Two-Stage Energy Dispatch for Microgrids Based on CVaR-Dynamic Cooperative Game Theory Considering EV Dispatch Potential and Travel Risks

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Paper Contributions and Organization

- In this paper, an uncertainty model based on CVaR is designed considering photovoltaic (PV), wind turbine (WT), load, and EV charging uncertainty. In the day-ahead stage, an EV aggregation model is established based on predicting EV users’ driving behavior, and the dispatchable potential calculation is realized. The day-ahead energy scheduling plan was designed based on EV dispatchable potential and CVaR to reduce the power purchase cost for MG operators as well as the charging cost for EV users.

- Based on EV users’ travel information, an EV travel risk function is designed, and then an EV demand–response energy management strategy based on incentives is designed to satisfy EV users’ travel demand and reduce the real-time charging cost by considering travel risk, charging cost, and EV battery loss.

- In the real-time stage, a real-time correction strategy based on the dynamic cooperative game is proposed. By means of compensation incentives, EV users are stimulated to form cooperative alliances, and their charging and discharging power is adjusted through EV cooperative alliances to compensate for dynamic power deviations caused by various types of uncertainties and reduce real-time adjustment costs for MG operators.

2. Day-Ahead Energy Scheduling Method Based on CVaR Risk Assessment Considering Schedulable Potential Capacity of EVs

2.1. Uncertainty Model for Payload Based on CVaR

2.2. Model of Schedulable Potential Capacity of EVs

2.2.1. Model of EVs

2.2.2. Schedulable Potential Capacity of EVs

2.3. Day-Ahead CVaR-Based Scheduling Model Considering Schedulable Potential Capacity of EVs

2.3.1. Objective Function

2.3.2. Constraints

- (1)

- Power balance

- (2)

- Grid constraints

- (3)

- EV constraints

2.3.3. Approach

3. Real-Time Correction Approach Based on Dynamic Game Considering EV Travel Risk

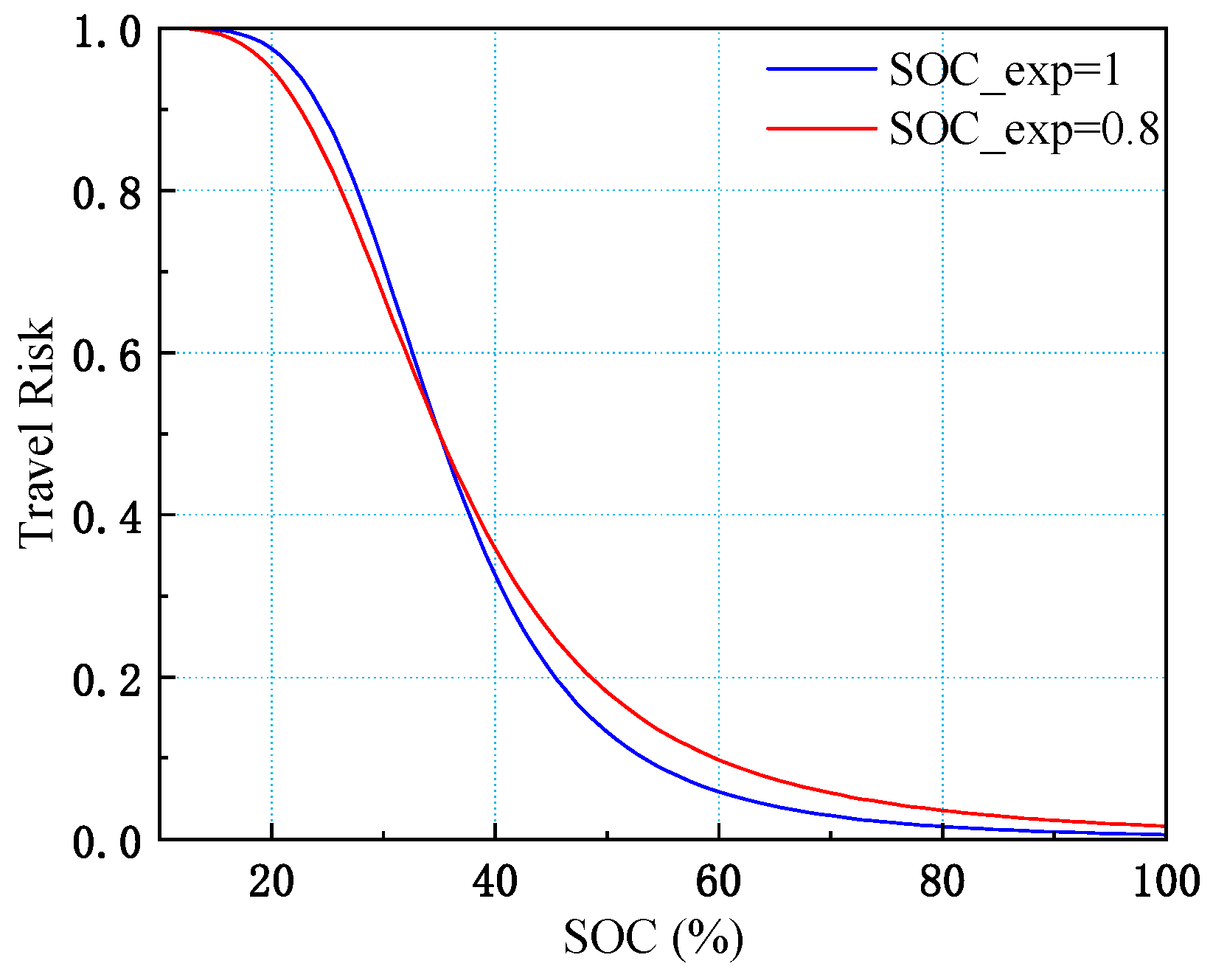

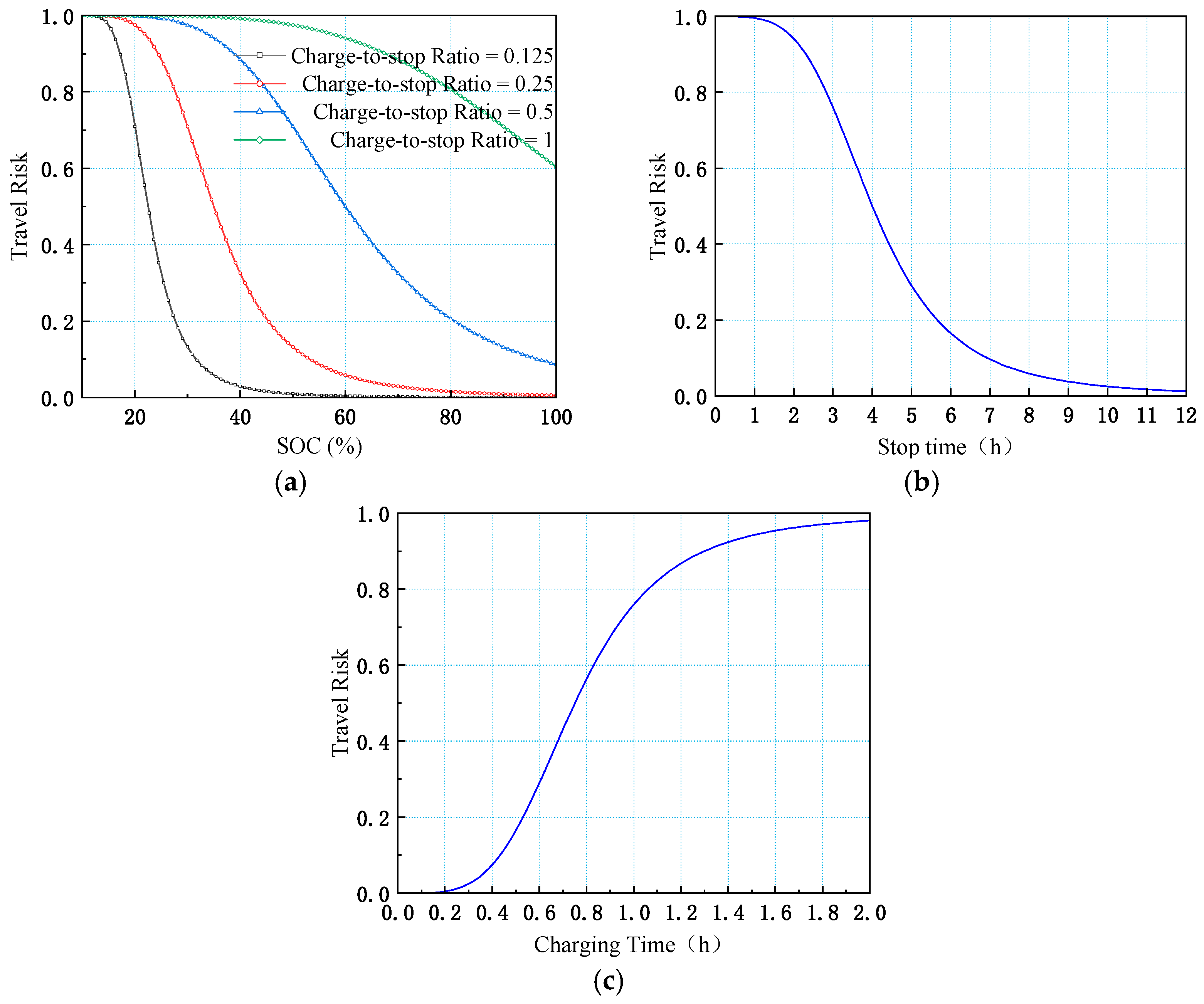

3.1. Model of EV Travel Risks

3.2. Decision Model Based on Dynamic Cooperative Game Considering EV Travel Risk

3.2.1. A Brief Overview of Cooperative Game Theory

- (1)

- Validity: For all individuals participating in the coalition, the benefits gained from participating in the system scheduling in the coalition should be greater than the benefits of individual participation, otherwise individuals will not participate in the coalition; at the same time, the sum of the benefits of all individuals in the coalition is equal to the coalition’s benefits.

- (2)

- Symmetry: If the gamers in the coalition are exchangeable with each other, then their benefits or allocations should also be the same.

- (3)

- Additivity: If two independent cooperative games are combined into a new game, then the solution of the new game is equal to the sum of the solutions of the two original games [33].

3.2.2. Objective Function

- (1)

- EV Union Objective Function

- (2)

- MG objective function

3.2.3. Constraints

- (1)

- Real-time power balance constraints

- (2)

- Grid constraints

- (3)

- EV constraints

3.3. Approach

- (1)

- Initialize the parameters related to MGs, EVs, and cooperative alliances at time t, including parameters such as MG power shortfall, tariff, EV travel risk, and benefits gained from EV participation in scheduling.

- (2)

- Set the initial number of cooperative union EVs towhere is the MG power gap and is the minimum non-zero discharge power.

- (3)

- Calculate the total EV response power from the number of participating EVs and pass it to the lower-level model.

- (4)

- The lower-level model calculates the real-time adjustment cost without EV participation. Then, the EVs that meet the requirements are extracted based on the total EV response power and the number of EVs, and the real-time adjustment cost of the cooperative union’s participation and the cooperative union’s benefits are optimally solved based on the Gurobi solver, and passed into the upper-level model.

- (5)

- The upper-level model calculates the benefits gained from the EVs’ participation in the cooperative union according to Equation (34).

- (6)

- Judge whether all EVs participating in the cooperative union are profitable according to Equation (30). If all of them are profitable, output the real-time adjustment cost and EV profitability; otherwise, execute (7).

- (7)

- Judge whether the number of EVs reaches the upper and lower limits. If so, stop the iteration and output the real-time adjustment cost and EV profitability; otherwise, adjust the number of EVs and execute (3).

4. Simulation and Case Study Results

4.1. EV Travel Risk Analysis

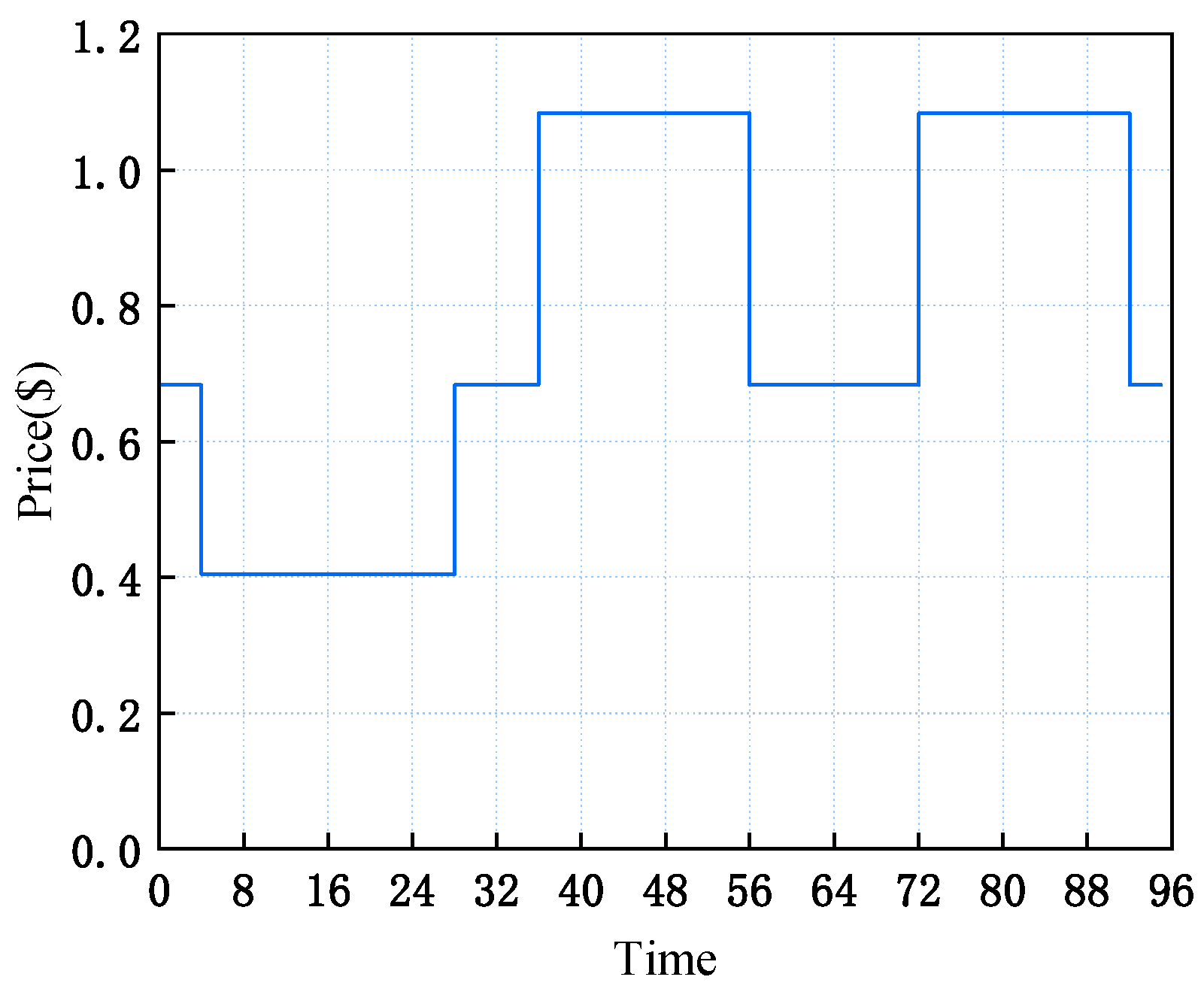

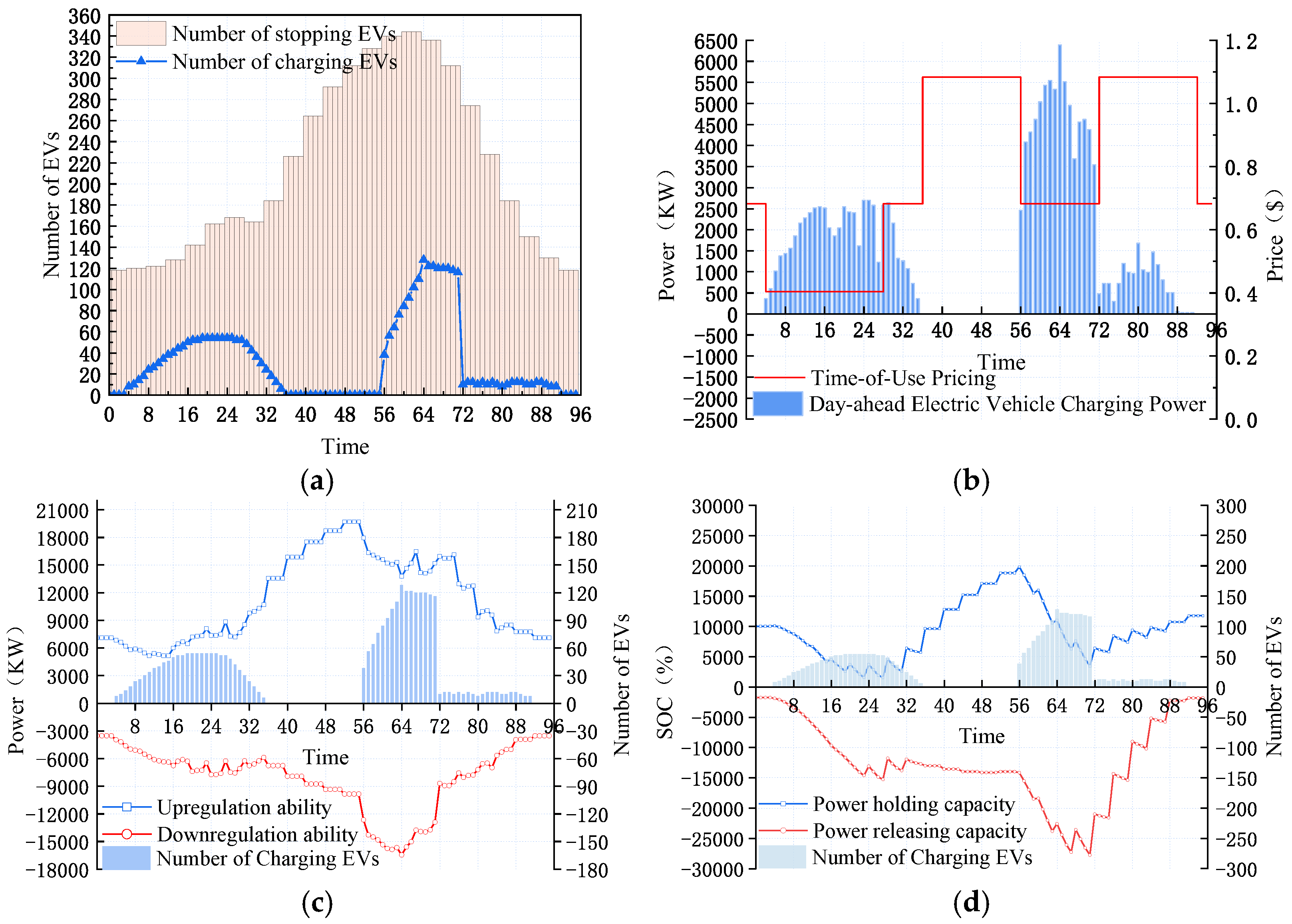

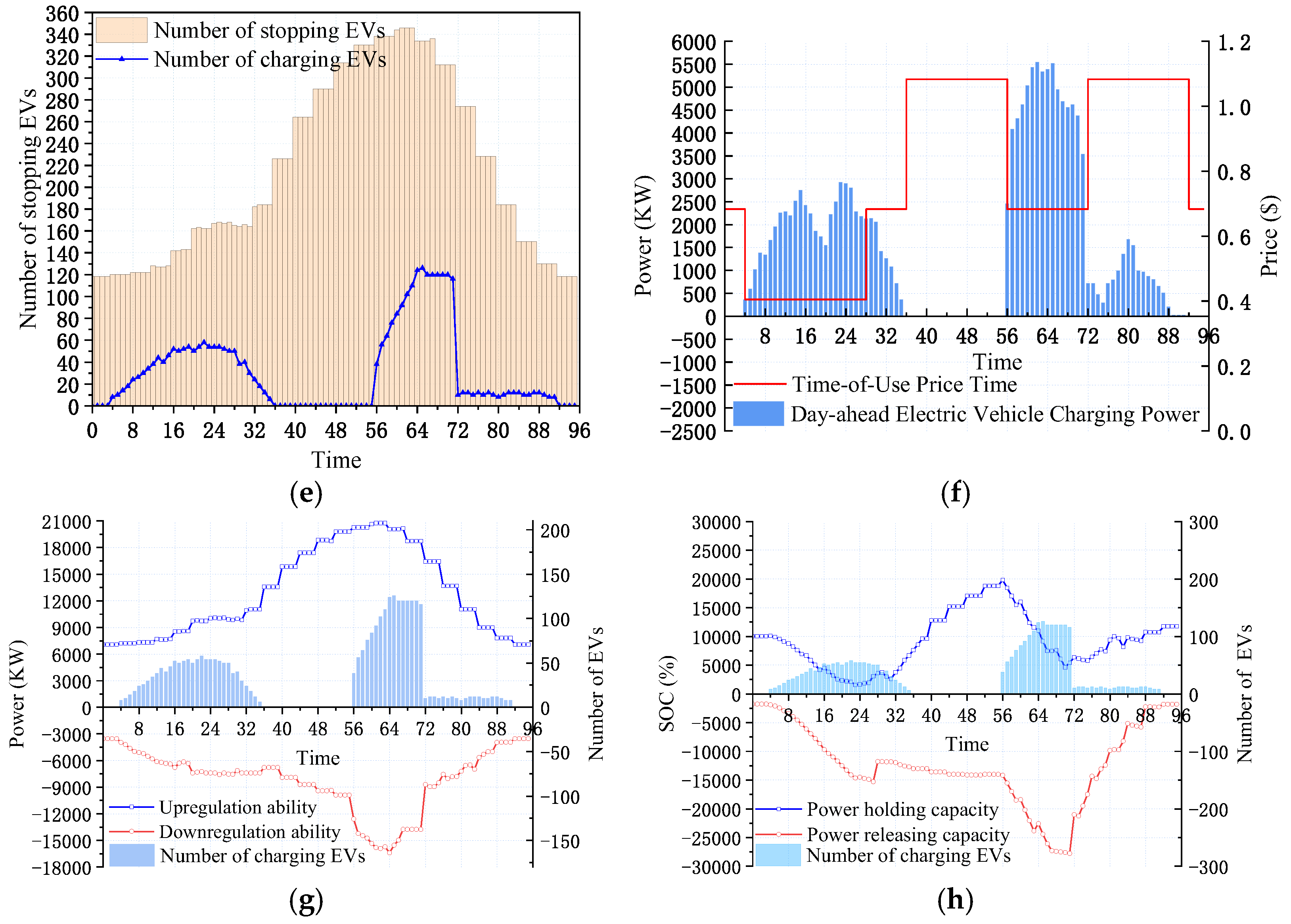

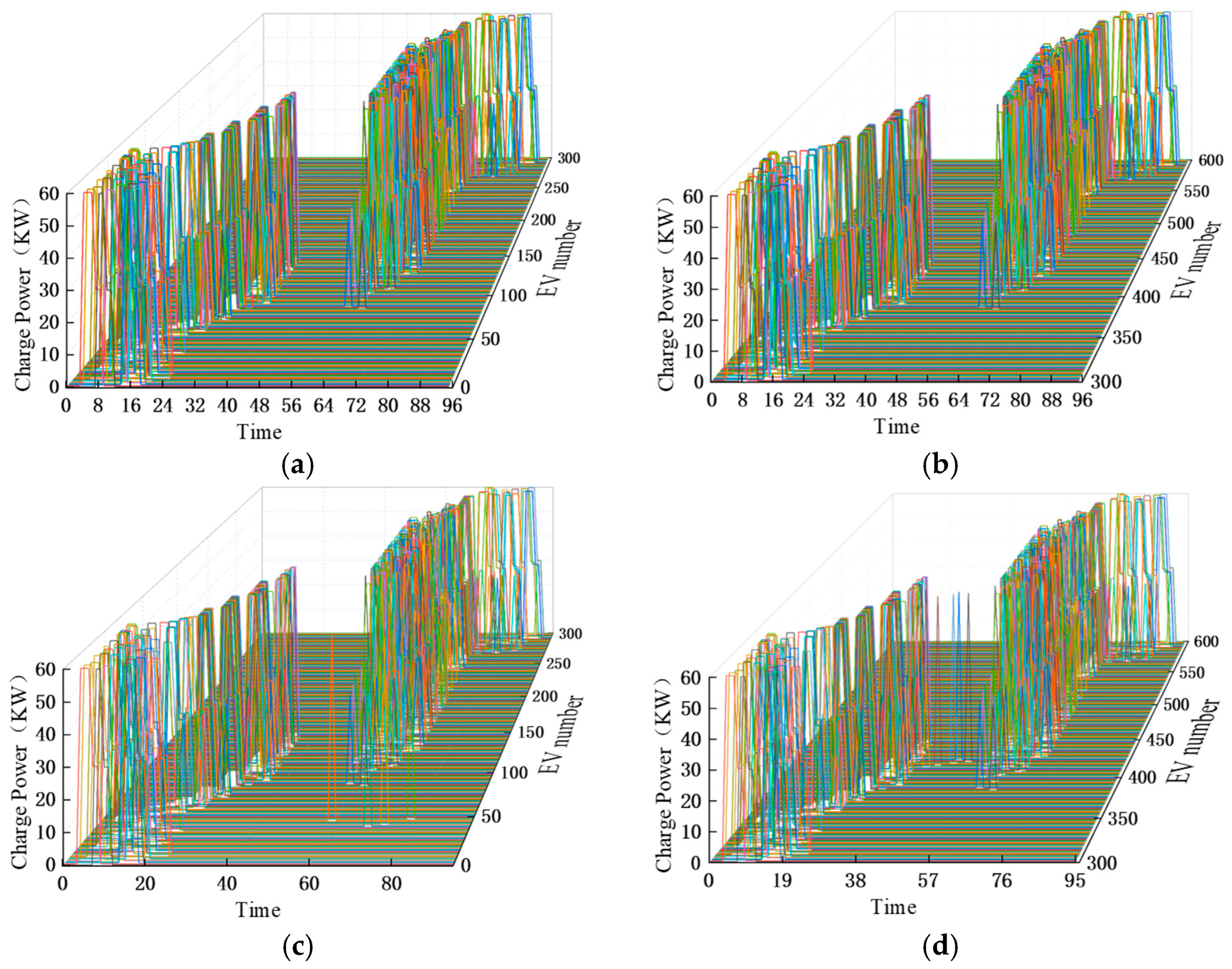

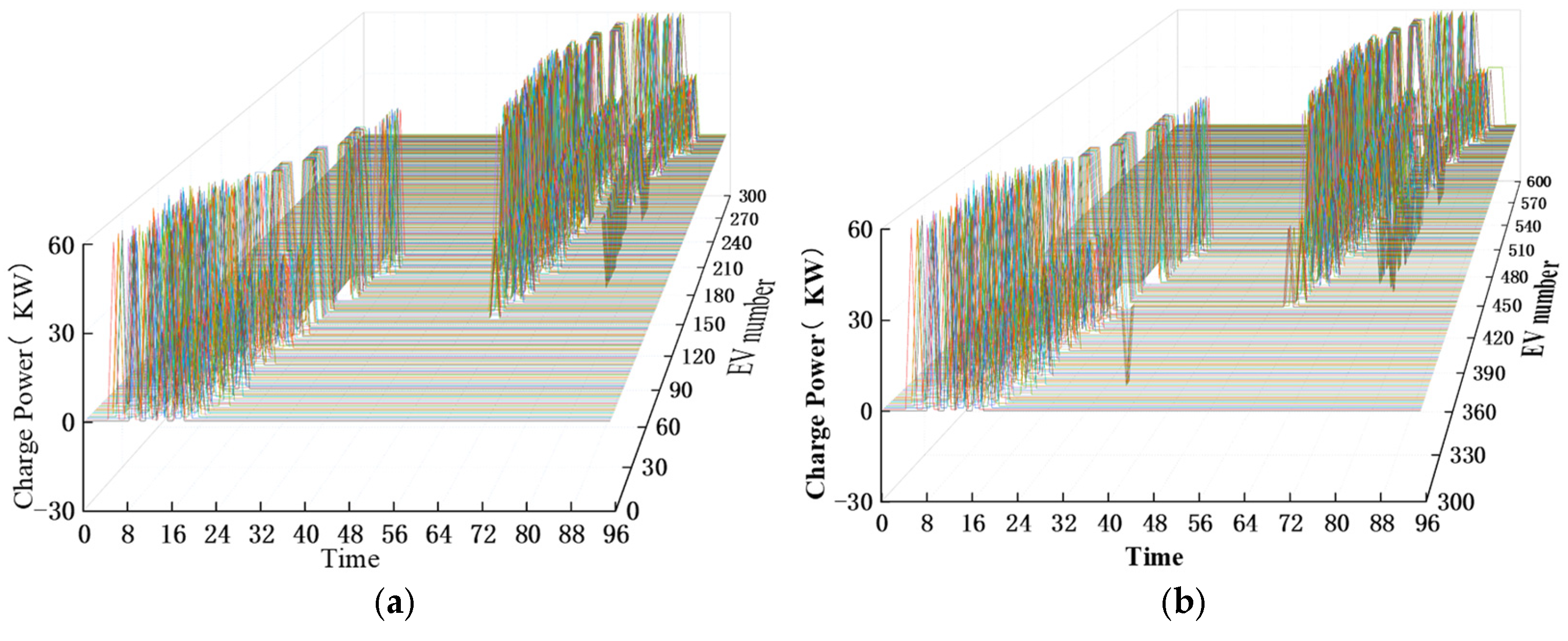

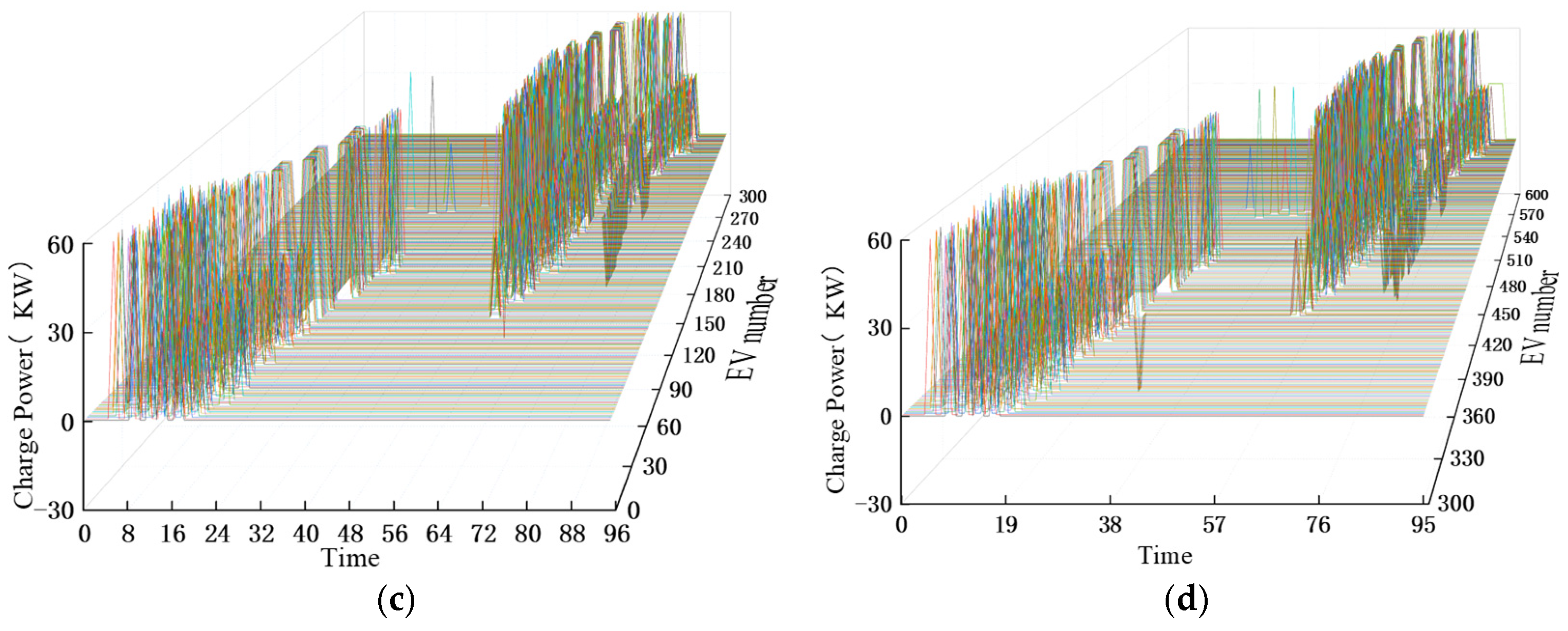

4.2. Analysis of the Results of the Day-Ahead Scheduling Stage

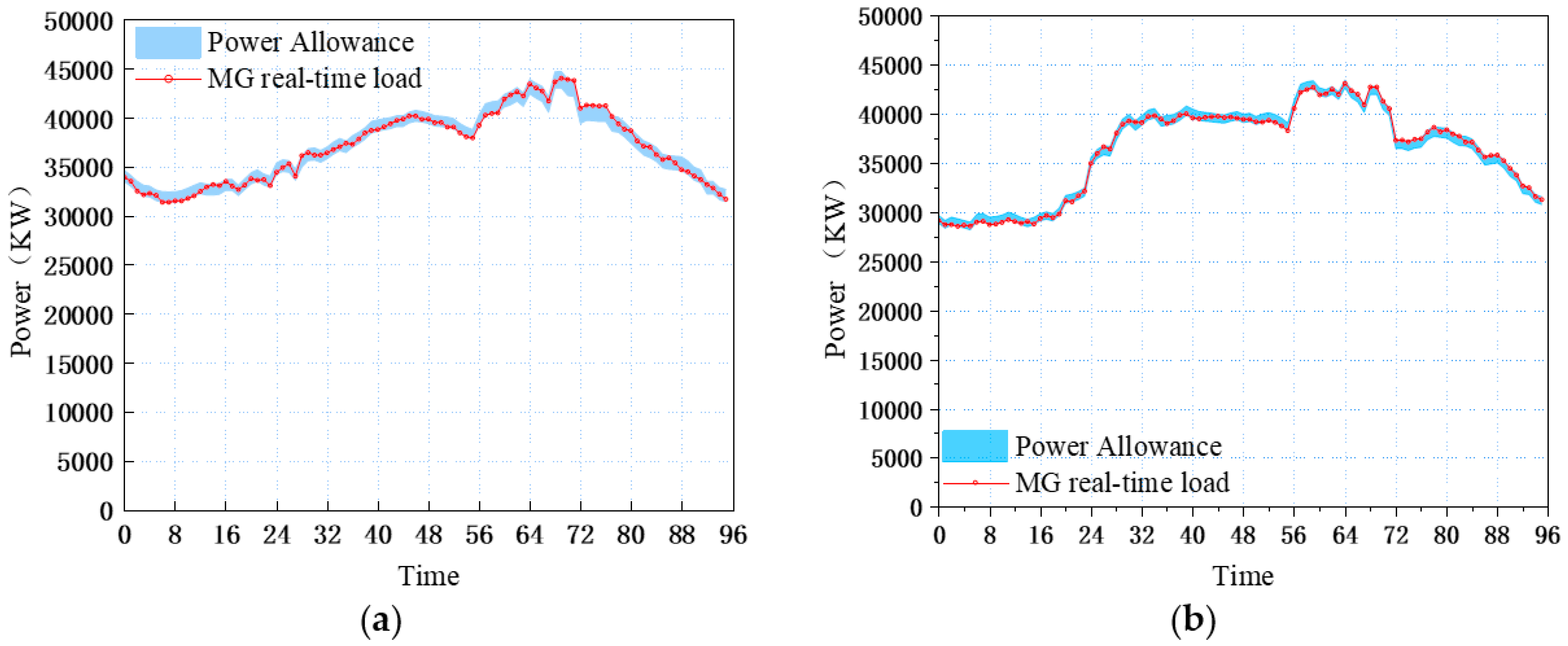

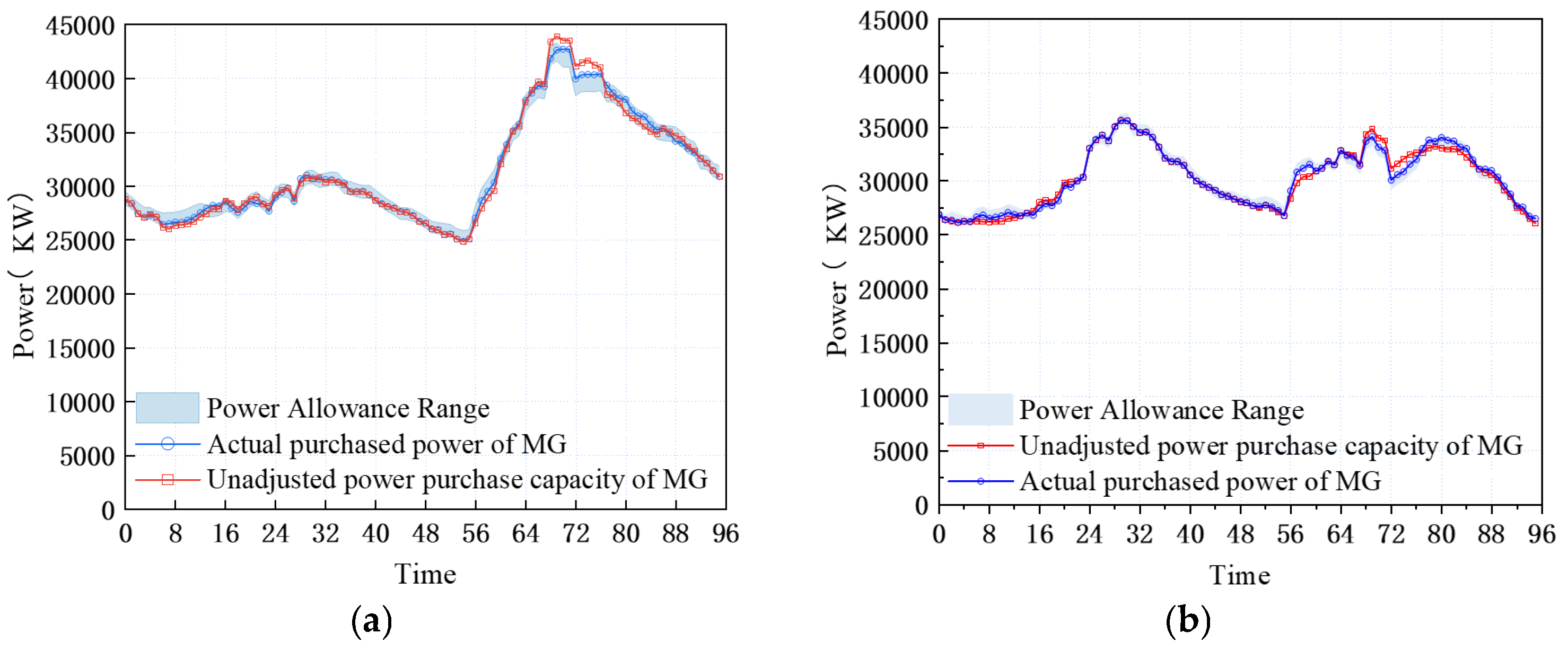

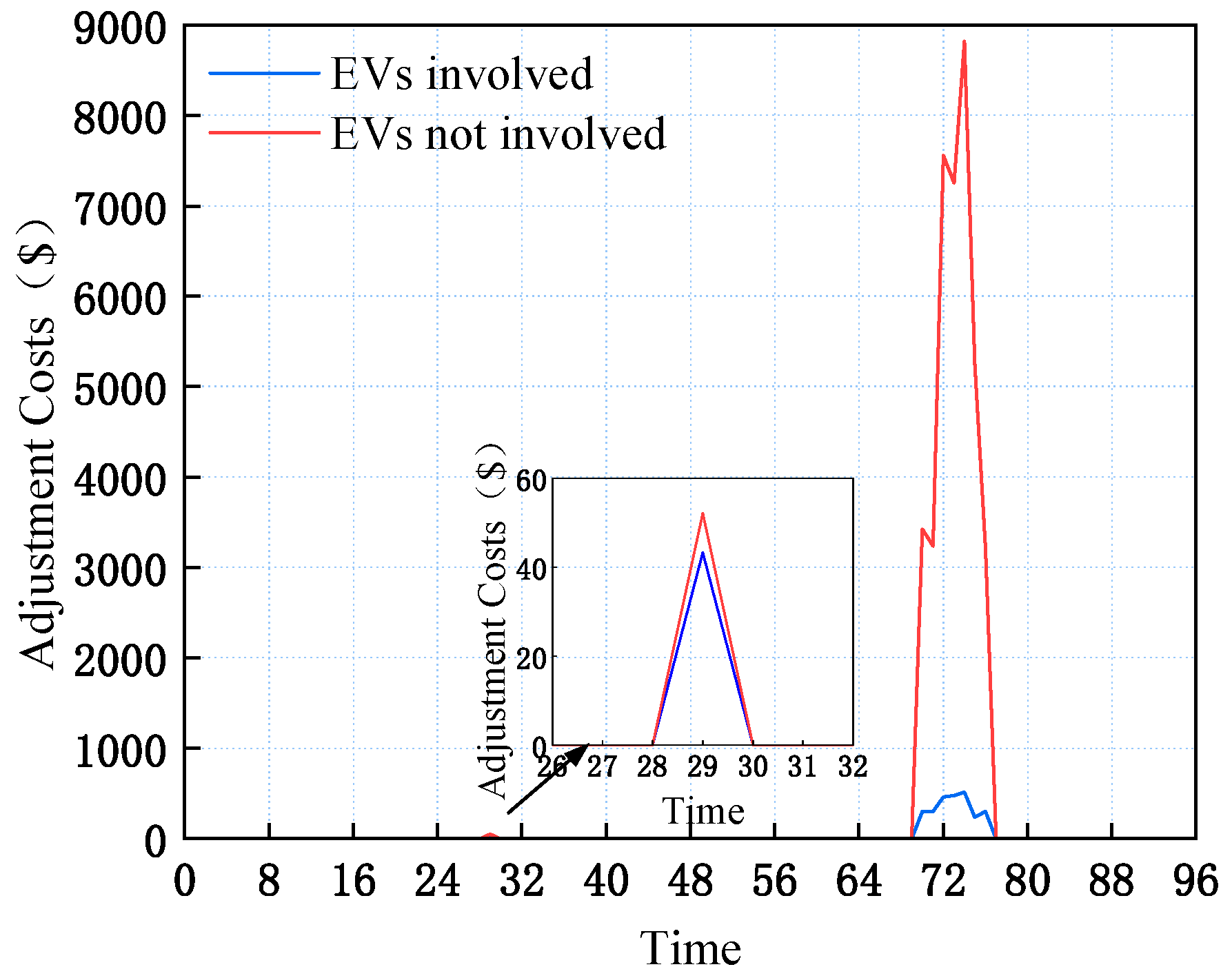

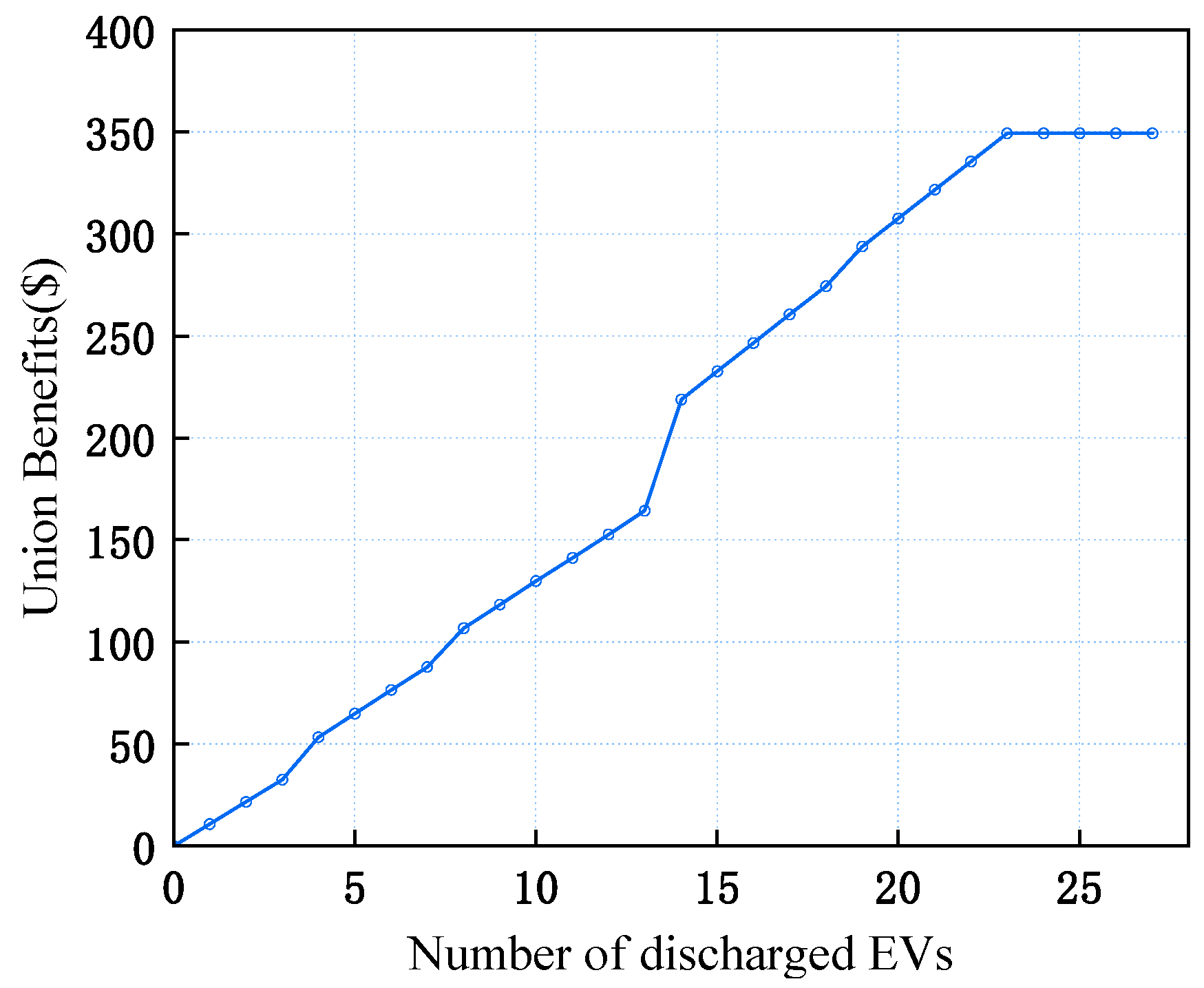

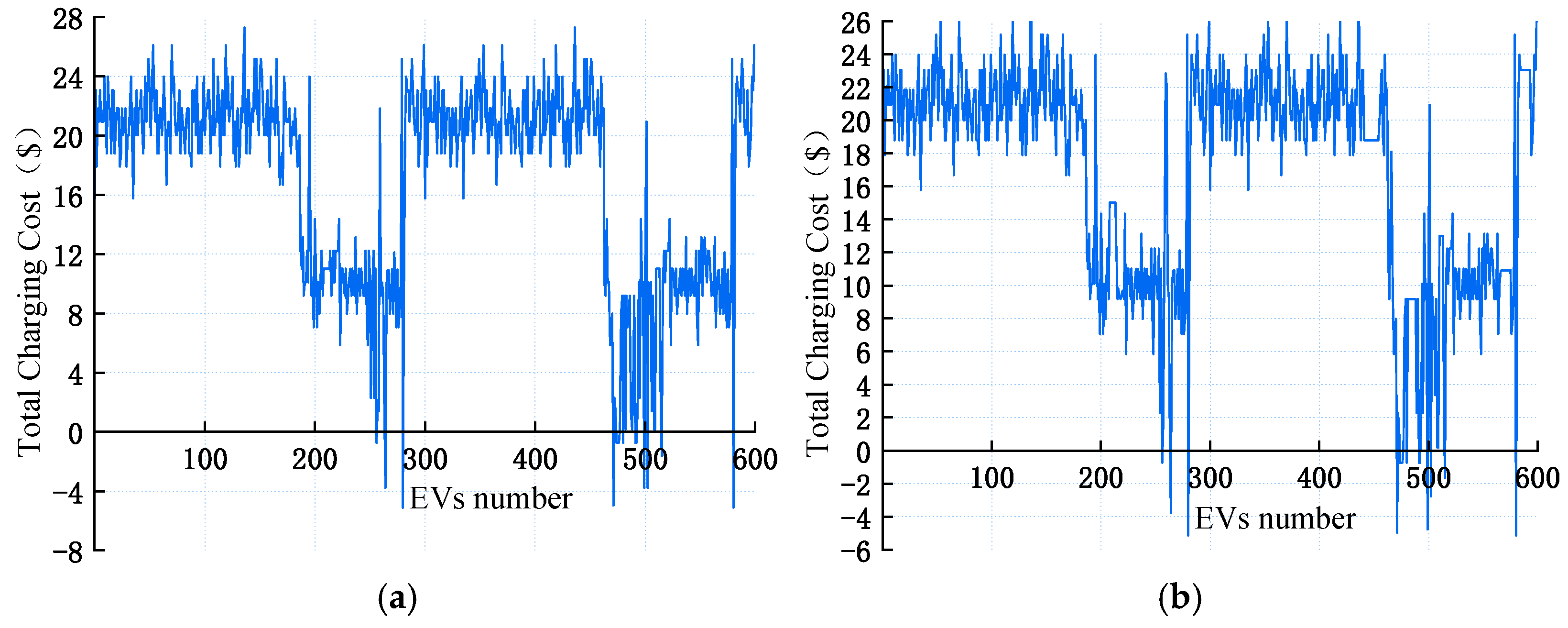

4.3. Analysis of the Results of the Real-Time Correction Stage

4.4. Comparative Experiments and Analysis

5. Summary and Prospects

5.1. Summary

- The method proposed in this paper verifies that EVs’ charging demand is concentrated in the valley of electricity consumption in the park, avoiding the “peak-on-peak” phenomenon; moreover, the method ensures the continuity of EV charging and protects the service life of EV batteries while reducing the load volatility of the MG.

- In the real-time phase, the EV scheduling model for travel risk proposed in this paper rationally arranges the charging and discharging demand of EVs according to their travel demand, thus significantly reducing the charging cost for EV users by 50% on average. In the best case, it not only meets the travel demand of EV users, but also ensures that EV users achieve profitability.

- The real-time phase of the real-time dynamic cooperative game decision-making model proposed in this paper not only reduced the cost of the real-time adjustment of the system, but also reduced the deviation from the previous day’s real-time plan while meeting the travel demands of all EV users, achieving a win–win situation for the system participants.

5.2. Real-World Applications

5.3. Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, J.R.; Alharthi, Y.Z.; Wang, Y.B.; Fatemi, S.; Ahmarinejad, A. A hierarchical structure for harnessing the flexibility of residential microgrids within active distribution networks: Advancing toward smart cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 106, 105398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terada, L.Z.; Magalhães, M.M.; Cortez, J.C.; Soares, J.; Vale, Z.; Rider, M.J. Multi-objective optimization for microgrid sizing, electric vehicle scheduling and vehicle-to-grid integration. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2025, 43, 101773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaksawi, O.; Fathy, R.; Daoud, A.A.; Abd El-Aal, R.A. Optimized load frequency controller for microgrid with renewables and EVs based recent multi-objective mantis search algorithm. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Xu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Sun, H.; Zhang, X. Day-ahead distributionally robust optimization-based scheduling for distribution systems with electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 14, 2837–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagnano, A.; De Tuglie, E.; Mancarella, P. Microgrids: Overview and guidelines for practical implementations and operation. Appl. Energy 2020, 258, 114039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.J.; Wei, W.; Bai, J.Y.; Mei, S.W. Long-term operation of isolated microgrids with renewables and hybrid seasonal-battery storage. Appl. Energy 2023, 349, 121628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.J.; Li, Y.; Cao, Y.J.; Tan, Y.; Peng, Y.J.; Zeng, Z.L.; Cao, L.H. Stochastic optimization of integrated energy system considering network dynamic characteristics and psychological preference. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Yin, X.; Chung, C.; Rayeem, S.; Chen, X.; Yang, H. Managing massive RES integration in hybrid microgrids: A data-driven quad-level approach with adjustable conservativeness. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 7698–7709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, V.; Singh, J.G.; Ongsakul, W. An efficient two stage stochastic optimal energy and reserve management in a microgrid. Appl. Energy 2015, 160, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqin, Z.Y.; Niu, D.X.; Wang, X.J.; Zhen, H.; Li, M.Y.; Wang, J.B. A two-stage distributionally robust optimization model for P2G-CCHP microgrid considering uncertainty and carbon emission. Energy 2022, 260, 124796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.H.; Zhang, B.Y.; Li, Q.Q.; Song, W.; Li, G.G. Robust distributed optimization for energy dispatch of multi-stakeholder multiple microgrids under uncertainty. Appl. Energy 2019, 255, 113845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Duan, J.D.; Wu, C.; Tian, Q.X. Risk-averse distributed optimization for integrated electricity-gas systems considering uncertainties of Wind-PV and power-to-gas. Renew. Energy 2024, 227, 120358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.F.; Wang, C.S.; Cao, Y.; Jia, H.J.; Zhang, Q.Z.; Yu, X.D. A CVaR-based risk assessment method for park-level integrated energy system considering the uncertainties and correlation of energy prices. Energy 2022, 247, 123549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Nojavan, S.; Lei, S.; Liang, X.D. Economic-environmental analysis of renewable-based microgrid under a CVaR-based two-stage stochastic model with efficient integration of plug-in electric vehicle and demand response. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 75, 103276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattaheian-Dehkordi, S.; Tavakkoli, M.; Abbaspour, A.; Mazaheri, H.; Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M.; Lehtonen, M. A transactive-based control scheme for minimizing real-time energy imbalance in a multiagent microgrid: A CVaR-based model. IEEE Syst. J. 2022, 16, 4164–4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.M.; Liang, R.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, B.W.; Xiang, S.; Liu, J.P.; Zhao, H.; Ackom, E. Distributionally robust optimal dispatch in the power system with high penetration of wind power based on net load fluctuation data. Appl. Energy 2022, 313, 118813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sora, J.; Serban, I.; Petreus, D. Enhancing microgrid operation through electric vehicle integration: A survey. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 64897–64912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.C.; Yu, H.; Shao, Z.Y.; Jian, L.N. Day-ahead bidding strategy for electric vehicle aggregator enabling multiple agent modes in uncertain electricity markets. Appl. Energy 2020, 280, 115977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Song, Y. Evaluation of achievable vehicle-to-grid capacity using aggregate PEV model. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 32, 784–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.Z.; Xu, Y.L.; Sun, H.B. Joint chance-constrained program based electric vehicles optimal dispatching strategy considering drivers’ response uncertainty. Appl. Energy 2024, 356, 122313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jia, Y.; Shi, M.; Xie, P.; Lai, C.S.; Li, K. A hybrid incentive program for managing electric vehicle charging flexibility. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 14, 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.Z.; Xu, Y.L.; Sun, H.B. Bilevel optimal coordination of active distribution network and charging stations considering EV drivers’ willingness. Appl. Energy 2024, 360, 122790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.L.; Li, P.P.; Ma, K.; Yang, B.; Yang, J. Robust energy management for industrial microgrid considering charging and discharging pressure of electric vehicles. Appl. Energy 2022, 325, 119846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.L.; Mao, Y.X.; Chen, X.S.; Xu, Y.H.; Wu, S.X. A multi-timescale energy scheduling model for microgrid embedded with differentiated electric vehicle charging management strategies. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaidi, A.A.; Farag, H.E.Z. Optimal design of V2G incentives and V2G-capable electric vehicles parking lots considering cost-benefit financial analysis and user participation. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2024, 15, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, M.S.; Lin, H.; Xie, S.; Dong, X.; Lin, Y.; Shiva, C.K.; Mbasso, W.F. An intelligent hybrid grey wolf-particle swarm optimizer for optimization in complex engineering design problem. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, M.S.; Raj, S.; Babu, R.; Kumar, S.; Sagrolikar, K. A hybrid moth–flame algorithm with particle swarm optimization with application in power transmission and distribution. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 6, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.Q.; Song, D.R.; Huang, L.S.; Chen, X.J.; Yang, J.; Dong, M.; Talaat, M.; Elkholy, M.H. Distributed energy management of electric vehicle charging stations based on hierarchical pricing mechanism and aggregate feasible regions. Energy 2024, 291, 130332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Li, S.; Liao, Q.; Xing, Q. Design of segmented boost constant voltage battery charger based on leakage transformer. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Robotics, Automation and Intelligent Control (ICRAIC), Zhangjiajie, China, 22–24 December 2023; pp. 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, K.; de Hoog, J.; Muenzel, V.; Suits, F.; Steer, K.; Wirth, A.; Halgamuge, S. Optimal operation of energy storage systems considering forecasts and battery degradation. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 9, 2086–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.F.; Zhao, B.X.; Zhang, X.H.; Fen, M.D. A day-ahead optimal operation strategy for integrated energy systems in multi-public buildings based on cooperative game. Energy 2023, 275, 127395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salyani, P.; Nourollahi, R.; Zare, K.; Razzaghi, R. A cooperative game approach for optimal resiliency-oriented scheduling of transactive multiple microgrids. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 89, 104358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wang, Z.W.; Liu, G.Y.; Chen, X.; Yuan, H.Y.; Wei, Y.L.; Li, F.X. A cooperative game approach for coordinating multi-microgrid operation within distribution systems. Appl. Energy 2018, 222, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.; Vale, Z. Costless renewable energy distribution model based on cooperative game theory for energy communities considering its members’ active contributions. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Huang, M.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, C.; Ai, Q. Optimisation Strategy for Electricity–Carbon Sharing Operation of Multi-Virtual Power Plants Considering Multivariate Uncertainties. Energies 2025, 18, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, B. A consortium blockchain-enabled secure and privacy-preserving optimized charging and discharging trading scheme for electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 1968–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.H.; Zhou, K.L.; Yang, S.L. Multi-objective optimal dispatch of microgrid containing electric vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 1572–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | EV1 | EV2 |

|---|---|---|

| Battery capacity (KW/h) | 75 | 75 |

| Charge/discharge power limit (KW) | 60/30 | 60/30 |

| Charge/discharge power efficiency | 0.97/0.97 | 0.97/0.97 |

| SoC upper/lower limits | 1/0 | 1/0 |

| Battery cycle life (cycles) | 1500 | 2000 |

| Maximum discharge depth | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Purchase/Recycling Price (USD) | 10,350/1400 | 8300/1400 |

| Confidence Level | 0.9 | 0.95 | 0.99 |

|---|---|---|---|

| RES operating costs (USD) | 50,967.51 | 50,967.51 | 50,967.51 |

| Power purchase costs (USD) | 566,328.27 | 573,865.38 | 596,476.69 |

| Penalty costs (USD) | 263,093.27 | 253,128.39 | 231,744.28 |

| Total system cost (USD) | 880,389.05 | 877,961.28 | 879,188.48 |

| Cost Type | With EV Participation | Without EV Participation |

|---|---|---|

| Intra-day system operational costs (USD) | 53,429.12 | 53,429.12 |

| Intra-day adjustment costs (USD) | 2655.09 | 32,335.81 |

| Intra-day power purchase costs (USD) | 574,084.98 | 574,084.98 |

| Total intra-day costs (USD) | 630,169.19 | 659,849.91 |

| Type of EV (Initial SoC = 40%) | Average Charging Cost on Day#1 (USD) | Average Charging Cost on Day#2 (USD) |

|---|---|---|

| Best-case EV user | −5.11 | −6.21 |

| Regular EV user | 16.96 | 18.74 |

| Temporary EV user | 35.98 | 35.98 |

| Indicator | Method #1 | Method #2 | Method #3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic indicators | Operational costs (USD) | 53,429.12 | 53,429.12 | 53,429.12 |

| Adjustment costs (USD) | 7272.73 | 6153.84 | 2655.09 | |

| Penalties (USD) | 0 | 112,867.13 | 0 | |

| Purchased electricity cost (USD) | 609,230.76 | 608,811.19 | 574,084.98 | |

| Total cost (USD) | 669,932.61 | 781,261.06 | 630,169.19 | |

| EV user satisfaction indicators | Travel demand satisfaction rate | 78.8 | 90.2 | 100 |

| Average SoC | 93.1 | 97.7 | 99.9 | |

| Method | Permeability | Real-Time Adjustment Costs (USD) | EV Charging Achievement Rate (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjustment Cost | Electricity Purchase Cost | Travel Demand Satisfaction Rate | Average SoC | ||

| Method #3 | 80% | 2920.599 | 574,084.98 | 95.6 | 94.2 |

| Method #3 | 100% | 2655.09 | 574,084.98 | 100 | 99.9 |

| Method #1 | 100% | 7272.73 | 669,932.61 | 93.1 | 78.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, J.; Dong, W.; Shen, B.; Zhang, J. Two-Stage Energy Dispatch for Microgrids Based on CVaR-Dynamic Cooperative Game Theory Considering EV Dispatch Potential and Travel Risks. Energies 2025, 18, 6105. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236105

Ma J, Dong W, Shen B, Zhang J. Two-Stage Energy Dispatch for Microgrids Based on CVaR-Dynamic Cooperative Game Theory Considering EV Dispatch Potential and Travel Risks. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6105. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236105

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Jianjun, Wei Dong, Baiqiang Shen, and Jingchen Zhang. 2025. "Two-Stage Energy Dispatch for Microgrids Based on CVaR-Dynamic Cooperative Game Theory Considering EV Dispatch Potential and Travel Risks" Energies 18, no. 23: 6105. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236105

APA StyleMa, J., Dong, W., Shen, B., & Zhang, J. (2025). Two-Stage Energy Dispatch for Microgrids Based on CVaR-Dynamic Cooperative Game Theory Considering EV Dispatch Potential and Travel Risks. Energies, 18(23), 6105. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236105