability in solar patterns across different geographic environments. Extending the analysis to additional sites with diverse weather conditions and expanding the temporal range of the dataset would provide a more robust evaluation of the model’s adaptability.

Future research may also explore hybrid modelling strategies that combine Transformers with ensemble methods or satellite-based environmental data, which may enhance performance under irregular or rapidly changing weather patterns. In addition, adaptive feature-selection mechanisms that adjust input variables dynamically in real time may help improve generalization under diverse meteorological conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K., M.S.S. and J.-H.S.; methodology, M.S.S., D.K. and J.-H.S.; software, M.S.S. and D.K.; validation, M.S.S.; formal analysis, M.S.S. and J.-H.S.; investigation, M.S.S. and D.K.; resources, M.S.S.; data curation, D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S.S., D.K. and J.-H.S.; visualization, M.S.S. and D.K.; supervision, J.-H.S.; project administration, J.-H.S.; funding acquisition, J.-H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) grant funded by the Korea government (MOTIE) (RS-2025-00423446, Demonstration of Technology for Efficiency Improvement in Entire Cycle of Manufacturing Processes of Root industries for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises).

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) and the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE) of the Republic of Korea for their support through the funded project. Additional appreciation is extended for any administrative and technical assistance received during the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, Z.; Gao, X.; Huang, X.; Xie, Y.; Gao, J.; Yang, X.; He, Q. Evaluation on Solar-Biogas Heating System for Buildings: Thermal Characteristics and Role of Heat Storage Sectors. Appl. Energy 2025, 390, 125817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeeun, K.; Tuan, L.Q.; Na, O.Y.; Whan, A.J. Extraction of Scandium from Coal Ash in Korea: Potential to Secure Supply Chain for Nuclear and Small Modular Reactors Feedstock. J. Energy Eng. 2024, 33, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Park, Y.; Smith, T.M.; Kim, T.; Park, H.-S. High-Resolution Environmentally Extended Input–Output Model to Assess the Greenhouse Gas Impact of Electronics in South Korea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 2107–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramochi, T.; Nascimento, L.; Moisio, M.; den Elzen, M.; Forsell, N.; van Soest, H.; Tanguy, P.; Gonzales, S.; Hans, F.; Jeffery, M.L. Greenhouse Gas Emission Scenarios in Nine Key Non-G20 Countries: An Assessment of Progress toward 2030 Climate Targets. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 123, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, B.-K.; Chung, J.-B.; Song, C.-K. National Climate Change Governance and Lock-in: Insights from Korea’s Conservative and Liberal Governments’ Committees. Energy Strategy Rev. 2023, 50, 101238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessa, R.J.; Trindade, A.; Miranda, V. Spatial-Temporal Solar Power Forecasting for Smart Grids. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2014, 11, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramedani, Z.; Omid, M.; Keyhani, A.; Shamshirband, S.; Khoshnevisan, B. Potential of Radial Basis Function Based Support Vector Regression for Global Solar Radiation Prediction. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelin, D.; Manikandan, D.V. Optimal Operation of Power in Renewable Energy by Using Prediction in Recurrent Neural Network. Int. J. Innov. Res. Comput. Commun. Eng. 2015, 33, 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, M.; Seung, K.H.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, J.-M.; Hong, S.; Lee, E.H. Long-Term Solar Radiation Forecasting Using a Deep Learning Approach-GRUs. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 8th International Conference on Advanced Power System Automation and Protection (APAP), Xi’an, China, 21–24 October 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 917–920. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Chi, Y.; Xiao, L. Solar Power Generation Forecast Based on LSTM. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 9th International Conference on Software Engineering and Service Science (ICSESS), Beijing, China, 23–25 November 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 869–872. [Google Scholar]

- Pospíchal, J.; Kubovčík, M.; Dirgová Luptáková, I. Solar Irradiance Forecasting with Transformer Model. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]