Abstract

This study proposes a novel sensorless maximum power capture control strategy for variable-speed wind energy conversion systems employing a permanent magnet synchronous generator (PMSG). The proposed method integrates a fuzzy probabilistic neural network (FPNN) with an improved particle swarm optimization (IPSO) algorithm to enable adaptive learning capabilities. Additionally, support vector regression (SVR) is employed to estimate wind speed without the use of mechanical sensors, thereby enhancing system reliability and reducing maintenance requirements. A vanadium redox battery (VRB) is integrated to enhance power stability under fluctuating wind conditions. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed FPNN-IPSO-based controller achieves superior performance compared to conventional Takagi–Sugeno–Kang (TSK) fuzzy and proportional–integral (PI) controllers. Specifically, the FPNN-IPSO controller exhibits notable improvements in average power output, tracking accuracy, and overall system efficiency. The proposed method increases power output by 9.71% over the PI controller and supports Plug-and-Play operation, making it suitable for intelligent microgrid integration. This work demonstrates an effective approach for intelligent, sensorless MPC control in hybrid wind–battery microgrids.

1. Introduction

Fuzzy neural networks (FNNs), which combine the reasoning capabilities of fuzzy logic with the learning ability of neural networks, have gained increasing attention in control and modeling applications due to their ability to manage time-varying uncertainties [1,2,3]. Compared to traditional fuzzy systems or pure neural networks, FNNs offer better adaptability and robustness in nonlinear and uncertain environments. However, conventional FNNs are often inadequate for handling stochastic uncertainties, which are common in renewable energy systems [4,5,6].

To address these limitations, researchers have proposed integrating probabilistic neural networks (PNNs) with fuzzy structures. PNNs, based on Parzen window estimation and Bayes classification [7,8,9], are well-suited for managing probabilistic inputs and have been successfully applied in classification, fault detection, and nonlinear mapping tasks. A hybrid approach known as the fuzzy probabilistic neural network (FPNN) has emerged, aiming to combine the learning efficiency of FNNs and the uncertainty-handling capacity of probabilistic neural networks (PNNs) [10]. This architecture has demonstrated potential in various control scenarios involving stochastic disturbances [11,12].

In the context of wind power systems, maximum power capture (MPC) is essential for ensuring energy capture efficiency under fluctuating wind conditions. Recent studies have explored sensorless MPC techniques that eliminate the need for mechanical wind speed sensors, thereby enhancing system reliability and reducing costs [13]. Among these techniques, three main categories have been identified. The first uses polynomial approximations of the power coefficient to infer wind speed [14,15], but the associated real-time root-solving process for high-order polynomials imposes a significant computational burden. The second approach utilizes power-mapping tables and lookup mechanisms [16], which suffer from memory constraints and limited resolution. The third employs turbine torque and rotor speed estimation [17], but requires an accurate torque observer, which complicates implementation.

Given the nonlinear and uncertain characteristics of wind energy systems, heuristic optimization methods have also been employed in controller design. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), introduced by Kennedy and Eberhart, is known for its fast convergence and ease of implementation. In particular, enhancements such as time-varying acceleration coefficients (TVAC) have been proposed to improve PSO’s global search capabilities. Compared to genetic algorithms, PSO retains knowledge of previous optimal solutions, enabling more stable convergence in complex search spaces [18,19,20].

Support Vector Regression (SVR) has also been recognized as a powerful tool for nonlinear regression tasks, offering high generalization ability and robustness to local minima due to its convex optimization formulation [21]. SVR constructs a predictive model based on support vectors, making it particularly effective for wind speed estimation under sparse or noisy data conditions. When applied to wind energy systems, SVR can estimate real-time wind speed with high precision, serving as a valuable input for sensorless MPC control. In addition to wind energy, related fields have also explored advanced control ideas. For example, system-level ramp-rate control with energy storage has been used to mitigate wind power fluctuations [22]. In motor-drive applications, barrier-function-based adaptive sliding mode has been proposed to handle nonlinearities and input saturation [23]. These studies underscore the value of robust and intelligent control; however, our focus differs: we integrate SVR-based sensorless wind estimation with an IPSO-tuned FPNN in an MPC framework and coordinate a VRB for turbine-level operation.

Motivated by the limitations of conventional control methods and recent advances in hybrid learning frameworks, this paper proposes a novel MPC control strategy for a permanent magnet synchronous generator (PMSG) wind turbine, based on an FPNN controller optimized by improved PSO (IPSO), and combined with SVR-based wind speed estimation. The objective is to improve power tracking accuracy and system stability without relying on mechanical wind sensors. The main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows. First, the proposed approach integrates SVR-based sensorless wind speed estimation with an IPSO-tuned fuzzy probabilistic neural network (FPNN) within an MPC framework, which has been rarely explored in existing works. Second, this integration provides faster and more stable responses to wind fluctuations compared to conventional PI and fuzzy controllers. Third, the coordination with vanadium redox battery (VRB) storage further enhances power smoothing and frequency stability, which is particularly beneficial under rapid wind variations. Finally, a theoretical analysis is provided to show the bounded stability of the combined estimator–NN–controller system, addressing an aspect that has often been overlooked in previous studies. Simulation results demonstrate the proposed method’s effectiveness compared to conventional PI and TSK fuzzy control techniques.

2. Analytical Evaluation of the Wind Power Generation System

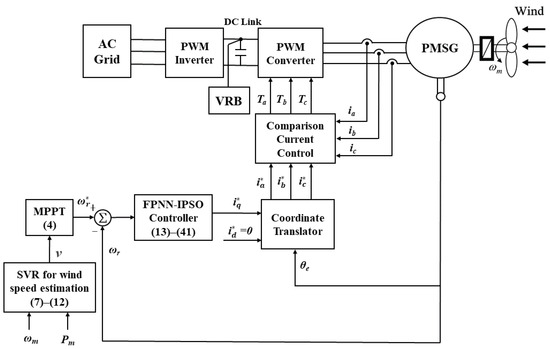

This study focuses on the control and modeling of a wind power generation system equipped with a PMSG and integrated with a vanadium redox battery (VRB) in a microgrid environment. As illustrated in Figure 1, the control system incorporates three main components: a wind speed estimator based on SVR, a speed controller for MPC, and current controllers in the synchronous reference frame. The SVR model is trained offline using historical data and applied online for real-time estimation of wind speed. This estimation serves as the basis for determining the optimal generator speed to maximize power output. The overall performance of the system is verified through a MATLAB 7.12/Simulink microgrid model, incorporating wind energy generation, VRB storage, and three-phase inverters. The dynamic behavior of the integrated system is analyzed under varying wind conditions.

Figure 1.

Control block diagram of PMSG.

2.1. Wind Turbine Characteristics and Modeling

To maximize energy extraction from wind, variable-speed wind turbines are commonly employed alongside power electronic interfaces, which decouple the generator speed from the fixed grid frequency. The aerodynamic power extracted by a wind turbine is mathematically represented as:

where ρ denotes the air density, A represents the swept area of the turbine blades, v is the wind speed, and Cp is the power coefficient. The coefficient Cp is a function of the tip-speed ratio λ and the blade pitch angle β. The tip-speed ratio is defined as:

where r denotes the blade radius and ωr represents the rotor angular speed. The power coefficient Cp generally exhibits a nonlinear relationship with the tip-speed ratio λ and blade pitch angle β and is often characterized using empirical models. Once the wind speed is estimated via the SVR module, the reference rotor speed ωr∗ required for maximum power point tracking (MPPT) can be determined as follows [24]:

Upon estimation of the wind speed using the SVR module, the reference rotor speed ωr∗ required for MPPT can be calculated as:

This control strategy ensures that the turbine operates at the optimal tip-speed ratio, thereby maximizing aerodynamic efficiency.

2.2. PMSG

The wind turbine is coupled to a three-phase PMSG, which converts the captured mechanical energy into electrical power. The relationship between the mechanical torque Tm and the electromagnetic torque Te of the generator can be described by the following equations [25,26]:

where Pm and Pe are the mechanical and electrical powers, respectively, ωe is the electrical angular frequency, and np is the number of poles. The mechanical dynamics of the PMSG can be described by:

where J is the moment of inertia. This dynamic model is crucial for the design and analysis of the speed control loop.

2.3. Principle of a Vanadium Redox Battery

Vanadium redox batteries (VRBs) are a type of flow battery that store and release energy by utilizing vanadium ions in different oxidation states as redox couples. Their unique electrochemical structure allows complete separation between energy storage capacity and power delivery capability, which makes them particularly advantageous in applications with highly variable power inputs such as wind energy systems.

The vanadium redox battery (VRB) consists of two vanadium-based electrolyte reservoirs, circulation pumps, and an electrochemical cell stack separated by an ion exchange membrane. During charging, VO2+ in the positive electrolyte is reduced to VO2+, and V3+ in the negative electrolyte is reduced to V2+; the reverse oxidation reactions occur during discharge. The membrane permits H+ ion transfer to maintain charge neutrality while preventing vanadium species crossover.

From a control perspective, the dynamic behavior of a VRB is governed by a set of electrochemical and hydraulic equations, including charge transfer kinetics, diffusion-convection dynamics, and voltage-current characteristics of the cell stack. These dynamics are important to consider when integrating VRBs with wind generation systems, particularly in microgrids where real-time power balancing is critical.

In this study, the VRB functions as a buffer to absorb the mismatch between the intermittent wind generation and the instantaneous load demand. This helps maintain system voltage and frequency stability, especially during sudden changes in wind speed or during plug-and-play events of distributed generators. Moreover, the VRB is controlled to charge when excess power is available and to discharge when the generated power falls below demand, effectively flattening the power output profile of the wind turbine. In this study, the VRB is modeled as a bounded-power buffer sized to cover the tested wind events; long-horizon energy scheduling and explicit state-of-charge management are assumed to be handled by a higher-level energy management system and are outside the scope of this controller study.

VRBs are preferred over other energy storage technologies owing to their advantageous characteristics, such as long cycle life and a high depth of discharge, and rapid dynamic response, and intrinsic safety due to the aqueous nature of its electrolytes. Furthermore, because the power and energy components are physically separated, the system can be flexibly scaled for either higher power or longer duration storage without redesigning the entire system. Given these advantages, the VRB is selected in this study as the energy storage component to enhance short-term power balance in the microgrid. Its integration strategy is discussed in the subsequent simulation model [27,28].

3. An SVR Approach for Wind Speed Estimation

Regression methods are algorithms used to estimate the relevance among system inputs and outputs based on sample or training data. Among these methods, SVR has been demonstrated to be particularly effective for power system applications [29].

Consider a set of training samples , where and represent the input and output spaces, respectively, and n denotes the number of training instances. The objective of a regression issue is to identify a functional relationship that accurately estimates unknown parameters based on observed input-output data [29,30].

The general form of the SVR estimation function can be formulated as [29]:

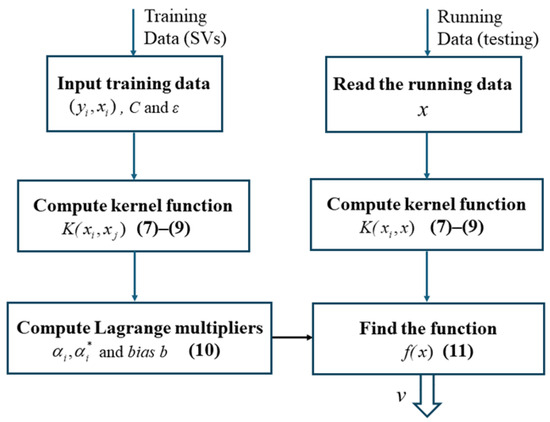

Let denote the weighting vector, b the bias term, denotes a nonlinear mapping function that transforms input data from n dimensions to a higher-dimensional feature space, as illustrated in Figure 2. The dot product symbol expresses the inner product in this feature space. To determine the optimal weighting vector , the cost function must be minimized [31,32,33]:

subject to

where denotes the permissible error margin and serves as a user-specified regularization parameter that regulates the trade-off between the complexity of the model and the tolerance for training errors. To allow for deviations beyond the ε-insensitive zone in the training data, slack variables and are introduced.

Figure 2.

Flow Diagram of the Wind Speed Estimation Procedure.

The constraints incorporate , which determines the tolerance margin for estimation errors within the -insensitive zone. This parameter significantly impacts the quantity of support vectors involved in constructing the regression model. Specifically, as increases, the number of selected support vectors tends to decrease, resulting in a sparser model representation. With a properly selected value of , a trade-off can be implemented among minimizing the training error and decreasing the model complexity, as captured by the regularization term .

The key approach to satisfying these constraints is to formulate a Lagrangian function based on the objective function presented in Equation (8) and maximizing the resulting function with respect to the dual variables and . Applied to our optimization problem, the Lagrangian for (8) is

subjected to . At this stage, Equation (8) is subject to minimization with respect to the primal variables (, b, , and ), while simultaneously being maximized with respect to the Lagrange multipliers and . So, by taking the partial derivatives of the Lagrangian function L with respect to the primal variables and equating each to zero, the conditions for optimality are obtained, the necessary conditions for optimality are obtained [34,35].

Equation (9) can be converted into its corresponding dual formulation, and the solution to this dual problem is given by:

which is subject to

In Equation (12), the bias term b is formulated based on the Lagrange multipliers and the kernel function.

SVR is adopted for the wind-speed estimator because it offers a convex empirical-risk formulation with a unique global optimum and stable training, while providing nonlinear approximation via the kernel map and robustness via the ε-insensitive loss. This property is attractive under limited and noisy site data and aligns with the offline-training/online-inference workflow of the sensorless MPC loop. In practice, an RBF kernel is used, and the hyper-parameters (C, ε, γ) are selected offline by nested cross-validation to balance training error and model sparsity (i.e., the number of support vectors), ensuring low-latency estimation during operation.

Compared with sequence models such as LSTMs or deeper neural networks, the SVR estimator does not require large labeled sequences or elaborate regularization schedules to prevent overfitting, and it avoids the additional inference latency and memory footprint associated with recurrent architectures in embedded controllers. Relative to Gaussian Processes, SVR scales more favorably in training and memory and does not suffer from cubic complexity, which facilitates periodic retraining when new batches of site data become available.

To clarify generalization across varying wind profiles and unseen geographies, input signals are standardized, and the validation protocol holds out entire wind segments (and, when available, entire sites) during hyper-parameter tuning to avoid information leakage. This split strategy, together with kernel regularization, provides robustness to changes in turbulence intensity and air-density conditions. The estimator is trained offline from historical measurements and applied online in the MPC block, so the controller benefits from stable, low-variance predictions while preserving real-time feasibility. No new experiments are introduced; these additions state the modeling choices and validation protocol explicitly.

At this stage, all parameters in Equation (11) have been computed offline. Therefore, Equation (11) is employed online to estimate the output f(x) for any given input x (wind speed), as illustrated in Figure 2.

4. Proposed FPNN with IPSO Control System

The FPNN controller demonstrates robust performance in handling system uncertainties, owing to its inherent parallel processing structure and adaptive online learning mechanism. Furthermore, subsequent sections elaborate on the network architecture, the online learning algorithm, and the convergence analysis of the FPNN.

4.1. Fuzzy Probabilistic Neural Network (FPNN)

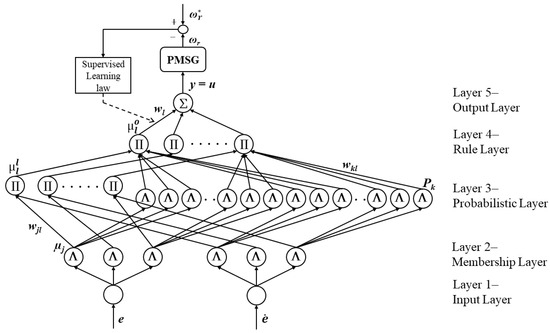

The proposed fuzzy probabilistic neural network (FPNN) consists of five layers, each designed to perform a specific signal transformation toward the final control output in Figure 3. In addition, the subsequent sections provide a detailed exposition of the signal propagation process and the principal role of each layer within the network architecture.

Figure 3.

Network structure of FPNN.

(1) Layer1—Input layer: The inputs and outputs of the nodes are defined as follows:

where denotes the ith input to the input layer, and N indicates the Nth iteration. In this paper, the inputs of the FPNN are and , which represent the tracking error and its derivative, respectively.

(2) Layer2—Membership layer: In the FPNN architecture, the receptive field is modeled using a Gaussian function. The equations of Gaussian function are defined by:

where is the output of the jth node corresponding to the ith input variable; denotes the center of the Gaussian function at the jth node associated with the ith input variable, and represents its corresponding width.

(3) Layer3—Probabilistic layer: The receptive field function is typically represented by a Gaussian function, and its mathematical formulation is given by:

where denotes the output of the kth node corresponding to the jth input variable; is the center of the Gaussian function, and is the base of the Gaussian function.

(4) Layer4—Rule layer: Each node corresponds to a specific rule within the knowledge base. In accordance with the Mamdani inference mechanism, each node utilizes a t-norm operation to generate an inference set based on its associated fuzzy rule, as expressed in Equation (20). Subsequently, probabilistic information is handled using Bayes’ theorem [7,8], under the assumption that the fuzzy membership grades constitute independent variables, as shown in Equation (21). Based on this formulation, the input and output of each node in this layer are defined as follows:

where and are the input of rule layer; and are set to one; is the output of the rule layer.

(5) Layer5—Output layer: The node outputs are expressed as:

where denotes the output of the FPNN, which simultaneously functions as the control effort of the proposed controller, and indicates the connective weight among the Layer 4 and the Layer 5.

4.2. Online Supervised Learning and Training Process

The learning mechanism of the FPNN is fundamentally based on the recursive computation of the gradient vector, wherein each component corresponds to the partial derivative of a predefined energy function with respect to an individual network parameter. To derive the online learning algorithm within a supervised gradient descent framework, the error function E is initially defined as follows:

Subsequently, the learning algorithm is detailed as follows:

- (1)

- Layer5: The propagated error term is defined as follows:

- (2)

- Layer4: The error term to be propagated is given:

- (3)

- Layer2: The following expression defines the error term that is propagated through the network:

By applying the chain rule, the update equations for the center and width of the membership function are derived as follows:

where the factors and are the learning rates. The parameter will be optimized using the IPSO algorithm. The center and base of the membership function are updated according to the following formula:

Furthermore, the exact computation of the system Jacobian, , is challenging due to the unknown dynamics of the control system. To address this issue, a delta adaptation law is employed, as described below [36]:

4.3. Convergence Analysis

To analyze the stability of the control system, a candidate Lyapunov function —serving as an energy-like measure for the tracking error—is initially proposed. To ensure asymptotic stability, the weights of the neural network are adaptively adjusted via a backpropagation algorithm, propagating error signals from the output layer toward the input layer. This adaptive update scheme is designed such that the time derivative of the Lyapunov function remains negative semi-definite . According to Lyapunov’s direct method [37], if the Lyapunov function is positive definite and its time derivative is negative semi-definite , then the function qualifies as a valid Lyapunov candidate for the error dynamics. Consequently, the output tracking error of the FPNN asymptotically converges to zero as time approaches infinity. This theoretical framework ensures both the stability of the closed-loop control system and the convergence of the neural network learning process.

4.4. Composite Stability of Estimator–NN–MPC

Closed-loop behavior is analyzed by considering the interconnection of three components: the turbine–converter dynamics regulated by MPC, the FPNN adaptation, and the SVR-based wind-speed estimator. The tracking error is defined as with (, ) used as error signals in the controller. Let θ collect the FPNN parameters (rule weights and membership parameters) and let denote the parameter error relative to an ideal value . The estimator error is .

Consider the augmented Lyapunov candidate:

where P 0 is a symmetric positive-definite matrix associated with the nominal MPC error dynamics, Γ 0 is the adaptation gain matrix, and α > 0 is a weighting scalar. Under standard MPC feasibility and terminal-set conditions (positive-definite stage cost and a stabilizing terminal law), the nominal plant contribution yields a decrease in the form for some Q 0. Q is symmetric positive definite. The FPNN adaptation (as defined earlier in the learning/update equations) employs projection and leakage so that cross terms between e and cancel in the Lyapunov derivative, while the approximation residual is uniformly bounded by . The SVR module is treated as an input-to-state stable (ISS) estimator with respect to measurement noise and turbulence, yielding a bounded estimation error . The VRB coordination appears in the prediction model as a bounded actuator-side disturbance with magnitude at most .

By Young’s inequality, these contributions lead to

where depends on Q, η > 0 is the leakage rate in the adaptation law, and c1, c2, c3 >0 are constants arising from bounding the residual, estimation error, and disturbance terms. Hence, the interconnection of MPC, FPNN adaptation, and SVR estimation is uniformly ultimately bounded (UUB). The ultimate bound shrinks with the approximation and estimation errors. Modeling the VRB influence as a bounded disturbance and adopting the usual robust margin in MPC (e.g., constraint tightening or tube MPC) yields ISS of the closed loop with respect to that disturbance. For discrete-time implementations, the same structure holds with ΔV in place of . A detailed derivation is given in Appendix A.

4.5. Adjustment of Learning Rates Using IPSO

To further enhance the online learning capability of the FPNN, a hybrid optimization technique—IPSO, which incorporates elements of genetic algorithms and time-varying particle swarm optimization—is employed in this study to tune the learning rates , and . In the IPSO algorithm, each particle updates its position by leveraging both its individual experience and the collective experiences of its neighbors. This update process accounts for the particle’s current velocity and position, as well as the best positions previously identified by itself and its neighboring particles [38].

Two pseudo-random sequences, and , are employed to simulate the stochastic behavior of the algorithm. For each dimension d, , represent the current position and the personal best position of the particle, respectively. The velocity update rule, incorporating these elements, is defined in Equation (33). In addition, the inertia weight w = 0 is set. IPSO can reduce the parameter settings. The acceleration coefficients f1 and f2 can be modified by the following Equations (34) and (35) [39,40,41]. These parameters are referred to as time-varying acceleration coefficients.

Here, and represent the current velocity and position of the particle, respectively, while Nmax denotes the maximum number of iterations. and are the initial parameters setting. and are the final parameters setting.

Step 1: Definition of Basic Conditions

With for learning rates , the population size is defined as P = 15. Each particle is defined with a dimensionality of d = 3. The parameters are optimized within predefined lower and upper bounds.

Step 2: Initialization of Position and Velocity

Each particle’s initial position and velocity are randomly assigned within the boundaries of the defined search domain. Each particle’s initial pbest is assigned as its current position, and the gbest is determined by selecting the best pbest among the entire group. The are randomly generated by

where represents a value sampled from a uniform distribution within the lower and upper bounds of the learning rate, and , respectively.

Step 3: Formulation of the fitness function

For each vector , a corresponding fitness value must be assigned and evaluated. In this study, an appropriate fitness function is formulated to evaluate the fitness value, as defined below:

where FIT is the fitness value, and abs(·) is the absolute function; 0.1 is added in the dominant part to avoid approaching infinity.

Step 4: Selection of pbest and gbests

Each particle retains its own fitness value and identifies the highest value encountered thus far as . And the maximum vector in the population is reached. Furthermore, in the first iteration, each particle is initially assigned to , and the particle with the highest fitness value among all pbest values is designated as the global best gbest.

Step 5: Check the gbest for updates

If the position of the gbest particle remains unchanged over a predefined number of iterations, a crossover operation is applied between gbest and a chromosome from the Genetic Algorithm (GA). The reorganization of position and velocity are

where f3 is the acceleration factor, and rand() represents a random number uniformly distributed in the interval [0, 1]. lparent and lchild are parent and child generation of position. sparent and schild are parent and child generation of velocity. λ represents the interpolation factor between the parent and offspring generations, defined as a random number uniformly distributed in the range [0, 1].

Step 6: Update position and velocity

The updated velocity is then incorporated into the current position of the particle to compute its subsequent position, as described by Equations (33) and (36).

Step 7: Convergence check

Steps 3 to 6 are iteratively executed until a significant improvement in the gbest fitness value is observed, or a predefined maximum number of generations is reached. The final and highest fitness value obtained is considered the optimal learning rate for the FPNN.

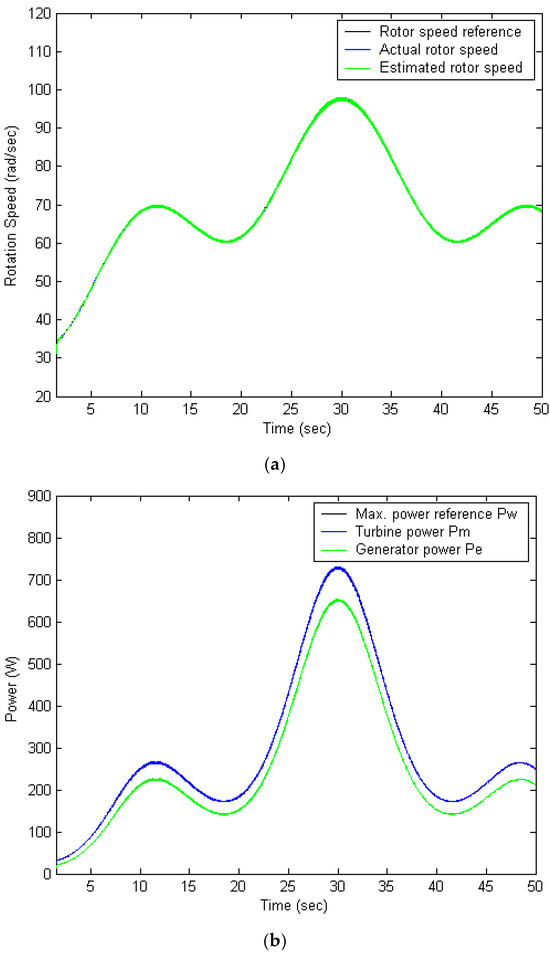

5. Case Studies and Simulation Results

The performance of the proposed FPNN–IPSO controller is assessed and benchmarked against the TSK fuzzy controller [3] and a conventional PI controller. All three control strategies—FPNN–IPSO, TSK fuzzy, and PI—were implemented and evaluated in simulation across three case studies. Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 illustrate the comparative results, and Table 1 summarizes the main indices. Each case study uses a rapidly varying sinusoidal wind profile with a 5 ms sampling interval for wind-speed measurements. The studies also assess the effectiveness of the VRB as a buffer for stabilizing the wind-energy output. With one inverter in the microgrid under control, the PCC voltage and system frequency remain within prescribed limits, and the inverter power is kept at its rated operating point; in other words, the AC microgrid remains robustly stable under plug-and-play operation of the WTG. The average power obtained with the PI controller is compared with that of the FPNN–IPSO and TSK fuzzy controllers. Accordingly, the contribution of the storage is discussed qualitatively from the time-domain waveforms in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6—namely, the flattening of the output-power trajectory and the maintenance of PCC voltage and frequency within the prescribed bounds—while keeping the study focused on controller-level dynamics.

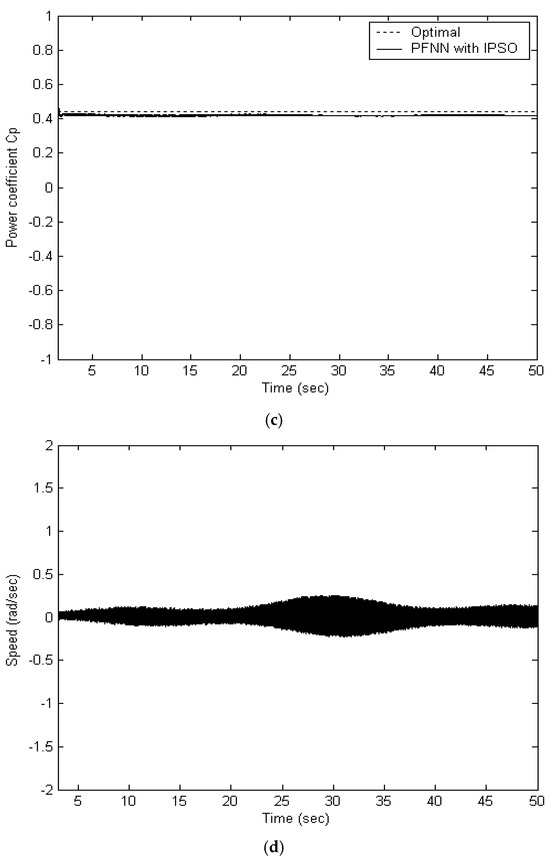

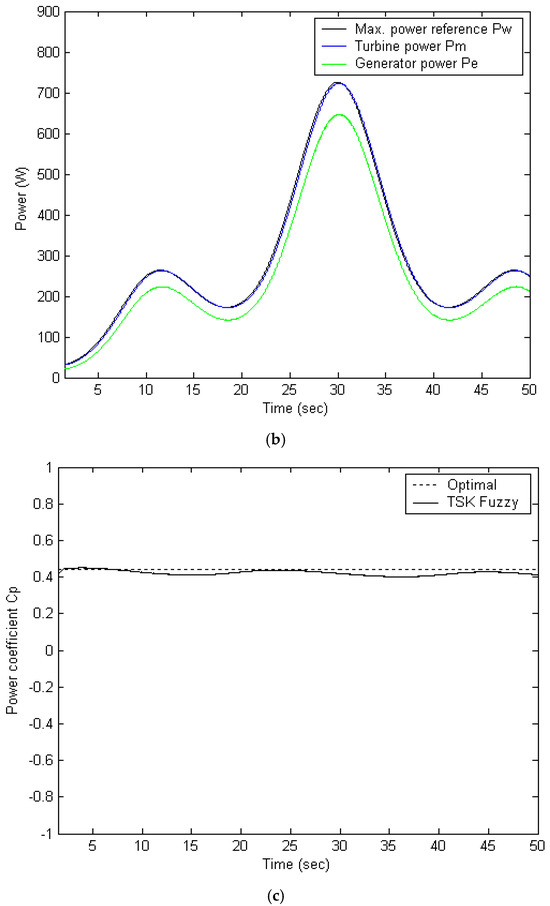

Figure 4.

Illustrates the simulation outcomes of the FPNN regulated by the IPSO-based control strategy: (a) tracking performance of the wind speed profile, (b) effectiveness of maximum power point tracking, (c) variation in the power coefficient Cp, (d) rotor speed tracking error over time.

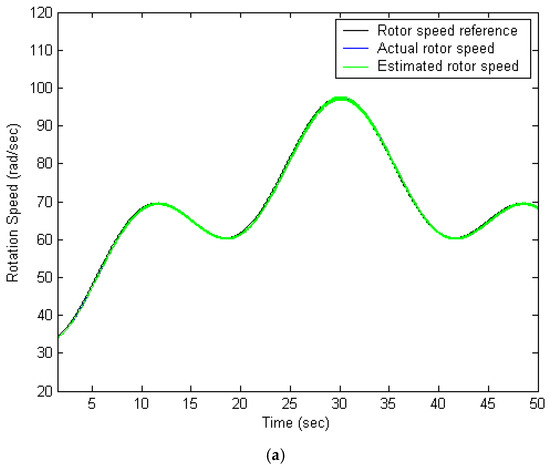

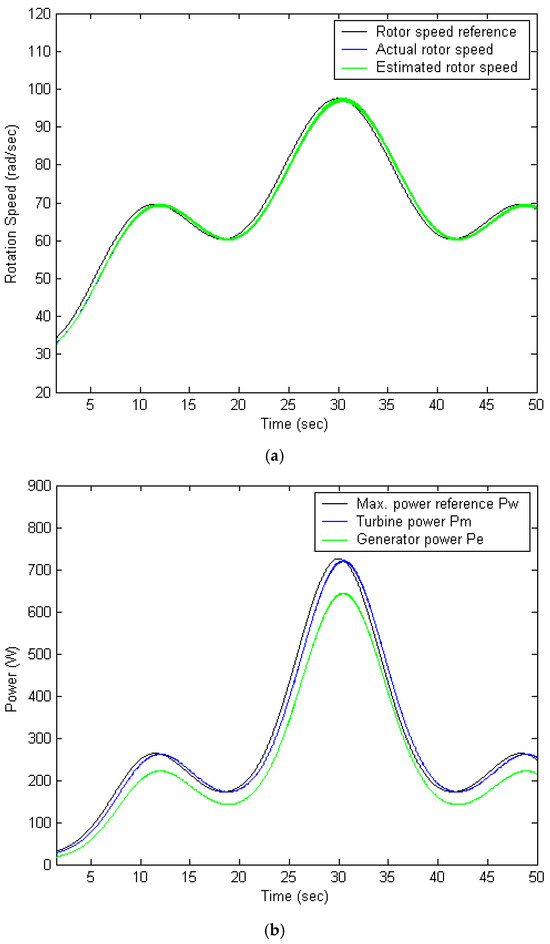

Figure 5.

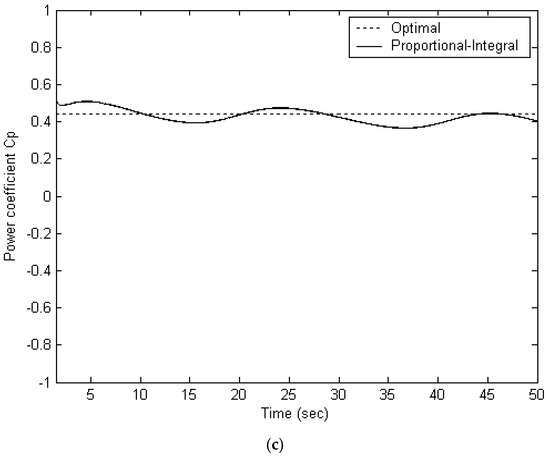

Illustrates the simulation outcomes of the TSK fuzzy control strategy: (a) tracking performance of the wind speed profile, (b) effectiveness of maximum power point tracking, (c) variation in the power coefficient Cp.

Figure 6.

Illustrates the simulation outcomes of the PI control strategy: (a) tracking performance of the wind speed profile, (b) effectiveness of maximum power point tracking, (c) variation in the power coefficient Cp.

The wind turbine generator system employed in the simulation is characterized by the following parameters:

5.1. FPNN with IPSO Algorithm

The proposed FPNN-IPSO controller is evaluated in the configuration illustrated in Figure 1. As shown in Figure 4a, the shaft speed successfully tracks the maximum power point at or below the rated generator speed, demonstrating effective performance. The validation of the MPPT capability is presented in Figure 4b, which also includes the wind speed profile and the dynamic discrepancy between the turbine power and generator power. Figure 4c displays the power coefficient, which remains close to its optimal value throughout the entire wind speed profile, indicating efficient MPPT operation. The SVR-based speed tracking mechanism accurately follows the actual speed with minimal deviation across the wind profile. Figure 4d illustrates the speed tracking error, which is approximately 0.25 rad/s. The average power output achieved is 271 W, representing a 9.71% improvement over the conventional PI controller. These results confirm that the proposed controller delivers superior transient and steady-state performance, as evidenced by the data presented in Figure 4.

5.2. TSK Fuzzy-Based Algorithm

By replacing the FPNN-IPSO controller with a TSK fuzzy-based algorithm, the simulation results illustrated in Figure 5 indicate an average power output of 259 W over a 50 sec interval, corresponding to a 4.85% improvement compared to the conventional PI controller. The power coefficient remains approximately at 0.4412. As depicted in Figure 5a, the shaft speed effectively tracks the maximum power point while operating below the rated generator speed. Figure 5b presents the validation of the maximum power tracking control, while Figure 5c displays the power coefficient, confirming the satisfactory performance of the TSK fuzzy-based controller in maintaining efficient power conversion. The results in Figure 5 show that magnitude of the rotation speed and power coefficient are relatively large. Compared to the PI controller, the TSK fuzzy controller offers improved transient and steady-state response, although it remains slightly less accurate than the proposed method.

5.3. PI Controller

When the FPNN-IPSO controller is replaced with the conventional PI controller, the simulation results are shown in Figure 6. The average power output achieved over the same 50 s period is 247 W. As illustrated in Figure 6a, the shaft speed demonstrates the system’s response under PI control, while Figure 6b provides the validation of the MPPT control. Figure 6c displays the power coefficient, which consistently remains close to the optimal value of approximately 0.4412. These results indicate that while the PI controller maintains reasonably effective tracking performance, its efficiency is comparatively lower than that of the FPNN-IPSO and TSK fuzzy-based controllers. The conventional PI controller achieves acceptable transient behavior; however, its closed-loop settling time is significantly longer compared to the FPNN with IPSO and TSK fuzzy methods.

5.4. Performance Comparison

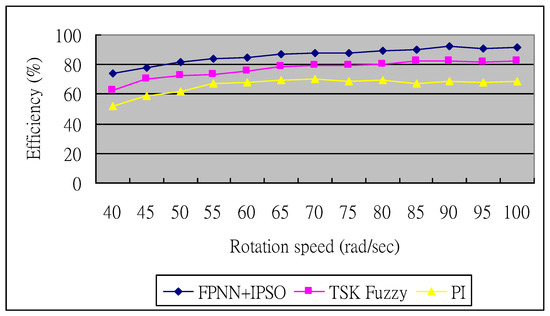

The simulation-based performance comparison of various control strategies underscores the significance of MPPT across a wide range of wind speeds, as summarized in Table 1. This table presents a comparative analysis including average output power, the maximum error in the power coefficient, and the percentage increase in power achieved by each method. The proposed control algorithm demonstrates superior performance compared to existing methods reported in [17,28,42,43]. For instance, the maximum error in the power coefficient reaches approximately 23% in [17], while the maximum power deviation in [28] is around 7%. In contrast, the proposed method achieves a marked reduction in these errors, indicating enhanced tracking capability and control precision. Figure 7 illustrates the efficiency performance of the three control algorithms. With the implementation of the proposed strategy, the generator efficiency—defined from mechanical input to AC output—exceeds 86.11%. Additionally, when accounting for converter losses, the overall system efficiency—from mechanical input to DC output—remains above 81% under medium to high wind speed conditions. These results confirm that each system component can independently respond to dynamic conditions using a decentralized Plug-and-Play strategy, ensuring coordinated and stable operation of the microgrid.

Table 1.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Different Control Strategies.

Table 1.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Different Control Strategies.

| Method | Average Power (Pm) (W) | Increasing Power Percentage (%) | Max. Power Coefficient (%) | Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPNN with IPSO method | 271 | 9.71 | 2.53 | 86.11 |

| [43] | 267 | 8.09 | 2.57 | 85 |

| TSK Fuzzy method | 259 | 4.85 | 9.33 | 76.97 |

| PI method | 247 | reference | 13.32 | 66.03 |

Figure 7.

Simulation efficiency performance.

6. Conclusions

This study proposes and investigates three distinct control algorithms specifically developed for a PMSG integrated within a variable-speed WECS. Under a varying wind speed profile, the proposed system is capable of performing MPPT. The speed control mechanism generates the generator torque reference, which is executed through an inner-loop current controller. Notably, all three MPPT algorithms proposed in this work are implemented without the use of wind speed sensors.

Among the methods evaluated, the conventional proportional–integral (PI) controller is shown to operate near the optimal point under certain conditions. However, the PI-based approach may exhibit limitations in systems characterized by strong nonlinearities or rapidly changing reference trajectories, resulting in suboptimal control performance.

Simulation results validate the efficacy of the proposed FPNN combined with IPSO control scheme in both trajectory forecasting and real-time power regulation. Experimental verification further demonstrates that the FPNN-IPSO-based MPPT strategy demonstrates high accuracy in both trajectory prediction and target tracking, ensuring precise alignment with the optimal operating point under varying wind conditions. Furthermore, the control strategy effectively regulates power output to meet load demands and enhance system stability. Additionally, it provides coordinated control across multiple components, contributing to microgrid optimization. The proposed method exhibits robust dynamic performance and maintains system stability even with rapidly varying wind speeds, thereby ensuring reliable operation under diverse operating conditions. In future work, we will take noisy data settings into account when training the SVR that is used to estimate wind speed.

Author Contributions

K.-H.L. writing—original draft preparation, review and prepared the revised version. C.-M.H. contributed to the project administration, modeling investigation, methodology and prepared the original draft of the manuscript. F.-S.C. the modeling investigation, conceptualization and application of methodology. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was supported by the Fujian Provincial Education Research Projects for Young and Middle-Aged Teachers (No. JAT241182) and the Technology Innovation Team of Minnan University of Science and Technology (No. 23XTD112).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Composite Stability Proof

Appendix A.1. Error Model

Let . The prediction model used by MPC includes bounded exogenous terms d from grid/VRB interaction, with . The unknown nonlinear map is approximated by the FPNN with residual ε, . The SVR estimator produces and the estimation error is .

Appendix A.2. Lyapunov Candidate

Choose

Appendix A.3. Derivative Bound for the Plant Part

Under the standard MPC assumptions (positive-definite stage cost, feasible terminal set and terminal controller), the nominal error dynamics satisfy a Lyapunov inequality for some Q0.

Appendix A.4. Neural Adaptation Term

The parameter update employs a projection operator onto a compact set and a leakage term,

where is a standard regressor built from . Projection guarantees the boundedness of ; the leakage term yields

The cross term between e and is canceled by construction of , and the residual approximation error ε is uniformly bounded by .

Appendix A.5. Estimator and Disturbance Contributions

Treating the SVR estimator as ISS with respect to measurement noise/turbulence gives a bounded error . Bounded VRB/grid effects enter as d, . Using Young’s inequality,

for some λ > 0, c1,2,3 > 0, and an appropriate matrix S derived from the linearized error dynamics.

Appendix A.6. Conclusions

Selecting yields

which proves the UUB status of (e, ). The closed loop is ISS with respect to the bounded disturbance d; in an MPC implementation, this is ensured by standard constraint tightening/tube design. For a sampled data controller, the same structure holds with ΔV in place of .

References

- Klement, E.P.; Mesiar, R.; Pap, E. A universal integral as common frame for choquet and Sugeno integral. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2010, 18, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Wang, M.H.; Hagras, H. A type-2 fuzzy ontology and its application to personal diabetic-diet recommendation. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2010, 18, 374–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Park, J.B.; Joo, Y.H. Improvement on nonquadratic stabilization of discrete-time Takagi-Sugeno fuzzy systems: Multiple parameterization approach. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2010, 18, 425–429. [Google Scholar]

- Sutikno, T.; Subrata, A.C.; Elkhateb, A. Evaluation of Fuzzy Membership Function Effects for Maximum Power Point Tracking Technique of Photovoltaic System. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 109157–109165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Sun, C.; Wu, X.; Yang, H.; Qiao, J. Self-Organizing Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Neural Network Using Information Aggregation Method. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 6428–6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.S.; Wu, C.H. Robust optimal reference-tracking design method for stochastic synthetic biology systems: T-S fuzzy approach. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2010, 18, 1144–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parzen, E. On estimation of a probability density function and mode. Ann. Math. Statist. 1962, 33, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.; Chang, J.H. Robust Localization Method Based on Non-Parametric Probability Density Estimation. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 61468–61480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiridi, M.; Kargas, N.; Sidiropoulos, N.D. Low-Rank Characteristic Tensor Density Estimation Part I: Foundations. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2022, 70, 2654–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Integral Aggregations of Continuous Probabilistic Hesitant Fuzzy Sets. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2022, 30, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Ying, H. Modeling and Control of Probabilistic Fuzzy Discrete Event Systems. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2022, 6, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Bi, L.; Yang, Z.; Fei, W. A Novel Control Framework of Brain-Controlled Vehicle Based on Fuzzy Logic and Model Predictive Control. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 21777–21789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzayed, M.; Farajpour, Y.; Chaoui, H. Simplified Current Sensorless Maximum Power Extraction for Wind Energy Conversion Systems. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 104686–104695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Li, Z.; Xu, Y.; Guo, X.; Ding, Z. Surrogate-Assisted Cooperation Control of Network-Connected Doubly Fed Induction Generator Wind Farm with Maximized Reactive Power Capacity. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdy, F.E.Z.; Hasanien, H.M.; Sabry, W.; Ullah, Z.; Alkuhayli, A.; Yakout, A.H. Mountain Gazelle Algorithm-Based Optimal Control Strategy for Improving LVRT Capability of Grid-Tied Wind Power Stations. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 129479–129492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, R.I.; Ronilaya, F.; Rifa’i, M.; Jasa, L.; Priyadi, A.; Mauridhi Hery, P. Sensorless Optimum Power Extraction for Small Scale Stand Alone Wind Turbine Based on Fuzzy Controller. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Applied Electromagnetic Technology (AEMT), Lombok, Indonesia, 9–12 April 2018; pp. 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto, S.; Nakayama, H.; Sanada, M.; Takeda, Y. Sensorless output maximization control for variable-speed wind generation system using IPMSG. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2005, 41, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid Hamad, Y.; Nasser Hussain, A.; Lafta, Y.N.; Al-Naji, A.; Chahl, J. Multi-Objective Optimization of Renewable Distributed Generation Placement and Sizing for Technical and Economic Benefits Improvement in Distribution System. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 164226–164247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, L.K.; Verma, M.K.; Joshi, P. Novel Real Valued Improved Coral-Reef Optimization Algorithm for Optimal Integration of Classified Distributed Generators. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 80623–80638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Cruz, R.; Sanchez, E.N.; Ornelas-Tellez, F.; Loukianov, A.G. Particle Swarm Optimization for Discrete-Time Inverse Optimal Control of a Doubly Fed Induction Generator. IEEE Trans. Power Cybern. 2013, 43, 1698–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.N.; Li, Y.; Shao, Y.H. Large-Scale Structured Output Classification via Multiple Structured Support Vector Machine by Splitting. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2024, 8, 2112–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Baldick, R. Ramp Event Forecast Based Wind Power Ramp Control with Energy Storage System. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 31, 1831–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, K.; Zheng, J.; Tang, R.; Li, X.; Man, Z.; Liang, B. Barrier Function Based Adaptive Sliding Mode Control for Uncertain Systems with Input Saturation. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2022, 27, 4258–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.M.; Chen, C.H.; Tu, C.S. Maximum Power Point Tracking-Based Control Algorithm for PMSG Wind Generation System without Mechanical Sensors. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 69, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wai, R.J.; Lin, C.Y.; Chang, Y.R. Novel maximum-power-extraction algorithm for PMSG wind generation system. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2007, 1, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutari, H.; Ibrahim, T.; Nor, N.B.M.; Abdulrab, H.Q.A.; Saad, N.; Al-Tashi, Q. Coordination of Enhanced Control Schemes for Optimal Operation and Ancillary Services of Grid-Tied VSWT System. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 43520–43535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, A.; Pugach, M.; Polyakov, A.; Osinenko, P.; Bolychev, A.; Terzija, V.; Parsegov, S. Optimal Flow Factor Determination in Vanadium Redox Flow Battery Control. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 19277–19284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Crow, M.L.; Elmore, A.C. A Balance-of-Plant Vanadium Redox Battery System Model. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2015, 6, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.R.; Seok, J.K.; Lee, D.C. Mechanical parameter identification of servo systems using robust support vector regression. IEEE PESC Conf. 2004, 5, 3425–3430. [Google Scholar]

- Aghakashkooli, M.R.; Jovanovic, M.G. A Sensorless Parameter Independent Controller for Brushless Doubly-Fed Reluctance Wind Generators. In Proceedings of the IEEE 14th International Conference on Power Electronics and Drive Systems (PEDS) 2023, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–10 August 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yu, H. Three-phase induction motor operation trend prediction using support vector regression for condition-based maintenance. In Proceedings of the World Congress on intelligent control and automation (WCICA) 2006, Dalian, China, 21–23 June 2006; Volume 2, pp. 7878–7881. [Google Scholar]

- Asaly, S.; Gottlieb, L.A.; Reuveni, Y. Using Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Ionospheric Total Electron Content (TEC) Data for Solar Flare Predictions. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 1469–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatrabgoun, O.; Daneshkhah, A.; Esmaeilbeigi, M.; Sohrabi Safa, N.; Alenezi, A.H.; Rahman, A. Predicting Primary Sequence-Based Protein-Protein Interactions Using a Mercer Series Representation of Nonlinear Support Vector Machine. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 124345–124354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkassky, V.; Miller, F. Learning from Data Concept Theory and Methods; John. Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, Y.; Liu, W.; Shi, Y.; Li, J. Semi-Supervised Concept Learning by Concept-Cognitive Learning and Concept Space. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 34, 2429–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.J.; Wai, R.J.; Lee, C.C. Fuzzy neural network position controller for ultrasonic motor drive using push-pull DC-DC converter. IET Proc. Control Theory Appl. 1999, 146, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Wu, J.; Wang, H.; Zheng, H. Dynamic Optimization of Rotor-Side PI Controller Parameters for Doubly-Fed Wind Turbines Based on Improved Recurrent Neural Networks Under Wind Speed Fluctuations. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 102713–102726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.; Rehman, O.U.; Rehman, S.U.; Ullah, S.; Waqas, M.; Zhu, R. A Novel Quantum Inspired Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm for Electromagnetic Applications. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 21909–21916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, S.; Srivastava, L.; Pandit, M. Optimal location and sizing of STATCOM for voltage security enhancement using PSO-TVAC. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Power and Energy Systems, Chennai, India, 22–24 December 2011; pp. 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Le, K.H.; Cao, M.T.; Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, T.H.; Le, M.V. Determining Optimal Location and Sizing of STATCOM Based on PSO Algorithm and Designing Its Online ANFIS Controller for Power System Voltage Stability Enhancement. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Green Technology and Sustainable Development (GTSD) 2020, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 27–28 November 2020; pp. 272–279. [Google Scholar]

- Munnu, M.K.; Choudhary, J. Optimal Placement and Sizing of Custom Power Devices using PSO and APSO Optimization in Radial Distribution Network. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Energy, Power and Environment: Towards Flexible Green Energy Technologies (ICEPE) 2023, Shillong, India, 15–17 June 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, R.M.; Mulla, M.A. Rotor Position-Sensorless Algorithms for Direct Power Control of Rotor-Tied DFIG. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 6213–6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.M.; Hong, C.M.; Ou, T.C.; Chiu, T.M. Hybrid Intelligent Control of PMSG Wind Generation System Using Pitch Angle Control with RBFN. Energy Convers. Manag. 2011, 52, 1244–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).