Abstract

Quantum batteries are quantum mechanical systems able to store and release energy in a controlled fashion. Among them, a special role is played by quantum structures defined as networks of two-level systems. In this context, it has recently been shown that the energy stored in free fermion quantum batteries is sensitive to the quantum phase diagram of the battery itself. This sensitivity is relevant for stabilizing the stored energy and designing optimal charging protocols. In this article, we explore universal charging behaviors of free fermion quantum batteries across quantum phase transitions. We first analyze a Dirac cone-like model to extract general features. Then, we verify our findings by means of two relevant lattice models, namely the Ising chain in a transverse field and the Haldane model.

1. Introduction

As witnessed by the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics, conceptual and technological advancements allow for macroscopic systems to show quantum behavior [1]. This fact offers an impressive range of possibilities, among which a special role is played by the development of quantum technologies [2]. In this context, the hope is that quantum systems will provide innovative solutions in a range of fields that spans from sensing to computing, through communication and simulation [3]. To advance, the field of quantum technology needs quantum building blocks with different functionalities. Among such building blocks, quantum batteries are gaining considerable attention, both from the theoretical and the experimental points of view [4,5,6]. They are quantum systems able to store energy and release it in the form of work at request [7]. They are currently the object of intense research since they are relevant from many perspectives. On one hand, it has been shown that they can show superextensive power charging; namely, they can charge faster and faster as the number of constituents in the battery is increased [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. On the other hand, it has been conjectured that having quantum energy sources can be useful in the control of quantum devices, thanks to a matching of energy and time scales [16,17,18]. Moreover, the inspection of quantum batteries shares intriguing intersections with fundamental issues in quantum thermodynamics of both closed and open quantum systems [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27], where it, for instance, led to the definition of the concept of ergotropy [28]. Such an important figure of merit quantifies the amount of work that can be extracted from a quantum system by means of a unitary operations [29,30,31,32,33,34].

At the practical level, quantum batteries can be classified into two large classes: batteries represented by systems with a small number of quantum degrees of freedom [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46], and batteries with a large number of quantum degrees of freedom [47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. While the first scenario allows for the (numerically) exact solution of complex problems, such as finding optimal charging regimes and Hamiltonian couplings [54,55,56,57,58], or for the consideration of the presence of dissipation to reservoirs [33,34,42,59,60,61,62,63], the second merges the complexity of many-body quantum physics with that of quantum thermodynamics, and exact results are more rare [64]. Still, large quantum batteries are relevant both because they can store more energy and because they can show the already mentioned superextensive charging power. In the context of large quantum batteries, many practical tools are provided by the theory of quantum quenches [65], recently developed for—among other reasons—understanding quantum thermalization or the lack thereof. In such a theory, a remarkable role is played by the presence of quantum phase transitions [66,67,68,69]. Indeed, quantum quenches across quantum phase transitions manifest intriguing phenomena such as dynamical quantum phase transitions [67,68,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78] and steady states with large deviations with respect to thermal states. It is hence natural to think that quantum phase transitions can play a role in the context of quantum battery charging as well [50,79,80].

This is indeed the case. For instance, the following scenario has been recently analyzed [51].

One considers a quantum battery with Hamiltonian given by a collection of free fermions with definite (quasi-)momentum, namely

Here, is the (quasi)-momentum, indicates the Brillouin zone, are free parameters, and is the Pauli matrix vector in the usual representation, respectively. Finally, , with , is the fermionic annihilation operator for a fermion in the quantum state labeled by and by the (quasi)-momentum . The battery is prepared, for time , in the ground state of its Hamiltonian. At time a parameter in the Hamiltonian is suddenly varied to induce a charging process. Such a charging lasts for a time , after which the system is governed again by the initial Hamiltonian . In other words, the evolution of the system for is controlled by the Hamiltonian given by

where encodes the quench performed to achieve the charging. What is finally inspected is the energy stored in the system for . While we refer to Ref. [51] for the details of the derivation, it is useful to state here the functional form of such quantity. It is given by

where

Here, and denote the dispersion relations of the Hamiltonian before the first quench and during the intermediate evolution, respectively. We consider large enough that the cosine term averages out and can be neglected. The reason why this approximation is physically justified is that, as shown in [50,51], the early-time oscillations that affect the stored energy as a function of decay due to the summation over k, allowing energy to reach a plateau that is stable with respect to temporal oscillations. Clearly, when either or—more drastically— is critical, i.e., when either Hamiltonian is tuned to a critical point associated with a quantum phase transition, the stored energy runs in a 0/0 form that can result in non-analytical dependencies of the energy stored with respect to the charging parameters. This fact hence marks the strong dependence of the stored energy on the quantum phase diagram [50].

In this work, we characterize the universal features that quantum phase transitions imprint onto the energy stored in quantum batteries whose working mechanism is the one just described and for which the quantum phase transition is described by a Dirac cone structure. We find that in one dimension the first derivative of the stored energy is discontinuous, while in two dimensions the second derivative diverges. We corroborate our finding by means of two relevant lattice models, namely the quantum Ising model in a transverse field [81] and the two-dimensional Haldane model [82,83,84,85,86]. We emphasize that our results apply to models whose Hamiltonians can be written in terms of non-interacting fermions and in which the quenched parameter drives the system through a linear Dirac-cone gap closing. Different scenarios, such as interacting systems or gap closings with non-linear dispersions, may exhibit different non-analytic scalings. However, whenever a system features a linear band touching and the quench pushes the post-quench Hamiltonian across that point, our analytic predictions hold universally, regardless of which microscopic parameter is actually quenched.

2. Dirac Models

The non-analytical behavior of the energy stored in the quantum battery comes from the vicinity of the gap closing point in the dispersion relation. Consequently, to understand its universal features, we consider the paradigmatic low-energy models for one- and two-dimensional non-interacting systems undergoing quantum phase transitions with a linear gap closing [66]. We hence adopt, as quantum battery Hamiltonians, the Hamiltonians (respectively, for one or two spatial dimensions)

where and . Here and label momentum in the x and y directions, respectively, and is the mass. The charging is implemented by quenching the mass from to . The system is critical when one of the two masses is zero. Moreover, since we deal with a low-energy expansion, we replace the discrete sum with an integral in k space—here restricted to a shell of radius around zero momentum. For systems described by the Hamiltonian of Equation (5), we can directly evaluate the function reported in Equation (4) in both one and two dimensions. In particular, by inserting the components of for the 1D case and of for the 2D case, one explicitly obtains

with . Putting it all together, for dimensions, we get

with

and is the Gamma function. In the following section we will discuss the non-analytic behavior of this dimensional integral.

As we reduce our study to the region around , focusing only on the singular part of Equation (7), we can simplify the integral by considering the limit as a valid approximation. The stored energy then becomes

Since the integrand is a rational function, there exist two functions and such that

with a polynomial in k and having a degree less than that of , so must be either constant or linear in k. We now evaluate the integral for general values of d and distinguish two cases based on its parity.

2.1. Odd Case:

By specifying the polynomial division in this case, we can observe that the integrand can be decomposed as

Here, remains regular, since its n-th derivative does not develop any singularities as approaches zero. To investigate singularities, we then have to study the rational term with constant in k. Integrals of this form can be solved in terms of an arctangent function; in particular

Substituting the form of R and recalling that , we have

and as approaches zero,

So, for odd values of d, the stored energy scales as , and this leads to a jump discontinuity in its th derivative at . To evaluate the magnitude of this jump, let us take the complete form of the stored energy, including its prefactor

Let us consider a quench between an initial value and a final value , with being a positive increment. By applying the chain rule for the d-th derivative

and since d is odd, then . The th derivative of the stored energy, with respect to , then becomes

which, evaluated for (), gives the magnitude of the jump

2.2. Even Case:

In this case, the integrand can be written as

Also, in this scenario, is regular, so we focus on the second term where is linear in k. Introducing the integral is

From Equation (19), we can observe that as approaches zero, the term that leads to a singularity is proportional to

Considering the same quench applied in the odd case, from to , applying the general Leibniz rule

we obtain after a straightforward calculation

from which we can observe that if , then and no singularities appear. However, if , then Equation (21) becomes

where

is the harmonic number. From Equation (22) the singularity is evident, since diverges as approaches . Therefore, in both scenarios the th derivative of the stored energy shows a singularity in the limit , but its nature is different in the two cases: for odd values of d the non-analyticity is given by a finite jump, while for even values of d we observe a logarithmic divergence. The explicit calculations for are shown in Appendixes Appendix A and Appendix B, respectively. We now provide one- and two-dimensional model examples in the full Brillouin zone to support the equations we derived and to address the numerical aspects of these singularities.

3. Lattice Models

In this section, we check our results on the basis of two lattice models, namely the quantum Ising chain in a transverse field and the Haldane model.

3.1. Ising Chain

As stated above, the quantum Ising chain in a transverse field [81] is the paradigmatic model for the study of quantum phase transitions. Its Hamiltonian reads as

Here, j enumerates the lattice sites of a chain with a total of N sites, are the Pauli matrices on the site j, and h is the external field. Periodic boundary conditions are imposed. The ground state diagram has two phases: a paramagnetic one, for applied transverse fields and a ferromagnetic one for . The transition between the two phases happens through a second-order quantum phase transition. A remarkable feature of the quantum Ising chain in a transverse field is that it is exactly solvable by means of a Wigner–Jordan transformation to fermions (followed by a Fourier expansion to exploit translational invariance and a Bogoliubov transformation for getting rid of the superconducting correlations). For the details we refer, for instance, to Ref. [64]. What we consider here is the quantum Ising chain in a transverse field as a quantum battery. As a charging protocol, we adopt, as usual, a double sudden quantum quench where a parameter is varied at , and at it is set back to its initial value. In particular, here we switch between the values and of the applied magnetic field. For the energy stored , one has, at long times,

Here, the dispersion relations are given by

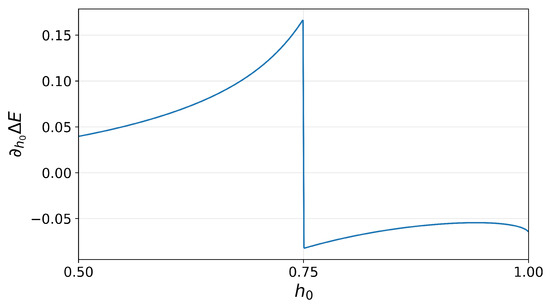

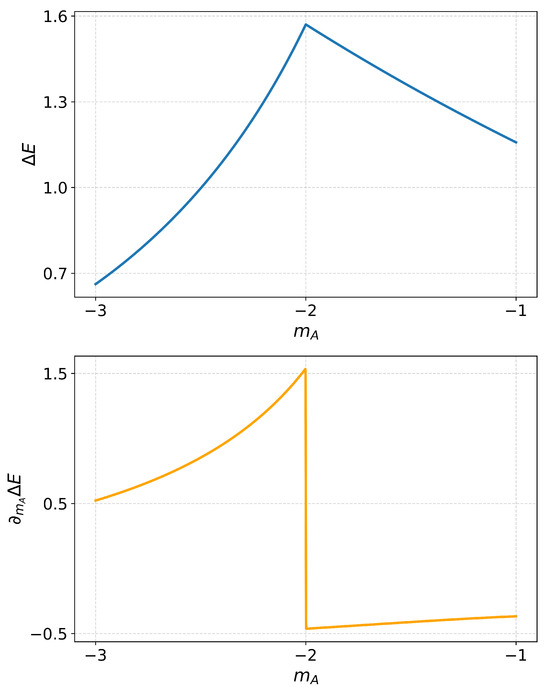

From the equation above, one can check that the first derivative of the energy stored is characterized by a finite jump in correspondence of the quantum phase transition . The magnitude of the jump is in accordance with the low-energy theory developed by concentrating on the physics at the cone described in the previous section. This fact is reported in Figure 1. There, the parameter used is , so that the reported jump of magnitude at is indeed consistent with the previous discussion (for more details, we refer to Equation (A6) in Appendix A).

Figure 1.

First derivative of the stored energy in the Ising chain with respect to the transverse field as a function of the initial magnetic field .

3.2. Haldane Model

An important two-dimensional model we can study in a similar way is the one introduced by F. D. M. Haldane in 1988 [82]. While this model is certainly paradigmatic in the topological material community, it might not be extremely common in terms of its energetic aspects, so we briefly review its properties before addressing the original results.

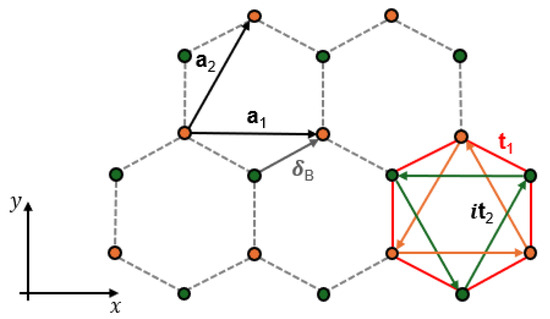

The Haldane model is a tight-binding model defined on a honeycomb lattice (which can be viewed as a triangular Bravais lattice with two atoms, type A and type B, per unit cell) that demonstrates how a system can exhibit a quantized Hall conductance without an external magnetic field. The key idea is that a quantized Hall response does not require a uniform magnetic field or Landau levels: it instead requires a nontrivial distribution of Berry curvature in momentum space and a resulting nonzero Chern number, i.e., the topological invariant characterizing the band structure of two-dimensional quantum Hall systems [87], for the occupied band. In the Haldane model this is achieved by engineering a local time-reversal-symmetry breaking on the lattice while keeping the net magnetic flux through each unit cell equal to zero. This produces an effective magnetic field in momentum space, concentrated around the gapped Dirac points, whose integral over the Brillouin zone yields the quantized Hall conductance [88,89,90,91]. A paradigmatic system that presents a honeycomb lattice is graphene [92]: here the carbon atoms interact through a nearest-neighbor hopping term with amplitude , and the corresponding Hamiltonian is characterized by gapless Dirac cones and massless quasiparticles. As stated above, the Haldane model extends this Hamiltonian by introducing both a next-nearest-neighbor hopping term with amplitude between sites on the same sublattice, where the complex phase associated with this hopping breaks time-reversal symmetry and introduces a mass term at the Dirac points (from now on we will set ), and a staggered on-site potential m, which takes opposite signs on the two sublattices and breaks inversion symmetry. These perturbations gap out the Dirac cones and give rise to a topologically nontrivial insulating phase characterized by a nonzero Chern number. We pick as primitive vectors and , with a being the Bravais lattice spacing. By placing the origin of the unit cell on the A sites, the basis vectors are and . In Figure 2 a sketch of the lattice is shown: for clarity, we have represented the lattice vectors and the hoppings in two different hexagons.

Figure 2.

Honeycomb lattice of the Haldane model. Green and orange dots denote the two sublattices A and B respectively.

In space, the Hamiltonian of the Haldane model, for our choice of , assumes the usual form , where

Note that a (k-dependent) energy shift has been neglected as it does not alter the results. The Dirac points are obtained from the condition that the off-diagonal part of the Bloch Hamiltonian vanishes, so we impose

Equivalently, one can write

where we used the three nearest-neighbor vectors

A vanishing sum of these three complex exponentials requires that their phases differ by ; this means that we have the following linear constraints:

and since and , these become

Writing in the reciprocal-lattice basis (with ) yields and . Therefore, one Dirac point is

and the other one is . Considering the primitive vectors we chose, the corresponding reciprocal vectors are

and the Dirac points assume the form

If we now evaluate at we obtain the two Dirac masses

These masses arise from the complex next-nearest-neighbor hopping, which breaks time-reversal symmetry and generates opposite signs at the two Dirac points. In particular, Equation (36) follows from our choice of ; more generally, any phase different from 0 and leads to masses of opposite sign and is responsible for the emergence of the Chern-insulating phase. Finally, it is worth noticing that by expanding the Hamiltonian around the Dirac points, one obtains the low-energy effective theory of the Haldane model, which reduces to a massless Dirac Hamiltonian. Concerning the QPTs, they occur when either or changes sign, i.e., when one of the two masses becomes zero. This condition yields the critical value of , namely

For simplicity, we fix so that we expect a QPT at . A compact and practical expression for the Chern number is

Therefore, we can distinguish the following three different phases according to the value of C:

- : topological phase with .

- : trivial phase with .

- : topological phase with .

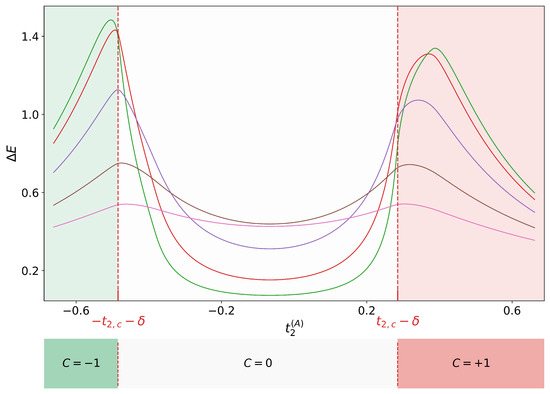

We now come to the Haldane model as a quantum battery. In analogy with the previous models, we perform a quench of the parameter of the form , with fixed , to study what happens at the critical points of the evolution Hamiltonian. Since the model is more complex than the Dirac one, our analysis takes into account different values of the nearest-neighbor hopping . The plots shown in the following figures highlight interesting results: First, as we observe in Figure 3, for the energy peaks always appear when the model is either in its topological phase or on the critical line, highlighting the distinct behavior associated with each phase of the system. As increases, we observe in the same plot that the curves gradually flatten, while the energy decreases and approaches zero. This latter trend can be qualitatively explained as follows: For large , the Haldane Hamiltonian reduces to the massless Dirac Hamiltonian describing graphene, since the dynamics are dominated by the nearest-neighbor hopping term. In this regime, quenching , which only enters the mass term, has a negligible effect on the Hamiltonian, and thus the system stores almost no energy, as if no quench had occurred.

Figure 3.

Energy stored in the Haldane model as a function of for (green), (red), (purple), (brown) and (pink) with fixed . The red dotted lines represent the critical values for the evolution Hamiltonian, while the different colors indicate the phase of the model according to the Chern number’s value, as represented under the plot: topological phase with (green region), topological phase with (red region) and trivial phase with (white region).

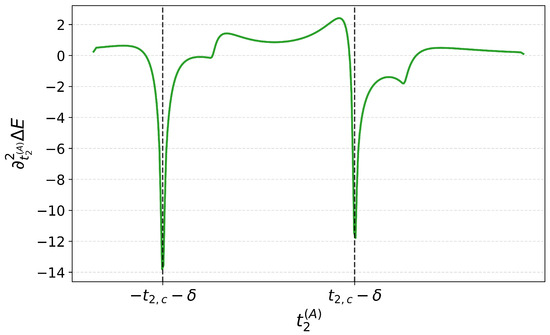

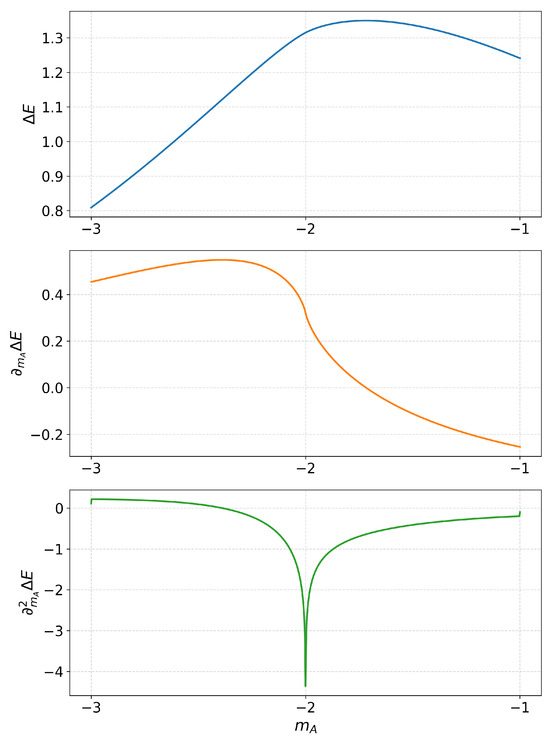

Let us now come to the comparison between the energy stored in the Haldane model quantum battery and the discussion of the previous section. The second derivative of the energy stored with respect to is shown in Figure 4. There, the values of the parameters are and , so that the logarithmic divergencies in correspondence of the quantum phase transitions are evident (for more details, we refer to Equation (A13) in Appendix B).

Figure 4.

Second derivative of the energy stored in the Haldane model as a function of .

4. Conclusions

We have considered the energy stored in many-body free fermion quantum batteries. Such batteries are interesting because they represent a large class of models that range from Wigner–Jordan integrable spin chains to lattice models with genuinely fermionic degrees of freedom. The emphasis is on the role of quantum phase transitions on this quantity. Indeed, it was previously shown that quantum phase transitions can help increase or stabilize the energy stored, depending on the model. Moreover, the presence of quantum phase transitions in the quantum system used as a quantum battery also leads to non-analyticities in the energy stored. In this work, we have analyzed the universal features related to quantum phase transitions in free fermionic quantum batteries. To do so, we have isolated the contribution of ’the Dirac cone’. This allowed us to prove that in odd dimensions the presence of quantum phase transitions is accompanied by a finite jump in the th derivative of the energy stored. In even dimensions, on the other hand, the non-analytical behavior is a logarithmic divergence of the th derivative of the energy stored. These non-analyticities originate from the enhanced contribution of low-energy modes when the post-quench Hamiltonian approaches a gap closing, which makes the stored energy extremely sensitive to small changes in the control parameters. This critical enhancement of susceptibility shows a trade-off between stability and controllability. Indeed, on the one hand, operating close to a critical point reduces the stability of the battery, as small imperfections or noise in the protocol can produce large variations in the stored energy; on the other hand, the same sensitivity can be exploited to improve the control, since precise and intentional variations in the quenched parameter can induce strong energetic responses with a potentially positive impact on the performances of the device. We have then tested our results with two low-energy models: the quantum Ising chain in a transverse field as regards one dimension, and the Haldane model for a Chern insulator as a representative of two-dimensional systems. The results confirm what was derived in the low-energy approximation. Moreover, interestingly, the energy stored in the Haldane model intriguingly follows the topological phase diagram of the system, opening interesting perspectives for an energy-related detection of topological phases possibly applicable to some specific models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G., N.T.Z. and D.F.; methodology, R.G., N.T.Z. and D.F.; investigation, R.G.; software, R.G.; formal analysis, R.G., N.T.Z. and D.F.; visualization, R.G.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G., N.T.Z. and D.F.; writing—review and editing, R.G., N.T.Z. and D.F.; funding acquisition, N.T.Z. and D.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

N.T.Z. acknowledges funding through the “Non-reciprocal supercurrent and topological transitions in hybrid Nb-InSb nanoflags” project (Prot. 2022PH852L) in the framework of the PRIN 2022 initiative of the Italian Ministry of University (MUR) for the National Research Program (PNR). This project has been funded within the program “PNRR Missione 4—Componente 2—Investimento 1.1 Fondo per il Programma Nazionale di Ricerca e Progetti di Rilevante Interesse Nazionale (PRIN)”. D.F. acknowledges funding from the European Union- NextGenerationEU through the “Solid State Quantum Batteries: Characterization and Optimization” (SoS-QuBa) project (Prot. 2022XK5CPX), in the framework of the PRIN 2022 initiative of the Italian Ministry of University (MUR) for the National Research Program (PNR). This project has been funded within the program “PNRR Missione 4—Componente 2—Investimento 1.1 Fondo per il Programma Nazionale di Ricerca e Progetti di Rilevante Interesse Nazionale (PRIN)”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. 1-D Dirac Model

In one dimension, the stored energy around is given by the integral

In the limit , the integral can be solved as follows:

By using Equation (13), we obtain

By substituting , the first derivative of the stored energy with respect to gives

As predicted, in the limit , the discontinuity arises in the first derivative (being ) and the jump is

This result is in agreement with the general formula shown in Equation (17), since for it becomes

where we used the fact that

From the numerical analysis, we can observe in Figure A1 that, for fixed , the stored energy shows a peak at , in accordance with our previous studies [50,51,93], while its first derivative shows the jump discontinuity we predicted in the previous section, with the magnitude of such jump being exactly .

Figure A1.

Energy stored in the 1-D Dirac model as function of for (blue curve) and jump in its first derivative with respect to as function of (orange curve).

Appendix B. 2-D Dirac Model

Here, we aim at studying the energy stored in the Hamiltonian reported in Equation (5) by solving the integral of Equation (7) for

where we considered as in the previous case. Once we solve the integral

we consider the limit of approaching zero. Here,

and we obtain

whose derivative with respect to , after substituting , is

Unlike in the one-dimensional case, here the first derivative does not exhibit singularities as , since

by L’Hôpital’s theorem. However, if we derive again, we obtain

and since diverges as approaches , we observe the logarithmic divergence we predicted in Section 2. The numerical plots in Figure A2 show the stored energy (blue curve), its first derivative (orange curve) and its second derivative (green curve) with respect to for fixed . The derivative plots are consistent with our theoretical analysis, and this behavior is reflected in the energy plot, where in this case no peak appears at , unlike in the one-dimensional scenario. In contrast, the maximum energy is reached after the QPT, highlighting the advantage of undergoing a phase transition to store more energy.

Figure A2.

Stored energy in the 2-D Dirac model (blue), its first (orange) and second derivatives (green) as functions of .

References

- Fröwis, F.; Sekatski, P.; Dür, W.; Gisin, N.; Sangouard, N. Macroscopic quantum states: Measures, fragility, and implementations. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2018, 90, 025004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado, R.; Citro, R.; Lewenstein, M.; Stern, M. New Trends and Platforms for Quantum Technologies, 1st ed.; Lecture Notes in Physics, 1025; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benenti, G.; Casati, G.; Rossini, D.; Strini, G. Principles of Quantum Computation and Information; World Scientific: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Dutta, A. Quantum thermal machines and batteries. Eur. Phys. J. B 2021, 94, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, J.; Cerullo, G.; Virgili, T. Quantum batteries: The future of energy storage? Joule 2023, 7, 2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campaioli, F.; Gherardini, S.; Quach, J.Q.; Polini, M.; Andolina, G.M. Colloquium: Quantum batteries. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2024, 96, 031001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicki, R.; Fannes, M. Entanglement boost for extractable work from ensembles of quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. E 2013, 87, 042123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, F.C.; Vinjanampathy, S.; Modi, K.; Goold, J. Quantacell: Powerful charging of quantum batteries. New J. Phys. 2015, 17, 075015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campaioli, F.; Pollock, F.A.; Binder, F.C.; Céleri, L.; Goold, J.; Vinjanampathy, S.; Modi, K. Enhancing the Charging Power of Quantum Batteries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 150601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraro, D.; Campisi, M.; Andolina, G.M.; Pellegrini, V.; Polini, M. High-Power Collective Charging of a Solid-State Quantum Battery. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 117702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julià-Farré, S.; Salamon, T.; Riera, A.; Bera, M.N.; Lewenstein, M. Bounds on the capacity and power of quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. Res. 2020, 2, 023113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, D.; Andolina, G.M.; Rosa, D.; Carrega, M.; Polini, M. Quantum Advantage in the Charging Process of Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev Batteries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 236402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyhm, J.Y.; Safránek, D.; Rosa, D. Quantum Charging Advantage Cannot Be Extensive without Global Operations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 128, 140501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, F.Q.; Lu, Y.Q.; Wang, Y.J.; Sun, J.A. Extended Dicke quantum battery with interatomic interactions and driving field. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 115405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, F.Q.; Zhou, H.; Sun, J.A. Cavity Heisenberg-spin-chain quantum battery. Phys. Rev. A 2022, 106, 032212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiribella, G.; Yang, Y.; Renner, R. Fundamental Energy Requirement of Reversible Quantum Operations. Phys. Rev. X 2021, 11, 021014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioni, F.; Menta, R.; Aiudi, R.; Polini, M.; Giovannetti, V. Conveyor-belt superconducting quantum computer. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.11782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurman, Y.; Hymas, K.; Fedorov, A.; Munro, W.J.; Quach, J. Quantum Computation with Quantum Batteries. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.23610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinjanampathy, S.; Anders, J. Quantum thermodynamics. Contemp. Phys. 2016, 57, 545–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deffner, S.; Campbell, S. Quantum Thermodynamics; Morgan & Claypool Publishers: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 2053–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrega, M.; Solinas, P.; Sassetti, M.; Weiss, U. Energy Exchange in Driven Open Quantum Systems at Strong Coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 240403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, D.; Andolina, G.M.; Mari, A.; Polini, M.; Giovannetti, V. Charger-mediated energy transfer for quantum batteries: An open-system approach. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 035421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrega, M.; Cangemi, L.M.; De Filippis, G.; Cataudella, V.; Benenti, G.; Sassetti, M. Engineering Dynamical Couplings for Quantum Thermodynamic Tasks. PRX Quantum 2022, 3, 010323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrone, D.; Rossi, M.A.C.; Smirne, A.; Genoni, M.G. Charging a quantum battery in a non-Markovian environment: A collisional model approach. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2023, 8, 035007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.M.; Dou, F.Q. Resonator-qutrit quantum battery. Phys. Rev. A 2024, 109, 062432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navid Elyasi, S.; Rossi, M.A.C.; Genoni, M.G. Experimental simulation of daemonic work extraction in open quantum batteries on a digital quantum computer. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2025, 10, 025017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.; VS, I.; Sankaranarayanan, R. Dissipative Dynamics of Charged Graphene Quantum Batteries. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.12666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahverdyan, A.E.; Balian, R.; Nieuwenhuizen, T.M. Maximal work extraction from finite quantum systems. Europhys. Lett. 2004, 67, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bello, G.; Farina, D.; Jansen, D.; Perroni, C.A.; Cataudella, V.; De Filippis, G. Local ergotropy and its fluctuations across a dissipative quantum phase transition. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2024, 10, 015049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formicola, F.; Di Bello, G.; De Filippis, G.; Cataudella, V.; Farina, D.; Perroni, C.A. Local ergotropy dynamically witnesses many-body localized phases. Phys. Rev. Res. 2025, 7, 043086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahia, A.A.; Abd-Rabbou, M.; Megahed, A.M. Entanglement-driven energy exchange in a two-qubit quantum battery. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2025, 58, 065501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadipour, M.; Yousefi, N.N.; Mortezapour, A.; Miavaghi, A.S.; Haseli, S. Amplified quantum battery via dynamical modulation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Tian, Z.; Jing, J. Dissipation suppression for an Unruh-DeWitt battery with a reflecting boundary. Sci. China Physics Mech. Astron. 2025, 68, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Shao, X.Q. Reservoir-assisted quantum battery charging at finite temperatures. Phys. Rev. A 2025, 111, 062616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.P.; Levinsen, J.; Modi, K.; Parish, M.M.; Pollock, F.A. Spin-chain model of a many-body quantum battery. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 97, 022106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Yang, T.R.; Fu, L.; Wang, X. Powerful harmonic charging in a quantum battery. Phys. Rev. E 2019, 99, 052106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Qiu, J.; Souza, P.J.P.; Yuan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chu, J.; Pan, X.; Hu, L.; Li, J.; et al. Optimal charging of a superconducting quantum battery. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2022, 7, 045018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemme, G.; Grossi, M.; Vallecorsa, S.; Sassetti, M.; Ferraro, D. Qutrit quantum battery: Comparing different charging protocols. Phys. Rev. Res. 2024, 6, 023091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, A.; Giampaolo, S.; Morsch, O.; Giovannetti, V.; Franchini, F. Frustrating Quantum Batteries. PRX Quantum 2024, 5, 030319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S.; Ferraro, D.; Traverso Ziani, N. Characterization of the Performance of an XXZ Three-Spin Quantum Battery. Entropy 2025, 27, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelakos, V.; Paspalakis, E.; Stefanatos, D. Rapid charging of a two-qubit quantum battery by transverse field amplitude and phase control. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2025, 10, 035024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.y.; Jing, J. Dissipative qutrit-mediated stable charging. Phys. Rev. A 2025, 112, 032206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzoli, L.; Gemme, G.; Khomchenko, I.; Sassetti, M.; Ouerdane, H.; Ferraro, D.; Benenti, G. Cyclic solid-state quantum battery: Thermodynamic characterization and quantum hardware simulation. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2025, 10, 015064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, N. Collective charging of an organic quantum battery. Phys. Rev. E 2025, 111, 044118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.L.; Gao, T.; Fan, H. Efficient wireless charging of a quantum battery. Phys. Rev. A 2025, 111, 042216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, S.A.; Ali, M.M.; Sen, A. Enhancing the Charging Capacity of Many-Body Quantum Batteries through Landau–Zener Driving. Adv. Quantum Technol. 2025, 8, e2500098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seah, S.; Perarnau-Llobet, M.; Haack, G.; Brunner, N.; Nimmrichter, S. Quantum Speed-Up in Collisional Battery Charging. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 127, 100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaghaghi, V.; Singh, V.; Benenti, G.; Rosa, D. Micromasers as quantum batteries. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2022, 7, 04LT01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, J.; McGhee, K.E.; Ganzer, L.; Rouse, D.M.; Lovett, B.W.; Gauger, E.M.; Keeling, J.; Cerullo, G.; Lidzey, D.; Virgili, T. Superabsorption in an organic microcavity: Toward a quantum battery. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabk3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazi, R.; Sacco Shaikh, D.; Sassetti, M.; Traverso Ziani, N.; Ferraro, D. Controlling Energy Storage Crossing Quantum Phase Transitions in an Integrable Spin Quantum Battery. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 133, 197001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazi, R.; Cavaliere, F.; Sassetti, M.; Ferraro, D.; Traverso Ziani, N. Charging free fermion quantum batteries. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2025, 196, 116383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymas, K.; Muir, J.B.; Tibben, D.; van Embden, J.; Hirai, T.; Dunn, C.J.; Gómez, D.E.; Hutchison, J.A.; Smith, T.A.; Quach, J.Q. Experimental demonstration of a scalable room-temperature quantum battery. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.16541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, N.; Cavaliere, F.; Ferraro, D. The Collisional Charging of a Transmon Quantum Battery. Batteries 2025, 11, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, C.; Rosa, D.; Olle, J. Artificial intelligence discovery of a charging protocol in a micromaser quantum battery. Phys. Rev. A 2023, 108, 042618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdman, P.A.; Andolina, G.M.; Giovannetti, V.; Noé, F. Reinforcement Learning Optimization of the Charging of a Dicke Quantum Battery. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 133, 243602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.L.; Gao, T.; Fan, H. Enhancing the Charging Performance of an Atomic Quantum Battery. Adv. Quantum Technol. 2025, 8, e00422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahia, A.A. Optimizing quantum battery performance: A comparative study of parallel and series charging protocols. Phys. Scr. 2025, 100, 085403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.Y.; Zhou, H.; Dou, F.Q. Cavity-Heisenberg spin-j chain quantum battery and reinforcement learning optimization. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.01442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, F. Dissipative Charging of a Quantum Battery. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 210601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovhannisyan, K.V.; Barra, F.; Imparato, A. Charging assisted by thermalization. Phys. Rev. Res. 2020, 2, 033413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaliere, F.; Gemme, G.; Benenti, G.; Ferraro, D.; Sassetti, M. Dynamical blockade of a reservoir for optimal performances of a quantum battery. Commun. Phys. 2025, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.C.; Zhao, Z.R.; Zhuang, N.Y. Non-Markovian N-spin chain quantum battery in thermal charging process. Phys. Rev. E 2025, 112, 024129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Tian, Z.; Wang, J. Scrambling-Enhanced Quantum Battery Charging in Black Hole Analogues. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.23598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchini, F. An Introduction to Integrable Techniques for One-Dimensional Quantum Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A. Quantum Quench Dynamics. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2018, 9, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, S. Quantum Phase Transitions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyl, M.; Polkovnikov, A.; Kehrein, S. Dynamical Quantum Phase Transitions in the Transverse-Field Ising Model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 135704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyl, M.; Pollmann, F.; Dóra, B. Detecting Equilibrium and Dynamical Quantum Phase Transitions in Ising Chains via Out-of-Time-Ordered Correlators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 016801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziani, N.T.; Cavaliere, F.; Becerra, K.G.; Sassetti, M. A Short Review of One-Dimensional Wigner Crystallization. Crystals 2021, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajna, S.; Dóra, B. Disentangling dynamical phase transitions from equilibrium phase transitions. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 161105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajna, S.; Dóra, B. Topological classification of dynamical phase transitions. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 155127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurcevic, P.; Shen, H.; Hauke, P.; Maier, C.; Brydges, T.; Hempel, C.; Lanyon, B.P.; Heyl, M.; Blatt, R.; Roos, C.F. Direct Observation of Dynamical Quantum Phase Transitions in an Interacting Many-Body System. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 080501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyl, M.; Budich, J.C. Dynamical topological quantum phase transitions for mixed states. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 96, 180304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyl, M. Dynamical quantum phase transitions: A review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2018, 81, 054001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, S.; Cavaliere, F.; Sassetti, M.; Traverso Ziani, N. Topological classification of dynamical quantum phase transitions in the xy chain. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Damme, M.; Desaules, J.Y.; Papić, Z.; Halimeh, J.C. Anatomy of dynamical quantum phase transitions. Phys. Rev. Res. 2023, 5, 033090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, S.; Naji, J.; Jafari, R.; Langari, A. Scaling and universality at ramped quench dynamical quantum phase transitions. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2024, 36, 355401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghran, R.; Jafari, R.; Langari, A. Competition of long-range interactions and noise at a ramped quench dynamical quantum phase transition: The case of the long-range pairing Kitaev chain. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 110, 064302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, D.; Andolina, G.M.; Campisi, M.; Pellegrini, V.; Polini, M. Quantum supercapacitors. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 075433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, F.; Hovhannisyan, K.V.; Imparato, A. Quantum batteries at the verge of a phase transition. New J. Phys. 2022, 24, 015003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeuty, P. The one-dimensional Ising model with a transverse field. Ann. Phys. 1970, 57, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldane, F.D.M. Model for a Quantum Hall Effect without Landau Levels: Condensed-Matter Realization of the “Parity Anomaly”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1988, 61, 2015–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plekhanov, K.; Roux, G.; Le Hur, K. Floquet engineering of Haldane Chern insulators and chiral bosonic phase transitions. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 95, 045102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIver, J.W.; Schulte, B.; Stein, F.U.; Matsuyama, T.; Jotzu, G.; Meier, G.; Cavalleri, A. Light-induced anomalous Hall effect in graphene. Nat. Phys. 2020, 16, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Kang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Knüppel, P.; Tao, Z.; Li, L.; Tschirhart, C.L.; Redekop, E.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; et al. Realization of the Haldane Chern insulator in a moiré lattice. Nat. Phys. 2024, 20, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traverso, S.; Sassetti, M.; Traverso Ziani, N. Emerging topological bound states in Haldane model zigzag nanoribbons. Npj Quantum Mater. 2024, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.Z.; Kane, C.L. Colloquium: Topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 3045–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, N.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y. Topological edge states and quantum Hall effect in the Haldane model. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 78, 075438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thouless, D.J.; Kohmoto, M.; Nightingale, M.P.; den Nijs, M. Quantized Hall Conductance in a Two-Dimensional Periodic Potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 49, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkov, M.; Savona, V. Haldane quantum Hall effect for light in a dynamically modulated array of resonators. Optica 2016, 3, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Chang, M.C.; Niu, Q. Berry phase effects on electronic properties. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 1959–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Neto, A.H.; Guinea, F.; Peres, N.M.R.; Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81, 109–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazi, R.; Cavaliere, F.; Traverso Ziani, N.; Ferraro, D. Charging a Dimerized Quantum XY Chain. Symmetry 2025, 17, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).