Abstract

This article investigates the influence of faults in the phase current measurement channel on torque generation in permanent magnet synchronous motor (PMSM) drives. It is demonstrated that measurement errors, depending on their type and origin, significantly distort the actual electromagnetic torque as a function of the motor shaft angle. Since the current controller operates on incorrect values, indirect diagnostic methods are required. This study shows that analyzing the output signals of the current component controllers, particularly the torque regulator output and its phase relation to the electrical or mechanical angle, enables fault detection and classification. The waveform, frequency, and amplitude of these signals provide information about the fault’s nature, with offset errors having a more pronounced impact on torque across the entire load range than gain-related errors.

1. Introduction

Drives based on permanent magnet synchronous motors (PMSMs) are currently one of the core technologies in modern electric drive systems, particularly in low- and medium-power applications such as robotics, household appliances, industrial automation, and electric mobility. PMSMs offer high energy efficiency, high power density, and excellent dynamic performance. Their ability to provide precise torque and speed control makes them especially attractive in systems where fast response and high controllability are required.

Although high-power PMSM drives are increasingly used in traction, aerospace, and large industrial systems, the majority of commercially deployed PMSM-based drives still operate in the sub-kilowatt to several-kilowatt range, where compact size, low losses, and high control accuracy are critical design factors. In all of these applications, reliable acquisition of feedback signals—particularly stator phase currents and rotor position—is essential for achieving stable and fault-tolerant operation of the field-oriented control (FOC) algorithm. During operation, however, various types of faults may occur, including demagnetization of rotor permanent magnets, stator winding failures, power converter malfunctions, and measurement sensor faults such as speed encoders, DC-link voltage sensors, or phase current sensors [1,2,3,4,5].

One of the above-mentioned failures—stator current sensor malfunction—may lead to severe consequences, affecting the stability and reliability of the drive. Faulty operation of these sensors can also contribute to the degradation of other components, such as the motor. Common current sensor faults include measurement noise, signal loss, intermittent signal interruption, signal clipping, and variable gain [1]. These issues lead to disturbances in the generated torque due to the torque controller operating on inaccurate current feedback [6,7,8].

According to literature, current sensor fault detection methods are based on signal analysis, drive dynamic modeling, and artificial intelligence approaches [2,9,10,11,12]. Signal analysis-based methods include solutions employing Cri markers, as discussed in [1], and spectral analysis for identifying harmonic content of current signals [13]. Model-based approaches include methods relying on relationships between stator current–induced harmonics and winding short circuits [14], lookup tables [15], and recursive least squares algorithms for PMSM drive fault diagnosis [16]. Artificial intelligence approaches include detection methods using artificial neural networks [2,17].

In [18], a real-time online method for compensating current sensor offset errors was proposed. The estimation is performed using a motor model without the need for any additional hardware also similar in [19]. In [20], an adaptive observer-based approach for diagnostic purposes was presented, which, according to the authors, is robust to machine parameter uncertainties and load variations.

Another interesting approach was demonstrated in [12,21], where the authors employed a Sliding Mode Observer (SMO) for detecting and reconstructing accurate current values in PMSM control. In [22], a method for compensating current measurement sampling delay using a single current sensor was presented, while maintaining full motor control capability.

Additionally, several studies describe sensor fault detection techniques based on measured phase currents combined with motor models—such as the FDIE method—which enables isolation, detection, and estimation of both scaling gain and offset faults. This includes cases such as stuck sensors or broken-line faults, which may affect one or multiple current sensors either independently or simultaneously [11,23].

Some works also describe sensor fault detection methods based on measured phase currents combined with motor models, such as the FDIE method presented in [11].

A frequently used current sensor is the Hall-effect sensor, where the magnetic field of a conductor determines current magnitude. Typical failure causes include core corrosion, cracking or breaking of the core, thermal degradation of ferrite magnetic properties, or disturbances in magnetic field orientation induced by mechanical shocks. Improper sensor placement may also cause serious malfunctions, leading to increased low-frequency harmonics in torque ripple [5,15,24,25].

A widely applied method for motor current measurement in drive systems uses sensors placed on two of the three motor phases. In practice, the principle that the sum of currents in a three-phase system with isolated neutral equals zero is used, enabling reconstruction of the third phase current. This solution provides a cost–accuracy compromise by eliminating the need for a third sensor, reducing costs and simplifying the system. Despite its popularity, this method is highly sensitive to offset and gain errors, which may cause significant estimation errors of the unmeasured phase current. Therefore, analyzing these errors is important—identification and compensation can substantially improve motor control accuracy, which is crucial in high-precision applications such as servo drives and electric vehicles. Timely detection and classification of faults allow software-based compensation of measurement errors, ensuring correct current-control algorithm performance, e.g., in field-oriented control (FOC). Typically, the current sampling frequency is synchronized with the PWM switching frequency of the inverter [26]. Erroneous current measurements in current-controlled drive systems inevitably degrade control quality and, in some cases, may prevent proper drive operation. This paper presents and discusses the impact of typical current measurement path faults on the measured versus actual values of the current component and emphasizes the usefulness of monitoring the current controller’s output signal for as an effective indicator for fault detection, compared to direct observation of measured currents.

In contrast to the approaches reported in the literature, which mainly focus on model-based fault reconstruction, signal redundancy, or observer-based fault detection, the present study provides a quantitative analysis of the impact of current measurement path faults on the PMSM torque-producing current component (). The novelty of this work lies in evaluating the spectral and time-domain indicators—SNR, THD, and delay—derived from both measured () and actual () current signals, as well as from the controller output signal ().

This approach enables assessing how different fault scenarios, such as sensor gain errors or amplitude mismatches between current channels, affect the control signal behavior and system dynamics. Unlike previous studies that rely solely on direct current measurements or model estimations, this work demonstrates that the controller output signal () can serve as a reliable and sensitive indicator of current measurement faults, even under oscillatory conditions.

Thus, the proposed diagnostic perspective combines frequency-domain and control-response analysis to provide a new insight into sensor fault effects and detection in PMSM drives, offering a simple yet effective alternative to more computationally demanding model-based diagnostic methods.

2. Impact of Gain and Offset Errors on Motor Electromagnetic Torque

In practice, complete signal loss in current measurement channels is relatively rare. More frequently, degradation symptoms appear, such as gain variation or the presence of a DC component (offset). Effective diagnosis of such irregularities prevents the system from operating with a completely failed measurement channel, which could otherwise cause damage to the inverter, motor, or connected machinery. The most common initiating errors in measurement paths are offset and gain faults, which are the main subject of further discussion in this work.

2.1. Gain Error

Gain errors in current measurement paths primarily arise from inaccuracies in electronic components such as operational amplifiers, shunt resistors, analog-to-digital converters (ADC), and current sensors (e.g., current transformers or Hall-effect sensors). Their causes include component tolerances, temperature variations, aging, and electromagnetic interference [3,17,24,27]. Gain error manifests as a proportional distortion of the signal—the actual current may be consistently underestimated or overestimated across the entire measurement range. Such errors can have serious consequences: improper current regulation in the drive, increased motor heating, reduced efficiency, or even power device failure. In control systems requiring high precision, such as electric vehicles and industrial automation, gain errors can significantly degrade control quality, making their compensation or calibration an essential aspect of current measurement design.

For field-oriented control (FOC) of a PMSM, accurate measurement of phase currents is necessary. In practice, only two phases are measured, and the third is reconstructed as:

Calculation of the influence of gain error in phase A under indirect measurement of phase C current is presented below.

Actual phase currents:

Clarke transformation:

After substitutions, we obtain

Park Transformation:

for PMSM (without magnetic saturation, without saliency)

Torque distortion:

where

- —actual (physical) PMSM phase currents;

- —measured phase A current with gain error;

- —gain error in the phase A measurement channel (e.g., = 0.05 corresponds to +5%);

- —errors of the current components after Clarke transformation;

- —current components in the reference frame;

- —current components in the reference frame;

- —disturbance of the component directly affecting the torque;

- θ—rotor electrical angle (e.g., angle of the rotating -axis relative to the -axis);

- —constant flux linkage of the permanent magnets (along the -axis);

- —number of pole pairs of the motor;

- —error (disturbance) of the motor electromagnetic torque;

- —amplitude of the phase current;

- —electrical angular frequency ()

From the above considerations, it follows that

- The impact of disturbances depends on the combination of errors in phases A and B.

- The disturbance depends on the load.

- The torque disturbance caused by a measurement error in a single phase is a periodic function with a period of π, which results in oscillations at twice the electrical supply frequency of the motor.

In the case of simultaneous gain errors affecting both current-measurement channels, the resulting behavior differs from the single-fault scenario. If the gain deviation is identical and symmetric in both channels, the estimated currents preserve their mutual balance, and no oscillatory component appears in the electromagnetic torque. The effect of such a fault manifests only as a shift in the DC component of the reconstructed variables, which may remain undetected by oscillation-based diagnostic methods. Torque ripple becomes observable only when the gain errors are asymmetric, i.e., when the amplification factors of the two channels differ. In this case, the imbalance between the reconstructed phase currents introduces a periodic disturbance component, making the fault detectable.

2.2. Offset Error

Another source of errors in current measurement systems is the voltage offset at the output of the current measurement channel—a nonlinearity manifested as a nonzero output signal under zero input current conditions. The causes of this effect include, among others:

- Temperature drift.

Temperature drift of operational amplifiers commonly used in signal processing paths. Parameters such as input offset voltage and input bias current may vary significantly with temperature, leading to a shift in the signal’s zero point. Even a small drift, on the order of a few millivolts, can have a significant impact at low signal levels, especially in low-voltage systems.

- Asymmetry of amplification paths.

If the measurement channels are not perfectly matched in terms of gain, offset, or bandwidth, asymmetry occurs, leading to errors in the reconstruction of the third phase current and distortion of current vector estimation in the αβ or d-q reference frames. Moreover, propagation time differences between channels can disturb synchronous sampling, resulting in real-time measurement errors.

- Design and calibration errors.

Improperly selected components (e.g., amplifiers with excessive input offset voltage or low-quality passive elements) may introduce constant offset errors already at the design stage. In addition, incorrect system calibration—such as failing to account for offsets under operating conditions, omitting auto-zeroing after startup, or lacking software-based compensation—causes the control system to operate on erroneous data. As a result, this may lead to overloading of one stator winding, increased heating of power devices, mechanical vibrations, and even inverter instability.

Analogous to the case of gain error in the current measurement channel, the following section presents an analysis of its impact on the electromagnetic torque of the motor with indirect phase C current measurement.

The actual phase currents with indirect measurement of phase C current are:

Thus, let us apply the full form of the Clarke transformation matrix:

We substitute the vector with errors:

Park Transformation:

After substitution:

Torque distortion:

If the offset error affects only phase A (), the equation for the torque disturbance takes the form:

From the above considerations regarding the impact of offset:

- The effect of disturbances depends on the combination of errors in phases A and B.

- The disturbance does not depend on the load.

- It is a periodic function with a frequency matching the motor supply voltage.

The offset produces a pure torque ripple at the first harmonic, which is easier to filter or compensate. Scaling errors, on the other hand, can generate more complex harmonics, which are more difficult to detect and eliminate. Both types of disturbances have a significant impact on control quality, but their characteristics differ and can be additive.

3. Laboratory Measurements

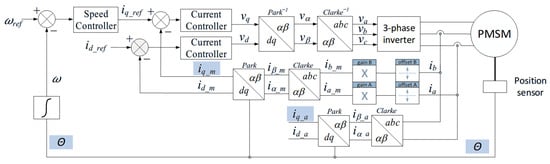

To perform measurements with predefined errors, a typical FOC system was used with modified software that allows for simultaneous computation for both the modified (error-injected) measurements and the correctly measured reference values. The schematic of such a system is shown in Figure 1. Values with the subscript “m” correspond to measurements obtained from the faulty current measurement system, while values with the subscript “a” are correctly measured. All control actions in the system are based on the erroneously measured values.

Figure 1.

Block diagram of the control system with an additional current measurement circuit for the test bench.

To enhance the practical applicability of the study, data that are standardly measured and available in PMSM control systems using field-oriented control (FOC) were used. Utilizing these results does not require any expansion of the measurement system with additional hardware components.

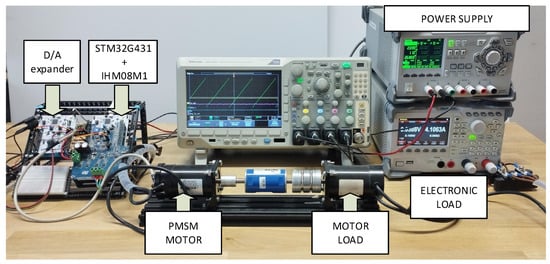

During measurements on the test bench (Figure 2), it was decided to record the following signals: the rotor mechanical position angle θ, the current component measured by the drive system, the output value generated by the controller for this component, and the actual component calculated from correctly measured motor phase currents. This setup allows for analysis of the impact of potential faults on the operation of the real drive system. The gain modification and offset injection in the measured current signals are implemented in software through an algorithm executed in the control unit. The magnitude of the injected faults can be adjusted in real time using the STM Studio (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland) interface, which allows parameter modification during system operation.

Figure 2.

Test Bench.

The key measurement and computation signals used in the analysis (, , θ) are transferred from the control system via high-speed digital-to-analog conversion using 12-bit DACs and recorded with Tektronix MDO3024 mixed-domain oscilloscope (Tektronix, Beaverton, OR, USA). Since the hardware platform provides only two DAC channels, an additional identical control module was used to output the remaining signals, allowing all four waveforms to be captured simultaneously. The data transmission rate between the modules was set to 2 Mbit/s to ensure that propagation delays do not introduce phase errors in the recorded signals.

The acquired data were processed and analyzed using the MATLAB/Simulink 2020b (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) environment.

The experiments were carried out on a permanent magnet synchronous motor (PMSM) with a rated power of 60 W and four pole pairs. The field-oriented control (FOC) algorithm was implemented on an ST Nucleo-G431RE development board together with the X-Nucleo-IHM08M1 power stage (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland). The mechanical load was applied using a second PMSM, coupled to the test motor through a rectifier and an electronic load. The remaining configuration parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Configuration of the control system and measurement subsystem in the experimental platform.

As the primary scenario, faults were assumed to occur in only one phase current measurement channel, under the assumption that simultaneous failure of two independent measurement systems is unlikely, and analysis of such a scenario would negatively affect the ability to draw generalized conclusions. The measure for detecting a fault and identifying its cause is the amplitude of oscillations in the measured quantities, as well as the nature of their variation as a function of the rotor electrical or mechanical angle. These are values that PMSM control systems continuously measure and that can be subjected to numerical analysis. This analysis method is more effective when the oscillatory signals exhibit higher variability, as the influence of measurement noise is then significantly minimized. Therefore, it is purposeful to select data that show high sensitivity to the occurrence of anomalies in the measurement channel.

3.1. Gain Error in the Current Measurement Channel

In the first step, measurements were conducted to assess the impact of gain variation in the phase current measurement channels for phases A and B, assuming reconstruction of the phase C current. These measurements were carried out for different gain values and various load torques of the drive system.

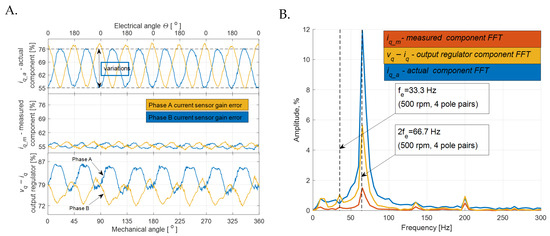

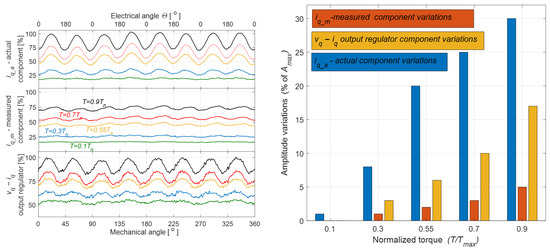

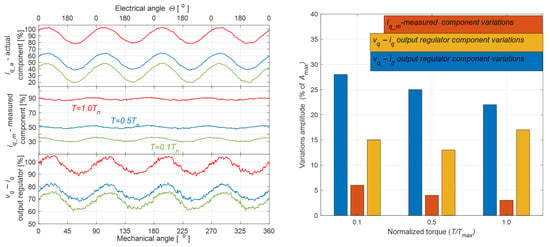

Measurements for the case of a current measurement system fault, involving a 30% reduction in gain relative to the nominal value in phases A and B, were performed at a motor load torque , and , where denotes the electrical frequency of the motor, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

(A) waveforms of actual and measured values expressed as percentages of rated values, and regulator output expressed as percentages of maximum value—yellow for phase A, blue for phase B. (B) The FFT is computed on the phase A AC component only, with the constant offset subtracted prior to spectral analysis.

Table 2 summarizes the values of the signal-quality indicators—SNR, THD, and time delay—computed for the individual waveforms corresponding to different reference-amplitude levels. All parameters were obtained directly from the recorded measurement data and processed using MATLAB/Simulink, which was employed for signal conditioning, frequency-domain analysis, and correlation-based delay estimation. This quantitative comparison of the measured current , the actual current , and the regulator output provides insight into how current-sensor gain errors affect the signals involved in the control loop. The results indicate that across all test conditions, the regulator output consistently exhibits superior signal quality compared to the measured current , particularly in terms of SNR and THD. This finding confirms that monitoring offers a more sensitive and robust diagnostic indicator for detecting oscillations induced by faults in the current-measurement path.

Table 2.

Frequency-Domain Performance Metrics of Measured and Actual q-Axis Currents.

Although the SNR of is only marginally higher (by approximately 0.8 dB) compared to the measured current , the improvement is consistent and, when combined with significantly better THD values and lower distortion around the fundamental frequency, confirms the superior diagnostic quality of .

Changing the gain of the current measurement channel introduces oscillations in the actual component, which is responsible for generating the motor electromagnetic torque. These oscillations arise because the current controller attempts to maintain the desired current value using an incorrect feedback signal. When the measurement system of the second current phase (phase B) is faulty, the torque oscillations exhibit a similar amplitude but an opposite phase compared to the fault in the phase A current measurement channel.

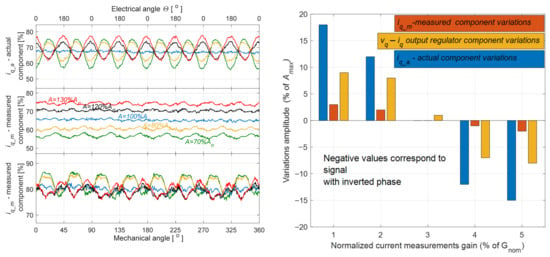

Figure 4 shows the current component as a function of the rotor mechanical angle θ for phase A current measurement channel gains varied from 70% to 130% of the nominal gain, at a constant load torque of . The measurement was performed for a drive system operating in open-loop speed control, with the rotor speed maintained at 0.5 .

Figure 4.

Waveforms of actual and measured values expressed as percentages of rated values, and regulator output expressed as percentages of maximum value for different amplification gains of A phase measurements. Red—130% of nominal gain, black—120%, blue—nominal amplitude, yellow—80%, green—70%.

Table 3 presents the SNR, THD, and time-delay values obtained for different reference-amplitude levels of the test signal. Across all operating points, the actual current maintains relatively stable SNR and THD values, except at the nominal amplitude, where both indicators deteriorate significantly. The measured current shows consistently lower signal quality, with reduced SNR, significantly higher THD, and noticeable time delays between 5 and 6.8 ms, confirming the strong influence of the gain error introduced in the measurement path. In contrast, the regulator output exhibits clearly superior diagnostic properties: its SNR and THD values remain consistently higher (i.e., better), and the delay is equal to zero for all amplitudes. These results indicate that monitoring provides a more robust and reliable basis for detecting oscillations than direct analysis of the measured current.

Table 3.

Frequency-domain performance metrics of the measured and actual q-axis currents (SNR [dB], THD [dB], and delay [ms]) for various reference-amplitude levels of the test signal.

Since the FOC method assumes current control at a setpoint, fluctuations in the signal measured by a faulty current measurement channel are corrected by the current controller and, in systems with high sampling frequency, may be difficult to capture using algorithms designed to detect measurement path faults.

It is clearly observed that the amplitude of oscillations increases with the magnitude of the gain error in the phase current measurement channel. At the same time, the amplitude of oscillations at the output of the current component controller is significantly higher, which allows analysis of its waveform to detect and quantify the severity of the measurement path fault. According to the mathematical analysis of the phenomena and the resulting Equation (1), the torque disturbance caused by a measurement error in a single phase is a periodic function with a period of π, corresponding to oscillations at twice the electrical frequency—this is clearly visible in the experimental measurements. This confirms the previous mathematical considerations. When the gain in the measurement path exceeds 100% of the nominal value, the sign of the measured value oscillations changes—this also provides important diagnostic information.

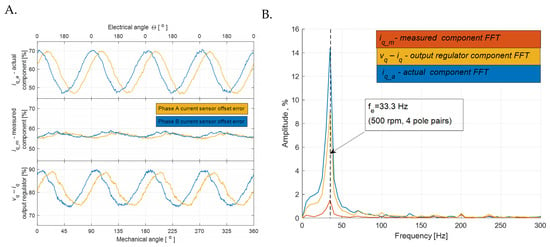

Measurements for the case of a current measurement system fault involving a 30% reduction in gain relative to the nominal value in phase A were performed for different motor load torques, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Waveforms of actual and measured values expressed as percentages of rated values, and regulator output expressed as percentages of maximum value for different motor loads: black—T = 0.9 Tn, red—T = 0.7 Tn, yellow—T = 0.55 Tn, blue—T = 0.3 Tn, green—T = 0.1 Tn.

A complementary set of results was obtained for several torque levels below the nominal value (Table 4). In this operating range, the actual current preserves good spectral quality for most torque settings, although both SNR and THD deteriorate noticeably at very low torque values, where the useful signal amplitude becomes comparable to the noise floor. The measured current again exhibits systematically lower SNR and significantly higher THD, together with torque-dependent variations in delay reaching up to 11 ms, which confirms the strong influence of sensor gain errors on current reconstruction at different load conditions. As in the previous case, the regulator output maintains the most stable characteristics, with zero delay and consistently superior SNR/THD values across the entire torque range. These results confirm that the diagnostic advantage of using is preserved not only across different current amplitudes, but also across varying load levels.

Table 4.

Frequency-domain performance metrics of measured and actual q-axis currents (SNR [dB], THD [dB], and delay [ms]) for a current-measurement fault scenario with a 30% gain reduction in phase A, evaluated at several sub-nominal torque levels.

From the measurements conducted with the current measurement channel gain reduced to 70% of the nominal value, it follows that the amplitude of oscillations in the measured values increases with the load of the drive system. At the same time, the amplitude of oscillations at the output of the current component controller is significantly higher, which allows analysis of its waveform to detect and quantify the severity of the current measurement path fault. According to the mathematical analysis of the phenomena and the resulting Equation (1), the torque disturbance caused by a measurement error in a single phase is a periodic function with a period of π, corresponding to oscillations at twice the electrical frequency —this is clearly visible in the experimental measurements. This confirms the previous mathematical considerations.

3.2. Offset Error in the Current Measurement Channel

In the second stage, measurements were carried out to assess the impact of offset variations in the phase current measurement channels for phase A and phase B, under the assumption that the current in phase C is reconstructed. The measurements were performed for different offset values and various load torque levels of the drive system.

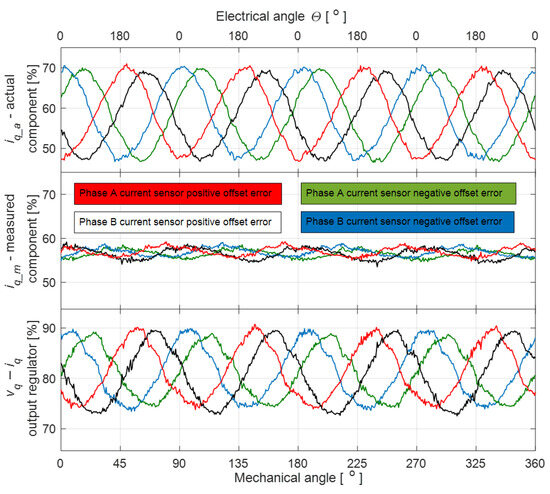

The test scenario simulating a failure of the current measurement circuit was conducted by introducing a +5% offset of the measurement range in phases A and B, with the motor load torque maintained at a constant value of , .

Table 5 summarizes the frequency-domain performance metrics obtained for the actual , measured , and regulator output signals. In this case, the oscillations occur at the electrical frequency , originating from an offset error introduced in one of the current sensors. The results confirm the same qualitative trend observed in previous analyses: the measured current exhibits the lowest signal quality, with significantly reduced SNR, markedly higher THD, and a substantial delay caused by the sensor error. In contrast, both the actual current and particularly the controller output maintain considerably better spectral characteristics, with again providing the most stable and delay-free diagnostic indicator.

Table 5.

Frequency-domain performance metrics of measured and actual q-axis currents (SNR [dB], THD [dB], and delay [ms]) for a +5% measurement-range offset in phase A.

The waveforms shown in Figure 6 for the measured values under modifications of the phase A and phase B measurement channels exhibit similar variability, but with a slight phase shift. This characteristic enables identification of the specific phase in which the fault occurred.

Figure 6.

(A) waveforms of actual and measured values expressed as percentages of rated values, and regulator output expressed as percentages of maximum value. (B) The FFT is computed on the AC component only, with the constant offset subtracted prior to spectral analysis.

- The test scenario simulating a failure of the current measurement circuit was conducted by introducing both −5% and +5% offsets in phases A and B, with the motor load torque maintained at a constant value of .

The waveforms shown in Figure 7, corresponding to four different fault scenarios of the current measurement offset, clearly indicate that the signals differ slightly in amplitude—resulting from the constant deviation of the offset from the nominal value—while exhibiting significant phase differences. This behavior enables both the diagnosis of the source and the estimation of the magnitude of the fault.

Figure 7.

Waveforms of actual and measured values expressed as percentages of rated values, and regulator output expressed as percentages of maximum value for 5% positive and negative offset error.

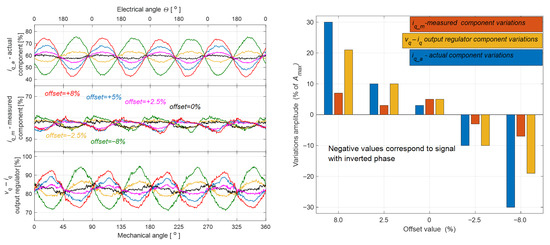

- The test scenario simulating a failure of the current measurement circuit was conducted by introducing offsets of varying magnitude in phase A, with the motor load torque maintained at approximately .

Table 6 presents the frequency-domain performance metrics—SNR [dB], THD [dB], and time delay [ms]—for the actual , measured , and regulator output values under various current-sensor offset conditions ranging from −8% to +8%. The results illustrate how increasing sensor offset affects the measured current quality, leading to higher THD, lower SNR, and significant delays.

Table 6.

Frequency-domain performance metrics of measured and actual q-axis currents (SNR [dB], THD [dB], and delay [ms]) under current-sensor offset conditions ranging from −8% to +8%.

The recorded waveforms shown in Figure 8, corresponding to five different fault scenarios of the current measurement offset, clearly demonstrate that the amplitude of variations is strongly dependent on the offset value in the analyzed channel. Furthermore, when the offset changes from negative to positive, the phase of the oscillations reverses.

Figure 8.

Waveforms of actual and measured values expressed as percentages of rated values, and regulator output expressed as percentages of maximum value for different phase A offset values. Black: 0%, red: +8%, yellow: −2.5%, blue: +5%, green: −8%, magenta: +2.5%.

- The test scenario simulating a failure of the current measurement circuit was conducted by introducing a +5% offset in phase A, with the motor load torque varied in the range from to .

Table 7 shows that across varying torque levels, the measured current exhibits higher THD and variable delays, while the regulator output consistently maintains stable SNR, lower THD, and zero delay, confirming its reliability for oscillation monitoring.

Table 7.

Frequency-domain performance metrics of measured and actual q-axis currents (SNR [dB], THD [dB], and delay [ms]) across varying torque levels, highlighting the increased THD and variable delays in and the stable performance of the regulator output .

As shown by the analysis of the measurement waveforms in Figure 9, the oscillation amplitude is almost independent of the load. This implies that fault detection can be performed even under no-load motor operation, which is consistent with the mathematical considerations leading to Equation (2). At the same time, the operation of the current controller makes diagnostics based on the variability of the waveform as a function of the angle θ significantly more difficult, since the amplitude of these oscillations is low and does not differ substantially from the values observed during the normal operation of a fault-free system.

Figure 9.

Waveforms of actual and measured values expressed as percentages of rated values, and regulator output expressed as percentages of maximum value for different motor loads: red—T = 1.0 Tn, blue—T = 0.5 Tn, green—T = 0.1 Tn.

4. Conclusions

The article demonstrates that the type of fault in the phase current measurement channel has a decisive impact on the actual drive torque as a function of the motor shaft position. Its actual value cannot be determined directly due to the fault in the current measurement channel, so diagnostics must be performed indirectly through the analysis of data available to the control system. Since the current controller operates on erroneous values and aims to regulate the motor supply parameters to maintain the torque as close as possible to the setpoint, the periodically varying actual torque is reflected in a similar pattern in the output signals of the current component controllers (Table 8).

Table 8.

Classification of sensor fault types and their impact on oscillation characteristics in PMSM drives. Gain errors result in oscillations at twice the electrical frequency (2·), while offset errors generate oscillations at the fundamental electrical frequency (1·).

The article shows that fault analysis of the measurement channel can be based on the analysis of the outputs of the current component controllers and their phase relative to the motor electrical or mechanical angle. The waveform and frequency of the controller output depend on the type of fault and its origin (the phase in which the incorrect reading occurred), while the amplitude of its oscillations depends on the magnitude of amplitude error and offset, and in the case of gain errors in the current measurement channel, also on the motor load torque. Using FFT analysis or more advanced machine learning methods allows detection of the fault, correct identification, and potentially compensation of the measurement error solely based on the electrical measurements performed by the drive system.

The analyses of SNR, THD, and time-delay across all test cases indicate that the measured current is significantly affected by sensor errors, resulting in lower signal quality and non-negligible delays. In contrast, the regulator output consistently provides higher SNR, lower THD, and zero delay, making it a reliable and robust indicator for detecting oscillations and monitoring the quality of the q-axis current in PMSM drives. These findings highlight the advantage of using over direct current measurements for diagnostic and control purposes.

Based on the mathematical considerations presented in the article and confirmed by experiments on a real system, it can be concluded that faults related to offset in the current measurement channel have a much stronger effect on the torque developed by the motor across the full load range than errors related to gain. This fact confirms the necessity of performing a specific calibration of the current measurement channel after inverter startup, which involves activating the lower transistors of the motor driver bridge and measuring the zero current value. The differences determined in this way between the readings in phases A and B provide the basis for determining the static offset error of the measurement channels and incorporating it into the calculation of values during normal motor operation.

The proposed analysis of the torque controller output eliminates the need for additional phase current measurement circuits, significantly simplifying the measurement setup and reducing investment costs to those associated with the development and implementation of appropriate detection algorithms. Fluctuations of the torque controller output when operating with a faulty measurement channel are significantly (even several times) larger than the fluctuations of the current component itself, which greatly enhances fault detection capabilities.

At the same time, it should be noted that the sudden occurrence of a fault triggers an immediate response from the drive system, which positively affects diagnostic capabilities but simultaneously has an immediate negative impact on the drive by causing torque oscillations. In extreme cases, these oscillations may damage the driven machine, drivetrain components, or, in the case of automotive applications, result in loss of traction. It is advisable to conduct similar studies concerning the motor flux controller, where oscillations of the controller output may have a different character and, in the case of gain errors in the measurement channel, may show a weaker dependence on load torque, which would positively affect detectability at low motor loads.

Another research direction is the development of a control method belonging to the family of vector-controlled fault-tolerant control (FTC) solutions for PMSM drives. The concept assumes analysis of measured current values only after prior verification of the measurement channel’s correctness. Based on this verification, the reference value database is updated, from which the spatial supply voltage vector is then generated. This approach allows for the maintenance of full functionality of vector control (FOC) while ensuring the drive system’s robustness against sudden faults in the current measurement channel.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.J.K. and B.D.; methodology, K.J.K.; software, J.G.; validation, K.J.K., B.D. and J.G.; formal analysis, K.J.K.; investigation, J.G.; resources, E.F.; data curation, E.F.; writing—original draft preparation, K.J.K.; writing—review and editing, K.J.K.; visualization, B.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Lublin University of Technology grant no. FD-20/EE-2/999.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jankowska, K.; Dybkowski, M. A Current Sensor Fault Tolerant Control Strategy for PMSM Drive Systems Based on Cri Markers. Energies 2021, 14, 3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbański, K.; Majchrzak, D. Faults detection in the PMSM drive using artificial neural networks. Przegląd Elektrotechniczny 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sirat, A.P.; Parkhideh, B. Current Sensor Integration Issues with Wide-Bandgap Power Converters. Sensors 2023, 23, 6481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Cheng, M.; Wang, W.; Hu, Y. Comprehensive Diagnosis and Tolerance Strategies for Electrical Faults and Sensor Faults in Dual Three-Phase PMSM Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 6669–6684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tretter, K. Understanding Amplifier Measurement Errors in Shunt-Based Current Sensing. Microchip Co., 4 February 2025. Available online: https://www.microchip.com/en-us/about/media-center/blog/2025/amplifier-measurement-errors-shunt-based-current-sensing (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Cheng, X.; Hu, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, R.; Yu, Q. Analysis and Compensation of Phase Current Measuring Error Caused by Sensing Resistor in PMSM Application. Sensors 2024, 24, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Wang, T.; Wu, L.; Li, H.; Meng, X.; Li, C. Analysis and Compensation of Current Measurement Errors in Machine Drive Systems—A Review. Energies 2025, 18, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Sha, W.; Zhu, C. Online correction method for phase current gain errors in permanent magnet synchronous motor sensorless control. J. Power Electron. 2024, 24, 1778–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liao, S.; Zou, B.; Liu, J. Mechanism-Based Fault Diagnosis Deep Learning Method for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. Sensors 2024, 24, 6349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, Z.Q.; Azar, Z.; Clark, R.; Wu, Z. Fault Detection of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines: An Overview. Energies 2024, 18, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddek, K.; Merabet, A.; Kesraoui, M.; Tanvir, A.A.; Beguenane, R. Signal-Based Sensor Fault Detection and Isolation for PMSG in Wind Energy Conversion Systems. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2017, 66, 2403–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Luo, Y.-P.; Zhang, C.-F.; He, J.; Huang, Y.-S. Current Sensor Fault Reconstruction for PMSM Drives. Sensors 2016, 16, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlaief, A.; Boussak, M.; Gossa, M. Open phase faults detection in PMSM drives based on current signature analysis. In Proceedings of the XIX International Conference on Electrical Machines (ICEM), Rome, Italy, 6–8 September 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, J.-R.R.; Rosero, J.A.; Espinosa, A.G.; Romeral, L. Detection Demagnetization Faults in Permanent-Magnet Synchronous Motorss Under Nostationary Conditions. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2009, 45, 2961–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, H.; Thakar, U.; Joshi, V.; Rathod, K.; Kurulkar, P. Hall sensor fault detection and fault tolerant control of PMSM drive system. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Industrial Instrumentation and Control (ICIC) Asia, Pune, India, 28–30 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.-G.; Kim, R.-Y.; Hyun, D.-S. Fault Diagnosis Using Recursive Least Square Algorithm for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Power Electronics—ECCE, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 30 May–3 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska, K.; Dybkowski, M. Experimental Analysis of the Current Sensor Fault Detection Mechanism Based on Neural Networks in the PMSM Drive System. Electronics 2023, 12, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, H.; Lee, K. Current measurement offset error compensation in vector-controlled SPMSM drive systems. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2022, 10, 2619–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.-K.; Kim, K.-S. Current and position sensor fault diagnosis algorithm for PMSM drives based on robust state observer. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 5227–5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jlassi, I.; Estima, J.O.; El Khil, S.K.; Bellaaj, N.M.; Cardoso, A.J.M. A robust observer-based method for IGBTs and current sensors fault diagnosis in voltage-source inverters of PMSM drives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2017, 53, 2894–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhou, H.; Wang, G.; Li, C.; Xu, D. Current Sensor Fault-Tolerant Control for Encoderless IPMSM Drives Based on Current Space Vector Error Reconstruction. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2020, 8, 3658–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yan, H.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Zou, J. Analysis and Compensation of Sampling-Delay Error in Single Current Sensor Method for PMSM Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 5918–5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaianese, C.; D’Arpino, M.; Monaco, M.D.; Noia, L.P.D. Isolation, Detection and Estimation of Current Sensors Faults in PMSM Drives Based on Current Signature Modeling. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2025, 40, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaianese, C.; D’Arpino, M.; Di Monaco, M.; Di Noia, L.P. Modelling and Detection of Phase Current Sensor Gain Faults in PMSM Drives. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 80106–80118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, K.; Dybkowski, M. Design and Analysis of Current Sensor Fault Detection Mechanisms for PMSM Drives Based on Neural Networks. Designs 2022, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicki, T.; Sikora, A.; Czerwinski, R.; Polok, D. Impact of PWM Control Frequency onto Efficiency of a 1 kW Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor (PMSM). Elektron. Ir Elektrotechnika 2016, 22, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khil, S.K.; Jlassi, I.; Cardoso, A.J.M.; Estima, J.O.; Mrabet-Bellaaj, N. Diagnosis of Open-Switch and Current Sensor Faults in PMSM Drives Through Stator Current Analysis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 55, 5925–5937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).