1. Introduction

The global energy transition towards low-carbon and sustainable energy systems has become a defining challenge of the 21st century. In the European Union (EU), this transition is being implemented through the European Green Deal and the Fit for 55 package, which together aim to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 and a 55% reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030 relative to 1990 levels [

1,

2]. Achieving these objectives requires a profound transformation of the residential energy sector, which accounts for a substantial share of final energy consumption and CO

2 emissions in most EU countries [

2,

3].

In Poland, as in many other Central and Eastern European Member States, the decarbonization of the building sector poses particular challenges. The national energy mix remains heavily reliant on fossil fuels, primarily coal and natural gas [

4], while the heating of single-family houses is still dominated by conventional systems. At the same time, growing awareness of climate policy, rising fuel prices, and technological progress in renewable energy systems—especially heat pumps and photovoltaic (PV) technologies—are stimulating a shift towards more sustainable residential energy solutions [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Nevertheless, despite the availability of such technologies, their economic feasibility remains a decisive factor for households, particularly when investment decisions are made without external financial support [

6,

9,

10,

11].

Economic analyses of renewable energy technologies (RETs) for residential buildings are frequently based on simplified indicators, such as annual operating cost or simple payback time, which often fail to reflect the full life-cycle dynamics of investment projects [

12,

13]. More advanced are studies related to the choice of personal vehicle [

14,

15]. In this context, the present study applies investment project evaluation methods that more accurately represent long-term financial performance. In particular, the analysis introduces the Present Value of Total Lifecycle Cost (PVTLC) indicator as a comprehensive measure of economic efficiency, suitable for non-commercial, small-scale investments [

16,

17,

18]. Moreover, a novel concept of Corrected Final Energy Consumption (CFEC) is proposed to enable a fair comparison between energy systems differing in source and efficiency [

19,

20,

21,

22].

The objective of this study is to perform a comparative economic evaluation of alternative heating systems for a newly constructed single-family house in Kraków, Poland. Four options are considered: a district heating system (DHS), a natural gas boiler, an air-to-water heat pump, and a heat pump integrated with a PV system. The analysis covers the 2022–2036 horizon and incorporates real market tariffs and data from the building’s Energy Performance Certificate (EPC). The proposed approach allows for the identification of the most economically viable and environmentally sound solution, as well as for assessing the impact of subsidies and energy price variations on the competitiveness of renewable technologies [

4,

6,

11,

23].

Using the EPC data eliminates the need for a robustness check, as these documents are based on a rigid, thoroughly tested methodology. Certainly, the annual volumes deviate from them, but in the long term, the EPC shall prevail. Using real 2–3-year consumption or climate data shall not be considered reliable for 15-year calculations, as such years very likely do not reflect average results in the long term.

By combining engineering and economic assessment methods, this research contributes to improving the accuracy of investment decision-making for residential energy systems. The results offer valuable insights for policymakers, investors, and energy planners, particularly in the context of designing support mechanisms that promote the cost-effective deployment of renewable energy in the residential sector. They differ in certain points from conclusions of similar studies, especially in reference to DHS [

3,

7,

24].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Building Under Analyses

The heat sources analyzed herein were to supply a medium-sized, two-floor, undetached house. The total area of temperature-controlled spaces (heated or cooled) amounts to 184.42 m2, of which 140.26 m2 constitutes the living area, while the garage and technical room account for 44.16 m2. During the heating season, the temperature in the garage and technical room is approximately 5 °C lower than in the living areas. The total building volume is 615.26 m3, of which 490.71 m3 comprises temperature-controlled space.

The house features a traditional design with a sloping roof, in which the external surface area is relatively small in proportion to the total area. The internal walls are constructed from 20 cm thick ceramic brick, plastered internally and externally insulated with an 18 cm layer of expanded polystyrene POROTHERM. All windows are triple-glazed and equipped with low thermal transmittance glazing. Ventilation is provided by a mechanical heat recovery unit, which utilizes the heat from extracted air to warm the incoming fresh air. The building structure contains no thermal bridges that could contribute to increased heat losses.

A thermal analysis of the building indicated high energy efficiency. According to the energy performance certificate (EPC) [

25], the annual demand for non-renewable primary energy is 45.95 kWh/(m

2·year), significantly below the regulatory threshold of 70 kWh/(m

2·year) required for new buildings under the applicable technical and construction regulations.

Air conditioning units were operated during the summer period. Given that their operation coincides with hot, sunny days, it can be reasonably assumed that they were primarily powered by energy produced by the PV system, which performs most efficiently under high solar irradiance. It can therefore be assumed, with a small margin of error, that the air conditioning units did not significantly increase electricity consumption from the grid. Their operation contributed mainly to increased self-consumption of energy generated by the residential PV system.

All systems within the house were fully powered by electricity. Neither connection to the district heating network nor to the gas pipelines was initially provided.

The building has been inhabited since the beginning of 2023. The heat source selection process took place at the turn of 2021/22, and installations were made in 2022. Based on recommendations from the architect, incentives from the municipality, and pro-environmental beliefs of the family, an electrically driven air-to-water heat pump was installed. It was supposed to be used for domestic hot water (DHW) production as well as for space heating (SH) via a low-temperature underfloor heating system. The average seasonal coefficient of performance (SCOP) of the heat pump is 2.60 in DHW mode and 3.00 in space heating mode. The heat pump is not used for cooling purposes; separate air conditioning units are installed for that function. Photovoltaic (PV) panels were included in the design and installed on a south-facing sloped section of the roof.

2.2. Purpose of Analyses

The building presented above, alongside the selection of the heat source originally made, offers an opportunity to test or develop instruments, allowing for the evaluation of the typically available options for supplying residential buildings with heat. Typically, undetached houses are located in smaller municipalities or villages with limited alternatives available. In most cases, the choice is limited to heat pumps and gas boilers supplied from tanks. In Poland, solar panels may only play an auxiliary role, while coal burners should not be installed in new buildings. The house in discussion is located in a big city (Kraków) in a quite densely populated area (famous district of Nowa Huta) with proximity to the DHS and gas networks [

7]. Therefore, these options were feasible and could be considered as real alternatives to the heat pumps installed. Certainly, the majority of residents in big cities live in apartment blocks, but there, the selection of heat suppliers is made initially by developers whose motivation is substantially different from the apartment owners’. They take into consideration future residents’ preferences, but there are also other determinants for their decisions. Consequently, a family-constructed and -owned house represents a “pure” case where investors are also users, have the freedom to select what they consider to represent the best source of heat, and possess the decision-making power to implement the preferred solution.

The purpose of the research was double-fold. Firstly, it was to evaluate, based on real tariffs for the years 2023–2025 and subsequent forecasts, the alternative sources available: the district heating system (DHS), the gas boiler supplied from the gas network (operated by PGNiG, PKN Orlen branch, Warsaw, Poland), and the air-to-water heat pump. The last option was analyzed in two scenarios: with and without PV installed. The second purpose was a universal one. Based on such a simple case, the authors intended to review methodologies commonly applied, to identify their deficiencies, and, finally, to identify or develop the most suitable one.

2.3. Methods Applied

Universally recognized metrics of investment efficiency are the Net Present Value (NPV) and Internal Rate of Return (IRR). It must be recognized, though, that they serve as a profitability assessment to provide precise quantification of potential financial benefits across the whole investment period [

23]. In the case of residential buildings, this tool ‘has to be adapted to the non-commercial character of the activities analyzed. The NPV concept assumes that for a certain, typically dominant, part of a project’s lifetime, net cash flow will be positive. Such an assumption cannot be justified in relation to projects concerning energy supply to residential buildings. Even if so-called prosumers are concerned, their supply to a grid is not intended to become part of their business, but an instrument for reduction in financial outlays. Therefore, the decision under analysis does not represent an investment case in a commercial sense for this term. Consequently, it should be subjected to evaluation using a more appropriate framework. Since a house owner makes decisions regarding the procurement of long-term services involving the acquisition of fixed assets and incurring the cost of operation and maintenance costs, as well as external energy supply, the concept of total cost of ownership has been developed to address such issues. It originates from business practices, where it has found numerous applications. Simultaneously, it has gained excessive scientific coverage. Recently, Panjaitan et al. [

12] presented a comprehensive literature review regarding the total cost of ownership as well as a technology and economic assessment. The authors identified more than 100 articles in top journals with a leading area of interest in energy and transportation. Nearly half of these papers include the customers’ perspective [

12]. Several of them refer to similar challenges [

14,

15].

The total cost of ownership (TCO) implies that only costs are considered, typically recalculated for a period (like a year or month) or for a unit. Such an approach disregards the time value of money and recognizes expenditure for fixed assets as depreciation. In the case of the selection of a heating supplier, this method leads to overestimating the attractiveness of options requiring high capital outlays. TCO is closely related to the lifecycle assessment (LCA), a commonly used method for examining all important parameters of a given solution, like a product, service, or system, throughout its entire lifecycle [

11,

16,

19,

20,

21,

26]. A thorough discussion of TCO deficiencies compensated by the LCA was presented by Garcez [

17]. In reference to environmental impact, LCA has been codified in the related ISO Standard 14044:2006, later amended [

27]. This methodology is also strongly promoted by the EU [

18]. It must be noted that much earlier, in 1980, the US government issued the manual for measuring the lifecycle costs of buildings, which, among other areas, included energy costs [

19]. The most advanced application of the LCA to heating systems for residential buildings was developed by Carbotech, (Basel, Switzerland) contracted by the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN): Economics and Innovation Division [

22]. The study covered nearly all existing solutions in Europe: natural gas and biomethane burners, heat pumps, district heating systems, photovoltaic thermal hybrid solar collector systems, electric heaters, cogeneration systems, and even wood burners. The only exception was light fuel oil burners covered by a separate study. They are topping the list of sources in Switzerland but are irrelevant in Poland; therefore, this omission has no impact on the paper presented herein. The Carbotech report contains detailed and credible data regarding technical and functional parameters of devices. It differs from this paper in terms of the objective of the research. Carbotech was assigned to evaluate the environmental impact of solutions under analysis, while this paper focuses on the economic costs for users. Therefore, the LCA approach must be supplemented by appropriate financial metrics.

The analytical framework of the research presented applies the PV methodology, with calculations systematically executed according to Formula (1):

where

Ct represents the cash flow at time

t (with

t = 0 denoting the initial investment); γ indicates the discount rate, representing the cost of capital;

n refers to the period under evaluation;

t designates the end of the year at which each cash flow materializes; and

C0 represents the initial capital investment.

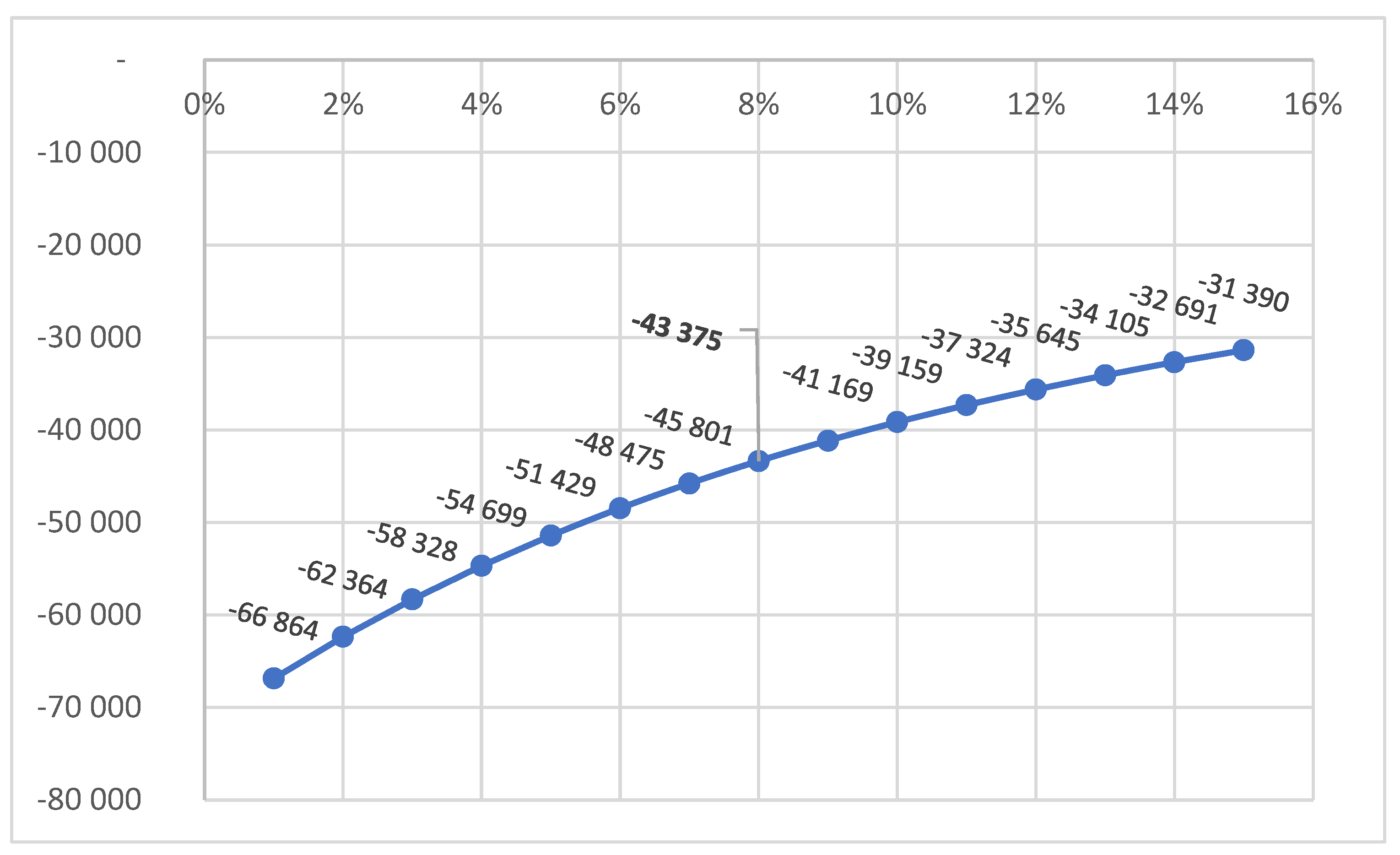

Two parameters that need to be established at the initial stage are the period under evaluation and the discount rate. When analyzing a business commercial project, its timeframe is established, taking into account various factors, like the forecasted lifetime of a product line, estimated technology, or turnaround cycle, as recommended by a machine manufacturer. Sometimes, if a project analysis is presented to capital providers, they determine their payback period, requiring that some margin be added to it. In the case of consumers, similar factors should be considered, but taking into account their different perspectives. Typically, they treat undertaking activities in the area considered as a problem to be faced and expect a selected solution to remain in place as long as possible. Construction or installation work carried out in a place of living always exposes its residents to a high level of discomfort. On the other hand, the period defined should allow us to compare the full lifecycle(s) of all solutions evaluated. One extreme is represented by a district heating system, which, from the customer perspective, typically requires relatively small, if any, initial investment and then can be considered perpetual. On the opposite side, there are individual gas boilers. Such complexity requires an arbitrary approach. Consequently, the period under analysis was defined as 15 years, commencing in 2022, when the house was constructed. As such, a long series of data would make tables unreadable; they present only the first 9 years (till 2030), while the remaining period is reflected in the residual value. Similar difficulties refer to setting the discount rate. Typically, analysts attempt to identify, either directly or indirectly, a shadow set of investment options with known rates of return and adjust them for the case under consideration. Another common technique refers to the so-called Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC), trying to establish a cost of financing for the given project. Such an approach cannot be mechanically applied to non-commercial undertakings. Customers finance investments in residential buildings either from their own savings or by using debt instruments. In the former case, an alternative is commonly represented by bank deposits and by private bank loans in the latter case. The problem is that, in terms of rates, these two options represent extremes among financial instruments. Bank deposits carry very low interest rates, sometimes even equal to 0%. On the other hand, consumer loans are usually among the highest-priced products, with the best offers starting at 10%. According to the authors, the best proxies are mortgages. In many cases, lenders are allowed to use this source of financing not only for a purchase but also for additional work, including the installation of heating sources.

The above considerations lead to the conclusion that the best-suited metric for a total lifecycle cost of ownership is the present value of cash outlays net of proceeds from the sale of energy to the grid for a period of 15 years, discounted applying an 8% nominal rate. The period and discount rate refer to the case under analyses. This measure may be called the present value of total lifecycle cost (PVTLC) [

5]. Applying so-defined metrics requires the construction of a dedicated financial model for each alternative solution. In the case under analysis, the list of options comprises the following four: gas boilers (supplied from the local gas network), district heating systems, and air pumps, either alone or combined with photovoltaic panels (PV). For each of them, a particular set of economic factors had to be considered, selecting appropriate items from the following list:

Capital expenditure is mainly composed of pumps, boilers, and PV panels.

Maintenance expenditures.

Energy carrier charges.

In addition, revenues for selling electricity surplus to the grid from PV were recognized. The model also presents capital costs in the form of an annuity, to allow for comparisons on a yearly basis.

2.4. Data Selection

Energy consumption in a building is determined by a complexity of factors related mainly to the following:

Only the first one may be considered quite stable. Weather conditions fluctuate substantially, with global warming being one of the factors. Finally, residents’ behavior has a multidimensional impact: the number of residents, their individual preferences regarding various areas influencing energy consumption, like the number of days away, preferred temperature, etc. This is why methodologies have been developed to standardize the latter two factors, allowing for the preparation of an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC), which is now obligatory for many properties in the EU and UK. These documents are prepared either by applying real data for building under continuous usage for the same purpose or standardized data when the former ones are either unavailable or unreliable (for example, due to modernization or changes in usage patterns). The building under analysis has obtained the relevant EPC based on standardized data; as at the date of the document’s preparation, it was new. Climate parameters were established for the Balice weather station, which serves the Kraków metropolitan area. The EPC also uses standardized energy consumption data.

Another important consideration refers to different classes of energy consumption within the building. The most commonly discussed is the so-called primary energy, which is equal to the energy content of fuels. This measure is easy to calculate when a fuel is converted into an energy carrier (typically hot water) in a building. This refers to gas- or coal-fired boilers. In case of a district heating system or electricity from the grid, one must know the fuel structure of the supplier; fortunately, such data are often easily available. In the case of PV, the convention is to assume zero primary energy consumption. The biggest problem refers to heat pumps. Here, electricity is required to force the flow of an absorption agent. The rule is that the lower the outside temperature, the greater the consumption of electricity required to obtain the same volume of heat. The Seasonal Coefficient of Performance provides information on the ratio of energy obtained as heat and consumed as electricity. The other class is final energy, which is measured at the building. It reflects a classical setup, where one or several sources (like a wood burner, gas boiler, or heat pump) transfer energy to internal central heating (CH) and domestic hot water (DHW) systems. Here, a problem of local generator efficiency must be mentioned. In numerous cases, the final energy is defined as delivered in fuel to a building. Such an approach makes comparisons quite difficult, as the conversion of energy in fuel into energy delivered to the installation also depends on the fuel itself. Typically, gas boilers are more efficient than coal and pellet burners. Only in the case of district heating (represented by a local exchanger at the residence) and electric heaters can this efficiency be assumed to be 100%. What meets the requirement of comparability is energy supplied to internal central heating (CH) and domestic hot water (DHW) systems after fuel conversion. Consequently, this paper uses the Corrected Final Energy Consumption (CFEC) as a harmonized measure for all alternative sources under consideration.

The major problem is caused by the treatment of heat pumps. In a significant group of calculations, including the EPC under consideration, the final energy is not the one supplied to the internal installation, but the volume of electricity consumed. Thus, the SCOP not only fully covers but artificially creates the surplus of usable energy over the final one. This issue can be addressed only if the amount of energy transferred from a heat pump to the buffer is measured, which is difficult to apply to small residential houses. If such metering is unavailable, the only solution is to create a proxy based on a standardized SCOP value.

The last class is the so-called usable energy—the volume finally transferred to an interior, after losses incurred in the internal installation. Comparing different sources in a credible way requires a coherent choice of the class of energy analyzed. Commonly, the final energy is selected for such a purpose, as this is the volume needed in a building, regardless of the source, and not influenced by the quality of the internal installation. However, differences in local energy generation also must be recognized. Therefore, this research applies the CFEC to identify the volume of energy supplied by alternative sources under consideration.

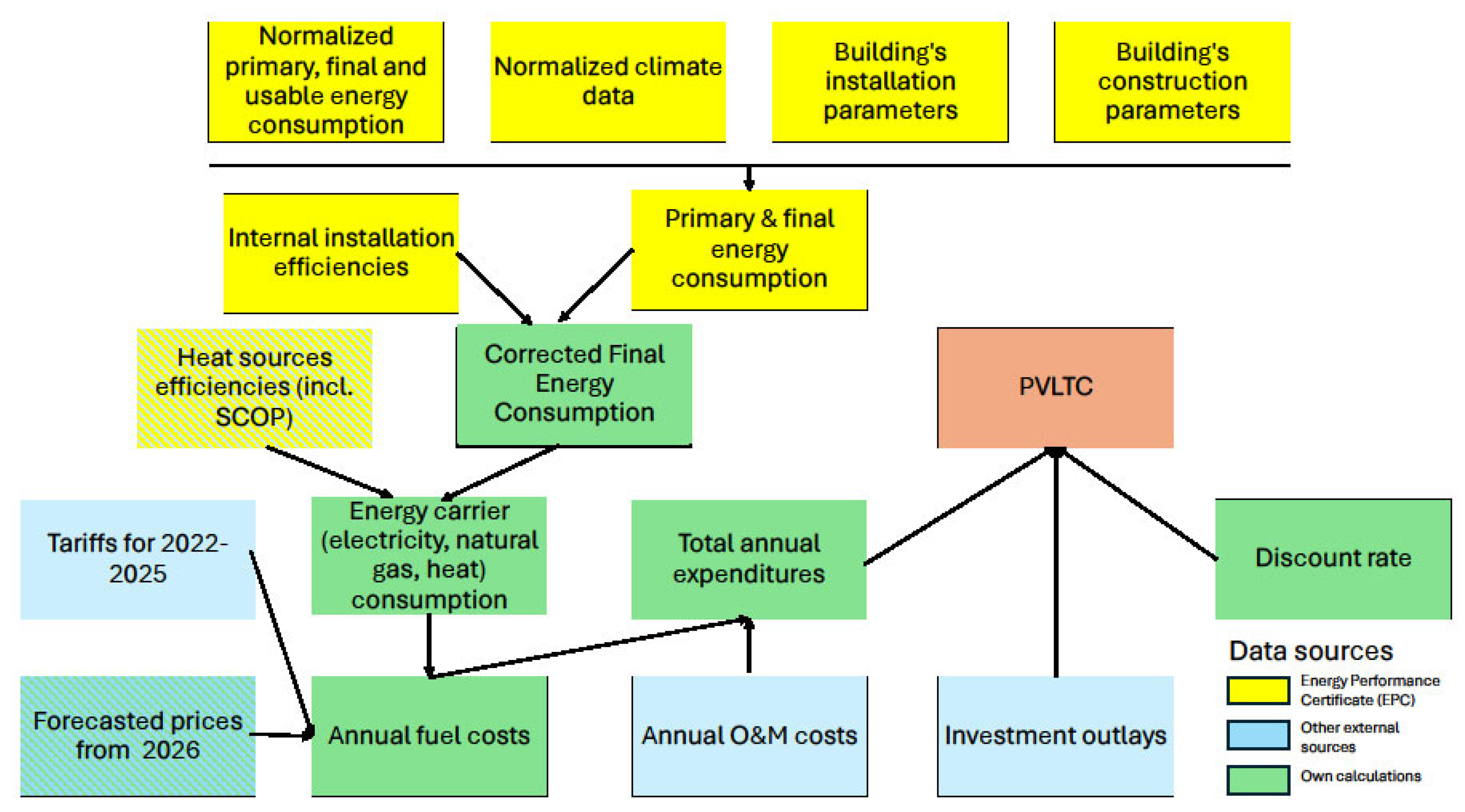

2.5. Diagram

The set of methods applied is presented in the diagram below, presenting sources of data and subsequent steps leading to calculating the PVTLC values (

Figure 1).

3. Results

As outlined above, the calculations presented below were performed based on the EPC. They stipulate that the annual, usable energy consumption equals 17.32 kWh per m

2 for the CH and 24.09 kWh per m

2 for the DHW purposes, translating into 3195 kWh and 4443 kWh for the whole building, summing up to 7638 kWh in total. The demand for final energy is lower because an air heat pump is included in calculations with an assumed SCOP of 2.60 (CH) and 3.0 (DHW). It amounts to 5231 kWh per year. In order to obtain a harmonized amount of energy, allowing for comparison with alternative sources, the final energy volume must have been corrected for air heat pump efficiency to calculate the CFEC (

Table 1).

In a standardized year, the house needs 11,756.46 kWh of energy to be delivered to the internal installation for both CH and DHW combined. Devices (e.g., internal pumps) are connected to an internal electricity network and supplied by the electricity supplier; therefore, their consumption falls out of the scope of the present analyses.

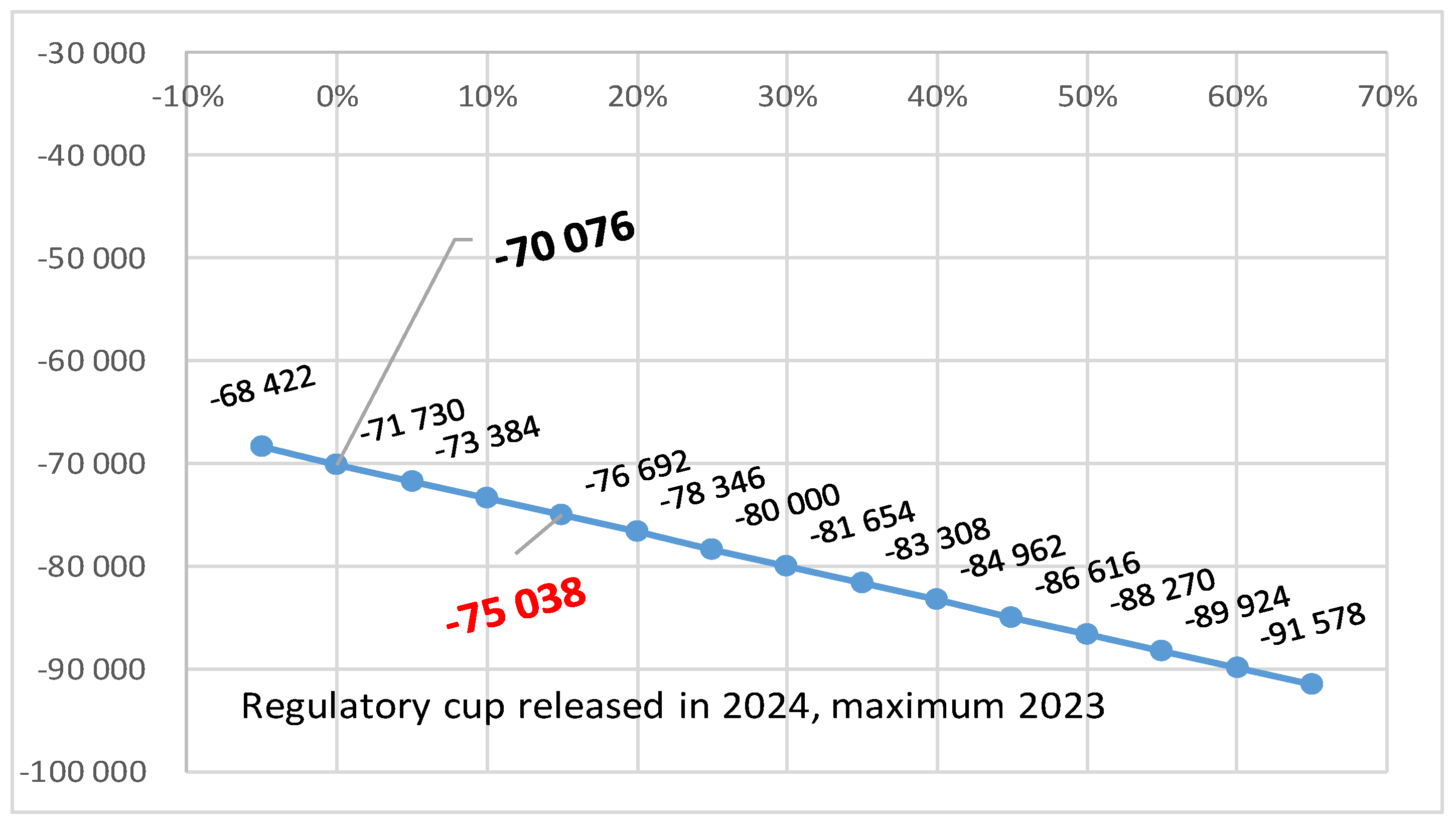

The first option considered was the District Heating System (DHS), which is present throughout Kraków. For communities and blocks, it is a compulsory source, but it can supply even individual households from the network or separate local sources dedicated to distant groups of customers. The big advantage of DHS results from the lack of any activities to be provided by the house owner [

4]. Basically, the customer needs to pay bills and enjoy services. All maintenance and supporting services are provided by the DHS and included in rates. The tariff consists of energy and distribution parts, and in both cases, charges are divided between fixed and variable components [

28]. The CFEC has been translated from kWh to GJs, as the latter measure is used by the DHS, applying the standard rate 1 GJ = 277.78 kWh. The power contracted results from energy consumption to the contracted power ratio at 7.5 GJ per kW. Connection outlays have been calculated, assuming a 20 m distance from the nearest node and a charge of 300 PLN/m. Prices are based on tariffs applicable for a given year within the 2022–2025 period. Since the outbreak of war in Ukraine, the Polish government has introduced a series of measures aiming at limiting increases in energy prices, including the implementation of maximum prices for residential buildings. They changed sometimes in the course of the year. In such cases, the one prevailing the longest was selected. Starting from 2026, the 2025 tariff was used. The authors decided not to use any forecasts, mainly because specific ones for DHS were not available. The construction of a necessary model must be a subject of separate research. Consequently, the PVTLC for using the DHS was calculated. Detailed calculations are given below (

Table 2).

The PVTLC slightly exceeded 60,000 PLN and was exclusively determined by the DHC fees. This is a very convenient situation, as customers’ risk is effectively limited to the volatility of the tariffs. The supplier effectively immunizes them from numerous risk sources, such as the following:

- (a)

Regulations;

- (b)

Breakdowns of devices;

- (c)

Supply of fuels.

Moreover, this solution occupies a limited space—certainly, it does not mean that these causes are fully eliminated, but they primarily affect the DHS operator, who, in turn, has much bigger capabilities to limit their impact.

Calculations for all other than DHS solutions are more complicated, as heat is effectively produced by a house owner who acquires necessary devices and fuel or, like in the case of solar energy, even produces it. Moreover, individuals typically do not carry any accounting allowing for proper registration of all costs. Easily available is information on fuel purchased when it is used exclusively for heating (like in the case of gas), but electricity represents a problem as it is not measured on the level of individual devices; consequently, its consumption includes lighting, home appliances, etc.

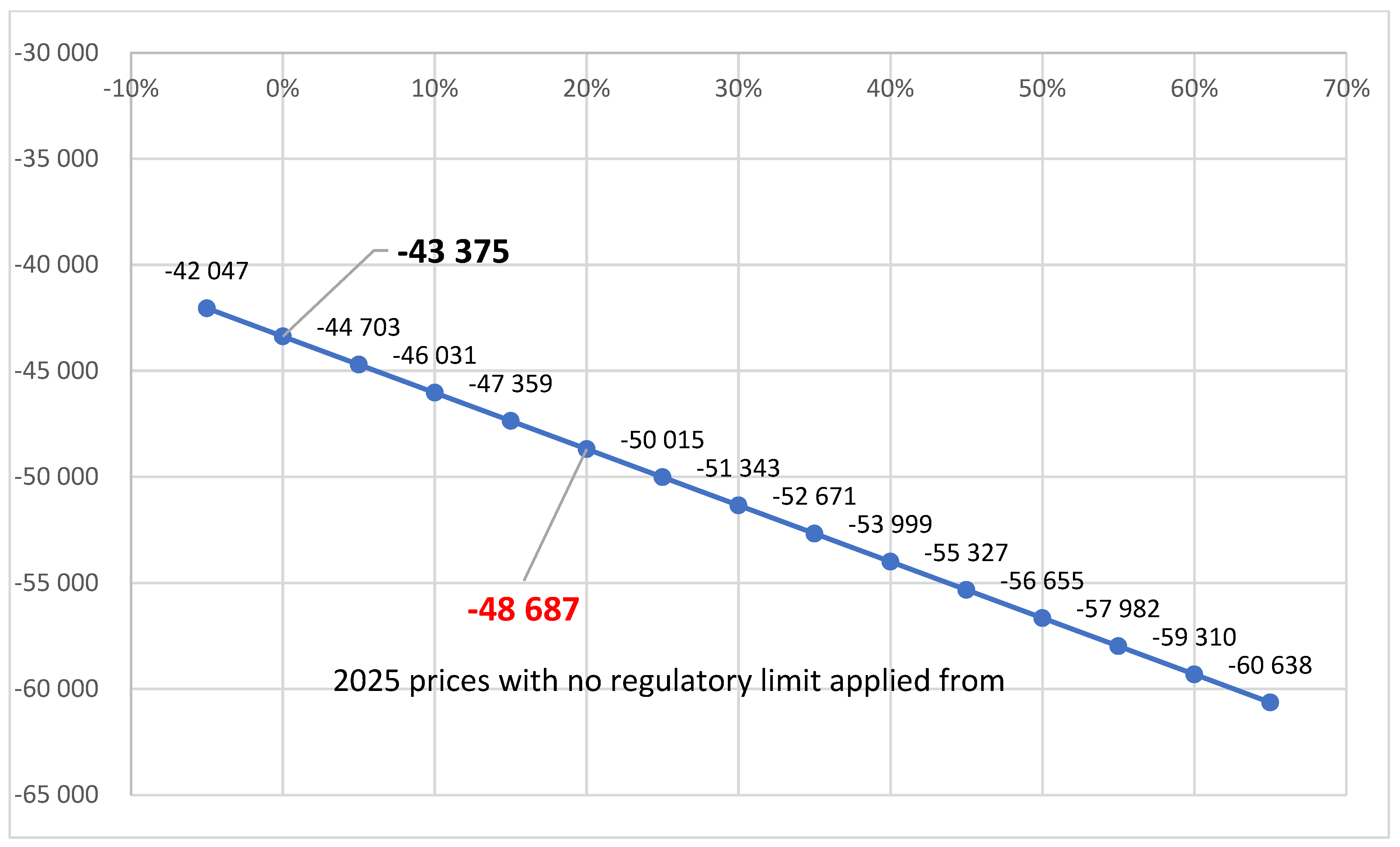

The second option considered was the installation of our own, dedicated gas boiler. The cost was estimated at 25,000 PLN based on the prevailing prices of devices and services. The boiler was set to have 25 kW nominal power. The gas network is also very well developed. Connection outlays have been included in the installation costs. Prices are, as in the DHS case, based on tariffs applicable for a given year within the 2022–2025 period [

29]. Since they were affected similarly by the outbreak of war in Ukraine, the tariffs prevailing the longest were selected for each year. Starting from 2026, the 2025 tariff was used. The authors again decided not to use any forecasts, since there are numerous forecasts available, but the span of values is so great that a choice here would determine the final results. By picking lower bounds, the authors would put the gas option as clearly being the cheapest one, while in the opposite case, this would be an outrageously expensive choice. Consequently, the PVTLC for the gas boiler option was computed. Detailed calculations have been given below (

Table 3).

Analyses of the individual gas boiler require us to make assumptions regarding the boiler efficiency and maintenance costs. These values are strongly dependent on a specific device (manufacturer and model). Efficiency poses a challenge. There are two commonly used parameters of natural gas energy: calorific value and heat of combustion. Both describe the amount of heat released during the combustion of gas, but they differ in taking into account the heat of condensation of water vapor. The heat of combustion is the total amount of heat that is generated during combustion, including the heat released when water vapor condenses in the flue gas. The calorific value, on the other hand, is the amount of heat without the heat of condensation. Applying the latter one leads to obtaining efficiencies above 100% [

5]. Since the Polish gas tariffs use the former one, the related efficiency was defined accordingly and set to 91%. Maintenance costs were set linearly based on data from manufacturers. They include the electricity consumption of the device and exclude the warranty period. In the case of non-commercial use of equipment, such costs are very much dependent on a specific user. Numerous people service their boilers only in case of breakdowns, for various reasons, not limited to negligence and affordability. One of the authors has not serviced his device for two years due to a limited availability of specialists.

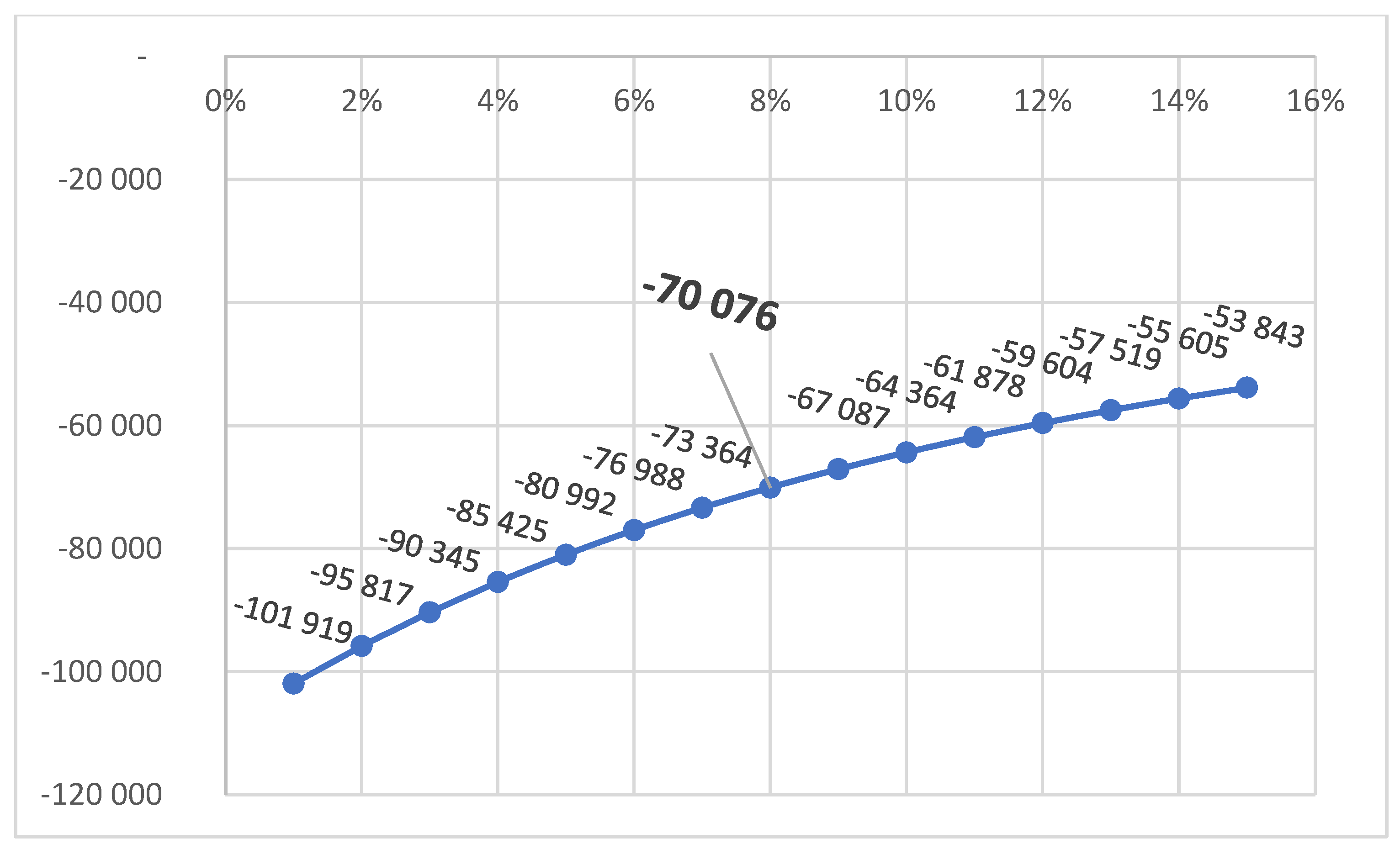

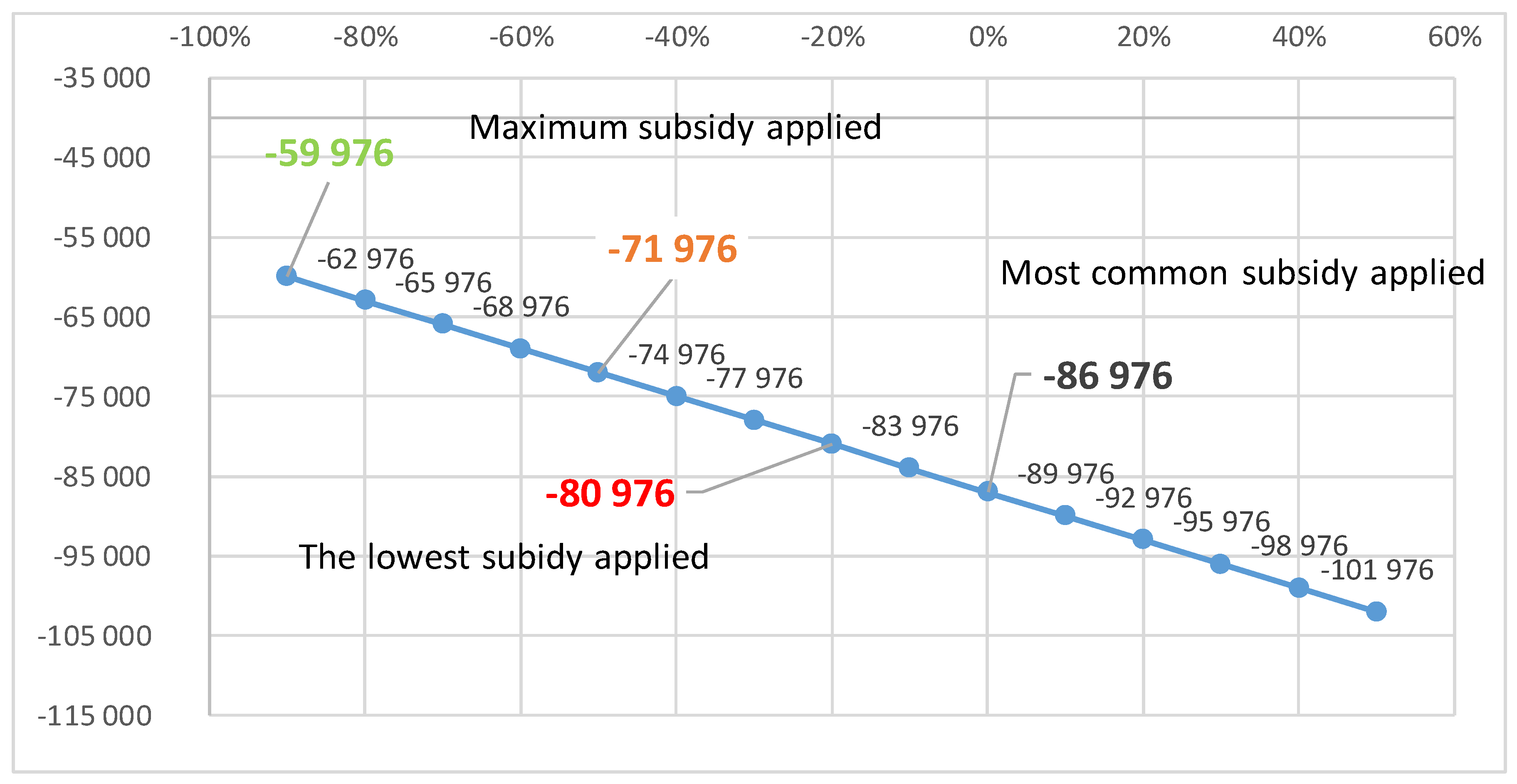

The third option was to install an air pump supplied with electricity from the grid. The cost was estimated at 30,000 PLN based on the then-prevailing prices of devices and services. It requires a supply of electricity, which is available anyway, but requires an upgrade included in the installation costs. Consistent with the first option, prices are based on tariffs applicable for a given year within the 2023–2025 period [

30], and for the remaining future years, the 2025 rates were applied. One specific issue that had to be addressed was the construction of the price cap. In the previous cases, privileged prices applied to the whole consumption. In the case of electricity, a cap of 1500 kWh was introduced, above which residents were supposed to pay market prices. This limit is quite low. The authors have access to data from an apartment with a gas boiler, gas cooker, and no air-conditioning inhabited by four people (family), so nearly no electricity is used for heating purposes, and the average yearly consumption there approaches 2000 kWh. Therefore, it is justified to assume that air pumps consume energy above the cap. However, the cap was eliminated in late 2024, so for 2025, the preferential tariffs are applied. The PVTLC for the air pump with related calculations is given below (

Table 4).

Again, assumptions were needed regarding the air-pump efficiency and maintenance costs. These values are not only, like in the previous case of gas boiler, dependent on a specific device (manufacturer and model) but also on outside temperatures. The EPC applied data from the nearest station located at Balice, which is 10 km away from the house under analysis and outside the core Kraków residential areas. Based on measurements from there, the SCOP of 2.60 for CH and 3.0 for DHW was applied. Maintenance costs were assumed based on manufacturers’ recommendations, although similar remarks regarding individual attitude as in the gas boiler case apply here too.

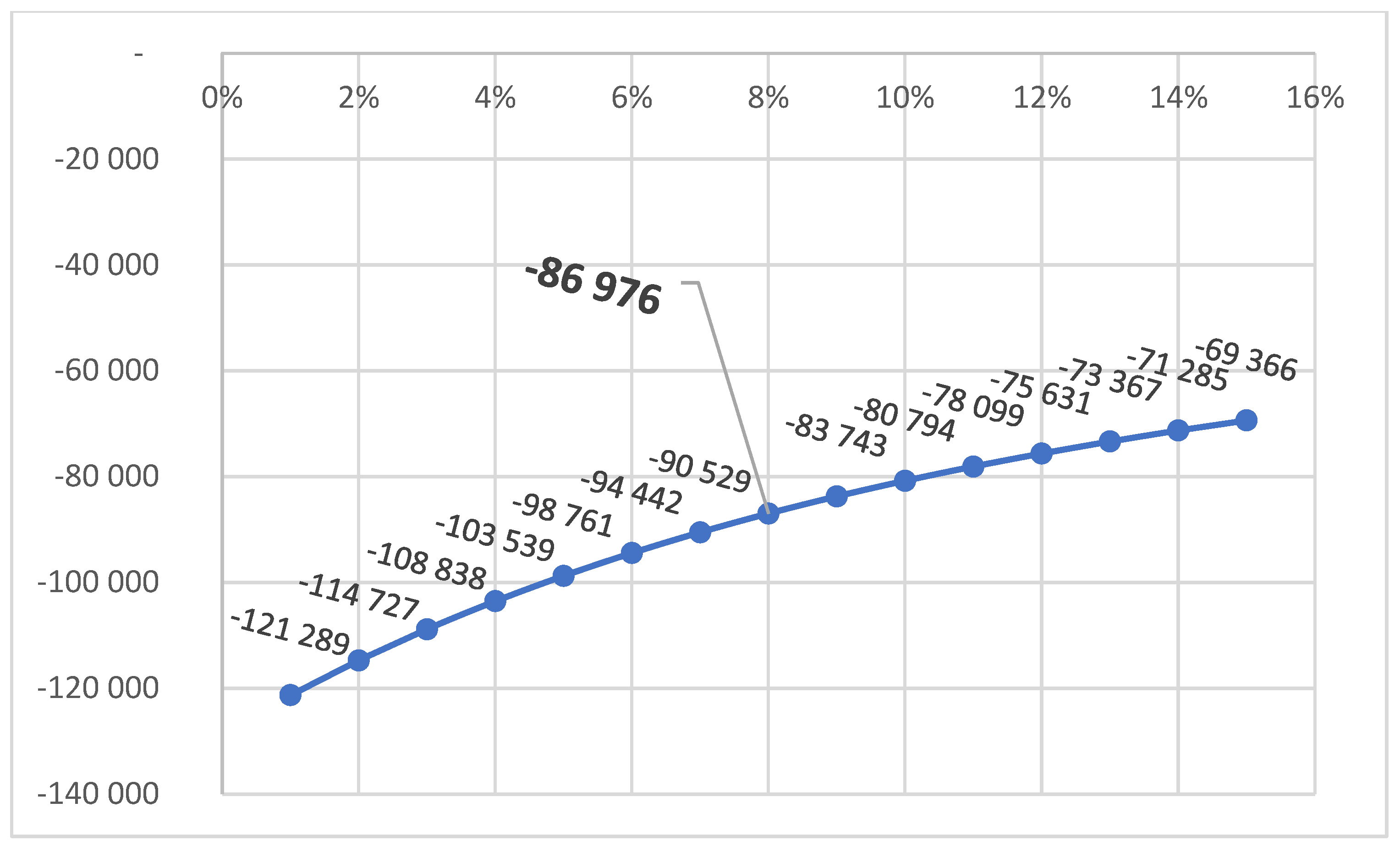

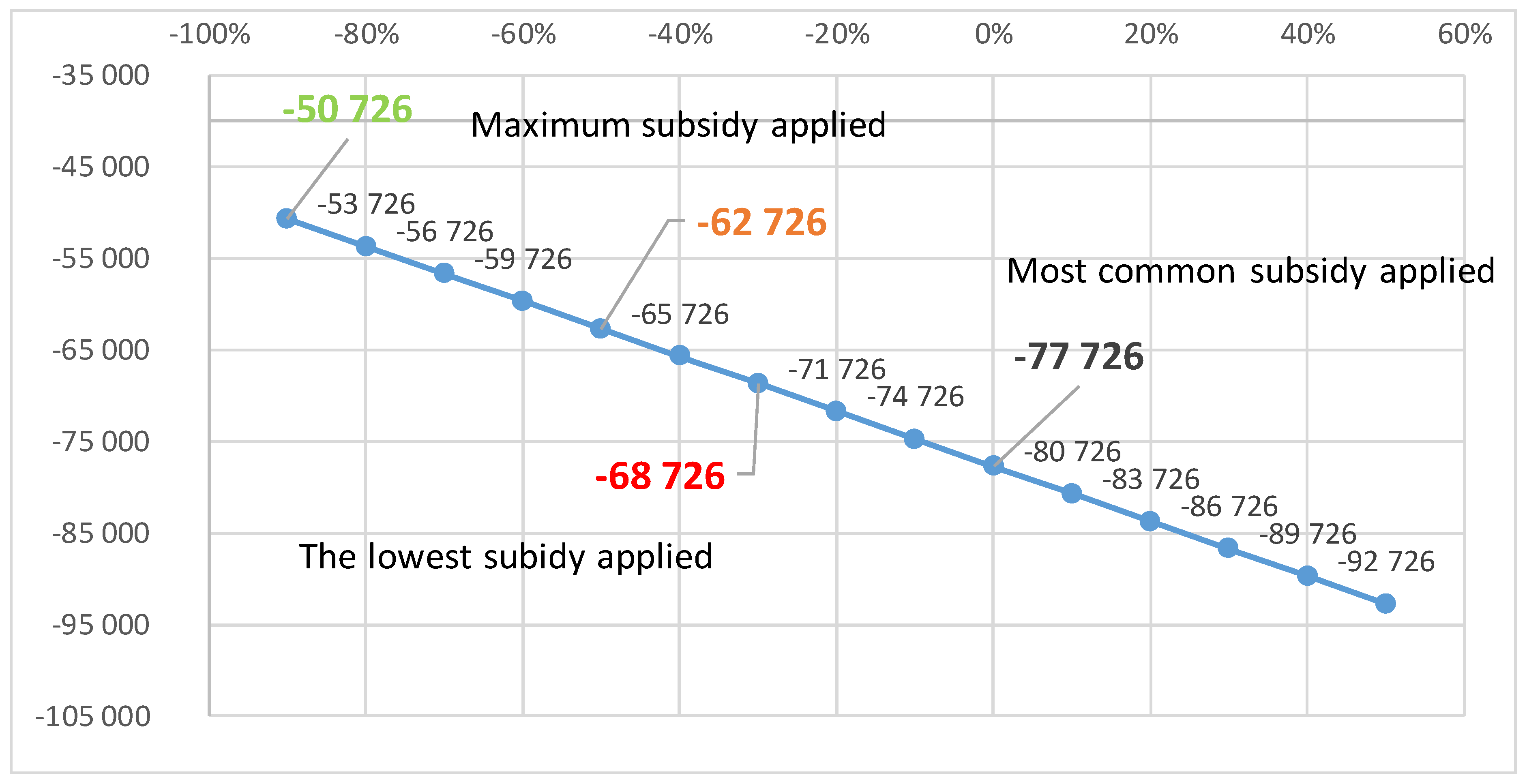

The last option considered combines an air pump with a solar installation. The house enjoyed very favorable terms of solar energy supply to the grid. The net balance method has been used, which stipulates that the prosumer pays for the energy delivered from the grid minus the volume supplied to the grid. These terms are not available anymore; thus, the present investments enjoy much worse conditions than the ones under consideration. The PVTLC for the air pump, combined with PV panels and related calculations, is given below (

Table 5).

This last option varies from the air pump alone in two areas. Firstly, the purchase of electricity from the grid was reduced by solar output. Secondly, the investment outlays for PV panel installation were added, but no additional maintenance expenses were recognized, as, in residential houses, they are considered to require no additional activities.

The above-mentioned four options represent the full list of really available solutions. Utilization of the ground-feat pumps was impossible given the plot area and shape. Wind and geothermal energy (as well as nuclear energy) could be provided only via DHS and thus could not be included in the study.

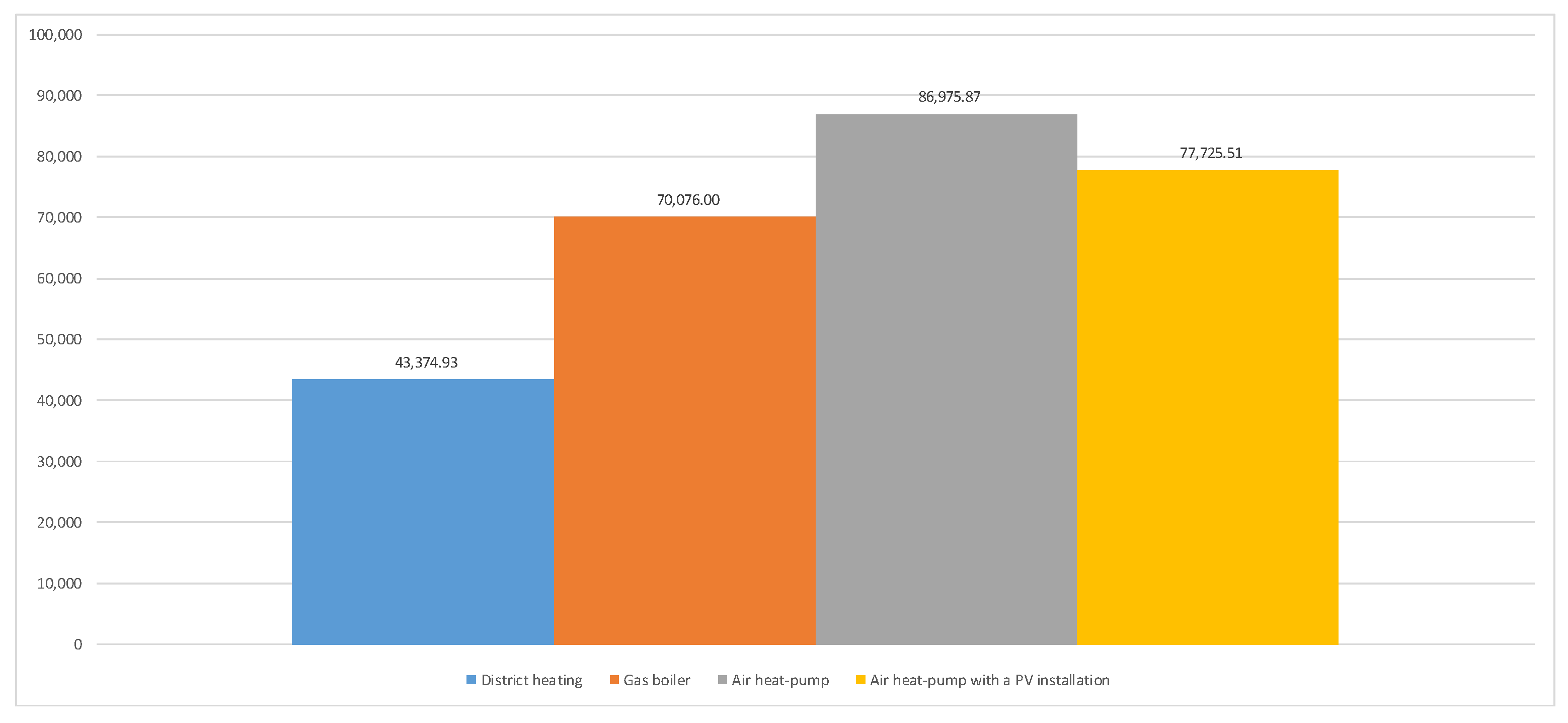

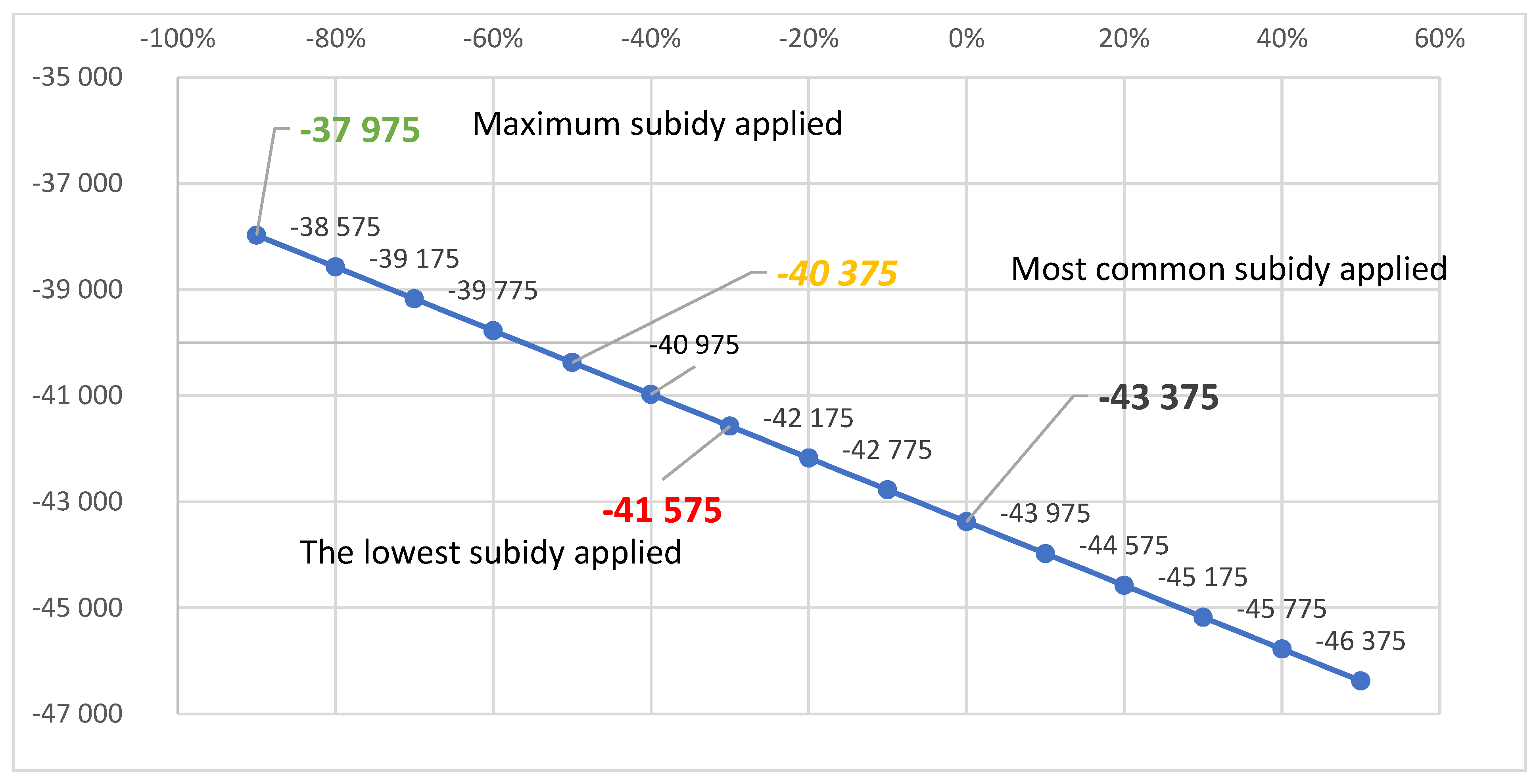

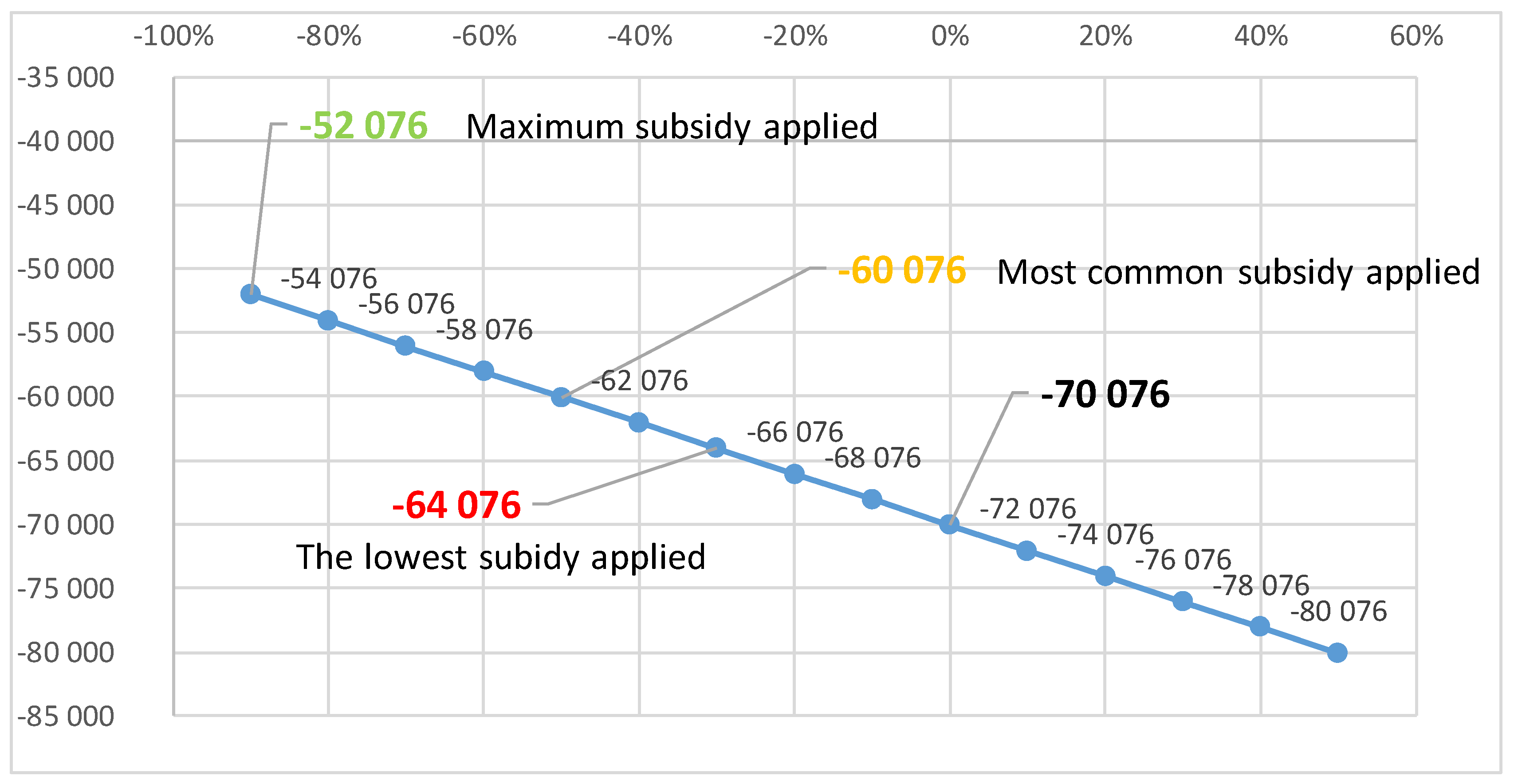

Below (

Figure 2), the alternative sources are ranked according to the PVTLC, where the lowest value implies the best solution. The DHS came as the most favorable option, while the air-to-water heat pump without PV was the most expensive one. Even if supported by PV panels, this environmentally favored option was more expensive than the fossil-fuel-based ones.

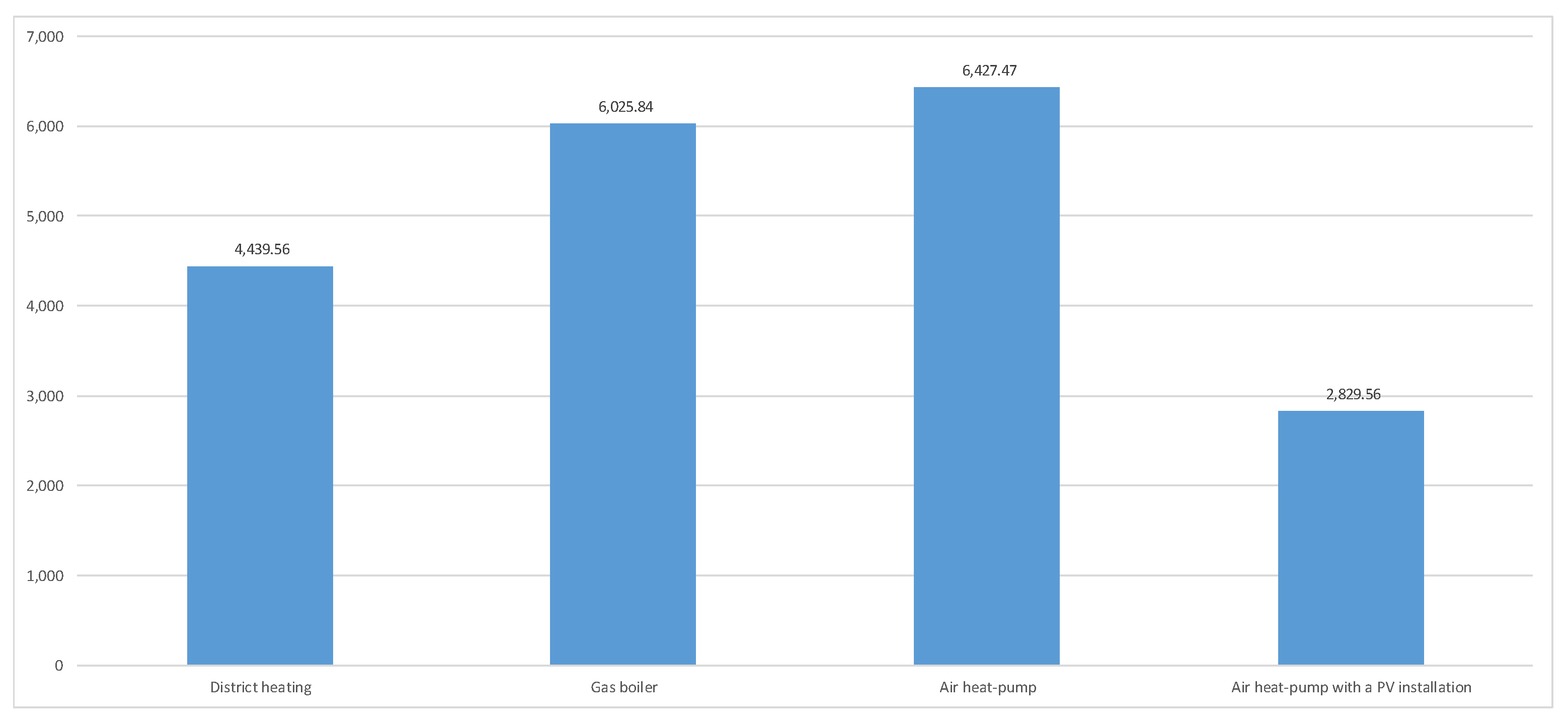

It is interesting to compare the PVTLC results to those based on annual expenses (

Figure 3). These results are substantially different, as the air heat pump combined with the PV installation comes clearly first. The biggest initial investment results in low operational expenses. The problem is that from a financial point of view, they are not low enough.

5. Conclusions

In the northern hemisphere, even in the era of global warming, the supply of heat remains equally vital for survival and even for food. It represents a very basic need every human demonstrates. From the perspective of selecting a source of supply, heat and food differ substantially. Alimentary needs can be satisfied by a variety of products (and services) available from a wide range of providers. Moreover, these products are consumed quickly and can be restocked from other sources with no sunk costs. Heating can typically be provided by a limited number of methods. Each of them includes the use of infrastructure operated by an exclusive supplier. The case of DHS is extreme. All services can be obtained only from the local operator of such a system, but when other solutions are scrutinized, the customer’s freedom is also limited. First of all, gas and electricity distribution services are also monopolized. Purchase of fuel and energy is now liberalized, but the number of operators capable of supplying a small residential house is very small. Moreover, in the case of electricity tariffs, it is becoming more and more complicated. For individuals, it turns out to be very difficult to assess offers, as it requires making many assumptions. Also, a choice of devices to be installed poses a challenge. Producers, in trying to sell their products, are providing skewed information. The best example of such practices is offering gas boilers with efficiency surpassing 100%, impressing buyers with advancements in modern technology. Technically speaking, they are correct, but in the context of the purpose, customers are misled. Such high efficiency refers to the calorific value, which is not used by gas providers. If the heat of combustion is correctly applied, the efficiency goes down below 100%. For a customer accustomed to cubic meters as the primary measure of gas consumption (by the way, measurement equipment presents cubic meters, not heat units), this difference represents 10–20% of the total volume. In the case of air pumps, the values of SCOP can be “adjusted” by a seller who does not carry any responsibility for real values, which in turn are very difficult to measure and, in practice, are not measured at all.

The paper argues that the most proper objective measure to select the optimal source of heating is the Present Value of Total Lifetime Cost of available options. Other, “simplified” metrics lead to suboptimal decisions. Applying this concept creates many difficulties. The first reason lies in the complexity of factors to be identified and valued. As it poses a significant challenge to professionals, it is clear that, for an individual, it creates unbeatable obstacles. The second results from future uncertainty. This factor has always been present, but recent developments, especially in the EU, regarding climate-related regulations add to it significantly. Up to the year 2000, all energy prices had been circulating in close connection to crude oil, roughly maintaining relations between various energy carriers. The introduction of emission charges, imposing ambitious thermal insulation requirements and effective elimination, at least in big cities, certain traditional fuels like wood and unprocessed coal changed the situation dramatically. These are political decisions (even if well-grounded scientifically) and might be recalled or changed much sooner than the 15-year lifetime analyzed. Also, in this area, the uncertainty of weather conditions plays an important role. The most objective data comes from EPC, but they are normalized and always differ from the real situation. These variations have an impact on the ranking of solutions. Typically, higher temperatures favor air pumps by driving the SCOP up, while lower ones support the DHS, as this option features the highest percentage of fixed charges. This risk will be borne by individuals. The third one relates to individual characteristics of a house owner/user. It encompasses numerous factors like preferred temperature of both interior and hot water, share of time spent at home, environmental sensitivity, etc. People going out for long periods may favor more elastic options, allowing them to heat up just before arrival, compared to those spending most of the time at home (working in a home office, for example). Taking all these factors into account, average individuals are not in a position to knowledgeably evaluate the options provided by suppliers. Exposed to “advanced models”, “innovative solutions”, “irresistible discounts/subsidies”, and other persuasive arguments, in the end, they align with the most communicative sales representative.

The other source of complexity and risk is the growing scope of governmental (and EU) interventions. The first instrument shaping the relative attractiveness of different sources is the introduction and expansion of carbon emission charges. It is expected that EU regulations will eliminate the use of natural gas. District heating systems, which are conceptually based on a model where heat is produced in one or very few sources and widely distributed throughout densely populated areas, are under pressure to encompass more renewables, which, by definition, are decentralized. Such a change must come at a cost, and customers will be the final source of funds.

The last source of complexity lies in the different structures of cash outflows, especially regarding initial investment. Many consultants and researchers focus on annual operating costs. Such an approach favors sources with high initial investments. One example comes from the webpage of air pump distributors. It claims that

servicing a house with an area of 200 square meters (so, very similar to the one analyzed in this paper)

can cost about PLN 4 thousand (gas) or PLN 7 thousand (electricity), while the cost of heating a building with a heat pump will be about PLN 2 thousand a year (including DHW). Only later does it admit that it comes at the expense of PLN 30–40 thousand (

https://ergos.pl/pompa-ciepla-czy-naprawde-jest-tak-oplacalna-rodzaje (accessed on 7 November 2025)). The solution extremely negatively affected by focusing on annual expenses is DHS, as capital outlays are included in periodic bills, and all expenses are disclosed on them. On the opposite side, there is an air-pump in which electricity consumed by this device is included in the total electricity bill. If PV panels are installed, such a bill is reduced by the solar energy produced. Calculating how much was truly spent on supplying the air pump itself requires either the installation of specialized monitoring systems or the construction of quite complicated models. Although many modern devices are sold with built-in energy management systems that allow for monitoring the system’s performance and electricity consumption, they are not comprehensive. In most cases, they measure only the electricity used by auxiliary heaters but not by the pump itself.

The analyses presented above demonstrate the complexity of factors determining optimal solutions for heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning. To construct a complete model supporting customers’ decisions, there is a need to encompass socio-psychological factors. Merging financial measures with personal preferences should be considered as the most demanding challenge for future research in the area under discussion.