Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of low-temperature disintegration of Chlorella vulgaris using solidified carbon dioxide (SCO2) on the efficiency of anaerobic digestion of microalgae biomass. The novelty of this study resides in the pioneering application of SCO2 for the pretreatment of C. vulgaris biomass to enhance methane fermentation. This approach integrates mechanical disruption of cell walls with improved solubilization of organic fractions at low temperatures, providing an innovative and energy-efficient strategy to boost biomethanogenesis performance. This study was carried out in four stages, including characterisation of substrate properties, evaluation of organic compound solubilization following SCO2 pretreatment, and fermentation under both batch and continuous conditions. Analysis of dissolved COD and TOC fractions revealed a significant increase in the bioavailability of organic matter as a result of SCO2 application, with the highest degree of solubilization observed at a SCO2/C. vulgaris biomass volume ratio of 1:3. In batch reactors, CH4 yield increased significantly to 369 ± 16 mL CH4/g VS, methane content in biogas reached 65.9 ± 1.0%, and kinetic process parameters were improved. Comparable enhancements were observed in continuous fermentation, with the best scenario yielding 243.4 ± 9.5 mL CH4/g VS. Digestate analysis confirmed more efficient degradation of organic fractions, and the stability of methanogenic consortia was maintained, with only moderate changes in the relative abundance of the main groups (Methanosarcinaceae, Methanosaeta). Energy balance calculations indicated a positive net effect of the process. This study represents a pioneering application of SCO2 pretreatment in the context of microalgal biomass and highlights its high potential for intensifying anaerobic digestion.

1. Introduction

Due to their rapid growth and high content of organic compounds, microalgae are among the most promising substrates for a wide range of biotechnological processes, particularly for biofuel production [1]. Their chemical composition renders them potentially efficient substrates for biogas production via anaerobic digestion, especially in the context of advancing sustainable energy technologies and implementing circular economy principles [2]. Importantly, microalgae do not compete with food crops for agricultural land or freshwater resources, further enhancing their attractiveness as an alternative renewable energy source [3].

Despite their high bioenergy potential, confirmed by numerous studies, the application of microalgal biomass in methane fermentation faces significant technological challenges [4]. Among the most critical are the low carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio and the inherent resistance of microalgal cell structures to degradation, which reduces substrate susceptibility to bioconversion into gaseous energy carriers [5]. These factors can negatively affect both the stability of the anaerobic digestion process and the overall methane yield [6].

The susceptibility of individual algal species and taxonomic groups to anaerobic fermentation is closely linked to cell wall structure [7]. In particular, microalgae of the genus Chlorella possess highly resistant cell walls composed of multilayered polysaccharides, often containing cellulose and sporopollenin [8]. This structural robustness limits microbial access to intracellular organic compounds, constraining the efficiency of all stages of methane fermentation [9]. Consequently, many studies emphasise the need for effective pretreatment strategies [10]. Prior to anaerobic biodegradation, microalgal biomass has been subjected to various disintegration and pretreatment methods aimed at breaking down cell walls and enhancing the bioavailability of organic matter [11]. Techniques employed include ultrasonic, thermal, chemical (e.g., alkalis or acids), enzymatic, and mechanical approaches such as high-pressure homogenization [12]. Each method presents specific advantages and limitations, with many being associated with high energy demands or potential environmental impacts [9].

The biochemical processes occurring during anaerobic digestion are strongly influenced by the interactions between substrate characteristics and the structure and activity of hydrolysing, acidogenic, and methanogenic microbial communities [13]. Pretreatment strategies promote hydrolysis of polysaccharides and proteins, depolymerization of lignocellulosic materials, and increased availability of organic compounds, including monosaccharides and amino acids, within the digester environment [14]. Enhanced availability of readily degradable organic compounds accelerates the production of short-chain fatty acids (VFAs), particularly acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which serve as direct substrates for acetoclastic methanogens [15].

The Methanosarcina and Methanosaeta genera exhibit distinct metabolic traits that dictate their responses to fluctuations in substrate availability. Methanosaeta is characterised by a high affinity for acetate and a stable, slow metabolic rate, allowing it to dominate environments with low acetate concentrations [16]. In contrast, Methanosarcina demonstrates greater metabolic versatility, capable of utilising both acetate and H2/CO2 [17]. In this context, H2 functions as an electron donor and CO2 as an electron acceptor and carbon source, enabling Methanosarcina to produce CH4 even under acetate-limited conditions [18]. This metabolic flexibility allows the genus to persist across diverse environments and maintain methane production under variable substrate availability. Moreover, it tolerates higher acetate concentrations and environmental fluctuations, providing an advantage following pretreatments that elevate the concentration of readily available substrates [19].

Pretreatment can also result in the release of inhibitory compounds, such as ammonia, phenolics, or VFAs at elevated concentrations [20]. High ammonia levels suppress the activity of acetyl- and formyl-transferase enzymes, disproportionately inhibiting Methanosaeta relative to Methanosarcina [21]. Additionally, alterations in pH and osmolality induced by pretreatment may selectively restrict the growth of more sensitive methanogenic groups, thereby shifting community composition toward the more resilient and metabolically versatile Methanosarcina [22]. A thorough understanding of these biochemical mechanisms enables prediction of pretreatment strategies that support stable methane production and optimal methanogenic community structure, which is critical for the design and optimisation of industrial-scale anaerobic digestion systems.

In recent years, the innovative approach of disintegrating biomass at low temperatures using solid carbon dioxide (SCO2) has attracted growing interest [23]. This technique, based on the cyclic freezing and thawing of biological material, induces structural damage to cell membranes and walls through the formation of ice crystals and rapid volumetric changes [24]. In various types of sewage sludge, SCO2 treatment has been shown to enhance the release of organic matter into the dissolved phase, improve biodegradability, and increase methane production during anaerobic digestion [25,26]. Considering the structural similarities and physicochemical characteristics of Chlorella sp. microalgal biomass to sludge with high moisture and organic matter content, SCO2 disintegration appears to be a justified and potentially effective strategy for enhancing the efficiency of methane fermentation of this substrate.

To date, no studies have reported the use of SCO2 for pretreating microalgal biomass prior to anaerobic digestion, making this research pioneering. Given the properties of this organic substrate and the positive outcomes observed in sewage sludge disintegration across various origins and characteristics, it is both relevant and necessary to assess the feasibility of applying SCO2 pretreatment to microalgae before anaerobic biodegradation.

This study represents a pioneering effort to develop environmentally sustainable and energy-efficient strategies for the pretreatment of microalgal biomass. The application of SCO2 as a disintegration agent for organic substrates prior to anaerobic digestion has not been previously explored. This approach integrates high efficiency, environmental safety, and operational simplicity. Utilising SCO2 to generate intracellular pressure differentials and induce microcracks during sublimation constitutes an innovative, waste-free, and potentially scalable strategy for enhancing the bioconversion of microalgal biomass to methane. Beyond addressing a clear research gap, this work highlights a novel avenue for sustainable bioenergy development, combining CO2 valorisation with renewable energy production within a circular economy framework.

The primary aim of this study was to investigate the effects of SCO2 pretreatment of C. vulgaris microalgal biomass on the efficiency of its anaerobic digestion. Specifically, this study assessed the impact of this disintegration method on the concentration of organic compounds in the dissolved phase, the kinetics of biogas production in batch reactors, and the overall methane yield in continuous bioreactors. In addition, the taxonomic composition of the anaerobic microbial community and the quality of the resulting digestate were evaluated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Organisation of the Experiment

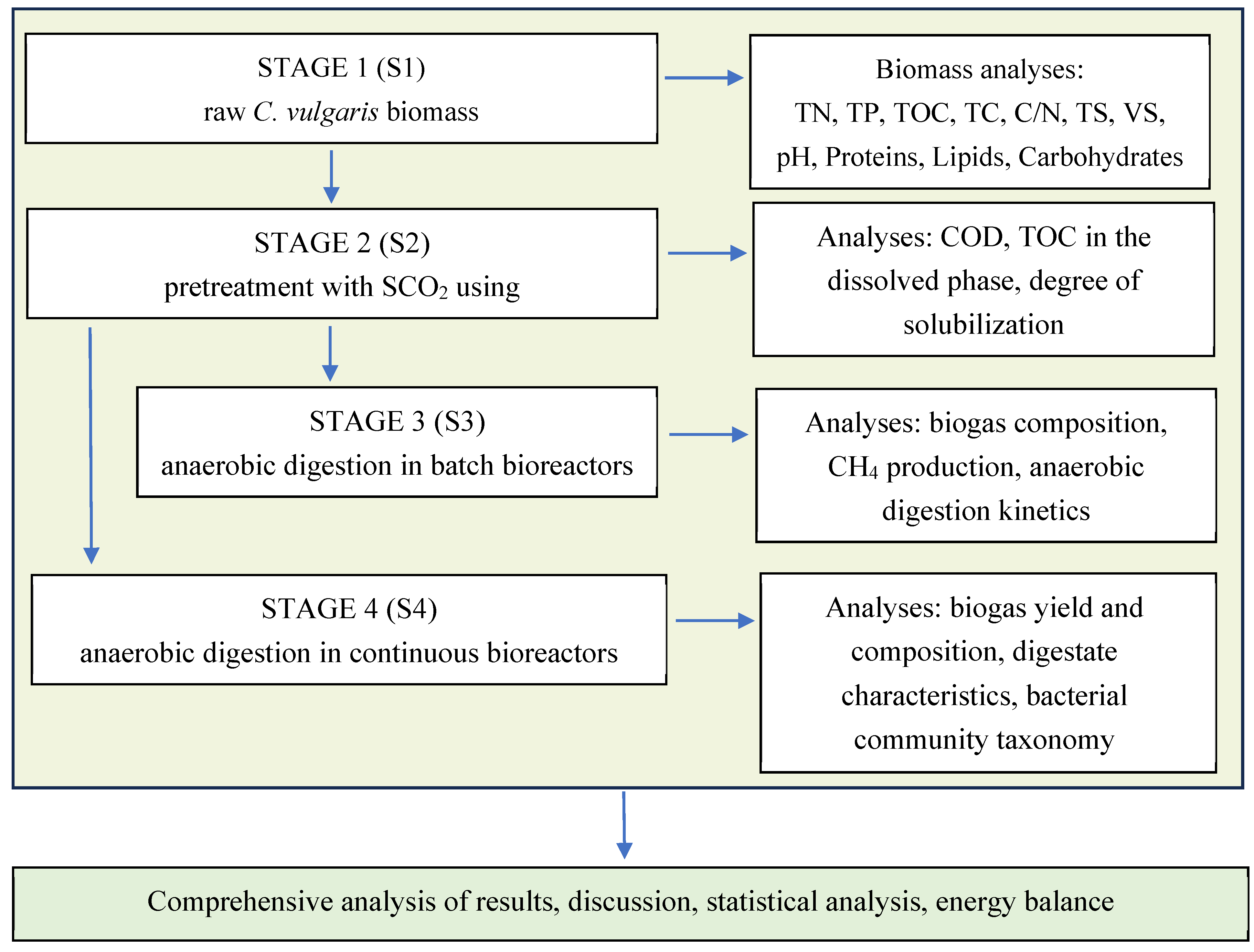

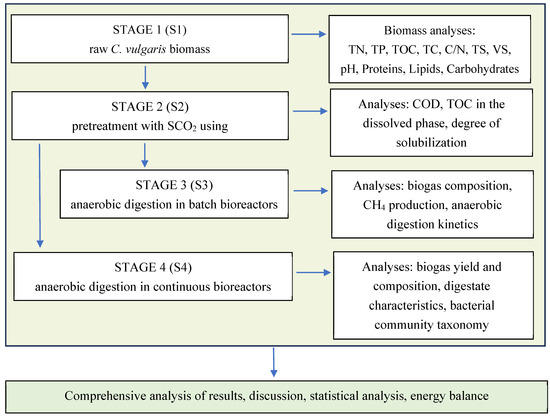

This study was conducted in four sequential stages (S). In Stage 1 (S1), a physicochemical characterisation of the organic substrate, namely Chlorella vulgaris microalgae, was performed. In Stage 2 (S2), the C. vulgaris biomass was subjected to low-temperature pretreatment with SCO2, followed by analyses of organic compounds (COD, TOC) to allow indirect assessment of process efficiency.

In Stage 3 (S3), both raw and SCO2-pretreated C. vulgaris biomass were subjected to anaerobic digestion in respirometric batch reactors. In this stage, biogas composition, methane (CH4) yield, and production kinetics were evaluated. Stages S2 and S3 were divided into six experimental variants (V) according to the volume ratio of SCO2 to C. vulgaris biomass: control without SCO2 (V0), 1:10 (V1), 1:5 (V2), 1:3 (V3), 1:2.5 (V4), and 1:2 (V5). The SCO2/biomass ratios were selected based on literature data [27,28] and previous studies by the authors [25,26].

Based on the results obtained in S2 and S3, the most efficient technological variants of low-temperature SCO2 disintegration were selected and subsequently tested in Stage 4 (S4) in continuous fermentation bioreactors. During this stage, the quantity and composition of the biogas, characteristics of the digestate, and the taxonomic composition of the anaerobic microbial community were analysed. A schematic overview of the study design is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Organisation chart of the experimental, analytical and descriptive work.

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. C. vulgaris Biomass

Microalgae biomass of the species C. vulgaris was grown internally in the photobioreactor systems (PBR) of the Department of Environmental Engineering of the University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, Poland [29]. Primary C. vulgaris biomass inocula (UTEX 2714) were obtained from the Culture Collection of Algae, University of Texas, Austin, TX, USA, and cultivated in hybrid photobioreactors (2.0 m3) fed with a 1:1 ratio of digestate liquid fraction to tap water [30]. After the cultivation process, the biomass of C. vulgaris was separated from the culture medium by centrifugation at 40,000 rpm and a liquid flow rate of approx. 35 L/h (Z41 model CEPA flow-through centrifuge, CEPA LEA Lab, Ingersheim, Germany). In S2 (pretreatment with SCO2), the biomass of C. vulgaris was characterised by a TS content of about 5%. The characteristics of the C. vulgaris biomass used in the experiments are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the biomass of C. vulgaris used in the experiments.

2.2.2. Solid Carbon Dioxide—SCO2

The SCO2 used in this study was obtained commercially from the manufacturer (Sopel Sp. z o.o., Białystok, Poland) in the form of granules with a diameter of 3.0 ± 1.0 mm. It is a natural product that is approved for contact with food, tasteless, odourless, non-toxic and non-flammable [24].

2.2.3. Anaerobic Sludge Inoculum

In the experiments on anaerobic digestion of the tested C. vulgaris biomass, anaerobic sludge from an anaerobic digestion reactor with an active capacity of 7300 m3 located at the wastewater treatment plant in Białystok, Poland, was used as inoculum. This reactor operates with an organic loading rate (OLR) of 1.9 to 2.2 gVS/L·day, a hydraulic retention time (HRT) of 20–22 days and a temperature of 35–37 °C. The properties of the anaerobic sludge inoculum are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the anaerobic sludge used for anaerobic digestion.

2.3. Experimental Sites

2.3.1. Pretreatment of C. vulgaris Biomass with SCO2

Pretreatment of C. vulgaris biomass was carried out in open reactors (JLT 6, VELP Scientifica, Milan, Italy) [25]. A total of 200 mL of raw C. vulgaris biomass (20 °C) was mixed with the amount of SCO2 assumed for a particular experimental variant (50 rpm). After pretreatment. the C. vulgaris biomass was transferred to the fermentation bioreactors once the SCO2 was fully sublimated and the sample temperature reached approximately 20 °C.

2.3.2. Respirometric Bioreactors for Batch Fermentation

The methanogenic potential was evaluated based on the amount of CH4 produced, which was measured using an automated methane potential analyser system (AMPTS II, BPC Instruments AB, Lund, Sweden) [31]. Anaerobic digestion was carried out at a constant temperature of 37 ± 1 °C in glass vessels with a total capacity of 500 mL equipped with independent, sequentially controlled, bladeless vertical stirrers operating at 100 rpm for 30 s every 5 min. At the beginning of the experiment, 200 mL of anaerobic sludge inoculum was added to each reactor, followed by the corresponding portion of C. vulgaris biomass. The initial organic loading rate (OLR) was set at 5.0 ± 0.3 gVS/L. Anaerobic conditions were achieved by flushing the sludge-substrate mixture with nitrogen gas (flow rate 100 L/h for 3 min). Daily biogas production was automatically monitored using the AMPTS II system control software, which recorded the volume of CH4 produced under standard conditions (101.3 kPa. 0 °C. 0% humidity). This measurement continued until five consecutive readings differed by less than 1%, indicating that the decomposition of the organic compounds was complete. The production of biogas and methane (CH4) was expressed as the amount of gas (in mL) per gramme of organic matter (gVS) fed into the reactor. Each result was corrected for the amount of CH4 endogenously produced by the inoculum of the anaerobic sludge itself. The CO2 produced during digestion was captured in a 100 mL sorption module with 3M NaOH, ensuring a removal efficiency of over 98%.

2.3.3. Continuous Bioreactor Studies

The methane fermentation process in continuous reactors was carried out using AMPTS II systems (Bioprocess Control, Lund, Sweden), which allow automatic measurement of the amount of biogas produced. The experiment was carried out in reactors with a total capacity of 2.5 L, equipped with vertical, three-blade mechanical agitators operating at 100 rpm and with a cycle of 10 min on and 10 min off. At the beginning of this study, the reactors were inoculated with 2.0 L (active volume) of anaerobic sludge from the digesters of the municipal wastewater treatment plant in Białystok (Table 2). Every day 100 mL of digested sludge was removed from the process system and replaced with an equal volume of fresh feedstock. Considering the characteristics of the biomass of C. vulgaris (TS at approximately 5% of the raw biomass, VS amounting to approx. 88% TS), about 4.4 g VS were fed daily to the bioreactors in operation. This means that the ORL was around 2.2 g VS/L·day, which is typical for this technological parameter. Anaerobic digestion lasted 60 days which corresponds to three times the hydraulic retention time. To ensure anaerobic conditions the mixture of inoculum and raw material was flushed with nitrogen for 5 min during preparation. The reactors were also equipped with a carbon dioxide removal module and the resulting biogas was channelled into a 200 mL tank containing a 3 molar NaOH solution.

2.4. Analytical Methods

The efficiency of biogas production and the content of methane (CH4) in the sample (S2) were determined with respirometric reactors equipped with an ex situ CO2 absorption module using a 3-molar NaOH solution as absorption liquid. Biogas production was monitored in a system without this module. To evaluate the qualitative characteristics of the biogas chromatographic analyses were also performed using an Agilent 7890 A gas chromatograph (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). The biogas samples were taken directly from the reactors using a sealed 20 mL syringe. Argon and helium were used as carrier gases in the chromatograph at a flow rate of 15 mL/min. Analyses were performed on Hayesep Q (80/100 mesh). Porapak Q (80/100 mesh) columns and a molecular sieve module (60/80 mesh) operated at 70 °C. The injection and detection temperatures were 150 °C and 250 °C, respectively. Parameters such as chemical oxygen demand (COD), total nitrogen (TN) and total phosphorus (TP) in the dissolved phase of the medium were determined spectrophotometrically (Hach DR 6000, Düsseldorf, Germany) after sample digestion in a HT200S high-temperature thermostat using HSD (High-Speed Digestion) technology.

The contents of total carbon (TC), total organic carbon (TOC), inorganic carbon (IC) and total nitrogen (TN) were determined by combustion oxidation and chemiluminescence using a TOC-L CPH/CPN analyser with a TNM-L accessory (Shimadzu Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Protein concentration was determined using the TNx6.25 protein conversion factor. Reducing carbohydrates were determined spectrophotometrically using anthrone reagent (0.2 g anthrone/100 mL concentrated H2SO4). Samples were pretreated by acid hydrolysis of polysaccharides (1 M H2SO4, 100 °C, 1 h), then cooled and neutralised to pH 4–5. Anthrone reagent was added, and the mixture was heated in a water bath at 95–100 °C for 8–10 min. Absorbance was measured at 600 nm at a DR 2800 spectrophotometer (Hach-Lange GmbH, Düsseldorf, Germany), where a stable and linear response was obtained for the examined concentration range. The calibration curve, prepared using standard glucose solutions was linear, ensuring accurate quantification. Lipid analyses were performed using a Büchi extraction device (B-811, Büchi AG, Flawil, Switzerland) according to the Soxhlet method. The concentrations of volatile fatty acids (VFA, expressed as FOS) and buffer capacity (TAC) were measured using a TitraLab AT1000 Series titrator (Hatch, Mississauga, ON, Canada) to calculate the FOS/TAC ratio. To assess the dissolution of the organic matter and the degree of its solubilisation the samples for TOC and COD analysis were first centrifuged for 3 min at 9000 rpm in a ROTINA 380 centrifuge and then filtered through 1.2 µm membranes. After drying at 105 °C the TC, TOC and TN contents were determined using a Flash 2000 analyser (Thermo Scientific, Delft, The Netherlands). The pH value was measured with a pH metre (Model 1000 L, VWR International, Radnor, PA, USA). The content of solids (TS), minerals (MS) and organic substances (VS) was determined gravimetrically.

2.5. Molecular Methods

Fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) was used to identify the anaerobic microbial communities. Four molecular probes were used for the analysis: a universal probe for bacteria (EUB338) [32] and archaea (ARC915) [33] and two probes for specific methanogen groups—MSMX860 for Methanosarcinaceae and MX825 for Methanosaeta [34]. Observations were performed using an epifluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a 100× objective and providing a total magnification of 1000×. The cell number of each microbial group was estimated from DAPI staining and quantitative analysis was performed using ImageJ (version 1.54f) software developed by the National Institutes of Health in collaboration with the Laboratory for Optical and Computational Instrumentation (LOCI) (University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA) [35].

2.6. Calculation Methods

The biogas production rate (r) and the kinetic reaction constants (k) were calculated for all experimental variants based on the experimental data using nonlinear regression in Statistica 13.3 PL (Statsoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). An iterative regression method was used in the analysis in which a function is replaced by a linear approximation to the estimated parameters at each iteration step. The contingency coefficient φ2 was used to assess the fit of the model. A satisfactory fit was considered to exist if the value of φ2 was less than 0.2.

The energy consumption (Es) [Wh] was estimated from formula (1) using the power (P), mass (M) and efficiency (Y) data of the dry ice generator (SCO2) for the P3000 pelletiser model (Cold Jet, Loveland, CO, USA) [36]:

where

Es = (P_SCO2 · M_SCO2)/Y_SCO2

- P_SCO2—device power (W);

- M_SCO2—mass of the SCO2 produced (kg);

- Y_SCO2—efficiency of the SCO2 appliance (kg/h).

The amount of output energy (E_out) resulting from methane production was determined according to Equation (2):

where

E_out = Y_CH4 · CV_CH4 · VS (FM)_C. vulgaris

- Y_CH4—methane efficiency (L/kgVS. L/kgFM);

- CV_CH4—calorific value of methane (Wh/L);

- VS_C. vulgaris—VS of the C. vulgaris biomass used (kgVS);

- FM_C. vulgaris—FM of the C. vulgaris biomass used (kgVS).

The net energy output (E_nout) was determined as the difference between the energy obtained in the tested variant and the reference energy (variant V1—control sample) according to Equation (3):

E_nout = E_out(Vx) − E_out(V1)

The final net energy balance (E_net) was calculated according to Equation (4) as the difference between net energy production and energy consumption:

E_net = E_nout − Es

Equations (5) and (6) presented below are used to determine the degree of dissolution of the COD and TOC indicators, expressed as a percentage [29,30]. In these equations, the symbols sCOD_S0 and sTOC_S0 denote the concentration of soluble COD and TOC fractions before SCO2 pretreatment [mg/L], while sCOD_S1 and sTOC_S1 refer to their values after the low-temperature disintegration process. COD_T0 and TOC_T0 represent the total concentration of the relevant parameters in the biomass before SCO2 pretreatment [mg/L].

Degree of solubilization (COD) = [(sCODS1 − sCODS0)/(CODT0 − sCODS0)] × 100

Degree of solubilization (TOC) = [(sTOCS1 − sTOCS0)/(TOCT0 − sTOCS0)] × 100

The efficiency coefficient of anaerobic digestion, i.e., the ratio between the organic load removed and the organic load introduced into the reactor (7), was determined using the following equation:

where ηAD—anaerobic digestion efficiency (%); VSin—VS content in the influent (g/kg); VSout—VS content in the digested sludge (g/kg); ρin—substrate density (kg/L); ρout—digested sludge density (kg/L); Qin—daily volume of substrate (L/day); Qout—daily volume of digested sludge discharged (L/day).

The efficiency of biogas/CH4 production in relation to the amount of removed load VS was calculated according to Equation (8):

where —yield of biogas/CH4 produced in relation to the VS removed (L/kgVSremoved); Vb/CH4—volume of biogas/CH4 produced from the VS load fed into the reactor (L); SVSin—content of VS in the substrate (g/kg); SVSout—content of VS in the digested sludge (g/kg); Qin—volume of substrate fed into the reactor (L); Qout—daily volume of digested sludge discharged (L).

The theoretical methane yield (TBMP) from C. vulgaris was calculated based on its macromolecular composition (proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates) and elemental content (C, H, O, N), according to the Buswell and Mueller Equation (9) [37], assuming complete anaerobic mineralization of the organic matter to CH4 and CO2:

The number of moles of CH4 and CO2 produced per mole of substrate was calculated according to Equations (10) and (11) as follows:

where , , , and represent the molar fractions of C, H, O, and N in the substrate, respectively.

The mass fractions of C, H, O, and N for each macromolecular fraction were adopted based on values commonly reported in the literature and widely used in anaerobic fermentation modelling [38,39], specifically, proteins (C = 53%, H = 7%, O = 23%, N = 16%), lipids (C = 77.1%, H = 11.9%, O = 11.0%), and carbohydrates (C = 40.0%, H = 6.67%, O = 53.33%, N ≈ 0%).

The molar amounts of individual elements were calculated according to Equations (12)–(15):

By substituting these values into the Buswell equation, the number of moles of CH4 and CO2 produced per gram of dry biomass was obtained. The corresponding gas volumes under standard conditions (0 °C, 101.3 kPa) were calculated assuming that 1 mol of gas occupies 22.414 L. The specific methane yield was expressed per unit of dry matter (TS) (16) and volatile solids (VS) (17):

The uncertainty of the calculated TBMP values was estimated based on error propagation associated with variability in macromolecular composition (±SD), the adopted elemental mass fractions, and the analytical uncertainty of TC and TN measurements. The resulting cumulative uncertainty was ±8–12%, which is consistent with values reported in the literature for theoretical estimates of methane potential [39].

2.7. Statistical Methods

The experiments were carried out in triplicate for each variant. Statistica 13.3 PL software (Statsoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA) was used to statistically analyse the results. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of the data distribution. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyse the differences between groups and Levene’s test for homogeneity of variance was used. Tukey’s HSD post hoc test was used to identify significant differences between pairs of groups. The value of α = 0.05 was considered the level of statistical significance.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterisation of the C. vulgaris Biomass—S1

The total solids (TS) content of the tested C. vulgaris biomass was 5.0 ± 0.4%, with volatile solids (VS) comprising 88.2 ± 1.3% of TS (Table 1). This high organic matter content is typical for this substrate and indicates substantial potential for anaerobic degradation [40]. Total carbon (TC) and total organic carbon (TOC) were 461 ± 39 mg/g TS and 423 ± 22 mg/g TS, respectively, reflecting a significant pool of biodegradable organic compounds that serve as an energy source for microorganisms involved in subsequent stages of anaerobic digestion, including methanogenic archaea [41].

The lipid content of the biomass was 15.2 ± 0.7% TS, which is favourable for the energy potential of the substrate, as lipids are calorie-rich compounds whose degradation enhances methane yield when the substrate is accessible to microorganisms [42]. Total sugar content was 37.2 ± 2.3% TS, which positively correlates with methanogenesis, as simple sugars and polysaccharides are readily fermented by hydrolytic and fermentative microorganisms [43].

The biomass was also rich in total nitrogen (TN, 40.2 ± 1.8 mg/g TS) and total phosphorus (TP, 18.4 ± 1.7 mg/g TS) (Table 1), supporting fermentative microbial activity. However, excessive nitrogen can lead to ammonia inhibition during anaerobic digestion [44]. The C/N ratio of the analysed biomass was 10.5 ± 0.2, below the generally recommended range of 20–30 for optimal methane fermentation [45]. Low C/N ratios can cause ammonia overproduction during protein degradation, inhibiting methanogenic archaea, reducing methane yield, promoting accumulation of volatile fatty acids, and acidifying the system [46,47]. Ammonia concentrations above 1.5–3 g/L can significantly suppress methanogenic activity [47].

To mitigate this risk and achieve a more favourable C/N balance, co-fermentation of microalgal biomass with carbon-rich substrates (e.g., lignocellulosic waste, biodegradable food waste, sewage sludge) is commonly recommended [48]. For example, Zhang et al. [49] reported that co-fermentation of C. vulgaris with potato processing waste and glycerol increased methane production by up to 128% compared to mono-fermentation. Similarly, Wang et al. [50] co-fermented Chlorella sp. with pig manure in long-term fed-batch systems, achieving an average methane production of 190 mL/g VS_fed, demonstrating the practical feasibility of integrating these substrates.

However, a major limitation in the direct use of C. vulgaris as a substrate for anaerobic digestion is its cell wall structure. These walls are thick, multilayered and often contain degradation-resistant polysaccharides and sporopollenin, which makes it difficult for hydrolytic enzymes to access the intracellular substrate [51]. In practice, this leads to a low level of organic substances degradation and limited biogas production unless the biomass is first subjected to effective disintegration [52]. Such studies were carried out by Park et al. [53], among others, who pretreated waste biomass of the microalgae C. vulgaris with ultrasound in the range of 5–200 J/mL. During batch fermentation, an increase in biogas production and degradation rate was observed. Compared to the sample that was not treated with ultrasound, biogas production increased by 90% at an energy dose of 200 J/mL [53]. In turn, Passos et al. [54] showed that the use of microwaves to treat C. vulgaris biomass increased the methane potential by approximately 21% compared to the control sample, with the solubilisation of the organic matter (VS solubilisation) increasing significantly after only a few minutes of treatment. In the study by Elalami et al. [55], thermal pretreatment of C. vulgaris biomass (120 °C, 40 min) increased the soluble carbohydrates by up to six times. and CH4 production increased by about 93%. Enzymatic and biological methods also show great potential, namely the use of cellulase bacteria by Mahdy et al. [56] to pretreat C. vulgaris resulted in an 87% increase in methane. and protease contributed to an almost sixfold increase.

3.2. Indirect Indicators of the Efficiency of Pretreatment—S2

To evaluate the effectiveness of the degradation of C. vulgaris biomass with SCO2, the changes in COD and TOC concentrations in the aqueous phase after pretreatment were analysed. This led to a significant increase in the concentrations of the monitored organic compounds in the liquid phase. The results of the changes in COD and TOC concentrations in the dissolved phase and the degree of solubilisation of these compounds are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

COD and TOC values and the degree of solubilisation achieved as a function of the SCO2 pre-treatment variant used.

In the control sample (V0), which was not treated with SCO2, the concentrations of dissolved COD and TOC were 392 ± 34 mg O2/L and 153 ± 19 mg/L, respectively (Table 3). The application of SCO2 resulted in a statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05) and dose-dependent increase in both COD and TOC in the dissolved phase. As the SCO2/C. vulgaris biomass ratio increased from 1:10 (V1) to 1:3 (V3), the concentration of dissolved organic compounds and the degree of solubilization increased systematically and significantly (p ≤ 0.05).

In variant V1, the dissolved COD and TOC reached 2953 ± 197 mg O2/L and 1209 ± 98 mg/L, corresponding to solubilization levels of 6.0 ± 0.3% and 3.2 ± 0.6%, respectively. Increasing the ratio to 1:5 (V2) raised these values to 5412 ± 303 mg O2/L (11.7 ± 0.8%) and 3904 ± 204 mg/L (16.3 ± 1.2%). The most pronounced effect was observed at 1:3 (V3), with dissolved COD and TOC of 6487 ± 549 mg O2/L and 4612 ± 277 mg/L, yielding solubilization levels of 14.2 ± 0.9% and 19.7 ± 0.8%, respectively (Table 3). Further increases in the SCO2 proportion to 1:2.5 (V4) and 1:2 (V5) did not result in statistically significant changes. Concentrations were similar in these variants: 6504 ± 492 mg O2/L and 6511 ± 438 mg O2/L for COD, and 4980 ± 360 mg/L and 5010 ± 392 mg/L for TOC. Corresponding solubilization levels also remained nearly constant (V4: 14.3 ± 0.8% COD, 14.3 ± 0.7% TOC; V5: 21.5 ± 1.7% COD, 21.6 ± 1.6% TOC).

These observations are consistent with previous studies on SCO2 disintegration of sludge. Montusiewicz et al. [57] reported that freezing a mixture of primary and biological sludge at −25 °C more than doubled soluble COD and increased nutrient release. Zawieja [28] showed that SCO2 disintegration of excess sludge enhanced hydrolysis, increasing dissolved COD, TOC, and volatile fatty acids, with optimal results at a SCO2:sludge ratio of 0.55:1. Similarly, Kazimierowicz et al. [58] observed that increasing the SCO2 dose beyond 0.3 did not significantly affect COD concentrations, while nutrient release improved. Earlier work by the authors [25,26] confirmed that low-temperature treatment of granular sludge with SCO2 increases dissolved COD, ammonium, and phosphate concentrations up to a threshold ratio, beyond which no further benefits are observed.

The results indicate that a SCO2/C. vulgaris biomass ratio of 1:3 represents the saturation point for effective solubilization of organic compounds. Further increases in SCO2 do not significantly enhance solubilization and could unnecessarily increase operational costs [6,25]. The mechanism underlying this pretreatment involves the synergistic effects of extreme low temperature and sublimation, which generate osmotic and mechanical stresses that disrupt microalgal cell structures and release cytoplasmic contents [59]. The observed higher solubilization of TOC relative to COD in variants V2–V5 may indicate partial conversion of complex macromolecules (e.g., polysaccharides, lipids) into smaller, more soluble fractions, potentially enhancing subsequent processing such as methane fermentation, enzymatic hydrolysis, or biochemical production [60].

3.3. Anaerobic Respirometry Measurements—S3

Respirometric investigations showed that the use of SCO2 in the pre-treatment of C. vulgaris biomass had a significant (p ≤ 0.05) positive effect on the efficiency of anaerobic digestion. This is confirmed by the biogas and CH4 yields observed in the subsequently tested experimental variants and by the recorded increase in the kinetic parameters of the process. Based on the theoretical calculations of biogas production and considering the organic fraction content (VS) of 88.2 ± 1.3% TS (0.882 g VS/g TS), the maximum theoretical CH4 yield was 735 ± 88 mL CH4/g VS, while CO2 reached 200 ± 20 mL CO2/g VS. The total theoretical biogas production (CH4 + CO2) was 936 ± 110 mL/g VS, with the volumetric CH4 content in the biogas estimated at approximately 78.6%.

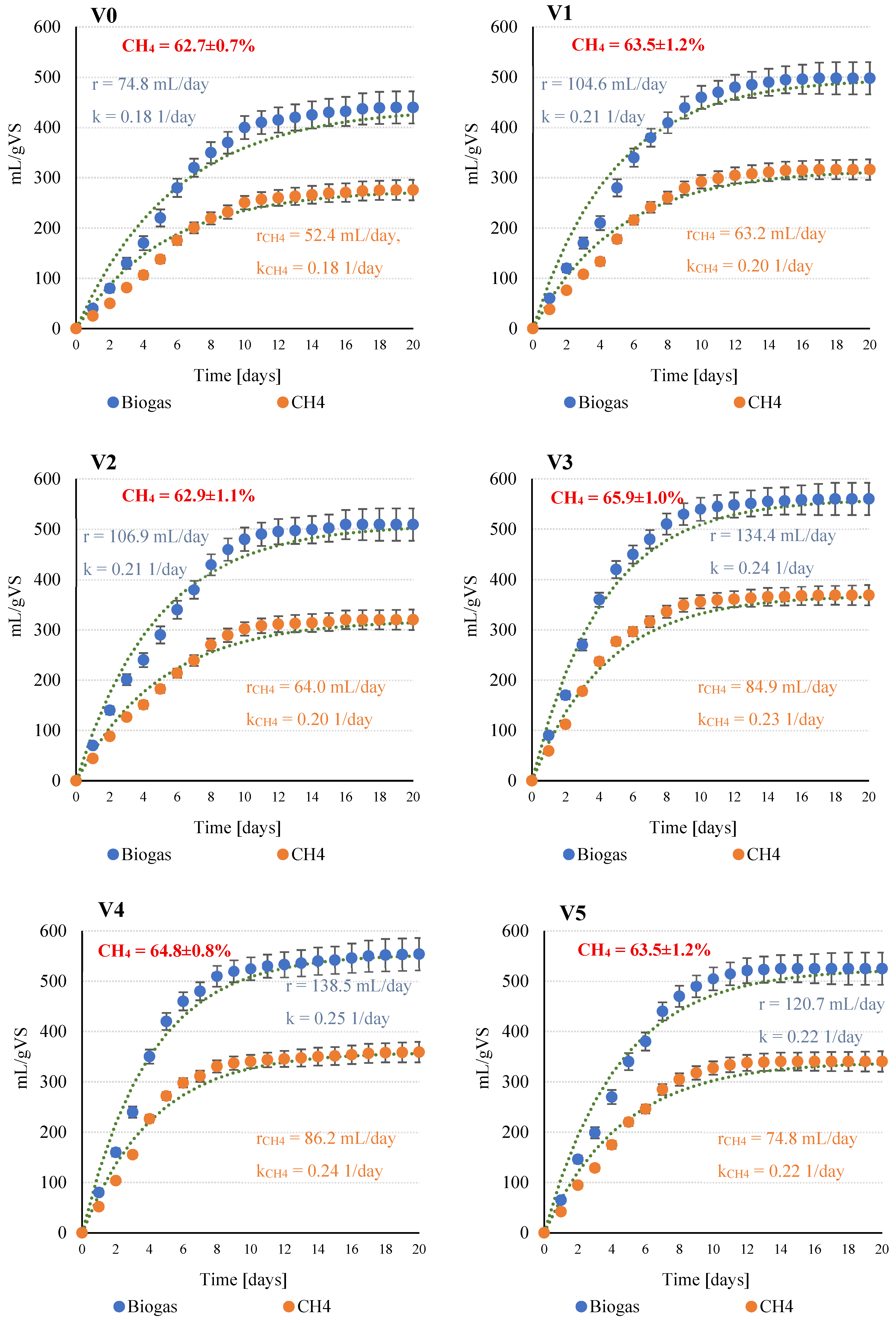

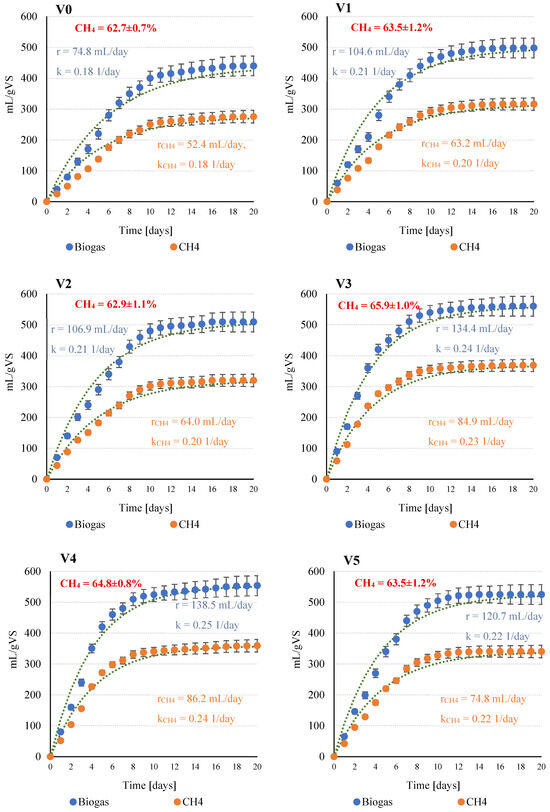

The course of anaerobic digestion (AD) in the experimental variants and the corresponding kinetic model curves are shown in Figure 2. The control variant (V0), without SCO2 pretreatment, exhibited the lowest biogas and methane yields, with biogas production of 440 ± 32 mL/g VS (r = 74.8 mL/day, k = 0.18 1/day) and methane production of 276 ± 20 mL CH4/g VS (rCH4 = 52.4 mL CH4/day, kCH4 = 0.18 1/day). Introduction of SCO2 in V1 significantly (p ≤ 0.05) increased biogas and methane yields to 498 ± 33 mL/g VS and 316 ± 21 mL CH4/gVS, respectively, with improved kinetic parameters (kCH4 = 0.201 1/day, rCH4 = 63.2 mL CH4/day). In V2 (1:5 ratio), the upward trend continued, with biogas yield reaching 509 ± 20 mL/g VS and comparable kinetic parameters.

Figure 2.

Anaerobic digestion process and kinetic parameters obtained as a function of the experimental variant tested (V0–V5).

The highest performance was observed in V3 (1:3 ratio), where biogas and CH4 yields were 560 ± 24 mL/g VS and 369 ± 16 mL CH4/g VS, respectively. Corresponding kinetic parameters were also maximal (kCH4 = 0.231 1/day, rCH4 = 84.9 mL CH4/day), indicating enhanced substrate bioavailability and accelerated methanogenesis. Methane content in the biogas reached 65.9 ± 1.0%, the highest among all tested variants. Variant V4 confirmed the efficacy of the SCO2 pretreatment, with biogas and methane yields of 554 ± 27 mL/g VS and 359 ± 17 mL CH4/g VS, respectively, and kinetic parameters statistically comparable to V3 (p ≤ 0.05). Increasing the SCO2 dose further in V5 did not enhance AD efficiency; biogas and CH4 yields decreased slightly to 525 ± 21 mL/g VS and 340 ± 13 mL CH4/g VS, with kinetic parameters (kCH4 = 0.221 1/day, rCH4 = 74.8 mL CH4/day) similar to those in V4.

These findings are consistent with previous studies on SCO2 pretreatment of sludge. Kazimierowicz et al. [58] reported maximum biogas production of 630.2 ± 45.5 mL/g VS and CH4 content of 68.7 ± 1.5% at a SCO2:sludge volume ratio of 0.3, with no further improvement at higher doses. Similarly, aerobic granular sludge (AGS) studies by the authors [25] demonstrated peak biogas and methane yields at a SCO2:AGS ratio of 0.3 under mesophilic conditions (42 °C), while higher doses decreased pH below 6.5, limiting methanogenic activity. Thermophilic conditions (55 °C) also confirmed optimal results at a SCO2:AGS ratio of 0.3, producing 482 ± 21 mL/g VS of biogas, including 337 ± 14 mL CH4/g VS [59]. Hybrid processes combining alkalization and SCO2 disintegration similarly demonstrated maximum biogas yields at intermediate sludge fractions, confirming the repeatability of the optimal SCO2 dose across systems [61].

Table 4 shows the efficiency of using pretreatment techniques for Chlorella sp. microalgae biomass before anaerobic dogestion.

Table 4.

Efficiency of anaerobic digestion of microalgae biomass according to the pretreatment method used.

3.4. Continuous Fermentation Bioreactors—S4

Efficiency of Biogas and Methane Production

In continuous bioreactor studies, two experimental variants (V3 and V4), which had exhibited the highest performance in batch experiments (S3), were tested alongside a control variant (V0) in which no SCO2 pretreatment was applied to the C. vulgaris biomass. The results confirmed the significant and positive effect of low-temperature disintegration with SCO2 on the enhancement of biogas and methane production rates. However, it is important to note that, under continuous operation conditions (HRT ≈ 20 days, OLR ≈ 2.2 g VS/L·d), the overall anaerobic digestion efficiency was substantially lower than that observed in batch reactors (S2).

This can be attributed to differing operational conditions, which directly affect the mode of contact between microorganisms and the substrate. In batch systems, Chlorella vulgaris biomass was introduced in a single loading. This ensured full contact time between the anaerobic microbiota and the substrate, as well as maximal utilisation of hydrolysates, particularly following SCO2 pretreatment. The absence of flow favours the maintenance of high concentrations of hydrolytic and acetogenic enzymes in the environment and allows for complete mineralization of organic matter [66]. In continuous reactors, a portion of VFAs and other soluble compounds may be removed from the system before full conversion to CH4 [67]. The continuous-flow nature also promotes the loss of some methanogens, resulting in lower overall microbial activity and reduced final technological performance [68]. Similar observations have been reported in numerous studies [69,70,71].

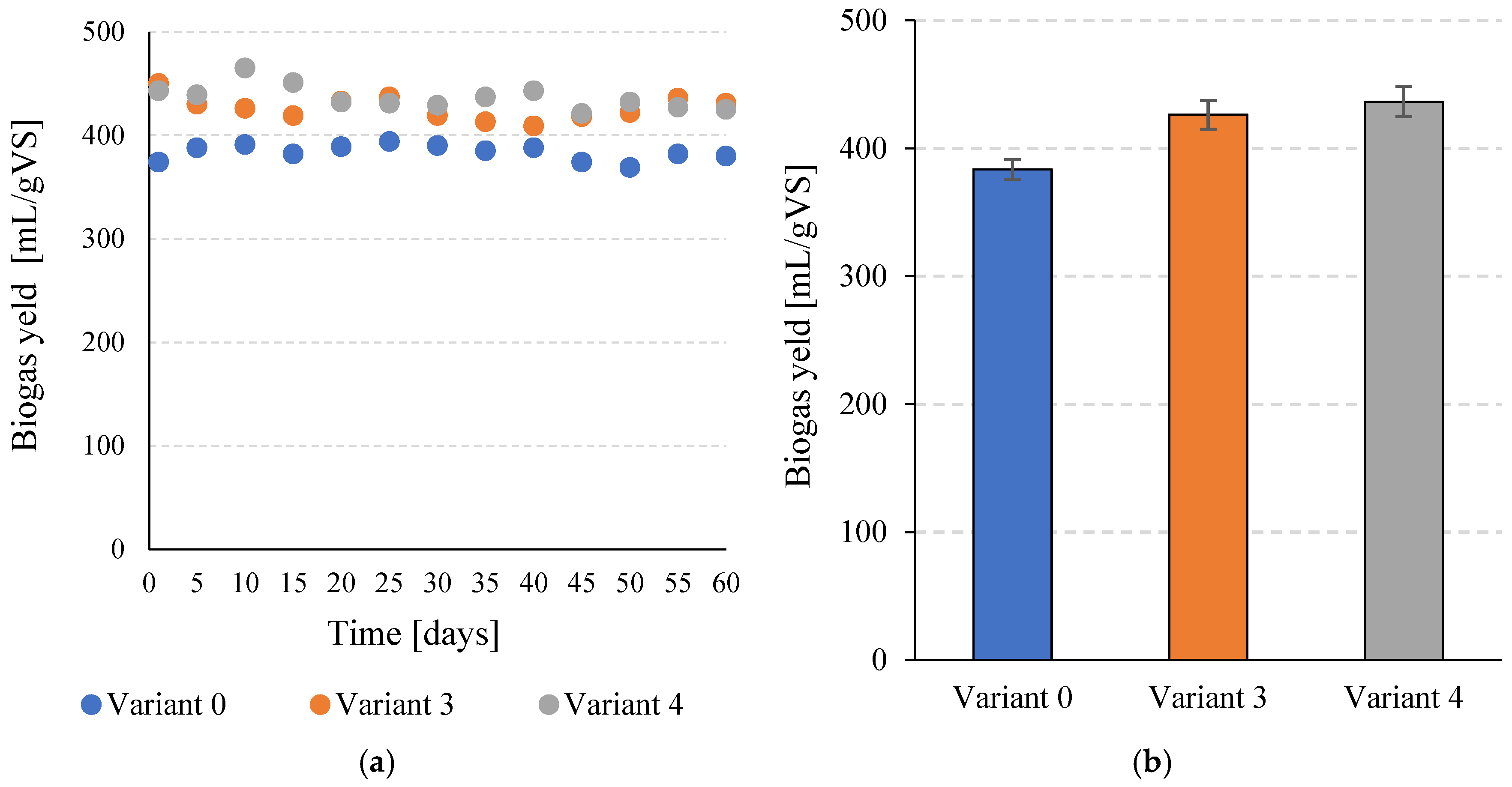

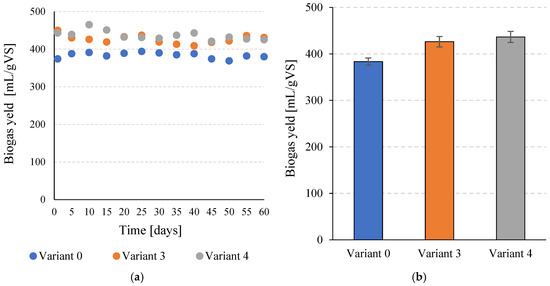

Total biogas production in the control variant (V0) was 383.5 ± 7.6 mL/g VS. Pretreatment of C. vulgaris biomass with SCO2 in V3 resulted in a statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05) increase to 426.4 ± 11.3 mL/g VS. The highest biogas yield was observed in V4, reaching 436.5 ± 11.9 mL/g VS (Figure 3a,b), which was significantly higher than the control (p ≤ 0.05). However, the difference between V3 and V4 was not statistically significant (p > 0.05), indicating that a plateau in biogas production was reached at higher SCO2 doses.

Figure 3.

Biogas production per unit during the entire operating time of the continuous bioreactors (a) and the mean values obtained for the tested variants (b).

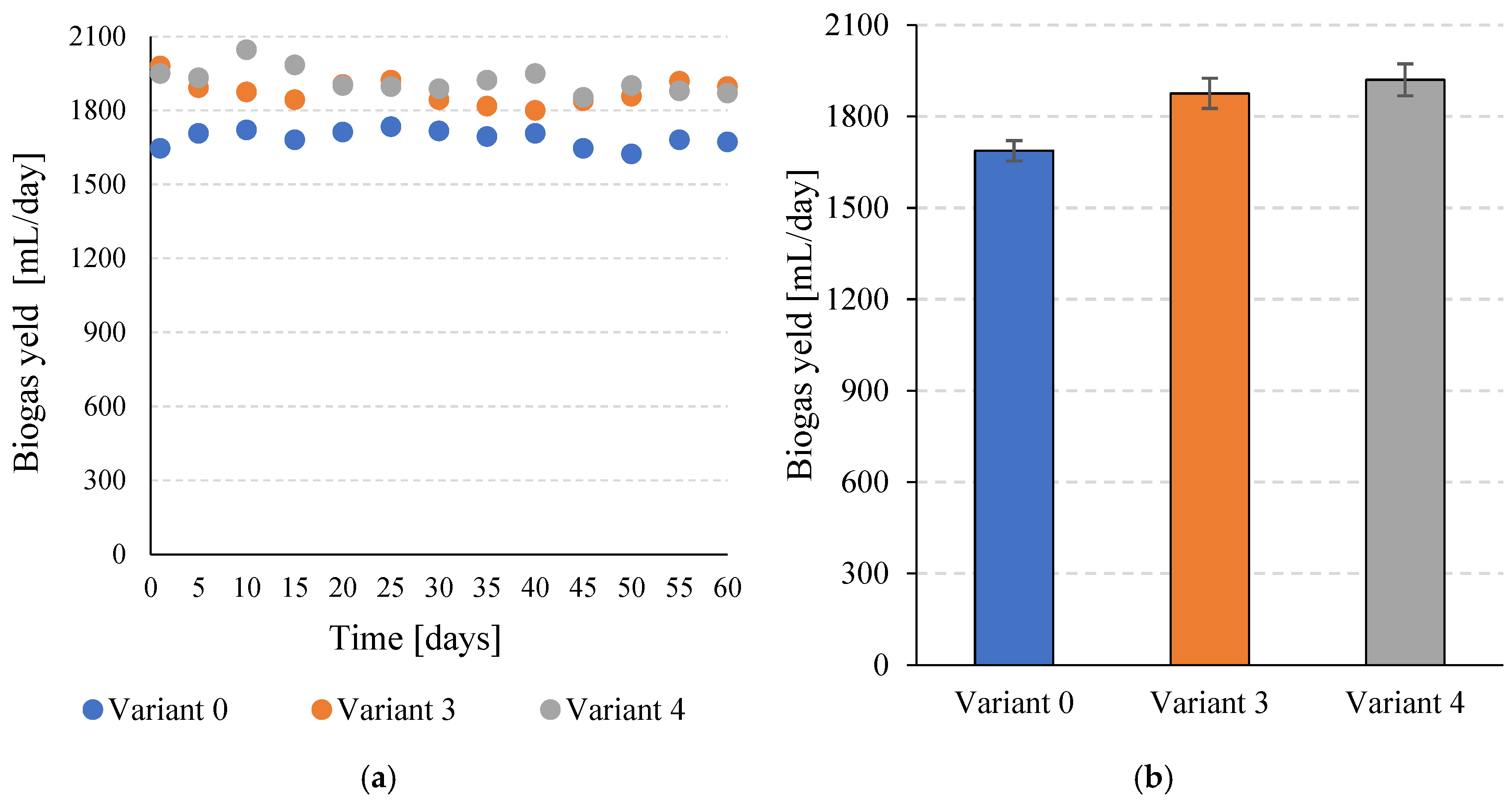

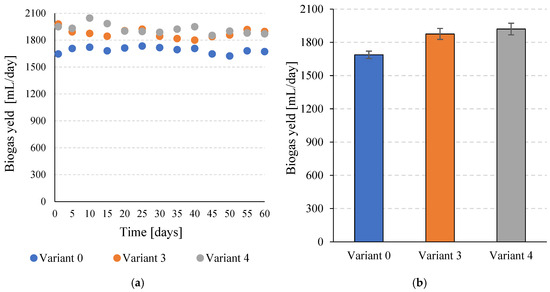

Similar relationships were observed for daily biogas production. The control variant (V0) reached a value of 1687.6 ± 33.3 mL/day, while the use of disintegration in V3 and V4 allowed the production of 1876.1 ± 49.5 mL/day and 1920.8 ± 52.4 mL/day, respectively (Figure 4a,b). In both cases, the differences compared to variant 0 were statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 4.

Daily efficiency of biogas production during the entire operation of the continuous bioreactors (a) and the average values obtained for the variants tested (b).

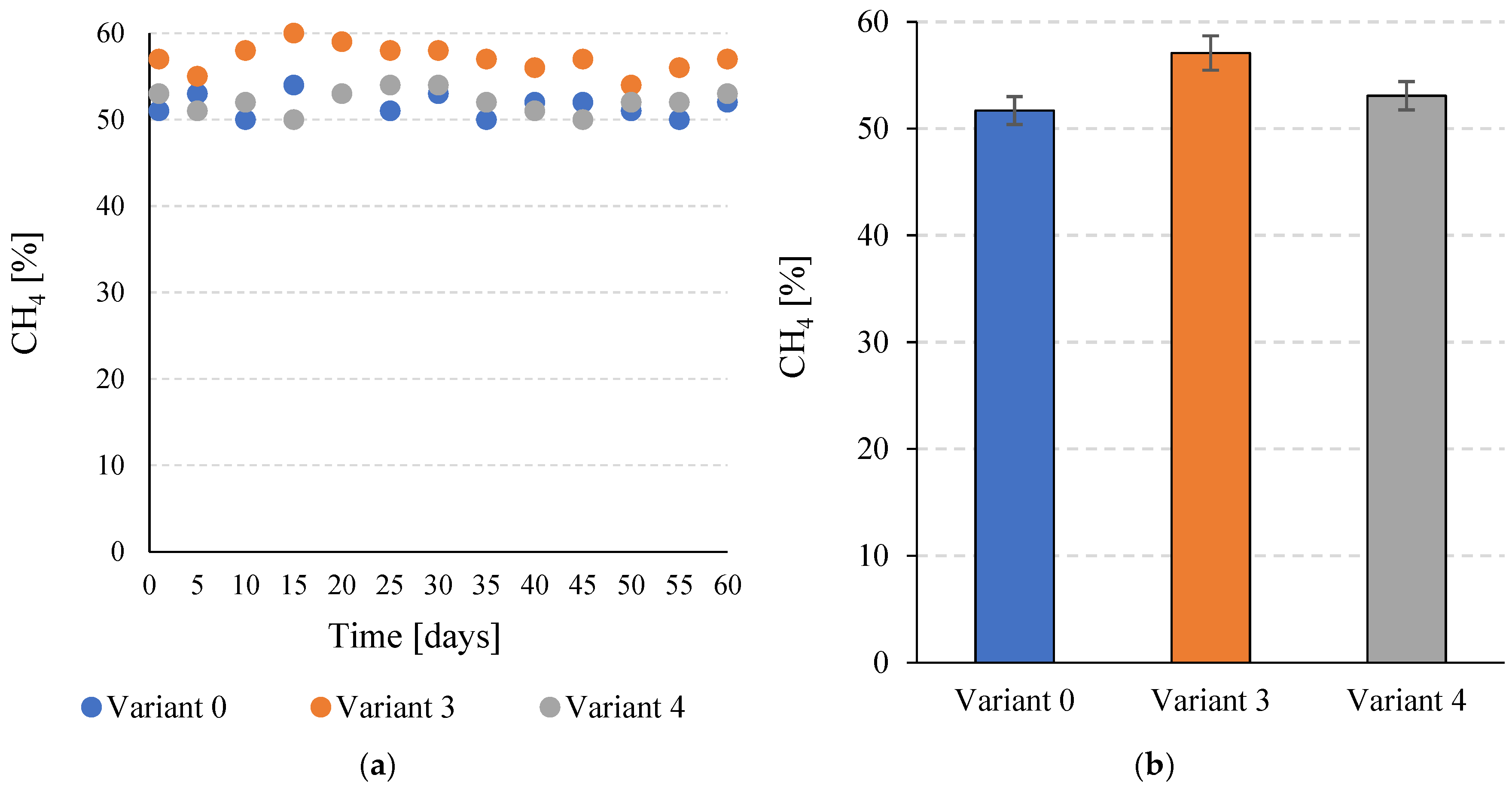

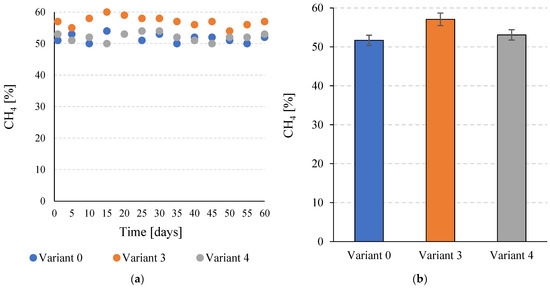

At the stage of this study, it was found that the percentage of CH4 in the biogas depended on the variant of pre-treatment of the C. vulgaris biomass used. For V0, this value was 51.7 ± 1.3%. V4 had a higher average value of 53.1 ± 1.3%. However, the observed difference was not statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05). In V3, on the other hand, the CH4 content in the biogas increased significantly to 57.1 ± 1.6% (p ≤ 0.05) (Figure 5a,b).

Figure 5.

Percentage of CH4 in the biogas during the entire operation of the continuous bioreactors (a) and the average values achieved for the tested variants (b).

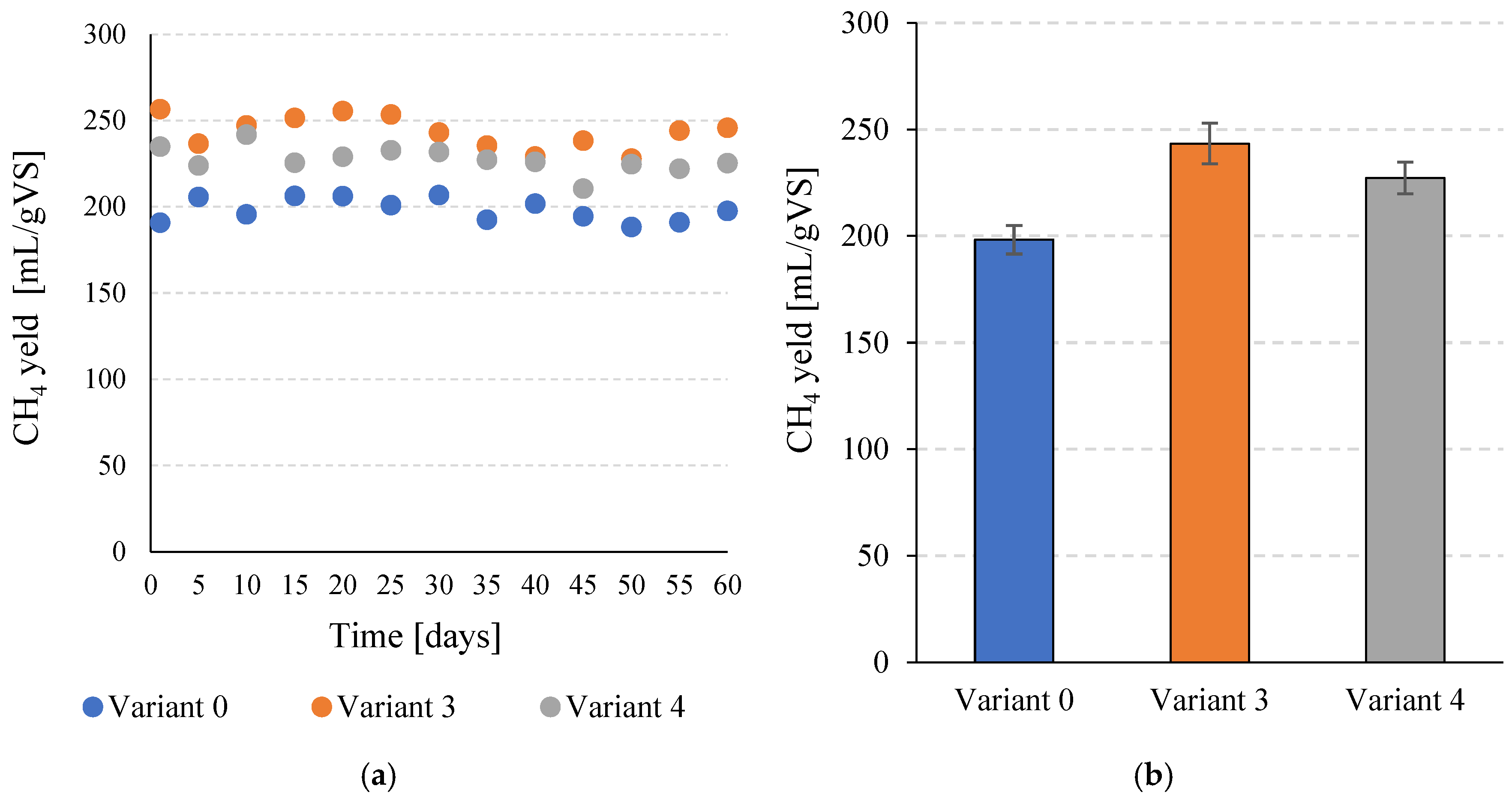

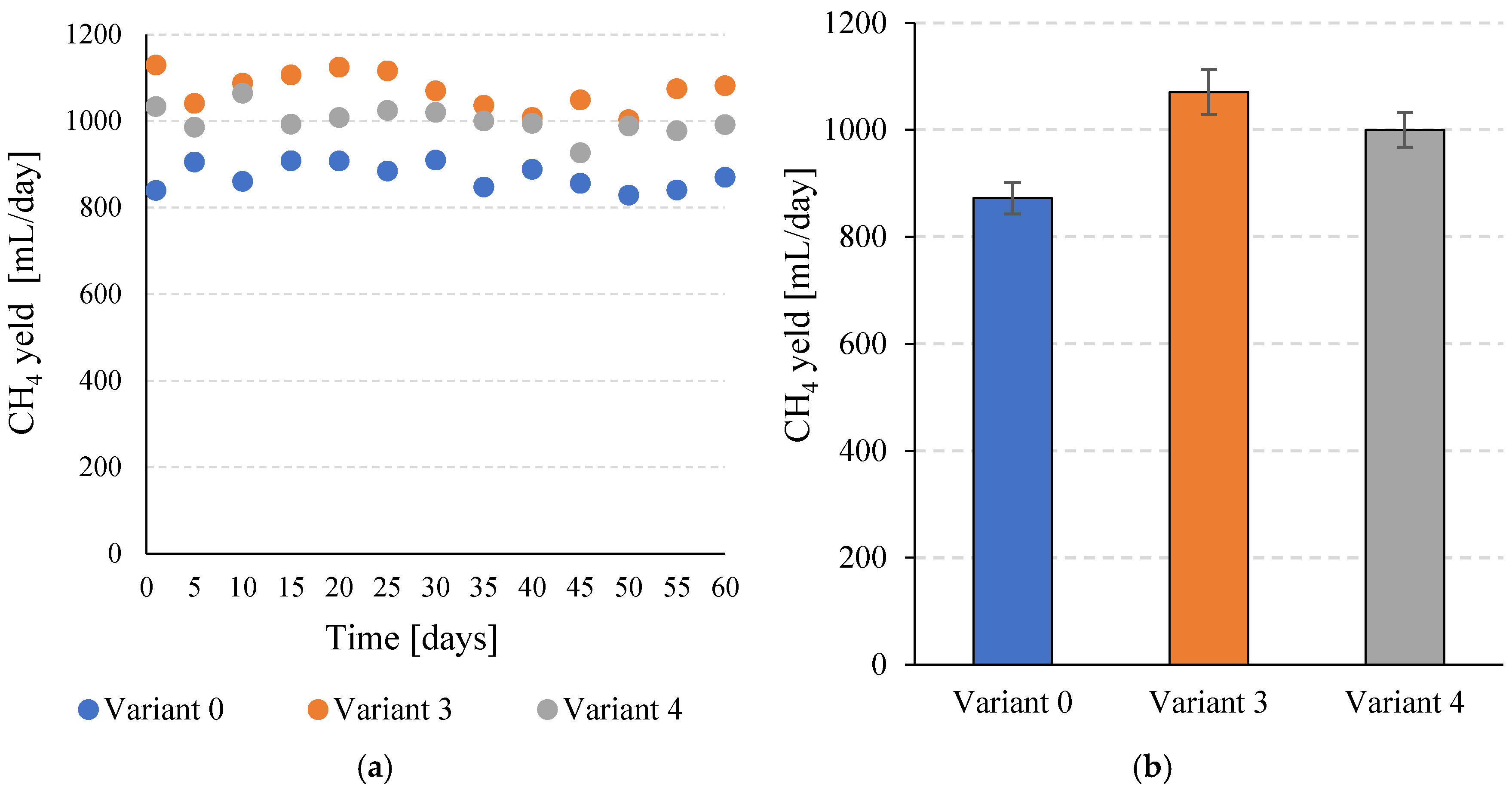

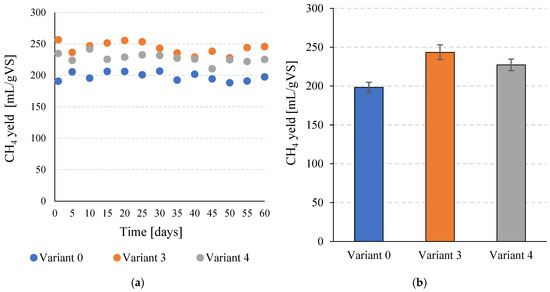

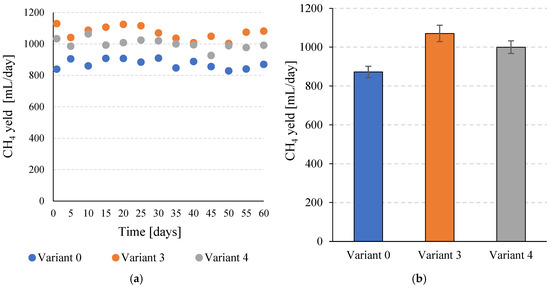

The increase in total biogas production and the simultaneous increase in CH4 content after the application of SCO2 pretreatment contributed to a significant increase in specific CH4 production. For V0, a value of 198.3 ± 6.7 mL CH4/gVS was obtained, while in V3 a value of 243.4 ± 9.5 mL CH4/gVS was achieved (Figure 6a,b). This corresponds to a significant (p ≤ 0.05) increase of over 22%. In V4, 227.3 ± 7.4 mL CH4/gVS was obtained, which also represents a significant (p ≤ 0.05) improvement compared to the V0 sample. Similar trends were observed in daily CH4 production. In the control variant, a value of 872.4 ± 29.5 mL CH4/day was achieved. In V3 and V4, 1070.8 ± 41.9 mL CH4/day and 1000.1 ± 32.5 mL CH4/day were achieved, respectively (Figure 7a,b). In both variants in which pretreatment with SCO2 was used, the differences compared to V0 were statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05). At the same time, the technological effects were significantly (p ≤ 0.05) higher in V3 than in V4.

Figure 6.

CH4 production per unit during the entire operating time of the continuous bioreactors (a) and the average values determined for the tested variants (b).

Figure 7.

Daily CH4 production efficiency during the entire operating time of the continuous bioreactors (a) and the mean values obtained for the tested variants (b).

Analysing the results revealed statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) between the variants in terms of anaerobic digestion efficiency, specific biogas production and methane production (Table 4). The lowest efficiency of 36.2 ± 1.6% was achieved in the control variant V0. The highest efficiency was 40.5 ± 1.3% in V3. This value was 11.9% higher than that of the control variant. A value of 38.1 ± 1.5% was achieved in V4 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Efficiency of anaerobic digestion and biogas and CH4 production per removed load VS.

Specific biogas production per unit of VS removed ranged from 224 ± 4.1 L/kg VS removed in the control variant (V0) to 243 ± 3.7 L/kg VS removed in V4. Variant V3 achieved 240 ± 3.9 L b/kg VS removed, also significantly higher than the control (p ≤ 0.05). The approximately 8% higher values observed in V3 and V4 indicate enhanced degradation of total organic matter, although this did not necessarily result in a proportional increase in methane production. The highest specific CH4 production was obtained in V3, reaching 128 ± 2.1 L CH4/kg VS removed, which corresponds to a 10.3% increase compared to V0 (116 ± 3.3 L CH4/kg VS removed). Variant V4 achieved 126 ± 2.0 L CH4/kg VS removed, significantly higher than the control (p ≤ 0.05) but slightly lower than V3. Thus, pretreatment of C. vulgaris in V3 proved most effective in terms of methane yield per unit of VS removed, while V4 maximised total biogas production.

The differential effects of the variants on the fermentation gas composition are consistent with previous reports indicating that optimisation of biomass pretreatment conditions can preferentially enhance either methanogenesis or total gas production depending on process parameters [25,26]. Most studies on SCO2-assisted pretreatment have been conducted in batch reactors, limiting the assessment of long-term effects on continuous reactor performance and anaerobic digestion efficiency. In previous work [26], long-term pretreatment of municipal sewage sludge (MSS) with SCO2 was evaluated with respect to reactor operational parameters, anaerobic microbial community structure, and biogas yield and quality. Positive effects were observed at organic loading rates (OLR) of 3.0–4.0 g VS/L·day, with the highest performance at 3.0 g VS/L·day, where daily biogas production reached 29 ± 1.3 L/day, the yield per VS unit was 0.49 ± 0.02 L/g VS, and the methane content was 70.1 ± 1.0%

3.5. Characterisation of Post-Fermentation Sludge

Analysis of the physicochemical properties of the post-fermentation sludge from the continuous bioreactors revealed significant differences between the technological variants tested. Detailed results for the tested experimental variants are listed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Characterisation of the post-fermentation sludge from continuous bioreactors depending on the technological variant tested.

The (TS) content of the digested C. vulgaris biomass did not differ significantly (p ≤ 0.05) among the analysed technological variants, ranging from 4.0 to 4.1% of the raw mass. However, the proportion of volatile solids (VS) relative to TS showed statistically significant differences. In the control variant (V0), the VS content was highest at 69.4 ± 1.3% TS, whereas in the pretreated variants V3 and V4, VS decreased significantly to 66.9 ± 1.9% TS and 66.5 ± 3.1% TS, respectively (Table 4). This suggests more effective decomposition of the organic fraction of C. vulgaris following SCO2 disintegration. Correspondingly, the mineral solids (MS) content showed an inverse trend, with the lowest value of 30.6 ± 1.3% TS in V0 and the highest of 34.2 ± 3.1% TS in V4.

Analysis of elemental composition revealed significant changes in total nitrogen (TN), total carbon (TC), and total organic carbon (TOC). TN decreased significantly across the experimental variants (p ≤ 0.05), from 47.4 ± 1.6 mg/g TS in V0 to 43.1 ± 3.1 mg/g TS in V3 and 39.1 ± 2.0 mg/g TS in V4. These reductions likely reflect more intensive protein degradation and partial conversion of nitrogen into gaseous forms under conditions of enhanced substrate bioavailability. TC also decreased significantly, reaching a minimum of 328 ± 41 mg/g TS in V4, confirming greater decomposition of the biomass organic matter. Although TOC decreased from 333 ± 22 mg/g TS in V0 to 315 ± 29 mg/g TS in the pretreated variants, these differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

The C/N ratio increased significantly (p ≤ 0.05) from 8.1 ± 0.1 (V0) to 8.6 ± 0.2 (V3), primarily due to a relatively greater reduction in TN than in TOC, corroborated by the measured protein content in the digestate. Protein content decreased from 29.7 ± 1.0% TS in V0 to 24.4 ± 1.3% TS in V3, confirming enhanced protein degradation through SCO2-assisted disintegration. Fat content remained stable across variants (2.6–3.0% TS), whereas carbohydrate content decreased significantly in the pretreated variants (V3: 1.3 ± 0.1% TS; V4: 1.5 ± 0.5% TS) compared to V0 (1.9 ± 0.2% TS), indicating improved biodegradation of sugars. The pH of post-fermentation sludge remained within the neutral range (7.01 ± 0.32 in V3 to 7.48 ± 0.19 in V4), indicating balanced hydrolysis, acidogenesis, and methanogenesis. Total phosphorus (TP) did not vary significantly among variants, ranging from 3.7 ± 0.2 mg/g TS (V0) to 4.3 ± 1.4 mg/g TS.

Overall, SCO2 pretreatment of C. vulgaris biomass (V3 and V4) significantly influenced the chemical composition of the digestate, leading to decreased organic matter, proteins, nitrogen, and carbohydrates, with concomitant increases in mineral content and C/N ratio. These changes confirm enhanced bioavailability of nutrients for fermentative microorganisms, which can positively impact the efficiency and stability of the anaerobic digestion process.

The properties of the resulting digestate are largely determined by the substrate type [72]. Concentrations of key fertiliser components (N:P:K) depend on the original biomass composition and vary with substrate type, with nitrogen being highest in animal-based substrates and phosphorus and potassium higher in plant-derived substrates [73]. The degree of digestion, organic matter removal, and final digestate composition are strongly influenced by technological parameters such as OLR, HRT, and fermentation temperature [74], as well as pretreatment strategies and hydrolysis-supporting methods [75]. High degrees of digestion are essential for reducing environmental impacts of digestate, including putrefaction and odour emissions [76].

The TAC value of 6.6 ± 0.4 g CaCO3/L was slightly higher in V3 compared to V0 and V4, where values of 5.9 ± 0.3 g CaCO3/L and 6.1 ± 0.3 g CaCO3/L were recorded, respectively (Table 5). This indicates the maintenance of buffer system stability across all variants. The FOS values showed a similar trend. The highest concentration of volatile fatty acids, 0.91 ± 0.07 g/L, was observed in V3, while the lowest, 0.78 ± 0.06 g/L, occurred in V0, with the observed differences being statistically significant (p < 0.05). The FOS/TAC ratio remained within a safe range of 0.13–0.14 for all variants, indicating a stable fermentation process and minimal risk of acidification (Table 5).

3.6. Anaerobic Bacterial Community

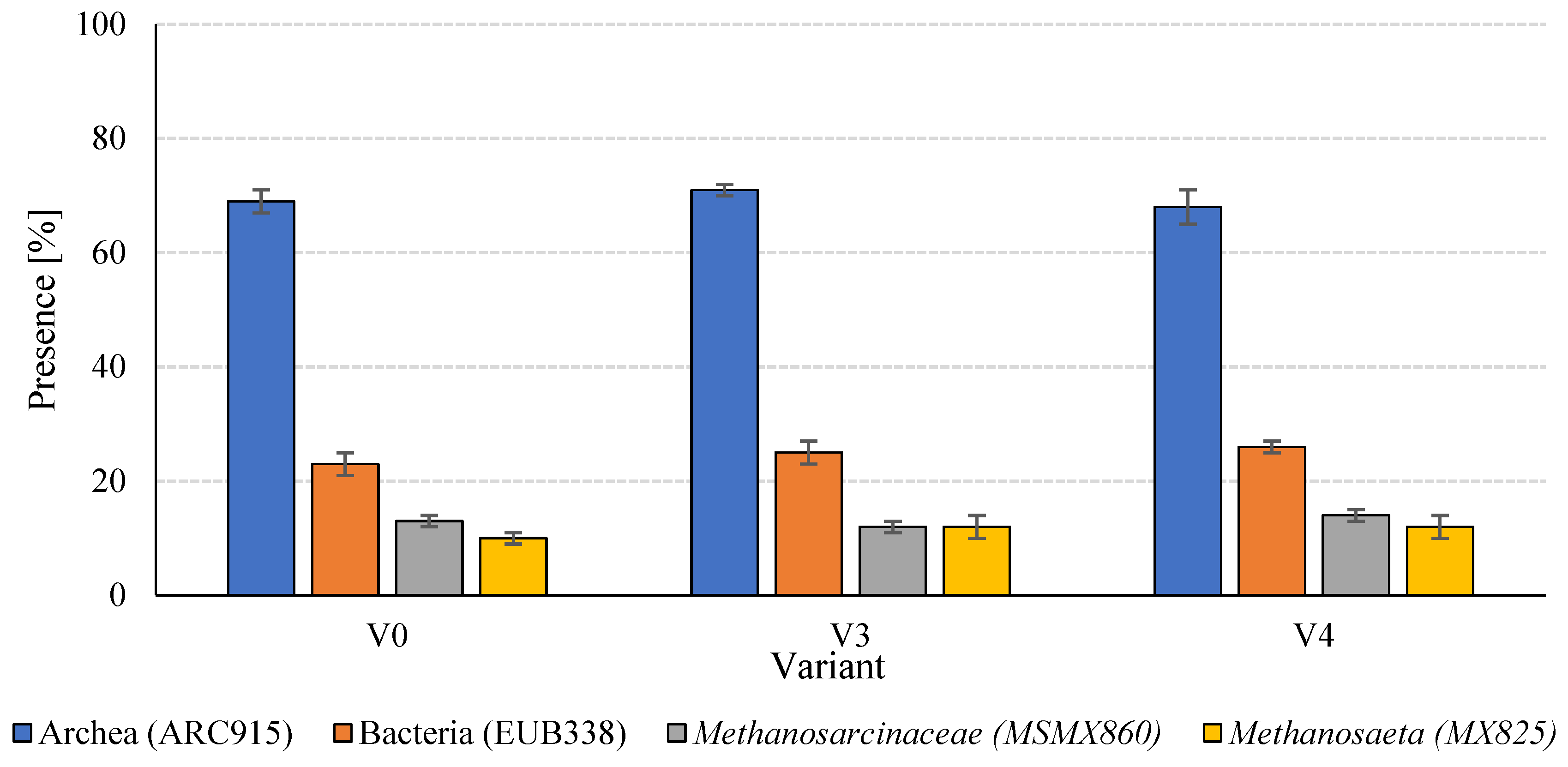

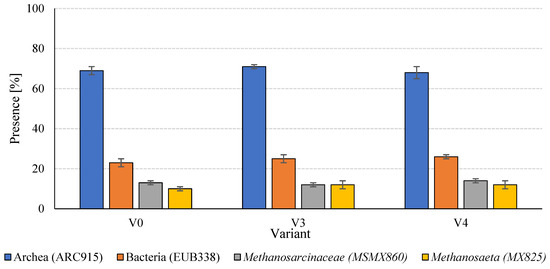

Analysis of the structure of the anaerobic microbial consortia in the digested sludge revealed relative stability at the level of basic domains, with minor differences in the taxonomic composition of selected methanogen groups (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Microbial taxonomy in anaerobic sludge.

At the domain level, Archaea were the dominant microorganisms in all experimental variants, representing 68 ± 3% (V4) to 71 ± 1% (V3) of the hybridisation signal obtained with the ARC915 probe (Table 5). The consistently high presence of Archaea indicates that functional equilibrium in methanogenesis was maintained across all treatments, irrespective of SCO2 pretreatment. In parallel, bacterial populations ranged from 23 ± 2% in V0 to 26 ± 1% in V4, with an increasing trend observed in the variants subjected to biomass disintegration. Although these shifts were moderate, they may reflect enhanced activity of fermentative bacteria responsible for hydrolysis and acidogenesis. The higher bacterial proportion in V4 could be attributed to the increased availability of soluble organic compounds and cell fragments generated during low-temperature disintegration, promoting accelerated fermentation.

Within methanogenic groups, members of the Methanosarcinaceae family (MSMX860) were consistently present at 12–14%, with the highest proportion in V4 (14 ± 1%). This suggests that these methanogens were more active in environments enriched with readily utilisable substrates, such as acetate and methanol, which are preferentially metabolised by Methanosarcinaceae. Similarly, Methanosaeta spp. (MX825), highly specialised acetoclastic methanogens, showed stable proportions of 12 ± 2% in V3 and V4, slightly lower in the control (10 ± 1%). The increased abundance of Methanosaeta in pretreated variants likely reflects more favourable conditions for acetate-based methanogenesis, arising from enhanced degradation of organic matter and more stable fermentation conditions. Overall, the microbial structure of the anaerobic consortia appeared resilient to the technological modifications introduced during substrate pretreatment. Nonetheless, the observed shifts in bacterial and methanogen proportions indicate adaptive responses of the microbial community to the altered profile of soluble organic compounds resulting from SCO2 pretreatment.

Previous studies [26] reported no significant effect of SCO2 pretreatment on the overall composition of anaerobic bacterial communities at OLRs of 2–3 gVS/L·day, with Archaea consistently comprising more than 24% of the total population. At higher OLRs (4–5 gVS/L·day), a decrease in methanogenic archaea was observed. Similar conclusions were drawn by Gagliano et al. [77], demonstrating that substrate pretreatment prior to anaerobic digestion does not substantially alter the structure of the microbial community. FISH analysis with Archaea-specific probes revealed long, filamentous Methanosaeta spp. present throughout all stages of digestion, confirming the dominance of acetotrophic methanogenesis under mesophilic conditions.

The authors consider the pretreatment of C. vulgaris biomass with SCO2 an innovative, low-energy approach for enhancing microalgal methane fermentation. This method operates through the synergistic interaction of physical and physicochemical factors, disrupting cellular structural integrity and increasing the bioavailability of organic compounds for methanogenic microorganisms [28]. Sublimation of dry ice at −78.5 °C induces a rapid temperature drop in the biomass, causing freezing of water within and between cells. The resulting ice crystals generate mechanical stresses, producing microcracks in cell walls and cytoplasmic membranes. Consequently, the cell structure disintegrates, material porosity increases, and previously inaccessible organic fractions become available to the fermentative microbiota [78].

Simultaneously, sublimating CO2 saturates the gaseous and liquid phases, forming carbonic acid (H2CO3) and lowering biomass pH. Mild acidification promotes partial hydrolysis of polysaccharides and proteins, while CO2 also acts as a solvent, facilitating protein denaturation and lipid extraction [27]. The solid-to-gas transition of CO2 induces local pressure fluctuations, triggering cellular microexplosions that further enhance mechanical disintegration [79]. As a result, the proportion of soluble fractions in total organic matter increases, releasing a greater amount of readily biodegradable compounds. These processes accelerate hydrolysis—the rate-limiting step in methanogenesis—and improve overall CH4 production efficiency [24]. Literature reports indicate that SCO2 pretreatment can increase biogas yield by 15–40% relative to untreated biomass, while shortening the adaptation phase and boosting initial methane production rates [24].

From an environmental engineering perspective, the SCO2 method is particularly advantageous as it does not require aggressive chemical reagents, elevated pressures or temperatures, or complex technological systems. Moreover, it generates no waste or pollution [80]. Importantly, this technology aligns with the principles of a circular economy, since CO2 used in the process can be recovered from biogas plants via upgrading and enrichment technologies increasingly adopted in industrial practice [23]. The integration of CO2 recovery and its reuse for biomass pretreatment establishes a coherent, sustainable bioenergy production system that reduces greenhouse gas emissions and enhances the efficiency of the entire technological chain [23].

3.7. Energy Balance

The effectiveness of SCO2 as a low-temperature disintegration agent for C. vulgaris biomass was evaluated through an estimated energy balance, accounting for both the energy input associated with SCO2 production and the energy yield in the form of biomethane generated during anaerobic digestion. Analyses were conducted for both batch reactors (Table 7) and continuous digesters (Table 8), allowing assessment of how operating variables affect the overall energy efficiency of the process.

Table 7.

Energy efficiency estimated based on tests in batch bioreactors.

Table 8.

Energy efficiency estimated based on tests in continuous bioreactors.

In batch reactors (S3), increasing the SCO2-to-biomass ratio from 0.1 to 0.3 resulted in a systematic improvement in energy efficiency. In the control variant (V0), without pretreatment, the CH4 yield was only 12.2 L/kg FM, corresponding to a total energy yield of 111.6 Wh. Without biomass comminution, the net energy (difference between output energy and input energy for pretreatment) was effectively zero. Introducing SCO2 at a ratio of 0.1 (V1) significantly increased CH4 production to 13.9 L/kg FM, with total energy rising to 127.8 Wh. However, considering the energy input of 316 Wh, the net energy gain was only 15.5 Wh.

Further increases in SCO2 dose in variants V2 and V3 led to additional improvements, with biomethane production reaching 14.1 L/kg FM (V2) and 16.3 L/kg FM (V3), and total energy yields increasing to 129.4 Wh and 149.2 Wh, respectively. Notably, V3 achieved the highest net energy gain among all variants, at 35.7 Wh. Differences between V0–V3 were statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05) in both biomethane production and energy efficiency. Increasing the SCO2-to-biomass ratio above 0.3 (V4: 0.4, V5: 0.5) did not yield further energy benefits. Although CH4 yields remained relatively high (15.8 L/kg FM in V4 and 15.0 L/kg FM in V5), net energy values decreased to 31.0 Wh and 22.7 Wh, respectively, due to disproportionate energy inputs without corresponding gains in methane production. Total energy yields in these variants remained high (145.2 Wh in V4 and 137.5 Wh in V5), indicating that the process reached a saturation point at a SCO2-to-biomass ratio of 0.3.

These results are consistent with previous studies [15], where batch pretreatment of granular activated sludge (AGS) with a SCO2 ratio of 0.3 produced the highest total energy gain (3053 ± 100 kWh/Mg VS), compared to 1950 ± 110 kWh/Mg VS for the control. Similar trends were observed in studies with excess sludge from dairy wastewater treatment plants [45], where positive net energy gains were achieved at SCO2-to-sludge ratios of 0.1–0.3, ranging from 2700 ± 110 kWh/Mg VS (0.1) to 2800 ± 100 kWh/Mg VS (0.3). These findings underscore the importance of optimising SCO2 dose to maximise energy efficiency while maintaining the economic and environmental viability of the pretreatment process.

Analogous trends were observed under continuous fermentation, which, despite greater process complexity, better reflects real operating conditions. Variants V3 and V4, identified as optimal in batch experiments, were evaluated in continuous reactors. In both cases, absolute biomethane yields were lower than in batch fermentation, reflecting the operational constraints of continuous systems. Variant V3 achieved a significantly higher CH4 yield of 10.8 L/kg FM compared to 9.9 L/kg FM in V4 (p ≤ 0.05, Table 7). Correspondingly, the net energy gain was also higher for V3 (17.4 Wh) than V4 (8.3 Wh), with these differences being statistically significant (p < 0.05). These results confirm that, even in continuous systems, increasing the SCO2 dose above a ratio of 0.3 leads to decreased energy efficiency, consistent with the saturation effect observed in batch experiments. The evaluation of energy efficiency is therefore critical for assessing both the economic feasibility and sustainability of the process, particularly at an industrial scale [81].

Previous studies on long-term conditioning of sewage sludge with SCO2 prior to anaerobic digestion in continuous reactors [26] corroborate these findings. The highest gross energy gain was observed at an OLR of 3.0 g VS/L·day, reaching 187.07 ± 1.5 Wh/day, compared to 148.55 ± 1.3 Wh/day in reactors without pretreatment. The application of SCO2 pretreatment for intensifying methane fermentation is thus clearly justified. It enhances process efficiency across multiple dimensions—technological, economic, and ecological—especially when integrated with systems employing closed CO2 recycling, which further supports sustainability by reducing greenhouse gas emissions [23].

4. Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that pretreatment of Chlorella vulgaris biomass with solidified carbon dioxide (SCO2) significantly enhances the bioavailability of organic compounds, as evidenced by increased concentrations of dissolved COD and TOC and higher solubilisation rates. The most effective results were achieved at a SCO2-to-biomass volume ratio of 1:3.

The application of SCO2 markedly improved the efficiency of anaerobic digestion in both batch and continuous systems. Methane yields were significantly increased, and the kinetic parameters of the process indicated accelerated methanogenesis, reflecting enhanced substrate accessibility. Analysis of the digestate confirmed more intensive biodegradation of organic matter, including proteins and carbohydrates, highlighting the improved microbial conversion of the pretreated biomass.

Microbial community analysis revealed that the structural composition of the fermentation microflora remained largely stable, preserving functional balance and demonstrating the microbiological resilience of the system to low-temperature disintegration.

The energy balance indicated a positive net gain, confirming the energy efficiency and economic viability of the process. Overall, SCO2 pretreatment of microalgae biomass represents an innovative, environmentally friendly, and energy-efficient alternative to conventional disintegration methods, with strong potential for industrial-scale implementation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K. and M.D.; methodology, J.K. and M.D.; software, J.K.; validation, J.K. and M.D.; formal analysis, J.K. and M.D.; investigation, J.K., M.D. and M.Z.; resources, J.K., M.D. and M.Z.; data curation, M.D.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K. and M.D.; writing—review and editing, J.K., M.D. and M.Z.; visualisation, J.K., M.D. and M.Z.; supervision, M.Z.; funding acquisition, M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by works WZ/WB-IIŚ/3/2025 of the Bialystok University of Technology and No. 29.610.023-110 of the University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, X.; Ma, S.; Kong, F. Microalgae Biotechnology: Methods and Applications. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrena, R.; Blánquez, P.; Font, X.; Sánchez, A. Biogas Production from Anaerobic Digestion of Microalgae. In Microalgae as Promising Source of Commercial Bioproducts; Developments in Applied Phycology; Santos Ballardo, D.U., Rossi, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; Volume 14, pp. 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.A.; Ferreira, J.; de Castro, J.S.; Braga, M.Q.; Calijuri, M.L. Microalgae from Food Agro-Industrial Effluent as a Renewable Resource for Agriculture: A Life Cycle Approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 186, 106575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Estrada, L.; Longoria, A.; Arenas, E.; Moreira, J.; Okoye, P.U.; Bustos-Terrones, Y.; Sebastian, P.J. A Review on Current Trends in Biogas Production from Microalgae Biomass and Microalgae Waste by Anaerobic Digestion and Co-Digestion. BioEnergy Res. 2021, 15, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parakh, S.K.; Tian, Z.; Wong, J.Z.E.; Tong, Y.W. From Microalgae to Bioenergy: Recent Advances in Biochemical Conversion Processes. Fermentation 2023, 9, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, S.; Grande, P.M.; Blank, L.M.; Klose, H. Insights into Cell Wall Disintegration of Chlorella vulgaris. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussgnug, J.H.; Klassen, V.; Schlüter, A.; Kruse, O. Microalgae as Substrates for Fermentative Biogas Production in a Combined Biorefinery Concept. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 150, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spain, O.; Funk, C. Detailed Characterization of the Cell Wall Structure and Composition of Nordic Green Microalgae. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 9711–9721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veerabadhran, M.; Gnanasekaran, D.; Wei, J.; Yang, F. Anaerobic Digestion of Microalgal Biomass for Bioenergy Production, Removal of Nutrients and Microcystin: Current Status. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 131, 1639–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleszek, M.; Krzemińska, I. Biogas Production from High-Protein and Rigid Cell Wall Microalgal Biomasses: Ultrasonication and FT-IR Evaluation of Pretreatment Effects. Fuel 2021, 296, 120676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, R.; Silkina, A.; Melville, L.; Suhartini, S.; Sulu, M. Optimisation of Ultrasound Pretreatment of Microalgal Biomass for Effective Biogas Production through Anaerobic Digestion Process. Energies 2023, 16, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Mofijur, M.; Uddin, M.N.; Kabir, Z.; Badruddin, I.A.; Khan, T.M.Y. Insights into Anaerobic Digestion of Microalgal Biomass for Enhanced Energy Recovery. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1355686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Yin, Q.; He, K.; De Vrieze, J.; Wu, G. Feeding Regime Selectively Enriching Acetoclastic Methanogens to Enhance Energy Production in Anaerobic Digestion Systems. Biochem. Eng. J. 2025, 220, 109764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, Q.; Feng, Y.; Xuan, J. Composition of Lignocellulose Hydrolysate in Different Biorefinery Strategies: Nutrients and Inhibitors. Molecules 2024, 29, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beschkov, V.N.; Angelov, I.K. Volatile Fatty Acid Production vs. Methane and Hydrogen in Anaerobic Digestion. Fermentation 2025, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongco, J.V.; Jannat, M.A.H.; Kim, S.; Park, S.H.; Hwang, S. Process Performance and Biogas Output: Impact of Fluctuating Acetate Concentrations on Methanogenesis in Horizontal Anaerobic Reactors. Energies 2025, 18, 3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, W.A.; Izza, N.; Hj Hassan, U.H.; Alsaigh, A.A.; Wibisono, Y. Exploring the Mechanisms of Supplemented CO2 in Enhancing Methane Production in Anaerobic Digestion Process, a Review. Bioengineered 2025, 16, 2531667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadol, H.J.; Elsherbini, J.; Kocar, B.D. Methanogen Productivity and Microbial Community Composition Varies with Iron Oxide Mineralogy. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 705501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Yin, Q.; Wang, Z. Anaerobic Digestion Under Environmentally Stressed Conditions. In Anaerobic Digestion; Green Energy Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 83–96, Part F3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasundaram, G.; Banu, R.; Varjani, S.; Kazmi, A.A.; Tyagi, V.K. Recalcitrant Compounds Formation, Their Toxicity, and Mitigation: Key Issues in Biomass Pretreatment and Anaerobic Digestion. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Q.; Dar, R.A.; Baganz, F.; Smoliński, A.; Rasmey, A.-H.M.; Liu, R.; Zhang, L. Effects of Lignocellulosic Biomass-Derived Hydrolysate Inhibitors on Cell Growth and Lipid Production During Microbial Fermentation of Oleaginous Microorganisms—A Review. Fermentation 2025, 11, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, K.; Suresh, K. Metabolic and Biochemical Pathways for Anaerobic Digestion. In Anaerobes and Waste Conversion Technologies; Microorganisms for Sustainability; Springer: Singapore, 2024; Volume 44, pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierowicz, J.; Dębowski, M.; Zieliński, M. Innovative Method for Biomethane Production Based on a Closed Cycle of Biogas Upgrading and Organic Substrate Pretreatment—Technical, Economic, and Technological Fundamentals. Energies 2025, 18, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierowicz, J.; Dębowski, M. Characteristics of Solidified Carbon Dioxide and Perspectives for Its Sustainable Application in Sewage Sludge Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazimierowicz, J.; Dębowski, M.; Zieliński, M. Technological, Ecological, and Energy-Economic Aspects of Using Solidified Carbon Dioxide for Aerobic Granular Sludge Pre-Treatment Prior to Anaerobic Digestion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierowicz, J.; Dębowski, M.; Zieliński, M. Long-Term Pre-Treatment of Municipal Sewage Sludge with Solidified Carbon Dioxide (SCO2)—Effect on Anaerobic Digestion Efficiency. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machnicka, A.; Grübel, K.; Wacławek, S.; Sikora, K. Waste-Activated Sludge Disruption by Dry Ice: Bench Scale Study and Evaluation of Heat Phase Transformations. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 26488–26499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawieja, I.E. The Course of the Methane Fermentation Process of Dry Ice Modified Excess Sludge. Arch. Environ. Prot. 2019, 45, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, M.; Rusanowska, P.; Zieliński, M.; Dudek, M.; Kazimierowicz, J.; Quattrocelli, P.; Dębowski, M. Liquid Fraction of Digestate Pretreated with Membrane Filtration for Cultivation of Chlorella vulgaris. Waste Manag. 2022, 146, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębowski, M.; Zieliński, M.; Kisielewska, M.; Kazimierowicz, J.; Dudek, M.; Świca, I.; Rudnicka, A. The Cultivation of Lipid-Rich Microalgae Biomass as Anaerobic Digestate Valorization Technology—A Pilot-Scale Study. Processes 2020, 8, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębowski, M.; Kazimierowicz, J.; Nowicka, A.; Dudek, M.; Zieliński, M. The Use of Hydrodynamic Cavitation to Improve the Anaerobic Digestion of Waste from Dairy Cattle Farming—From Laboratory Tests to Large-Scale Agricultural Biogas Plants. Energies 2024, 17, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeshwari, K.V.; Balakrishnan, M.; Kansal, A.; Lata, K.; Kishore, V.V.N. State-of-the-Art of Anaerobic Digestion Technology for Industrial Wastewater Treatment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2000, 4, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, D.A.; Amann, R.I. Development and Application of Nucleic Acid Probes. In Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematic; Stackbrandt, E., Goodfellow, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 205–248. [Google Scholar]

- Raskin, L.; Stromley, J.M.; Rittmann, B.E.; Stahl, D.A. Group-Specific 16S RRNA Hybridization Probes to Describe Natural Communities of Methanogens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994, 60, 1232–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ImageJ. Available online: https://imagej.net/software/imagej/ (accessed on 17 December 2022).

- Cold Jet. P3000—Fully Automatic Dry Ice Pelletizer. Available online: https://www.coldjet.com/our-equipment/dry-ice-production-equipment/p3000/ (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Buswell, A.M.; Mueller, H.F. Mechanism of Methane Fermentation. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2002, 44, 550–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symons, G.E.; Buswell, A.M. The Methane Fermentation of Carbohydrates1,2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 55, 2028–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidaki, I.; Sanders, W. Assessment of the Anaerobic Biodegradability of Macropollutants. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2004, 3, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touliabah, H.E.S.; El-Sheekh, M.M.; Ismail, M.M.; El-Kassas, H. A Review of Microalgae- and Cyanobacteria-Based Biodegradation of Organic Pollutants. Molecules 2022, 27, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendez, L.; Mahdy, A.; Demuez, M.; Ballesteros, M.; González-Fernández, C. Effect of High Pressure Thermal Pretreatment on Chlorella vulgaris Biomass: Organic Matter Solubilisation and Biochemical Methane Potential. Fuel 2014, 117 Pt A, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, M. Biorefinery Products from Algal Biomass by Advanced Biotechnological and Hydrothermal Liquefaction Approaches. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markou, G.; Ilkiv, B.; Brulé, M.; Antonopoulos, D.; Chakalis, L.; Arapoglou, D.; Chatzipavlidis, I. Methane Production through Anaerobic Digestion of Residual Microalgal Biomass after the Extraction of Valuable Compounds. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2022, 12, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Kim, J.; Rhee, C.; Shin, J.; Shin, S.G.; Lee, C. Effects of Different PH Control Strategies on Microalgae Cultivation and Nutrient Removal from Anaerobic Digestion Effluent. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, P.; Yang, X.; Lin, P.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, M.; Ren, L. Process Performance and Microbial Communities in Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Sewage Sludge and Food Waste with a Lower Range of Carbon/Nitrogen Ratio. Bioenergy Res. 2022, 15, 1664–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierowicz, J.; Dębowski, M.; Zieliński, M. Taxonomic Structure Evolution, Chemical Composition and Anaerobic Digestibility of Microalgae-Bacterial Granular Sludge (M-BGS) Grown during Treatment of Digestate. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, D.R.; Rohe, L.; Krause, S.; Guliyev, J.; Loewen, A.; Tebbe, C.C. Methanogenesis in Biogas Reactors under Inhibitory Ammonia Concentration Requires Community-Wide Tolerance. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 6717–6730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegari, A.; Bolognesi, S.; Cecconet, D.; Capodaglio, A.G. Production Technologies, Current Role, and Future Prospects of Biofuels Feedstocks: A State-of-the-Art Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 50, 384–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Caldwell, G.S.; Blythe, P.T.; Zealand, A.M.; Li, S.; Edwards, S.; Xing, J.; Goodman, P.; Whitworth, P.; Sallis, P.J. Co-Digestion of Microalgae with Potato Processing Waste and Glycerol: Effect of Glycerol Addition on Methane Production and the Microbial Community. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 37391–37408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lee, E.; Zhang, Q.; Ergas, S.J. Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Swine Manure and Microalgae Chlorella Sp.: Experimental Studies and Energy Analysis. Bioenergy Res. 2016, 9, 1204–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdy, A.; Mendez, L.; Tomás-Pejó, E.; del Mar Morales, M.; Ballesteros, M.; González-Fernández, C. Influence of Enzymatic Hydrolysis on the Biochemical Methane Potential of Chlorella vulgaris and Scenedesmus sp. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2016, 91, 1299–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdalena, J.A.; Ballesteros, M.; González-Fernandez, C. Efficient Anaerobic Digestion of Microalgae Biomass: Proteins as a Key Macromolecule. Molecules 2018, 23, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.Y.; Kweon, J.; Chantrasakdakul, P.; Lee, K.; Cha, H.Y. Anaerobic Digestion of Microalgal Biomass with Ultrasonic Disintegration. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2013, 85, 598–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, F.; Carretero, J.; Ferrer, I. Comparing Pretreatment Methods for Improving Microalgae Anaerobic Digestion: Thermal, Hydrothermal, Microwave and Ultrasound. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 279, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elalami, D.; Oukarroum, A.; Barakat, A. Anaerobic Digestion and Agronomic Applications of Microalgae for Its Sustainable Valorization. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 26444–26462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdy, A.; Ballesteros, M.; González-Fernández, C. Enzymatic Pretreatment of Chlorella vulgaris for Biogas Production: Influence of Urban Wastewater as a Sole Nutrient Source on Macromolecular Profile and Biocatalyst Efficiency. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 199, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montusiewicz, A.; Lebiocka, M.; Rozej, A.; Zacharska, E.; Pawłowski, L. Freezing/Thawing Effects on Anaerobic Digestion of Mixed Sewage Sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 3466–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazimierowicz, J.; Bartkowska, I.; Walery, M. Effect of Low-Temperature Conditioning of Excess Dairy Sewage Sludge with the Use of Solidified Carbon Dioxide on the Efficiency of Methane Fermentation. Energies 2020, 14, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierowicz, J.; Dębowski, M.; Zieliński, M.; Bartkowska, I.; Wasilewski, A.; Łapiński, D.; Ofman, P. The Use of Solidified Carbon Dioxide in the Aerobic Granular Sludge Pre-Treatment before Thermophilic Anaerobic Digestion. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Sahu, S.; Arya, S.K. Pretreatment and Fractionation of Algae Biomass for Value-Added Extraction. In Value Added Products from Bioalgae Based Biorefineries: Opportunities and Challenges; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grübel, K.; Machnicka, A. The Use of Hybrid Disintegration of Activated Sludge to Improve Anaerobic Stabilization Process. Ecol. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2020, 21, 119104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarcelli, P.G.; Serejo, M.L.; Paulo, P.L.; Boncz, M.Á. Evaluation of Biomethanization during Co-Digestion of Thermally Pretreated Microalgae and Waste Activated Sludge, and Estimation of Its Kinetic Parameters. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 706, 135745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdy, A.; Mendez, L.; Ballesteros, M.; González-Fernández, C. Enhanced Methane Production of Chlorella vulgaris and Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii by Hydrolytic Enzymes Addition. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 85, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova, O.; Passos, F.; Chamy, R. Enzymatic Pretreatment of Microalgae: Cell Wall Disruption, Biomass Solubilisation and Methane Yield Increase. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2019, 189, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, L.; Mahdy, A.; Timmers, R.A.; Ballesteros, M.; González-Fernández, C. Enhancing Methane Production of Chlorella vulgaris via Thermochemical Pretreatments. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 149, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, T.; Neubauer, P.; Junne, S. Role of Microbial Hydrolysis in Anaerobic Digestion. Energies 2020, 13, 5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giduthuri, A.T.; Ahring, B.K. Current Status and Prospects of Valorizing Organic Waste via Arrested Anaerobic Digestion: Production and Separation of Volatile Fatty Acids. Fermentation 2022, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]