Abstract

Potato peels are a waste product accounting for 15–40% of the mass of raw potatoes, depending on the processing method employed. The production of solid biofuel from potato peel was investigated in a superheated-steam fluidized bed filled with olivine sand. The co-fluidization of dried, crushed potato peels together with olivine sand was also investigated. Stable co-fluidization of olivine sand and crushed potato peels can be achieved when the mass fraction of potato peels in the fluidized bed does not exceed 3% (w/w). In a fluidized bed containing 3% % (w/w) potato peel, increasing the operational temperature of torrefaction from 200 to 300 °C with a processing duration of 30 min resulted in a 1.35-fold increase in HHV from 20.68 MJ/kg up to 27.93 MJ/kg based on ash-free dry mass. The effects of torrefaction temperature and duration on 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and furfural contents in condensable gaseous torrefaction products were studied, along with changes in the chemical composition of potato peel ash as a result of torrefaction. Furthermore, we analyzed the bed agglomeration index (BAI) predicting the possibility of agglomerate formation during combustion of torrefied potato peel in a fluidized bed and found that the probability of agglomeration may decrease along with increasing temperature and duration of the torrefaction process. Nevertheless, only the most severe torrefaction conditions of 300 °C for 30 min may completely prevent the risk of agglomerate formation during the subsequent combustion of torrefied potato peels as a solid biofuel. The proposed potato peel processing technology may be used in future frozen and fried potato factories in order to solve waste disposal issues while also reducing the costs of heat and electricity generation, as well as allowing for the recovery of high-value biochemicals from the torrefaction condensate.

Keywords:

potato peel; torrefaction; fluidized bed; olivine sand; biofuel; ash; 5-hydroxymethylfurfural; furfural 1. Introduction

Biomass-based renewable energy sources have gained significance for ensuring environmental safety and enhancing energy security. In this regard, agricultural biowaste represents a promising source for alternative fuel due to its high availability and favorable properties. Hence, research efforts are increasingly focusing on the identification of appropriate biowaste conversion routes aiming at the generation of solid biofuel with optimal properties [1].

Potato ranks fourth among agricultural crops cultivated for food production purposes [2,3,4,5]. Potato peel (PP) is a major by-product of fried potato production, which amounts to 15–40% of raw potato mass, depending on the applied processing method [6]. Currently, PP is primarily used as animal feed or for compost production. However, these approaches are inefficient, environmentally harmful, and may result in the loss of valuable components [7].

Investigating bioenergy production from biowaste is of critical importance for mitigating future energy crises associated with the depletion of fossil fuel reserves. Torrefaction may be applied as a suitable pre-treatment process for the enhancement of fuel properties of food waste prior to combustion. During torrefaction, biomass is treated in an oxygen-free atmosphere, which inhibits combustion, while still allowing thermal decomposition of biomass and increasing the higher heating value (HHV) along with carbon content, generating high-quality fuel [8] with enhanced hydrophobic properties [9]. Torrefaction may be performed in the dry medium of oxygen-free gases, or in a wet medium of water or steam. According to Funke et al. [10], the application of superheated steam as a carrier gas in wet torrefaction may enable faster and more uniform processes, whereas the separation of volatile compounds from torrefied biomass may also be facilitated [11,12].

Fluidized bed technology has been used for the torrefaction of food waste, such as tomato peels [13] and orange peels [14] using fluidized beds of inert material (quartz sand) or catalyst (γ-alumina spheres), for which the effects of the catalyst on the torrefaction process were not detected. Nevertheless, the high rate of heat transfer to biomass particles achieved in a fluidized bed of solid particles proved to be effective at reducing the duration of the torrefaction process compared with many other reactor designs.

In light of these results, this article proposes the torrefaction of PP in a superheated-steam fluidized bed. The use of superheated steam as a carrier gas instead of nitrogen, which was used in prior fluidized bed torrefaction studies, offers the following advantages:

- Rapid, uniform process and easy extraction of volatiles [11,12];

- Possible partial recovery of the heat of condensation of superheated steam, rendering the entire process more energy-efficient;

- Following biomass torrefaction, valuable chemical compounds contained in condensable gaseous products of torrefaction may be recovered in the condensate from superheated steam [11], in particular 5-hydroxymethylfurfural, which is a platform chemical for the production of a variety of high-value products, such as polymers, pharmaceuticals, solvents, and fuels [15].

A large number of studies have been devoted to biomass gasification in fluidized bed reactors using dolomite ((Ca,Mg)CO3) or olivine ((Mg,Fe)2SiO4) [16]. Olivine, a natural mineral, exhibits tar conversion activity similar to calcined dolomite, but holds the advantage of higher mechanical strength, allowing it to be used as a primary catalyst to reduce tar levels at the outlet of fluidized bed gasifiers [16]. In our study, olivine sand was considered primarily as a bed material preventing agglomerate formation during PP combustion [17].

In summary, following a biorefinery approach, the superheated steam torrefaction of potato waste in a fluidized bed may hold significant advantages, such as (1) short duration of the process; (2) on-site production and possible use of high-value solid biofuel; (3) the possibility to recycle waste steam or hot water for the steam-peeling process of potatoes; and (4) the possibility to recover high-value biochemicals from the condensate of gaseous torrefaction products.

In view of these considerations, the present study aims to investigate the torrefaction of potato peel (PP) in a superheated-steam fluidized bed filled with olivine sand as the bed material and catalyst, along with the properties of the resulting biochar for its application as solid biofuel.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Biomass Origin and Characterization

Potato peel (PP) samples were obtained from ‘WE FRY’ LLC, Lipetsk, Russia, currently the leading producer of frozen fried potatoes in Russia. A suspension containing no more than 10% of PP was collected at the facility of ‘WE FRY’ LLC. This suspension underwent mechanical dewatering in a decanter, which reduced the moisture content to 65%. The material was subsequently dried at 50 °C for 48 h, yielding final moisture content of 5.23%.

Proximate analysis of potato peel (PP) was conducted according to the standard method GOST R 56890-2016«Standard Test Methods for Analysis of Wood Fuels», 2019, Moscow, Russia, and elemental analysis was performed using a CHNS analyzer (TruSpec, LECO Corporation, St Joseph, MI, USA).

2.2. Biochar Characterization

The methods described previously were also applied for the characterization of biochar obtained from the wet torrefaction of PP.

2.3. Wet Torrefaction Process

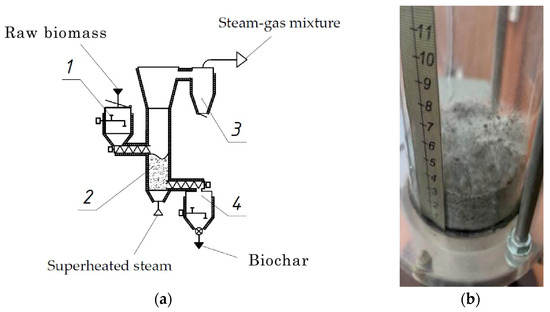

The fluidization of PP was studied in a torrefaction apparatus with a diameter of 80 mm, the walls of which were made of transparent heat-resistant glass. Steam was produced in a boiler and supplied at the bottom of the reactor through a porous gas distribution grid. The maximum airflow rate was 200 L/min, and steam pressure did not exceed 8 bar. The rate of steam flow through the apparatus was measured using a thermo-anemometer (HD 2103.2, Senseca Srl, Milan, Italy). The pressure drop in the fluidized bed was measured using a micromanometer (Testo 525, Keison products, Chelmsford, UK). The configuration of the pilot plant for the wet torrefaction of biowaste in a superheated-steam fluidized bed is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Wet torrefaction reactor for the processing of potato peel (PP): (a) diagram and (b) view of initial particle fluidization of PP–olivine sand mixture at velocity of 0.9 m/s.

The plant includes the following key components: feedstock input bunker (1), fluidized bed torrefaction reactor (2), cyclone separating gases from biochar particles exiting the reactor (3), and a bunker for biochar collection (4). Inlets for gas distribution are connected to the torrefaction reactor (2), in order to supply superheated steam under the fluidized bed. Electric heating is applied to the side walls of the reactor, ensuring that the desired temperature is maintained throughout the torrefaction process. The apparatus also comprises further components, which are not shown: a steam cooler and a superheater as well as a boiler for steam generation. The torrefaction process was carried out at temperatures of 200, 250, and 300 °C, for durations of 10, 20 and 30 min, respectively. Each torrefaction experiment was repeated three times.

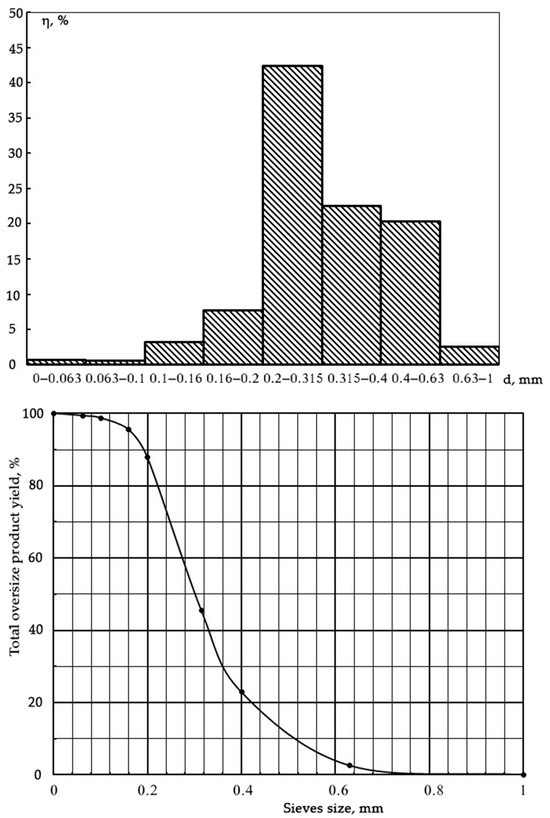

Wet torrefaction experiments were performed in fluidized bed mode. Operational conditions were optimized to achieve the fluidization of PP biomass in the reactor. For this purpose, olivine sand, acting as both the bed material and catalyst, was added at various ratios related to PP biomass, so as to determine the optimal ratio for biomass fluidization. The olivine sand had the following properties: bulk density: 1800–2000 kg/m3 and temperature of the softening point: 1450. The mineral composition (% w/w) of olivine sand was as follows: MgO 47–50, SiO2 40–42, FeO + Fe2O3 7–8, Al2O3 0.4–0.5, and CaO 0.2. The granulometric composition of olivine sand is presented in Figure 2. The fluidization process of potato peel as well as potato peel in mixture with olivine sand was investigated while maintaining a superheated water vapor temperature at 200 °C and excess pressure at 0.2 MPa.

Figure 2.

Granulometric composition of the olivine sand used as the bed material and catalyst.

Prior to initiating the torrefaction process, a layer of olivine sand was added to the reactor, and reactor walls were heated to 200 °C. The heating time was 15 min. Subsequently, the bed of olivine sand was fluidized using superheated steam, and the required amount of PP was added. During the process, the behavior of olivine sand and potato peel particles during torrefaction was visually monitored through a transparent reactor column made of borosilicate glass, and constant fluidization with the absence of channels and voids was observed.

The issue of separating torrefied PP from olivine sand was not the target of the investigation, though separation may be feasible using a cyclone separator. Furthermore, olivine sand in mixture with torrefied PP may be used again in a subsequent process of fluidized bed combustion of torrefied PP, following which olivine sand may be separated more easily from combustion ashes. The presence of olivine sand in the fluidized bed combustion of torrefied PP may also be useful in order to prevent the agglomeration of biocoal particles during the combustion process.

2.4. Process Efficiency Parameters

The mass yield (MY) of torrefied biomass relative to raw biomass was calculated as follows, allowing for the evaluation of the mass loss resulting from torrefaction:

where —weight of raw sample and —weight of torrefied sample.

Furthermore, the enhancement factor (EF) of the higher heating value (HHV) of torrefied biomass (HHV torr) in relation to raw biomass (HHV raw) was calculated as follows:

EF = (HHV torr)/(HHV raw)

Energy yield (EY) was calculated as follows, where the maximal EY value may correspond to optimal torrefaction conditions, for which a significant increase in heating value can be achieved along with limited weight loss of biomass [18]:

EY = MY × EF

2.5. Evaluation of Furfural Compounds in Torrefaction Condensate

Contents of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and furfural were determined by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography [19] on a Thermo Ultimate 3000 chromatograph, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA equipped with a Dionex DAD-3000 diode-array detector, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA and Chromeleon 7.0 Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA software.

2.6. Ash Composition and Agglomerate Formation During Combustion

The chemical composition of ash from original PP and from the resulting biochar were determined by standard methods [20,21].

According to the ash composition of raw and torrefied biomass, the probability of agglomerate formation during biomass combustion in fluidized bed can be estimated using the bed agglomeration index (BAI), under the assumption that agglomeration may occur if BAI < 0.15 [22,23,24]:

3. Results and Discussion

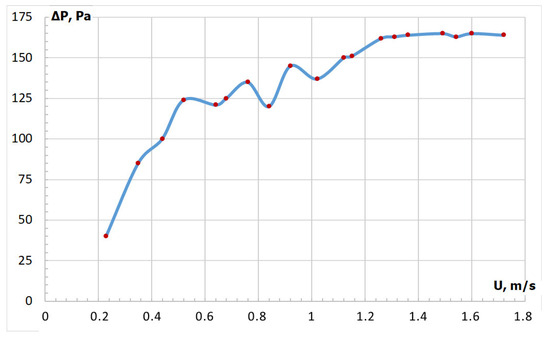

3.1. Optimal Conditions for Biomass Fluidization

Dry PP displayed a complex structure with average dimensions of 25.5 × 8.5 × 0.25 mm. Preliminary fluidization tests revealed that fluidizing PP as the sole material posed significant challenges. As the filtration rate of fluidizing water vapor supplied as superheated steam increased, a pressure drop across the bed also increased to the point where significant pressure fluctuations occurred (Figure 3), while channels and voids were forming along the bed above the gas distribution grid. Furthermore, void width increased along with further increases in filtration rate, in some cases reaching up to the entire diameter of the bed. Formed voids and channels either remained stationary or were slowly moving within the bed, acting as the primary cause of pressure drop fluctuations.

Figure 3.

Fluidization curve of pressure loss against velocity of potato peel (PP).

At a filtration velocity of 1.3 m/s, the pressure drop fluctuated and subsequently ceased. With further increases in velocity, the pressure drop remained constant, whereas the fluidized bed consisted of large numbers of microchannels that were constantly forming, collapsing, and migrating. However, at filtration velocities greater than 1.3 m/s, PP particle loss exceeded 50%. Brachi et al. [18] encountered a similar issue when attempting to process crushed tomato peels for torrefaction in a fluidized bed, and proposed the addition of quartz sand with particle size of 100–250 µm as bed material in order to ensure stable fluidization, whereas the weight fraction of crushed tomato peel particles in the fluidized bed did not exceed 2%. Nevertheless, the use of quartz sand may cause issues in the subsequent stage of combustion of biocoal obtained through torrefaction, since quartz sand particles may be carried away from the torrefaction reactor and mixed with biocoal. The combustion of a sand–biocoal mixture may result in the formation of ash-slag agglomerates disrupting the operating stability of the furnace [25]. In contrast, biomass combustion in a fluidized bed of olivine sand may be associated with significantly fewer problems related to particle agglomeration [17,26].

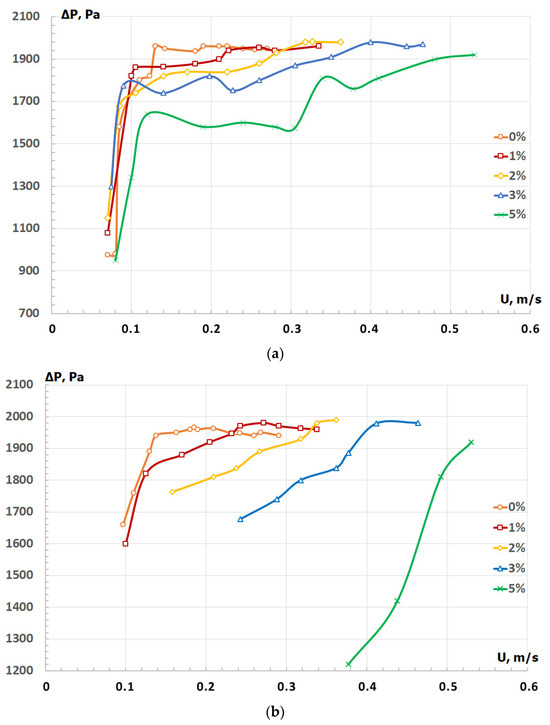

Fluidization curves of the pressure drop resulting from forward and reverse flows of an olivine sand–PP mixture with different peel mass fractions are presented in Figure 4. For mixtures with a peel fraction in the range 3–5% (w/w), pressure drop exhibited a hysteresis effect since forward and reverse curves did not coincide, with reverse curves remaining at lower levels than forward curves. On the opposite, for mixtures with PP fractions in the range 0–2% (w/w), both curves were identical. According to Rowe and Nienow [27], the arrangement of pressure drop curves observed for mixtures containing more than 3% of PP may be an indication of channel formation in the bed. Taking these results into consideration, further studies of PP torrefaction were conducted with a mass fraction of 2% PP. Under such operating conditions, the fluidized bed displayed the following parameters: minimum fluidization velocity of particles 0.25 m/s, fluidization index 1.5, and height of the layer in stationary state 40 mm.

Figure 4.

Fluidization curves of forward (a) and reverse (b) flow for mixtures of olivine sand and potato peel (PP) with different peel mass fractions (w/w).

3.2. Mass Loss in the Course of Torrefaction

Contents of C, H, N, and O in the potato peel (PP) amounted to 45.2, 5.9, 2.7, and 33.2%, respectively. Moisture, volatile matter, ash, and fixed carbon contents were 5.23, 71.24, 7.15, and 16.38, respectively. The higher heating value (HHV) on a dry and ash-free basis amounted to 20.7 MJ/kg.

Mass losses of PP following torrefaction in a superheated-steam fluidized bed with olivine sand acting as the bed material are presented in Table 1. Mass losses increased along with increasing temperature and retention time in the torrefaction reactor. Illustrating this effect, a mass loss as high as 63% was achieved at a torrefaction temperature of 300 °C and retention time of 30 min, which is more than a three-fold higher than mass loss observed at 200 °C within the same retention time. Conversely, an increase in treatment temperature from 200 to 250 °C did not lead to a significant increase in mass loss. The results of the present study in the temperature range 200–250 °C are comparable with values reported in the analysis of the literature data on the conventional dry torrefaction of lignocellulosic biomass performed by Van der Stelt et al. [28], where mass losses in the range 10–30% were reported for a treatment duration of 1 h.

Table 1.

Efficiency parameters for the wet torrefaction of potato peel (PP) in a fluidized bed with olivine sand under a superheated steam atmosphere.

The efficiency parameters of wet torrefaction are presented in Table 1. The highest energy yields (EY) within the range 88–91% were observed at temperatures of 200–250 °C combined with treatment durations of 10–20 min, whereas at these temperatures, applying a higher treatment duration of 30 min resulted in a drop of EY down to 80–81%. At the highest torrefaction temperature of 300 °C, both mass yield (MY) and energy yield (EY) declined, a trend that has also been reported in other studies [29].

Torrefaction enhances the energy density of biomass, which is crucial for the subsequent production of high-quality biofuel. As a result of the torrefaction process, the higher heating value (HHV) may increase while both mass yield (MY) and energy yield (EY) may decrease [30]. In our study, HHV increased along with increasing torrefaction temperature from 200 up to 300 °C due to higher carbon content in torrefied biomass. The reduction in MY and EY values observed at higher temperatures and retention times may be attributed to mass losses resulting from high degrees of decomposition of hemicellulose and cellulose. At higher torrefaction temperatures, MY and EY may drop as much as 30%, reducing the overall volume of the biofuel product [30]. Nevertheless, part of the lost energy may still be contained in gases and volatile compounds exiting the torrefaction reactor along with torrefied biomass, especially when higher torrefaction temperatures are applied, yet further research efforts should focus on optimizing the recovery and valorization of torrefaction gases comprising gaseous and volatile products resulting from torrefaction, and, in particular, of volatile products, which can be recovered as condensate. The obtained results are consistent with findings from other studies on the torrefaction of food waste [1]: during the torrefaction of pea shells, as temperature was increased from 250 to 450 °C, the HHV increased 1.32–2.26-fold relative to raw biomass, while energy yield (EY) decreased from 97.75% at 250 °C down to 82.73% at 450 °C. For peach pits, a similar temperature increase from 250 °C to 450 °C yielded a 1.12–1.54-fold increase in HHV, whereas EY decreased from 99.76% at 250 °C down to 59.05% at 450 °C.

3.3. Fuel Properties of Torrefied Biomass

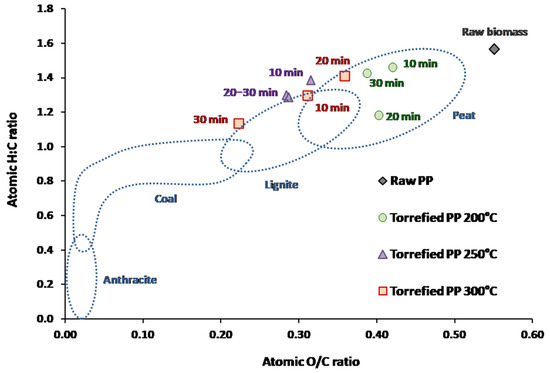

Changes in the chemical composition and calorific value of PP biochar depending on temperature and duration of the torrefaction process are presented in Table 2, revealing that C and H contents in biochar decreased along with increasing temperature and duration of torrefaction. A share of the carbon was removed from the biomass along with volatiles released during torrefaction. Similar results were observed in thermochemical treatment of sewage sludge, for which C content in biochar also decreased along with increasing temperature [31]. According to the Van Krevelen diagram of atomic H:C and O:C ratios (Figure 5), wet torrefaction at 200 °C may be sufficient to obtain peat-like characteristics, whereas wet torrefaction at 250–300 °C may be sufficient to achieve lignite-like characteristics.

Table 2.

Elemental analysis of raw and torrefied PP (Torr-PP) at different temperatures.

Figure 5.

Van Krevelen Diagram of biochar obtained from the superheated steam torrefaction of potato peel (PP) in a fluidized bed of olivine sand.

Ash compositions of raw and torrefied PP at different temperatures and durations of the torrefaction process are presented in Table 3. Since torrefied PP was not separated from olivine sand, the presence of olivine sand in the samples resulted in increased contents of SiO2, Fe2O3, MgO, and CaO within the ash fraction of torrefied PP (biocoal). Furthermore, increasing the torrefaction temperature resulted in higher K2O and Na2O contents in the torrefied PP, which may limit the formation of agglomerates during the combustion of torrefied PP as solid biofuel.

Table 3.

Ash compositions of raw and torrefied potato peel, calculated bed agglomeration index (BAI) and absolute measurement errors.

Considering that the agglomeration of biocoal particles may become an issue if the bed agglomeration index (BAI) is lower than 0.15 [22,23,24], the torrefaction of PP under the most severe processing conditions at 300 °C for 30 min may efficiently prevent the occurrence of particle agglomeration in biocoal during the subsequent process of fluidized bed combustion. Nevertheless, Nik Norizam et al. [24] argued that the BAI alone may not accurately predict interactions with silicate from the bed material. Yet, the agglomeration rate may be further affected by feedstock and process parameters, in particular the nature of bed material, minerals content of biomass, and process temperature [32,33,34].

3.4. Furfural Compounds in Torrefaction Condensate

Condensable gaseous products of torrefaction consist of a wide range of chemical compounds [14], of which furfural compounds (5-hydroxymethylfurfural and furfural) may be among the most valuable [11]. The content of furfural compounds increased along with increasing torrefaction temperature from 200 to 250 °C and subsequently decreased at the highest process temperature of 300 °C (Table 4). Furthermore, the content of furfural compounds also decreased along with increasing process duration. Optimal process conditions for maximizing yields of furfural compounds were achieved at the torrefaction temperature of 250 °C and processing duration of 10 min.

Table 4.

Contents of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (5-HMF) and furfural (FU) in condensable gaseous products of torrefaction.

4. Conclusions

The aim of torrefaction is to obtain the maximum energy yield of solid biofuel by combining both a high amount and high calorific value of torrefied biomass. Ensuring maximum yield of torrefied biomass may require the application of low torrefaction temperatures, since the generation of volatile substances during torrefaction increases at higher temperatures, corresponding to losses of significant portions of the processed biomass. Conversely, the requirement for high calorific value of torrefied biomass in view of its optimal use as solid fuel may require higher torrefaction temperatures. These two opposing constraints result in the most energy-efficient torrefaction conditions for potato peel occurring at temperatures no higher than 250 °C. Furthermore, under these conditions, condensable gaseous torrefaction products may also contain maximum amounts of valuable chemical compounds such as 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and furfural.

In the context of the fried potato industry, the flow of superheated steam exiting the reactor may be used further in the process of steam-peeling potatoes, which in turn generates potato peel residue suitable for superheated steam torrefaction, following an industrial ecology approach. Furthermore, while applying olivine sand as bed material, torrefied potato peel may still contain a share of olivine sand. Instead of attempting to remove the olivine sand, the mixture of torrefied biomass and olivine sand may be applied as solid biofuel in fluidized bed combustion, which also relies on olivine sand as bed material for the clean and efficient conversion of solid biofuel into heat energy.

The combustion of raw or torrefied potato peels in a fluidized bed may cause problems related to the agglomeration of bed particles. However, the calculated bed agglomeration index (BAI) suggests that the ash of torrefied biomass obtained from the superheated steam torrefaction of potato peel in a fluidized bed of olivine sand operated at a temperature of 300 °C and a processing time of 30 min may not form agglomerates with the inert fluidized bed material during fluidized bed combustion.

While accounting for potential synergies between processes, further research may be needed in order to assess the economic feasibility of torrefaction in a superheated steam environment in view of producing torrefied biomass (biocoal) as solid biofuel along with furfural compounds such as high-value platform chemicals. Furthermore, available concentrations and valorization pathways of further biochemicals present in torrefaction condensate should be investigated as well.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.I.; methodology, D.K. and O.M.; validation, X.G., C.E.d.F.S. and A.M.; formal analysis, S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, R.I.; writing—review and editing, M.B., D.K. and K.M.; visualization, K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was conducted with financial support from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of Russia (Agreement No. 075-15-2024-660 dated 3 September 2024, project title ‘Utilization of fried potato production waste by combining various technologies for the effective use of the obtained bioenergy, treated water, and biofertilizers’, lead organization—Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education ‘Tambov State Technical University’).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HHV | higher heating value |

| PP | potato peel |

References

- Škorjanc, A.; Gruber, S.; Rola, K.; Goričanec, D.; Urbancl, D. Advancing Energy Recovery: Evaluating Torrefaction Temperature Effects on Food Waste Properties from Fruit and Vegetable Processing. Processes 2025, 13, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, S.; Karimi, K.; Majumdar, S.; Vinod Kumar, V.; Verma, R.; Bhatia, S.K.; Kuca, K.; Esteban, J.; Kumar, D. Sustainable utilization and valorization of potato waste: State of the art, challenges, and perspectives. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 23335–23360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barampouti, E.M.; Christofi, A.; Malamis, D.; Mai, S. A sustainable approach to valorize potato peel waste towards biofuel production. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2023, 13, 8197–8208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Statistical Yearbook. World Food and Agriculture. 2021. Available online: http://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/522c9fe3-0fe2-47ea-8aac-f85bb6507776/content (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Ngobese, N.Z.; Workneh, T.S. Development of the Frozen French Fry Industry in South Africa. Am. J. Potato Res. 2017, 94, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieber, A.; Stintzing, F.C.; Carle, R. By-products of plant food processing as a source of functional compounds—Recent developments. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2001, 12, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D. Recycle technology for potato peel waste processing: A review. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 31, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M.H.; Gul, J.; Khan, M.N.A.; Naqvi, S.R.; Štěpanec, L.; Ali, I. Torrefied Biomass Quality Prediction and Optimization Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2024, 19, 100620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.U.; Sadiq, K.; Anis, M.; Hussain, G.; Usman, M.; Fouad, Y.; Mujtaba, M.A.; Fayaz, H.; Silitonga, A.S. Turning Trash into Treasure: Torrefaction of Mixed Waste for Improved Fuel Properties. A Case Study of Metropolitan City. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funke, A.; Felix Reebs, F.; Kruse, A. Experimental comparison of hydrothermal and vapothermal carbonization. Fuel Process. Technol. 2013, 115, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, B.; Kleine-Möllhoff, P.; Dalibard, A. Superheated Steam Torrefaction of Biomass Residues with Valorisation of Platform Chemicals—Part 1: Ecological Assessment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chen, X.; Qi, Z.; Wang, H.; Yang, R.; Lin, W.; Li, J.; Zhou, W.; Ronsse, F. Superheated steam as carrier gas and the sole heat source to enhance biomass torrefaction. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 331, 124955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brachi, P.; Miccio, F.; Miccio, M.; Ruoppolo, G. Torrefaction of tomato peel residues in a fluidized bed of inert particles and a fixed bed reactor. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 4858–4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brachi, P.; Chirone, R.; Miccio, F.; Miccio, M.; Ruoppolo, G. Valorization of Orange Peel Residues via Fluidized Bed Torrefaction: Comparison between Different Bed Materials. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2019, 191, 1585–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyshev, V.M.; Kravchenko, O.A.; Ananikov, V.P. Conversion of plant biomass to furan derivatives and sustainable access to a new generation of polymers, functional materials, and fuels. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2017, 86, 357–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapagnà, S.; Virginie, M.; Gallucci, K.; Courson, C.; Di Marcello, M.; Kiennemann, A.; Foscolo, P.U. Fe/olivine catalyst for biomass steam gasification: Preparation, characterization and testing at real process conditions. Catal. Today 2011, 176, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanov, O.Y.; Klimov, D.V.; Kuzmin, S.N.; Grigoriev, S.V.; Kokh-Tatarenko, V.S.; Tabet, F. Results of Testing Olivine Sand As a Filler for a Furnisher with a Fluidized Bed When Burning Sunflower Husks. Therm. Eng. 2024, 71, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brachi, P.; Miccio, F.; Miccio, M.; Ruoppolo, G. Fluidized bed Torrefaction of Industrial Tomato Peels: Set-Up of a New Batch Lab—Scale Test Rig and Preliminary Experimental Results. In Proceedings of the 22th International Conference on Fluidized Bed Conversion, Turku, Finland, 14–17 June 2015; Volume 1, pp. 438–447. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez-Servin, J.L.; Castellote, A.I.; Lopez-Sabater, C.M. Analysis of potential and free furfural compounds in milk-based formulae by high-performance liquid chromatography. Evolution during storage. J. Chromatogr. 2005, 1076, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GOST 10538—87; Solid Fuel. Methods for Determination of Chemical Composition of Ash. Standards Publishing House: Moscow, Russia, 2003.

- GOST 32977—2014; Solid Mineral Fuel. Determination of Trace Elements in Ash by Atomic Absorption Method. Standards Publishing House: Moscow, Russia, 2014.

- Bapat, D.W.; Kulkarni, S.V.; Bhandarkar, V.P. Design and Operating Experience on Fluidized Bed Boiler Burning Biomass Fuels with High Alkali Ash. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Fluidized Bed Combustion, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 11–14 May 1997; pp. 80–83. [Google Scholar]

- Vamvuka, D.; Zografos, D. Predicting the behaviour of ash from agricultural wastes during combustion. Fuel 2004, 83, 2051–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norizam, N.N.A.N.; Yang, X.; Norizam, N.N.A.N.; Ingham, D.; Szuhánszki, J.; Ma, L.; Pourkashanian, M. An improved numerical model for early detection of bed agglomeration in fluidized bed combustion. J. Energy Inst. 2025, 119, 101987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scala, F. Particle agglomeration during fluidized bed combustion: Mechanisms, early detection and possible countermeasures. Fuel Process. Technol. 2018, 171, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almark, M.; Hiltunen, M. Alternative bed materials for high alkali fuels. In Proceedings of the FBC2005 18th International Conference on Fluidized Bed Combustion, Toronto, ON, Canada, 22–25 May 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, P.N.; Nienow, A.W. Minimum fluidization velocity of multi—Component particle mixtures. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1975, 30, 1365–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Stelt, M.J.C.; Gerhauser, H.; Kiel, J.H.A.; Ptasinski, K.J. Biomass upgrading by torrefaction for the production of biofuels: A review. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 3748–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvaramini, A.; Assima, G.P.; Larachi, F. Dry torrefaction of biomass—Torrefied products and torrefaction kinetics using the distributed activation energy model. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 229, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, J.; Ohm, T.; Oh, S.C. A study on torrefaction of food waste. Fuel 2015, 40, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.M.C.; Godina, R.; Matias, J.C.D.O.; Nunes, L.J.R. Future Perspectives of Biomass Torrefaction: Review of the Current State-Of-The-Art and Research Development. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryda, L.E.; Panopoulos, K.D.; Kakaras, E. Agglomeration in fluidised bed gasification of biomass. Powder Technol. 2008, 181, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, A.; Ohman, M.; Lindberg, T.; Fredriksson, A.; Bostrom, D. Bed agglomeration characteristics in fluidized-bed combustion of biomass fuels using olivine as bed material. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 4550–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.D.; Daood, S.S.; Nimmo, W. Agglomeration and the effect of process conditions on fluidized bed combustion of biomasses with olivine and silica sand as bed materials: Pilot-scale investigation. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 142, 105806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).