Abstract

The escalating demand for efficient energy harvesting in CubeSat missions necessitates advanced maximum power point tracking (MPPT) techniques. This work presents a comprehensive time-domain analysis and simulation of three MPPT algorithms: perturb and observe (PO), particle swarm optimization (PSO), and a novel hybrid PO-PSO method, tailored explicitly for CubeSat photovoltaic (PV) solar modules. Utilizing MATLAB R2025a/Simulink, a detailed model of a PV module based on the Azur Space 3G30C datasheet and a DC-DC boost converter was developed. The conventional PO MPPT, while simple, demonstrated limitations in tracking the global maximum power point (GMPP) under rapidly changing temperature conditions and exhibited significant oscillations around the GMPP. The PSO algorithm, known for its global search capabilities, was investigated to mitigate these shortcomings. This research introduces a hybrid PO-PSO MPPT technique that synergistically combines the low computational complexity of PO with the robust global optimization of PSO. Time-domain simulation results demonstrate that the proposed hybrid PO-PSO MPPT significantly reduces oscillations around the GMPP, enhances tracking accuracy under varying temperature conditions, and stabilizes output parameters more effectively than standalone PO or PSO methods. These findings validate the hybrid approach as a superior and reliable solution for optimizing power generation in constrained CubeSat applications.

1. Introduction

Metaheuristic approaches have emerged as powerful tools for tackling complex optimization problems, offering robust solutions where traditional methods fall short. These algorithms, including particle swarm optimization (PSO), ant colony optimization ACO), and differential evolution (DE), have effectively controlled dynamically nonlinear systems. Recent advancements in the field of optimization focus on overcoming the inherent limitations of traditional metaheuristics, such as premature convergence and reliance on problem-specific knowledge. Innovations include the development of improved algorithms, such as the tunicate swarm algorithm (TSA) and the modified gray wolf optimizer (MGWO), which address issues like premature convergence and economic emission dispatch. Furthermore, a significant trend is the integration of metaheuristic algorithms with fuzzy logic and reinforcement learning, driving a shift toward “environment-aware autonomous evolution” paradigms in control systems. The emergence of hyper-heuristic algorithms (HHAs) represents a crucial step forward, implementing a meta-optimization layer that dynamically selects and evolves low-level operators, enhancing dynamic adaptability and reducing problem-specific dependencies. These ongoing developments underscore the expanding role of metaheuristics in achieving multi-objective collaborative optimization and accelerating convergence in various large-scale scenarios [1].

Partial shading stands out as a critical operational challenge, even for space missions, not only diminishing module efficiency but also posing a risk of hot spots that can result in substantial damage to solar cells/modules. To prevent partial shading caused by other objects in LEO, bypass diodes are used. Conventional MPPT techniques often suffer from slow convergence speeds and suboptimal tracking performance, particularly under dynamic variations in environmental conditions. Smart optimization algorithms (SOAs) using metaheuristic optimization algorithms can avoid such limitations inherent in conventional MPPT methods. The challenge of slow convergence of the SOA can be avoided using a novel strategy called swarm size reduction (SSR), usable with a particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm [2].

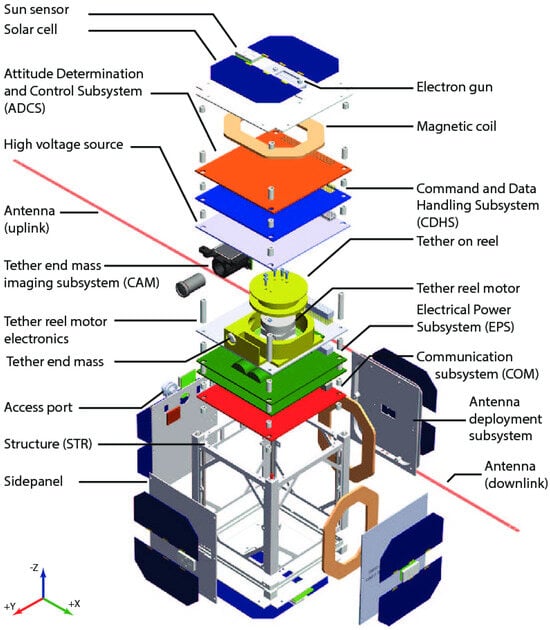

Cube satellites (CubeSats) have revolutionized access to space due to their standardized form factor, low development cost, and short design cycles [3]. A 1U CubeSat, the smallest unit, has a cubic volume of 10 cm3, weighs about 1.3 kg, and integrates all essential subsystems, namely, the electrical power system (EPS), the attitude determination and control system (ADCS), the onboard computer (OBC), telemetry, tracking and command (TT&C), and the payload, into this compact structure. Due to these constraints, the efficiency and resilience of the EPS become critical for the success and longevity of CubeSat missions. A crucial challenge in CubeSat design is ensuring robust power availability, which relies heavily on the efficiency of the electric power system (EPS).

The EPS, which comprises power sources (solar panels), power regulation and control (high-frequency switching converters), storage, and loads, must efficiently extract maximum power from its limited solar panel area throughout its orbit. A single low-Earth-polar-orbit cycle lasts approximately ninety minutes, during which the CubeSat experiences sun and eclipse periods. Power generation in CubeSats relies on solar photovoltaic (PV) modules mounted on their external panels. These modules must function effectively despite orbital variations, including eclipse periods and non-ideal orientation to the Sun. Therefore, implementing maximum power point tracking (MPPT) algorithms is indispensable to ensure that each PV module continuously operates at or near its maximum power point (MPP), particularly under dynamic irradiance and temperature, and even partial shading conditions encountered in a low Earth orbit (LEO) [4].

Two primary EPS architectures are commonly used in CubeSat systems: direct energy transfer (DET) and MPPT-based regulation. DET is less complex but inefficient under partial shading or in case of single-panel failures, as it typically relies on series-connected modules. In contrast, MPPT-based architectures employ individual boost converters per panel or module, each operating independently to extract the maximum available power [5]. The work presented in this article focuses on PV power generation, control, and regulation for CubeSat power systems, excluding the modeling of the battery charge regulator (BCR) and battery systems to limit the technical deliverables. In this study, a Simulink PV module was developed using an Azur Space 3G30C PV module datasheet, each delivering 2.5 V, 0.5 A, and 2.5 W under standard testing conditions (STC: 1367 W/m2; 28 °C), connected in parallel on the CubeSat body sides and regulated by individual MPPT-controlled DC-DC boost converters.

The amount of time needed for the MPPT technique to stabilize and reliably track the MPP is known as the stability time. Dual metaheuristic hybrid algorithms have high complexities. A single metaheuristic or a hybrid of a single metaheuristic and a direct search function has medium complexity. A single direct search has low complexity. Table 1 presents MPPT using different algorithms. The authors of [6] used a hybrid of slime mould optimization (SMO) and equilibrium optimizer (EO) algorithm for a solar photovoltaic system to achieve a stability time of 0.244 s under all tested conditions. A hybrid MPPT technique to maximize power harvesting from a PV system under partial and complex partial shading used a hybrid of dragonfly optimization and incremental conductance to achieve a stability time of 0.75 s under all tested conditions in [7]. A hybrid MPPT approach for solar PV systems using particle swarm optimization-trained machine learning and flying squirrel search optimization was used to achieve a stability time of 1.6 s under all tested conditions in [8]. To calculate the efficiency of an MPPT model in Simulink, the measured average power from the PV array is divided by the maximum power that the PV array can theoretically provide (under constant irradiance and varying temperature).

Table 1.

A comparison of the literature related to hybrid algorithms.

The PO-PSO hybrid model was tested under a fixed irradiation of 1367 W/m2 and randomly varying temperatures between −100 °C and +120 °C to simulate low-Earth-orbit space weather.

This study followed a structured modeling and simulation methodology using MATLAB/Simulink. First, a detailed mathematical model of the Azur Space 3G30C PV module was developed using a one-diode, two-resistor (1D/2R) equivalent circuit. Next, DC-DC boost converters were designed to elevate the PV output to a regulated bus voltage of 5 V, aligning with CubeSat subsystem requirements. The PO algorithm was implemented in Simulink using a duty-cycle perturbation scheme that adjusts based on the gradient of power change. The PSO MPPT algorithm was developed as a MATLAB function and integrated into the Simulink environment. Finally, the hybrid PO-PSO MPPT was developed by incorporating PSO-based corrections into the PO logic during specific perturbation intervals, effectively suppressing power ripples and improving response accuracy.

Systems simulations were conducted under constant temperature and dynamically varying space temperature conditions to analyze and compare the MPPT algorithm’s performance. Metrics such as MPP tracking accuracy/efficiency, complexity, stability time, and oscillatory behavior were used to evaluate each controller. These simulations validate that a hybrid PO-PSO MPPT controller offers a significantly improved power extraction strategy for CubeSat systems, particularly under environmental uncertainties and degraded conditions, such as single-panel failure or varying temperatures. The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the detailed modeling and implementation for the 3G30C PV module, boost converters, and each MPPT technique. Section 3 presents the simulation results and performance analysis across various environmental scenarios. Section 4 discusses the observed advantages and limitations of each method, as well as the comparison of all the developed MPPT controllers, with results benchmarked against the existing literature. Section 5 concludes with key findings and identifies future research opportunities for embedded implementation and real-time validation.

Traditional MPPT methods, such as perturb and observe (PO), are favored in space systems for their low computational and hardware requirements, making them well-suited to OBCs with limited processing power. However, PO struggles with rapidly fluctuating environmental conditions, leading to suboptimal tracking and sustained oscillations around the global maximum power point (GMPP) [9]. These oscillations reduce the available energy for critical subsystems, compromising mission longevity. To address these limitations, this study explored time-domain simulation and control strategies using advanced AI-based MPPT methods. Specifically, the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm was evaluated for its global optimization capabilities and robustness in dynamic environments. Moreover, a novel hybrid PO-PSO MPPT algorithm is proposed, which integrates the true seeking ability, fast convergence, and faster settling time of PO with the global optimization capabilities and robustness in dynamic environments of PSO to achieve faster settling times, reduced output oscillations, and improved tracking under fast-varying temperature. The technical components of this work, which were implemented in MATLAB/Simulink, were as follows:

- PV module: The Azur space 3G30C PV module was modeled, which produced 2.2 V, 0.47 A, and 1 W at MPP under standard test conditions (1367 W/m2 and 28 °C).

- Boost converter: A boost converter was designed, modeled, and simulated to control and regulate input and output power. A key design feature was that each PV module on a panel side has its boost converter and MPPT controller, which is beneficial for single-module failures or partial shading conditions.

- MPPT algorithms: The PO, PSO, and novel hybrid PO-PSO MPPT functions were implemented to control the duty cycle of the boost converter’s PWM signal. The hybrid model was developed to improve PO and PSO output power yields when implemented independently, especially under varying space weather conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

This section will start with modeling the Azur space 3G30C PV module (Heilbronn, Germany) in the MATLAB/Simulink platform. Then, it proceeds with the modeling of the boost converter in Simulink. Next, the modeling and writing of the PO, PSO, and PO-PSO MPPT MATLAB functions will be demonstrated.

2.1. Azur Space 3G30C PV Module Modeling

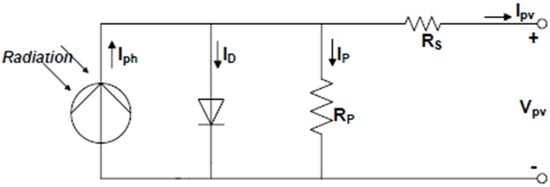

This section details the mathematical modeling and Simulink implementation of the Azur Space 3G30C photovoltaic (PV) module, which serves as the core power source for the CubeSat’s electrical power system (EPS). The model employs a single-diode/two-resistor (1D/2R) equivalent circuit, depicted in Figure 1, a widely accepted approach for accurately representing the electrical characteristics of a PV solar cell.

Figure 1.

PV solar cell model of 1D/2R equivalent circuit (adapted from [10]).

2.1.1. PV Module Mathematical Modeling

The electrical behavior of the PV solar module is fundamentally governed by five algebraic current equations, derived from first principles and depicted in the single-diode/two-resistor PV equivalent solar cell circuit (Figure 1) [10]. These equations are crucial for predicting the module’s performance under all conditions. The five key parameters that must be predetermined for this model are the photovoltaic current (Iph), diode reverse saturation current (Irs), diode ideality factor (n), series resistance (RS), and parallel resistance (RP). This study adopted the parameters established by [11]. These parameters were analytically fitted to the current–voltage (I-V) curves derived from the Azur Space 3G30C solar cell datasheet. This analytical fitting method utilizes characteristic points such as the short-circuit current (ISC), maximum power point (Vmpp and Impp), and open-circuit voltage (VOC) to accurately determine the five parameters, as opposed to numerical fitting, which requires many I-V curve points [11]. The values of these parameters under standard test conditions (STCs) are provided in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2.

Parameters of mathematical equations.

Table 3.

Electrical data of the Azur Space 3G30C module BOL.

The electrical data specific to the Azur Space 3G30C module, which are utilized on the four adjacent sides of the 1U CubeSat, are presented in Table 2 and Table 3.

The mathematical expressions for the PV module, based on the 1D/2R model and the five-currents determination from Table 2 and Table 3, are derived as follows: The photovoltaic current (Iph) is dependent on the incident solar irradiance (G) and the cell temperature (T). Here, Iph represents the current directly proportional to incident solar irradiation and temperature. ID: This is the current that flows through the diode (diode current), representing the recombination and diffusion losses within the p-n junction of the solar cell. It is described by the Shockley diode equation. Irs is the reverse saturation current under reverse bias. IP is the shunt current, representing the losses due to leakage paths in the cell, such as manufacturing defects or impurities. The output current (Ipv) represents the net current flowing through the series resistor. These five currents are tabulated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Five currents involved in 1D/2R PV modeling.

Each side is fitted with two Azur Space 3G30C solar modules connected in parallel for the CubeSat design. This configuration forms larger panels on each side. Opposite large panels are then connected in parallel to form two groups: the (+X, −X) and the (+Y, −Y) groups. The top and bottom sides are fitted with eight small Spectrolab TASC cells, which are all connected in parallel to form a (+Z, −Z) group. Each Azur Space 3G30C module outputs 2457 mV and 442.8 mA at the MPP under STCs. When two Azur Space 3G30C modules are connected in parallel on an X- or Y-configuration panel side, they collectively yield a voltage output of 2411 mV and a total current output of 885.6 mA at the MPP. The Z-configuration’s top or bottom side, with its eight Spectrolab TASC cells, provides a voltage output of 2.2 V and a total current of 112 mA at the MPP, resulting in a total of 224 mA for the (+Z, −Z) group.

When modeling a photovoltaic (PV) cell in Simulink, accurately initializing key parameters is essential to ensure that the model produces realistic and reliable outputs. Parameters such as the diode ideality factor (n), electron charge (q), Boltzmann constant (k), and bandgap energy (Eg0) define the fundamental semiconductor behavior, while resistive elements, including the series resistance (Rs) and shunt resistance (Rp), capture the practical non-idealities of the PV device. Temperature (Tn) directly influences the thermal voltage and saturation current, thereby affecting both the open-circuit voltage (Voc) and maximum power point prediction. Similarly, the short-circuit current (Isc) and photocurrent temperature coefficient (ki) establish the light-generated current under specified conditions. Correct initialization of these values prevents numerical instabilities in the algebraic loops of the Simulink solver, avoids unrealistic current–voltage characteristics, and ensures that the simulated PV performance closely matches the expected physical behavior. This practice is essential when analyzing PV modules under varying irradiance and temperature conditions, as minor inaccuracies in initial parameters can propagate into significant deviations in output power and efficiency predictions. As shown in Figure 2, there are two Azur Space 3G30C modules on each of the four sides.

Figure 2.

Exploded view of a 1-U CubeSat design.

2.1.2. Photovoltaic Solar Module Modeling in MATLAB/Simulink

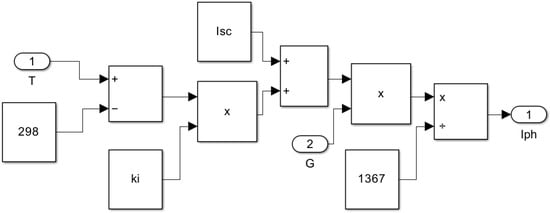

The mathematical models described above were systematically implemented in MATLAB/Simulink to create a comprehensive PV module simulation. The development process involved constructing subsystems for each of the five current equations and then integrating them into a unified PV cell model. The photocurrent model, based on Equation (2), is depicted in Figure 3. This subsystem inputs temperature (T) and solar irradiance (G) to calculate Iph. This model is fundamental as it establishes the initial current generated by the PV cell (Figure 3). This subsystem inputs temperature (T) and solar irradiance (G) to calculate Iph. This model is fundamental as it establishes the initial current generated by the PV cell.

Figure 3.

Photocurrent Simulink model.

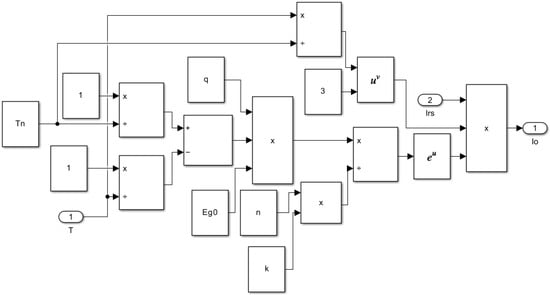

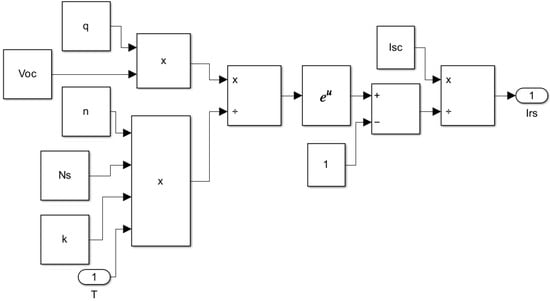

The saturation/diode saturation current model, governed by Equation (3), is shown in Figure 4. This model is crucial for understanding the temperature-dependent behavior of the diode’s saturation current.

Figure 4.

Diode saturation current model.

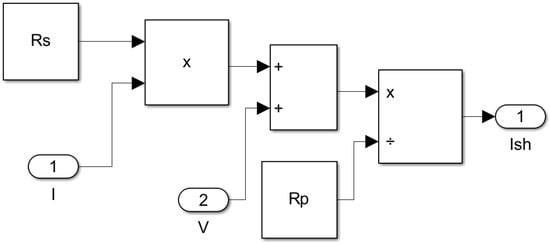

The parallel/shunt resistor current model, derived from Ohm’s law (Equation (4)), is illustrated in Figure 5. This subsystem captures the losses due to leakage current within the PV cell.

Figure 5.

Parallel/shunt resistor current model.

The reverse saturation current model, based on Equation (5), is presented in Figure 6. This model is integral for characterizing the behavior of the diode under reverse bias conditions.

Figure 6.

Reverse saturation current model.

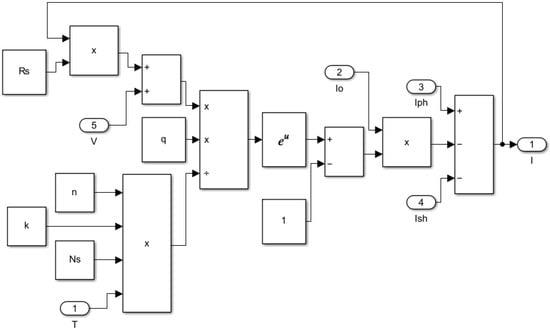

Finally, the output current model, which consolidates the contributions of the photocurrent, diode current, and shunt current to yield the net output current of the PV cell (Equation (6)), is depicted in Figure 7. These subsystems (Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7) are combined to form the complete solar PV cell model. This combined subsystem takes temperature and irradiance as inputs. A critical step in this integration is converting the Celsius input temperature to Kelvin, which is handled by an additional block. This final model takes irradiance (G) and temperature (T) as its primary inputs and outputs the crucial I-V and P-V characteristic curves, which are essential for simulating the performance of the PV module under various operating conditions.

Figure 7.

Output current model.

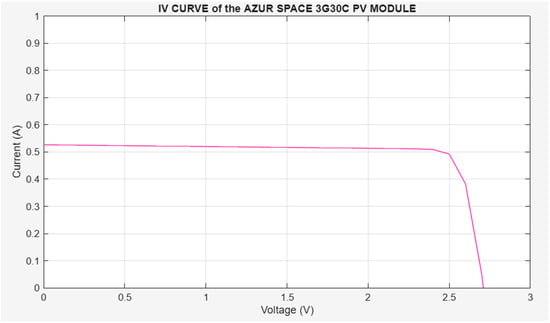

Figure 8 shows all five current subsystems interconnected to form a PV module. The simulation results of the I-V model are depicted in Figure 9, where the x-axis represents the voltage from 0 V to VOC (2.7 V), and the y-axis represents the current from 0 A to ISC (0.470 A) [12]. The shunt resistance: ; the thermal voltage: ; and the shunt resistance: .

Figure 8.

Combined subsystems of the solar PV cell.

Figure 9.

IV curve of the 3G30C PV module.

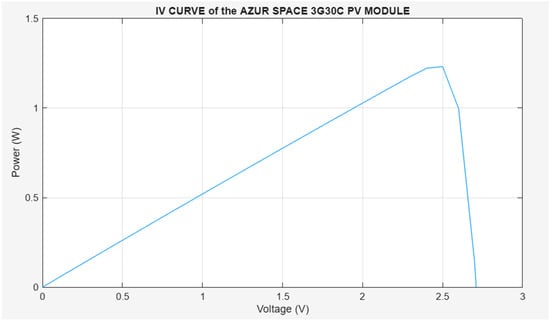

Figure 10 displays the simulation results of the P-V model, with the x-axis representing the voltage from 0 V to VOC (2.7 V) and the y-axis representing the power from 0 W to Pmax (1 W). These characteristic curves are crucial for maximum power point tracking (MPPT) algorithms to dynamically adjust the operating point and maximize energy harvesting.

Figure 10.

PV curve of the 3G30C PV module.

2.2. Boost Converter Modeling in Simulink (5 V Bus)

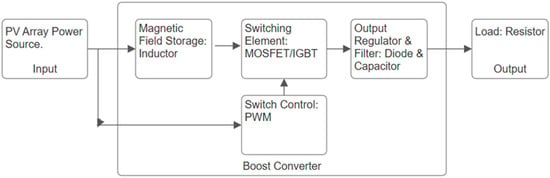

The boost converter’s output voltage is more than the input voltage. DC-DC converters are smaller in mass than linear converters. Hence, they are highly efficient and cheap to construct.

The solar PV panel voltage is the source voltage and changes proportionally to solar irradiance and temperature. It is in the left block of Figure 11. The input inductor acts as a magnetic field storage device and is the next stage from the PV array output of Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Boost converter basic block diagram.

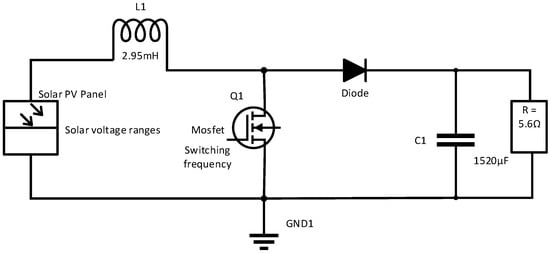

The MOSFET acts as a switching element driven on and off by the pulse width modulator (PWM) on its gate and drain inputs. It is connected to the magnetic field storage (inductor) in Figure 11. The diode acts as an output regulator, and the output capacitor acts as an output filter, which are connected in series between the drain and the source of the MOSFET in Figure 12. The desired inductor ripple current and desired ripple output voltage are inversely proportional to the inductance and capacitance, which means the smaller the desired ripples, the larger the inductor and capacitor values. The boost converter has two modes, i.e., mode one is when the MOSFET is on, and mode two is when the MOSFET is off. The MOSFET is switched on and off by a square wave of the pulse width modulator (PMW). The duty cycle of the switching square wave is determined by the input and output voltages, and the duty cycle is inversely proportional to the output voltage. When designing a boost converter, the values of the inductor ripple current and capacitor ripple voltage, square wave switching frequency, load voltage, load resistance or load current, and solar PV panel output voltage range are preselected and kept constant. Then, boost converter design equations are used to calculate the input inductor and output capacitor values. The DC-DC step-up components’ calculations are for the worst-case design scenario of the CubeSat. The worst-case scenario occurs when two sides of the CubeSat point toward the sun, resulting in four modules being active.

Figure 12.

Boost converter circuit diagram.

A configuration where two sides of the CubeSat are pointed to the sun is simulated by the (+X, +Y) or (−X, −Y) groups. The (+X, +Y) or (−X, −Y) group gives a voltage output of 2.4 V and a total current of 1.8 A. The solar array has four modules connected in parallel. This array is an input of the boost converters. The desired outputs of the boost converters are 3.3 V and 5 V, as determined by the desired bus load voltages. Each (+X, +Y) or (−X, −Y) group (two adjacent sides) is connected to either a 5 V boost converter or a 3.3 V boost converter. These design calculations are for the worst-case scenario when two sides of the one-unit CubeSat are exposed to the sun. The specification of the PV array is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

PV array parameters.

The boost converter specification is shown in Table 6, and Appendix A provides the boost converter input voltage () and current ().

Table 6.

Boost converter specification.

2.3. Motivation for Design of Hybrid PO-PSO MPPT

Among the four conventional maximum power point tracking (MPPT) methods—perturb and observe (PO), fractional short-circuit current (FSCC), fractional open-circuit voltage (FOCV), and incremental conductance (IC)—research has increasingly integrated artificial intelligence (AI) techniques like fuzzy logic and neural networks to enhance their performance. Under steady-state weather, IC demonstrates the highest efficiency with minimal power losses and the fastest convergence during rising temperatures. Conversely, FOCV excels under falling temperatures and in dynamic conditions, given the slow variation in the open-circuit voltage with temperature. At the same time, FSCC performs poorly due to the significant influence of fluctuating weather on the saturation current. Although PO is the simplest to implement in hardware and software, its fixed sampling rate makes it the least efficient in dynamic environments. In terms of complexity, IC is the most demanding, requiring dual sensors for voltage and current. Both FOCV and FSCC offer a more straightforward software implementation but necessitate additional sensor hardware and rely on a constant approximation rather than directly locating the actual maximum power point, which limits their precision compared with IC and PO [9].

Since PO is limited to poor tracking of the GMPP under dynamic weather conditions and pronounced oscillations around the MPP, it is combined with PSO MPPT. The standalone PSO MPPT is inherently a probabilistic algorithm and uses multiple particles (swarm) to search for the MPP. The algorithm suffers from a slow convergence rate, particularly at the beginning of the search, where it initially converges very slowly. Moreover, it tends to overshoot and undershoot around the MPP under rapid temperature changes, causing inefficiencies in PV output regulation. The summary of the comparison of MPPT techniques is shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Summary of the comparison of MPPT techniques.

The advantages of the hybrid MPPT are as follows: tracking of the global maximum power point (GMPP) under fast-changing temperature conditions, damping of oscillations around the GMPP, increased efficiency of PV power extraction, a fast response time, a fast convergence time, and generally decreased power losses. In the hybrid MPPT, a faster response time is proportional to huge oscillations around the MPP and inversely proportional to the tracking efficiency of the GMPP. The disadvantages of the hybrid MPPT techniques are high computation complexity since they employ bio-inspired AI algorithms, and the hardware implementation of the hybrid includes additional hardware components such as proportional–integral–derivative (PID) controllers and sliding-mode controllers; thus, hardware complexity is increased. Increased hardware and software complexities are non-ideal for CubeSat applications with a limited volume and mass. The absence of a dedicated microprocessor for EPS is another limitation to implementing hybrid MPPTs for a CubeSat application. Hence, a low-complexity classical MPPT such as PO is desirable to be combined with a low-complexity AI technique such as PSO.

2.4. PO MPPT Algorithm and MATLAB/Simulink Model

The MPPT function measures both the voltage and the current produced by the PV module and computes the input power of the MPPT function. The MPPT function is implemented as a MATLAB function whose code is written as a script file. The PV input voltage, current, power, and boost converter output voltage, current, and power are monitored in real-time. The simulations assume the worst-case scenario, where two sides of the 1U CubeSat face the sun. This means the array consists of four parallel, connected modules. The PO function perturbs the power in one direction, and if the power continues to increase, the PO continues to perturb in the same direction. If the perturbed new power value is less than the old one, it will perturb in the opposite direction.

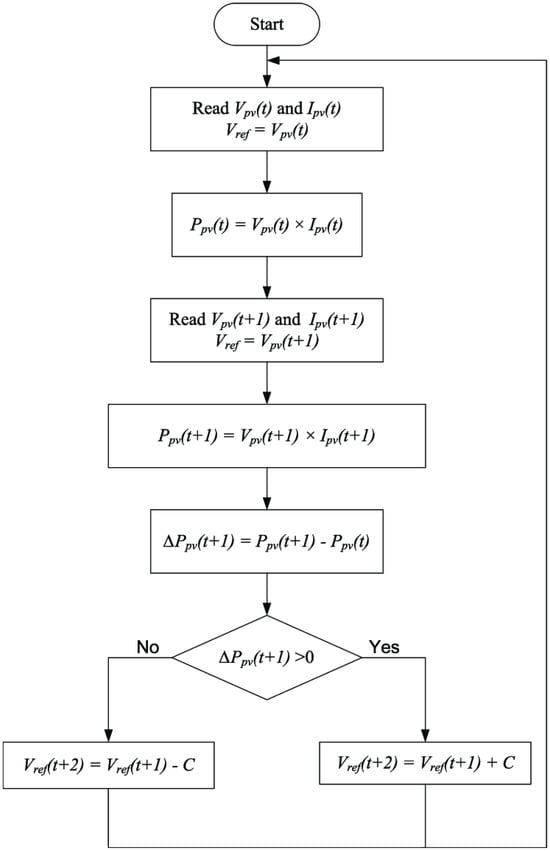

To design a Simulink dynamic input that simulates varying temperatures between −100 °C and +120 °C, the formula implemented in Simulink is [13]. The temperature PV input must be changed into a dynamic input that randomly varies the temperature between −100 °C and +120 °C, thus simulating the dynamic temperature variation in the low-Earth-orbit space. The temperature changes randomly to any value within one second at sample periods of 0.1 s. The provided flowchart illustrates the operational principle of a perturb and observe (PO) maximum power point tracking (MPPT) algorithm, designed to continuously adjust a photovoltaic (PV) module’s voltage to extract maximum power. The process begins by reading the initial PV voltage and current to compute the initial power. In the subsequent time step, the system measures a new voltage and current to compute the new power. A core component of the algorithm is the determination of the change in power by subtracting the old power from the new power. This value dictates the direction of the next perturbation. If the power has increased, the algorithm continues to perturb the reference voltage in the same direction by adding a small constant. Conversely, if the power has decreased or stayed the same, the algorithm reverses the perturbation direction by subtracting the constant. This iterative process allows the system to seek the peak of the power–voltage curve continuously. The MPPT function is implemented as a MATLAB script, enabling real-time monitoring of PV input and boost converter output parameters. This simulation is designed to test the algorithm under worst-case scenarios, such as a CubeSat with multiple solar arrays simultaneously facing the sun, to ensure robust performance. Depicted in Figure 13 is the flowchart of the PO MPPT function. On the left is a negative perturbation, and on the right is a positive perturbation.

Figure 13.

The basic flowchart of the PO MPPT function.

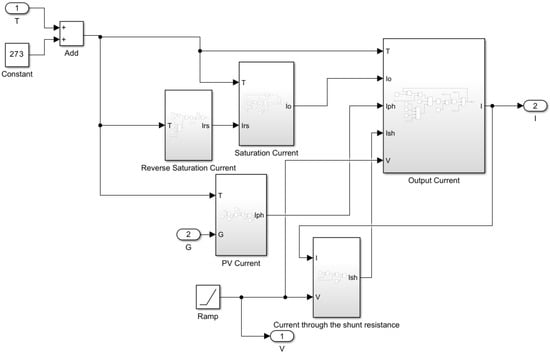

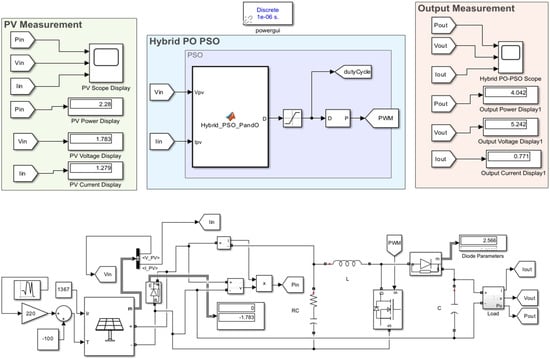

The gain block is set to 220, representing the maximum space temperature, and the constant block is set to −100, representing the minimum space temperature. The random number block is set to a sampling time of 0.1 s to change the temperature randomly every 0.1 s, as shown in Figure 14. The PO-PSO MPPT average DC voltage is 5.242 V, the average DC power is 4.042 W, and the average DC current is 0.771 A in the given simulation time of one second.

Figure 14.

PO-PSO MPPT MATLAB/Simulink model under varying temperature conditions and constant irradiation (1367 W/m2).

2.5. PSO MPPT Algorithm and MATLAB/Simulink Model

The MATLAB MPPT function code implements a PSO algorithm for adjusting the duty cycle D of the boost converter based on the input voltage Vpv and current Ipv of a PV array. The goal is to maximize the power output of the boost converter by finding the optimal duty cycle D using the PSO algorithm.

Step 1: Particle Initialization

The ‘persistent’ is used to retain the values of the variables between function calls, allowing the algorithm to maintain state and progress over multiple iterations. The variables ‘u,’ ‘dcurrent,’ ‘pbest,’ ‘p,’ ‘dc,’ ‘v,’ ‘counter,’ and ‘gbest’ are initialized on the first function call.

Step 2: Delay Mechanism

The function uses a counter to delay the execution of the PSO algorithm by returning the current duty cycle without modification until a certain number of iterations (‘counter’ reaches 300) have passed.

Step 3: Fitness Evaluation

The fitness of each particle is calculated as the power output: Vpv × Ipv. If the current power output is greater than the previous best, ‘pbest’, the best position of the particle is updated to the current duty cycle. PSO algorithm parameters are described in Table 8.

Table 8.

PSO algorithm MATLAB MPPT function variables’ description.

Step 4: Particle Update

The function cycles through each particle (‘u’, ranging from 1 to 4) to update their duty cycles (‘D’), velocities, and positions. If ‘u’ reaches 4, the algorithm finds the particle with the highest power output (‘gbest’), updates the global best duty cycle, and recalculates the velocities and positions of the particles.

Step 5: Velocity and Duty Cycle Update

The velocity of each particle is updated using the PSO velocity update formula: v final = w ∗ v + c1 ∗ rand () ∗ (pbest − d) + c2 ∗ rand () ∗ (gbest − d).

Step 6: Final Output

After all updates, the final duty cycle (‘D’) is returned. To measure the average DC voltage, power, and current for PSO MPPT, the sampling time is set to 0.1 s, and the simulation time is 1 s.

2.6. Hybrid PO-PSO MPPT Algorithm and MATLAB/Simulink Model

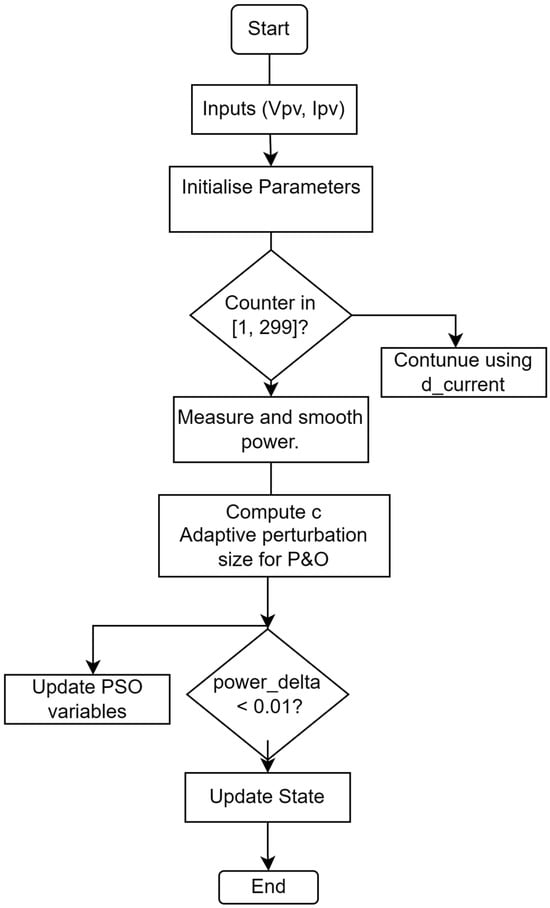

The hybrid code integrates both the global search capability of PSO and the fine-tuning capability of PO. When the system is close to the optimum (small changes in power), the PO algorithm takes over. Otherwise, the PSO algorithm explores the solution space broadly. The decision to switch between the PO function and the PSO algorithm is based on the magnitude of the change in the power output. The hybrid approach mitigates the problem of poor tracking of the GMPP in dynamic environments.

2.6.1. Hybrid PO PSO MPPT Algorithm Function Steps

- Step 1: Persistent Variables, Particle Initialization, and Delay

The PSO initialization is used as provided before in Section 2.5. Variables are initialized to track the state of the PO method, using persistent variables to store values between function calls to maintain the algorithm state. A delay is introduced to allow the system to stabilize.

- Step 2: Power Calculation and Error Calculation

The PSO approach is used to explore and calculate the power at each duty cycle. T previous and current power values are tracked.

where

P = Vpv ∗ Ipv

- Vpv is the photovoltaic (PV) panel voltage;

- Ipv is the PV panel current.error = abs (Vout − target_voltage)

where

- Vout is the output voltage of the boost converter;

- target_voltage is the desired output voltage.

- Step 3: Fitness Function and Perturb and Observe

A fitness value is computed based on the inverse of the error.

fitness_value = 1/(error + epsilon)

Perturb and observe function:

if P_new > P_old: Y = Yin + c else: Y = Yin − c

- Step 4: Hybrid Decision

If the system detects small changes in power (indicating a steady state), it switches to the PO algorithm for finer adjustments. If larger variations in power are detected (indicating potential suboptimal performance), it reverts to PSO to explore a broader range of duty cycles.

- Step 5: Velocity and Duty Cycle Update

The velocity of each particle is updated using the PSO velocity update formula:

where

v_final = w ∗ v + c1 ∗ rand() ∗ (pbest − d) + c2 ∗ rand() ∗ (gbest − d).

- v_final: updated velocity;

- w: inertia weight;

- v: current velocity

- c1, c2: cognitive and social parameters;

- pbest: personal best position;

- d: current duty cycle;

- gbest: global best position.

The duty cycle is updated based on the new velocity, ensuring it remains within the bounds [0, 1].

where

d_final = max(0, min(1, d + v_final))

- d_final: updated duty cycle;

- d: current duty cycle;

- v_final: updated velocity.

- Step 6: Return Updated Duty Cycle

The updated duty cycle D is returned based on the hybrid logic. The PV output power, voltage, and current are connected to the scope and the display for displaying average DC levels. At the top center is the hybrid PO PSO MPPT MATLAB/Simulink function, which tunes the PWM duty ratio to maximize PV power extraction, and next to it is the ‘To Workspace’ function, which takes the PV voltage and current from the model to the workspace so that the hybrid PO PSO MATLAB function can use them to calculate power. At the bottom center is the boost converter model, which regulates the load voltage. At the far right are the load measurements, where the load power, voltage, and current are connected to the scope and displays.

2.6.2. Hybrid PO PSO MPPT Function Algorithm Flow-Chart

Figure 15 illustrates the flowchart of the hybrid PO-PSO MPPT function.

Figure 15.

The basic flowchart of the Hybrid PO-PSO MPPT function.

3. Results

The provided results, encompassing Table 9, offer a comprehensive time-domain performance comparison of the perturb and observe (PO), particle swarm optimization (PSO), and hybrid PO-PSO maximum power point tracking (MPPT) algorithms under constant temperature (28 °C) conditions and constant irradiation at 1367 W/m2.

Table 9.

Comparison of MPPTs under constant irradiation and temperature.

The constant irradiation is 1367 W/m2, and the constant temperature is 28 °C for LEO standard test conditions. Those values are set by constant blocks in Simulink. As can be seen from Table 9. The hybrid PO-PSO MPPT outperforms the PSO and the hybrid PO MPPTs in all the performance metrics in Table 9. Hybrid PO-PSO MPPT yields more power and faster MPP tracking accuracy (%) under the constant conditions set up.

Table 9 shows a comparison of MPPTs under constant irradiation and temperature. Now, the irradiation is kept constant at 1367 W/m2, and the temperature randomly varies between −100 °C and +120 °C to mimic low-Earth-orbit space weather. As can be seen from Table 10, the hybrid PO-PSO MPPT outperforms the PO and the PSO MPPTs in yielding more power, voltage, and current. The hybrid PO-PSO MPPT under the varying temperatures is superior in terms of MPP tracking accuracy, followed by the PSO MPPT. The PO MPPT has a slower convergence time (0.1 s) under the varying condition, whereas under the constant condition, it matches the hybrid and the PSO (0.001). The hybrid and the PSO still maintain the same convergence time (0.001 s) as under the constant condition.

Table 10.

MPPTs’ comparison under constant irradiation and varying temperature.

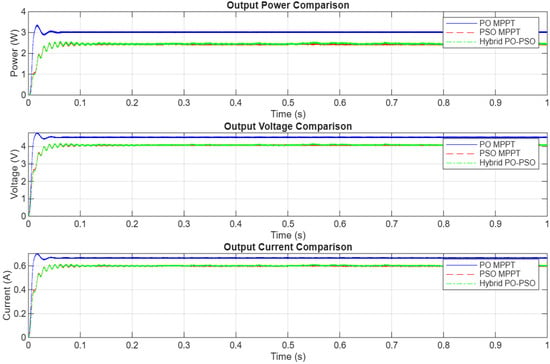

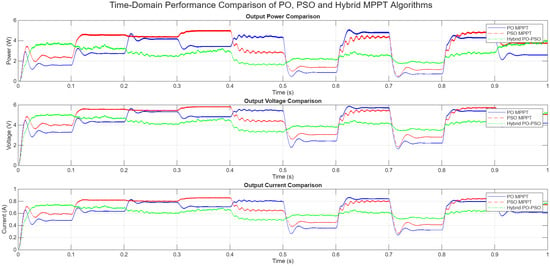

Figure 16 shows the comparisons of the Hybrid, PO, and PSO MPPT techniques under fixed irradiation and temperature. The hybrid PO-PSO MPPT is the best-performing MPPT function compared with the PO MPPT and PSO MPPT under temperature-varying conditions, as shown in Figure 17, due to its dual-search capability. It starts by using the PSO MPPT function to search a vast solution space, and when it is close to the global maximum power point (GMPP), it switches to the actual seeking PO MPPT function. It smoothens the oscillations at the GMPP and yields the highest power output under temperature-varying conditions, as seen in Figure 17.

Figure 16.

Comparison of PO, PSO, and PO-PSO MPPTs under constant conditions.

Figure 17.

Time-domain performance comparison of PO, PSO, and PO-PSO MPPTs.

3.1. Oscillations Around the Global Maximum Power Point (GMPP)

- PO MPPT (blue solid line): Figure 17 clearly illustrates that the PO MPPT exhibits significant and continuous oscillations around the GMPP for all three output parameters (power, voltage, and current). These oscillations are characterized by a large peak-to-peak amplitude, indicating a persistent perturbation around the MPP without achieving a truly stable operating point. This inherent characteristic of PO leads to considerable power loss and reduced overall efficiency, as the system constantly hunts for the MPP. For instance, in the output power comparison, the PO MPPT consistently fluctuates, with visible peak-to-peak variations around its average power output, particularly noticeable during steady-state periods.

- PSO MPPT (red dashed line in Figure 17): The PSO MPPT demonstrates a notable improvement in damping these oscillations compared with PO. While oscillations are still present, their peak-to-peak amplitude is visibly reduced, and the system appears to converge more effectively toward a stable operating point. However, some fluctuations remain, especially during transient periods (e.g., around 0.4 s and 0.7 s in Figure 17), suggesting that while PSO offers better global search and convergence, it may not eliminate minor oscillations or fine-tune as precisely as desired.

- Hybrid PO-PSO MPPT (green dashed–dotted line in Figure 17): The hybrid PO-PSO MPPT exhibits the most superior performance in terms of damping oscillations around the GMPP. The output waveforms are significantly smoother, with a minimal peak-to-peak amplitude of oscillations, particularly after the initial convergence phase. This indicates that the hybrid approach effectively smoothens the oscillations at the GMPP, leading to a much more stable and consistent power output. The dual-search capability, where PSO performs a broad search for the GMPP and PO and then fine-tunes the tracking, is highly effective in achieving enhanced stability and reduced oscillation.

3.2. Settling Time

- PO MPPT: The PO MPPT demonstrates a relatively slow settling time when subjected to changes in environmental conditions (implied by the step changes in output around 0.4 s and 0.7 s in Figure 17). The algorithm takes a longer duration to respond and attempt to approach a new operating point, and even then, it continues to exhibit persistent oscillations.

- PSO MPPT: The PSO MPPT in Figure 17 generally exhibits a faster settling time than PO, converging more quickly toward a new MPP after a disturbance. This is a direct benefit of its global optimization capabilities, allowing it to explore the search space more efficiently.

- Hybrid PO-PSO MPPT: The hybrid PO-PSO MPPT consistently achieves the fastest settling time to the new GMPP following changes in conditions. Its ability to quickly identify the optimal point and then stabilize with minimal oscillations is a significant advantage, ensuring rapid adaptation to dynamic environments and maximizing energy capture during transitions.

3.3. Overshoot and Undershoot

- The PO MPPT displays significant overshoot and undershoot during transient periods (when the temperature conditions change, causing the power/voltage/current to drop and then recover). These large deviations from the optimal operating point are a consequence of its inherent perturbation mechanism and contribute to power losses.

- PSO MPPT: The PSO MPPT generally shows less pronounced overshoot and undershoot compared with PO, indicating a more controlled and stable response to changes in operating conditions.

- Hybrid PO-PSO MPPT: The hybrid PO-PSO MPPT demonstrates the best performance in minimizing both overshoot and undershoot. The transitions between different operating points are notably smoother and more controlled, reflecting the algorithm’s superior ability to maintain proximity to the true MPP throughout dynamic changes.

3.4. Overall Performance and Damping

- The hybrid PO-PSO MPPT consistently yields the highest power output (4.042 W), voltage (5.242 V), and current (0.771 A) under varying temperature conditions. This quantitative superiority directly correlates with its enhanced damping of oscillations and more efficient power extraction.

- The substantial percentage improvements (55.05% for power, 24.12% for voltage, and 24.13% for current) between PO and hybrid PO-PSO unequivocally confirm the effectiveness of the hybrid approach in enhancing overall system performance and damping undesirable fluctuations around the GMPP.

- The dual-search capability of the hybrid method, which intelligently switches between PSO for broad exploration and PO for precise fine-tuning, is the fundamental reason for its superior damping characteristics and its ability to maintain stable operation consistently near the GMPP, even under challenging and dynamic environmental conditions. This makes it a highly robust and efficient solution for CubeSat energy harvesting.

The hybrid PO-PSO maximum power point tracking (MPPT) algorithm demonstrates superior performance compared with conventional methods. It achieves a significantly higher power output of 13.07 W, representing a 398.4% improvement over the perturb and observe (PO) algorithm. Furthermore, the hybrid approach effectively reduces oscillations around the global maximum power point (GMPP), resulting in a smoother and more stable waveform. Table 11 shows a summary of key metrics under varying temperature conditions.

Table 11.

Shows a summary of key metrics under varying temperature conditions (irradiation = 1367 W/m2).

In addition to enhancing power performance, it also improves voltage (102.6%) and current stability by approximately 146.1% relative to PO. This method successfully balances tracking speed and accuracy, exhibiting a fast rise time coupled with a low settling time, which contributes to its overall efficiency and reliability in photovoltaic energy conversion. Table 12 shows the percentage improvement of the novel hybrid over PO MPPT.

Table 12.

Output comparison between PO, PSO, and PO-PSO MPPTs.

3.5. Simulation of Hybrid PO-PSO Under Varying Irradiation and Temperature Conditions

The simulation time is 100 s to represent the sunlight time of the orbit. In the eclipse of the orbit, there is no irradiation and zero power generation. Hence, a battery system is used to power the satellite during the eclipse time. The average irradiation is 900 W/m2, and the range is 300 W/m2. The average temperature is 20 °C, and the range is 40 °C. There is an m-file that creates a step change in the temperature and irradiation every 0.1 s. The powergui is set to , from a switching frequency of 500 kHz, , , and . The irradiation and the temperature data from the workspace are connected as an input to the PV arrays in Simulink. A single PV array represents one side of the CubeSat. The hybrid reached 48.5% of the theoretical MPP of 4.96 W.

Table 13 shows a comparison of MPPTs under varying irradiation and temperature conditions. The hybrid does not reach 95% of the theoretical MPP of 4.96 W since the average radiation is far less than the theoretical or STC radiation of 1367 W/m2. Hence, the convergence speed cannot be determined for changing irradiation. A sensitivity analysis was performed on the hybrid PO–PSO MPPT model under irradiation dips of 5%, 10%, and 20% relative to the average irradiance of 900 W/m2 (Table 14). The results demonstrate that the output power exhibits a near-linear reduction proportional to the irradiance decrease, with a 5% dip causing only marginal power degradation, while 20% dips lead to significant losses in harvested energy. The output voltage remains relatively well regulated around the 5 V target, confirming the hybrid controller’s ability to stabilize the DC bus despite input fluctuations. However, the output current is more sensitive to irradiation dips, decreasing noticeably with larger reductions in the solar input. Overall, the hybrid MPPT proves robust in voltage regulation but shows proportional sensitivity in current and power yield, particularly under severe irradiation deficits.

Table 13.

Comparison of MPPTs under varying irradiation and temperature conditions.

Table 14.

Hybrid PO–PSO MPPT model sensitivity analysis.

4. Discussion

The simulations demonstrate that while the direct tracking perturb and observe (PO) and metaheuristic particle swarm optimization (PSO) methods are effective in tracking the maximum power point, their performance is surpassed by the hybrid PO-PSO approach. Under constant weather conditions, the PO MPPT algorithm provided a higher yield of power, voltage, and current, outperforming both the PSO and hybrid PO-PSO methods. Its superior performance in a stable environment is attributed to its direct tracking nature, which quickly and efficiently converges to the MPP without significant oscillations once the steady state is reached.

However, the PO algorithm begins to suffer under dynamic weather conditions, where its performance metrics, including power, voltage, and current output, decrease. In contrast, under these more challenging, dynamic scenarios, the hybrid PO-PSO MPPT demonstrates superior performance. Specifically, under varying temperatures, the hybrid method consistently yields a higher output in terms of power, voltage, and current than both the PO and PSO algorithms. The hybrid’s superiority is further highlighted by its faster convergence speed and improved MPP tracking accuracy, as detailed in the simulation results tables. This enhanced stability and faster response are critical for ensuring the reliable operation of the CubeSat’s electrical power system, which must handle a variety of atmospheric and load conditions.

The results of this study benchmark favorably against the existing literature. The hybrid PO-PSO algorithm’s superior performance in reducing power ripple and enhancing tracking accuracy is consistent with the findings of [6,7,14]. The simulation demonstrates that the hybrid approach provides a clear advantage in a CubeSat’s photovoltaic system by mitigating the persistent power wastage issues observed in traditional MPPT methods.

Future work could focus on injecting the temperature and irradiation inputs of the PV array with real-time low-earth-orbit space weather data to simulate the PV system response in real time and verify the adaptability of the hybrid PO-PSO MPPT. Practical validation of the results achieved in this work is recommended to be tested on CubeSats’ EPS hardware development. The hybrid PO-PSO MPPT can incorporate two-step prediction models that combine perturbation techniques with learning-based adjustments to reduce tracking oscillations and computation time under dynamic irradiance conditions, and this work can be adapted for a 3-U CubeSat with a dedicated microprocessor for the EPS to handle advanced MPPT algorithms with machine learning [15].

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated a hybrid perturb and observe–particle swarm optimization (P&O–PSO) algorithm for maximum power point tracking (MPPT) in CubeSat photovoltaic (PV) systems through time-domain modeling and simulation. The simulation findings for the hybrid P&O–PSO MPPT worked better than traditional P&O in terms of tracking accuracy, convergence speed, and robustness under a variety of temperature and irradiance profiles that are typical of CubeSat orbital settings. The hybrid model outperformed the independent PO and PSO techniques under dynamically variable space weather conditions, achieving faster convergence to the global maximum power point (GMPP), minimizing steady-state oscillations, and improving energy harvesting and system reliability. This research work recommends that the time-domain framework provides a valuable tool for evaluating MPPT algorithms under practical operating conditions, making it suitable for CubeSat missions as well as other space-constrained PV systems. In conclusion, by optimizing available photovoltaic power under the demanding and dynamic conditions of space, the proposed hybrid P&O–PSO MPPT technique provides a viable way to enhance energy autonomy in CubeSats, directly supporting mission objectives. The MATLAB function code for PO MPPT, PSO MPPT, and PO-PSO MPPT is prepared in a separate file and will be uploaded separately as Supplementary Materials for additional information.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/en18225957/s1, The MATLAB function code for PO MPPT, PSO MPPT, and PO-PSO MPPT is prepared in a separate file and will be uploaded separately as Supplementary Materials for additional information.

Author Contributions

K.N.D. and S.K.: conceptualization, methodology, and editing; S.K. and H.M.: supervision, visualization, project administration, funding acquisition, and writing—review and editing; K.N.D.: software, validation, resources, and data; K.N.D., S.K. and H.M.: formal analysis and investigation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the MerSETA Research Fund and the Walter Sisulu Study Subsidy Fund. This work was supported in part by the National Research Foundation (NRF) under Thuthuka Grant 138177, in part by the Eskom Tertiary Education Support Program (TESP) through a research grant, and in part by the Eskom Power Plant Engineering Institute (EPPEI).

Data Availability Statement

The data are for the mathematical modeling of the 3G30C AZURE SPACE CubeSat PV module using a two-resistor/one-diode model in MATLAB/Simulink. Two 3G30C AZURE SPACE modules fit on one out of four adjacent body sides of the CubeSat. The top and the bottom sides are equipped with SPECTROLAB PV modules. The boost converter model is simulated for the worst-case scenario where only two adjacent body sides are exposed to the sun. Hence, only four AZURE SPACE modules are connected in parallel to form a 4 × 1 array, which supplies power to the boost converter. Suggested data are available in Section 2.1 “Azur Space 3G30C PV Module Modelling” at https://esango.cput.ac.za/articles/dataset/Modelling_and_simulation_of_the_cube_satellite_power_systems/27723120?file=50483769 (Accessed 15 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank my supervisors, S. Krishnamurthy and Haltor Mataifa, for their guidance and advice. The Center for Intelligent Systems and Emerging Technologies (CISET) and the CPUT Library management and staff are acknowledged for their support, resources, and assistance with the information needed for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of this manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations were used in this manuscript:

| 1U | One Unit |

| ACO | Ant Colony Optimization |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ANFIS | Artificial Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| BOL | Beginning of Life |

| CubeSat | Cube Satellite |

| DE | Differential Evolution |

| EPS | Electrical Power System |

| FL | Fuzzy Logic |

| FOCV | Fractional Open-Circuit Voltage |

| FSCC | Fractional Short-Circuit Current |

| GMPP | Global Maximum Power Point |

| InC | Incremental Conductance |

| MGWO | Modified Grey Wolf Optimization |

| MPP | Maximum Power Point |

| MPPT | Maximum Power Point Tracking |

| OBC | Onboard Computer |

| PO | Perturb and Observe |

| PO-PSO | Perturb and Observe–Particle Swarm Optimization |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| TSA | Tunicate Swarm Algorithm |

| SMO | Slime Mould Optimization |

| EPS | Electric Power System |

| HHA | Hyper Heuristic Algorithm |

| TT&C | Telemetry Tracking and Command |

| ADCS | Attitude Determination and Control System |

| DET | Direct Energy Transfer |

| BCR | Battery Charge Regulator |

| 1D/2R | One-Diode/Two-Resistors model |

| EO | Equilibrium Optimizer |

| DFO | Dragon Fly Optimization |

| FSSO | Flying Squirrel Search Optimization |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| PID | Proportional–Integral–Derivative |

| FLC | Fuzzy Logic Controller |

| NN | Neural Network |

| DC | Direct Current |

| PMW | Pulse Width Modulation |

| LEO | Low Earth Orbit |

| STCs | Standard Test Conditions |

Appendix A. Boost Converter Input Voltage () and Current ()

Let us assume that the boost converter operates at the maximum power point of the PV array.

Let us assume that the boost converter operates at 90% efficiency:

The ripple current is 5% of the input current:

The ripple voltage is 1% of the output voltage:

Summary of calculated values:

- Inductance: 24.88 mH;

- Capacitance: 18.22 μF.

References

- Zhan, D.; Tian, A.-Q.; Ni, S.-Q. Optimizing PIDcontrol for multi-model adaptive high-speed rail platform door systems with an improved metaheuristic approach. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 169, 110738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudrhiri, K.; Yang, O.; Buccino, D.; Kahan, D.; Withers, P.; Tortora, P.; Matousek, S.; Lay, N.; Lazio, J.; Krajewski, J.; et al. MarCO Radio Occultation: How the First Interplanetary CubeSat Can Help Improve Future Missions. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 7–14 March 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollipo, R.B.; Mikkili, S.; Bonthagorla, P.K. Critical Review on PV MPPT Techniques: Classical, Intelligent and Optimisation. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2020, 14, 1433–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kashyap Hegade, K.S.; Ankith, D.H.; Prabhu, G.K.; Divya, S.; Geetha, R.S. Preliminary Design and Simulation of the Electrical Power System for a CubeSat Using LTspice. In Proceedings of the 2021 7th International Conference on Space Science and Communication (IconSpace), Selangor, Malaysia, 23–24 November 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, A.F.; Sher, H.A.; Chiaberge, M.; Boero, D.; De Giuseppe, M.; Addoweesh, K.E. Comparative analysis of maximum power point tracking techniques for PV applications. In Proceedings of the 2013 16th International Multi Topic Conference (INMIC), Lahore, Pakistan, 19–20 December 2013; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabia, D.E.; Afghoul, H.; Kraa, O.; Himeur, Y.; Ramadan, H.S.; Genc, I.; Idriss, A.I.; Miniaoui, S.; Atalla, S.; Mansoor, W. Experimental validation of a novel hybrid Equilibrium Slime Mould Optimization for solar photovoltaic system. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwar, S.; Javed, M.Y.; Jaffery, M.H.; Arshad, J.; Ur Rehman, A.; Shafiq, M.; Choi, J.-G. A Novel Hybrid MPPT Technique to Maximize Power Harvesting from PV System under Partial and Complex Partial Shading. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Chauhan, Y.K.; Pandey, A.S.; Srivastava, A.K.; Kumar, V.; Alsaif, F.; Elavarasan, R.M.; Islam, M.R.; Kannadasan, R.; Alsharif, M.H. A Novel Hybrid MPPT Approach for Solar PV Systems Using Particle-Swarm-Optimization-Trained Machine Learning and Flying Squirrel Search Optimization. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataifa, H. Modeling and Control of a Dual-Mode Grid-Integrated Renewable Energy System. Master’s Thesis, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Cape Town, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, J.M.; Alfonso-Corcuera, D.; Roibás-Millán, E.; Cubas, J.; Cubero-Estalrrich, J.; Gonzalez-Estrada, A.; Jado-Puente, R.; Sanabria-Pinzón, M.; Pindado, S. Analytical Modeling of Current-Voltage Photovoltaic Performance: An Easy Approach to Solar Panel Behavior. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, M. Design and Implementation of an Effective Electrical Power System for Nano-Satellite. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2014, 5, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Guter, W.; Dunzer, F.; Ebel, L.; Hillerich, K.; Köstler, W.; Kubera, T.; Meusel, M.; Postels, B.; Wächter, C. Space Solar Cells—3G30 and Next Generation Radiation Hard Products. E3S Web Conf. 2017, 16, 03005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KDwaza, S. Krishnamurthy, “Application Perturb and Observe Maximum Power Point Tracking Technique for CubeSat Power Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 32nd Southern African Universities Power Engineering Conference (SAUPEC), Stellenbosch, South Africa, 24–25 January 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarakonda, A.; Karuppiah, N.; Selvaraj, T.; Balachandran, P.; Shanmugasundaram, R.; Senjyu, T. A Comparative Analysis of Maximum Power Point Techniques for Solar Photovoltaic Systems. Energies 2022, 15, 8776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; He, Y.; Li, S.; Hussain, S.; Lu, J.; You, G.; Guerrero, J.M. Adaptive two-step power prediction and improved perturbation method for accelerated MPPT with reduced oscillations in photovoltaic systems. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 5328–5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).