Abstract

Electric vehicles (EVs) are experiencing rapid global adoption driven by environmental concerns and fuel security. This article presents a new dual-source converter based on a hybrid modular multilevel configuration (DCHMMC) designed for optimal cell utilisation in EV battery systems. Contrary to conventional converters that can either charge or discharge the cells using a single source, thereby leaving several cells/modules (Ms) idle during each time step, the proposed converter enables the integration of two sources that can utilise the cells simultaneously. This dual source feature minimises idle cells/Ms, enhances energy efficiency, and supports flexible bidirectional power flow. The proposed converter operates in three distinct modes. The first involves dual-source charging for fast charging and improved vehicle availability. The second involves one source charging while the other discharges for dynamic operation. Finally, the last involves dual-source discharging for maximum power delivery and support vehicle-to-grid (V2G) operation. The simulation results demonstrated smooth multilevel sinusoidal output voltages (Vout_a and Vout_b), each with a peak of 350 V, generated simultaneously using 132 cells (six cells per M, 22 Ms). The total harmonic distortion (THD) values for Vout_a and Vout_b were 0.42% and 2.25%, respectively, confirming the high-quality performance. Furthermore, only 0–36 cells and 0–6 Ms were idle during operation, showing improved cell utilisation.

1. Introduction

Electric vehicles (EVs) are rapidly gaining global popularity due to environmental concerns and fuel security. The majority of greenhouse gas emissions from transportation come from fossil fuel combustion in vehicles, trains, ships, and airplanes. Zero/low-emission vehicles are therefore vital to reduce transportation emissions and improve sustainability. Since electric power systems are widely available, EVs represent one of the most effective solutions for reducing pollutants. Besides serving as a sustainable transportation option, EVs can also function as mobile energy storage units through vehicle-to-grid (V2G) or Grid-to-Vehicle (G2V) technology, thereby supporting grid stability and renewable energy integration [1]. At the heart of these capabilities lie power electronic converters (PECs), which play a vital role in enabling efficient charging, discharging, and bidirectional power flow in EV systems [2].

Although battery technology and EV driving ranges continue to improve, innovative charging strategies and converter topologies remain critical research areas. For instance, EV charging can be coordinated with smart grid systems to provide ancillary services, benefiting both utilities and mobility operators [3]. PECs are widely deployed across various applications, including EVs [4], uninterruptible power supplies (UPSs) [5], renewable energy systems such as photovoltaic (PV) arrays [6], fuel cells, and wind energy conversion systems [7]. Depending on their function, PECs can be categorised into DC–DC, AC–DC, DC–AC, and AC–AC converters, each of which plays an essential role in EV charging performance [8,9].

Over the past decades, multilevel inverter (MLI) topologies have attracted increasing attention in EV applications due to their ability to overcome the limitations of conventional two-level inverters [10]. Compared to two-level structures, MLIs provide lower current and voltage total harmonic distortion (THD), reduced electromagnetic interference and common-mode voltage, higher efficiency, and reduced device voltage stress, making them highly suitable for EV applications [11]. Several MLI topologies have been explored for EVs, including neutral point clamped (NPC) [12], active neutral point clamped (ANPC) [13], flying capacitor (FC) [14], nested neutral point clamped (NNPC) [15], and T-type inverters [16]. Each topology offers unique benefits; for instance, NPC and ANPC reduce device stress, FC inverters provide inherent voltage balancing, and NNPC minimises the number of diodes and capacitors, lowering system size and cost. T-type inverters are particularly attractive for compact EV systems due to their low losses and reduced component count, though they require high-voltage switches. Despite these advantages, challenges such as capacitor voltage balancing, increased complexity, and reduced reliability due to the higher number of switching devices remain open research issues for EV systems [10].

Among the various MLI topologies, the modular multilevel converter (MMC) and the cascaded H-bridge (CHB) have been widely investigated for EV traction drives due to their modularity, scalability, and low harmonic distortion [17,18,19]. In [20], an MMC inverter was introduced in which each battery cell was directly connected to a submodule, inherently achieving state-of-charge (SoC) balancing without the need for a separate battery management system (BMS). Similarly, in [21], an MMC control strategy was proposed to enable low-frequency output currents with reduced capacitor voltage ripple, which is particularly suitable for variable-frequency traction applications. For CHB inverters, asymmetrical structures, such as the 23-level ACHB in [22], achieved high voltage levels using a single DC source and a high-frequency transformer, although challenges related to isolated supplies and idle cells/modules persisted.

Lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries dominate EV energy storage due to their high energy density, compact size, and favourable electrochemical properties. However, individual cells provide low voltage, requiring series/parallel connections to meet EVs’ high voltage demands. This arrangement inevitably introduces cell imbalance due to manufacturing inconsistencies, thermal effects, aging, and non-uniform self-discharge rates [23]. Imbalance leads to issues such as overcharging, undercharging (not fully charged), incomplete discharging (not fully discharged), and deep discharging, and thus a reduced battery lifetime, as well as safety risks, including overheating and thermal runaway [24]. Effective balancing strategies are therefore critical. While passive and active balancing circuits within a BMS have been proposed, they add cost, complexity, and energy losses. It is worth noting that the proposed converter is designed to fully control and monitor each individual cell by integrating each cell with L-bridge switches and each module (M) with two H-bridge switches connected in parallel, as detailed in Section 2. In order to generate a sinusoidal multilevel output voltage (Vout), a different number of cells are activated during each time step (Ts) based on a control strategy that considers their SoC. Thus, this architecture allows inherent adaptability for implementing an active SoC balancing strategy in future work. Specifically, the SoC balancing can be achieved by controlling the duty cycle of each cell according to its SoC level, referred to as the duty-cycle balancing method, which is well-suited for the proposed structure [25]. Accordingly, while the detailed balancing control algorithm will be developed in future work, this article focuses on introducing the new converter circuit and highlighting its key contributions.

In conventional cascaded MMC/CHB-based EV battery packs (in this configuration, each cell or M is integrated into an H-bridge, as illustrated in Figure 1), two categories of unutilised cells/Ms can be distinguished: redundant cells/Ms and idle cells/Ms. Redundant cells/Ms are surplus cells/Ms beyond the number required to generate the peak voltage and are primarily introduced for reliability, either operating in an active scheme or remaining unused in a passive scheme until a fault occurs. Idle cells/Ms, by contrast, are those temporarily unutilised during each Ts because the number of active cells/Ms changes with the instantaneous output level [25,26,27]. The fluctuation in the number of idle cells/Ms occurs due to the operation principle of the cascaded MMC/CHB used to generate Vout. For instance, if 50 Ms are needed for the peak voltage but only 35 are active at a certain level, the remaining 15 Ms are idle (i.e., idle Ms = Z − utilised Ms, where Z refers to the total number of Ms included in the system). In a single-phase cascaded MMC/CHB configuration for EVs, this issue is particularly evident, as the number of idle Ms varies continuously from zero up to the peak requirement and back down to zero within each cycle. Furthermore, conventional multilevel converters can only interface with a single source at a time. Thus, all cells or Ms are either charging or discharging. This single-source limitation, combined with the presence of idle cells/Ms, leads to suboptimal cell utilisation, reduced system efficiency, and limited operational flexibility. The main scientific problem addressed in this article is how to design a converter architecture that can overcome these restrictions by enabling simultaneous dual-source integration, dynamic energy management, and optimal utilisation of all cells/Ms. To address these challenges, this article proposes a dual-source integrated MMC/CHB converter designed to minimise idle cells/Ms and ensure optimal cell utilisation through three distinct operation modes. First, it employs simultaneous charging of cells from both sources, thereby reducing charging time and improving vehicle availability. Second, one source charges the cells/Ms while the other discharges them for dynamic operation. Finally, both sources discharge the cells simultaneously to maximise power delivery and support V2G operation. By fully exploiting idle cells/Ms and integrating dual-source operation, the proposed converter addresses the key limitations of conventional MMC and CHB structures, while enhancing charging flexibility, efficiency, and reliability, making it well-suited for next-generation EV applications.

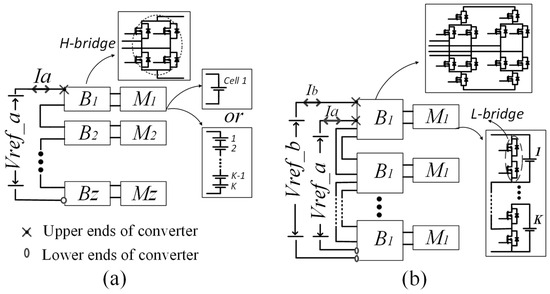

Figure 1.

A comparative schematic of multilevel converter topologies. (a) The conventional converters. (b) The proposed converter.

Figure 1 presents a comparative overview of the proposed converter and conventional multilevel converter topologies. Throughout this article, the term conventional converter refers to a multilevel converter structure that cannot divide its cells or Ms into more than one group/branch during any Ts. The comparison highlights the differences in schematic structure, total number of required switches, and the capability to split the cells/Ms into two independent groups/branches that can simultaneously connect to two distinct reference sources (Vref_a and Vref_b). Acronyms are defined in Table 1. A step-by-step graphical representation of the proposed DCHMMC operation and control sequence is presented in Figure 2. The detailed structural configuration of the proposed converter is shown separately in Figure 3. Table 2 provides a comparative evaluation between the proposed converter and some existing topologies, focusing on critical performance criteria. The comparison includes efficiency, reliability, flexibility, control complexity, and cost. Efficiency and reliability are evaluated based on the total switch count, cost, and the ability to monitor and control individual cells, as well as the capability to produce the required Vout during peak demand or in the event of cell/M failures. Flexibility is evaluated according to the converter’s ability to minimise idle cells/Ms during each Ts and to enable simultaneous charging/discharging of cells/Ms from more than one source. Control complexity is determined by the number of required control signals and sensors. In the previous literature, converter comparisons have typically been conducted using a qualitative grading method, assigning ranks such as excellent/high, good/medium, and poor/low for evaluation parameters including efficiency, control complexity, size, and cost [28]. Furthermore, to ensure a fair and meaningful quantitative comparison, all converter topologies compared in Table 2 were designed under unified conditions, where K represents the number of cells per M, Z denotes the number of Ms in the converter, and N (=ZK) indicates the total number of cells.

Table 1.

Nomenclature.

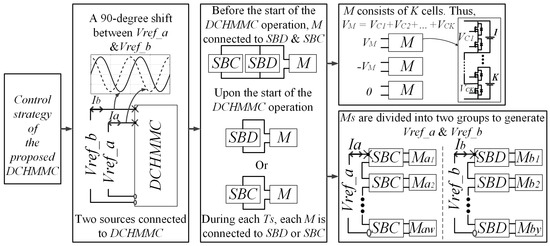

Figure 2.

A step-by-step graphical representation of the proposed DCHMMC operation and control sequence.

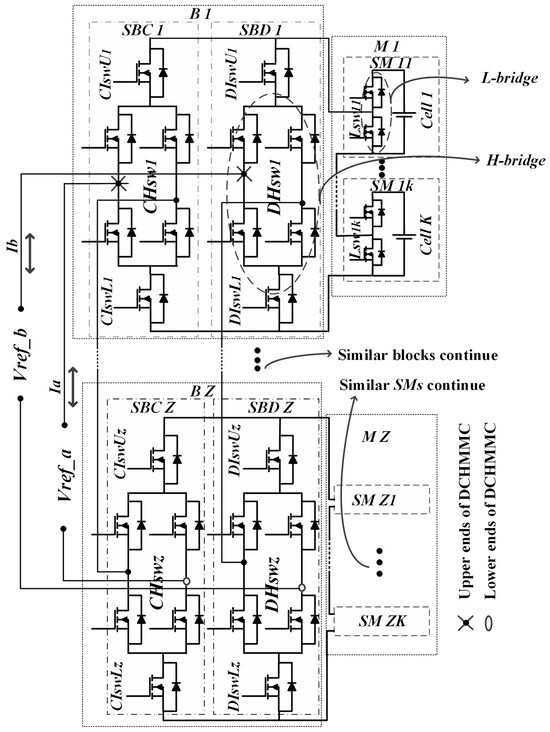

Figure 3.

The proposed converter configuration of a DCHMMC for EV applications.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of the proposed and existing converters.

The circuit in [29] integrates each cell with an L-bridge (two switches), and the entire pack of cells with a single H-bridge (four switches). In [30], the main circuit is constructed using a hierarchical architecture where each cell is integrated into an L-bridge and each pack of cells is integrated into an H-bridge. To achieve SoC balancing among the cells, a hierarchical balancing strategy is employed. This is implemented with dual relays assigned to each cell and to each pack of cells for selective reconfiguration. Furthermore, DC–DC converters are utilised at two levels: one DC–DC converter for each pack of cells to transfer energy within the same pack of cells, and an additional DC–DC converter across all the cells/Ms to transfer energy among Ms. Accordingly, the overall switch counts used for the circuits in [29] and [30] are given by 2KZ + 4 and 2KZ + 4Z, respectively. While the circuit in [29] minimises the overall number of used switches by using a single H-bridge for the entire pack, this construction choice comes at the cost of significantly reduced system efficiency and reliability. On the other hand, the circuit in [30] relies on a substantial number of additional components, specifically 2KZ relays and Z + 1 DC–DC converters. This high component count adversely affects the system’s efficiency and reliability, and increases its control complexity. In contrast, the number of switches used in the proposed converter can be given as 2KZ + 10Z without additional components. It is worth noting that compared to the conventional multilevel converters that integrate each cell with an H-bridge in a hierarchical architecture to fully control and monitor each cell (with the number of switches given as 4KZ + 4Z) [31], the proposed converter significantly reduces the total switch count while maintaining independent monitoring and control.

Thermal management is a critical consideration in high-power converters, as excessive heat generated by semiconductor devices can lead to reduced efficiency, performance degradation, and premature failure. In the proposed converter, the distributed switching structure inherently mitigates localised thermal stress by spreading power losses among multiple switches and Ms, which facilitates more uniform temperature distribution and enhances converter reliability. Similar to multi-switch boost converters reported in the literature [32], parallel or modular switch configurations effectively lower the current stress on individual devices and improve thermal stability. This article is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the methodology and operating principle of the proposed converter. Section 3 shows the MATLAB R2022b-based simulation results. Section 4 concludes the article with a summary of the key findings.

2. Methodology

The research methodology followed in this study is summarised as follows. First, the limitations of conventional converters, such as the presence of idle cells/Ms and their inability to integrate multiple sources to either charge or discharge the cells/Ms simultaneously, were identified through an extensive literature review. Then, a new dual cascaded hybrid modular multilevel converter (DCHMMC) was developed to address these issues by enabling two independent sources to operate simultaneously for improved cell utilisation. Following the design stage, a detailed description of the proposed converter configuration and its operating principle was presented, including the mechanism of cell/M distribution into two branches during each Ts. Mathematical modelling was carried out to define voltage relationships and determine the minimum number of active cells during each Ts. The proposed topology was then implemented and validated through MATLAB/Simulink R2022b simulations under two case studies. Finally, the performance of the proposed converter was compared with conventional topologies (as presented in Table 2) in terms of efficiency, reliability, flexibility, control complexity, and cost.

Figure 2 provides an overview of the complete system operation, linking all key processes that are illustrated in detail throughout the methodology section, as well as the control strategy presented at the beginning of the Results Section. It begins with the generation of two reference voltages phase-shifted by 90 degrees (dual sources), followed by their integration into the proposed DCHMMC structure (Figure 3). The diagram then outlines the converter operation before and during switching, where each M connects to either SBC or SBD during each Ts (Figure 4). Subsequently, the output voltage across each M is determined (Figure 5), leading to the distribution of Ms into two groups responsible for generating Vref_a and Vref_b (Figure 6). Figure 7 shows the generation of two reference voltages phase-shifted by 90 degrees. All these processes are governed by the control strategy presented in Figure 8, ensuring coordinated operation of the proposed converter.

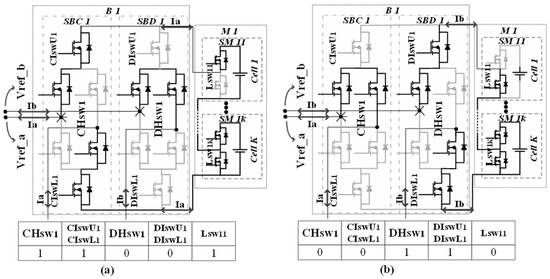

Figure 4.

Two scenarios demonstrating M1 integration with different reference sources during each Ts: (a) M1 connected to Vref_a, (b) M1 connected to Vref_b.

Figure 5.

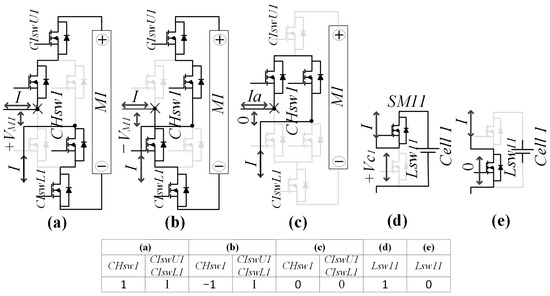

Effect of M1-related switch statuses on the output voltages of M1 and SM11. The output voltage of M1 is (a) +VM1, (b) −VM1, and (c) 0 when CHsw1 is set to 1, −1, and 0, respectively. The output voltage of SM11 is (d) +VC1 and (e) 0 when Lsw11 is set to 1 and 0, respectively.

Figure 6.

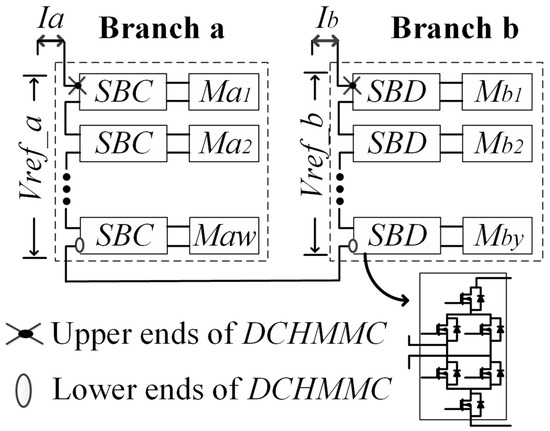

Cells/Ms’ distribution into two branches/phases during each Ts interval of the system operation.

Figure 7.

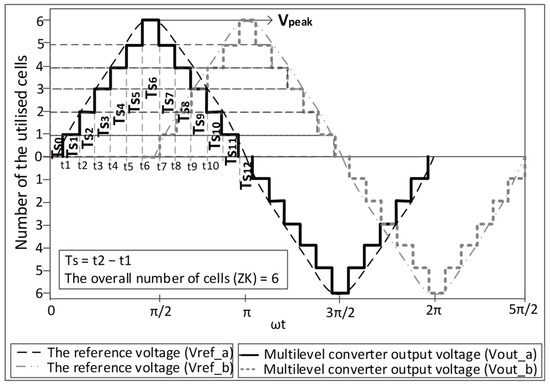

A 90-degree phase shift between two sinusoidal multilevel waveform voltages generated by the proposed converter simultaneously.

Figure 8.

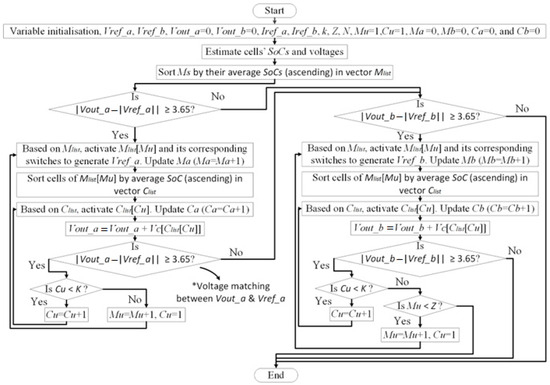

The algorithm of the control strategy for the proposed converter to generate Vref_a and Vref_b simultaneously.

2.1. Description of the Proposed Converter

Figure 3 presents the proposed converter for serially connected Li-ion cells in the battery pack for EV applications. It consists of blocks (Bs), sub-blocks (SBs), modules (Ms), and sub-modules (SMs), which are integrated in series and parallel to create the whole proposed converter. Each SM consists of integrating an individual cell into the L-bridge MOSFET switches. Each specific number of SMs is integrated in series, forming what is called the M. The M is integrated in parallel into the B. Since the M has two ports, the upper part of the M is integrated into the upper part of the B (the upper terminal of the SB), while the lower part of the M is integrated into the lower part of the B (the lower terminal of the SB). The B consists of two typical SBs integrated in parallel, forming what are called sub-block charging (SBC) and sub-block discharging (SBD) (the C and D letters at the end of SBC and SBD refer to the charging and discharging processes, respectively). SBC and SBD are integrated into the next SBC and SBD, which are included in the next M, consisting of what will be called a dual cascaded hybrid modular multilevel converter (DCHMMC). The end of each DCHMMC can be connected to a source (i.e., Vref_a and Vref_b), as will be explained in the next Sub-Section. In other words, DCHMMC can be integrated with a dual-source system that operates simultaneously.

Each SBC or SBD consists of an H-bridge integrated into two additional MOSFET switches, which are located on the upper and lower sides of the H-bridge. These additional MOSFET switches are used to isolate the charging and discharging currents, as explained in the Operation Principle Sub-Section. The K letter refers to the number of cells/SMs utilised in the M, while the Z letter refers to the number of modules/blocks (Ms/Bs) utilised in the whole system. Note that the number of SMs in each M is constant throughout the DCHMMC. Thus, the overall number of cells utilised in the DCHMMC is equal to N (N = number of M (Z) × number of SM (K)). The switches used in the L-bridges of the M, the H-bridges of the B, the upper isolated switch of the B, and the lower isolated switch of the B are referred to as Lsw(1~z)(1~k), CHsw(1~z) or DHsw(1~z), CIswU(1~z) or DIswU(1~z), and CIswL(1~z) or DIswL(1~z), respectively. The C, D, U, and L letters are added to the name of the switches used in the B (i.e., CIswU or DIswL) to refer to the charging process, the discharging process, the upper part of the B, and the lower part of the B, respectively.

Each of Vref_a and Vref_b can be operated as a source or a load, and thus, three scenarios can be created. First, both Vref_a and Vref_b can be operated as two independent sources to charge the cells simultaneously. Second, both Vref_a and Vref_b can be operated as two independent loads to discharge the cells simultaneously. Third, simultaneously, Vref_a can be operated as a source to charge the cells, while Vref_b can be operated as a load to discharge the cells. It is worth noting that during the DCHMMC operation, a 90-degree phase shift will be found between Vref_a and Vref_b, as illustrated in Section 2.2.

2.2. Operating Principle and Cell/Module Distribution into Two Branches

The basic concept of the proposed DCHMMC is to integrate each M into its two parallel H-bridges and their isolation switches (i.e., SBC and SBD). Therefore, all cells will participate in generating the two reference voltages (Vref_a and Vref_b). Note that, during each Ts and by controlling the corresponding switches of both the M and B (i.e., for M1, CIswU1, CIswL1, DIswU1, and DIswL1 will be controlled), each M can be only utilised to produce the chosen reference voltage (Vref_a or Vref_b), as shown in Figure 4. Figure 4 illustrates, during a particular Ts, the two scenarios of connecting M1 into either Vref_a as shown in Figure 4a, or Vref_b as shown in Figure 4b. In Figure 4 and Figure 5, the grey-coloured lines indicate paths where no current (Ia or Ib) flows during the corresponding operation state.

In Figure 4, before the start of the DCHMMC operation, M1 is directly connected to Vref_a and Vref_b through SBC1 and SBD1. However, M1 is isolated from Vref_b once it is activated to be in Vref_a (Figure 4a), and vice versa (Figure 4b). Note that during the same Ts, SBC and SBD of the same B (i.e., SBC1 and SBD1 of B1) cannot be activated together; however, both can be deactivated in order not to use the corresponding M (i.e., M1). In addition, the number of utilised cells in each M is dependent on its L-bridges switches’ statuses, as illustrated in Figure 4a,b. The switching statuses are either ON (1 or −1) or OFF (0). In Figure 4a, the L-bridge/SM (Lsw11) of cell 1 is ON (i.e., cell 1 is utilised), while it is OFF in Figure 4b (i.e., cell 1 is not utilised). As a result, the DCHMMC shows complete control of the number of utilised cells or Ms. It is worth noting that in Figure 4a, the current a (Ia) can access the cells in M1, while the current b (Ib) can only pass through the H-bridge of SBD1 without accessing the cells in M1 to continue its cycle/loop. In comparison, the opposite occurs in Figure 4b (i.e., Ib can only access the cells in M1).

Figure 5 illustrates an example of all possible scenarios for the output voltage value of M1 and its related cells/SMs. Only CHsw1 is chosen to present in Figure 5 due to the similarity of its operation principle with DHsw1. The output voltage value of M1 (VM1) can be either positive (+VM1), negative (−VM1), or zero (0) based on the statuses of its related switches in SBC1 (CHsw1), as illustrated in Figure 5a, Figure 5b, and Figure 5c, respectively. For positive, negative, and zero values, their related CHsw1 is ON (1), ON (−1), and OFF (0), respectively. At the same time, the magnitude value of VM1 depends on the number of activated cells/SMs within M1 (i.e., it is equal to the summation of its activated cells/SMs). The output voltage value of SM1 (VC1) can be positive and equal to the cell’s voltage (+VC1) when its related L-bridge (Lsw11) is ON (1), as illustrated in Figure 5d, or zero (0) when its related L-bridge (Lsw11) is OFF (0), as illustrated in Figure 5e. Note that cell 1 of M1 is chosen to be presented in Figure 5d,e.

The fundamental idea of the proposed converter is to distribute the cells/Ms during each Ts into two groups/branches using SBC and SBD. The output voltages (Vout_a and Vout_b) of the two branches must be as close as possible to the reference voltages (i.e., Vout_a = Vref_a and Vout_b = Vref_b), as shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7. Since Vref_a and Vref_b are sinusoidal multilevel waveforms, as shown in Figure 7, each duty cycle from 0 to 2π is split into numerous Ts, where certain levels of Vref_a and Vref_b are produced during each Ts. The Ts value is calculated based on Equation (1), which affects the voltage step values of Vref_a and Vref_b. For example, in Figure 7, the voltage step is equal to a single cell voltage at Ts equals t2 − t1. Accordingly, if Ts becomes equal to t3 − t1, then the voltage step will be doubled (i.e., equal to the sum of two cell voltages). At the beginning of each Ts (i.e., t1, t2, t3, and so on), the number of cells/Ms needed to generate the desired level of Vref_a and Vref_b is determined according to the designed control strategy. It is worth noting that the desired value of Ts is calculated before the system begins operation and remains constant throughout the operation. In addition, Equation (1) is designed to ensure that Vout matches Vref, which will occur when the value of the voltage step is very close to a single cell voltage (Vc). In Equation (1), Vc is a cell cut-off voltage (the lowest possible voltage), which is selected according to the cell manufacturer’s datasheet. ω0 = 2πf, where f is the system reference frequency. Vpeak is a peak reference voltage.

In conventional converters, cells/Ms cannot be split into more than one group/branch during any Ts. On the contrary, the proposed converter is able to divide the cells/Ms into two groups/branches during each Ts, which is the main contribution of the proposed converter. This contribution offers the proposed converter greater flexibility compared to conventional converters, enabling it to function as two systems simultaneously. Splitting the Ms into two branches can be achieved by controlling their corresponding switches, as illustrated in Figure 4.

To avoid the overlapping of two-system currents, complete isolation among these two branches must be achieved prior to the utilisation of their corresponding Ms. All the cells/Ms participate in producing each level of Vref_a and Vref_b during each Ts. However, there is no specific cell or M for a particular phase/branch. It is worth noting that during each Ts, each cell/M can only be utilised in a single branch. In Figure 6, each branch consists of a single cascaded hybrid modular multilevel converter (CHMMC). The first branch is from Ma1 to Maw, whereas the second branch is from Mb1 to Mby. These branches are utilised to produce Vref_a and Vref_b, respectively.

Note that a 90-degree phase shift exists between Vref_a and Vref_b, and thus, the values of Vref_a and Vref_b change synchronously with each other, as shown in Figure 7. Consequently, the number of cells/Ms activated in each branch varies with time according to its corresponding Vref value. The terms w and y are the number of the Ms activated to produce Vref_a and Vref_b, respectively, during each Ts. Accordingly, the summation of w and y must not exceed the total number of Ms (Z). A 90-degree phase shift is chosen to be included between the two phases to maximise the difference in the number of required cells/Ms to generate each phase. For example, during Ts7 in Figure 7 (where the two phases are 90-degree shifted), Vref_a has the highest voltage value (Vpeak), while Vref_b has the lowest voltage value (zero voltage). Additionally, at Ts8, Vref_a begins to decrease while Vref_b starts to increase. Thus, at any given time, the overall number of the required cells/Ms (w + y) to produce Vref_a and Vref_b will not exceed the total number of cells/Ms (Z). Table 3 illustrates an example of the number of required cells to produce Vref_a and Vref_b in Figure 7 during a quarter of the duty cycle (Ts7 to Ts15). It is worth noting that during levels 5 and 6 of Figure 7, the voltage increasing/decreasing speed is less than the voltage increasing/decreasing speed during levels 1 to 4 (for example, during Ts9, Vref_a is in level 5 and therefore reduced by one step voltage, while Vref_b is in level 2 and hence increased by two step voltages). Accordingly, one-third of redundant cells/Ms must be included in the system to generate both references smoothly. For example, 6 cells are required to generate the peak voltage of Vref_a. Thus, 8 cells (=6 + 2 (one-third)) are necessary to generate Vref_a and Vref_b simultaneously.

Table 3.

A comparison of the number of utilised cells to produce Vref_a and Vref_b during the quarter of the duty cycle (Ts7–Ts15) in Figure 7.

In Figure 7 and Table 3, the total number of used cells is 8 (N = 8). However, 6 cells are used to generate the peak voltage of Vref_a or Vref_b. Vref_b starts operating after being shifted by 90 degrees from Vref_a (at Ts7). Thus, the comparison in Table 3 is performed from Ts7 to Ts15 for a quarter of the duty cycle, where the values are repeated every quarter of the duty cycle. The number of utilised cells to produce Vref_a (branch a) ranged from 6 to 0 cells, whereas it ranged from 0 to 6 cells for producing Vref_b (branch b) during each quarter of the duty cycle, as shown in Figure 7 and Table 3. However, during Ts8, Vref_a used 6 cells, while Vref_b used 1 cell, which increases the overall number of used cells to 7 cells. The highest total number of required cells will occur during Ts10, Ts11, and Ts12, with a total of 8 cells. Accordingly, during any Ts, the overall number of required cells to produce both Vref_a and Vref_b ranges from 6 to 8 cells, which is less than or equal to N. It is worth noting that in Figure 7 and Table 3, cells without Ms are used for better understanding. However, Ms are recommended to be utilised in the proposed converter for greater benefits (i.e., to reduce the number of switches used). Thus, when Ms are used, the M is considered utilised even if only one cell within the M is employed (i.e., a specific M cannot be used to produce Vref_a and Vref_b simultaneously). In addition, during Ts11, the converter is activated equally in all cells between branch a and branch b (i.e., redundant Ms are required). Accordingly, the authors recommend to ensure safe operation by including redundant cells/Ms for at least one-third of the total required cells/Ms to generate the highest reference voltage (Vref_a or Vref_b).

3. Simulation Results of the Proposed Converter

To validate the performance of the proposed converter (see Figure 3), a simulation model was built using the MATLAB Simulink software (R2022b). Table 4 provides a summary of the fundamental parameters of the simulation model. The simulation model parameters are designed to be as closely aligned as possible with the real system. The algorithm of the control strategy used in the simulation model is presented in Figure 8. The numbers of cells utilised to generate Vref_a and Vref_b are denoted as Ca and Cb, respectively, while the numbers of Ms utilised to generate Vref_a and Vref_b are represented by Ma and Mb, respectively. The remaining Ms are therefore Z-Ma-Mb, and the remaining cells are N-ZK. The simulation model employs a basic Li-ion cell configuration, where each cell comprises an internal voltage source (Vint) and an internal resistance (Rint) [33]. Consequently, the terminal cell voltage (VC) is calculated using Equation (2), exhibiting slight variations during charging and discharging due to the effect of Rint. The SoC of each cell is estimated using the Coulomb counting method, formulated based on Equation (3) [34]. Qmax, SoCo, and I(t) represent the cell’s maximum capacity, initial SoC, and charge/discharge current, respectively.

Table 4.

Essential simulation model parameters.

The Chevrolet Bolt EV system has been chosen. Each cell in the Chevrolet Bolt EV system has a nominal capacity of 58 Ah and a nominal voltage of 3.65 V. With 288 cells configured into three parallel strings, each containing 96 cells in series (96s3p), the rated voltage of the battery was 350 V (96 × 3.65), while its rated energy capacity was 60 kWh (96 × 3 × 3.65 × 58). However, the Chevrolet Bolt EV system will not be able to create 350 V when the voltages of its cells approach the cut-off voltage (196 × 2.5 = 240 V), because redundant cells were not included in the system primarily to minimise weight and expense, even though this will negatively affect reliability. Thus, in this article (the simulation model), two case studies are presented to highlight the proposed converter contributions. Compared to the first case study, one-third of the overall cells/Ms will be included in the second case study as redundant cells. Including redundant cells in the system will address the above issue and increase reliability. Additionally, redundant cells/Ms are required to produce Vref_a and Vref_b, simultaneously.

Accordingly, for both case studies, Vref_a and Vref_b are designed with the same value for their reference voltages of 350 V. C020 Li-ion Polymer cells are used in this article, where each cell has a nominal voltage of 3.65 V and a nominal capacity of 20 Ah, as presented in Table 4 and [35]. In the first case study, only one string of 96 cells (96 cells + 0% redundant cells/Ms) serially connected is taken into account in the simulation model. Thus, the battery pack’s rated energy capacity is equal to 7 kW (96 × 3.65 × 20). The 96 cells are divided into 16 Ms, each with six cells. In contrast, the second case study examines a single string of 132 cells (96 cells plus almost one-third of the overall cells as redundant cells), serially connected. Thus, the battery pack’s rated energy capacity is equal to 9.6 kW. The 132 cells are divided into 22 Ms, each with six cells. Figure 9 and Figure 10 highlight the contributions of the proposed converter, while Figure 11 demonstrates the process of dividing Ms into branch a and branch b during each Ts to generate Vref_a and Vref_b.

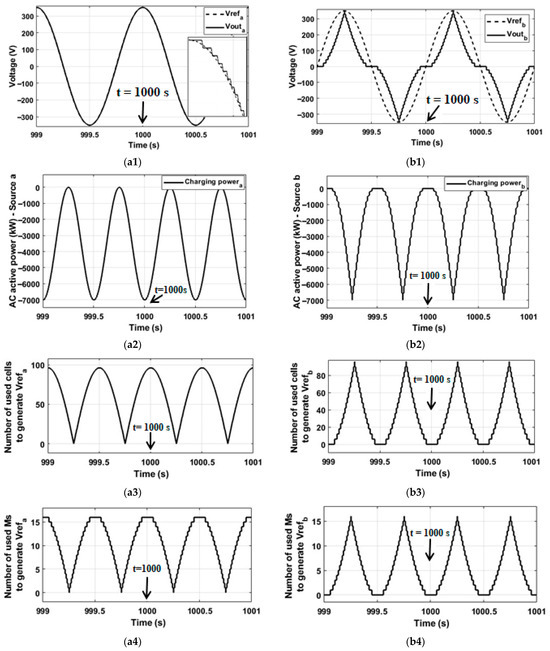

Figure 9.

The simulation results of the proposed converter for the first case study using 96 cells (16 Ms) to generate Vref_a and Vref_b, simultaneously: (a1) Vref_a and Vout_a, (a2) Pout_a, (a3) the number of used cells to generate Vref_a, (a4) the number of used Ms to generate Vref_a, (b1) Vref_b and Vout_b, (b2) Pout_b, (b3) the number of used cells to generate Vref_b, and (b4) the number of used Ms to generate Vref_b.

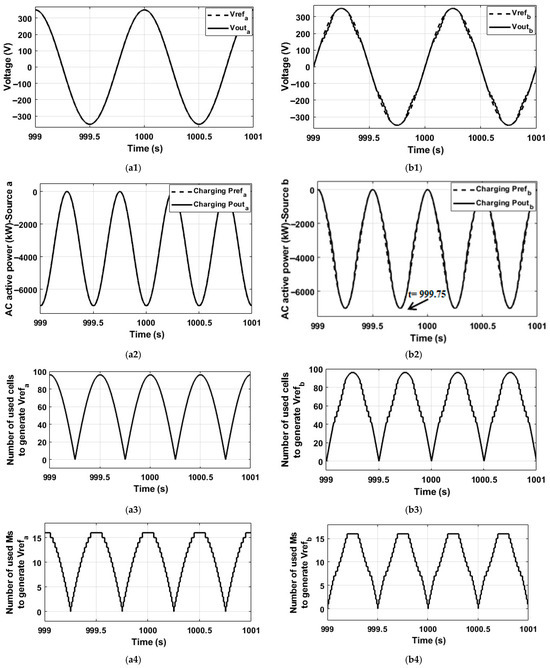

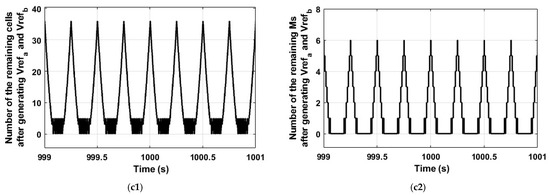

Figure 10.

The simulation results of the proposed converter for the second case study using 132 cells (22 Ms) to generate Vref_a and Vref_b, simultaneously: (a1) Vref_a and Vout_a, (a2) Pout_a, (a3) the number of used cells to generate Vref_a, (a4) the number of used Ms to generate Vref_a, (b1) Vref_b and Vout_b, (b2) Pout_b, (b3) the number of used cells to generate Vref_b, (b4) the number of used Ms to generate Vref_b, (c1) the number of remaining cells, and (c2) the number of remaining Ms.

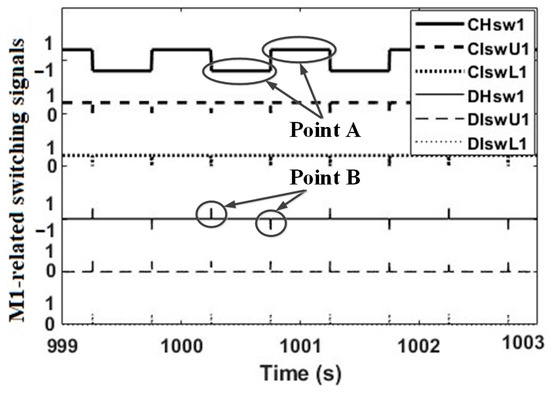

Figure 11.

Comparison between the synchronised movement of the internal switches related to M1 (CHswz, CIswUz, CIswLz, DHswz, DIswUz, and DIswLz).

Figure 9 and Figure 10 illustrate the simulation results of the first and second case studies, respectively. Furthermore, Figure 9 and Figure 10 demonstrate the capability of the proposed converter to generate Vout_a (350 V) and Vout_b (350 V), and an AC rated active power (Pout_a and Pout_b), simultaneously, when using 96 cells (16 Ms) and 132 cells (22 Ms), respectively, while highlighting the number of utilised cells/Ms to generate Vref_a and Vref_b during each Ts. In Figure 9(a1), a smooth multilevel sinusoidal Vout_a is generated (Vout_a and Vref_a are identical), while Vout_b is generated with reduced smoothness (Vout_b and Vref_b are not identical), as shown in Figure 9(b1). Accordingly, a smooth AC active power waveform is generated by branch a (Pout_a), as shown in Figure 9(a2), while the generated waveform by branch b to generate Pout_b is distorted, as shown in Figure 9(b2). The negative polarity of Pout refers to a charging operation due to the current (I) and the voltage (V) having different polarities during each Ts, and the power factor is taken as one (ideal case). In Figure 9(a3,a4), the number of cells and Ms is high enough to generate their corresponding reference voltage (Vref_a), while it is not enough to generate another corresponding reference voltage (Vref_b) simultaneously, as shown in Figure 9(b3,b4). However, the peak voltages for both reference voltages are generated. It is noteworthy that at 1000 s, for example, the number of cells/Ms employed to generate Vref_a (Figure 9(a3,a4)) is at its peak and subsequently declines, whereas the number of cells/Ms utilised to generate Vref_b (Figure 9(b3,b4)) is at its lowest and begins to ascend; nevertheless, the rates of increase and decrease are not equivalent. Furthermore, there are no remaining cells/Ms during any Ts. Consequently, redundant cells/Ms must be included in the system, as suggested in case study 2.

In Figure 10(a1,b1), smooth multilevel sinusoidal Vout_a and Vout_b are generated simultaneously by branch a and branch b, respectively. Therefore, smooth multilevel sinusoidal Pout_a and Pout_b are generated, as shown in Figure 10(a2,b2). During one quarter of the duty cycle (for example, from 999.75 s to 1000 s), the number of utilised cells ranges from 0 to 96 from a total of 132 cells, as exhibited in Figure 10(a3), while the number of utilised Ms ranges from 0 to 16 from a total of 22 Ms, as illustrated in Figure 10(a4). On the other hand, in Figure 10(b3,b4), the number of utilised cells and Ms range from 96 to 0 and from 16 to 0, respectively. However, while generating both reference voltages (Vref_a and Vref_b) simultaneously, there was a need for one more M during some Ts due to the cells’ voltages being less than 3.65 V. Therefore, a slight distortion was observed in the generation of Vref_b (Figure 10(b1)) during a particular Ts. In addition, during the Ts with slight distortion, it was observed that the number of utilised cells and Ms did not increase/decrease smoothly, as shown in Figure 10(b2,b3), respectively. To quantitatively evaluate this distortion, the THD of both output voltages was measured. The THD of Vout_a was found to be 0.42%, while that of Vout_b was 2.25%, confirming that the distortion in Vout_b remains minimal and within acceptable limits for multilevel inverter operation.

Figure 10(c1,c2) illustrate the number of remaining (idle) cells and M after generating each step of Vref_a and Vref_b, respectively. It can be observed that during any Ts of the system operation, there were remaining/idle cells and Ms. The number of idle cells ranges from 0 to 36, while the number of idle Ms ranges from zero to six. The highest idle number of cells/Ms occurs when either Vref_a or Vref_b is at its peak voltage. It is worth noting that the idle cells/Ms (36 cells/six Ms) are equal to one-third of the redundant cells/Ms that were included in case study 2, compared to case study 1. Consequently, redundant cells/Ms will not be used all the time; however, they are necessary. During some periods, the remaining/idle cells and Ms reach zero, as shown in Figure 10(c1,c2). Consequently, the authors recommend including an additional M in the system to ensure the waveforms are smoother (i.e., the recommended overall number of Ms that should be included in the system is equal to the number of Ms needed to generate the peak voltage of Vref_a × 1.33 + 1).

The operating principle of the proposed converter, explained in Section 2.2 and Figure 6, involves distributing cells/Ms into two branches during each Ts of a duty cycle to generate Vref_a and Vref_b, simultaneously. This distribution is obtained by controlling the corresponding switches (CHswz, CIswUz, CIswLz, DHswz, DIswUz, and DIswLz) to operate in either the ON (1 or −1) or OFF (0) status, as detailed in Section 2.2. M1 and its associated switches are chosen to illustrate the distribution principle of Ms, as depicted in Figure 11. In Figure 11, M1 is utilised most of the time to generate Vref_a as shown at point A, where CHsw1 is ON (i.e., 1 or −1 to generate the positive or negative Vref_a, respectively), and CIswU1 and CIswL1 are also ON (1). When M1 is chosen to generate Vref_a, all switches related to Vref_b are OFF: DHsw1 (0), DIswU1 (0), and DIswL1 (0). In contrast, at point B, M1 is activated to generate Vref_b rather than Vref_a, and thus all switches related to Vref_a are OFF: CHsw1 (0), CIswU1 (0) and CIswL1 (0). Additionally, all switches related to Vref_b are ON: DHsw1 (1 or −1), DIswU1 (1), and DIswL1 (1). As a result, the operating principle of the proposed converter was validated, showing that M1 was activated to generate Vref_a during specific time steps and Vref_b during others. In other words, during any given Ts, M1 can be engaged in either Vref_a or Vref_b, but not both simultaneously.

4. Conclusions

This article has proposed a new DCHMMC for serially connected Li-ion cells in an EV battery pack, designed to achieve optimal cell/M utilisation. The proposed dual-source converter was designed to enable the simultaneous integration of two sources, which can operate in three distinct modes. Firstly, it allows for dual-source charging of the cells/Ms for fast charging and improving vehicle availability. Secondly, dual-source discharging the cells/Ms enables it to support two loads simultaneously, thereby maximising power delivery and supporting V2G operation. Finally, one source charges while the other discharges for dynamic operation. Each individual cell was interfaced through L-bridge switches rather than conventional H-bridges, reducing the total switch count while maintaining independent monitoring and control. Furthermore, each M, composed of serially connected cells, was integrated with two H-bridges (CHswz and DHswz) and additional MOSFET switches (CIswUz, DIswUz, CIswLz, and DIswLz), allowing connection to two sources and simultaneously generating two sinusoidal multilevel output voltages (Vout_a and Vout_b). Only a single H-bridge (CHswz or DHswz) was active per M during each Ts, enabling direct DC–AC/AC–DC two-phase conversion with a 90-degree phase shift between outputs. In addition to its unique operating features, the proposed DCHMMC exhibits strong adaptability and potential for future enhancement. Although the current work does not include the implementation of an active SoC balancing mechanism, the proposed DCHMMC structure was intentionally designed to accommodate such functionality. Owing to its modular and scalable architecture, the proposed DCHMMC can be easily configured for different EV battery specifications by adjusting the number of Ms, cell arrangements, and control parameters. This flexibility enables compatibility with various voltage levels, power ratings, and cell chemistries, making the proposed converter a suitable foundation for a wide range of EV powertrain architectures and future control enhancements. The effectiveness of the proposed converter was validated through MATLAB/Simulink. In the first case study, 96 cells/16 Ms (without redundant cells/Ms) were utilised, where Vout_a was obtained with a smooth sinusoidal waveform, while Vout_b was observed with reduced smoothness due to insufficient cell/M availability at specific intervals. In the second case study, 132 cells/22 Ms (with one-third redundant cells/Ms) were employed, and smooth sinusoidal multilevel waveforms of both Vout_a and Vout_b, each with a 350 V peak, were generated simultaneously. Across system operation, idle cells were found to vary between 0 and 36, and idle Ms between zero and six, demonstrating the improved utilisation capability of the converter.

Future work will be directed toward the development of an active SoC balancing strategy integrated with the proposed DCHMMC, through which effective charge equalisation across cells and Ms will be ensured. In addition, it will focus on fabricating a hardware prototype of the proposed DCHMMC to validate its performance under practical operating conditions experimentally.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.A., M.A., and R.M.N.; methodology, A.B.A.; software, A.B.A., M.A., and O.A.; validation, A.B.A., R.M.N., and O.A.; formal analysis, H.G. and C.C.; investigation, A.B.A. and R.M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.A.; writing—review and editing, O.A., C.C., M.A., H.G., and R.M.N.; supervision, A.B.A.; funding acquisition, R.M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All original contributions of the study were included in this article, with further information available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Panchanathan, S.; Vishnuram, P.; Rajamanickam, N.; Bajaj, M.; Blazek, V.; Prokop, L.; Misak, S. A comprehensive review of the bidirectional converter topologies for the vehicle-to-grid system. Energies 2023, 16, 2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Mousa, H.H.H.; Shaaban, M.F.; Azzouz, M.A.; Awad, A.S.A. A comprehensive review on charging topologies and power electronic converter solutions for electric vehicles. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2023, 12, 675–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevdari, K.; Calearo, L.; Andersen, P.B.; Marinelli, M. Ancillary services and electric vehicles: An overview from charging clusters and chargers technology perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipu, M.S.H.; Miah, S.; Ansari, S.; Meraj, S.T.; Hasan, K.; Elavarasan, R.M.; Al Mamun, A.; Zainuri, M.A.A.M.; Hussain, A. Power electronics converter technology integrated energy storage management in electric vehicles: Emerging trends, analytical assessment and future research opportunities. Electronics 2022, 11, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasian, S.; Farsijani, M. A single-switch high step-up Zero Current Switching DC-DC converter based on three-winding coupled inductor and voltage multiplier cells with quasi resonant operation. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 2022, 50, 4419–4433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbytskyi, I.; Lukianov, M.; Nassereddine, K.; Pakhaliuk, B.; Husev, O.; Strzelecki, R.M. Power converter solutions for industrial PV applications—A review. Energies 2022, 15, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, H.H.; Youssef, A.-R.; Mohamed, E.E. State of the art perturb and observe MPPT algorithms based wind energy conversion systems: A technology review. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 126, 106598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroti, P.K.; Padmanaban, S.; Bhaskar, M.S.; Ramachandaramurthy, V.K.; Blaabjerg, F. The state-of-the-art of power electronics converters configurations in electric vehicle technologies. Power Electron. Devices Compon. 2022, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatai, S.; Salem, M.; Ishak, D.; Das, H.S.; Nazari, M.A.; Bughneda, A.; Kamarol, M. A review on state-of-the-art power converters: Bidirectional, resonant, multilevel converters and their derivatives. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, P.; Kumar, J.; Surjan, B.S. A review on reduced switch count multilevel inverter topologies. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 22281–22302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronanki, D.; Williamson, S.S. Modular multilevel converters for transportation electrification: Challenges and opportunities. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2018, 4, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busquets-Monge, S.; Filba-Martinez, A.; Alepuz, S.; Nicolas-Apruzzese, J.; Luque, A.; Conesa-Roca, A.; Bordonau, J. Multibattery-fed neutral-point-clamped DC–AC converter with SoC balancing control to maximize capacity utilization. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 67, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, A.Q.; Liang, Z.; Bhattacharya, S. Analysis and design of active NPC (ANPC) inverters for fault-tolerant operation of high-power electrical drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2011, 27, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallo, N.; Foulkes, T.; Modeer, T.; Coday, S.; Pilawa-Podgurski, R. Power-dense multilevel inverter module using interleaved GaN-based phases for electric aircraft propulsion. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), San Antonio, TX, USA, 4–8 March 2018; pp. 1656–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barahouei, V.; Barakati, S.M.; Haredasht, M.R.; Hashkavayi, M.B. Capacitor voltage balancing, capacitance monitoring, and fast fault detection in a nested neutral point clamped (NNPC) converter with the reduced number of sensors. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 119, 109543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn-Gomba, L.; Magne, P.; Danen, B.; Emadi, A. On the concept of the multi-source inverter for hybrid electric vehicle powertrains. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 33, 7376–7386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.B.; Ooi, C.A.; Ishak, D.; Abdullah, M. Optimal cell utilisation with state-of-charge balancing control in a grid-scale three-phase battery energy storage system: An experimental validation. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 9043–9059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.B.; Ooi, C.A.; Ishak, D.; Teh, J. State-of-charge balancing control for On/OFF-line internal cells using hybrid modular multi-level converter and parallel modular dual L-bridge in a grid-scale battery energy storage system. IEEE Access 2018, 7, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Ooi, C.A.; Alturki, A.; Desa, M.K.M.; Amir, M.; Ahmad, A.B.; Ishak, M.K. A novel active cell balancing topology for serially connected Li-ion cells in the battery pack for electric vehicle applications. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quraan, M.; Yeo, T.; Tricoli, P. Design and control of modular multilevel converters for battery electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2015, 31, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korn, A.J.; Winkelnkemper, M.; Steimer, P. Low output frequency operation of the modular multi-level converter. In Proceedings of the 2010 Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Atlanta, GA, USA, 12–16 September 2010; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 3993–3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereda, J.; Dixon, J. 23-level inverter for electric vehicles using a single battery pack and series active filters. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2012, 61, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.B.; Ooi, C.A.; Ishak, D.; Teh, J. Cell balancing topologies in battery energy storage systems: A review. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Robotics, Vision, Signal Processing and Power Applications: Enabling Research and Innovation Towards Sustainability, Penang, Malaysia, 14–15 August 2018; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.B.; Ooi, C.A.; Ali, O.; Charin, C.; Maharum, S.M.M.; Swadi, M.; Salem, M. Renewable integration and energy storage management and conversion in grid systems: A comprehensive review. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 2583–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.B.; Ooi, C.A.; Ishak, D. State-of-Charge Balancing Control for Optimal Cell Utilisation of a Grid-Scale Three-Phase Battery Energy Storage System Using Hybrid Modular Multilevel Converter Topology Without Redundant Cells. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 53920–53935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, X.; Liang, J.; Pang, H.; Goncalves, J. Reliability modeling and evaluation of MMCs under different redundancy schemes. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2017, 33, 2087–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani-Ahmad, A.; Ooi, C.A. Optimal cell utilization for improved power rating and reliability in a grid-scale three-phase battery energy storage system using hybrid modular multilevel converter topology without redundant cells. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2019, 9, 1780–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daowd, M.; Omar, N.; Bossche, P.V.D.; Van Mierlo, J. Passive and active battery balancing comparison based on MATLAB simulation. In Proceedings of the 2011 Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference (VPPC), Chicago, IL, USA, 6–9 September 2011; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadde, S.; Lukka, B.G.; Gali, S.M.K.; Gadde, P.S. A Hybrid Cascaded Multilevel Converter for Battery Vitality Administration Connected In Electric Transport for Battery Energy Management. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 87, 01015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Ooi, C.A.; Desa, M.K.M.; Ishak, M.K.; Ammar, K. A new active cell equalizer for series connected lithium-ion battery pack in electric vehicle application for fast equalization. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 27, 101149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, C.A.; Rogers, D.; Jenkins, N. Balancing control for grid-scale battery energy storage system. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.—Energy 2015, 168, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, O.; Rajabloo, T.; De Ceuninck, W.; Daenen, M. Non-isolated DC-DC converters in fuel cell applications: Thermal analysis and reliability comparison. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi G., S.M.; Nikdel, M. Various battery models for various simulation studies and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 32, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Guo, X.; Dou, X.; Zhang, X. A rapid online calculation method for state of health of lithium-ion battery based on coulomb counting method and differential voltage analysis. J. Power Sources 2020, 479, 228740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ePLBC. High Energy Produce Datasheet, Document C020 Model; EIG Energy Innovation Group Company Ltd.: Cheonan, Republic of Korea, 2007; Available online: https://www.liionbms.com/pdf/eig/ePLBC.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).