Abstract

The study presents a scalable decision-support framework to assess energy-sharing strategies within mixed-use urban districts, with a focus on planning, sustainability, and policy relevance. Two renewable energy-sharing mechanisms—energy sharing (ES) and net metering (NM)—are compared through a techno-economic analysis applied to a real neighborhood in Montréal, Canada. The workflow integrates irradiance-aware PV simulation, archetype-based urban building modeling, and financial sensitivity analysis adaptable to local regulatory conditions. Key performance indicators (KPIs)—including Self-Consumption Ratio (SCR), Self-Sufficiency Ratio (SSR), and peak load reduction—are used to evaluate technical performance. Results show that ES outperforms NM, achieving higher SCR (77% vs. 66%) and SSR (40% vs. 35%), and seasonal analysis reveals that peak shaving reaches 30.3% during summer afternoons, while PV impact is limited to 15.6% in winter mornings and negligible during winter evenings. Although both mechanisms are currently unprofitable under existing Québec tariffs, scenario analysis reveals that a 50% CAPEX subsidy or a 0.12 CAD/kWh feed-in tariff could make the system viable. The novelty of this study lies in the development of a replicable, archetype-driven, and policy-oriented simulation framework that enables the evaluation of renewable energy communities in mixed-use and data-scarce urban environments, contributing new insights into the Canadian energy transition context.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The rapid expansion of renewable energy generation shifts the energy system from a purely centralized top-down to a more distributed structure, which includes prosumers and energy communities (ECs). In the European Union, the Directive n.2001/2018 derived from the Clean Energy Package defined renewable energy communities (RECs) [1]. Renewable energy communities (RECs) are local energy systems formed through the voluntary involvement of citizens, organizations, or businesses to produce, use, store, share, and sell renewable electricity under agreed rules. Their main aim is to create environmental, social, and economic value at the community level, rather than focusing only on financial profit, as part of the broader energy transition. According to EU directives, REC members must be located near the renewable installations owned by the community. To support this model, tailored incentives are needed to encourage local energy sharing. Each Member State has adapted these rules by defining criteria such as the geographical limits for participation, the minimum renewable contribution, and the tariffs applied to shared energy [2]. The interplay of technologies, stakeholders, institutions, market mechanisms for energy exchange, and environmental benefits necessitates tools that can effectively model energy demand and generation at the community level [3]. Such tools must integrate multiple building uses, and incorporate energy-sharing mechanisms in the evaluations, both among community members and with the grid [4].

Evolving overviews of the different implementations of energy-sharing regulation have been investigated in the EU [5,6] for prosumer and collective configurations. Their findings show the differences, both in terms of magnitude and implementation, of the attractiveness and support provided to energy communities. The recent evolution in the EU frameworks encouraged self-consumption for prosumers rather than the sale of energy surplus to the grid [7], while collective self-consumption laws are still underway [8]. Despite experiences of Community Energy Planning [9], the concept of renewable energy communities is not yet regulated in Canada [10]. The 2018 Energy Vision for Canada [11] envisages that by 2030 most Canadians will have the option to become prosumers, through residential and commercial solar generation, district heating, and distributed storage. However, Canadian provinces are only slowly introducing new forms of energy tariffs to renewable generation sale [12]. Parallelly, legal frameworks for aggregated or community-level energy projects are limited with few applications. In some provinces of Canada, such as Quebec and Ontario, electricity prosumers are covered by a net metering, which refers to a billing mechanism that enables electricity consumers to generate their own power using renewable sources while connected to the grid [13]. For those utilizing renewable sources, the Net Metering Option I consists of exchanging surplus electricity for credit on their utility account, which is deducted from future bills. Conversely, when production falls short, the grid supplies the necessary power, ensuring consistent service quality. However, the credits under this scheme are non-transferable and non-monetary, expiring after a set duration [14], which implies limits in their usage.

1.2. Literature Review

Operational optimization and energy sharing within ECs can enhance the value of renewable energy production, improve social welfare, and facilitate efficient use of energy resources [15]. A broad review confirms multi-dimensional EC impacts (economic, environmental, technical, social) [16]; within this, aggregated/virtual sharing consistently improves self-consumption (SCR) and self-sufficiency (SSR) and can enhance profitability relative to purely individual prosumer schemes [17,18,19].

For mixed-use districts—where residential, commercial, educational, and public loads interact—recent studies show that daytime non-residential demand aligns with PV production, raising summer SCR/SSR and smoothing peaks [20,21].

For example, Manso-Burgos et al. [17] analyzed the optimal configuration for a local EC with PV and a battery energy storage system (BESS). They considered both residential and commercial functions with real consumption data for a 100 kWp PV installation in Valencia, Spain. The approach is based on a trial-and-error method until the best solution for size, residential share, and technological composition is found, using different allocation strategies among users. The objective is to maximize bill savings, then considering the degree of self-consumption and GHG reduction. However, the simulation of 144 scenarios has been time consuming and is not applicable to automated evaluations. A range of EC configurations was also analyzed by Mehta and Tiefenbeck [18]. As in the previous case, this study used real-world demand data from 3.594 households in the UK, but considering only residential users. The configuration is characterized by the size of the community, the ratio of household prosumers, and installed PV size. As the prosumer share increases, individual profitability reduces, self-sufficiency rises, and overloads are more frequent. Franzoi et al. [22] simulated PV systems and heat pumps for different residential buildings in heat-dominated climates. In this case, the simulation studies were performed in TRNSYS 2018 with a one-minute time-step and the data analysis was carried out in MATLAB 2024b. Acting on larger condominiums or energy communities at the neighborhood level can maximize self-consumption. The simulation by Weckesser et al. [23] investigated the sizing of PV and communal batteries for city, suburban, and rural distribution grids. The analysis applied a linear programming optimization, testing four strategies: maximizing the community economic benefit, minimizing peak power exchange, and increasing self-sufficiency with the battery energy storage system (BESS) positioned either behind or in front of the meter. Altogether, 180 scenarios were evaluated. Laurini et al. [24] used a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) optimization model to determine the optimal design of a renewable energy community (REC) in a small Italian municipality, comparing scenarios that minimize annualized costs with those that maximize energy sharing. The model assessed individual versus collective configurations of buildings in terms of member selection and technology deployment. The results show that configurations with fewer, high-consumption users (such as municipal or industrial buildings) maximize PV installations and economic returns, especially when selling surplus electricity. In contrast, maximizing shared energy requires broader participation and the inclusion of additional technologies like batteries and wind turbines. The sensitivity analysis highlights that the inclusion of large consumers improves the effectiveness of energy sharing and increases profitability, as these users not only stabilize load diversity but also provide greater surface area for PV deployment

Importantly, scenarios with intra-community sharing are often more profitable than individual optimization [19], and virtual net-metering studies confirm distributional/ownership implications at scale [6].

While techno-economic metrics (SCR, SSR, NPV) are widely reported, grid-related indicators (e.g., monthly/seasonal peak shaving, valley filling, import reduction) remain less explored and are sensitive to use-mix and metering rules [25].

Measured data are more often available for the residential sector rather than on other types of users or building function. This is a limit considering the improvement of energy performance integrating different building types [26]. Although studies utilizing metered data exist, the use of real consumption data in energy modeling is still rare, posing a significant challenge for simulating community energy scenarios [27]. To face data limitations, Kazmi et al. [28] provided a detailed overview of open-source datasets, models, and tools which can be used for designing and operating real-world ECs. The review showed that demand data for large building datasets are often limited in space and time, while open-source tools are available but generally require user proficiency.

In contrast to complex and often incomplete tools, a spatially based and streamlined approach can be advantageous, particularly for modeling large numbers of buildings and employing archetype-based analyses. Vecchi et al. [4] conducted a review of software for modeling ECs in urban areas, emphasizing the need for comprehensive, spatially integrated tools and capable of managing multiple building functions and user types. Examples for such software tools are URBANopt [29] and City Energy Analysts [30]. The reviewed studies primarily relied on optimization-based and technically focused tools rather than on a comprehensive evaluation framework.

Moreover, most available software lacks integrated capabilities for energy sharing [4], necessitating external optimization processes. Energy-sharing mechanisms, particularly in the context of energy regulations, have been analyzed in recent studies [19]. However, the impacts of virtual energy-sharing mechanisms still require further assessment through simulations at both the individual building and community levels.

Beyond the distribution-level focus adopted here, related strands at larger system boundaries are emerging and point to future extensions: coordinated operation of multi-energy microgrids with green hydrogen and safe policy learning for congestion management [31]; transmission-level protection of bipolar LCC-HVDC lines [32]; and N-1 reliability of integrated electricity–gas systems with cyber-physical interdependence [33].

1.3. Regulatory Context

Energy trading within ECs enhances grid efficiency and independence, particularly in the context of the increasing emphasis on renewable energy integration [34]. Despite its inclusion in European regulations, a key challenge remains how to share and regulate self-produced energy among EC members. Two primary energy-sharing schemes discussed in the literature are peer-to-peer (P2P) trading and virtual metering (VM) [35]. P2P implies the trade of self-produced energy among different points of delivery (POD) (or with the wholesale market), which can use energy trading platforms [36]. P2P trading is not widely diffused due to the immature status and regulative gaps [37]. The shared quantity and its price are identified autonomously. Peer-to-peer energy-sharing frameworks have been developed to reduce energy costs and promote renewable energy utilization among prosumers [38].

On the other hand, virtual metering (VM) considers the net energy flow among different users, each one with a POD [39]. Here a unique POD is considered for an EC, although members are physically connected to different PODs. VM is often referred to as virtual net metering, especially where self-consumption is regulated through net-energy policies [35].

At the same time, energy self-consumption for energy communities can be applied as physical or virtual [40]. Physical self-consumption establishes a direct connection between a PV plant and the customer, which instantly consumes the generated energy, relying on a single metering point or POD. In contrast, virtual self-consumption utilizes the public network, enabling energy exchanges between generation plants and different consumers. The benefits of virtual self-consumption result from a commercial operation, carried out by agreements that quantify the self-consumption quotas for each participant. Sonnen energy community, which is based in Germany, is a good example of this kind [41].

In EC projects, electricity generation may exceed the total consumption of EC members. Various mechanisms exist for selling surplus electricity to the grid, often implemented at the level of individual users. In the European PROSEU report, Hall et al. [42] reviewed business models and incentives for individual and collective prosumers. Feed-in tariffs (FiTs) have been widely adopted, where prosumers are paid a fixed price for the energy higher than the wholesale market price. The excess energy injected into the grid is compensated at a predetermined tariff notified by the regulator [43]. FiTs can play a significant role in promoting distributed generation in the early stages due to the fixed rates. However, as renewable technologies have matured, many countries have transitioned away from FiTs in favor of policies aimed at enhancing prosumer participation, as in the UK, Germany, Denmark, and Spain [8]. Net metering (NM) functions as prosumers feed in their excess energy in the utility grid and withdraw it when needed, in the form of credits, ranging from one month to several years [42]. Consumers may use electricity at times that do not match when renewable energy is generated. Yet, net metering (NM) and feed-in tariffs (FiTs) fail to capture the actual market value of the electricity once it enters the grid. Net billing (NB), instead, compensates prosumers according to the current market price of the electricity they consume or feed into the grid. This system motivates prosumers to export renewable power when prices are high, and to focus on self-consumption or storage when prices are low [43,44].

According to the analysis by Botelho et al. [8], the regulatory timeline shows FiT in the past to boost the growth of renewables, to be then substituted by NM. The current global trend is to shift from NM to policies aimed at energy self-consumption, both at individual and collective level. The possible future direction of policies leans towards P2P markets, where prosumers and aggregators can directly negotiate economic conditions but in which several gaps still need to be addressed.

The regulatory framework governing renewable energy communities (RECs) varies significantly between Europe and Canada, reflecting contrasting stages of policy maturity and institutional support.

In the European Union, RECs are explicitly recognized and promoted within the Clean Energy Package, notably through Directive (EU) 2018/2001 [5] on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources (RED II) and Directive (EU) 2019/944 [5] on common rules for the internal electricity market. These directives establish RECs as legal entities with the right to produce, consume, store, and share renewable energy among their members. They also mandate Member States to ensure non-discriminatory grid access and enable collective self-consumption and peer-to-peer trading mechanisms [5]. As a result, several European countries—such as Italy, Spain, and Germany—have implemented incentive schemes including feed-in tariffs, net billing, and collective self-consumption frameworks that foster community participation and accelerate the decentralization of the energy system.

By contrast, Canada currently lacks a national legal definition or unified policy framework for renewable energy communities. Energy policy and electricity market design fall under provincial jurisdiction, leading to a fragmented regulatory landscape. Community-based renewable initiatives generally operate through existing mechanisms such as net metering, Community Generation Programs, or co-operative ownership models administered by provincial utilities (e.g., Hydro-Québec, IESO Ontario, SaskPower) [45]. These mechanisms primarily provide billing credits for exported electricity rather than facilitating collective self-consumption or internal energy sharing. Consequently, Canadian RECs remain informal and project-driven, often depending on local leadership or research partnerships rather than dedicated policy instruments [46].

This divergence underscores a key motivation for the present work. While the EU framework provides a mature environment for studying RECs, Canada represents an emerging and under-explored context, where the absence of formal regulation and low retail electricity tariffs pose unique techno-economic challenges. Examining the potential of RECs within such conditions can yield valuable insights for future policy development and national decarbonization strategies.

1.4. Research Gaps

Despite the increasing attention toward renewable energy communities (RECs), several important research gaps remain in the current literature:

- Limited focus on mixed-use communities: Most previous studies have concentrated on residential-only configurations [16,17,18,19,22], neglecting the diversity of energy profiles in urban districts that include commercial, educational, and public buildings. This limits the generalizability of existing results to realistic city environments.

- Lack of scalable and data-light modeling frameworks: Many approaches rely on measured demand data or manually parameterized building models, which are rarely available for entire neighborhoods [27,28,29]. Scalable archetype-based methods capable of representing heterogeneous building stocks remain underdeveloped.

- Insufficient integration of energy-sharing mechanisms in simulation tools: Although optimization models for community energy systems exist, most urban building energy modeling (UBEM) platforms lack built-in functions for simulating energy sharing (ES) or net metering (NM) mechanisms [4,19]. This hinders comparative assessments of technical and financial performance under different policy frameworks.

- Geographical and policy underrepresentation: The majority of REC studies are conducted within European contexts, where supportive regulations and incentive schemes already exist [5,6,7,8]. Conversely, Canada remains largely unexplored, particularly regarding the feasibility of collective PV-based communities under current provincial tariff structures.

These gaps motivate the present study, which introduces a replicable and scalable simulation framework that integrates PV generation, hourly building energy demand, and virtual energy-sharing mechanisms for mixed-use urban neighbourhoods. The proposed workflow aims to bridge the gap between detailed technical modeling and policy-oriented economic evaluation, offering a novel contribution to REC research and urban energy planning.

1.5. Aim and Contributions

In response to the research gaps identified above, this study aims to develop a replicable and scalable simulation framework for evaluating the technical and economic performance of renewable energy communities (RECs) in mixed-use urban districts. The framework integrates archetype-based building energy modeling, irradiance-aware photovoltaic (PV) simulation, and policy-oriented economic assessment under two distinct renewable energy mechanisms: net metering (NM) and energy sharing (ES).

The primary objectives of this work are to carry out the following:

- Quantify the impact of NM and ES mechanisms on key performance indicators such as Self-Consumption Ratio (SCR), Self-Sufficiency Ratio (SSR), and peak load reduction for a representative case study in Montréal, Canada.

- Assess the economic viability of community-scale PV deployment under current Québec electricity tariffs and explore policy scenarios (feed-in tariffs, CAPEX incentives) that could enhance feasibility.

- Demonstrate a replicable workflow that can be applied to other data-scarce or policy-immature contexts where full REC regulation has not yet been established.

The contributions of this study are threefold:

- Methodological contribution: The study introduces a data-light, archetype-based approach using the Tools4Cities platform, capable of representing large and heterogeneous building stocks without relying on detailed metered data. The workflow links PV generation modeling, hourly demand estimation, and post-processing for NM and ES evaluation within the same computational environment.

- Contextual and policy contribution: This is, to the authors’ knowledge, the first techno-economic comparison of NM and ES mechanisms applied to a mixed-use REC in Canada, addressing a gap in the existing literature dominated by European case studies. The findings provide actionable insights into how incentive structures could shape REC deployment under low-tariff conditions.

- Scientific contribution: The work delivers a validated simulation framework for evaluating REC operation in real urban contexts, offering transparent metrics and reproducible methods that can support both academic research and practical policy design.

Overall, the study bridges the gap between urban energy modeling and policy-oriented decision support, contributing a flexible tool for assessing the transition of Canadian cities toward distributed renewable energy systems.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employs a scalable modeling framework to evaluate the technical and economic performance of renewable energy communities (RECs) in urban contexts. The methodology integrates automated urban building energy modeling with irradiance-aware photovoltaic (PV) simulation and post-processing for energy-sharing analysis. The approach is designed to support city-scale assessments where high-resolution consumption data may be unavailable and manual input processes are infeasible. It consists of two key components:

- An automated urban building simulation workflow using the Tools4Cities platform;

- A custom Python-based model to assess hourly energy flows and calculate economic indicators under two energy policy mechanisms: net metering (NM) and energy sharing (ES).

The proposed modeling workflow is designed to be modular and reproducible, combining archetype-based building simulation, irradiance-aware PV modeling, and temporal redistribution logic for energy flows under different policy mechanisms. Unlike traditional tools that often rely on case-specific data or single-building analysis, this framework integrates high-resolution hourly simulations across multiple building types and urban functions. A key innovation lies in the dynamic comparison of net-metering and energy-sharing schemes, implemented through customized Python (version 5) scripts that allocate PV generation across buildings based on real-time surplus and demand matching. This allows for detailed assessment of KPIs like SCR, SSR, and grid-import reduction, even in the absence of measured data. The methodology is particularly suited to data-scarce urban environments where full empirical modeling is not feasible, enabling scalable evaluation of renewable energy communities for both technical and economic planning.

2.1. Tools4Cities: Building Modeling Workflow

The main challenges in urban building simulation are the data-related gaps, which include a lack of accurate data and inconsistency in data organization [45]. Also, most existing urban building energy modeling (UBEM) tools are parametrized manually, which is time consuming and could lead to wrong data input. Therefore, a standardized data structure is needed to organize the input data in the UBEM process and help automate it.

Tools4Cities is an open-source platform developed to streamline UBEM by integrating diverse datasets into a standardized, object-oriented framework. It enables automated generation of building simulation inputs for large districts by organizing urban geometry, usage types, and construction characteristics. In contrast to most UBEM tools that require extensive manual pre-processing or focus on single-use building types, Tools4Cities integrates geometry, archetype data, and irradiance-aware PV modeling within a single, reproducible workflow. The platform ability to export input files for both EnergyPlus and TRNSYS, and to interface directly with Python-based post-processing for energy-sharing and economic analysis, makes it particularly suitable for mixed-use renewable energy communities (RECs) such as the one analyzed in this work.

Specifically, Tools4Cities was chosen because it conducts the following:

- Automates archetype assignment using standardized datasets and metadata;

- Handles large, heterogeneous urban districts containing residential, commercial, and institutional buildings;

- Integrates Simplified Radiosity Algorithm (SRA)-based PV irradiance modeling;

- Provides direct coupling with post-processing algorithms for the energy system analysis;

- Requires minimal measured data, enabling simulation in data-scarce urban contexts.

To justify this choice, a comparison with three widely used UBEM tools—City Energy Analyst (CEA) [47], URBANopt [48], and TEASER [49]—is provided in Table 1. The comparison highlights key differences in data requirements, scalability, and ability to represent energy-sharing mechanisms.

Table 1.

Comparison of UBEM tools relevant to renewable energy communities analysis.

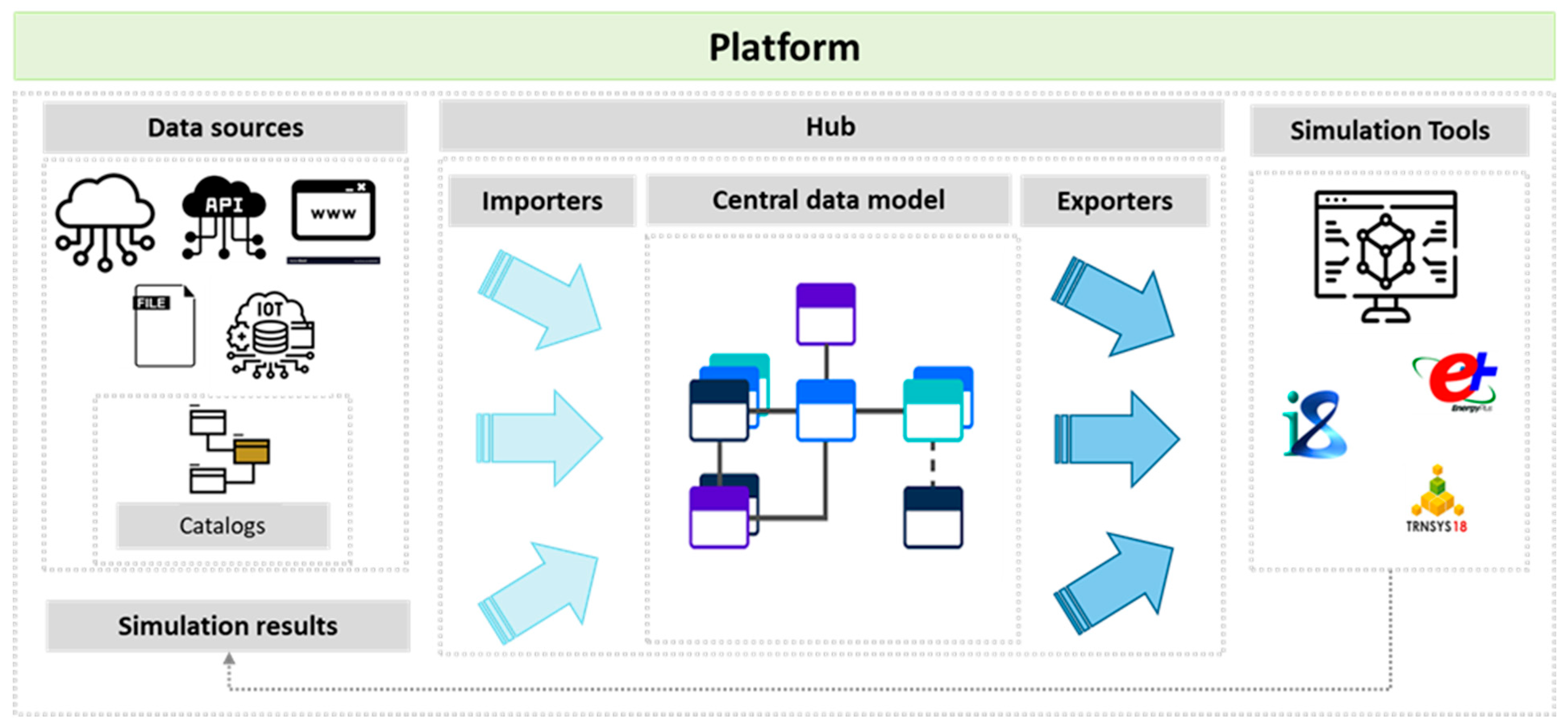

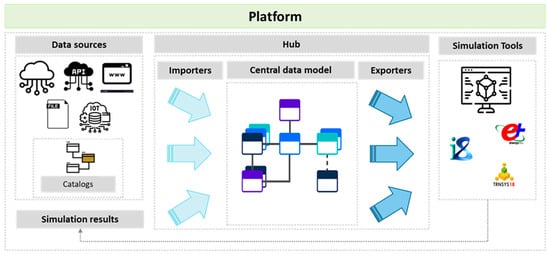

The general structure of the platform is shown in Figure 1. Given the diversity of data categories and sources, a central data model—supported by several domain-specific, object-oriented sub-models—is used to organize the necessary information for building energy modeling. The central data model is designed to represent a city, where the core class city includes attributes corresponding to various urban features. Buildings, roads, and green spaces are treated as CityObjects.

Figure 1.

Overview of the Tools4Cities platform architecture, illustrating the data flow from multiple sources through importers, a central object-oriented model, and exporters to simulation tools and front-end interfaces.

The UBEM process begins by creating a city instance from a geometry file, which must contain metadata such as building function and construction vintage. A geometry factory processes a range of input file formats, including .GeoJSON and .GML. Once the geometry is defined, a series of importers are employed to enrich the buildings with construction, usage, and energy system archetype data. These importers use a handler to select location-specific datasets and assign appropriate archetypes based on each building function and construction period.

A key feature of the platform is its ability to export input files compatible with various dynamic building simulation tools, such as EnergyPlus or TRNSYS. After enriching the city model with all required attributes, an exporter generates the appropriate input file and executes the external simulation engine to compute the building’s energy needs.

Further details on the archetype creation process and data structuring approach are beyond the scope of this paper. Interested readers are referred to [48,49] for more comprehensive information.

2.2. PV Modeling Workflow

The PV modeling workflow utilizes a Simplified Radiosity Algorithm (SRA) [50] to calculate the plane of array (POA) irradiance on all surfaces of each building. In this approach, the sky is divided into discrete patches of solid angle considering their radiance and angular relationship to the receiving surface. It accounts for direct solar radiation, anisotropic diffuse radiation, and reflected radiation by evaluating the proportion of each patch visible to the surface. The radiance of each patch is derived using a sky model, and the angle of incidence is calculated geometrically. Obstructions are considered by identifying the main blocking elements for each patch. View factors are computed using rendering techniques, enabling efficient irradiance calculation while maintaining accuracy.

The SRA requires a geometry and a weather file with hourly direct normal irradiance and diffuse horizontal irradiance to calculate the POA irradiance on each surface. The system is sized once the irradiance on PV panel surfaces is calculated. A simple sizing procedure is used in the workflow where, based on the building function, a fixed fraction of the roof is only considered for PV installations. In the available area, the distance between the PV panel arrays is calculated from the following equation:

d = h × (sin(β) × cos(ψ))/(tan(α))

In this equation, d is the inter-row space between the PV panel arrays, h is the height of the panel, β is the tilt angle, ψ is the solar azimuth angle at the solar noon of the winter solstice, and α is the solar altitude angle at the solar noon of the winter solstice. The tilt angle for the PV system was set at 38°, corresponding approximately to the site latitude (45° N) and derived from annual-optimum tilt angle correlations for northern-latitude cities [51]. This choice maximizes the annual plane-of-array irradiance while maintaining structural simplicity and minimizing snow accumulation, consistent with previous PV performance studies conducted in Canadian climates [45].

The inter-row distance (d) between PV arrays was calculated to prevent self-shading at the winter solstice according to Equation (1), consistent with the geometric approach described by Duffie and Beckman [51].

Other parameters—including the temperature coefficient of power (λ = 0.004 °C−1), nominal operating cell temperature, and inverter efficiency (ηinv = 0.96)—were obtained from manufacturer catalogues and standardized testing conditions defined by IEC 61853-1 [52].

The following equations are used to calculate the hourly output of the PV system [53]:

Tcellk = Toutk + (Gtotk/Gtot,nomk)(Tcell,nom − Tout,nom)

Ppvk = ηinv × ns × np × (Gtotk/Gtot,stck)(1 − λ(Tcellk − Tcell,stc))

Ppvk = ηinv × ns × np × (Gtotk/Gtot,stck)(1 − λ(Tcellk − Tcell,stc))

In the above equations, Tcell and Tout are, respectively, the cell and outdoor temperatures at k-th time step; Tcell,nom, Tout,nom, and Tcell,stc denote the cell temperature at nominal test conditions, the outdoor temperature at nominal test conditions, and the cell temperature at the standard test conditions, respectively. Moreover, Gtotk is the plane-of-array (POA) irradiance on PV panels at time step k, while Gtot,nom and Gtot,stc represent the irradiance at nominal and standard test conditions (STC), respectively, and do not vary over time; ηinv denotes the inverter efficiency, ns number of PV modules in each row, np is the number of rows, and λ is the cell temperature coefficient. All nominal and STC parameters come from the manufacturer catalogue.

3. Economic Analysis

Energy communities are still emerging in Canada. Especially in terms of collective generation, consumption, shared assets, and shared energy, there is an urgent need for modification and regulations. In this study, we compare two different mechanisms for developing an energy community in an existing mixed-use neighborhood in Montreal. Energy sharing and net metering are here analyzed and evaluated technically and economically.

3.1. Applied Mechanisms

This study compares two distribution strategies for energy communities (ECs): community net-metering (NM) and energy-sharing (ES) mechanisms. The aim is to evaluate these mechanisms in a Canadian neighborhood and to demonstrate the potential of mixed-use energy communities in advancing energy decentralization and reducing grid stress. In community net metering, each building first uses its renewable energy for self-consumption. Any surplus is fed into the grid, earning energy credits. In subsequent months or periods, community participants can use these credits as electricity imports from the grid, with the distribution based on their level of participation and cooperation in the community [54]. This mechanism, supported by programs from utilities such as the Hydro-Québec initiative [19], promotes renewable energy adoption and cost savings. The energy balance for each building is as follows:

Edemand,i (t) = EPV-self,i (t) + Egrid-import,i (t) − Egrid-export,i (t)

In energy sharing, common in European ECs, surplus energy is shared in real time among members. Producers are compensated for excess energy, while consumers pay less than grid rates [55]. This model encourages collaboration and maximizes renewable energy utilization within the community. The energy balance for each building is as follows:

Edemand,i (t) = EPV-self,i (t) + EPV-shared,import,i (t) − Egrid-import,i (t)

To highlight the benefits for diverse users, two buildings in this study were modeled as consumers only, rather than prosumers. They do not have any PV systems installed, and they use the surplus of the EC. This approach underscores how energy communities can benefit all members, even those without generation capacity, by fostering collective self-consumption and reducing costs [56].

The model focuses on analyzing the energy dynamics and economic impact of photovoltaic (PV) systems in a net-metering and energy-sharing context for a community of multiple diversified buildings. It leverages energy production and consumption data to optimize the use of PV-generated electricity, assesses financial metrics, and evaluates the system’s overall efficiency and sustainability. After simulating the building’s electrical loads and PV profiles through Tools4Cities, the hourly profile data are managed in a python script which simulates the interactions between the users of the community and performs the economic analysis.

The analysis starts from the calculation of the hourly net energy for each building, as the difference between the PV production and the building consumption. Under net metering, surplus energy (when PV generation exceeds consumption) is converted into credits which could be returned to the buildings as grid electricity. These credits can offset future energy consumption during periods of deficit (when consumption exceeds PV generation), according to the monthly accumulation allowed by the mechanism and the final balance will be applied to the customer bills. The model tracks these credits for each building over time by the end of the year.

While in energy-sharing mode, the surplus of each building is accumulated and redistributed (as internal energy trade) in the cluster in the priority of residential buildings, school and sport complex, offices, and retail. This hierarchy reflects a multi-criteria approach grounded in social equity, energy accessibility, and load alignment with renewable generation. Residential buildings are given precedence to ensure affordability for households and to promote energy justice, as they typically include vulnerable populations more sensitive to energy cost fluctuations [57]. Prioritizing households also aligns with the broader goals of decentralization and community empowerment, often emphasized in energy democracy frameworks [58]. Schools and sport complexes are placed second, given their important public service role and their operational alignment with peak PV production hours, making them ideal recipients of midday surplus energy [59]. Offices and retail buildings are ranked last, as they generally possess greater financial capacity to invest in their own energy solutions and face fewer barriers in accessing conventional energy resources [60]. This priority structure thus supports an inclusive and efficient distribution of shared renewable energy, maximizing both technical performance and social benefit within the community.

3.2. Key Performance Indicators

The initial net energy calculation is then adjusted by applying energy credits, thus simulating the net-metering process. Surplus energy increases credits, while deficit energy consumes available credits. The self-consumption rate indicates how much of the PV-generated energy is directly consumed by the building/community, without considering energy credits [61]. It is calculated as

SCR = (Eel,self/Eel,PV) × 100

The self-sufficiency rate shows the proportion of energy consumption needs met by PV generation [62]:

SSR = (Eel,PV/Eel,LOAD) × 100

These rates are calculated both for the community. Under the energy-sharing mechanism, at each simulation step the energy surplus and deficit per user are calculated and matched to maximize self-consumption.

The peak load reduction quantifies the effectiveness of installed photovoltaic (PV) systems in lowering the maximum load demand on the grid for a cluster of buildings [63]. It is calculated as the difference between the peak demand before and after PV integration, expressed both in absolute terms (kW) and as a percentage reduction.

In the economic evaluation, a detailed approach is essential for a comprehensive understanding of financial viability and sustainability. The investment cost per kW (jPV) plays a pivotal role, signifying the cost associated with purchasing and installing one watt of PV capacity. This cost directly influences the total investment (CAPEX) required for the PV infrastructure, calculated using the following formula:

CAPEX = PPV,TOT × jPV

CAPEX forms the basis for assessing project feasibility and return on investment. Here, the specific cost (jPV) includes both the equipment cost (e.g., PV modules, inverters) and the installation cost (e.g., labor, mounting, wiring).

Central to the analysis is the discount rate (r), reflecting the cost of capital and risk assessment, pivotal in NPV calculations. The NPV offers a comprehensive assessment of the project profitability over its expected lifetime, 20 years in this case study, factoring in the time value of money. In this case, ΔC represents the annual savings for the community, AF is the annuity factor, calculated basing on the lifespan and the discount rate (equal to 5%), and CAPEX is the capital cost of the PV installation. A positive NPV indicates that the project is expected to generate net earnings above its initial outlay, underscoring its financial viability. Moreover, the project lifetime significantly influences the financial metrics. The Simple Payback (SPB), defined as

indicates the time required for the EC to recoup its initial investment through savings on energy costs. A shorter SPB is indicative of a quicker return on investment, enhancing the project attractiveness. These economic parameters are crucial for stakeholders in ECs to make informed decisions regarding the adoption and optimization of PV systems [64]. These include the balance between initial costs, operating costs savings, and financial returns, offering insights into the economic feasibility and benefits of renewable energy investments [65]. An in-depth economic analysis is performed based on this model in the Section 5.

SPB = CAPEX/ΔC

4. Case Study

The selected case study is a mixed-use area in Montreal. The selected mixed-use area in Montreal was chosen for its representativeness and strategic relevance. The neighborhood displays a diverse building stock, including residential, commercial, educational, and recreational functions, making it suitable for analyzing the dynamics of a heterogeneous energy community. Various datasets on building geometries, constructions, and usages have been collected for the island of Montréal to create the respective archetypes. The construction archetypes for Montreal were created mainly using the datasets from the Natural Resources of Canada (NRCAN). The National Energy Code for Buildings [66] dataset, with fixed profiles for each building, is the main reference for usage and occupancy data on the island of Montreal. The validation of these archetypes is explained in detail in [51].

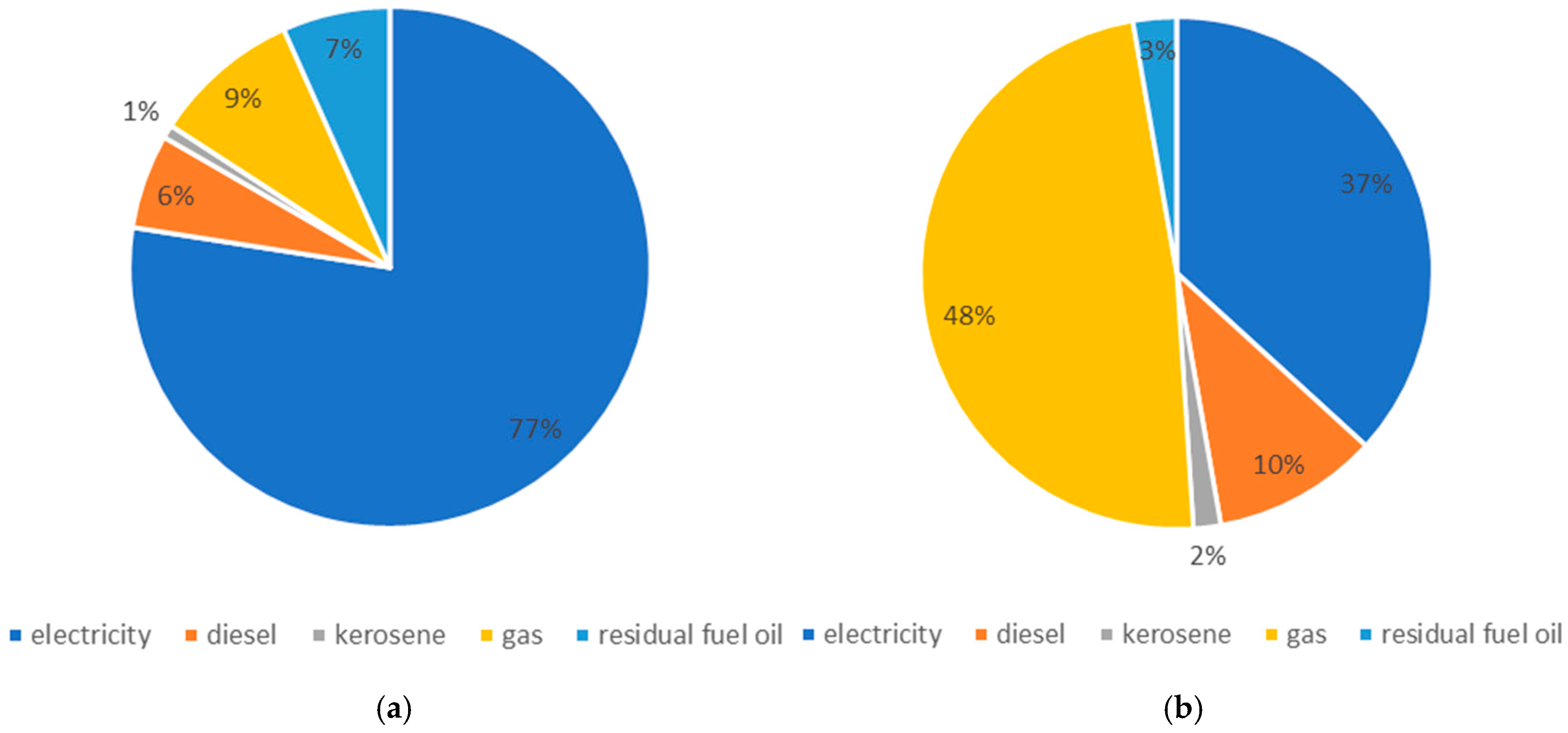

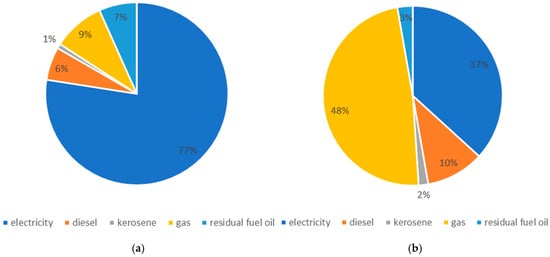

Regarding the existing energy system in each building, the energy system archetypes from the building code NECB 2020 are assigned to the buildings based on the building function (see Table 2). However, no information about the fuel type is available from this table. Therefore, additional datasets were needed to assign energy systems to buildings based on function and fuel type. In this regard, the results of the surveys conducted by Statistics Canada for residential and commercial buildings [67,68] were used to randomly, but statistically correct, assign energy system archetypes to the buildings in the selected area. Figure 2 shows the share of different fuels in the heating sector for residential and commercial buildings in Quebec.

Table 2.

NECB 2020 energy system archetypes based on the building function.

Figure 2.

Data share of different fuels in the heating sector of (a) residential (b) non-residential buildings.

The case study is an existing mixed-use neighborhood in the island of Montreal. The area considered, having large roof surfaces and low to mid-rise buildings, has great potential for rooftop PV installation. As it is presented in Figure 3, the cluster of buildings consists of (from right to left) a low-rise retail store, a number of offices in a complex almost as tall as the retail store, three blocks of two-story residential mid-rise buildings with similar construction patterns (no risk of shading), a double story educational center next to the residential block, and a single-story sport complex. We assume the sport complex is using the surplus electricity generated by the school PV system, so the sport complex is considered only as consumer. Also, the residential complex at the top (No. 65,570 in the image) is considered as consumer, consuming the neighboring building’s PV electricity. The rest of the buildings are assumed to be prosumers and the whole energy community is grid connected. As mentioned, the building energy consumptions are simulated by the Tools4Cities platform. The rooftop PV capacities also have been calculated and designed based on the maximum area available for rooftop PV installation. The actual capacity of PV was calculated as the product of the power of a single module, times the number of modules fitting in the area available for PV installation, assumed equal to 60–70% of the rooftop area, which is based on the roof available area excluding the obstructions and edges [69].

Figure 3.

(a) Top-view of the selected mixed-use neighborhood in Montréal, extracted from Google Earth, showing the spatial arrangement of the analyzed buildings. (b) Corresponding 3D representation of the same area generated from the GeoJSON dataset and visualized through the Tools4Cities platform. Each colored object corresponds to an individual building modeled in the renewable energy community (REC) simulation, identified by its unique building code.

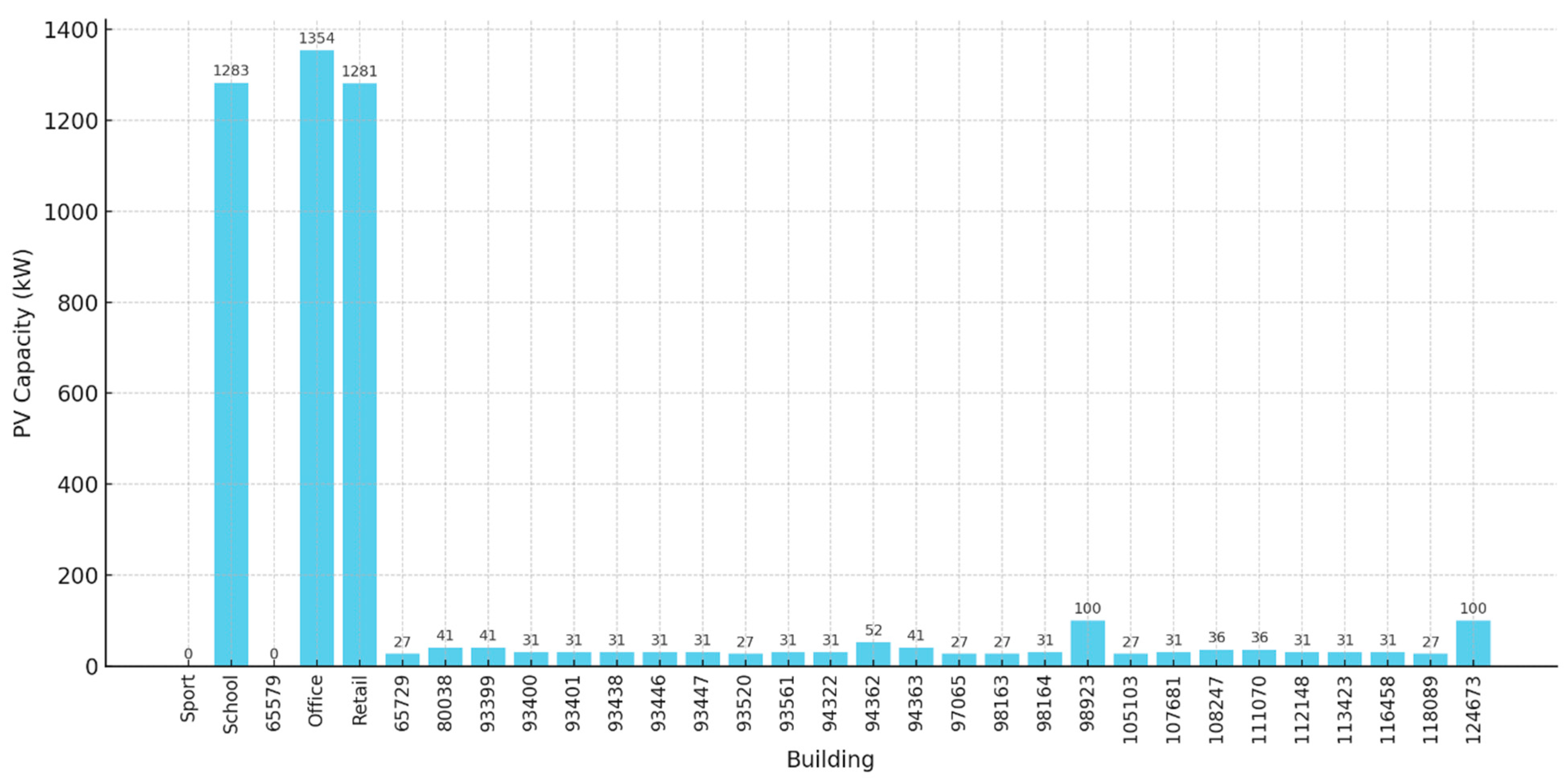

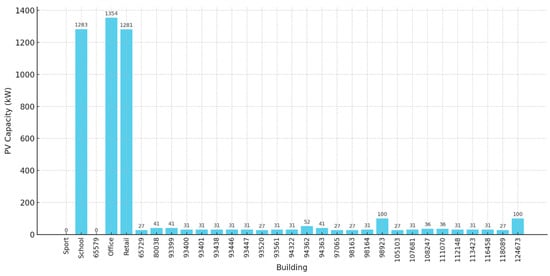

Figure 4 shows the PV capacity for each building of the REC; the numbers on the x-axis refer to the code number of the building (numbered buildings are all residentials), also shown in Figure 3. The simulations clearly show that the highest PV capacities are concentrated in large non-residential buildings—specifically office, school, and retail buildings—while the majority of residential buildings host considerably smaller systems. This highlights an important aspect of urban energy planning: in dense city environments, large non-residential buildings represent strategic opportunities for deploying photovoltaic systems, given their larger and less obstructed roof surfaces, as well as their energy demand profiles that often align better with solar generation patterns. Consequently, these buildings can play a pivotal role in supplying electricity to the district level, particularly when integrated with energy-sharing mechanisms or community energy models [70].

Figure 4.

PV capacity for all the buildings of the selected community.

The heating and cooling energy systems of the residential buildings are electrical. In case of non-residential building of the cluster, the heating systems are non-electric and mostly gas boilers, so the analysis has been conducted excluding the heating demand of the non-residential buildings.

Since Canada currently lacks a formal regulatory framework for energy communities or dynamic compensation schemes for electricity exports, a conservative assumption was made for simulation purposes. Surplus PV electricity exported to the grid is assumed to be compensated at 25% of the retail electricity rate for each building. This percentage is aligned with international practices in countries that have implemented net billing or energy-sharing mechanisms, where the export compensation typically ranges from 20% to 30% of the retail price [71,72]. The chosen rate reflects the avoided cost of electricity generation without including transmission and distribution services and serves as a reasonable approximation of the potential market-based compensation in a future Canadian regulatory context.

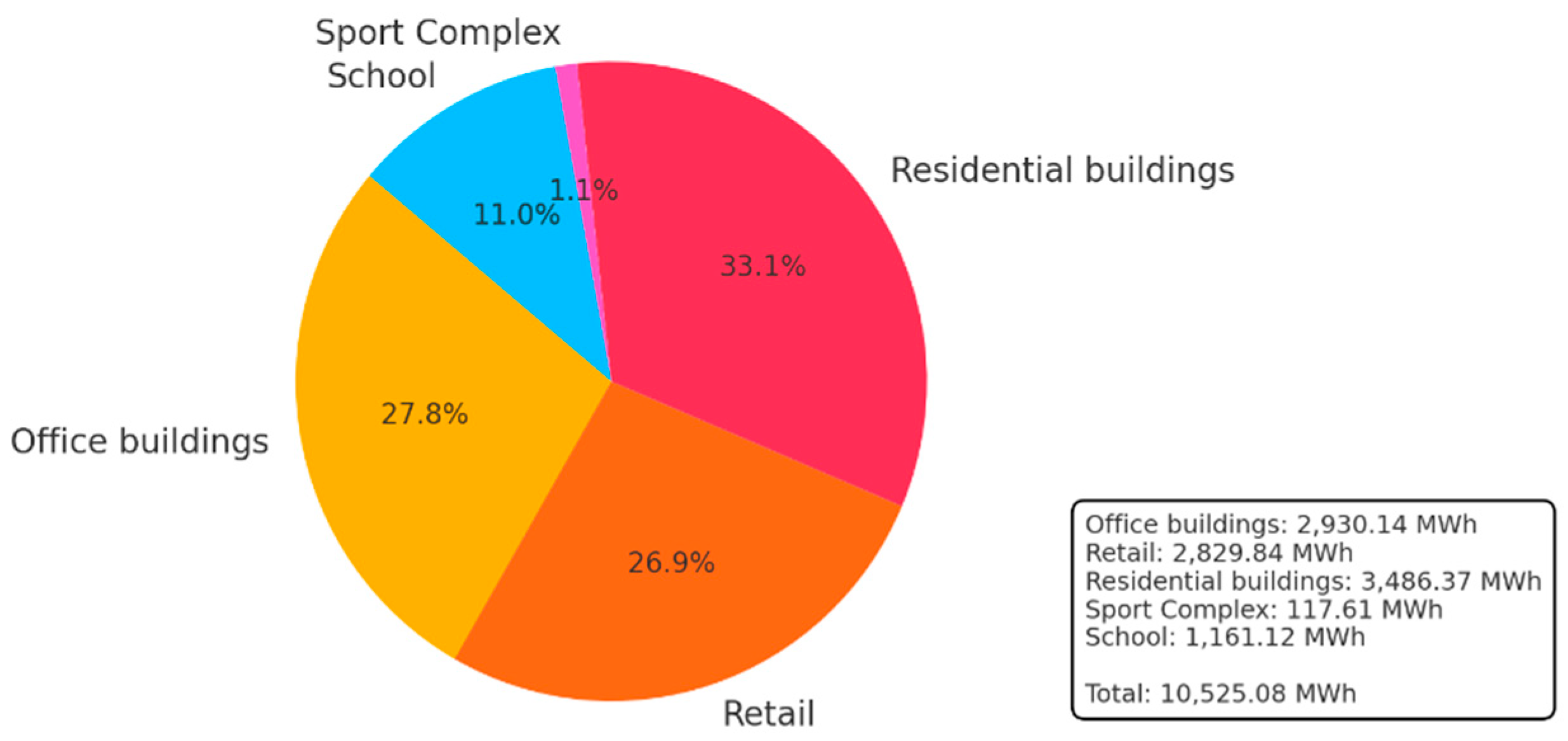

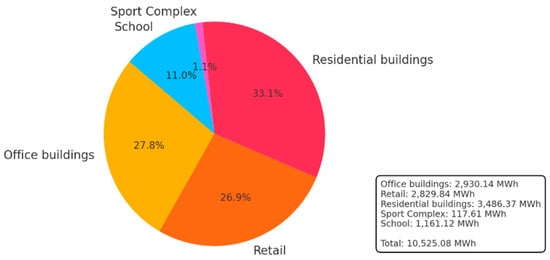

The pie chart in Figure 5 illustrates the annual electricity consumption distribution across various buildings in the cluster, with “residential buildings” consuming the highest proportion (33.1%) and “sport complex” consuming the least (1.1%). The total electricity consumption is 10,525.08 MWh, with specific consumption values detailed in the bottom-right box. The highest electricity consumption is due to the residential buildings, that are 27 in the area selected.

Figure 5.

Share of electricity consumption for each type of building in the community.

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results of the buildings’ load simulation obtained with the new platform developed and the energy and economic analysis of the energy-sharing mechanisms compared for the selected community. Additionally, a sensitivity analysis and a discussion of the results obtained are included, to investigate more about tecno-economic feasibility of RECs in North America, specifically Canada.

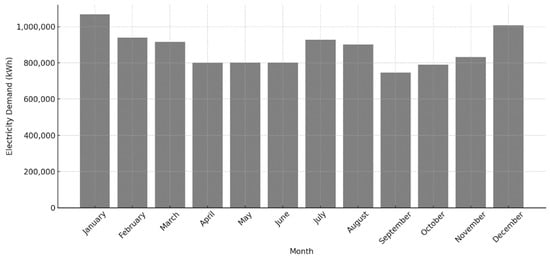

5.1. Model Validation

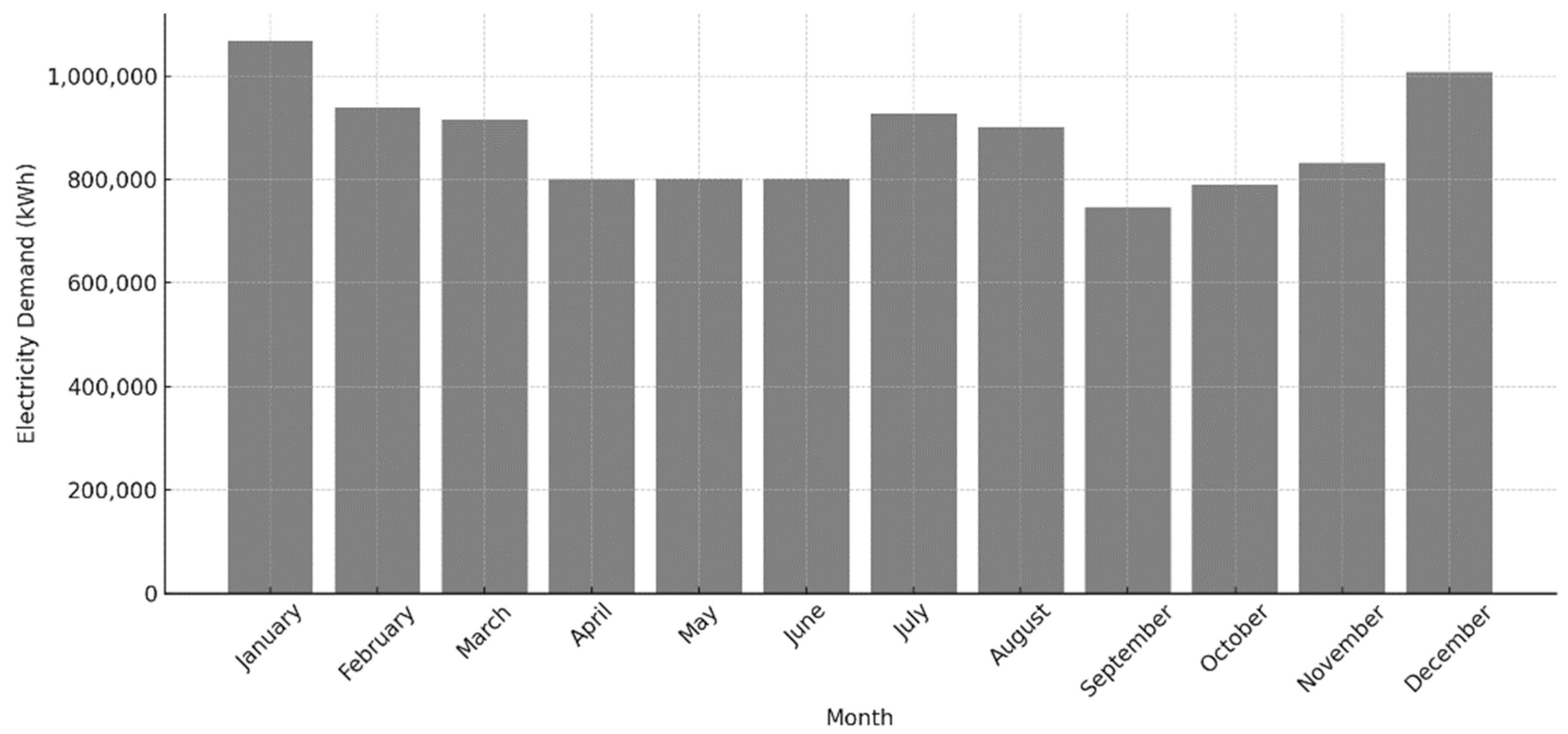

As shown in Figure 6, monthly electricity demand of the cluster reflects the simulated behavior of the selected mixed-use buildings. While direct validation against measured data is not feasible due to the absence of high-resolution, disaggregated real-world consumption data for the buildings modeled (which span both residential and commercial uses), the simulation is grounded in a robust and recognized modeling framework. The demand profiles were generated using Energy Plus, one of the most widely used and validated building energy simulation tools in the scientific community, incorporating validated algorithms for HVAC, lighting, plug loads, and occupancy behavior [73]. Therefore, although empirical validation is limited by the absence of detailed real-world datasets, the adopted methodology ensures that the simulated consumption profiles are intrinsically validated and representative of typical behavior in cold-climate mixed-use districts [74].

Figure 6.

Monthly cumulative simulated electricity demand of the buildings in the community.

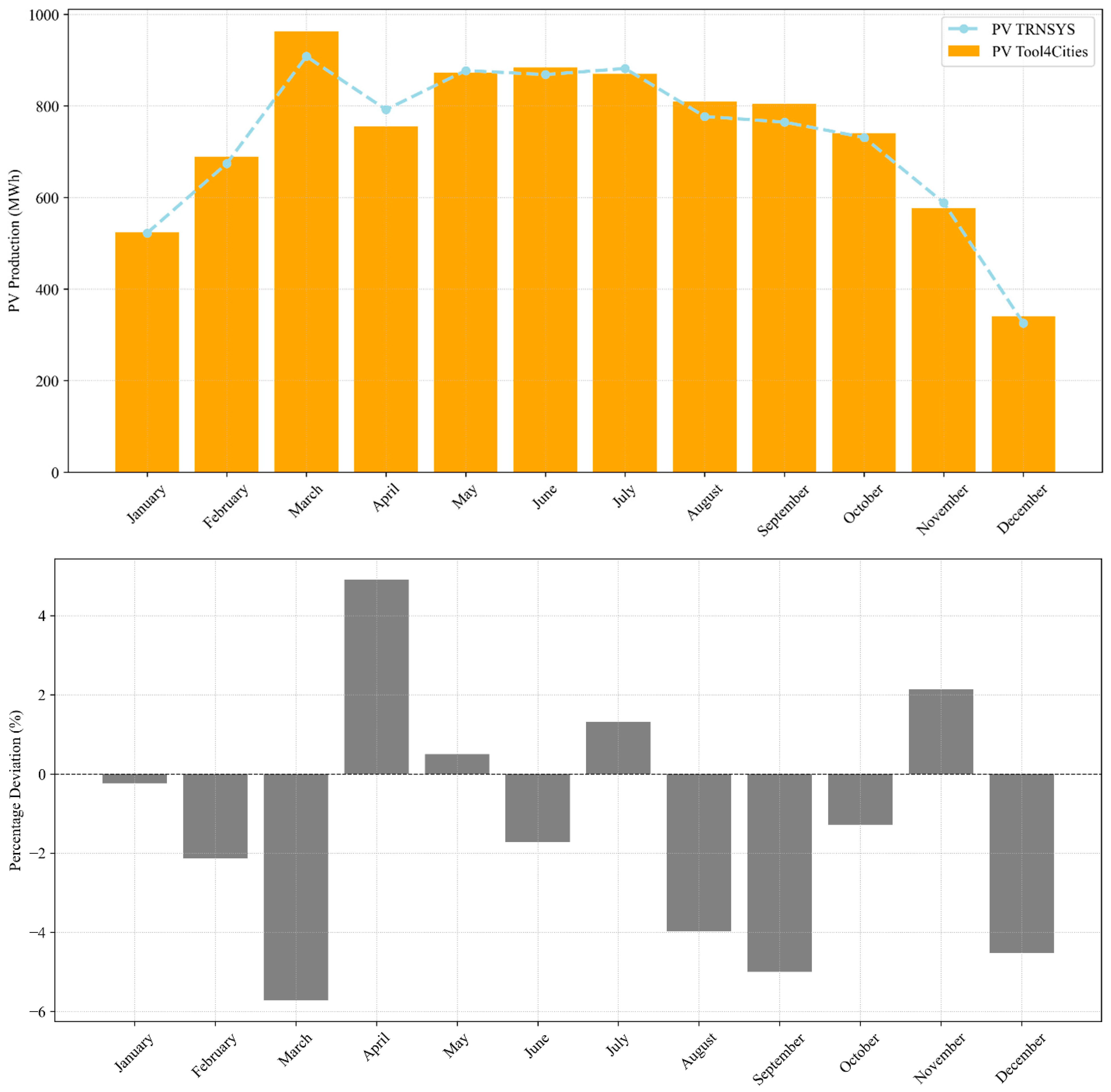

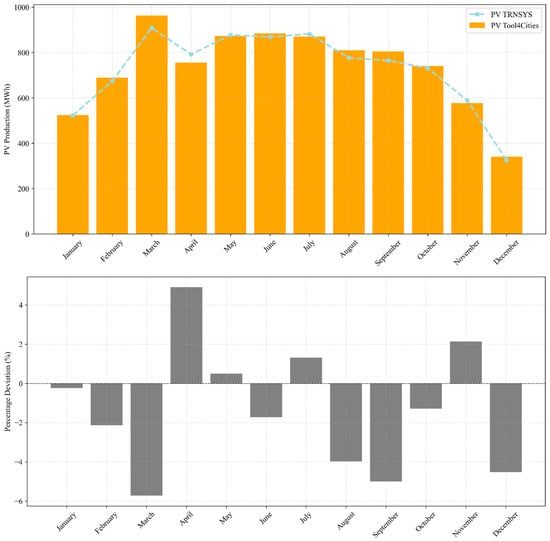

Figure 7 compares the monthly cumulative simulated electricity production from rooftop PV generated by the present workflow (PV Tool4Cities) with results from TRNSYS simulations, a well-established tool for dynamic energy system analysis. The top panel shows a close alignment in production trends across all months, with the yellow bars representing the PV Tool4Cities outputs and the light-blue dashed line with markers showing TRNSYS data. The bottom panel displays the monthly percentage deviation between the two simulation tools, which remains generally within a ±5% range for most of the year.

Figure 7.

Monthly cumulative simulated electricity production from rooftop PV: comparison between data simulated in this workflow (yellow bars) with TRNSYS simulated data (light-blue dots)—(top). Percentage deviation plot—(bottom).

This comparison supports the robustness of the PV modeling approach adopted in this study. Although slight monthly discrepancies exist due to differences in the internal irradiance processing algorithms and system modeling assumptions, the overall deviation remains limited. Moreover, TRNSYS is internationally recognized for its accuracy in simulating energy systems and has been widely validated across hundreds of peer-reviewed studies [73]. Thus, aligning the PV production results with those of TRNSYS serves as an indirect but effective validation of the Tool4Cities simulation engine, reinforcing its credibility for assessing rooftop PV potential in urban-scale energy communities.

5.2. REC Simulation Analysis

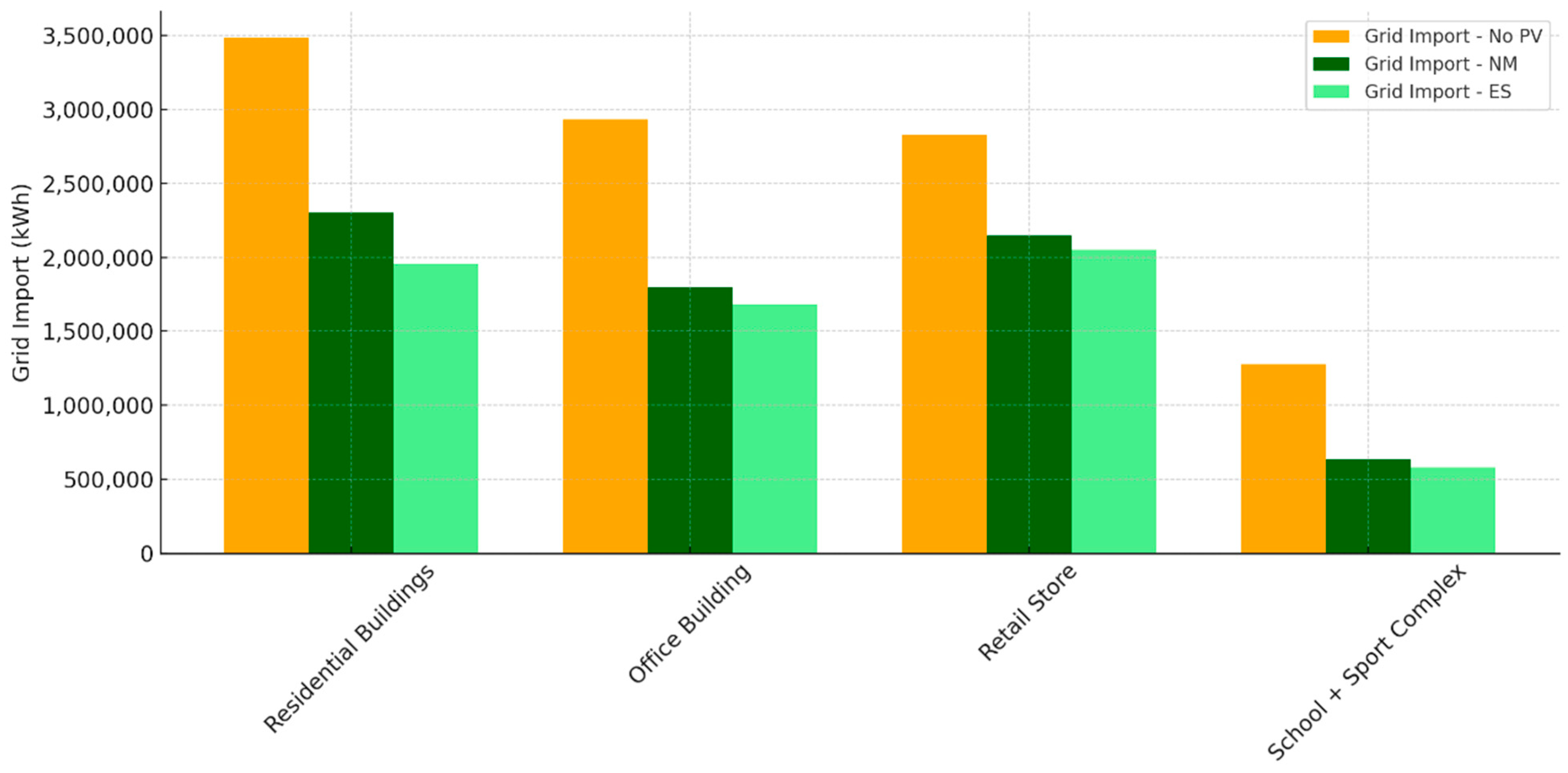

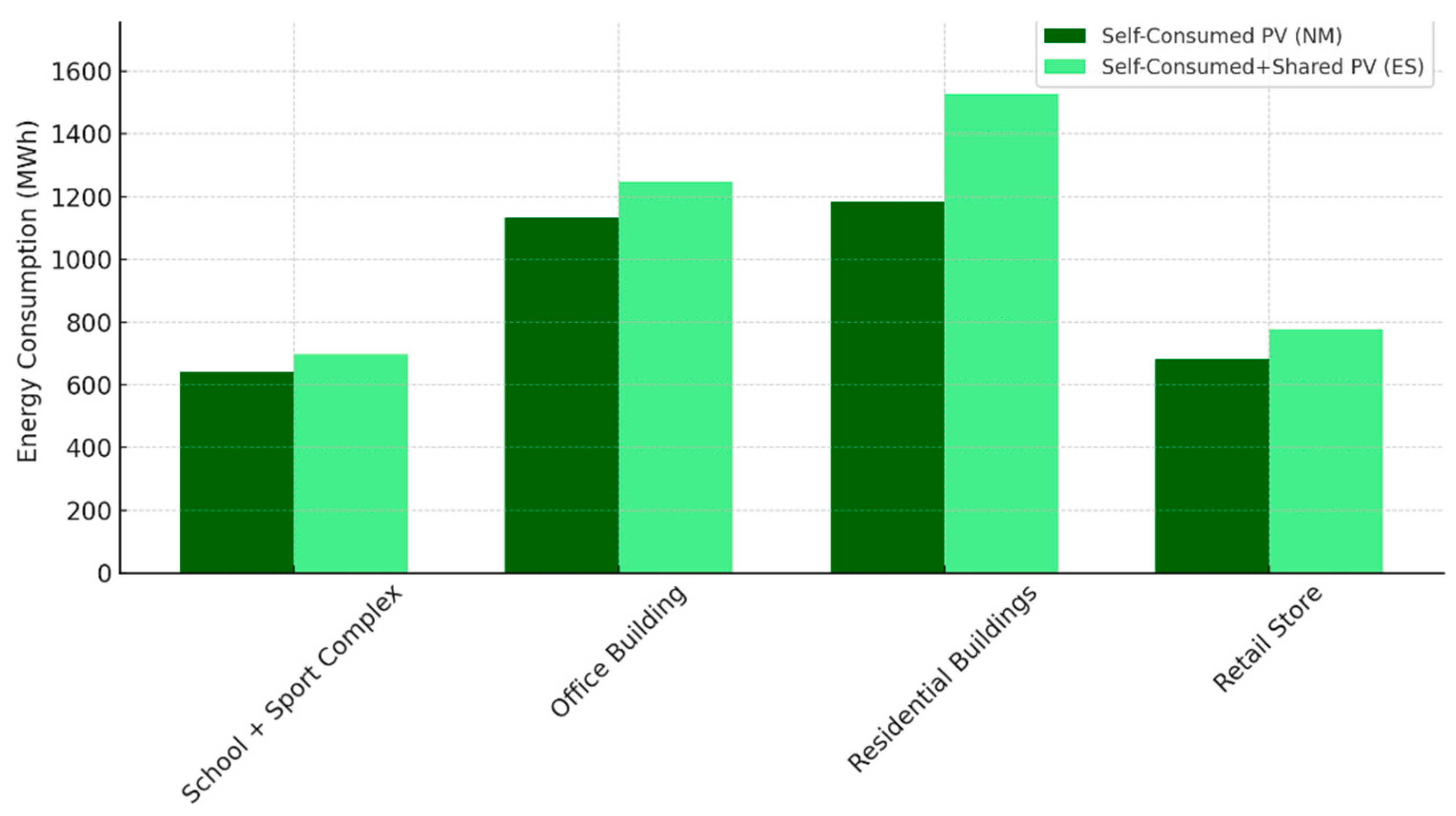

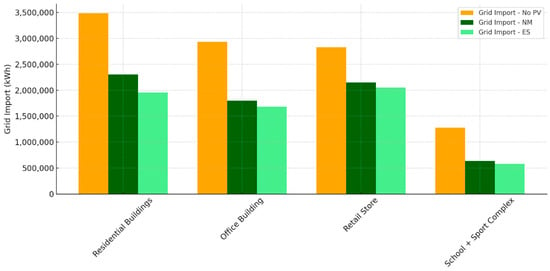

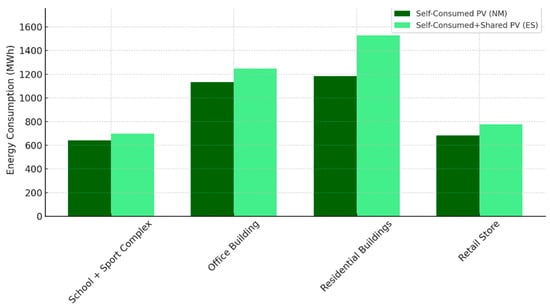

Figure 8 shows how much the grid dependence of a cluster of building was reduced after installing PVs, both in the case of NM and ES mechanism adoption.

Figure 8.

Reduction of grid import across four different types of building, under base case, net-metering and energy-sharing scenarios.

Specifically, the graph illustrates the grid import across four sectors (residential buildings, office buildings, retail stores, and school + sport complex) under three cases: no PV, NM (net metering), and ES (energy sharing). The results highlight how PV systems significantly reduce grid dependency across all sectors, with the energy-sharing (ES) mechanism achieving slightly better grid independence compared to net metering (NM). This result is in line with the concept of the ES mechanism, which increases the self-consumption of renewable electricity. In this case, electricity surplus from one user is sent to other users whose demand is nonzero rather than being supplied directly to the grid. In case of NM mechanism, the renewable energy surplus is supplied to the grid and drawn from the users in the following month, but this electricity cannot be considered self-consumed by the community.

Residential buildings exhibit the highest grid import across all scenarios due to their substantial electricity demand, driven by predominant electric heating systems, and the much higher number of buildings in the residential cluster. The “School + Sport Complex” is the building with the lowest electricity consumption, compared to the other clusters, and with the highest grid reliance reduction. The electricity drawn from grid drops from 1.25 GWh/year in the base case to nearly 0.6 GWh/year in the EC scenarios. The same applies to office buildings whose consumption decreases from roughly 2.8 GWh/year of the reference scenario to 1.7 GWh/year in the REC ones.

The ES mechanism performs better due to its ability to optimize energy distribution among participants, making sectors more independent of the grid. This suggests that implementing shared energy systems can be a key factor in achieving greater energy sustainability and reducing grid reliance in urban sectors.

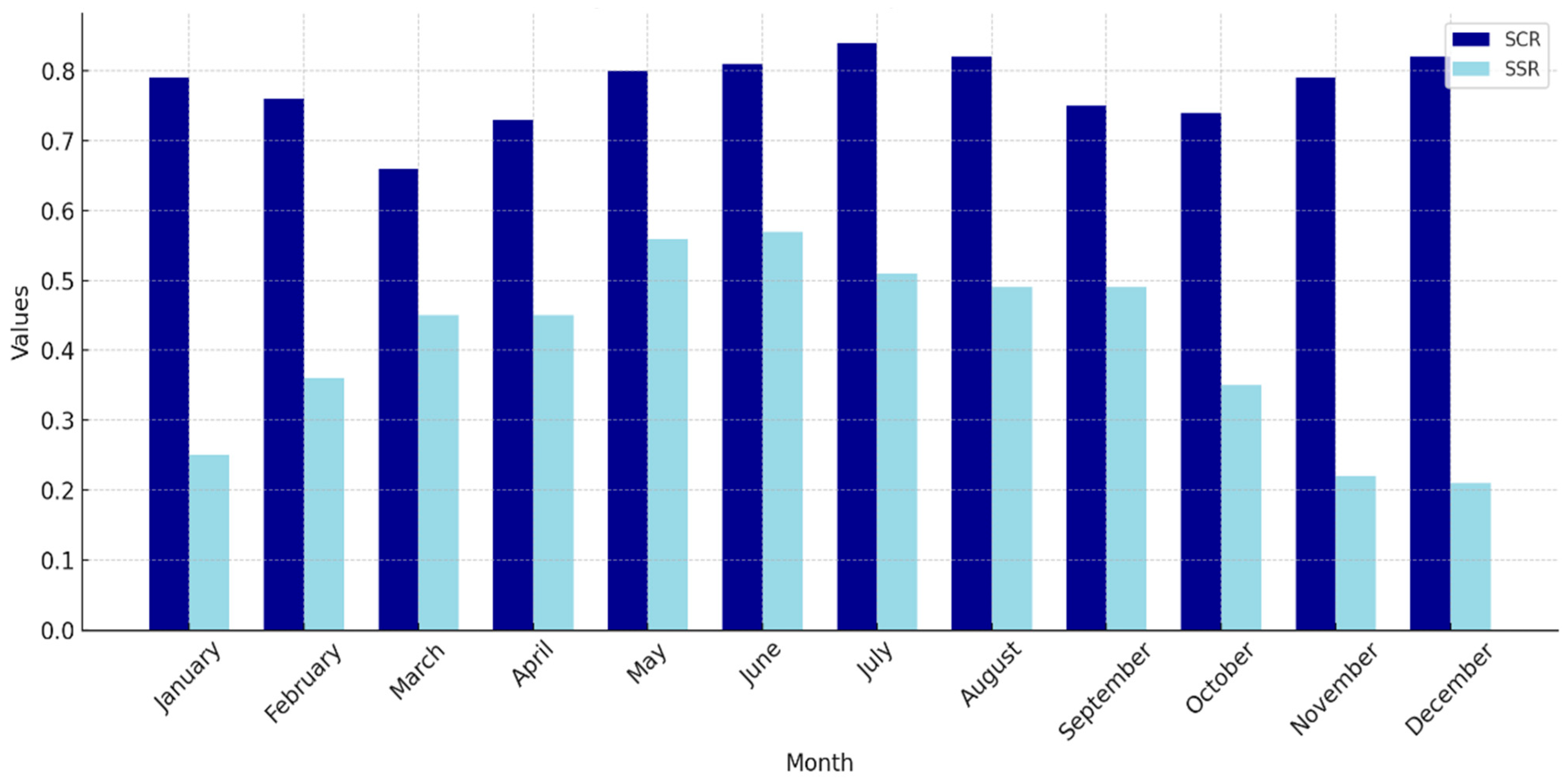

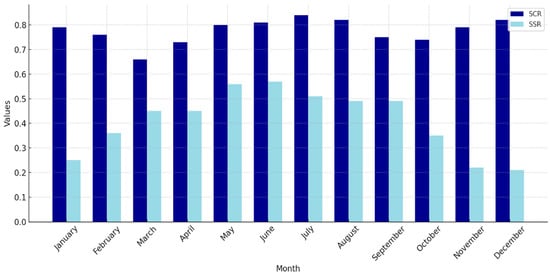

Figure 9 shows the monthly SCR and SSR for ES to show that the community is more independent in some months from the grid.

Figure 9.

Monthly Self-Consumption Ratio (SCR) and Self-Sufficiency Ratio (SSR) for the REC in case of ES.

The chart highlights the cluster ability to meet its energy demand using local PV generation. Higher SCR values indicate more efficient utilization of locally generated energy, while higher SSR values demonstrate greater independence from the grid. Notably, the summer months (e.g., May–August) exhibit higher SCR and SSR ratios due to increased PV availability, showcasing enhanced energy self-sufficiency during these periods. In contrast, winter months (e.g., December–February) show lower SSR values, reflecting increased reliance on the grid due to reduced PV generation. This seasonal variation emphasizes the importance of energy sharing and adding storage for year-round self-sufficiency.

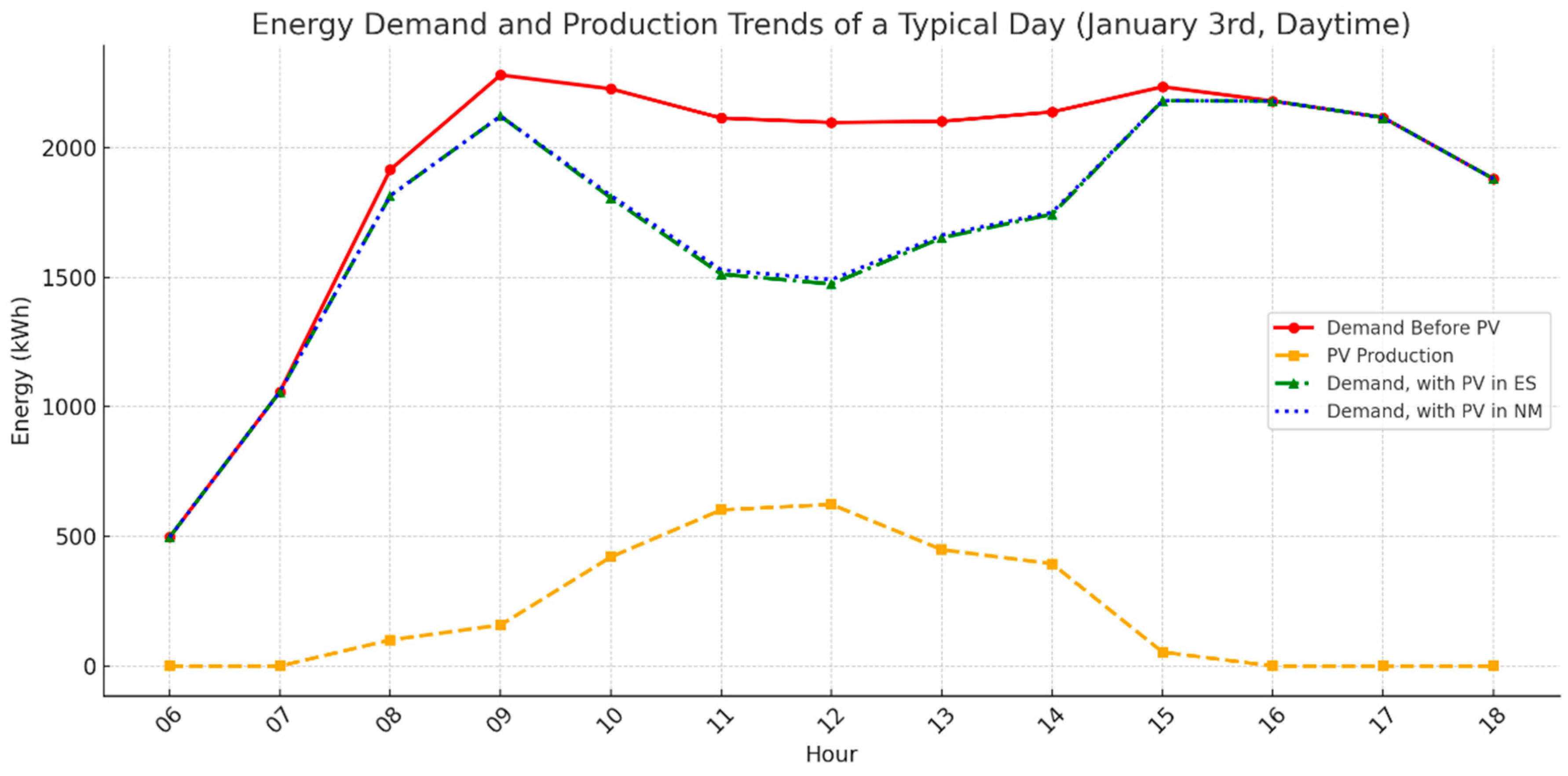

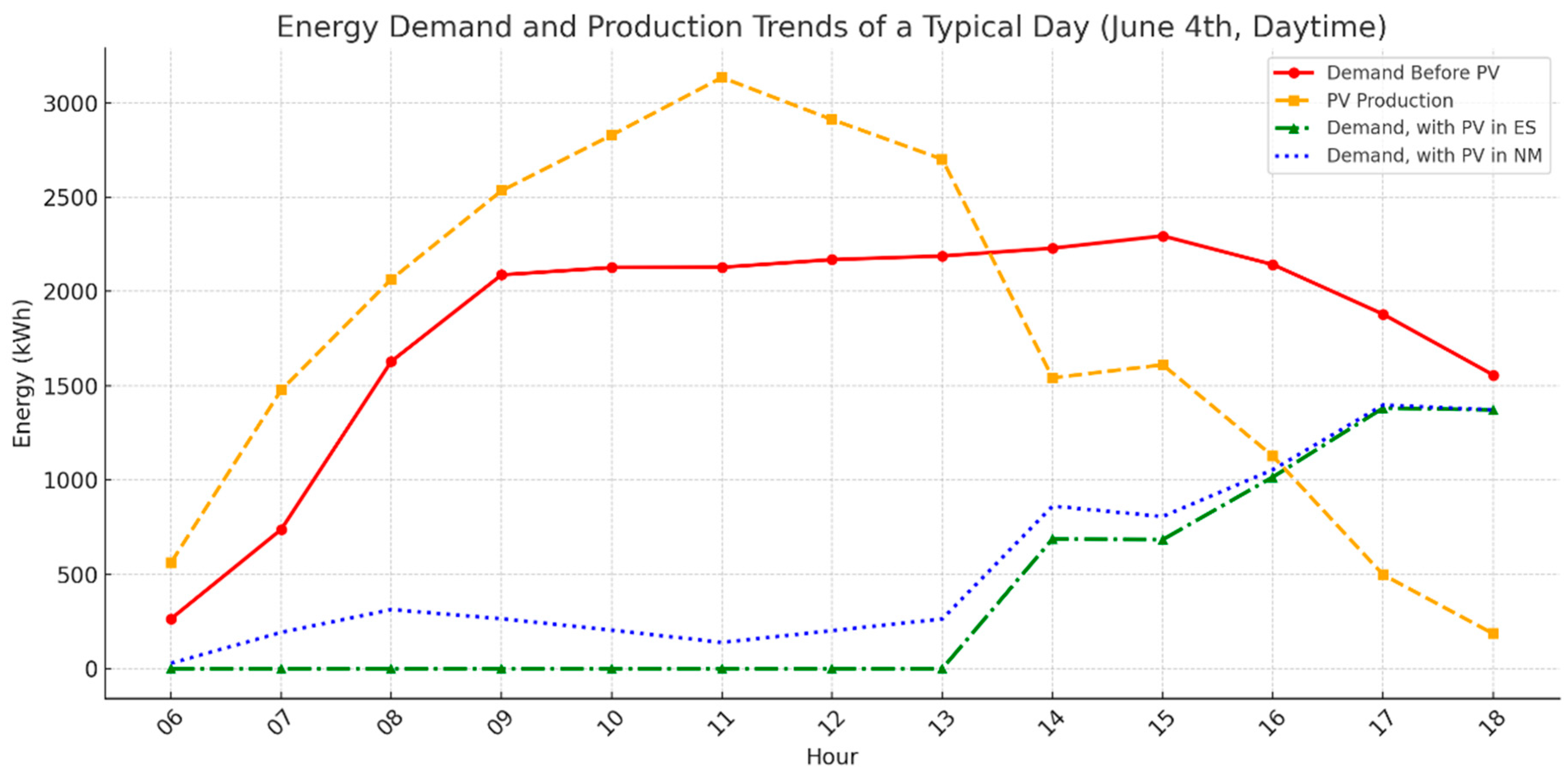

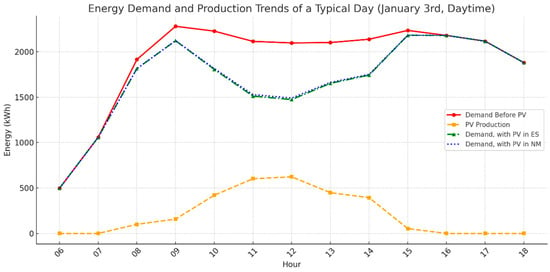

The graph in Figure 10 shows the effect of different mechanisms in comparison to the base case (no PV), for a typical working day in summer (top) and winter (bottom). The hours considered in the graph are the hours of solar radiation during the day.

Figure 10.

Effect of different mechanisms on the peak in comparison to the base case (no PV) for a typical winter day (top) and a typical summer day (bottom), during the hours of solar production.

The two graphs illustrate the power flows during the solar radiation hours for two typical days of winter (top) and summer (bottom). The PV generation is much higher in summertime (above 3000 kWh against barely 700 kWh in winter), making the EC independent from the grid during the morning peak hours (6–9 a.m. according to the Hydro Quebec report [75]) for the ES system (green curve in the bottom graph) and minimizing the overall daytime consumption. In contrast, during the winter day, the reduced PV availability limits its impact on morning peak but still provides significant reductions during midday hours, from 2200 to 1500 kWh. The energy-sharing scenario further optimizes PV utilization by redistributing excess generation within the cluster, minimizing reliance on external energy sources and enhancing energy self-sufficiency.

Figure 11 demonstrates how the energy-sharing mechanism enhances the utilization of PV energy by redistributing excess generation among various sectors, particularly benefiting residential buildings since they were prioritized to receive the excess first in case of shortage. In contrast, sectors like retail stores and schools and sport complexes show lower total PV supply due to their relatively smaller energy demands and reliance on non-electrical heating systems. This highlights the potential of energy sharing to improve the overall self-sufficiency of the community while addressing sector-specific needs.

Figure 11.

PV energy supply across different sectors throughout the whole year of simulation.

For the ES scenario, the REC benefits from an additional 613,518 kWh of self-produced PV through the redistribution of surplus electricity among buildings experiencing deficits. This redistribution directly increases the overall system efficiency, which is reflected in slightly higher values of the SSR and SCR when compared to NM.

Regarding peak load reduction, the average peak load reductions during predefined critical periods have been analyzed:

- Winter morning peak: 6:00–9:00 a.m. (Dec–Feb)

- Winter evening peak: 5:00–8:00 p.m. (Dec–Feb)

- Summer afternoon peak: 2:00–6:00 p.m. (Jul–Aug)

During the winter evening peak (5–8 p.m.), when solar PV output is negligible, no peak load reduction was observed, confirming the limited effectiveness of PV-based interventions during sunless hours. In contrast, during the summer afternoon peak (2–6 p.m.)—when PV production is at its highest—peak shaving reached 30.34%, demonstrating the strong alignment between solar availability and cooling-driven demand. Additionally, a 15.59% reduction was achieved during the winter morning peak (6–9 a.m.), despite relatively low solar generation, highlighting some benefit from solar contributions and energy sharing. These seasonal insights emphasize that while annual peak shaving (27.58%) provides a broad performance metric, a seasonal peak load analysis offers a more nuanced and realistic assessment of REC performance under varying climatic and demand patterns, particularly in regions like Quebec where seasonal variability and time-of-use pricing policies play a critical role in energy planning. Table 3 summarizes these findings.

Table 3.

Electricity grid import peak shaving after PV installation in the community.

Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 present the results of the technical and economic KPIs used to evaluate the net-metering (NM) and energy-sharing (ES) mechanisms. The first row shows the PV utilized in each mechanism. In this study, for the NM scenario, only the PV self-consumption during the daytime of the REC is accounted for. The PV credited to the community account and later imported from the grid is considered only in the economic KPIs, not in SSR or SCR.

Table 4.

Hydro-Québec electricity rates for all the different building categories.

Table 5.

Economic analysis for the first year of operation of the system.

Table 6.

Main KPIs from the techno-economic analysis of the ES and NM solutions.

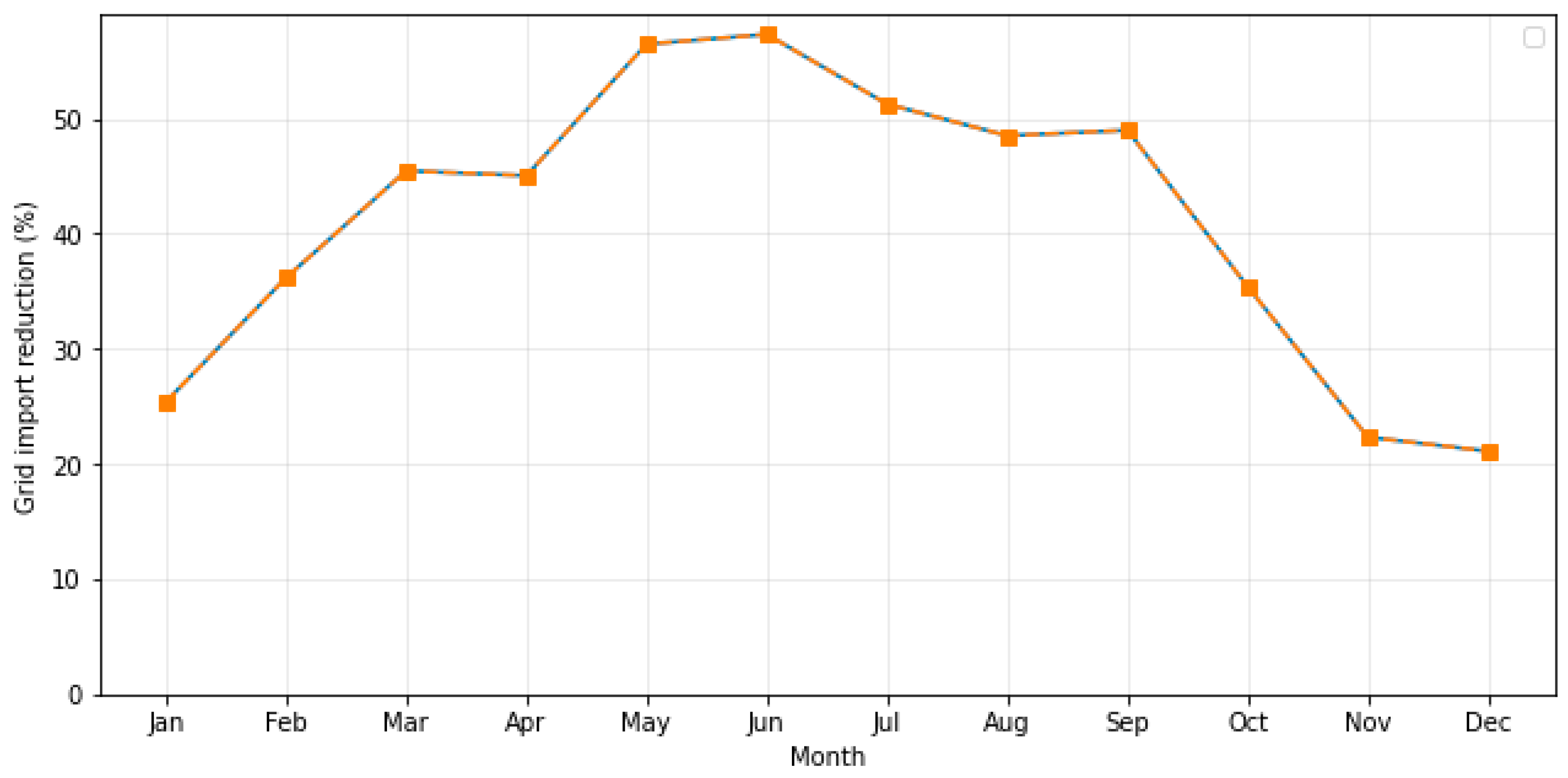

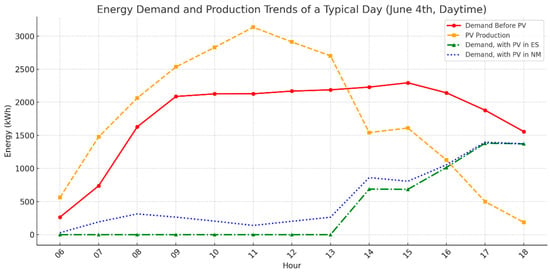

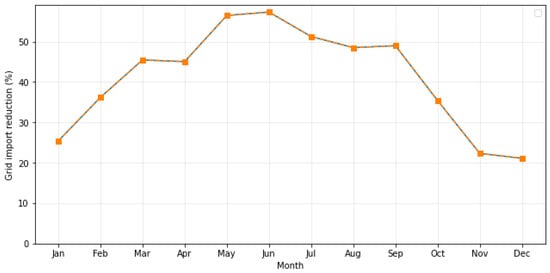

To provide a broader seasonal overview beyond the single-day comparison, Figure 12 reports the monthly reduction in electricity imported from the grid relative to the no-PV baseline. The reduction was calculated as the ratio between the baseline monthly imports and those obtained under PV operation.

Figure 12.

Monthly reduction of electricity imported from the grid.

The results reveal a clear seasonal dependence consistent with PV generation patterns. From January to March, the reduction in grid imports remains below 40%, reflecting low solar availability. It then increases sharply from April, reaching a maximum of about 55–58% in May–June, when PV output and daylight duration are highest. During summer months (June–August), the reduction stabilizes around 50%, before gradually declining through autumn and reaching its minimum (~20%) in November–December.

This confirms that the ability of the REC to reduce dependence on the grid is strongly seasonal, driven by solar resource availability rather than by demand variations. The monthly analysis complements the daily profiles of Figure 10, showing that summer operation enables more than twice the grid import reduction compared with winter. Such insight also highlights the potential benefit of coupling PV with short-term storage or demand-side management to mitigate the seasonal mismatch between generation and consumption.

The economic KPI results are not attractive for this community, which comprises 31 buildings, including a large retail store, a complex of office buildings, a school, a sports complex, and 27 mid-rise multi-household buildings. Despite the great reduction of electricity consumption from the grid, decreasing from roughly 10 GWh per year to nearly 6 GWh per year, the EC does not show any financial feasibility. The reason lies in the high cost for PV installation in North America—higher than 2 USD/Watt [76]—compared to lower average installation costs observed in regions such as Europe (around 1.1–1.5 USD/Watt) and Asia (approximately 0.8–1.2 USD/Watt) [77]. (The marked cost disparity is primarily driven by regional differences in soft costs. These include customer acquisition, permitting, inspection and interconnection, installation labor, and financing expenses. According to a summary of IEA’s analysis, these soft costs are significantly higher in North America, resulting in elevated overall installation prices, whereas Europe and Asia benefit from more streamlined administrative procedures and lower labor overheads and in the very low cost of electricity from the grid.) In this case study, to zero the NPV, 8.72 M USD and 8.17 M USD are needed as incentive for the CAPEX for ES and NM mechanisms, respectively.

Finally, the slightly higher NPV for NM compared to ES is due to the kWh of electricity that the REC can retrieve from the grid as credits for surplus PV sent to the grid in previous months which cause a drop in operational cost of the REC annually and consequently in NPV.

This analysis highlights that both NM and ES mechanisms significantly enhance the SCR and SSR of the REC compared to a baseline scenario without PV integration. However, the ES mechanism consistently outperforms NM in both metrics, reaching a 77% SCR and 40% SSR versus 66% and 35% for NM, respectively. This is attributed to ES ability to redistribute excess PV generation among buildings with unmet energy demand, optimizing the use of locally generated renewable energy.

Seasonal variations in SCR and SSR, as shown in Figure 9, reveal the strong correlation between PV effectiveness and solar availability, with performance peaking during the spring and summer months. Although both mechanisms reduce grid reliance year-round, their impact is most pronounced during periods of high irradiance. These findings reinforce the potential of integrating energy storage systems to mitigate the drop in self-sufficiency during winter.

Both NM and ES also demonstrate strong potential for peak load reduction—an increasingly important KPI in Quebec given grid stress during temperature extremes. Peak load (daytime) is reduced on average by 47% for NM and 50% for ES. These reductions, which are particularly significant during the summer cooling season, indicate the ability of decentralized PV systems to flatten peak demand curves.

In the ES scenario, surplus PV redistribution further enhances peak shaving, especially during community-wide high-demand hours, as shown in Figure 10. This functionality provides substantial value in supporting grid resilience during critical periods in Quebec’s hydro-dominant energy system.

The implementation of this energy-sharing analysis is made possible through a novel, integrated modeling workflow that combines spatially accurate irradiance simulation, hourly demand modeling, and energy redistribution algorithms under both NM and ES strategies. Unlike conventional approaches that often lack scalability or require intensive input data, this framework enables urban-scale evaluation of RECs with limited empirical datasets—particularly suited to mixed-use urban districts where data availability is sparse.

From an economic perspective, the analysis exposes considerable feasibility challenges for both NM and ES under current market conditions. Despite favorable technical performance, both configurations yield negative net present values (NPVs): −USD 8.6 M for ES and −USD 8.2 M for NM. These results highlight the mismatch between capital costs of PV infrastructure and the low electricity tariffs in Quebec, which dampen financial returns. While ES demonstrates better technical performance, NM shows a slightly better economic outlook due to grid compensation for exported surplus.

These findings underscore the urgent need for supportive policy interventions—such as CAPEX subsidies, dynamic pricing schemes, or incentivized storage integration—to unlock the full potential of RECs in Canada. Nonetheless, even in the absence of financial viability, the operational benefits of ES and NM mechanisms point to their long-term strategic value in enhancing energy resilience, decarbonization, and local autonomy in urban energy systems.

The comparative assessment of net metering (NM) and energy sharing (ES) reveals complementary strengths and weaknesses that are relevant to both policy design and community operation. While NM provides a straightforward and administratively simple mechanism for individual prosumers, ES offers superior technical performance by enabling collective optimization at the community level. Table 7 shows a summary of pros and cons of both mechanisms.

Table 7.

Summary of advantages and disadvantages of NM and ES mechanisms.

In summary, NM is advantageous in contexts with clear regulatory structures and simple billing schemes but is limited in fostering community-level energy optimization. Conversely, ES maximizes local renewable utilization and grid resilience but requires more sophisticated governance and data infrastructures. In the Canadian context—where RECs are still unregulated—the hybridization of NM and ES principles could represent a pragmatic transitional strategy.

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis

Quebec’s heavy reliance on hydroelectric power, a low-cost and renewable energy source, presents a unique context for evaluating the role of PV systems and energy-sharing mechanisms [78]. Quebec’s grid is overwhelmingly powered by hydroelectricity: the residual electricity supplied through Hydro Québec’s main grid is comprised of ~97.3% hydro, ~0.5% wind, ~1.1% biomass/biogas, ~0.01% solar, ~0.7% nuclear, and ~0.5% fossil fuels—resulting in a nearly 98.9% renewable share and an emissions intensity of just ~2.5 kg CO2/MWh [14]. While these solutions offer clear benefits in terms of peak shaving and energy production diversification, their economic feasibility is hindered by the already low cost of electricity. However, the environmental and technical advantages of these mechanisms should not be overlooked. By diversifying the energy mix and reducing peak load stress, NM and ES contribute to the long-term sustainability and resilience of the Quebec energy system.

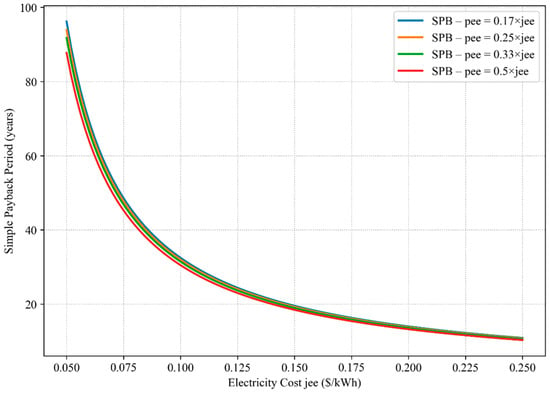

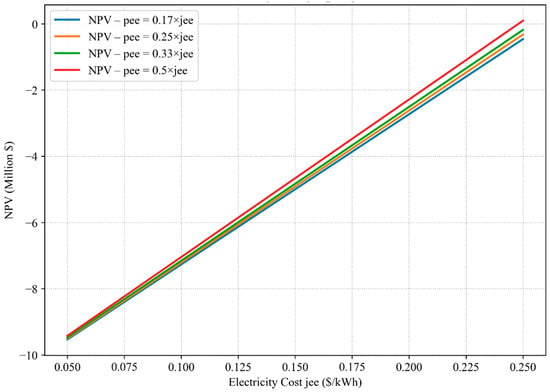

To complement the techno-economic evaluation and assess the robustness of the results, a detailed sensitivity analysis was carried out on key economic parameters, including the cost of electricity (jee), the export tariff (pee), and the capital expenditure (CAPEX) incentives. The analysis encompasses both deterministic and stochastic approaches to understanding how uncertainties in policy and market conditions could influence investment performance indicators, such as SPB and NPV.

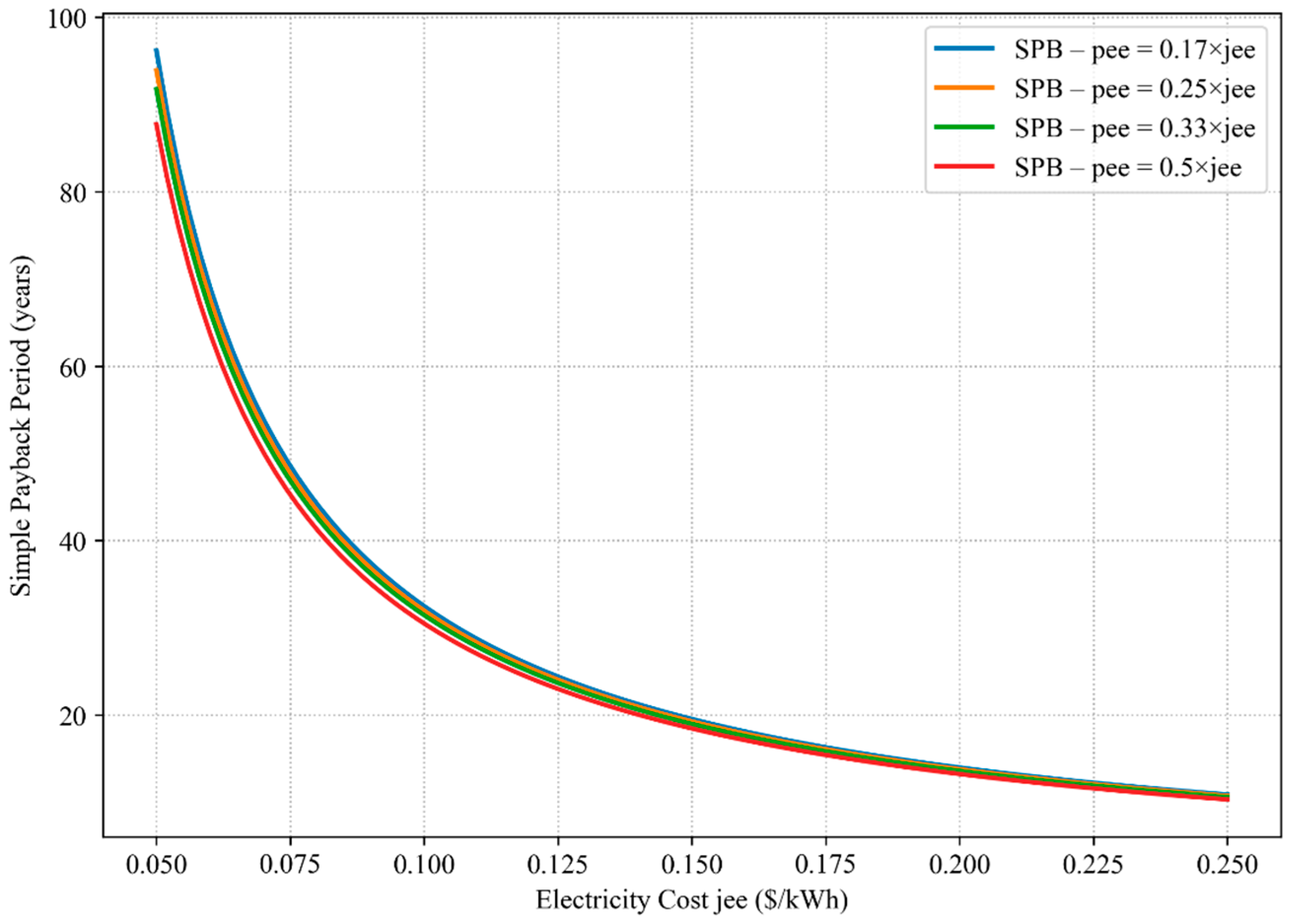

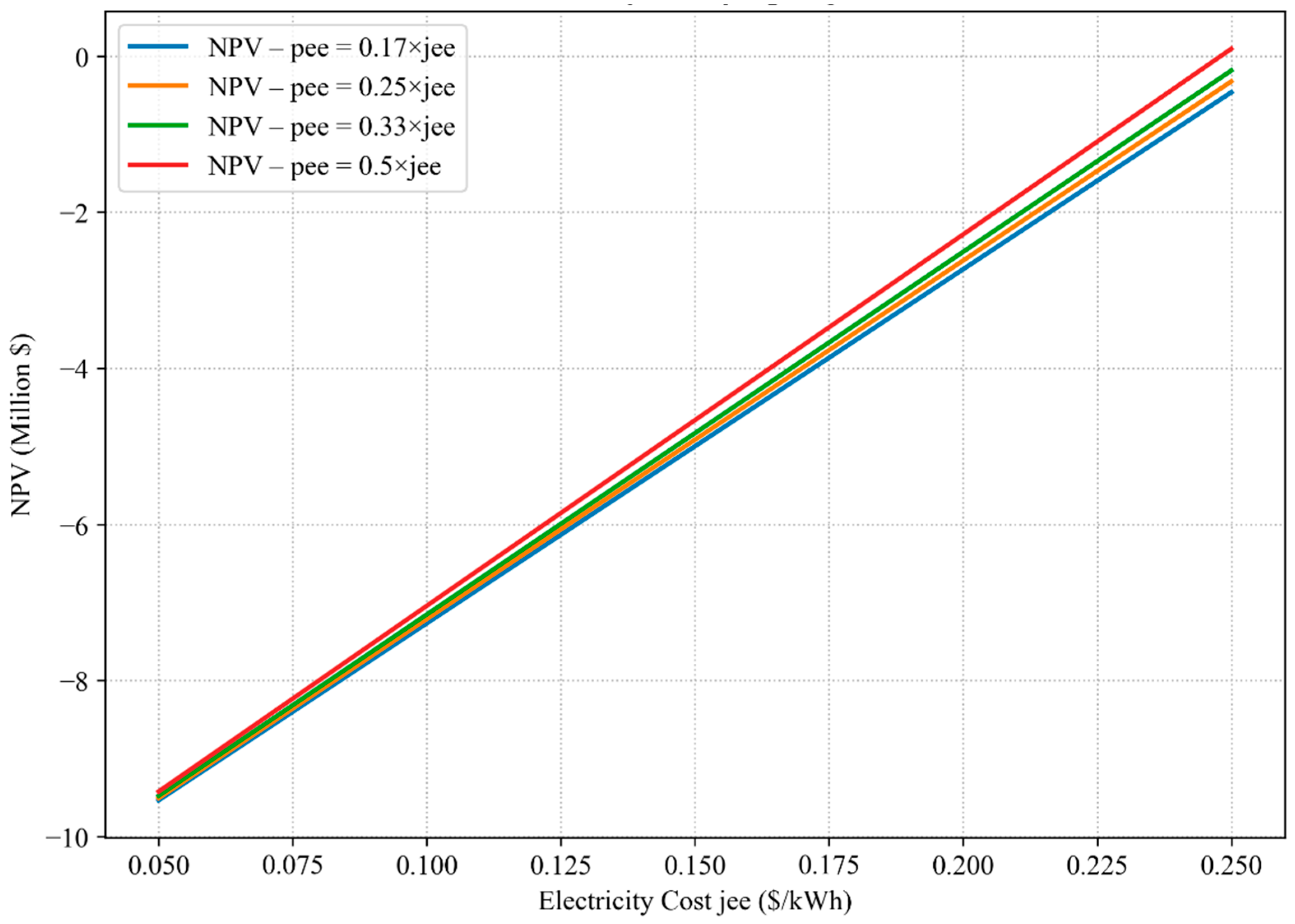

Because of the greater influence of feed-in tariffs on electricity purchase and selling, the sensitivity analysis was mostly focused on ES scenario. However, the results are similar for the NM one. Figure 13 and Figure 14 illustrate the influence of varying export tariff levels, defined as fractions of the electricity purchase cost (pee = [0.17, 0.25, 0.33, 0.5] × jee), on SPB and NPV, respectively. As expected, an increase in the electricity cost (jee) improves the investment performance due to higher monetary savings from PV self-consumption. Compared to import tariff, export tariff has a much lower impact on the economic feasibility of the solution proposed, mostly because of the low amount of electricity exported to the grid, which is also positive when targeting a minimal grid interaction. The SPB decreases non-linearly with higher jee values, indicating diminishing marginal benefits at very high electricity prices. At the same time, higher purchase tariffs significantly reduce the SPB (e.g., from more than 80 years down to ~10 years at low jee). For NPV, higher export tariffs lead to a steeper slope in the NPV vs. jee relationship (Figure 13), implying that generous export compensation policies can still accelerate profitability, especially in energy-sharing contexts.

Figure 13.

Simple Payback (SPB) of the REC in the ES scenario under different cost of electricity (jee) and export tariffs (pee).

Figure 14.

Net present value (NPV) of the REC in the ES scenario under different cost of electricity (jee) and export tariffs (pee).

The influence of the variation of the cost of electricity on the EC in Quebec has shown that even a five-times increase does not lead to feasible EC solutions. The apparent insensitivity of the economic results to changes in pee arises from the imbalance between electricity imported and exported in the energy sharing (ES) configuration. The annual imported electricity amounts to 6,271,046.34 kWh, while only 643,057.55 kWh are exported. Consequently, the selling price of exported electricity influences only about 10% of the total grid-exchanged energy, leading to minimal variation in the overall annual cash flow. Even substantial changes in pee thus produce limited effects on the NPV and SPB, which remain dominated by investment costs and the purchase price of imported electricity. This explains the observed weak sensitivity of economic performance to pee in Figure 13 and Figure 14.

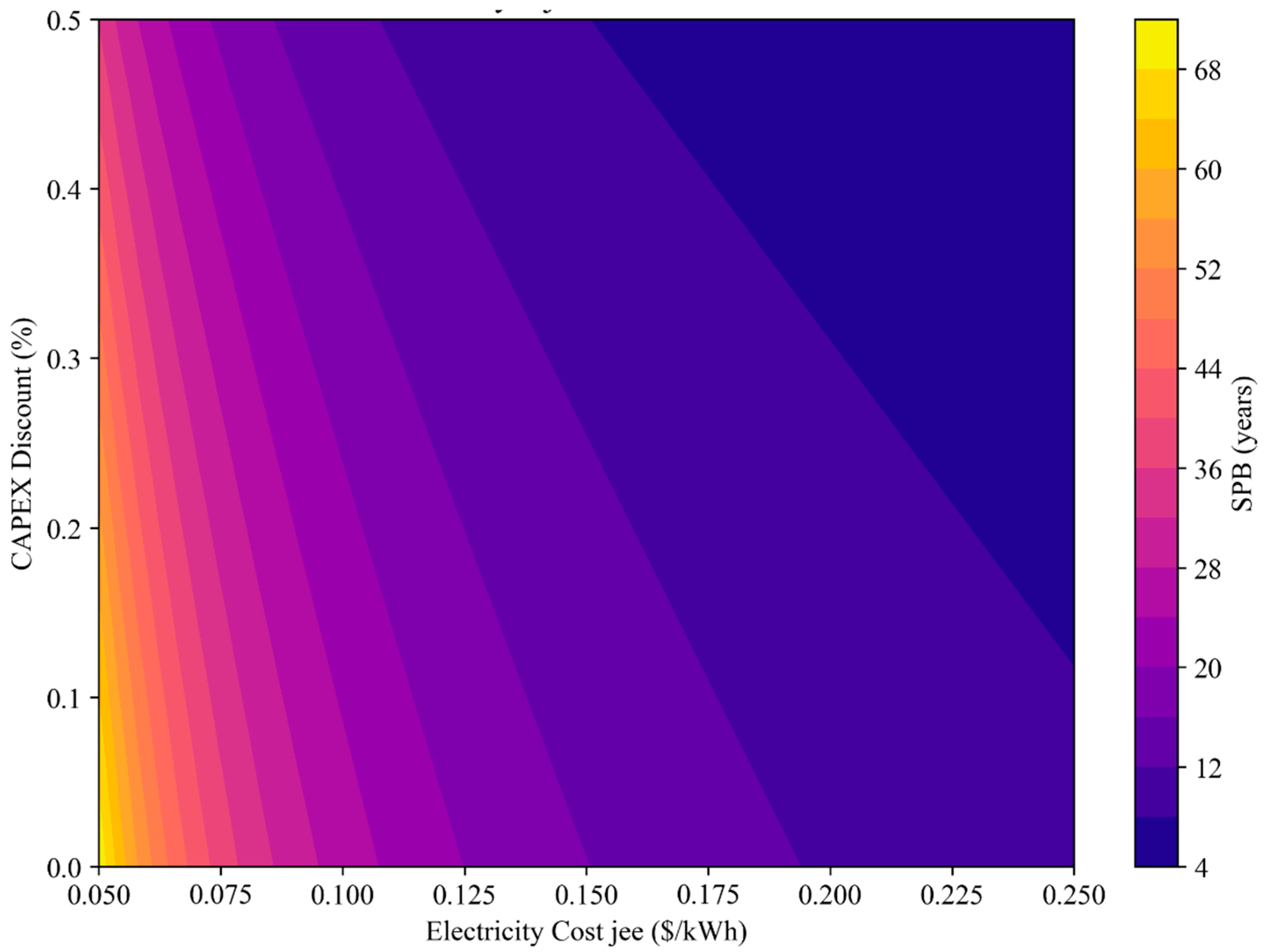

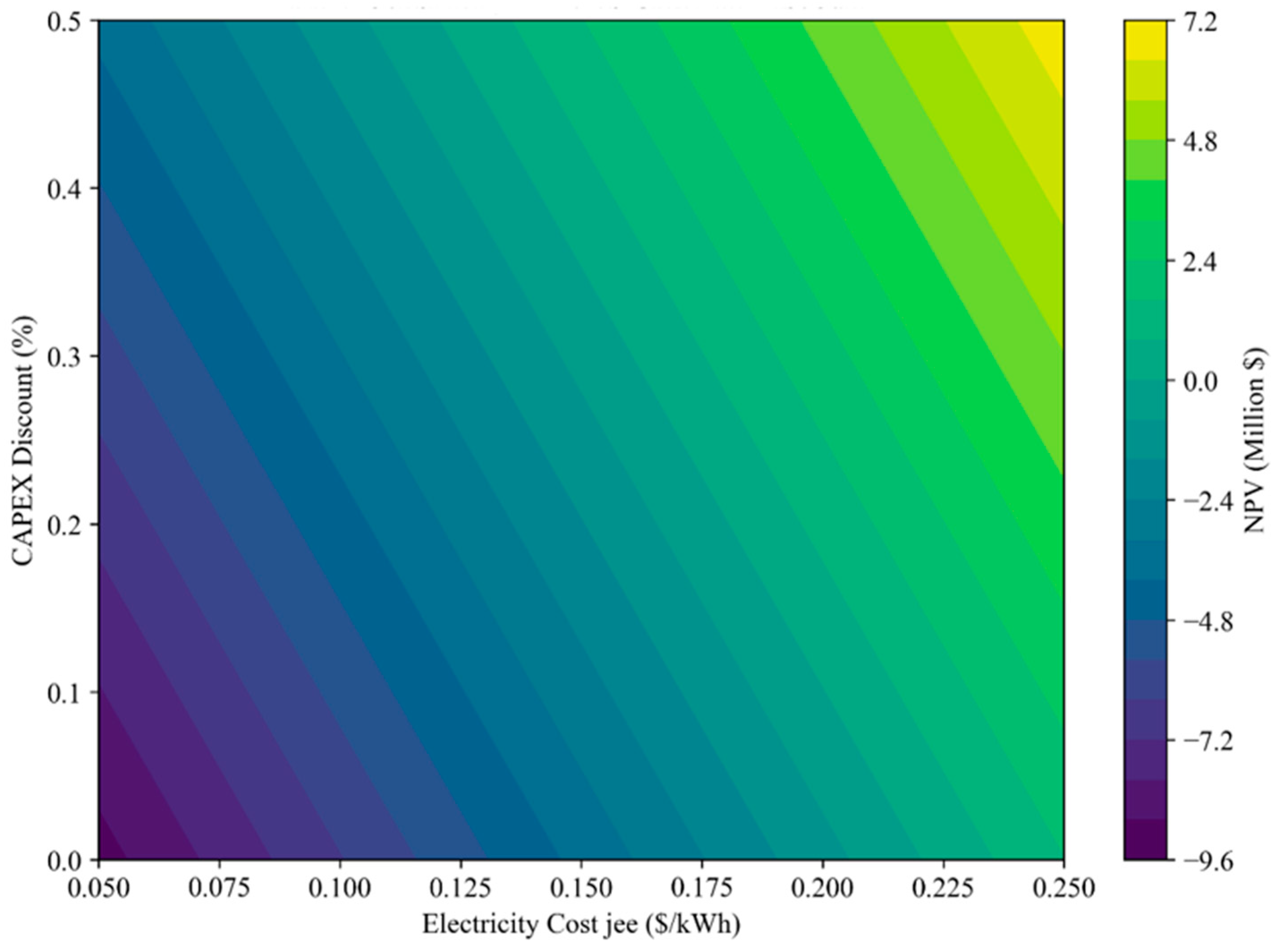

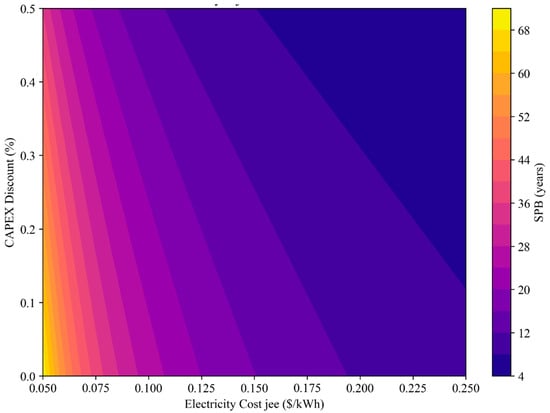

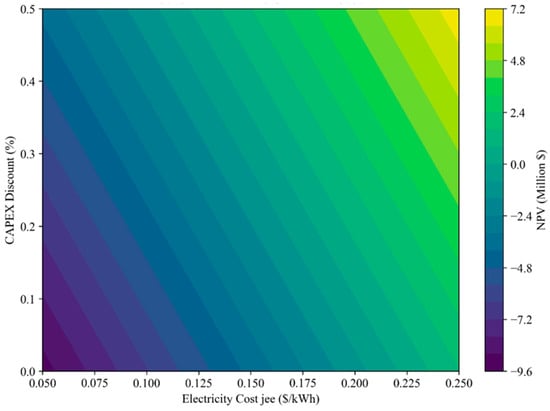

To further investigate the policy–market interplay, Figure 15 and Figure 16 display the combined impact of CAPEX discounts (ranging from 0 to 50%) and electricity costs (jee = 0.05–0.25 USD/kWh) on SPB and NPV.

Figure 15.

Contour plot SPB in the ES scenario under different cost of electricity (jee) and capex subsidies.

Figure 16.

Contour plot of NPV in the ES scenario under different cost of electricity (jee) and capex subsidies.

The SPB map (Figure 15) reveals that both increasing electricity prices and higher incentives contribute dramatically to shorter payback periods. For instance, an increase in jee from 0.05 to 0.15 USD/kWh with a CAPEX discount up to 30% can reduce SPB from over 40 years to below 10.

In Figure 15, NPV is shown to be highly sensitive to both parameters, with the break-even threshold (NPV = 0) crossed for several combinations of moderate CAPEX discount (≥20%) and jee above 0.16 USD/kWh.

This combined analysis suggests that targeted upfront subsidies or incentive schemes could significantly improve investment attractiveness, especially in areas with moderate retail electricity costs.

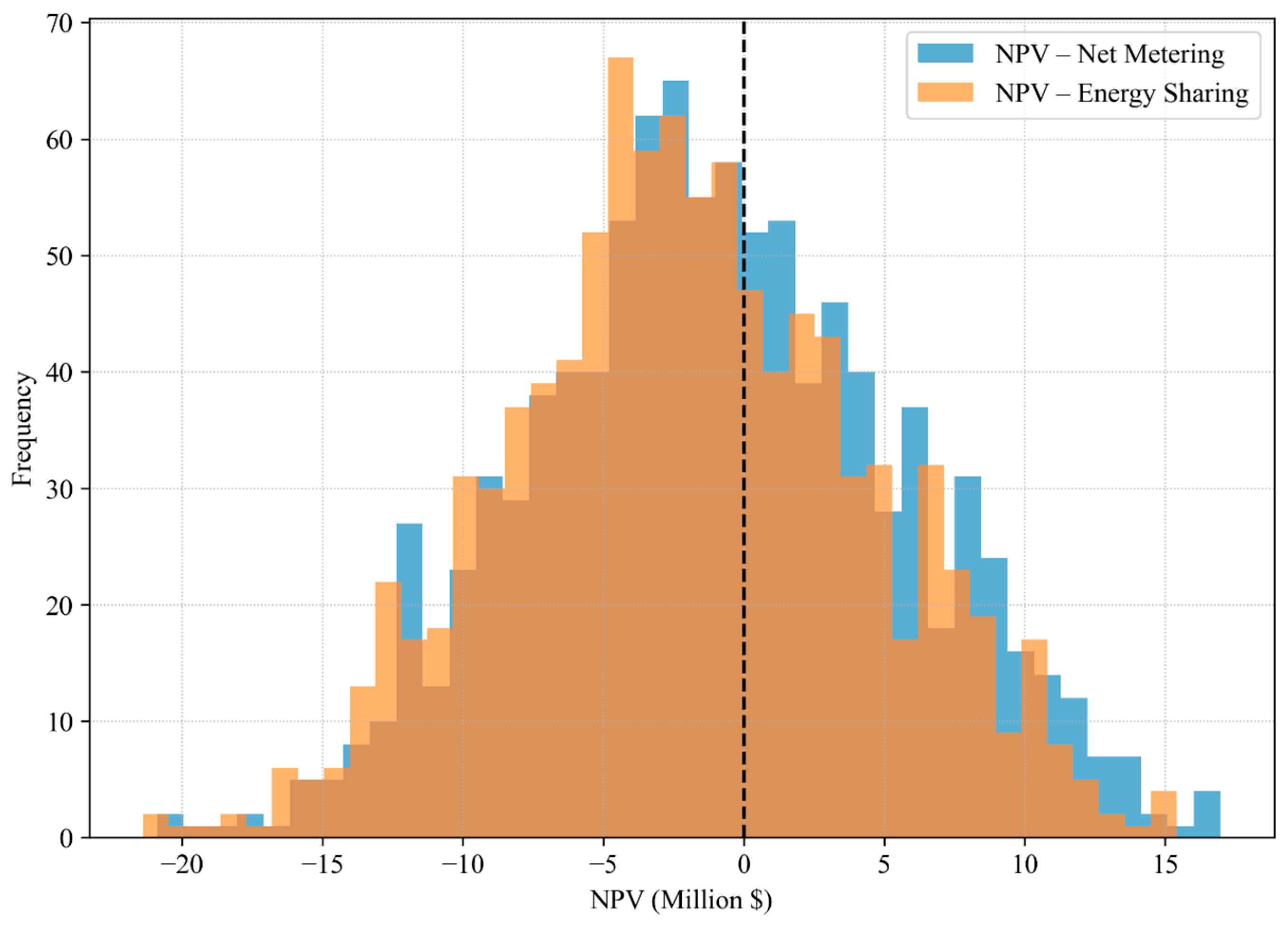

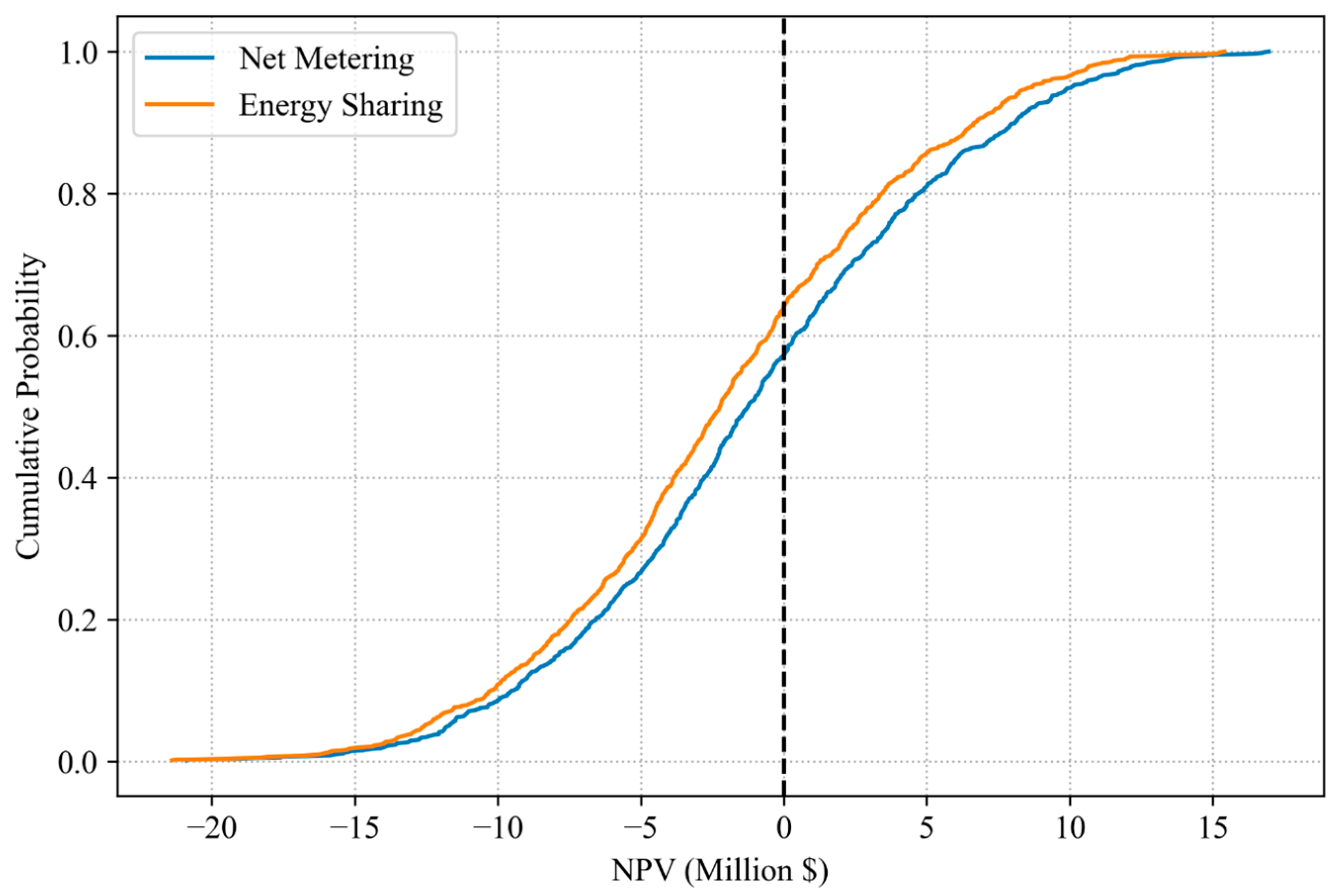

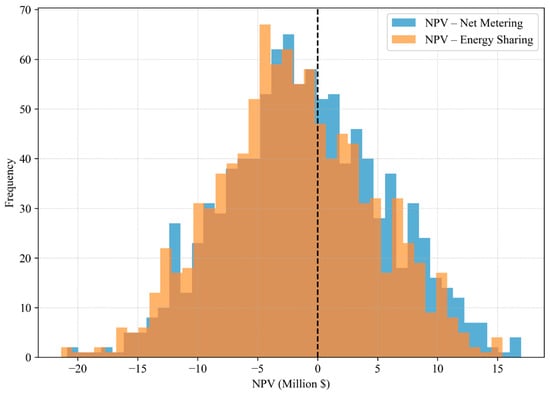

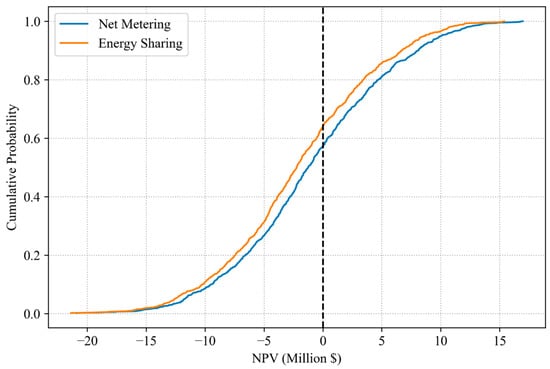

To evaluate the economic viability under uncertainty, a Monte Carlo analysis was also conducted (Figure 17 and Figure 18), where four uncertain variables were sampled over 1000 iterations for both net-metering and energy-sharing models. Electricity price (jee) was sampled from a uniform distribution between 0.05 and 0.25 USD/kWh, reflecting plausible variations in long-term energy costs. CAPEX discount was drawn from a uniform distribution between 0% and 50%, simulating a wide range of possible financial incentives or investment cost reductions. Export price (pee) was modelled indirectly by sampling a ratio to jee from a uniform distribution between 1/6 and 1/2, representing typical export tariff structures. Maintenance cost was assumed to grow from 1% of CAPEX (i.e., ~USD 107 k/year) up to 5%, capturing operational cost variability.

Figure 17.

Monte Carlo histogram for NM and ES scenarios.

Figure 18.

Cumulative distribution function under different conditions for both NM and ES scenarios.

The NPV histogram (Figure 17) reveals that NM yields a wider and slightly right-shifted distribution with respect to the zero-point, with more frequent occurrences of higher NPV values, especially in the range between 5 and 15 million USD. In contrast, ES produces a narrower and more symmetric distribution, with a higher concentration of values around the zero-point (NPV = 0). The left tail of NM also extends more deeply into negative territory, indicating a greater downside risk, whereas ES outcomes tend to cluster closer to zero, showing slightly more predictable results.

The cumulative distribution function (CDF) in Figure 18 confirms this observation: at the NPV = 0 threshold, about 65% of ES simulations achieve profitability, compared to roughly 45% for NM. While NM may offer higher upside potential, ES exhibits lower variance, as evidenced by the steeper slope of its CDF curve, and thus higher reliability—an important advantage under uncertain economic and policy conditions.

The trade-off highlighted by the Monte Carlo analysis underscores a classical risk–return dilemma: NM appeals to risk-seeking investors, offering potentially higher returns but with greater exposure to adverse scenarios, especially in cases of low electricity prices, high maintenance costs, or unfavorable export tariffs; ES, in contrast, is more suited to risk-averse stakeholders, such as municipalities, cooperatives, or social housing providers, who value resilience and financial stability over maximal profit. Its performance is less sensitive to extreme parameter values, making it better aligned with long-term planning and community goals.

Moreover, in policy environments that reward local consumption, peer-to-peer energy models, or grid-friendly behaviors, the ES model may unlock non-monetary benefits, such as improved grid stability or social equity—which are not captured in NPV alone but increase its societal value proposition.

6. Conclusions

This study proposed a comparative techno-economic analysis for a renewable energy community (REC) operating under two different sharing mechanisms: energy sharing (ES) and net metering (NM). The simulation of the demand profiles for the prosumers of the REC was carried out by means of an urban simulation platform Tools4Cities developed at the Next Generation Cities Institute (NGCI) of Concordia University of Montreal. This simulation hub allows for a holistic simulation approach for buildings in cities, paving the way for the future of large-scale simulation of urban energy retrofit actions. Despite the promising findings, the study is constrained by some assumptions, including the use of archetype-based building profiles, lack of detailed measured energy consumption data, and simplified economic parameters, which may introduce uncertainties when applying the results to specific real-world communities. The main results of the study are as follows:

- ES outperforms NM across all technical KPIs. Specifically, Self-Consumption Ratio (SCR) improved from 66% (NM) to 77% (ES), and Self-Sufficiency Ratio (SSR) increased from 35% to 40%. ES achieved these gains by redistributing surplus PV generation among buildings with deficits, enabling more balanced local energy use. Hence, integrating photovoltaic systems on commercial/institutional vast rooftops within the district significantly enhanced overall self-sufficiency, demonstrating that leveraging large, underutilized roof areas in non-residential buildings can play a pivotal role in reducing grid dependency and supporting local energy resilience.

- A seasonal peak analysis showed that ES delivers up to a 30% reduction in summer afternoon peaks (2–6 p.m., July–August), while winter evening peaks (5–8 p.m.) remain largely unaffected due to low solar availability.

- Under current electricity tariffs and capital costs, both mechanisms exhibit negative net present values (NPVs): −USD 8.6 M for ES and −USD 8.2 M for NM, with NM showing slightly better financial performance due to grid credits. However, sensitivity analyses demonstrate that CAPEX subsidies of 40–50% or modest feed-in tariffs can substantially improve investment viability, turning NPVs positive under several scenarios.

- The PV simulation outputs were validated against TRNSYS models for PV production, confirming consistency in seasonal trends and total energy output. The building demand profiles are based on Energy Plus, a widely accepted simulation engine with extensive literature support, lending intrinsic credibility to the modeled loads.

Overall, both ES and NM contribute significantly to decentralization and resilience in urban energy systems. Despite current economic hurdles, their technical benefits justify continued development, particularly if accompanied by enabling policies. With CAPEX subsidies, regulatory innovation, and integration of storage or dynamic pricing schemes, RECs can become a key component of Canada’s sustainable urban energy strategy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K.F., S.R., L.C., F.V., C.H.-V., U.E. and F.C.; Methodology, A.K.F., S.R., L.C., F.V., C.H.-V. and U.E.; Software, A.K.F., S.R., L.C. and F.V.; Validation, A.K.F., L.C., C.H.-V. and F.C.; Formal analysis, A.K.F., F.V., C.H.-V., U.E. and F.C.; Investigation, A.K.F. and U.E.; Resources, C.H.-V.; Data curation, A.K.F., S.R. and U.E.; Writing—original draft, A.K.F., S.R., L.C. and F.V.; Writing—review and editing, A.K.F., L.C., F.V. and U.E.; Visualization, F.C.; Supervision, C.H.-V. and F.C.; Project administration, C.H.-V. and U.E.; Funding acquisition, U.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was developed within the International Community Energy Living Labs project of the Volt-Age research program. The authors also acknowledge funding support for the Ph.D. students from the Canada Excellence Research Chairs Program with grant number CERC-2018-00005, and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada-NSERC Discovery Grant-EG-1512.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kiashke Zaaging Anishinaabek First Nations community.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- European Commission. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council Amending Directive (EU) 2018/2001. COM(2022) 222 Final, Vol. 2022/0160. 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021PC0557 (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Krug, M.; Alonso, I.; Anfinson, K.; Azevedo, I.; Del Bufalo, N.; Di Nucci, M.R.; Dyląg, A.; Gatta, V.; Massa, G.; Meynaerts, E.; et al. Comparative Assessment of Enabling Frameworks for RECs and Support Scheme Designs; COME-RES: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Koirala, B.P.; Koliou, E.; Friege, J.; Hakvoort, R.A.; Herder, P.M. Energetic communities for community energy: A review of key issues and trends shaping integrated community energy systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 56, 722–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchi, F.; Stasi, R.; Berardi, U. Modelling tools for the assessment of Renewable Energy Communities. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 3941–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inês, C.; Guilherme, P.L.; Esther, M.G.; Swantje, G.; Stephen, H.; Lars, H. Regulatory challenges and opportunities for collective renewable energy prosumers in the EU. Energy Policy 2020, 138, 111212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minuto, F.D.; Lanzini, A. Energy-sharing mechanisms for energy community members under different asset ownership schemes and user demand profiles. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Anapyanova, A.; Vandenriessche, F.; de Meer, H. Implementing energy sharing in energy communities: A comparative legal analysis of Austria and Flanders. Util. Policy 2025, 96, 101993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, D.F.; Dias, B.H.; de Oliveira, L.W.; Soares, T.A.; Rezende, I.; Sousa, T. Innovative business models as drivers for prosumers integration—Enablers and barriers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 144, 111057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwo, E.O.; Tozer, L. Community energy justice: A review of origins, convergence, and a research agenda. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2025, 123, 104036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]