1. Introduction

Current transport initiatives are focused on reducing greenhouse gas emissions from transport. A preferred approach to this challenge is to lower emissions generated during vehicle operation. The introduction of electric vehicles (EVs) into transport systems represents a potential means of mitigating this problem. Such initiatives are referred to in the literature as electromobility, which, in the accepted interpretation, encompasses all aspects of transporting people and goods using EVs.

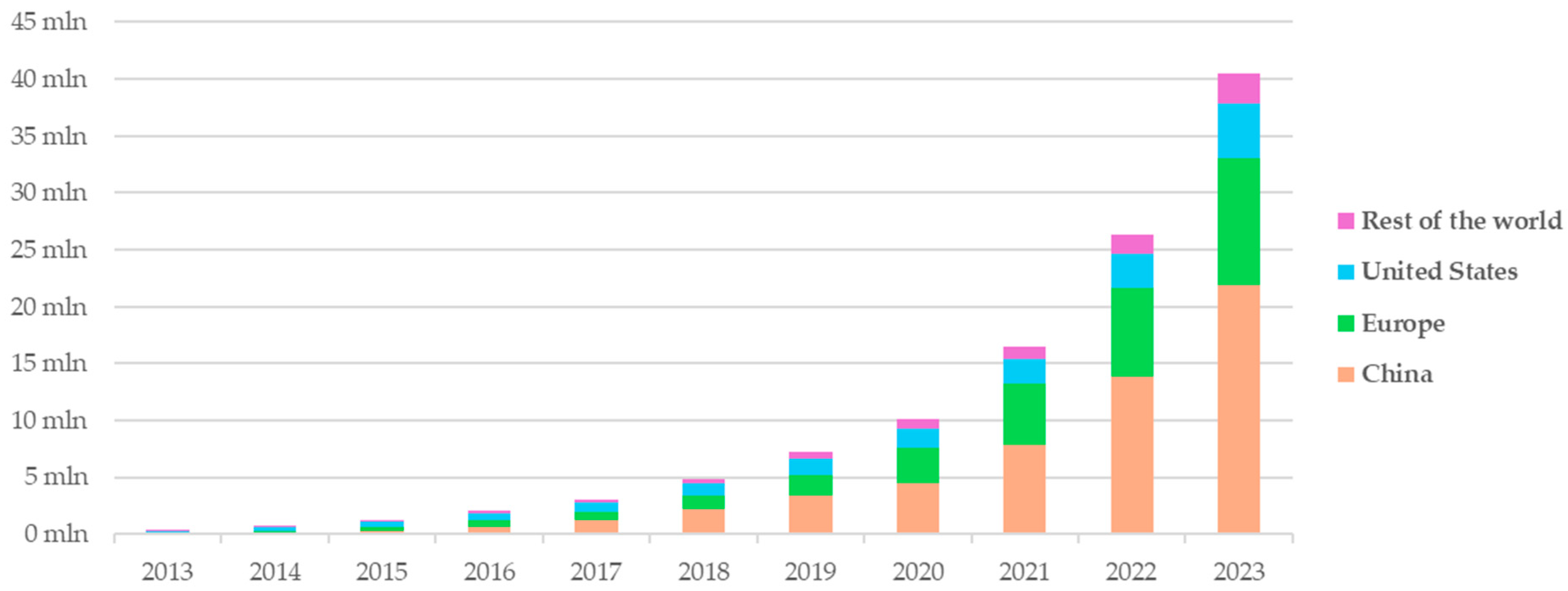

Findings presented in the latest International Energy Agency (IEA) report reveal that [

1], the market share of electric vehicles is forecasted for 2024 with the share estimated at around 45% in China, 25% in Europe, and slightly above 11% in the United States. Therefore, upward emerging trends in the evolution of electromobility (excluding bus sales in the Chinese market) are observed despite low margins, instability in the prices of metals essential for battery manufacturing, elevated inflation levels, and the discontinuation of purchase incentives in several countries (

Figure 1)—although not all markets maintain growth in electric car sales (e.g., Germany, Norway) [

1].

In the process of developing electromobility, a key solution appears to be EVs and infrastructure for road transport adapted to the needs of this development. With this in mind, the problem under analysis identifies electric vehicles, road networks and facilities adapted to support these types of vehicles. The category of EVs encompasses light-duty and heavy-duty electric vehicles (eLDVs and eHDVs), electric bicycles, as well as other forms of personal electric mobility. Moreover, the EV category encompasses battery electric vehicles (BEVs) with an electric engine or motors that utilize electrical energy stored in a battery installed within the vehicle. Technically, it is important that these batteries are capable of being recharged numerous times from external electricity sources located outside the vehicle. Such energy sources are available at individual vehicle parking spaces and at publicly accessible points such as parking lots, charging stations, hotels, etc.

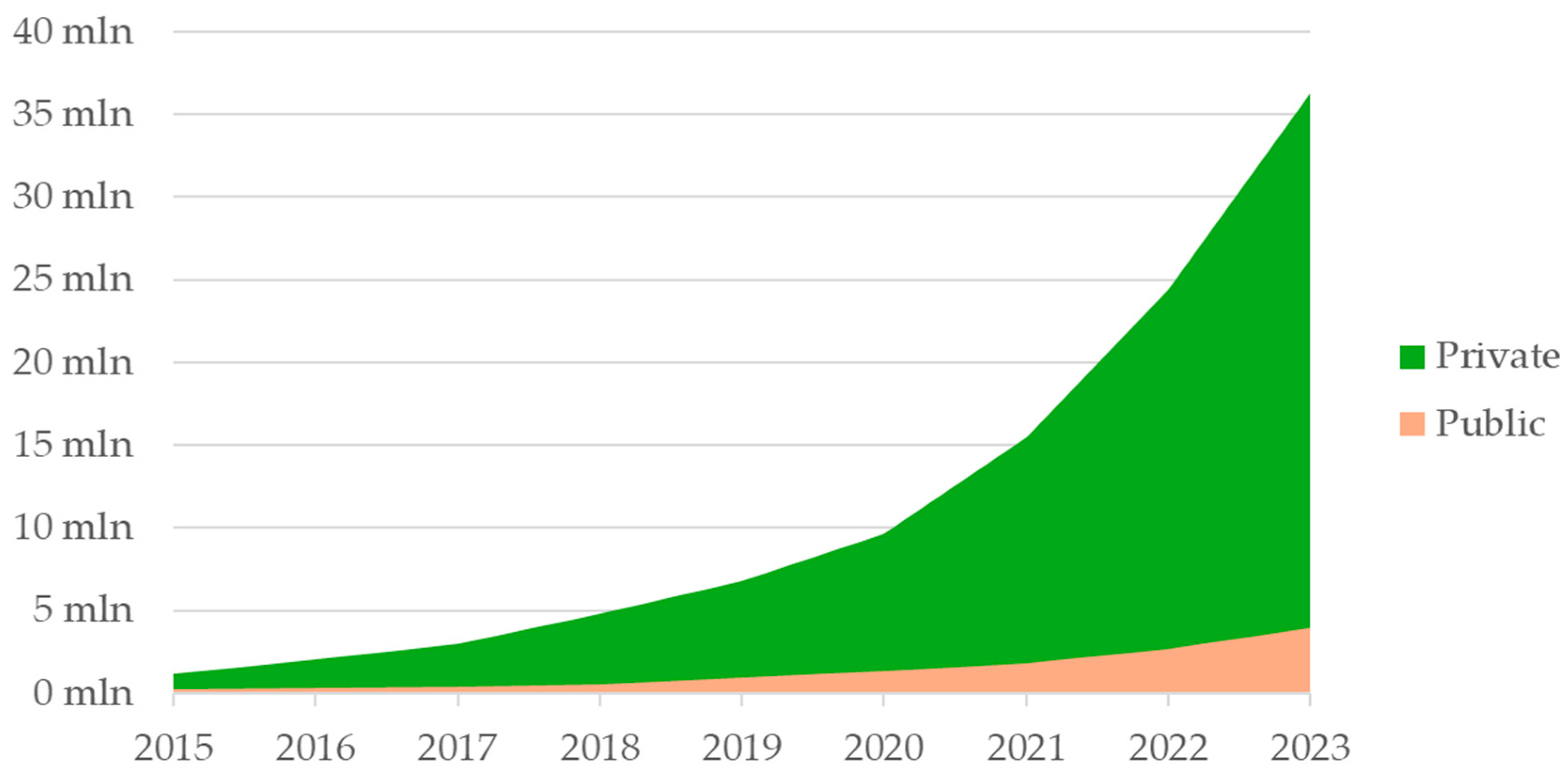

As the sales of electric cars grow, so does the sales of electric cars, and the power of charging points per 1 electric vehicle globally is at the level of 3–5 kW/electric vehicle (

Figure 2) [

1].

In line with the Stated Policies Scenario, the number of EVs will grow by an average of 23% annually between 2023 and 2035, reaching 525 million in 2035, compared to just under 45 million in 2023. During the same period, the global number of public charging points will increase six-fold, from just under 4 million to almost 23 million [

1]. The EV market in Poland is witnessing rapid development. Their number in this country increased fivefold between 2020 and 2023, from 29,060 to 124,392. Meanwhile, the number of hydrogen-powered vehicles registered in Poland increased from 30 to 287 during these years. In the same period, the total number of publicly available charging points increased from 1818 to 7271. However, in 2023, there were only two hydrogen refueling stations (there were no such stations in 2020) [

2]. By then, it is estimated that the number of electric vehicles will exceed 1.5 million, with the total stock of publicly available charging stations expected to reach 87,000—which is to enable alignment with the provisions of the AFIR Regulation [

3].

From a systemic perspective, the electric vehicle charging infrastructure consists of four elements [

3,

4]:

where:

—transport infrastructure for electric vehicles,

—a recharging pool consisting of one or more charging stations located in a specific place, which may include separate, adjacent parking spaces,

—recharging station, defined as a physical installation in a designated place, consisting of one or more charging points,

—recharging point, also called a charging station, a device that supplies electric vehicles with electricity. (A charging point may have one or more connectors,

—a connector that constitutes a physical interface between a fixed charging or refueling point and the vehicle through which the exchange of fuel or electricity is carried out.

The interpretation of individual SIT elements is defined in Regulation (EU) 2023/1804 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 September 2023 on the deployment of alternative fuels infrastructure, abbreviated as AFIR (Alternative Fuel Infrastructure Regulation) [

3]. AFIR has been in force in the European Union since 13 April 2024, and it standardized the terminology for transport infrastructure adapted to the needs of low- and zero-emission vehicles. The regulation regulated the development of alternative fuels infrastructure along the TEN-T network until the end of 2025 and 2030. It should be noted that prior to the introduction of AFIR, the development of alternative fuels infrastructure was implemented freely by individual European Union countries. This development could be observed in urban areas, where travel and transport of people and goods using electric cars outside urban areas was restricted. Previous actions assumed that electric vehicles would be used only for transport tasks performed in cities. The increased range of electric vehicles, which often exceeds 400–500 km, and even 600 km, is activating transport operations outside urban areas. The proposed development of alternative fuel infrastructure under AFIR addresses the challenges of electromobility outside urban areas.

Given the above, it should be noted that the location of electric vehicle charging points is crucial for broadly understood electromobility. In principle, the charging area itself, or the charging station, can be considered secondary, as the vehicle user is still interested in the charging point. From a technological perspective, the charging point is equipped with a specialized connector enabling the connection of an electric vehicle to an external energy source. When considering the location of vehicle charging points, it should be noted that it depends on a set of factors important to vehicle and road users, operators of point-based and linear transport infrastructure, transport, forwarding, and logistics companies, and companies implementing investments in the construction of alternative fuel infrastructure. However, every user, operator, entrepreneur, or company seeks information about the scope and course of development and what influences this development.

Considering the important role of electric vehicle charging points in the development of electromobility, research was conducted to estimate the impact of EV charging points on the implementation of electromobility in a given area. Considering the complexity of the issue, spatial interpolation was applied in the study to determine the location and influence of electric vehicle charging points along road networks distributed across the territory of Poland. This approach is innovative and has not yet been implemented at the stage of analysis and development of alternative fuel infrastructure along the TEN-T network. The research process employed spatial interpolation of electric vehicle charging points using GIS tools. The research was conducted across 16 voivodeships in Poland.

2. Research Materials and Methods

Considering the specifics related to managing transport infrastructure in the form of electric vehicle charging points, it can be noted that it results, among other things, from the road network distributed in a given area and the traffic volume on individual roads. It is also worth noting that at every level of spatial development in the country, from local to provincial, national, or international, the idea of promoting charging points is consistent with the aspect of travel, or the broadly interpreted concept of electromobility. This also stems from the basic maxim that forms the foundation of the promotional structure, namely: “think globally and act locally”. This is primarily to popularize various forms of mobility, which include tourism related to the exploration of the natural environment and the integration of tourism with the local community, including the development of ecological travel behaviors within road transport [

5]. Such a focus creates opportunities to promote places, regions, and primarily transport systems, which have previously only been occasionally considered, not only by tourists but also by the transport industry.

When demonstrating the importance and role of the diffusion of transport route directionality in the context of electromobility, it is worth drawing on the theory of descriptive econometrics. Speaking of locations and directionality, which is the subject of the broadly understood development directionality in the context of road transport development, significant regularities can be observed that become apparent in mass processes. Considering each observation separately (e.g., an electric vehicle charging point), it is often governed by chance [

6]. Existing differences can be observed between individual electric vehicle charging points, which, on the one hand, are common to each location, but also exhibit certain differences that constitute a differentiating element, for example in terms of charging power, current type (AC or DC), and connector type [

7].

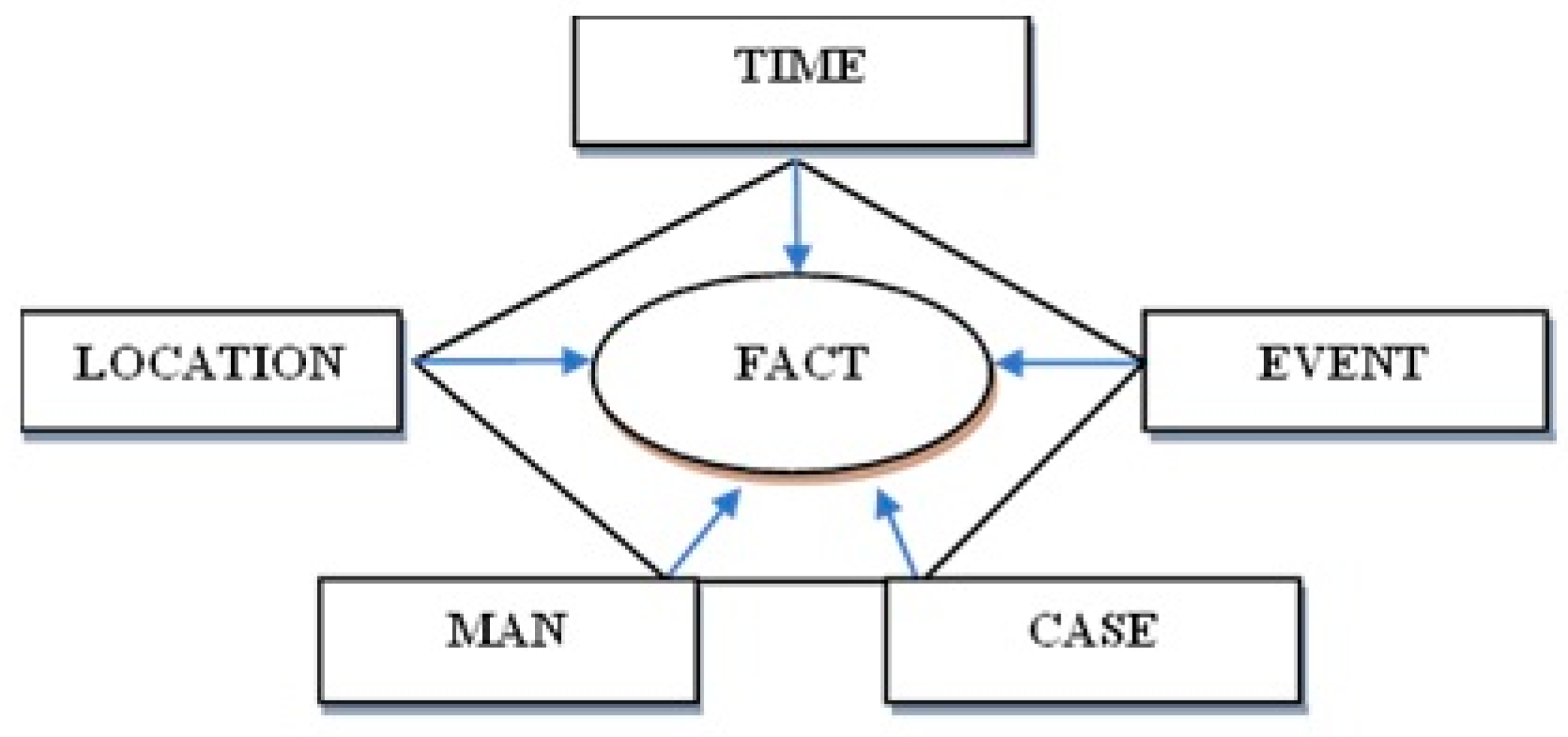

When considering the service points it can be assumed that in the econometric sense it is a fact for which the following principle can be used to define the factors describing it: “tempus, locus, homo, casus et fortuna regit factum” included in the pentagon of sources of driving forces in economics [

8] (

Figure 3).

Pentagon allows for the construction of a set of factors that influence the overall shape of electric vehicle charging points for electromobility. Its factor analysis, however, is classified as an econometric method. These methods show the influence of exogenous and endogenous variables on a specific loading point with an indication of the qualitative aspect. It is worth emphasizing that the presented case study is the basis for the development of this research, in which, due to locational orientations, it is worth considering the use of spatial autocorrelation, including geostatistical methods. Taking spatial interpolation into account is very useful in this case, given that data collection often involves only fragmentary data with relatively large gaps in geographic data. Geostatistical methods, in the analysis of electric vehicle charging points, are characterized by a high ability to estimate feature values in locations where data are missing [

9].

In order to demonstrate the spatial autocorrelation of electric vehicle charging points, the study considered it appropriate to use the hypothesis that the spatial autocorrelation of electric vehicle charging points is related to the road layout and traffic density gradient in a given area. Initial work included familiarization with the location of electric vehicle charging points in Poland and Europe. Based on this, the research goal was formulated: to estimate the impact of electric vehicle charging points on the implementation of electromobility in a given area.

The selected research area was a system of 16 voivodeships located across Poland. The research process involved spatial interpolation of electric vehicle charging points using GIS tools (ArcGIS Pro 3.0).

The impact of electric vehicle charging points on the implementation of electromobility was estimated in the following areas:

Estimation of the impact of electric vehicle charging points on the implementation of electromobility, taking into account the TEN-T,

Estimation of the impact of electric vehicle charging points on the implementation of electromobility in terms of transport tasks for industrial purposes,

Estimation of the impact of electric vehicle charging points on the implementation of electromobility in terms of transport tasks resulting from the location of logistics centers,

Estimation of the impact of electric vehicle charging points on the implementation of electromobility in terms of population movements in the area of tourism,

Estimation of the impact of electric vehicle charging points on the implementation of electromobility in terms of vehicle movements in the broadly understood area of defense.

For the purposes of conducting the research, the research process used was divided into two stages:

Stage 1—involved determining the general and specific locations of electric vehicle charging points across 16 voivodeships in Poland. Data was segregated into two areas: (1) general location and (2) specific location. The next step was to estimate electricity consumption at a given location, broken down by operator. As a result, the data was segregated by charging power at individual locations, taking into account the impact on the subregion. The research process was based on our own field and inventory research, literature research, databases of spatial information systems (GIS) divided into monitored areas, and an examination of planning documents and industry data. The research results were presented in tabular form and imported into GIS tools.

Stage 2—This involved the appropriate selection of research tools and the initial processing of spatial data in a GIS system, i.e., geostatistical analysis. The study utilized the spline method with barriers, which additionally excluded from interpolation areas (locations) inactive in terms of the presence of electric vehicle charging points. The study favored the use of the spline with barriers method due to the implementation of a smooth surface, minimizing its overall curvature. The main reason for choosing this method was to achieve the smoothest possible surface, which passes precisely through entry points, i.e., electric vehicle charging points, while taking into account barriers such as geological faults, which can be identified using a numerical terrain model, the boundaries of water bodies, or other infrastructure elements in the environment that impose surface discontinuity. The spline with barriers tool utilizes the minimum curvature method, which is implemented using a unidirectional polygrid derived from an initial polygrid initialized with the average values of the input data, i.e., points with known charging point locations. This is repeated until the minimum curvature surface is achieved, resulting in the extraction of a smooth surface passing through the isolated points. At each level of mesh refinement, the mesh-based surface model is treated as a membrane, and at each node, a linear, iterative deformation operator is applied to obtain a surface approximation with minimal curvature, which takes into account both the input data about charging points, which constitute specific parameters assuming an area linked to a voivodeship, and the encoded discontinuities. The applied method fits a mathematical function to a specified number of nearest charging points, passing through isolated points determined during preliminary studies [

10,

11]. In the study, to obtain the greatest optimization of the spline with barriers method, ArcGIS software was used, which itself has an implemented algorithm (Hutchinson algorithm), capable of minimizing the time of estimating the spatial directionality of the development of charging points in the voivodeships.

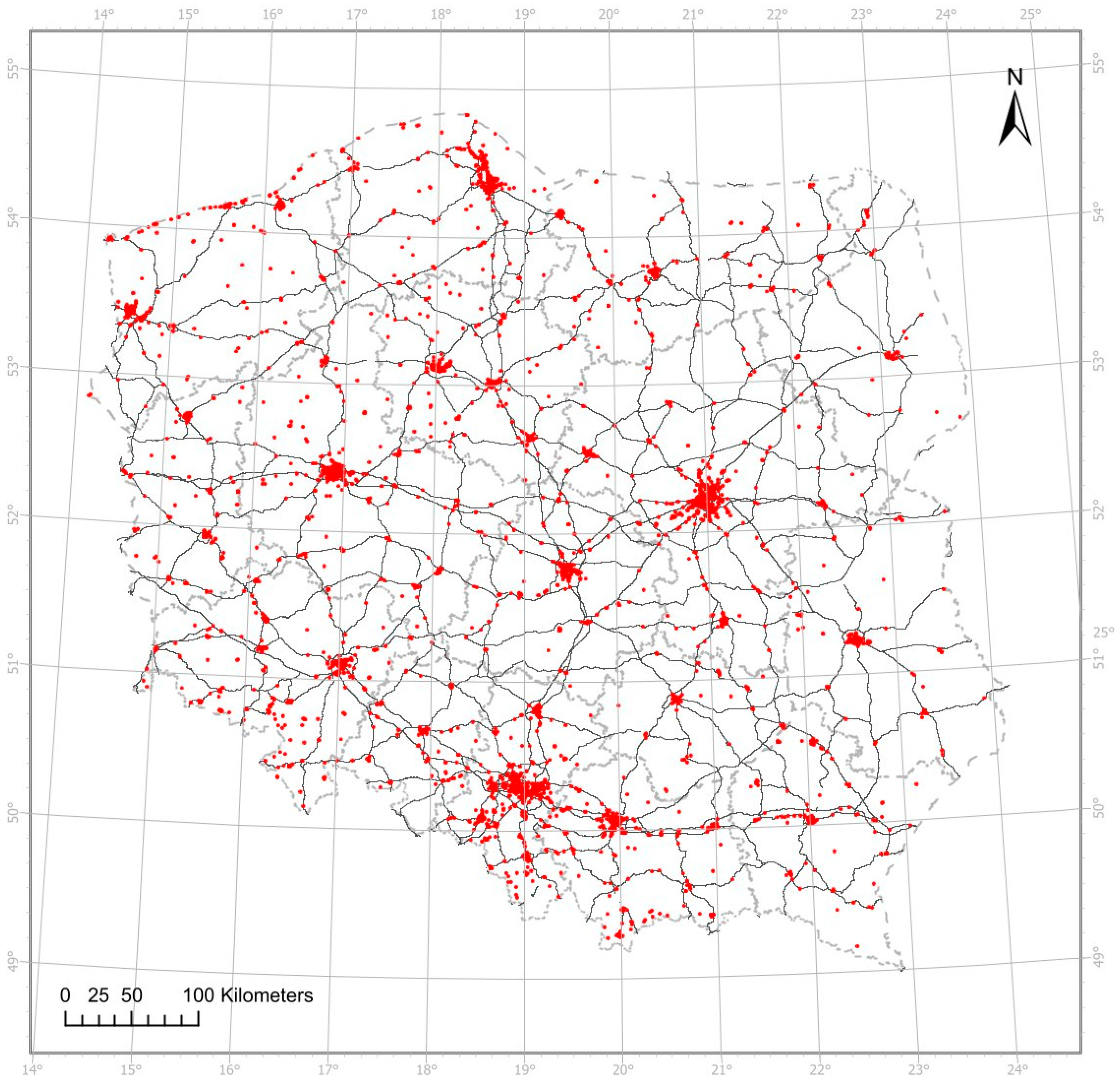

The work preceding the detailed analysis involved literature studies and spatial data related to the geolocation of electric vehicle charging points in Poland (

Figure 4). Detailed analyses covered areas based on the criterion of dividing Poland into 16 voivodeships. The synthesis was conducted separately for each voivodeship.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Factors Determining Electromobility Development

Research on the development of electromobility is being conducted across multiple dimensions. These include, on the one hand, the technologies used in transport vehicles and the infrastructure enabling their charging, and, on the other hand, analyses of the economic and social impacts of the large-scale deployment of EVs and their contribution to the execution of transport policies. One of the key objectives of these policies, at both national and European levels, is to address and reduce the environmental footprint of the transport sector, by promoting the creation of a low-emission, safe, and environmentally friendly transport system.

One of the key approaches to achieving the goals outlined in transport policies is the large-scale uptake of EVs. As a core element of the energy transition, the growth of electromobility supports the decarbonization of transport and significantly reduces CO

2, NO

x, and particulate emissions in urban areas [

12,

13]. When combined with renewable energy sources and intelligent traffic management systems, EVs can substantially enhance the energy efficiency of transport networks, while simultaneously reducing noise and reliance on carbon-based energy sources [

14,

15]. The integration of EVs with public transport and logistics distribution systems also plays a crucial role, supporting the creation of coherent and sustainable mobility chains [

16,

17]. The rising adoption of EVs is driven by a multifaceted interaction among technological, economic, social, environmental, political, and infrastructural determinants [

18,

19].

3.1.1. Technological Factors

Many studies indicate that battery capacity (which determines vehicle range) and energy efficiency are critical factors influencing the attractiveness and market penetration of EVs [

20,

21]. Numerous analyses have examined the relationships between vehicle range and battery capacity [

22], air-conditioning or heating usage [

23], driving behavior [

24], and weather conditions [

25]. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) studies show that as batteries age, the energy efficiency of EVs declines, resulting in adverse environmental impacts [

26,

27]. Advances in lithium-ion cell design have increased energy density and reduced charging times, thus improving the competitiveness of EVs [

28].

A key research challenge remains battery degradation, an inherent process in EV operation that causes a gradual loss of capacity and power, ultimately affecting driving range, safety, and operating costs [

29,

30]. Numerous studies have identified factors accelerating this process, including Depth of Discharge (DoD), operating temperature, charging current, and usage patterns [

31,

32,

33]. Battery Management Systems (BMS) serve an essential role in reducing adverse effects by supervising parameters such as the State of Charge (SoC), temperature, and internal resistance of cells, as well as optimizing charging and discharging cycles [

34,

35,

36]. Increasing attention has been directed toward the development of adaptive charging strategies that minimize cell degradation while maintaining acceptable charging times [

37]. Experimental studies further demonstrate that frequent fast charging significantly reduces the lifespan of lithium-ion batteries compared with slower charging modes [

38].

3.1.2. Economic Factors

From the perspective of electromobility development, economic factors determining consumer purchasing decisions and the overall profitability of EVs are equally crucial. The literature analysis indicates that the purchase price of EVs continues to represent a major barrier to their large-scale deployment [

39]. The high upfront price is largely attributed to the production costs of lithium-ion batteries, which may account for up to 40% of a vehicle’s total value [

40]. Nevertheless, a steady decline in the unit cost of batteries has been observed, representing a key driver in narrowing the price gap between EVs and internal combustion engines vehicles (ICEVs) [

41]. Another important issue concerns the environmental costs associated with the disposal or recycling of used batteries [

42].

The operating costs of EVs are closely linked to electricity prices, and their competitiveness relative to ICEVs must be evaluated in relation to diesel and gasoline fuel prices. Several studies suggest that EV operation is usually more economical than that of ICEVs, mainly due to lower energy and maintenance costs [

43,

44]. However, variations in electricity prices across countries can significantly affect EV profitability, making the analysis of operating costs a complex, location-dependent issue [

45].

The degradation of batteries constitutes an essential aspect in the assessment of EV economic efficiency, as it leads to reduced residual value and eventual battery replacement after several years of use. As indicated by Birkl [

30], a typical loss of at least 20% of battery capacity occurs after 8–10 years of operation [

30]. Battery replacement represents a major expense, considerably influencing the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) [

46]. Consequently, recent economic research increasingly focuses on developing predictive TCO models that incorporate battery degradation and fluctuations in energy prices, enabling more accurate assessments of the long-term competitiveness of EVs [

47].

A major tool promoting the advancement of electromobility is the implementation of incentive schemes designed to reduce both the purchase and operating costs of EVs. According to Hardman [

48], such policies serve a vital function in supporting the diffusion of low-emission technologies, especially in the initial period of market establishment and consumer adoption [

48]. The most common forms of support include direct purchase subsidies, tax breaks, exemptions from registration fees, financial support for charging infrastructure, and discounts on road and parking fees [

49]. Comparative analyses conducted across various countries show that a mix of direct subsidies and tax incentives is the most effective in stimulating EVs sales [

39,

50].

Recent studies increasingly highlight the need to adapt policy instruments to the maturity level of the electromobility market. In markets where EVs make up a notable share of new registrations—such as Norway and the Netherlands—indirect measures, including infrastructure investments, fleet regulations, and business-oriented incentives, have proven more effective [

51]. Conversely, in developing economies where economic barriers remain dominant, direct subsidies and investment support for charging infrastructure continue to play a decisive role [

39,

44].

Economic conditions for the implementation and operation of alternatively powered vehicles, including EVs, should be evaluated individually, taking into account not only the specific socio-economic circumstances characterizing each country but also the characteristics of specific vehicle types, models, and business applications. For example, Wróblewski [

52] presents a comparative assessment of the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) for conventional vehicles and those powered by alternative energy sources under various operating conditions in Poland [

52]. Similarly, Wasiak [

53] assessed the profitability of deploying heavy-duty alternatively powered vehicles in international freight transport, providing insights into their economic feasibility [

53].

3.1.3. Social Factors

The social determinants of electromobility development represent an important area of research that has been widely addressed in the literature. Increasing consumer environmental awareness and the perception of EVs as environmentally beneficial solutions are strongly correlated with a higher willingness to purchase them [

54]. However, sociological studies emphasize that positive attitudes toward electromobility do not always translate into actual purchasing behavior [

55].

Another significant aspect concerns the social acceptance of electromobility. Research indicates that higher levels of acceptance are typically observed among well-educated individuals residing in urban areas, where the benefits of electromobility—such as reduced noise and improved air quality—are more tangible [

56,

57]. Conversely, public skepticism is often linked to concerns regarding driving range, battery durability, and the availability of charging infrastructure [

58]. In this regard, informational and educational initiatives constitute a key component in shaping public awareness and acceptance, as they can mitigate cognitive barriers and enhance public confidence in emerging technologies [

56].

Socioeconomic disparities also constitute a key dimension of current research. Numerous studies demonstrate that individuals with higher income and educational attainment are more likely to be early adopters of EVs, raising important questions about the social equity and inclusiveness of policies promoting electromobility [

59].

3.1.4. Enviromental Factors

The primary motivation for implementing EVs and other types of alternative propulsion systems lies in environmental protection, particularly in improving air quality. Although the environmental impact of EVs may vary depending on the technologies used to generate electricity, the prevailing view in the literature is that EVs are generally more environmentally sustainable than ICEVs [

14,

26]. LCA studies show that the environmental benefits of EV adoption are especially evident in countries where renewable sources account for a major part of electricity generation [

27]. Moreover, EVs exhibit much higher energy efficiency: while the efficiency of electric motors exceeds 77% in converting grid electricity into mechanical energy at the wheels, internal combustion engines achieve merely 12–30% efficiency in converting fuel energy into movement [

60]. Consequently, even when electricity is produced from fossil fuels, EVs continue to generate lower total emissions than ICEVs. An additional environmental advantage is reduced noise levels, which is particularly relevant in densely populated urban areas [

61].

Given these environmental benefits, the deployment of EVs is especially important in highly urbanized regions. A key policy instrument in this context is the establishment of clean transport zones, with decisions on their implementation typically based on comprehensive traffic modeling and environmental analyses [

62,

63]. Beyond clean transport zones, sustainable urban logistics also plays a vital role in achieving low-emission mobility. Rationalizing freight deliveries while considering environmental factors, particularly through the electrification of last-mile delivery fleets, can substantially reduce external transport costs and support the achievement of broader objectives related to sustainable development [

64].

3.1.5. Infrastructure Factors

In the area of infrastructure, one of the key determinants of electromobility development is the charging infrastructure, whose availability, spatial distribution, and technical characteristics directly influence the pace of EVs adoption. The literature highlights that the fast growth in the number of EVs substantially affects the load on power grids, and inadequate infrastructure planning may result in local overloads and voltage drops [

65]. Consequently, one of the primary research directions has concerned the integration of electric vehicle charging infrastructure (EVCI) into the power system, particularly through the implementation of demand-responsive and smart grid technologies [

45].

When analyzing the benefits of implementing electric vehicle charging points, it should be recognized that electric cars are becoming increasingly practical with each generation. As the range of battery-based technology increases, so too does charging power and, of course, range. This allows for shorter charging times, which improves comfort and increases the attractiveness of vehicles. This leads to an increase in the number of buyers, and therefore vehicle users, who, when considering vehicle purchases, consider the distance traveled on a single charge. Therefore, considering the financial aspect, it is related to the average maximum charging power, which was 86 kW in 2023.

In terms of usability and financial benefits, it should be recognized that numerous privileges for electric car users create opportunities and stimulate the market for the implementation of new charging points. Electric car users, taking advantage of numerous privileges, such as exemption from parking fees or exemption from parking fees in paid parking zones, consider purchasing an electric vehicle, but first check the operating area with other fueling options. This means that electric vehicle owners do not have to worry about searching for parking meters, calculating parking times or paying fines for not having a parking ticket, but they do make other calculations, such as the availability of charging points in their household area.

A significant practical challenge lies in ensuring sufficient accessibility of electric vehicle charging infrastructure (EVCI), especially fast-charging stations, which reduce charging times and extend effective driving periods. As emphasized by several studies [

39,

48], the availability and reliability of charging infrastructure remain among the most influential factors shaping consumer purchasing decisions. This issue is closely linked to the optimization of charging station locations, which has become a central topic in contemporary electromobility research.

This is essentially related to the classification and implementation of stations with characteristics of slow (up to 22 kW, fast (50 kW) and ultra-fast, meeting the 100–350 kW criterion. Optimization is therefore related to requirements, such as diagnosing the appropriate converter in a car or the ability to recharge on a standard route from home to work. This fact influences the issue of distribution needs, which include low power demand. With AC power, stations require a power supply of up to 22 kW, which is standard for many buildings, while in the case of DC stations, distribution depends on very high power demand. They require access to a very high-capacity power grid, often from the distribution network or transformers. It is crucial that energy storage facilities function as voltage stabilizers and mitigate peak power demand, especially during peak hours, and also incorporate an energy management element to control power flow and prevent grid overloads.

3.2. Methods for Determining the Location of EV Charging Stations

As previously mentioned, EVCI is a fundamental component of the electromobility ecosystem. At the same time, determining the location of charging stations is a complex, multidimensional research problem that requires consideration of technological, economic, and social issues, as well as constraints related to the power grid and spatial order.

The literature identifies several main methodological approaches to EVCI location planning, which differ in analytical techniques and in the way they incorporate spatial, energy, and socioeconomic variables. Given the still limited number of charging stations, the siting of new facilities must be carried out carefully to ensure a coherent and efficiently distributed network within a defined planning horizon. The factors most frequently considered in location analysis include charging demand, local energy consumption, population density, and the spatial distribution of existing stations [

66,

67].

Among the most widely used approaches are Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) methods, optimization models, GIS-based approaches, and clustering techniques [

68]. MCDM methods are particularly useful when balancing multiple, often conflicting criteria, as they allow simultaneous consideration of economic, technical, environmental, and social dimensions. Among the most recognized and widely applied MCDM approaches is the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), which enables the prioritization of decision criteria through pairwise comparisons. Karolemeas [

69] developed a spatial decision-making model for charging station siting based on AHP, using it to assign weights to criteria such as traffic volume, parking availability, and proximity to transport hubs [

69]. Another, quite common approach is the technique of preference order by specific similarity to the ideal solution (TOPSIS), which determines the performance of alternatives by comparing their relative closeness to the ideal solution and distance from the anti-ideal one. Zhao [

70] used TOPSIS to analyze, evaluate, and rank specific charging station locations, thus enabling structured prioritization of the best locations [

70].

The second group of methods comprises optimization models, which aim to identify charging station locations that minimize investment costs or maximize the availability and accessibility of charging services. These models typically incorporate both technical and spatial constraints. Classical approaches, such as the location set covering problem (LSCP) and the p-median problem (PMP), are frequently applied to optimize the placement of charging stations so as to ensure comprehensive coverage with a minimal number of facilities. A representative example is the study by Frade [

71], which applied these methods to determine optimal station locations in the Lisbon metropolitan area [

71].

In more recent research, various heuristic and metaheuristic algorithms have been employed to solve large-scale and computationally complex siting problems. Among these, genetic algorithms [

72], ant colony optimization [

73], particle swarm optimizatiom [

74], and hybrid methods, such as the combination of genetic algorithm with simulated annealing [

75] are particularly notable. These approaches enable the efficient exploration of near-optimal solutions, offering flexibility and robustness in the presence of multiple constraints and nonlinear relationships.

Another important methodological category is based on Geographic Information Systems (GIS), which support the integration of spatial information concerning land use, road infrastructure, grid connectivity, and population characteristics. Cai [

76] developed the GIS-AHP method, combining spatial analysis with hierarchical evaluation of decision criteria to analyze and select the optimal spatial distribution of charging facilities within the city of Beijing [

76]. Likewise, Soczówka [

77] introduced a GIS-based approach for selecting optimal EV charging station sites from a local government perspective, using publicly available spatial data. The analyzed area was divided into hexagonal grid cells, for which siting potential was calculated based on population density, existing infrastructure, and road network configuration [

77]. In their study, Dong [

78] employed an activity-based model supported by GPS trajectory data to identify optimal charging station sites corresponding to drivers’ frequent destinations, including workplaces and commercial hubs [

78]. Due to their ability to integrate spatial, behavioral, and energy-related data, GIS-based methods currently represent one of the most dynamically evolving tools in electromobility planning.

The final group of methods encompasses clustering techniques, which are used to group demand points or traffic-generating areas. Abdullahi [

67] proposed a clustering-based approach that minimizes the distance between charging stations and high-demand zones while accounting for energy efficiency and avoiding redundant station placement in low-activity areas [

67]. Alternatively, Momtazpour [

79] introduced the concept of coordinated clustering to support charging infrastructure planning within the framework of smart energy grids. Their model analyzes the interdependencies among urban, energy, and social systems, facilitating the sustainable design of charging infrastructure in urban environments [

79].

Research on EVCI location strategies also includes assessments of practical implementations and best-practice recommendations [

80]. Furthermore, studies have examined national infrastructure planning frameworks and regulatory requirements for alternatively powered vehicle infrastructure, as illustrated by cases from Italy [

81,

82] and Poland [

83,

84].

In summary, the diversity of methodological approaches used to determine EVCI locations reflects the need to address multiple dimensions: economic, technical, spatial, and social. An emerging trend in recent studies is the integration of different approaches, such as combining MCDM methods with GIS analysis or clustering, to obtain more comprehensive and applicable results that effectively support sustainable electromobility planning.

3.3. Legal Aspects

Within the domain of electromobility, a broad set of legal instruments operate at the international, national, and local levels. Various mechanisms have been introduced not only to stimulate the development of electromobility but also, more precisely, to ensure equal market conditions for EVs compared with conventional ones. These include measures such as increasing the permissible gross vehicle weight of EVs to account for battery mass, introducing tax incentives (e.g., higher depreciation limits for passenger cars with alternative propulsion systems), and implementing subsidy programs supporting the purchase of such vehicles. In addition, legal provisions require both public and private entities to participate in the transition toward electromobility (for instance, by mandating that manufacturers, local governments, and companies with their own fleets gradually introduce alternatively powered vehicles).

In the context of the research problem addressed herein, the most relevant legislative measures are those that define the principles for developing charging and refueling networks for alternatively powered transport modes. Within the European Union, the rules governing the deployment of charging infrastructure for electric vehicles and hydrogen or other alternative fuels refueling stations are defined primarily in the Regulation on Alternative Fuels Infrastructure. Adopted on 13 April 2024, the Regulation replaced Directive 2014/94/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014, on the deployment of alternative fuels infrastructure, which establishes a harmonized and binding framework for the deployment of electromobility infrastructure in all EU countries.

The AFIR regulation introduced a requirement for each Member State to ensure that by the end of each year (starting from 2024) publicly available charging stations provide a total power output of at least (It is possible to obtain an exemption from these requirements when the share of light-duty battery EVs in the total fleet of light-duty vehicles registered within a given Member State reaches at least 15%.) [

3]:

Moreover, the AFIR establishes detailed requirements regarding the allocation and deployment of electric vehicle charging stations along the TEN-T, in public parking areas, and within urban nodes (see

Table 1), along with the deployment of hydrogen refueling infrastructure (see

Table 2). The regulation also introduces an obligation to ensure transparent and non-discriminatory pricing mechanisms for charging services, allowing fees to be collected based on both energy consumption and charging duration.

In Poland, the primary legal act governing alternative fuel vehicles and the establishment of their charging and refuelling infrastructure is the Act of 11 January 2018 on Electromobility and Alternative Fuels [

85]. Pursuant to this Act, the Minister responsible for climate affairs is tasked with developing a national framework for developing alternative fuel infrastructure. This strategy includes, among other elements, an assessment of the current state and the expected evolution of the alternative fuels market, alongside the definition of national objectives regarding the number and distribution of publicly accessible charging and refuelling points. These targets are consistent with the provisions established under the AFIR Regulation [

85] (

Figure 5).

Moreover, with regard to the development of charging points, the Act [

85] obliges the General Directorate for National Roads and Motorways to develop a plan for the installation of publicly accessible charging and natural gas refuelling stations along the TEN-T core network roads under its jurisdiction, covering a period of at least five years. Although the statutory provision does not explicitly mandate planning for the comprehensive network, the General Directorate for National Roads and Motorways also includes this network in its planning activities to ensure the coherence and continuity of national charging infrastructure development (Available online:

https://www.gov.pl/web/gddkia/vi-plan-lokalizacji-ogolnodostepnych-stacji-ladowania-stacji-gazu-ziemnego-oraz-punktow-tankowania-wodoru (accessed on 12 September 2025).

4. Spatial Interpolation of Electric Vehicle Charging Points in Poland—A Case Study

The spatial interpolation of electric vehicle charging points should always be considered as a factor influencing their location. Location is a significant external factor that combines various variables, such as proximity to the road network, border crossings, and transportation hubs, as well as logistics hubs and overall logistical accessibility. However, when analyzing an electric vehicle charging point itself, or their concentration in terms of investment profitability, all preliminary analyses begin with examining vehicle traffic volume, mobility resulting from basic and secondary life functions of the population (e.g., travel to work, school, shopping, etc.), as well as the structure of the supply chain in a given area. This process stems from strengthening knowledge about transportation behavior and the performed transport tasks from an economic perspective. Vehicle traffic volume is a determinant of the creation of new charging points, which are associated with generating income from the location, which constitutes nothing more than location rent.

The density of charging points for electric vehicles was determined by generating polygon centroids of data from the representation of EV charging point locations in Poland (

Figure 5). Based on the obtained layer, a heatmap interpolation was performed, based on the proximity and density of specific points with similar characteristics, which can be used in the case of maximum load of individual points. At the verification stage, the obtained results were checked using the Inverse Distance Weighting method, which takes into account the weighted averages of values measured at points near the interpolation points as the basis for interpolation [

86]. Of course, in terms of interply analysis itself, it’s worth noting the issue of uncertainty, which refers to the error or uncertainty inherent in estimating values for unknown locations, in this case charging points. In this case, this uncertainty stems from data availability and the relatively large study area—the entire country. It’s also worth noting that significant spatial variability depends on factors such as mountainous terrain. An illustration of the implemented process in Poland is presented in

Figure 6.

Geostatistical analysis shows that the concentration of electric vehicle charging points is related to the direction of the Trans-European Transport Network TEN-T, which includes: road, rail, air, sea and river routes that constitute the most important connections from the point of view of the development of the European Union, as well as point infrastructure elements in the form of seaports, airports, inland waterways and road-rail terminals [

87].

The meridional directionality of transport associated with the operation of the TEN-T network assumes ensuring full territorial cohesion of the European Union and improving the free movement of people and cargo. Undoubtedly, connecting the network itself with its hubs—seaports—is a crucial issue. Efficient use of sea routes has led to the prioritization of intermodal transport, which currently plays a paramount role. Economics related to rising fuel prices, including deteriorating road quality, and annually increasing traffic volumes have led to waterborne transport becoming the most competitive mode of transport [

88].

The density of charging points depends on the specific road network in a given area. Given this, it is difficult to determine which region determines the desired directionality, which road is key for development. The relatively large dispersion of charging points indicates that electromobility in Poland is a diverse, even heterogeneous, market that is in a phase of continuous development. However, changes occurring in the context of globalization, reflecting the geopolitical crisis, are influencing the polarization of electromobility’s development direction. An example of this is the author’s assumption that the development direction of electromobility in the west-east direction (considering Poland) is influenced by increased vehicle traffic in the North Sea-Black Sea and North Sea-Aegean Sea directions. It is already noticeable that nodal points have emerged, from which the flow of cargo originates or where unloading is designated. On the western side, the transshipment hub will likely be the largest port in the Netherlands, Rotterdam, which constitutes the largest metropolitan area in Europe. On the eastern side, the Polish border points will be Korczowa-Krakowiec, Medyka-Szeginie, and Hrebenne-Rawa Ruska, as well as the city of Lviv, which serves as a road junction with branches to the Black Sea and the Aegean Sea. Undoubtedly, the most important role currently played by the port of Rotterdam is that, in addition to its essential functions of handling the enormous cargo that floods Europe, the port also plays a crucial role in European security, considering its military function.

Considering the geostatistical analysis presented in

Figure 6, it can be seen that traffic in the aforementioned directions favors the emergence of new charging points for electric vehicles. These routes are not only important sections of European transport corridors, but also significant directions that demonstrate the intensity of population movement, for example, for tourism, or for ensuring basic living functions such as commuting to work.

It’s worth noting, however, that despite significant progress in electromobility in European Union countries and the implementation of the requirements of the European Union Regulation on Alternative Fuels Infrastructure, which mandates the appropriate deployment of charging stations and charging points, there are no specific examples of countries that meet these criteria. The Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) is the only framework for demonstrating the electromobility objectives, namely the implementation of stations every 60 km. The deadline for completing this work was agreed upon by the member states, with full implementation by 2030.

It is therefore crucial to examine the impact of these factors on the development of electromobility within a narrow administrative area, where the electromobility core, i.e., the point with the highest electromobility intensity, is typically observed. To this end, the study employs kernel estimation, which allows for the spatial autocorrelation of the distribution of electric vehicle charging points to be taken into account.

The term contour kernel is not a standard approach to interpolative GIS analyses, unlike kriging techniques. However, due to its specific advantages, such as spatial filtering, which incorporates the analysis of geographic data to refine the research parameter and identify the central pixel, it was advisable to incorporate it in this study.

Its advantages are demonstrated by its use in Kernel Density Estimation, where the Gaussian kernel results from estimating the density of a given phenomenon in geographic space based on a set of points with a specific structure, or in Support Vector Machines methods, where kernel functions are used to map higher-dimensional data, facilitating classification or regression. Therefore, in the context of electromobility, kernel estimation seems to be an apt way to demonstrate electromobility in spatial zones such as Polish voivodeships.

The study utilized a unique algorithm to determine the default search radius, which was used to determine the average center of the entry points, or charging points, constituting the measurement population. Next, the distance from the weighted average center was calculated for all measurement points for a given voivodeship separately. The median of these distances was then determined, which was used to estimate the weighted standard distance.

Nuclear Estimation of Electric Vehicle Charging Points

Kernel estimation is one of the most advantageous tools in geostatistics, the aim of which is to model a usually smooth surface, where the representing density depends on the concentration of points in a specific region [

89]. The kernel density estimator itself is described as follows:

where:

—random sample size,

—dimension of space (range of influence of electric vehicle charging points),

—smoothing parameter (positive real number),

—function that meets the conditions:

The density function depends on the appropriate distance parameter, which becomes almost completely flattened as the distance increases. When estimating the concentration of charging points assigned to a specific area, each measurement object is replaced by a specific value, which is calculated using the probability density function. Then, the values of this function are added to obtain a cumulative surface or a continuous field with a specific density [

90]. The value of the smoothing parameter itself has a key impact on the significance of the kernel estimator. In a situation where there are very few charging points, a large number of extreme locations become visible, which can consequently lead to so-called spatial blurring. Consequently, such orientations cannot be perceived as truly clustered points as dominant. It is worth noting that excessively high values of the h parameter can result in excessive smoothing of the estimator, which in turn leads to blurring of the studied feature of the given distribution [

91]. This is essentially confirmed by the results of the spatial analysis of electric vehicle charging points by voivodeships in Poland, analyzed in this study.

Taking into account the results of recorded observations regarding the location of electric vehicle charging points in 16 voivodeships, random samples with a fixed number of points were selected. Based on the estimation results, the dependence of the density function estimator on the sample size and the smoothing parameter value was determined. This article categorizes electric vehicle charging points into locations serving industrial, logistics, tourism, and defense functions. Safety requirements, including power and current type, were considered the primary differentiation criteria. This is consistent with the basic classification of charging points, adopting the IEC 61851 [

92] and IEC 62196 [

93] standards, which define four charging systems for electric vehicles. The study determined that publicly accessible stations, subject to detailed legal regulations regarding labeling and interoperability, would be used for analysis. Private and semi-private locations were not included in the study due to limited data availability. Kernel estimation of the density function of electric vehicle charging point density, based on a specific sample in a given voivodeship, revealed a unimodal trend with concentration in different parts of the voivodeship. Interpolated heat maps depicting the density of charging points indicate significant spatial variability, which required establishing a certain accuracy of the classification. The analysis determined that heat accumulation (estimation kernel) in the voivodeships is not located in the central part of the voivodeship, and therefore their impact on space will differ significantly. On this basis, a grouping into three impacts on the given environment was adopted:

centrifugal influence, when the core is very close to the center of the voivodeship—at the voivodeship centroid,

peripheral influence, when the core is located on the outskirts of the voivodeship—but not on the voivodeship border,

extremely peripheral influence, when the core is located exactly on the voivodeship border.

Analyzing the spatial autocorrelation of charging points, it can be concluded that in the case of points classified as centrifugal, the main cause is the location of the main leading city in the center of the voivodeship. This is the case in the West Pomeranian Voivodeship (

Figure 7a), where the key city is Szczecin, from which the directionality of electric vehicle charging points radiates. The concentration of charging points in the Szczecin area also results from the operation of the port and the related location of many maritime services. This aspect definitely influences the overall development of electromobility in this subregion. Similarly, in the Małopolska Voivodeship (

Figure 7b), where the key city of Kraków, identified as a logistics hub, has a huge impact on the mechanism for the creation of subsequent charging points. This main nodal point, which connects the transport sphere, not only in economic and logistical terms, but also in terms of population movement for recreation, is a driving force in the development of electromobility. The above-average increase in the number of electric vehicle users is visible during holidays in Poland, where mountain recreation almost slows down traffic on the main transport routes, which significantly affects the significant increase in power consumption at charging points.

In the case of the Podlaskie (

Figure 7c) and Opole (

Figure 7d) voivodeships, the main target locations for charging points are dynamically developing centers in the voivodeship. In Podlaskie, this will be the Białystok region and the border region of Sokółka, where vehicle traffic is related to trade, but also to tourist traffic to Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. In the case of Opole voivodeship, the concentration of charging points will be related to the border region, i.e., the Głubczyce and Opole-Brzeg regions. There, in addition to increased traffic related to the exchange of goods, increased military movement can be observed related to the protection of NATO’s eastern flank.

It would seem that a similar pattern should occur in the group of voivodeships classified as having a peripheral impact. However, the apparent dominance of voivodeship cities in the electromobility phenomenon is sometimes displaced by towns or areas through which important communication routes run, crucial for the transport of people and cargo. An example of this thesis is the Pomeranian Voivodeship, associated with the operation of the important Gdynia-Gdańsk port complex (

Figure 8a). The Łódź Voivodeship also belongs to the group of voivodeships with their cores located in voivodeship capitals (

Figure 8b). The city of Łódź is closely linked to the directionality of the A1 motorways towards Gdańsk and the A2 towards Poznań. Sometimes, however, the location of charging points does not result from the size of the leading city, but is linked to communication hubs and goods storage, as in the case of the Central European Logistics Hub—the largest warehouse in Poland.

Another example of this is the Silesian Voivodeship, which is itself a rapidly developing metropolitan center and serves as a transportation hub, but the core of charging point saturation occurs on the voivodeship’s border, primarily due to the Silesian-Kraków Industrial District (

Figure 8c). Another interesting example is the Masovian Voivodeship, with Warsaw as its leading city. It would seem that the country’s capital is the most developed in terms of the number of charging stations, but the highest saturation is observed on the voivodeship’s northern border, where a significant increase in company formation is observed, and a rather strong connection can be observed with Gdańsk, which demonstrates intermodality in cargo movement thanks to the dynamically operating seaports of Gdynia-Gdańsk.

Furthermore, it can be noted that a significant portion of central Poland is influenced by the operation of the Gdańsk and Bydgoszcz-Toruń Industrial Districts (

Figure 8d). The group of voivodeships with a peripheral impact on their surroundings is completed by the Podkarpackie Voivodeship, which is developing most towards the north-west (

Figure 8e). This is mainly due to the topography and the operation of the Bieszczady National Park, and in this region, industrial activity is the lowest. It was also noted that in areas with national parks, there are the fewest charging stations.

The third category comprises voivodeships that are influenced by the location of electric vehicle charging points located in other voivodeships or whose estimation kernels are located on voivodeship borders, e.g., the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship (

Figure 9a), the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship (

Figure 9c), and the Greater Poland Voivodeship (

Figure 9d). In the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship, the eastern point of gravity is Częstochowa, which is a significant element in Poland’s transport system, where mass cargo flows from north to south and onward to the Adriatic Basin countries. On the eastern side, the city of Rzeszów is visible, which, after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, became an important center for population movements, including humanitarian aid. In the case of the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, the direction of gravity is truly meridional. Here, one can even connect the cities of Grudziądz and, further on, Gdańsk with Kutno and Łódź, which define the flow of goods. It can also be observed that despite the relatively dynamically developing tourism in recent times, there are the fewest charging stations on the Toruń-Szczecin route.

An interesting case is the Lublin Voivodeship (

Figure 9b) and Lubuskie Voivodeship (

Figure 9e), which are not necessarily influenced by developing large cities, but by proximity to the border, which determines the establishment of electric vehicle charging points. In the case of the Lublin Voivodeship, the proximity of two important centers, Warsaw and Lublin, plays a significant role in the establishment of new charging points. Furthermore, due to population movements, including the provision of humanitarian aid to the Ukrainian population, a very high density of charging stations is visible. A similar situation can be observed in the Lubuskie Voivodeship. The development of charging points is dominated by latitudinal directionality. This is undoubtedly related to the very high volume of freight transport and the increased number of tourists traveling east-west and west-east. It’s also worth mentioning the constantly expanding warehouse park in Greater Poland, which is significantly contributing to the creation of new charging points to shorten the idle time of electric vehicles. A striking example of the extremely peripheral impact on the concentration of electric vehicle charging points in a voivodeship is the Greater Poland Voivodeship. A pull from three directions has been observed there: Berlin, Łódź, and Gdańsk. However, the highest concentration of charging stations is visible in the Łódź area, which serves nearly 20% of all warehouse space in Poland and is a place where the e-commerce industry significantly differs in terms of its momentum from other regions in the country.

Considering the concentration of charging points in the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship (

Figure 9g), it should be concluded that it is related to the flow of cargo and tourist traffic on the S-7 expressway connecting the Gdańsk and Warsaw metropolitan areas. The city of Olsztyn is not a developmental center for electromobility here, despite the large tourism potential associated with the Great Masurian Lakes area.

An interpolation analysis of charging points across Poland shows that issues related to electromobility development stem from population movement, primarily on high-volume routes. In the context of the predictive aspect related to electric car purchases, this can be considered a predictor of improved traffic on other routes, which were previously classified as low-volume but not related to people’s wealth. The propensity to invest, from an econometric perspective, indicates a gravitational pull in this direction. However, it should be remembered that in the context of the total cost of ownership of an electric vehicle, which is the basic criterion for the financial viability of vehicle selection, the increase in energy and electricity prices, which are currently highly volatile in Poland, is a significant factor. The costs of using a vehicle charged at home remain significantly lower than the costs of operating it outdoors, even when charging a zero-emission vehicle under the night-time tariff. When charging a car at home, depending on the tariff, the cost of driving 100 km in an electric vehicle ranges from 8 PLN to a maximum of 18 PLN, while refueling a comparable combustion engine vehicle costs around 50 PLN. With the above in mind, forecasts aimed at implementing new charging points are justified, especially in areas with low development potential, where the region is experiencing economic impoverishment, as is the case with the Great Masurian Lakes region.

5. Conclusions

It should be noted that kernel estimation is used in many different areas of human social activity [

94]. Examples of applications of this method include estimating the density and structure of community functioning in a given area, or broadly defined demographic phenomena. Very few studies address its application in spatial analyses in the area of electromobility, and in particular the location of electric vehicle charging points. The research results indicate that the implementation of spatial interpolation in electromobility analyses and the localization of charging points is a solution capable of significantly accelerating the analyzed processes. Modeling a surface representing the density of activities in the area of electromobility allows for the determination of interdependencies between the electric vehicle charging system, which in Poland is still in the development phase. The use of kernel estimation for the spatial analysis of electric vehicle charging points can also involve not only estimating density but also assessing the intensity and concentration of a given economic phenomenon related to passenger and freight transport. The analysis shows that the electromobility phenomenon in question, presented across 16 Polish voivodeships, is quite diverse. This was demonstrated by the presented spatial interpolation of electric vehicle charging points using GIS tools in each subregion associated with a given voivodeship. The research noted that estimating the impact of electric vehicle charging points on the implementation of electromobility, taking into account the TEN-T network, the functioning of industry in Poland, the location of logistics centers and hubs, as well as broadly understood tourist activity and the functioning of defense aspects, exists and is noticeable in every voivodeship. However, the collected data indicates that the main criterion for selecting the location of electric vehicle charging points is the road layout, and therefore the gradient of population and cargo movement in the longitudinal and latitudinal directions.

Taking into account the ecological aspect, it is worth noting that the implementation of charging points in undeveloped spaces will definitely influence the development of electromobility and will lead to radical changes in the green sphere. The report “T&E’s analysis of electric car lifecycle CO2 emissions” shows that a standard electric vehicle emits more than three times less carbon dioxide compared to a conventional combustion engine vehicle purchased around 2022. This approach leads to the conclusion that, over its entire lifecycle, an electric vehicle will emit 40% less CO2 per kilometer. These emissions will significantly decrease as the Polish energy mix becomes greener. This means that increasing the number of charging points in Poland will positively impact vehicle purchases, which in turn will lead to charging points paving a new, green direction for the development of electromobility in Poland. The development of electromobility therefore presents an opportunity to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions from road transport congestion, as well as from air pollution, and to drastically reduce noise levels.

Based on available data from the European Environment Agency, 44,500 people die prematurely in Poland each year due to air pollution. People, accounting for over 10% of cases across the European Union. The most harmful pollutant appears to be airborne particulate matter, which is present in the highest concentrations in the air and consistently exceeds the norm. Estimates indicate that long-term exposure to these particles shortens life by up to a year. Therefore, accepting this argument, it is worth taking steps and implementing charging stations and points to achieve a better educational effect, and therefore better direction in the development of the electromobility economy related to the production and use of new electric cars. This will reduce emissions of pollutants such as sulfur oxides, carbon monoxide, and nitrogen oxides. This is indicated by available data, according to which, over the entire life cycle of electric vehicles, they can reduce pollutant emissions per kilometer by 54% for nitrogen oxides, by 41% for sulfur dioxide, and by 74% for carbon monoxide.

Data published by the Central Statistical Office (GUS) show that the busiest road in Poland is the section of the A-2 motorway between Łódź and Warsaw. Depending on the time of day and location, the number of vehicles traveling between these cities is around 100,000 per day. Furthermore, it’s worth noting that this figure is due to the fact that no tolls apply on the Warsaw-Łódź route, which encourages free travel. Spatial analysis indicates that this area significantly deviates from the general trend of charging point location in Poland. A similar relationship between charging point location and road capacity can be observed on the A-4 motorway, where the Katowice Mikołowska-Katowice Murckowska section has nearly 110,000 vehicles traveling daily. On road no. 631, connecting Zielonka with Warsaw, the vehicle throughput is almost 50,000 vehicles per day, and on the Warsaw-Jeziorna route, approximately 40,000 vehicles pass by per day, which is 67% above the national average in terms of vehicle traffic for various purposes.

It’s worth noting that the Silesian Voivodeship appears to be the most congested, as illustrated in

Figure 9c. It’s estimated that approximately 22,000 vehicles pass through the entire voivodeship daily for various purposes. The least congested area, however, is the Masurian Voivodeship, with just under 7000 vehicles per day, which is 44% below the national average.