Abstract

A finite-element model of the direct-drive coreless permanent-magnet generator is used to simulate faults individually. Each fault case—rotor magnet demagnetization, a stator inter-turn short circuit, static eccentricity, and dynamic eccentricity—is introduced into the finite-element analysis (FEA) model separately, rather than in combination. For each isolated fault scenario, the stator current signals are processed using the Extended Park’s Vector Approach (EPVA) and the electromagnetic torque is examined in the frequency domain. The EPVA spectra and torque harmonics exhibit unique features for each fault type, allowing for clear discrimination among faults. These results demonstrate that modeling and analyzing faults one at a time yields distinct diagnostic signatures.

1. Introduction

High-efficiency, compact, and low-maintenance direct-drive permanent magnet synchronous generators (PMSGs) have become important in tidal, wave, and wind energy systems [1]. The C-GEN coreless PMSG, developed at the University of Edinburgh, uses C-shaped back-iron modules and a drum rotor with surface magnets to remove all iron from the stator. Unlike cogging and magnet-attraction forces, this open, air-cored topology provides large air gaps and high torque-to-mass ratio suitable for low-speed, re-usable applications. As an additional benefit of the modular stator of the C-GEN, the local loss of magnet strength (demagnetization) in one module causes circulating currents through adjacent healthy modules, thus providing a strong built-in signature for fault detection [2]. Such design advantages aside, coreless PM generators have critical reliability challenges. They operate in variable harsh environments and have faults [3]. Iron deficiency may cause some faults such as inter-turn short circuits to have small signatures in time and frequency spectra. Thus, early fault detection is a virtue, since undetected incipient issues will get worse and cause catastrophic failures [4]. Also, the failure modes of such machines are often related. For instance, an inter-turn winding short-circuit can lead to demagnetization of the rotor magnets if not addressed [5,6]. Such a situation of one fault triggering other faults highlights the need for a multi-fault holistic condition monitoring approach.

Previous research of coreless PM machines mostly dealt with individual fault mechanisms and their signatures [7,8,9]. The rotor demagnetization faults have received considerable attention, because even partial loss of magnet strength degrades output performance and, if unchecked, can cause severe damage. Classical detection methods like Motor current Signature Analysis (MCSA) [10] are applied for the diagnosis of demagnetization and for non-intrusive online monitoring of characteristic current harmonics. But some demagnetization scenarios (e.g., two non-adjacent magnets weakened) can escape detection in the current spectrum and give false negatives [11]. More specifically, almost no MCSA signature after nonadjacent magnet demagnetization, demonstrating the limitation of using phase-current analysis alone. Alternative electrical monitoring techniques are thus explored. Analyzing balanced components of three-phase voltage or current signals has shown that Park’s Vector Approach (PVA) [12,13] and its Extended variant (EPVA) [14] can detect stator winding asymmetries. Such approaches originating from induction machine diagnostics may reveal an inter-turn short-circuit fault (ITSC) by revealing telltale negative-sequence [15] or second-harmonic components in the machine voltage and current Park vectors [16]. Indeed, stator ITSC faults in multi-phase PM machines cause circulating currents and localized heating that accelerate insulation degradation and may ultimately induce magnet demagnetization when thermal stress becomes severe.

Other mechanical misalignment faults investigated in coreless PM generators include rotor eccentricity, which is either static (the rotor center is offset but fixed in space) or dynamic (the rotor wobbles so that the offset turns with the rotor). Even in toothless machines, eccentric rotors produce uneven air-gap flux density that, unchecked, causes magnetic pull, vibration, and possible rubbing damage [17,18]. The electromagnetic signatures of the static and dynamic eccentricity of a coreless direct-drive generator were investigated. It was found that the magnetic field and electrical signals of the machine are engraved differently by the dynamic and static eccentricity types. Dynamic eccentricity induces time-varying harmonics related to the rotor’s rotation, while static eccentricity induces mostly stationary asymmetry in the flux distribution. Such fault detection via conventional MCSA alone may be difficult as small static offsets may not produce large sidebands [19]. However, flux-based sensing has been sensitive to eccentricities: Researchers have captured field distortions due to rotor misalignment directly by monitoring the stray or air-gap flux [20,21,22]. A method based on two magnetically coupled search coils (one on the stator and one on the rotor) to detect all common faults in a coreless PMSG by inducing voltage signal signatures. It is showed that in their experiments, the search-coil approach distinguished static vs. dynamic eccentricity, as well as demagnetization and turn-fault conditions, and the induced voltage amplitude was related to fault severity. They demonstrate that magnetic flux analysis may be a rich diagnostic tool for magnetic and mechanical faults anomalies (flux imbalances, harmonics, etc.) that are omitted by pure electrical measurements [23]. Torque monitoring has been investigated [24,25,26]. Normally, a developing fault causes oscillations of electromagnetic torque or falls in average torque. Demagnetization and eccentricity in coreless machines induce characteristic torque ripple patterns in FEA simulations. Direct torque sensing on a large generator is difficult in practice; however, indirect torque estimation from speed fluctuations or power analysis may supplement other diagnostics. All the diagnostic techniques like current spectrum analysis, Park’s vector evaluation, stray flux sensing, and torque observation provide a different “view” of the condition of the machine.

In summary, this study investigates an isolated fault. Every fault—magnet demagnetization, inter-turn short-circuit, static eccentricity, and dynamic eccentricity—is introduced into the machine model individually and not simultaneously. Stator currents are analyzed via the EPVA spectrum for each fault case, and airgap torque is analyzed spectrally. Comparing the EPVA and torque features obtained for each fault shows that each fault produces a characteristic pattern in the current vector spectrum and the torque harmonics. Therefore, this method directs comparison of fault signatures. This one-fault-at-a-time methodology clearly separates fault types: Each scenario produces different EPVA spectral components and torque pulsation patterns that together provide complementary diagnostic information.

2. Model Development

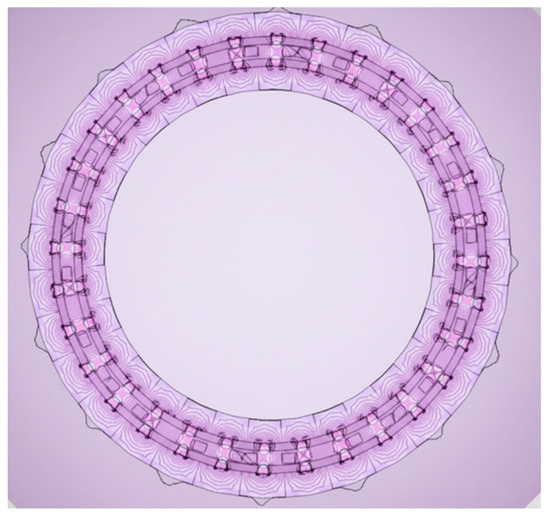

A 2D finite-element model of the radial-flux C-GEN has been built and solved to characterize the machine under healthy operation, utilizing magneto-static analysis software. The simulation of the model was carried out using transient analysis with rotational motion. The key model input parameters consisted of generator geometry, material properties, winding configuration, as well as operating conditions. Mesh refinement was applied in the air-gap regions for accuracy. The solver used was a time-stepping algorithm with a 6 kHz sampling frequency. A schematic cross-section with the associated magnetic flux density map is shown in Figure 1. Table 1 summarizes the rated and geometric parameters of the machine used in the model, and Table 2 compares simulated and measured performance for the same prototype. These discrepancies are small and in agreement with the expected measurement tolerances and material-property dispersion, indicating that the model is accurate enough for future fault studies. Beyond the nominal operating point, the model was also verified at several steady-state operating conditions spanning 0.75–1.25 p.u. torque and ±20% of rated speed. Across this range, the simulated phase currents, back-EMF, average torque, and loss distribution varied smoothly and remained within the same error bounds relative to measurements, confirming the model’s suitability for subsequent fault-case studies across operating conditions.

Figure 1.

FEA model of the C-GEN generator.

Table 1.

Generator properties.

Table 2.

FEA Verification.

3. Demagnetization

Demagnetization means a loss of remanence and, thereby, a reduction in the machine’s available air-gap flux, thereby decreasing its coercive capability. The fault can be uniform (roughly equal loss across a magnet) or localized/non-uniform (partial loss confined to edges or selected poles), and different observable in electrical and flux signatures, depending on the spatial pattern. Exit triggers may be thermal overstress, short-circuit-driven demagnetizing currents, external magnetic field exposure, and mechanical stresses or strains which increase local heating. Finite-element analyses indicate that demagnetization redistributes the air-gap field, depresses the fundamental back-EMF, injects characteristic sidebands, and increases torque ripple effects depending on magnet grade, temperature, and the uniform vs. localized nature of the loss [27,28]. Experiments support these trends and show that coordinated thermal management and robust, multi-observable fault detection (combining current/voltage features with flux or torque cues) are required to maintain PMSM performance and durability in applications [29,30].

The generator was evaluated during the staged demagnetization scenarios. A single magnet was first weakened to two severity levels: 25% and 50% loss of remanence. A pair of nonadjacent magnets separated by one bipolar pitch (one pole pair) was next demagnetized. Here, the symmetric severities (25% and 50%) and an asymmetric combination (25% and 50%) were applied to this two-magnet case, respectively.

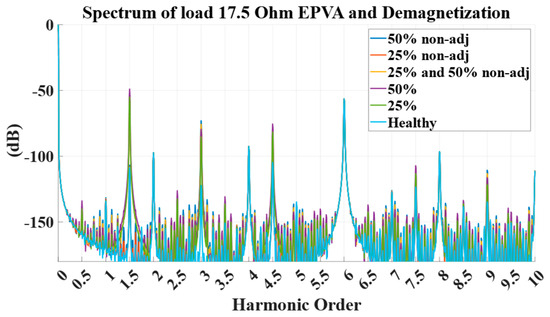

3.1. EPVA

Demagnetization results under different demagnetization scenarios are summarized in Figure 2 and Table 3. In general, the Extended Park’s Vector Approach (EPVA) departs clearly from the healthy pattern in faulted cases. However, when two non-adjacent magnets of equal severity are weakened (one pole-pair apart), the spatial symmetry introduces a partial cancelation of specific EPVA components: in our results, the lines at and are strongly attenuated. Consequently, the spectrum in that narrow region can resemble the healthy benchmark and, if those lines are used in isolation, may lead to a false negative. Even in this symmetric case, the third harmonic () of the Park vector increases with the demagnetisation level and fault severity and provides a complementary indicator. Therefore, demagnetization diagnosis should rely on the joint EPVA signature rather than any single spectral line.

Figure 2.

EPVA results for faulty cases (where green-1 magnet demagnetized by 25%; purple-1 magnet demagnetized by 50%; red-2 nonadjacent magnets demagnetized by 25%; blue-2 nonadjacent magnets demagnetized by 50% and yellow-1 magnet demagnetized by 25% and a nonadjacent by 50%) versus the healthy (cyan) with the generator phases connected to resistive loads of 17.5 Ω.

Table 3.

EPVA-demagnetization fault signatures amplitudes in decibels relative to the fundamental harmonic.

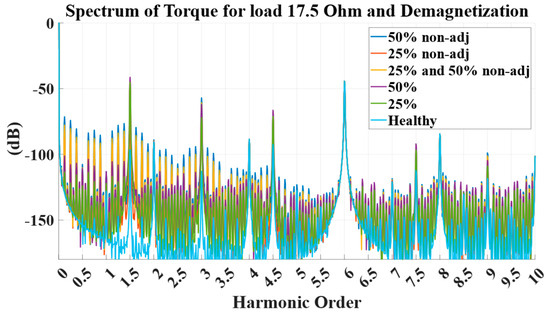

3.2. Torque Analysis

In machine condition monitoring, torque-based diagnostics have historically been underrepresented despite established studies in the literature [31]. The practical barrier in practice was the difficulty of instrumenting the shaft for direct torque measurement. In contrast, the electromagnetic torque can be indirectly estimated by synchronous acquisition of three-phase voltages and currents, which makes the method nonintrusive, fully online, and remote deployment-friendly. Here, we estimate and compare torque spectra in the cases examined (Figure 3). The interaction of the main rotor field with fault-induced stator MMFs gives rise to torque components at and . (≈40 Hz and 80 Hz here), corresponding to amplitudes given in Table 4. The lower-frequency signature rises more than 40 dB relative to healthy operation for incipient faults. When two adjacent magnets are demagnetized, the first signature is partially suppressed but not suppressed. Increasing fault severity by 50% further raises the spectral amplitude above the healthy baseline, enabling detection, although amplitude alone does not resolve the exact severity.

Figure 3.

Torque results for faulty cases (where green-1 magnet demagnetized by 25%, purple-1 magnet demagnetized by 50%, red-2 nonadjacent magnets demagnetized by 25%, blue-2 nonadjacent magnets demagnetized by 50% and yellow-1 magnet demagnetized by 25% and a nonadjacent by 50%) versus the healthy (cyan) with the generator phases connected to resistive loads of 17.5 Ω.

Table 4.

Torque-demagnetization fault signatures amplitudes in decibels relative to the fundamental harmonic.

4. Inter-Turn Short Circuit (ITSC)

The inter-turn short circuit (ITSC) occurs when the insulation between two or more turns of the same phase fails and creates a closed loop in the coil. The shorted coil is coupled to the air-gap field, and according to Faraday’s law, a voltage is applied across the shorted turns, producing a circulating current that may be several multiples of the rated phase current [32]. An ITSC may not cause immediate machine outage, but a high loop current causes local Joule heating and may induce additional vibrations; together, these effects accelerate insulation aging, raise fault severity, and can progress to phase-to-phase or phase-to-ground faults when left untreated [33]. In PMSMs, the short-circuit current field opposes the permanent magnet field. Together with the high local temperature, this opposition can induce irreversible demagnetization and reduce torque capability and efficiency [34].

For the ITSC study, the generator was examined over a matrix of severities and contact resistances. Fault severity was set by the number of shorted turns: 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9, and a higher-severity case with 41 turns (≈20%). For each severity, the contact resistance was swept across R_cont ∈ {0,0.1,0.5,1} Ω. For each combination, the interaction of shorted turns and contact resistance on the resulting fault currents and signatures was simulated.

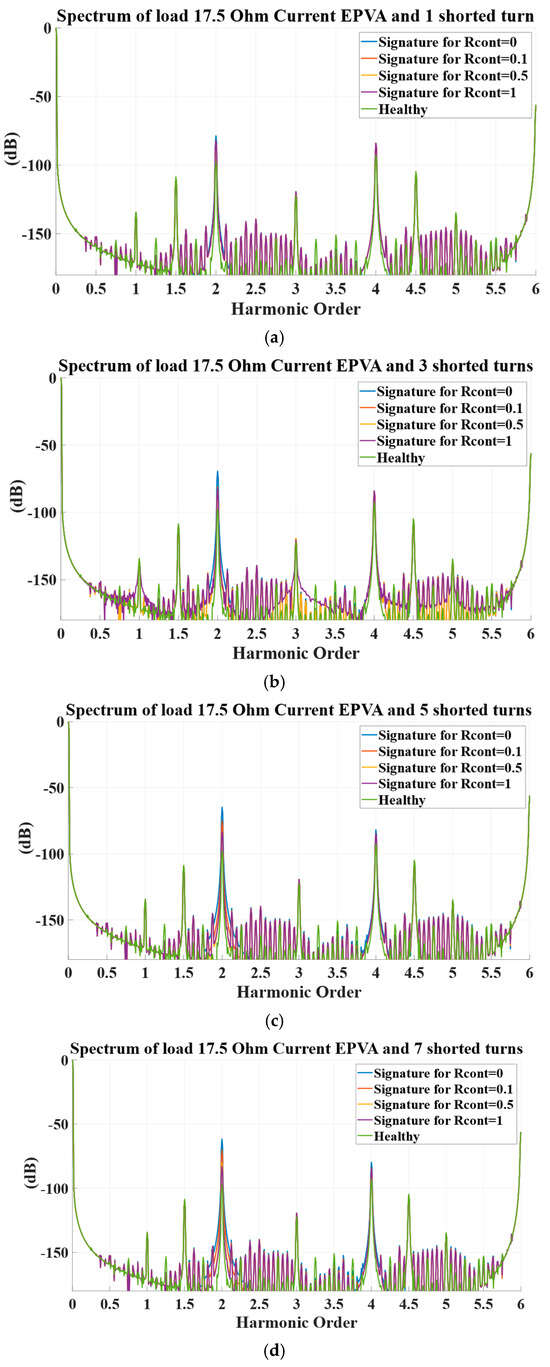

4.1. EPVA

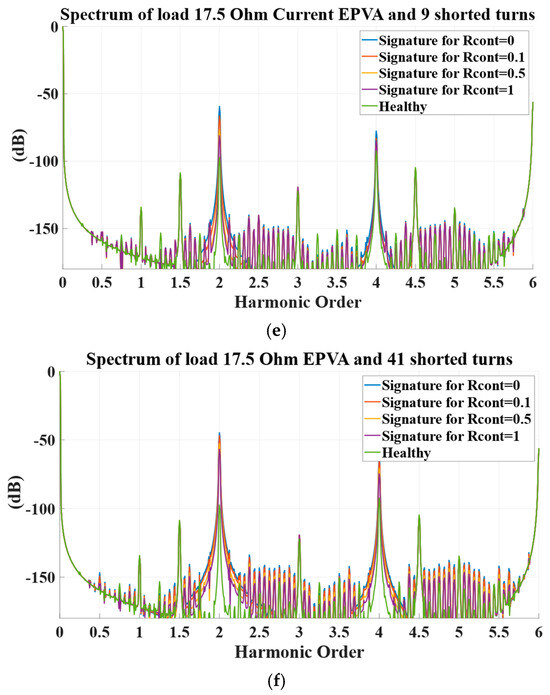

Although EPVA is usually cited as a strong indicator when spotting inter-turn shorts through the 2nd harmonic in the Park spectrum, our measurements indicate this marker collapses at extremely moderate severities either when just a couple of turns are involved or even every time a limited contact resistance limits the fault current. For cases with 1–3 shorted turns, the second-harmonic and fourth-harmonic level remains essentially indistinguishable from the healthy baseline (see Table 5 and Table 6 and Figure 4), confirming that even though EPVA tends to outperform conventional MCSA. The diagnostic cue is still weak at the lowest severities [35]. A definite increase in the quarter harmonic is just found at ≈20% severity (41 turns), exactly where its magnitude exceeds the wholesome resource of’ −84.70 dB. In a nutshell, while EPVA can, in principle, register early stator winding faults, and low-level ITSC usually produces false negatives as the second-harmonic component is throttled by the existence of any stator phases asymmetry. Efficient identification of such incipient cases generally requires complementary channels (e.g., torque-based or flux-based features), whereas EPVA stays effective for much more pronounced ITSC conditions in larger-scale tests [36].

Table 5.

EPVA second harmonic-ITSC fault signatures amplitudes in decibels relative to the fundamental harmonic.

Table 6.

EPVA fourth harmonic-ITSC fault signatures amplitudes in decibels relative to the fundamental harmonic.

Figure 4.

EPVA results for faulty cases (blue R_cont = 0, red R_cont = 0.1, orange R_cont = 0.5, purple R_cont = 1) versus the healthy (green) showing (a) 1 shorted turn, (b) 3 shorted turns, (c) 5 shorted turns, (d) 7 shorted turns, (e) 9 shorted turns, and (f) 41 (20%) shorted turns with the generator phases connected to resistive loads of 17.5 Ω.

4.2. Current Methods

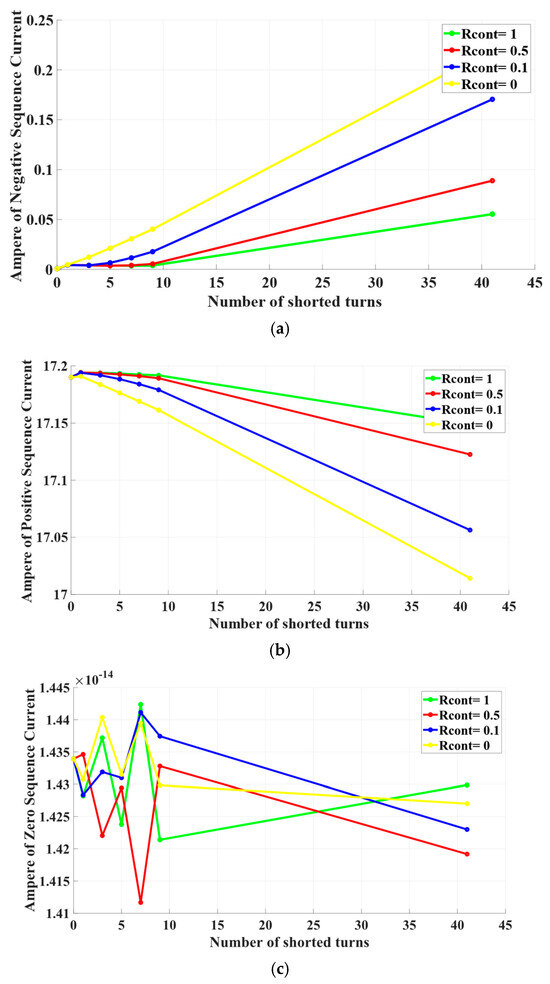

Current sequence methods are widely used methods, because of the simplicity in the implementation. The equations for the current of zero, positive, and negative sequence are showcased in Equation (1), where, , represent the zero, positive, and negative current, respectively, and , , indicate the phase currents, while a is given in Equation (2). In the healthy case, the positive-sequence current is equal to the current of the phase, while the currents of the zero and negative sequence equal zero. When the ITSC is applied these currents will be affected due to the three-phase asymmetry. In Figure 5, it the increase in the current of negative sequence is noticeable, while the positive current sequence decreases, with the decrease being negligible, and the zero-sequence current remains unaffected, possibly due to the absence of a neutral.

Figure 5.

Current results for faulty cases (yellow R_cont = 0, blue R_cont = 0.1, red R_cont = 0.5, green R_cont = 1) where (a) negative-sequence current, (b) positive-sequence current, (c) zero-sequence current.

4.3. Torque Analysis

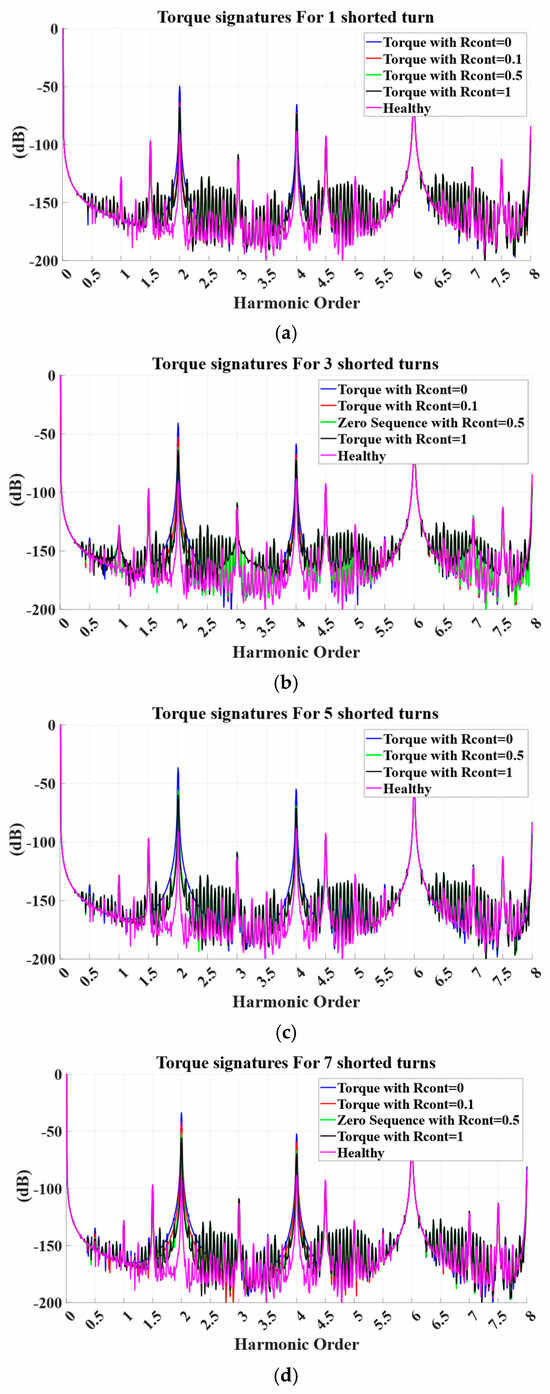

The ITSC will also increase the vibrations in the torque of the generator. Although the torque in real applications cannot be directly measured, the harmonics of the torque will be similar with the harmonics of the vibrations of the machine. As ITSC is a static fault, the harmonics that will be investigated are the 2nd- and 4th-order harmonics. From Figure 6 and Table 7, it can be seen that the amplitude of the 2nd-order harmonic increases significantly even at low severity faults. As shown in Table 8, the 4th-order harmonic also experiences a noticeable increase in its amplitude, but the increase is not significant at low-severity cases.

Figure 6.

Torque results for faulty cases (blue R_cont = 0, red R_cont = 0.1, green R_cont = 0.5, black R_cont = 1) versus the healthy (magenta) where (a) 1 shorted turn, (b) 3 shorted turns, (c) 5 shorted turns, (d) 7 shorted turns, (e) 9 shorted turns, and (f) 41 (20%) shorted turns.

Table 7.

Torque 2nd harmonic-ITSC fault signatures amplitudes in decibels relative to the fundamental harmonic.

Table 8.

Torque 4th harmonic-ITSC fault signatures amplitudes.

5. Eccentricity

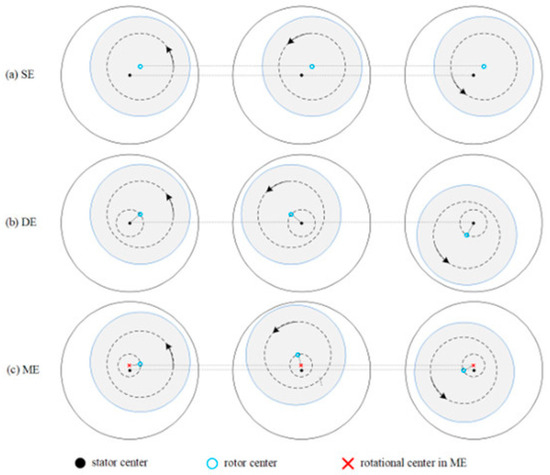

Eccentricity occurs when the misalignment between the rotational center of the rotor and stator center causes a circumferentially non-uniform air gap. This may result from manufacturing tolerances, bearing degradation, rotor deformation, or assembly errors. Three canonical forms are considered: static eccentricity (SE), dynamic eccentricity (DE), and mixed eccentricity (ME). In SE, the rotor center of rotation is offset from the stator center but coincident with the rotor geometric axis; the minimum air gap is fixed in the stator reference frame, and the air-gap nonuniformity is time-invariant (Figure 7a). In DE, the rotor spins about the stator center but its geometric center is offset; the minimum air-gap location travels with the rotor and the average air-gap length remains the nominal value (Figure 7b). ME incorporates both SE and DE components (Figure 7c). In the back-EMF [37] and phase currents, eccentricity induces characteristic harmonics and produces torque ripple and unbalanced magnetic pull (UMP) [38] and vibration [39]. In addition to this sensitivity, machines with slot/pole combinations satisfying (with p the pole-pair number and the number of stator slots) show a pronounced response: even small eccentricities increase cogging torque [40].

Figure 7.

Illustration of eccentricity faults (a) SE, (b) DE, and (c) ME [33].

5.1. Static Eccentricity

For the static eccentricity (SE) study, the generator was exercised with a fixed offset between rotor and stator centers at 20%, 30%, and 40% eccentricity ratios of nominal air gaps, respectively. The minimum air gap was always fixed in the stator frame, and the rotor turned about the displaced axis, thus permitting us to quantify SE-driven signatures at increasing severities.

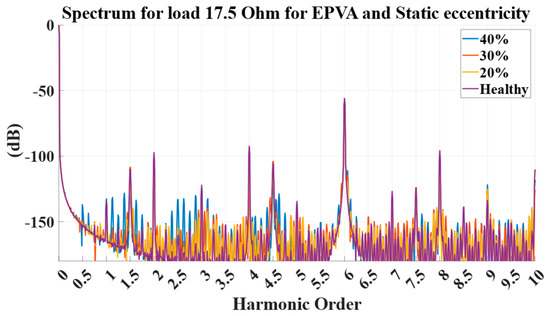

5.1.1. EPVA

When the EPVA is used to diagnose static eccentricity, it does not exhibit a unique or clearly recognizable pattern in the resulting spectral representation. Consequently, EPVA by itself cannot be used for a definitive diagnosis of static eccentricity, since there is no distinct indicator in the vector-domain data that correlates reliably with the fault, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

EPVA results for faulty cases (where yellow—20% static eccentricity, red—30% static eccentricity, blue—40% static eccentricity) versus those that are healthy (purple).

5.1.2. Torque Analysis

In the torque of the static eccentricity, as it is a static fault, the 2nd-harmonic order is expected to increase. In Figure 9, this increase can be observed, but the increase is insignificant and, therefore, the torque analysis cannot determine the static eccentricity in this generator.

Figure 9.

Torque results for faulty cases (where yellow—20% static eccentricity, red—30% static eccentricity, blue—40% static eccentricity) versus those that are healthy (purple).

5.2. Dynamic Eccentricity

For the dynamic eccentricity study, the same eccentricity ratios of 20%, 30%, and 40% were applied, but the offset was rotated with the rotor so that minimum air gap traveled one mechanical revolution per electrical period, synchronous with the rotor speed. This configuration preserved nominal average air gaps while maintaining time-varying permeance asymmetry, allowing for a direct comparison of DE-induced signatures across matching severities.

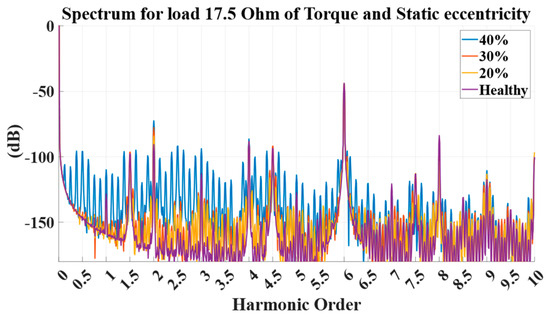

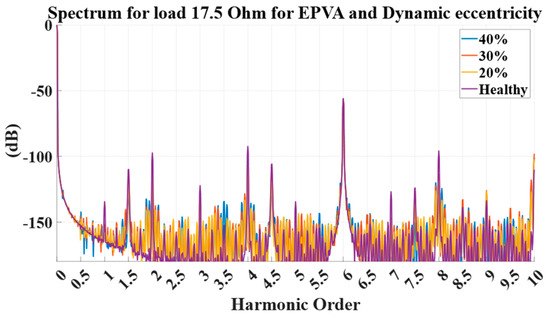

5.2.1. EPVA

The EPVA results for DE are shown in Figure 10. The healthy baseline (purple) dominates the second-harmonic component of the Park vector magnitude, and a direct amplitude comparison fails at low and moderate severities. This behavior is consistent with the coreless topology and with the drive non-ideals: in healthy conditions, inverter-related imbalance and measurement cross-coupling establish a high second-harmonic floor, while DE-induced negative-sequence content is low at low offsets. In this setup, the absolute second harmonic is thus not a reliable stand-alone indicator.

Figure 10.

EPVA results for faulty cases (where yellow—20% dynamic eccentricity, red—30% dynamic eccentricity, blue—40% dynamic eccentricity) versus those that are healthy (purple).

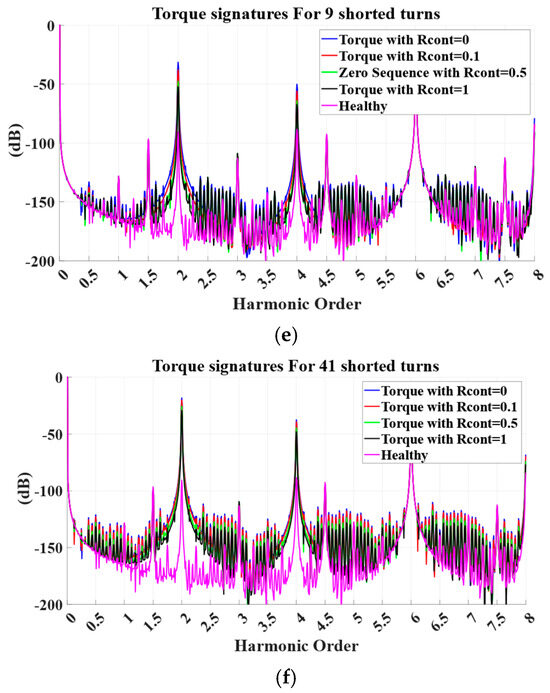

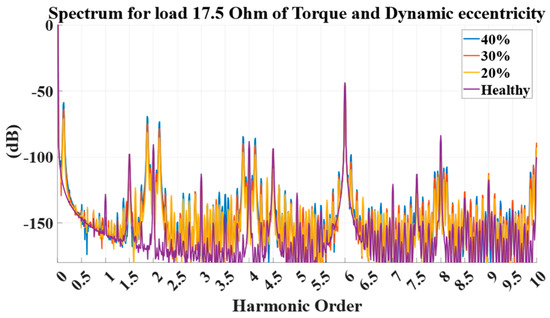

5.2.2. Torque Analysis

The harmonics of the torque are related to the harmonics of the stator and the rotor. Due to the dynamic nature of the fault, the harmonics of interest are the ones that are corresponding to the frequencies: . From Figure 11 and Table 9, a significant increase in these harmonics can be observed during faulty operation. Furthermore, these harmonics are different from the harmonics that are induced due to the other dynamic fault, which is non-uniform demagnetization, meaning that these faults can be identified.

Figure 11.

Torque results for faulty cases (where yellow—20% dynamic eccentricity, red—30% dynamic eccentricity, blue—40% dynamic eccentricity) versus those that are healthy (purple).

Table 9.

Torque analysis-DE fault signatures amplitudes in decibels relative to the fundamental harmonic.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This study analyzed four faults—demagnetization, inter-turn short circuit (ITSC), static eccentricity (SE), and dynamic eccentricity (DE)—individually in a direct-drive coreless PMSG (C-GEN) using FEA, extracting diagnostic features from the Extended Park’s Vector Approach (EPVA) and the electromagnetic torque spectrum. Across all single-fault cases, each fault produced a repeatable, fault-specific combination of EPVA harmonics and torque ripples, enabling clear separation without recourse to MCSA or flux sensors. Method effectiveness is fault-dependent: EPVA is most sensitive to electrical asymmetries—demagnetization strengthens the DC and 2× components, while ITSC elevates the 2× (negative-sequence) marker—whereas torque analysis is most discriminative for mechanical misalignment, with SE and DE imprinting dominant 1× f_rot pulsations (DE being the strongest and most consistent). These trends are confirmed quantitatively in Table 10, where EPVA yields the highest detection margins for demagnetization and ITSC, and torque yields the highest margins for SE and DE.

Table 10.

Comparison of different fault-detection approaches.

Practical integration strategy: For electrical faults (demagnetization, ITSC), prioritize EPVA; for eccentricity (SE/DE), prioritize torque. In deployment, use baseline-normalized thresholds: (i) flag electrical when EPVA DC/2× rises while torque 1× remains near baseline; (ii) flag eccentricity when torque 1× rises with negligible EPVA change; (iii) when both channels increase, discriminate by EPVA pattern (DC + 2× → demagnetization; 2× without DC → ITSC) and by torque characteristics (SE/DE separated by the magnitude/consistency of the 1× f_rot component per Table 10). Joint use of EPVA and torque thus provides the most robust diagnosis for coreless PMSGs.

Future work will translate the framework to real-time implementation with (i) baseline-normalized EPVA indices that suppress healthy second-harmonic floors, (ii) multi-sensor flux layouts (e.g., zero-sequence flux probes for SE) with placement optimized for coreless topologies, and (iii) torque-estimation pipelines hardened against inverter ripple. We will also investigate mixed and temporally evolving faults, thermo-electromagnetic co-simulation for prognostics, and lightweight data fusion (e.g., Bayesian or physics-informed ML) to set adaptive thresholds under speed/load variations and component tolerances. Additional experimental campaigns on larger prototypes will be used to quantify uncertainty, refine decision metrics, and assess the long-term stability of the proposed indicators. While this paper establishes fault-specific EPVA/torque signatures under isolated faults, most composite cases remain distinguishable because the dominant indicators for ITSC, demagnetization, and eccentricity occupy different spectral features. An identified exception is demagnetization vs. dynamic eccentricity, where partial overlap motivates a dedicated mathematical separation (EPVA sequence-harmonic decoupling and torque-harmonic ratioing). This compound-fault analysis will be reported in a subsequent article. Current-based methods require three current measurement sensors, which can also be used for the control system of the PWM inverter, which limits the computational burden. Although torque cannot be directly measured in real-life applications, the harmonics of the torque will be induced in the vibrations of the generator; therefore, a vibration sensor is required, making this method harder to implement than the current-based methods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., N.G. and M.M.; Methodology, A.S., M.S. and K.N.G.; Software, A.S. and M.S.; Validation, N.G. and M.S.; Formal analysis, A.S., N.G. and K.N.G.; Investigation, N.G.; Data curation, N.G.; Writing—original draft, A.S., M.M. and K.N.G.; Supervision, M.M. and K.N.G.; Funding acquisition, M.M. and K.N.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by the EU HORIZON and UKRI project entitled: “MEGA PTO WAVE”, EU HORIZON project ID: 101147321.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Koptjaev, E.; Cardoso, A.J.M. A New Brushless Non-salient Pole Generator with Multi-pole Rotor for Direct-drive Wind Turbines. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Ural Conference on Electrical Power Engineering (UralCon), Magnitogorsk, Russian Federation, 29 September–1 October 2023; pp. 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Keysan, O.; Mueller, M.; McDonald, A.; Hodgins, N.; Shek, J. Designing the C-GEN Lightweight Direct Drive Generator for Waveand Tidal Energy. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2012, 6, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stander, J.N.; Venter, G.; Kamper, M.J. Review of direct-drive radial flux wind turbine generator mechanical design. Wind. Energy 2012, 15, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkiolekas, N.; Sergakis, A.; Mueller, M.; Gyftakis, K.N. Analysis and Diagnosis of ITSC in Dual Rotor Air-Cored PMSG-Parallel Connected Stator Coils. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Symposium on Diagnostics for Electric Machines, Power Electronics and Drives (SDEMPED), Dallas, TX, USA, 24–27 August 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Kim, K.T.; Hur, J. Finite-Element Analysis of the Demagnetization of IPM-Type BLDC Motor with Stator Turn Fault. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2014, 50, 889–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riera-Guasp, M.; Antonino-Daviu, J.A.; Capolino, G.-A. Advances in Electrical Machine, Power Electronic, and Drive Condition Monitoring and Fault Detection: State of the Art. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 1746–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, J.; Bazrafshan, M.A.; Tabarniarami, Z. Demagnetisation Fault Analysis and Diagnosis Based on Different Methods in Permanent Magnet Machines—An Overview. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2024, 18, 1860–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Jeong, H.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.W. Detection and Classification of Demagnetization and Interturn Short Faults of IPMSMs. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 9433–9441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, K.; Wang, D.; Huang, W.; Hu, J. Research on Fault Indicator for Integrated Fault Diagnosis System of PMSM Based on Stator Tooth Flux. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2024, 12, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, R.Z.; Strangas, E.G. On the Accuracy of Fault Detection and Separation in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines Using MCSA/MVSA and LDA. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2016, 31, 924–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergakis, A.; Skarmoutsos, G.A.; Mueller, M.; Gyftakis, K.N. Non-Adjacent Demagnetisation Detection in Direct-Drive Permanent Magnet Generators for Renewable Energy Systems. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2025, 19, e70085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasid, S.A.; Gyftakis, K.N.; Mueller, M. Comparative Investigation of Three Diagnostic Methods Applied to Direct-Drive Permanent Magnet Machines Suffering from Demagnetization. Energies 2023, 16, 2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.M.; Cruz, S.; Fonseca, D. Inter-turn stator winding fault diagnosis in three-phase induction motors, by Park’s vector approach. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 1999, 14, 595–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, D.S.B.; Santos, C.M.C.; Cardoso, A.J.M. Stator Faults Modeling and Diagnostics of Line-Start Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2020, 56, 2590–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Du, Y.; Habetler, T.G.; Lu, B. A Survey of Condition Monitoring and Protection Methods for Medium-Voltage Induction Motors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2011, 47, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drif, M.; Cardoso, A.J.M. Stator Fault Diagnostics in Squirrel Cage Three-Phase Induction Motor Drives Using the Instantaneous Active and Reactive Power Signature Analyses. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2014, 10, 1348–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, P.; He, S.; Huang, J. A Review of Modeling and Diagnostic Techniques for Eccentricity Fault in Electric Machines. Energies 2021, 14, 4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkroost, L.; Druant, J.; Vansompel, H.; De Belie, F.; Sergeant, P. Performance Degradation of Surface PMSMs with Demagnetization Defect under Predictive Current Control. Energies 2019, 12, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, J.-H.; Kang, J.-K.; Hur, J. Static and Dynamic Eccentricity Faults Diagnosis in PM Synchronous Motor Using Planar Search Coil. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 9291–9300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehya, H.; Nysveen, A.; Antonino-Daviu, J.A. Advanced Fault Detection of Synchronous Generators Using Stray Magnetic Field. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 11675–11685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehya, H.; Nysveen, A.; Nilssen, R.; Liu, Y. Static and Dynamic Eccentricity Fault Diagnosis of Large Salient Pole Synchronous Generators by Means of External Magnetic Field. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2021, 15, 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Ma, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; He, Y.; Shen, Z.; Ji, Z.; Wang, P. Analytical Calculation of Stray Magnetic Field in Interior Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Under Static Eccentricity Considering Nonlinear and Non-Uniform Magnetic Saturation. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2024, 61, 8200411. [Google Scholar]

- Skarmoutsos, G.A.; Gyftakis, K.N.; Ab Rasid, S.; Mueller, M. General Diagnostics in Direct-Drive Permanent-Magnet Synchronous Generators Using Two Magnetically-Coupled Search-Coils. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 60, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsanullah, K.; Panda, S.K.; Shanmukha, R.; Nadarajan, S. Inter-turns fault diagnosis for surface permanent magnet based marine propulsion motors. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 2nd Annual Southern Power Electronics Conference (SPEC), Auckland, New Zealand, 5–8 December 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, Z.; Lee, S.-T.; Hur, J. A Torque Angle-Based Fault Detection and Identification Technique for IPMSM. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2020, 56, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Mao, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J. A Fault Diagnosis Method Based on an Improved Deep Q-Network for the Interturn Short Circuits of a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 3870–3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Moraes, T.J.; Semail, E.; Nguyen, N.-K. Demagnetization analysis of an open-end windings 5-phase PMSM under transistor short-circuit fault. In Proceedings of the IECON 2019—45th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Lisbon, Portugal, 14–17 October 2019; pp. 6206–6211. [Google Scholar]

- Garaei, S.; Lai, C.; Iyer, L.V. Comparative Analysis of 2D and 3D Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Models Under Demagnetization Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2024 AEIT International Annual Conference (AEIT), Trento, Italy, 25–27 September 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, G.F.; Bojoi, A.; Pescetto, P.; Ferrari, S.; Peretti, L.; Pellegrino, G. Active Short-Circuit Strategy for PMSMs Enabling Bounded Transient Torque and Demagnetization Current. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 109001–109011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Quan, L.; Jiang, M. Anti-Demagnetization Capability Research of a Less-Rare-Earth Permanent-Magnet Synchronous Motor Based on the Modulation Principle. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2020, 57, 8200706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-C.; Yang, S.-C. Permanent-Magnet Machine Flux andTorque Response Under the Influence of Turn Fault. IEEE Trans-Actions Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzysztofiak, M.; Skowron, M.; Orlowska-Kowalska, T. Analysis of the Impact of Stator Inter-Turn Short Circuits on PMSM Drive with Scalar and Vector Control. Energies 2020, 14, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergakis, A.; Salinas, M.; Gkiolekas, N.; Gyftakis, K.N. A Review of Condition Monitoring of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines: Techniques, Challenges and Future Directions. Energies 2025, 18, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Hang, J.; Ding, S.; Wang, Q. Common Predictive Model for PMSM Drives with Interturn Fault Considering Torque Ripple Suppression. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 9, 4071–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Liu, K.; Hu, W.; Peng, X.; Chen, Y.; Ding, R. Short-Time Adaline Based Fault Feature Extraction for Inter-Turn Short Circuit Diagnosis of PMSM via Residual Insulation Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 3103–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S.; Cardoso, A. Stator winding fault diagnosis in three-phase synchronous and asynchronous motors, by the extended Park’s vector approach. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2001, 37, 1227–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liang, S.; Li, W.; Liang, H.; Wang, C. Faults and Diagnosis Methods of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrell, D.G.; Hsieh, M.-F.; Guo, Y. Unbalanced Magnet Pull in Large Brushless Rare-Earth Permanent Magnet Motors with Rotor Eccentricity. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2009, 45, 4586–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogidi, O.O.; Barendse, P.S.; Khan, M.A. Detection of Static Eccentricities in Axial-Flux Permanent-Magnet Machines with Concentrated Windings Using Vibration Analysis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2015, 51, 4425–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, Z.-Q.; Azar, Z.; Clark, R.; Wu, Z. Fault Detection of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines: An Overview. Energies 2025, 18, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).