Optical Analysis of a Hydrogen Direct-Injection-Spark-Ignition-Engine Using Lateral or Central Injection

Abstract

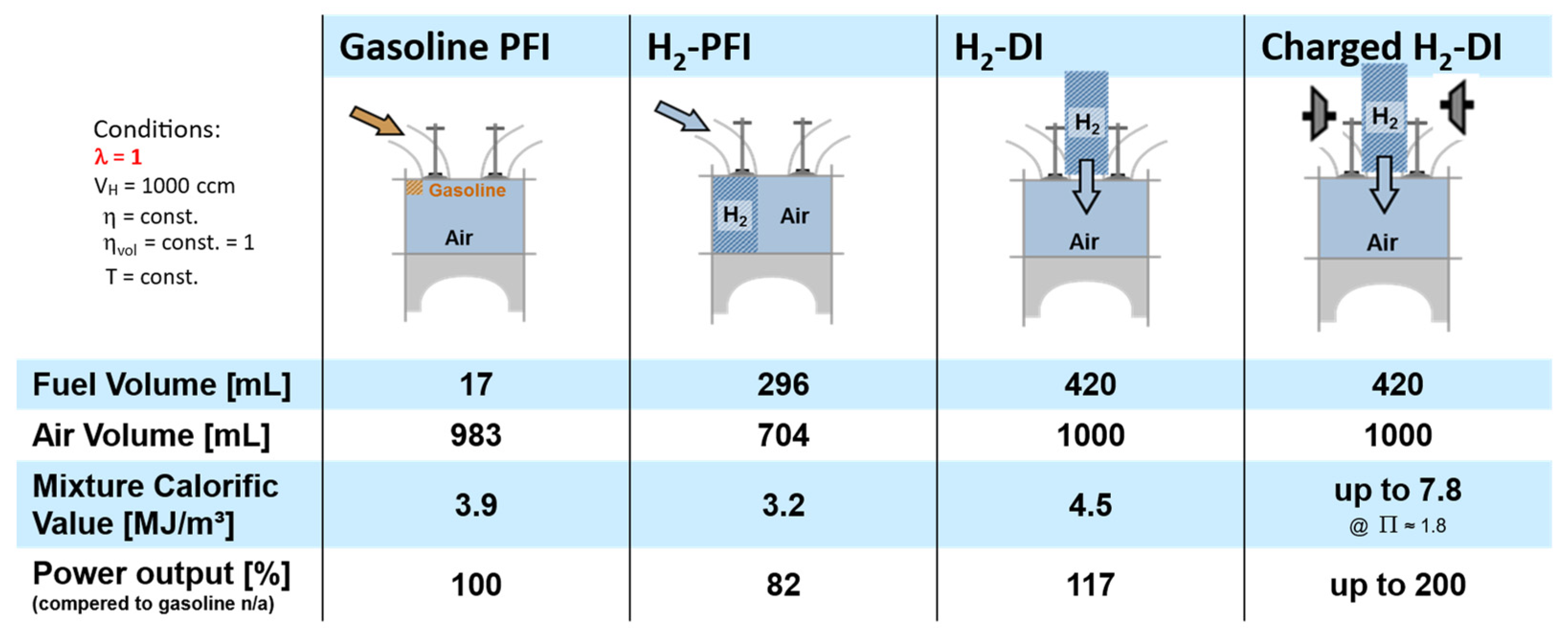

1. Introduction

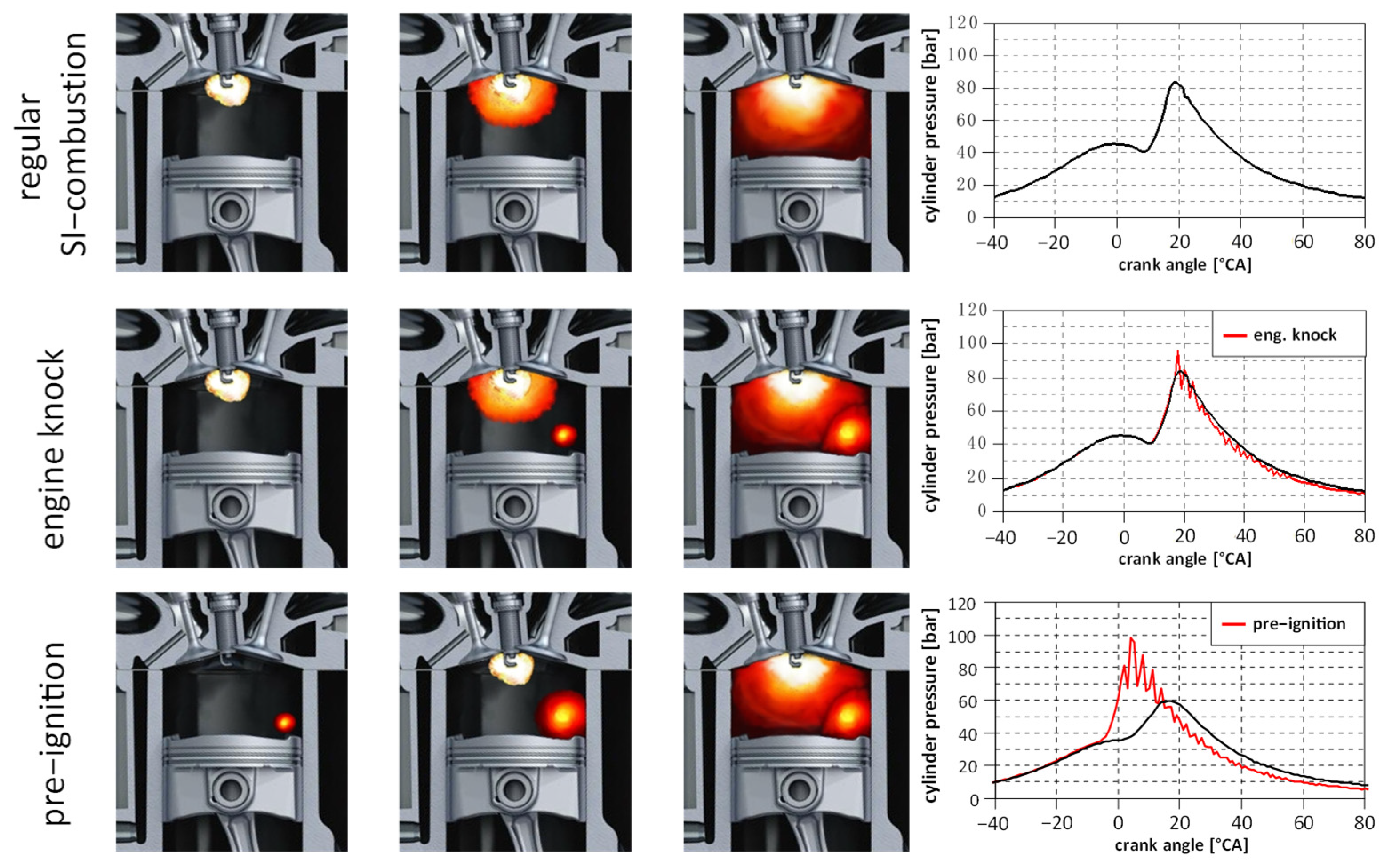

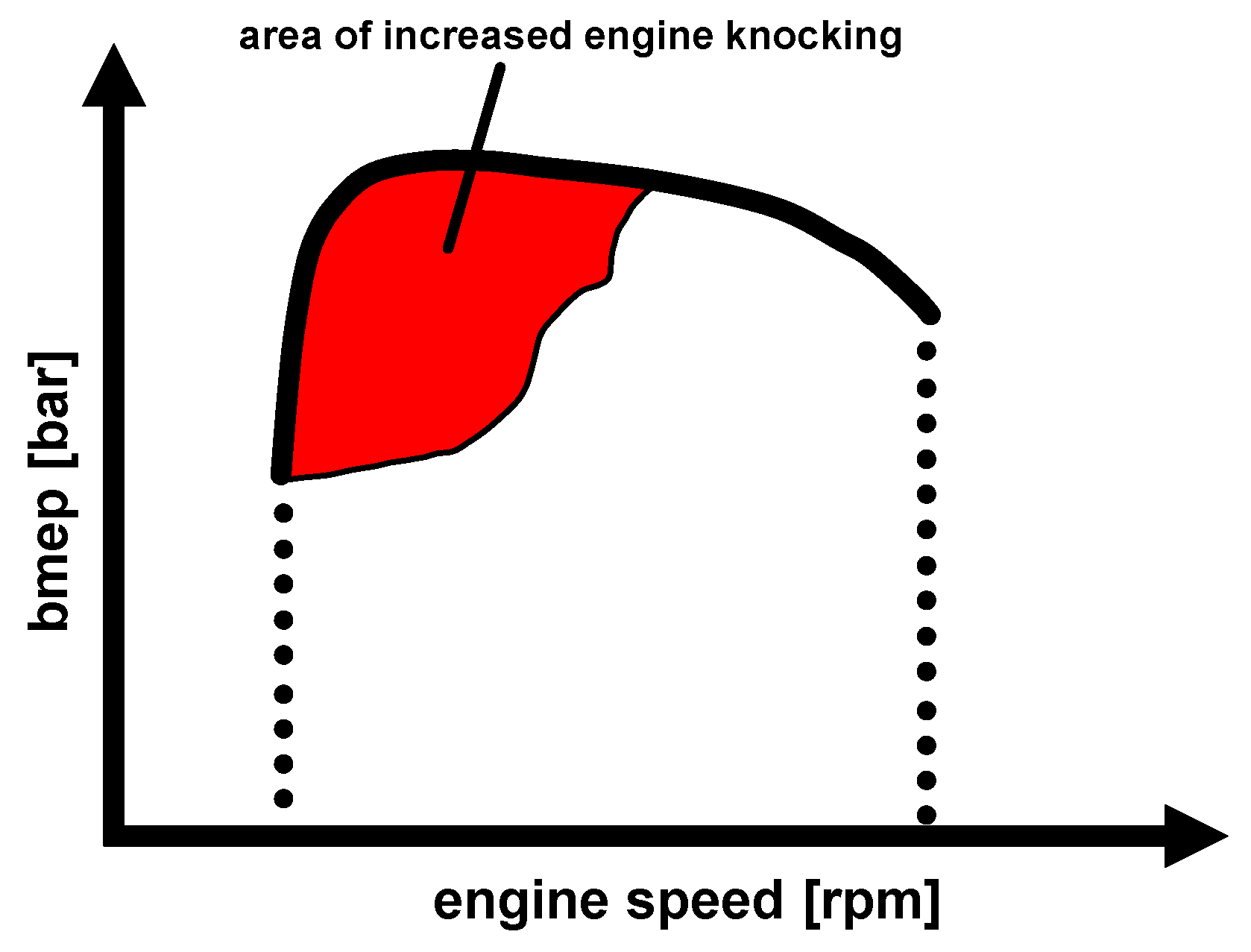

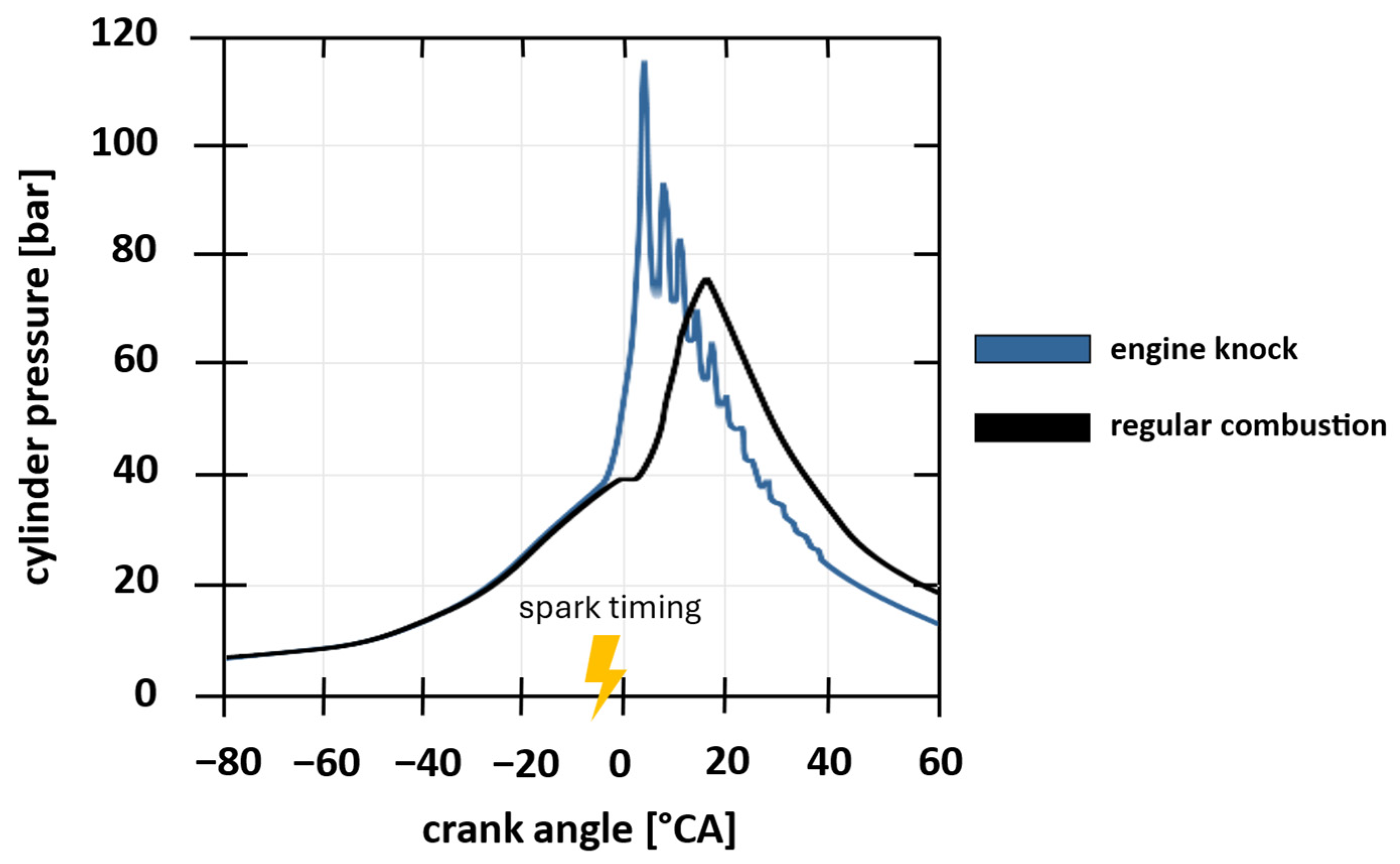

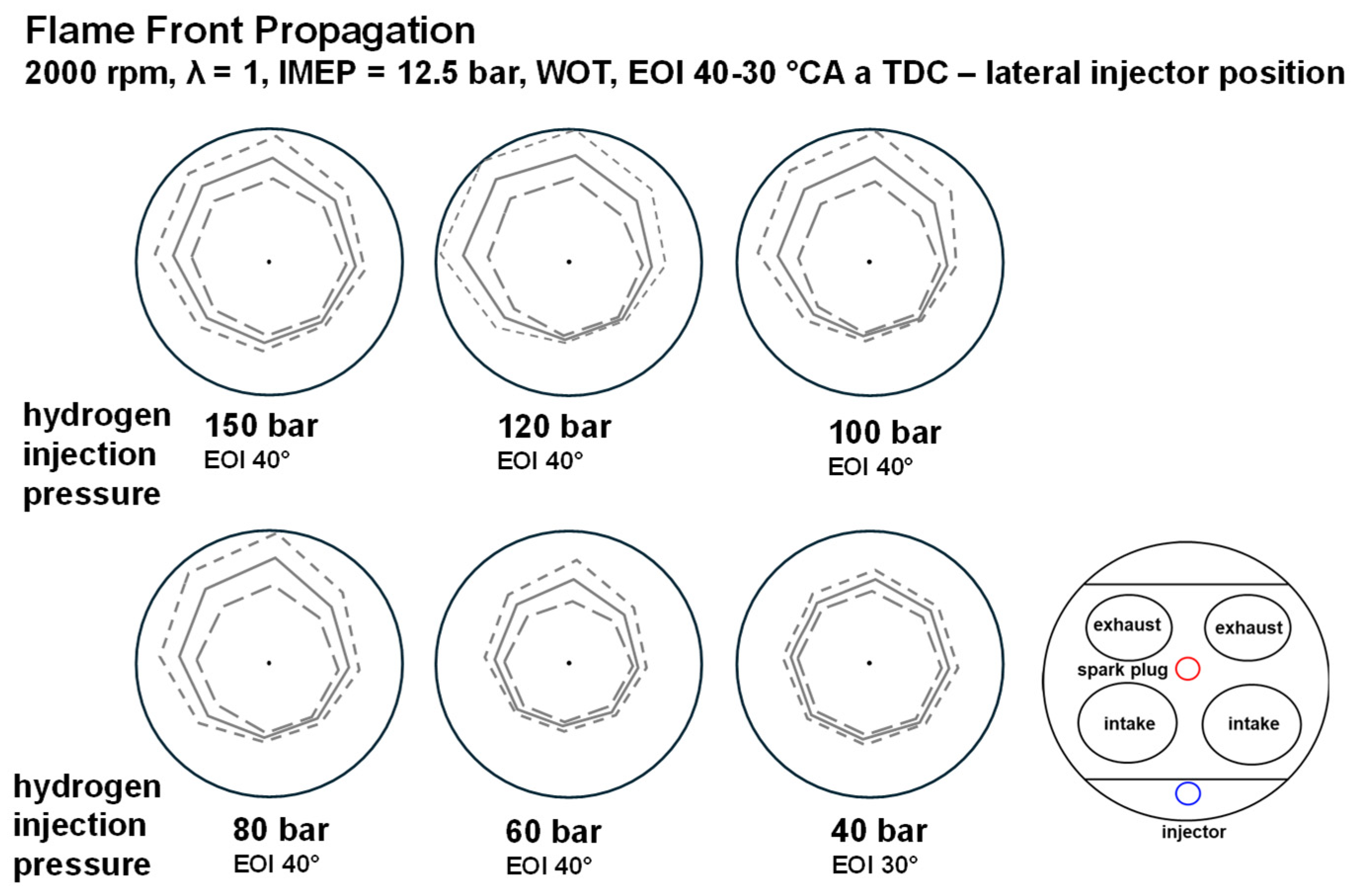

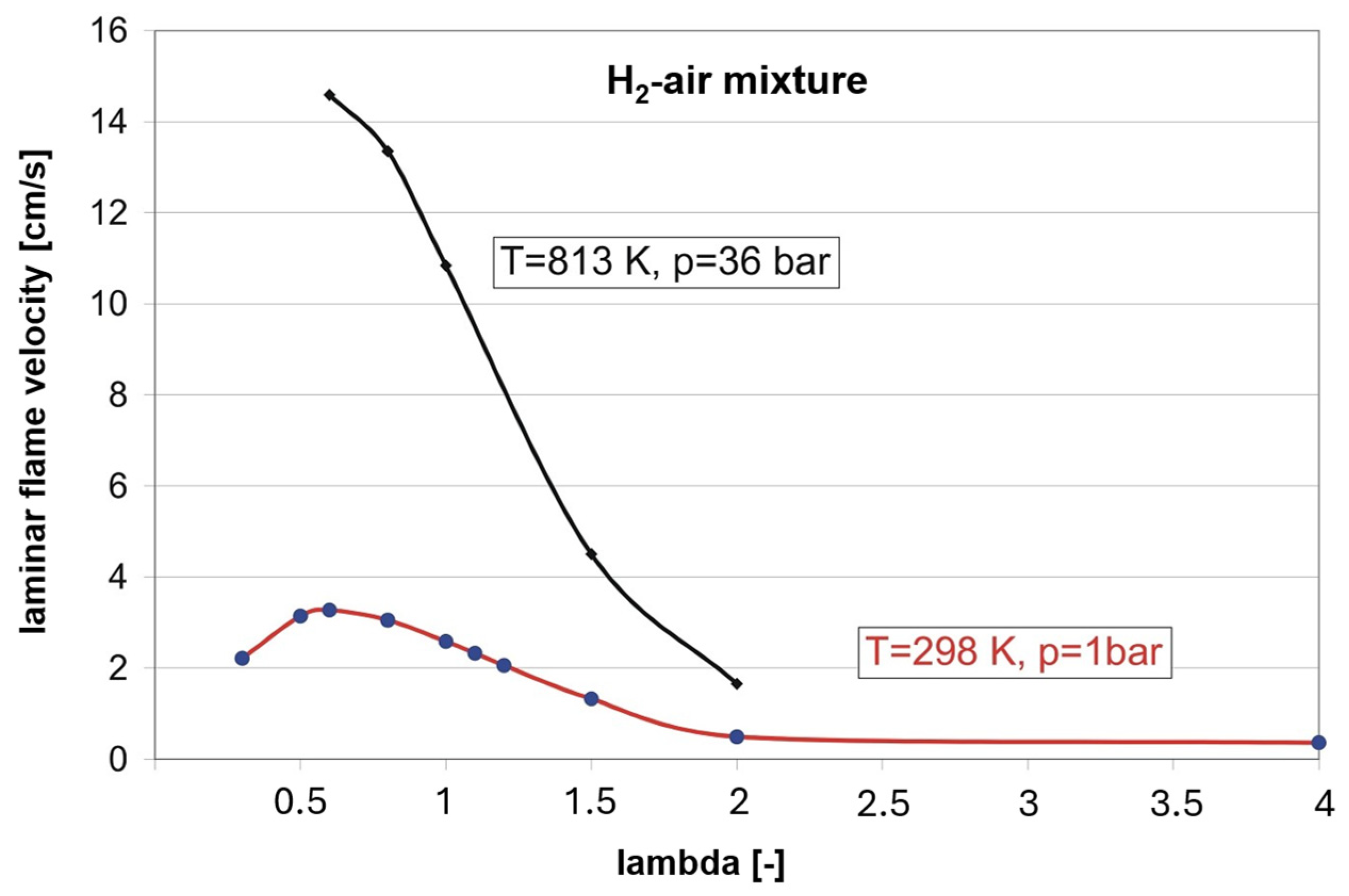

1.1. Engine Knock

- : Flame velocity;

- L: Radius of the combustion chamber.

- : Flame duration, which refers to the time required for the flame front to propagate from the ignition source (spark plug) to the outer boundary of the combustion chamber.

- : Duration of apparent ignition lag, which refers to the time required for the air-fuel mixture to undergo the self-ignition process.

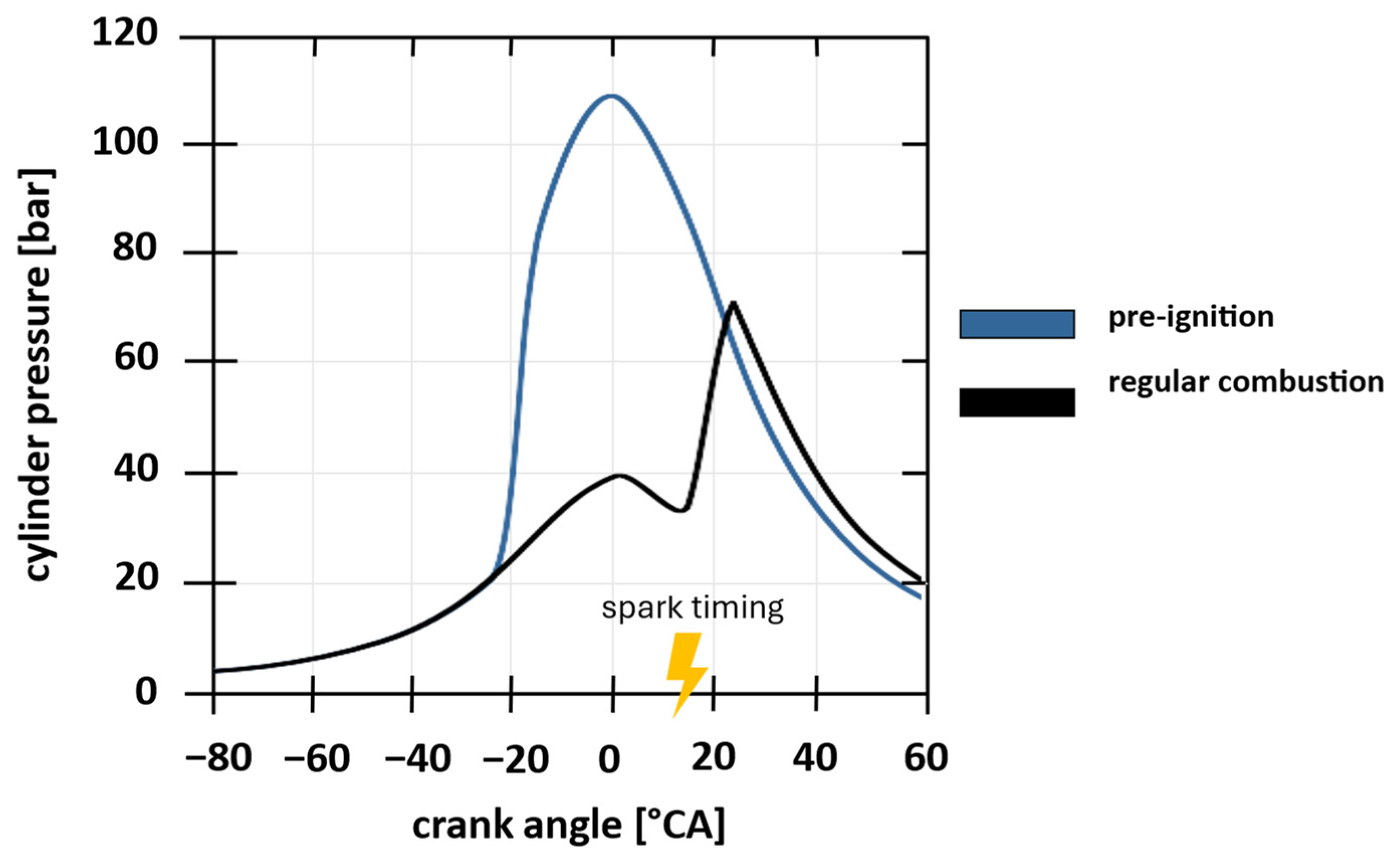

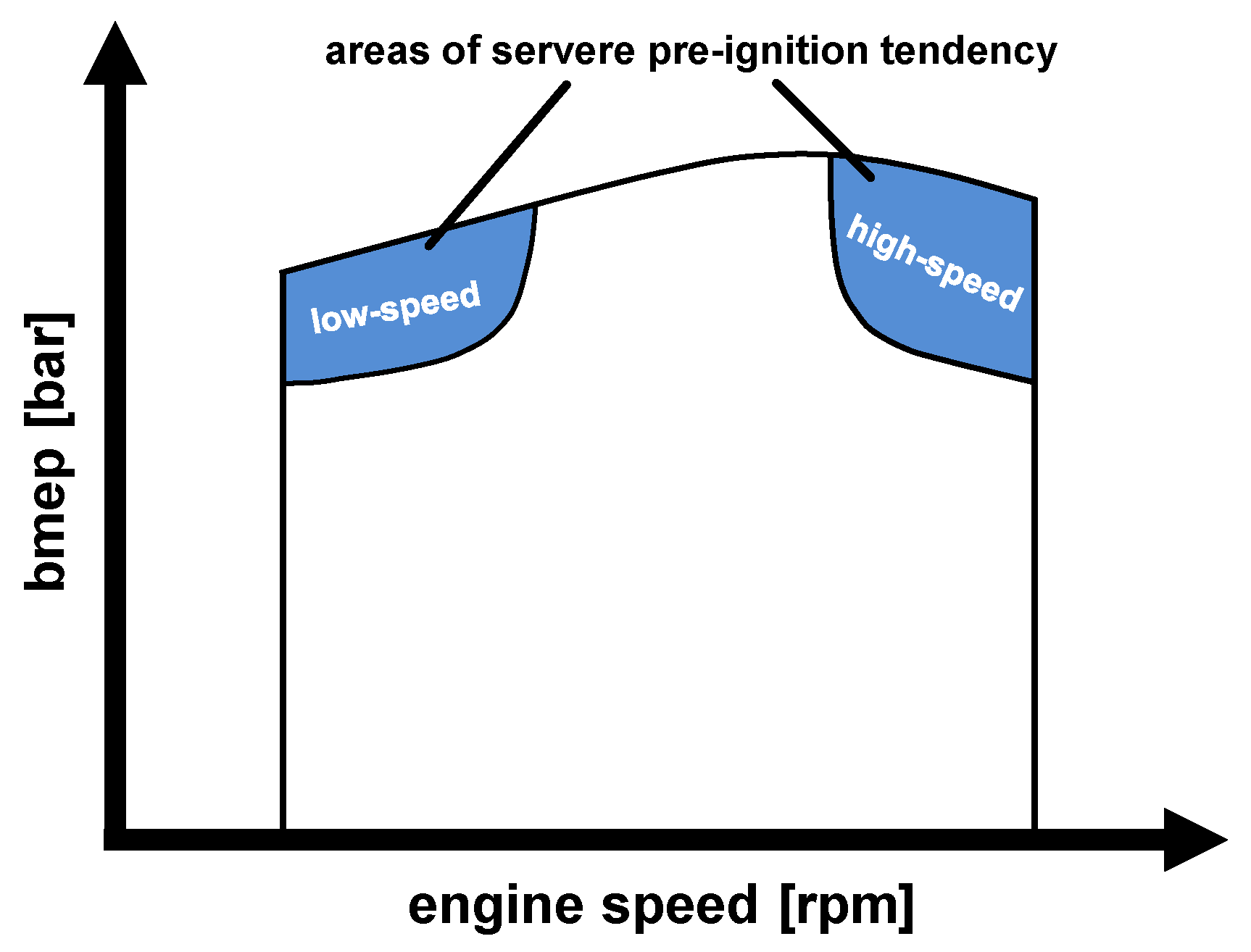

1.2. Auto-Ignition—Pre-Ignition

- Combustion may initiate prematurely during the compression phase, well before top dead center (BTDC). Early ignition may originate from locally overheated surfaces such as exhaust valves, spark plugs, or quench edges within the cylinder head. In addition, it can be triggered by particles, including oil droplets or oil evaporated from the cylinder walls and combustion chamber deposits, as well as within pockets of hot residual gases. The result is a rapid pressure rise, typically without the superimposed pressure oscillations that are characteristic of knocking combustion (see Figure 4).

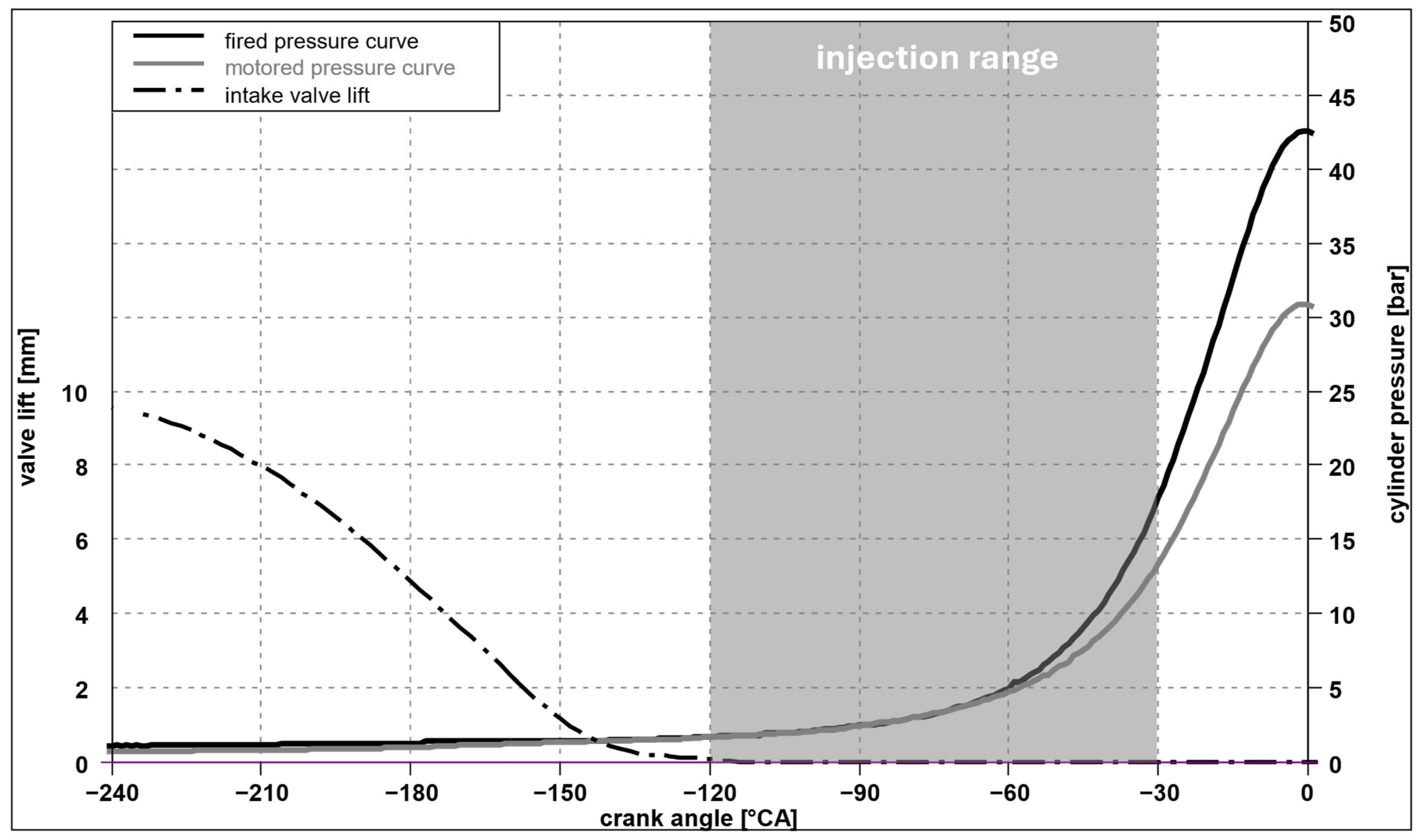

- Backfire represents an extreme form of pre-ignition, where combustion is initiated during the charge cycle. However, this phenomenon is effectively prevented with the injection strategy employed in the hydrogen direct-injection (DI) engine, as hydrogen injection does not commence until after the intake valve closed.

1.3. Knocking Auto-Ignition

2. Experimental Setup

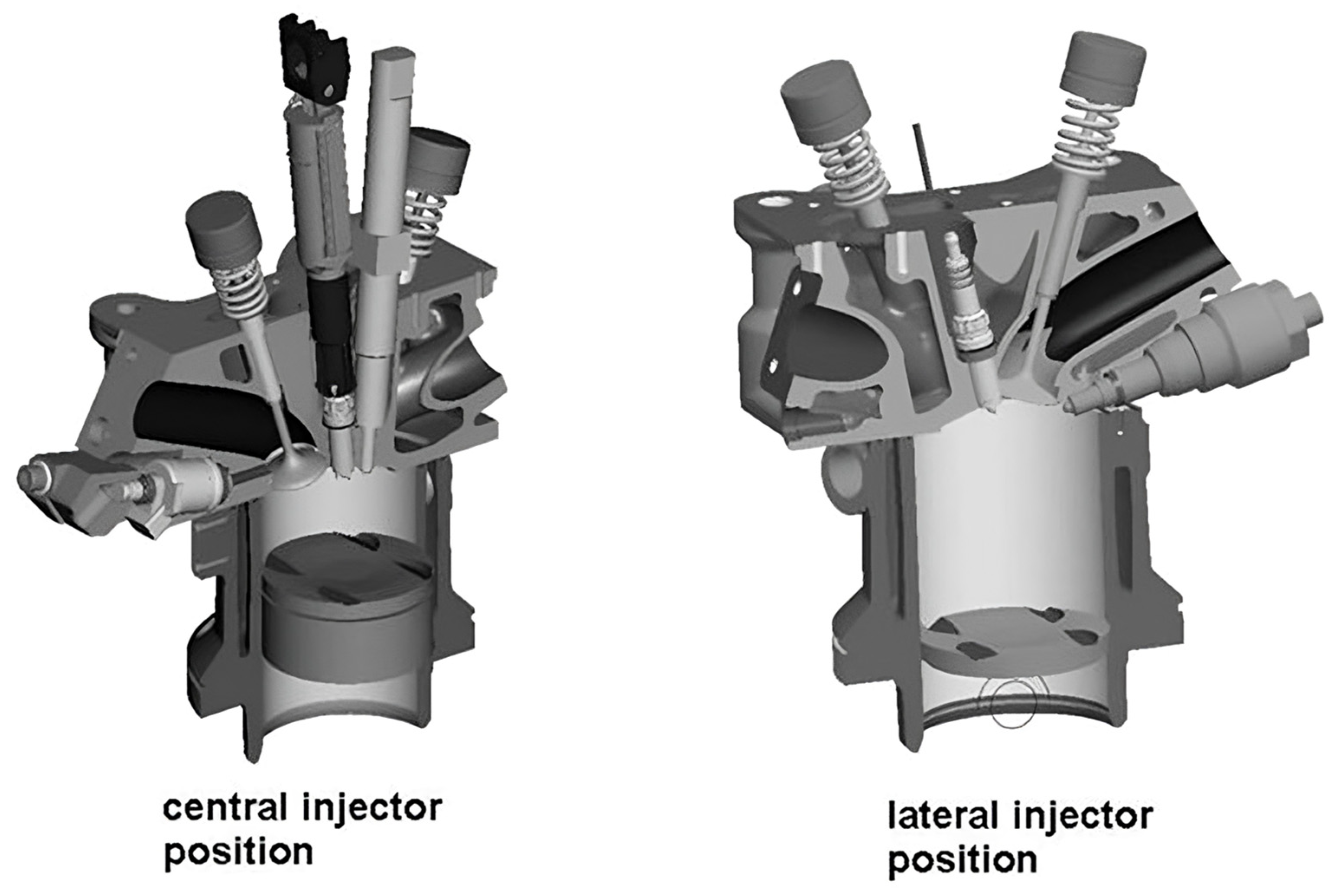

2.1. Hardware Selection for Measurements

- In variant 1 (central arrangement), the injection nozzle is positioned centrally between the valves.

- In variant 2 (lateral arrangement), the injector is located below the intake ducts, which slightly restricts the design freedom in the geometry of the ducts.

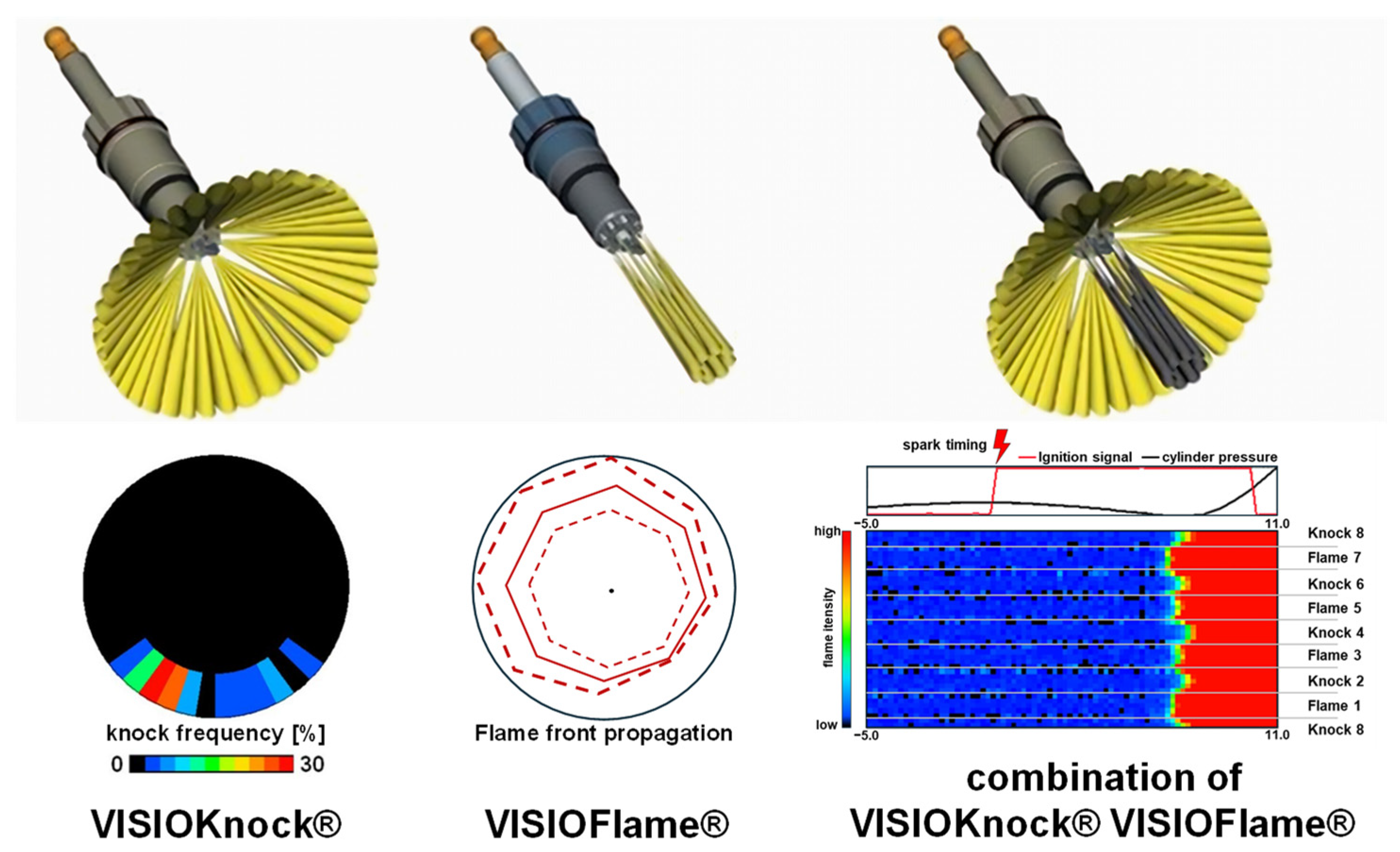

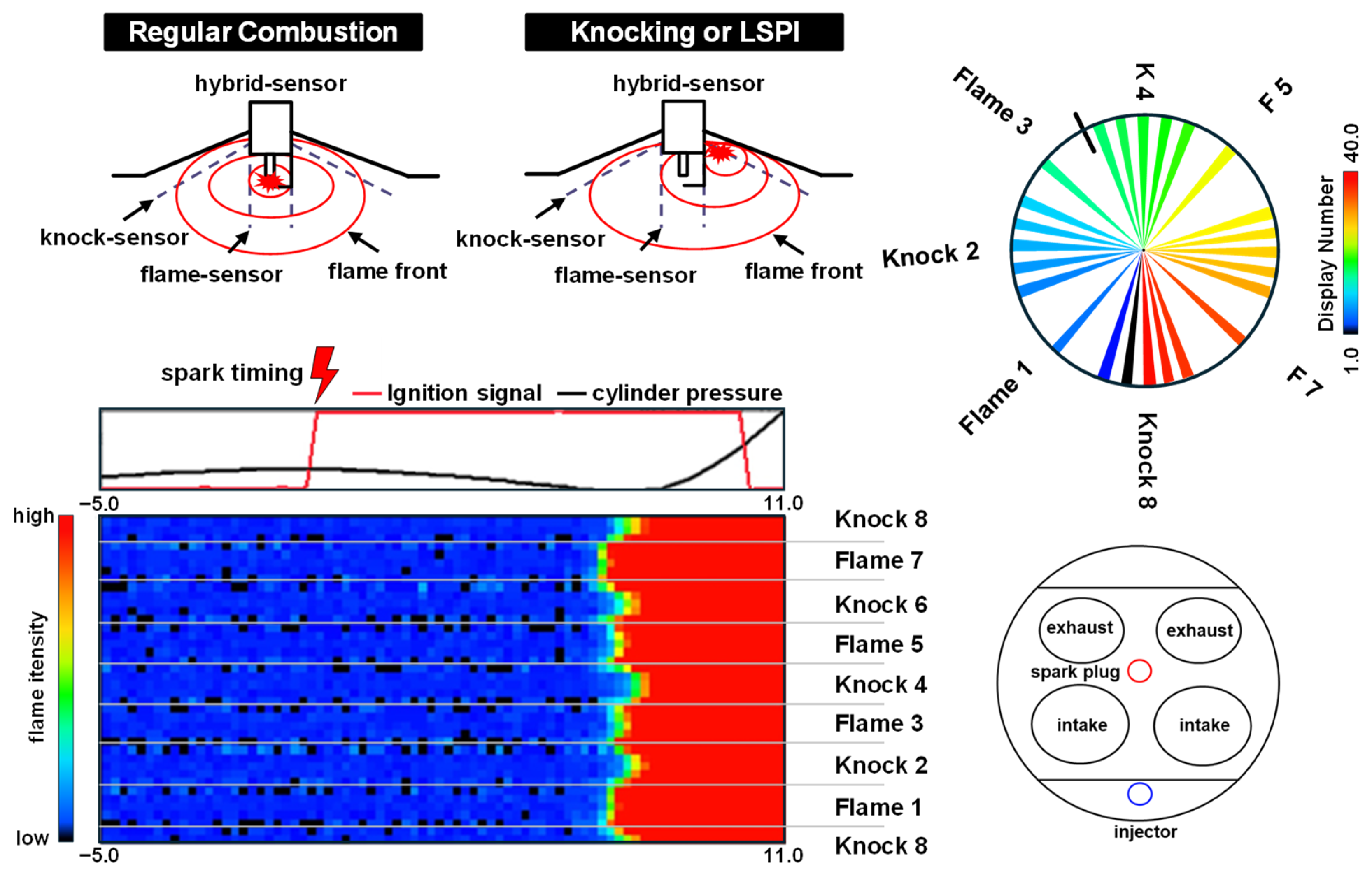

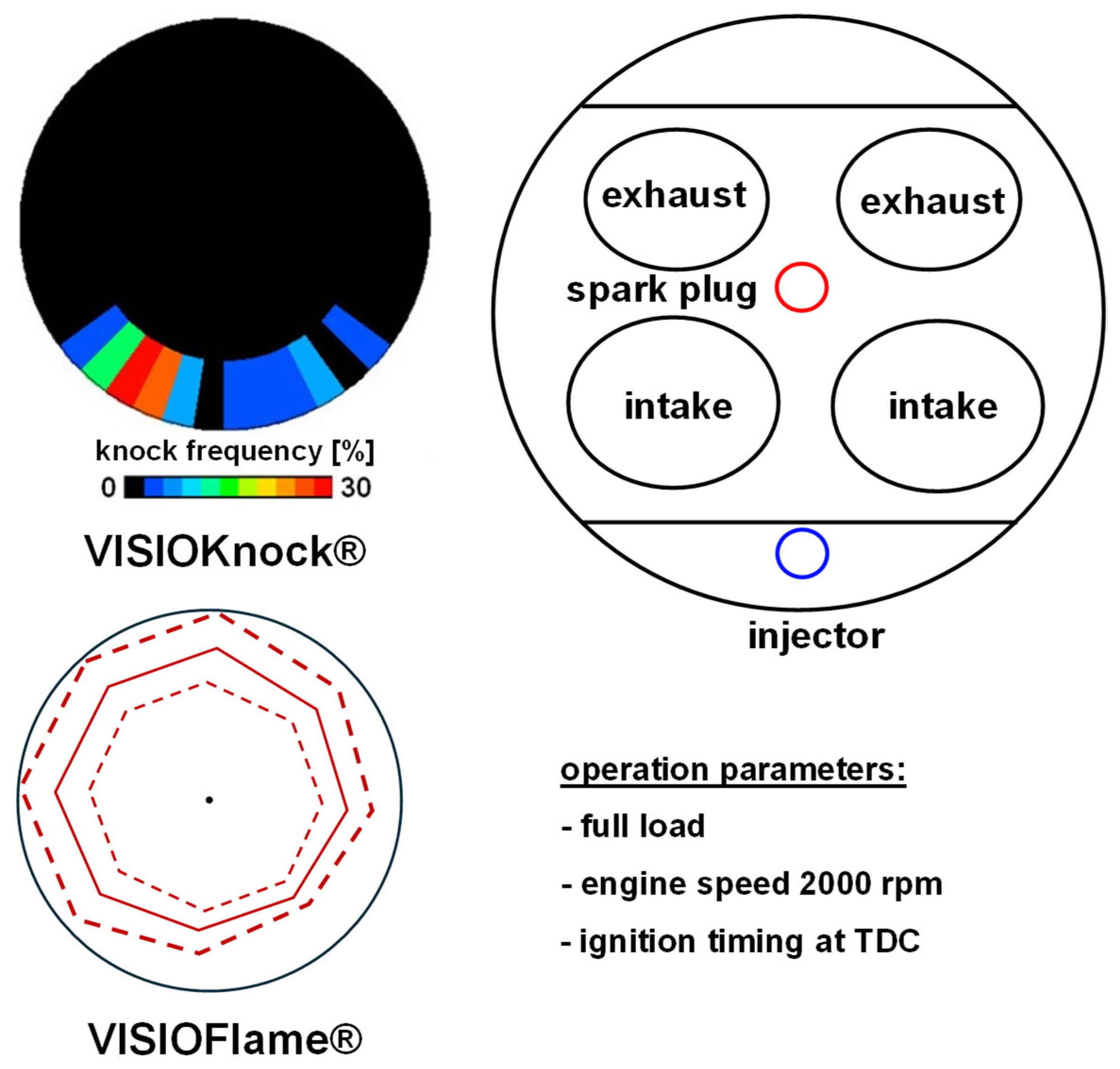

- The VISIOFlame® spark plug sensor utilizes a spark plug with downward-facing fiber optic sensors oriented toward the piston crown (see Figure 8). This configuration enables the determination of flame kernel development and combustion speed under real engine conditions.

- The VISIOKnock® spark plug sensor is equipped with conically arranged sensors directed outward. This setup allows for the detection and spatial localization of knock events and other combustion anomalies.

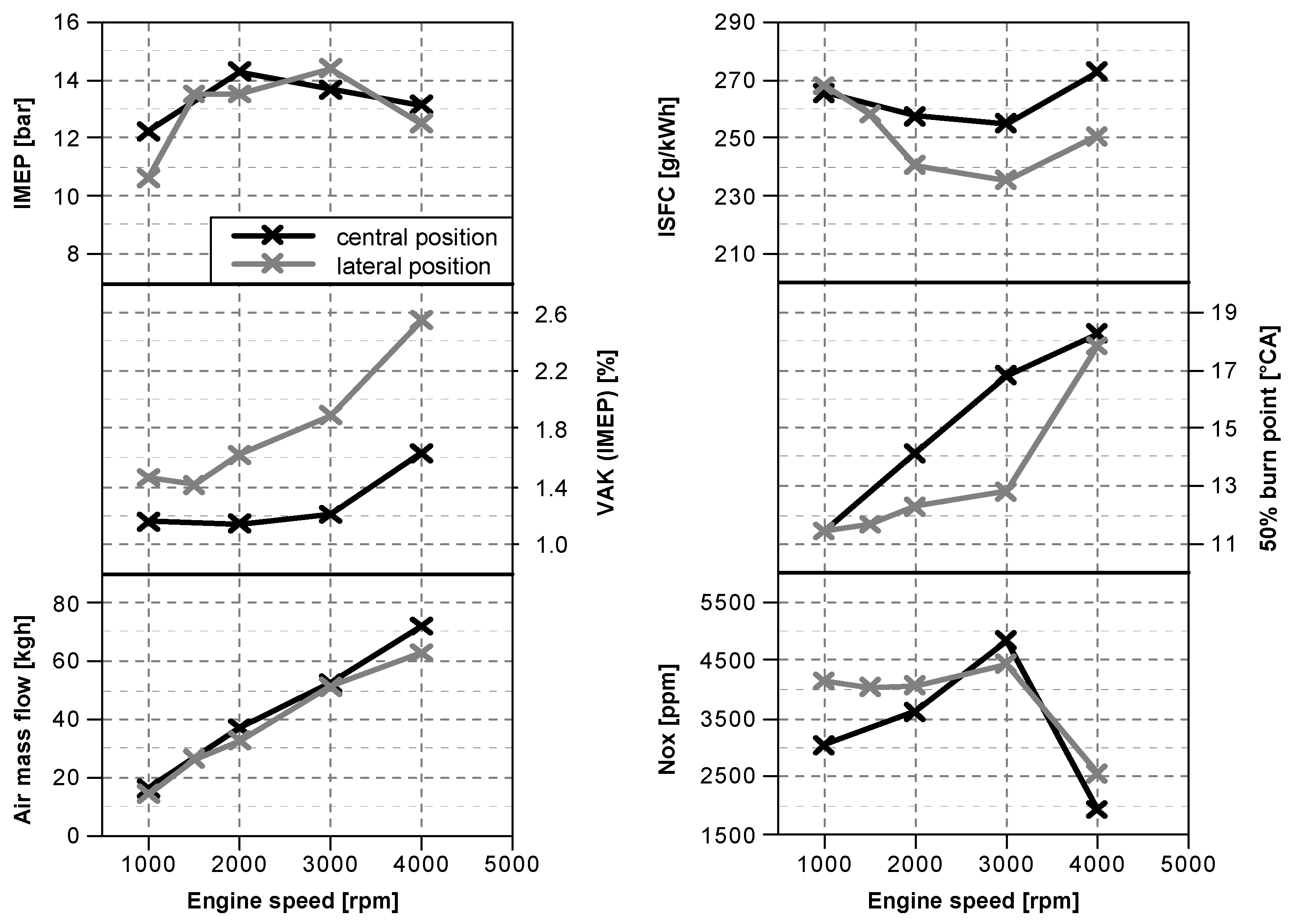

2.2. Preselection Injector Position

3. Analysis of Knock and Auto-Ignition Behavior

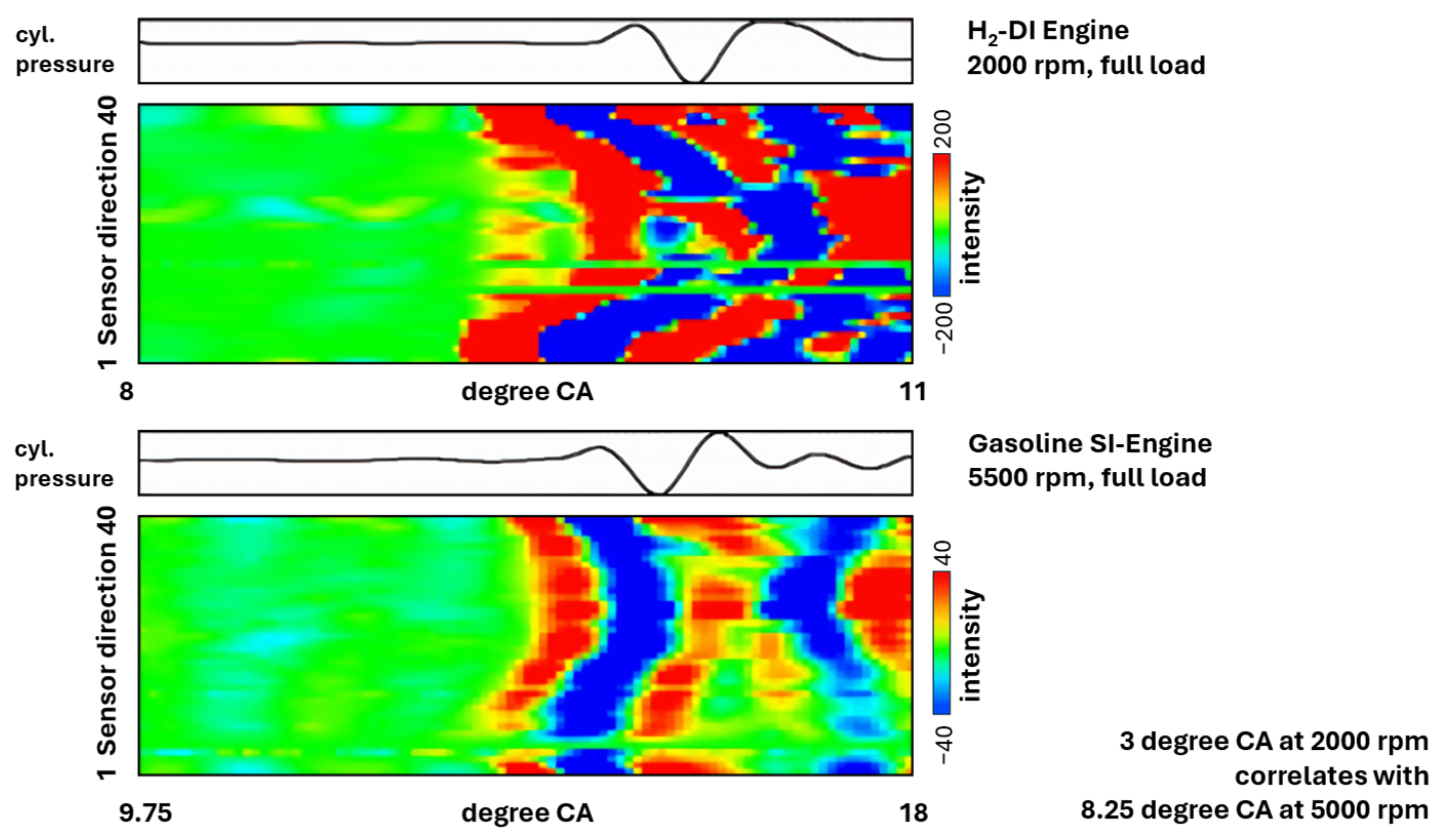

3.1. Methodology

- Residual gas content, influenced by variable valve timing;

- End of injection (EOI);

- Spark timing (ignition timing).

3.2. Knock Location Determination

3.3. Influence of Combustion Center Location on Knock and Efficiency

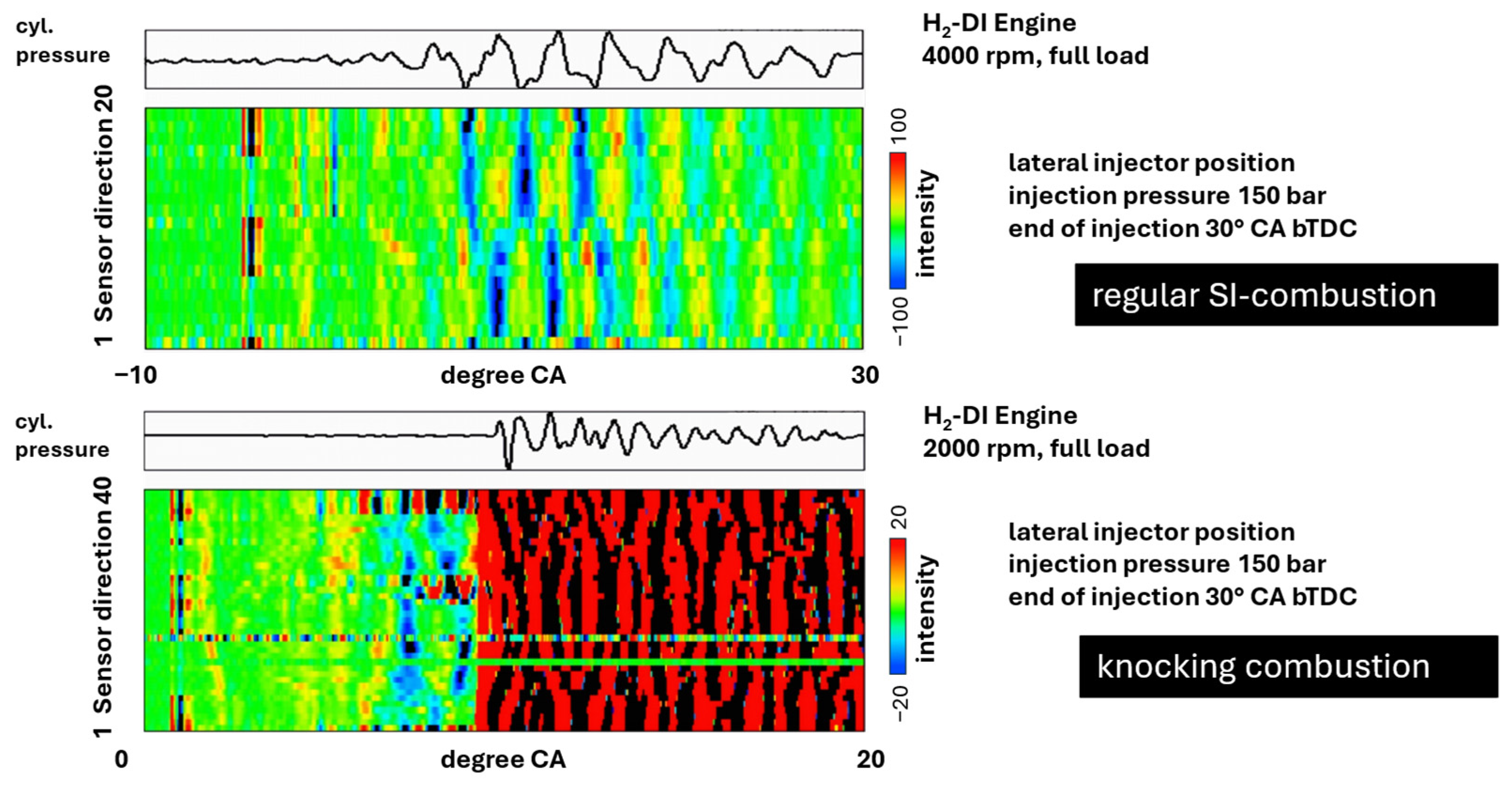

3.4. Analysis of Knock Event Origin

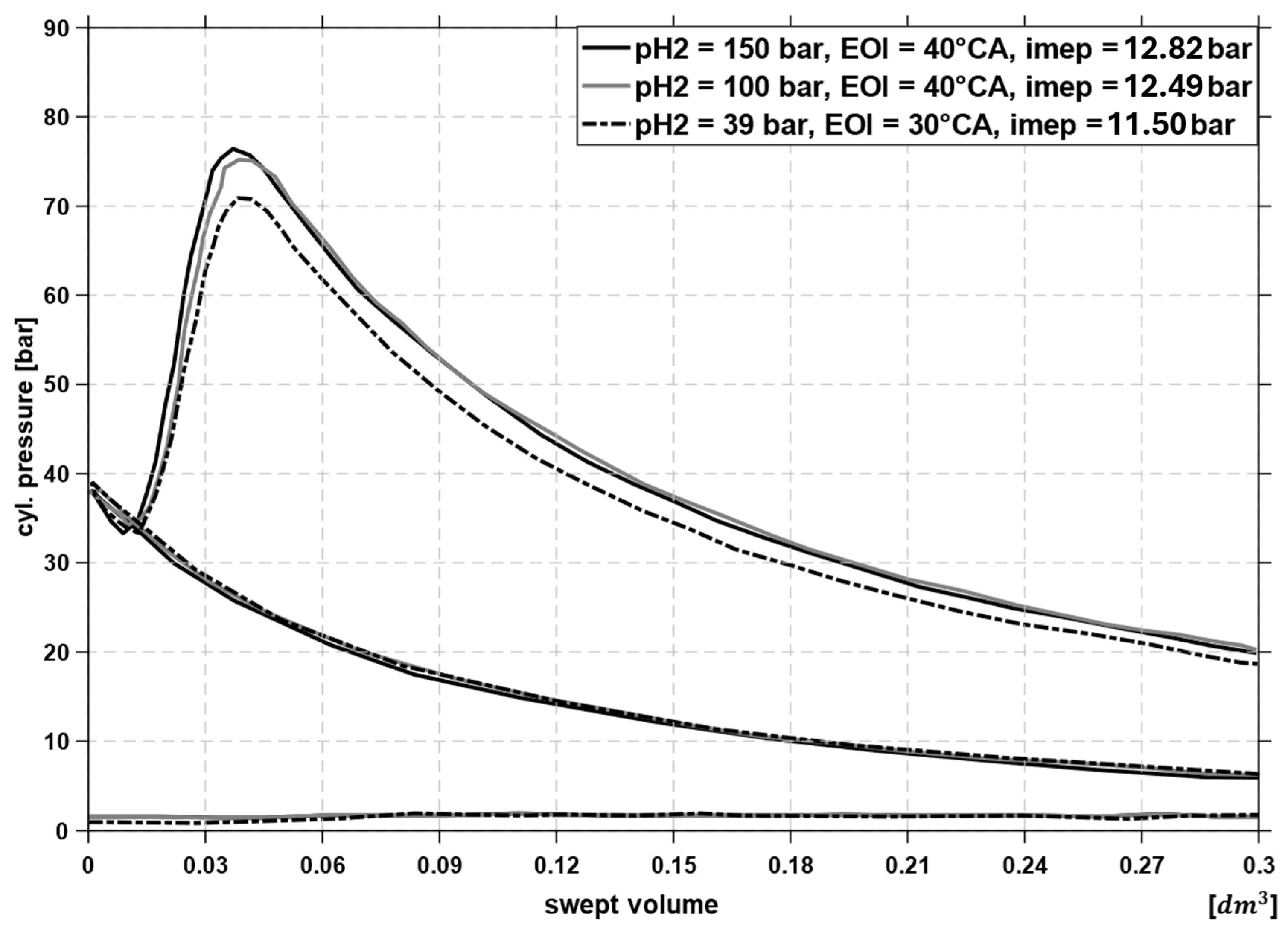

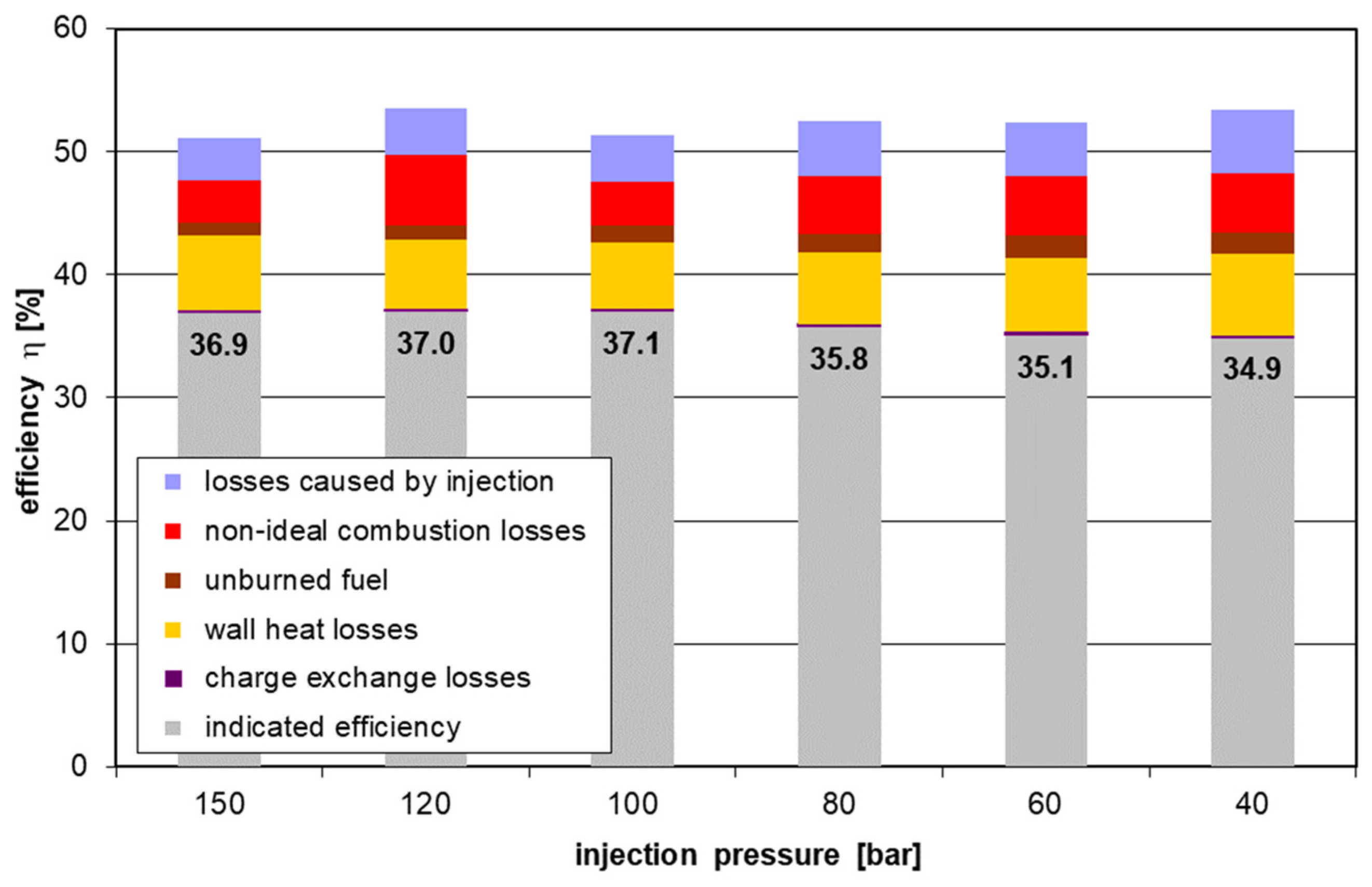

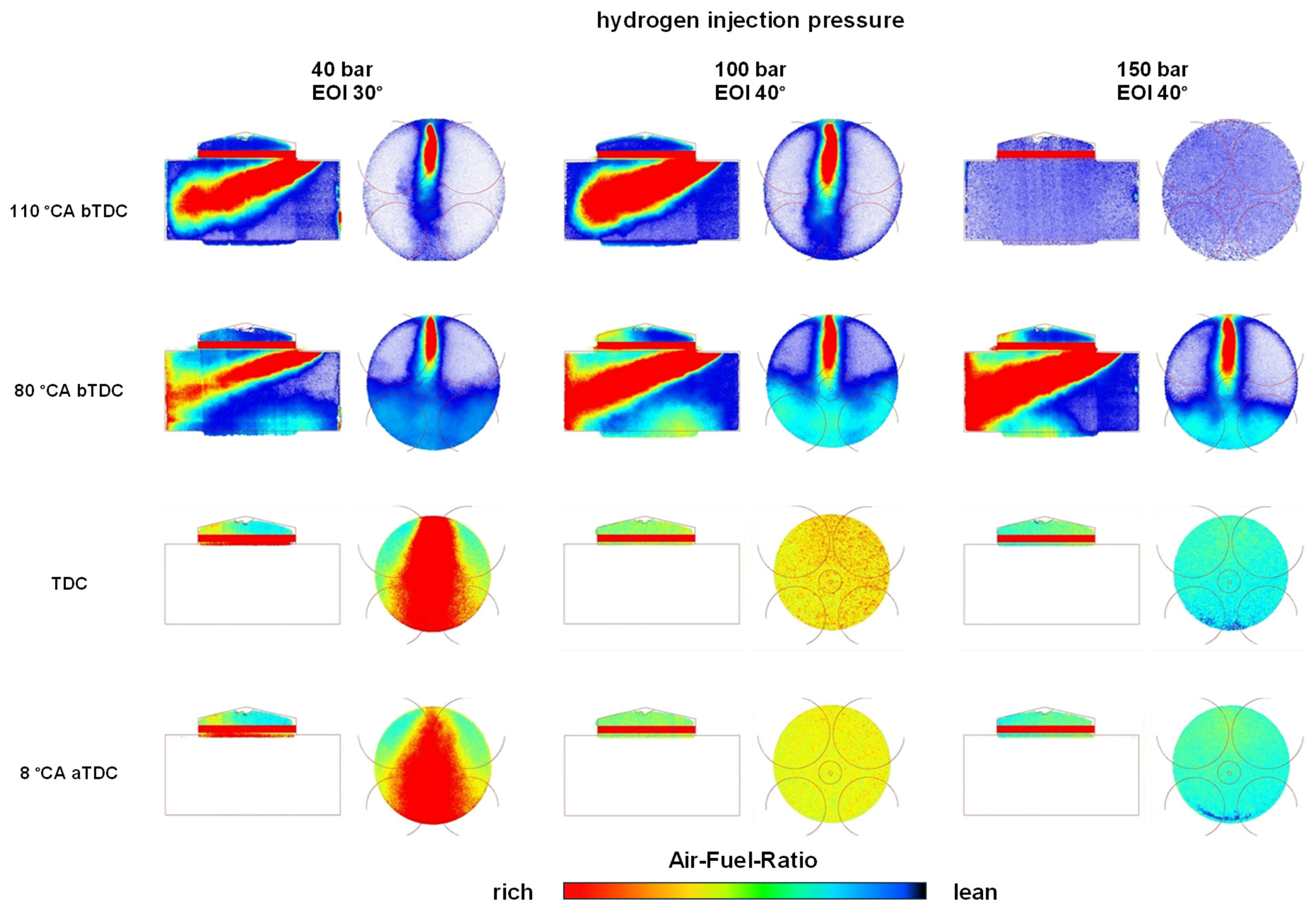

3.5. Influence of Injection Pressure on Combustion Stability and Efficiency

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATDC | After top dead center |

| bi | Indicated specific consumption |

| BTDC | Before top dead center |

| CA | Crank angle |

| CA50 | Center of combustion, 50% mass fraction burned |

| d | Bore |

| DI | Direct Injection (internal mixture formation) |

| EOI | End of Injection |

| IVC | Intake valve closure point |

| H2 | Hydrogen |

| n | Engine speed |

| NOx | Nitrogen Oxides |

| PFI | Port Fuel Injection (external mixture formation) |

| pH2 | Hydrogen pressure |

| pmi | Mean indicated pressure |

| s | Stroke |

| SOI | Start of Injection |

| TDC | Top dead center |

| ti | Duration of injection |

| VAK | Variation coefficient |

| VANOS | Variable camshaft valve timing |

| VH | Displacement |

| Y | Standard deviation, density distribution in combustion chamber |

| WOT | Wide open Throttle |

| Φ | Equivalence ratio, equals 1/λ) |

| ε | Compression ratio |

| ηi | Indicated efficiency |

| λ | Air/fuel ratio (equals 1/Φ) |

References

- Thomas Koch, D.; Sousa, A.; Bertram, D. H2-Engine Operation with EGR Achieving High Power and High Efficiency Emission-Free Combustion. In SAE Technical Paper Series, Proceedings of the 2019 JSAE/SAE Powertrains, Fuels and Lubricants, Kyoto, Japan, 26–29 August 2019; Thomas Koch, D., Sousa, A., Bertram, D., Eds.; SAE International400 Commonwealth Drive: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, T. Performance of NOx Absorption 3-Way Catalysis Applied to a Hydrogen Fueled Engine. In Proceedings of the 15th Word Hydrogen Energy Conference (2004), Yokohama, Japan, 27 June–2 July 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rottengruber, H.; Berckmueller, M.; Elsaesser, G.; Brehm, N.; Schwarz, C. A high-efficient combustion concept for direct injection hydrogen internal combustion engines. In Proceedings of the 15th World Hydrogen Energy Conference, Yokohama, Japan, 27 June–2 July 2004; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Berckmüller, M.; Rottengruber, H.; Eder, A.; Brehm, N.; Elsässer, G.; Müller-Alander, G.; Schwarz, C. Potentials of a Charged SI-Hydrogen Engine. In SAE Technical Paper Series, Proceedings of the SAE Powertrain & Fluid Systems Conference & Exhibition, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 27–30 October 2003; SAE International400 Commonwealth Drive: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, H.; Jones, P.; Bajwa, A.; Parsons, D.; Akehurst, S.; Davy, M.H.; Leach, F.C.; Esposito, S. Design trends and challenges in hydrogen direct injection (H2DI) internal combustion engines—A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 86, 1179–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klell, M.; Eichlseder, H.; Trattner, A. Wasserstoff in der Fahrzeugtechnik; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3-658-20446-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rottengruber, H.; Berckmüller, M.; Elsässer, G.; Brehm, N.; Schwarz, C. Direct-Injection Hydrogen SI-Engine—Operation Strategy and Power Density Potentials. In SAE Technical Paper Series, Proceedings of the 2004 Powertrain & Fluid Systems Conference & Exhibition, Tampa, FL, USA, 25–28 October 2004; SAE International400 Commonwealth Drive: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rottengruber, H.; Wintergoller, D. Wasserstoff als Kraftstoff. Gießtechnik im Motorenbau 2021; VDI Verlag: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2021; pp. 35–50. ISBN 9783181023860. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, P.A.; Dingli, R.J.; Abbasi Atibeh, P.; Watson, H.C.; Brear, M.J.; Voice, G. Performance of a Port Fuel Injected, Spark Ignition Engine Optimised for Hydrogen Fuel. In SAE 2012 World Congress & Exhibition; SAE International: Warrendale PA, USA, 2012; ISBN 2688-3627. [Google Scholar]

- Yip, H.L.; Srna, A.; Yuen, A.C.Y.; Kook, S.; Taylor, R.A.; Yeoh, G.H.; Medwell, P.R.; Chan, Q.N. A Review of Hydrogen Direct Injection for Internal Combustion Engines: Towards Carbon-Free Combustion. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woschni, G. Verbrennungsmotoren. Vorlesungsskript; Technische Universität München: München, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- van Basshuysen, R. (Ed.) Handbuch Verbrennungsmotor: Grundlagen, Komponenten, Systeme, Perspektiven; 3., vollst. überarb. und erw. Aufl.; Vieweg: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2005; ISBN 3528239336. [Google Scholar]

- Rottengruber, H.; Todsen, E.C. (Eds.) Knocking in Gasoline Engines: Potentials and Limits of Downsizing. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference, Berlin, Germany, 25–28 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Diéguez, P.M.; Urroz, J.C.; Sáinz, D.; Machin, J.; Arana, M.; Gandía, L.M. Characterization of combustion anomalies in a hydrogen-fueled 1.4 L commercial spark-ignition engine by means of in-cylinder pressure, block-engine vibration, and acoustic measurements. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 172, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pla, B.; Bares, P.; Jimenez, I.; Guardiola, C. Increasing knock detection sensitivity by combining knock sensor signal with a control oriented combustion model. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 168, 108665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichlseder, H.; Pischinger, R.; Wallner, T.; Wimmer, A.; Pirker, G.; Ringler, J. (Eds.) Thermodynamic Analysis of Spark-Ignition Engine Combustion Processes and Fuels and Their Potential; Symposium on Development Trends in Spark-Ignition Engines: Esslingen, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Maio, G.; Boberic, A.; Giarracca, L.; Aubagnac-Karkar, D.; Colin, O.; Duffour, F.; Deppenkemper, K.; Virnich, L.; Pischinger, S. Experimental and numerical investigation of a direct injection spark ignition hydrogen engine for heavy-duty applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 29069–29084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winklhofer, E.; Beidl, C.; Philipp, H.; Piock, W. Optical combustion diagnostics with easy to use sensor systems. MTZ Mot. Z. 2001, 62, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabireau, F.; Cuenot, B.; Vermorel, O.; Poinsot, T. Interaction of flames of H2 + O2 with inert walls. Combust. Flame 2003, 135, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargende, M. Schwerpunkt-Kriterium und automatische Klingelerkennung. MTZ Mot. Z. 1995, 56, 623. [Google Scholar]

- Balmelli, M.; Merotto, L.; Wright, Y.; Bleiner, D.; Biela, J.; Soltic, P. Optical and thermodynamic investigation of jet-guided spark ignited hydrogen combustion. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 78, 1316–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhelst, S.; Wallner, T. Hydrogen-fueled internal combustion engines. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2009, 35, 490–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepatz, K.; Rottengruber, H.; Zeilinga, S.; Koch, D.; Prümm, W. Loss Analysis of a Direct-Injection Hydrogen Combustion Engine. In SAE Technical Paper Series, Proceedings of the International Powertrains, Fuels & Lubricants Meeting, Heidelberg, Germany, 17–19 September 2018; SAE International400 Commonwealth Drive: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blotevogel, T.; Goldlücke, J.; Egermann, J.; Leipertz, A.; Hartmann, M.; Rottengruber, H. Untersuchung der Gemischbildung von Gasmotoren mit Hilfe laseroptischer Messverfahren. In Der Arbeitsprozess des Verbrennungsmotors (10. Tagung); Verlag der Technischen Universität Graz: Graz, Austria, 2005; pp. 139–166. [Google Scholar]

- Drell, I.; Belles, F. Survey of Hydrogen Combustion Properties. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/19930091021 (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- ANSYS Inc. ANSYS CHEMKIN Theory Manual 17.0: (15151); ANSYS Inc.: San Diego, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, U.; Warnatz, J. Ignition processes in hydrogen–oxygen mixtures. Combust. Flame 1988, 74, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Adjustment/Influence | Effect on Combustion/ Ignition | Impact on Knock Tendency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure at spark timing | Lower compression ratio (ε ↓) | p ↓ ignition delay ↑ | Knock tendency ↓ |

| Temperature at spark timing | Lower compression ratio (ε ↓) | T ↓ ignition delay ↑ | Knock tendency ↓ |

| Spark timing | Retarded ignition timing | T ↓ at spark timing | Knock tendency ↓ |

| Number of ignition sources | Increase number of ignition points | Faster flame propagation | Knock tendency ↓ |

| Combustion chamber shape | Shorter/less fissured chamber | More compact and faster combustion | Knock tendency ↓ |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Displacement | VH = 0.5 dm3 |

| Stroke | s = 90 mm |

| Bore | d = 84 mm |

| Compression ratio | ε = 12:1 |

| Piston shape | Flat, with a light lens-shaped bowl |

| Number of valves | 4 DOHC |

| Valve phasing | variable |

| Hydrogen injection pressure | 40–150 bar |

| engine speed range | n = 700 to 4000 rpm |

| mass balancing | partial mass balancing of the first order using counterweights |

| max. combustion chamber pressure | 120 bar |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rottengruber, H.S.; Wintergoller, D.; Ebert, M.; Dafis, A. Optical Analysis of a Hydrogen Direct-Injection-Spark-Ignition-Engine Using Lateral or Central Injection. Energies 2025, 18, 5972. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225972

Rottengruber HS, Wintergoller D, Ebert M, Dafis A. Optical Analysis of a Hydrogen Direct-Injection-Spark-Ignition-Engine Using Lateral or Central Injection. Energies. 2025; 18(22):5972. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225972

Chicago/Turabian StyleRottengruber, Hermann Sebastian, Dmitrij Wintergoller, Maikel Ebert, and Aristidis Dafis. 2025. "Optical Analysis of a Hydrogen Direct-Injection-Spark-Ignition-Engine Using Lateral or Central Injection" Energies 18, no. 22: 5972. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225972

APA StyleRottengruber, H. S., Wintergoller, D., Ebert, M., & Dafis, A. (2025). Optical Analysis of a Hydrogen Direct-Injection-Spark-Ignition-Engine Using Lateral or Central Injection. Energies, 18(22), 5972. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225972