A Family of Fundamental Positive Sequence Detectors Based on Repetitive Schemes

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Derivation of RPF structures for the all-, odd-, and the harmonics, where the all- and odd- harmonics RPF structures become simple feedforward paths.

- Tuning rules for every RPF used in the FPS detectors.

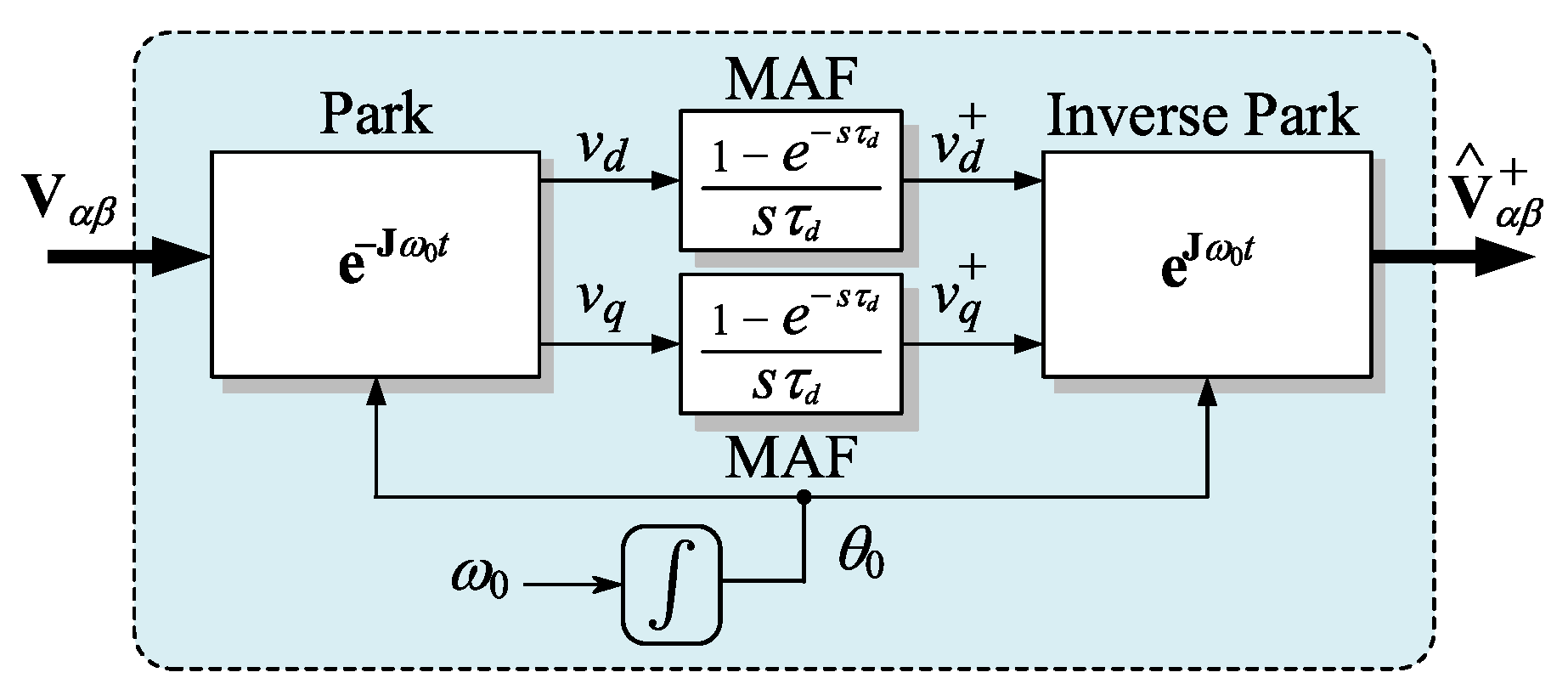

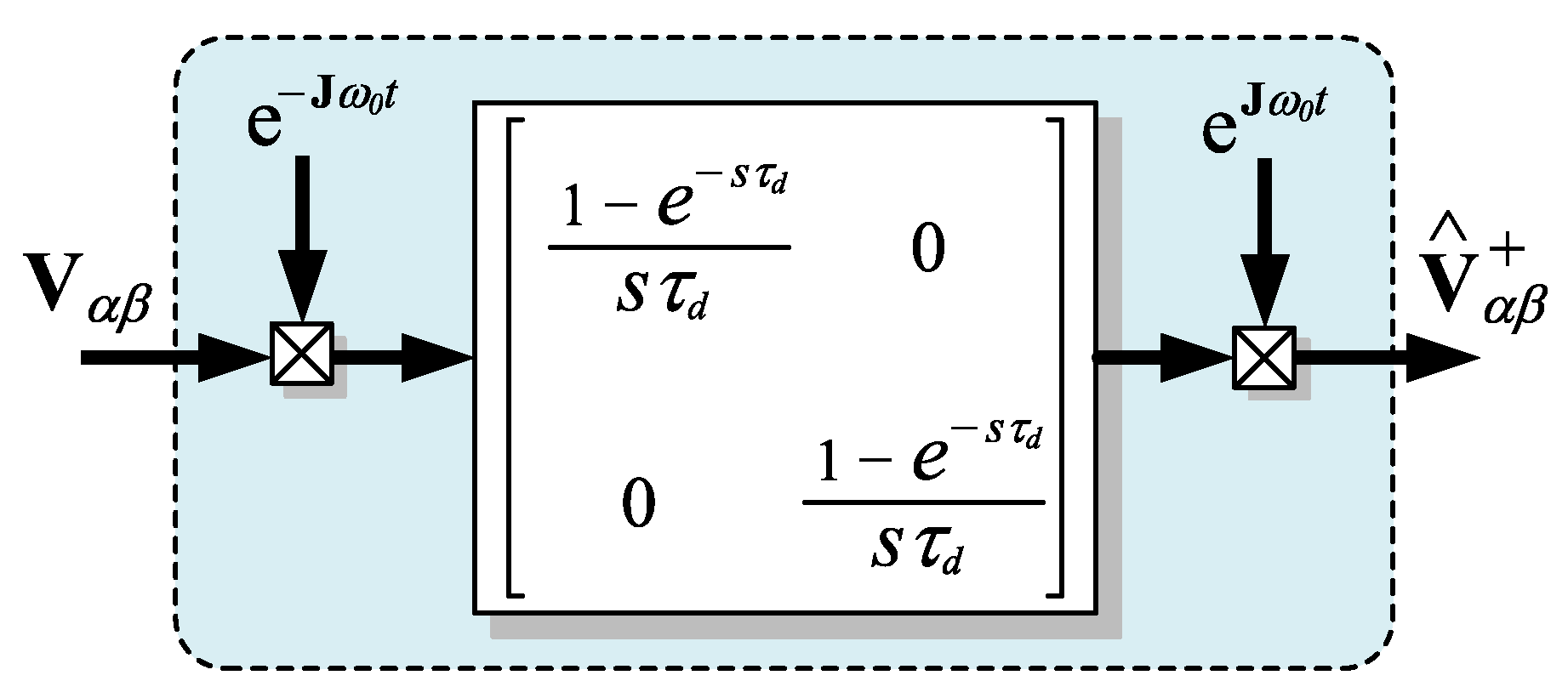

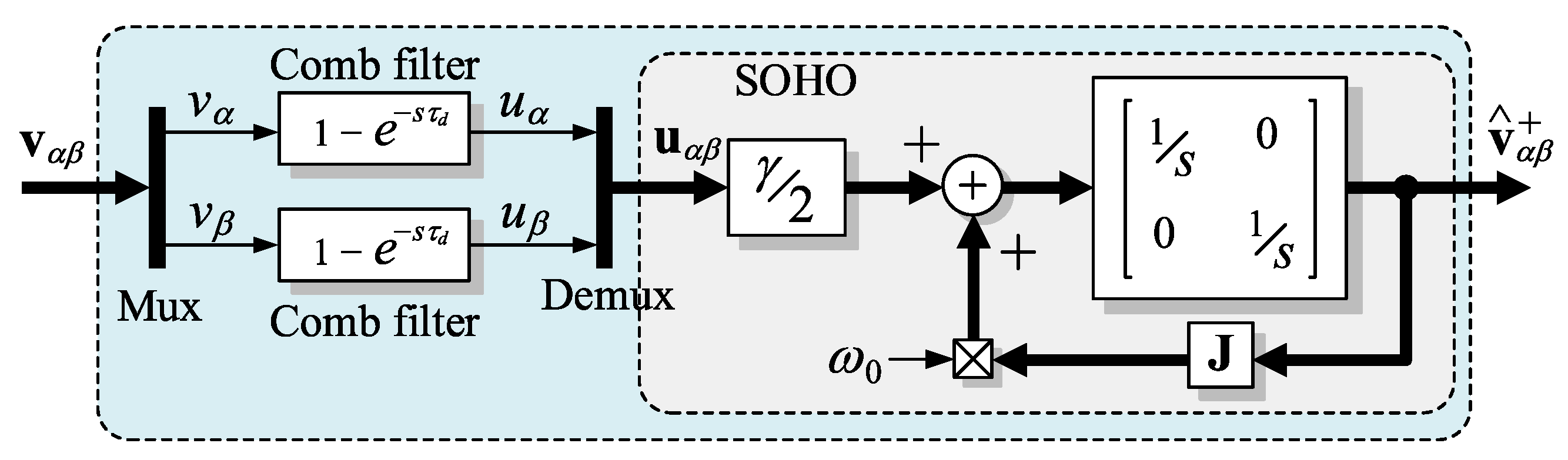

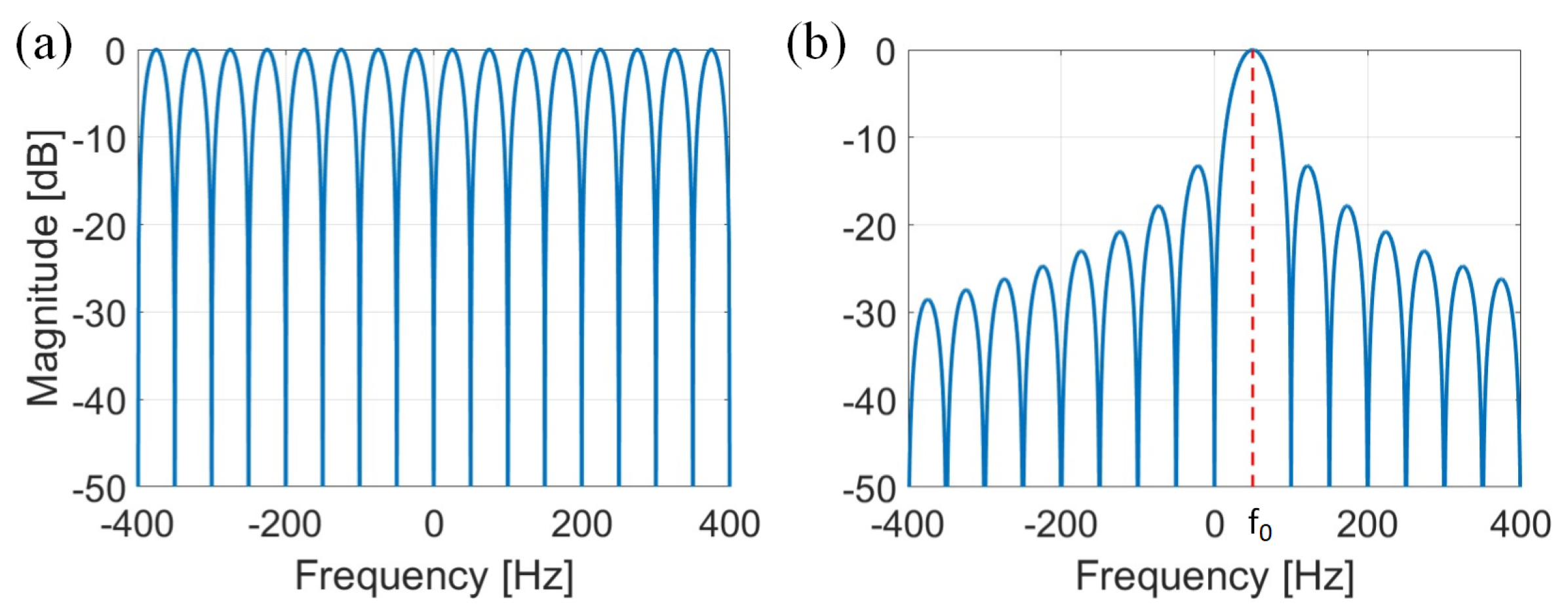

2. Origins of the CF-SOHO

3. Other RPF-SOHO Structures for FPS Detection

3.1. FPS Detector Based on the All-Harmonics RPF

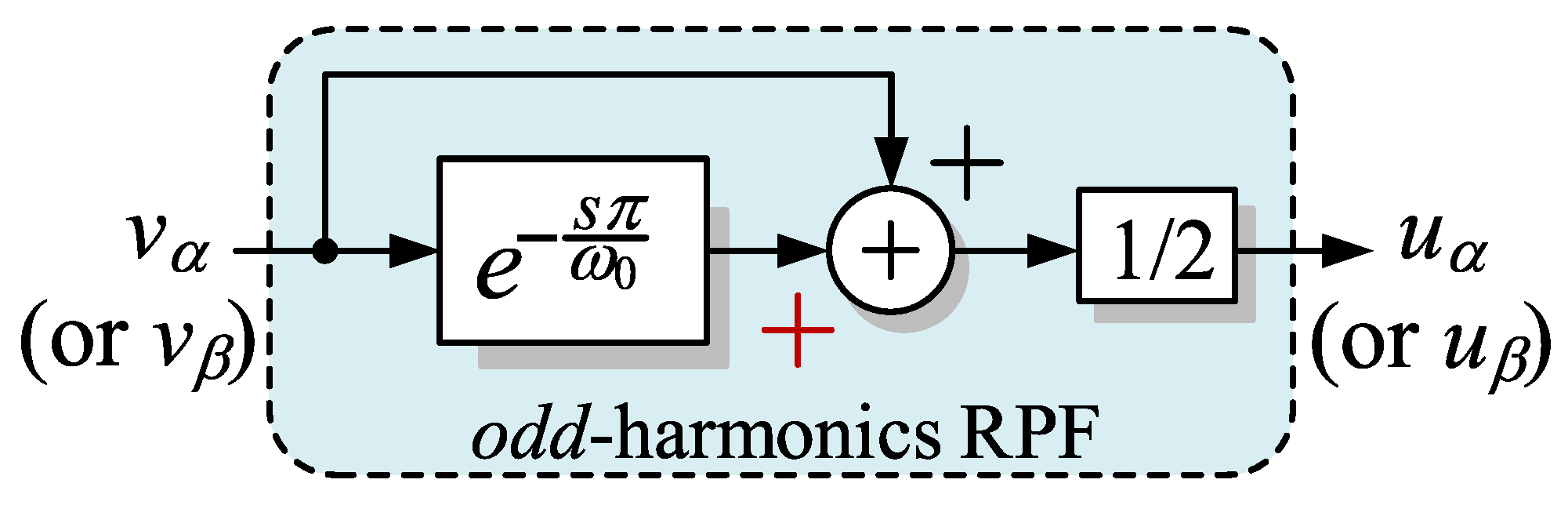

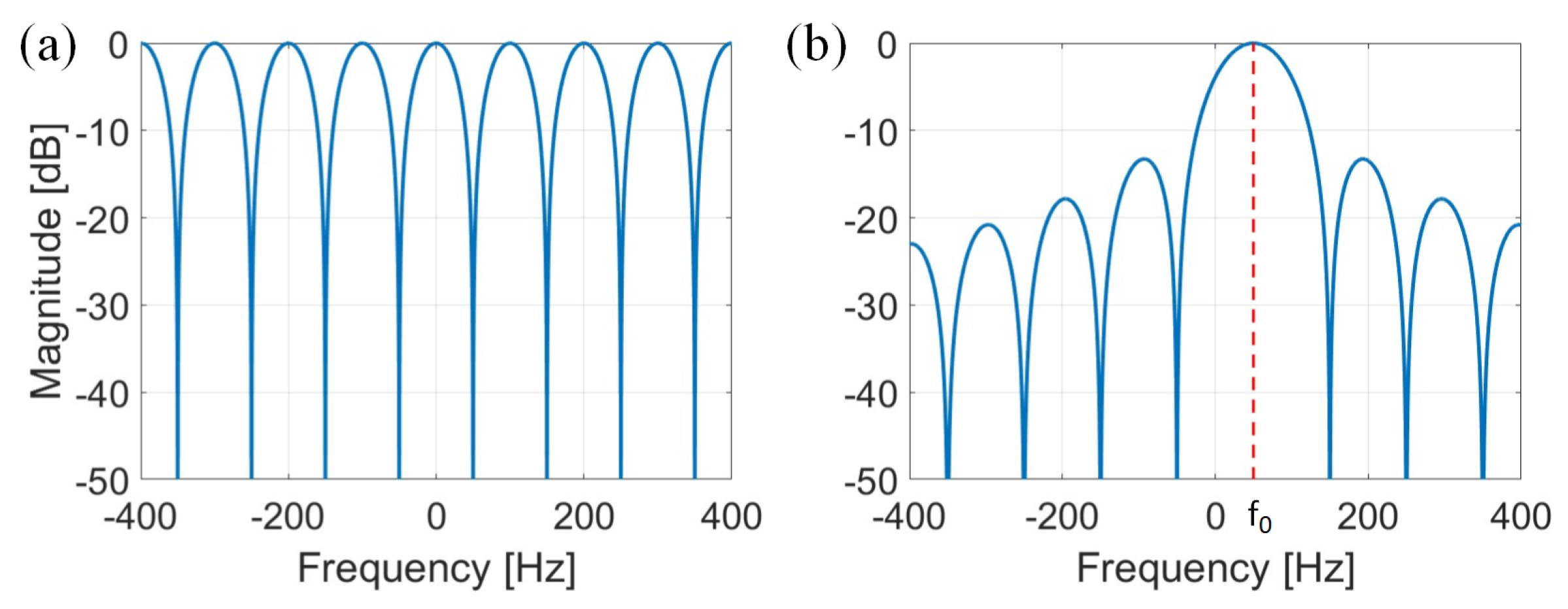

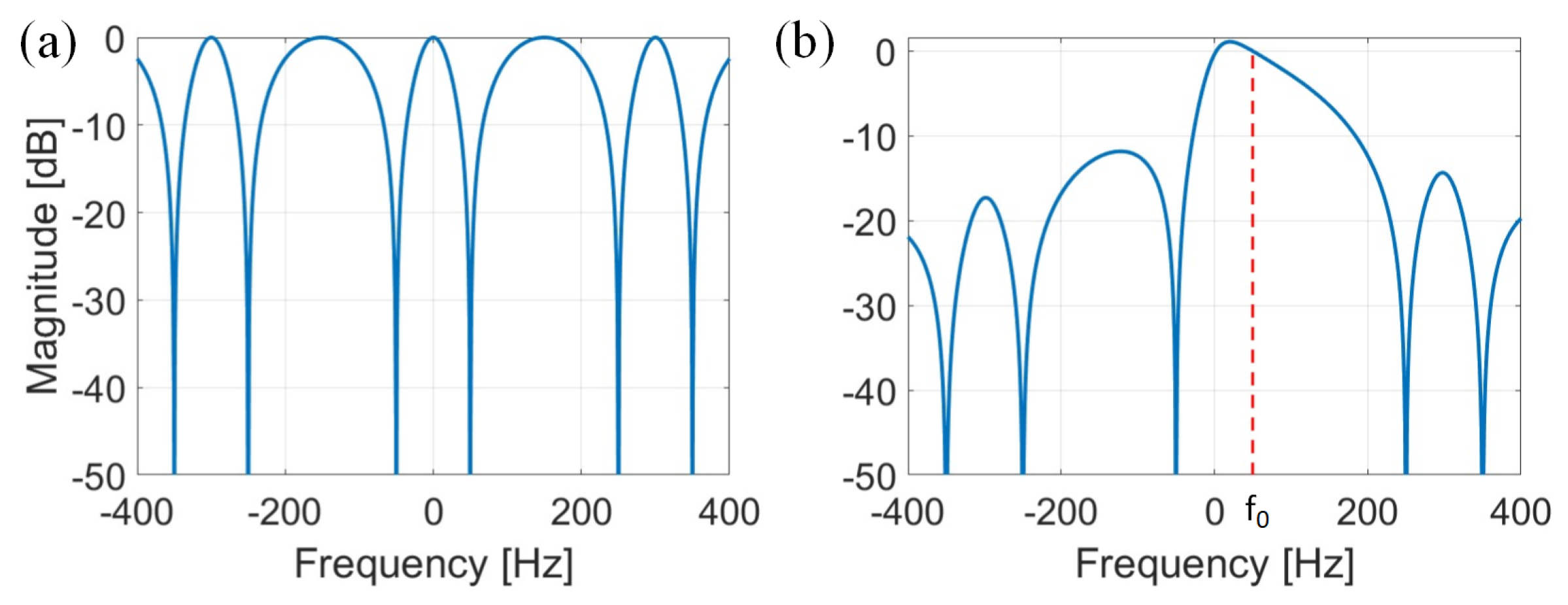

3.2. FPS Detector Based on the Odd-Harmonics RPF

3.3. FPS Detector Based on the Harmonics RPF

3.4. A Note About Implementation Feasibility

4. Real-Time Simulation Results

- Startup considering a pure sinusoidal input signal.

- Inserting unbalance and harmonic distortion in the input signal.

- Inserting simultaneous phase and amplitude jumps into the already unbalanced and distorted input signal.

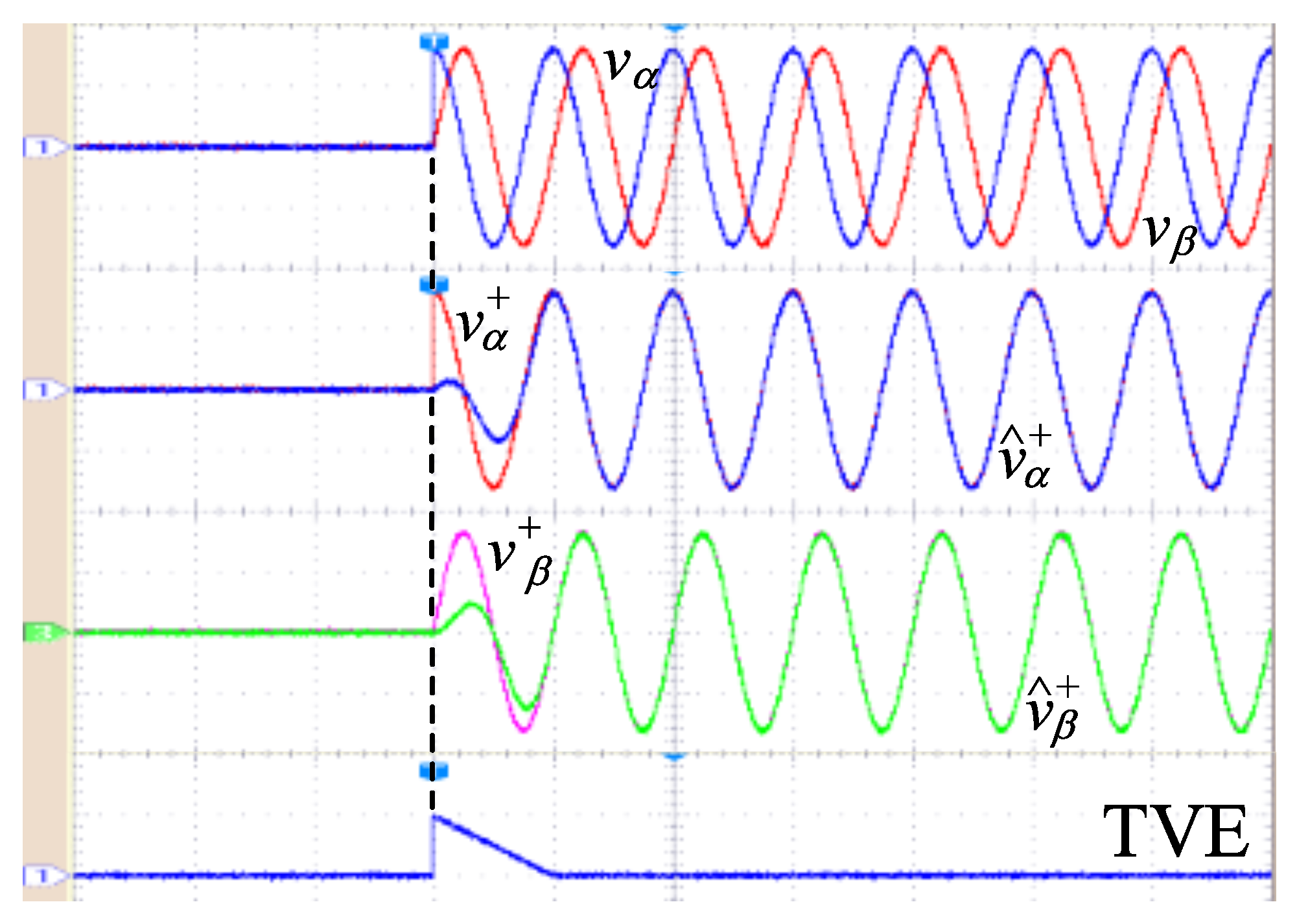

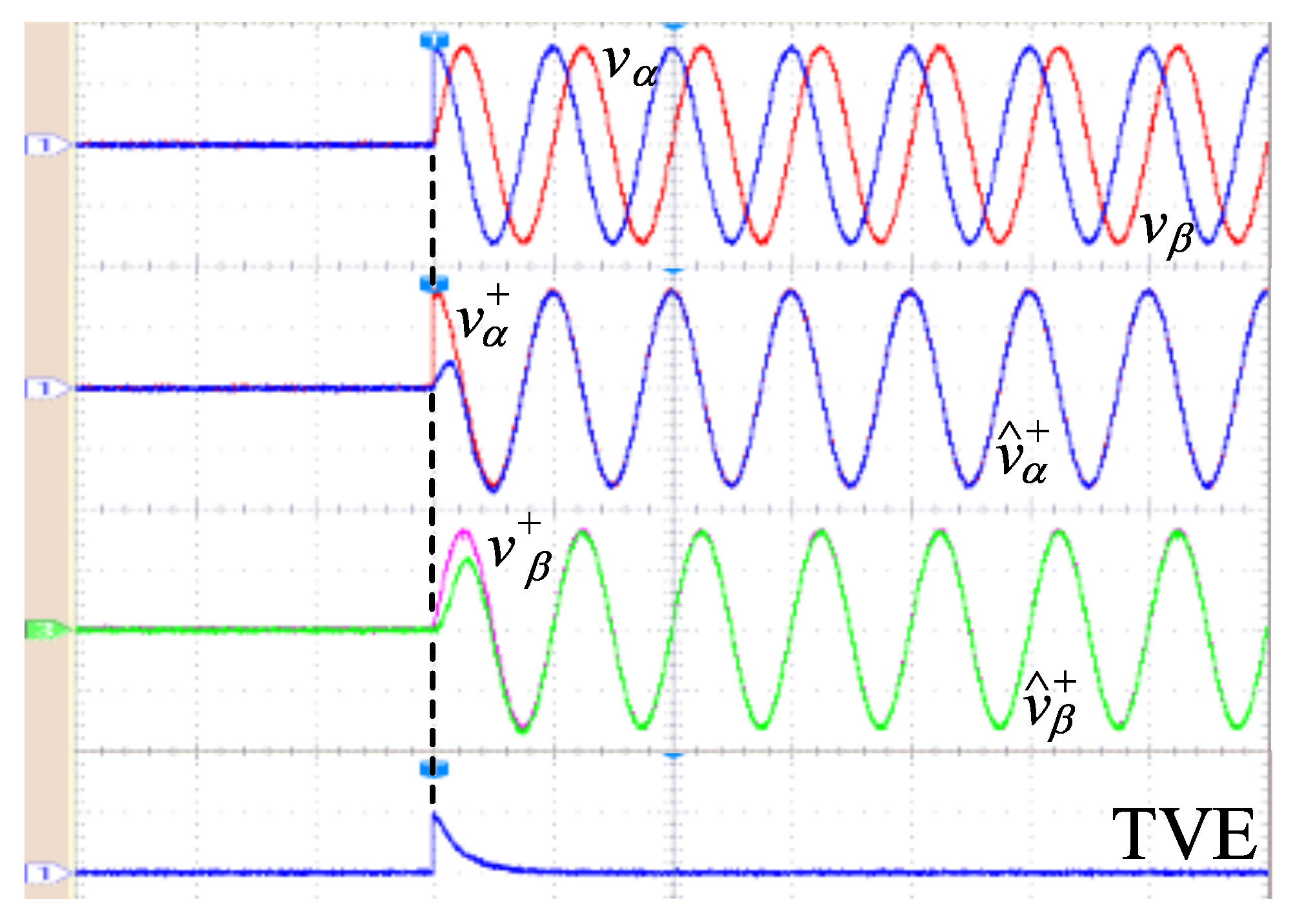

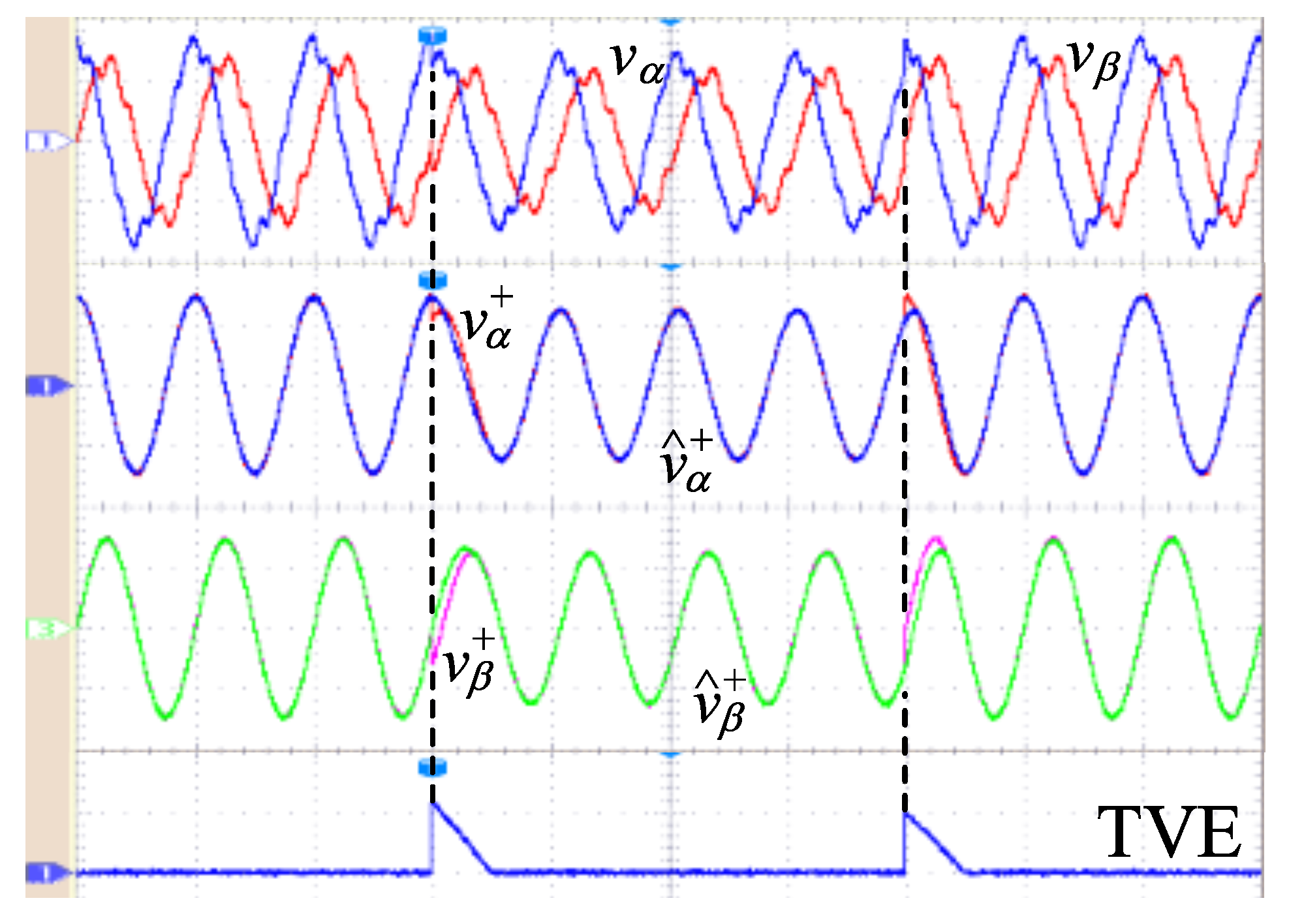

4.1. Startup Test

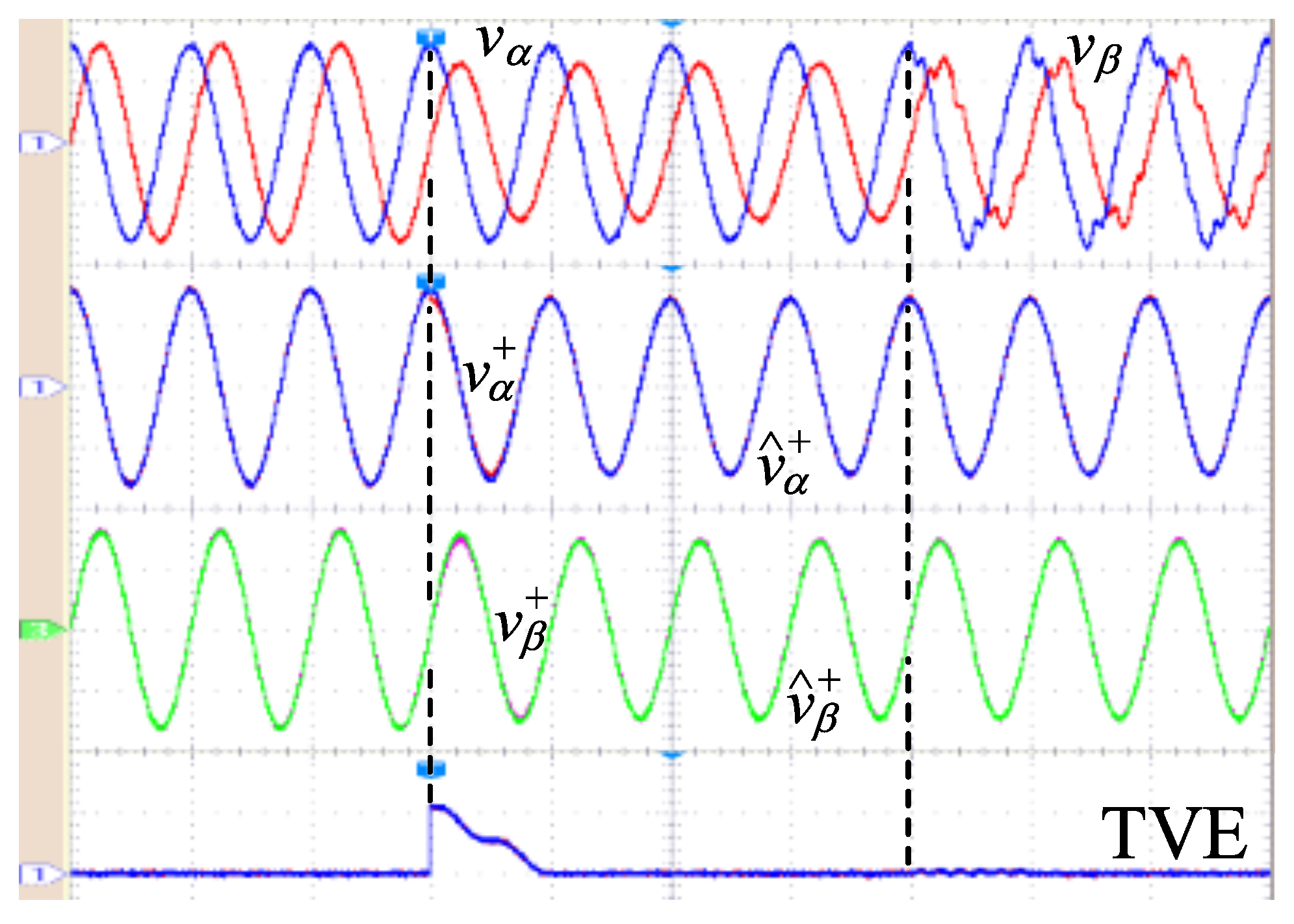

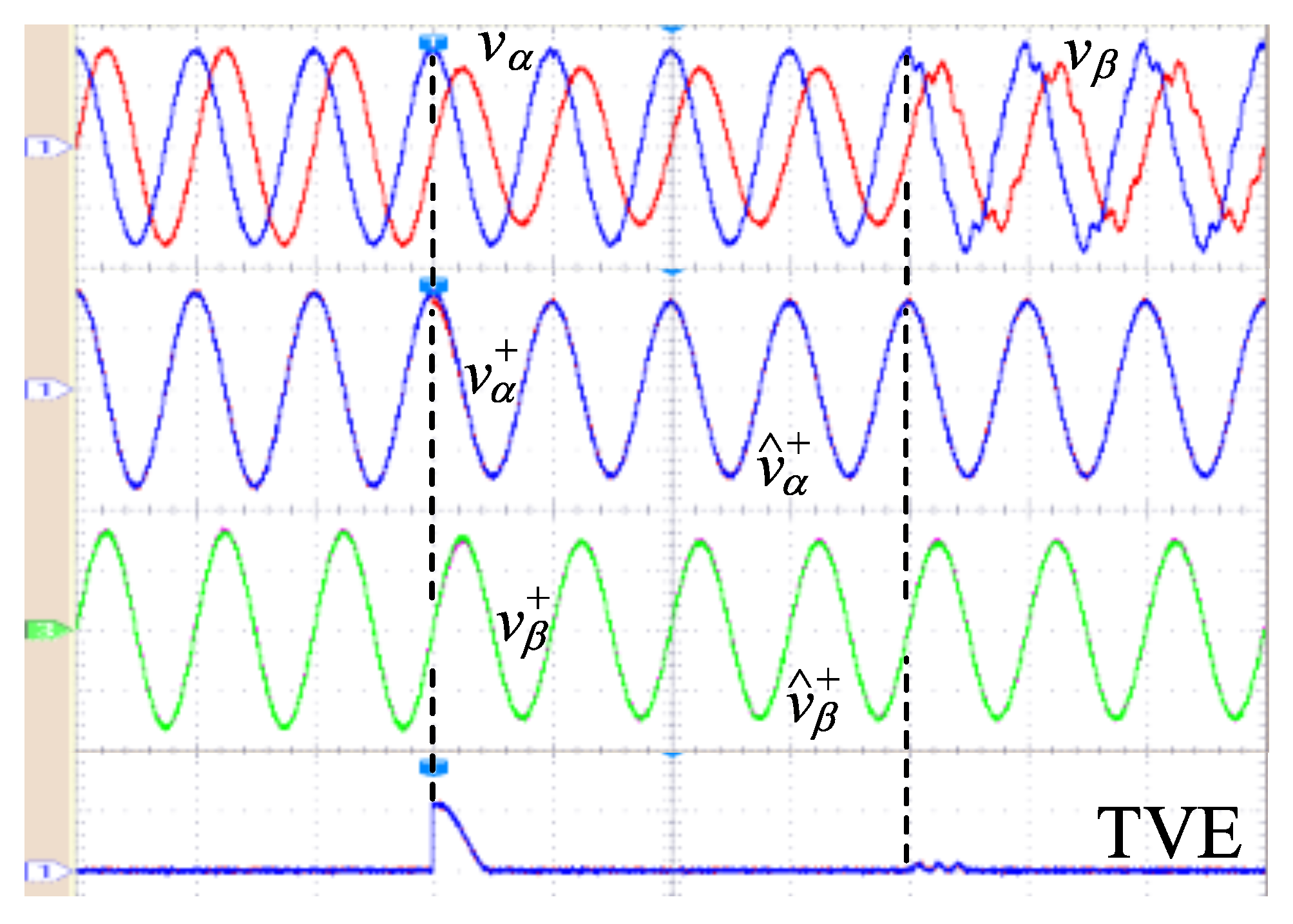

4.2. Unbalance and Harmonic Distortion Test

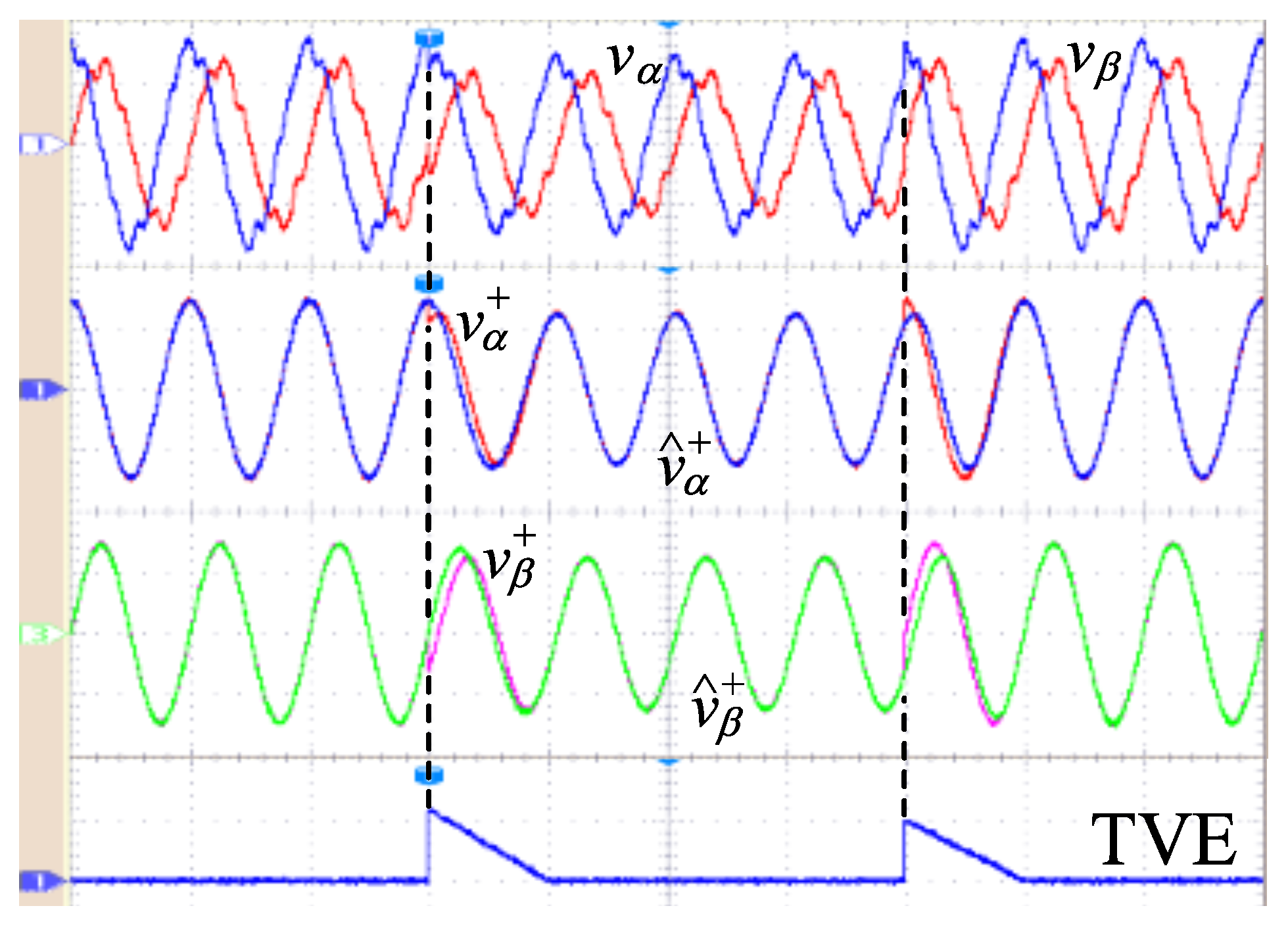

4.3. Test with Unbalance, Harmonic Distortion, Phase, and Amplitude Jumps in the Input Signal

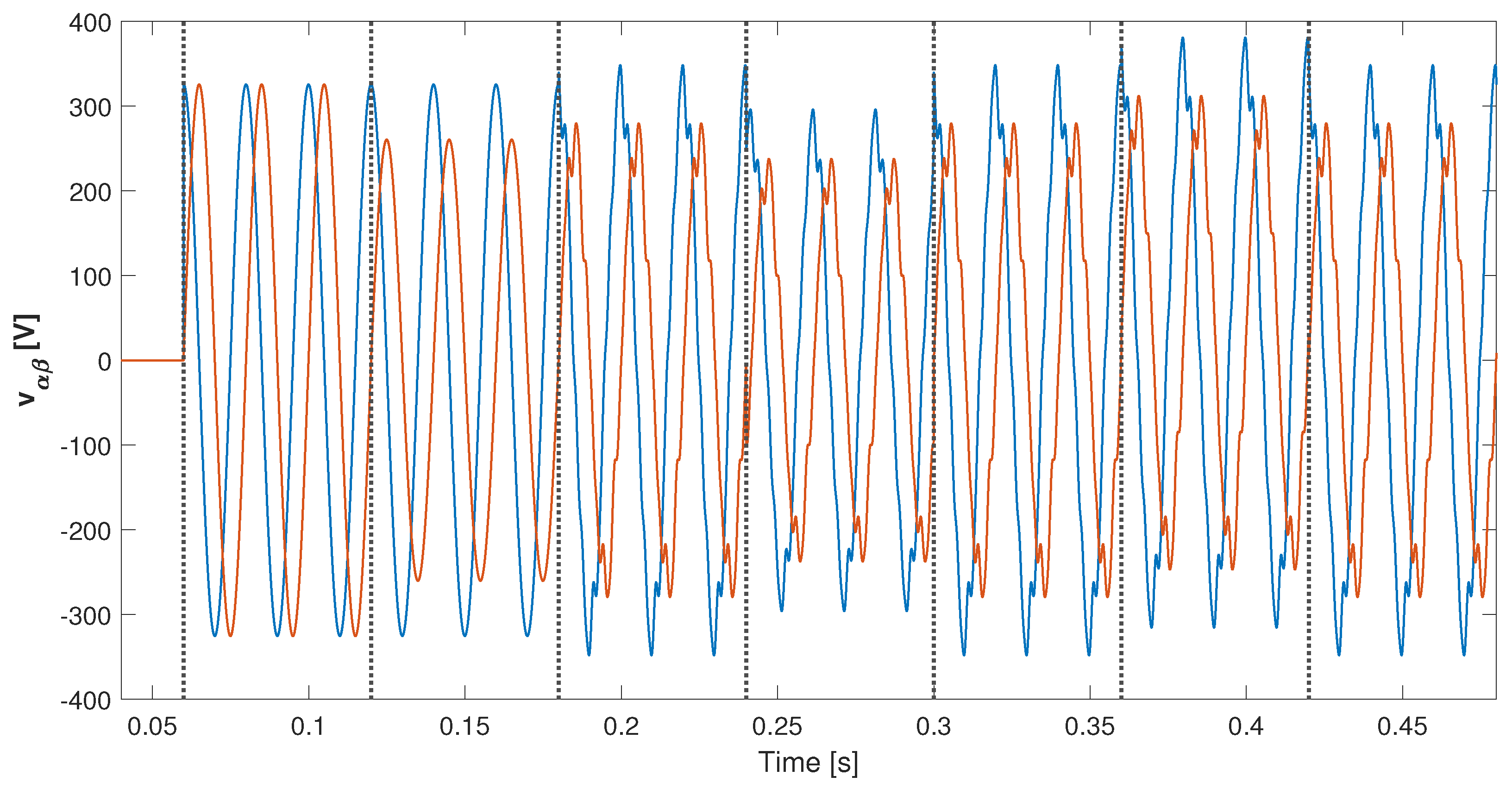

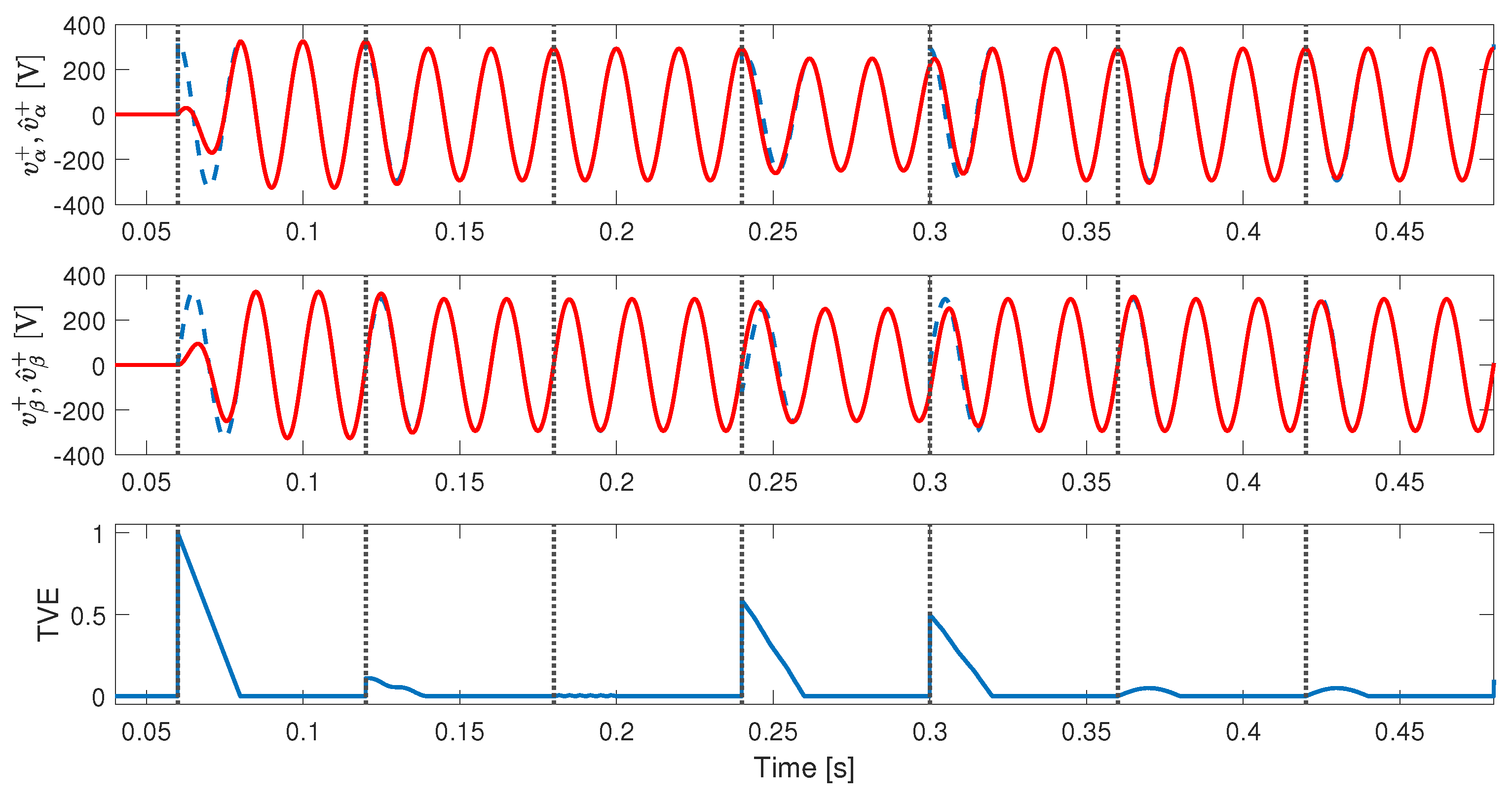

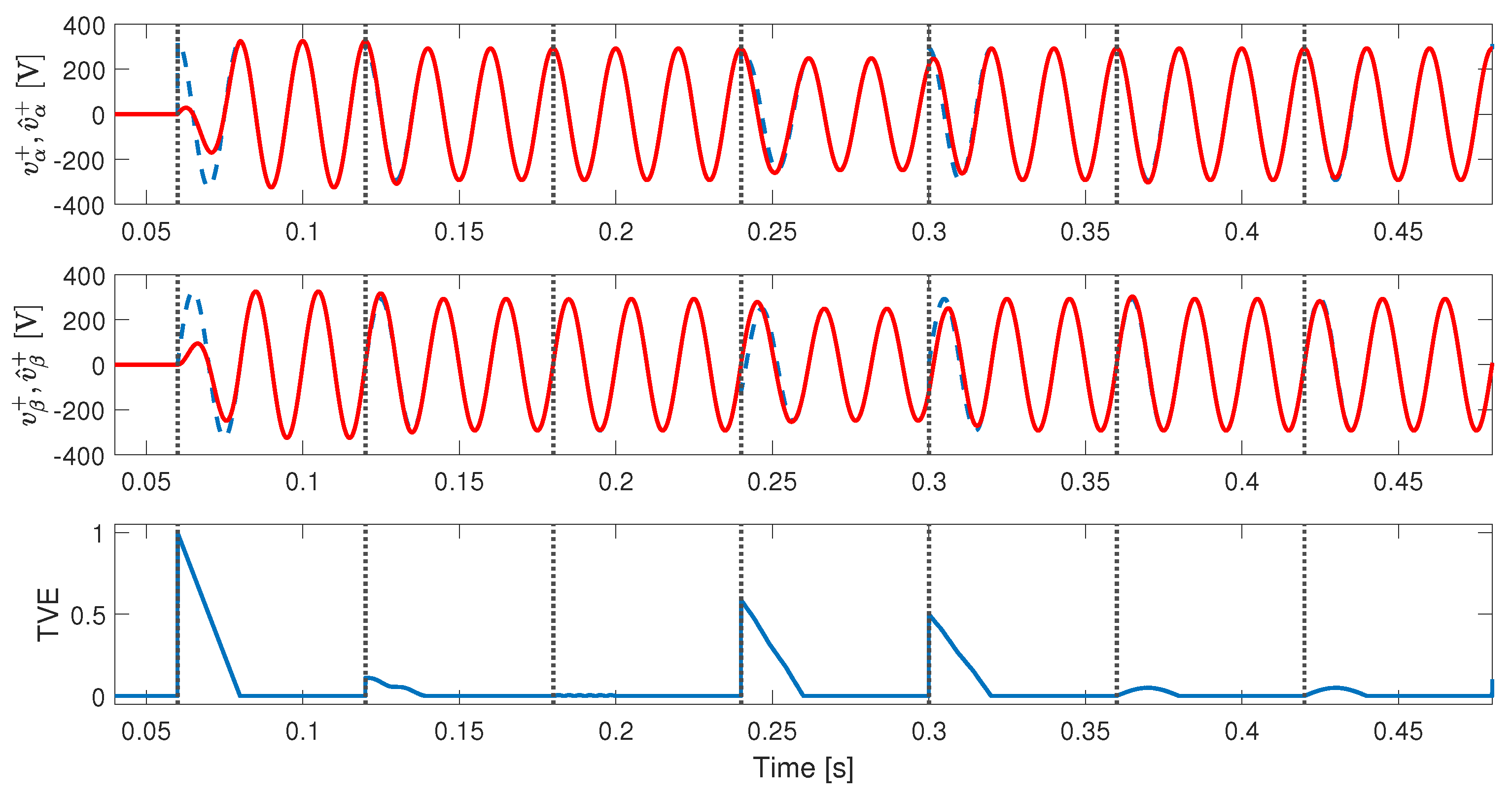

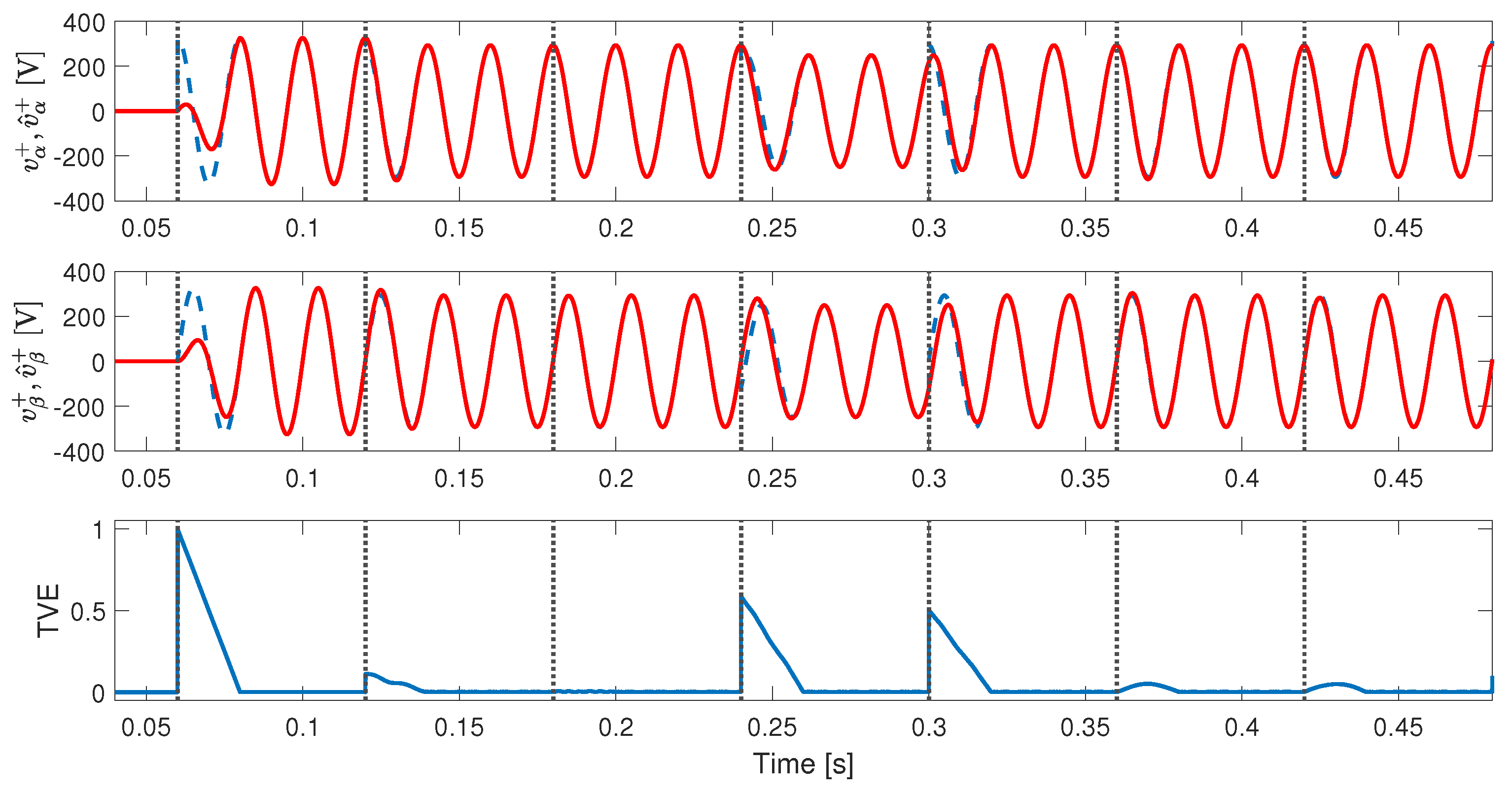

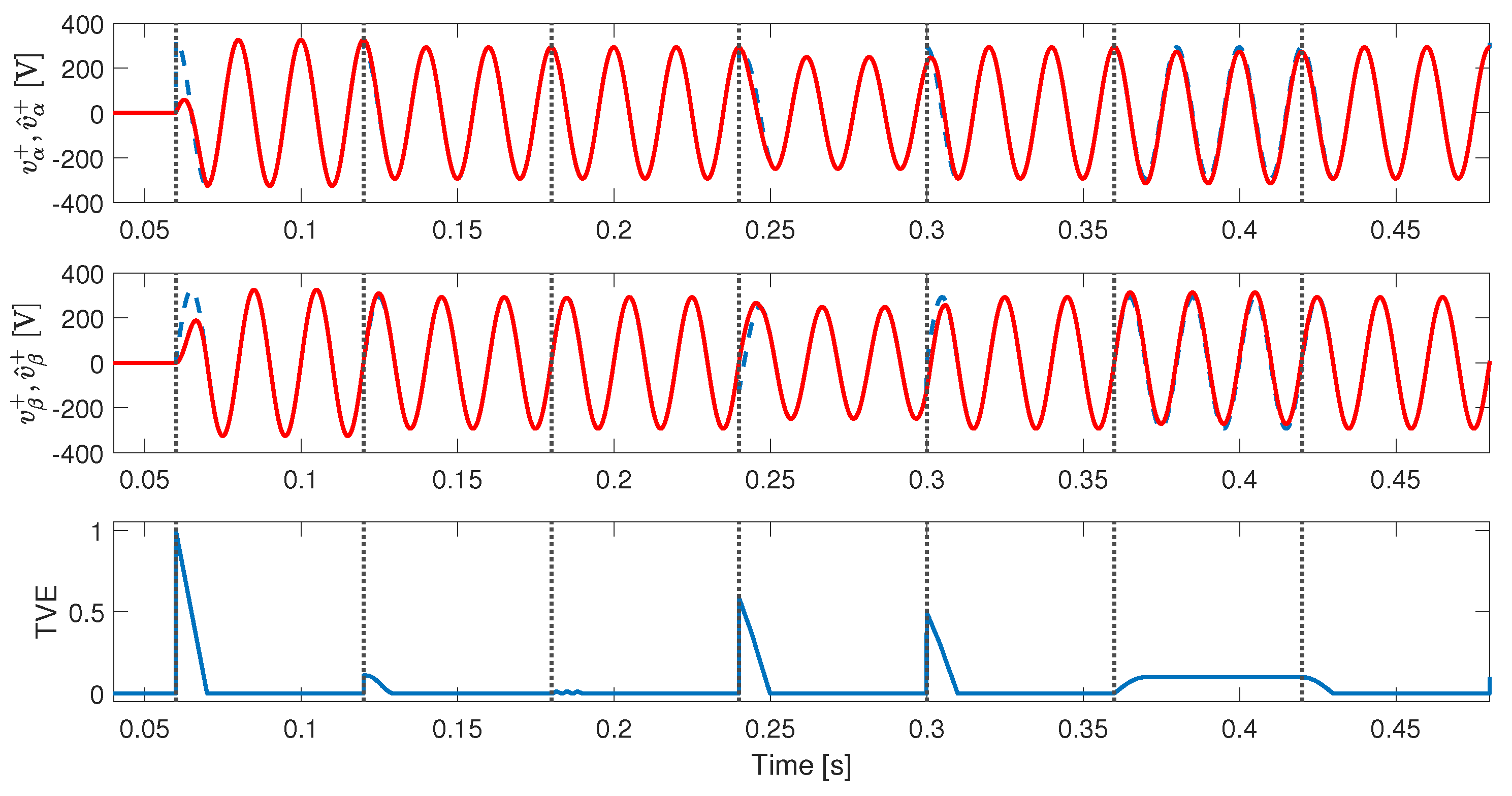

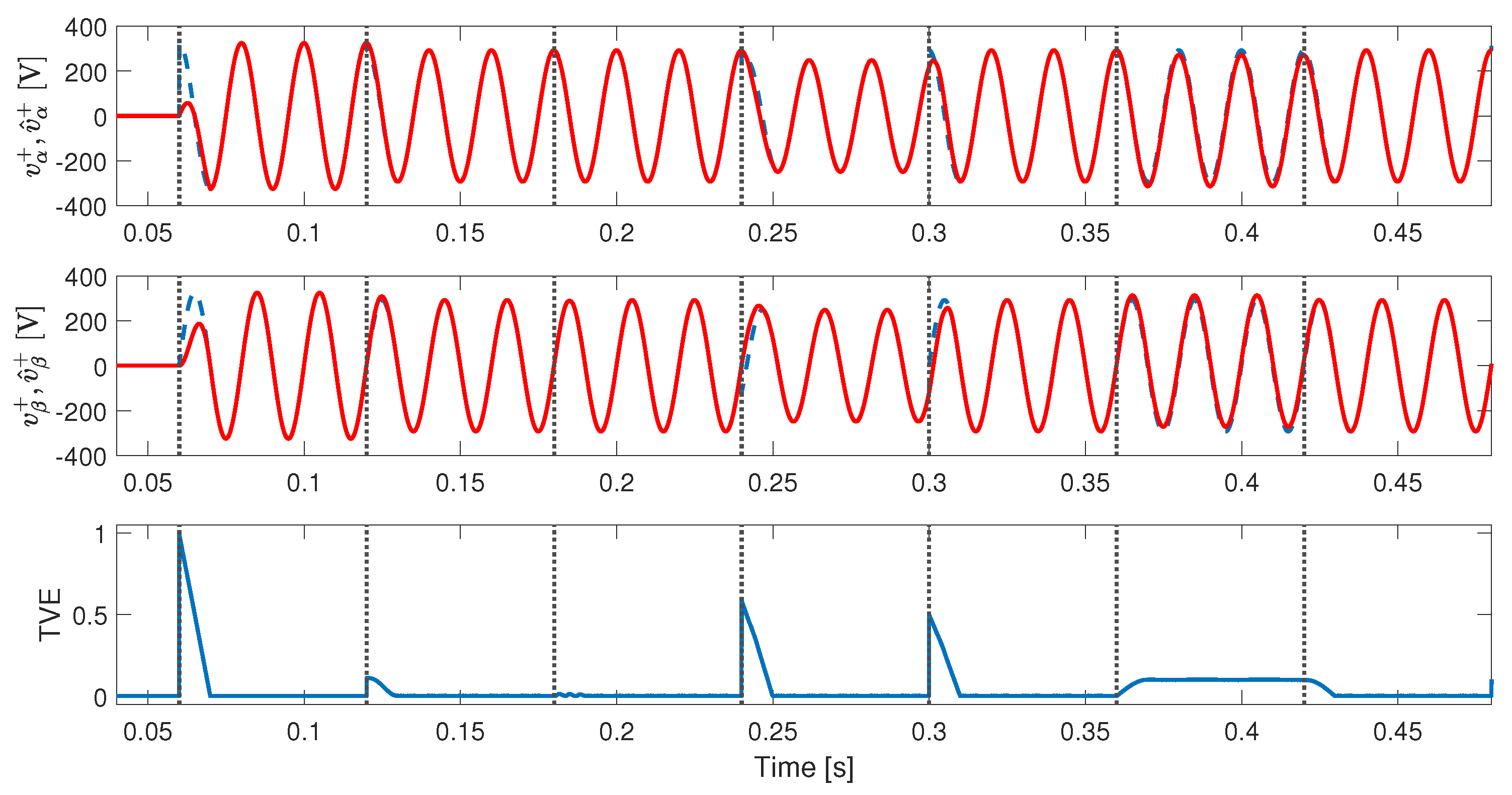

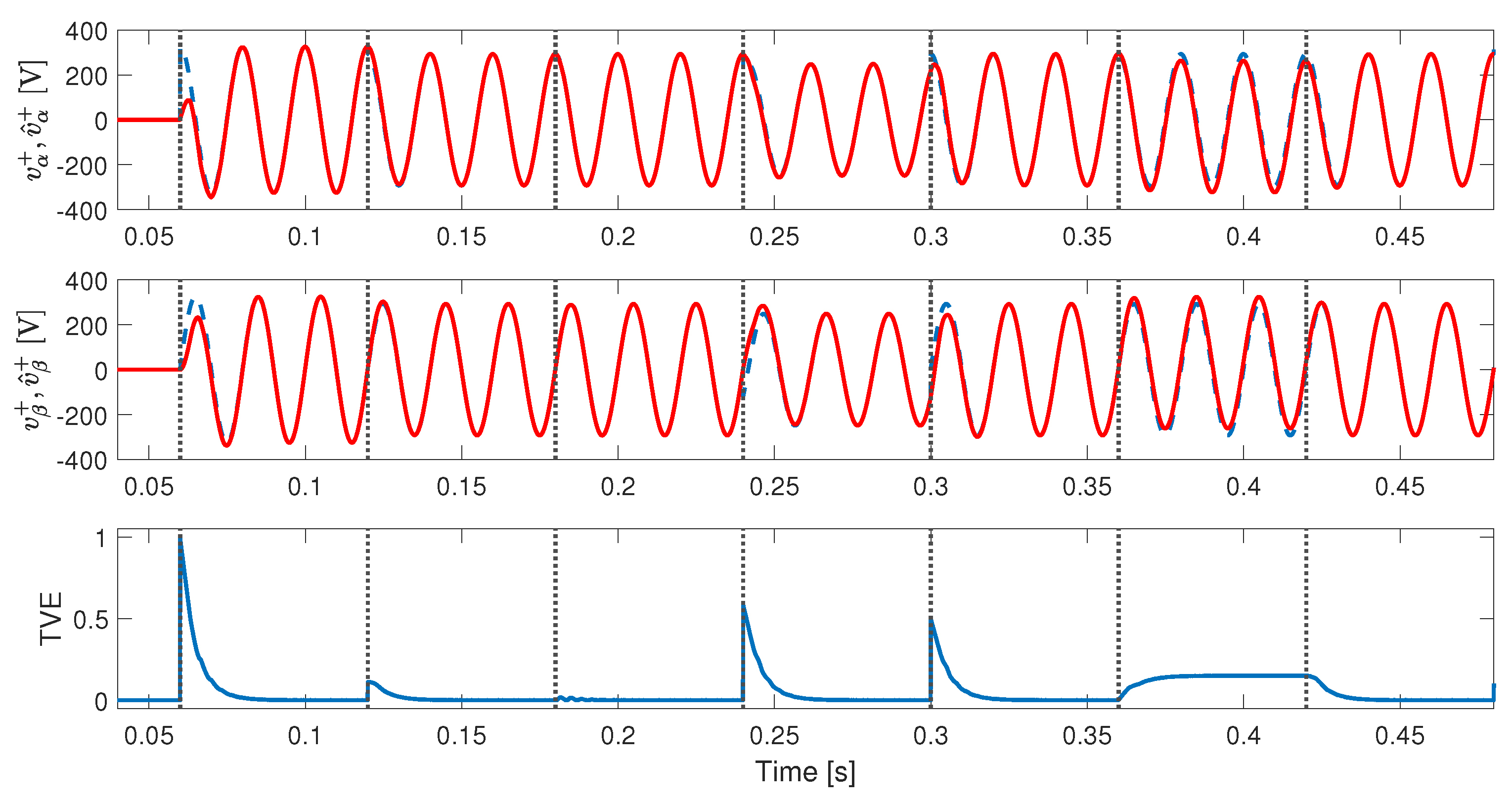

5. Comparison Results

- Test 1: Startup considering a pure sinusoidal input signal, at 0.06 s.

- Test 2: Inserting unbalance, at 0.12 s.

- Test 3: Including of THD (same harmonic components described in Section 4), at 0.18 s.

- Test 4: Adding an amplitude jump of pu and a phase jump of , at 0.24 s.

- Test 5: Introducing an amplitude jump of pu, and a phase jump of , at 0.30 s.

- Test 6: Inserting a DC offset of pu, at 0.36 s.

- Test 7: Including a DC offset of pu, at 0.42 s.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADC | Analog-to-digital converter |

| BIBO | Bounded-input, bounded-output |

| CF | Comb filter |

| DAC | Digital-to-analog converter |

| DC | Direct current |

| DSP | Digital signal processor |

| FIR | Finite impulse response |

| FPS | Fundamental positive sequence |

| MAF | Moving average filter |

| PLL | Phase-locked loop |

| RC | Repetitive control |

| RPF | Repetitive-based prefilter |

| SOGI | Second-order generalized integrator |

| SOHO | Second-order harmonic oscillator |

| THD | Total harmonic distortion |

| TVE | Total vector error |

References

- Nguyen, H.T.; Moursi, M.S.E.; Hosani, K.A.; Al-Sumaiti, A.S.; Durra, A.A. Independent Time-Delay Signal Cancellation for Fast Harmonic-Sequence Filters Targeting Arbitrary Sequences and Frequencies. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 9330–9342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, E.; Ceballos, S.; Pou, J.; Martín, J.L.; Zaragoza, J.; Ibañez, P. Variable-Frequency Grid-Sequence Detector Based on a Quasi-Ideal Low-Pass Filter Stage and a Phase-Locked Loop. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2010, 25, 2552–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wu, W.; Chen, Z. Multiple-Complex Coefficient-Filter-Based Phase-Locked Loop and Synchronization Technique for Three-Phase Grid-Interfaced Converters in Distributed Utility Networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 58, 1194–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, F.A.S.; Cavalcanti, M.C.; de Souza, H.E.P.; Bradaschia, F.; Bueno, E.J.; Rizo, M. A Generalized Delayed Signal Cancellation Method for Detecting Fundamental-Frequency Positive-Sequence Three-Phase Signals. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2010, 25, 1816–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gude, S.; Chu, C.C. Three-Phase PLLs by Using Frequency Adaptive Multiple Delayed Signal Cancellation Prefilters Under Adverse Grid Conditions. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2018, 54, 3832–3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, L.; Escobar, G.; Catzin-Contreras, G.A.; Llanez-Caballero, I.E. A Fixed-Frame Positive-Sequence Extractor: An Alternative to the MAF-Based Park-Filter. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2022, 29, 2492–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahoui, A.; Boukais, B.; Mesbah, K.; Otmane-Cherif, T. Neural Networks Based Frequency-Locked Loop for Grid Synchronization Under Unbalanced and Distorted Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Electrical Engineering (ICEE), Istanbul, Turkey, 25–27 September 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranbeigi, M.; Kandula, P.; Divan, D. A Data-Driven Approach for Grid Synchronization Based on Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Vancouver, Canada, 10–14 October 2021; pp. 2985–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manigandan, M.; Banakara, B. An intelligent grid synchronization technique for microgrid system with smooth power quality using chaotic grey wolf optimization-random forest algorithm scheme. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2021, 31, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajak, M.K.; Pudur, R. Adaptive hybrid PSO-GD optimized phase-locked loop for robust grid synchronization in renewable energy systems. COMPEL—Int. J. Comput. Math. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2025, 44, 566–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Bifaretti, S.; Pipolo, S.; Odhano, S.; Zanchetta, P. A Novel Repetitive Controller Assisted Phase-Locked Loop with Self-Learning Disturbance Rejection Capability for Three-Phase Grids. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2020, 8, 1870–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Li, X.; Liu, Q.; Chen, J.; Xin, Z.; Loh, P.C. Frequency-Locked Loop Based on a Repetitive Controller for Grid Synchronization Systems. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 154861–154870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Nakano, M.; Kubo, T.; Matsumoto, S.; Baba, H. High Accuracy Control of a Proton Synchrotron Magnet Power Supply. IFAC Proc. 1981, 14, 3137–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, S.; Omata, T.; Nakano, M. Synthesis of repetitive control systems and its application. In Proceedings of the 1985 24th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 11–13 December 1985; pp. 1387–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, G.; Leyva-Ramos, J.; Martinez, P.; Valdez, A. A repetitive-based controller for the boost converter to compensate the harmonic distortion of the output Voltage. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2005, 13, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadegh, N.; Guglielmo, K. Design and implementation of adaptive and repetitive controllers for mechanical manipulators. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 1992, 8, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R.L.; Sergi, F. Using Repetitive Control to Enhance Force Control During Human-Robot Interaction in Quasi-Periodic Tasks. IEEE Trans. Med Robot. Bionics 2023, 5, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillerstrom, G. Adaptive suppression of vibrations - a repetitive control approach. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 1996, 4, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chen, P.; Pan, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, Q.; Cui, P. High-Precision Suppression of Harmonic Vibration Force by Repetitive Controller With Triple-Loop Structure. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 10821–10828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Wang, D. Digital repetitive controlled three-phase PWM rectifier. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2003, 18, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattavelli, P.; Marafao, F. Repetitive-based control for selective harmonic compensation in active power filters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2004, 51, 1018–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, B.; Wang, D.; Wang, J. High-Performance Repetitive Control of PWM DC-AC Converters With Real-Time Phase-Lead FIR Filter. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2006, 53, 768–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y. Novel Fractional-Order Repetitive Controller Based on Thiran IIR Filter for Grid-Connected Inverters. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 82015–82024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayard, D. A general theory of linear time-invariant adaptive feedforward systems with harmonic regressors. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2000, 45, 1983–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, G.; Hernandez-Briones, P.G.; Martinez, P.R.; Hernandez-Gomez, M.; Torres-Olguin, R.E. A Repetitive-Based Controller for the Compensation of 6ℓ±1 Harmonic Components. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2008, 55, 3150–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, G.; Martinez, P.R.; Leyva-Ramos, J. Analog Circuits to Implement Repetitive Controllers With Feedforward for Harmonic Compensation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2007, 54, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golestan, S.; Ramezani, M.; Guerrero, J.; Freijedo, F.; Monfared, M. Moving Average Filter Based Phase-Locked Loops: Performance Analysis and Design Guidelines. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2014, 29, 2750–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, L.; Escobar, G.; Catzin-Contreras, G.A. Assessment of the DSC Technique for Positive-Sequence Extraction in Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 8533–8539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, K. Discrete-time Control Systems; Prentice-Hall International, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1995; Chapter 5; pp. 314–358. [Google Scholar]

- EN 50160; Voltage Characteristics of Electricity Supplied by Public Distribution Systems. European Standard: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- Bollen, M.H.J. Understanding Power Quality Problems: Voltage Sags and Interruptions; IEEE Press Series on Power Engineering; IEEE Press: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- IEEE Std 1159-2019; IEEE Recommended Practice for Monitoring Electric Power Quality. IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–98. [CrossRef]

- Escobar, G.; Mayo-Maldonado, J.C.; del Puerto-Flores, D.; Valdez-Resendiz, J.E.; Micheloud, O.M. A Single-Phase Globally Stable Frequency-Locked Loop Based on the Second-Order Harmonic Oscillator Model. Electronics 2021, 10, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, M. Characterisation of voltage sags experienced by three-phase adjustable-speed drives. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 1997, 12, 1666–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, P.; Teodorescu, R.; Candela, I.; Timbus, A.V.; Liserre, M.; Blaabjerg, F. New positive-sequence voltage detector for grid synchronization of power converters under faulty grid conditions. In Proceedings of the 2006 37th IEEE Power Electronics Specialists Conference, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 18–22 June 2006; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Test Number | CF- SOHO | All- SOHO | All- SOGI | MAF- Park | Odd- SOHO | Odd- SOGI | SOHO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0197 | 0.0197 | 0.0197 | 0.0198 | 0.0098 | 0.0098 | 0.0218 |

| 2 | 0.0173 | 0.0173 | 0.0175 | 0.0173 | 0.0080 | 0.0083 | 0.0139 |

| 3 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0088 | 0.0086 | 0.0056 |

| 4 | 0.0196 | 0.0196 | 0.0195 | 0.0195 | 0.0098 | 0.0098 | 0.0200 |

| 5 | 0.0195 | 0.0195 | 0.0195 | 0.0195 | 0.0097 | 0.0097 | 0.0190 |

| 6 | 0.0186 | 0.0186 | 0.0187 | 0.0188 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. |

| 7 | 0.0185 | 0.0185 | 0.0185 | 0.0186 | 0.0093 | 0.0093 | 0.0159 |

| Test Number | CF- SOHO | All- SOHO | All- SOGI | MAF- Park | Odd- SOHO | Odd- SOGI | SOHO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.9958 | 0.9958 | 0.9958 | 0.9958 | 0.9916 | 0.9916 | 0.9875 |

| 2 | 0.1110 | 0.1110 | 0.1109 | 0.1090 | 0.1110 | 0.1109 | 0.1110 |

| 3 | 0.0062 | 0.0060 | 0.0071 | 0.0079 | 0.0127 | 0.0130 | 0.0181 |

| 4 | 0.5868 | 0.5868 | 0.5852 | 0.5856 | 0.5845 | 0.5830 | 0.5823 |

| 5 | 0.4978 | 0.4978 | 0.4984 | 0.4978 | 0.4959 | 0.4965 | 0.4940 |

| 6 | 0.0504 | 0.0495 | 0.0514 | 0.0492 | 0.1000 | 0.1016 | 0.1506 |

| 7 | 0.0504 | 0.0505 | 0.0492 | 0.0518 | 0.1004 | 0.0991 | 0.1504 |

| FPS Detector | Execution Time | DC Offset Removal | Steady-State Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| CF-SOHO | 0.008 | Yes | No |

| All-SOHO | 0.018 | Yes | No |

| All-SOGI | 0.019 | Yes | No |

| MAF-Park | 0.033 | Yes | No |

| Odd-SOHO | 0.010 | No | Only in DC offset test |

| Odd-SOGI | 0.017 | No | Only in DC offset test |

| -SOHO | 0.012 | No | Only in DC offset test |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Catzin-Contreras, G.A.; Escobar, G.; Ibarra, L.; Valdez-Fernandez, A.A. A Family of Fundamental Positive Sequence Detectors Based on Repetitive Schemes. Energies 2025, 18, 6283. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236283

Catzin-Contreras GA, Escobar G, Ibarra L, Valdez-Fernandez AA. A Family of Fundamental Positive Sequence Detectors Based on Repetitive Schemes. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6283. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236283

Chicago/Turabian StyleCatzin-Contreras, Glendy Anyali, Gerardo Escobar, Luis Ibarra, and Andres Alejandro Valdez-Fernandez. 2025. "A Family of Fundamental Positive Sequence Detectors Based on Repetitive Schemes" Energies 18, no. 23: 6283. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236283

APA StyleCatzin-Contreras, G. A., Escobar, G., Ibarra, L., & Valdez-Fernandez, A. A. (2025). A Family of Fundamental Positive Sequence Detectors Based on Repetitive Schemes. Energies, 18(23), 6283. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236283