Abstract

The hybrid energy storage system (HESS) significantly improves the dynamic response and energy utilization efficiency of the propulsion system in fuel cell vessels while maintaining the stability of the power grid. To address the issue of inaccurate power allocation and unreasonable capacity configuration caused by modal aliasing during power decomposition, this article innovatively proposes a power distribution method for hybrid energy storage systems. First, the Multi-Verse Optimizer (MVO) is used to optimize Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) in order to address the issue of VMD being highly dependent on parameter selection. Then, power is decomposed twice to resolve the modal aliasing problem associated with single decomposition, achieving a more accurate power breakdown and providing a more stable power output. Finally, the decomposed powers are cross-allocated: low frequencies are assigned to lithium batteries that can provide long-term stable energy supply, while high frequencies are allocated to supercapacitors capable of delivering short-term efficient energy supply. The simulation results indicate that the MVO-CVMD method proposed in this paper effectively addresses the modal aliasing problem, enhances the accuracy of power decomposition, and reduces the cost of capacity configuration.

1. Introduction

The International Maritime Organization’s MEPC 80 session endorsed the 2023 GHG Reduction Strategy, introducing more stringent emission control objectives for global shipping [1]. Hybrid vessels equipped with battery storage systems and optimized power management systems will help offset peak loads, improve engine response performance, reduce emissions and fuel consumption, and lower maintenance costs [2]. These vessels are increasingly being applied in the fields of offshore engineering ships, ro-ro ships, cruise ships, and shuttle tankers [3].

To respond to the increasingly stringent environmental protection requirements and mandatory emission reduction regulations globally, shipping companies in various countries are continuously promoting and expanding the application of green ship technologies in actual vessels [4]. Fuel cell vessels offer advantages such as low emissions and high efficiency, but their dynamic response is relatively slow, making it difficult to provide continuous and stable power. Therefore, an energy storage system is needed to address this issue. Lithium batteries have high energy density but lower power density and slow charge–discharge rates, capable of providing low-frequency power and stable power supply for extended periods [5]. In contrast, supercapacitors exhibit high power density and rapid charge–discharge capabilities, enabling them to deliver high-frequency power and short-term high-power compensation, despite their relatively low energy density [6]. To address the unstable and intermittent power output of fuel cell-powered vessels, a hybrid energy storage system (HESS) integrating lithium batteries and supercapacitors is implemented [7]. An optimal HESS configuration requires intelligent power allocation, where supercapacitors manage high-frequency transients and lithium batteries supply low-frequency steady-state power, achieving cost-effective, reliable, and sustainable operation.

Recent years have witnessed significant academic efforts worldwide addressing key challenges in hybrid energy storage systems, particularly regarding power allocation and capacity configuration, with notable progress being made in these research areas. Zhou et al. presents an Improved Low-Pass Filter (ILPF) to address the limitations of traditional Low-Pass Filters (LPFs), including phase-shift effects and charging state restrictions [8]. However, low-pass filtering can attenuate or completely eliminate high-frequency components, which may lead to a loss of high-frequency details in the signal. To effectively address the issue of high-frequency resolution loss caused by low-pass filtering, Abdulmawjood et al. proposes a new method that combines Wavelet Packet Transform (WPT) with Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) [9]. However, the performance of this method is highly dependent on the choice of wavelet basis and lacks universal selection criteria. The optimization Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm proposed by Pan et al. [10] and He et al. [11], the profit distribution mechanism based on the improved Shapley value suggested by Zhang et al. [12], and the EMD utilized by Li et al. all share a common disadvantage [13]: they rely on experience for parameter tuning. Additionally, there is the unavoidable issue of modal aliasing present during EMD. Regarding the issues with EMD, Liu et al. proposes Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD) as an adaptive signal processing method that can effectively overcome the modal aliasing deficiencies of EMD [14]. However, its decomposition performance still highly depends on parameter selection. To address the issue that decomposition performance is still highly dependent on parameter selection, Jin et al. proposed optimizing VMD using MVO [15]. By utilizing MVO to optimize the decomposition parameters of VMD, a universal selection criterion can be achieved; however, this approach only performed one decomposition of the signal, resulting in insufficient accuracy. Kirubadevi et al. proposed an optimal photovoltaic (PV) and battery energy storage system with a hybrid approach design for electric vehicle charging stations (EVCS) [16]. However, this system cannot operate in isolation. Based on the issues with traditional Low-Pass Filters (LPFs) in existing research, such as phase-shift effects and limitations related to charging states, as well as its inability to effectively handle high-frequency signals, and given that WPT and EMD are highly dependent on the selection of empirical parameters, this paper proposes a power distribution strategy for fuel cell ships with hybrid energy storage systems based on the MVO-CVMD algorithm. The MVO algorithm is used to adaptively optimize VMD parameters through two decompositions, leading to more accurate decomposition results. Subsequently, the powers obtained from decomposition are cross-allocated into high- and low-frequency components before being allocated to a HESS composed of supercapacitors and lithium batteries in order to provide more stable power to meet the power demands of load systems with a more precise power decomposition and lower capacity configuration costs.

The main research content of this article is as follows:

- The schematic diagram of the fuel cell ship HESS has been established.

- The proposed MVO-CVMD methodology enables effective power decomposition in hybrid energy storage systems.

- An optimal HESS configuration strategy is formulated, incorporating full lifecycle cost analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fuel Cell Ship HESS

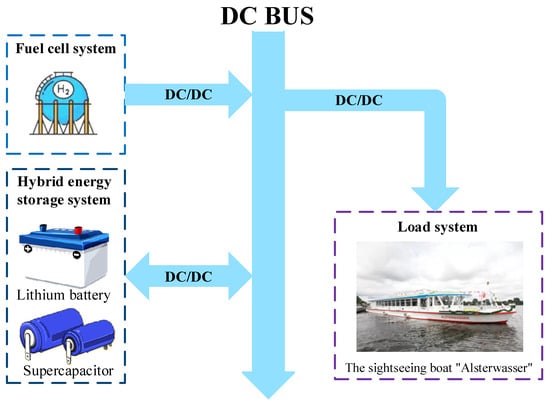

The HESS of fuel cell vessels primarily integrates three key components: a fuel cell stack, a lithium battery–supercapacitor HESS (hybrid energy storage system), and power distribution networks. The schematic diagram of this architecture is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The schematic diagram of the fuel cell ship hybrid energy storage system.

The DC power distribution system integrates the fuel cell array via a unidirectional DC/DC converter for bus voltage regulation. The lithium battery–supercapacitor HESS employs bidirectional DC/DC conversion for bus connection, while the load network is linked via a separate unidirectional converter.

2.2. Fuel Cell Model

Fuel cells electrochemically generate electricity via hydrogen–oxygen reactions, directly transforming chemical energy into electrical output. During this process, some losses cause a drop in output voltage and an increase in current [17]. The actual output voltage of the fuel cell, denoted as , is given by the following equation:

where is the nernst ideal voltage of the fuel cell, is the activation voltage losses, is the ohmic voltage losses, and is the concentration voltage losses.

The fuel cell stack is the core component of this system, and its operation is supported by auxiliary equipment. is generated by the redox reaction inside the stack. A portion of the power is directed to auxiliary equipment, such as compressor power and water pump power. The remaining power is transmitted to the DC bus through the converter, referred to as net output power [17].

2.3. HESS Model

When the output power of the fuel cell system exceeds the power required for load-side navigation, excess energy will be absorbed by the hybrid energy storage system for charging. Conversely, when under rapid acceleration conditions, if the output power of the fuel cell system cannot meet that required by the load system, the hybrid energy storage system will discharge its stored energy to maintain stable operation of the system [18].

where represents the load demand of the ship; is the power of the HESS; denotes the output power from the lithium battery; and refers to the output power from supercapacitors.

3. Power Allocation Strategy of HESS Based on MVO-CVMD Algorithm

Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) is an adaptive signal processing method, suitable for analyzing nonlinear and non-stationary signals [19]. However, EMD is prone to issues such as the emergence of spurious components and modal aliasing. Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD), proposed by Dragomiretskiy and Zosso [20], transforms the signal decomposition process into a mathematically constrained optimization problem through a variational optimization framework, overcoming the drawbacks of EMD.

3.1. VMD Principle

The VMD algorithm initially breaks down the target signal x into K intrinsic mode functions (IMFs) through modal decomposition. The corresponding constrained variational formulation can be expressed as:

where represents the various components of the IMF; represents the center frequency; and represents the impulse function [21].

The Lagrange multiplier and the penalty factor are used to solve for the optimal variational solution:

By iteratively solving the above equation using the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers, we can obtain the following:

The stopping result for iterative solving can be expressed as the following:

3.2. Use of Multi-Verse Optimizer Algorithm

MVO (Multi-Verse Optimizer) is a parameter optimization algorithm proposed by Mirjalili et al. in 2016 [22]. This method utilizes relevant rules of cosmology, where objects in each universe have different expansion rates, corresponding to the varying expansion rates of each universe. If the parameters of the VMD algorithm can be optimized and improved using MVO, this will be extremely beneficial for optimizing IMF components [14].

The MVO algorithm theory gradually approaches the optimal position in the search space by leveraging relevant cosmological rules. It has the advantage of being less affected by data distribution structures. The specific implementation process is as follows:

Due to the differing expansion rates of individuals, objects in the universe can be transferred through white holes and black holes.

where is the i-th universe and its normalized expansion rate and is a random number taken from [0, 1].

Without considering the size of the expansion rate, each universe establishes a wormhole with the currently optimal universe to exchange local objects.

where represents the -th dimension parameter of the -th universe and and are the upper and lower limits of that dimension parameter, respectively. Additionally, , and are random numbers taken from within [0, 1]. In the MVO algorithm, and are key parameters representing wormhole existence rate and travel distance rate, respectively. During optimization iterations, with changes in and values, a more precise global or local search can be achieved in optimal universes.

where represents the current number of iterations; is the maximum number of iterations; is the minimum value of which indicates the minimum probability of wormhole existence; refers to the maximum value of indicating the maximum probability of wormhole existence; and stands for ’s limiting parameter representing development precision in the algorithm.

3.3. MVO Optimization VMD Parameters

The performance of VMD is significantly influenced by two key parameters: the mode number and the penalty factor α. Early VMD studies determined values through empirical observation of center frequency distributions across IMF components, though this approach suffered from subjectivity and neglected optimization. Subsequent research demonstrated that employing optimization algorithms for parameter selection substantially enhances decomposition quality by simultaneously optimizing both and values.

This study employs the MVO fitness function to optimize VMD parameters . The fuzzy entropy value reflects the feature information abundance contained in the source signal. A larger sample fuzzy entropy value indicates that the original signal is more random and contains more useless information; conversely, a smaller value suggests that the signal is more regular and contains less useless information. The MVO optimization VMD parameter settings are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

MVO optimization VMD parameter settings.

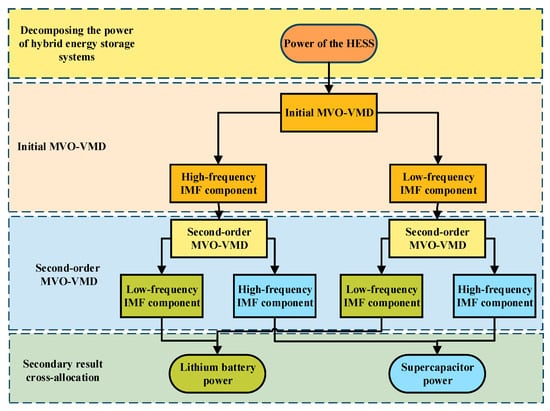

3.4. HESS Power Allocation Approach

The MVO-VMD method decomposes hybrid energy storage system power into frequency-ordered intrinsic mode functions (IMFs), where components are sequentially arranged from low to high frequencies. The high- and low-frequency boundary is determined based on the degree of modal aliasing to obtain high- and low-frequency components. This paper further performs a secondary decomposition of the frequency components obtained from the first decomposition to obtain individual modal components. Based on the spectral characteristics of components and energy storage devices after secondary decomposition, cross-distribution is performed. The battery storage system is designated for low-frequency power components, whereas supercapacitors handle high-frequency power distribution.

where denotes the cutoff frequency between high and low components in the initial VMD stage, and indicates the quantity of intrinsic mode functions produced during this primary decomposition phase.

where and represent the modal components after secondary decomposition; and indicate the low- and high-frequency components obtained from the high frequency of secondary decomposition; and and refer to the low- and high-frequency components derived from the low-frequency component of secondary decomposition. The flow of the power allocation strategy is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Power allocation strategy flowchart.

To enhance power distribution precision, the modal components obtained from secondary MVO-VMD undergo cross-allocation. Given their distinct characteristics, lithium batteries—functioning as energy storage devices with limited power density—are assigned low-frequency power components. Conversely, supercapacitors—serving as power-oriented devices with constrained energy density—receive high-frequency power components.

4. HESS Capacity Design

The HESS is typically composed of power devices such as supercapacitors and energy devices like lithium batteries [16]. Inadequate capacity may result in power supply disruptions, whereas excessive capacity could introduce unnecessary redundancy expenses.

Considering economic and technical factors including system costs and conversion losses, the annual operational cost objective function for the HESS is formulated using the following equations:

where represents the total annual operating cost of the HESS; indicates the annual capital expenditure for battery systems; refers to the annual maintenance cost for batteries; signifies the annual comprehensive cost of supercapacitors; denotes the annual maintenance cost for supercapacitors; f represents the discount rate; , , and refer to the unit power cost, unit capacity cost, and operating maintenance costs of batteries, respectively; and , , and respectively correspond to the unit power cost, unit capacity cost, and operation and maintenance costs of supercapacitors [23].

where is 5%, and represent the service life of the equipment, which is taken to be 20 years [23].

5. Case Analysis

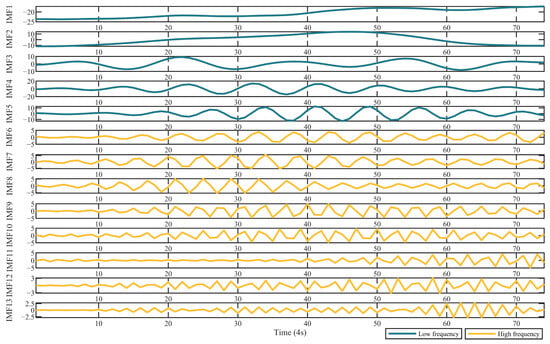

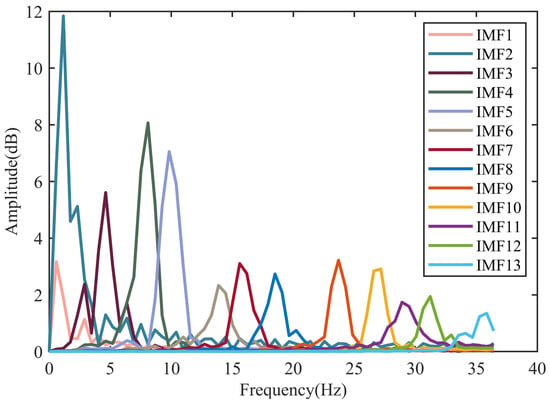

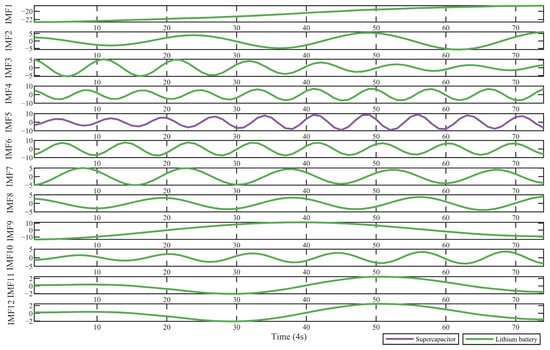

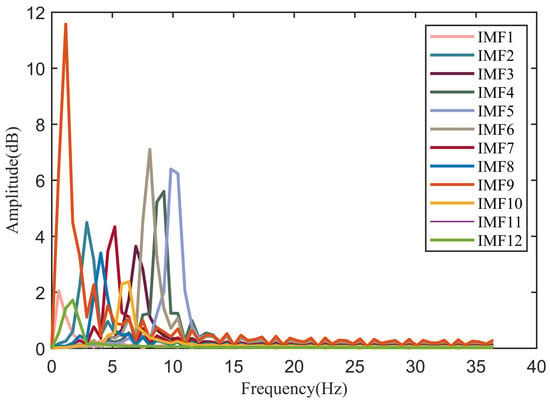

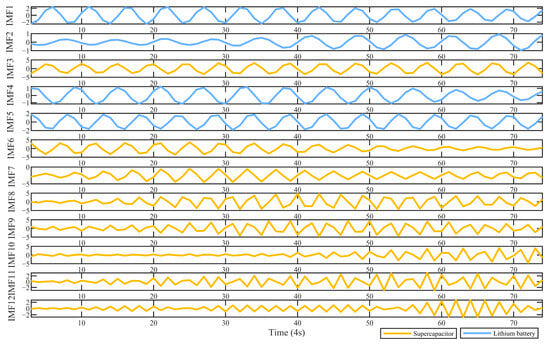

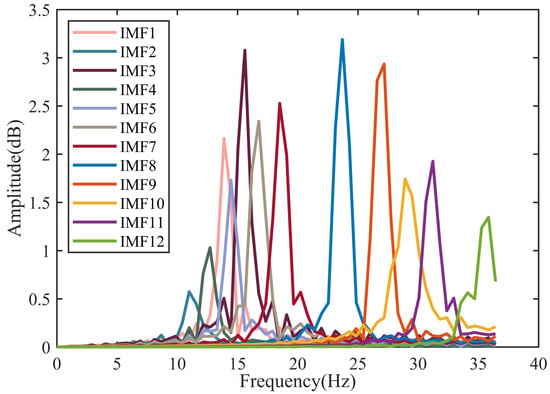

This article takes the typical voyage of the “Alsterwasser” cruise ship as an example, with historical data on its sailing load referenced from reference [24]. It uses Equations (2) and (3) to calculate the power of its HESS, then decomposes the power of the HESS. The optimized VMD parameters obtained from the first-time MVO-VMD and secondary MVO-VMD are shown in Table 2. The 13 components obtained from the preliminary decomposition are shown in Figure 3, and their spectral characteristics are illustrated in Figure 4. Based on the spectral characteristics of the initial decomposition results and the degree of mode mixing, these 13 components are divided into high-frequency and low-frequency groups. The low-frequency group obtained from the first decomposition undergoes a secondary decomposition, resulting in 12 components as shown in Figure 5. The spectral characteristics of these components are illustrated in Figure 6. Similarly, the high-frequency group obtained from the first decomposition undergoes a secondary decomposition to generate another set of 12 components as shown in Figure 7 with their spectral characteristics illustrated in Figure 8.

Table 2.

MVO-VMD related parameters.

Figure 3.

Initial MVO-VMD.

Figure 4.

Initial MVO-VMD spectrum.

Figure 5.

Low−frequency secondary MVO-VMD.

Figure 6.

Low−frequency secondary MVO-VMD spectrum.

Figure 7.

High−frequency secondary MVO-VMD.

Figure 8.

High−frequency secondary MVO-VMD spectrum.

Figure 3 shows the results of the initial MVO-VMD for power distribution in the HESS during a typical voyage of the “Alsterwasser” cruise ship. Figure 4 shows the spectrum obtained from the initial MVO-VMD. The boundary points between high and low frequencies in the initial decomposition results can be determined based on the degree of mode mixing, as shown in Table 3. In Figure 3, the green curve represents the low-frequency component, while the yellow curve represents the high-frequency component.

Table 3.

Initial MVO-VMD.

The results of the secondary decomposition exhibit significant mode overlap, as shown in Figure 6 and Figure 8. High-frequency and low-frequency components cluster together, making it complicated to accurately identify frequency boundary points based on modal mixing degrees. This can lead to inaccurate allocation results; for example, due to the indistinguishability of component frequencies caused by modal overlap, there is a risk of mistakenly allocating components that should be assigned to supercapacitors to lithium batteries instead. Such misallocation not only causes fluctuations in output power but also shortens the lifespan of lithium batteries due to excessive charging and discharging cycles, thereby increasing costs. Therefore, the power distribution after secondary decomposition cannot be determined by the degree of modal aliasing but is allocated to lithium batteries or supercapacitors based on the differences in the center frequencies of the components obtained from secondary decomposition [14]. Based on the central frequencies and degree of aliasing obtained from the components of secondary decomposition in Figure 6 and Figure 8, they are, respectively, assigned to lithium batteries and supercapacitors as illustrated in Figure 5 and Figure 7. The allocation results are presented in Table 4. The green curve in Figure 5 represents the lithium battery component, while the purple curve represents the supercapacitor component. In Figure 7, the blue curve indicates the lithium battery component, and the yellow curve indicates the supercapacitor component.

Table 4.

Secondary MVO-VMD.

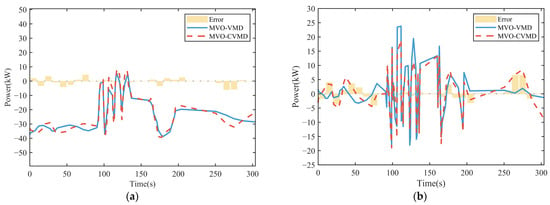

Based on the decomposition results mentioned above, we can derive the power variation curves of lithium batteries and supercapacitors under MVO-VMD and MVO-CVMD, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

(a) Lithium battery power curve; (b) supercapacitor power curve.

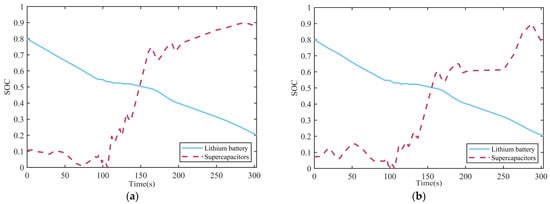

Based on the power curves mentioned above and the parameter settings for lithium batteries and supercapacitors in reference [23], we can obtain the SOC curves of lithium batteries and supercapacitors during a typical voyage of the “Alsterwasser” cruise ship, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

(a) MVO-VMD; (b) MVO-CVMD.

From Figure 9, the lithium battery exhibits smoother power output compared to the supercapacitor’s dynamic profile, consistent with their respective energy delivery characteristics—batteries provide stable discharge while supercapacitors enable instantaneous power response. Additionally, the power curve after decomposition using MVO-CVMD is smoother than the one after decomposition using MVO-VMD.

From Figure 10, the SOC variation in the battery is relatively smoother compared to that of the supercapacitor. At the same time, when comparing Figure 10b, it becomes clear that under MVO-CVMD mode decomposition, both charging and discharging processes for the battery and supercapacitor are more thorough than those under MVO-VMD mode decomposition; additionally, the discharge process of the supercapacitor is even more complete. It also reaffirms the rationale behind using MVO-CVMD modal decomposition for power allocation in HESS.

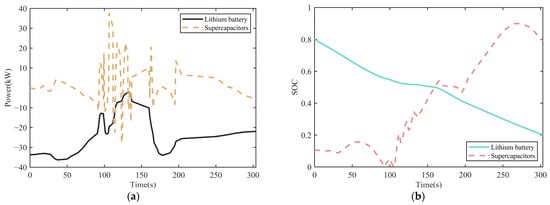

Through VMD power decomposition and capacity configuration of the aforementioned HESS, the power and SOC characteristics for both lithium batteries and supercapacitors were obtained for the “Alsterwasser” vessel, as illustrated in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

(a) VMD decomposed power curve; (b) VMD SOC curve.

Due to the high dependence of traditional VMD on the selection of empirical parameters, it is not well-suited for power decomposition across various frequency ranges. As can be seen in Figure 11a, its power decomposition is inadequate, resulting in an unreasonable power distribution and failure to fully leverage the characteristic of supercapacitors that allows them to provide short bursts of high power. Compared to Figure 10, it is clear that the curve of the supercapacitor in Figure 11b is smoother, which can easily lead to excessively fast charging and discharging of lithium batteries, thereby reducing their lifespan and increasing costs.

Analysis of Capacity Configuration Results

This study performed case validation of the proposed HESS capacity configuration methodology, deriving the respective power distribution profiles for lithium batteries and supercapacitors during characteristic operational phases of the “Alsterwasser” vessel. The capacity configuration results obtained based on the parameters of lithium batteries and supercapacitors provided from reference [23] are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Capacity configuration results.

From Table 5, it can be seen that the HESS of fuel cell vessel configuration cost is reduced by 10.82% compared to VMD and by 4.05% compared to MVO-VMD. The traditional VMD heavily relies on the selection of empirical parameters, which can lead to insufficient accuracy in its decomposed structure and result in unreasonable capacity allocation. By introducing MVO to optimize the adaptive selection of parameters for VMD, this effectively addresses the issues in traditional VMD and enables reasonable capacity allocation, thereby reducing costs. Although the parameter issue has been resolved, a single MVO-VMD may result in inadequate accuracy of the obtained decomposed results and lead to modal aliasing. Due to the limitations of single-instance MVO-VMD, power is decomposed and cross-distributed twice. This approach addresses the problem of mode mixing, further enhances the accuracy of power distribution, and also reduces capacity configuration costs. The MVO-CVMD outperforms traditional VMD and single-instance MVO-VMD in both power decomposition and capacity allocation. Therefore, the MVO-VMD is better suited to handle high-frequency fluctuation signals and can achieve more efficient capacity allocation, ultimately leading to a reduction in the costs associated with capacity configuration. This will play an important role in promoting the development of fuel cell ships in the future, providing better strategies for power distribution and improved solutions for capacity configuration. It also has applicability in wind energy, photovoltaic storage, and other areas.

6. Discussion

The topic of this study uses the typical navigation behavior of the “Alsterwasser” cruise ship as a sample and focuses on a HESS composed of batteries and supercapacitors. This study develops an optimized power distribution approach for HESS using enhanced Variational Mode Decomposition (MVO-CVMD). The capacity configuration targets minimizing the HESS’s lifecycle expenditures through component-level cost reduction. Based on the above research, three key findings emerge from this investigation:

- The MVO algorithm optimizes VMD parameters by minimizing sample entropy via iterative computation. The results of the first decomposition are [13, 1316], while the second decomposition yields [12, 1010] and [12, 2043]. Results demonstrate the MVO algorithm’s superior convergence speed and optimization precision.

- The MVO-CVMD algorithm executes a two-stage decomposition process for the HESS’s power signals. Considering the distinct operational properties of individual energy storage elements, an optimized cross-power allocation strategy was implemented for the HESS. The state of charge (SOC) of the supercapacitor after MVO-CVMD is 80%, compared to 89% after MVO-VMD, indicating a discharge depth improvement of 10.11%. The supercapacitor discharges more thoroughly. The issues of incomplete decomposition and mode mixing have been effectively resolved.

- The capacity configuration of the HESS is aimed at minimizing the total lifecycle cost of energy storage devices, resulting in different configuration costs under various allocation strategies. Through a comparison of costs, it has been verified that the MVO-CVMD used in this paper reduces costs by 10.82% compared to VMD and by 4.05% compared to MVO-VMD.

Based on the above findings, this article presents a power allocation and capacity configuration based on the MVO-CVMD algorithm, which can effectively improve the accuracy of power distribution while also significantly reducing costs. However, this method performs poorly in terms of real-time responsiveness and cannot respond promptly to changes in ship load. Additionally, when the signal contains strong noise, it can result in extracted components that include excessive noise information, which affects the accuracy of subsequent analysis.

In future research, there can be a deep integration with deep learning, which is the most promising direction. It is possible to train a deep neural network that directly learns the end-to-end mapping from raw signals to the optimal VMD parameter . Once the model training is complete, the process of parameter determination becomes almost instantaneous, thoroughly resolving computational bottlenecks and making real-time adaptive signal processing possible. The model can learn complex features from vast amounts of data that are difficult for humans to design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H. and X.L.; methodology, J.H. and X.L.; software, X.L.; validation, X.L.; formal analysis, J.H. and X.L.; investigation, X.L.; resources, X.L.; data curation, X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L.; writing—review and editing, J.H.; visualization, X.L.; supervision, J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their comments on this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Feng, Y.; Qu, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Jing, H. Utilizing waste heat from natural gas engine and LNG cold energy to meet heat-electric-cold demands of carbon capture and storage for ship decarbonization: Design, optimization and 4E analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 446, 141359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, B.R.; Alahakoon, S.; Rensburg, V.J.P. Impact of Coordinated Electric Ferry Charging on Distribution Network Using Metaheuristic Optimization. Energies 2025, 18, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Dai, Y.; Chen, Z.; Feng, Y.; Wu, Y. Model experimental research of the air injection drag reduction system without air maintenance devices for a 2600 DWT bulk carrier. Ocean Eng. 2025, 323, 120661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Pan, L.; Zhang, J.; Jin, Z.; Jiang, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Tang, R.; Lai, J.; Yang, X.; et al. A novel capacity allocation method for hybrid energy storage system for electric ship considering life cycle cost. J. Energy Storage 2025, 116, 116070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Guo, H.; Peng, W.; Yan, G.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, N.; et al. Progress and Perspectives of Garnet-Based Solid-State Lithium Metal Batteries: Toward Low Resistance, High Energy Density and Improved Cycling Capability. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2024, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dědek, I.; Šedajová, V.; Kupka, V.; Zedníček, T.; Primavesi, L.; Aurbach, D.; Noked, M.; Otyepka, M. High-performance carbon-based supercapacitors. 2D Mater. 2024, 12, 043004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleva, M.; Shi, Y.; McKenna, K.; Craig, M.; Nagarajan, A. Optimal Strategies for Hybrid Battery-Storage Systems Design. Energy Technol. 2023, 11, 1995575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Wen, X.; He, M.; Tang, Q.; Tan, J. Operation Control Design of Grid-Connected Photovoltaic and Fuel Cell/Supercapacitor Hybrid Energy Storage System. Energies 2025, 18, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulmawjood, K.; Morsi, G.W. Analyzing Partial Shading in PV Systems Using Wavelet Packet Transform and Empirical Mode Decomposition Techniques. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 56085–56099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Jia, Z.; Huang, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J. Optimization of Cooling Strategy for Lithium Battery Pack Based on Orthogonal Test and Particle Swarm Algorithm. J. Energy Eng. 2023, 149, 04023026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Jin, H.; Pan, Z.; Yun, L.; Wen, F.; Yang, H.; Tao, Y. Optimal Strategy for Enhancing Probabilistic Small-Signal Stability in a Power System with Wind-PV-Thermal Bundled Transmission. J. Energy Eng. 2023, 149, 04023014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Niu, D.; Yun, J.; Siqin, Z. Distributionally Robust Optimization Model of the Integrated Energy System with Integrated Demand Response. J. Energy Eng. 2025, 151, 04025022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cai, Z.; Zheng, J.; Shen, S.; Dong, W.; Liu, D. Prediction of Lithium-Ion Battery Remaining Useful Life via Empirical Mode Decomposition- Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average and Regularized Particle Filter Algorithm. Energy Technol. 2023, 11, 2300232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, D.; Xiao, Z.; Qiu, Q.; Tao, X.; Qian, Q.; Jiang, M.; Yu, W. Power Allocation and Capacity Optimization Configuration of Hybrid Energy Storage Systems in Microgrids Using RW-GWO-VMD. Energies 2025, 18, 4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; He, D.; Ma, R.; Zou, X.; Chen, Y.; Shan, S. Fault diagnosis of train rotating parts based on multi-objective VMD optimization and ensemble learning. Digit. Signal Process. 2022, 121, 103312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirubadevi, S.; Sathesh Kumar, T.; Sivarajan, S.; Venkata Krishna Reddy, C. Optimizing Cost and Emission Reduction in Photovoltaic–Battery-Energy-Storage-System-Integrated Electric Vehicle Charging Stations: An Efficient Hybrid Approach. Energy Technol. 2024, 12, 2301131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Wang, H.; Zou, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, B.A. Two-Layer Energy Management Strategy of Fuel Cell Hybrid System in Electric Ships. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 61, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, B. HESS energy configuration strategy based on load regulation for wind power. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2024, 19, 1516–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandic, D.P.; Ur Rehman, N.U.; Wu, Z.; Huang, N.E. Empirical Mode Decomposition-Based Time-Frequency Analysis of Multivariate Signals: The Power of Adaptive Data Analysis. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2013, 30, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomiretskiy, K.; Zosso, D. Variational Mode Decomposition. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2014, 62, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Ye, M.; Wu, Q. Capacity allocation method for a hybrid energy storage system participating in secondary frequency regulation based on variational mode decomposition. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 167, 110631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, M.S.; Hatamlou, A. Multi-Verse Optimizer: A nature-inspired algorithm for global optimization. Neural Comput. Appl. 2016, 27, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, C.; Du, X.; Chen, T.; Hu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Lu, J. Capacity configuration of hybrid energy storage system for ocean renewables. J. Energy Storage 2025, 116, 116090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Charpentier, J.; Tang, T. An Energy Management System of a Fuel Cell/Battery Hybrid Boat. Energies 2014, 7, 2799–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).