Abstract

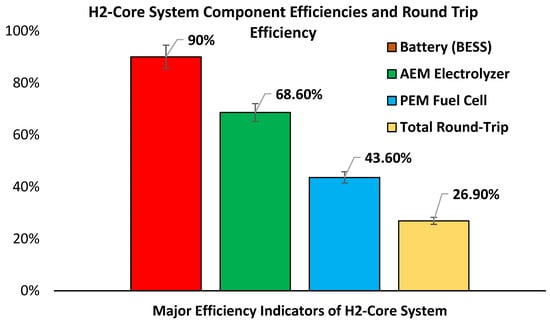

Rising energy demand, fossil fuel depletion, and global warming are accelerating research into sustainable energy solutions, with growing interest in hydrogen as a promising alternative. This research presents a detailed experimental investigation and novel digital twin (DT) models for an integrated hydrogen-based energy system consisting of an Anion Exchange Membrane Electrolyzer (AEMEL), Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell (PEMFC), hydrogen storage, and Battery Energy Storage System (BESS). Conducted at a real-world facility in Risavika, Norway, the study employed commercial units: the Enapter EL 4.1 AEM electrolyzer and Intelligent Energy IE-Lift 1T/1U PEMFC. Experimental tests under dynamic load conditions demonstrated stable operation, achieving hydrogen production rates of up to 512 NL/h and a specific power consumption of 4.2 kWh/Nm3, surpassing the manufacturer’s specifications. The PEMFC exhibited a unique cyclic operational mechanism addressing cathode water flooding, a critical issue in fuel cell systems, achieving steady-state efficiencies around 43.6% under prolonged (190 min) rated-power operation. Subsequently, advanced DT models were developed for both devices: a physics-informed interpolation model for the AEMEL, selected due to its linear and steady operational behavior, and an ANN-based model for the PEMFC to capture its inherently nonlinear, dynamically fluctuating characteristics. Both models were validated, showing excellent predictive accuracy (<3.8% deviation). The DTs integrated manufacturer constraints, accurately modeling transient behaviors, safety logic, and operational efficiency. The round-trip efficiency of the integrated system was calculated (~27%), highlighting the inherent efficiency trade-offs for autonomous hydrogen-based energy storage. This research significantly advances our understanding of integrated H2 systems, providing robust DT frameworks for predictive diagnostics, operational optimization, and performance analysis, supporting the broader deployment and management of hydrogen technologies.

1. Introduction

Climate change, driven primarily by manmade greenhouse gas emissions (GHGE), remains one of the most critical global challenges of the 21st century [1]. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the Earth has already warmed by approximately 1.1 °C above pre-industrial levels [2]; without immediate and sustained mitigation efforts, the threshold of 1.5 °C could be breached as early as 2030 [3]. To address climate change and the pathway to net zero, more than 140 countries have committed to achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 [4,5]. Achieving these climate targets necessitates radical transformation of the energy sector [6], which is responsible for over 73% of global GHGE [7]. Renewable energy (RE), such as wind [8] and solar PV [7], is widespread. New types such as geothermal [9] and wave [10] energy are emerging. Renewables’ deployment is accelerating, accounting for nearly 30% of global electricity generation in 2023, led by solar PV and wind [11]. However, to support the intermittency of renewables and achieve full decarbonization across sectors, deeper integration of flexible, clean energy technologies is essential [12]. Key economies including the EU, the US, China, and India have outlined aggressive decarbonization pathways [13]. Specifically, these road maps for sustainable future energy pathways are centered on H2-based circular economic subplans [14]. Among other potential solutions, hydrogen stands out as a potential energy vector to accelerate the green energy transition [15]. The global transition toward clean energy systems has intensified the demand for efficient, reliable, and responsive technologies capable of enabling renewable integration, decarbonization, and grid flexibility [16]. Among these technologies, electrolyzers, fuel cells (FCs), and Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESSs) have emerged as pivotal components in next-generation energy infrastructures [17]. Their ability to work synergistically in converting and storing renewable electricity, producing green hydrogen (H2), and delivering dispatchable power makes them essential to the architecture of sustainable energy systems.

Among various H2 production methods, water electrolysis powered by renewable sources producing “green hydrogen” is considered one of the most promising pathways for sustainable energy [18]. Traditional electrolyzer technologies such as Alkaline Water Electrolysis (AWE) [19] and Proton Exchange Membrane Water Electrolysis (PEMWE) [20] have been widely developed but face notable limitations. Currently, alkaline technology has a Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of 9 and it is commercially used in industry; PEM, in contrast, is mainly used for medium and small applications (TRL = 6–8) [21]. AWE suffers from low efficiency and gas crossover, while PEMWE, despite its high performance, relies heavily on costly precious metals and corrosion-resistant materials due to its acidic operating environment [22]. In contrast, the Anion Exchange Membrane Electrolyzer (AEMEL) represents a next-generation solution merging the structural benefits of PEM with the cost-effectiveness of AWE [23]. Operating under alkaline conditions, AEMELs allow the use of abundant and inexpensive catalysts like Ni, eliminating the need for expensive materials such as Pt or Ir [24]. The membrane in AEMELs selectively conducts hydroxide ions (OH−) while acting as a physical barrier to prevent gas mixing, enabling safe and efficient H2 and O2 generation [25]. It reduces material costs and maintains mechanical integrity under moderate pressure, making AEMELs suitable for decentralized or modular green H2 applications [24,25]. Although AEMELs are in the early stages of commercialization (TRL = 5–6 used in small commercial applications), they have demonstrated significant potential in reducing the cost of H2 production and enabling broader deployment [26]. Commercial systems like AEMEL by ENAPTER illustrate the emerging practical applications of this technology [27]. As market interest grows, AEMELs are poised to become a key enabler in carbon-neutral hydrogen production [28].

The cornerstone of utilizing H2 as an energy carrier lies in the use of fuel cells (FCs), widely acknowledged as the most feasible solution for energy conversion [29]. FCs directly transform the chemical energy stored in hydrogen and oxygen into electrical energy, emitting only heat and water as by-products [30]. Among various FC types, the Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell (PEMFC) has garnered significant attention due to its favorable characteristics, including fast response times, zero emissions, high conversion efficiency, and quick start-up capabilities [31]. PEMFC systems are typically divided into two categories based on how oxygen is supplied to the cathode [32]. Closed-cathode PEMFCs, which rely on compressors to supply oxygen, are commonly implemented in medium-scale (10–100 kW) to large-scale (>100 kW) applications such as electric vehicles, industrial transport systems, and heavy-duty machinery [33]. Open-cathode PEMFCs utilize ambient air drawn by fans, exposing the cathode directly to environment [34]. These are predominantly used in compact applications (below 10 kW), including portable power units, drones, range extenders, and light electric vehicles [35]. Despite their range of applications, PEMFCs generally operate on comparable fundamental principles.

Despite the advantages of these technologies individually, their combined operation introduces new challenges in terms of integration, dynamic control, and predictive maintenance. These complexities necessitate advanced modeling and monitoring tools that can replicate real-world behavior with high fidelity. Digital twin (DT) technology has emerged as a transformative approach, offering real-time simulation, fault detection, and performance optimization by creating a virtual replica of physical systems [36]. The concept of a DT for electrochemical energy systems is emerging as a powerful tool to enable real-time monitoring, prediction, and control of system behavior under varying operating conditions [37]. AEMELs and PEMFCs are highly suitable candidates for DT integration due to their dynamic response characteristics and operational complexity [38]. DT combines experimental data with physics-based or data-driven models to create a virtual real-time replica of the physical system, enabling predictive diagnostics, performance optimization, and fault detection [39]. For AEMELs, a DT can track H2 production rates, efficiency, and stack health under different loads and water management conditions. For PEMFCs, a DT can model voltage, current, power output, and thermal behavior in real time, accounting for effects such as flooding, degradation, or control logic [40]. This dual DT framework supports the development of smart H2-based energy systems by enabling precise interaction between generation (AEMEL) and consumption (PEMFC), which is critical for future integrated and autonomous energy networks.

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. AEM Electrolyzer Literature Survey

The AEMEL is an emerging electrolyzer type and the open-access literature is limited. Md Motakabbir Rahman et al. (2024) [41] explored powering a three-cell, 50 cm2 AEMEL using an open-source DC-DC converter integrated with solar PV and achieved >90% converter efficiency and an annual H2 production of 5 kg (57,810 L). Bowen Yang et al. (2023) [42] compared the H2 production costs of ALK, PEM, and AEM. In the short term, the AEM cost was 23.85% higher than that of ALK; in the long term, the AEM cost was projected to be 24% lower than that of ALK. F. Moradi Nafchi et al. (2024) [43] analyzed a solar-powered AEMEL system with hydrogen blending in natural gas. H2 injection at a 10% vol reduced the LHV and Wobbe Index by 6% and 1.55%. The exergy cost of H2-blended gas increased by 5.9%; eliminating the compressor reduced the hydrogen supply cost by 29.3%. Selvam Praveen Kumar et al. (2023) [44] tested seawater electrolysis using an AEMEL with a HEMO@GO catalyst and reached 10 mA/cm2 at overpotentials of −482 mV (HER) and 597 mV (OER). The fuel-cell output was 0.19 A at 3 V and 32 mL/h hydrogen at 2 V. Rushabh Kamalakar Kale et al. (2025) [45] simulated three configurations of AEMWE-based systems. AEMWE plus AEMFC gave 45.5% net efficiency. Adding STU reduced it to 35.9%. Using solar PV gave an overall efficiency of 7.33–8.21%. Yoo Sei Park et al. (2023) [46] optimized the ionomer content in the anode layer and achieved 1.44 A/cm2 at 1.8 V, a 25% increase over a non-optimized cell. E. López-Fernández et al. (2022) [47] used ionomer-free Ni–Fe/Ni electrodes with different GDLs and achieved 670 mA/cm2 at 2.2 V (40 °C, 1.0 M KOH), maintaining 400 mA/cm2 for 7 days in chronopotentiometry. Laura J. Titheridge et al. (2024) [48]’s techno-economic model estimates the baseline Levelized Cost of Hydrogen (LCOH) at USD 5.79/kg for AEMWE, but projects that technical improvements and low-cost electricity could lower it to USD 1.29/kg, close to DOE targets. The projected cost is USD 2/kg and the optimal current density is 1.38 A/cm2. Shing-Cheng Chang et al. (2024) [49] simulated the effects of temperature, pressure, and electrolyte. Optimal efficiency reached 56.4% at 328 K and 30 bar. Energy efficiency improved when the operating temperature increased from 313 K to 353 K. Ceren Celebi et al. (2025) [50] modeled PBI-based membranes and achieved 83.9% efficiency using a 25 µm membrane at 80 °C, 1 M KOH, and a 2 A/cm2 current density. A 50 µm membrane gave 79.8% efficiency. Refer to Table 1 for the extended literature.

Table 1.

Extended literature survey summary of AEMEL and PEMFC.

1.1.2. PEM Fuel Cell Literature Survey

A. Alaswad et al. (2016) [74] reviewed PEMFCs for transportation applications, identified major challenges including high cost, limited durability (due to membrane and flow plate degradation), and hydrogen infrastructure, and emphasized the need for platinum-free catalysts and durable materials to reduce cost and improve commercial viability. Simon T. Thompson et al. (2018) [75] performed a cost analysis for an 80 kWnet automotive PEMFC stack. For large-scale production (100,000–500,000 units/year), the projected costs were USD 50/kWnet to USD 45/kWnet. The research identified USD 30/kWnet as the DOE target for ICEV cost competitiveness and outlined design improvements for cost reduction. Yakoub Zine et al. (2024) [76] evaluated five MPPT algorithms on a 200 W PEMFC system. All achieved ~48% efficiency, but ANFIS performed the best in stability, convergence speed, and current fluctuation. This work showed that data-driven control methods significantly enhance PEMFC operating reliability and lifetime. Mingkai Wang et al. (2024) [77] investigated CO poisoning and fault behaviors in PEMFCs running on impure hydrogen, showed self-recovery under anode water flooding and identified voltage behavior patterns for detecting fault type and location, and achieved a 100 ppm CO tolerance without added hardware. Badis Lekouaghet et al. (2025) [78] proposed a human-inspired AISA algorithm for parameter estimation in three PEMFC models, achieving minimum SSEs: 7.64 × 10−3, 1.29× 10−2, and 2.29. They validated results across four additional stacks and outperformed GBO, POA, and HBA in convergence, stability, and runtime (as low as 0.5766 s). Mehdi Seddiq et al. (2025) [79] simulated thermal shock (down to 10 °C) in PEMFCs. They observed a 15% drop in current density (from 9263 A/m2 to 7709 A/m2), with water saturation and oxygen drop affecting performance. The research aimed to improve thermal management strategies for aerospace use. Ponce-Hernández et al. (2025) [80] developed a humidity diagnosis model using Nyquist-based impedance fitting. They achieved a 0.04% model error vs. 2.41% in commercial software, using two iterations, and showed precise monitoring of RH effects at 75%, 80%, and 100% for improved humidity control in PEMFCs. Miroslav Hala et al. (2024) [81] modeled metallic bipolar plates with different channel shapes (trapezoidal vs. rectangular), and identified optimized geometry for stamped plates: 0.2 mm ground width, 0.4 mm rib width. This resulted in uniform flow and performance comparable to traditional milled plates. Ayoub Igourzal et al. (2024) [82] designed a fault-tolerant power management system (PMS) for multi-stack PEMFC systems at lab scale. Optimization reduced the lifetime cost by 34% and extended stack life by 30% by incorporating durability and ageing in system sizing and operation. See Table 1 for the extended literature.

1.1.3. Literature Survey for AEMEL and PEMFC Digital Twin Models

H. Naanani et al. (2025) [83] reviewed DT applications across the hydrogen value chain, highlighting benefits such as real-time monitoring, predictive maintenance, and up to 12% efficiency gains in electrolyzers. The challenges noted include data quality, computational demand, and cybersecurity. Shaojie Liu et al. (2025) [84] introduced a behavior-matching DT for PEM electrolyzers, reducing real-time error by 65% and improving accuracy under fluctuating renewable inputs. Sudarshan Chavan et al. (2017) [85] used a MATLAB (R2024b (version 24.2))/Simulink model to show the impact of double-layer capacitance on PEMFC performance, especially at low loads. Zheng Zhou et al. (2024) [86] developed a PEMWE DT focusing on thermal management, enabling sensor-less temperature monitoring to enhance large-scale system stability. Ming Zhang et al. (2023) [87] proposed a DT-LSTM model for real-time remaining useful life (RUL) prediction of PEMFCs using minimal online data. Francisco Javier Folgado et al. (2023) [88] developed and validated a digital replica of a six-cell PEM electrolyzer using an equivalent circuit model based on cell-specific internal resistance obtained via MATLAB curve fitting. A PLC–LabVIEW DAQ system supports accurate data collection, and the DR closely matches the experimental voltage, power, efficiency, and hydrogen production. The approach uses scalable commercial components, is computationally light, and can be applied to other electrolyzer designs. Future work includes model comparison, predictive control, and dynamic PEMEL modeling. Safa Meraghni et al. (2021) [89] propose a data-driven DT prognostics method for predicting PEMFCs’ remaining useful life (RUL) by continuously updating a degradation model with real-time measurements. Using a stacked denoising autoencoder, the DT maps stack voltage to RUL and adapt to varying conditions, achieving over 0.9 accuracy even with limited data, supporting future predictive maintenance strategies.

1.2. Novelty and Contribution of the Paper

This paper is novel and state-of-the art under several key categories, thus filling numerous crucial research gaps and voids. The majority of the literature focuses solely on either the electrolyzer, FC, or BESS. In the literature, the majority of studies have focused on small lab/bench-scale experimental-level electrolyzers, FCs, and BESSs individually, while studies on system-level commercial electrolyzers, FCs, and BESSs as a unit base are scarce. Throughout the literature survey, no studies have conducted experimental analysis of the real-world, actual operation of a H2-based energy system comprising an AEMEL, PEMFC, and BESS. The current paper addresses this research gap by reporting a state-of-the-art H2-core system experimental analysis comprising an AEMEL, PEM fuel cell, H2 storage, and BESS combined energy system and DT models. In addition to stationary microgrid relevance, this integrated AEMEL–PEMFC–BESS configuration also reflects architectures used in vehicle-engineering applications, such as onboard hydrogen auxiliary power units, range-extender systems, and hybrid propulsion support. Therefore, the findings and DT models developed here hold practical significance not only for stationary energy systems but also for emerging hydrogen-mobility technologies.

1.2.1. AEMEL

Specifically, AEMELs are a new, emerging hot research topic with very limited research activities being performed within the domain of electrolyzers. In the major databases (Web of Science and SCOPUS), no studies were found addressing commercial-level AEMEL testing under real operating conditions without test/lab-scale simplifications and zero-assumptions set, such as the AEMEL unit which the authors analyzed and replicated as a digital twin model [90]. However, apart from the manufacturer’s claims, real-world implementation and research-oriented dynamic testing of a particular AEM-type electrolyzer has not previously been performed strictly for the category of AEMELs. Since AEMELs are currently at TRL 4–5, this analysis stand outs as state of the art for experimental investigation of an AEMEL in real-world applications.

1.2.2. PEMFC

Most of the studies focused on parameter identification and modeling, degradation analysis and prognostics, thermal and environmental management, recycling and end-of-life strategies, electrochemical diagnostics, lab-scale experiments and system-level integration and applications, individual cell architectures, and dual-mode operation. Based on an extended literature survey, the authors found no recent studies (only two 18–15-year-old studies found on older-generation commercial PEM-FCs) conducted on commercial-level PEMFC units. Intuitively, tests and experiments conducted on a real-world test site for PEMFC operations have been particularly focused on understanding water-flooding phenomena, its preventive mechanism, and identification techniques through data interrogation. This paper will be the frontrunner by identifying and analyzing a modern commercial PEMFC unit and developing a DT that replicates its real-world behavior, operational constraints, and dynamic responses under varying environmental and load conditions.

1.2.3. Digital Twin (DT) Modeling

To date, most DT studies in the domain of H2 have focused on general PEM electrolyzers, alkaline systems, or theoretical frameworks, with limited attention to commercially relevant, experimentally validated DTs tailored to specific technologies (based on 1.1.3). Commercial PEMFC-DT modeling-related research studies are rare and very exceptional in the literature and we have not found any paper addressing AEMELs, PEM fuel cells, and experimental work combinedly adjoining them with DTs. According to the authors’ knowledge, this work is the first to develop and present two distinct, real-time DT models specifically for a commercial integrated AEMEL and a PEMFC, using real operational data from the test unit. It is worth noting that only a small number of publications have reported DTs for hydrogen-related equipment based on experimental data, with the majority of existing studies focusing on simulation-based or partially developed DT frameworks. As a result, experimentally supported DT research remains limited. The integration of real experimental equipment in this work therefore constitutes a significant contribution to the current state of the art.

1.2.4. Potential Contribution of AEMEL and PEMFC Digital Twins

Distinct DTs allow modular optimization and correctly decouple the generation side (AEMEL) from the consumption side (PEMFC), allowing independent modeling and performance enhancement utilizing AI combined with rule-based logic. DT combines ML prediction with real-world logic (constraints or shutdown simulation), coupling hybrid intelligence. Realistic boundaries and alerts set for both DTs replicate not just outputs but embedded safety logic, making them far more realistic than academic-only simulations. Both models are grounded in experimental data and incorporate manufacturer-specific operational constraints, enabling predictive performance evaluation, safety analysis, and diagnostic capability. Notably, the PEMFC-DT uniquely infers internal purging and thermal control behavior, offering rare insight into embedded system logic. Beyond their technical function, these DTs provide a cost-effective, low-risk alternative to physical testing, opening new doorways as valuable tools for education, research, and training. They allow users to explore system behavior, fault scenarios, and control strategies without the need for continuous operation of expensive, high-cost-of-maintenance hardware equipment. In addition, both DTs serve as virtual platforms for techno-economic analysis (TEA) [91], enabling simulation of energy consumption, electro-hydrogen cost [92], efficiency trends, and system responses under varying operational conditions, supporting applications such as scenario planning, feasibility studies, and policy evaluation for expanding H2 deployment. DTs’ modular structure also allows for future integration into unified energy system simulations connecting generation and utilization stages within smart grid, microgrid, or hybrid renewable energy frameworks.

This paper presents a comprehensive experimental analysis of an AEMEL and PEMCL coupled with H2 storage and a BESS suitable for microgrid application. The rigorous experimental data were then utilized for a digital twin modeling framework of the AEMEL and PEM fuel cell for digital platform-based cost-effective operational analysis for educational, training, and simulation purposes. The study is grounded in empirical data obtained from real-world operation (test site Risavika, Norway), which serve as the foundation for training and validating the DT models. The DT approach adopted in this work not only captures the nonlinear dynamics and transient behaviors but also enables predictive insights that enhance operational reliability and system efficiency. Through this integrated experimental and modeling approach, the paper aims to contribute to broadening the uncharted understanding of real-world operations of a commercial AEMEL and PEMFC as the core of an integrated H2-based energy system, as well as expanding our understanding of operational round-trip of such systems, and thereby simultaneously advancing development of intelligent, data-driven modeling and analysis strategies for these systems through innovative DT models. The findings are intended to support the broader deployment of H2-based technologies and accelerate the adoption of smart energy systems capable of meeting future decarbonization goals, in alignment with key UN Sustainable Development Goals such as SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and SDG 13 (Climate Action).

1.3. Progression of the Paper

Section 1 illustrates a brief introduction, extended literature survey on AEMEL and PEMFC physical systems, then AEMEL- and PEMFC-based DT models, the novelty of the study on AEMEL, PEMFC, and BESS, and the contributions of the paper. Section 2 provides the experimental method, setup, description of AEMEL, PEMFC, and each unit of the H2-core system, and mathematical modeling of AEMEL- and PEMFC-DTs architecture. Section 3 presents the AEMEL and PEMFC experimental results and analysis, PEMFC water-flooding phenomena and prevention, AEMEL and PEMFC experimental results’ comparison with theoretical modeling and their variations, PEMFC efficiency comparison with the literature, system level performance, evaluation of the AEMEL and PEMFC-DT models, AEMEL efficiency variation with duty point, and round trip-evaluation of the total H2 energy system. Finally, Section 4 presents the conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

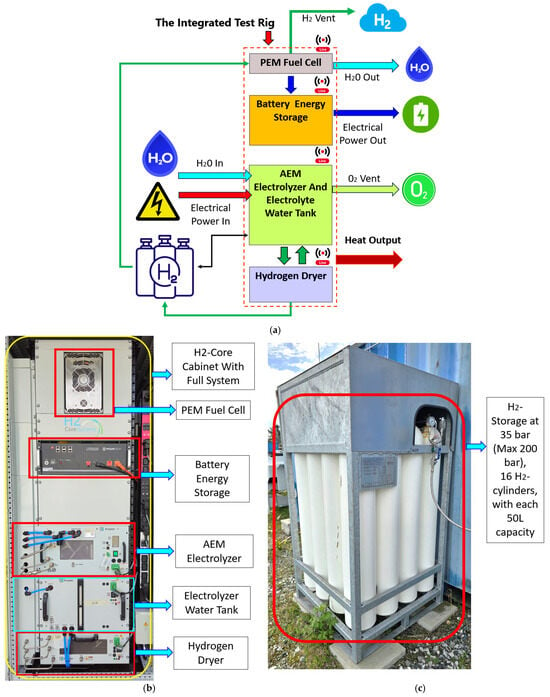

For development of a DT of an integrated system state-of-the art experimental setup was established at the University of Stavanger (UiS) in Norway, at the premises of the NORCE (Risavika) testing facility [93]. The process (Figure 1a) begins with AEMEL, which produces H2 at elevated pressure. This H2 is dried and stored in bottles at 35 bar for later use. The integrated PEMFC converts the stored H2 into electricity, which is stored in a BESS. Excess H2 and O2 are vented to the atmosphere. The entire system includes integrated communication modules that provide 24/7 real-time monitoring via mobile apps and server-based platforms.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic diagram of the components, connections, and experimental setup of H2-core; (b) H2-core system cabinet, AEMEL (water tank and dryer), PEMFC, and BESS; (c) H2 storage (16 cylinders) at the University of Stavanger, Norway.

2.1. Experimental Procedure for Research

The integrated system by H2 Core Systems® [94] consists of six main components (see Figure 1a,b): Enapter EL 4.1 electrolyzer [90], water tank, H2 dryer, H2 storage (50 L × 16 bottles) (Figure 1c), 1.0 kW fixed-output Intelligent Energy fuel cell (IE lift 1T/1U) [95], and 4.8 kWh Pylontech LiFePO4 battery storage unit (48 V, US5000) [96]. This system configuration allows only one component (either electrolyzer or FC) to operate at a time. Due to safety considerations including the risk of oxyhydrogen formation or gas backflow during transient pressure changes, the AEMEL and PEMFC were not operated simultaneously; this is a known design and control challenge in compact, small-scale integrated hydrogen systems. The FC, when operated, purges excess gas out from the stack cyclically every 7–8 min. The presence of a H2- and O2-rich closed environment causes a high risk of oxyhydrogen formation [97]. To mitigate this risk, when the electrolyzer senses small amounts of H2 in the ambient environment, it activates automatic shutdown. This will be resolved in the near future to allow simultaneous operation of the electrolyzer and the fuel cell. To avoid emergency shutdown, the electrolyzer is operated first, and H2 is stored, then the FC is activated, and the battery pack charged. During the experiments, the FC was tested independently at 100% load (1.0 kW) and the power was used to charge the battery directly. AEMEL was evaluated under two phases: initial ramp-up from 0% to 100% load; stepwise load reduction from 100% to 60% load, in 5% decrements (staged partial load testing). Each load stage was maintained for 10 min to ensure steady-state behavior and to allow reproducible measurement of the corresponding electrical and thermal responses. The AEMEL EL 4.1 is controlled via the Enapter EMS using Modbus TCP over Ethernet, with a Wi-Fi live data feed. The 1 kW Intelligent Energy IE-Lift 1T/1U PEM FC provides a CAN bus interface for the status and diagnostic data exchange, while the Pylontech US5000 4.8 kWh battery module exposes both the CAN and RS485 ports for BMS communication. Together, these fieldbus interfaces enable structured data exchange between the physical components, the EMS, and later with the Python-based DT environment (Python 3.12). The purpose of these experiments was to monitor performance parameters such as H2 production, electrical consumption, stack/outlet pressures, and thermal behavior to gather data for DT modeling and to validate the manufacturer’s claims and observe the transient behavior across the operating spectrum.

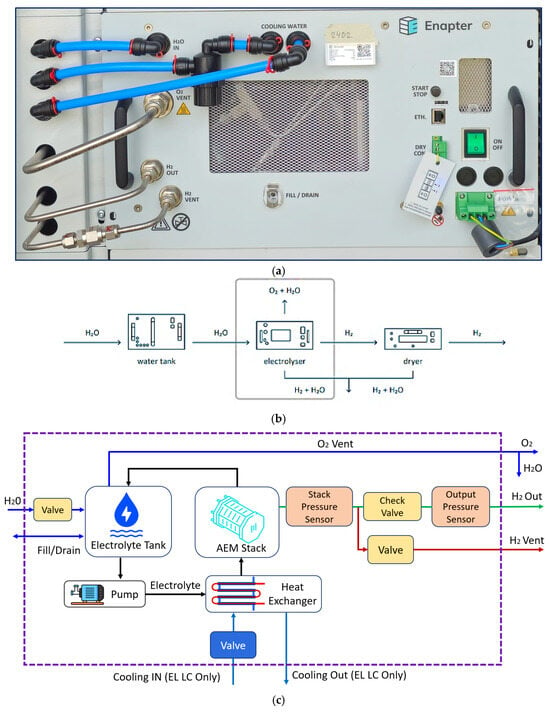

2.2. Architectural Design and Operational Capabilities of the AEMEL

The AEMEL comprises an anode, cathode, AEM, and liquid electrolyte and water feed. Key operational parameters for H2 production include power input, pressure, temperature, and electrolyte concentration. The Enapter EL 4.1 is a compact, rack-mountable AEMEL used within the integrated H2-core system at the University of Stavanger, Norway (Figure 2a). The electrolyzer is connected to a water tank and H2 dryer, working as a single unit. This integrates an AEM stack, internal 3.5 L electrolyte loop, water feed system, cooling, and gas management subsystems (Figure 2b). The minimum stable allowable load is 60% (300 NL/h). Ramp-up (10%) takes about 21 s and ramp-down less than 1 s. At 100% load, it produces 500 NL/h (~1.0785 kg/day) of H2 at 99.9% purity and 35 barg at 25 °C. The output gas contains < 1000 ppm H2O and <5 ppm O2. Water enters (pipeline pressure) at 1.5–2.5 barg, is fed into the tank, and circulates as a 1% KOH solution through the anode side. The cathode remains dry, preventing crossover and ensuring low-moisture H2. Thermal energy (~0.6 kW at 100%) is removed via a liquid–air heat exchanger. Waste heat is either exhausted or recovered via WHR systems (see (Figure 2c). H2 generation starts after a 60 s hydration phase, proceeding through warm-up, ramp-up, and steady state. The stack heats from ambient temperature to 55 °C at ~1 °C/min, reaching nominal flow in 30 min. Pressure builds to 35 barg within 5 min. The 35 barg pressure buildup is not solely due to electrochemical reactions. While reactions generate H2 and O2, the high pressure is achieved through system components like back-pressure regulators and valves that control gas flow and maintain pressure. It is primarily controlled by the system’s mechanical and hydraulic design. Electrolysis splits water into H2 (cathode) and O2 (anode). The oxygen-rich electrolyte recirculates to the tank. Hydrogen flows through a regulated circuit with sensors, check valves, and a solenoid valve maintaining delivery pressure (35 barg or lower). A dedicated H2 vent line purges ~20 NL/day during ramp-up, cooldown, and dewatering. The O2 vent operates at near-atmospheric pressure, releasing ~0.25 Nm3/h of O2 at up to 225 °C, with 10–38 g/h of water vapor and up to 2 vol.% H2, posing flammability risks. This high-temperature O2 exhaust enables WHR. Water is managed via fill/drain ports and dosing valves, consuming ~420 mL/h and refilling ~1.5 L every 3 h. The water must meet the ASTM D1193 Type IV standards, monitored with a conductivity sensor and auto shutoff (Figure 1a).

Figure 2.

(a) Actual EL4.1 electrolyzer unit, (b) connection with electrolyzer, water tank, and H2 dryer, and (c) schematic illustration of AEMEL operation.

2.3. Hydrogen Drying Process of the Enapter DRY 2.1 Unit

Enapter DRY 2.1 is a post-electrolysis H2 dryer, designed to achieve the ISO 14687 purity standards (H2O < 5 ppm, O2 < 5 ppm) [98], delivering > 99.999% molar purity with a dew point below −70 °C (Figure 3a). The system supports drying at 2500 NL/h (35 barg) or 1000 NL/h (8 barg) with 200 W operational power. It uses hybrid Temperature Swing Adsorption (TSA) [99] and Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA) [100] systems with two alternating cartridges (Figure 3b). Each cartridge contains high-capacity adsorbents that remove moisture and trace contaminants. H2 enters at up to 35 barg, activating flow control logic using an input pressure sensor. Automated valves direct flow to either cartridge 0 or 1, based on the regeneration schedule. The active cartridge adsorbs moisture while the second undergoes regeneration via depressurization and heating. Desorbed water vapor is vented through the H2 vent outlet. Check valves ensure unidirectional flow during drying and regeneration. An output pressure sensor and check valves stabilize H2 at the outlet. Switching between cartridges is automated. This alternating-cycle design ensures continuous H2 delivery during regeneration. DRY 2.1 ensures final-stage H2 purification for safe storage, fuel cell compatibility, and compliance with global quality standards [101].

Figure 3.

Enapter hydrogen dryer. (a) Front end and connectors of real unit. (b) Schematic of H2 dryer operation.

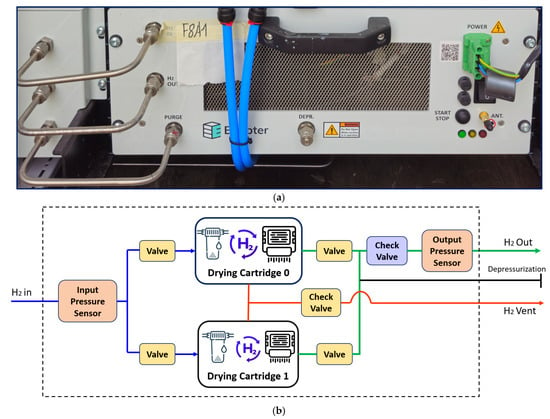

2.4. Description of Polymer Exchange Membrane (EPM) Fuel Cell (IE-Lift 1T/1U)

The FC is an Intelligent Energy IE-Lift 1T/1U, a proton exchange membrane (PEM) type (Figure 4a). The PEMFC provides a nominal PFC of 0.96 kW at 24 V, with a maximum continuous PFC of 1.2 kW at 48 V. It sustains a through-life 1.0 kW output. The FC operates at maximum current of 50 A at ≤ 24 V and 25 A at 48 V, with a selectable Voutput of 24 V, 36 V, and 48 V. H2 consumption is specified as <70 g H2/kWh. The back end of the FC (Figure 4b) illustrates H2 input, PFC output, and communication/control connections. The PEMFC operating temperature ranges from +5 °C to +35 °C. Notably, the PEMFC is not configured for rapid or step-load transitions, rather it is operated at a 100% fixed rate. During testing, the FC’s PFC output was transmitted to the BESS for charging, while low-grade thermal energy from airflow was available for WHR, enabling potential cogeneration.

Figure 4.

(a) Front end of PEMFC, (b) back end of PEMFC and connectors, and (c) battery energy storage unit.

2.5. Battery Energy Storage (BES) Unit

Pylontech US5000 is a modular lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) battery pack, for medium-scale stationary energy storage applications (Figure 4c). It delivers a nominal voltage of ~48 VDC with a nominal energy capacity of 4.8 kWh, of which 4.56 kWh is useable (95% depth of discharge). Standard operation provides a continuous charge/discharge current of 100 A, with transient capabilities of up to 120 A for 15 min and peak loads of up to 200 A for 15 s. It is designed for service life, exceeding 8000 cycles with a design life of 15 years at 25 °C.

2.6. Anion Exchange Membrane Electrolyzer (AEMEL) Mathematical Description

The electrolysis voltage of AEM cells plays a critical role in determining the energy consumption associated with H2 production, thereby influencing the overall economic viability of the system. The AEMEL fundamental concept is detailed in the attached Supplementary Materials (Section S1). Electrochemical behavior is represented by a current–voltage () model, where cell voltage (VE,cell) is the sum of reversible voltage and overpotentials due to activation, ohmic, and mass transport losses [102].

The total cell voltage (Vcell) consists of the Nernst potential reflecting the thermodynamic minimum required for electrolysis and overpotential, which captures additional losses from activation, ohmic resistance, and mass transport limitations (Equation (1)) [102].

The Nernst potential () defines the theoretical minimum voltage required to initiate electrochemical reactions and is primarily influenced by the operating temperature and partial pressures of gas and liquid phases within the cell [103].

Here, is the universal gas constant (8.3145 J·mol−1·K−1), T is the absolute temperature [K], is the number of electrons transferred, and is Faraday’s constant (96,485 C·mol−1). The Nernst equation incorporates the partial pressures of hydrogen at the cathode (), oxygen gas at the anode (), and water () [104].

The total overpotential of an electrolysis cell comprises three primary components: activation overpotential (ηact), ohmic loss (Vohmic), and concentration or mass transport overpotential (Vcon), as given in Equation (3) [104,105].

The activation overpotential () represents the energy barrier associated with hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions (HER and OER), governed by electrochemical kinetics. It is influenced by the electrode material, temperature, and electrolyte composition [106,107]. This kinetic behavior is modeled using the Butler–Volmer equation [103,107], given as follows:

where αa,c are the charge transfer coefficients (a = anode, c = cathode), (A·m−2) is the operating current density, and (A·m−2) is the exchange current density [103,108]. The transfer coefficients () vary linearly with temperature (K) as follows:

Ohmic overvoltage, Vohmic, arises from the resistances within the electrolysis cell components (electrolyte, electrodes, and contacts), and is quantified by Ohm’s law [49]:

Here, rKOH denotes the resistance of the liquid electrolyte (typically a dilute KOH solution) and rmem represents the resistance of the AEM [107]. The electrolyte resistance can be expressed as follows:

The electrolyte resistance depends on the electrode and membrane spacing (dam and dcm in [m]) [104], the electrode cross-sectional areas (Sa, Sc in [m2]), and the ionic conductivity of the electrolyte σKOH (S·cm−1) [103]. The conductivity of KOH is a function of the electrolyte temperature and molar concentration (mol·m−3) and is modeled using a modified empirical correlation based on experimental data (Gilliam et al., 2007 [109]; Henao et al., 2014 [110]).

Currently, membrane resistance accounts for the dominant portion of total ohmic losses in AEMWE cells (Cho et al., 2017 [111]; Xu et al., 2018 [112]). This resistance is calculated as

where represents the AEM thickness (m), represents the membrane surface area (m2), and represents the conductivity (S·m−1). Membrane conductivity (σm) is governed by the hydration level (), defined as the number of water molecules per sulfonic acid group and operating temperature [K]. For a fully hydrated membrane, λ typically ranges from 14 to 21 (typically 18) [103,107]. The conductivity is expressed as

Mass transfer overvoltage arises from two-phase flow limitations within AEMEL, where counter-flowing water and O2 streams cause diffusion hindrance and additional energy losses [104]. It is defined as the sum of anodic and cathodic contributions [107]:

where and are the local concentrations of H2 and O2 at the membrane–electrolyte interface [103], and the subscript “” indicates the standard reference conditions [102]. The values/parameters for the above equations can be found experimentally, or through AEMEL manufacturers [107]. At the commercial level, an AEMEL stack is modeled using an accumulation of several individual cells called a stack [105]. For a commercial-level operating AEMEL unit, the overall (system) efficiency ηAEMEL is typically defined as follows [104]:

where is the H2 flow/production rate (Nm3/h); is a high heating value, typically ~12.745 kWh/Nm3 [108]; Vstack is the operating AEMEL voltage (V); and is the AEMEL operating current (A) [107].

2.7. Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell (PEMFC) Mathematical Description

The PEMFC fundamental concept is detailed in the attached Supplementary Materials (Section S2). In PEMFCs, the open-circuit voltage, also referred to as the Nernst voltage (), defines the maximum theoretical voltage output of a PEMFC and is expressed as a function of temperature and gas partial pressures [113,114].

Here, ΔG is the Gibbs free energy, is the entropy difference, T0 denotes the ambient temperature, TFC is the FC outlet temperature, and , represent the number of electrons transferred and gas partial pressures, respectively. In practice, the actual cell voltage is reduced by various irreversible losses [114].

The activation overpotential represents the initial voltage loss associated with overcoming the energy barrier for electrochemical reactions [115]. It is influenced by the operating temperature, pressure, and catalytic properties of the electrodes, and it is estimated using the following semi-empirical expression [116,117]:

Here, the current flow through the PEMFC is (A), the oxygen concentration at the membrane/cathode is , and is a semi-empirical coefficient related to the electrochemical kinetics and catalytic characteristics of the fuel cell electrode [116,117,118].

Here, (A/cm2) is the PEMFC operating current density, the PEMFC surface area (single cell) is given by (cm2), and is the concentration of H2 at the anode/membrane interface [119,120]. Concentration overpotential arises from fluctuations in H2 concentration at the electrode surface during reaction, leading to mass transport limitations. This voltage loss is expressed in Equation (20), where is the maximum current density at the PEMFC [117].

Ohmic losses result from resistance to ion and electron transport within PEMFC components, including ionic resistance in membrane and both ionic and electronic resistances in the electrodes and interconnections [119]. This voltage loss can be defined as

Here, denotes the constant component of the cell’s resistance, while represents the resistance influenced by membrane hydration and is calculated as follows [118,119]:

where (cm) is the membrane thickness and denotes the specific membrane resistance, which can be expressed as follows [116]:

where is an empirical constant. The actual cell voltage is obtained by subtracting the total voltage losses from the Nernst voltage, as follows [117]:

The total power output from a stack of multiple fuel cells can be calculated as follows:

The heat generated by the PEMFC can be determined through an energy balance, expressed as follows [118,121]:

is the electrochemical energy released by the chemical reaction, and is the difference between the PEMFC’s inbound and outbound H2 molar rate.

The electrical efficiency of PEMFC is defined as follows [116,121]:

2.8. AEMEL Digital Twin Model

A Python-based DT model was developed by the authors to simulate the operational behavior of the AEMEL EL4.1, and it was validated using experimental data. This Python model one-to-one predicts the physical system using feed-in data from the electrolyzer. It enables performance analysis across a 60–100% load range for the AEMEL. The model is built on experimental data, including H2 production (NL/h), power input (kW), outlet and stack pressures (bar), and electrolyte and coolant temperatures (°C). Linear interpolation maps the operational capacity to each output parameter, allowing continuous prediction across the defined range. The user input is only the desired capacity; thus, the output prompts real-time predictions and calculation of the Electrochemical Conversion Efficiency (ECE) based on the LHV of H2 (10.8 MJ/Nm3). Safety thresholds trigger warnings if the temperature exceeds 55 °C or the pressure surpasses 35 bars. The DT provides normalized bar charts for quick visual assessment of each run and logs all outputs for cumulative trend plotting. The results are then exported as an Excel file. This tool enables virtual testing, supports diagnostics, and aids in the optimization of AEMEL operations. Different DT models, methods, and construction methodologies for electrolyzers are addressed by D. Monopoli et al. (2024) [122].

2.9. PEMFC Digital Twin Model

For the PEMFC, a physics-informed AI-based hybrid DT model was developed and simulates the real-time behavior of a PEMFC system using a supervised machine-learning (ML) approach centering on an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) [123]. A similar ANN architectural approach was utilized by M. Castilla et al. (2024) [124]. The PEMFC-DT was developed in Python, which enables accurate prediction of the key performance parameters, i.e., current, voltage, power output, and outlet temperature, based on two primary input variables: anode pressure and inlet temperature. An ANN-based PEMFC-DT is built on experimentally collected data. The dataset is pre-processed by converting variables into numeric format, handling missing values, and normalizing both input and output features using MinMax scaling. The ANN model was structured as a feedforward network (FFNN) with three (3) hidden layers (32-64-32 neurons) using ReLU activation functions and trained using an Adam optimizer and mean squared error (MSE) loss over 200 epochs [125]. Once trained, the model captures nonlinear interactions between operating conditions and system outputs, providing reliable generalization across unseen data. Descriptive ANN modeling can be found in an article by the authors: A.H. Samitha Weerakoon et al. (2024) [126]. Prediction is constrained by manufacturer-defined operational boundaries, including anode pressure being limited to 1.6 bar and inlet temperature to between +5 °C and +35 °C, which, if exceeded, simulates a real-world shutdown or fault condition. The model outputs are the LHV-based FC efficiency employing predicted power output and the user-defined H2 consumption rate (NL/h). The PEMFC-DT thereby provides both data-driven and physics-informed insight into PEMFC operation. All neural-network training and DT computations were carried out using a standard laptop (HP EliteBook 845 G10, AMD Ryzen 5 7540U @ 3.2 GHz, 16 GB RAM, 477 GB SSD, Windows 11 Education 23H2). For the deployed DT application, generating a complete set of predictions typically requires only about 2–3 s, and the proposed models are able to run in (near) real time without any dedicated GPU or high-end hardware.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. AEMEL Experimental Analysis

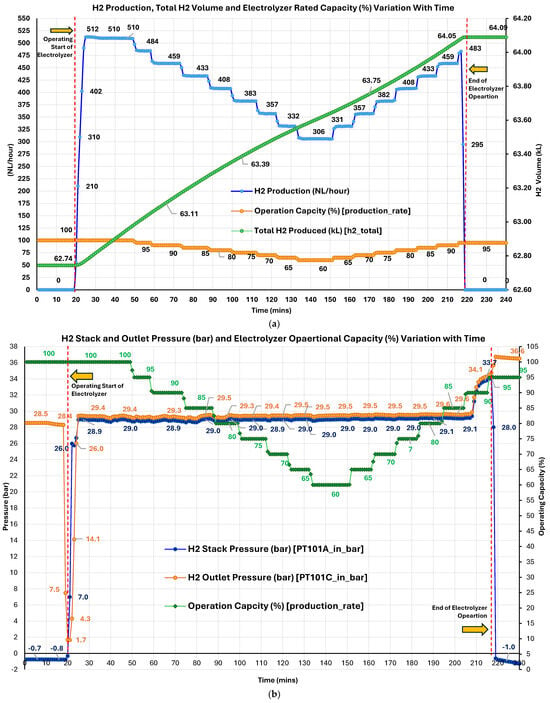

3.1.1. AEMEL H2 Production Rate, Cumulative Volume, and Capacity Utilization

Figure 5a illustrates the real-time H2 production (NL/h), total cumulative H2 produced (kL), and operational capacity (OP%) variation with time. The operational performance of the AEMEL was evaluated under dynamic loading, demonstrating stable and responsive behavior across its full operating range. The system, initially set at 100% capacity with H2 production ramping from zero to 510 NL/h within minutes, indicates rapid start-up and minimal transient lag. Under steady-state full-load conditions, production remained highly consistent (509–512 NL/h). A subsequent stepwise reduction in OP%, in 5% increments down to 60% (manufacturer-defined minimum OP% threshold), showed a smooth and proportional decline in H2 output, with no signs of instability or control degradation. At 60%, the electrolyzer remained stable, producing ~305 NL/h. The reverse sequence (60% to 95%) yielded similarly consistent results, confirming hysteresis-free control characteristics. Notably, upon reaching 95% during the ramp-up phase, H2 production automatically ceased due to the H2 storage tank reaching full capacity, activating system-level shutdown. This safety-driven interlock performed as intended, overriding manual setpoint control. Cumulative H2 production increased monotonically from 62.74 to 64.09 kL, resulting a net yield of ~1.35 kL.

Figure 5.

(a) Real-time H2 production rate (NL/h), total cumulative H2 produced (kL), and operational capacity percentage over time; (b) real-time hydrogen stack pressure (bar) and outlet pressure (bar) variation with operational capacity (%).

3.1.2. AEMEL Stack and Outlet Pressure vs. Capacity

In parallel with H2 production dynamics, the electrolyzer exhibited stable and predictable pressure characteristics throughout the load-cycling experiment (Figure 5b). At 100% OP%, both H2 stack pressure (Pstack) and outlet pressure (Poutlet) rose rapidly from near-ambient to stable values of ~28.9 bar and 29.4 bar, respectively, demonstrating the electrolyzer’s fast pressurization capability. Throughout the test, both pressures remained highly stable, with minimal variance (<0.1 bar), indicating tight control and effective pressure regulation. As the system underwent a stepwise reduction from 100% load to its minimum threshold 60%, both stack and outlet pressures exhibited only minor fluctuations. Pstack remained within 28.7–29.0 bar, while Poutlet remained at ~29.2–29.5 bar. This pressure consistency across a broad turndown ratio confirms the system’s capability of maintaining performance and gas-handling integrity during dynamic load transitions. During the subsequent upward ramp from 60% to 95%, a slight pressure increase was observed, followed by a marked and rapid rise in both Pstack and Poutlet beyond 33 bar and 36 bar (max 37 bar), beginning at ~90% capacity. This was basically due to H2 storage approaching its maximum capacity, triggering automatic AEMEL shutdown. After the shutdown, Pstack dropped below atmospheric levels, stabilizing at −1.8 bar due to backflow prevention or system purging dynamics, while Poutlet remained elevated, constant at 36 bars. Negative readings do not reflect actual vacuum or sub-atmospheric conditions; instead, they are likely a result of sensor baseline drift or offset error when the internal H2 line is fully depressurized and disconnected from active gas flow. Pressure overshoot preceding shutdown indicates a well-functioning internal feedback mechanism that recognizes tank pressure constraints and disengages H2 generation. The absence of pressure instability, oscillations, or control lag throughout the experiment highlights the robustness of the electrolyzer’s control architecture and mechanical sealing.

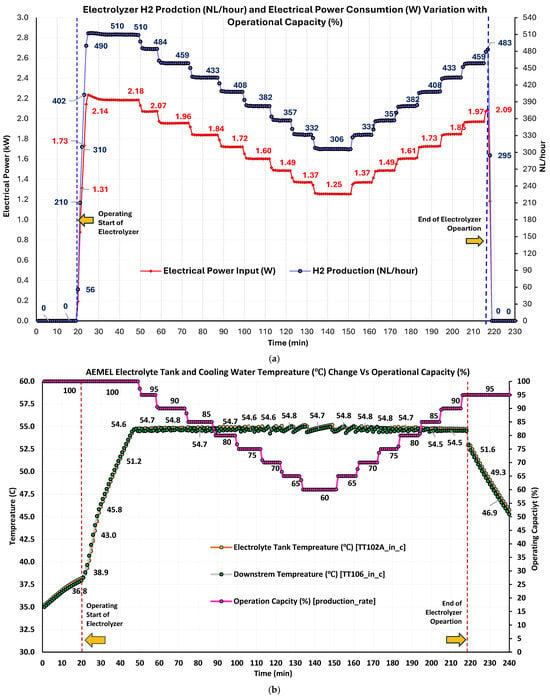

3.1.3. AEMEL Electrical Input vs. Hydrogen Output

The relationship between the AEMEL electrical power input (PEL,in) and H2 production is illustrated in Figure 6a. Upon start-up, the electrolyzer exhibits a rapid increase in both PEL,in and H2 generation, with production reaching 512 NL/h at a stabilized PEL,in of ~2.18–2.24 kW during 100% OP%. This stage demonstrated exceptional load acceptance, with near-linear scaling in both electrical and H2 outputs and no noticeable overshoot or instability. As OP% was reduced (5% steps), H2 production and PEL,in decreased proportionally. At the minimum OP% of 60%, H2 ~306 NL/h, it corresponded to PEL,in~1.25 kW, indicating that the system maintained efficient operation at PL. Also, step-down and subsequent step-up trajectories displayed strong symmetry, confirming hysteresis-free ramp-up/down behavior. The system’s efficiency, denoted by H2 yield per unit of power, remained consistent, due to the efficient electrochemical conversion process. The significant drop in PEL,in and H2 output at the end coincided with internal shutdown with a fully charged H2 tank. Following this event, both PEL,in and production fell to zero, regardless of setpoint, verifying safety and interlock protocols’ correct enforcement. Throughout dynamic loading, no irregularities were observed in either electrical consumption or production. The electrolyzer maintained stable and efficient performance across a broad operating envelope.

Figure 6.

(a) Real-time electrical power input (kW) vs. H2 production rate with varying operational capacity (%); (b) real-time electrolyte tank temperature and downstream coolant temperature variation.

3.1.4. AEMEL Thermal Profile of Electrolyte Tank and Downstream Water

Thermal regulation of the AEMEL was monitored via the electrolyte tank (TEL,tank) and downstream coolant water (TEL,coolant) temperatures throughout a complete loading cycle (Figure 6b). Upon system initiation, the temperatures began rising gradually from ambient values (35.2 °C electrolyte and 35.0 °C coolant), demonstrating a rapid increase as the unit ramped up to full capacity. Within the first 40 min, TEL,tank reached ~54.7 °C, with TEL,coolant stabilizing at ~54.5–54.8 °C. This thermal ascent corresponded to a rapid H2 production ramp, reflecting electrochemical and resistive heating associated with full-load electrolysis. Notably, during the entire reduction of OP% from ~100% to 60%, both temperatures (thermal signals) fluctuated within a narrow band (±0.3 °C), due to excellent thermal management even as the electrical and H2 outputs decreased significantly. Thermal stability across variable loading prevents thermal stress on membranes and catalysts, a critical aspect for longevity in AEM-based electrolysis [127]. When OP% changed from 60% to 100%, the thermal measurements again remained consistent, confirming a symmetric thermal response and stable control. Temperatures peaked slightly above 55.1 °C during the final ramp-up phase, with no sign of overheating or thermal runaway. Throughout the test cycle, the minimal temperature gradient (~0.2–0.4 °C) between TEL,tank and TEL,coolant highlights the high-efficiency heat exchange design. Following the system’s automatic shutdown, both TEL,tank and TEL,coolant exhibited gradual and linear decline, from ~54.7 °C to ~36.8 °C in the post-operation cooldown phase. The symmetry and slope of the cooldown curve (after 220 min) indicate well-regulated thermal inertia after shutdown. Table 2 compares key observations from experiments and manufacturer’s specifications.

Table 2.

Summary of AEMEL key observations and numerical metrics.

The deviations observed between the experimental results and manufacturer’s specifications are well within normal operating variability for commercial AEMELs. The marginally higher H2 production rate (+2.4%) is due to favorable stack temperature conditions and standard flow-sensor tolerances, while the lower power consumption (−10.8%) replicates improved steady-state efficiency and conventional nominal ratings provided by the manufacturer. The operating pressure remained below the maximum allowable 35 bar because the tests were conducted under standard laboratory safety limits; also, the elevated coolant temperatures are due to ambient laboratory conditions and heat accumulation during extended runs. Overall, these differences are expected and fall within acceptable engineering tolerances for real-world electrolyzer operation.

3.1.5. AEMEL Comparison of Experimental Results with Theoretical Modeling

Experimental analysis of the AEMEL exhibits strong agreement with theoretical modeling, indicating stable and realistic operation. H2 production remained between 509 and 512 NL/h, while PEL,in ranged from 2.18 to 2.24 kW. Utilizing LHVH2 (12.745 kWh) and the efficiency equation (Equation (13)), the observed SEC of AEMEL was ~15.7 kWh/Nm3, falling within the practical operating range for AEMELs (12–16 kWh/Nm3) [103,107]. This theoretically translates into an energy efficiency ≈ 81%. But the actual practical performance is lower, achieving an of ~68.56%, producing 0.512 Nm3 of H2 with 2.1 kWh of input power aligning with industrial benchmarks [107]. Thermodynamically, the reversible baseline voltage of each cell was estimated from the Nernst equation (Equation (2)), where TEL(K) ~314.35–327.95 K from 41.2 °C to 54.8 °C, ≈ 28.66–28.98 bar from Pstack and ≈ 2.422–2.435 bar from water inlet pressure, and is assumed to be half of due to stoichiometric electrolysis. These values yield a theoretical VE,cell (Equation (1)) of ~1.18–1.21 V. With an observed total Vstack of around 41.2 V, the system likely consists of approximately 23 cells, which corresponds to a VE,cell of ~1.79 V, which matches known commercial AEM stack configurations [108]. Beyond the thermodynamic minimum, the actual VE,cell includes various loss components. The modeled by the Butler–Volmer equation (Equation (4)) depends on the charge transfer coefficients () which vary with temperature (Equations (5) and (6)). Although and (A·m−2) are not directly measured, they can be estimated if the AEM surface area (m2) is known. The literature values suggest that typically contributes 0.1–0.3 V per cell [103], especially with stable currents of around 53 A and low thermodynamic voltage input. , a major contributor to total overpotential (Equation (7)), is governed by rKOH (Equation (8)), where the conductivity σKOH is a temperature- and concentration-dependent conductivity. As TEL,tank rises, electrolyte conductivity increases, reducing rKOH and associated losses [107]. Similarly, (Equation (10)) depends on Tm, Am, and membrane conductivity which varies with temperature and hydration level λ. Assuming a typical hydration number λ ≈ 18 and using the exponential model in Equation (11), membrane conductivity increases with temperature, which matches the observed gradual drop in voltage per ampere and contributes to the observed efficiency gain. Although the experimental dataset lacks local gas concentration data, the system’s stable performance (consistent IE, VEL, and H2 production) indicates that the concentration overpotential is negligible under nominal conditions, . The influence of temperature is clearly visible within the experimental data. TEL,tank and TEL,coolant increase from 41.2 °C to 54.8 °C and 41.9 °C to 54.5 °C, respectively, correlating to a slight increase in efficiency (~0.5%) and a slight reduction in VEL per unit of IE. This behavior is theoretically expected, as higher temperatures reduce the activation energy for HER and OER reactions and improve ionic conductivity in both the membrane and the electrolyte, thereby lowering and .

3.2. PEMFC Experimental Analysis

3.2.1. Performance Optimization Cycle and Water Management in PEM Fuel Cells

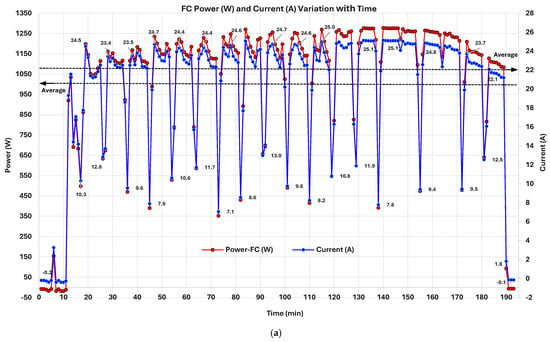

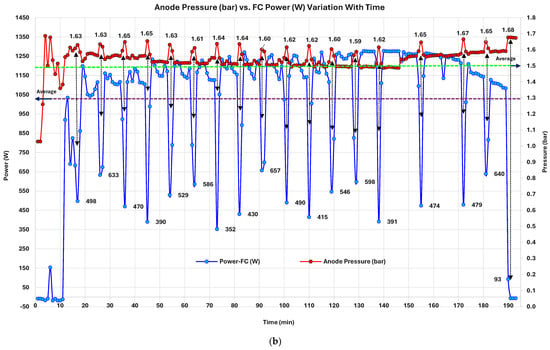

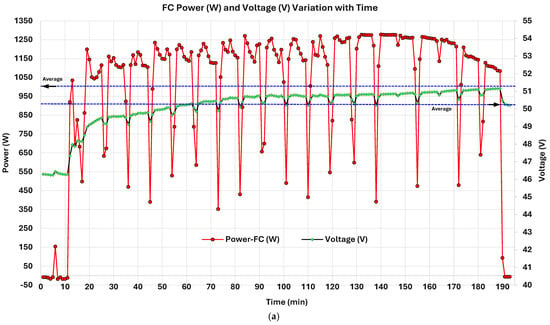

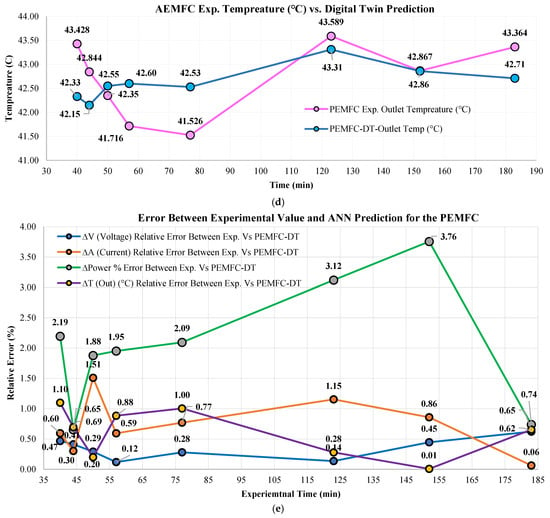

Time-series analysis of the PEMFC revealed that periodic power, voltage, and current dips occurring at intervals of approximately 7–8 min (Figure 7 and Figure 8) and returning to nominal levels are due to the Performance Optimization Cycle (POC). This phenomenon is a cyclic reaction (mechanism) preventing water accumulation specifically at the cathode of a PEMFC. In PEMFCs, this is defined as “water flooding” at the cathode side [128]. However, manufacturers utilize different strategies to mitigate this issue. The IE-Lift 1T/1U PEMFC utilizes load shedding through controlled (Figure 7a) [129] and irregular forced H2 convection at the anode (Figure 7b) [130] using mechanisms at defined intervals. Water management in general remains a critical challenge in PEMFCs [131]. Cathode flooding is when liquid water accumulates in GDLs and flow channels due to inadequate removal, obstructing gas transport paths and masking electrochemical reaction sites, leading to substantial performance loss and, sometimes, irreversible degradation [128]. Because PEMFCs operate at relatively low temperatures (typically 60–90 °C), the formation of liquid water is unavoidable. Since water generation is proportional to current density (), flooding is particularly severe during peak-load intervals [129]. An imbalance between transient or peak-current conditions leads to uneven water accumulation, increasing the risk of cathode flooding [132]. Interestingly, the classical power–current () curve of a PEM fuel cell is bell-shaped, reflecting optimal performance at intermediate loads and growing inefficiencies at peak loads often due to mass transport limitations like water flooding [133]. It exposes a strategic opportunity for temporary de-loading (load shedding through controlled IFC cycling) to help reduce cathodic flooding by reducing water production and enhancing gas-phase water removal. Regulating (A/cm2) in such scenarios serves a dual purpose. First, it slows water generation, allowing accumulated water to evaporate or be purged. Second, the lower results in reduced water output, reducing the required air/gas pressure for effective purging and minimizing mechanical stress on the system [128]. Supported by a forced H2 purge at the anode side, sudden pressure spikes in H2 supply promote water discharge and the fusion of droplets [130]. Moreover, load shedding via regulation has the added advantage of a fast dynamic response. It can match rapid changes in system state such as anode pressure fluctuations or humidification shifts, allowing for fine-tuned control. This theoretical behavior governs the tested PEMFC water flooding and prevention. This concept is embodied in the PEMFC through manufacturers using POCs, which are primarily designed to mitigate water flooding by temporarily reducing the current load (load shedding). The POC cyclically reduces and with anode H2 pressure spikes, at fixed intervals, allowing accumulated water to clear, especially from the cathode side and water-accumulated pathways, preserving long-term system stability and maximizing stack durability. The three figures together strongly support this mechanism. Initially, Figure 7a, is deliberately ramped down (cyclically) every 7–8 min to lower water production. The power curve is well aligned with the curve. In Figure 7b, H2 forced purging at an elevated ~1.6 bar pressure prevents anode flooding. In Figure 8a, remains mostly stable with minor fluctuations; membrane integrity and electrochemical kinetics remain intact. The authors’ tested 1 kW PEMFC unit water-flooding prevention mechanism is validated with findings from Huicui Chen et al. (2023) [129] and Hua Yang et al. (2025) [130]. Further expertise on PEMFC water-flooding phenomena can be found in O.S. Ijaodola et al. (2019) [133].

Figure 7.

PEMFC: (a) power (W) and current (A) variation; (b) anode pressure and power (W) variation with time.

Figure 8.

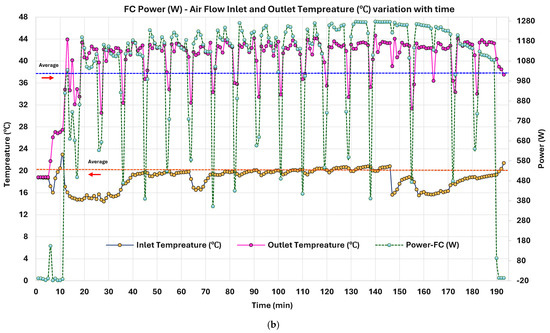

PEMFC: (a) power (W) and voltage (V) variation; (b) FC power (W) and inlet and outlet airflow temperature (°C) variation with time.

3.2.2. PEMFC Power (W) and Current (A) Variation with Time

Water management depends on and its cyclic fluctuation identically matches with . After each valley, the next summit is a maximum to facilitate optimized PEMFC operations. Figure 7a shows that averages ~19.93 A with a standard deviation of 7.17 A, indicating notable variability coinciding with power fluctuations. A strong positive correlation (approximately 0.999) between FC power () and current emphasizes a near-perfect linear relationship. This implies that variations in are directly and proportionally associated with changes, reinforcing the predictable and controlled nature of PEMFCs. During stable operation, ranges between 1100 and 1250 W, corresponding closely to in the range of 22–25 A. The output peaked at 26.8A, slightly above the rated limit of 25 A @ 48 V. The mean remained around 23.2 A, aligning with the manufacturer’s expectations. During periodic POCs, both and deliberately dropped (350–600 W and 8–14 A), as part of PEMFC water management. Statistical distribution indicates a median of 22.87 A and a median power output of ~1156 W, both notably higher than their averages, suggesting skewness due to POC low-power events.

3.2.3. PEMFC Anode Pressure (Bar) vs. FC Power (W) Variation with Time

PEMFC archives an average power output (PFC) of ~1065 W, with significant variability (standard deviation ~364 W), highlighting periodic power fluctuations with a POC every 7–8 min. Anode pressure averages ~1.55 bar, varying moderately (standard deviation ~0.076 bar), reflecting stable gas management (see Figure 7b). The PFC distribution shows a median of ~1156 W, higher than the mean, due to low-power cycles lowering the average. Anode pressure shows a median of ~1.55 bar, closer to the mean, indicating stable control outside of planned transients and stabilizing in short intervals. Correlation analysis yields a weak negative coefficient (–0.0383), suggesting minimal linear dependence between PFC and anode pressure, despite inverse fluctuations during POCs. These software-induced POCs coincide with elevations in anode pressure to 1.65–1.68 bar. During stable operation, the PFC stabilizes within 1100–1250 W, and anode pressure remains consistently at 1.53–1.55 bar, ensuring steady-state operational efficiency.

3.2.4. PEMFC Power (W) and Voltage (V) Variation with Time

Figure 8a highlights the relationship between and . The average of ~50.13 V, with a relatively low standard deviation of 1.17 V, indicates consistent voltage management by the FC controller. and show a strong positive correlation (0.719), confirming that higher voltage corresponds to increased power. and time correlate at 0.76, indicating that voltage stabilizes gradually. A 20-min rolling correlation exceeds 0.94, revealing locally strong linearity between voltage and power. These trends align with electrochemical behavior, though less tightly than – correlations due to the established POC mechanism. Throughout the experiment, was consistent ~48 V (aligning with the manufacturer’s specifications), fluctuating between ~49–51 V. Cyclic reductions in power and voltage due to POC briefly reduced the voltage to around 46 V. These are controlled recalibrations rather than instability. The median of ~50.62 V closely aligns with the mean. These observations confirm effective voltage management in the PEMFC.

3.2.5. PEMFC Power (W), Air Flow Inlet, and Outlet Temperature (°C) Variation with Time

Figure 8b shows an average inlet air temperature (TIN_FC) of ~18.61 °C, and an outlet stabilized at 40.13 °C, giving a consistent thermal gradient (∆T) of 21.52 °C. This highlights effective heat generation and removal, acting as a reference for assessing thermal efficiency. Power–temperature interactions exhibit strong dependencies. During stable high-power output (1100–1275 W), outlet temperatures (TOUT_FC) consistently ranged between 42.5 and 44.5 °C, indicating thermal equilibrium. Regression of the power versus outlet temperature gives an R2 > 0.86, showing a clear linear trend. Time-segmented averages show changes in TOUT_FC lag behind power changes by less than two minutes, crucial for developing real-time thermal control. Derivative correlation between d /dt and dTOUT_FC/dt exceeds 83% of intervals, further supporting its applicability for model-predictive control (MPC). Superimposed on this thermal behavior is the POC, characterized by periodic power dips. These dips are mirrored in TOUT_FC drops, confirming that POC temporarily reduces the reaction heat due to reduction. TIN_FC remains unaffected during these intervals. This shows that the temperature decrease is caused by internal load shifting rather than external air supply variation. The inlet–outlet temperature gap quickly re-establishes after each POC, indicating rapid system recovery and thermal equilibrium restoration. The repeatability of the ∆T profile is favored by modular PEMFC-CHP integration with low-grade WHR in higher-capacity PEMFCs (e.g., 10–100 kW).

3.2.6. PEMFC Comparison of Experimental Results with Theoretical Modeling

The key average records a 50.53 V voltage, 22.90 A current, and PFC ~1157.6 W, with H2 supplied at 1.527 bar. The inlet and outlet temperatures averaged 18.67 °C and 42.34 °C, respectively, indicating a 23.67 °C rise due to electrochemical and resistive heating. Theoretically, the Nernst potential () defines the thermodynamic maximum voltage and depends on the FC’s and partial pressures (). Equation (14) shows that raising the temperature slightly lowers the first term but enhances the overall voltage due to faster kinetics and improved gas diffusion. Greater increase the voltage, while high humidity () reduces it. For this PEMFC operating at ~42 °C and 1.527 bar, the calculated is 1.335 V per cell. However, real-world losses reduce this voltage. The PEMFC , given by Equation (15), reflects energy barriers at the electrodes. As increases, activation loss rises; increasing the temperature lowers it; higher values reduce it; and β (Equation (16)) expresses the kinetic behavior and catalytic effect of the electrode. Higher catalytic activity (higher β) reduces . Also, β accounts for , and (Equation (18)) adjusts the slope. A higher and FC temperature improve (Equation (19)), reducing activation losses. Due to unavailable gas concentration data (through experiments), a literature-based 0.35 V per cell was used. PEMFC ohmic losses are caused by resistance across the membrane and interconnections as captured by Equation (21). is influenced by (higher current, more loss), membrane thickness (thicker = more resistance), and hydration state (Equation (22)). The is itself a function of and (Equation (23)). Dehydration causes sharp rises in , while adequate hydration (regulated by relative humidity and stack temperature) lowers it. The of PEMFC becomes significant at high and is modeled by Equation (20). In this PEMFC, with moderate , this term is negligible (~0.0017 V). Combining all losses, (Equation (24)) is approximately 0.912 V per cell and 45.6 V total per estimated 50-cell stack, consistent with the experimental value of 50.53 V. The stack power (Equation (25)) aligns with the recorded 1157.6 W. Waste heat, modeled by Equation (26), confirms significant thermal output through a ~24 °C rise across the stack, imposing effective cooling. WHR potential becomes significant as PEMFC power increases. The given by Equation (27) is based on <70 g H2 per 1.2 kWh, and the actual H2 use for 1.1576 kWh is 0.06738 kg, with an HHV of 39.41 kWh/kg, giving an input energy of 2.655 kWh. Thus, = 1.1576/2.655~43.6%, consistent with commercial expectations [134,135]. As this analysis exhibits, increasing improves voltage and by reducing activation and ohmic losses; conversely, drying the membrane (too little humidity) increases resistance and reduces performance. Similarly, high current draws on stress gas delivery and hydration systems, while underutilization reduces output and .

3.2.7. Comparison of Commercial PEMFC Unit-Based Experimental Results

Several studies have tested PEMFC systems in the ~1.0–1.2 kW range. Yilanci et al. (2008) [136] examined a 1.2 kW Nexa PEMFC without humidification and reported an of ~30% at 1.0 kW under transient load for half an hour. Tang et al. (2010) [137] reported a 1.2 kW Nexa PEMFC under transient and dynamic loads but did not report or duration. Özgür et al. (2018) [138] tested a 1.0 kW self-humidified PEMFC, showing an of ~45.58% under short-term transient operation (see Table 3). In comparison, the present study tested a commercial 1.0 kW PEMFC at steady-state and rated power for over 190 min, reaching a stable efficiency of 43.6% under real-time controls and an anode H2 pressure of 1.5–1.54 bar in STP. This study stands out by identifying clear signs and preventive mechanisms of PEMFC water-flooding issues in commercial units. Unlike earlier studies, this work reveals and reports the results of a more recent PEMFC model, with over 3 h of extended-continuous uninterrupted operation in an actual test site, solidifying realistic feedback from the PEMFC. These results will be critical for improving the system-level design and control of PEMFCs in H2 energy applications and microgrids.

Table 3.

Comparison of PEMFC experimental research studies conducted on commercial FC units.

3.3. Integrated Hydrogen Fuel Cycle Analysis: AEMEL and 1.0 kW PEMFC with Battery Storage

The integrated test rig operates cyclically, i.e., H2 is produced, stored, and then used in the FC to charge the BESS. AEMEL produces 0.04494 kg/h of H2, requiring ~26.2 h to fill a 16-cylinder rack (1.178 kg capacity at 29 bar). The PEMFC consumes approximately 0.07 kg of H2/kWh, enabling ~16.8 kWh of output from a full H2-cylinder rack. Charging the battery requires 0.336 kg H2, allowing ~3.5 full battery cycles per rack. The PEMFC charges the battery at 1.0 kW over ~4 h 48 min. Operational logic triggers the FC to start below 15% battery and stops at full charge. A summary of the results is illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of H2-based system performance metrics.

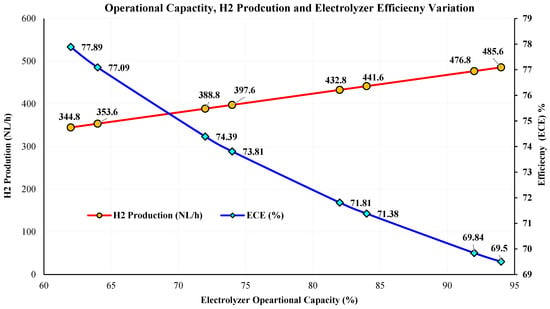

3.4. AEMEL Digital Twin Performance Analysis

The AEMEL-DT was computationally tested against experimental values across a series of arbitrarily selected OP% at 62%, 64%, 72%, 74%, 82%, 84%, 92%, and 94%, and results are illustrated in Table 5. To ensure robust interpolation across the full 60–100% operating range, the interpolation nodes were selected at off-nominal load points (62–94%) rather than exactly at the manufacturer’s setpoints. These points provided stable experimental plateaus, captured real operating variability, and offered uniform coverage of the full operating domain. As the AEMEL demonstrated linear and predictable behavior, a small number of well-spaced nodes was sufficient to construct an accurate interpolation model (<3.8% deviation). For each setpoint, the DT predicted the H2 production rate (NL/h), PEL,in (kW), and (ECE) (%). The comparison (Table 6) demonstrates excellent agreement between DT outputs (DT-code exact outputs are attached in the Supplementary Materials, Section S3) and experiments. For instance, at 62%, the DT produced 344.80 NL/h of H2 with PEL,in~1.33 kW and 77.89% efficiency, closely matching the experimental data of 340.66 NL/h, 1.346 kW, and 76.26%. Similarly, at 94%, the DT predicted 485.60 NL/h H2, PEL,in~2.10 kW, and 69.50% efficiency, compared to experimental values of ~479.78 NL/h, 2.12 kW, and 68.66%. Across all tested setpoints, the relative deviation between the DT and the physical performance remained below <1.2%. The AEMEL-DT’s predictions follow the expected electrochemical behavior with H2 output and PEL,in with capacity, while gradually decreases at higher loads due to thermal and resistive losses. Figure 9 shows increase in as the operational capacity (%) decreases. At lower loads, the AEMEL experiences reduced (A·m−2), which lowers in the stack, resulting in a favorable V-to-I ratio and thus less electrical energy required per unit of H2. Hence, thermal losses are lower; thus, SEC (kWh/Nm3 H2) decreases, yielding a higher ECE (%). However, the efficiency gain comes at the cost of reduced H2 throughput, a trade-off between production rate and conversion efficiency. This validation confirms that the AEMEL-DT replicates the physical electrolyzer’s behavior accurately and is suitable for use in system-level studies and forecasts.

Table 5.

Digital twin outputs of the AEMEL across varying operational capacities (%).

Table 6.

AEMEL-DT output comparison with experimental results.

Figure 9.

AEMEL operational capacity, H2 production, and efficiency variations with time.

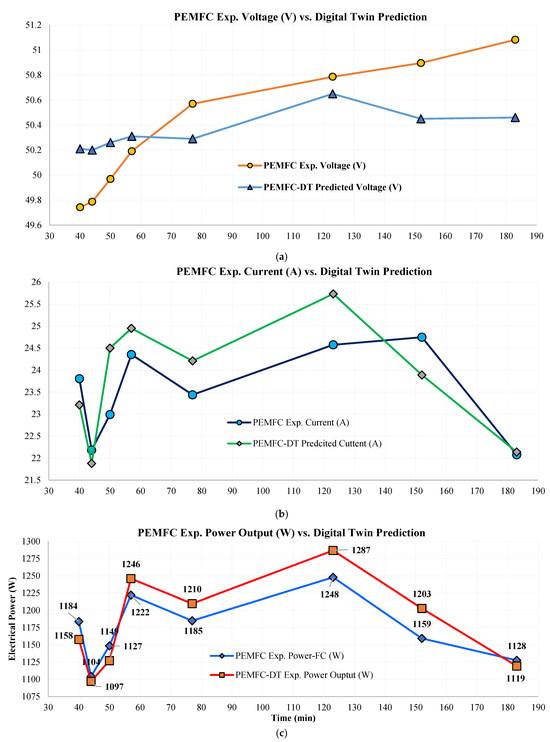

3.5. PEMFC Digital Twin Performance Analysis

The ANN-based PEMFC-DT was compared with experimental data. Eight (8) data points were compared against model predictions for (V), (A), (W), and (°C). prediction (Figure 10a) demonstrated excellent agreement, with absolute errors ranging from as low as 0.12 V at 57 min to a maximum of 0.62 V at 183 min. The majority of deviations remained <0.5 V; the 48 V~50 V range ±0.5 V error especially is negligibly small, demonstrating the PEMFC-DT’s capability to replicate behavior with superior precision. predictions showed a similar pattern (Figure 10b), with absolute errors ranging 0.06 A to 1.51 A. The PEMFC-DT only slightly overestimated in two instances with a 1.51 A and 1.15 A difference (>75% of predictions for remains < 1.0 A accuracy range). The PEMFC-DT maintained an excellent reliable trend-following ability in capturing transient electrical responses. prediction (Figure 10c), a compound metric, exhibited robust agreement with experimental values. As is a compound metric, its accuracy reflects cumulative effects from upstream predictions. The relative errors between 0.65% (absolute error ~7.19 W) and 3.76% show a maximum difference of 43.55 W, which is relatively small within the context of a 1.0 kW PEMFC. Most predictions fell within a ±2.5% band, highlighting the ANN model’s accuracy in capturing PEMFCs’ complex electrochemical power dynamics. Thermal predictions were measured (Figure 10d) by , where the absolute errors remained <1.10 °C across all test points, with the smallest ΔT of ~0.01 °C. This consistency in temperature estimation highlights the DT’s reliability for integration into thermal management strategies. A summary of average errors presents ~0.35 V, ~0.73 A, ~2.05 W, and ~0.60 °C deviations between the actual physical system and the PEMFC-DT. The relative errors (%) of all parameters are shown in Figure 10e, which demonstrates the stability of the error trends across the tested timespan (DT-code literal outputs are given in the Supplementary Materials, Section S4). Overall, the PEMFC-DT verified excellent agreement with empirical data, with all absolute prediction errors remaining below 3.8%. Consistently low error margins confirm the high generalization capacity of the ANN-DT and its ability to capture both steady-state and dynamic behaviors (ANN training and validation loss is shown in the Supplementary Materials, Section S4). The PEMFC-DT reproduced the FC’s water-flooding prevention mechanisms, reverse-engineering its operational logic using feed-in data. This level of diagnostic insight linking physical preventive mechanisms to embedded control responses is rare in the literature and marks a significant advancement. The PEMFC-DT is validated as a robust surrogate for hardware-in-the-loop simulations, predictive maintenance frameworks, and adaptive operational tuning under varying load and environmental conditions. The DT is not purely a simulator but acts as a practical, application-ready tool capable of supporting control strategy validation, fault detection, and performance mapping in commercial PEMFCs deployed in H2 energy systems.

Figure 10.

Comparison of PEMFC experiments vs. DT prediction absolute values of (a) voltage (V), (b) current (A), (c) power (W), (d) outlet temperature (°C), and (e) relative error between experiments vs. DT values for all parameters.

3.6. Round-Trip Efficiency of the H2-Core System

Under practical operation, the AEMEL internally compresses H2 up to 29 bars, removing the need for external compression and eliminating compression efficiency losses. The AEMEL produced 0.512 Nm3 of H2 using 2.1 kWh of electrical input. The AEMEL exhibited an of ~68.6%. The PEMFC reconverted stored H2 into electricity with a measured of ~43.6%, based on an HHV input of 2.655 kWh per 0.06738 kg H2 and a net of 1.1576 kWh. The final stage involved charging a lithium-ion battery with a round-trip efficiency of 90%. The battery round-trip efficiency (90%) was extracted from the Pylontech US5000 manufacturer’s specification, which reports a typical charge–discharge efficiency of 90–95% for LFP cells under standard test conditions. Combining subsystems, the overall was ~27%, consistent with the expected range for distributed H2-based energy systems (see Figure 11). This result reflects a realistic energy return for H2-energy system autonomous operation and highlights the efficiency trade-offs in exchange for system flexibility and decoupled generation and load.

Figure 11.

H2-core system component efficiencies and round-trip efficiency.

4. Conclusions