Abstract

Renewable energy sources provide environmental and economic benefits by replacing conventional energy sources. In Korea, photovoltaic (PV) systems are increasingly deployed in apartment complexes and residential buildings. In self-consumption PV systems, surplus generation exceeding local demand often leads to a reverse power flow. This phenomenon becomes more frequent in microgrid environments where multiple distributed energy resources are interconnected. Accordingly, inverter control strategies based on generation forecasting have emerged as critical challenges. In this paper, we propose an on-device artificial intelligence model for inverter control that integrates net power forecasting with time-series neural networks. Two novel forecasting methods were proposed and introduced: Prediction-to-Prediction (P–P) and Net-Power Prediction (N–P). Various neural network models were trained and evaluated using multiple performance metrics. A novel threshold adjustment mechanism based on the mean absolute error was designed for inverter control. The control scenarios were analyzed by comparing the actual power losses with the forecast-based power losses, and the energy savings were quantified by adjusting the correction factor. The proposed forecasting methods achieved a reduction of approximately 40–70% in energy losses compared with the actual loss levels. The threshold adjustment strategy enhances flexibility in balancing the number of on/off switching events and the power loss, contributing to improved energy efficiency and system stability.

1. Introduction

Global energy demand continues to increase and is expected to rise steadily until 2030 [1]. Currently, most electricity is generated from non-renewable fossil fuels such as oil, coal, and natural gas, which are recognized as primary contributors to greenhouse gas emissions and global warming [2]. By contrast, renewable energy sources can replace conventional fuels while offering both environmental protection and economic benefits. Accordingly, the expansion of renewable energy has emerged as a critical requirement for achieving environmental sustainability and economic growth [3,4]. Among these technologies, this study focuses on photovoltaic (PV) systems.

In Korea, the deployment of PV systems in apartment complexes and multi-residential buildings has been steadily increasing. With this expansion, the assignment or delegation of certified electrical safety managers has become mandatory, further emphasizing the importance of safety management [5]. However, the proliferation of PV systems has introduced bidirectional power flow within distribution networks. When generation exceeds the local demand, the surplus flows back into the grid, causing a reverse flow problem. This phenomenon becomes more frequent with the increasing penetration of distributed generation resources such as PV power. The reverse flow is detected by reverse power relays, and if the threshold is exceeded, circuit breakers trip to disconnect the inverters from the grid. Consequently, such disconnections restrict the output even under favorable generation conditions, resulting in immediate power loss. Furthermore, following a breaker trip, electrical safety managers or trained personnel must conduct on-site inspections and perform manual recovery, causing inevitable delays and additional long-term losses. These issues are particularly critical in unmanned facilities or sites without resident inspection staff [6,7].

According to domestic regulations on electrical safety management, the responsibilities of safety managers include equipment inspection, operational control, and supervisory duties [8]. However, the current framework depends heavily on periodic manual inspections and on-site interventions, which are both labor- and time-intensive [9]. In microgrid environments, in which distributed generation is widely deployed, the burden on safety managers increases, and management efficiency declines [10]. To overcome these limitations, a transition from reactive inspection-based practices to proactive control frameworks that incorporate both PV power generation and power consumption forecasting is required. By adjusting the inverter output in advance according to both the forecasted generation and consumption, disturbances from surplus power can be mitigated, reverse power flow can be prevented, and additional economic benefits can be achieved, such as reduced operational costs, extended equipment lifetimes, and more efficient power utilization. Moreover, minimizing repetitive manual inspections and control interventions can substantially lower the labor requirements for electrical safety management.

Several studies on microgrids have examined the integration of forecasting into energy management and control. For example, one study proposed a forecast-based energy management system for a university microgrid, combining LSTM-based PV and load forecasts with an optimization-based dispatch. Their results demonstrated that predictive control can improve battery utilization, reduce emissions, and lower operational costs, underscoring the benefits of coupled forecasting with real-time microgrid operation [11].

In addition to these forecasting-oriented approaches, optimization-based strategies have been explored. A recent investigation of industrial steam-cracking microgrids introduced a multi-objective optimization framework that balances the economic and environmental objectives under uncertainty. While this line of research highlights the role of optimization in industrial energy systems, the present study differs in scope and methodology. Specifically, our work focuses on PV-integrated microgrids in the building sector, where reverse power flow poses operational challenges. By introducing novel Prediction-to-Prediction (P–P) and Net-Power Prediction (N–P) forecasting methods, we emphasize time-series prediction and inverter control as means to minimize unnecessary generation losses, thereby complementing optimization-oriented approaches from a forecasting–control perspective [12].

Although optimization frameworks have been actively explored in the context of industrial microgrids, research on PV systems and load forecasting has largely focused on single-target prediction tasks.

For example, a hybrid Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) with multi-layer Bidirectional LSTM (Bi-LSTM) has been applied to short-term residential electricity consumption forecasting, showing that combining spatial feature extraction with bidirectional temporal modeling can substantially improve prediction accuracy compared to conventional unidirectional models [13].

Another study proposed a hybrid forecasting framework for PV power generation that integrates Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCNs), Efficient Channel Attention (ECA), and stacked BiLSTM and BiGRU layers. This approach illustrates the growing interest in combining convolutional, recurrent, and attention-based architectures to enhance the performance of solar power prediction methods [14].

While these studies highlight the progress of advanced neural network models in improving single-target forecasting, integrated approaches that jointly consider both PV generation and electricity consumption remain scarce. To address this gap, more sophisticated hybrid and attention-based deep-learning architectures have recently been explored. For instance, a dual-stream forecasting framework that combines dilated causal convolution and Bi-LSTM with a trapezoid attention module was introduced, enabling the simultaneous modeling of spatial, temporal, and spatiotemporal dependencies in power generation and consumption data [15].

Previous hybrid model approaches primarily sought to improve forecasting accuracy by combining multiple neural architectures and focusing on structural fusion rather than redefining the forecasting process itself. In contrast, this study proposes a novel forecasting methodology based on data-level integration, jointly learning generation and consumption patterns within a unified predictive framework. This approach differs from traditional hybridization by emphasizing the intrinsic interdependence between generation and consumption to enhance inverter control and energy efficiency. More effective control strategies that reduce the stress on the grid and minimize generation losses can be designed by jointly using generation and consumption data to forecast net power. The purpose of this study was to develop a model that forecasts the net power state 15 min ahead using both PV generation and power consumption data, and to implement inverter control strategies that minimize unnecessary generation losses [16]. To this end, various time-series neural network models were applied to evaluate the net power forecasting performance and resulting energy savings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Environment

This study focused on a self-consuming PV system installed in a public office building in Yeosu, Jeollanam-do, South Korea. Neighboring PV systems in the region have an average capacity of approximately 96 kW, representing a small- to medium-scale generation environment. The Korea Electric Power Corporation mandates the use of distributed energy resource active voltage management (DER-AVM) inverters for facilities with capacities of 500 kW or higher [17]. The DER-AVM technology enables distributed energy resource inverters to adjust the output power and power factor actively when the grid voltage increases, thereby maintaining voltage quality and stability in distribution networks. The DER-AVM-integrated inverters support output control, reactive power control, and voltage regulation functions, making them essential for grid stability in large-scale distributed generation systems. In contrast, the target system in this study is a small-scale, self-consuming PV installation that employs conventional inverters. Consequently, preventing reverse power flow during grid interconnection requires the additional use of a reverse power relay and a magnetic contactor (MC), which impose operational constraints [18]. These considerations highlight the practical significance of our proposed control method.

We used inverter-level PV generation data and total building power consumption data from the target system for the analysis. The training dataset consisted of generation and consumption measurements collected from January to December 2019, whereas the test dataset included data recorded during the same period in 2020 [19,20].

It is important to note that the PV generation dataset used in this study was normalized to the average output of a single inverter unit, rather than the total aggregated system output. Accordingly, the reported energy savings should be interpreted as the per-inverter average values. These results can be scaled proportionally to the number and capacity of the inverters in operation for system-level evaluation. This approach was adopted to facilitate model generalization across systems of different sizes and enable scalability of the proposed method.

A detailed description of the system configuration is provided in the following section.

2.2. System Configuration

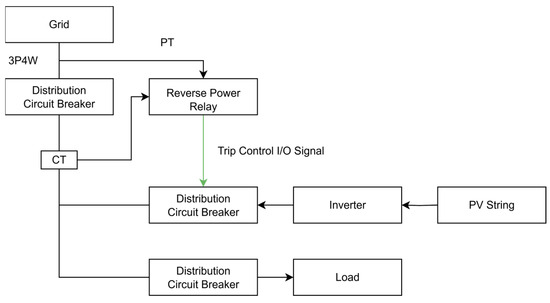

Grid-connected PV systems can be classified into three types. The first is the general self-consumption PV system (Figure 1) that does not employ a DER-AVM-integrated inverter.

Figure 1.

General self-consumption PV system architecture.

In this configuration, a reverse power relay is installed between the grid and the inverter to issue a trip signal when reverse power flow occurs. Because of its simple architecture, this approach has been primarily adopted in small-scale facilities. However, once the relay trips, the on-site personnel must manually restore the system, resulting in generation losses and operational inefficiencies. A current transformer (CT) and a potential transformer (PT) were used for current and voltage measurements, respectively, providing the necessary input signals for relay operation and system monitoring.

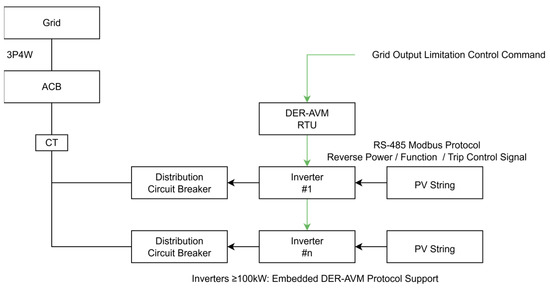

The second type is the DER-AVM-linked inverter system (Figure 2) that is typically used in facilities with capacities exceeding 500 kW.

Figure 2.

DER-AVM linked inverter system architecture.

In this case, the DER-AVM remote terminal unit (RTU) received the grid output limitation control commands and transmitted the control signals to the inverter using the RS-485 Modbus protocol. Consequently, reverse power flow protection and output limitations are automated, making this configuration suitable for high-capacity installations.

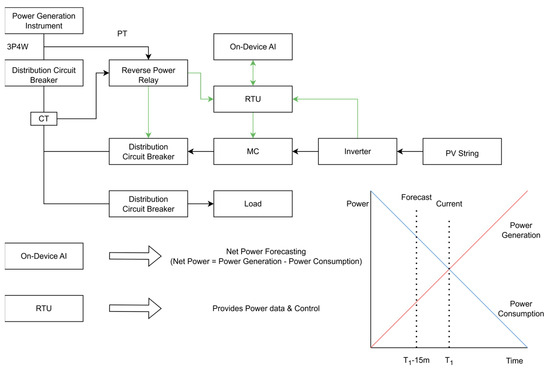

The third configuration is the proposed on-device AI-based time-series neural network model (Figure 3), which was designed to overcome the limitations of conventional systems.

Figure 3.

Proposed on-device AI-based PV system architecture.

In this architecture, the on-device AI model forecasts the PV generation and power consumption in real time and predicts the likelihood of reverse power flow in advance. The forecasting results are transmitted via the RTU to the MC and the inverter, enabling proactive control before the reverse power relay is triggered. The RTU concurrently acquires generation and consumption data while transmitting control commands to field devices. This approach minimizes unnecessary generation losses and enables field-oriented real-time control automation, thereby enhancing both the operational efficiency and system reliability. Because effective training and inference of the forecasting model require preprocessed input, a detailed description of the data characteristics and preprocessing procedures is provided in the following section.

2.3. Data Characteristics and Preprocessing

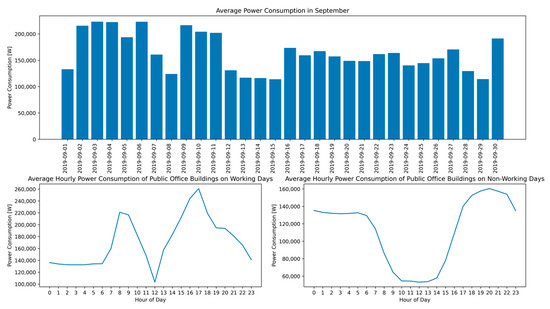

Energy generation and consumption exhibit distinct patterns depending on the day of the week, time of the day, and season [21]. Figure 4 shows the average daily power consumption for September 2019 (top) and the hourly average consumption for the entire year (bottom), separated into working days (left) and non-working days (weekends and public holidays, right).

Figure 4.

Time-series characteristics of power consumption in public office buildings.

During September, a lower average consumption was observed on non-working days, such as 12–15 September. On working days, a double-peak pattern emerged, with the demand peaking at 07:00–09:00 and 16:00–18:00. In contrast, on non-working days, a U-shaped pattern was observed, characterized by a midday trough, followed by an evening peak [22]. All values were derived from 15 min interval measurements. These patterns illustrate the concentrated demand driven by facility operation schedules on working days and reduced demand characterized by continuous essential loads on non-working days. However, such patterns cannot be generalized to all buildings, because they are influenced by the operational characteristics of the studied public office. Therefore, further investigations that consider building size, purpose, and operational policies are necessary.

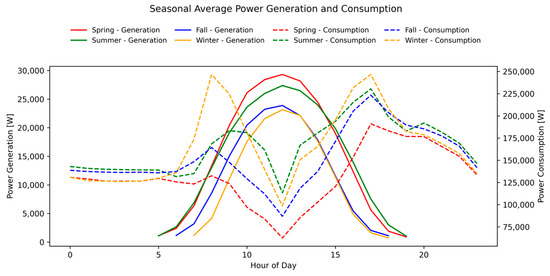

Figure 5 presents the seasonal daily averages of the PV generation and power consumption.

Figure 5.

Seasonal patterns of power generation and consumption.

The PV output reached its maximum in spring and was relatively low in winter. Conversely, consumption exhibits greater seasonal variability, peaking in winter and reaching its lowest levels in spring. A pronounced double-peak pattern is observed in the morning and evening.

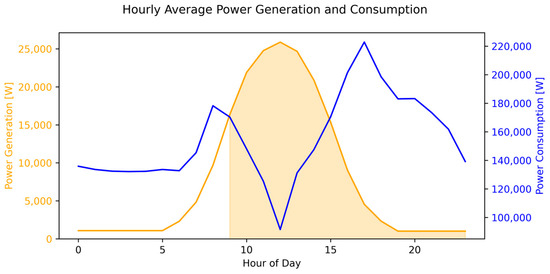

Figure 6 compares the average hourly PV generation and power consumption in 2019.

Figure 6.

Average hourly power generation and consumption.

The PV generation (yellow curve, left y-axis) and power consumption (blue curve, right y-axis) are plotted together to highlight their contrasting temporal patterns. The PV generation followed a typical diurnal pattern, increasing from approximately 05:00, peaking near noon, and gradually declining thereafter. In contrast, power consumption exhibited a double-peak structure during the morning and evening surges. The shaded regions in the figure indicate periods during which the reverse power flow protection disconnects the grid in the absence of control, leading to generation curtailment across the entire shaded interval. In this study, the proposed control strategy limits the inverter output during periods when PV generation exceeds consumption and subsequently restores it when consumption surpasses generation. This approach reduces the curtailment exclusively to surplus generation intervals, thereby minimizing generation losses.

For visualization, a dual y-axis was employed to display both variables within the same plot at different axis scales. Accordingly, the relative positions of the curves indicate temporal variations and correlations rather than absolute magnitudes. The training data used in this study were collected under conditions where consumption significantly exceeded generation. However, consumption and generation magnitudes may be more comparable in practical applications, making the recognition of characteristic patterns more critical than direct magnitude comparisons. Therefore, the primary purpose of this visualization is not to compare absolute values, but to capture characteristic patterns for control logic design.

The PV generation data were recorded at 15 min intervals in accordance with the Renewable Energy Standard Protocol Guidelines of the Korea Energy Agency. This guideline specifies a 15 min sampling interval for renewable energy installations, and most domestic facilities adhere to this standard. Accordingly, this study adopts 15 min intervals as the basic unit for training and forecasting [23].

The input variables include date and time information, enabling the model to learn temporal patterns effectively [24]. Although the PV output is influenced by factors such as solar irradiance, cloud cover, and temperature, the output itself represents an integrated result of these factors. Therefore, additional meteorological data were not incorporated to avoid redundancy, maintain model simplicity, and enhance the generalization performance [25,26].

While ongoing research on ensemble and hybrid forecasting strategies has focused on improving predictive accuracy through model-level integration, enhancing efficiency, reliability, and demand management in smart grid operations, this study takes a different approach by treating the net power itself as the forecasting target [27]. Rather than focusing solely on accuracy improvements, this study underscores both forecasting performance and practical applicability, with particular attention paid to inverter control and energy savings in PV-integrated microgrids.

In this study, two new forecasting methods were defined and proposed. The definitions, principles of data alignment, and model design details are presented in the following section.

2.4. Time-Series Forecasting Model Design

Four time-series forecasting models—long short-term memory (LSTM), bidirectional LSTM (Bi-LSTM), convolutional neural network LSTM (CNN-LSTM), and gated recurrent unit (GRU)—are compared for power forecasting tasks. All models were designed to predict the target value 15 min ahead using the previous 24 time steps (15 min intervals, corresponding to a 6 h input window) as input. Both the batch size and number of hidden units were fixed at 32, with the hyperbolic tangent (tanh) activation function applied following the practices reported in PV forecasting studies [28,29].

All features were normalized to the range [0, 1] using min–max scaling. The scaling parameters were computed from the 2019 training data only, and the same parameters were applied to the 2020 test data to ensure consistent scaling and avoid data leakage. This normalization not only ensures numerical consistency across datasets but also improves model stability by preventing features with large numerical ranges, such as power measurements in watts, from dominating the training process. By scaling all the variables to a comparable range, the optimization landscape becomes smoother, leading to faster and more stable convergence. Furthermore, because inverse normalization was applied after prediction, the absolute power values were fully restored, ensuring that the control thresholds in their original physical units (W) remained valid and interpretable.

The Bi-LSTM employs LSTM cells in a bidirectional structure to capture past and future contextual information. The CNN-LSTM integrates a one-dimensional convolutional layer (Conv1D with 64 filters, kernel size of 3, and pooling size of 2) to extract local features before passing them to the LSTM.

The runtime evaluation was conducted in a Google Colab environment equipped with an NVIDIA T4 GPU. Each forecasting model contained approximately 4897 parameters (~0.02 MB in float32). The measured resident set size (RSS) for the runtime process was 1.2–1.3 GB. Average inference latency was ~60 ms per step (batch size = 1) and 1.0–1.9 s for full-batch runs (17k–34k samples). End-to-end net power forecasting, including PV generation and consumption prediction with inverse normalization, required approximately 118 ms per step. In practical deployment, the proposed forecasting models are lightweight and operate on small-scale input data because both PV generation and consumption measurements occupy minimal memory and bandwidth. Consequently, the runtime and memory requirements remain within the capacity of typical embedded AI hardware, demonstrating that on-device execution is feasible without imposing a significant computational burden.

The architectures and training hyperparameters of all models are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Architectures and training hyperparameters of the models.

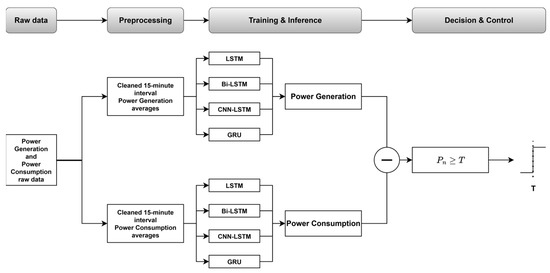

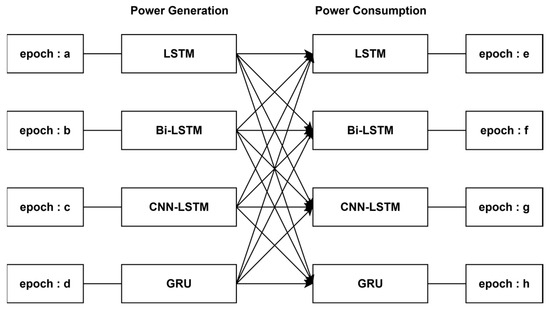

Furthermore, this study defines two new methods for forecasting the net power. The first method, called the Prediction-to-Prediction (P–P) forecasting method, independently trains and forecasts PV generation and power consumption as separate 15 min time series and then derives the net power by subtracting the two forecasts at the same time step. This method is proposed in this study, and its workflow is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Prediction-to-Prediction (P–P) forecasting method workflow.

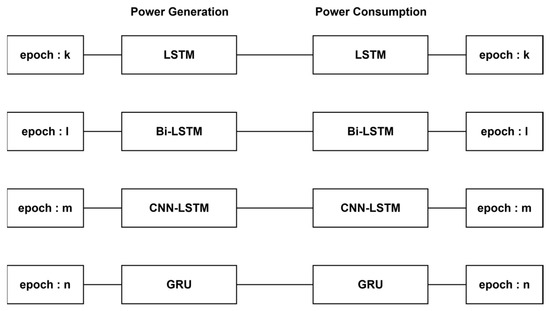

Although the P–P forecasting method is structurally prone to error accumulation due to its reliance on two independent forecasts, it has the advantage of allowing separate analysis of PV generation and power consumption trends. The P–P forecasting method was implemented in two configurations. First, the Same Epoch, Same Model (SESM) configuration uses the same forecasting model trained with the same epoch setting for both the PV generation and power consumption, and the net power is obtained by subtracting the paired forecasts. Figure 8 shows the proposed baseline configuration.

Figure 8.

P–P baseline (Same Epoch, Same Model).

Second, the combined configuration selects the best-performing epoch from each independently trained model and pairs the epochs to compute net power. In this case, two independent models were combined into cross-matched pairs, as illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

P–P combined configuration.

This method reduces the effect of error accumulation compared with the SESM baseline by leveraging the best-trained models for each variable and is expected to provide improved forecasting accuracy. In this paper, combined configurations are denoted as “model/model.”

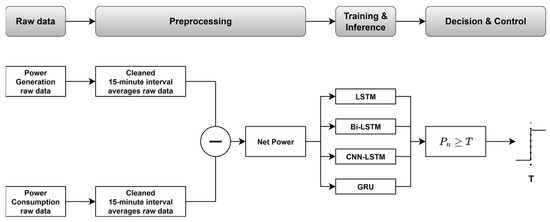

The second method is the Net-Power Prediction (N–P) forecasting method, which is newly defined in this study. In this method, timestamps containing both PV generation and consumption measurements are aligned into a complete time series, and the net power, obtained by subtracting the consumption from the generation, is used directly as the target variable for training and forecasting. The workflow of the direct forecasting method is illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Net-Power Prediction (N–P) forecasting method workflow.

Although the N–P forecasting method integrates both generation and consumption characteristics within a single model, which may limit interpretability, it offers the advantages of model simplicity and a reduced risk of error accumulation. Because P–P and N–P differ in terms of their data alignment requirements and error accumulation, their relative performances cannot be predetermined and require experimental evaluation. Therefore, this study applied dedicated data alignment and preprocessing strategies to each forecasting method to provide a methodological basis for comparison. Although the comparison does not represent a perfectly controlled data experiment, it seeks to evaluate the applicability and practical utility of alternative forecasting methods that can be selected or combined based on data consistency and field constraints. In addition, this study quantitatively evaluated the forecasting performance of each model under both methods and examined the resulting effects on energy loss reduction when integrated into the inverter control logic.

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. Loss Function and Metric Analysis

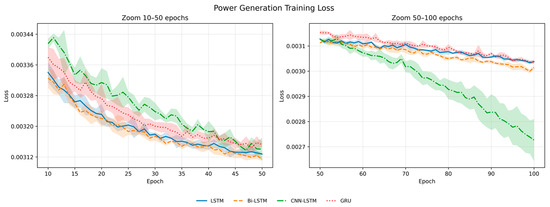

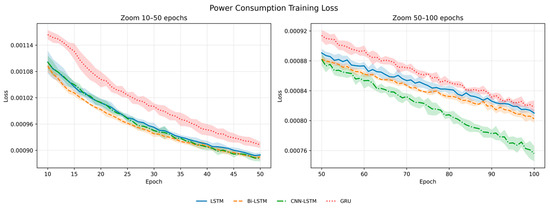

To evaluate the learning stability and convergence behavior of the forecasting models, the training loss curves were analyzed for each task—power generation, power consumption, and net power prediction, as shown in Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13.

Figure 11.

Power generation training loss.

Figure 12.

Power consumption training loss.

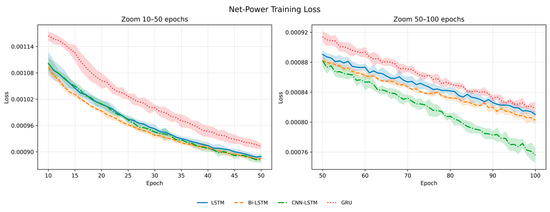

Figure 13.

Net-power training loss (N–P method).

During the initial training phase, all models exhibited a sharp reduction in loss within the first few epochs, followed by gradual stabilization.

In each figure, the solid line represents the mean training loss obtained from multiple runs, which served as the primary basis for performance comparisons among models.

The shaded region indicates the standard deviation (±1σ), reflecting the variability of loss values across runs and thus representing the training stability of each model.

Accordingly, models exhibiting lower mean losses (solid lines) and narrower shaded regions can be interpreted as achieving both higher accuracy and more stable convergence.

In the following figures, the analysis primarily focuses on the solid lines, which represent the mean training losses for each model, whereas the shaded regions are considered supplementary indicators of training stability.

Figure 11 shows the training loss curves for the power generation forecasting.

In the case of power generation forecasting, the training losses of the LSTM and GRU models intersected frequently throughout the early to mid-training phases (up to approximately 80 epochs), indicating that their relative performances were not clearly distinguishable. After approximately 80 epochs, Bi-LSTM began to show noticeably lower loss values than LSTM and GRU, demonstrating improved learning efficiency in the later stage. The CNN-LSTM model achieved the best overall performance, exhibiting the lowest loss values from approximately 60 epochs onward and showing a smoothly decreasing and stable convergence pattern.

Figure 12 shows the training loss curves for the power consumption forecasting.

In the case of power consumption forecasting, the GRU model showed the highest loss values within the 10–50 epoch range, indicating a relatively poor learning efficiency in the early training stage. During the same interval, the LSTM, Bi-LSTM, and CNN-LSTM models exhibited frequent intersections in their loss curves, making their relative performances difficult to distinguish. From approximately 60 epochs onward, the loss values of all models were clearly separated, revealing a consistent performance order of CNN-LSTM, Bi-LSTM, LSTM, and GRU from best to worst.

Figure 13 shows the training loss curves for the Net-Power Prediction (N–P) approach.

In the case of net-power prediction, in which the net power (the difference between power generation and consumption) was directly used as the training input, distinct convergence patterns were observed among the models. The CNN-LSTM model exhibited the best performance, showing the lowest loss values from approximately 60 epochs onward, and a steadily decreasing and smoothly converging trend. The loss curves of the GRU and LSTM models intersected frequently throughout the training period, making it difficult to distinguish their relative performances. From approximately 80 epochs, the Bi-LSTM model achieved noticeably lower losses than both the GRU and LSTM, indicating an improved learning efficiency in the later training phase. As shown in Figure 12, within the 10–100 epoch range, clear differences among the models were observed: CNN-LSTM consistently achieved the lowest loss, followed by Bi-LSTM, whereas LSTM and GRU frequently intersected, making their relative ordering less definitive. Most models effectively reduced the training loss and exhibited stable convergence on the training data. However, these results only reflect the fitting performance on the training dataset and do not guarantee generalization. Therefore, the true predictive performance of each model must be evaluated based on accuracy metrics using the test set.

The performances of the forecasting models were quantitatively evaluated using the mean absolute error (MAE), normalized root mean square error (nRMSE), and coefficient of determination (R2). The MAE represents the average absolute difference between the predicted and actual values, with smaller values indicating a lower prediction error. The nRMSE was calculated by dividing the RMSE by the mean of the actual values, allowing the relative error levels to be compared independently of the data scale, thereby enabling a fair comparison across datasets or models. RMSE emphasizes larger errors by squaring the deviations before averaging, with smaller values indicating higher predictive accuracy. R2 measures the proportion of variance in the actual data explained by the model. Values closer to 1 indicate stronger explanatory power, whereas 0 indicates no better performance than simply predicting the mean. The evaluation metrics are defined in Equations (1)–(4) [30,31].

The LSTM, Bi-LSTM, CNN-LSTM, and GRU were trained with epoch counts of 10, 50, 100, 200, 500, and 1000 to evaluate the forecasting performance for PV generation and power consumption. Table 2 summarizes the results for the best-performing epoch of each model, with the performance primarily determined by nRMSE and R2.

Table 2.

Forecasting performance for power generation and consumption.

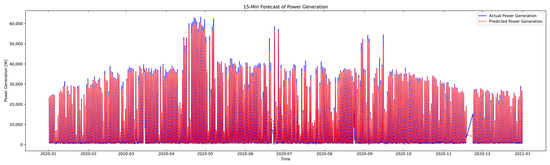

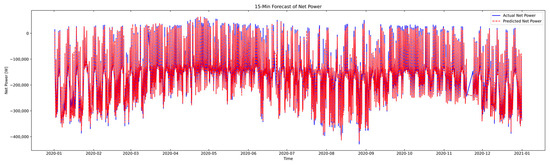

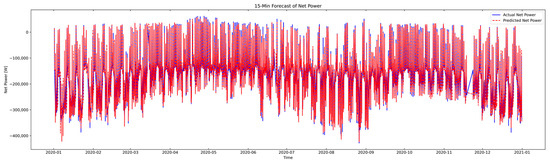

For consistency in reporting, the nRMSE and R2 values were rounded to four decimal places, and the MAE values were rounded to two decimal places. Figure 14 presents the test results of the GRU model, which achieved the best performance for PV power generation forecasting according to Table 2.

Figure 14.

Comparison of actual and predicted power generation (GRU).

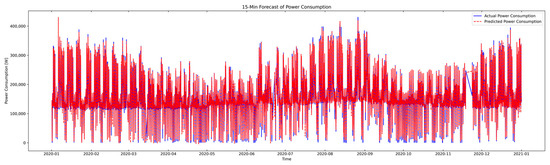

Figure 15 shows the test results of the LSTM model, which achieved the best performance for power consumption forecasting, according to Table 2.

Figure 15.

Comparison of actual and predicted power consumption (LSTM).

Table 3 lists the best-performing cases for each model using the SESM configuration of the P–P forecasting method.

Table 3.

Forecasting performance of the SESM method.

As indicated in Table 3, the LSTM model achieved the most favorable performance among the SESM configurations, with the lowest MAE and nRMSE values and the highest R2 value. Figure 16 shows the corresponding prediction trace, illustrating that the LSTM model closely followed the actual net power trajectory with minimal deviations across all evaluation metrics.

Figure 16.

Net power prediction using P–P forecasting method (LSTM, SESM).

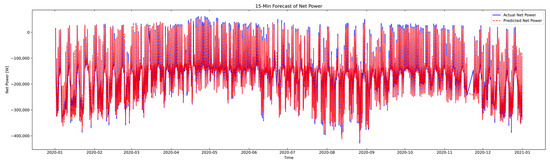

Table 4 compares the forecasting performances of the SESM, combined, and N–P forecasting methods.

Table 4.

Net power forecasting performance.

The combined configurations were constructed by pairing the four base models (LSTM, Bi-LSTM, CNN-LSTM, and GRU) presented in Table 2, which summarizes the best-performing case for each model. In total, 16 model combinations were evaluated under identical epoch settings to assess whether joint architectures could further improve the forecasting accuracy. The N–P forecasting method was trained using the same epoch configurations (10, 50, 100, 200, 500, and 1000), and the same performance metrics were applied.

According to Table 4, the GRU/LSTM combination using the P–P forecasting method produced the lowest MAE, indicating the best performance in terms of absolute error, whereas the LSTM/LSTM configuration delivered the most stable results in terms of the nRMSE. For LSTM, LSTM/LSTM, CNN-LSTM/LSTM, and GRU/LSTM, R2 was 0.9526, representing the highest value among all the models.

Within the P–P forecasting framework, the performance differences between the SESM and combined model configurations are inconclusive because the results may vary slightly depending on the random initialization of the model weights. These variations were minor and fell within a negligible range and did not affect the overall interpretation of the results. Therefore, the focus of this study lies not in the absolute comparison of model accuracy, but in the methodological perspective of the learning approach itself.

Figure 17 illustrates the forecasting trace of the LSTM/LSTM combined model, which achieved the best overall performance among all the combinations.

Figure 17.

P–P combined LSTM/LSTM (epochs: 10/100).

For the N–P forecasting method, Table 4 indicates that the LSTM model trained for 100 epochs was the best-performing configuration. Figure 18 presents the forecasting results, which show strong performance with a low MAE, reduced nRMSE, and high R2 values; however, the overall accuracy remained lower than that of the P–P forecasting method.

Figure 18.

Net-power prediction using N–P forecasting method (LSTM, epochs: 100).

The N–P forecasting method generally shows less favorable performance than the P–P forecasting method. This outcome reflects the differences in dataset construction between the two methods; thus, no single method can be considered superior.

Overall, the results confirmed that the models effectively captured the variance and temporal patterns in the data. The configuration using the SESM and the combined model, which was trained on the same dataset, generally achieved superior performance across the evaluation metrics, suggesting its potential as a stronger alternative. In contrast, although the P–P and N–P forecasting methods relied on different dataset constructions, both achieved stable accuracy levels, confirming that multiple forecasting pathways can be effectively applied to net power prediction.

3.2. Control Performance Evaluation

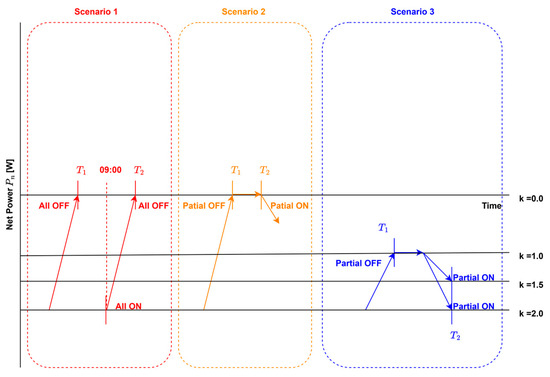

In this study, three control scenarios were established to compare the actual grid operation environment with forecasting-based control.

The first scenario represents an existing system in operation. In practice, when the reverse power relay is triggered and the inverter switches from ON to OFF, automatic recovery does not occur, and the shutdown state persists until 9:00 the following day. Consequently, all generations during this period were considered actual power losses.

The second scenario corresponded to a forecasting-based control method with a single threshold. In this case, the inverter control was performed using the output of the prediction model; however, no threshold adjustment was applied, and the switching conditions for the ON–OFF and OFF–ON transitions were set symmetrically. Consequently, the control can become overly sensitive to prediction errors, potentially leading to excessive switching operations. All curtailed generation in this scenario was regarded as forecasting-based power losses. The control rules are defined in Equations (5)–(8).

where denotes the net power, which is defined as the difference between the PV generation and load consumption. The corrected threshold power, is obtained by subtracting the error-compensation offset from the base threshold . In this study, was fixed at zero because zero net power represents the operating point at which the reverse power flow begins. The offset is proportional to the MAE of the forecasting model, whereas the correction factor k serves as a scalar parameter that adjusts the offset magnitude. A larger k widens the switching margin, mitigating unnecessary responses to prediction errors and improving the system stability, whereas a smaller k increases the sensitivity at the cost of more frequent switching and reduced stability.

The parameters and represent the ON and OFF switching thresholds, respectively. In the single-threshold case (k = 0), these thresholds coincided with the base threshold, as expressed in Equation (9).

The third scenario involved a forecasting-based control method with a threshold adjustment. An offset-based threshold adjustment was introduced to account for prediction errors in the control stage and ensure system stability. The offset was calculated using the MAE, and the following asymmetric switching conditions were applied: ON–OFF and OFF–ON transitions, followed by different thresholds. Curtailed generation in this threshold-adjusted configuration is also regarded as a forecasting-based power loss. These conditions are defined in Equations (10) and (11).

where and denote the offset correction terms for the OFF-ON and ON–OFF switching conditions, respectively, calculated based on the MAE. The MAE used for the threshold adjustment was computed during the test evaluation phase rather than during the training process. This value represents the average absolute prediction error of the model and was employed as the correction factor k to adaptively adjust the inverter on/off threshold according to the expected forecasting uncertainty.

The asymmetric correction factors were also designed to introduce a wider switching margin, thereby reducing the frequency of inverter on/off transitions caused by small forecasting deviations. Frequent power switching can accelerate mechanical wear and shorten the operational lifespans of relay and inverter components. By widening the control gap under surplus conditions, the proposed asymmetric configuration mitigates unnecessary switching events, enhances operational stability, and improves equipment longevity.

Thus, the three scenarios can be summarized as follows: the first corresponds to the actual grid operation, in which curtailed generation is regarded as the actual power loss; the second applies single-threshold control with k = 0.0; and the third introduces threshold-adjusted control, in which asymmetric correction factors are applied (k = 1.0 for ON–OFF transitions and larger values such as 1.5 or 2.0, for OFF–ON transitions). In both forecasting-based control scenarios (scenarios 2 and 3), curtailed generation was regarded as a forecasting-based power loss. The conceptual inverter on/off switching rules for each scenario are shown in Figure 19.

Figure 19.

Inverter ON/OFF switching in three control scenarios.

The confusion matrix results for the best-performing models for each k-value are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Confusion-matrix results of best-performing models by k value (F1-score criterion).

The control performance was evaluated using a confusion matrix, from which the accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score were computed. Accuracy measures the proportion of correctly classified samples, precision represents the ratio of correctly identified control-required cases among all predicted control-required cases, and recall indicates the proportion of true control-required events that are correctly detected. The F1-score, as the harmonic mean of precision and recall, provides a balanced evaluation of both. In this context, true positives (TP) refer to cases in which control is correctly executed when required, true negatives (TN) indicate correct identification of non-control cases, false positives (FP) correspond to unnecessary control operations, and false negatives (FN) indicate failure to execute control when required. As precision and recall may conflict in the control context, the F1-score was adopted as the primary criterion for selecting the optimal model. These metrics are defined in Equations (12)–(15) [32,33].

Table 6 summarizes the models that achieved the best performance in terms of the F1-score across different k values for both the P–P and N–P forecasting methods.

Table 6.

Best-performing models by k value (F1-score criterion).

In Scenario 3, because the ON–OFF switching condition was fixed at k = 1.0, the k values reported in the table refer to the correction factors applied to the OFF–ON transition.

In the P–P forecasting method, the GRU/CNN-LSTM, CNN-LSTM/CNN-LSTM, and GRU/LSTM models achieved the best performance when k = 0.0; the LSTM/Bi-LSTM and Bi-LSTM models performed the best when k = 1.5; and the LSTM/GRU model performed the best when k = 2.0.

In the N–P forecasting method, Bi-LSTM achieved the highest F1-score at k = 0.0, whereas the CNN-LSTM model performed the best at k = 1.5 and 2.0.

Although the F1-scores tended to decrease with larger k values, the overall performance remained strong. These results demonstrate that both methods are applicable to control problems based on net power forecasting. In practical settings, computational complexity, real-time requirements, and application objectives should be carefully considered when selecting the appropriate methods and models.

In this study, power losses were categorized into two types depending on the control scenario. In Scenario 1 (actual grid operation), curtailed generation was defined as . In contrast, in Scenarios 2 and 3 (forecasting-based control), curtailed generation is defined as . The corresponding energy savings are defined by Equations (16) and (17):

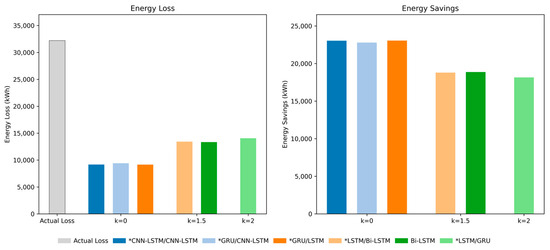

Table 7 summarizes the energy savings of both the P–P and N–P forecasting methods for different k values.

Table 7.

Energy savings.

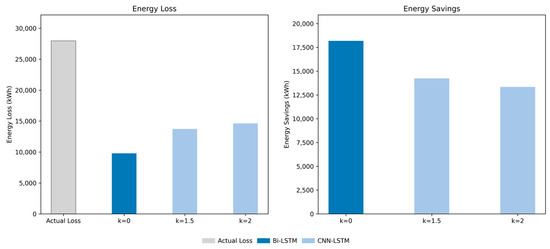

Figure 20.

Energy loss and energy savings (P–P forecasting method). * indicates a combined model.

Figure 21.

Energy loss and energy savings (N–P forecasting method).

The results are based on the optimal models selected according to the F1-score in Table 6. The actual power losses were approximately 32,203 kWh using the P–P forecasting method and 27,964 kWh using the N–P forecasting method. Among the forecasting-based systems, the P–P method achieved a maximum saving of 23,051 kWh at k = 0.0. At k = 1.5, the savings were 18,785 and 18,865 kWh, respectively, whereas savings decreased to 18,149 kWh at k = 2.0. For the N–P forecasting method, the maximum savings were 18,183 kWh at k = 0.0, with savings of 14,242 and 13,345 kWh at k = 1.5 and 2.0, respectively.

Here, k denotes a correction factor that scales the offset relative to the MAE of the model. An increase in k broadens the switching margin, thereby reducing sensitivity while enhancing operational stability. Overall, the proposed forecasting-based control methods reduced the energy losses by approximately 40–70% compared with the actual operation scenario. As k increases, the energy-saving effect diminishes owing to the reduced control sensitivity and a lower number of on/off switching events.

Although this reduction may lead to short-term efficiency loss, it can provide long-term benefits by mitigating mechanical wear from frequent switching and minimizing unnecessary control actions caused by prediction errors, thereby enhancing system stability. In addition, output fluctuation mitigation can help prevent power-quality degradation.

The choice of the threshold is closely related to the interests of the grid operators and power producers. Smaller correction factors lead to more sensitive control and larger energy savings but may cause frequent switching, instability, and degraded power quality. Larger correction factors reduce the switching frequency and improve the system stability but can decrease the generation output and profitability. Therefore, the threshold is not merely a control parameter but also a critical variable mediating the relationship between grid stability and economic returns. To achieve an appropriate balance, the optimal value should be determined through technical considerations and stakeholder consensus.

Although the proposed threshold-based control strategy conceptually achieves a balance between grid stability and economic efficiency, its practical implementation involves additional technical challenges.

Several implementation challenges were identified in the development and on-site testing of the proposed forecasting-based control framework.

First, data quality issues were occasionally observed, owing to sensor data loss and irregular recording intervals. Because the measurement devices did not originally collect data at fixed 15 min intervals, a preprocessing stage was required to aggregate the high-resolution measurements into consistent 15 min averages. This procedure helped stabilize the time-series inputs but also introduced a minor aggregation bias that could affect the temporal precision of the training data.

Second, the on-device execution of the trained models on embedded AI boards demonstrated the feasibility of real-time operations.

However, a systematic evaluation to identify the most suitable hardware configuration has not yet been conducted, and further research is required to optimize performance across different embedded platforms.

Future work will focus on balancing the computational complexity, inference latency, and power consumption to achieve efficient on-device implementation in practical microgrid environments.

4. Conclusions

This study addresses the issue of reverse power flow in distributed PV systems by experimentally validating the net power forecasting and energy-saving effects using time-series neural network models. Data on PV generation and building power consumption were collected from a public office building in Yeosu, Korea, and used to develop forecasting models that can predict the net power state 15 min ahead. Inverter control strategies were designed based on these forecasts to minimize unnecessary disconnections and enhance the system stability.

Four representative time-series models (LSTM, Bi-LSTM, CNN-LSTM, and GRU) were compared from a methodological perspective. To forecast net power, two novel forecasting methods were introduced: the P–P forecasting method, which forecasts generation and consumption separately and then computes their difference, and the N–P forecasting method, which learns directly from the pre-computed net power series. Within the P–P forecasting method, two new configurations were defined: the SESM configuration and the combined model, which integrates the best-performing generation and consumption models.

Analysis of the training losses revealed distinct convergence patterns among the models. The CNN-LSTM maintained the lowest loss values from approximately 60 epochs onward, with a smooth and steadily decreasing trend. The loss curves of the GRU and LSTM intersected frequently throughout the training, making their relative performances difficult to distinguish. From approximately 80 epochs, Bi-LSTM achieved noticeably lower losses than both the GRU and LSTM, indicating an improved learning efficiency in the later training phase.

In the performance evaluation, the GRU/LSTM combination using the P–P forecasting method achieved the lowest MAE, whereas the LSTM/LSTM model showed the most stable performance in terms of the nRMSE. For LSTM, LSTM/LSTM, CNN-LSTM/LSTM, and GRU/LSTM, the R2 was 0.9526. Overall, both the P–P and N–P forecasting methods demonstrated strong performance, with the observed differences primarily attributed to dataset variations. These findings indicate that neither method can be generalized as definitively superior, underscoring the methodological diversity and applicability of multiple forecasting strategies.

Three scenarios were designed to evaluate the control performance.

The first scenario represented an actual field operation, in which the reverse power relay tripped the inverter into the OFF state without automatic recovery until the following day at 9:00, leading to all curtailed generation being treated as a loss.

The second scenario corresponded to forecasting-based control with a single threshold (k = 0.0) applied symmetrically for ON–OFF and OFF–ON transitions, which maximized energy savings, but was prone to frequent switching owing to prediction errors.

The third scenario applied forecasting-based control with an offset-based threshold adjustment, in which the MAE was used as an offset and applied asymmetrically to the ON–OFF and OFF–ON transitions, thereby reducing unnecessary switching caused by prediction errors and improving operational stability.

Performance evaluation using confusion-matrix-based metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score) showed that both the P–P and N–P forecasting methods exhibited a common trend: as k increased, the energy savings decreased owing to reduced control sensitivity and fewer on/off switching events. In the energy-saving analysis, the maximum savings were approximately 23,051 kWh for the P–P forecasting method and 18,183 kWh for the N–P forecasting method.

The contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

In contrast to previous research, which focused primarily on forecasting generation or consumption independently, this study defined the net power forecasting problem by jointly incorporating both variables and proposed two new forecasting methods (P–P and N–P).

A comparative evaluation across multiple time-series models and their combinations enabled a more comprehensive analysis, while control performance was validated under three realistic operating scenarios.

This study empirically demonstrates how offset-based threshold adjustment influences the trade-off between energy savings and system stability, highlighting the importance of balancing technical performance with stakeholder interests for system operators and PV owners.

The proposed forecasting and control framework was designed for deployment in on-device AI environments, offering practical potential for real-time forecasting and automated control of future microgrid applications.

Although the proposed approach demonstrated promising performance and practical applicability, several limitations remain to be addressed in future research.

First, although the one-year PV generation dataset inherently reflected seasonal variations, those related to temperature, specific meteorological factors such as cloud cover, wind speed, and solar irradiance, were not explicitly considered. These external variables will be incorporated into future research to further improve model generalization and forecasting accuracy.

Second, future studies should focus on identifying the optimal hardware platform for model deployment with the aim of minimizing development costs while maintaining efficient real-time performance. A systematic evaluation across multiple embedded devices will be performed to identify the optimal trade-off between computational capability and energy efficiency.

Finally, the proposed on-device AI-based PV system architecture presented in Figure 3 will be physically implemented and experimentally validated to assess its performance under real microgrid operating conditions. Although the dataset used in this study was obtained from a single public building in Yeosu, planned on-site implementation will enable further verification of the adaptability of the model across diverse microgrid environments. This validation will provide practical insights into the scalability and reliability of the proposed forecasting and control framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-S.S.; Methodology, C.-H.B., Y.-S.S., C.-Y.P. and S.-H.L.; Validation, C.-H.B., Y.-S.S., C.-Y.P., S.-H.L. and B.-L.C.; Formal analysis, C.-H.B., Y.-S.S., C.-Y.P. and B.-L.C.; Investigation, C.-H.B. and Y.-S.S.; Resources, S.-H.H.; Data curation, C.-H.B., Y.-S.S. and S.-H.H.; Writing—original draft, C.-H.B.; Writing—review and editing, C.-H.B., Y.-S.S., C.-Y.P., S.-H.L. and B.-L.C.; Visualization, C.-H.B. and Y.-S.S.; Supervision, C.-Y.P., S.-H.L. and B.-L.C.; Project administration, C.-H.B., Y.-S.S. and B.-L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Gwangju.Jeonnam Local Energy Cluster Human Resources Development of the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) grant funded by the Korea government Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (No. RS-2021-KP002519). This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the Jeollanamdo RISE center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Jeollanamdo, Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-14-003).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yeoung-Seok Song was employed by R&D Team, JRI Co., Ltd. Author Seok-Hoon Hong was employed by R&D Center, TEF Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Qazi, A.; Hussain, F.; Rahim, N.A.; Hardaker, G.; Alghazzawi, D.; Shaban, K.; Haruna, K. Towards Sustainable Energy: A Systematic Review of Renewable Energy Sources, Technologies, and Public Opinions. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 63837–63851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balobaid, A.; Abd-Elhafiez, W.M.; Nagy, S.M.; Trabay, D.W. Integrating Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Techniques in Assessing Renewable Energy Potential: A Case Study of Egypt. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 103594–103605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, G.D.; Ibrahim, A.; Sahabi, S.; Lailaba, B.B. Renewable Energy: Environmental Impacts and Economic Benefits for Sustainable Development. Int. J. Eng. Res. 2019, 8, IJERTV8IS080224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialasiewicz, J.T. Renewable Energy Systems with Photovoltaic Power Generators: Operation and Modeling. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2008, 55, 2752–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electrical Safety Management Act, Article 22. Available online: https://www.lawnb.com/Info/ContentView?sid=L000013718_22_20220831 (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Hatta, H.; Asari, M.; Kobayashi, H. Study of Energy Management for Decreasing Reverse Power Flow from Photovoltaic Power Systems. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE PES/IAS Conference on Sustainable Alternative Energy (SAE), Valencia, Spain, 28–30 September 2009; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-S.; Cho, G.-J.; Song, J.-S.; Shin, J.-Y.; Kim, D.-H.; Kim, C.-H. Development of Protection Method for Power System Interconnected with Distributed Generation Using Distance Relay. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2018, 13, 2196–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enforcement Rule of the Electrical Safety Management Act, Article 30. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/lsInfoP.do?lsiSeq=230921#0000 (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Park, C.-Y.; Hong, S.-H.; Lim, S.-C.; Song, B.-S.; Park, S.-W.; Huh, J.-H.; Kim, J.-C. Inverter Efficiency Analysis Model Based on Solar Power Estimation Using Solar Radiation. Processes 2020, 8, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Peng, Y.; He, M.; Deng, T.; Wang, G.; Cao, Q.; Li, X.; Yu, J.; Yu, D. Research on Smooth Switching Control Technology between Grid-Connected Operation and Off-Grid Operation of Micro-Grid. In Proceedings of the 2023 Panda Forum on Power and Energy (PandaFPE), Chengdu, China, 27–30 April 2023; pp. 2244–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, F.; Pavón, W.; Minchala, L.I. Forecast-Based Energy Management for Optimal Energy Dispatch in a Microgrid. Energies 2024, 17, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi Naraghi, S.; Karecka, T.; Jiang, Z. Multi-Objective Optimization of Steam Cracking Microgrid for Clean Olefins Production. Syst. Control Trans. 2025, 4, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.U.M.; Ullah, A.; Haq, I.U.; Rho, S.; Baik, S.W. Short-Term Prediction of Residential Power Energy Consumption via CNN and Multi-Layer Bi-Directional LSTM Networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 123369–123380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renold, A.P.; Sinha, N.; Gao, X.-Z. Hybrid Machine Learning Approach for Improved Short-Term PV Power Forecasting Accuracy. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 107374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.A.; Hussain, T.; Ullah, W.; Baik, S.W. A Trapezoid Attention Mechanism for Power Generation and Consumption Forecasting. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 5750–5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, P.; Kopyt, M. Short-Term Forecasts of Energy Generation in a Solar Power Plant Using Various Machine Learning Models, along with Ensemble and Hybrid Methods. Energies 2024, 17, 4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Eo, I. A Study on the Voltage Rise of the Inverter Output Terminal According to the Low Voltage Grid Connection of Solar Power Generation. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2020, 21, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rules on Technical Standards for Electrical Installations, Article 283. Available online: https://www.ulex.co.kr/ (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Qureshi, M.; Arbab, M.A.; Rehman, S.U. Deep Learning-Based Forecasting of Electricity Consumption. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Cacho, A.; Sanchez-Barroso, G.; Gonzalez-Dominguez, J.; Garcia-Sanz-Calcedo, J. Long-Term Power Forecasting of Photovoltaic Plants Using Artificial Neural Networks. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 2855–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-K.; Phan, Q.-T.; Zhong, Y.-J. Overview of Day-Ahead Solar Power Forecasts Based on Weather Classifications and a Case Study in Taiwan. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 60, 1409–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Han, N.; Li, D.; Tian, S. Trend Analysis of Building Power Consumption Based on Prophet Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2020 Asia Energy and Electrical Engineering Symposium (AEEES), Chengdu, China, 29–31 May 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renewable Energy Monitoring System (REMS). Available online: https://rems.energy.or.kr/pub/view/archive (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Li, S.; Huang, H.; Lu, W. A Neural Networks Based Method for Multivariate Time-Series Forecasting. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 63915–63924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.-C.; Huh, J.-H.; Hong, S.-H.; Park, C.-Y.; Kim, J.-C. Solar Power Forecasting Using CNN-LSTM Hybrid Model. Energies 2022, 15, 8233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.-J.; Wu, Y.-K. Short-Term Solar Power Forecasts Considering Various Weather Variables. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Symposium on Computer, Consumer and Control (IS3C), Taichung City, Taiwan, 13–16 November 2020; pp. 432–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakib, M.; Siddiqui, T.; Mustajab, S.; Alotaibi, R.M.; Alshareef, N.M.; Khan, M.Z. An Ensemble Deep Learning Framework for Energy Demand Forecasting Using Genetic Algorithm-Based Feature Selection. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0310465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamberg, L. Photovoltaic System Performance Forecasting Using LSTM Neural Networks. Master’s Thesis, Department of Information Technology, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2021. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1601739&dswid=-5388 (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Luo, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, X. Deep Learning Based Forecasting of Photovoltaic Power Generation by Incorporating Domain Knowledge. Energy 2021, 225, 120240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannah, N.; Gunawan, T.S.; Yusoff, S.H.; Hanifah, M.S.A.; Sapihie, S.N.M. Recent Advances and Future Challenges of Solar Power Generation Forecasting. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 168904–168924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelega, R.; Greu, D.I.; Jecan, E.; Rednic, V.; Zamfirescu, C.; Puschita, E.; Turcu, R.V.F. Prediction of Power Generation of a Photovoltaic Power Plant Based on Neural Networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 20713–20724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouidad, H.I.; Bouhelal, A. Machine Learning-Based Short-Term Solar Power Forecasting: A Comparison between Regression and Classification Approaches Using Extensive Australian Dataset. Sustain. Energy Res. 2024, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbani, J.; Portier, P.-É.; Egyed-Zsigmond, E.; Nurbakova, D. Confusion Matrices: A Unified Theory. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 181372–181419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).