Abstract

This paper analyses the parameterisation of protective relays in industrial power distribution stations, focusing on the quantitative relationship between network load and protection system response time. Laboratory simulations using a dedicated automation cabinet and varying network configurations (six streams at 80 samples/cycle and two to four streams at 256 samples/cycle) revealed a clear correlation: higher network loads lead to longer trip times. Under maximum load (four streams, 256 samples/cycle), response times reached up to 63.75 ms. These delays stemmed from network congestion rather than relay instability. The extended clearing times increased the short-circuit energy (I2t) by approximately 35% on average and over 55% in critical scenarios, requiring upsizing of PVC-insulated conductors from 16 mm2 to 25 mm2 to maintain short-circuit withstand capacity. The findings demonstrate the practical impact of network-induced delays on protection performance, thermal stress, and cable sizing, providing a basis for optimising relay settings and system configuration in modern digital power distribution networks.

Keywords:

protective relays; IEC 61850; GOOSE; sampled values; power system protection; network load 1. Introduction

The IEC 61850 standard forms the foundation of the discussed digital innovations. Developed in 2004 by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), it defines a universal communication model for substation automation and power systems. Its primary goal is to ensure interoperability and seamless integration of Intelligent Electronic Devices (IEDs), which eliminates the limitations typical of traditional, proprietary protocols [1,2].

Within the IEC 61850 standard, two key mechanisms are responsible for handling time-critical information: GOOSE (Generic Object Oriented Substation Event) and SV (Sampled Values). GOOSE is a low-latency, high-reliability, event-based protocol designed for real-time control and monitoring tasks. SV, on the other hand, is used for streaming digital samples of analog signals (current and voltage), which are essential for precise protection functions. However, the high sampling rate requirements of SV create a risk of network congestion. In response to this challenge, effective load reduction methods have been developed, including data aggregation, signal compression, and feature extraction techniques. These solutions, by minimizing bandwidth and latency requirements, are crucial in monitoring systems for extensive critical infrastructure, where there is also a need to process large volumes of data [1,3,4].

The modern energy sector faces growing demands for digitalization, automation, and enhanced flexibility and resilience of the power infrastructure. However, while the literature largely focuses on transmission and distribution substations, considerably less attention has been devoted to industrial power substations, where the behavior of protection and control systems directly determines the continuity of technological processes. In industrial environments—such as manufacturing plants, petrochemical facilities, metallurgical operations, or pulp and paper mills—that operate their own transformer stations, generators, and power protection systems, any delay in the operation of protective relays, automation schemes, or communication systems may lead not only to power supply failures but also to process disturbances, product losses, and prolonged production recovery times. Although several studies have addressed communication delays and response times in transmission and distribution substations [5,6], the literature still lacks a thorough investigation of the correlation between plant load, technological process characteristics, and protection operation delay in industrial settings. For example, the works presented in [7,8] highlight the specific challenges associated with industrial power systems and protection coordination, yet they do not focus on the dependency of protection reaction times on generator or plant load conditions. Delays within protection systems—whether caused by measurement, communication, or switching action—have a direct impact on the reliability and safety of industrial facilities. The authors of [6] demonstrated that in process-bus-based substation networks, delays may become a critical factor within the time margins of protection functions. In industrial environments, where production cycles are tightly scheduled, any instability in power supply or transient disturbances in power quality can result in significant downtime costs, material waste, or the need to shut down entire technological lines.

In the rapidly advancing energy sector, reliable and high-precision time synchronization has become a fundamental requirement for ensuring the safe, efficient, and coordinated operation of complex systems. The IEEE 1588 Precision Time Protocol (PTP), particularly in its second version (PTPv2), has emerged as a pivotal technology capable of achieving sub-microsecond accuracy in Ethernet networks, which renders it directly applicable to railway infrastructure [9].

Within the power sector, PTP is an integral component of modern Substation Automation Systems (SASs) compliant with the IEC 61850 standard, which forms the basis for the digitalization and interoperability of Intelligent Electronic Devices (IEDs). Precise time synchronization is indispensable for a range of critical functions. For instance, the Sampled Values (SV) protocol, used for the real-time transmission of digital samples of analog signals (currents and voltages) from Merging Units (MUs) to protection and control systems, requires a sampling accuracy of 1 µs or better. Consequently, PTPv2 is utilized by Three-Phase Merging Units (TPMUs) to assign timestamps to each measurement sample, ensuring the integrity and security of SV transmissions. Synchronization accuracy at the 1 µs level is essential for protection automation systems to meet their performance and reliability criteria. Even GOOSE messages, which facilitate the rapid exchange of event-based information, rely on precise time synchronization for correct and coordinated operation [1,10,11].

However, the implementation of PTP in the energy sector presents several challenges. Fluctuations in the propagation delay of PTP messages, resulting from network traffic load, can lead to synchronization errors. Studies have shown that PTP performance is dependent on the selection of the grandmaster and slave clocks, with significant variations in jitter being possible. Transparent Clocks (TCs) and Boundary Clocks (BCs) are crucial for precisely compensating for delays introduced by network traffic, including that generated by SV and GOOSE. Analyzing their ability to accurately measure the residence time of a PTP message within a switch is critical, especially in heavily loaded Ethernet networks. Although increasing the prioritization of PTP messages in Ethernet networks is often recommended, it may not be necessary when using Transparent Clocks with the peer-delay mechanism, as these devices effectively compensate for queuing delays. Despite these challenges, PTP, in accordance with the IEEE Std. C37.238-2011 fulfills the synchronization requirements for SV process busses in shared networks [10]. The main clock, to which all devices synchronize, is called the “Grandmaster,” and the devices that receive this time and synchronize to it are called the “slave clock”.This process involves sending and receiving PTP messages with timestamps, which allow the Slave clocks to adjust to the Grandmaster clock’s time. A constant flow of time information and correction of any errors ensures precise indications and synchronization of clocks in the network. This protocol uses two types of messages: event messages (Sync, Delay_Req, Pdelay_Req, and Pdelay_Resp), which convey time information between devices, and general messages, which fulfill various communication functions in the PTP protocol. General messages include Announce, Follow_Up, Delay_Resp, Pdelay_Resp_Follow_Up, Management and Signaling [12,13,14,15]. The device synchronization procedure based on the basic exchange of PTP time messages is presented in Figure 1 and includes the following stages:

Figure 1.

Clock synchronization process between the “Grandmaster” and “Slave clock” device—basic exchange of PTP time messages.

- SYNC Messages—in this data packet, the Grandmaster clock sends SYNC messages to all Slave clocks with its current time.

- Follow-Up Messages—after sending the SYNC message, the Grandmaster clock sends a Follow-Up message which contains more precise time information related to the just-sent “SYNC Message.” Thanks to this information, the Slave device is able to calculate the propagation delay.

- Delay Request (Delay-Req) Messages—this is a message from the Slave clock to the Grandmaster, in which there is a request to measure the delay time between them. This information includes a timestamp indicating when this message was sent.

- Delay Response (Delay-Resp) Messages—the Grandmaster clock responds to Delay-Req messages by sending a Delay-Resp message back to the Slave clock. The data packet sent in this message contains the same timestamps as received in the Delay-Req message. By comparing the timestamps in the Delay-Req and Delay-Resp messages, Slave clocks can calculate the propagation delay more precisely.

In connection with the above, the delay and offset (differences between two reference times) are as follows:

If the connection to the Grandmaster clock is lost or the signal quality is so poor that signals arrive with a significant delay (this information is in the “Announce” message), a distributed algorithm for selecting a new Grandmaster clock, called BMCA (Best Master Clock Algorithm), is initiated. The purpose of this algorithm is to select a Grandmaster clock that will serve as the time reference for the other clocks. All clocks participate in the selection process to determine which one has the best time reference.

For the energy sector, the peer-to-peer (One Step) approach is used; delay measurement takes place between two ports of connected devices. The sequence of individual steps is shown in Figure 2, which is as follows:

Figure 2.

Method of measuring propagation delays of PTP time standard using the “peer-to-peer” (One Step) mechanism.

- Port-1 sends a Pdelay_Req message and generates timestamp for this message,

- Port-2 receives the Pdelay_Req message and generates timestamp ,

- Next, Port-2 sends a Pdelay_Resp message and generates timestamp . To minimize errors resulting from frequency differences between PTP ports, Port-2 sends the Pdelay_Resp message as quickly as possible after receiving the Pdelay_Req message,

- Port-2 transmits the difference between timestamps and in the Pdelay_Resp message, or in a separate Pdelay_Resp_Follow_Up message, or transmits both timestamps in both of these messages,

- Port-1 generates timestamp after receiving the Pdelay_Resp message,

- Port-1 uses these four timestamps to calculate the average PTP link delay between the two devices.

The increasing demand for reliability and uninterrupted operation in critical industrial environments, such as power stations and heavy industry, necessitates the implementation of advanced network topologies to support digital protection automation systems. To minimize downtime resulting from communication failures, two key redundancy protocols are widely adopted, defined under the IEC 62439-3 standard: Parallel Redundancy Protocol (PRP) and High-availability Seamless Redundancy (HSR) [16]. PRP (Parallel Redundancy Protocol) utilizes two completely independent Local Area Networks (LANs), allowing simultaneous transmission of identical data frames over both paths to the destination node. This architecture ensures zero recovery time in the event of a single network failure, as the receiving device automatically selects the first arriving frame and discards duplicates. The independence of the two LANs—referred to as LAN A and LAN B—not only guarantees fault tolerance but also enables deterministic communication, which is essential in time-critical applications such as protection automation systems. In the experimental setup described in this study, each Intelligent Electronic Device (IED) was equipped with dual network interfaces and operated within a PRP environment, receiving time synchronization signals from two separate clocks (Master and Slave) distributed across both networks. This configuration, shown in Figure 3, illustrates the physical separation of the redundant paths and the integration of switches (LAN A and LAN B) and time servers, which collectively form the backbone of the high-availability industrial communication infrastructure [17,18,19,20].

Figure 3.

PRP (Parallel Redundancy Protocol) network topologies.

HSR (High-availability Seamless Redundancy) employs a ring topology in which each node forwards Ethernet frames simultaneously in both clockwise and counterclockwise directions. This bidirectional transmission ensures that data reaches its destination even if a single link or node within the ring fails, thereby providing seamless redundancy without any recovery time. Unlike PRP, which requires two physically separate networks, HSR achieves fault tolerance within a single logical ring, reducing infrastructure complexity. However, this approach necessitates that all participating devices support HSR natively, including frame duplication, filtering, and forwarding mechanisms. In the tested system, HSR could offer enhanced resilience and deterministic communication, particularly in time-critical applications such as protection automation. The topology of the industrial network infrastructure, including the redundant paths and device interconnections, is illustrated in Figure 4 of the article [17,18,19,20].

Figure 4.

HSR (High-availability Seamless Redundancy) network topologies.

Both protocols achieve zero-recovery-time upon a single failure, a requirement critical for time-sensitive protection messages like GOOSE and Sampled Values (SV). While PRP offers greater reliability due to its fully duplicated network structure, HSR is often preferred in smaller installations due to lower infrastructure costs.

Comparative analyses show that PRP and HSR provide significantly faster switchover times (near zero milliseconds) compared to traditional link redundancy protocols like RSTP (Rapid Spanning Tree Protocol), which can introduce unacceptable delays (up to several hundred milliseconds). As demonstrated by Bernardino [21], RSTP, despite its improvements over legacy STP, still relies on dynamic topology recalculation and convergence mechanisms that are inherently non-deterministic. This makes it unsuitable for time-critical applications such as GOOSE and Sampled Values communication in digital substations.

Modern power systems are increasingly digitalized and integrate protection automation within centralized control and protection schemes. The introduction of communication based on IEC 61850-compliant protocols enables significant improvements in flexibility and coordination of protective functions; however, it also introduces new challenges related to transmission delays, time synchronization, and overall system reliability. Time delays in the exchange of trip signals between protective devices can lead to prolonged fault durations and increased thermal losses in power cables and conductors, which in turn affects the durability of system components and operational safety. In recent years, there has been a growing number of studies addressing complex coordination and reliability of protection systems within integrated network structures. In [22], an approach based on policy learning is presented, ensuring safe and coordinated operation of multi-energy microgrids, where limiting congestion and control delays is critical. In [23], a method for assessing power system reliability considering topological uncertainties and nodal power variations is proposed, which can be directly related to issues concerning the reliability and temporal coordination of digital protection systems.

The power system protection schemes increasingly rely on digital substations and communication networks compliant with the IEC 61850 standard. The foundation of proper operation in such systems is precise time synchronization, typically implemented using the Precision Time Protocol (PTP, IEEE 1588), which enables reliable comparison of phase angles and measurement values across Intelligent Electronic Devices (IEDs) and allows for fast responses to fault events [24,25]. The literature emphasizes that microsecond-level synchronization accuracy is critical not only for the correct functioning of protective functions but also for minimizing delays caused by communication in the digital network and signal processing within the executing devices [25,26]. High-precision synchronization ensures that the protection algorithms can operate deterministically, even under high network load or in the presence of transient disturbances. In both laboratory and industrial settings, communication delays resulting from network congestion, packet queuing, and clock jitter significantly affect the overall operating time of protection systems [27,28]. Modeling these delays and their impact on protective actions is a key step in designing modern digital protection systems, enabling engineers to define requirements for network bandwidth, traffic prioritization, and hardware redundancy [19,26,29]. Various approaches have been proposed in the literature for evaluating process bus network performance, including simulation-based methods and hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) testing, which allow for the quantification of latency as a function of the number of data streams, sampling frequency, and network topology [19,28,30]. Such modeling is essential to understand how network-induced delays propagate through protection functions and affect operational reliability. Furthermore, research on digital substations highlights the importance of cyber-physical system modeling, encompassing both power system dynamics and network communication aspects, including the analysis of GOOSE and SV messages under high-load scenarios [27,31]. The practical implications of these studies include improving the safety and reliability of protection systems, optimizing communication architectures, and implementing mechanisms to minimize latency, such as deterministic Ethernet (TSN, HSR, PRP) and adaptive algorithms in IEDs [24,29,32]. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of network delays and time synchronization is an essential aspect of designing modern digital protection systems in compliance with the IEC 61850 standard.

Modern protection automation systems significantly improve the accuracy of fault detection and the effectiveness of response to all types of emergency conditions in protected networks and circuits [17,33]. They ensure full selectivity of protection operation, enable archiving of the performance of individual protection devices and intermediate elements during the disturbance response, and additionally record and archive the disturbance signal itself, including its waveform and time-domain variations [34]. This functionality makes it possible not only to reconstruct the system’s reaction to a disturbance but also to correctly identify the event and trigger the appropriate protective action (activation of the designated switching device) without the risk of unintended operations of auxiliary components that could result in the unnecessary disconnection of a greater number of circuits than those actually affected by the fault [35]. However, these systems also have certain limitations. They are not related to a higher probability of failure—since this risk is mitigated by the use of redundant configurations—but stems from their inherent complexity. The processing of the disturbance signal, its identification, transmission to the actuating device, and subsequent feedback reading require additional operations, which extend the overall reaction time compared to conventional protection systems [33,36]. This issue may be further exacerbated by network traffic and challenges in maintaining precise real-time synchronization. As a consequence, the duration of the fault until its clearance becomes longer. This is particularly critical in the case of short circuits, as prolonged fault current flow increases the amount of thermal energy released in the installation. In turn, the additional heating of conductors and components may necessitate the oversizing of applied cables and the selection of larger cross-sections to ensure the safe and reliable operation of the system.

Emphasizing, in modern protection automation systems, accurate time synchronization—most commonly achieved using the Precision Time Protocol (PTP, IEEE 1588)—is the foundation of correct system operation. Microsecond-level synchronization accuracy is a prerequisite for the proper functioning of Intelligent Electronic Devices (IEDs) and for the transmission and analysis of sampled voltage and current data under the Sampled Values (SV) standard. When synchronization is properly maintained, protection devices can reliably compare phase and measurement values and make fast tripping decisions. However, when synchronization quality deteriorates—for example, due to time offset, clock jitter, or PTP packet loss—additional buffering and correction mechanisms become necessary, inevitably introducing further signal processing delays within the IED. Another link in this cause-and-effect chain is the communication network load within the substation. In typical digital architectures, multiple measurement (MU) and protection (IED) devices simultaneously publish SV and GOOSE messages, often using multicast transmission. As the number of devices, sampling frequency, and engineering traffic increase, network congestion can occur, leading to packet queuing, delay fluctuations, and increased jitter. In Ethernet switches—especially those lacking proper QoS configuration or equipped with undersized buffers—temporary transmission bottlenecks may occur, extending the total delivery time of samples to the receiver. Furthermore, when deterministic communication mechanisms (e.g., TSN, HSR, PRP) are not implemented, the risk of SV frame misordering arises, requiring reordering at the receiving end. As a result, not only the average latency but also its variability increase, which negatively affects the stability and predictability of protection algorithms. Packet transmission delays are not merely a communication problem—they have a direct impact on the performance of protection systems. Each IED must process the received data: time-align it, perform computations (e.g., symmetrical component transformation, RMS estimation), and make a logical tripping decision. When SV samples arrive with delays or irregular timing, the device must wait for the full frame set or use interpolation algorithms, both of which extend the overall protection operating time. In systems where the tripping decision depends on data from multiple measurement points—such as in differential protection schemes—delay asymmetry among channels introduces additional timing errors, necessitating safety margins that further prolong the total clearing time in practice.

Increased latency and jitter directly translate into longer fault durations. The total fault-clearing time includes both the detection time within the IED, the communication delay, and the mechanical opening time of the breaker. The thermal energy released in a conductor during a fault is proportional to the integral and for a constant fault current. This means that even a slight increase in the protection operating time leads to a proportional rise in thermal energy dissipated in the fault path. For example, if the fault current equals 5000 A and the fault-path resistance is 0.01 , extending the clearing time from 0.2 to 0.4 s increases the released energy from 50 kJ to 100 kJ—i.e., doubles it. Such a significant thermal increase may exceed the permissible operating temperature of conductors, damage insulation, or permanently degrade the short-circuit endurance of network components.

This means that even a slight increase in the protection operating time leads to a proportional rise in thermal energy dissipated in the fault path. For example, if the fault current equals and the fault-path resistance is , extending the clearing time from to increases the released energy from to —i.e., doubles it. Such a significant thermal increase may exceed the permissible operating temperature of conductors, damage insulation, or permanently degrade the short-circuit endurance of network components.

Consequently, an incorrect or incomplete assessment of communication delay effects may lead to dangerous secondary phenomena in power systems. Longer clearing times result in higher thermal stress and, consequently, an increased risk of equipment failure, insulation degradation, or fire hazards. In many protection system designs, the impact of SV and GOOSE traffic congestion on actual operating times is still neglected, leading to underestimation of protective device requirements and insufficient thermal margins in cables and joints. Therefore, when analyzing modern protection systems, communication and synchronization delays should be treated as critical technical factors influencing both safety and equipment longevity. Effective mitigation requires stable time synchronization (redundant and monitored PTP sources), deterministic data transmission (e.g., via TSN, HSR, or PRP), as well as traffic prioritization (QoS) and local fallback algorithms within IEDs. At the same time, cable and protection system design should account for potential fault-clearing time extensions by analyzing their impact on short-circuit energy (I2t) and the thermal endurance of current-carrying components. Only such a holistic approach ensures consistency between the digital communication layer and the physical resilience of power system infrastructure.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a detailed exposition of the laboratory test-bed configuration and the established measurement methodology. This chapter presents an analysis of the influence of digital network load on the operating time of protective relays across three distinct load scenarios. The empirical data derived from these experiments form the basis for the quantitative assessment of the correlation between network traffic characteristics and the consequential delay in the protection system’s response. Section 3 subsequently investigates the ramifications of the identified delays with respect to the thermal energy dissipated within the fault circuit, using a single-phase-to-ground fault as a case study. A simplified thermal analysis is conducted to determine the total fault-clearing time, which is expressed as the summation of the experimentally measured protection delay () and the mechanical operating time of the circuit breaker (). Finally, Section 5 synthesizes the principal research findings and presents the resulting conclusions regarding the direct relationship between an elevated data sampling frequency and a corresponding increase in protection trip time. These conclusions offer practical recommendations for optimizing network parameters and selecting appropriate equipment in modern protection and automation systems.

2. Impact of Protection System Configuration and Network Traffic on the Operating Delays of System Actuators—Laboratory Measurement

The subject of this chapter is a case study of a specific research scenario regarding the performance of distribution switchgear within Medium Voltage (MV) and Low Voltage (LV) grids. The structure of the chapter comprises two principal sections. In the first section, the configuration of the experimental setup is detailed, specifying the applied instrumentation and the established connection topology. The second section is dedicated to a thorough analysis and interpretation of the findings from the experiments performed.

2.1. Experimental Setup and Case Study Analysis

A research test bed, presented in Figure 5, was prepared in the hardware laboratory to analyze the power supply and control structures within digital protection automation solutions.

Figure 5.

Research station in the laboratory.

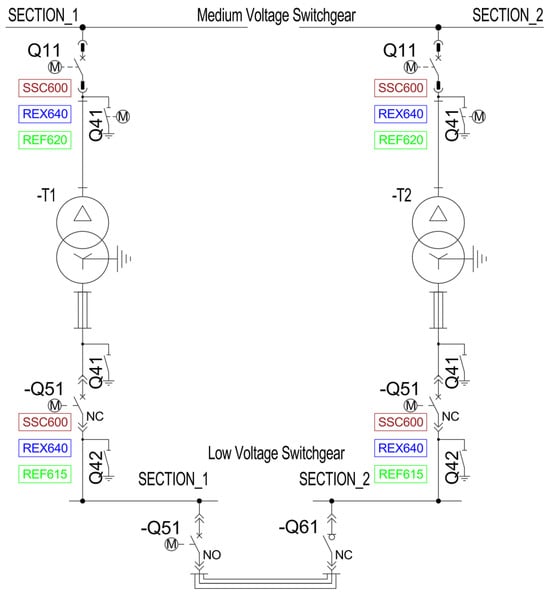

The laboratory test stand was constructed to conduct precise functional verification and dynamic measurements of protection systems within an environment emulating a digital substation architecture compliant with the IEC 61850 standard. The stand’s design facilitates the simulation of a two-section low-voltage switchgear and its corresponding medium-voltage feeder bays. The core of this configuration is the HYPERION 400 network switch, which serves as the communication backbone, enabling data exchange and precise synchronization among all Intelligent Electronic Devices (IEDs). The analysis was conducted using the REF615, REF620, and REX640 protection relays, as well as the centralized feeder protection device SSC600. The detailed network topology of the system, including the locations of the individual protection relays, is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Power supply system topology for MV and LV.

To ensure the necessary temporal accuracy for evaluating protection performance, a TIME SERVER HYPERION 500 (BitStream S.A., Lublin, Poland) is employed. This device acquires a reference signal from the GPS system and subsequently distributes the synchronized time signal to the HYPERION 400 switch (BitStream S.A., Lublin, Poland), guaranteeing event coordination across the entire network. The switches were equipped with 1 Gb ports, with the exception of the uplink ports which had speed, as can be observed in Figure 7. For test execution and data acquisition, a sophisticated OMICRON TESTER is utilized, which performs a dual function: firstly, it injects current signals (CURRENT) into the analog inputs of a selected relay (e.g., REF615), simulating a network fault condition such as a short circuit; secondly, it monitors the relay’s contact outputs. The tripping signal (TRIP) generated by the relay is coupled to the tester’s binary inputs (B.In1, B.In2, B.In3). The protection settings were configured to 50A (with a current transformer ratio of 1:100). The simulation stage was based on three sequences: Sequence 1—40A (normal operation state), Sequence 2—60A (fault state), and Sequence 3—40A (normal operation state). This setup allows the OMICRON Tester to precisely measure the total protection trip time—defined as the latency between the initiation of the fault simulation and the registration of the tripping signal. The entire testing methodology relies on a coherent, synchronized network architecture, enabling accurate verification of the performance and reliability of the protection system components. The topology diagram of the research test stand is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 7.

Industrial network topology for the studied case.

Figure 8.

Topology diagram of the tested system.

These devices were mounted in a dedicated protection automation cabinet. All protection devices operated based on Parallel Redundancy Protocol (PRP) technology with two independent time sources, a Master and a Slave, connected to two separate Ethernet networks. The network infrastructure comprised two subsystems: System A and System B. Each system was equipped with two HYPERION-402 industrial switches and one HYPERION-500 real-time clock. The Grandmaster clock was connected to System A, while the second clock (Slave) was connected to System B. The network infrastructure topology is illustrated in Figure 7.

2.2. Results and Analysis

The objective of this analysis is to evaluate the impact of network infrastructure load on key performance parameters—specifically, the effectiveness and speed—of protection schemes within power system protection systems. The analysis is based on the results of laboratory measurements of a protection relay’s operating time, which are presented in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 1.

Measurement results for a network loaded with 6 streams at 80 samples per cycle.

Table 2.

Measurement results for a network loaded with 2 streams at 256 samples per cycle.

Table 3.

Measurement results for a network loaded with 4 streams at 256 samples per cycle.

The experiment comprised 31 measurement iterations for each of the three defined network load scenarios, considering input signals applied to three binary inputs (B.In 1, B.In 2, B.In 3). The measured response time, expressed in milliseconds (ms), was defined as the interval from the moment a test signal was applied to a binary input to the instant the relay generated a TRIP signal.

The selection of N = 31 measurement repetitions for each load scenario stems from a combination of rigorous statistical requirements and practical experimental constraints. First, from a statistical perspective, the chosen number of repetitions deliberately exceeds the commonly accepted threshold of , which is based on the Central Limit Theorem. This ensures that the distribution of sample means approximates a normal distribution, regardless of the underlying population distribution, allowing for the use of reliable parametric tests such as the Student’s t-test to compare mean delay times across different load scenarios. Second, in terms of estimation precision, the number N = 31 guarantees a sufficiently low margin of error, which is essential for accurate millisecond-level measurements. For example, in Scenario 2 (B.In 1), where the mean trip time was approximately 58.66 ms with a standard deviation of about 0.41 ms, the use of 31 repetitions enabled us to estimate the true mean with a margin of error of only ms at a confidence level. This level of precision is fully acceptable and sufficient to detect meaningful differences in protection system performance, where typical delays are measured in tens of milliseconds. Finally, from a practical standpoint, the number of repetitions represents an optimal balance between statistical rigor and the time and resource constraints of the specialized laboratory test bench, which includes the OMICRON Tester and dedicated IED relays. The study was conducted under three controlled scenarios, which differentiated the degree of network load by modifying the number of data streams and the sampling frequency (number of samples per cycle).

2.2.1. Scenario 1: Minimal Load

The network was loaded with 6 data streams at a sampling frequency of 80 samples per cycle. This scenario simulates typical operating conditions in standard Protection Automation Systems and was shown in Table 1.

2.2.2. Scenario 2: Medium Load

The network was loaded with 2 data streams at a sampling frequency of 256 samples per cycle. This configuration represents systems that, in addition to basic protection functions, also perform tasks related to data acquisition and transmission for power quality analysis and is shown in Table 2.

2.2.3. Scenario 3: Maximum Load

The network was loaded with 4 data streams at a sampling frequency of 256 samples per cycle, corresponding to a scenario of intensive network utilization for executing complex protection and diagnostic functions, as shown in Table 3.

2.3. Analysis

A comparative analysis of the empirical data clearly indicates a positive correlation between the level of network load and the operating time of the protection system.

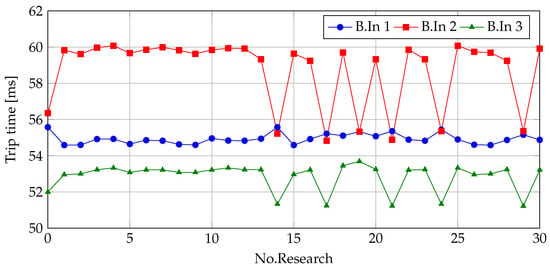

The captions for Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 are concise and they contain the two primary independent variables influencing the digital network load: the Number of Streams (defining data volume) and Samples per Cycle (s/c) (defining data density, where is typical for protection and for power quality monitoring). The core analytical focus requires comparing graphs that differ in only one of these parameters to verify the finding that sampling frequency has a more dominant impact on delay than stream count. In each of Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11, the results for three binary inputs are presented (B.In 1, B.In 2, B.In 3), which correspond to the physical measurement channels on the OMICRON TESTER where the protection relay’s tripping signal (TRIP) was monitored. The full context of connecting these inputs and the overall system topology is detailed in the “Experimental Setup” section and illustrated in Figure 8 Topology diagram of the tested system. Finally, Figure 12 serves as the synthesis of the previous results, providing direct visual evidence for the three load scenarios tested (Load (a), (b), (c)) chosen to demonstrate the impact of changing density versus changing volume; analysis of this figure allows for a clear assessment of the delay trend versus load, supporting the conclusion about the dominance of sampling frequency as the critical delay factor.

Figure 9.

Response time measurement graph for a network loaded with 6 streams at 80 samples per cycle.

Figure 10.

Response time measurement graph for a network loaded with 2 streams at 256 samples per cycle.

Figure 11.

Response time measurement graph for a network loaded with 4 streams at 256 samples per cycle.

Figure 12.

Comparison of the trip times for the binary input B.In 3 under different network loads. The respective series denote: (a) 6 streams, 80 samples/cycle; (b) 2 streams, 256 samples/cycle; and (c) 4 streams, 256 samples/cycle.

Minimal Load Conditions (6 streams, 80 samples/cycle): Under this scenario, the shortest response times were recorded. For binary input B.In 1, the operating time was approximately 55 ms (e.g., 55.58 ms in trial 0; 54.59 ms in trial 1). The B.In 3 input consistently exhibited the shortest response time, stabilizing at a level of about 53 ms. Figure 9 presents a graphical interpretation of the discussed results.

Medium Load Conditions (2 streams, 256 samples/cycle): An increase in network load resulted in a systematic extension of the response time across all analyzed inputs. For input B.In 1, the time increased to the 58–59 ms range (e.g., 59.84 ms in trial 0). Input B.In 2 was characterized by the highest variance in its results, with values frequently exceeding 63 ms (e.g., 63.90 ms in trial 2). The response time for input B.In 3 was predominantly in the 56–57 ms range. Figure 10 presents a graphical interpretation of the discussed results.

Maximum Load Conditions (4 streams, 256 samples/cycle): Further intensification of the network load led to the longest recorded operating times. For input B.In 1, the response time remained at approximately 59–60 ms. For input B.In 2, values often exceeded 62 ms, reaching a maximum of 63.75 ms. The times for B.In 3 were maintained in the 56–57 ms range. Figure 11 presents a graphical interpretation of the discussed results.

Furthermore, the research results indicate a distinct correlation between network traffic characteristics and the operational delay of the protection relay. To quantify this phenomenon, a simulation analysis was conducted, replicating three load scenarios on the communication infrastructure. The first scenario involved traffic generated by six Sampled Values (SV) streams with a sampling rate of 80 samples/cycle, which is typical for protection automation systems. The second and third scenarios incorporated data streams with a higher sampling rate of 256 samples/cycle, characteristic of power quality measurements, comprising two and four streams, respectively.

A comparative analysis of the collected data conclusively demonstrates that increasing the sampling rate of the data streams has a more significant impact on extending the relay’s operating time than merely increasing the number of streams. This relationship is illustrated by a comparison of the protection trip signal waveforms recorded at output B.In3, as presented in Figure 12.

2.4. Statistical Analysis Tables

This section presents a comprehensive statistical summary of the experimental results obtained from the three network load scenarios. The goal of this analysis is to provide a quantitative foundation for comparing the performance differences among the varying test conditions. Key statistical indicators—including the Mean Trip Time (), Variance (), and Standard Deviation (s)—are calculated for each binary input (B.In 1, B.In 2, B.In 3) across the minimum, medium, and maximum load configurations. These metrics are crucial for establishing the reliability and magnitude of the protection system’s operational delay () under different levels of digital traffic intensity.

2.4.1. Scenario 1: Minimum Load (6 Streams, 80 Samples/Cycle)

Compilation presents the statistical summary of measurement results for Scenario 1: Minimal Load. The table details key metrics, such as the mean trip time (), variance (), and standard deviation (s), for each of the binary inputs B.In 1, B.In 2, and B.In 31. This data set, characterized by the shortest response times in the experiment, serves as a baseline reference for heavier loaded scenarios, and its quantitative assessment is critical for verifying the repeatability of the trip times (). These key metrics, crucial for the reliability analysis, can be observed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Scenario 1: Statistical Summary (6 streams, 80 samples/cycle).

Detailed Analysis: B.In 1

This compilation is a detailed statistical analysis of the results for binary input B.In 1 in Scenario 1 (Minimal Load)3. The table shows the calculation formulas and resulting values for the mean (), Sum of Squared Differences, variance (), and standard deviation (s)4. This analysis quantitatively confirms the very low variance (), providing evidence of high repeatability of trip times for this channel. The precise quantitative parameters of the B.In 1 measurements can be observed in Table 5.

Table 5.

B.In 1 Analysis: Scenario 1.

Detailed Analysis: B.In 2

This table provides a detailed statistical analysis of the trip time measurements for binary input B.In 2 in Scenario 16. The compilation includes calculations for key statistical indicators, including variance () and standard deviation (s). These values are important because this channel showed the highest variance () of all inputs under minimal load conditions. The statistical instability of operation on this particular input can be observed in Table 6.

Table 6.

B.In 2 Analysis: Scenario 1.

Detailed Analysis: B.In 3

This compilation represents a detailed statistical analysis of the results for binary input B.In 3 in Scenario 1 (Minimal Load). The table includes statistical calculations for the mean (), Sum of Squared Differences, variance (), and standard deviation (s). This data is crucial because input B.In 3 consistently showed the shortest response times, stabilizing at approximately 53 ms. The repeatability and accuracy of the fastest results for minimal network load can be observed in Table 7.

Table 7.

B.In 3 Analysis: Scenario 1.

2.4.2. Scenario 2: Medium Load (2 Streams, 256 Samples/Cycle)

This compilation presents the statistical summary of results for Scenario 2: Medium Load. The table includes values for the mean trip time (), variance (), and standard deviation (s) for inputs B.In 1, B.In 2, and B.In 3. The shift from 80 to 256 samples/cycle is the key factor in this scenario, allowing the assessment of how the increase in data density affects the operational delay. The impact of the sampling frequency increase on the extension of the operational delay () can be observed in Table 8.

Table 8.

Scenario 2: Statistical Summary (2 streams, 256 samples/cycle).

Detailed Analysis: B.In 1

This compilation is a detailed statistical analysis of the results for binary input B.In 1 in Scenario 2 (Medium Load)15. The table contains calculations and resulting values for the mean (), Sum of Squared Differences, variance (), and standard deviation (s). The data confirms a systematic increase in the mean trip time on B.In 1 to the range compared to Scenario 1. The precise statistical parameters of this channel under high sampling frequency conditions can be observed in Table 9.

Table 9.

B.In 1 Analysis: Scenario 2.

Detailed Analysis: B.In 2

This table provides a detailed statistical analysis of the trip time measurements for binary input B.In 2 in Scenario 2. The compilation presents statistical calculations, including the very high variance (). This channel showed the greatest delays and highest variance in this scenario, with values frequently exceeding . The quantitative confirmation that B.In 2 is the most sensitive to this load can be observed in Table 10.

Table 10.

B.In 2 Analysis: Scenario 2.

Detailed Analysis: B.In 3

This compilation represents a detailed statistical analysis of the results for binary input B.In 3 in Scenario 2. The table captures the statistical calculations of the mean (), variance (), and standard deviation (s). Although the overall load increased, response times for B.In 3 remained relatively short, stabilizing in the range. These data, quantifying the repeatability and extension of the shortest trip times, can be observed in Table 11.

Table 11.

B.In 3 Analysis: Scenario 2.

2.4.3. Scenario 3: Maximum Load (4 Streams, 256 Samples/Cycle)

This compilation presents the statistical summary of results for Scenario 3: Maximum Load. This scenario combines high data density (256 samples/cycle) with an increased number of streams (4 streams). The table contains values for the mean trip time (), variance (), and standard deviation (s) for inputs B.In 1, B.In 2, and B.In 3. Comparison with Scenario 2 allows for the evaluation of whether increasing the number of streams (data volume) further impacted the delay. These findings can be observed in Table 12.

Table 12.

Scenario 3: Statistical Summary (4 streams, 256 samples/cycle).

Detailed Analysis: B.In 1

This compilation is a detailed statistical analysis of the results for binary input B.In 1 in Scenario 3 (Maximum Load). The table shows the calculations and resulting values for the mean (), variance (), and standard deviation (s). The data is crucial as it shows that the mean delay on B.In 1 did not increase significantly compared to Scenario 2, supporting the conclusion about the dominant impact of sampling frequency. This phenomenon can be observed in Table 13.

Table 13.

B.In 1 Analysis: Scenario 3.

Detailed Analysis: B.In 2

This table provides a detailed statistical analysis of the trip time measurements for binary input B.In 2 in Scenario 3. The compilation presents statistical calculations, including the second highest variance () and a very high mean trip time. This channel recorded the absolute greatest delays in the study, reaching a maximum of . Quantitative confirmation that B.In 2 is the most sensitive to this load can be observed in Table 14.

Table 14.

B.In 2 Analysis: Scenario 3.

Detailed Analysis: B.In 3

This compilation represents a detailed statistical analysis of the results for binary input B.In 3 in Scenario 3. The table includes the statistical calculations for the mean (), variance (), and standard deviation (s). Despite the maximum network load, the results for B.In 3 stabilized in the relatively short range. These data, quantifying the precision parameters for this channel under extreme network traffic conditions, can be observed in Table 15.

Table 15.

B.In 3 Analysis: Scenario 3.

The comprehensive analysis of the experimental data unequivocally demonstrated that the key factor influencing the system’s operational delay is the increase in the sampling frequency of the data streams, which has a significantly more dominant impact than merely increasing the number of streams. This phenomenon strongly suggests the existence of an IED (Intelligent Electronic Device) processing bottleneck, rather than solely network bandwidth saturation.

IED devices are typically designed for protection automation systems with a sampling frequency of 80 samples per cycle. In contrast, 256 samples per cycle are used in power quality measurement systems. Including both streams in a single subnetwork without aggregation may cause problems within IED devices that were designed to analyze a lower volume of samples.

We confirm that the observed relationship—in which the sampling frequency () had a more dominant impact on the trip delay than the stream count—directly indicates an internal IED processing bottleneck. The results constitute a critical basis for design principles:

- The established correlation between sampling frequency and delay is sufficient to formulate optimization criteria for design engineers, which was the main objective of the experiment.

- A deep isolation of the delay sources—specifically determining whether the cause is network bandwidth saturation or the overloading of internal IED processing mechanisms—would require access to proprietary hardware and software architectures, which was beyond the scope of this experiment.

- Further exploration of this internal IED bottleneck will be utilized in future work focusing on IED-level optimization.

This quantification empirically proves that the system delay is dominated by resource utilization dictated by data density (frequency), rather than data volume (stream count), establishing a new criterion for optimizing IEC 61850 parameters in digital substations.

3. The Impact of Protection Tripping Delay Time on the Amount of Thermal Energy Generated During a Short-Circuit Phenomena

In this chapter, the impact of the time delays identified in the previous section of the article—based on laboratory tests—on the additional amount of energy released in the fault circuit is demonstrated using the example of a single-phase-to-ground fault. It should be noted that each communication process between the components forming part of the protective automation system architecture extends the time interval between the occurrence of a fault (in this case, a short-circuit) and the actual initiation of operation by the system’s actuating device. As demonstrated in the previous sections of this study, the magnitude of this operating delay depends on multiple factors. To illustrate the significance of this phenomenon, and to assess whether it may cause operational issues such as cable overheating during fault conditions, this chapter presents a simplified analysis of the thermal energy released in the course of a short-circuit event. The assessment was performed in reference to standardized methodologies defined in IEC 60909 (short-circuit current calculations) and IEC 60949 (calculation of thermal effects of short-circuit currents). Assuming that the voltage at the instant of fault occurrence can be expressed as [37,38]:

where:

- —peak phase voltage [V]

- —angular frequency [rad/s]

- —initial phase of voltage [rad]

- —fault angle [rad]

The remote short-circuit current, typical for faults occurring in the considered electrical installation, can be represented as the sum of an AC component and a DC component:

while the switch is:

where:

- —peak value of the fault current [A],

- —time constant of the DC component [s], depending on the system ratio and fault location.

In turn, the peak fault current can be expressed in terms of the RMS value of the AC short-circuit current and the system X/R ratio:

where:

- —RMS value of the short-circuit current [A],

- R—total resistance of the fault loop [],

- X—total reactance of the fault loop [].

This expression accounts for the initial DC offset due to the system impedance, which decays exponentially with time constant , and is essential for accurately modeling remote fault currents in medium-voltage electrical installations.

The parameters assumed for determining the short-circuit current waveform are as follows: the resistance of the fault loop R is equal to , and the reactance of the fault loop X is equal to . To extend the analysis, a family of short-circuit current waveforms was assumed for different values of the ratio (, , ), which influence the time constant that determines the decay of the DC (aperiodic) component of the short-circuit current, under the assumption of a constant amplitude of the steady-state short-circuit current Figure 13.

Figure 13.

The family of short-circuit current waveform (Where red color represents , green color represents 0.8, blue color represents 0.6, and black color represents 0.4).

The delay introduced by advanced protection automation systems can significantly affect the amount of thermal energy released in a cable during the initial period of a short-circuit. In Section 2, the time delays were presented, understood as the interval between the generation of the anomaly signal at the outputs of the tester (initiating the short-circuit process) and the activation of the high-current relay outputs (using the Omicron test device). To the laboratory-measured delay, the mechanical operation time of the circuit breaker must be added—i.e., the time required for the mechanical arc extinction and current interruption until the current reaches zero. This mechanical time is typically assumed in the range of = 70–120 ms [39,40]. Therefore, the total duration of short-circuit current flow until extinction in the proposed protection system solutions can be expressed as:

Assuming that the mechanical time varies within the above-mentioned range (70–120 ms), and that the laboratory-determined delay times , presented in Section 3 for the full spectrum of measurements, range from 51 ms to approximately 64 ms, the thermal energy released in the cable can be calculated for total short-circuit durations ranging from the minimum = 121 ms to the maximum = 184 ms, according to the following relation:

where:

- —thermal energy released in the cable [J],

- R—cable resistance [],

- —short-circuit current as a function of time [A],

- —total duration of current flow until its extinction [s].

Firstly, in order to demonstrate the impact of varying the time constant of the aperiodic component decay, Figure 14 presents the square of the short-circuit current for the assumed fault scenarios.

Figure 14.

The square of the short-circuit current for the assumed fault scenarios (Where red color represents , green color represents 0.8, blue color represents 0.6, and black color represents 0.4).

The values of energy released in a sample section of a 10 copper conductor cable with a length of 1 m (, neglecting the energy dissipated through natural thermal convection) over time, for the family of short-circuit current waveforms presented in Figure 14, are shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Cumulative thermal energy released during short-circuit process (Total thermal energy released as a function of time, where red color represents , green color represents 0.8, blue color represents 0.6, and black color represents 0.4).

However, the Joule integral itself is much more illustrative since it is not normalized by the resistance value. Therefore, it can be treated as an absolute quantity for a given short-circuit scenario. The Joule integral released within the fault circuit, including the faulted (short-circuited) cable, is illustrated using a reference fault scenario presented in Figure 16 (based on formula .

Figure 16.

The cumulative Joule energy released over time under the assumed short-circuit conditions (Where red color represents , green color represents 0.8, blue color represents 0.6, and black color represents 0.4).

Additionally, in Figure 16, the possible ranges of cumulative Joule integral values are illustrated. The ranges corresponding to the characteristic clearing time of fault current extinction to zero (70–120 ms) in conventional protection systems—without protective logic elements, communication interfaces, or data acquisition modules—are shown in magenta. These systems rely solely on selectively coordinated switching devices (e.g., circuit breakers). In contrast, the values of Joule energy released during the fault process within the fault circuit, including the short-circuited cable of the electrical installation, are highlighted in red. These correspond to the advanced protection-automation systems described in the first part of the study, which introduce additional time delays across the full range of delay values determined experimentally in Section 2 (from to ).

The extreme values of the Joule integral for individual times (6), illustrating the impact of delay times introduced by advanced protection-automation schemes on the amount of thermal energy generated during the fault process for the family of fault current characteristics shown in Figure 14, are presented in Table 16.

Table 16.

The extreme values of the Joule integral (Transposed).

If it is assumed that the permissible Joule integral (adiabatic short-circuit withstand) is expressed by the formula:

where:

- —permissible Joule integral [·s],

- k—material-insulation constant (dependent on the conductor material, insulation type, and assumed initial and final temperatures),

- S—conductor cross-section [].

And for copper in PVC insulation a commonly used value is assumed (indicative values according to IEC standards), and for copper in XLPE insulation: (indicative values according to IEC standards). The calculation for the copper conductor with PVC insulation.

Then becomes possible to determine how the delay time introduced by modern protection-automation systems can affect the need to oversize cables, which under the given assumed conditions would be sufficient in conventional protection schemes based solely on individual switching devices (without communication). By comparing the data in Table 16, which presents the Joule integrals that can be released under the assumed short-circuit scenarios for characteristic protection operating times considering the analyzed time delays, with the maximum permissible breaking Joule integrals listed in Table 17 for two types of cable insulation, it can be observed, for example, that in the case of the variant: assuming the minimum mechanical breaking time () of the short-circuit in a conventional protection system, cables with a cross-section of will have sufficient short-circuit withstand capacity for both assumed insulation materials. On the other hand, when even the shortest experimentally determined delay time is included in the total short-circuit clearing time from the moment of its initiation (), it becomes necessary to increase the cross-section of the cable with PVC insulation to the next value in the standard series () in order to meet the short-circuit withstand condition. Furthermore, when considering a mechanical breaking time of up to and again accounting for the minimum delay time , an increase in the conductor cross-section is required for both types of insulation. The average amount of thermal energy in the short-circuit scenario, due to the delay introduced by the protection-automation systems discussed in Section 2, is approximately higher compared to conventional protection systems, and in the variant it exceeds this value by more than for the shortest observed delay time .

Table 17.

The cable’s short-circuit capacity.

4. Discussion

The conducted simulation studies unequivocally demonstrate that network infrastructure load is a critical parameter affecting the operational dynamics of protection systems. The observed trend indicates that as the intensity of data transmission increases—determined by the number of streams and samples per cycle—a proportional increase in the relay’s response time occurs.

The key conclusions drawn from this research are as follows:

- Confirmation of a Causal Relationship: A direct, positive correlation between the degree of network load and the delay in generating a trip signal has been proven. The observed delay is a systemic consequence of increased network traffic rather than a result of the protection device’s operational instability.

- Practical Implications for System Optimization: The results suggest that the strategic management of data transmission parameters, particularly the number of samples per cycle, is an effective means of minimizing the operating time of protection systems. This can enhance the performance and reliability of protection systems in practical applications.

In the analyzed protection automation systems, transmission and data processing delays represent a critical factor determining the effectiveness and selectivity of protection schemes. The physical causes of these delays arise from several interrelated mechanisms. First, packet queuing phenomena and communication network congestion (so-called sampled values network congestion) cause temporary bottlenecks in data transmission between IED devices, leading to an increase in the overall signal propagation time [24,28]. Second, limited time synchronization precision in PTP (Precision Time Protocol) networks and the occurrence of clock drift between IED nodes can generate phase errors in communication, resulting in incorrect interpretation of event sequences [41]. Additionally, the response times of the actuating elements themselves—relays, contactors, and circuit breakers—are determined by their electromagnetic properties, particularly arc extinguishing speed and mechanical drive delays [42]. Reducing these delays requires a multi-layered approach. At the hardware infrastructure level, effective solutions include redundancy of communication components and the use of ring topologies with fast-switching mechanisms (e.g., HSR, PRP – High-availability Seamless Redundancy, Parallel Redundancy Protocol) [24,28]. Such solutions eliminate transmission downtime and enhance resilience to single-link failures. At the automation layer, the use of devices with improved temporal parameters is recommended—digital relays and vacuum circuit breakers with reduced actuation and arc-extinguishing times (approximately 20–40 ms instead of typical 60–80 ms) [42]. Another effective strategy involves implementing multi-level synchronization, combining the PTP standard with local time sources (GPS, IRIG-B), which minimizes synchronization errors in the event of network degradation [28,41]. Furthermore, adaptive algorithms in IEDs, leveraging predictive system behavior models, allow temporary communication delays to be compensated by estimating measurement values in real time [28]. As a result, the effective response time of protections can be shortened, and the thermal consequences of faults can be limited, which would otherwise risk exceeding the allowable energy in conductors and supply cables.

The data presented can serve as a valuable basis for the design and modernization of network infrastructure in power systems, as well as for the precise parameterization of protection devices to ensure maximum reliability and speed of operation. This mechanism arises directly from the critical characteristics of the Sampled Values (SV) protocol in IEC 61850 environments and from the way network switches handle high-priority packets. The key difference between increasing the number of streams and increasing the sampling frequency lies in the time density of packets and the resulting queuing delay. Increasing the number of SV streams (e.g., from two to four at 256 samples per cycle) increases the total number of packets in the network as well as the switch processor load. However, each individual SV packet (of the same size) maintains the same time interval between consecutive samples for a given Merging Unit (MU). In contrast, increasing the sampling frequency (e.g., from 80 to 256 samples per cycle) while keeping the number of streams constant has a much more drastic effect, as it shortens the time intervals between consecutive SV packets generated by the same MU. SV messages, which are essential for precise protection functions, must be transmitted in a faster sequence, leading to a sharp increase in the number of packets per unit time and significant traffic bursts on the communication links. High sampling frequency (256 samples/cycle) causes that, even though SV packets are assigned high priority (Quality of Service—QoS) according to IEC 61850, their high time density leads to accumulation in switch buffers (HYPERION 400), especially during signal convergence. Shortened intervals between SV packets increase the risk of queuing delay, as the switch cannot instantly process and forward such a large number of high-priority packets without introducing minimal delay. This queuing delay accumulates and is directly propagated to the critical TRIP signal generated by the relay, resulting in a noticeable and systematic increase in operating time () observed in the experiments. Therefore, sampling frequency is the dominant factor because it directly affects the rhythm and utilization of the switch’s temporal resources, forcing the system to process critical data within shorter time windows.

5. Conclusions

Based on the research conducted to analyze the relationship between digital network load and the response time of the protection system, the following conclusions were formulated. The study demonstrated a direct positive correlation between the degree of network infrastructure load and the trip time of the protection relay. The observed elongation in response time is a systemic consequence of intensified network traffic rather than a result of the operational instability of the protection devices themselves. The analysis determined that the key factor influencing the delay is the increase in the sampling frequency of the data streams, which has a more significant impact than merely increasing the number of streams. The obtained results provide empirical evidence that data transmission parameterization is a critical element in the optimization process of protection automation systems. This implies the necessity of strategic management of network traffic characteristics, particularly the sampling frequency, to minimize delays and ensure maximum reliability and speed of operation for modern digital solutions in the energy sector. Future research will be related to network traffic optimization, data aggregation, and the analysis of the impact of time synchronization quality on critical infrastructure in the field of protection automation.

Protection automation systems based on centralized protection architectures significantly enhance the operational effectiveness and coordination of actuating devices under fault conditions. Nevertheless, the presence of additional control and intermediary components introduces an impact on the response times of the actuating elements within the protection automation system. In this study, detailed investigations were carried out to determine the range of response delays that may occur for selected configurations of protection automation schemes. In extreme scenarios, under conditions of high network traffic, the observed delay times reached up to 64 ms (in several extreme cases, whose analyses were not included in the paper, the delay reached up to 100 ms). The analysis demonstrates how these time delays contribute to an extension of fault duration, illustrated by the case of a single-phase-to-ground fault for various values and () ratios of the fault loop parameters. For the longest delay times obtained in laboratory measurements, the thermal energy released during the fault was found to be 45% higher compared to conventional protection arrangements. In critical cases, such excess thermal energy may exceed the short-circuit withstand capacity of cables dimensioned without accounting for the identified delays inherent to advanced protection automation systems. Therefore, when implementing such solutions, it is essential to consider the expected delay times during the selection of conductors and associated protection devices.

This study, based on detailed hardware-in-the-loop simulations, provides empirical and quantitative evidence of fundamental importance for the design and optimization of digital protection systems compliant with the IEC 61850 standard. Our main, original contribution is the quantification of the consequences of network delays, extending beyond a mere description of correlation.

We conducted a quantitative analysis of the tripping time of the protection system across the full spectrum of digital network load in laboratory conditions. Our contribution is the direct, empirical demonstration that an increase in sampling frequency (e.g., from 80 to 256 samples/cycle) has a dominant and more significant impact on prolonging the trip time than simply increasing the number of data streams (SV). This determination, supported by laboratory measurements, establishes a critical criterion for optimizing communication parameters and refutes the simple intuition that delay is solely a function of the total number of streams. The results provide quantitative confirmation that the delay is a systemic consequence of increased traffic (queuing delay), rather than protection device instability.

This work introduces a direct link between the measured network delay and its physical consequences for the power installation, which constitutes the most important engineering contribution. The analysis demonstrated that the additional trip time () introduced by digital automation systems leads to a significant increase in the thermal energy () released in cables during a short-circuit event. In critical cases, for the longest measured delays (≈64), the thermal energy is 45% higher compared to conventional protection schemes.

The most practical contribution is the establishment of a new design criterion. We demonstrated that accounting for the identified delays is essential to meet the cable’s short-circuit withstand condition. Our analysis clearly shows that even the shortest experimentally determined delay may necessitate oversizing the cable cross-section (e.g., from to ) to ensure safe and reliable system operation. This constitutes a direct and original recommendation for engineers designing digital substations.

The conducted research demonstrates that the communication delay introduced by modern digital protection and automation systems—particularly those relying on IEC 61850 process-bus architectures—can significantly extend the total fault-clearing time. Under high sampled-values (SV) network load conditions, the experimentally observed delay exceeded 60 ms, which, when combined with mechanical breaking times of 70–120 ms, may lead to total clearing times exceeding 120 ms. This temporal extension directly increases the Joule integral of the fault current, with simulations showing a 35–55% rise in released thermal energy () compared to conventional protection systems that do not rely on communication-based trip coordination. From a thermal and mechanical standpoint, these additional energy releases can exceed the short-circuit withstand limits of commonly used 0.4 kV distribution cables, especially those with PVC insulation. As a result, even marginal latency growth—caused by network congestion, synchronization inaccuracies (PTP/IEEE 1588v2), or processing jitter in IEDs—may require upsizing conductor cross-sections (e.g., from to ) to maintain compliance with short-circuit thermal endurance criteria defined in IEC 60949 and IEC 60364. For practical engineering applications, the findings highlight the need to explicitly include communication-induced delays in the design and coordination of digital protection schemes. This involves incorporating deterministic latency budgets and worst-case jitter margins in protection coordination studies; implementing redundant network topologies (PRP/HSR) to limit packet loss and reduce queuing delay; using high-precision time synchronization (PTP grandmasters with sub-microsecond accuracy) to minimize timestamp discrepancies; selecting IEDs and circuit breakers with low-latency tripping mechanisms (faster arc-extinguishing technology); and performing hardware-in-the-loop validation of end-to-end trip times before system commissioning. Ultimately, the presented results underline that digital protection reliability cannot be assessed solely through algorithmic or logical coordination. Instead, it requires a holistic design approach integrating communication network performance, time synchronization accuracy, and the physical characteristics of switching and conductor elements. Neglecting these aspects in the design phase can lead to underestimation of fault energy release, potential overheating, and long-term degradation of cable insulation—particularly in industrial power distribution systems, where process continuity and system availability are critical.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ł.S. and B.R.; Methodology, Ł.S. and B.R.; Software, Ł.S., B.R. and K.N.; Validation, Ł.S. and B.R.; Formal analysis, Ł.S.; Investigation, Ł.S., B.R. and M.G.; Resources, B.R.; Data curation, Ł.S.; Writing—original draft, Ł.S. and B.R.; Writing—review & editing, Ł.S. and B.R.; Visualization, Ł.S., B.R. and M.G.; Supervision, Ł.S. and K.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Krzysztof Nowacki was employed by the BitStream S.A. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Ağin, A.; Demirören, A.; Usta, O. A Novel Approach for Power System Protection Simulation via the IEC 61850 Protocol. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 107656–107669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC/TR 61850-1; Communication Networks and Systems for Power Utility Automation. Part 1: Introduction and Overview; IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Ali, N.; Eissa, M. Accelerating the protection schemes through IEC 61850 protocols. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2018, 102, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, J.; Oliván, M.A. Lossless and Stateless Compression of IEC 61850 Sampled Values Flows. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2024, 39, 1314–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, M.; Hussain, S.; Ali, I.; Almutairi, A. Performance Evaluation of IEC 61850 GOOSE Based Inter-Substation Communication for Accelerated Distance Protection Scheme. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2018, 12, 4468–4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, A.; Fernandes, R.; Batista, A.; Silva, J. Characterization of Substation Process Bus Network Delays. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2017, 13, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Patel, M.; Schweitzer, E. Understanding the Impacts of Time Synchronization and Network Issues on Protection in Digital Secondary Systems. In Proceedings of the PAC World Global Conference, Virtually, 31 August–1 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alcaraz, C.; Lopez, J.; Zhou, C. Vulnerability and Impact Analysis of the IEC 61850 GOOSE Protocol in Smart Grid Systems. Sensors 2021, 21, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE 1588-2008; IEEE Standard for a Precision Clock Synchronization Protocol for Networked Measurement and Control Systems. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019.

- Ingram, D.M.E.; Schaub, P.; Campbell, D.A.; Taylor, R.R. Performance Analysis of PTP Components for IEC 61850 Process Bus Applications. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2013, 62, 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotnikov, I.V.; Ponomarev, S.V. On the Use of Quality Flags for Digital Transformers in the Sampled Values Protocol IEC 61850. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 25th International Conference of Young Professionals in Electron Devices and Materials (EDM), Altai, Russia, 28 June–2 July 2024; pp. 1410–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga, A.; Muguira, L.; Jiménez, J.; Gárate, J.I.; Cuéllar, A.A. A Survey on IEEE 1588 Implementation for RISC-V Low-Power Embedded Devices. Electronics 2024, 13, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldhauser, S.; Jaeger, B.; Helm, M. Time Synchronization in Time-Sensitive Networking. Network 2020, 51, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingyu, H.; Peter, C. Performance Evaluation of IEEE 1588 for Precision Timing in IEC 61850 Substations. In Proceedings of the Study Committee B5 Colloquium, Tromsø, Norway, 24–28 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Yang, R.; Liu, S.; He, Q. Design and Implementation of Best Master Clock Selection Algorithm Based on FPGA. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Industrial IoT, Big Data and Supply Chain (IIoTBDSC), Beijing, China, 23–25 September 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 62439-3:2021; Industrial Communication Networks—High Availability Automation Networks—Part 3: Parallel Redundancy Protocol (PRP) and High-Availability Seamless Redundancy (HSR). International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Rubio, S.; Bogarra, S.; Nunes, M.; Gomez, X. Smart Grid Protection, Automation and Control: Challenges and Opportunities. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, H.; Chen, L. Modeling and Performance Analysis of Data Flow for HSR and PRP under Fault Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Portland, OR, USA, 5–10 August 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobar-Rosero, O.A. Digital Substations: Optimization Opportunities from Communication Architectures. Sci 2025, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tightiz, L.; Yoo, J. Towards Latency Bypass and Scalability Maintain in Digital Substation Communication Domain with IEC 62439-3 Based Network Architecture. Sensors 2022, 22, 4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardino, R.C.; Martins, C.M.; Pereira, P.S.; Lourenço, G.E.; Junior, P.S.P. Link redundancy in the process bus according to IEC 61850 ED.2: Experience with RSTP, PRP and HSR protocols. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Developments in Power System Protection (DPSP 2022), Newcastle, UK, 7–10 March 2022; pp. 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Xia, Y.; Yan, Z.; Gao, H.; Qiu, D.; Guerrero, J.M.; Li, Z. Coordinated operation of multi-energy microgrids considering green hydrogen and congestion management via a safe policy learning approach. Appl. Energy 2025, 401, 126611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]