Abstract

The oil and gas (O&G) sector depends on information analysis, making digital transformation vital. Industry-specific factors like environmental, regulatory, operational, and security challenges shape its tech adoption. This paper identifies and examines the barriers and drivers of digital transformation in O&G through a literature review and expert insights, leading to a questionnaire assessment. Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) was employed to create a structural model that illustrates the interactions between these barriers, helping experts understand how to achieve digitization within the industry. The questionnaire analysis identified the key barriers based on their RII values: “Experiments requiring significant time for validation of new technologies”, “Technical complexities of new technologies”, “Security concerns”, “Insufficient strategies”, and “Organizational culture and resistance to change”. The ISM indicated that the “Technical complexities of new technologies” and the “Lack of readily deployable technologies” are the most influential barriers. Addressing these is crucial for O&G companies to unlock digitalization potential.

1. Introduction

Digital transformation utilizes digital technologies to reshape business models, generating new value and opportunities [1]. It focuses on enhancing performance, safety, cost reduction, and efficiency through digitization [2,3]. Digitalization has significantly surpassed the conventional annual productivity improvement range of 3–5%, demonstrating a clear potential to reduce costs by over 25% [4]. The United Nations’ 7th Sustainable Development Goal calls for “affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all”, requiring rapid energy transitions and digital innovation to enable flexible power systems [5].

Prestidge [6] highlights the critical role of digital adoption to enhance competition and performance. This adoption varies due to the O&G sector’s unique nature. Digital solutions are crucial for improving efficiency, saving time, and accelerating decision-making. The O&G industry is projected to remain dominant up to 2060, accounting for about 55% of global energy consumption despite the rise of renewables [7,8]. Consequently, the sector is rapidly digitizing, with real-time analytics enhancing equipment availability and reducing delays [2]. To maintain competitiveness, businesses are adopting advanced technologies such as big data, IoT, cloud storage, digital twins, and AI to improve operations and add value [7,9,10]. The O&G industry is still in the early stages of adopting digital applications, behind other industries such as banking, tourism, media, and telecommunications [11]. Digital transformation encounters various barriers. Identifying these barriers can be challenging, particularly due to difficulties in accessing information and reports in the highly confidential O&G sector [12]. However, several previous studies have addressed this challenge by identifying alternative methods to obtain reliable data while ensuring its security and confidentiality [13,14,15]. Additionally, there is a notable lack of conducting investigation on digitization within the O&G sector when compared to other industries. Moreover, the number of digitization experts in O&G organizations is limited, as digital transformation in this industry remains in its early stages.

Given the O&G industry’s unique operational complexity, market instability, legacy systems, and workforce limitations, this paper focuses on exploring the primary barriers and their interdependencies in the digitalization efforts of the O&G sector. This study explores the barriers to digital transformation in the O&G sector. It aims to aid organizations in overcoming these challenges, optimizing resource allocation, and achieving a competitive advantage. It offers insights for policy formulation and supports decision-making processes to facilitate successful digital transformation within the industry.

2. Literature Survey

2.1. The Role of Digital Technologies in Improving the O&G Industry

Digitized technologies provide significant advantages to the O&G industry, including environmental protection, improved operational efficiency, and enhanced system reliability. As natural extraction declines, embracing technological advancements in exploration and production is vital for sustaining growth in petroleum fuels. Digitalization aims to improve processes, cut costs, and optimize operations [6,16]. Many organizations are adopting digital transformation tools like AI, robotics, and carbon capture and storage. Shukla and Karki [17] found that robotics in the O&G sector primarily focuses on inspecting pipes and tanks, with reliable autonomous models emerging as viable options despite the need for skilled operators.

Digitalization seeks operational excellence by creating a more efficient and responsive IT service environment. It involves implementing emerging technologies like data science, data center automation, and cloud computing, which integrate separate organizational sectors to enhance agility and drive innovation. This transformation boosts productivity and supports data-driven decision-making. Organizations can combine data from economics, commerce, and geophysical sciences with digital technology to enable advanced analytics and unlock previously untapped value through tools ranging from basic visualization to automated machine learning [6]. The O&G industry has faced many challenges, prompting technical, organizational, and administrative changes. Currently, the sector is under pressure from rising energy demand and environmental concerns, necessitating enhanced production efficiency and sustainability. Embracing digital transformation in O&G operations is now viewed as a strategic imperative. Developing an effective digitization strategy in the O&G industry is challenging due to extensive legacy systems and overlapping operational processes. Samoun [18] notes that structural complexities and reliance on partnerships for procurement, services, and engineering prevent smooth digital adoption. Additionally, the costs of implementing complex operational and management systems to meet standards pose a significant challenge. Peskova et al. [19] emphasize the necessity for each O&G company to create a strategic transformation plan aligned with both short-term and long-term objectives.

2.2. Previous Studies

Throughout this century, the O&G industry has progressed significantly [20]. Research has explored various aspects of this history, including investigations into digital transformation and barriers to digitization within the O&G sector.

Tung et al. [7] stressed that O&G firms must align their business models with technological advancements, necessitating the restructuring of organizational frameworks to meet digitalization demands. While most O&G workers recognize the importance of adopting digital technology, leaders encounter significant organizational challenges when implementing these initiatives. The study highlights three key pillars for successful digital transformation: human, process, and technological applications, with the human factor being the most significant barrier. Leaders should enhance training and knowledge sharing, especially when organizational experience is limited. They also identify major challenges in the O&G sector, including adherence to digitization strategies, traditional processes, resistance to change, budget constraints, and technical obstacles, all of which can impact safety. The limitation of this study lies in its focus on a single company, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other organizations. Further, limitations related to technological maturity and cybersecurity risks are discussed, suggesting the findings might not fully capture long-term impacts or variations in global practices.

Prestidge [6] examined challenges and solutions related to digitization in the O&G sector, identifying internal barriers like organizational structure, cultural dynamics, strategic gaps, and economic feasibility, alongside external barriers such as limited funding, workforce skills, and inadequate infrastructure.

Moşteanu [21] added that challenges include data isolation, workforce development, solution compatibility, resistance to digital transition, ineffective measurement of new technology efficiency, and incompatibility among digitized technologies. Nevertheless, the study’s limitations include a lack of detailed data on organizations that have restructured to integrate new technologies, insufficient correlation of required skills and activities for digital implementation, and limited focus on employee reallocation and requalification processes. These gaps suggest the need for further research to better understand the practical and workforce implications of digital transformation.

Kohli and Johnson [22] analyzed a case study to identify challenges that emerging industries face when digitalizing core processes and services. They noted the need for technical expertise, increased costs, conflicts in management, clashes between technology-oriented and business-focused cultures, budget constraints, and skill gaps between business experts and technology engineers. The study’s limitations include its reliance on a single case study, limiting generalizability and applicability to other firms. The solutions presented are context-specific and may not address broader workforce challenges or the integration of emerging technologies. It focuses on leadership roles without exploring operational-level impacts and is influenced by specific market conditions during a period of turbulence. Additionally, it lacks comprehensive industry comparisons and an analysis of barriers to digitization across latecomer industries.

Additionally, Bailie and Chinn [23] highlighted further barriers to digital adoption, including human resource limitations, the financial burden of new technologies, data management challenges, implications for existing processes, required cultural shifts, change management, leadership dynamics, strategic planning, effective communication, technology complexity, and cybersecurity concerns. The study’s limitations include a lack of comprehensive analysis of barriers, reliance on general trends and speculative future applications, and insufficient focus on segment-specific challenges within the O&G industry. It provides limited depth on cultural adaptation strategies, talent management for digital transformation, and actionable insights into cybersecurity risks and mitigation.

Kane et al. [24] identified key barriers to digitalization, such as conflicting priorities, lack of a comprehensive strategy, misunderstandings about digitalization, security concerns, limited collaboration, reluctance to take risks, and inadequate skills.

Parsoya [25] added that many technologies in the O&G industry remain underutilized due to insufficient knowledge and awareness. Nevertheless, the study does not include empirical evidence or detailed exploration of practical challenges, such as resource constraints and workforce adaptation.

Ismail et al. [26] emphasized that these challenges are common obstacles for businesses in the sector. Digital transformation disrupts companies’ value chains, organizational hierarchies, and operational protocols, but adaptation remains crucial. Historically, O&G companies have undergone major structural changes in response to challenges. For instance, Mitchell and Mitchell [27] noted that the sector’s structural stability was significantly affected in 2008 when demand exceeded supply, resulting in the elimination of structural surpluses.

Sarabdeen et al. [28] emphasized the important role of digital technology in addressing climate change by improving environmental quality. However, they identified differing impacts within the digital realm: internet access has a negligible effect on environmental quality, whereas mobile access shows a slightly negative influence. These observations indicate that although digital innovations offer notable environmental advantages, some aspects of their implementation could hinder sustainability objectives.

Since the 1980s, O&G firms have used sensors to collect vast amounts of data across industries, as noted by Snook [29]. However, while they excel in data collection, many struggle to effectively analyze and utilize it due to limited expertise in data analytics. Although 66% of respondents in an upstream O&G digitalization survey view analytics as crucial, only 13% are confident in their firm’s analytics capabilities.

Baaziz and Quoniam [30] identified key areas where the O&G industry could benefit from big data analytics, including process improvement, optimization, safety, and real-time decision-making. Although the industry acknowledges its potential, most firms are still in the early stages of adoption, with efforts remaining largely experimental.

Suppliers of technological assets and service providers offer valuable data to O&G firms [31], with their equipment, such as sensors, generating initial data. However, suppliers often hesitate to provide open, standardized, and accessible data, fearing product commoditization. Prestidge [6] recommended that O&G firms collaborate with their partners to implement these requirements and establish an open data platform.

Digital transformation in the energy sector, including O&G, is often slow due to delayed adoption of new technologies [32]. Tung et al. [7] noted that introducing new technology requires careful evaluation and adjustments to current processes. This delay is largely due to the industry’s culture and reluctance to abandon long-standing practices [8,24], with many organizations hesitant to take risks associated with sudden changes [33,34]. However, to stay competitive, the industry must embrace innovation and experiment with new approaches, gaining valuable insights even from failed attempts. Carvajal et al. [35] highlighted that downstream sector organizations have successfully reorganized their digitization efforts by adopting sensors to improve drilling operations and integrating them with supply chain information systems to optimize and accelerate processes.

The IT infrastructure of the O&G industry is lagging due to outdated data processing technology that fails to meet increasing demands. Legacy systems, such as the “Highway Addressable Remote Transducer (HART) protocol”, “SCADA”, and “Fieldbus”, are still used in modern centralized distributed control systems [18].

The use of such old protocols can be due to the existing infrastructure, in which a big investment was already made. The replacement of such a system can be costly. In addition, the existing system is inexpensive compared with modern systems and has proven to be reliable, so there is no good reason to replace it. Consequently, the upstream O&G sector remains in the early stages of digitization. Singh [34] identified budgeting limitations as a significant challenge to digital transformation, emphasizing the need for alignment between strategy and the business model. These challenges are primarily due to two factors: (i) market price instability and (ii) high operating costs.

Current global market conditions are marked by uncertainty, with factors like economic slowdowns and political conflicts making oil prices unpredictable. These prices directly impact O&G firms’ profitability and investment decisions [36]. Thus, organizations are more likely to invest in new fields if they expect prices to rise, while expected price drops may delay exploration and development projects. Bailie and Chinn [23] stated that operations in the O&G industry are expensive, with high capital costs and numerous variables affecting operating expenses. Increasing project complexity, regulatory requirements, and labor costs further drive-up expenses. Combined with fluctuating global prices, these factors make digitalization more costly and less economically feasible compared to other sectors.

3. Research Methodology

This study employed a research methodology consisting of several key steps. An extensive literature review identified barriers to digitization in the O&G industry, complemented by insights from field experts. An online survey was distributed to O&G professionals to assess the perceived importance of these barriers, with data undergoing statistical analysis for significance. Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) was then utilized to explore relationships among the barriers and create a structural model of their interactions. Finally, the findings were discussed, and conclusions and recommendations were made based on the survey analysis and ISM results.

3.1. Identifying Barriers to Digital Transformation

A comprehensive review of the literature addressing the obstacles to digital transformation within the O&G sector revealed a wide range of challenges across operations and regions. Despite this diversity, several barriers consistently surfaced. To explore the barriers to digital transformation in the O&G sector, semi-structured interviews were conducted with seven experts with 15 to 33 years of industry experience in roles such as senior data analysts and project engineers. These experts were specifically chosen for their direct involvement in digital transformation initiatives and leadership roles in system transformation projects. The interviews used a semi-structured format to balance consistency in core questions with the ability to gain insight into emerging themes. The interview questions were carefully developed based on a thorough review of the literature. The interviews, each lasting approximately one hour, were conducted in person. All participants were briefed on the study’s objectives, with informed consent obtained before the interviews commenced. Experts highlighted the need to address safety concerns, challenges at brownfield sites, investment in new systems with adequate data transfer infrastructure, and competition for funding between digitalization and expansion projects.

Thematic analysis was used to identify and interpret patterns related to digital transformation barriers in the interview data. To ensure a detailed and accurate representation of the expert discussions, the interviews were first conducted. The research team became familiar with the responses through repeated readings, allowing them to fully engage themselves in the information. Next, an initial coding process was carried out, which involved systematically identifying and labeling meaningful data segments. These codes were then classified into larger categories to capture common themes and insights. The themes were iteratively refined through discussions and cross-referenced with findings from the literature to ensure validity and coherence. To enhance the reliability of the findings, the participants reviewed the identified themes to confirm the accuracy and relevance. The final analysis identified 20 key barriers to digital transformation in the O&G sector, which formed the basis of the study’s findings and discussions. These barriers, summarized in Table 1, are classified by their causes and organizational implications, including administrative, cultural, technical, financial, security, human resources, existing infrastructure, and other factors.

Table 1.

Description of the identified barriers to digitalization in O&G industry.

3.2. Questionnaire Survey Design

The survey was developed using Google Forms and distributed online to O&G professionals for efficient data collection. This approach enabled respondents to fill out the questionnaire survey at their convenience and facilitated the subsequent data analysis process. The survey had three sections: the first explained its purpose and objectives, the second asked four general questions about participants’ education, experience, and job roles, and the third asked participants to rate the frequency of 20 identified barriers on a weighted scale. Respondents rated each barrier on a scale of 5 to 1 to determine its importance regarding its occurrence or impact on digital transformation in the O&G sector. The scale was defined as follows: Extremely Important (5; 100%), Very Important (4; 80%), Important (3; 50%), Somewhat Important (2; 20%), and Not Important (1; 0%), reflecting each barrier’s influence on digitalization efforts.

Statistical analysis of the feedback used the Relative Importance Index (RII), a simple and effective tool for ranking the barriers discussed in this paper. The RII ranges from zero (minimal importance) to one (maximal importance). The RII is calculated using Equation (1) [40].

where

- i is the response category index;

- ai is the weight given to i response; and

- xi is the variable expressing the frequency of i.

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Profile of Respondents

A total of 112 participants from Saudi Arabia completed the survey. As the second-largest holder of oil reserves, Saudi Arabia accommodates 17% of the world’s proven petroleum reserves [41]. Analysis of the second section showed a diverse range of educational backgrounds and work experience. Over 76% of participants held engineering degrees, reflecting the industry’s technical focus. Most had a bachelor’s degree (54%), followed by master’s degrees (31%), with only 3% holding a PhD. More than 75% had 5 to 15 years of experience, 15% had 15 to 20 years, 7% had over 25 years, and only 2% had 20 to 25 years. This indicates a younger workforce, driven by initiatives promoting learning and competition and supporting digital adoption and leadership development [7]. Most respondents were engineers, with 58% in technical or project roles and 17% in management, highlighting their scientific backgrounds and relatively limited practical experience.

4.2. RII Calculations

The Relative Importance Index (RII) for each barrier was determined using Equation (1), as illustrated in Table 2. RII values ranged from 0.618 to 0.725, indicating that all barriers could significantly impede digital transformation in the O&G sector. The top four barriers identified were security concerns, the time required to validate new technologies, organizational culture and resistance to change, and the technical complexities of new technologies. The fifth barrier, “aging facilities and legacy systems”, also had a notable RII value close to the top four. In contrast, barriers related to safety requirements, data management, and team communication were ranked as less impactful.

Table 2.

Rank of identified barriers.

The survey analysis showed that nearly half of the participants had fewer than five years of experience in the O&G sector. Typically, more experience improves the ability to identify and assess workplace challenges, which is crucial for evaluating barriers to digital transformation. In a complex sector like O&G, fewer than 10 years of experience may limit understanding of these challenges, potentially impacting assessment accuracy. To improve reliability, the study re-evaluated the data, focusing on the 50 professionals with 10 or more years of experience.

This led to a recalculation of the RII and a revision of the barrier rankings, as depicted in Table 2. The new RII values ranged from 0.58 to 0.74, indicating that all identified barriers could significantly impede digital transformation in the O&G sector. The ranking shifted, with the two most significant barriers now being the time required to validate new technologies and the technical complexities of those technologies. Security concerns ranked third, followed by insufficient strategies in fourth place. The calculated Spearman coefficient of rank correlation was 0.881, indicating a very high level of agreement on the barrier rankings between all respondents and those with 10 or more years of experience.

4.3. The Interpretive Structural Modeling Approach (ISM)

The RII technique primarily ranks the identified barriers under the assumption of their independence [42], which may not be accurate. To address this issue, the Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) approach is utilized to examine the complex interrelationships among these identified barriers and develop a structural model that reflects their interactions [43,44]. The ISM approach has been applied in various contexts, including identifying factors that facilitate off-site construction adoption [42] and exploring barriers to sustainable tourism development [45,46].

In addition to the RII calculations, the ISM model has been utilized to assist experts in understanding how to achieve digitization in the O&G industry. The ISM methodology works as follows:

- Step One: Gather, summarize, and prioritize the barriers impacting digitization in the O&G sector. This step is completed, with results shown in Table 2.

- Step Two: Experts examine the relationships among these barriers to create a Structural Self-Interaction Matrix (SSIM) that illustrates their interactions.

- Step Three: Convert the upper triangular SSIM into a binary format to form the Initial Reachability Matrix (IRM).

- Step Four: Assess the IRM for transitivity, ensuring that if Barrier A influences Barrier B, and Barrier B influences Barrier C, then Barrier A should also influence Barrier C. This results in the Final Reachability Matrix (FRM).

- Step Five: Use the FRM to create a partitioning table, isolating barriers and assigning levels, which is crucial for the ISM model.

- Step Six: Develop an initial ISM model based on the partitioning table. Check for inconsistencies or logical errors, repeating the process as needed until a satisfactory model is achieved.

4.3.1. Developing the SSIM Matrix

The SSIM matrix is constructed by analyzing the relationships among barriers through the use of symbolic indicators: V indicates barrier i influences barrier j; A indicates barrier j influences barrier i; X indicates mutual influence; and O indicates no influence. Experts assessed these relationships, with only three available during the survey preparation. The experts facilitated the initial SSIM matrix development. The ISM methodology is iterative; each matrix is checked for errors, and the process is repeated if discrepancies are found. Only the final results are reported, and the developed SSIM matrix is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

SSIM Matrix.

4.3.2. The IRM Matrix

Developing the IRM matrix requires factoring the contextual relationships in the SSIM matrix using the following transformation rules:

- If cell (i, j) has the symbolic code V, then cell (i, j) will be assigned 1, and cell (j, i) will be assigned 0.

- If cell (i, j) has the symbolic code A, then cell (i, j) will be assigned 0, and cell (j, i) will be assigned 1.

- If the cell (i, j) has the symbolic code X, then both cells are assigned 1.

- If the cell (i, j) has the symbolic code O, then both cells are assigned 0.

These rules were followed to fill all cells. Table 4 presents the IRM matrix.

Table 4.

The IRM Matrix.

4.3.3. The FRM Matrix

The transitivity relations between barriers were further examined. A transitivity relationship implies that if barrier A results in barrier B, and barrier B results in barrier C, then barrier A results in barrier C, too. The transitivity relationships were examined, and the IRM was transferred into the FRM matrix, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

FRM matrix.

4.3.4. Levels Portioning

The portioning table includes the reachability set (all barriers influenced by a given barrier, including itself), the antecedent set (all barriers influencing that barrier, including itself), and the intersection set (barriers common to both sets). Barriers are assigned levels through an iterative process that examines both sets in each iteration. Barriers with identical reachability and antecedent sets are extracted and assigned levels based on the iteration number. The FRM is then reduced, and this process continues until all barriers are levelled. Due to the lengthy nature of this iterative procedure, all iterations are condensed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Partitioning table.

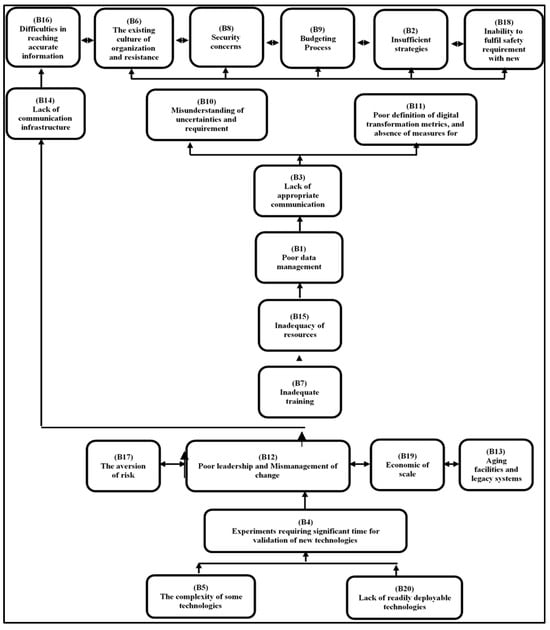

The portioning table displays the barriers assigned to levels, with Level 1 barriers at the top of the ISM model and the highest-ranked barriers at the bottom. The ISM model, derived from the portioning table, is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The ISM model.

5. Discussion

As shown in Figure 1, the ISM identifies two main influential barriers driving the current state of digitization in the O&G sector: “Lack of readily deployable technologies” (B20) and “The complexity of some technologies” (B5), both hindering adoption. These barriers directly impact “Experiments requiring significant time for validation” (B4). Addressing these challenges helps management tackle “Poor leadership and mismanagement of change” (B12), as well as factors like “Aversion to risk” (B17), “Economies of scale” (B19), and “Aging facilities and legacy systems” (B13). Based on these findings, decision-makers can develop plans to enhance digitization adoption. Workforce training will address (B7) “Inadequate training”, while establishing a robust communication infrastructure will resolve (B14) “Lack of communication infrastructure”.

Moreover, improving (B3) “Lack of appropriate communication and teamwork” will lead to a better understanding of the uncertainties and risks referenced in (B10) “Misunderstanding of uncertainties and requirements”. This will contribute to a well-defined digital transformation strategy, including clear standards, key performance indicators, and measures of success or failure, addressing (B11) “Poor definition of digital transformation standards and absence of performance measures for digitalization”.

Agreeing on digitization enables effective strategies to address (B2) “Insufficient strategies” for transformation. It includes developing cybersecurity measures for (B8) “Security concerns” and ensuring individual safety (B18), especially with wireless networks. This agreement also helps secure funding to overcome (B9) “Budget limitations” and promotes a positive culture to combat (B6) “Organizational resistance to change”.

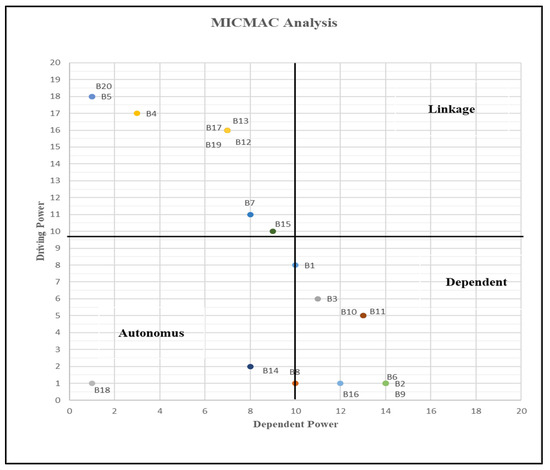

5.1. MICMAC Analysis

Figure 2 illustrates the categorization of barriers through MICMAC analysis, highlighting their driving and dependent powers. The barrier driving power is calculated as the sum of its own row and the rows it influences in the FRM matrix, while the dependent power is the sum of its column and the columns that influence it. Both powers are displayed alongside the FRM matrix in Table 5.

Figure 2.

The MICMAC analysis.

The barriers are categorized into the following groups based on their driving and dependent powers:

- Autonomous barriers: Low driving and dependent power (B14, B18).

- Driving barriers: High driving power and low dependent power (B4, B5, B7, B12, B13, B15, B17, B19, B20).

- Linkage barriers: High driving and dependent power (none identified).

- Dependent barriers: Low driving power and high dependent power (B1, B2, B3, B6, B8, B9, B10, B11, B16).

Barriers in the driving quadrant are highly influential and should be prioritized, as they are key for advancing digitization in the O&G sector. Conversely, barriers in the dependent quadrant generally indicate the system’s efficiency once established.

5.2. Proposed Strategies

Based on the RII results, ISM analysis, and study insights, the following recommendations are proposed to accelerate digitalization in the O&G sector. The recommendations are tailored to address the barriers in the ISM model:

- The barriers at levels 8 and 9: The top barrier identified by professionals with over 10 years of experience and presented by the ISM model is the “Time-consuming validation of new technologies” (B4). To address this, it is essential to manage the “Technical complexities of new technologies” (B5) and overcome the “Lack of readily deployable technologies” (B20).

- Level 7 barriers: Many digital projects struggle to demonstrate economic viability (B19) during assessment, which is crucial for securing funding. Analysts should refine models to capture all positive impacts, including value creation and cost reduction, requiring a deep understanding of digitalization’s benefits. While valid concerns like the fear of the unknown (B17) must be addressed, management should recognize that inaction poses a greater threat to survival (B12). Achieving zero risk is unrealistic; the focus should be on assessing and mitigating risks (B17).

- The barriers at Levels 3, 4, 5, and 6: Transitioning to new technologies can be challenging due to digitization complexities. Establishing training programs (B7) aligned with digital transformation is essential to ensure the workforce can effectively use new technologies and minimize disruptions. O&G companies should recruit specialized experts (B15) to lead implementation and facilitate knowledge sharing. Adopting effective knowledge transfer (B1 and B3) mechanisms, such as web-based systems, will support new practices and ongoing training efforts.

- The barriers at Levels 1 and 2: Installing untested technologies is not advisable. To expedite experimentation, employees need support and flexibility in decision-making (B14). Establishing benchmarks and partnerships can foster innovation (B10 and B11). Collaborating with technology leaders and involving them in R&D helps design solutions tailored to O&G needs. Agreements with suppliers or manufacturers can facilitate faster information exchange, enabling more experimentation and quicker implementation to realize the benefits of new technologies (B16).

- The barriers at Levels 1 and 2: O&G companies should invest in security frameworks (B8), focusing on training and awareness to promote collective responsibility for information security. This may involve reassessing regulations to strengthen authority and impose precise penalties for violations. Enhancing security during technology deployment will support digitalization while ensuring safer data transfer. Cybersecurity is critical for maintaining operational safety (B18) and protecting data confidentiality. Additionally, the sector should seek proven technologies that meet operational needs and enable developing sufficient strategies (B2) without extensive experimentation

- Economics of scale (B19): Moving into fully digitized system entails a high amount of investment. With the cybersecurity concerns are relieved (B8), and the presence of enough strategies for transformation (B2), adequacy of resources (B15), proper training (B7), and all other barriers resolved, the determining factor for transformation is based on the proper balance between benefits incurred relative to the high expected expenditure. O&G companies should be aware that over the short term, benefits from transformation cannot be realized. Nevertheless, digital transformation is a strategic decision, and the incurred benefits should be expected to be realized in the long run.

6. Conclusions

The O&G sector must adopt digital technologies to remain competitive and meet rising demand. Digitalization is essential for flexibility in market challenges and field management. Existing barriers should not hinder digital transformation goals. This study identified and prioritized 20 barriers to digital transformation in Saudi Arabia’s O&G sector, based on expert consultation and research. The barriers span administration, culture, economics, technical issues, structure, procedures, and human factors. All had high RII values, with the most significant being lengthy technology validation, complexity, security concerns, resistance to change, aging facilities, and lack of deployable technologies.

The ISM approach is utilized to analyze the relationships between barriers and develop a structural model of their interactions. It reveals that “Lack of readily deployable technologies” (B20) and “Technical complexities of new technologies” (B5) are the main obstacles to digitalization. Consequently, any new technology requires extensive testing, with “Experiments requiring significant time for validation” (B4) before adoption.

This paper provides recommendations to speed up digitalization in the O&G sector, derived from RII results and ISM analysis. A key barrier is the “Time-consuming validation of new technologies”, which can be addressed by managing “Technical complexities” and overcoming the “Lack of readily deployable technologies”. Enhancing security during technology deployment will also aid digitalization and ensure safer data transfer. However, overcoming these barriers requires significant changes to established policies and standards. The transformation will be costly, demanding employee training, cultural acceptance, procedural adjustments, facility upgrades, and coordination across organizations, all requiring high-level approvals. Integrating digital transformation into corporate strategies is essential for aligning with investment plans.

Despite the useful insights provided by this study, several limitations need to be indicated. First, the sample size of participants may be increased. The study’s focus on the Saudi O&G sector may limit the findings’ applicability to other countries or regions with different regulatory, operational, and cultural contexts. Furthermore, the study identifies several challenges but does not evaluate the practical feasibility or cost-effectiveness of the proposed recommendations, such as the implementation of new technologies or employee training programs. The dynamic and rapidly evolving nature of digital technologies in the O&G sector also presents a challenge, as the identified barriers may change over time as technology advances. To overcome these limitations, future research can be carried out to

- Develop strategies and frameworks to address the cultural resistance and promote digital transformation in O&G.

- Examine the impacts of different digital technologies (such as IoT and AI) on safety protocols and security frameworks in the O&G sector.

- Investigate how technology validation processes can be streamlined without compromising safety or functionality, possibly by using simulations or digital twins.

- Explore how training programs can be optimized to equip the workforce with the necessary skills for digital transformation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.; Methodology, A.A.; Validation, A.A.; Formal analysis, A.A., S.M.A., M.A.H. and F.T.; Investigation, D.O. and A.M.; Data curation, S.M.A.; Writing—original draft, S.M.A.; Writing—review & editing, M.A.H., F.T., D.O. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Article Processing Charges (APCs) were funded by King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals (KFUPM), Saudi Arabia.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals (KFUPM) for the support and facilities that made this research possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Frenzel, A.; Muench, J.C.; Bruckner, M.T.; Veit, D. Digitization or digitalization? Toward an understanding of definitions, use and application in IS research. In Proceedings of the 27th American Conference on Information Systems, Virtual, 9–13 August 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Abdellah, W.R.; Kim, J.G.; Hassan, M.M.A.; Ali, M.A.M. The key challenges towards the effective implementation of digital transformation in the mining industry. Geosyst. Eng. 2022, 25, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, Z.; Musilek, P. Impact of digital transformation on the energy sector: A review. Algorithms 2023, 16, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowski, P.F. Digitization, digital twins, blockchain, and industry 4.0 as elements of management process in enterprises in the energy sector. Energies 2021, 14, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, S.; Rotta, D.L.; Nieto-Londoño, C.; Vásquez, R.E.; Escudero-Atehortúa, A. Digital transformation of energy companies: A Colombian case study. Energies 2021, 14, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestidge, K.L. Digital transformation in the oil and gas industry: Challenges and potential solutions. Master’s Thesis, System Design and Management Program, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 23 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tung, T.V.; Trung, T.N.; Hai, N.H.; Tinh, N.T. Digital transformation in oil and gas companies—A case study of Bien Dong POC. Petrovietnam J. 2020, 10, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kober, T.; Schiffer, H.W.; Densing, M.; Panos, E. Global energy perspectives to 2060—WEC’s World Energy Scenarios 2019. Energy Strategy Rev. 2020, 31, 100523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Guo, L.; Azimi, M.; Huang, K. Oil and gas 4.0 era: A systematic review and outlook. Comput. Ind. 2019, 111, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knebel, F.P.; Trevisan, R.; Nascimento, G.S.D.; Abel, M.; Wickboldt, J.A. A study on cloud and edge computing for the implementation of digital twins in the Oil & Gas industries. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 182, 109363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rbeawi, S. A review of modern approaches of digitalization in oil and gas industry. Upstream Oil Gas Technol. 2023, 11, 100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeme, C.; Liyanage, K. Integration of Industry 4.0 to the CBM practices of the O&G upstream sector in Nigeria. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2024, 41, 1657–1692. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, R.W.; Salah, K.; Jayaraman, R.; Yaqoob, I.; Omar, M. Blockchain in oil and gas industry: Applications, challenges, and future trends. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umran, S.M.; Lu, S.; Abduljabbar, Z.A.; Lu, Z.; Feng, B.; Zheng, L. Secure and privacy-preserving data-sharing framework based on blockchain technology for al-najaf/iraq oil refinery. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Smartworld, Ubiquitous Intelligence & Computing, Scalable Computing & Communications, Digital Twin, Privacy Computing, Metaverse, Autonomous & Trusted Vehicles (SmartWorld/UIC/ScalCom/DigitalTwin/PriComp/Meta), Haikou, China, 15–18 December 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 2284–2292. [Google Scholar]

- Kishnani, U.; Madabhushi, S.; Das, S. Blockchain in oil and gas supply chain: A literature review from user security and privacy perspective. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Human Aspects of Information Security and Assurance, Kent, UK, 4–6 July 2023; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 296–309. [Google Scholar]

- Mugge, P.; Abbu, H.; Michaelis, T.L.; Kwiatkowski, A.; Gudergan, G. Patterns of digitization: A practical guide to digital transformation. Res. Technol. Manag. 2020, 63, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Karki, H. Application of robotics in onshore oil and gas industry—A review Part I. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2016, 75, 490–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoun, M.B.; Holmås, H.; Santamarta, S.; Forbes, P.; Clark, J.T.; Hughes, W. Going Digital is Hard for Oil and Gas Companies—But the Payoff Is Worth It; Boston Consulting Group: Boston, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Peskova, D.R.; Khodkovskaya, Y.V.; Nazarov, M.A. The driver of development and transformation of global oil and gas business in digital economy’s conditions. In Proceedings of the 17th International Scientific Conference: Problems of Enterprise Development, Theory and Practice, Samara, Russia, 26–27 November 2018; SHS Web of Conferences: Paris, France, 2019; Volume 62, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yergin, D. The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Moşteanu, N.R. Challenges for organizational structure and design as a result of digitalization and cybersecurity. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2020, 11, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, R.; Johnson, S. Digital transformation in latecomer industries: CIO and CEO leadership lessons from Encana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc. MIS Q. Exec. 2011, 10, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Bailie, B.; Chinn, M. Effectively harnessing data to navigate the new normal: Overcoming the barriers of digital adoption. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 30 April 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, G.C.; Palmer, D.; Phillips, A.N.; Kiron, D.; Buckley, N. Strategy, Not Technology, Drives Digital Transformation; MIT Sloan Management Review: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Parsoya, S.; Perwej, A. Significance of technology and digital transformation in shaping the future of oil and gas industry. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. 2021, 12, 3345–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.H.; Khater, M.; Zaki, M. Digital business transformation and strategy: What do we know so far? Camb. Serv. Alliance 2017, 10, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J.V.; Mitchell, B. Structural crisis in the oil and gas industry. Energy Policy 2014, 64, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarabdeen, M.; Elhaj, M.; Alofaysan, H. Exploring the influence of digital transformation on clean energy transition, climate change, and economic growth among selected oil-export countries through the panel ARDL approach. Energies 2024, 17, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snook, J. Digitization of the Oil and Gas Industry: Challenges and Reward; GoContractor: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://gocontractor.com/blog/digitization-oil-gas-industry/ (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Baaziz, A.; Quoniam, L. How to use Big Data technologies to optimize operations in Upstream Petroleum Industry. Int. J. Innov. 2013, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. The development of knowledge management in the oil and gas industry. Universia Bus. Rev. 2013, 9, 92–125. [Google Scholar]

- Maroufkhani, P.; Desouza, K.C.; Perrons, R.K.; Iranmanesh, M. Digital transformation in the resource and energy sectors: A systematic review. Resour. Policy 2022, 76, 102622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmanova, S.V.; Andrukhova, O.V. Oilfield service companies as part of economy digitalization: Assessment of the prospects for innovative development. J. Min. Inst. 2020, 244, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. Digital Transformation in Oil and Gas Industry; Technical Report; School of Petroleum Management: Raysan, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Munim, Z.H.; Balasubramaniyan, S.; Kouhizadeh, M.; Hossain, N.U.I. Assessing blockchain technology adoption in the Norwegian oil and gas industry using Bayesian Best Worst Method. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2022, 28, 100346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roisse, R.F. Decision-making under risk: Conditions affecting the risk preferences of politicians in digitalization. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezafar, E. The Implementation of Advanced Digitalization in the Oil and Gas Industry. Ph.D. Dissertation, College of Management and Human Potential, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert, C.; Duarte, C.H.C. Digital transformation. IEEE Softw. 2018, 35, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pau, M.; Mirz, M.; Dinkelbach, J.; Mckeever, P.; Ponci, F.; Monti, A. A service oriented architecture for the digitalization and automation of distribution grids. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 37050–37063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanain, M.A.; Fatayer, F.; Al-Hammad, A.M. Design-phase maintenance checklist for electrical systems. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 2016, 30, 06015003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), Vienna, Austria, 2024. Available online: https://www.pmfias.com/organisation-of-the-petroleum-exporting-countries-opec/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Trigunarsyah, B.; Santoso, T.P.; Hassanain, M.A.; Tuffaha, F. Adopting off-site construction into the Saudi Arabian construction industry. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Smart Infrastruct. Constr. 2020, 173, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Qahmash, A. SmartISM: Implementation and assessment of Interpretive Structural Modeling. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, A.; Ma, S.; Nedungadi, P.; Sreedharan, V.R.; Raman, R.R. Interpretive Structural Modeling: Research trends, linkages to sustainable development goals, and impact of COVID-19. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K.; Sun, H.; Ramzan, M.; Mahmood, S.; Saeed, M.Z. Interpretive Structural Modeling of barriers to sustainable tourism development: A developing economy perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshibani, A.; Aldossary, M.S.; Hassanain, M.A.; Hamida, H.; Aldabbagh, H.; Ouis, D. Investigation of the driving power of the barriers affecting BIM adoption in construction management through ISM. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 102987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).