Abstract

Axial Flux Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor (AFPMSM) offers high power density in structures with short axial lengths and large radial dimensions, making it attractive for applications that require thin structures, such as in-wheel motors. This study proposes an AFPMSM design process applicable under fixed inner/outer diameter and axial length constraints. The proposed process is presented as step-by-step procedures: selection of pole/slot combinations, adjustment of slot depth, determination of stator/rotor dimensional ratios, and slot structure design. It is universally applicable to both bobbin-type rectangular wire windings and shoe-type round wire windings. The validity of the proposed process was verified through finite element method (FEM) analysis, and the differences between the two winding structures were examined through post-processing of the results. By presenting an AFPMSM design methodology that can be consistently applied under constrained spatial conditions, this study provides practical design guidelines for the development of in-wheel motors for next-generation mobility applications.

1. Introduction

The demand for the Autonomous Mobile Robot (AMR) is increasing with the recent spread of logistics automation and smart manufacturing environments [1]. Consequently, there is a growing need for compact drive systems with high efficiency and high power density. Since the AMR requires batteries, controllers, sensors, and drive systems to be concentrated within a limited platform, achieving high power density in the drive motor is essential [2]. In particular, the in-wheel structure, in which the motor is directly integrated within the wheel, enables direct drive without a separate transmission system. This offers advantages in terms of internal space utilization for the AMR and can also contribute to weight reduction and improved reliability through modularization and a reduction in components [2].

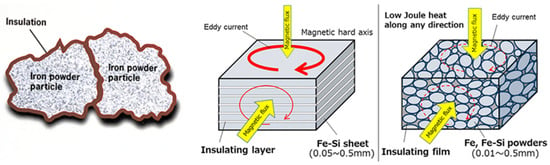

To meet these requirements, the AFPMSM offers high power density with a structure characterized by short axial length and large radial dimension, leveraging its structural advantages [3]. Compared with the conventional Radial Flux Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor (RFPMSM), this makes the AFPMSM suitable for applications with installation spaces like in-wheel motors [3]. The AFPMSM is classified into core-type and coreless-type based on the presence or absence of a core. The coreless type minimizes iron core usage, reducing cogging torque, but suffers from performance degradation due to unfocused magnetic flux and increased magnetic resistance [4]. In contrast, the core type enables magnetic flux concentration, allowing for relatively higher output. In industrial applications, the core-type AFPMSM is more commonly adopted. Manufacturing methods for the core-type AFPMSM core include tape-wound cores using electrical steel sheets and Soft Magnetic Composite (SMC) cores.

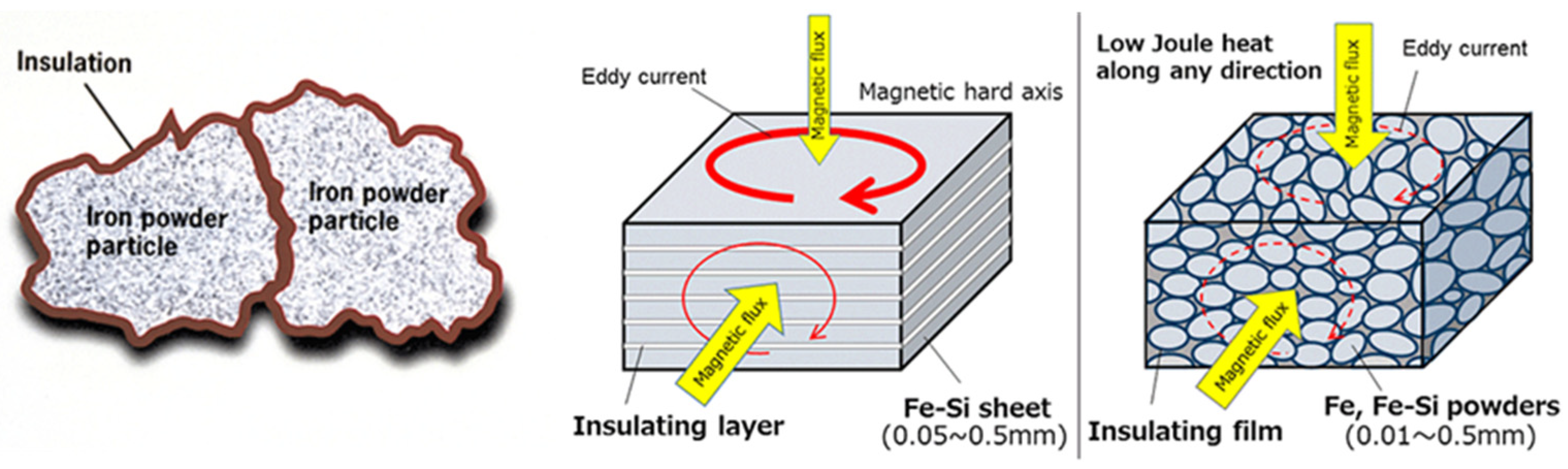

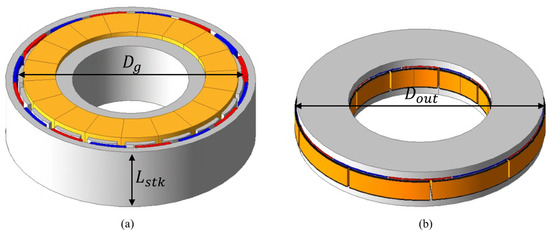

When using electrical steel, the laminations must be stacked perpendicular to the magnetic flux direction, as shown in Figure 1. This necessitates the use of a tape-wound core in the AFPMSM. The tape-wound core made from electrical steel offers great magnetic performance and is the most widely used, but it involves complex manufacturing processes and structural limitations [4,5]. A key constraint is that the outer and inner diameters of the stator core tooth must match those of the stator back yoke. This inevitably results in the end turns of the windings protruding outward [6]. Therefore, the outer diameter, inner diameter, and end-turn shape must be comprehensively considered during design, acting as critical variables.

Figure 1.

Difference between electrical steel sheet core and SMC cores.

Thus, in designing an AFPMSM for in-wheel motor applications, constraints such as limited space, high power density requirements, end-turn shape limitations, and manufacturing challenges must be considered simultaneously. This necessitates a process adapted to both the winding structure and the core geometry.

Accordingly, this paper proposes a design process applicable to both bobbin-type rectangular wire windings and shoe-type round wire windings for a core-type AFPMSM using laminated steel sheets as the core. The structural and electromagnetic characteristics of each winding method were quantitatively analyzed through FEM-based simulation. Although the proposed process follows standard electromagnetic design principles, AFPMSM has unique geometric constraints caused by end-turns extending toward both the inner and outer diameters. To address these limitations, the design variables were redefined so that the process could be conducted under fixed outer/inner diameter and axial length conditions. The proposed process is not an optimization algorithm, but a sizing process conducted under fixed outer/inner diameters, axial length, and current density constraints, aiming to maximize the achievable output within these limitations. Key performance metrics, including output, efficiency, and torque ripple, were compared and evaluated under identical external constraint conditions. The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 1 provides an overview of the AFPMSM and its potential application as an in-wheel motor. Section 2 details the characteristics of the stator structure and winding configuration for both winding methods. Section 3 presents a step-by-step design process applicable to both structures and explains key design variables and calculation formulas. Section 4 presents the further design of the resulting model derived based on the proposed design process, and finally, Section 5 presents the conclusions of this study.

2. Characteristics of Stator Structure and Winding Methods

The stator structure design of the AFPMSM critically influences not only the electromagnetic and thermal characteristics of the drive system but also its manufacturing feasibility and reliability. Among these, the core shape and winding configuration act as key variables directly affecting power density and design flexibility. These design variables become particularly critical in applications such as in-wheel motors, where the drive system is modularized and simultaneously demands high power density and high efficiency within a confined space. Therefore, to derive a stator structure that aligns with the intended application of the AFPMSM, it is essential to accurately understand the characteristics of each structure, the interactions between winding methods, and to integrate the resulting constraints from the earliest design stages.

2.1. Wire Shape: Round Wire and Rectangular Wire

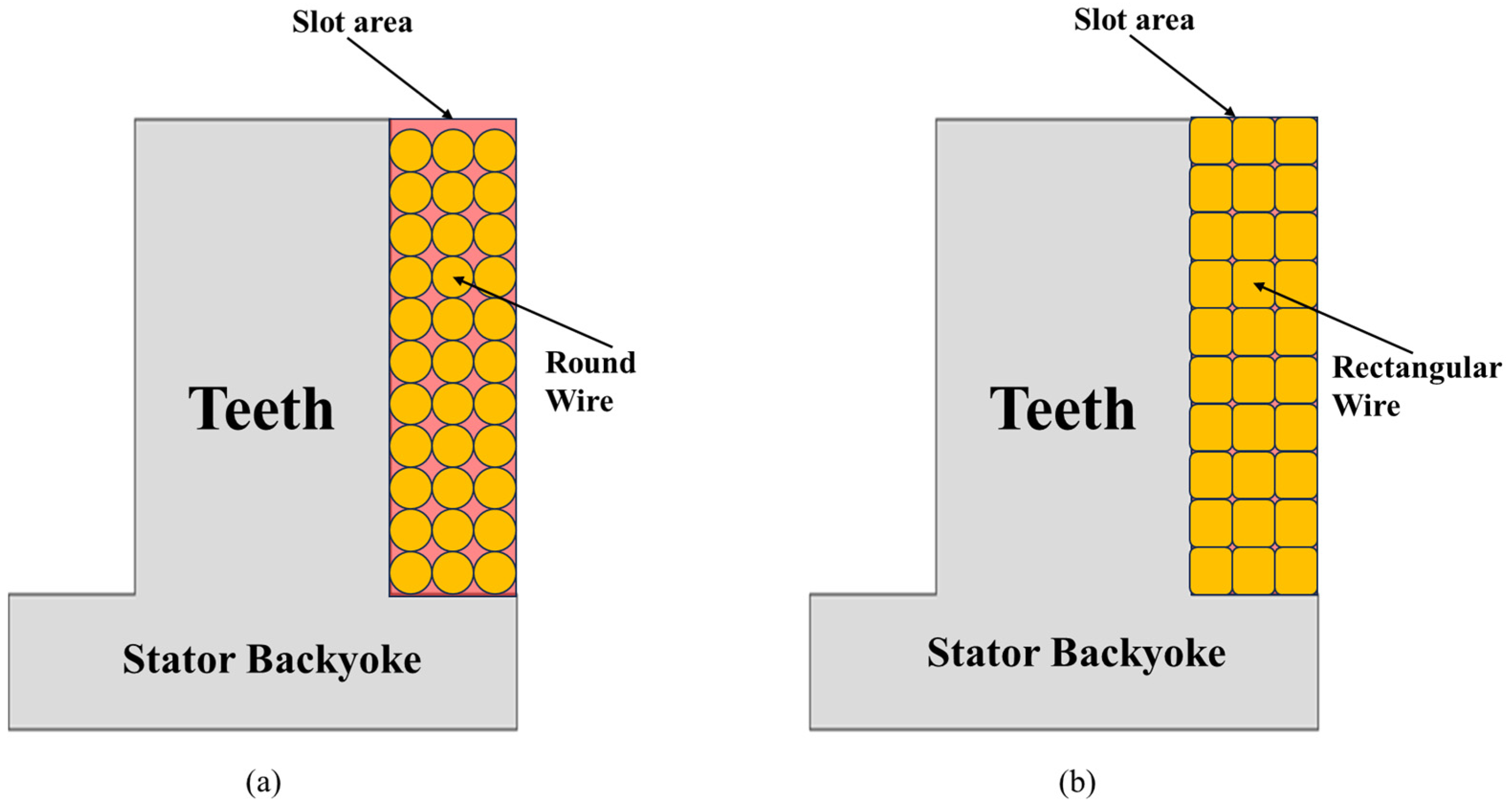

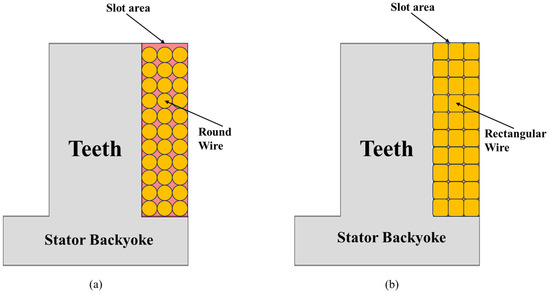

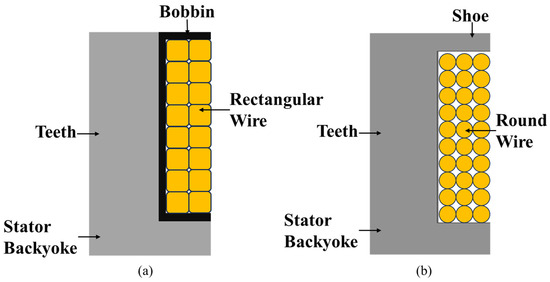

The conductors used in AFPMSM windings are broadly categorized into round wire and rectangular wire. While both types share identical electrical characteristics, their differing external geometries result in distinct structural suitability and manufacturing process characteristics. Round wire, a standard circular copper conductor, offers greater flexibility compared with rectangular wire [7]. This makes it advantageous for direct winding into stator slots in the AFPMSM, like the practice in RFPMSM.

As shown in Figure 2, rectangular wire can achieve a higher fill factor within the same slot area [8]. This advantage is particularly beneficial when using stator cores without shoes, where performance degradation is a concern. The higher fill factor enables a larger effective cross-sectional area compared with round wire, thereby facilitating the achievement of target performance [8]. Therefore, the selection of the winding configuration must be considered holistically in conjunction with the structural characteristics of the stator and the winding arrangement method.

Figure 2.

Types of wires for the AFPMSM: (a) Round wire; (b) Rectangular wire.

2.2. Wire Methods: Direct Winding and Bobbin Insertion

The conductors described above can be applied using two winding methods, depending on how they are wound onto the stator. The first method involves directly winding the conductor into the stator slots, whereas the second involves pre-winding the conductor onto a plastic bobbin, inserting it into the slot, and then completing the connections. The direct winding method is generally applied to structures with shoes. While it offers the advantage of ensuring electromagnetic performance through slot opening adjustment, it has the disadvantage that, because the thicknesses of the inner and outer sides of the stator tooth differ in the AFPMSM compared with the RFPMSM, the winding machine must operate with relatively complex movements, making the application of mechanical winding difficult [9,10]. The bobbin insertion method involves inserting prefabricated windings with bobbins into the stator slots. While it offers superior productivity, this method can only be applied to structures without shoes [11]. However, structures without shoes suffer from issues such as magnetic flux leakage and a reduced flux concentration ratio, resulting in relatively lower performance compared with structures with shoes [12].

2.3. Application and Selection Criteria for Winding Methods by Structure

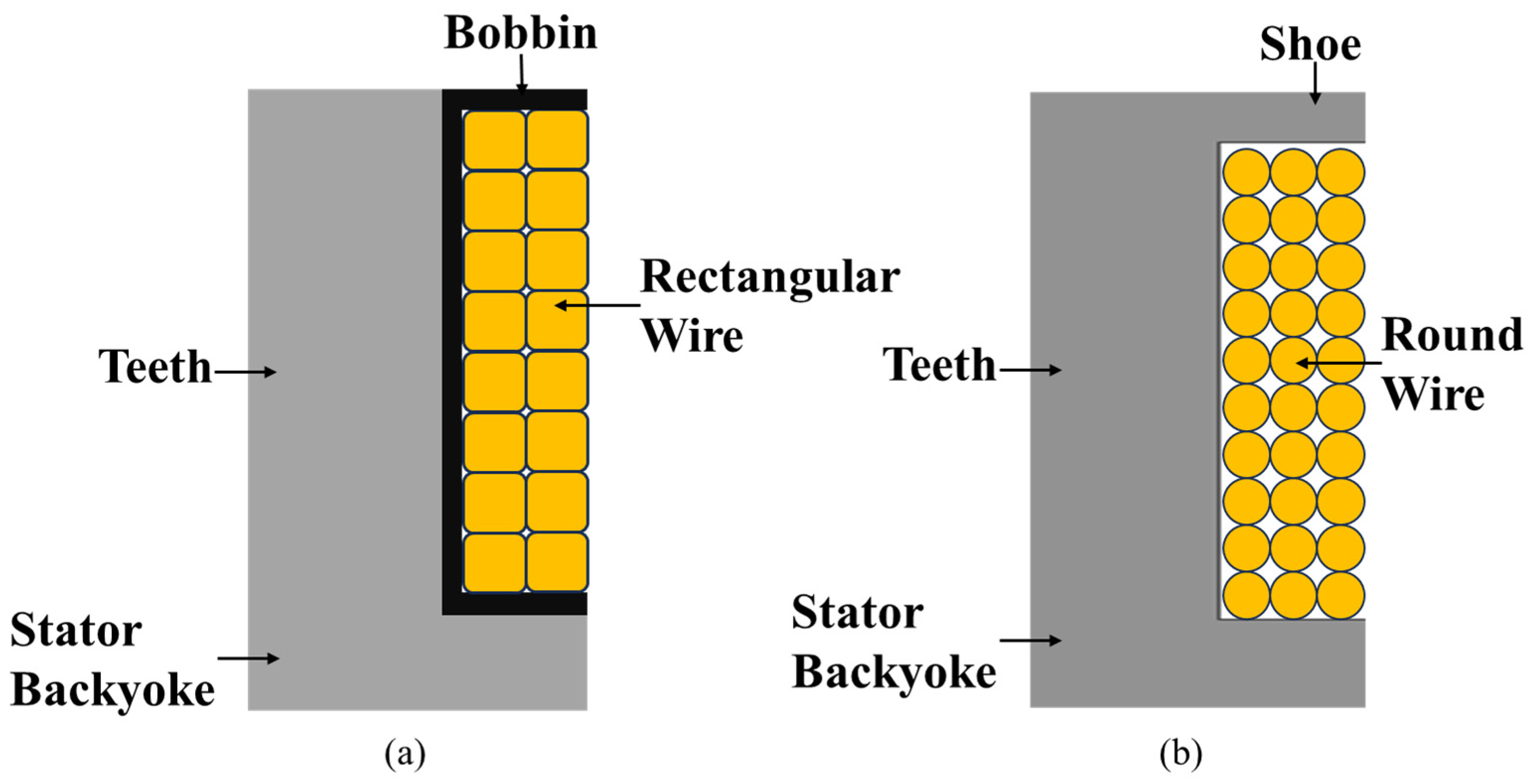

For the reasons described above, it is essential for designers to comprehensively consider the characteristics of AFPMSM winding shapes and methods to select the most suitable combination according to the stator structure. Based on this consideration, this paper adopts the direct winding method with round wire for structures with shoes, and the bobbin insertion method with rectangular wire for structures without shoes.

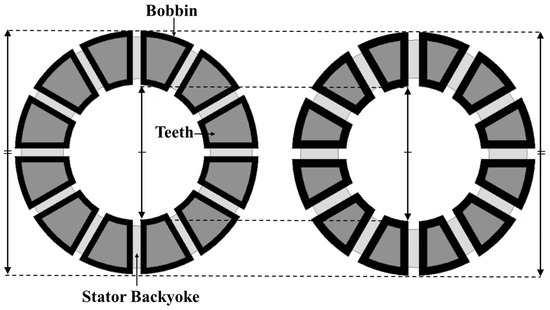

Figure 3 shows the cross-sectional areas of the two selected stator structures. This is not intended as a direct performance comparison between the two structures but rather establishes a foundation to examine whether a common design process can be effectively applied when the appropriate winding method for each structure is applied under identical constraints. The next chapter proposes a step-by-step design procedure applicable to both structures and explains the key design variables and calculation formulas to be considered during this process.

Figure 3.

Selected stator types: (a) Bobbin-rectangular wire type without shoes; (b) Direct-round wire type with shoes.

3. Unified Design Procedure for the AFPMSM Reflecting Constraints

The in-wheel motor for the AMR has its entire drive system housed within the wheel, which restricts dimensional changes during design. The motor’s outer and inner diameters must be fixed to match the wheel structure and the internal drive system. This means that the outer and inner diameters of the end turns must also remain fixed in the AFPMSM design.

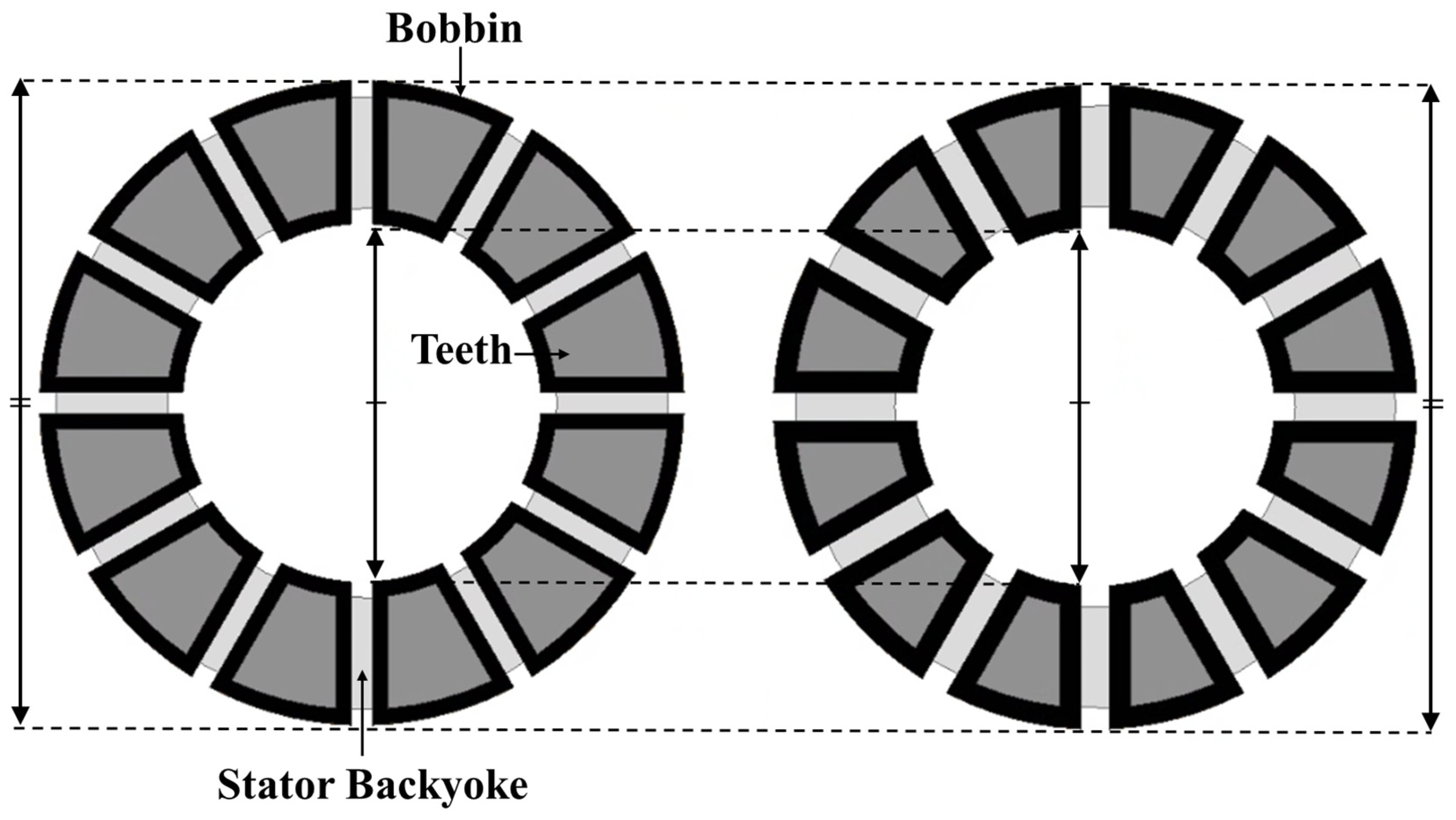

Figure 4 illustrates the primary design constraints. Under these conditions, even when adjusting performance by modifying the stator shape, the outer and inner diameters must remain fixed, which significantly restricts design flexibility. Consequently, even when adjusting the stator core’s pitch width, pitch length, or back-yoke thickness, the design flexibility for winding placement and shape modification becomes restricted, creating significant design challenges. Therefore, when designing an AFPMSM for in-wheel motor applications, a design procedure is required that achieves the target performance while keeping the outer and inner diameters fixed with consideration of the end turns, as well as maintaining a fixed axial length.

Figure 4.

Fixed outer and inner diameters during core shape modification.

To examine a design process that can be consistently applied while satisfying these constraints, this study focuses on the shoe-type round wire structure, as described in Section 2, and the bobbin-type rectangular wire structure without shoes. Although the two structures differ in wire arrangement and winding shape, a unified design procedure can be applied under identical external constraints. Therefore, this chapter aims to define a unified design procedure that can be applied while satisfying the same external constraints, despite targeting different structures, and to establish a design flow based on this.

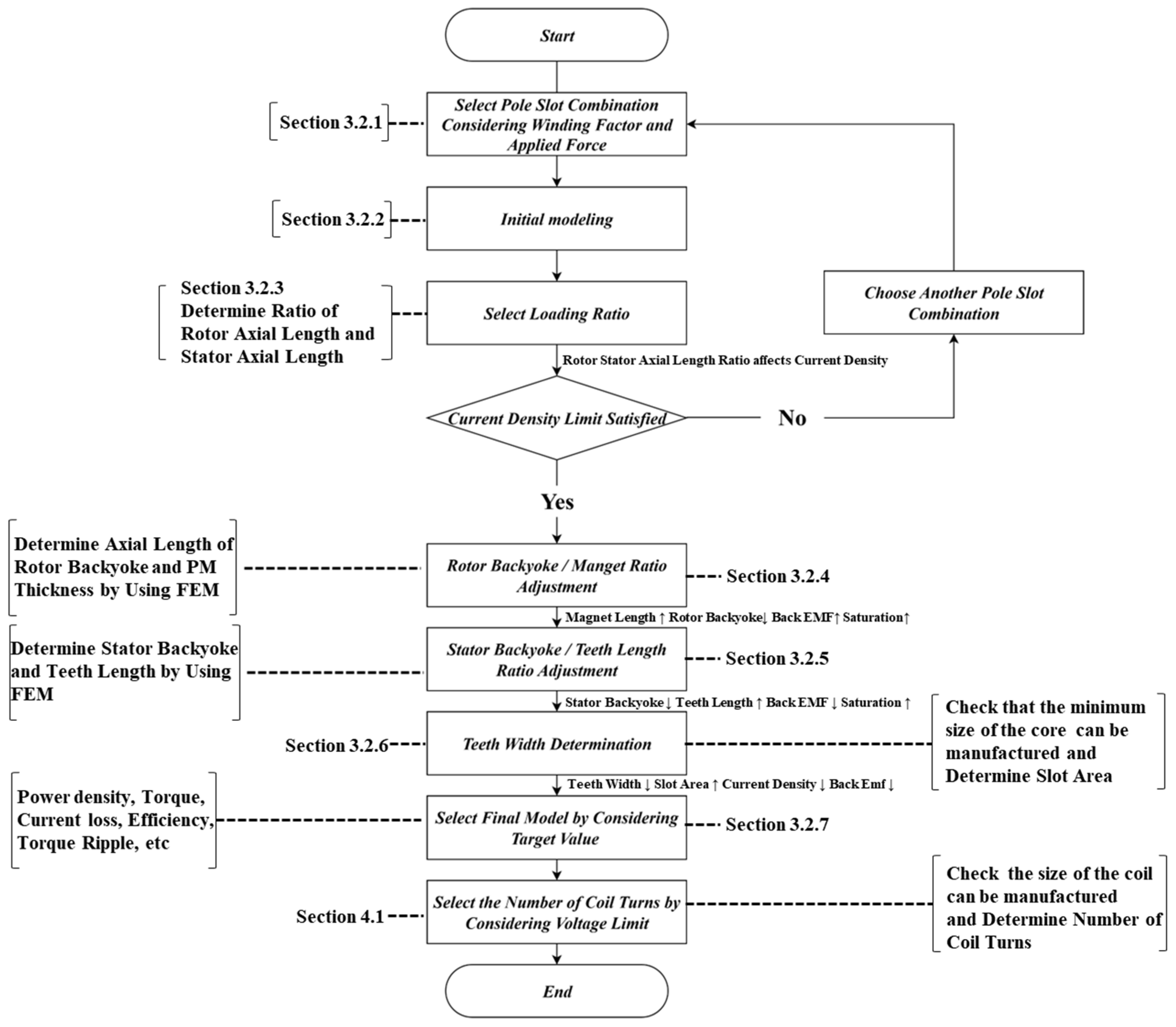

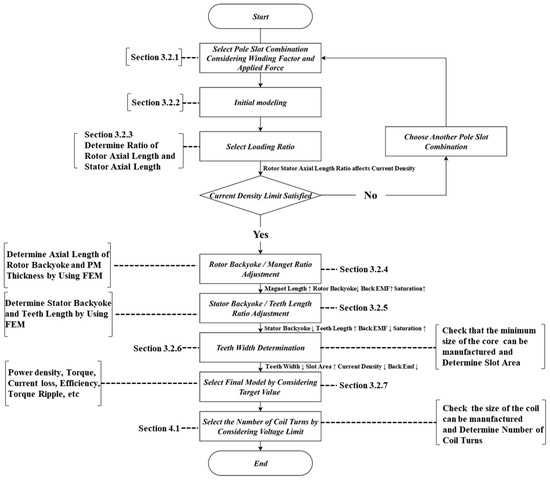

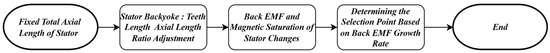

3.1. Flow of the AFPMSM Design Procedure

Table 1 presents the definitions of the variables used in Section 3.1, and Figure 5 illustrates the AFPMSM design process. The design flow in Fig. 5 was organized to clarify the interdependence among design variables, showing how each step influences the subsequent one. The process begins with the selection of the pole–slot combination. Since the pole–slot combination influences the motor’s electromagnetic performance, control characteristics, and vibration characteristics, an appropriate combination must be selected based on the intended application. The first factor to consider when selecting a pole–slot combination is the winding factor . The winding factor represents the reduction in the magnetomotive force (MMF) induced in the motor due to the distribution and short-pitching of the windings. It is expressed as the product of the distribution factor and the pitch factor . The distribution factor represents the ratio of the MMF produced by a distributed winding to that of a concentrated winding. When the winding forming one phase is distributed across slots, the MMF induced in each slot decreases to approximately of that in the concentrated winding. However, these MMFs have phase differences and combine, resulting in a composite MMF waveform that more closely approximates a sine wave. The ratio of the resultant MMF of the distributed winding to the maximum MMF of the concentrated winding is defined as the distribution factor. The pitch factor represents the reduction in MMF of a short-pitched winding relative to that of a full-pitched winding.

Table 1.

Definition of terms of mathematical derivation.

Figure 5.

Unified design process of the AFPMSM with constraints applied.

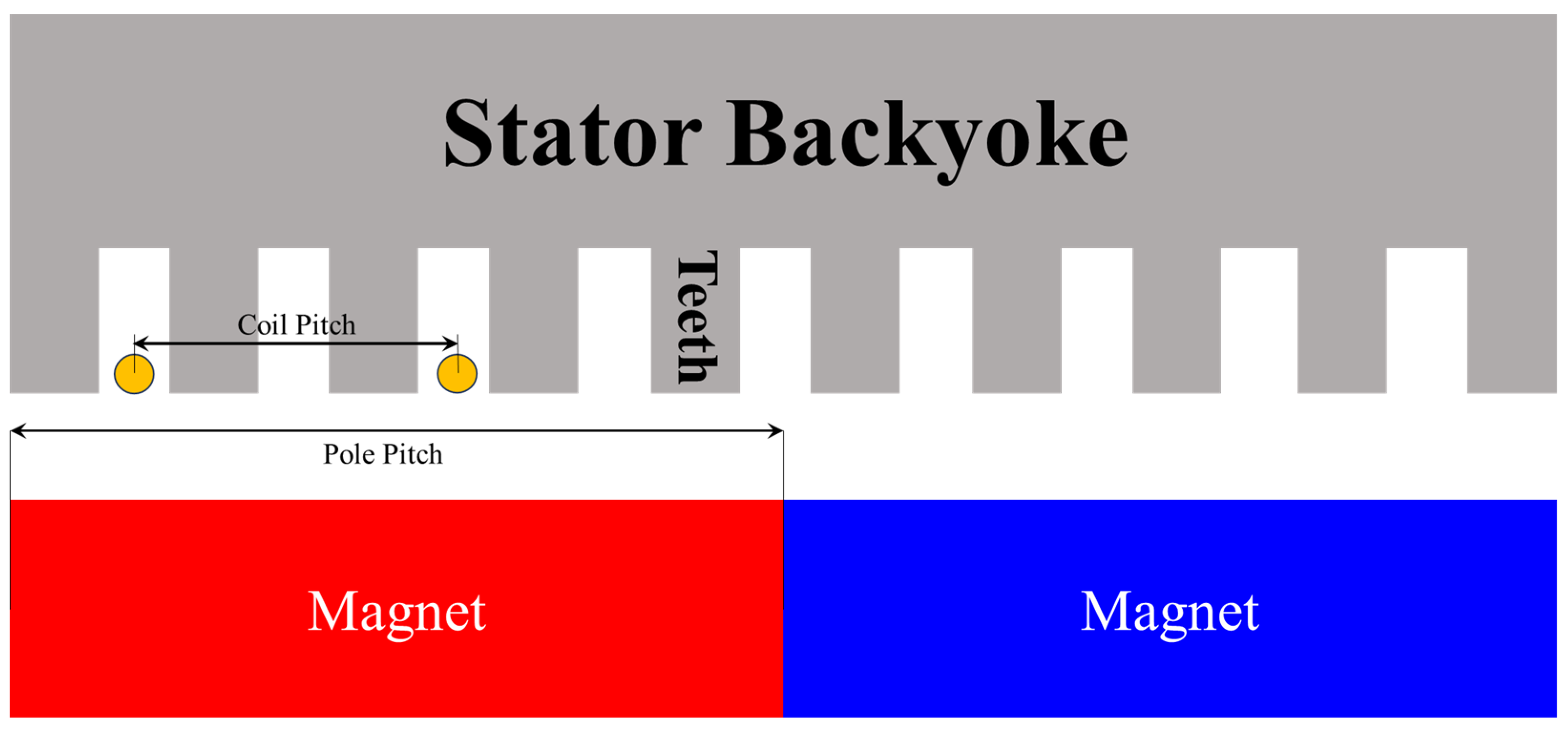

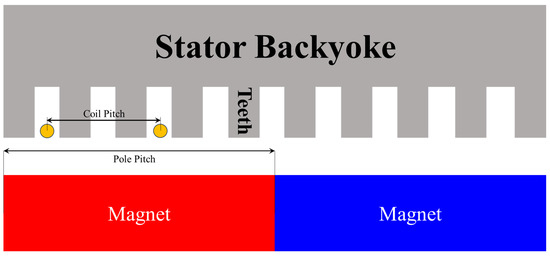

A full-pitch winding refers to the case where the pole pitch and coil pitch are equal, maximizing the resultant magnetomotive force (MMF). A short-pitch winding refers to the case where the coil pitch is smaller than the pole pitch, as shown in Figure 6, resulting in a reduced MMF compared with a full-pitch winding. Consequently, the winding factor quantifies the overall impact on motor performance when both distributed and short-pitched windings are employed, directly relating to the electromagnetic output. Therefore, selecting pole–slot combinations that yield the highest possible winding factor is essential for applications requiring high output.

Figure 6.

The pole pitch and coil pitch applied in short-pitched windings.

Additionally, the lowest-order radial force harmonic is also a critical consideration when selecting pole–slot combinations. Since the lowest spatial harmonic corresponding to the greatest common divisor (GCD) of the number of slots and the number of poles P contributes most significantly to stator vibration, it is recommended to select the pole–slot combination with the largest possible GCD for vibration and noise reduction [13]. Finally, when selecting pole–slot combinations, using a higher pole number reduces the magnetic flux per pole, allowing for a thinner rotor back-yoke. However, when the motor’s mechanical speed [rpm] is fixed, the electrical frequency is given by

Therefore, increasing the number of poles proportionally increases the electrical frequency . Consequently, although using more poles is generally advantageous, the increase in also increases the iron loss

Thus, motor efficiency and output performance deteriorate. Furthermore, as the electrical frequency increases, the inverter’s switching frequency must also increase, leading to higher switching losses and electromagnetic interference (EMI). This raises the performance requirements of the inverter and increases the controller cost. Therefore, the number of poles must be selected by comprehensively considering the combined effects of this electrical frequency increase.

After completing the selection of the pole–slot combination, the basic geometry must be determined to proceed with the design. Owing to the nature of in-wheel motors, where the drive system is integrated inside the wheel, geometric constraints such as the motor’s outer diameter, inner diameter, and axial length must be clearly defined at the initial design stage, taking into account components such as the reducer and control module to be housed internally. To begin with, the thickness of the rotor permanent magnets must be specified in accordance with the minimum manufacturing requirements. In addition, when the shoe-type stator winding method is adopted, the slot opening size must be secured to a sufficient level to accommodate this. Finally, magnetic saturation must be evaluated under the established geometric constraints using the selected pole–slot combination. This prevents nonlinear effects caused by magnetic saturation in the stator and rotor back yoke and tooth and facilitates parameter adjustments during subsequent design iterations.

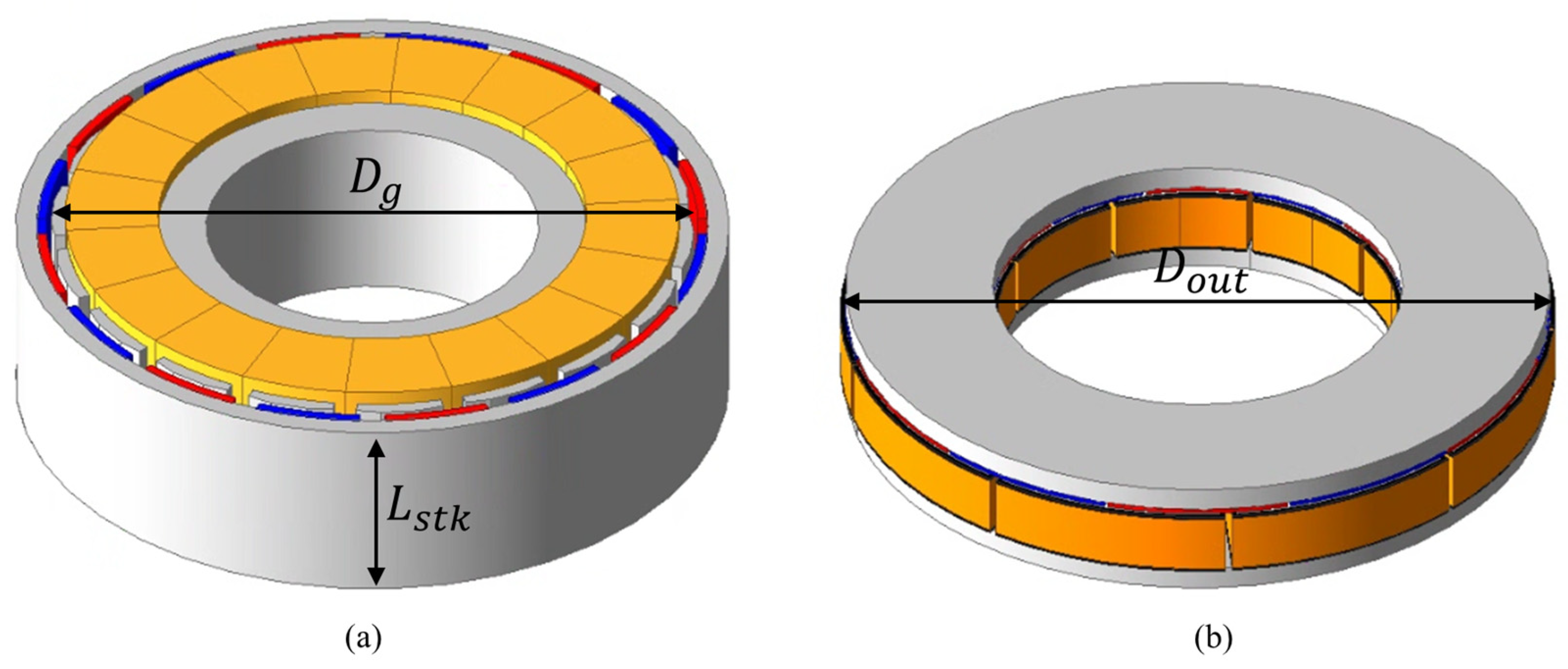

After the basic geometry of the model is finalized, the ratio of electric loading to magnetic loading—that is, the distribution ratio of the axial dimensions—is determined to define the ratio of rotor axial thickness to stator axial thickness when the total axial length is fixed. To illustrate this process, the case of the RFPMSM is first explained. The air-gap flux per pole in an RFPMSM is given as

as expressed in (3), and the flux linkage produced by the total permanent magnets is

This can be expressed by (4). The magnetomotive force (MMF) in one phase is

Since the electromagnetic torque of the RFPMSM can be expressed as

where denotes the specific electric loading, defined as the total electric loading divided by the air-gap circumference, and is associated with the specific magnetic loading, it follows that the electromagnetic torque of the RFPMSM can be adjusted through both electric and magnetic loadings. At this stage, the electric and magnetic loadings are given, respectively, as

To convert the above relationship for the RFPMSM to the AFPMSM, the expressions for electric and magnetic loadings must be modified to account for the geometric differences between the two topologies. Accordingly, the electric and magnetic loadings are expressed as

The air-gap flux in an AFPMSM is given as

is ratio coefficient of the maximum and average values of the magnetic flux density. If you express the force acting in the direction of Equation (9) in amperes, it’s like Equation (10)

Integrating Equation (10) is as follows.

Equation (11) indicates that the torque, i.e., the output operating point, can be determined by appropriately adjusting the electric and magnetic loadings.

Figure 7 shows the geometric differences between RFPMSM and AFPMSM and the corresponding variations in parameters.

Figure 7.

Geometric differences between RFPMSM and AFPMSM; (a) RFPMSM, (b) AFPMSM.

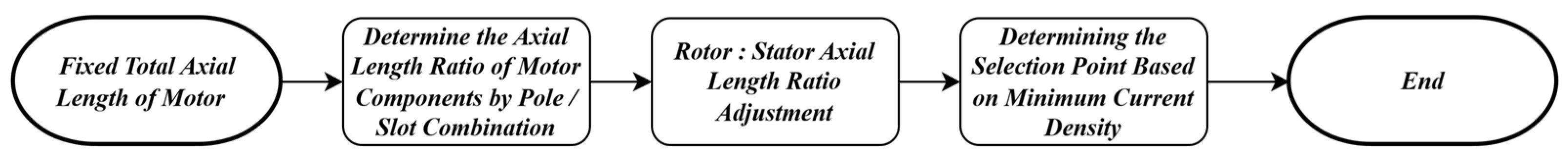

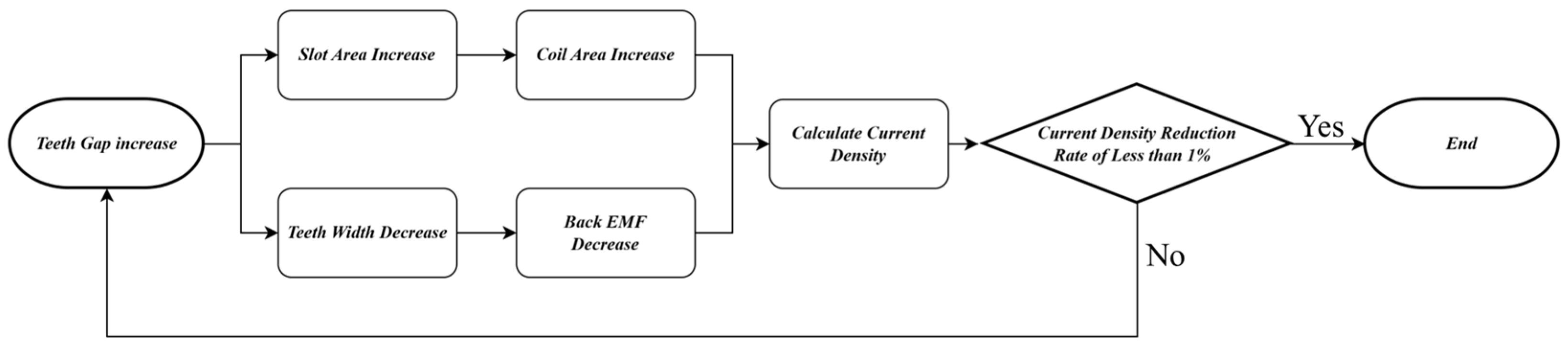

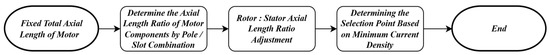

The adjustment of electric and magnetic loadings, namely the load ratio, is carried out by proportionally varying the rotor back yoke and stator back yoke with respect to the permanent magnet thickness while keeping the total axial length fixed. As the permanent magnet thickness changes, the available slot area for winding is determined; consequently, this process can be regarded as fixing the ratio of rotor axial length to stator axial length. The target load ratio is determined as follows. First, considering manufacturability, the minimum permanent magnet thickness is specified as the reference. Based on this, the stator and rotor back yokes are calculated in proportion, and the air gap is fixed. Within the limited axial length, the axial lengths of the stator and rotor are then redistributed. For each redistributed ratio, it is assumed that a winding of the same size as the slot area is wound for one turn. After analysis, the current required to achieve the target output is obtained from the no-load back EMF. Dividing this current by the slot area yields the current density, and the ratio corresponding to the lowest current density is selected. The reason for selecting the point of minimum current density is that it represents the condition requiring the least current to produce the same output, which indicates that the load ratio is most suitably distributed at this point. Through this procedure, the load ratio that satisfies the target performance with minimum current density is identified while keeping the total axial length constant by means of geometric ratio division. Figure 8 shows the loading ratio determination flowchart used to select the rotor–stator axial length ratio corresponding to the minimum current density.

Figure 8.

Loading ratio determination flowchart.

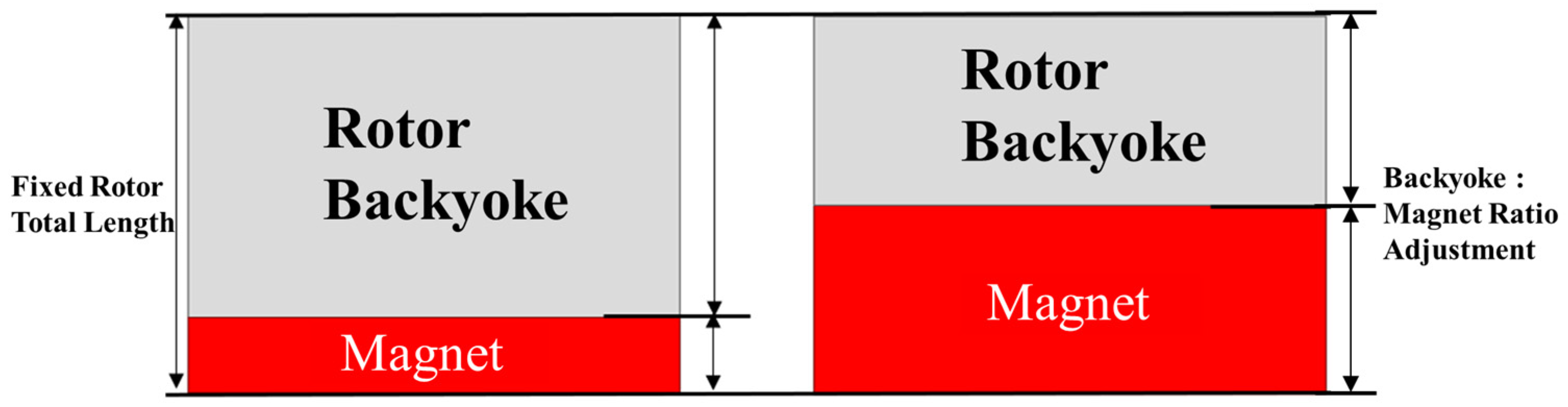

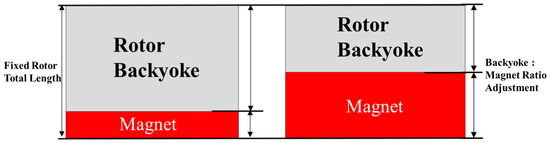

After determining the axial lengths of the rotor and stator through the selection of the load ratio, the axial dimensions are determined and fixed. Subsequently, the axial thicknesses of the rotor back yoke and permanent magnet are allocated. This approach ensures higher output capability while minimizing magnetic saturation under load. To achieve this, the thickness of each element is adjusted. The no-load back EMF for a 1-turn winding is evaluated using FEM, and the magnet thickness is determined accordingly. As the magnet thickness increases, the thickness of the rotor back yoke decreases, thereby increasing the 1-turn back EMF. Figure 9 shows the variation in rotor back-yoke thickness with respect to permanent magnet thickness.

Figure 9.

Adjustment of the ratio between the rotor back yoke and the permanent magnet.

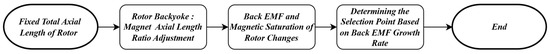

Since the total rotor length is fixed, the 1-turn back EMF does not increase indefinitely as the magnet thickness increases. Instead of increasing indefinitely, the iron core begins to undergo magnetic saturation, and eventually a point is reached where the 1-turn back EMF decreases. Such points are excluded from selection because magnetic saturation has already occurred even under no-load conditions. Specifically, once the rate of increase drops below 0.1%, further increases in magnet thickness no longer provide meaningful performance improvement but only intensify the effects of magnetic saturation. Therefore, the design point is defined as the first point at which the incremental increase in 1-turn back EMF falls below 0.1% as the magnet thickness increases. Through this procedure, the design ensures suppression of magnetic saturation under load while achieving the target performance within the constraint of fixed axial length. Figure 10 shows the flowchart of permanent magnet thickness determinaition flowchart.

Figure 10.

Permanent magnet thickness determination flowchart.

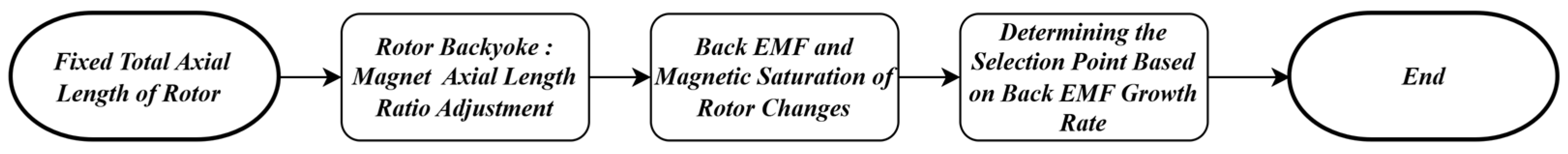

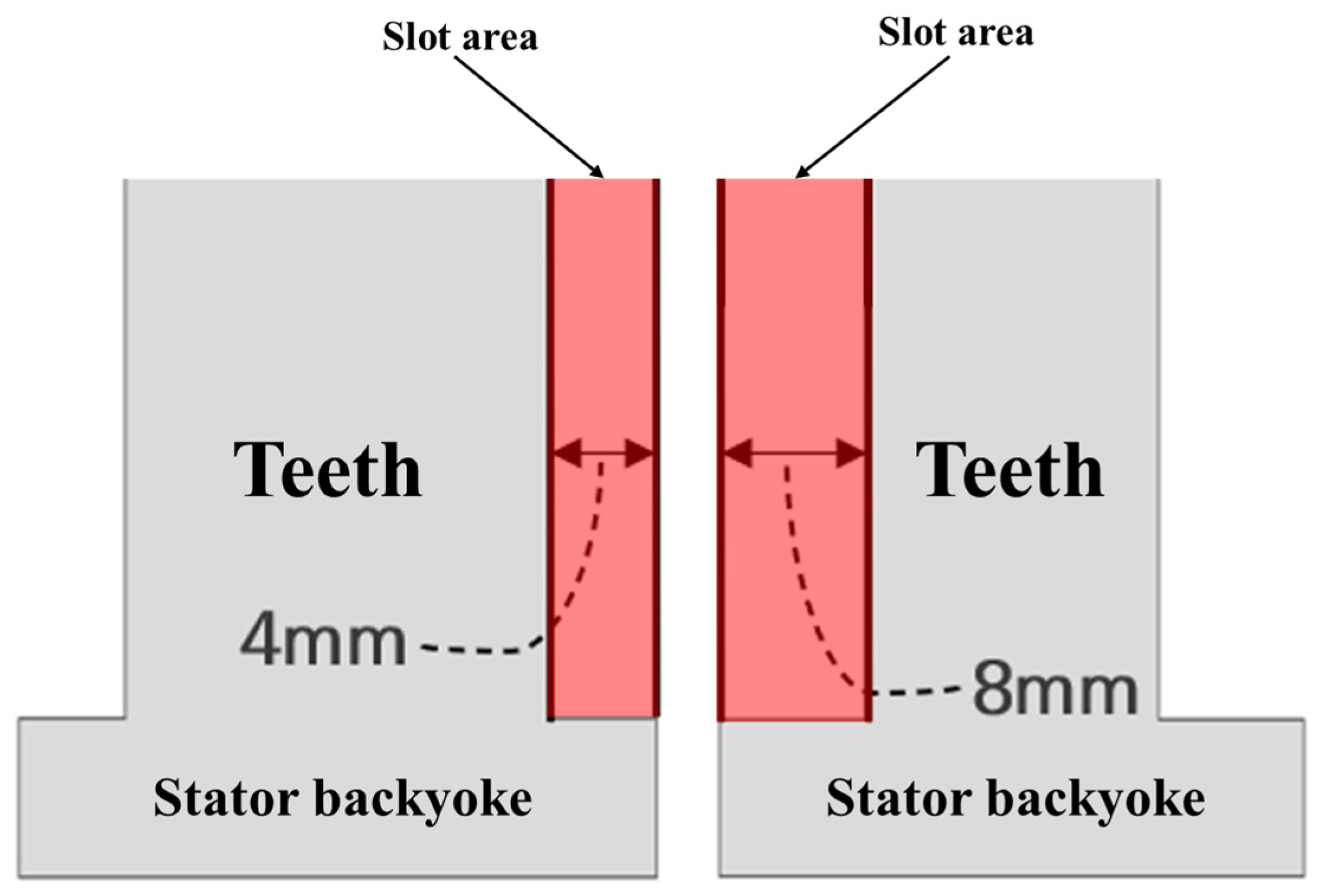

Subsequently, in the stator, the axial lengths of the tooth and the stator back yoke are distributed. This step also aims to secure output while minimizing the risk of magnetic saturation underload. As in the previous case, the distribution lengths are determined based on the no-load back EMF for a 1-turn winding. As the tooth length increases, the thickness of the stator back yoke decreases, eventually reaching magnetic saturation. At this stage, the design point is likewise defined as the point where the incremental increase in the no-load one-turn back EMF falls below 0.1%. Figure 11 shows the flowchart of teeth length determination flowchart.

Figure 11.

Teeth length determination flowchart.

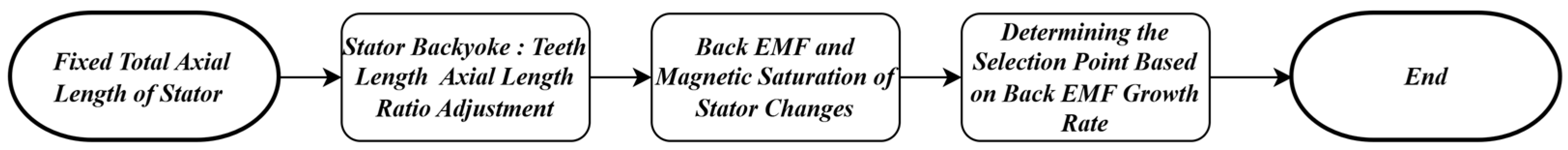

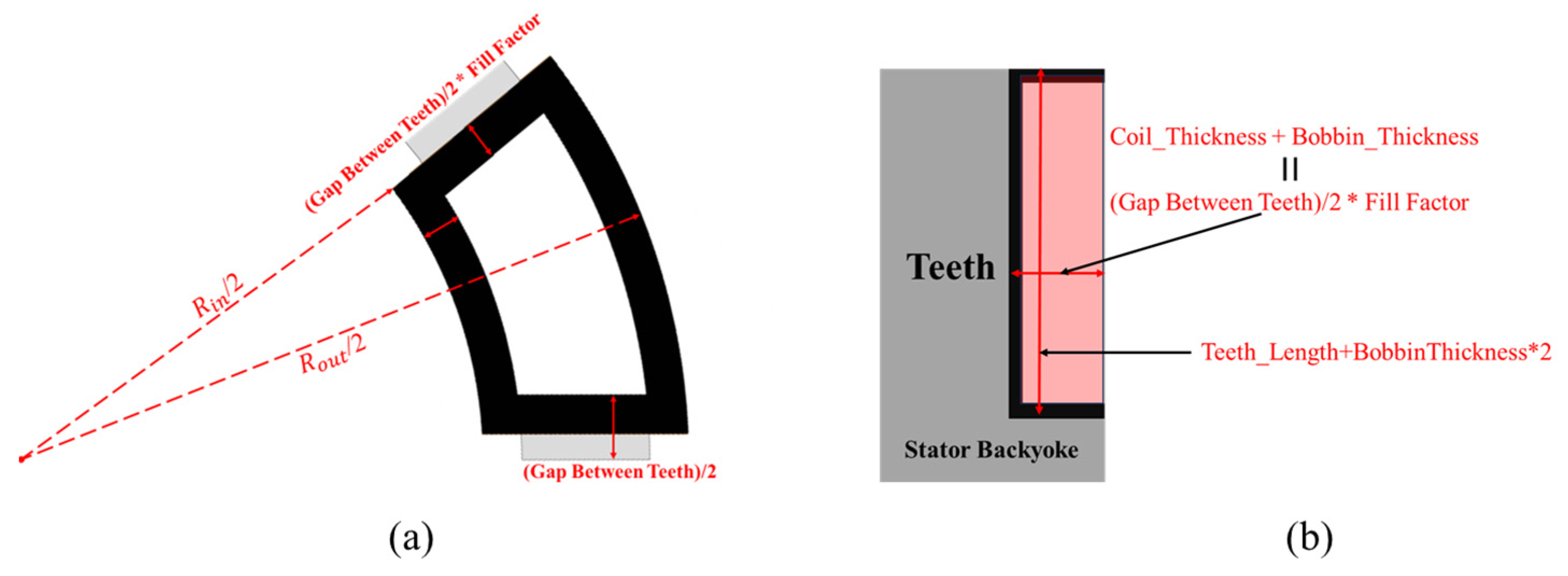

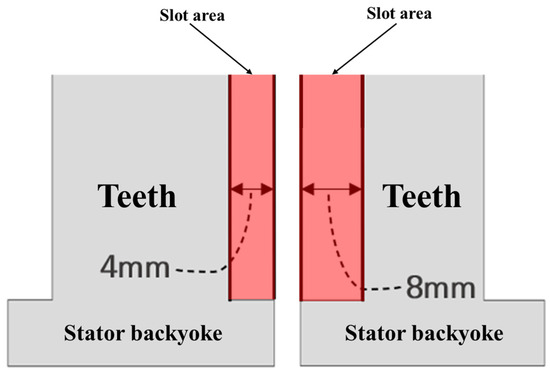

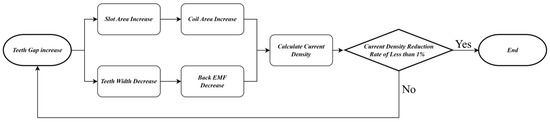

The adjustment of the tooth width of the stator is a key design element directly linked to securing electric loading in the AFPMSM. As shown in Figure 12, reducing the tooth width increases the slot area, allowing for more winding space.

Figure 12.

Slot area variation with stator tooth width adjustment.

This reduces the required current density at the same voltage, thereby raising the output limit of the motor. However, due to the characteristics of the tape-wound core structure, there are physical limitations on the size of the tooth width. As the cross-sectional area of the tooth decreases, securing the magnetic flux path becomes more difficult, which reduces the magnetic flux linkage and consequently decreases output. Therefore, it is important to find a balance point between the increase in electric loading achieved by enlarging the slot area and the reduction in magnetic flux linkage caused by the decrease in tooth cross-sectional area. For each tooth width condition, a no-load FEM analysis was conducted by placing one turn of winding with the same cross-sectional area as the slot area. The current density was then calculated based on the back-EMF. As the tooth width decreases, the current density rapidly decreases, but after a certain point, the rate of reduction slows. The design tooth width was selected at the point where the current density reduction rate falls below 1%. Beyond this point, the benefits of increasing slot area are offset by the reduction in magnetic flux linkage. As a result, the selected tooth width represents a geometry that minimizes current density while also considering the need to secure magnetic flux paths and manufacturability. Figure 13 shows the flowchart of teeth width determination.

Figure 13.

Teeth width determination flowchart.

Accordingly, this section establishes a design process applicable to both types of in-wheel AFPMSM (shoe-type round wire winding and bobbin-type rectangular wire winding without shoes). However, for the shoe-type round wire winding, the significant impact of manufacturing constraints such as mold design, insertion process, and size-dependent stiffness makes it difficult to apply the process uniformly. Therefore, the shoe geometry is treated as a consideration dependent on the manufacturing environment, and a method prioritizing the derivation of common variables was adopted. In the subsequent stages, among the multiple design options derived based on the target performance, the model with characteristics most aligned with the requirements was selected as the final design. The overall design procedure was then completed by calculating the number of winding turns while considering voltage limitation conditions. Furthermore, based on the selected base model, complementary designs were performed in parallel to improve manufacturability and pursue additional performance enhancements, thereby finalizing the structure.

Section 3.2 applies the unified design process established in this section to the base model numerically. Through FEM-based analysis, it presents process-specific data along with graphs, clearly defining the selection criteria.

3.2. FEM Verification of the Process

To verify the validity of the proposed process, FEM results obtained by sequentially performing its steps are presented. FEM analysis was performed using ANSYS Maxwell’s 3D model. After allocating the moving band, Transient Magnetic analysis was performed, and the model was reorganized in consideration of symmetry after designing the entire shape. Accordingly, a detailed mesh was given to secure calculation accuracy. Magnetic insulation conditions were applied to the background surrounding the entire motor, and mesh subdivision was performed near the air gap. The current excitation method used a balanced three phase current based on a current source.

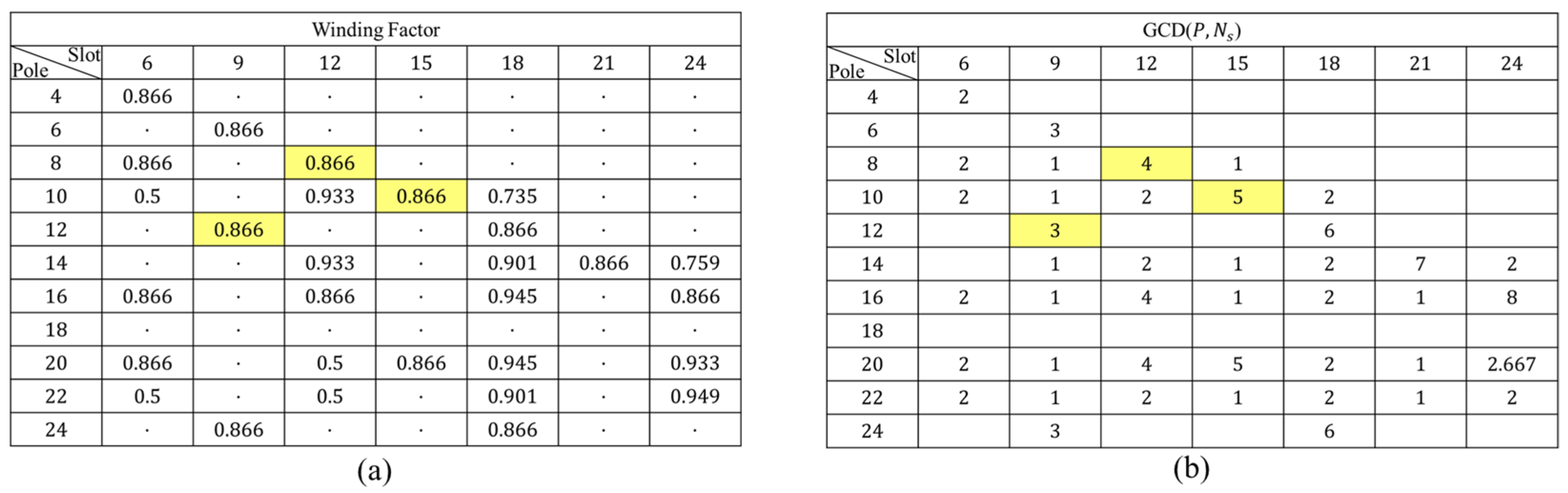

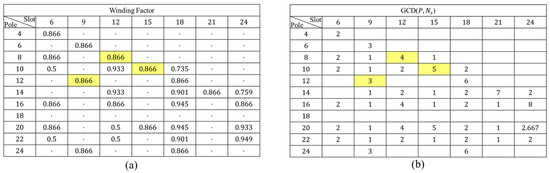

3.2.1. Pole/Slot Combination Selection

As mentioned earlier, the process begins with selecting the pole/slot combination. Since the model is an AMR in-wheel motor, the mechanical robustness of the entire drive system is critical. To achieve this, it was necessary to select a pole/slot combination that reduces excitation force at the motor stage [14]. Furthermore, as the number of poles increases, the number of teeth must also increase to utilize the pitch factor which complicates stator core manufacturing. Therefore, using Figure 14, three pole-slot combinations were selected that suppress cogging torque while keeping the pole and slot count as low as possible: 8-pole 12-slot, 10-pole 15-slot, and 12-pole 9-slot. As mentioned in Section 2, two structures were selected and compared: the shoe-type round wire winding and the bobbin-type rectangular wire winding without shoes.

Figure 14.

The winding factors and greatest common divisors for various pole/slot combinations in the pole/slot selection process, the highlighted parts represent the selected pole/slot combination.; (a) Winding factor by pole-slot combination, (b) Greatest common divisor by pole-slot combination.

3.2.2. Initial Modeling

Initial modeling was carried out based on the proposed design procedure, applying the actual constraints. Considering the in-wheel motor application, the outer diameter was set to 180 mm, the inner diameter to 100 mm, and the axial length to 40 mm. This considers the structural characteristics of the AFPMSM: the outer diameter was set larger than the axial length to ensure torque density, while the inner diameter was sufficiently large to accommodate the gearbox and drive system. In addition, the values including the winding end turns were applied to reflect the actual manufacturing geometry. Furthermore, with the axial length constrained, the adjustable axial length variables were limited to tooth length, shoe thickness, rotor back yoke thickness, stator back yoke thickness, and permanent magnet thickness. Among these, tooth length can be derived from the remaining variables within the total axial length constraint, and shoe thickness has low design freedom due to manufacturability issues. Therefore, the ratios of the stator back yoke, permanent magnet, and rotor back yoke were defined as the primary design variables. Accordingly, for the 8-pole 12-slot combination, the ratios of the axial length were set to 2.04:1:2.4; for the 10-pole 15-slot, 1.7:1:2; and for the 12-pole 9-slot, 1.36:1:1.6. These ratios show that as the number of poles increases, the magnetic flux per pole decreases, allowing the rotor back yoke thickness to be reduced. In addition, during the following stages of the process, the outer and inner diameters of the AFPMSM, including the winding end turns, were kept fixed by parameterization, enabling progression through the subsequent procedures.

Figure 15 shows the setting of design variables for fixing the outer and inner diameters, including the end turns.

Figure 15.

Variables for fixing the outer and inner diameters during the design process; (a) Variable setting for tooth gap after fixing the outer and inner diameters, (b) Configuration of tooth gap variables.

Table 2 presents the design constraints and target specifications. Since the current density is directly related to the thermal characteristics of the motor, it must be carefully determined. The reference motor used water cooling with a current density of 18 A/mm2, whereas in this study the same cooling method was adopted but the current density was conservatively limited to 15 A/mm2 to ensure thermal stability. The reference motor is a mass-produced model with verified performance under the same cooling configuration, and thus, maintaining the same cooling structure while reducing the current density further enhances thermal reliability.

Table 2.

Design constraints and target specifications.

3.2.3. Selection of Loading Ratios

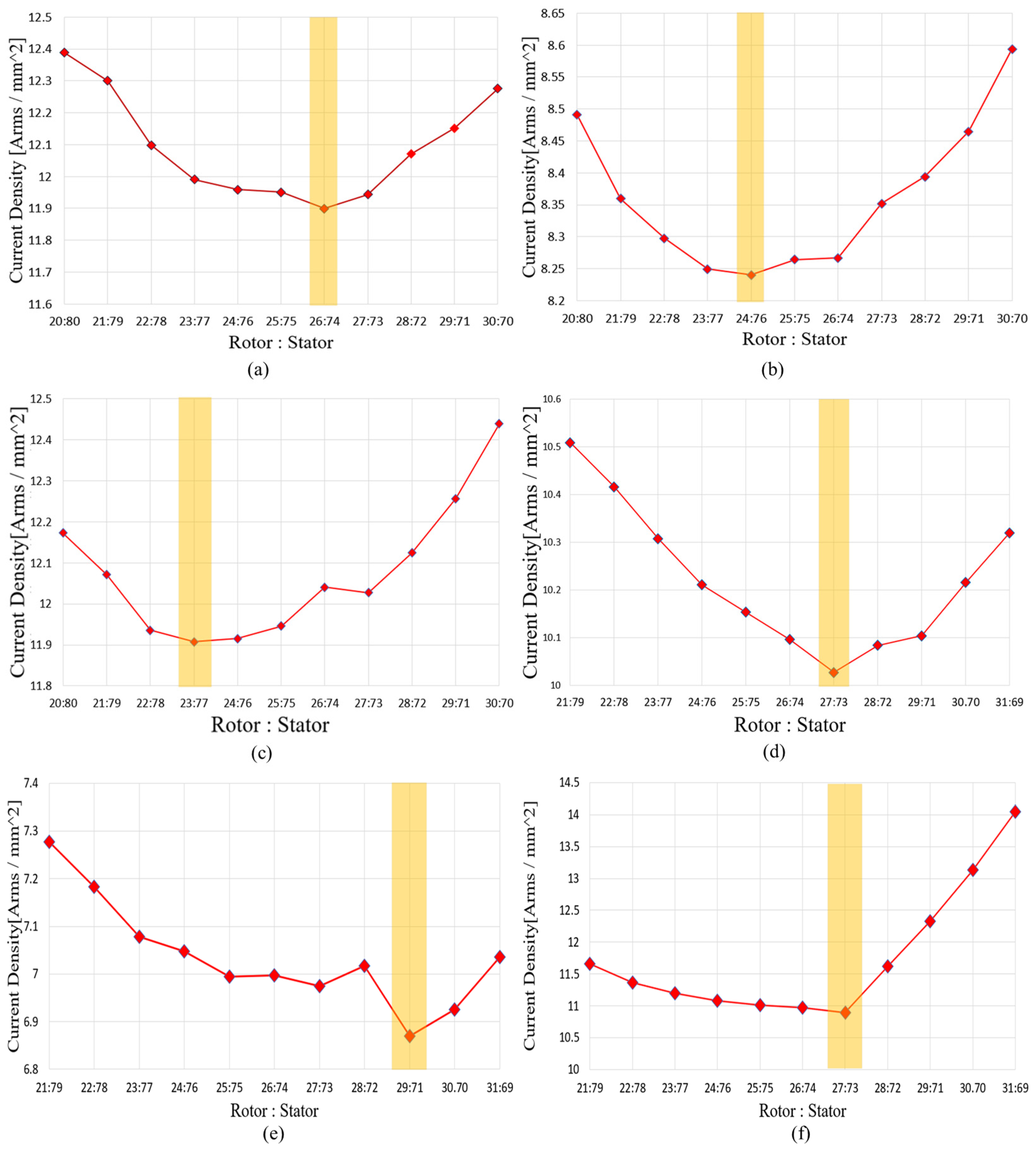

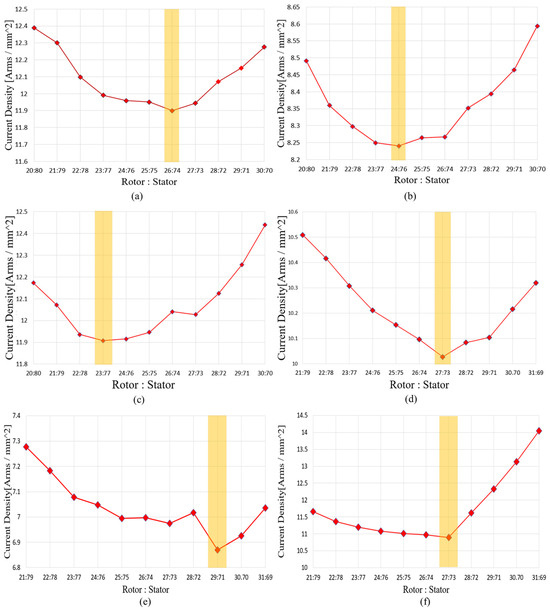

Figure 16 shows the variation in current density and the selected points based on the rotor–stator ratio during the loading ratio process and the x-axis of Figure 16. represents the ratio of the axial length occupied by the rotor and the stator, with the total active axial length (excluding the air gap) normalized to 100%. The loading ratio selection was performed based on the ratio of the stator back yoke, permanent magnet, and rotor back yoke defined in the initial model. First, the initial model was constructed by applying the ratios defined in Section 3.2.2. Then, the ratio of the total rotor length to the total stator length was varied by adjusting the permanent magnet thickness. The winding types selected were the shoe-type round wire structure and the shoe-less bobbin-type rectangular wire structure, as described in the previous section. The winding cross-sectional area used in the FEM analysis was defined as follows: For the shoe-type round wire structure, the winding cross-sectional area was calculated as the slot area multiplied by a 40% fill factor. For the shoe-less bobbin-type rectangular wire structure, the winding cross-sectional area was defined as the remaining slot area after subtracting the bobbin’s occupied volume. Based on these defined cross-sectional areas, no-load FEM analysis was performed to obtain the phase BEMF under no-load conditions. Using this result, the current required to achieve the target output was calculated according to Equation (10) (excluding losses):

where is the no-load phase BEMF and is the phase current. The calculated current was then divided by the winding cross-sectional area to derive the current density. The point at which the current density was minimized was selected as the design point by adjusting the rotor-to-stator ratio.

Figure 16.

Results of the loading ratio selection process by pole/slot combination, x-axis is the ratio of the rotor and the stator to the total axial length excluding the air gap in the total axial length when it is 100, where the highlighted part represents the selected Rotor:Stator Ratio; (a) Bobbin-type rectangular-wire winding without shoes, 8P12S; (b) Bobbin-type rectangular-wire winding without shoes, 10P15S; (c) Bobbin-type rectangular-wire winding without shoes, 12P9S; (d) Shoe-type round-wire winding, 8P12S; (e) Shoe-type round-wire winding, 10P15S; (f) Shoe-type round-wire winding, 12P9S.

All subsequent analyses were based on a single turn per slot. This is because as the number of turns increases, the no-load phase BEMF increases proportionally, and the required current decreases inversely. Consequently, the final current density remains unchanged. Therefore, pre-calculating the number of turns is unnecessary in this stage where the core shape and permanent magnet usage are continuously varied. Calculating the current density using a 1-turn model thus provides consistent results regardless of the final number of turns. This assumption simplifies the analysis while maintaining sufficient validity for the relative comparison of rotor–stator ratios and the derivation of design points.

3.2.4. Adjustment of the Ratio of Permanent Magnet Thickness to Rotor Back Yoke Thickness

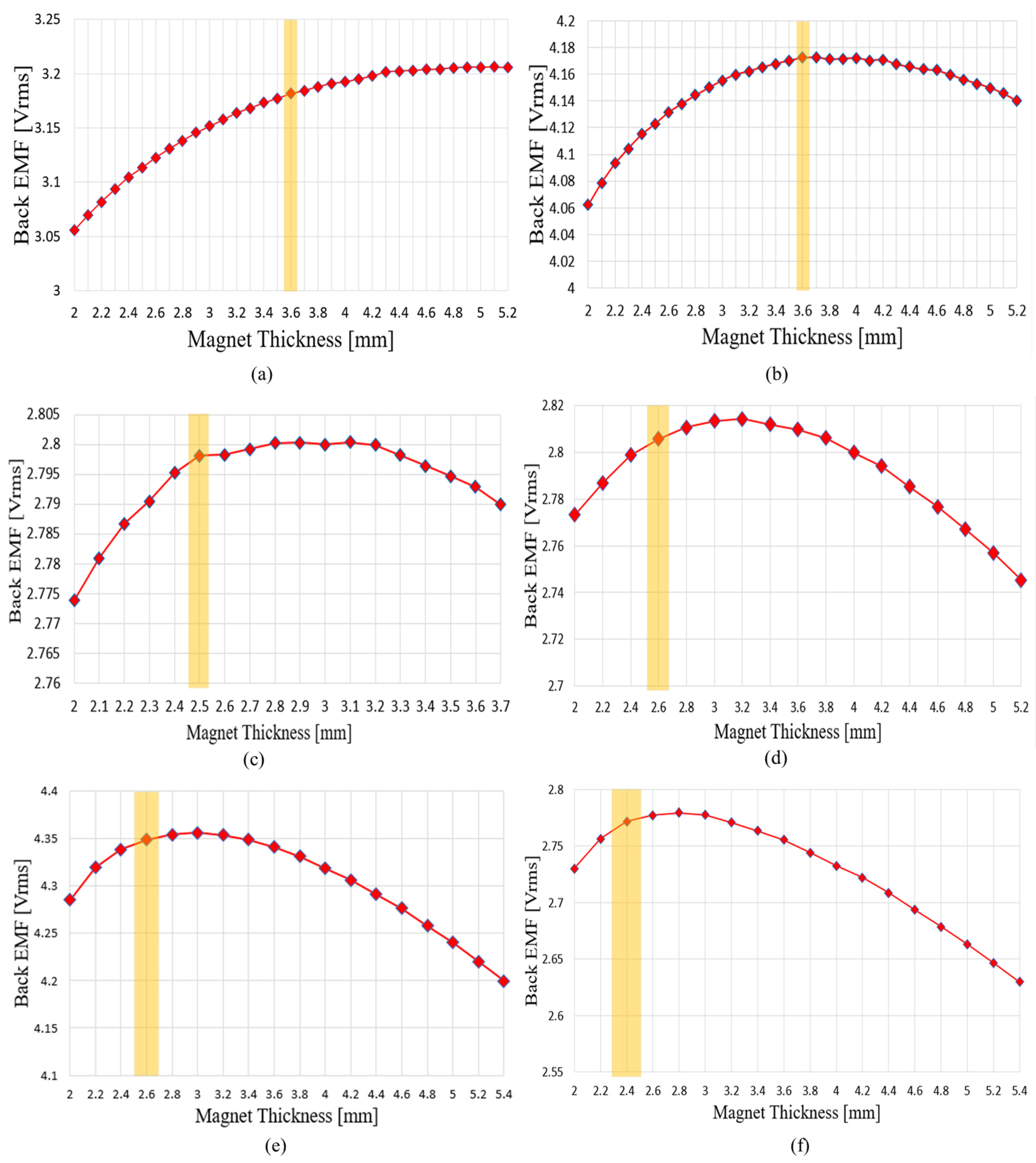

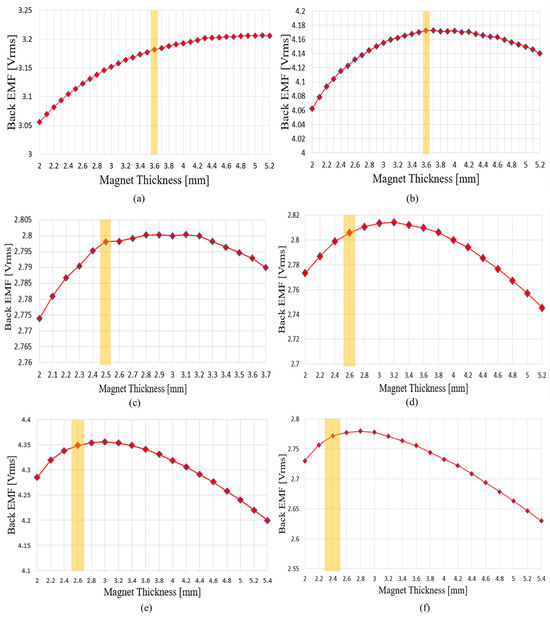

Figure 17 shows the variation in no-load phase BEMF and the selected points based on adjustments to the permanent magnet thickness and rotor back-yoke thickness. Since the total axial length of the rotor and stator was determined in the previous section, this section adjusted the ratio of the rotor back-yoke thickness to the permanent magnet thickness. FEM analysis performed while stepwise varying the permanent magnet thickness revealed that the no-load phase BEMF initially increased significantly as the magnet thickness increased. However, as the permanent magnet thickened and the rotor back yoke thinned, magnetic saturation occurred, causing the rate of increase to gradually diminish. Therefore, increasing the magnet thickness indefinitely only raises material costs and losses due to magnetic saturation, rather than improving output. Consequently, the permanent magnet thickness was defined as the value at which the rate of increase in no-load phase BEMF first drops below 0.1%. Under this condition, the ratio between the rotor back-yoke thickness and the permanent magnet thickness was determined. This selection method suppresses the risk of magnetic saturation under load while ensuring efficient magnet utilization.

Figure 17.

Results of the rotor ratio adjustment process for each pole–slot combination, where the highlighted part represents the selected magnet thickness. (a) Bobbin-type rectangular-wire winding without shoes, 8P12S; (b) Bobbin-type rectangular-wire winding without shoes, 10P15S; (c) Bobbin-type rectangular-wire winding without shoes, 12P9S; (d) Shoe-type round-wire winding, 8P12S; (e) Shoe-type round-wire winding, 10P15S; (f) Shoe-type round-wire winding, 12P9S.

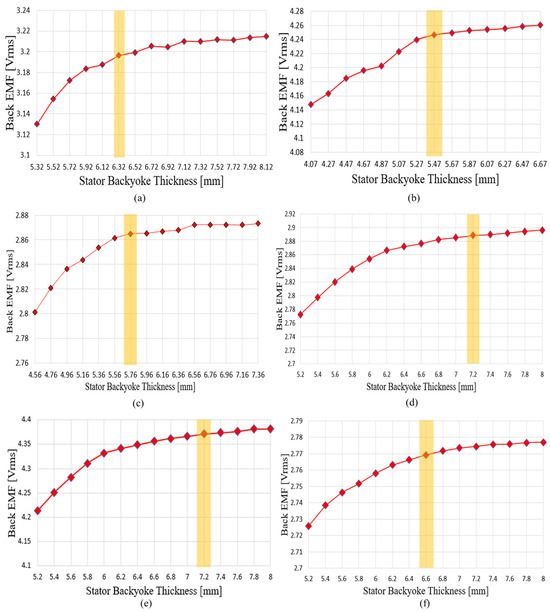

3.2.5. Adjustment of Tooth Length and Stator Back-Yoke Thickness Ratio

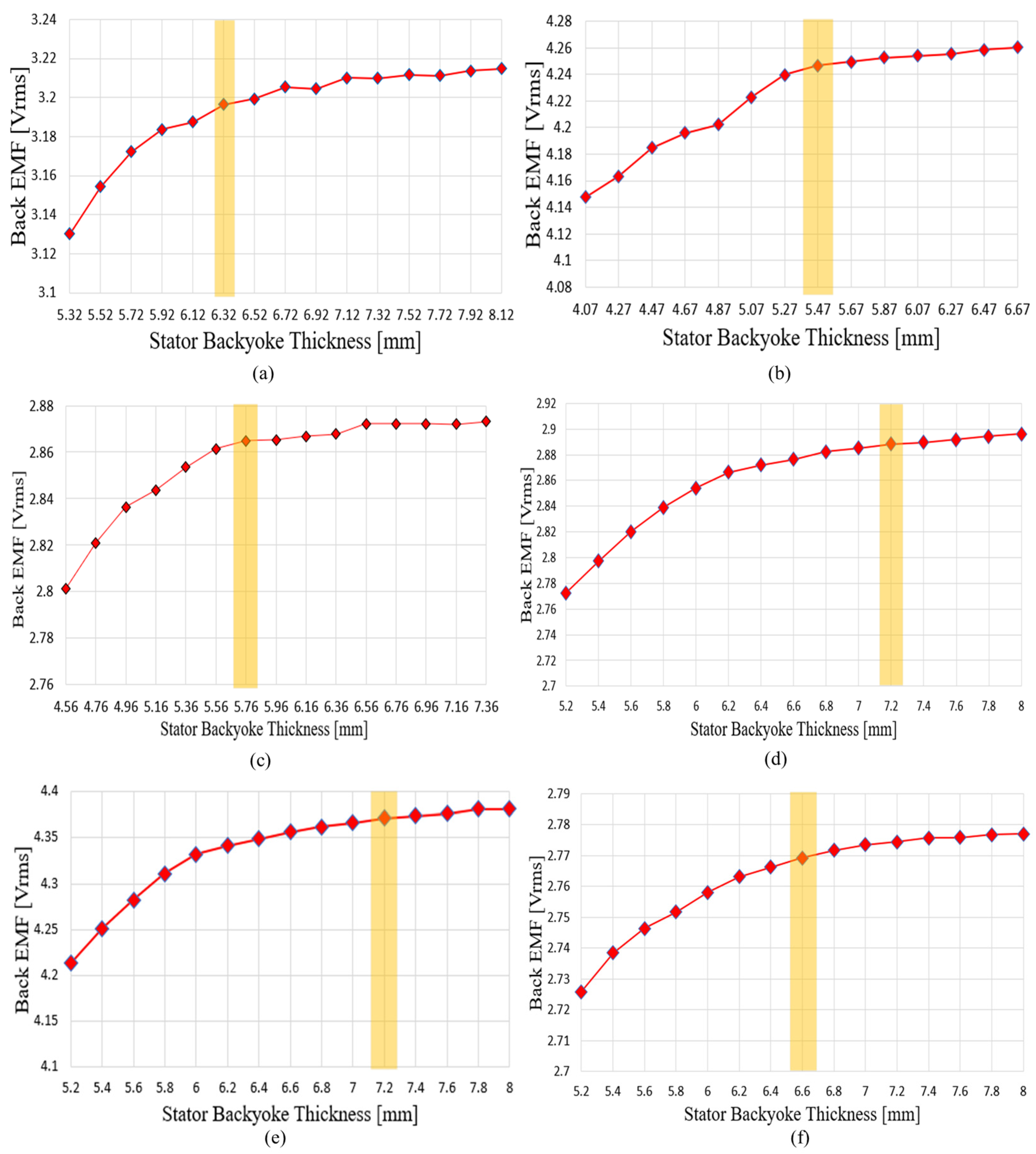

Figure 18 shows the variation in no-load phase BEMF and the selected points according to adjustments in stator back-yoke thickness and tooth length. In this section, the ratio between stator tooth length and stator back-yoke thickness was adjusted. As the stator back-yoke thickness increased, the magnetic flux path was secured, resulting in an increase in the no-load phase BEMF obtained from FEM analysis. However, once a certain back-yoke thickness was reached, further increases provided only limited expansion of the flux path, leading to a plateau in the no-load phase BEMF. Increasing the back-yoke thickness beyond this point reduced the slot area, thereby increasing current density for the same output. Therefore, the selection point was defined as the initial point at which the rate of increase in no-load phase BEMF falls below 0.1%. By determining the ratio between tooth length and back-yoke thickness based on this criterion, the design secures the magnetic flux path while suppressing the risk of magnetic saturation.

Figure 18.

Results of the stator ratio adjustment process for each pole–slot combination, where the highlighted part represents the selected stator back yoke thickness. (a) Bobbin-type rectangular-wire winding without shoes, 8P12S; (b) Bobbin-type rectangular-wire winding without shoes, 10P15S; (c) Bobbin-type rectangular-wire winding without shoes, 12P9S; (d) Shoe-type round-wire winding, 8P12S; (e) Shoe-type round-wire winding, 10P15S; (f) Shoe-type round-wire winding, 12P9S.

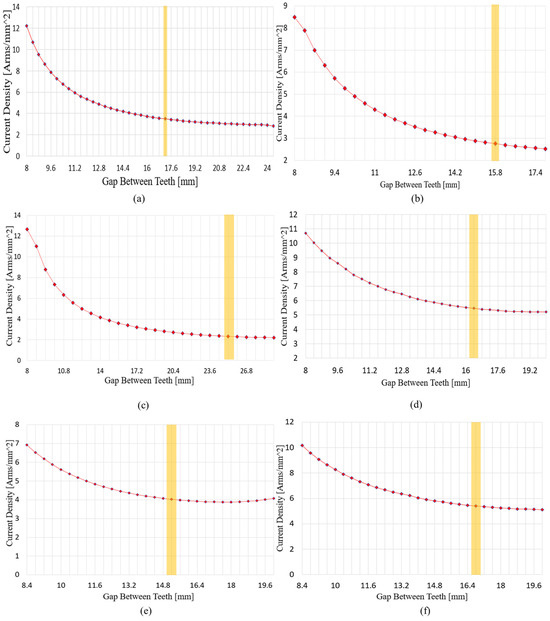

3.2.6. Tooth Width Adjustment

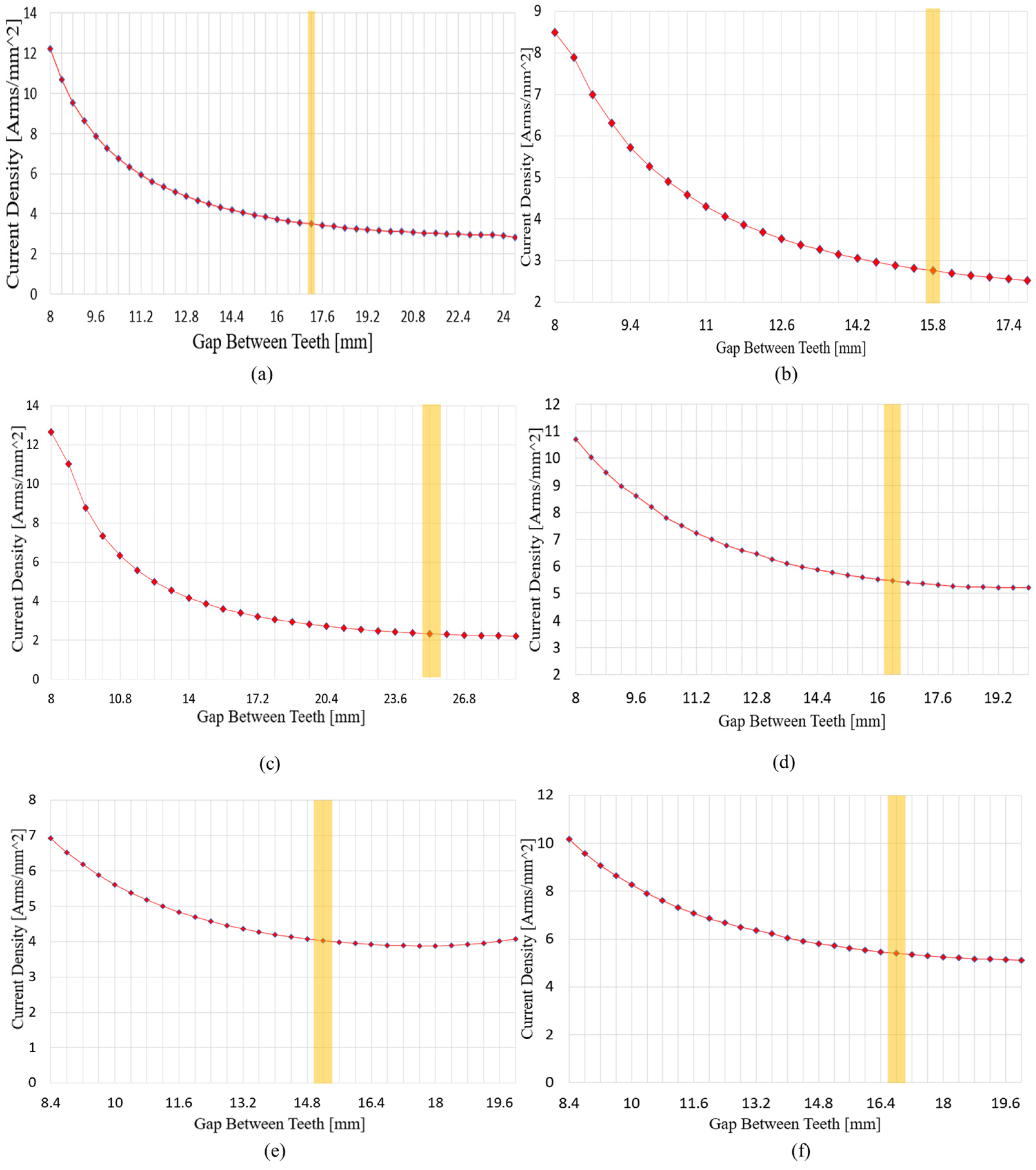

Figure 19 shows the variation in current density and the selected points according to tooth gap adjustment.

Figure 19.

Results of the tooth width adjustment process for each pole–slot combination, where the highlighted part represents the selected teeth thickness. (a) Bobbin-type rectangular-wire winding without shoes, 8P12S; (b) Bobbin-type rectangular-wire winding without shoes, 10P15S; (c) Bobbin-type rectangular-wire winding without shoes, 12P9S; (d) Shoe-type round-wire winding, 8P12S; (e) Shoe-type round-wire winding, 10P15S; (f) Shoe-type round-wire winding, 12P9S.

After the axial length–related variables were fixed, motor performance was adjusted by varying the stator tooth width. The tooth width was controlled through changes in the tooth gap and served as a key variable affecting both the slot area and the magnetic flux path. As the tooth width increased, the slot area decreased, limiting winding space and raising current density, while magnetic flux linkage increased, which favored flux path formation. Conversely, as the tooth width decreased, the slot area expanded and current density decreased, but magnetic saturation of the teeth intensified, leading to a plateau in the increase in no-load phase BEMF obtained from FEM analysis. The FEM results indicated that the reduction in current density due to decreasing tooth width was significant initially, but the rate of reduction declined sharply beyond a certain point. Therefore, the first point at which the current density reduction rate dropped below 1% and the no-load phase BEMF ceased to increase meaningfully was selected as the design point. This represents a balance between securing slot area and maintaining flux paths, reflecting a compromise that accounts for both electromagnetic performance and manufacturability.

3.2.7. Final Model Selection

In the preceding sections, the ratios of rotor and stator axial lengths and the thicknesses of the permanent magnet and rotor back yoke, as well as the stator tooth length, stator back-yoke thickness, and tooth width, were adjusted to derive the values of each variable. The candidate models obtained through this process all satisfied the external geometric constraints and target output conditions, but differences remained in terms of output and efficiency.

Table 3 presents the performance of the bobbin type after the design process, while Table 4 presents the performance of the shoe type.

Table 3.

Performance of the Bobbin Type After the Process.

Table 4.

Performance of the Shoe Type After the Process.

According to the process, the final model should be selected and the number of turns determined by considering the above factors. However, since the drive system employing the in-wheel motor integrates multiple components, additional design steps such as reducing the outer diameter and minimizing torque ripple were carried out to meet the demand for further downsizing. This was possible because the initial design exhibited a higher output than the target value, allowing the outer diameter to be reduced and torque ripple to be minimized without compromising performance. When the outer diameter of the motor is reduced, the amount of magnet material decreases, leading to a reduction in the no-load phase BEMF. Consequently, the number of turns must be redefined with consideration of the voltage limitation. Therefore, after this section, additional designs focusing on outer diameter reduction and torque ripple mitigation were carried out, and the final model was selected based on these results.

4. Additional Design Considerations

This chapter sequentially examined outer diameter reduction, torque ripple reduction, and permanent magnet eddy current loss reduction for the candidate models identified in Section 3. The final model was selected from those derived through this process.

4.1. Outer Diameter Reduction

Table 5 and Table 6 present pole/slot-specific data for the bobbin type and the shoe type after reducing Outer Diameter of each model. Although the target output of 1.8 kW could have been achieved by further reducing the outer diameter or lowering the current density of certain models, some models already achieved an output close to 1.8 kW at the maximum allowable current density when the outer diameters of the bobbin-type and shoe-type motors were kept similar. To maintain consistency in the comparison between models, no additional adjustments to the outer diameter or current density were made. Considering the heavy-load operating conditions of the AMR, the final models were designed with a sufficient output margin.

Table 5.

Bobbin-Type Performance after Outer Diameter Reduction with Max Current Density and Multi-Turn Applied.

Table 6.

Shoe-Type Performance after Outer Diameter Reduction with Max Current Density and Multi-Turn Applied.

Although the target output was satisfied through the process described in Section 3, additional design considerations for outer diameter reduction were explored. Since reducing the outer diameter decreases magnet usage and no-load phase EMF, recalculating the number of turns while considering voltage limitation conditions is required. Therefore, FEM analysis was performed under the conditions of outer diameter reduction, and the data were verified after recalculating the number of turns.

When calculating the number of turns for the bobbin type, prime numbers were excluded to maximize utilization of the rectangular slot area. In addition, the bobbin type includes an AC loss component. AC loss arises from time-varying magnetic fields acting on the windings and occurs predominantly in the bobbin type because, without shoes, more flux generated by the permanent magnets passes through the windings before reaching the teeth [15].

Furthermore, the copper windings of the bobbin types 8P12S, 10P15S, and 12P9S are arranged in 2 × 5, 2 × 4, and 3 × 3 (radial layer × axial layer) configurations. Among them, the 12P9S type has the largest area of winding exposed to magnetic field variation, leading to the greatest tendency for AC loss.

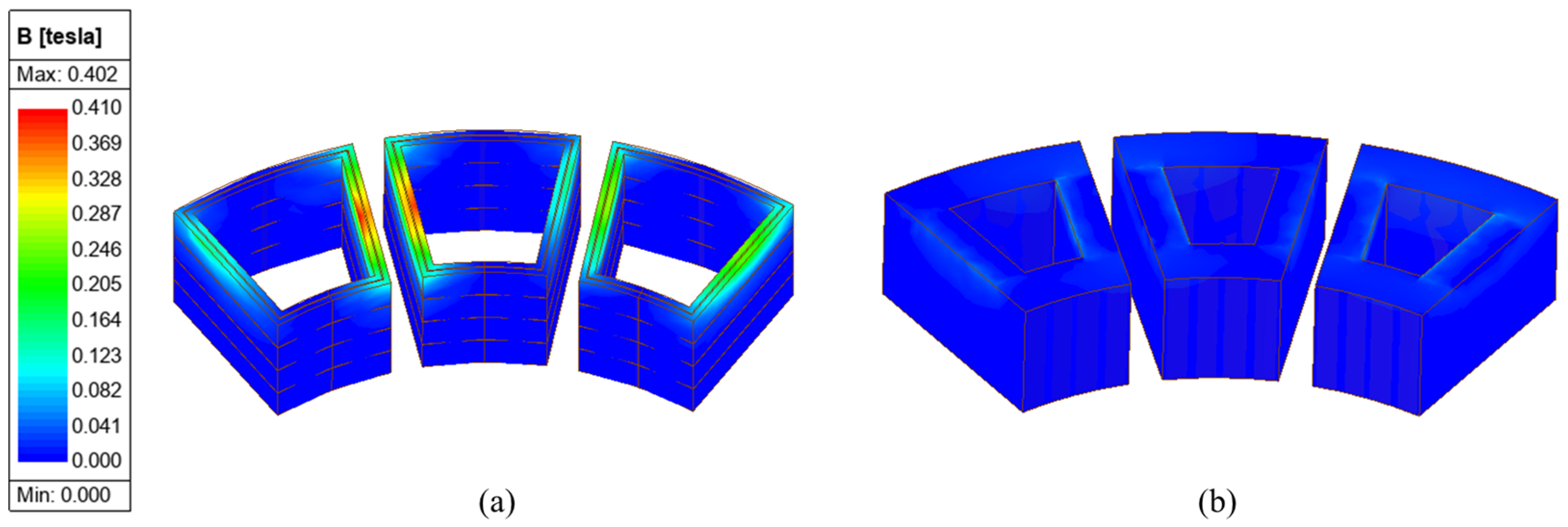

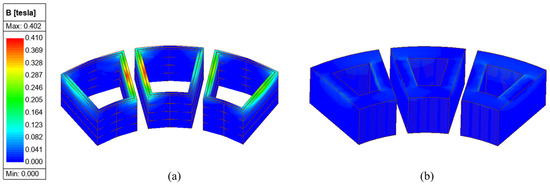

Figure 20 shows the magnetic flux density acting on the windings in the bobbin and shoe types. Fundamentally, reducing this AC loss is difficult. Therefore, as shown in Table 5 and Table 6, additional design work was carried out to mitigate the significant permanent magnet eddy current losses and torque ripple.

Figure 20.

Magnetic flux density variations affecting windings by stator type; (a) Bobbin type segmented windings, (b) Shoe type ring windings.

4.2. Reduction in Torque Ripple and Permanent Magnet Eddy Current Losses

Torque ripple directly affects driving stability and NVH characteristics, and permanent magnet eddy current losses lead to increased losses and heat generation. Therefore, this section presents a complementary design that simultaneously addresses both issues. The eddy current loss generated in the permanent magnet is given by Equation (11):

Here, represents the eddy current loss over time, is the eddy current loss per unit volume, the resistivity, is the current density, is flux density, is the horizontal length of the conductor perpendicular to the magnetic flux path, is the conductor height, and is the conductor thickness. According to Equation (11), reducing the horizontal length of the conductor perpendicular to the flux path decreases the eddy current loss. Therefore, in this study, eddy current loss in the permanent magnet was reduced by segmenting the magnet. In addition, pole arc ratio adjustment was applied to reduce pole-to-pole magnetic flux leakage and torque ripple.

Table 7 and Table 8 show the performance of the bobbin and shoe types, respectively, after outer diameter reduction and the application of these additional measures. As can be seen, segmentation of the permanent magnets significantly reduced eddy current loss within the magnets, and torque ripple was substantially reduced through pole arc ratio adjustment, so motor efficiency improved as a result.

Table 7.

Final Performance of the Bobbin Type after Torque Ripple and Permanent Magnet Eddy Current Loss Reduction by Pole Arc Ratio Adjusting.

Table 8.

Final Performance of the Shoe Type after Torque Ripple and Permanent Magnet Eddy Current Loss Reduction by Pole Arc Ratio Adjusting.

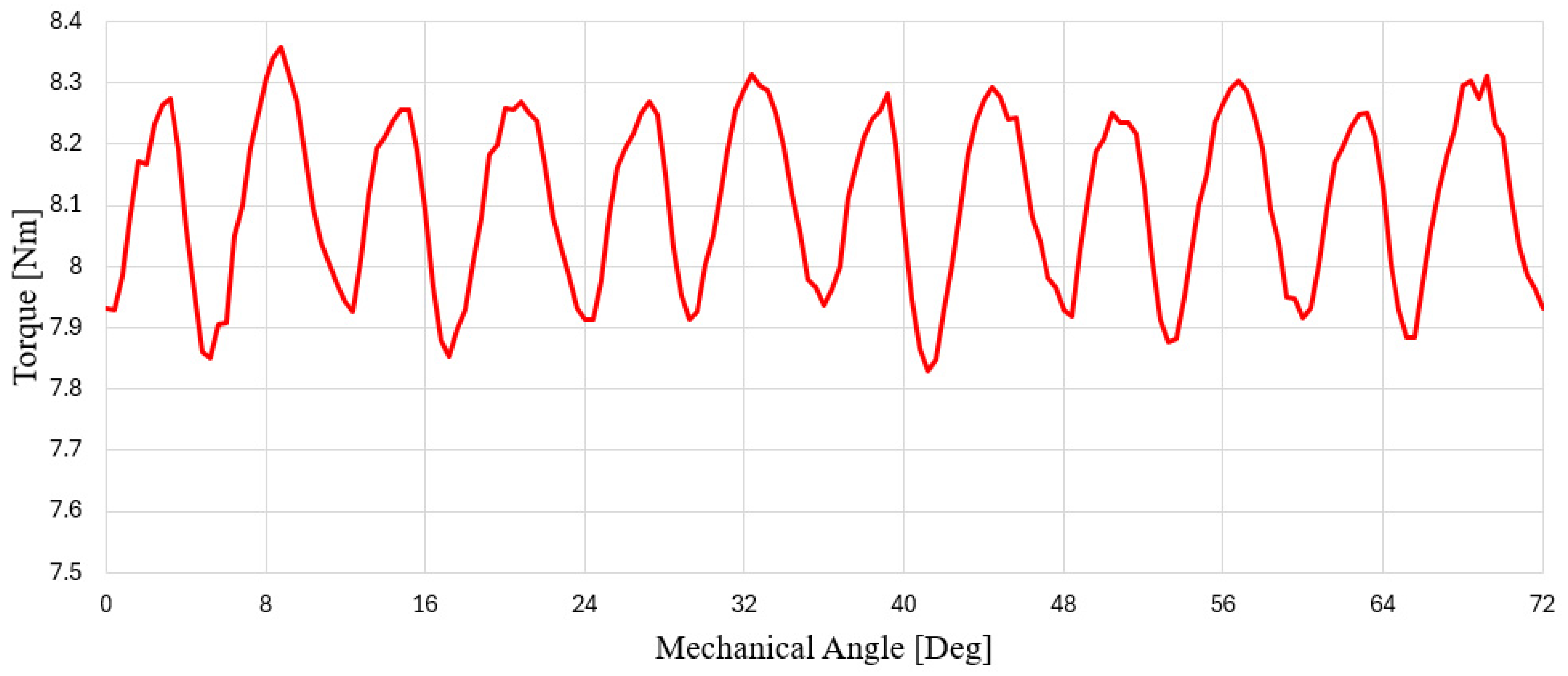

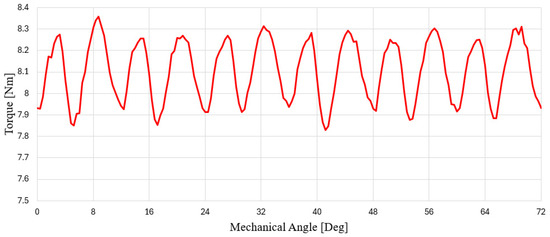

For a fair comparison, all final models were evaluated under the same current density conditions. Among them, the 10P15S model using the shoe-type round wire exhibited the most favorable indicators in terms of torque ripple and efficiency and was therefore selected as the final model. Torque waveform of final model is shown in Figure 21. The torque Ripple (%) was calculated by using Equation (14).

To evaluate the waveform quality of the back-EMF, the total harmonic distortion (THD) was also analyzed and defined as Equation (15).

The transient magnetic simulation was performed for two electrical periods, and only the second period—where the torque and losses had fully converged—was used for FFT analysis. The harmonic components and the fundamental component were then separated from the steady-state back-EMF waveform to calculate the THD.

Figure 21.

Torque Waveform of Final Model.

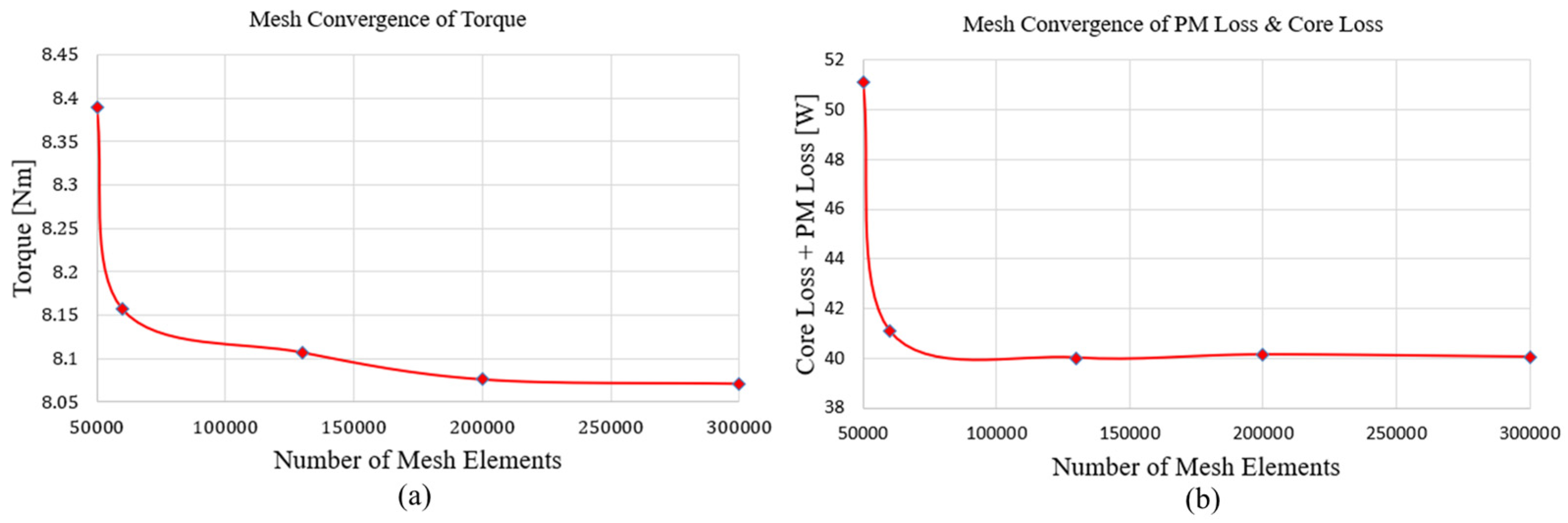

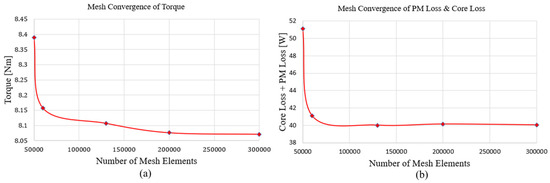

4.3. Verification and Reliability of FEM Results

To verify the numerical reliability of the FEM analysis, a mesh convergence study was conducted by varying the number of mesh elements from 50,000 to 300,000. As shown in Figure 22. both electromagnetic torque and total losses (core loss + permanent magnet eddy current loss) are gradually stabilized as the mesh density increased. The variation in torque between 200,000 and 300,000 elements was less than 0.5%, and the total loss also converged to approximately 40 W. Therefore, the FEM model was considered numerically converged when the mesh size exceeded about 200,000 elements. All FEM analyses throughout the proposed design process were performed using approximately 200,000 mesh elements. The convergence confirmed the numerical stability and reliability of the simulation results.

Figure 22.

Mesh Convergence of Electromagnetic Torque and Total Losses for the FEM Model.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a 1.8 kW AFPMSM for in-wheel motor applications was used to define a unified design process that incorporates external dimensional constraints, and its validity was verified through FEM analysis. Candidate models were derived through pole/slot combination selection, loading ratio determination, rotor–stator ratio adjustment, and tooth thickness adjustment, and all models were confirmed to satisfy the target output and design constraints.

Additionally, an outer diameter reduction design was performed, and to address the resulting decrease in no-load back EMF, the number of winding turns was recalculated considering voltage limitation conditions. Complementary designs were also conducted to reduce torque ripple and permanent magnet eddy current losses, confirming that techniques such as pole arc ratio adjustment and magnet segmentation were effective in improving performance.

As a result, this study presents a design procedure capable of maintaining and enhancing performance while satisfying the multiple constraints required for in-wheel motor applications. This not only offers practical applicability in the commercialization of in-wheel motors but also provides a methodological basis applicable to the design of other axial flux motors subject to similar constraints.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.-H.K.; methodology, S.-B.K.; software, H.-G.K.; validation, S.-B.K.; formal analysis, M.-K.H.; investigation, M.-K.H.; resources, S.-B.K.; data curation, H.-G.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-B.K.; writing—review and editing, M.-K.H.; visualization, S.-H.K.; supervision, W.-H.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) grant funded by the Korea Government (MOTIE) (RS-2024-00436216, Human Resource Development Program for Industrial Innovation (Global)). This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) grant funded by the Korea government (MOTIE) (20214000000060, Department of Next Generation Energy System Convergence based-on Techno-Economics—STEP).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hou, J.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, S.; Yang, D. Topology Mapping and Connectivity Detection for Autonomous Mobile Robot Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 20th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), Bari, Italy, 28 August–1 September 2024; pp. 3168–3173. [Google Scholar]

- Tarao, S.; Fujiwara, Y.; Tsuda, N.; Takata, S. Development of Autonomous Mobile Robot Platform Equipped with a Drive Unit Consisting of Low-End In-Wheel Motors. In Proceedings of the 2020 5th International Conference on Control and Robotics En-gineering (ICCRE), Osaka, Japan, 24–26 April 2020; pp. 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, D.-K.; Cho, Y.-S.; Ro, J.; Jung, S.-Y.; Jung, H.-K. Optimal Design of an Axial Flux Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor for the Electric Bicycle. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2016, 52, 8201204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Ba, X.; Liu, L.; Lu, H.; Lei, G.; Yin, W.; Zhu, J. A Review of Electric Motors with Soft Magnetic Composite Cores for Electric Drives. Energies 2023, 16, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerlinck, B.; De Gersem, H.; Sergeant, P. 3-D Eddy Current and Fringing-Flux Distribution in an Axial-Flux Per-manent-Magnet Synchronous Machine With Stator in Laminated Iron or SMC. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2015, 51, 8111504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Pei, X.; Yin, B.; Eastham, J.F.; Vagg, C.; Zeng, X. A Novel Double-Sided Offset Stator Axial-Flux Permanent Magnet Motor for Electric Vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2022, 13, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Hu, H.-T.; Lu, H.-L.; Yin, Y.-C.; Bu, Y.-F.; Lu, Q.-Z. Experimental Study on the Influence of Cross-Section Type of Marine Cable Conductors on the Bending Performance. China Ocean Eng. 2022, 36, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Chun, Y.D.; Han, P.W.; Kim, M.J.; Koo, D.H.; Lee, J.; Chun, J.S. Design of High Power Permanent Magnet Motor With Segment Rectangular Copper Wire and Closed Slot Opening on Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2010, 46, 3701–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergeant, P.; Vansompel, H.; Dupré, L. Influence of stator slot openings on losses and torque in axial flux PM machines. Math. Comput. Simul. 2016, 130, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, D.-W.; Hong, M.-K.; Jo, N.-R.; Jung, D.-H.; Kim, W.-H. Design of Coil Patterns for an Axial Flux Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor with PCB Stator. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 12936–12944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumi, M.; Rajasekhara, K.; Parati, D.; Bilgin, B. Manufacturing Techniques for Electric Motor Coils With Round Copper Wires. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 130212–130223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi, D.; Sankarraman, S.V.; Seyedi, S.M.; Khalesidoost, S.; Martin, N.A.; Gardner, M.C.; Toliyat, H.A. Efficient Design and Material Strategies for High Power Density Axial Flux Permanent Magnet Motors. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Nashville, TN, USA, 29 October–2 November 2023; pp. 3767–3774. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, W.; Zuo, S.; Lin, F.; Wu, S. Influence of pole and slot combinations on vibration and noise in external rotor axial flux in-wheel motors. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2017, 11, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frajnkovic, M.; Omerović, S.; Rozic, U.; Kern, J.; Connes, R.; Rener, K.; Biček, M. Structural Integrity of In-Wheel Motors. In Proceedings of the International Powertrains, Fuels & Lubricants Meeting, Heidelberg, Germany, 17–19 September 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebala, A.; Nuzzo, S.; Connor, P.H.; Volpe, G.; Gerada, C.; Galea, M. Analysis and Mitigation of AC Losses in High Performance Propulsion Motors. Machines 2022, 10, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).