Abstract

Renewable natural gas is an innovative alternative fuel source that has the potential to integrate seamlessly into the current energy and fuel sector. In addition, growing concerns related to energy security and environmental impact are incentivizing the development of RNG technologies. In conjunction with this document, current technologies related to biogas conditioning and biogas upgrading were covered in a separate analysis deemed Part I. With the current technologies, however, issues such as compositional quality, combustion efficiency, and high operational costs still need to be addressed before RNG can reach its true capability in use. Recent innovations have focused on optimizing techniques and introducing new methods to maximize methane yield and purity while minimizing costs and energy consumption. This document, Part II, provides an overview of emerging technologies related to further biogas upgrading, such as cryogenics, methane enrichment, and hybrid treatments, aimed at increasing cleaned biogas purity. Processes in development are also discussed, including industrial lung, supersonic separation, chemical hydrogenation, hydrate formation, and various biological treatments. The benefits of these advancements are increased purity for the ability to pipeline renewable natural gas in existing infrastructure, help industries reach sustainability goals, and contribute to a more resilient energy system. Together, Parts I and II offer a comprehensive understanding of both current and future technological developments.

1. Introduction

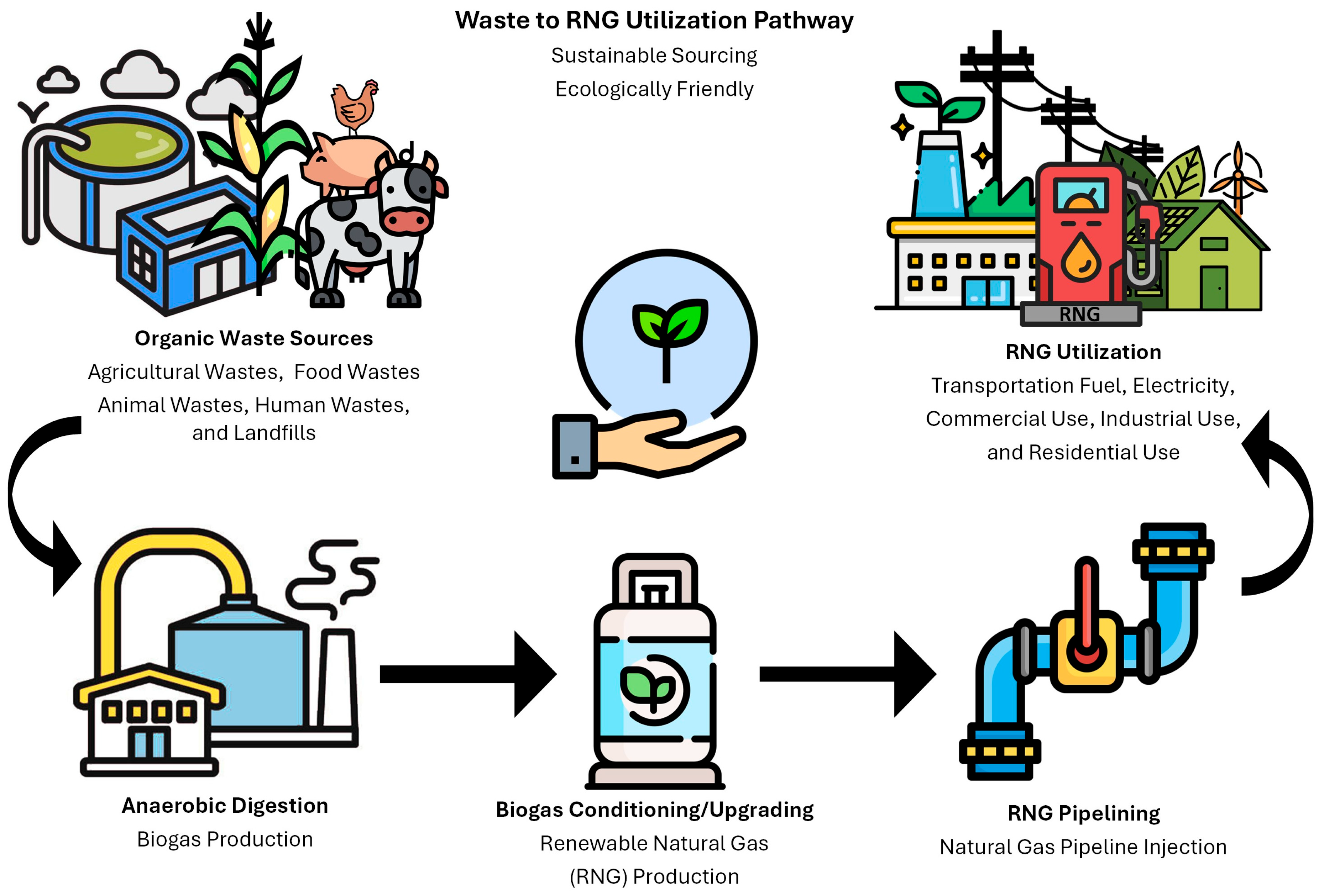

The production of renewable natural gas (RNG) begins with the utilization of organic waste materials, which can include agricultural waste, food waste, animal waste, landfilled materials, and wastewater sludge. These materials are rich in organic matter, making them ideal feedstocks for the production of biogas, a product of anaerobic digestion. Anaerobic digestion is a biological process that occurs in the absence of oxygen, where microorganisms break down this matter to produce biogas. Compositionally, biogas is a mixture of methane (CH4), carbon dioxide (CO2), and other trace contaminants [1,2]. Biogas may be produced from engineered anaerobic digesters and/or landfills with technically any system (swamps, storage bins, etc.) that supports anaerobic bio-decomposition of organic wastes into biogas. However, anaerobic digesters and landfills are by far the most common source of biogas capable of being captured and converted into RNG and/or other products.

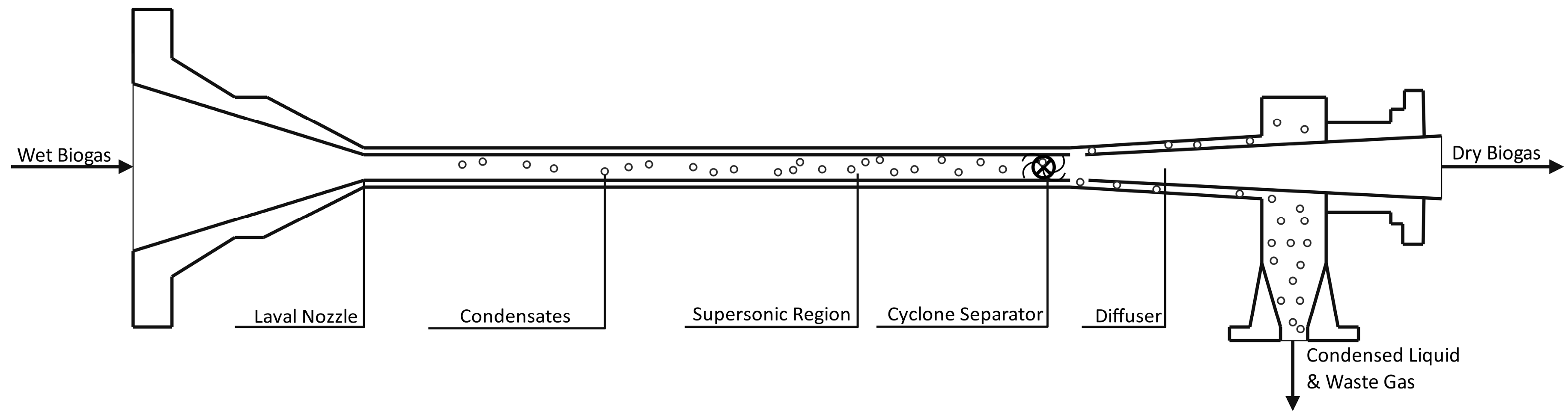

The process not only generates biogas but also results in nutrient-rich digestate in the case of digesters and leachate in the case of landfills. However, for the remainder of this paper, anaerobic digesters will be the featured process for production of biogas; yet, the conversion of biogas into RNG is not very dependent on biogas production source. In addition to the target biogas, this residual product from digestion can be used as a fertilizer, promoting a circular economy through waste utilization [3]. Once generated, biogas undergoes conditioning/cleaning, where the impurities of the raw biogas are reduced/removed. Biogas, for most applications, requires further treatment or “upgrading” for higher removal of contaminants to produce a higher quality biomethane [4]. Upgrading is an important step and the variable that changes biogas into what is commonly referred to as RNG. See Part I, a separate analysis paper in conjunction with Part II, for a discussion of the current technologies and methods utilized in the conditioning and upgrading of biogas. After obtaining RNG through upgrading, the prospect of pipeline injection of this stream into existing infrastructure can be achieved, and this alternative fuel source can be used in many applications (i.e., fuel, electricity, etc.). Figure 1 visualizes the waste to RNG utilization pathway. Some key advancements in RNG production are the varied improvements of anaerobic digestion technologies. Traditional anaerobic digesters have been enhanced with advanced process control systems, improved reactor designs, and the integration of pre-treatment methods that increase the efficiency of biogas production [5,6,7]. For instance, thermal hydrolysis and mechanical pre-treatment can break down complex organic molecules, making them more accessible to the microorganisms involved in anaerobic digestion. Additionally, co-digestion of multiple feedstocks has been shown to improve biogas yield and process stability [1,8,9]. Emerging technologies in RNG production are revolutionizing the industry by enhancing efficiency and scalability. Major players in the growing sector, such as cryogenic separation, methane enrichment in situ, and hybrid processes (i.e., combining multiple treatment processes), are allowing for significantly improved biogas yields from various feedstocks [10,11,12]. In the industrial sector, RNG applications are expanding rapidly and can be utilized for electricity generation, heating, and as a low-carbon fuel source [13,14]. Developing technologies focus on improving biogas upgrading processes, and these advanced systems are becoming more efficient and cost-effective. Additionally, process equipment design is evolving to include modular and scalable systems that can be easily integrated into existing waste management and energy infrastructure. These developments not only improve the economic viability of RNG but also contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and promoting sustainable energy solutions.

Figure 1.

Waste to Renewable Natural Gas Utilization Pathway.

The global market for RNG is projected to see substantial growth and is anticipated to expand at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 44% from 2023 to 2028 [15]. This growth trajectory reflects increasing investments and advancements in RNG technologies worldwide. By 2031, the market is expected to rise from $15.6 billion in 2023 to approximately $127.25 billion, driven by diverse applications across sectors such as energy generation, transportation, and industrial processes [16]. This rapid expansion is fueled by growing environmental awareness, stringent regulations favoring renewable energy sources, and technological innovations that enhance the efficiency and scalability of RNG production and utilization processes. As industries and governments prioritize sustainability goals, RNG continues to emerge as a crucial component in the transition towards cleaner energy solutions. More recently within the USA, due to the updates within the One Big Beautiful Bill of 2025 toward enhancing the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, RNG will emerge as a leading feedstock toward clean hydrogen production; thereby, opening even larger RNG markets and new tax credit incentives [17,18,19,20,21].

Thus, the objectives of this work are:

- Review emerging technologies;

- Review developing technologies;

- Discuss case studies and process design.

2. Emerging Technologies for Biogas Treatment and Upgrading

In addition to the traditional methods for biogas upgrading and treatment detailed in Part I, other upgrading process options are emerging on the commercial scene because of continuous academic and industrial R&D efforts. This paper, Part II, explores the emerging and developing technologies in the production, purification, and utilization of RNG, highlighting the innovative advancements that are driving the sector forward. These new methods are based on cryogenic separation, in situ methane enrichment, and hybrid technologies (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Emerging Technologies for the Improvement of Clean Biogas.

2.1. Cryogenic Separation

The field of cryogenic biogas treatment has only recently been developed, but there are already a few commercial plants in operation [22]. It comprises several different processes and has been used for a variety of tasks, including:

- Removal of trace contaminants, mainly in the context of landfill gas;

- Extraction of major components such as CO2 (gas upgrading);

- Condensation of upgraded RNG for conversion into bio-based liquified natural gas (LNG) (i.e., liquidized biogas (LBG)).

This technology is based on gradually decreasing the temperature of raw biogas to a determined temperature under constant pressure, thus separating the methane from other gases contained in the biogas. Carbon dioxide has a boiling point of −78 °C while methane’s is −160 °C, resulting in CO2 separation from biogas when cooling to these temperatures. Condensation temperature differences can also be exploited to separate other gases, such as N2, O2, and siloxanes, from biogas through condensation and distillation [22,23,24,25,26,27,28].

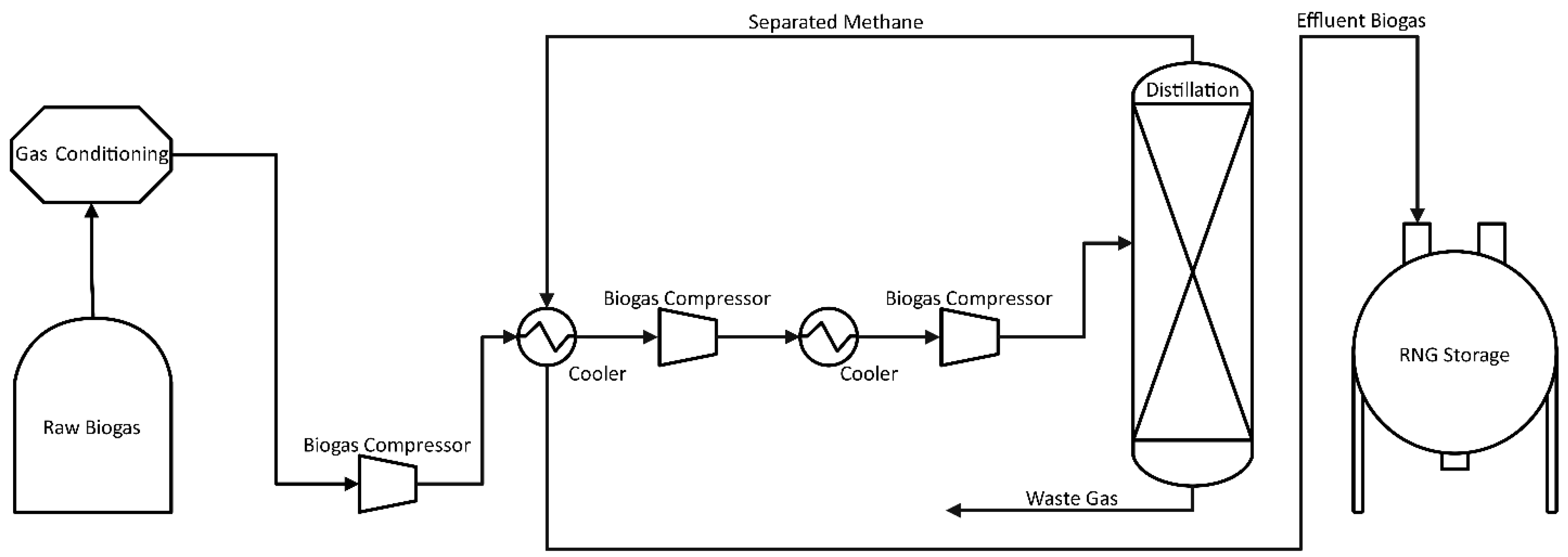

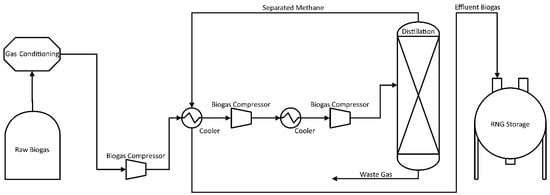

Cryogenic separation, as detailed in Figure 2, is initially carried out by drying and compressing the raw biogas up to 80 bar, followed by a drop in temperature down to −110 °C [29]. This reduction in temperature is performed in a multi-stage cooling process. First, the process removes the majority of CO2 as liquid, then it is further cooled, and the remainder for separation is dry ice (solid CO2) [30]. Impurities (H2O, H2S, siloxanes, halogens, etc.) and CO2, the second most dominant component of biogas, are gradually condensed, resulting in a high-value RNG over 97% CH4. The final product is called liquid biomethane (LBM) and is equivalent to LNG. The process offers more advantages with the treatment of landfill gas due to potential oxygen content in the initial biogas; production of CO2 at (98%) and high purity methane with less than 1% loss is possible. The resulting gas can be used directly for vehicles or injected into the distribution network [31]. The main disadvantage of the technology is the high energy consumption during gas compression and cooling, with power requirements equal to 5–10% of the produced RNG energy content [32,33]. Despite promising results, the cryogenic separation process is still under development, and only a few facilities operate on a commercial scale [25]. High capital and operation costs, CH4 losses, and operational problems (e.g., plugging) resulting from the formation of solids, such as dry ice (CO2) and water ice, are hindering the wider establishment of this technique [25,28,29].

Figure 2.

Process Flow Diagram of Cryogenic Separation for CO2 Removal.

2.2. In Situ Methane Enrichment

A new approach to cryogenic distillation is presented by Yousef et al., where the implementation of increased operating pressures, adjustment of reflux ratios, and utilizing two separate columns resulted in frosting mitigation, increased productivity, and increased purities. The compositions achieved in this study were 97.12% by mole CH4 with 99.92% by weight CO2 [34].

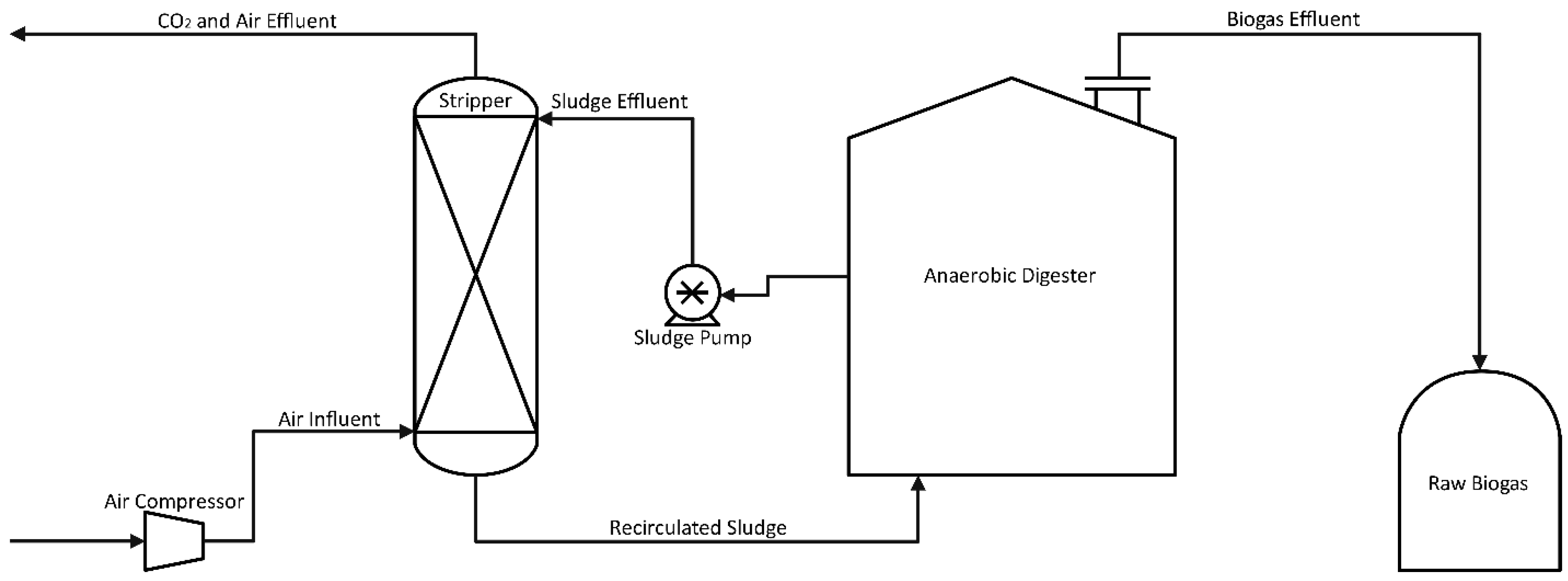

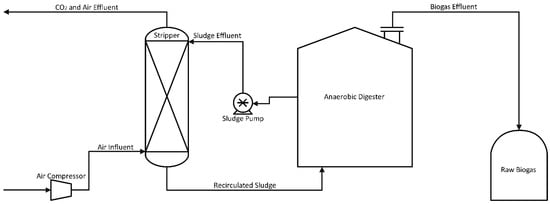

Due to risk mitigation of operational hindrances, such as freezing and inefficiency, this technology is becoming a more viable option for large-scale operations. In situ methane enrichment technology was discovered more than 20 years ago, yet it is still being tested at the pilot scale [33]. The process goal is to remove CO2 before it accumulates at levels high enough to dilute methane. An example process is shown in Figure 3, where slurry from a running digester is circulated out of the main chamber to a counter-current air contact column. Dissolved CO2 in the sludge is stripped from the solution and carried out with the air mixture while the remaining sludge is recycled back into the system [35]. Although small amounts of oxygen are present in the returned sludge, facultative anaerobes quickly consume any dissolved oxygen (DO). It is possible to obtain biogas using this technology with a methane content of 95% and a methane loss of less than 2% [36].

Figure 3.

Process Flow Diagram for Enrichment of Methane in situ.

Ascue et al. performed a pilot study with two different sludges in various configurations. Data for these raw sludge types is presented in Table 2. The study produced biogas with 87% CH4, 2% N2, and the balance CO2 with no oxygen present [37]. Despite being a profitable technology compared to conventional implementations, it has only been used at small biogas plants [5]. One possible reason for the minimal use of this technology is that during the enrichment of methane in situ, the pH of the sludge increases to around 8, which shifts the metabolic pathways for CH4 production. It is believed this pH change results from the loss of disassociated CO2 as an acidic component in solution [38]. In situ, enrichment also requires potentially large sludge flow rates to circulate through the stripping column. Simulations of pilot scale studies with a 2000 m3 digester show sludge flow rates of at least 2500 m3/day are required to achieve methane purity over 92% [37].

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics of Sludge from In Situ Methane Enrichment [37].

2.3. Hybrid Technologies

Hybrid technologies seek to take advantage of key positive aspects of mature technologies to improve biogas while overcoming some of the technological disadvantages. Hybrid processes for capturing CO2 (membrane absorption, cryogenic membrane, cryohydrate, etc.) have received increasing attention [39,40,41,42]. Hybrid technology combines the advantage of, for example, the permeability efficiency of gas through membranes with conventional separation technologies such as washing with water under pressure, absorption with amines, and cryogenic separation. Hybrid technologies have been demonstrated to achieve economic feasibility at targeted purity levels [43,44,45].

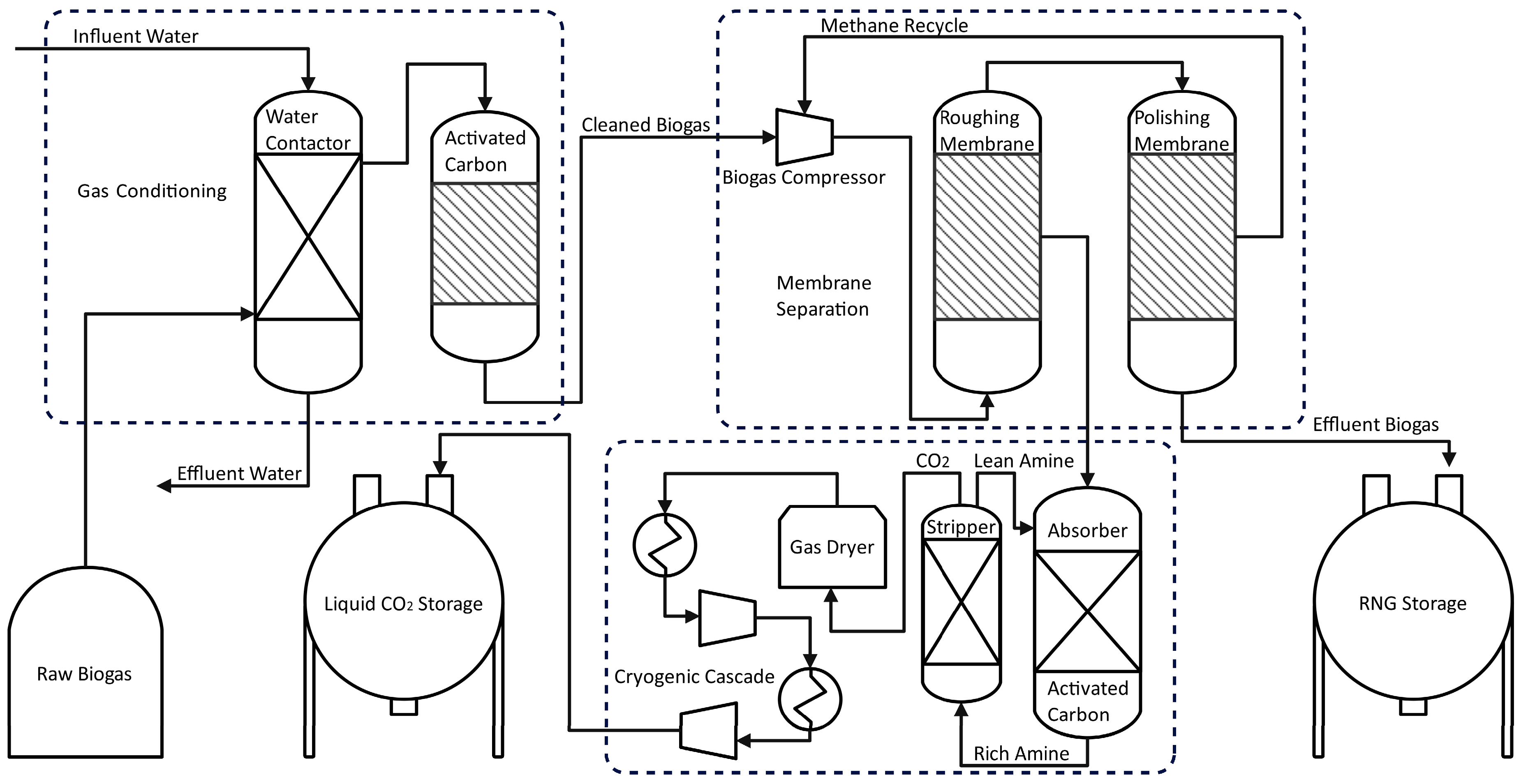

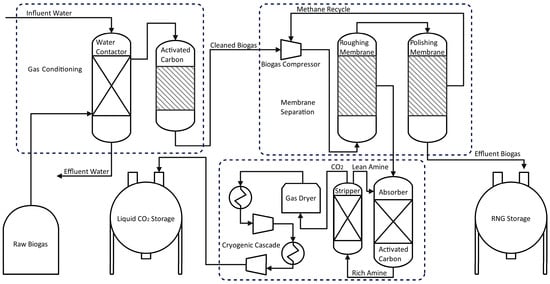

Pentair Haffmans® (Venlo, The Netherlands) has commercialized an advanced hybrid process for treating biogas by combining separation with membranes and cryogenics. The biogas is processed to achieve almost pure CH4 with a 100% methane recovery and 99% CO2 removal. Carbon dioxide is liquefied and stored in tanks until use as a value-added product. This hybrid technology seeks to make the process less energy-intensive [22,46].

Figure 4 shows the flow diagram of water washing/adsorptive/membrane/cryogenic hybrid technology. In the first stage, raw biogas is fed to a water-washing column to eliminate ammonium and other water-soluble compounds. Subsequently, the gas passes through an activated carbon filter where hydrogen sulfide and other impurities are removed [47,48]. The upgraded biogas is compressed to 10 bar before entering a membrane, which removes CO2 and yields a methane stream of over 97% purity. The liquefaction of CO2 is achieved by filtering, drying, and cooling at temperatures below −24 °C and 17.5 bar [46].

Figure 4.

Flow diagram for Hybrid Enrichment Process of CH4 & CO2.

3. Developing Technologies for Biogas Treatment and Upgrading

Table 3 lists some of the more promising technologies for developing biogas treatment and upgrading. All of these processes have mechanisms deemed viable and applicable for use as an upgrading system; however, due to process immaturity or other factors, have not been commercially adapted for market use.

Table 3.

Developing Technologies for Improvement of Biogas.

3.1. Industrial Lung

This system is based on the CO2 conditioning operation of living organisms where carbonic anhydrase (CAH) enzymes in blood catalyze the dissolution of carbon dioxide formed during cellular metabolism. Equation (1) shows the reaction catalyzed by anhydrase.

Dissolved carbon dioxide, in the form of carbonate, is then transported to our lungs, where the catalytic enzyme generates carbon dioxide and water by the reverse reaction. A research group in Lund, Sweden, studied the use of hydrase to upgrade biogas. They added six histidines sedimented to attach the enzyme to a solid carrier. A standard counter-current absorption column setup is used to treat pre-cleaned biogas captured by the enzyme into an aqueous phase. The CO2-rich enzymatic absorbent is regenerated by heat in a separation column, where it releases a stream of >90% CO2. Combining technologies such as membrane, cryogenic, and temperature swing allows for lower energy consumption compared to the individual processes alone [49]. The study showed that biogas can be purified to 99% CH4. The production cost of the enzyme remains high, and the viability of the process is affected by the life of the immobilized enzyme [22,36]. CO2 Solution Inc. is a Canadian company that has developed this technique and has a patent for a pilot-scale bioreactor that uses the enzyme to capture carbon dioxide [50].

3.2. Supersonic Separation

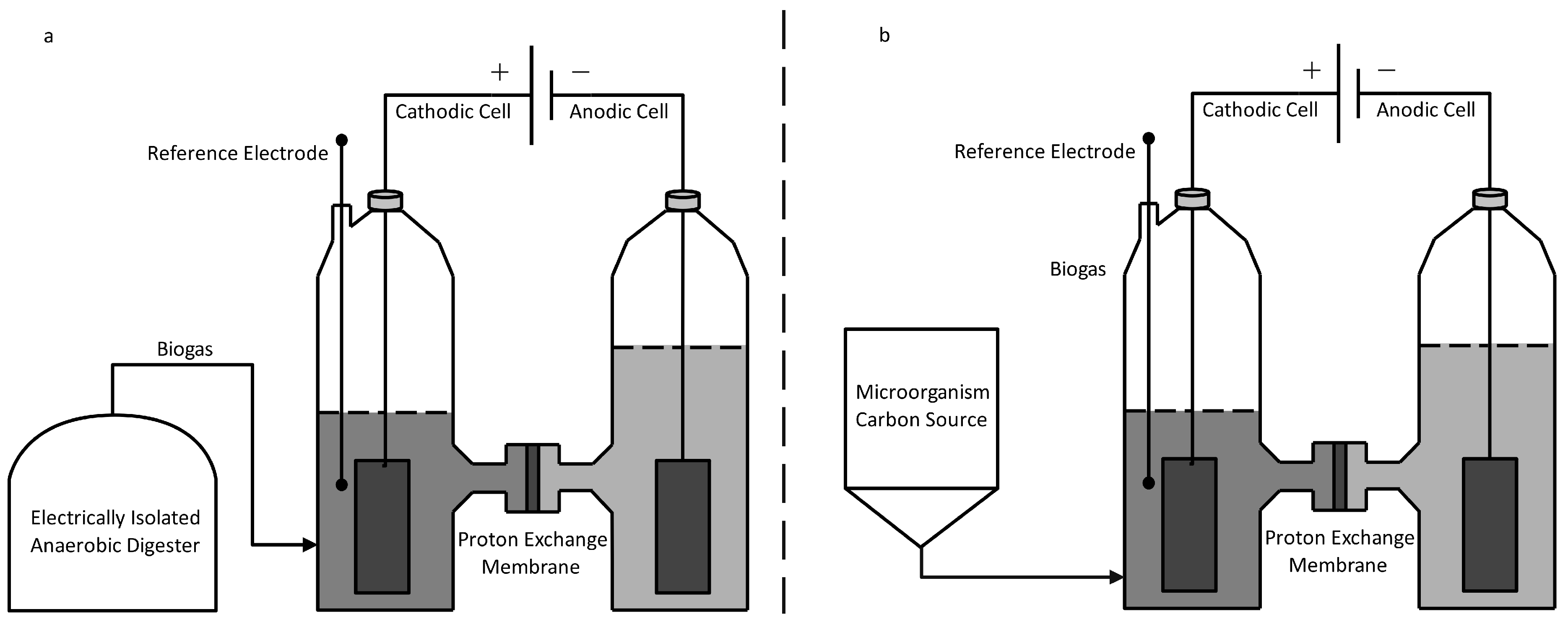

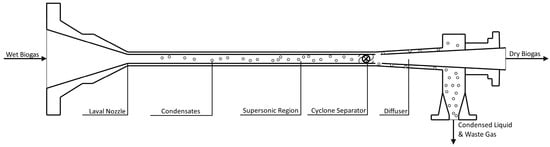

Supersonic separation of gas species is a technology that eliminates one or several gaseous components in a mixed gas by condensation during expansion through a Laval nozzle [51]. Figure 5 shows a general system configuration where the gas exits a nozzle at a supersonic velocity, which condenses components with high molecular weight. Produced condensates are separated from dry gas through an integrated gas/liquid cyclonic separator with pressure as an energy source. The difference in condensation temperatures can be seen for various pressures. At a given pressure, the condensation temperature is higher for CO2 than CH4, causing preferential condensation from the gas stream. This gas upgrading technology has been used to condense and separate water from natural gas hydrocarbons but has not seen widespread use in biogas systems. Simulations show energy losses are significant, with Bian et al. reporting influent pressures of 6 MPa dropping to 0.8 MPa at dry gas effluent [51]. This technology holds significant promise for the simultaneous separation of CO2 and H2S in biogas due to their vapor pressure differences relative to methane [22,52].

Figure 5.

Supersonic Separation of Heavy Components from Biogas [53].

3.3. Chemical Hydrogenation Process

The chemical hydrogenation process is based on Sabatier’s Reaction, as seen in Equation (2). Catalysts such as nickel and ruthenium have been developed to remove carbon oxides in ammonia and natural gas for industrial applications where they are applied at high temperatures (300 °C) and pressures (ranging between 5 and 20 MPa) [54,55]. The selectivity toward the products of this chemical process is high, which allows for a complete CO2 and H2 conversion to CH4 and H2O [54].

Despite the high efficiency of the procedure, there are still specific drawbacks to upgrading biogas. For example, trace gases in biogas poison catalysts significantly reduce activity life and make it necessary to replace catalysts faster than natural gas applications. Hydrogen sulfide is a well-known catalyst poison for methanation systems and must still be removed via gas conditioning [56]. Ammonia was at one time regarded as a catalyst poison as well and targeted for removal. However, recent results using low-concentration (100 ppm) NH3 streams indicate it could provide protective effects against coke formation [57]. Another technical challenge is the high energy required to maintain operational conditions [23]. Simulations of multiple reactor configurations and system requirements show an energy efficiency of up to 59% for biogas production to RNG standards [58].

3.4. Hydrate Formation

Hydrates are particles in solid form that can be compared with ice and can cause problems in petroleum well operations. The formation of hydrates takes place due to reactions between water and hydrocarbons or other trace compounds at low temperatures and high pressures in oil & gas wells. These include methane, ethane, propane, hydrogen sulfide, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide. A variety of gas hydrate research has been carried out since the recognition that the cause of obstructions in pipelines during the transport of natural gas was mainly due to the formation of gas hydrates between water, methane, ethane, propane, and other light hydrocarbons [59]. Two studies, Yoon et al. and Kang et al., investigated the formation of hydrates based on ternary systems of phenol-carbon dioxide-water and CO2–H2–H2O behavior, respectively, at different temperatures and pressure ranges [59,60].

Tajima et al. modeled the formation of hydrates to capture hydrofluorocarbons (R134a), SF6, and CO2 with mixtures of nitrogen or air. They estimated the energy consumption of the total process as 0.853 kWh/kg CO2 recovered with a net CO2 emission of −0.466 kg/kg from consumed energy [61]. This study has attracted other researchers to consider using this technology to reduce CO2, H2S, and other contaminants from biogas and synthesis gas streams [24].

Wang et al. performed an experimental study on the separation of hydrogen at different concentrations from refinery gas mixtures (H2 and CH4) using the hydrate removal technology at a temperature slightly higher than 0 °C and a pressure less than 5 MPa, along with small quantities of additives and anti-caking agents to disperse the hydrate particles in the condensate [62]. It has been used successfully to assess whether methane can be purified from a mixed gas stream using selective CO2-hydrate formation. They conclude that gas hydrates can be used to decontaminate natural gas, as 25% of CO2 can be reduced to 16%, although the remaining CO2 is still high for RNG [63].

Continuous experiments for CO2 separation have been recently carried out by Horii & Ohmura using separation systems comparable to chemical absorption. These include Tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBAB) in hydrogen-water hydrate systems (H2 + CO2 + H2O + TBAB) as well as the more common H2 + CO2 + H2O. This successful implementation of a continuously operational process serves as a base for hydrate-based fuel gas purification advancement, from critical laboratory-scale studies to industrial-scale methods [64].

3.5. Biological Technologies

Biological technologies that hold promise for use in biogas upgrading are usually classified as the following:

- Chemo-autotrophic methods using in situ microbial communities;

- Photo-autotrophic methods;

- Biogas upgrading through fermentation processes;

- Biogas upgrading through microbial electrochemical methods.

These technologies have been experimentally proven to hold promise as future upgrading options and are currently at an early stage of implementation at pilot and full scale. These methods have the main advantages of operating under moderate pressure and temperature, and the CO2 is transformed into other value-added products like lipid and protein-laden biomass. This significantly contributes to and enhances a move toward more bio-sustainable economic development [23,33].

3.5.1. Chemo-Autotroph Methods

The process of chemoautotrophic biogas upgrading involves hydrogenotrophic methanogens, which convert CO2 into CH4 by using hydrogen H2. Angelidaki et al. give Equation (3) as an example [23].

In Situ Biological Improvements. This improvement is implemented onsite where hydrogen (H2) is injected into a biogas reactor and coupled with CO2 produced in the anaerobic digester for CH4 production by the action of autoclastic methanogenic Archaea [65]. In this technology, it is important to control the pH since values above 8.5 inhibit methanogenesis. Under tightly controlled conditions, carbon in the form of methane can be recovered by as much as 99%. Luo et al. studied the possibility of converting hydrogen and CO2 into methane during batch trials in a fully mixed biogas reactor fed with manure and hydrogen at a pH of 8.3 [66]. They obtained yields of 65% methane from the input carbon mass via CO2 conversion. During co-digestion with acid cheese serum, the pH remained below 8, and carbon conversion to methane increased up to 75% [67]. By modifying bubble-free gas transfer through a hollow fiber membrane module (HFM), the CH4 content was higher than 90% in biogas when pH values between 7.6 and 8.3 were used [68].

Wang et al. developed a new method for simultaneous biomethanisation with coke oven gas (COG) and in situ upgrading of biogas in an anaerobic reactor [62]. Simulated coke oven gas (SCOG) (92% H2 and 8% CO) was injected directly into the anaerobic reactor that treats sewage sludge via the HFM. With a controlled pH of 8.0, the H2 and CO2 additives were completely consumed with no adverse effects on the anaerobic degradation of sewage sludge. The maximum content of CH4 in the biogas in this study was 99% [62]. Bassani et al. studied the biological conversion of H2 and CO2 to CH4 in an influent composed of residual potato water through an innovative configuration. A UASB granular reactor was connected to a separate chamber where they injected H2 to mediate efficient transfer to the liquid phase using a pH of 8.38. They obtained 82% methane yield from the CO2-based carbon input [69]. Mulat et al. studied the in situ upgrading of biogas in batch-operated reactors fed with maize leaf substrate and periodically supplemented with H2. They reported methane values of 89.4% in a pH range between 7.0 and 8.0 [70]. Agneessens et al. assessed the influence of pulse injections with H2 in the microbial community, and the yields of anaerobic reactors fed with straw and mesophyll sludge from a biogas plant. Using a pH of 7.9 and a total solid content of 4.2%, they obtained a methane yield of 98.9% [71].

The oxidation of volatile fatty acids (VFAs) and alcohols presents a process control challenge, as it is beneficial to organisms solely under conditions of low H2 concentration [72]. On the other hand, high levels of H2 (>10 Pa) inhibit anaerobic digestion and promote the accumulation of electron sinks such as lactate, ethanol, propionate, and butyrate [73,74]. Mulat et al. assessed the effect of excess H2 on the overall performance of the process. The results showed that the excess addition of H2 allows the accumulation of H2, CO2 depletion, and inhibition of the degradation of acetate and other volatile fatty acids (VFA) [70]. VFA accumulation can lead to bioreactor insufficiency in degradation, deteriorating the system due to large quantities of H2 and excess acidification [72]. A recent study concluded that injection of H2 into batch reactors at a concentration exceeding the stoichiometric amount for methanogenic hydrogenotrophs led to an accumulation of acetate [71]. This accumulation could be attributed to the homoacetogenic stimulated route, and/or decreased methanogenic activity from actoclastic Archaea. Over time, H2 exposure reversed inhibition by improving stated H2 through a higher hydrogenotrophic methanogen populace [75].

Active mass transfer between gas–liquid interface is dictated by the aqueous solubility of the gas, which in many cases is low, and can result in low efficacy of bioreactors [76]. Transfer of H2 into the liquid phase is limited to the gas/liquid interface and a limiting factor for microorganisms. Careful analysis is required of variables related to the advancement of in situ biogas processes such as improved reactor design, injection methods of H2, and recirculatory gas flows [69]. In batch experiments, Agneessens et al. found that the absorption rate of H2 decreased rapidly when headspace CO2 concentrations were <12%. This corresponds to a decrease in daily methane production and seems to be a limiting factor in biological systems. The biogas produced in this setup reached a peak methane concentration of 89%, but further processing is needed to align with RNG specifications [71].

Luo and Angelidaki utilized hollow fiber membranes within continuously fed bioreactors to inject H2 into livestock manure and cheese whey/serum treatment anaerobic reactors, resulting in a biogas purity of 96% methane [68]. In a separate study using an anaerobic sludge blanket reactor with upward flow, a hollow fiber membrane was incorporated into an external gas removal system. Methane obtained from the in situ biogas upgrading was 94% purity [77]. However, the high cost of such membranes hinders real-scale applications. Studies have revealed that ceramic sponges, as a more affordable porous option, effectively enable the autoclastic coupling of CO2 and H2, followed by their conversion to CH4, all at a lower expense [69].

Ex Situ Biological Upgrading. This type of biogas upgrading is based on injecting CO2 and H2 gases (taken from external sources) into an anaerobic reactor containing hydrogenotrophic culture (pure or enriched) to transform the gases into CH4 [65]. This method has several advantages:

- Ensures the stability of the conventional biogas process;

- No degradation of the organic substrates (hydrolysis and acidogenesis are avoided);

- Independent culture isolated from the biogas process;

- Can use another external source of CO2 (e.g., synthesis gas) to make the process more flexible.

The ex situ process considers different types of factors influencing the transformation of CO2 and H2 into CH4. In some studies, like Angelidaki et al., it is reported that factors such as reactor configuration/types, liquid media composition, temperature, gas retention time, gas recirculation rate, and pH all impact system performance [23]. Various sources report gas transformation ranges on the order of 33–100% for CO2, over 89% for H2, and methane concentration between 79 and 98% [65,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88]. The bulk of these studies all state that the greatest technical challenge is the low rate of gas transfer within these gas–liquid systems.

Biological Upgrading Using Microbial Consortia. Properly established microbial consortia with appropriate consortium members being present in sufficient concentration plays an important role in the overall effectiveness of anaerobic digestion upgrading systems using mixed cultures. Two processes take advantage of the qualities of microorganisms:

- Archaea hydrogenotrophic methanogens facilitate the conversion of CO2 to CH4 via external H2 as an electron donor, effective at a 7 pH [89].

- The Wood-Ljungdahl mechanism, outlined in Equation (4), provides an indirect pathway, driven by homoacetogenic bacteria, relies on the exergonic transformation of CO2 into acetate.

As shown in Equation (5), the low energy gain in the process is compensated by Archaea methanogens that convert the acetic acid into CH4 [23].

As discussed previously, the concentration of H2 affects the balance of biochemical reactions. The addition of external H2 sources exerts a strong selective pressure on the microbial community, with a massive increase of hydrogenotrophic methanogens and homoacetogenic species that produce acetate. Examples of microbes include Acetobacterium woodii, Moorella thermoacetica, and Clostridium [90]. However, the exogenous addition of H2 is responsible for inhibiting the syntrophic acetate-producers (involved in the degradation of propionate and butyrate) and syntrophic acetate-oxidizing microorganisms [91].

The hydrogenotrophic methanogens genus most frequently found are Methanobacterium, Methanoculleus, Methanomicrobium, and Methanothermobacter. Methanosarcina and the acetoclastic methanogens are generally less abundant [67,70,71,79]. A new species of hydrogenotrophic bacteria, abundant in thermophilic reactors, was recently given the interim name Candidatus Methanoculleus thermohydrogenotrophicum [92]. In hydrogen-assisted methanogenesis, the diffusion of H2 into the liquid medium is often the limiting factor, rather than the biological conversion carried out by microbial species [93]. Gene expression of biogas reactors demonstrated hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis, which can clarify a potential reason for increased productivity when utilizing H2 in conjunction with methanogens [94,95].

3.5.2. Photo-Autotrophic Method

This gas upgrading technology is based on the recovery of methane through a biotechnological process utilizing photo-bioreactors and Photo-autotrophic organisms such as cyanobacteria, eukaryotes, or microalgae. There are different types of photo-bioreactors used to support these microorganisms; some are closed photo-reactors, such as tubular reactors made of photo-transmissive materials, and others are open ponds. Photoautotrophs consume CO2 efficiently using solar irradiation, water, and nutrients to produce biomass, oxygen, and heat. Some can also use other biogas contaminants, such as hydrogen sulfide. Species have been studied that upgrade biogas, resulting in CH4 levels ranging from 64.7 to 97.2% while removing H2S and CO2 with 66.7–95% efficiency. Example microorganisms reported to have been successfully utilized include Chlorella vulgaris, Planktolynga brevicellularis, Stigeoclonium held, Limnothrix planktonica, Picochlorum sp., Halospirulina sp., Scenedesmus sp., Mychonastes homosphaera, Geitlerinema sp., Staurosira sp., and Chlorella sp. Other species instead only remove CO2, which still allows recovery of CH4 in combined systems but requires pre-conditioning of the biogas (Scenedesmus obliquus, Neochloris oleoabundans, and Nannochloropsis cadiz) [96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105]. In these processes, managing operational factors like dissolved oxygen levels, light wavelength and intensity, temperature, photoperiods, and the retention time (gas hold-up) of input gases is critical for optimal performance. [28,103,106,107]. Artificial LED light appears to be promising for the improvement of biogas when compared to natural sunlight due to regulated light wavelengths. Additionally, factors such as nutrient availability, pressure, and microbial community dynamics can also significantly influence process efficiency. An additional benefit of this method is the generation of active biomass. This biomass can be used to extract valuable products like lipids and proteins, as noted by Guedes et al., or serve as raw material for biogas production through digestion [108,109]. A shortcoming of this technology is the potential interruption of irradiation. In wastewater treatment processes, the lack of sterility and suspended solids could adversely impact this particular treatment of biogas [45].

3.5.3. Fermentation-Based Biogas Upgrading

The hydrolysis of solid biopolymers (cellulose, hemicellulose, etc.) to monomers and oligomers, and their subsequent conversion through fermentation reactions with undefined mixed cultures are an option for improvement in biogas upgrading. During primary fermentation, sugar substrates are converted to pyruvate. When insufficient oxygen is available, or the organism is unable to continue with the oxidative process, pyruvate utilization follows an anaerobic fermentation route. In this way, the pyruvate is reduced, allowing regeneration of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (oxidized form: NAD+) molecules that were consumed in the previous processes. All equivalents should be re-oxidized through the reduction of H+ by either (a) NADH oxidation; or (b) NADH oxidation (reduced form) through the reduction of pyruvate or its oxidized organic derivatives (propionate, lactate, butyrate, ethanol), depending on the partial pressure of hydrogen [110]. For example, bacteria and yeasts can operate within fermenters to yield a variety of products, such as ethyl alcohol. During ethanol fermentation, pyruvate is first converted into acetaldehyde and then into ethanol and carbon dioxide by the intervention of enzymes such as decarboxylase, alcohol dehydrogenase, and NADH [111,112]. Fatty acids such as acetate and butyrate, produced during fermentation, are important precursors for the synthesis of liquid biofuels through lipid formation [111,113,114].

While several studies have explored the generation of liquid products from CO2 and H2, few have investigated the application of this process for biogas upgrading [23]. Yet the potential is there, with several mechanistic routes possible. Most commonly, this process involves feeding CO2 and CH4 as co-metabolites as the organisms consume their primary sugar source. Microorganisms such as Acetobacterium woodii, Butyribacterium methylotrophicumn, and Clostridium scatologenes can convert CO2 and H2 into liquid value-added products [115]. Most of these microorganisms are acetogens, which assimilate CO2 by the Wood-Ljungdhal pathway (also known as a reductive acetyl- CoA pathway) [116]. Isolated from a continuously stirred tank reactor (CSTR) treating organic sewage, a homoacetogenic strain, Blautia coccoides GA-1, can produce acetate using CO2 and H2. This organism was capable of acetate yields up to 5.32 g/g dry weight after 240 h of incubation [117]. It was further shown that the presence of fermentable organic compounds such as glucose could notably decrease autotrophic metabolism. While the complete absence of glucose results in the largest amount of H2 utilization, B. coccoides GA-1 shows no significant difference in H2 uptake when glucose concentrations are below 600 mg/L [117]. A gas-bed reactor was used to study the production of ethanol from low-quality synthesis gas (SynGas), with Clostridium ragsdalei serving as the microbial catalyst. SynGas used in this study was 38% CO, 28.5% CO2, 28.5% H2, and balance N2. While commercial SynGas tries to minimize the content of CO2, this study was successful in using the unwanted CO2, producing ethanol (5.7 g/L) and acetate (12.3 g/L) [118].

Compared to fermentation using pure cultures, fermentation with mixed cultures for converting CO2 and H2 is also possible and has potential advantages. These include the absence of sterilization and the possibility of using wastewater for the supply of nutrients, both of which could result in significant cost savings. Earlier research has supported the ability of mixed cultures to convert CO2 and H2 into acetate [119,120]. However, due to the high solubility of acetate, its separation from the liquid phase requires significant energy, which presents a challenge. To address this limitation, researchers have proposed the production of medium-chain fatty acids, such as caproate and caprilate, from CO2 and H2. These acids not only offer a higher fuel value than bioethanol but are also more easily separable from the liquid medium. In a hollow fiber membrane reactor with mixed cultures, caproate (0.98 g/L) and caprilate (0.42 g/L) were successfully produced. However, acetate (7.4 g/L) and butyrate (1.8 g/L) were also generated at higher concentrations, highlighting the challenge of achieving high selectivity for medium-chain fatty acids in such operations [114,121,122].

There is a need for further research to understand how impurities like H2S in biogas affect fermentation systems and to explore methods for enhancing product selectivity. Kozlowski et al. applied dosing of PIX 113, an iron-based coagulant, on mesophilic fermentation and found that it is capable of reducing the composition of H2S in biogas while avoiding degradation of the digestion process [123]. This process can potentially provide an adequate addition to existing desulfurizing operations.

Upgrading biogas by converting CO2 with externally added H2 requires inexpensive and easily accessible hydrogen sources, which remains a significant challenge. Alternatively, fermentation processes can use CO2 in combination with sugars to produce carboxylic acids like succinic acid. For instance, during the fermentation of glucose by Actinobacillus succinogenes or other bacteria, CO2 from biogas can be converted into succinic acid. This compound serves as a versatile chemical platform and is an important precursor for producing a wide array of products in industries such as agriculture, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals, among others.

This biotransformation includes chemical products such as 1,4-Butanediol, Tetrahydrofuran, 2-Pirrolidinona, gamma-butirolactona, green solvents such as 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF), and biodegradable polymers such as polybutilene succinate (PBS) [124]. Exposing A. succinogenes to high levels of CO2 suppresses the production of unwanted fermentation byproducts and heavily favors succinate formation. The organism grows best in environments with 5–40% CO2 as headspace which matches well with biogas production [125]. Succinate yields as high as 110 g/L were obtained by Zeikus et al. using A. succinogenes with 100 mol CO2 per mol glucose. This result places production costs around $0.55/kg at scales above 75,000 tons per year [126].

The first research to explore the feasibility of upgrading biogas through integration with bio-succinic acid production, using the bacterium Actinobacillus succinogenes 130 Z, was conducted by Gunnarsson et al. These researchers showed that slight over-pressure during fermentation was advantageous in increasing CO2 solubility, therefore increasing system performance and succinic acid production. They reported a consumption rate for CO2 of 2.59 L CO2 L−1 d−1 and purity of CH4 at 95% within the biogas [127]. This process is incentivizing further research and development due to its advantages over H2-based fermentation processes which include removing H2 solubility as a factor and lower energy requirements for efficient mass transfer [66]. Studying bacterial strains for the ability to produce succinic acid can further drive this fermentation technologies forward. Some bacterial strains such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Escherichia coli, have been proven to produce succinic acid from glucose, which can lead to viability in the sector of biogas upgrading [128,129].

3.5.4. Microbial Electrochemical Methods

The elimination of CO2 from biogas to produce CH4 through bio-electrochemical systems has been investigated and presented as a sustainable and profitable way to upgrade biogas. These systems allow new sustainable methods for producing renewable energy carriers that can be stored and used for the transport, heating, or production of chemical products. The use of microbial electrolysis cells (MEC) is an emergent technology for energy and resource recovery during waste treatment that has recently received a lot of research attention tied to the promise of prior waste biotreatment utilization [63,130,131,132]. When properly configured, a standard biotreatment system can create power by extracting electrons produced through the metabolic activities of the microorganisms within a bioreactor. As seen in Equation (6), such systems are referred to as microbial fuel cells (MFC) due to their power production capability. The reverse is also possible, with methane production from microorganisms enhanced by the application of voltage potential. Equation (7) shows an example of carbon dioxide reduction to methane with externally applied voltage. An established potential of less than −0.7 volts versus a standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) can reduce carbon dioxide to methane using a two-chamber electrochemical reactor with no precious-metal catalysts needed. As such, methane can be produced directly by using either a bio-cathode and abiotic anode in electrochemical systems or MEC through a process called electromethanogenesis.

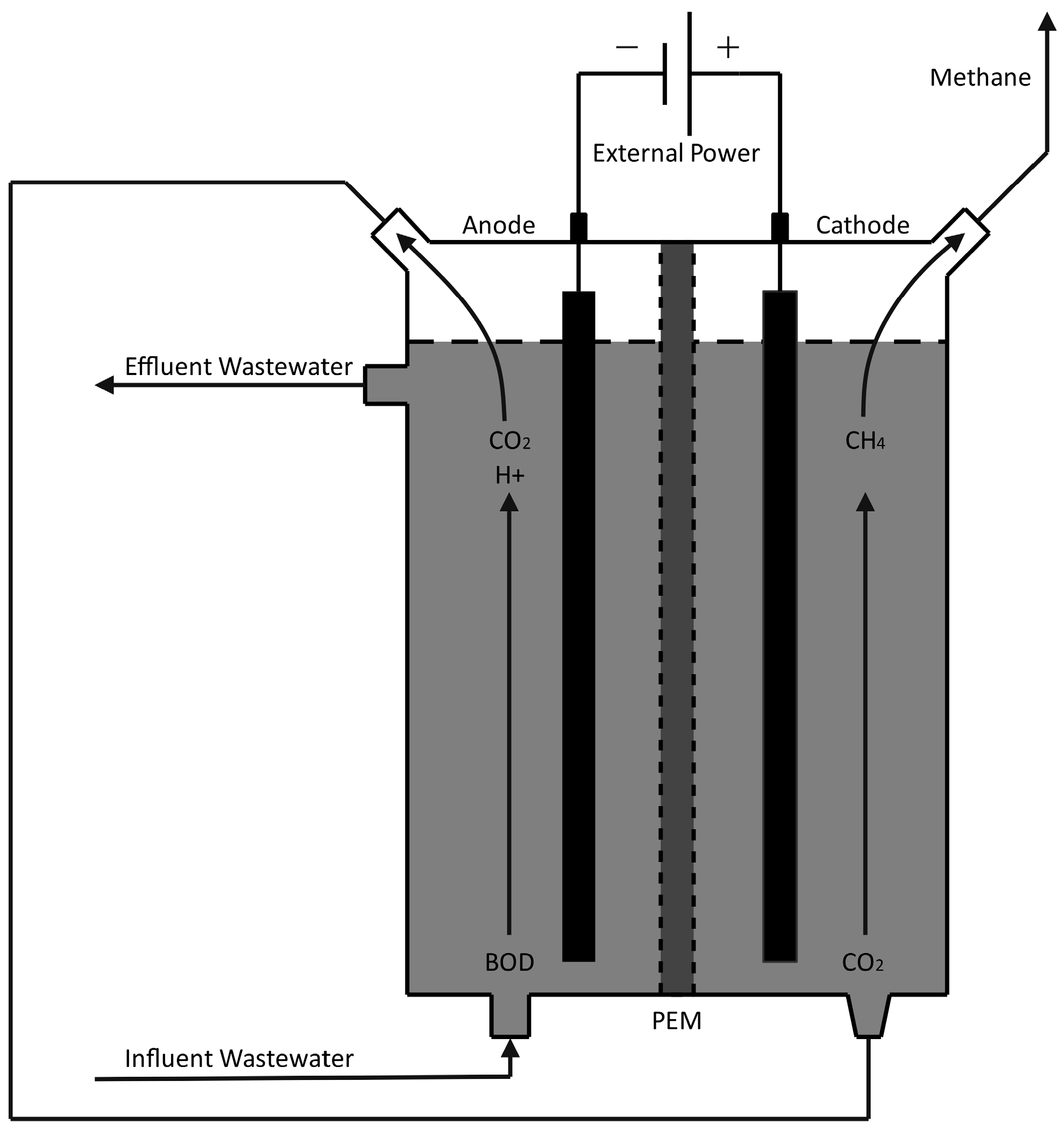

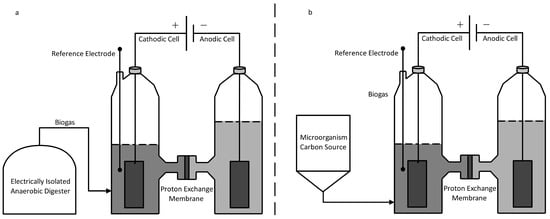

Bio-cathodes. Xu et al. studied gas upgrading via two systems; the first where biogas was introduced to an external cathodic cell and the second where a cathode itself was used as a biogas reactor [133]. Figure 6 details a similar batch setup to those chosen by Xu et al. Glucose was fed to a consortium of methanogens where CH4 was produced in an isolated digester (Figure 6a) and the cathodic chamber itself (Figure 6b). Carbon dioxide reduction to methane was carried out by methanogens and made electrochemically favorable by holding the cathode at −700 mV relative to the hydrogen electrode potential. During the 19-day experiment length, it was discovered that the elimination of CO2 by biogas upgrading with integrated cathode design (Figure 6b) performed similarly to the external method (Figure 6a) with a reduction of 8–10% vs. 50% for the initial biogas content [133]. However, the integrated design did show a doubling of CH4 production versus an external cathode (0.15 vs. 0.30 mmol CH4). Within the cathode, results discovered that methane production in addition to alkalinity generation consequential scrubbing effect caused the elimination of CO2.

Figure 6.

Bio-electrochemical System for CH4 Production and Upgrading. (a) Digestion isolated from Cathode. (b) Digestion integrated in Cathodic Cell.

Higher methane yields in the integrated system were attributed in part to increased mass transfer of in situ CO2 production versus externally bubbled CO2. While the final CO2 concentration is still too high for direct use as RNG, it does reduce the amount of processing needed, in turn converting some of the wasted CO2 into methane.

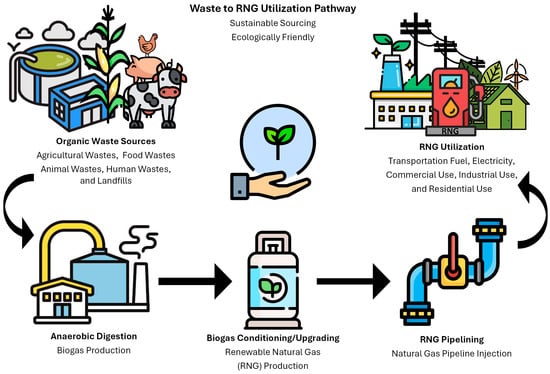

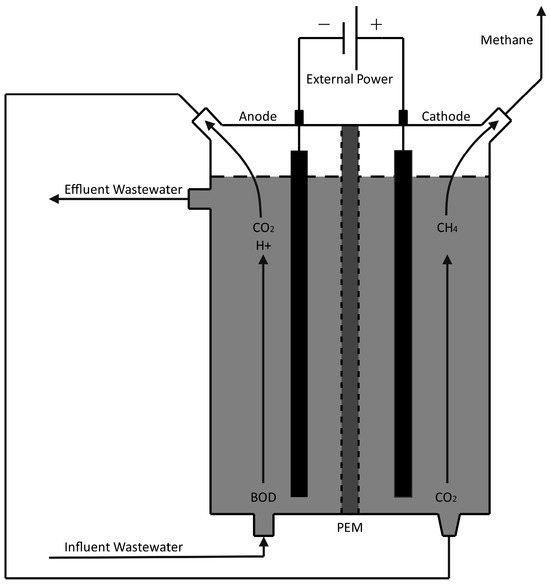

MECs. Compared to abiotic anodes and bio-cathodes, a MEC uses microorganisms on both sides of a permeable membrane and is governed by Equations (6) and (7). In principle, the voltage required to produce cathodic methane could be obtained, at least partially, in an MEC with anodic biological oxidation of residual organic materials, including diluted wastewater [130,134]. Such a system is detailed in Figure 7, where microbes on the system’s anode break down influent wastewater to produce CO2. The carbon dioxide is then pumped to the cathode chamber, where a separate microbial community reduces it to methane for biogas production. Microorganisms on the anode produce a voltage potential from wastewater degradation, which is boosted by an external power source to create electrochemically favorable conditions for methane production in the cathode.

Figure 7.

Microbial Electrolysis Cell for Direct CH4 Production.

Using cathode chambers with a carbon electrode as an electron donor and methanogenic cultures as a catalytic agent gave CH4 coulombic efficiencies of 50% at an electrical potential of −650 mV vs. SHE. Boosting the system to −900 mV with an external power supply resulted in methane efficiency exceeding 80% and an overall coulombic efficiency of 96% [134]. It was also found that oxygen generated at the anode during water oxidation could diffuse into the cathode, reducing the coulombic efficiency of the bio-cathode. Despite this, the oxygen diffusion into the cathode did not significantly impact the methane production rate. An internal resistance analysis shows that several improvements can be made to increase the energy efficiency of the technology.

- Development of high surface area electrode materials with good catalytic properties for water oxidation and suitable properties for the development of biofilms in CO2 reduction by catalysis.

- Directing the flow through a porous electrode can effectively use the surface area and decrease the mass transfer losses.

- Decreasing the distances between the membrane and electrodes further minimizes loss by mass transfer.

- A membrane which is less permeable to CO2 and CH4 should be used to increase coulombic efficiency and the methane content of the gas.

The implementation of these improvements will allow a methane-producing MEC to increase the efficiency, potential substrate use, methane yield, water, and nutrients [63,135,136,137,138].

In an MEC, the electrons released by bacteria from the oxidation of organic compounds in the anode can be combined with protons to generate hydrogen in the cathode chamber. Hydrogen formed in the cathode can then be used for biogas upgrading [132,139].

Elimination of CO2 from a concentrated gas stream has been investigated in simulation using two MECs with identical biocatalysts equipped with a proton exchange membrane (PEM-MEC) or an anion exchange membrane (AEM-MEC). The equivalents derived from anodic oxidation of organic matter were transformed into a current with an average coulombic efficiency between 53 ± 9% and 85 ± 15%, resulting in a low microbial growth between 0.17 and 0.18 g COD/g COD. The cathode compartment is continuously bubbled with a gas mixture containing 30% CO2 (balance N2) and the presence of an autotrophic hydrogenic culture. This process allowed the reduction of CO2 in bulk CH4 gas streams with a cathode capture efficiency between 47 ± 2% and 80 ± 1%, respectively. In both systems, the first mechanism of elimination for CO2 was conversion into the bicarbonate ion when high concentrations were used in the MEC cathode, supported by alkaline conditions necessary for the maintenance of zero net charge. However, in the AEM-MEC, 5.4 g/L of CO2 was eliminated when crossing the membrane (due to molecular diffusion and ionic transport). In contrast, the PEM-MEC eliminated 3.2 g/L of CO2 through the osmotic overflow that was split from the cathodic liquid phase. In addition, the PEM-MEC showed a greater efficiency of elimination from the influent COD (78 ± 7%) and methane production rate (83 ± 24 meq/L d) than AEM-MEC. At the same time, however, there was a higher energy demand per unit of CO2 eliminated at 2.36 vs. 0.78 vs. kWh/Nm3 CO2 removed. It is noteworthy that the AEM-MEC energy demand was lower than the large-scale processes for biogas updating, such as water-washing processes [140].

Considered an environmentally friendly approach, the microbial electrochemical method combines several beneficial processes, such as the consumption of CO2 for biogas upgrading, the generation of valuable liquid and gas by-products that can serve as process supplements or co-products, and the removal of influent COD at the anode. Additionally, it provides the potential to convert renewable electricity into gaseous biofuels. These advantages make the method a promising sustainable approach. Nonetheless, most of the current research has been focused on laboratory-scale experiments, and the technical and economic challenges associated with scaling these processes for large-scale biogas upgrading are still being investigated. Zhou et al. use electromethanogensis of anaerobic granular sludge (AGS) to upgrade biogas and store energy. This study uses AGS as a biocathode, which found a methane content as high as 97.9 ± 2.3% with an energy benefit of 477.3 kJ/mol and about 500 USD/m3 economic benefit [141]. Some of these limitations include scale-up to industrially relevant voltages and currents, development of low-cost membranes, and microbe population stability [142].

4. Conclusions

This paper explores the advancements in RNG technologies that are driving the sector forward, offering a promising solution for sustainable energy production. By utilizing the potential of organic waste materials and applying innovative processes, RNG has the potential to significantly contribute to a greener circular economy by offering a more ecological solution to a growing energy crisis. This research, from papers Part I and Part II, provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of RNG technologies and explores the future potential of these technologies to enhance further the production, purification, and utilization of RNG. The technologies discussed in this review—cryogenic separation, methane enrichment in situ, and hybrid systems—are at the forefront of optimizing RNG yield and efficiency. Cryogenic separation offers high purity outputs and energy efficiency, while methane enrichment in situ leverages natural processes to enhance gas quality directly at the source. Hybrid technologies, combining the strengths of various methods, provide versatile and adaptable solutions for diverse operations.

Moreover, developing technologies such as the industrial lung, supersonic separation, chemical hydrogenation, hydrate formation, and an array of biological processes promise to revolutionize RNG production further. The industrial lung and supersonic separation techniques aim to maximize gas recovery with minimal environmental impact, while chemical hydrogenation and hydrate formation present novel avenues for capturing and utilizing methane. Biological technologies continue to evolve, offering eco-friendly and scalable options for RNG production. Continued research and development in these areas are crucial for overcoming current limitations and unlocking the full potential of RNG. Depending on the technology and its integration as a sole or hybrid technology gives a wide range in technical readiness of each process. Many are in the range of 3–8 in utilization for RNG upgrading (TRL7: supersonic separation), but some of the technologies (TRL9: supersonic separation) are completely technically ready since they are mature technologies. Some technologies when utilized in hybrid processes (TRL6: cryogenic separation with PSA) are different than the stand-alone readiness (TRL9: cryogenic separation, TRL9: PSA). It is important continue integrating these innovative technologies, the RNG industry can significantly contribute to lowering greenhouse gas emissions, enhancing energy security, and encouraging a circular economy. Future studies should focus on optimizing these processes, assessing their economic viability (i.e., techno-economic analyses (TEAs)), and understanding their long-term environmental impacts (i.e., life cycle analyses (LCAs), risk assessments, etc.) to increase the technical readiness of these operations in relation to RNG upgrading further. In all, the synergy between technological innovation and policy support will be pivotal in achieving a sustainable and resilient energy future.

Funding

Funding was provided by the Energy Institute of Louisiana, University of Louisiana.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hagos, K.; Zong, J.; Li, D.; Liu, C.; Lu, X. Anaerobic co-digestion process for biogas production: Progress, challenges and perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 76, 1485–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirkler, D.; Peters, A.; Kaupenjohann, M. Elemental composition of biogas residues: Variability and alteration during anaerobic digestion. Biomass Bioenergy 2014, 67, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, B.; Foret, B.; Sharp, W.; Gang, D.; Hernandez, R.; Revellame, E.; Fortela, D.L.B.; Holmes, W.E.; Zappi, M.E. An Overview of the Potential for Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants to Be Integrated into Urban Biorefineries for the Production of Sustainable Bio-Based Fuels and Other Chemicals. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2024, 10, 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A.; Dominguez-Faus, R.; Parker, N.; Scheitrum, D.; Wilcock, J.; Miller, M. The Feasibility of Renewable Natural Gas as a Large-Scale, Low Carbon Substitute. 2016. Available online: https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/classic/research/apr/past/13-307.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- Gaida, D.; Wolf, C.; Bongards, M. Feed control of anaerobic digestion processes for renewable energy production: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.; Gadhamshetty, V.; Nitayavardhana, S.; Khanal, S.K. Automatic process control in anaerobic digestion technology: A critical review. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 193, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasapoor, M.; Young, B.; Brar, R.; Sarmah, A.; Zhuang, W.Q.; Baroutian, S. Recognizing the challenges of anaerobic digestion: Critical steps toward improving biogas generation. Fuel 2020, 261, 116497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunatsa, T.; Xia, X. A review on anaerobic digestion with focus on the role of biomass co-digestion, modelling and optimisation on biogas production and enhancement. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortela, D.L.B.; Sharp, W.W.; Revellame, E.D.; Hernandez, R.; Gang, D.; Zappi, M.E. Computational evaluation for effects of feedstock variations on the sensitivities of biochemical mechanism parameters in anaerobic digestion kinetic models. Biochem. Eng. J. 2019, 143, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, K.; Mullick, A.; Ali, A.; Kargupta, K.; Ganguly, S. Cryogenic carbon dioxide separation from natural gas: A review based on conventional and novel emerging technologies. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2014, 30, 453–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufford, T.E.; Smart, S.; Watson, G.C.Y.; Graham, B.F.; Boxall, J.; Diniz da Costa, J.C.; May, E.F. The removal of CO2 and N2 from natural gas: A review of conventional and emerging process technologies. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2012, 94-95, 123–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S.; Lamb, J.J.; Hjelme, D.R.; Lien, K.M. Overview of recent progress towards in-situ biogas upgradation techniques. Fuel 2018, 226, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotagodahett, R.; Hewage, K.; Sadiq, R. Decarbonized Natural Gas Supply Chain with Low-Carbon Gaseous Fuels: A Life Cycle Environmental and Economic Assessment. Lect. Notes Civ. Eng. 2024, 367, 999–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yentekakis, I.V.; Goula, G. Biogas management: Advanced utilization for production of renewable energy and added-value chemicals. Front. Environ. Sci. 2017, 5, 237755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyrs, T.; Feldmann, J.; Gasper, R. Renewable Natural Gas as a Climate Strategy: Guidance for State Policymakers. World Resources Institute. 2020. Available online: https://www.wri.org/research/renewable-natural-gas-climate-strategy-guidance-state-policymakers (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- SkyQuest. Renewable Natural Gas Market Size & Share—Industry Growth | 2031. 2024. Available online: https://www.skyquestt.com/report/renewable-natural-gas-market (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Faransso, R. Jumpstarting the Clean Hydrogen Economy—The Final Rule for 45v. Available online: https://esgreview.net/2025/01/15/jumpstarting-the-clean-hydrogen-economy-the-final-rule-for-45v (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- USDOE; North Wind Inc. 2022 Annual Site Environmental Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2024-06/2022%20Site%20Environmental%20Report%2C%20Department%20of%20Energy%2C%20ETEC%20-%20Area%20IV%20Santa%20Susana%20Field%20Laboratory%2C%20October%202023.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Service, I.R. Credit for Production of Clean Hydrogen and Energy Credit. 2023. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/12/26/2023-28359/section-45v-credit-for-production-of-clean-hydrogen-section-48a15-election-to-treat-clean-hydrogen (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Lewis, E.; McNaul, S.; Jamieson, M.; Henriksen, M.S.; Matthews, H.S.; Walsh, L.; Grove, J.; Shultz, T.; Skone, T.J.; Stevens, R. Comparison of Commercial, State-of-the-Art, Fossil-Based Hydrogen Production Technologies; National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL): Pittsburgh, PA, USA; Morgantown, WV, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete, A. Final regulations for the Inflation Reduction Act’s Section 45V Clean Hydrogen Production Tax Credit. POLICY. 2025. Available online: https://theicct.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/ID-337-%E2%80%93-Hydrogen-credit_policy-update_final.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Sahota, S.; Shah, G.; Ghosh, P.; Kapoor, R.; Sengupta, S.; Singh, P.; Vijay, V.; Sahay, A.; Vijay, V.K.; Thakur, I.S. Review of trends in biogas upgradation technologies and future perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2018, 1, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidaki, I.; Treu, L.; Tsapekos, P.; Luo, G.; Campanaro, S.; Wenzel, H.; Kougias, P. Biogas upgrading and utilization: Current status and perspectives. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awe, O.W.; Zhao, Y.; Nzihou, A.; Minh, D.P.; Lyczko, N. A Review of Biogas Utilisation, Purification and Upgrading Technologies. Waste Biomass Valorization 2017, 8, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, F.; Hulteberg, C.; Persson, T.; Tamm, D. Biogas Upgrading—Review of Commercial Technologies (Biogasuppgradering-Granskning av Kommersiella Tekniker) SGC Rapport 2013:270 “Catalyzing Energygas Development for Sustainable Solutions”. Available online: https://portal.research.lu.se/sv/publications/biogas-upgrading-technology-overview-comparison-and-perspectives-/ (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Grande, C.A.; Blom, R. Cryogenic Adsorption of Methane and Carbon Dioxide on Zeolites 4A and 13X. Energy Fuels 2014, 28, 6688–6693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltner, M.; Makaruk, A.; Harasek, M. Review on available biogas upgrading technologies and innovations towards advanced solutions. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 1329–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, R.; Meier, L.; Diaz, I.; Jeison, D. A review on the state-of-the-art of physical/chemical and biological technologies for biogas upgrading. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2015, 14, 727–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryckebosch, E.; Drouillon, M.; Vervaeren, H. Techniques for transformation of biogas to biomethane. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 1633–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah Khan, I.; Hafiz Dzarfan Othman, M.; Hashim, H.; Matsuura, T.; Ismail, A.F.; Rezaei-DashtArzhandi, M.; Wan Azelee, I. Biogas as a renewable energy fuel—A review of biogas upgrading, utilisation and storage. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 150, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.E.; Wahid, M.A. Biogas utilization: Experimental investigation on biogas flameless combustion in lab-scale furnace. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 74, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegue, L.B.; Hinge, J. Biogas and bio-syngas upgrading. Dan. Technol. Inst. 2012, 5, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Li, H.; Yan, J.; Liu, L.; Yu, Z.; Yu, X. Selection of appropriate biogas upgrading technology-a review of biogas cleaning, upgrading and utilisation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 51, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, A.M.; El-Maghlany, W.M.; Eldrainy, Y.A.; Attia, A. New approach for biogas purification using cryogenic separation and distillation process for CO2 capture. Energy 2018, 156, 328–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, R.; Panwar, N.L. Recent advancement in biogas enrichment and its applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 73, 892–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersson, A.; Wellinger, A. Biogas Upgrading Technologies—Developments and Innovations. IEA Bioenergy Task 37-Energy from Biogas Landfill Gas. 2009. Available online: https://www.ieabioenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/10/upgrading_rz_low_final.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Hansson, M.; Yu, Z.; Nordberg, Å.; Rasmuson, Å. In-Situ Methane Enrichment in Anaerobic Digestion of Sewage Sludge—Stage 2. 2009. Available online: http://sgc.camero.se/ckfinder/userfiles/files/SGC280.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Boontawee, S.; Koonaphapdeelert, S. In-Situ Biomethane Enrichment by Recirculation of Biogas Channel Digester Effluent Using Gas Stripping Column. Energy Procedia 2016, 89, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Belaissaoui, B.; Willson, D.; Favre, E. Membrane gas separations and post-combustion carbon dioxide capture: Parametric sensitivity and process integration strategies. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 211–212, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, B.; Hao, P.; Baker, R.; Kniep, J.; Chen, E.; Ding, J.; Zhang, Y.; Rochelle, G.T. Hybrid Membrane-absorption CO2 Capture Process. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Liu, Q.; Ji, N.; Deng, S.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Kitamura, Y. Reducing the energy consumption of membrane-cryogenic hybrid CO2 capture by process optimization. Energy 2017, 124, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surovtseva, D.; Amin, R.; Barifcani, A. Design and operation of pilot plant for CO2 capture from IGCC flue gases by combined cryogenic and hydrate method. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2011, 89, 1752–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzianowski, W.M. A review of potential innovations for production, conditioning and utilization of biogas with multiple-criteria assessment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 1148–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, M.; Melin, T.; Wessling, M. Transforming biogas into biomethane using membrane technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 17, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struk, M.; Kushkevych, I.; Vítězová, M. Biogas upgrading methods: Recent advancements and emerging technologies. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2020, 19, 651–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentair. Haffmans Biomethane & Green CO2 Biogas Upgrading Using Membrane & Cryogenic Technology. 2016. Available online: https://task37.ieabioenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/32/2022/03/5T37Holland170406denHeijer.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Soni Castro, P.; Martinez Zuniga, G.; Holmes, W.; Buchireddy, P.R.; Gang, D.D.; Revellame, E.; Zappi, M.; Hernandez, R. Review of the adsorbents/catalysts for the removal of sulfur compounds from natural gas. Gas Sci. Eng. 2023, 115, 205004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa, J.A.; Laines, J.R.; García, D.S.; Hernández, R.; Zappi, M.; Espinosa de los Monteros, A.E. Activated Carbon: A Review of Residual Precursors, Synthesis Processes, Characterization Techniques, and Applications in the Improvement of Biogas. Environ. Eng. Res. 2023, 28, 220100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andlar, M.; Belskaya, H.; Morzak, G.; Ivančić Šantek, M.; Rezić, T.; Petravić Tominac, V.; Šantek, B. Biogas Production Systems and Upgrading Technologies: A Review. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2021, 59, 387–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, C.; Dutil, F. Carbonic Anhydrase Bioreactor and Process. U.S. Patent 8329460B2, 11 December 2012. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US8329460B2/en (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Bian, J.; Cao, X.; Yang, W.; Song, X.; Xiang, C.; Gao, S. Condensation characteristics of natural gas in the supersonic liquefaction process. Energy 2019, 168, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, M.D.; Williams, R.B.; Kaffka, S.R. Comparative Assessment of Technology Options for Biogas Clean-Up. 2014. Available online: https://ucdavis.app.box.com/s/iaog2diybkvoe5xxdjud97xsrx3ypwmq (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Altam, R.A.; Lemma, T.A.; Jufar, S.R. Trends in Supersonic Separator design development. MATEC Web Conf. 2017, 131, 03006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jürgensen, L.; Ehimen, E.A.; Born, J.; Holm-Nielsen, J.B. Dynamic biogas upgrading based on the Sabatier process: Thermodynamic and dynamic process simulation. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 178, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, A.; Cheng, J.; Murphy, J.D. Innovation in biological production and upgrading of methane and hydrogen for use as gaseous transport biofuel. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 451–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Betta, R.A.; Piken, A.G.; Shelef, M. Heterogeneous methanation: Steady-state rate of CO hydrogenation on supported ruthenium, nickel and rhenium. J. Catal. 1975, 40, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürgensen, L.; Ehimen, E.; Born, J.; Holm-Nielsen, J.; Rooney, D. Influence of trace substances on methanation catalysts used in dynamic biogas upgrading. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 178, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witte, J.; Settino, J.; Biollaz, S.M.A.; Schildhauer, T.J. Direct catalytic methanation of biogas—Part I: New insights into biomethane production using rate-based modelling and detailed process analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 171, 750–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.-H.; Lee, H. Clathrate phase equilibria for the water–phenol–carbon dioxide system. AIChE J. 1997, 43, 1884–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.-P.; Seo, Y.; Jang, W.; Seo, Y. Gas Hydrate Process for Recovery of CO2 from Fuel Gas. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2009, 17, 1449–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, H.; Yamasaki, A.; Kiyono, F. Energy consumption estimation for greenhouse gas separation processes by clathrate hydrate formation. Energy 2004, 29, 1713–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, G.; Yang, L.; Zhang, L. Study on the recovery of hydrogen from refinery (hydrogen + methane) gas mixtures using hydrate technology. Sci. China Ser. B Chem. 2008, 51, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M.; Heijne, A.; Buisman, C.; Hamelers, H.V.M. Microbial electrolysis cells for production of methane from CO2: Long-term performance and perspectives: A methane-producing MEC to increase land use efficiency. Int. J. Energy Res. 2012, 36, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horii, S.; Ohmura, R. Continuous separation of CO2 from a H2 + CO2 gas mixture using clathrate hydrate. Appl. Energy 2018, 225, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kougias, P.; Campanaro, S.; Treu, L.; Zhu, X.; Angelidaki, I. A novel archaeal species belonging to Methanoculleus genus identified via de-novo assembly and metagenomic binning process in biogas reactors. Anaerobe 2017, 46, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Johansson, S.; Boe, K.; Xie, L.; Zhou, Q.; Angelidaki, I. Simultaneous hydrogen utilization and in situ biogas upgrading in an anaerobic reactor. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2012, 109, 1088–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, G.; Angelidaki, I. Co-digestion of manure and whey for in situ biogas upgrading by the addition of H2: Process performance and microbial insights. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, G.; Angelidaki, I. Hollow fiber membrane based H2 diffusion for efficient in situ biogas upgrading in an anaerobic reactor. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 3739–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassani, I.; Kougias, P.G.; Angelidaki, I. In-Situ biogas upgrading in thermophilic granular UASB reactor: Key factors affecting the hydrogen mass transfer rate. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 221, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulat, D.G.; Mosbæk, F.; Ward, A.J.; Polag, D.; Greule, M.; Keppler, F.; Nielsen, J.L.; Feilberg, A. Exogenous addition of H2 for an in situ biogas upgrading through biological reduction of carbon dioxide into methane. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agneessens, L.M.; Ottosen, L.D.M.; Voigt, N.V.; Nielsen, J.L.; de Jonge, N.; Fischer, C.H.; Kofoed, M.V.W. In-Situ biogas upgrading with pulse H2 additions: The relevance of methanogen adaption and inorganic carbon level. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 233, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batstone, D.; Keller, J.; Angelidaki, I.; Kalyuzhnyi, S.; Pavlostathis, S.; Rozzi, A.; Sanders, W.; Siegrist, H.; Vavilin, V. Anaerobic digestion model No 1 (ADM1). Water Sci. Technol. J. Int. Assoc. Water Pollut. Res. 2002, 45, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, M.C.; Braghieri, A.; Capece, A.; Napolitano, F.; Romano, P.; Galgano, F.; Altieri, G.; Genovese, F. Recent Updates on the Use of Agro-Food Waste for Biogas Production. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Whitman, W.B. Metabolic, Phylogenetic, and Ecological Diversity of the Methanogenic Archaea. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1125, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.N.; Morgan, R.M.; Nölling, J. Environmental and molecular regulation of methanogenesis. Water Sci. Technol. 1997, 36, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tirunehe, G.; Norddahl, B. The influence of polymeric membrane gas spargers on hydrodynamics and mass transfer in bubble column bioreactors. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 39, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, G.; Wang, W.; Angelidaki, I. A new degassing membrane coupled upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB) reactor to achieve in-situ biogas upgrading and recovery of dissolved CH4 from the anaerobic effluent. Appl. Energy 2014, 132, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alitalo, A.; Niskanen, M.; Aura, E. Biocatalytic methanation of hydrogen and carbon dioxide in a fixed bed bioreactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 196, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassani, I.; Kougias, P.G.; Treu, L.; Angelidaki, I. Biogas Upgrading via Hydrogenotrophic Methanogenesis in Two-Stage Continuous Stirred Tank Reactors at Mesophilic and Thermophilic Conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 12585–12593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassani, I.; Kougias, P.G.; Treu, L.; Porté, H.; Campanaro, S.; Angelidaki, I. Optimization of hydrogen dispersion in thermophilic up-flow reactors for ex situ biogas upgrading. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 234, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, M.; Koschack, T.; Busch, G. Biocatalytic methanation of hydrogen and carbon dioxide in an anaerobic three-phase system. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 178, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, M.; Busch, G. Methanation of hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Appl. Energy 2013, 111, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guneratnam, A.J.; Ahern, E.; FitzGerald, J.A.; Jackson, S.A.; Xia, A.; Dobson, A.D.W.; Murphy, J.D. Study of the performance of a thermophilic biological methanation system. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 225, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Choi, K.; Chung, J. Reduction in carbon dioxide and production of methane by biological reaction in the electronics industry. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 3488–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Chang, W.; Pak, D. Biological conversion of CO2 to CH4 using hydrogenotrophic methanogen in a fixed bed reactor. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2012, 87, 844–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Angelidaki, I. Integrated biogas upgrading and hydrogen utilization in an anaerobic reactor containing enriched hydrogenotrophic methanogenic culture. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2012, 109, 2729–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M.R.; Fornero, J.J.; Stark, R.; Mets, L.; Angenent, L.T. A single-culture bioprocess of Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus to upgrade digester biogas by CO2-to-CH4 conversion with H2. Archaea 2013, 2013, 157529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachbauer, L.; Voitl, G.; Bochmann, G.; Fuchs, W. Biological biogas upgrading capacity of a hydrogenotrophic community in a trickle-bed reactor. Appl. Energy 2016, 180, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stams, A.J.M.; Plugge, C.M. Electron transfer in syntrophic communities of anaerobic bacteria and archaea. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuchmann, K.; Müller, V. Autotrophy at the thermodynamic limit of life: A model for energy conservation in acetogenic bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, B.; Scherer, P. The roles of acetotrophic and hydrogenotrophic methanogens during anaerobic conversion of biomass to methane: A review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2008, 7, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kougias, P.G.; Treu, L.; Benavente, D.P.; Boe, K.; Campanaro, S.; Angelidaki, I. Ex-Situ biogas upgrading and enhancement in different reactor systems. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 225, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, I.; Pérez, C.; Alfaro, N.; Fdz-Polanco, F. A feasibility study on the bioconversion of CO2 and H2 to biomethane by gas sparging through polymeric membranes. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 185, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremges, A.; Maus, I.; Belmann, P.; Eikmeyer, F.; Winkler, A.; Albersmeier, A.; Pühler, A.; Schlüter, A.; Sczyrba, A. Deeply sequenced metagenome and metatranscriptome of a biogas-producing microbial community from an agricultural production-scale biogas plant. GigaScience 2015, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treu, L.; Campanaro, S.; Kougias, P.G.; Zhu, X.; Angelidaki, I. Untangling the Effect of Fatty Acid Addition at Species Level Revealed Different Transcriptional Responses of the Biogas Microbial Community Members. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 6079–6090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco-Morgado, M.; Alcántara, C.; Noyola, A.; Muñoz, R.; González-Sánchez, A. A study of photosynthetic biogas upgrading based on a high rate algal pond under alkaline conditions: Influence of the illumination regime. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 592, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, L.; Pérez, R.; Azócar, L.; Rivas, M.; Jeison, D. Photosynthetic CO2 uptake by microalgae: An attractive tool for biogas upgrading. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 73, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, L.; Barros, P.; Torres, A.; Vilchez, C.; Jeison, D. Photosynthetic biogas upgrading using microalgae: Effect of light/dark photoperiod. Renew. Energy 2017, 106, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadas, E.; Serejo, M.L.; Blanco, S.; Pérez, R.; García-Encina, P.A.; Muñoz, R. Minimization of biomethane oxygen concentration during biogas upgrading in algal–bacterial photobioreactors. Algal Res. 2015, 12, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadas, E.; Marín, D.; Blanco, S.; Lebrero, R.; Muñoz, R. Simultaneous biogas upgrading and centrate treatment in an outdoors pilot scale high rate algal pond. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 232, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prandini, J.M.; da Silva, M.L.B.; Mezzari, M.P.; Pirolli, M.; Michelon, W.; Soares, H.M. Enhancement of nutrient removal from swine wastewater digestate coupled to biogas purification by microalgae Scenedesmus spp. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 202, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serejo, M.L.; Posadas, E.; Boncz, M.A.; Blanco, S.; García-Encina, P.; Muñoz, R. Influence of Biogas Flow Rate on Biomass Composition During the Optimization of Biogas Upgrading in Microalgal-Bacterial Processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 3228–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Cervantes, A.; Serejo, M.L.; Blanco, S.; Pérez, R.; Lebrero, R.; Muñoz, R. Photosynthetic biogas upgrading to bio-methane: Boosting nutrient recovery via biomass productivity control. Algal Res. 2016, 17, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Cervantes, A.; Madrid-Chirinos, C.; Cantera, S.; Lebrero, R.; Muñoz, R. Influence of the gas-liquid flow configuration in the absorption column on photosynthetic biogas upgrading in algal-bacterial photobioreactors. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 225, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, S.; Hu, C.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J.; Ping, L. Performance of three microalgal strains in biogas slurry purification and biogas upgrade in response to various mixed light-emitting diode light wavelengths. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 187, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, R.; Guieysse, B. Algal–bacterial processes for the treatment of hazardous contaminants: A review. Water Res. 2006, 40, 2799–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Muñoz, R.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y. The effects of various LED (light emitting diode) lighting strategies on simultaneous biogas upgrading and biogas slurry nutrient reduction by using of microalgae Chlorella sp. Energy 2016, 106, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, A.C.; Amaro, H.M.; Malcata, F.X. Microalgae as sources of high added-value compounds-a brief review of recent work. Biotechnol. Prog. 2011, 27, 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]