Abstract

The transformation of transport towards solutions based on renewable energy sources (RES) and energy storage systems represents a response to global climate and regulatory challenges. The integration of electric vehicles with charging infrastructure and the power grid reduces emissions and enhances system flexibility; however, it simultaneously introduces new areas of risk and should therefore be subject to significance assessment. This study applies an integrated methodology for assessing the significance of changes, combining FMEA-based analysis with risk registers and sustainability indicators (six criteria). The transport system and associated storage infrastructure were compared before and after the implementation of RES, considering criteria such as the effects of system failure, complexity, innovation, monitoring, reversibility, and additionality. The results indicate that traditional risks associated with fossil fuels (e.g., exhaust emissions, pipeline failures) are eliminated, but new risks emerge. The highest increases in Risk Priority Numbers (RPN) were observed for cyber threats, charging infrastructure overloads, and the cyclic degradation of energy storage systems. Environmental and organizational risks also intensified, including those related to battery recycling as well as the lack of regulatory frameworks and procedures. The integration of transport with RES and energy storage should be regarded as a significant change. In addition to environmental and energy benefits, it introduces new, complex risk areas that require in-depth risk analysis, the implementation of monitoring systems, and adequate regulatory and preventive measures. At the same time, the proposed methodology enables the identification of changes critical to power system stability, the improvement of energy efficiency, and the advancement of the transition towards climate neutrality.

1. Introduction

Dynamic changes in the transport sector, driven by global climatic, regulatory, and technological challenges [1], are directing the attention of researchers and practitioners towards integrated solutions based on renewable energy sources (RES) and energy storage systems. The future of mobility increasingly depends on the ability to effectively combine electric and hydrogen vehicles with charging stations and the energy infrastructure that ensures stable grid operation while simultaneously reducing greenhouse gas emissions. A key aspect of this process is the symbiosis between the vehicle and its surrounding energy ecosystem—including charging points and storage facilities—which determines the reliability and safety of operation.

However, the integration of transport with RES introduces new challenges and potential sources of risk. The variability of wind and solar energy generation can lead to instability in charging infrastructure supply, creating the need for energy buffering and the deployment of advanced storage systems. The storage units themselves—regardless of the applied technology (lithium-ion, sodium, hydrogen)—are associated with risks of failure, fire, or material degradation. Moreover, the development of smart grids and digital communication between vehicles and charging stations increases the system’s vulnerability to cyber threats. In the case of hydrogen, additional risks relate to the safety of storage and distribution under high pressure.

Given these conditions, there arises a need for objective and repeatable analytical tools that not only enable the identification of hazards but also the assessment of the significance of changes introduced into transport systems. Existing approaches, based largely on expert judgment and qualitative methods, do not fully address the complexity of energy–transport transformation processes. The proposed response to this gap is a novel methodology for change significance assessment, developed in research on the deployment of electric vehicles in transport systems. This methodology combines classical FMEA with a systems approach based on risk registers and sustainability indicators. By incorporating parameters of uncertainty and consequences, it enables the development of a more transparent and objective risk assessment matrix, allowing both the classification of new hazards and their prioritization.

The aim of this publication is to conduct an assessment of the significance of changes associated with the integration of renewable energy sources in transport, with particular emphasis on the role of charging stations, charging points, and storage infrastructure. The study presents the application of the new methodology for assessing the significance of changes to the analysis of transport–RES integration processes, enabling the identification of benefits in terms of energy system stability and emission reduction, as well as new areas of risk requiring further research and preventive actions. The article focuses on the identification and classification of technological, environmental, and operational hazards (including the human factor) that may determine the pace and scale of transport transformation towards sustainable mobility. At the same time, this analysis supports the evaluation of the extent to which the integration of transport with RES and energy storage can improve grid stability, increase the efficiency of renewable energy utilization, and accelerate the energy transition. The proposed approach is intended not only for academic evaluation but also as a practical decision-support tool for distribution system operators (DSOs) and policymakers when assessing safety-critical and sustainability-driven technological transitions. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

- −

- Development and application of an integrated methodology for assessing the significance of technological changes in transport systems using an FMEA-based framework combined with risk registers and sustainability indicators.

- −

- Comparative analysis of fossil fuel and RES–EV–BESS transport systems to quantify changes in Risk Priority Numbers (RPN) across technical, organizational, and environmental dimensions.

- −

- Identification of new high-priority risks related to digitalization (cyber threats, EMS/BMS vulnerabilities) and system complexity (V2G integration, transformer overloads).

- −

- Demonstration of the methodology’s potential as a universal tool for energy transition planning and regulatory decision support.

2. Literature Review

The starting point for the analysis is the perception of transport systems not as a collection of separate components (vehicle–charger–grid), but rather as an integrated cyber-physical system coupled with RES and energy storage. The literature indicates that bidirectional functionalities—vehicle-to-grid (V2G) and vehicle-to-home (V2H)—transform EV fleets into distributed flexibility resources capable of providing system services (frequency regulation, peak shaving, voltage support) and improving the utilization of variable RES [2,3,4,5]. Recent reviews highlight that, with proper coordination, EV aggregations enhance grid stability and reliability, reduce peak demand, and enable greater penetration of wind and PV generation. At the same time, they require advanced control layers and ancillary service pricing mechanisms to prevent local overloads and power quality degradation [6,7].

In parallel, the body of research on V2H is expanding, positioning it as a tool for household energy resilience. Multi-regional simulations and case studies show that contemporary EVs—even at partial states of charge—can sustain critical household loads for several hours, serving as a flexible buffer during outages [8,9]. This increases the systemic value of transport–RES integration, especially when combined with prosumer photovoltaics and home storage systems. However, the literature emphasizes the need for battery lifecycle management (calendar and cyclic degradation) and the adaptation of consumption profiles to climatic and seasonal conditions [10].

Studies on mass charging—particularly fast and ultra-fast charging—identify typical distribution network power quality issues: voltage fluctuations, flicker, harmonic distortions, and local transformer overloads [5,6,7]. The need for charging control, active filtering, and selective network reinforcement is emphasized to reduce THD (Total Harmonic Distortion) and maintain acceptable voltage profiles. From the perspective of DSOs, V2G integration can either mitigate these effects (through controlled power injection) or exacerbate them if aggregator coordination and market design are lacking [2,5].

The integration of vehicles with charging infrastructure also generates new areas of risk that can be assessed using the methodology proposed in the referenced study [11]. This publication extends that methodology and demonstrates its capability for objective, quantitative assessment. In the domain of energy storage, both scientific literature and industry reports consistently highlight risks associated with thermal runaway in battery systems, including stationary BESS (Battery Energy Storage System) units supporting charging stations [12,13]. The NFPA 855 standard and industry guidelines define installation and protection requirements (ventilation, detection, separation, explosion-proof safeguards), emphasizing that the apparent “suppression” of fire may not halt chain reactions and can lead to the accumulation of flammable gases. Incidents in large BESS installations further illustrate the risk of cascading failures and environmental consequences [12,13].

Another dimension involves cyber risks characteristic of the EV (Electric Vehicle)–EVSE (Electric Vehicle Supply Equipment (charging station))–CPMS (Charging Point Management System)–operator/DSO (Distribution System Operator) chain, where communication relies on OCPP and ISO 15118 [14]. Current research identifies vulnerabilities in authentication, firmware updates, communication integrity, and certificate management, along with DDoS attacks and manipulation of billing/charging commands [15,16]. Recommended countermeasures include cryptographic hardening, network segmentation, penetration testing, and anomaly monitoring at the CPMS level [15,16,17].

Finally, literature on V2G as a balancing service provider underscores the importance of market and regulatory frameworks (compensation mechanisms, aggregation, access to ancillary service markets). Modeling studies demonstrate potential reductions in peak demand and increased RES utilization, but also reveal sensitivity to fleet control, SOC distributions, low-voltage network constraints, and battery wear [2,3,4,5]. These factors—within the terminology of change assessment—correspond to the categories of “complexity/innovation” (feeding into the uncertainty parameter), “monitorability” (ability for continuous oversight of fleets/aggregators), and “reversibility” (reverting stations to unidirectional operation in case of V2G service degradation).

When these findings are juxtaposed with the newly proposed methodology for assessing change significance [11], three groups of methodological recommendations emerge for analysing complete transport systems integrated with RES and storage:

- −

- Extending risk registers with scenarios characteristic of V2G/V2H (e.g., LV/MV transformer overloads from unsynchronized injections, power quality degradation, cascading BESS failures);

- −

- Including cybersecurity criteria as separate entries in the assessment matrix (with weights derived from the criticality of control and settlement processes);

- −

- Distinguishing between technical consequences (stability, power quality, fire safety) and operational/market consequences (ancillary service unavailability, risk of regulatory penalties), each with separate scaling.

This structured assessment approach—based on risk registers, sustainability indicators, and an “uncertainty × consequence” matrix—was outlined and validated in foundational studies [8,10,11], which demonstrated, among other findings, the high prioritization of secondary battery fire risks and the usefulness of combining classical FMEA (Failure Mode and Effects Analysis) with a systems perspective.

Contemporary scientific publications consistently indicate that transport integration with RES and storage—including V2G/V2H—delivers tangible benefits for power system flexibility and stability, but simultaneously generates new, specific risk areas. Typical renewable-integrated charging topologies can be classified into three configurations: AC-coupled systems, where renewable generation and storage units are connected to a common AC bus through inverters, DC-coupled systems, which allow more efficient bidirectional power flow and are better suited for vehicle-to-grid (V2G) applications, and hybrid topologies, combining both interfaces to enhance operational flexibility and energy efficiency. These areas (distribution grid stability and power quality, battery storage fire safety, and cyber-physical security of the EV–EVSE–CPMS chain) are measurable and lend themselves to evaluation using the developed methodology, enabling objective classification of change significance and prioritization of preventive and investment measures [11,12,15].

Recent research (2023–2025) has further strengthened the understanding of vehicle-to-grid (V2G) integration and the associated cyber-physical risks. Kumar and Channi [18] conducted a comprehensive bibliometric review of global V2G research, identifying technological, economic, and regulatory trends shaping the future of EV–grid interaction. He et al. [19] proposed a two-layer optimization approach for coordinated V2G charging and discharging, highlighting the role of hierarchical algorithms in improving grid flexibility and efficiency. Razzaque et al. [20] systematically reviewed cybersecurity issues in V2G systems, emphasizing vulnerabilities in communication protocols and proposing resilient authentication frameworks. Complementarily, Biswas [21] discussed the architecture of V2G charging stations and their dependence on secure data exchange between EVs, charging equipment, and distribution system operators (DSOs). Collectively, these studies confirm that current advances in V2G technologies are inseparable from cyber-physical security and coordinated control—dimensions directly addressed by the risk-based methodology proposed in this paper.

3. Significance of Change Assessment

The analyzed system reflects a medium-voltage urban distribution network typical of Central European conditions, with a total installed RES capacity of 30–40% and EV penetration rates projected at 15–20% of the vehicle fleet by 2030. The technical boundary of the study includes distribution substations, local charging hubs (AC/DC 22–150 kW), and energy storage facilities with capacities of 100–500 kWh. Rural and transmission-level interactions are beyond the present scope. This delineation ensures that the evaluated Risk Priority Numbers (RPN) correspond to realistic grid and transport parameters.

The research methodology is based on an integrated approach to risk assessment and the evaluation of change significance in transport systems coupled with renewable energy sources and energy storage. It constitutes a further development of the method presented in the referenced publication [11], enhancing the objectivity of assessment by basing decisions on the Risk Priority Number (RPN) assigned to one of six evaluation criteria.

In the first stage, the system under analysis is defined, covering both technical and organizational elements, along with the specification of its functional boundaries and operating environment. The system description is prepared in two states: before the implementation of the change and after its deployment. This dual-state representation enables a comparative analysis of potential hazards and their dynamics over time.

In the subsequent stage, potential hazards for the system—both prior to and after the change—are identified, and a hazard register is created. Each hazard is classified with reference to a set of criteria that include the following:

- Effects of system failure: a credible worst-case scenario in case of the failure of the system under assessment, considering the existence of safety barriers outside the system (F),

- Innovation used to bring about the change—this criterion covers innovations that affect both the entire transport industry and the organisation implementing the change (I),

- The complexity of the change (C),

- Monitoring: inability to monitor the change introduced throughout the entire life-cycle of the system and to carry out appropriate interventions (M),

- Reversibility of the change: inability to return to the system from before the change (R),

- Additionality: assessment of the significance of the change, considering all recent safety-related changes to the system under assessment that were not assessed as significant (A).

The hazard register constitutes the foundation for further analysis and enables the systematic organization of risks in a manner that facilitates their comparison and prioritization. Subsequently, the methodology applies an FMEA-based approach, in which each identified hazard is evaluated in terms of its probability of occurrence, the likelihood of detection, and the severity of its potential consequences [11]. The assessment results are assigned to predefined numerical scales, and the product of these three values determines the Risk Priority Number (RPN), which allows hazards to be classified according to their risk level.

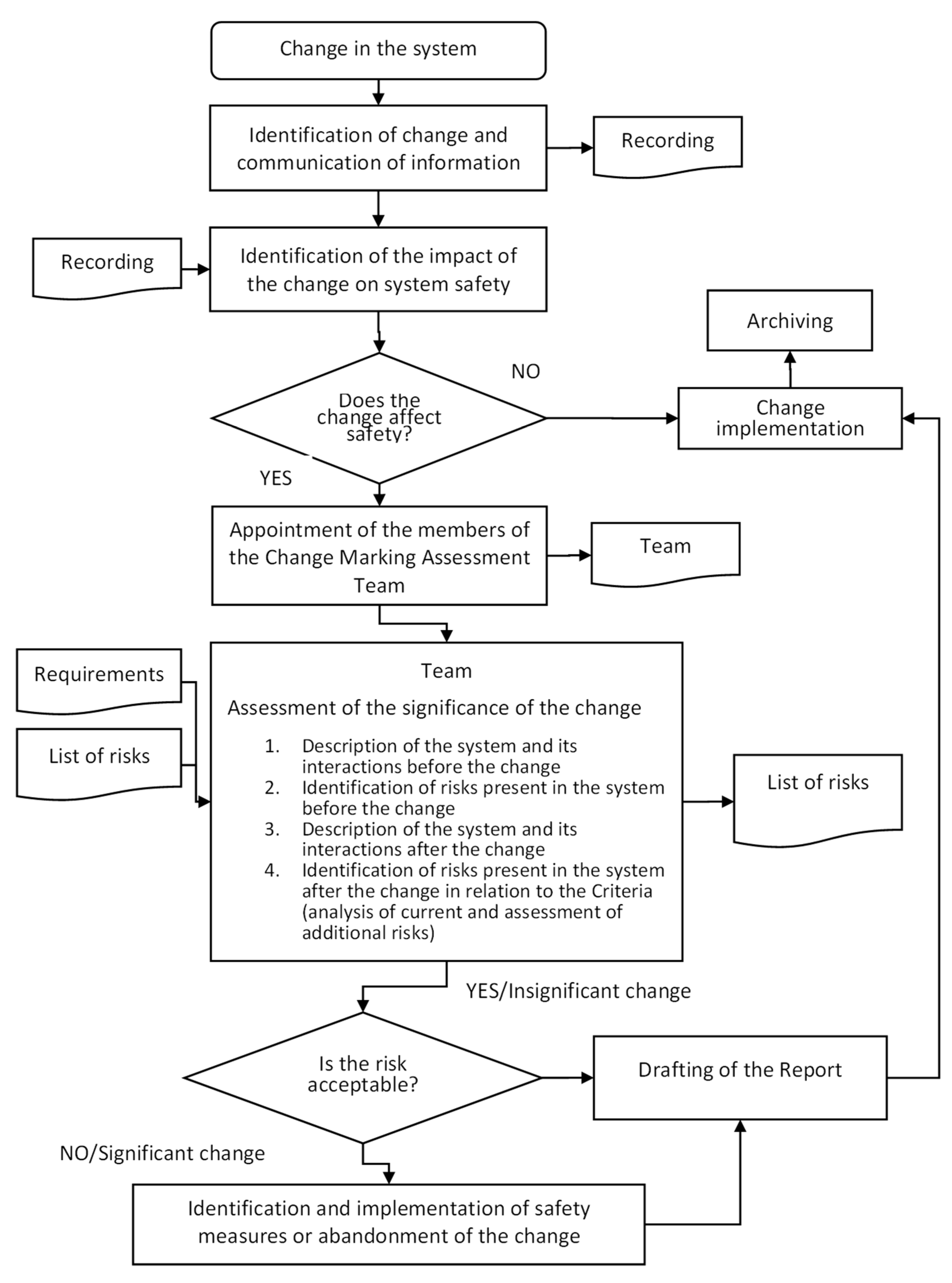

The determination of RPN for individual entries in the hazard register makes it possible to identify areas requiring immediate preventive actions, as well as those that may be tolerated under specific control measures. The assessment of the system both before and after the implementation of change further enables the identification of new risk areas and the variability of previously analyzed ones (system prior to change)—see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Change significance assessment procedure.

Figure 1 presents the complete workflow of the proposed Significance of Change Assessment. The procedure integrates FMEA-based RPN evaluation with qualitative sustainability and reliability criteria. The workflow is based on the authors’ research framework, which builds upon and extends classical FMEA and RAMS methodologies [7,11,15]. Comparative analysis shows that the inclusion of contextual parameters (probability of detection, reversibility, monitoring) enhances the method’s applicability to energy transition planning.

In the subsequent stage of the analysis, the FMEA results are transferred to the change significance assessment matrix. The parameters of innovativeness and complexity are grouped into the factor of “uncertainty,” whereas the effects, evaluated on the basis of risk and safety barrier analysis, are treated as “consequences.” The “uncertainty × consequence” matrix provides a synthetic representation of the position of each change and serves as the basis for determining whether it should be classified as significant or non-significant. Additionally, the criteria of monitorability and reversibility are considered, which may modify the outcome of the analysis by elevating the importance of certain changes due to limited control capabilities or the inability to restore the original state [11].

The final decision on the significance of a change is made on the basis of a combined assessment of RPN indicators, the position within the “uncertainty × consequence” matrix, and the evaluation of the additionality, monitorability, and reversibility criteria. The results of the study are presented in the form of hazard register tables, FMEA matrices, and the change significance map. The methodology assumes cyclical repetition of the analysis after the implementation of corrective measures, which allows for the updating of assessments as new operational experience is gained and as technologies evolve—see Figure 1.

The classification of Risk Priority Numbers (RPN) in this study follows the thresholds adopted in the authors’ earlier work [11], ensuring methodological consistency and comparability of results.

The numerical ranges defining the risk classes are as follows:

- −

- Low risk: RPN = 1–120—routine monitoring and standard control procedures are sufficient.

- −

- Moderate risk: RPN = 121–150—requires preventive or corrective measures to reduce occurrence or enhance detectability.

- −

- High risk: RPN ≥ 151— indicates critical hazards that demand immediate mitigation, redesign of system components, or regulatory intervention.

These thresholds reflect typical ranges used in FMEA-based safety management for complex energy and transport systems and allow for more transparent interpretation of change significance within the evaluated transport–RES–BESS framework.

4. Results

The system is characterized by a unidirectional flow of energy—from centralized generators and transmission networks toward end-users. Load management and energy demand planning are carried out in a static manner, without accounting for the dynamic exchange of energy between vehicles and the grid. The absence of distributed components means that risks associated with transport–energy integration are limited; however, the system remains vulnerable to rising fossil fuel costs, energy market volatility, and climate regulations.

Selected areas of risks characteristic of the system prior to change are illustrated below—Table 1.

Table 1.

Hazard register identified for the system prior to change—fossil fuels in transport.

The risks in the baseline system are concentrated along the fossil fuel supply chain (leakages, tanker transport, pipelines, exhaust emissions, large-scale oil spills) as well as on geopolitical vulnerabilities.

After the implementation of change, the transport system acquires an integrated character, combining transport infrastructure with renewable energy sources and local energy storage systems. The development of networks of charging points and stations enables the widespread use of electric vehicles, which no longer serve merely as a means of transport but also become active participants in the energy system. Through bidirectional technologies (V2G, V2H, V2B), vehicles can feed energy back into the grid, support the balancing of local microgrids, and enhance overall system flexibility.

The inclusion of renewable energy sources such as photovoltaics and wind power introduces additional variability in generation, but at the same time reduces emissions and supports the achievement of sustainable development goals. The deployment of energy storage—both stationary and mobile—makes it possible to stabilize power fluctuations, compensate for deficits during periods of low RES generation, and shift loads over time.

As a result, the post-change system evolves into a more complex and innovative arrangement, with a greater number of critical points and interfaces, but one that is also characterized by higher energy efficiency and improved adaptability to the dynamic conditions of power grid operation. Viewing transport systems as integrated cyber-physical arrangements coupled with RES and storage enables the identification of new risk areas, illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Hazard register identified for the system after change—RES in transport.

The risks unique to RES/EV/BESS systems relate primarily to digitalization and power engineering, including cyber threats to EMS/BMS/EVSE, RES variability, cyclic degradation of BESS, overloading of stations/transformers, incompatibility of V2G/V2X, as well as transformation costs and social acceptance.

The risk areas common to both the pre-change and post-change systems include: unauthorized access/theft (H2′ ↔ H2), emergency service interventions (H4′ ↔ H6), operational/maintenance errors (H5′ ↔ H7), drive system failures (T1′ ↔ T1), substance leaks (S2′ ↔ S2), operational waste (S3′ ↔ S3), noise/secondary emissions (S4′ ↔ S4), staff shortages (O1′ ↔ O1), and the lack of standardized procedures (O2′ ↔ O2).—see Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of hazard registers (fossil fuels vs. RES/EV/BESS).

In the conducted FMEA analysis for the transport system integrated with renewable energy sources and energy storage, particular attention was paid to comparing the identified hazards with analogous risk areas characteristic of the conventional fossil fuel-based system. This approach made it possible not only to determine new categories of risk emerging after the change but also to assess the variability of the Risk Priority Number (RPN) values with respect to common hazards.

The analysis demonstrated that many hazards have their counterparts in both systems, although their nature and scale of impact differ. An example is drive unit failures—associated with combustion engines and fuel leakages in the conventional system (T1′), versus traction batteries in the RES/EV/BESS system (T1). In this case, the RPN value decreased slightly (ΔRPN = −16), which is related to the implemented mitigation measures and the different nature of battery fires, considered in this evaluation as less severe than fuel-related fires.

A different picture, however, is observed for the majority of common hazards. In particular, transformer and station overloads (T3), cyclic degradation of storage systems (T2), and unauthorized access to system resources (H2) reached significantly higher RPN values after the change. This is the result of new risk factors, such as peak loads from EV charging or the intensive cyclic operation of cells in V2G modes.

Cybersecurity and digitalization of infrastructure emerged as areas of particularly significant risk growth. Hazards such as cyberattacks on energy management systems (H1) or manipulations of control signals leading to microgrid destabilization (H3) were either non-existent or marginal in the fossil fuel system. Following the change, their RPN values increased markedly (+173 and +144, respectively), classifying them among the critical hazards for the safety of the new system.

In the organizational domain, a clear increase in RPN is visible for hazards related to delays in infrastructure development (O5, ΔRPN = +120) and the lack of standardized procedures (O2, ΔRPN = +95). While in the conventional system these issues were largely limited to fuel logistics and ADR transport, in the new system they pertain to both grid connection processes and the delineation of responsibilities across a complex value chain involving network operators, prosumers, aggregators, and charging service providers.

In the environmental domain, a high degree of continuity between the two systems is observed. Pollutants related to waste disposal and recycling (S3), as well as secondary emissions and noise (S4), occur in both systems, but in different forms. In the fossil fuel transport system, they were associated with petroleum waste and engine emissions, whereas in the RES/EV/BESS system they arise from battery recycling processes, cooling systems, and emergency generators. For most of these hazards, RPN values increased (e.g., S3: +40, S2: +42), reflecting growing environmental awareness and the more complex character of new technologies.

In summary, the analysis shows that integrating transport with RES and energy storage leads to a significant transformation of the risk profile. Hazards characteristic of the conventional system, such as exhaust emissions or pipeline failures, are largely eliminated. However, they are replaced by new areas of risk—primarily those associated with digitalization, the unpredictability of RES generation, and battery lifecycle management. Furthermore, in the case of common hazards, a marked increase in RPN values is observed in most cases, clearly indicating that this change should be regarded as significant from the perspective of safety. It therefore requires the implementation of advanced monitoring tools and systemic preventive measures—see Table 4.

Table 4.

Hazard analysis for the post-change system.

The baseline transport system, i.e., prior to the introduction of changes, is based on conventional energy sources, particularly fossil fuels used to power combustion engine vehicles. In this configuration, the energy infrastructure is not integrated with renewable energy sources nor with local storage systems. Charging stations and points are absent, and consequently, electric vehicles do not constitute a significant element of the transport structure. The results presented in this section were obtained through a structured expert evaluation process involving 10 professionals representing DSOs, RES operators, and electromobility stakeholders. Each expert independently rated the probability, severity, and detectability parameters for identified risk modes according to the scales defined in publication [11]. The mean values of these assessments were then used to calculate the RPNs shown in Table 4.

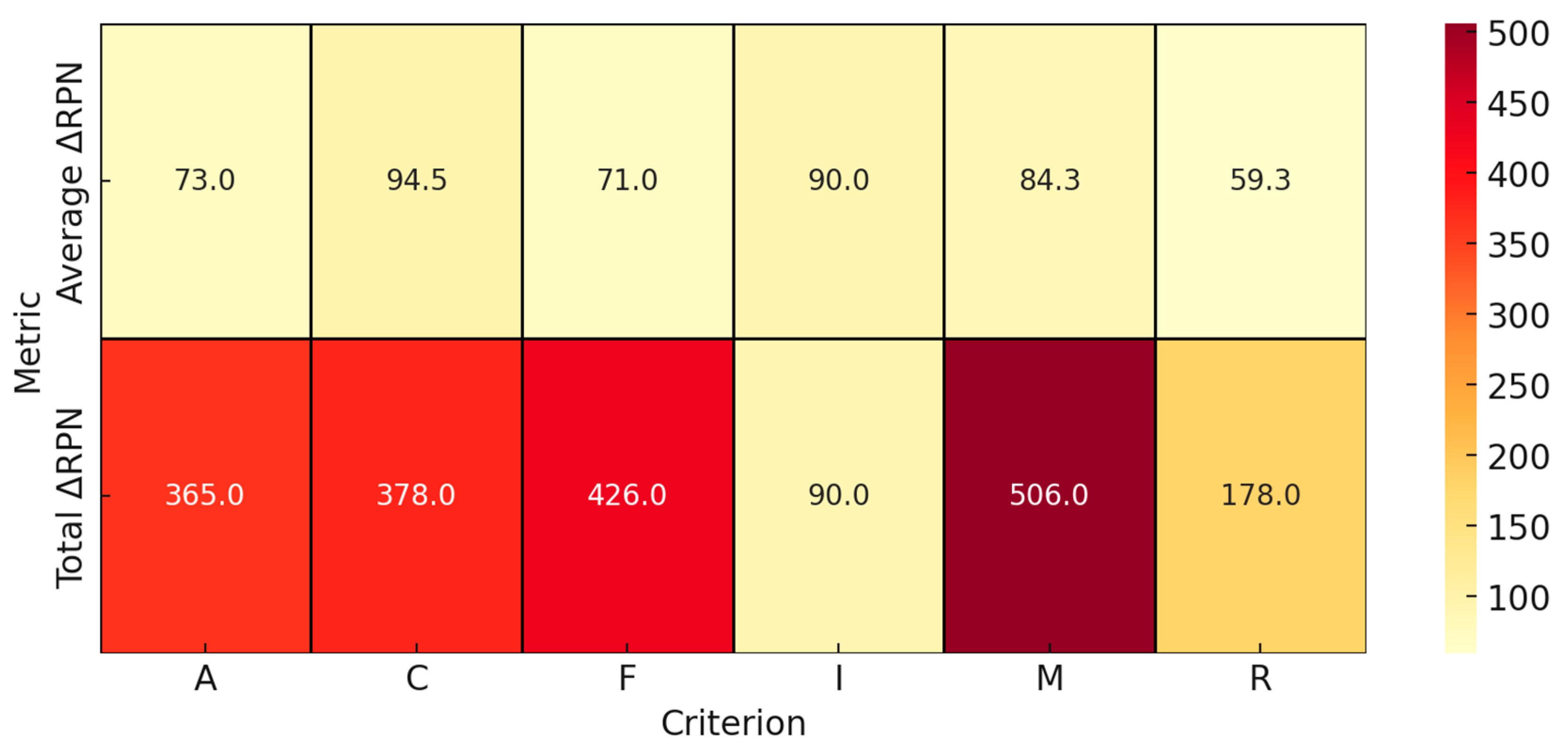

The results presented in Table 4 show that risks associated with digital control, communication systems, and cybersecurity dominate in the RES–EV–BESS transport configuration, indicating a clear shift from mechanical toward information-related vulnerabilities. The greatest cumulative increase in ΔRPN concerns criterion F (effects of system failure), with a total of 606 and an average of approximately 101. This indicates that the consequences of failures in the post-change system have a significantly greater impact compared to the conventional system. A substantial increase was also recorded in criteria M (monitoring) and C (complexity), with totals of 486 and 378, respectively. This demonstrates that monitoring difficulties and system complexity constitute key areas of risk—Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Heatmap of average and total ΔRPN by significance assessment criterion.

Criterion A (additionality) also shows a clear increase (403), pointing to the accumulation of changes that had not previously been assessed. Criterion I (innovation), although represented by a single case, reached a high average (90), suggesting that the introduced innovations generate considerable risk. The lowest increase was observed for criterion R (reversibility); however, the average value of 60.7 indicates that risks of irreversibility should still be regarded as significant.

The next stage of the change significance assessment was conducted in accordance with the methodology presented in the literature [11]. The only difference lies in the objectivity of data specific to each criterion. The starting point was the Risk Priority Number (RPN) values obtained for the post-change system, which—after being assigned to the appropriate evaluation criteria—enabled the determination of the degree of change significance.

In the first stage, following the methodology, the criteria of innovativeness and complexity were combined into the parameter uncertainty, while the consequences of potential system failures were assigned to the parameter impact. The analysis of RPN values showed that solutions such as the integration of electric vehicles with V2G infrastructure, intensive operation of energy storage systems in bidirectional modes, and system interaction with variable RES are characterized by high technological complexity and partial innovativeness. On the adopted scale, this corresponds to a value of uncertainty = 3. At the same time, the consequences of potential failures—including secondary battery fires, local power outages, and cascading infrastructure damage—were classified as critical, corresponding to impact = 3. The product of both parameters (uncertainty × impact) yielded a result of 9, which in the change significance matrix corresponds to the “borderline” level. This indicates that the assessment based solely on these two fundamental criteria does not unequivocally determine the significance of the change, making it necessary to incorporate additional criteria.

In the subsequent stage, supplementary criteria were included in the analysis. The monitoring (M) criterion revealed significant limitations: both in the observability of BESS operation, the variability of wind and solar generation, and the dynamic loading of charging points. The complexity of these processes increases uncertainty and operational risk. The reversibility (R) criterion indicates that a return to the pre-change state—based on fossil fuel infrastructure—should be regarded as impossible in the long term, which elevates the durability and irreversibility of transformation impacts. The additionality (A) criterion shows that the present change is one in a sequence of ongoing transport–energy system transformations, and the accumulation of earlier, not fully assessed modifications amplifies the overall level of risk.

Incorporating these additional criteria shifts the assessment from a “borderline” level toward a significant change. This implies the necessity of conducting an in-depth risk analysis and implementing extended control and preventive measures. The result confirms that while the integration of transport with RES and energy storage reduces traditional environmental and logistical hazards, it simultaneously generates new areas of risk with high complexity and monitoring challenges, which must be addressed in the processes of implementation and operation.

5. Discussion

The analysis indicates that the integration of transport with renewable energy sources and energy storage systems constitutes a significant change—both in terms of reducing traditional hazards and in the emergence of new, more complex risk areas. A key element of the study was not only the identification of these hazards but also the application and validation of a new methodology for assessing the significance of change, which combines classical FMEA analysis with risk registers and an “uncertainty × consequence” matrix. Importantly, the proposed approach not only enables the classification of risks but also identifies which energy innovations genuinely enhance system efficiency—for instance, through stabilizing RES operation, improving the use of storage systems, and supporting grid balancing. In this sense, the methodology becomes a tool not only for safety assessment but also for strategic planning of the energy transition.

Compared with classical risk assessment methods—often reliant on qualitative expert opinions—the proposed methodology offers a higher degree of objectivity. The use of the Risk Priority Number (RPN) together with additional criteria such as reversibility, monitorability, and additionality of changes makes it possible not only to prioritize hazards but also to provide a synthetic representation of their significance in the context of the entire system. Alternative approaches have been presented in the literature, such as quantitative methods based on the resilience analysis of power networks [22], but these typically focus exclusively on the technical aspects of stability and reliability. The methodology proposed in this study broadens this perspective by incorporating factors of innovativeness, complexity, and additionality, thus capturing the dynamics of technological transformation under conditions of high uncertainty.

Particularly important was the grouping of innovativeness and complexity factors into the parameter “uncertainty” and linking it to the consequences of failures. This approach makes it possible to capture the fact that new technologies—although promising in terms of energy efficiency—may simultaneously generate risks that are difficult to monitor but potentially critical in their impacts. The comparative analysis of transport systems before and after the change demonstrated that the method allows the identification both of the elimination of traditional risks (e.g., exhaust emissions) and of the growing importance of new risk areas—from cyberattacks to the cyclic degradation of batteries.

The universal character of the methodology means that it can also be successfully applied in other segments of the energy sector. In contrast to approaches focusing solely on one type of technology (e.g., distribution networks, energy storage), the presented method enables the assessment of systemic transformation, in which innovations emerge simultaneously across multiple domains. It can be applied to the evaluation of the implementation of new-generation technologies (wind farms, PV installations, hydrogen systems), the deployment of smart grids, or large-scale storage facilities, as well as to the analysis of organizational and regulatory changes.

It should be emphasized that the proposed methodology supports not only technical analyses but also the decision-making processes of regulators and system operators. Its practical application makes it possible to classify and prioritize investments, identify areas requiring regulatory measures, and plan preventive actions. In a broader perspective, it may serve as a comparative tool for different branches of energy and transport, which is particularly important in the context of climate policies and the pursuit of climate neutrality.

The methodology proposed in this study has not only confirmed its usefulness in analysing the transport system but has also demonstrated its potential as a universal tool for the entire energy sector. Its further development—including the incorporation of social and economic risks—may establish it as a foundation for comprehensive analyses of energy transitions and support decision-making under conditions of high uncertainty and system complexity.

The generalizability of the proposed method extends beyond the specific case analyzed. Because the RPN-based framework is parameterized through universal criteria (probability, severity, detectability), it can be adapted to regions with different grid topologies, EV penetration levels, and regulatory frameworks. Nonetheless, calibration of scale factors—particularly for monitoring and reversibility—should reflect local DSO practices and grid resilience characteristics. Future studies should validate the approach across diverse urban and rural settings to confirm robustness under varying conditions.

6. Conclusions

The conducted analysis has demonstrated that the integration of transport systems with renewable energy sources and energy storage represents a significant change—both due to the reduction of traditional hazards characteristic of fossil fuel-based transport and the emergence of new, specific areas of risk. The introduction of electric vehicles, bidirectional technologies (V2G, V2H), and energy storage improves energy efficiency and reduces emissions, but simultaneously leads to an increase in threats related to cybersecurity, the overloading of power infrastructure, and the cyclic degradation of batteries.

The key achievement of this study is the verification and further development of a new methodology for assessing the significance of change, which combines FMEA-based analysis, risk registers, and the “uncertainty × consequence” matrix. This method enables a quantitative and more objective evaluation of technological transformations, accounting not only for the scale of hazards but also for their reversibility, monitorability, and additionality. This dual perspective makes it possible to capture both the elimination of classical risks (e.g., exhaust emissions, pipeline failures) and the significant increase in new risk areas requiring preventive measures.

The universal character of the proposed methodology makes it applicable beyond transport, extending its usefulness to the entire energy sector. In the context of deploying new-generation, storage, or grid technologies, this approach may serve as a tool for supporting investment, planning, and regulatory decisions. Of particular importance is its potential to compare and prioritize risks in complex systems characterized by high levels of uncertainty and innovation.

The transition of transport towards RES and energy storage is both inevitable and desirable from environmental and climate policy perspectives. At the same time, it requires a new approach to managing system safety and reliability. The proposed methodology can play a crucial role in this process, serving as a systematic assessment tool that helps to minimize risk, support energy efficiency, and guide the development of regulations and procedures adequate to the challenges of future mobility and energy systems. Importantly, the approach not only classifies risks but also identifies which energy innovations genuinely improve system performance—for example, by stabilizing RES operation, enhancing the utilization of storage systems, and supporting grid balancing. In this sense, the methodology becomes not only a tool for safety evaluation but also for the strategic planning of the energy transition. Future work will focus on extending the methodology to multi-level distribution systems and validating it under diverse regional grid conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.C. and D.B.; Methodology, K.C. and J.T.; Validation, K.C. and J.T.; Resources, K.C., J.T. and D.B.; Writing—original draft, K.C.; Writing—review & editing, J.T. and D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Han, S. Economic Feasibility of V2G Frequency Regulation in Consideration of Battery Degradation. Energies 2013, 6, 748–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempton, W.; Tomić, J. Vehicle-to-Grid Power Fundamentals: Calculating Capacity and Net Revenue. J. Power Sources 2005, 144, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Kester, J.; Noel, L.; Zarazua de Rubens, G. The Neglected Social Dimensions to a Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) Transition: A Critical and Systematic Review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.; Kempton, W. Integration of Renewable Energy into the Transport and Electricity Sectors through V2G. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 3578–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement-Nyns, K.; Haesen, E.; Driesen, J. The Impact of Charging Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicles on a Residential Distribution Grid. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2010, 25, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, J.; Kang, C.; Zhang, X. Coordinated Planning of EV Charging Stations and Renewable Energy Resources in Distribution Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 31, 3607–3616. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Shen, Z. Service Failure Risk Assessment and Service Improvement of Self-Service Electric Vehicle. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushar, W.; Yuen, C.; Mohsenian-Rad, H.; Saha, T.; Poor, H.V.; Wood, K.L. Transforming Energy Networks via Peer-to-Peer Energy Trading: The Potential of Game-Theoretic Approaches. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2018, 35, 90–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Bisschop, R.; Niu, H.; Huang, X. A Review of Battery Fires in Electric Vehicles. Fire Technol. 2020, 56, 1361–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chruzik, K.; Graboń-Chałupczak, M. The Concept of Safety Management in the Electromobility Development Strategy. Energies 2021, 14, 2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Niu, H.; Liu, J.; Huang, X. Layer-to-Layer Thermal Runaway Propagation of Open-Circuit Li-ion Batteries: Effect of Ambient Pressure. J. Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). NFPA 855: Standard for the Installation of Stationary Energy Storage Systems; NFPA: Quincy, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 15118-1:2019; Road vehicles—Vehicle to grid communication interface—Part 1: General Information and Use-Case Definition. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Moghadasi, N.; Collier, Z.A.; Koch, A.; Slutzky, D.L.; Polmateer, T.L.; Manasco, M.C.; Lambert, J.H. Trust and Security of Electric Vehicle-to-Grid Systems and Hardware Supply Chains. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 225, 108565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J. Review of Electric Vehicle Charger Cybersecurity Vulnerabilities, Potential Impacts and Defenses. Energies 2022, 15, 3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Innovation Outlook: Smart Charging for Electric Vehicles; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2019; Available online: https://www.irena.org/publications (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Kumar, P.; Channi, H.K. A Comprehensive Review of Vehicle-to-Grid Integration in Electric Vehicles: Powering the Future. Energy Rep. 2024, 10, 13482–13501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z. Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) Charging and Discharging: Two-Layer Optimization Approach. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaque, M.A.; Rahman, M.; Alzoubi, Y.I.; Alotaibi, F.S.; Alshahrani, A. Cybersecurity in Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) Systems: A Systematic Review. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.15730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P. Vehicle-to-Grid: Technology, Charging Station, Power and Communication Interface Considerations. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkika, A.V.; Panteli, M.; Kyriakides, E.; Ziomas, A. A Risk Assessment Methodology for Supporting Decision Making Regarding the Resilience Enhancement of Power Networks. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2024, 37, 100711. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).