Abstract

Telecommunication Base Transceiver Stations (BTSs) require a resilient and sustainable power supply to ensure uninterrupted operation, particularly during grid outages. Thus, this paper proposes an Adaptive Model Predictive Control (AMPC)-based Energy Management System (EMS) designed to optimize energy dispatch and demand response for a BTS powered by a renewable-based microgrid. The EMS operates under two distinct scenarios: (a) non-grid outages, where the objective is to minimize grid consumption, and (b) outage management, aiming to maximize BTS operational time during grid failures. The system incorporates a dynamic weighting mechanism in the objective function, which adjusts based on real-time power production, consumption, battery state of charge, grid availability, and load satisfaction. Additionally, a demand response strategy is implemented, allowing the BTS to adapt its power consumption according to energy availability. The proposed EMS is evaluated based on BTS loss of transmitted data under different renewable energy profiles. Under normal operation, the EMS is assessed regarding grid energy consumption. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed AMPC-based EMS enhances BTS resilience.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, extreme weather events have experienced a noticeable increase, including floods, heatwaves, droughts, and intense tropical cyclones. These events pose significant risks to the energy sector by disrupting infrastructure, fuel supply, energy production, and demand, often leading to power outages [1]. Additionally, critical loads such as telecommunication Base Transceiver Stations (BTSs) are affected due to these power outages, causing additional damage in times of emergency. The European Union Agency for Network and Information Security reported in 2021 that 23% of the incidents were due to the lack of power services [2]. In 2012, it accounted for only 7% of the cases [3], showing a noticeable increase in the last decade. Therefore, it is essential to develop climate-resilient energy systems to ensure reliable energy services based on renewable energy to support the electrical grid and critical loads [4,5].

Commonly, diesel generators are the preferred solution for this critical load as part of the backup system, and they can provide power not only when power outages occur but also when the power quality provided by the grid is not good enough. For instance, in India, 60% of BTSs suffer from power outages with a duration higher than eight hours [6]. As a result, their demand has increased in the last years, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5% up to 2031 for the telecommunication industry [7]. This solution is not ambient-friendly. Hence, the main challenge for mobile networks is access to a clean and feasible backup system based on renewable energy. Microgrids based on renewable energy and batteries are usually the main solution for providing clean energy for BTSs [8].

Three main areas are particularly important in microgrid resilience: (i) proactive scheduling, (ii) safe islanding, and (iii) survivability [9]. Several studies have addressed these aspects from various perspectives. For instance, the authors in [10] proposed a robust optimization to minimize load curtailment during energy dispatch, but variable renewable energy sources were not included. Basu et al. [11] analyzed resilience in microgrids integrating renewables and diesel generators with a focus on emission reduction and operational costs, yet grid outage scenarios were not considered. Similar studies are in [12,13]. Zhang et al. [14] used a natural aggregation algorithm for community energy scheduling during planned outages but did not address stochastic PV production or unplanned failures. Masrur et al. [15] proposed an optimal strategy considering outages and critical loads; however, their microgrid design relied heavily on diesel generation and lacked demand-side management (DSM) considerations.

Recent advances have expanded adaptive and optimization-based control strategies for improving microgrid resilience. Akarne et al. [16] proposed a sparrow-search-tuned robust PI controller for grid-connected photovoltaic systems, enhancing performance under smart microgrid conditions. While Zhang et al. [17] and Shaker et al. [18] developed adaptive energy management strategies for weather-induced outages and multi-interconnected microgrids, respectively. These studies demonstrate significant progress in network-level resilience, yet they do not address the real-time adaptability of EMS tailored to critical infrastructure such as BTSs.

While these contributions have advanced the general understanding of microgrid resilience, research focused on BTS microgrids remains scarce [19]. Existing BTS-related works primarily emphasize energy efficiency, renewable integration, or cost reduction [8,20], rather than resilience enhancement under grid disturbances based only in clean energy [21]. Most of these studies consider static control strategies or deterministic scheduling, overlooking the real-time adaptability of the EMS when transitioning between grid-connected and islanded modes. Furthermore, although DSM and demand response (DR) mechanisms have been successfully used to improve energy efficiency in BTS systems [22,23], they have been largely overlooked as resilience-enhancing tools within microgrid operation. This represents a critical gap, as effective DSM should incorporate adaptive DR mechanisms capable of dynamically adjusting BTS power consumption to available renewable energy while maintaining service continuity and network survivability during grid outages.

Hence, a clear research gap exists in developing an EMS that can adapt in real time to unpredictable grid outages, variable renewable energy, and battery state-of-charge (SoC) conditions for BTS infrastructures. To address these gaps, this paper proposes an Adaptable Model Predictive Control (AMPC) framework designed to enhance microgrid resilience for BTS applications.

Unlike previous adaptive, robust and conventional MPC approaches [24,25,26,27], which rely on fixed rule-based adaptation or pre-scheduled tuning, the proposed AMPC dynamically reconfigures the objective weights in real time according to grid status, outage duration, photovoltaic (PV) power generation and BESS state-of-charge, and BTS survivability. This formulation enables continuous adaptation, ensuring resilient operation under variable outage and seasonal conditions. Additionally, recent works have explored model-free, learning-based control to enhance EMS adaptability and resilience [28]. Such model-free methods are flexible and data-driven but rely heavily on training data and rule-based fine-tuning, which may limit their scalability for mission-critical systems like BTS networks. In contrast, the present work adopts a model-based yet dynamically adaptive strategy through an AMPC framework, providing interpretable and reliable control suitable for critical communication infrastructures. Consequently, the AMPC provides a unified and flexible control framework that bridges the gap between deterministic MPC and data-driven adaptive EMS strategies, specifically designed for BTS microgrids. Moreover, a curtailment-based DR strategy is integrated into the AMPC to optimize BTS power consumption during grid outages. Unlike previous DR implementations aimed at energy savings under normal operation, the proposed approach aims to increase survivability under grid outages.

The rest of the paper is divided as follows. Section 2 presents the system under study, considering also the operation of the BTS. Then, the energy management system framework is explained in Section 3, taking into account the operation in normal conditions and during grid outages. The mathematical approach using an Adaptable Model Predictive Control is in Section 4. The numerical simulations are detailed in Section 5, and the results are explained in Section 6.

2. System Under Study

To enhance energy resilience and reduce dependency on fossil fuel-based backup solutions, this study considers a renewable energy-powered microgrid designed to supply electricity to a critical BTS load. The microgrid consists of a PV system and a battery energy storage system (BESS). The microgrid has the functionality to be connected to the grid, but also can operate in islanded mode during outages.

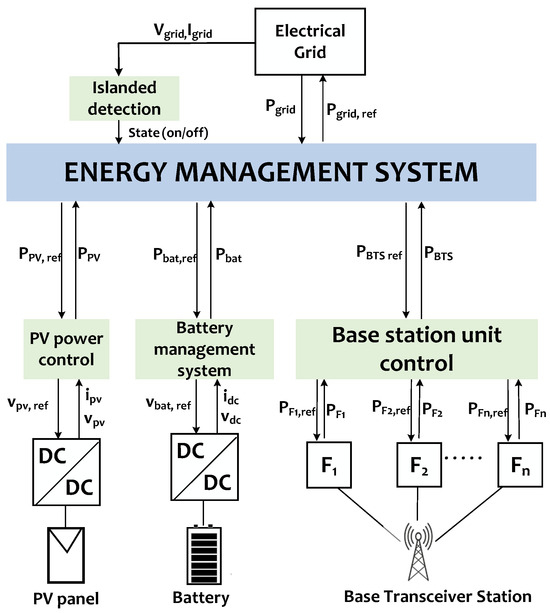

The EMS is responsible for scheduling the charging and discharging of the BESS, exchanging power with the grid, and optimizing the utilization of PV power generation based on the load and the grid’s status (connected or disconnected). It sends power reference signals to the PV-BESS inverter, ensuring efficient energy management. Furthermore, power curtailment to the load is coordinated by the BTS unit control. The control architecture of the system, depicted in Figure 1, consists of several local controllers, each tasked with real-time decision-making. These include controllers for the PV-BESS system, the BTS, and the islanded detection. Each controller processes data related to PV power production, grid availability, and power consumption to ensure the system operates optimally under varying conditions.

Figure 1.

Schematic architecture and communication flow among the photovoltaic (PV) array, battery energy storage system (BESS), and base transceiver station (BTS) load during grid-connected and islanded operation.

In this study, we will consider a BTS for a 5G network, which typically operates across multiple frequency bands, such as 800 MHz, 2100 MHz, and 3500 MHz. In general, the most power-consuming components are represented by the Power Amplifier (PA) and the frequency bands, which account for up to 70% of the entire BTS consumption [29]. Additionally, even BTSs using the same technology and frequency can exhibit differing power demands. These differences stem from factors such as transmission power variations, measurement inaccuracies, power loss along cables, and disparities in hardware models or release dates. Due to this diversity in power consumption, it is inherently important to develop a demand response strategy that allows the BTS to limit its power consumption according to its characteristics during outages. For instance, the BTS unit control can limit the power consumed by every frequency proportionally, with the risk of losing a percentage of transmitted data but increasing its survival time.

3. Operation of the Proposed Energy Management System

The EMS for the microgrid will have two modes of operation: non-grid outages and outage management. The operation of the EMS during these instances is explained as follows:

3.1. Non-Grid Outages

In grid-connected mode, the power is supplied by the grid, the PV system, and the BESS. In case there is no load, the surplus of power from the PV system is supplied to the grid. To reduce emissions, the BESS is only permitted to be charged with the PV system and not with the grid. In case the PV system and the BESS cannot supply the power, the grid also feeds the BTS. The main objective of the EMS is to minimize the purchase of power from the grid, which will consequently help to minimize carbon emissions.

The EMS will optimize the energy scheduling of the BESS, taking into account the remaining storage energy, the power consumption, and the PV power availability. The power references to each component are sent to the local controllers, which will adapt the operation accordingly. The PV power control will be based on the Maximum power point tracking (MPPT). The MPPT focuses on extracting the maximum power of the PV array at every instant by managing the DC voltage. This point of operation depends on the solar irradiance and the ambient temperature. In this study, a Perturb and Observe technique is used. In this case, no load curtailment or demand response is considered. The BTS unit control will allocate the power as usual, considering the traffic demand and resource availability.

3.2. Outage Management (Islanded Mode)

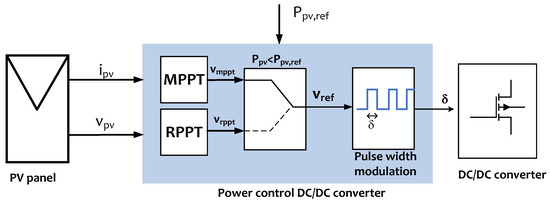

When a grid outage occurs, the grid cannot supply power to the BTS. The outage can occur for any reason, like low power quality or power cuts due to environmental hazards. In this mode, the BTS can have power from the PV and the BESS. If the PV power production is higher than needed, this is curtailed. The curtailment of PV power is developed by the inverter, where the DC voltage imposed will depend on a reference power , which will be provided by the EMS. Then, the converter will manage the DC voltage, so the PV power is curtailed using a Reference power point tracker (RPPT) (Figure 2) instead of an MPPT. The RPPT will also use a Perturb and Observe algorithm, which will be in charge of following the new power reference and adapting according to the PV power production. This control is explained in [30,31], which has shown stable response as it operates similar to a MPPT but follows a power reference provided by the EMS instead of the instantaneous maximum power point.

Figure 2.

DC–DC converter operation: MPPT in normal mode and RPPT during grid outage for resilient BTS power supply.

Additionally, the EMS will manage the demand to reduce the power consumption, considering the remaining power on the battery and the PV production availability. The main objective is to minimize load curtailment while still prolonging the survivability time. The EMS will set a power reference, which will be the maximum possible that could be provided at that instant. The same power reduction will be proportionally distributed to each frequency band. Then, the BTS will manage the frequency bands to limit its power consumption.

3.3. Management of Uncertainties

In this study, the primary source of uncertainty arises from the occurrence and duration of grid outages, both of which are assumed to be unknown and time-varying. The EMS employs the proposed AMPC framework to address these uncertainties through real-time optimization. At each control interval, the MPC predicts the system behavior over the defined horizon based on current measurements and reconfigures the objective weights according to the instantaneous system state.

Uncertainties related to PV power generation and grid outage status are treated as pervasive, meaning they are assumed constant over the prediction horizon but can change between control intervals. This reflects realistic operating conditions, where the exact timing and duration of outages cannot be forecasted. As the AMPC operates under a receding-horizon principle, the control actions are continuously updated every time step to the most recent system information. Consequently, the EMS maintains optimal performance even under unpredictable disconnections, ensuring robust and adaptive control behavior during both normal and islanded operation modes.

4. Adaptive Model Predictive Control

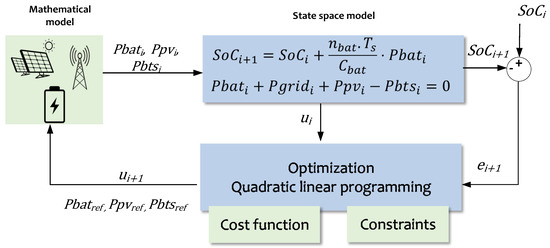

The AMPC determines the optimal power scheduling for each component of the system at every time step. For this, the AMPC estimates the future state of the system based on the current measured variables, expected disturbances, and control signals. Depending on the grid conditions, the AMPC reconfigures the objective weights and constraints. Next, the optimization problem is solved to minimize the adaptive cost function, and the resulting control actions are applied to the converter and DR modules. This sequence is repeated continuously under the receding-horizon principle, ensuring that the control decisions remain adaptive to real-time operating conditions. The main structure of the AMPC is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Block diagram of the Adaptive Model Predictive Control (AMPC) framework.

4.1. State Space Model

A state space model is used to capture the dynamics of the microgrid, where the state variable () is the BESS’s SoC (). Meanwhile, the decision variable () is a vector which considers the power exchange with the grid , battery charging/discharging power (), PV power curtailed , and the BTS power curtailed . Meanwhile, the disturbance () occurs due to the PV power production and BTS power consumption (). The vectors appearing in the state space model are:

The BESS’s SoC model and the power balance represent the dynamics of the microgrid. The predicted SoC depends on the efficiency (), the sampling time (), which in this case is the same as the control horizon, the , and battery-rated capacity :

In this model, the efficiency is assumed to be the same for the charging and discharging process. The battery compensates for any power unbalance in the system, which obeys the power balance of the microgrid. The power balance equation is represented as follows:

where is a binary variable which represents the state of the grid, where if it is 1, the grid is operating normally, and if it is 0, then there is a grid outage. The power balance varies depending on whether the microgrid is operated in grid-connected or islanded mode. Then, the state space representation is as follows:

where the matrix A and C are an identity matrix I. Then, the matrix B and are as follows:

4.2. Objective Function

The objective function in the EMS using AMPC searches for the stable power flow of the microgrid. Additionally, the objective function for this microgrid will search for a high degree of autonomy by minimizing the grid purchased from the grid. Also, it will look to minimize any load and PV curtailment when a grid outage occurs, maximizing the load survivability. The priority of these conditions is established by the weights in the objective function. The objective function is given by:

where Q is the weight factor penalizing grid power usage. R is the weight factor penalizing battery usage. T: Weight factor penalizing PV and load curtailments. The weighting factors Q, R, and T in the MPC’s objective function are dynamically adjusted according to three key metrics: Grid Dependency (), Battery utilization () and Load Satisfaction (). Grid dependency measures the reliance on the utility grid to meet the microgrid’s power demands. It is calculated as the ratio of total grid power usage to the maximum allowable grid power:

where is the power drawn from the grid at time step t, and is the maximum allowable grid power. The weight Q, which penalizes grid power usage, is updated as follows:

This adjustment increases the penalty ad power when the dependency is high and decreases it when the dependency is low. This is applied only during the summer months. Meanwhile, during winter, the adjustment is to guarantee that the battery is not being used in times when no outages occur, plus it can also be charged by the electric grid.

Battery utilization reflects the use of the battery, particularly how much energy is cycled through the battery. It is calculated as:

where is the battery power at time step t, and is the maximum allowable battery power. The weight R, which penalizes excessive use of the battery, is adjusted as:

This encourages efficient use of the battery by penalizing low usage and decreasing the penalty when its use is high.

Load satisfaction is the ratio of the total actual load met to the total load demand:

where is the load curtailment at time step t. The weight T, which penalizes load curtailment, is updated as:

When load satisfaction is below 80%, the penalty on load curtailment is reduced, encouraging the AMPC to prioritize meeting the load. If load satisfaction is high, the penalty is increased, allowing greater flexibility to curtail load if necessary. These dynamic adjustments allow the AMPC to adapt to real-time operating conditions, balancing between minimizing grid power usage, optimizing battery utilization, and ensuring that load demand is met with minimal curtailment.

4.3. Constraints

The problem formulation is subject to the constraints given by the physical limitations of the main components. The control signals should stay inside the following limits to ensure safe operation:

Additionally, the PV array and the battery are connected to the same inverter. The surplus of both powers cannot exceed the limitation of the inverter. The constraints are as follows:

Then, to reduce the degradation of the battery, the MPC will avoid deep discharge of the battery.

4.4. Real-Time Control Implementation

After defining the objective function and operational constraints, the proposed AMPC is executed in real time by the EMS. The controller updates its decisions every sampling period based on the measured PV generation, battery SoC, BTS power demand, and grid status.

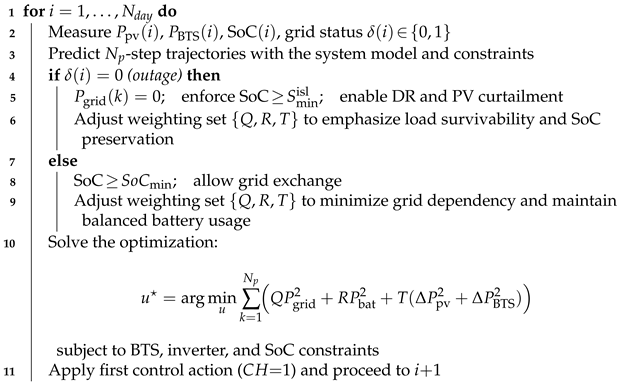

The weighting coefficients are updated at every control interval using a rule-based adaptation driven by three system metrics: grid dependency, battery utilization, and load satisfaction. Threshold values of 0.5 and 0.8 determine the transitions between high and low penalty states, while seasonal adjustments modify grid-related priorities to account for renewable variability. These updates occur automatically every sampling period. The detailed control sequence is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Simplified Real-Time Adaptive MPC Execution |

|

Unlike conventional MPC approaches with fixed weighting coefficients, the proposed AMPC continuously updates its objective weights in real time based on measured system conditions. This mechanism enables the EMS to modify control priorities dynamically—for instance, prioritizing grid independence during normal operation and maximizing load survivability during grid outages.

5. Numerical Simulations

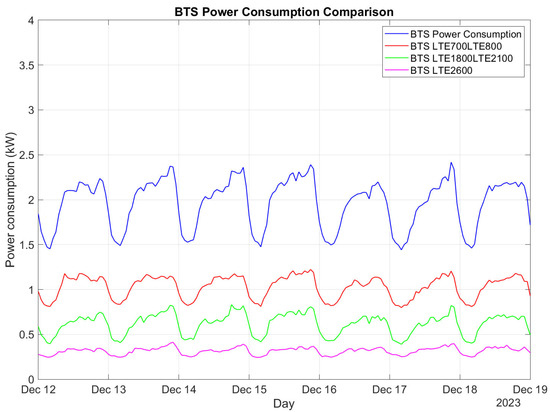

The numerical simulation considers a PV system with a 10 kWp capacity and a BESS with an energy capacity of kWh, as designed in [32]. The PV generation profiles come from the dataset “Photovoltaic Power and Weather Parameters” made available by SolarTechlab at Politecnico di Milano and have been rescaled for a 10 kWp system [33]. Hourly BTS power consumption data was obtained from an Italian mobile network operator. The BTS in this study, which has high power demand, operates three cells with 700 MHz, 800 MHz, 2100 MHz, and 2600 MHz frequencies. The total BTS power consumption for one day is illustrated in Figure 4. The power consumed by every frequency in the BTS is also illustrated.

Figure 4.

Weekly BTS power consumption profile during December 2023. The figure shows the total BTS load and the contribution of each frequency band (700 MHz, 800 MHz, 2100 MHz, and 2600 MHz). Data obtained from an Italian mobile network operator.

Outages are simulated for 4 h daily, occurring at different times but only once per day. A week from December and July is analyzed, selecting the best and worst day profiles for further AMPC evaluation. These two representative weeks were selected to reflect distinct environmental conditions: the December week corresponds to low solar irradiance and predominantly cloudy weather, while the July week represents high irradiance and sunny conditions. This selection enables the evaluation of the AMPC strategy under contrasting seasonal and meteorological scenarios, ensuring that both challenging and favorable operating conditions are captured. All analyses are performed through numerical simulations, using realistic load and irradiance data rather than experimental measurements. The initial SoC is set between 10% and 90% at the start of each day.

Table 1 summarizes the key model and simulation parameters adopted in this study, including the PV and BESS characteristics, inverter constraints, control settings, and outage management policies. These parameters define the baseline conditions under which all numerical experiments are conducted.

Table 1.

Main simulation and model parameters used for the AMPC implementation.

The proposed AMPC methodology is compared with an MPC using a fixed objective function (MPC-FO), where Q, R, and T remain unchanged [32]. Four case studies are tested for summer and winter, where the objective function remains fixed throughout the day. Table 2 summarizes the weight factors.

Table 2.

Weight Factors for Different Algorithms and Seasons.

The key performance indicator chosen for this study is the percentage of total loss of traffic (LT). The loss of transmitted data for the total BTS will be calculated as a direct proportion of the loss of power due to the demand response strategy. This was evaluated considering the actual transmitted data of each frequency and their new power consumption.

Finally, the computational performance of the AMPC was evaluated to verify its suitability for real-time operation. The optimization routine was implemented in MATLAB R2024b using a quadratic programming (QP) solver executed at each control step. The average computation time per iteration was approximately s, with a maximum observed time of s. These values are well below the 5-min sampling interval, confirming that the proposed AMPC framework can operate reliably in real-time embedded implementations. The proposed simulations assume nominal inverter operation with sufficient DC-link support from the BESS, ensuring that black-start conditions are not triggered during islanded operation. Power ramp-rate limits are implicitly satisfied by the 5-min sampling interval and the bounded control variables within the optimization problem, which guarantee gradual transitions and numerical stability. All BTS frequency bands are managed under a unified demand-response profile, applying proportional curtailment across carriers.

6. Results and Analysis

To analyze the efficiency of the proposed methodology, in this section, we delve into the sensitivity analysis considering the weight factors, the SoC levels, and the time of the day an outage occurs. Then, we present an analysis in terms of energy, first considering the power profile, the grid energy consumption, and the energy curtailed when a grid outage occurs. Later, we discuss the effect on the BTS.

6.1. Sensitivity Analysis

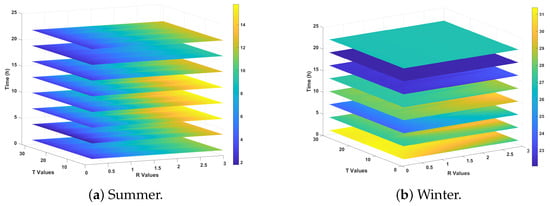

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the impact of weight factors on energy curtailment during outages and grid energy consumption during normal operation. The study considers an initial BESS SoC of 50% and varies the curtailed power weight factor (T) from 0 to 30 and the BESS power use weight factor (R) from 0 to 3, while keeping the grid power consumption factor fixed. The analysis was performed for a single day in both winter and summer. Figure 5 illustrates the variation in grid energy consumption as a function of weight factors, while Figure 6 depicts the corresponding energy curtailed from the load.

Figure 5.

Energy from the grid variation (kWh) for one day when outages occur at certain times of the day as a function of the weight factors of the objective function. Outage duration per day: 4 h; initial BESS SoC: 50%.

Figure 6.

Load energy curtailment during outage events as a function of the outage time and objective function weight factors R and T. Results are shown for both summer and winter.

Energy curtailment and grid consumption vary with seasonal conditions. During summer, the system remains relatively stable across different weight factors, showing consistent behavior in both curtailment and grid energy use. The best results are obtained when the R weight factor remains below 0.5. In winter, performance is highly dependent on the time of day an outage occurs, making it difficult to determine a universally optimal weight factor. For instance, when an outage occurs at 5 a.m., curtailment is minimized when R is close to 3, regardless of the value of T. This pattern persists throughout the night, while during daylight hours, variations in weight factors have a smaller impact. However, grid energy consumption is more sensitive to changes in R and T, especially in the early morning, where even slight variations can significantly increase consumption.

6.2. Energy Analysis

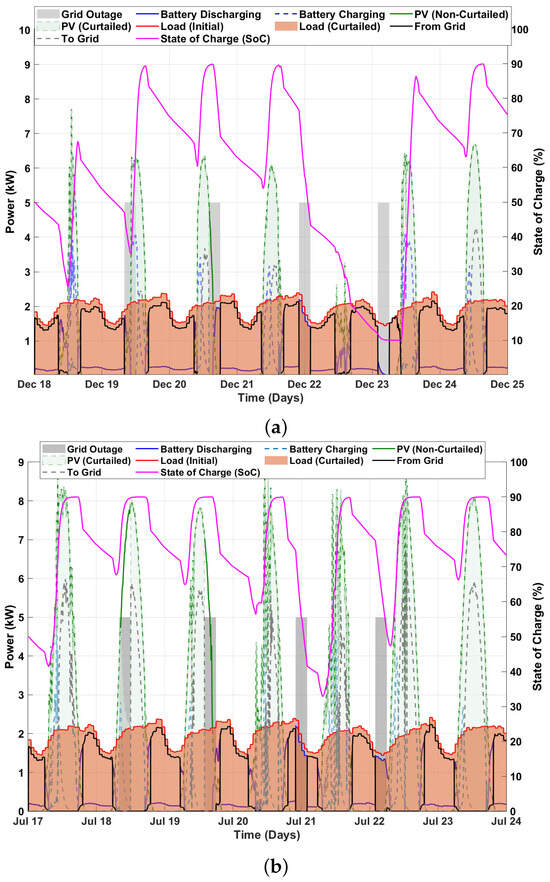

6.2.1. Power Profile

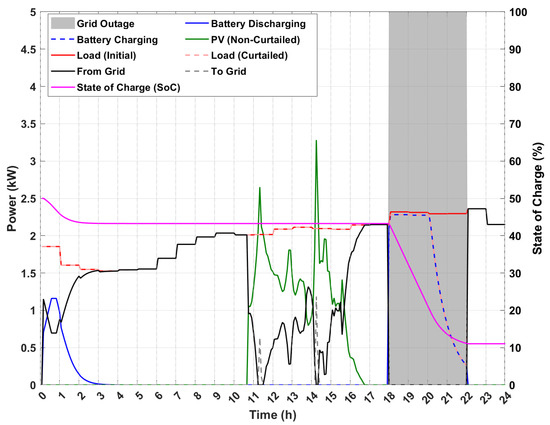

Figure 7 presents the power profile during outages over one week in both winter and summer. The system is designed to minimize grid dependence during normal operation. At night, a portion of the power supply is drawn from the battery instead of the grid. Additionally, the battery charges exclusively from the PV system, preventing grid-based charging and ensuring continuous emission reductions. During outages, the system disconnects from the grid, curtails PV power production, and maintains BTS operation. When an outage occurs, demand response is activated, leading to power curtailment. For instance, on December 20th, curtailment reaches a maximum of 11%, whereas on December 21st, it remains below 5%. A similar trend is observed in the summer.

Figure 7.

Comparison of microgrid power profiles during outage weeks in winter and summer. (a) Power profile when outages occur during one winter week. (b) Power profile when outages occur during one summer week.

However, during the early morning outage on December 23rd, the battery was unable to supply additional power as its SoC had dropped to 10% at the start of the event. This was due to an outage on December 22nd, combined with low PV power generation, which prevented the BESS from recharging beyond 50%, leaving it incapable of providing energy for the subsequent outage. Additionally, Figure 8 illustrates the power profile for December 22nd, where an outage occurs between 6 p.m. and 10 p.m., with an initial BESS SoC of 50%. At the start of the outage, curtailment is minimal (below 2%). However, between 8 p.m. and 10 p.m., curtailment increases significantly, reaching 90%, highlighting the system’s limitations when SoC is insufficient. It is important to note that these profiles do not represent conventional setpoint tracking but rather the adaptive redistribution of available power among the PV system, BESS, and load to ensure continuous BTS operation during outages.

Figure 8.

Microgrid power profile when outages occur during one day of winter; BESS SoC = 50%.

6.2.2. Energy from the Grid

When no outages occur, the AMPC aims to minimize grid consumption. In the case of an outage, which occurs during a specific period, the system can exchange power with the grid both before and after the outage. Figure 9 illustrates the energy purchased from the grid in one day for each case study, depending on the initial SoC of the BESS and the time of day the outage occurs.

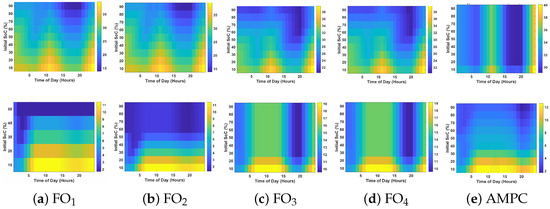

Figure 9.

Heatmaps showing total grid energy consumption (kWh) under the AMPC and MPC-FO cases as a function of outage time and initial BESS SoC (10–90%). The upper row corresponds to winter scenarios, and the lower row to summer scenarios.

During winter, the AMPC demonstrates better performance in reducing grid energy consumption compared to other case studies, particularly during the early morning and night hours. The other cases behave similarly to each other, with Case 1 (FO1) showing the least efficiency. In summer, Case 1 (FO1) and Case 2 (FO2) exhibit similar performance when the initial BESS SoC is below 50%, with grid consumption primarily low during the early morning hours. Case studies 3 (FO3) and 4 (FO4) also behave similarly. In these cases, when the initial BESS SoC is lower than 20% and the outage occurs between 5 a.m. and 3 p.m., grid energy consumption can range from 17 kWh to 19 kWh. For the same time period, if the BESS SoC is between 30% and 90%, grid consumption remains constant at around 16 kWh.

With the AMPC approach, when the initial BESS SoC is below 30% and the outage occurs between 5 a.m. and 8 p.m., grid consumption can range from 8 kWh to 12 kWh. For initial SoC values higher than 30%, grid consumption throughout the day ranges from 2 kWh to 6 kWh. These results demonstrate that the AMPC ensures optimal system operation by dynamically adjusting its weight function according to the system’s needs throughout the day.

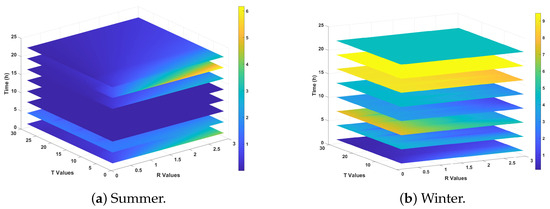

6.2.3. Load Curtailment

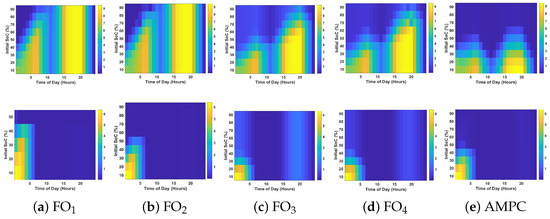

Due to demand response during an outage, the power supplied to the load is reduced, leading to load curtailment. The extent of this curtailment depends on the timing and duration of the outage, as well as the initial BESS SoC at the start of the day. Figure 10 illustrates the energy curtailment for both winter and summer across all case studies.

Figure 10.

Heatmaps of load energy curtailment (kWh) versus outage time and initial BESS SoC (10–90%) for all case studies. Results are presented for winter (top) and summer (bottom) conditions.

During summer, the curtailment behavior is similar for FO1, FO2, and AMPC, with more significant curtailment observed when the outage occurs early in the morning and the initial BESS SoC is below 40%. In contrast, FO3 and FO4 display higher curtailment between 3 p.m. and 9 p.m., ranging from 1 to 2 kWh, while showing comparable behavior in the early hours.

In winter, FO1 and FO2 show similar patterns, with curtailment varying between 2 to 9 kWh in the morning. As the BESS SoC increases to 70% from 5 a.m. onward, curtailment rises, but from 3 p.m. to 8 p.m., it stabilizes even with SoC up to 90%. FO3 and FO4 outperform FO1 and FO2 in winter, exhibiting higher curtailment in the morning when the BESS SoC is below 50%. From 3 p.m. to 9 p.m., curtailment remains nearly constant for SoC values below 50%, decreasing as the SoC increases.

The AMPC approach delivers the best performance overall, with minimal curtailment. It ensures optimal load curtailment by limiting reductions to when the BESS SoC falls below 50%, resulting in more efficient energy usage compared to the other case studies. The results confirm that the AMPC maintains stable operation under different outage scenarios. Even when the outage timing shifts from early morning to late evening, the control strategy ensures continuous BTS operation and minimizes load curtailment, demonstrating effective resilience against temporal uncertainty.

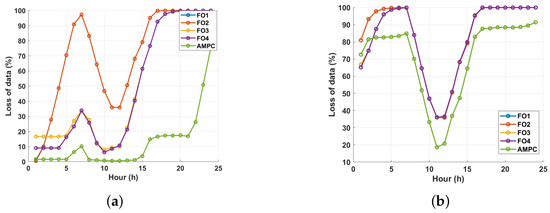

6.3. Effect on Transmitted Data

Figure 11 illustrates the percentage of traffic data loss when the BESS SoC is 50% and 20%, across all cases during winter. In this analysis, the power for each frequency was reduced proportionally according to the setpoint defined by the EMS during demand response. The corresponding data loss was then estimated, assuming a direct proportionality to the reduction in power, while the rest of the BTS performance remained unchanged. When the initial BESS SoC is 50%, data loss varies throughout the day depending on the outage time. Among all cases, FO2 exhibits the highest data loss between 5 a.m. and 10 a.m. However, after 3 p.m., AMPC is the only approach that maintains a lower data loss compared to the other cases.

Figure 11.

Comparison of BTS traffic data loss across all control strategies (FO1–FO4 and AMPC) for two BESS SoC levels: (a) Percentage of loss of traffic data when BESS SoC is 50%. and (b) Percentage of loss of traffic data when BESS SoC is 20%. Data loss is estimated proportionally to power curtailment during grid outages.

When the initial BESS SoC is 20%, early-morning and late-night outages cause complete (100%) data loss for FO1–FO4. Around midday, losses decrease slightly. In contrast, AMPC limits data loss to 80%, maintaining partial communication capability for emergency services.

6.4. Average Performance Indicators

To complement the detailed daily and hourly analyses, this subsection summarizes the averaged performance of the AMPC derived from the week-long simulations in both winter and summer. These indicators quantify the overall energy efficiency and resilience improvements achieved by the adaptive strategy.

Across all tested days, the AMPC reduced average grid energy consumption by approximately 35% compared with the fixed-objective MPC (MPC-FO). The average load curtailment during outages remained below 6%, indicating efficient demand-response coordination even under limited renewable availability. Furthermore, the resilience index—defined as the percentage of outage duration during which the BTS remained powered—exceeded 90% in both seasons. These indicators, summarized in Table 3, confirm that the proposed AMPC maintains stable and resilient performance across varying outage times, SoC levels, and seasonal conditions.

Table 3.

Approximate averaged performance indicators derived from week-long simulations.

7. Conclusions

This paper presented an Adaptable Model Predictive Control (AMPC) framework for enhancing the resilience of BTS microgrids powered by renewable energy sources. The proposed EMS continuously adapts its objective function and operational constraints based on real-time conditions such as grid status, battery state-of-charge (SoC), and outage duration. By integrating a curtailment-based demand response mechanism, the system dynamically adjusts BTS power consumption during outages, extending survivability while maintaining communication service continuity.

In contrast to conventional adaptive or robust MPC strategies, which rely on rule-based parameter updates or pre-scheduled tuning, the AMPC introduces a real-time dynamic weighting mechanism that reconfigures control priorities autonomously. This offers a more seamless and flexible approach to resilience management in microgrids. Overall, the proposed AMPC framework demonstrated consistent performance across seasonal conditions, achieving an average grid energy reduction of approximately 35%, maintaining load curtailment below 6%, and ensuring more than 90% BTS operational resilience during grid outages.

Although this study focuses on a single BTS microgrid configuration, the proposed AMPC framework is inherently modular and scalable. The control architecture can be extended to manage multiple BTSs through a coordinated or distributed EMS layer, where each node executes local AMPC optimization. Furthermore, the algorithm can be adapted to different climatic zones by incorporating localized solar irradiance and temperature models within the prediction horizon. In hybrid PV–battery–diesel or fuel cell configurations, the AMPC could dynamically introduce additional decision variables to optimize fuel-based generation while maintaining emission and cost constraints.

It is important to note that the comparison in this work focuses exclusively on MPC-based strategies to isolate the effect of adaptive weighting on control performance. Future studies may explore hybrid approaches that integrate adaptive MPC with heuristic-based energy management. Additionally, we will focus on extending the AMPC framework to multi-BTS systems operating under diverse climatic conditions and hybrid PV–battery–diesel configurations. Experimental validation through hardware-in-the-loop testing and integration with 5G network simulators will also be pursued to evaluate communication-level impacts and ensure practical deployment readiness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.-T. and F.G.; methodology, A.C.-T.; resources, G.V. and G.P.; data curation, G.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.-T., G.V., and G.P.; writing—review and editing, A.C.-T., G.V., G.P., F.G., and S.L.; supervision, M.M., S.L., and F.G.; project administration, M.M., S.L., and F.G.; funding acquisition, M.M., S.L., and F.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article was supported by the European Union under the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) of NextGenerationEU, partnership on “Telecommunications of the Future” (PE00000001—program “RESTART”, Structural Project 6GWINET, Focused Project R4R).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because they come from a private company. Requests to access the datasets regarding the power consumption of the BTS should be directed to Vodafone.

Acknowledgments

We thank Vodafone Italy for providing technical support and resources used during the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IEA. Climate Resilience Policy Indicator; Technical Report; IEA: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Malatras, A.; Bafoutsou, G.; Taurins, E.; Dekker, M.; The European Union Agency for Cybersecurity. ENISA—Annual Report Telecom Security Incidents 2021; Technical Report July; ENISA: Athens, Greece, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Marnix, D.; Christoffer, K.; Matina, L. ENISA—Annual Incident Reports 2012. Technical Report August. 2013. Available online: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/annual-incident-reports-2012 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Umunnakwe, A.; Huang, H.; Oikonomou, K.; Davis, K.R. Quantitative analysis of power systems resilience: Standardization, categorizations, and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 149, 111252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Sun, T.; Liu, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, R.; Li, F. Resilience Evaluation and Enhancement for Island City Integrated Energy Systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 2744–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transparency Market Research. Diesel Generator Market in Telecom Industry Statistics Report 2023–2031; Technical Report; Transparency Market Research: Albany, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.; Tongsopit, S.; Kittner, N. Transitioning from diesel backup generators to PV-plus-storage microgrids in California public buildings. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 38, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Tobar, A.; Grimaccia, F.; Leva, S. Energy Resilience in Telecommunication Networks: A Comprehensive Review of Strategies and Challenges. Energies 2023, 16, 6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Bui, V.H.; Kim, H.M. Microgrids as a resilience resource and strategies used by microgrids for enhancing resilience. Appl. Energy 2019, 240, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaei, A. Resiliency-oriented microgrid optimal scheduling. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2014, 5, 1584–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, M.; Jena, C.; Khan, B.; Ali, A. Optimal Bidding Strategies of Microgrid with Demand Side Management for Economic Emission Dispatch Incorporating Uncertainty and Outage of Renewable Energy Sources. Energy Eng. 2024, 121, 849–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Vasquez, J.C.; Guerrero, J.M.; Guan, Y.; Golestan, S.; De La Cruz, J.; Koondhar, M.A.; Khan, B. A Comparison of Grid-Connected Local Hospital Loads with Typical Backup Systems and Renewable Energy System Based Ad Hoc Microgrids for Enhancing the Resilience of the System. Energies 2023, 16, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfuz-Ur-Rahman, A.M.; Islam, M.R.; Muttaqi, K.M.; Sutanto, D. An Effective Energy Management with Advanced Converter and Control for a PV-Battery Storage Based Microgrid to Improve Energy Resiliency. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2021, 57, 6659–6668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Dong, Z.Y.; Luo, F.; Ranzi, G.; Xu, Y. Resilient Energy Management for Residential Communities under Grid Outages. In Proceedings of the 2019 9th International Conference on Power and Energy Systems, ICPES 2019, Perth, WA, Australia, 10–12 December 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masrur, H.; Sharifi, A.; Islam, M.R.; Hossain, M.A.; Senjyu, T. Optimal and economic operation of microgrids to leverage resilience benefits during grid outages. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 132, 107137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akarne, Y.; Essadki, A.; Nasser, T.; Annoukoubi, M.; Charadi, S. Optimized control of grid-connected photovoltaic systems: Robust PI controller based on sparrow search algorithm for smart microgrid application. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2025, 8, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A.; Peyghami, S.; Li, Y.; Dragicevic, T.; Blaabjerg, F. A Proactive Operating Strategy for Microgrid Resilience Enhanced for Weather-induced Outages. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 10th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference, IPEMC 2024 ECCE Asia, Chengdu, China, 17–20 May 2024; pp. 4877–4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, H.K.; Keshta, H.E.; Mosa, M.A.; Ali, A.A. Energy management system for multi interconnected microgrids during grid connected and autonomous operation modes considering load management. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheykhi, N.; Salami, A.; Guerrero, J.M.; Agundis-Tinajero, G.D.; Faghihi, T. A comprehensive review on telecommunication challenges of microgrids secondary control. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 140, 108081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Luna, E.; Palacios, M.A.; Vasquez, J.C. New Microgrid Architectures for Telecommunication Base Stations in Non-Interconnected Zones: A Colombian Case Study. Energies 2025, 18, 5499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, M.; Brunaccini, G.; Sergi, F.; Aloisio, D.; Randazzo, N.; Antonucci, V. From Uninterruptible Power Supply to resilient smart micro grid: The case of a battery storage at telecommunication station. J. Energy Storage 2020, 28, 101207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, L.; Lin, X.; Gadiyar, R. Toward Energy Efficient RAN: From Industry Standards to Trending Practice. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2025, 32, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, W.Y.; Leong, Y.Z.; Leong, W.S. Green Communication Systems: Towards Sustainable Networking. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Information Science, Parallel and Distributed Systems, ISPDS 2024, Guangzhou, China, 31 May–2 June 2024; pp. 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Tobar, A.; Blasuttigh, N.; Pavan, A.M.; Spagnuolo, G. Demand response of an Electric Vehicle charging station using a robust-explicit model predictive control considering uncertainties to minimize carbon intensity. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2024, 38, 101381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, D.Y.; Vechiu, I.; Gaubert, J.P.; Jupin, S. Hierarchical Model Predictive Control to Coordinate a Vehicle-to-Grid System Coupled to Building Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, M.N.S.K.; Liang, X.; Li, W.; Imtiaz, S.; Quaicoe, J. A Novel Model Predictive Controller for Distributed Generation in Isolated Microgrids—Part II: Model Predictive Controller Implementation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2022, 58, 5860–5870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Song, Z.; Hofmann, H.; Sun, J. Adaptive model predictive control for hybrid energy storage energy management in all-electric ship microgrids. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 198, 111929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, A.; Zeinali, M.; Marzband, M. Model-free reinforcement learning-based energy management for plug-in electric vehicles in a cooperative multi-agent home microgrid with consideration of travel behavior. Energy 2024, 288, 129725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallero, G.; Cabrera-Tobar, A.; Perin, G.; Renga, D.; Badia, L.; Rossi, M.; Meo, M.; Grimaccia, F.; Leva, S. Network Resilience and Sustainability: Renewable Energy-Based Solutions. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2025, 63, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craciun, B.I.; Kerekes, T.; Sera, D.; Teodorescu, R. Frequency support functions in large PV power plants with active power reserves. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2014, 2, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.V.; Sarkar, V. A Comparative Study of Different Operating Regions for Performing the Regulated Power Point Tracking in Photovoltaic Systems. In Proceedings of the 2021 National Power Electronics Conference, NPEC 2021, Bhubaneswar, India, 15–17 December 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Tobar, A.; Grimaccia, F.; Leva, S. Design Considerations and Energy Management System for Green and Reliable Telecommunication Base Stations. In Proceedings of the 24th EEEIC International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 8th I and CPS Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe, EEEIC/I and CPS Europe 2024, Rome, Italy, 17–20 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leva, S.; Nespoli, A.; Pretto, S.; Mussetta, M.; Ogliari, E.G.C. PV plant power nowcasting: A real case comparative study with an open access dataset. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 194428–194440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).