Abstract

This article aims to determine the specificity of spatial conflicts related to spatial plans concerning wind power plants. To achieve the aim of the article, all spatial plans in force in Poland were analysed, distinguishing those which determine the possibility of realisation of wind power plants. The research concerns the whole country. The literature review carried out for this article verifies approaches to spatial conflicts and identifies how planning barriers to the implementation of wind power investments are defined. The results identified Polish municipalities where spatial plans containing provisions for implementing wind power plants have been enacted. Then, through survey research, an attempt was made to identify critical spatial conflicts occurring in these municipalities. The last part of the research involved identifying and analysing Polish court decisions concerning spatial plans permitting wind power plants. These were recognised as a particular stage of spatial conflicts. The article’s novelty is the attempt to isolate regional spatial conflicts concerning wind power plants comprehensively. This applies to a broader scientific discussion (also applicable to other countries). In addition, the treatment of court cases as the final stage of spatial conflicts related to the location of wind power plants should be considered innovative. An important contribution to the international discussion is the proposal for broader (quantitative) research on the role of courts in spatial planning. Possible classifications in court settlements of parties to spatial conflicts, reasons for spatial conflicts, and ways of ending conflicts have been proposed.

1. Introduction

The location of renewable energy sources is associated with numerous transitional conflicts. These conflicts, depending on the specific solutions of the country and its planning culture, but also on the characteristics of the site, take different forms. Spatial conflicts cannot be eliminated from the spatial planning system [1]. However, they can be reduced by, among other things, introducing appropriate solutions and practices. From the sphere related to renewable energy sources, the issue of wind power plant location is very commonly singled out [2]. The issue of wind turbine locations is highly controversial in various countries.

This article aims to determine the specificity of spatial conflicts related to spatial plans determining the possibility of wind power plant investments. The following research questions were posed:

- To what extent do spatial plans determining the possibility of implementing wind power plants occur in the Polish planning system?

- What types of spatial conflicts are associated with the enactment of the indicated spatial plans? On what scale do such conflicts occur?

- How are the indicated spatial conflicts translated into court cases concerning spatial plans?

- How do we balance the competencies between central and local authorities when determining the location of wind power plants? What key barriers can be defined in this respect?

To achieve the aim of this article, all spatial plans in force in Poland (as of the end of 2020) were analysed, distinguishing those that determined the feasibility of wind power plants. The research applies to the case of Poland (verified comprehensively, considering detailed data for the whole country). Nevertheless, the discussion of planning barriers related to renewable energy sources is universal [3]. It is a crucial research task to identify specific problems at the interface of the relationship between renewable energy sources and spatial planning [4]. This provides a significant basis for further scientific discussion. Therefore, the combination of issues concerning the location of wind power plants, on the one hand, and spatial conflicts, on the other, seems very necessary.

In the literature review carried out for this article, reference was made to the specifics of spatial conflicts. Then, it was determined how barriers related to the implementation of wind power investments are defined in spatial planning systems. The above referred to the Polish spatial planning system, in which the indicated issues may be subject to more extensive research. Next, the communes in which spatial plans enabling the realisation of wind power plants have been enacted were identified. Through questionnaire surveys, an attempt was made to identify critical spatial conflicts (concerning wind power plants) in these communes. The last part of the research involved extracting and analysing Polish court decisions concerning spatial plans permitting wind power plants. The court stage was considered a particular stage of spatial conflicts. The rationale for this is the specificity of Polish court proceedings concerning spatial plans. During these proceedings, not only procedural considerations are examined, but also substantive objections of the applicants (property owners) against the plans.

The article’s novelty is an attempt to identify regional spatial conflicts concerning wind power plants comprehensively. Moreover, the treatment and analysis of court cases as the final, final stage of spatial conflicts related to the location of wind power plants should be considered new (this is possible due to the framework of the Polish spatial planning system, but also due to the interdisciplinary approach of the authors). It should be emphasised that this article contains the first attempt at such a comprehensive, multifaceted, interdisciplinary analysis of how the issue of wind power plants is addressed in the national spatial planning system.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Spatial Conflicts Regarding the Location of Wind Power Plants

Spatial conflicts are analysed from different perspectives. They affect a wide range of urban and rural areas, both with their specificities [5,6,7]. Very often, the reason for spatial conflicts is the difficulty (and sometimes impossibility) of fully reconciling the objectives and challenges of spatial planning with the individual expectations of private property owners [8]. There is considerable variation in this regard across systems [9]. However, there are also many analogies. On the one hand, there is an attempt to realise spatial policy objectives. On the other hand, there is the private perspective [1,10]. From the private perspective, spatial development restrictions are typically not justified (they block the property owner’s intentions). Spatial conflicts can be classified from the subject’s and object’s perspectives. An example of the latter classification can be the conflict between economic development in a given area and environmental and landscape protection [11,12,13]. Diverse parties are involved in such conflicts. The indicated tendencies are also noticeable when examining the spatial aspect of the location of wind power plants. After a preliminary analysis, solid grounds for spatial conflicts can be identified here [14].

The development of wind power plants to guarantee energy efficiency is promoted in numerous countries [15,16]. One frequently discussed dimension is the development of wind power plants in offshore areas [17]. For many countries, however, it is equally vital to promote onshore wind power investments [18,19,20]. However, significant challenges arise regarding the adaptation of individual site functions and the optimal implementation of wind power plants in rural and urban areas [21,22,23]. Here, the role of spatial planning emerges as crucial. The spatial planning systems of the individual countries are mutually differentiated: both institutionally and in terms of the terminology used. For this article, however, it can be assumed that at least most spatial planning systems are concerned with the optimal use of space and the reduction of spatial conflicts [9,24,25,26,27]. It has long been clear that spatial planning has to adapt to emerging challenges, including the need to implement wind power plants [28]. Very often, the need to implement wind power plants is a significant challenge for spatial planning. It happens on many levels: adapting wind turbines to urban spaces [29,30] and the optimal spatial scale. There is an ongoing debate in the literature whether the optimal scale from the perspective of wind turbine siting is local, regional, or perhaps central. A reported argument favouring a broader role for central authority is the greater chance of preventing spatial conflicts from this scale. The more substantial strategic planning dimension at the central level contributes to this [31]. On the other hand, excessive centralisation poses severe risks and contradicts the basic assumptions of many spatial planning systems [32]. Felber and Stoeglehner [33] point out that the location of wind turbines can be determined locally. The stipulation is that this location should be determined for the entire municipality area (and not fragmentarily). In practice, some solutions should balance central and local action. This would boil down to finding a compromise between the planning autonomy of the municipality and specific guidelines formulated at the national level. The authors draw attention to the role of regulations specifying minimum distances between wind power plants and residential buildings in this context. They represent an attempt to interfere in local spatial planning. Such guidelines must, however, assume a certain flexibility. To this must be added another obligation: verification of the impact of wind energy on the environment and landscape. The result of such verification should also be reflected in planning regulations [34,35,36,37].

Loring [38] points out explicitly that spatial planning is a significant barrier to the development of onshore energy in many countries and that the reason for this is the lack of ability to resolve spatial conflicts arising in this context. According to the author, strengthening public participation is key to ensuring success. A similar position is suggested by other authors [39].

Possible conflicts concern threats to the environmental, natural, and landscape spheres and tourism, public health, or housing [14]. Bidwell [40] also sees another element: the often-occurring bottom-up, subjective (resulting from traditionalism) opposition to this type of investment. According to the author, the optimal response to this opposition should be to explain the economic benefits of investments to local communities. Kirchhoff et al. [41] recognise that the reasons for objections are complex. In particular, they mention issues related to the likely impacts of wind turbines on human health, wildlife, and landscape. Swofford and Slattery [42] point out that the extent of possible opposition to an investigation also depends on how close to a particular residence the development is to be built (the closer the residence, the greater the potential opposition of residents may be). Enserink, van Etteger, der Bink and Stremke [43] identified factors of acceptance for the location of wind power plants, also referring to acceptance from the community. In this case, they identified economic, environmental, project detail, time, social, construction, and process factors as critical factors.

The literature has therefore analysed in detail the issues related to potential community acceptance and contestation of wind power investments. Numerous publications also consider the optimal alignment of national planning levels with wind power investments. There is also no doubt about the particular conflicts associated with the location of wind power plants. However, some research gaps can be identified from the perspective of the spatial planning system. These relate to:

- An in-depth, at least on a national scale, consideration of the optimal relationship between central legislation and local spatial planning. Authors dealing with wind power plants most often refer to the analysis of national solutions and selected case studies. This is very valuable material. However, it should be complemented by broader, holistic approaches wherever possible;

- References of wind power-related spatial conflicts to court cases. It may only be the case for those regimes where the courts more broadly assess the content of spatial policy acts (primarily spatial plans). Nevertheless, this is an essential issue concerning the broader relationship between law and spatial planning.

2.2. Poland as an Essential Case Study for Spatial Conflict Research

The Polish spatial planning system can be considered particularly suitable for spatial conflict research. It applies particularly to the spatial dimension of the implementation of wind power plants [44]. This is related to the specificity of the Polish spatial system, which boils down to the following:

- Huge spatial chaos, above the standard concerning other countries, generating severe costs. This chaos is related to the uncontrolled development of buildings from a planning perspective and the inefficiency of public authorities [45,46];

- The optionality of spatial plans at the local level. There is no obligation to adopt spatial plans in Poland. Their adoption depends on the discretion of the municipal authorities. It also applies to spatial plans consenting to the location of wind power investments. From a legal perspective, municipalities cannot be required to adopt such plans. The enactment of plans can only result from the goodwill of the municipal authorities [9];

- A specific approach to renewable energy sources, particularly wind power plants. Concerns expressed in the public sphere about wind power plants resulted in above-standard planning restrictions introduced in 2016 [4]. In the current, oft-criticised legal state, the location of wind power plants is only possible based on (optionally adopted) local spatial plans and with the observance of developed distance criteria regarding residential buildings [47]. In 2016, a rule was set out that the minimum (captured in spatial plans) distance of a wind turbine from residential development must be at least ten times the height of the wind turbine. It was this change that was groundbreaking from the perspective of further planning opportunities for wind turbines. The introduction of such a large distance meant that establishing the location of wind turbines in plans was, as a rule, linked to the emergence of spatial conflicts. It must be clearly emphasised that within a radius of ten times the height of the wind turbine, a prohibition on development must be included in the plan. The owners of neighbouring properties (even those located at a distance but within the sphere of the building ban around the power plant) are not happy with the restrictions introduced. This deters a large proportion of municipal authorities from adopting these spatial plans. It has significantly impeded the development of this direction of renewable energy sources in Poland;

- Peculiarities of the Polish judiciary (Table 1). Any spatial plan may be challenged (by the owners of the properties covered by it) before an administrative court. The court may then assess not only procedural issues but also the content of the spatial plan itself. The assessment also concerns whether specific provisions of the spatial plan do not unduly interfere with the property right of the property owner [48,49]. The property right in the Polish spatial planning system is very precisely and very broadly understood [50];

Table 1. Characteristics of Polish courts in spatial planning system.

Table 1. Characteristics of Polish courts in spatial planning system.

- Poor level of public participation in spatial planning.

The above features of Poland’s spatial planning system should be negatively assessed. The literature review concludes that the local dimension is vital in spatial planning and that there must be some balance with the central level when implementing wind power investments. In Poland, the two spheres are not aligned, which blocks the implementation of the indicated investments. Nevertheless, as indicated above, these problematic features of the Polish system provide an opportunity for more extensive research. The results of these studies have a universal dimension that can be referred to in an international discussion. Śleszyński et al. [47] also drew attention to the dispersed settlement in Poland, which requires particular adaptation of the concept of renewable energy sources (on the one hand, it facilitates the location of micro-installations, but on the other hand, due to distance limitations, it significantly hinders the location of larger wind power plants). According to a study by Blaszke et al. [4], municipalities have little involvement in the issue of renewable energy sources. Their research indicates that in conceptual documents at the local level, i.e., studies of spatial development considerations and directions, only half of the municipalities include the issue of renewable energy sources in any way. Solarek and Kubasińska [51] point to the problematic scope of the Polish spatial plans and the barriers associated with including renewable energy sources in these acts. A study by Blaszke et al. [3] shows that it is possible to try to link the planning commitment of municipalities in the sphere of renewable energy sources with the specific characteristics of the municipalities. However, the authors point to the need for a broader differentiation of individual categories of renewable energy sources in spatial planning. It is clear from the above summary that the research so far lacks an in-depth analysis of the relationship between spatial planning and a specific type of renewable energy source, i.e., wind power plants (the analyses so far tend to cover renewable energy sources as a single group). Since the location of wind power plants is particularly prone to spatial conflicts, an analysis of possible spatial conflicts and the related legal mechanisms, including judicial ones, seems to be an essential postulate.

3. Materials and Methods

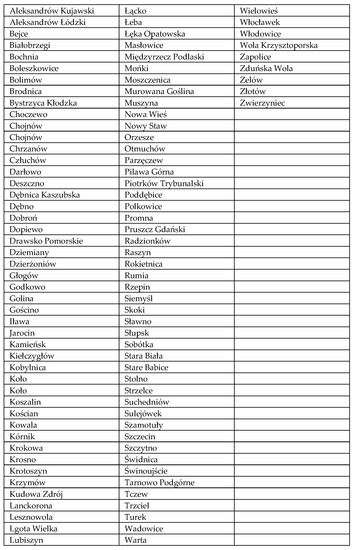

It was recognised that realising the research objective and answering the research questions required detailed, interdisciplinary research. In connection with the realisation of the aim of the article, all spatial plans in force in Poland at the local level were analysed at the end of 2020 (there were 104,720 plans). From this group, spatial plans for renewable energy sources were singled out (11,338 plans). From the indicated group, spatial plans authorising wind power investments were singled out. Only 529 plans enacted in 251 Polish municipalities were singled out. The plans identified in this way were the subject of the first research stage. It should be emphasised that selecting these plans was complicated and time-consuming (it required a preliminary analysis of all plans binding in Poland). However, it guarantees the inclusion of results concerning the whole of Poland. The distribution of municipalities adopting spatial plans from the perspective of Polish voivodeships was also determined (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Polish spatial plans at local level.

Three survey questions were formulated for all identified municipalities (which, between 2005 and 2020, adopted at least one plan containing a designation for a wind power plant). These questions were addressed to the municipalities (at the beginning of October 2022). Responses (received by 1 November 2022) were received from 103 municipalities. Of the municipalities, 40.87% during the study period have or had at least one plan adopted which (even if only in a minor way) allocated land for a wind power plant. The questions were answered by experts—municipalities’ spatial planning staff. The first question required a closed answer (yes or no answer). It concerned whether there were any spatial conflicts in the municipality regarding spatial plans for wind farms. It should be emphasised that the question concerned spatial conflicts related to adopting spatial plans for wind power plants. It did not, however, address other conflicts related to wind power plants.

The employees of the municipalities can quickly answer this question. They are responsible for piloting the process of enacting specific spatial plans (Appendix A). So, it is also to them that space users first direct any complaints about the content of spatial plans. Two further questions were open. They were concerned with identifying types of spatial conflicts related to wind power plants and spatial plans and how to resolve them. The literature on the subject provides knowledge about the previous directions of spatial conflicts related to wind energy (this was indicated in the literature review). However, it was considered more appropriate not to suggest specific answers to the respondents. Questions were sent by e-mail. As a general rule, responses to questions were addressed in this form. In cases where the authors considered it advisable, face-to-face interviews were additionally conducted. It applied to those municipalities where spatial conflicts were identified in the surveys (in response to the first question).

Another part of the research was the extraction of court rulings concerning plans allowing wind power investments. The data contained in the Central Database of Judgments of Administrative Courts in Poland were analysed. This database contains all judgments and decisions of administrative courts. The database predominantly contains justifications for the indicated judgments and decisions. It makes it possible to verify the category of plaintiffs, the charges raised, and the outcome of a given case (however, it should be emphasised that a large part of the data, including that concerning specific communes affected by the plan, has been anonymised). Admiralty courts are the courts dealing with complaints against spatial plans. In the database mentioned above of judgments, judgments were searched for—through a combination of words—with the words ‘spatial plan’ and ‘wind power plants’ in their sentences. This guaranteed that all court decisions in this area would be found. A total of 72 such rulings, issued between 2005 and 2021, were identified (Table 3). They are diverse: they include verdicts and decisions of the Provincial Administrative Court as well as judgments of the Supreme Administrative Court. From the perspective of the article’s purpose, the form of a given decision is less critical. The key point is that each of the indicated rulings ends (at least from a legal perspective) a specific spatial conflict concerning wind power plants in spatial planning. The rulings distinguish:

Table 3.

Description of the data used in the study.

- The year of the adjudication;

- The type of complaint against the plan—distinguishing between allegations that the plan violates the right to property (where such an allegation is formulated explicitly), allegations that the guidelines regarding the acceptable noise standard were exceeded, and formal allegations (regarding errors in the content of the plans);

- The form of the decision, distinguishing: (1) annulment of the plan in question in whole or in part, (2) upholding of the plan and dismissal of the complaint on grounds of merit, and (3) upholding of the plan and dismissal of the complaint on formal errors committed by the complainant.

Two classifications were undertaken in the group of court cases analysed:

- The first classification focused on the directions of the allegations formulated by the complainants. Two main groups were distinguished here: (1) allegations pointing directly to a violation of the right to property, and (2) formal allegations concerning the content of the spatial plan (its non-compliance with the Act). Of course, in practice, formal allegations often obscure the applicant’s dissatisfaction with the fact that (in their opinion) their property right has been restricted. In addition, a small group of cases was distinguished in which the allegations concerned the finding of a risk of exceeding noise standards by the investments specified in the plan;

- The second classification focused on the resolution/termination of the case itself, distinguishing: (1) cases concluded with the declaration of invalidity of the plan in whole or in part, (2) substantive acknowledgement of the complainant’s allegations as unfounded, and (3) rejection of the complaint for typically legal reasons (unrelated to the substantive assessment of the plan).

4. Results

4.1. Municipalities with Spatial Plans Allowing for the Location of Wind Power Plants

Firstly, the spatial plans in force at the end of 2020 (i.e., those adopted between 2005 and 2020), which determined the possibility of locating wind power plants, were identified. Therefore, it was necessary to analyse the content of all 104,720 spatial plans in force in Poland on a local scale. Out of such a large group, 529 spatial plans meeting the above criteria were identified (0.505% of all plans enacted in Poland). This small number already leads to the conclusion that at the national scale, the planning activity of municipalities on wind power plants is insignificant. It may be added that spatial plans concerning wind power plants were enacted in 251 Polish communes, i.e., 10.08% of the total number of communes.

Data for the whole country requires more detailed analysis. Therefore, Figure 1 shows the share of municipalities enacting spatial plans for wind power plants in the total number of municipalities for each Polish voivodeship. The results confirm the minimal activity of Polish municipalities in this respect. In some voivodeships, plans for wind power were either not adopted at all (Podlaskie) or adopted to a negligible extent (Podkarpackie). A (moderate) exception is the Lower Silesian and Pomeranian voivodeship municipalities, where more than 20% of the municipalities have adopted appropriate plans. According to the authors, the indicated results should be linked primarily to issues concerning local spatial policy. Other considerations play a much smaller role in the Polish system. This is also due to the aforementioned legal barriers related to the enactment of spatial plans for wind power plants (they hinder a broad economic analysis; a factor taken into account when enacting the analysed spatial plans could be the wind speed [52]. However, due to the large spatial variation, it would be difficult to relate such an analysis to the provinces as a whole and the results in Figure 1. This makes it all the more important (especially from the perspective of the article’s objectives) to analyse the determinants of local spatial policies.

Figure 1.

Percentage share of municipalities adopting spatial plans for wind power plants in the total number of municipalities for each province in Poland. Source: own elaboration.

Accordingly, short questionnaires containing three research questions were sent to the municipalities’ offices. The questions were addressed to 251 municipalities that had adopted spatial plans for wind power plants. Responses were received from 103 municipalities. The critical question was whether there were spatial conflicts in the municipality regarding spatial plans for wind power plants. It was primarily a question of the adoption stage of the plan. However, once the plan has been adopted, the conflict in question may be protracted. Its final stage is to file a complaint against the plan to the court.

These spatial conflicts were identified by representatives of 18 surveyed municipalities (i.e., 17.48% of municipalities whose representatives responded to the questionnaire). Thus, it is not the case that the mere proceeding of a plan for wind power plants always guarantees a spatial conflict in this respect. In many municipalities, such conflict can be avoided (Figure 1).

Where representatives of municipalities confirmed the existence of spatial conflicts, they were asked to:

- Provide a characterisation of these conflicts (and the topics they concerned);

- Provide a characterisation of how these conflicts were resolved.

The following research stage was a detailed analysis of spatial conflicts concerning spatial plans and wind power plants in the indicated communes (Figure 2). There is no doubt that the key reason for spatial conflicts is that the indicated spatial plans limit the possibilities of land use. Mainly since 2016, the enactment of a spatial plan for wind power plants entails the prohibition of development around a significant area surrounding the future wind power plant (an area equal to ten times the height of the wind power plant). In all municipalities whose interviewed representatives perceived spatial conflicts, this problem was present. In the Polish system, this issue is related to restricting the property rights of residents of neighbouring properties (in Poland, the right to develop land is part of the property right). The most frequently disputed restrictions concerned residential development. However, there are cases (e.g., commune of Łeba) when planned restrictions blocked the realisation of commercial investments, e.g., seaside hotels.

Figure 2.

Main reasons for spatial conflicts regarding spatial plans and wind power plants in the studied municipalities. Source: own elaboration.

The second reported reason for conflicts was the potential destruction of the landscape (reported in five cases). Threats to the health of residents and threats to the environment were also mentioned as reasons for conflicts (three cases each). However, these allegations were mainly linked to the first one. Allegations against spatial plans were expressed in various ways:

- Through the formulation of pre-litigation letters by specific space users—which happened more often;

- Through the organisation of local communities and various means of putting pressure on municipal authorities.

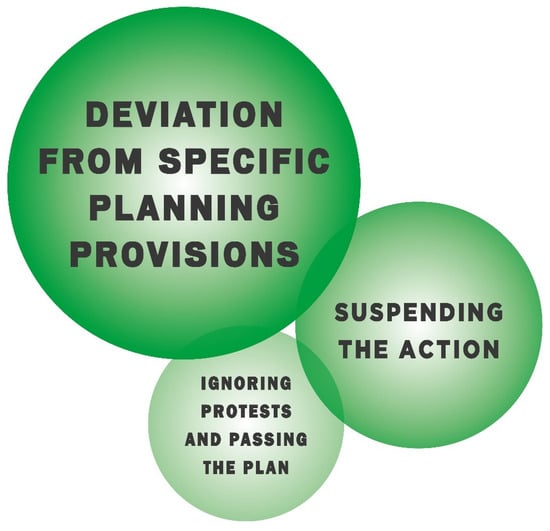

A large proportion of the representatives of the municipalities found it challenging to answer the question of ways of solving conflicts (Figure 3). In some cases (seven answers), it was pointed out that specific planning provisions were abandoned. This included either changing the specific content of the spatial plans or not adopting the disputed plan (in this situation, a plan for wind power plants in another area was adopted in the municipality). However, it should be emphasised that representatives of many municipalities were either unable to answer the question or indicated (five cases) that activities related to the spatial plans in question had been suspended. This suspension is linked to the legislator’s expectation to liberalise the guidelines for including wind power plants in spatial plans. There have also been cases (three) in which it was explicitly stated that the disputed spatial plans were adopted against the protesters’ will.

Figure 3.

Ways of solving spatial conflicts. Source: own elaboration.

4.2. Court Decisions on Spatial Plans Permitting Wind Power Investments

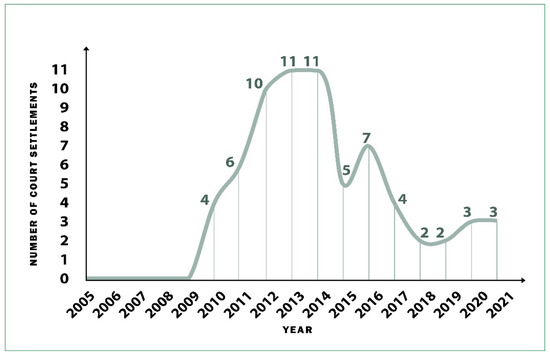

The following research stage involved an analysis of 72 court decisions issued between 2005 and 2021, obtained from the Central Database of Judgments of Administrative Courts in Poland. These rulings directly related to spatial plans enacted between 2005 and 2020, allowing for the realisation of wind power plants (the average case processing time is one year). Due to the anonymisation of data (also concerning the municipalities adopting spatial plans), it is only possible to make a partial direct reference of the indicated results to the results contained in the earlier parts of the article. Foremost, it can be pointed out that 13.61% of the spatial plans allowing the construction of wind power plants have been appealed to the courts. It is, therefore, not a gigantic scale, but it is nonetheless noticeable. However, the minimal number of nationwide spatial plans for wind power plants needs to be underlined (reminder). Municipal authorities often do not want to cause spatial conflicts and court cases. It is also why they decide not to adopt potentially controversial plans at the outset.

The first rulings on spatial plans related to wind power plants appeared in 2010 (Figure 4). There were not many such rulings per year (although it is still important to remember the relatively small number of such spatial plans). There has been a noticeable decrease in the number of such cases after 2016. Between 2010 and 2015, 65.278% of the group of all analysed settlements were issued. This is related to the fact that, in 2016, legislation introduced the developed distance guidelines necessary to be applied in spatial plans permitting wind turbines. This contributed to a decline in new spatial plans and was also reflected in the number of court cases. In the first period, there were decidedly more cases in which allegations of violation of property rights were made explicitly (57.477% of the total number of cases in this period). Between 2016 and 2021, the number of such cases decreased (42.857%). The number of cases in which formal allegations were made in both periods was similar (25.532% and 28.571%, respectively). In the first period, the number of cases in which the courts substantively assessed the content of the plans was higher (38.298% of cases in which the courts declared the plans invalid and 42.553% of cases in which the courts dismissed the plaintiffs’ objections). In the second period, there was a significant increase in the number of cases in which complaints were dismissed on formal grounds (23.809% of cases each, ending with both annulments of plans and substantive dismissal of complainants’ objections).

Figure 4.

Number of decisions on spatial plans and wind power plants between 2005 and 2021. Source: own elaboration.

Table 4 shows more cases in which formal objections were dominant (51.389%). Nevertheless, the number of cases in which the plaintiffs directly invoked their violation of the right to property (26.389%) is noticeable. The number of declarations of invalidity of plans and dismissal of complaints based on substantive (not formal) assessment is similar. Nevertheless, a difference should be noted. In the group of cases in which allegations of violations of property rights were made, there were significantly fewer final declarations of invalidity of plans (26.316%) than in the group of cases in which formal allegations predominated (45.94%). The latter allegations as a whole—from the perspective of the spatial plan complainants—should be assessed as far more successful. They significantly more often resulted in the annulment of the challenged spatial plan. On the other hand, in both groups, the number of cases that ended with substantive dismissal of complaints was similar (42.109% in the first group and 40.54% in the second group, respectively).

Table 4.

Objections to spatial plans examined by courts and conclusions of court decisions.

5. Discussion

The Polish spatial planning system leaves considerable planning freedom to authorities at the local level. It includes the decision to enact a spatial plan for a given area. In most cases, the enactment of a spatial plan could depend on the subjective decision of the municipal authorities. This could be the primary reason for the low number of adopted spatial plans for wind energy. This is also confirmed by the results in Figure 1, which show the variation in the percentage share of municipalities enacting spatial plans for wind power from the perspective of the Polish provinces. It is noticeable even in the case of a few plans. The Lower Silesian and Pomeranian voivodeships, on the one hand, and the Podkarpackie and Podlaskie voivodeships, on the other, can be contrasted here. Significant differences also occur due to the reluctance of local communities towards wind power plants, noticeable in the eastern provinces [47]. The thesis that serious spatial conflicts for wind energy, and even barriers to its emergence, are due to specific inhabitants’ reluctance and fears is confirmed [40]. However, the blame cannot be reduced to the local scale only. From a national perspective, numerous legal barriers related to wind energy implementation can be noted [53]. Thus, both the central government (by keeping severe restrictions in place) and local government (by not taking advantage of existing opportunities to support wind energy) contribute to blocking the broader implementation of wind power.

Another issue is verifying the scale and scope of spatial conflicts in municipalities that have adopted appropriate plans. The research shows that in the analysed group of communes, such conflicts are observed to a relatively small extent (17.48% of the communes who responded to the questionnaires). It is worth comparing the number of court cases concerning wind power plants to the total number of adopted spatial plans for wind power plants (13.61%). Thus, it can be assumed that in the current system, from the perspective of various criteria, the ‘conflictuality’ of spatial plans issues concerning wind power plants remains at several percent. It is not a large scale. Nevertheless, it still needs to be emphasised that a significant limiting factor is the current statutory framework—especially the guidelines on the requirement to restrict development in a large area around a proposed wind turbine. However, it is worth examining the officially presented reasons for spatial conflicts. The caveat is that these are specific conflicts directly linked to assessing a specific spatial policy instrument (i.e., the spatial plan assessment). Concerns about the negative impact of wind power plants on the landscape and the environment [34,35,36,37] appear on this occasion, but to a far lesser extent than allegations of restrictions on property rights. It is the latter allegations that are key in the spatial conflicts analysed. They are primarily part of the discussion signalled in the literature on balancing public and private interests [1,10], which in this case, is followed by the protection of individual property rights. Thus, this is a specific case in which systemic solutions determine the direction of allegations and approaches to spatial conflicts. To a much lesser extent, more serious spatial conflicts relate directly to environmental and landscape issues. It can be considered that the determination by the legal framework of the spatial planning system is a serious issue which requires a broader consideration in the literature [24,54,55,56,57].

It is important to note that municipalities have few ideas for resolving spatial conflicts. Too often, they declare that they are suspending work on the plan (and waiting for the central government to act, which does not happen). The above confirms the poor level of public participation in Polish spatial planning. It contributes significantly to the referral of spatial plans to the courts. Also, for this reason, the results concerning court decisions require in-depth commentary. As mentioned, Poland is an interesting case study in this respect. On the one hand, Poland has a broad role for courts in spatial planning. The courts assess spatial planning instruments also from the substantive (not only procedural) side. On the other hand, the position of property owners is solid in Polish spatial planning [58]. It manifests itself at various stages. Among other things, it concerns the possibility of raising objections to excessive planning interference. Such allegations were also made against spatial plans for wind power plants during the period under review. These allegations constitute grounds for declaring some spatial plans invalid. Nevertheless, two trends are worth noting. In line with the first trend, the number of complaints alleging that spatial plans violate real estate ownership is decreasing in the period under review. According to the second trend, formal allegations are more successful overall. It means that even when a specific property owner is not satisfied with the content of a spatial plan allocating land for a wind power plant and restricting its development possibilities, he does not directly reveal his motivation before the court. Instead, he looks for formal inconsistencies in such a plan. Formal inconsistencies can vary. Detailed planning provisions may imprecisely implement statutory guidelines (formulated at a higher level), or the content of spatial plans may be inconsistent with other spatial planning acts. Nevertheless, it is essential to underline that a significant part of spatial conflicts concerning spatial plans ends with the search for detailed formal irregularities of spatial plans. Of course, the search for such irregularities is because the complainants consider this to be the best way to challenge spatial plans. Thus, part of the spatial conflicts concerning property restrictions at the pre-court stage, at the court stage turns into conflicts concerning legal issues related to the legal scope of the plan. Undoubtedly, such a tendency is detrimental to the spatial planning system. It confirms the opinions appearing in the literature that the detailed inclusion of the provisions of spatial plans may block development [59,60]. It should be emphasised that the analysed phenomenon occurs on a small quantitative scale. Undoubtedly, with more liberal regulations and a more significant number of plans, there would also be a more prominent number of court complaints.

Attention should also be paid to the issue of economic efficiency of wind power investments. These issues are considered in detail at the stage of investment implementation. However, they should already be taken into account to a certain extent when enacting spatial plans. This is all the more so as the assessment of the economic viability of an investment also involves the local context to a significant extent [47,61,62,63]; note a significant link between energy efficiency and spatial structures, also shaped by regulatory solutions. Wąs [64] points out that under Polish conditions, economic efficiency is associated not only with objective factors (e.g., wind speed), but also with a positive attitude on the part of public authorities, openness to the realisation of such an investment. The research conducted [65] shows that on a local scale the approval of such investments occurs mainly after the positive economic consequences for the municipalities have been felt, i.e., after the wind power investments have already been located. It is in this context that a significant problem can be seen. The results of the conducted research confirm that the diagnosed legal and spatial barriers hinder a rational discussion about the economic efficiency of the investment and the appropriateness of a given location. Such analyses are carried out to a greater extent at the level of other actors (e.g., energy entrepreneurs) than at the level of spatial policy actors [66]. If we juxtapose this with the diagnosed regularities in other national systems, assuming deeper integration of development policies [67], the pro-problematic nature of the Polish system in this respect is particularly noticeable.

Another important issue is the spatial adjustment of the land to the potential localisation of wind power plants. This topic was the subject of a separate study in which some of the authors participated [47]. It showed generally unfavourable conditions in Poland for linear infrastructure and above-standard dispersion of development [68]. Deconcentration of development is associated with the occurrence of undeveloped, extensively developed areas. This is a factor exacerbating previous spatial barriers. Comparative studies of different countries support the thesis that spatial plans at the local level can play a diverse role [9], also important from a renewable energy perspective. Once the legal barriers in the Polish system have been reduced, it is therefore worth considering guaranteeing a broader economic efficiency analysis of the location of specific wind power plants in spatial plans.

The Polish case study shows that in less efficient spatial planning systems, the reasons for the limited spatial policy on wind energy implementation may be varied. In the Polish case, it is possible to point to both the conservative actions of public authorities at the national level and the low activity of municipalities. This is confirmed by the results of other studies on the inefficiency of public authorities in Polish spatial planning [48,69]. For this reason, it is impossible to determine which type of authority is better suited to coordinate planning policy for wind power plants. The solution is instead to introduce appropriate proportions and specific solutions. Undoubtedly, the statutory optionality of adopting spatial plans enables many municipalities not to make planning decisions in this respect. Similarly, detailed guidelines from a central scale provide an excuse to challenge spatial plans in the courts.

The research carried out has some limitations. These include:

- Limited awareness of the representatives of some surveyed municipalities of the spatial planning considerations in their municipalities;

- Anonymisation of some data on court rulings. Identifying the specific municipalities where complaints about spatial plans have been made is impossible.

However, this does not change the fact that this research provides essential information on spatial conflicts related to wind power plants. Further research directions can be identified as follows:

- An analysis of spatial conflicts regarding spatial plans for renewable energy sources in other countries—in this case, the research should be adapted to the specificities of national systems. Nevertheless, the proposals in this article can be an essential point of reference;

- An analysis of spatial conflicts concerning renewable energy sources occurring at a later (implementation) stage. In addition to conflicts concerning specific spatial plans, there are conflicts related to the issuing of subsequent decisions (building permits) for specific investments. At this stage, there are further spatial conflicts;

- To determine how to incorporate issues relating to the economic viability of wind turbine locations into the analyses carried out prior to the adoption of local spatial plans.

6. Conclusions

This article contains another part of the analysis of renewable energy sources in the Polish spatial planning system. It focuses on the most controversial wind power investments. The research shows that spatial plans determining the possibility of wind power plant construction are scarce in the Polish system. It is valid for all provinces, but provinces in the east of Poland are impoverished in this respect. The first reason is the statutory restrictions. The second reason is the passivity of many municipalities. This research determined the negligible number of plans for wind power plants. Spatial conflicts in terms of enacted spatial plans mainly concern discussions about restrictions on the rights of property owners. The main reason for spatial conflicts is dissatisfaction with restrictions (caused by spatial plans) on development and land-use possibilities. This is widely reflected in court cases. Municipalities responding to a given conflict often “suspend” work on a given plan, waiting for more favourable statutory changes (i.e., a reaction from the central authority). When a disputed plan is enacted, cases typically end up in court. Court actions involve allegations of violations of property rights and formal objections. The latter proves more successful (from a judicial strategy perspective). This is also how they are perceived.

The research results lead to the conclusion that balancing planning competencies between central and local government is a difficult task. It cannot be unequivocally determined that one of these authorities will be far better at achieving its objectives. A much more vital direction is to take care of the planning culture on a national scale and to apply certain types of regulations (e.g., obligatory spatial plans with a certain flexibility in planning). These regulations must be adapted to the specifics of national spatial planning systems, especially to their limitations. They should be geared towards broadening public participation and, consequently, towards a broader concern for the public interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.N.; methodology, M.J.N.; software, A.B., A.O.-P. and M.Ś.-S.; validation, M.J.N., A.B., A.O.-P., M.Ś.-S. and J.P.; formal analysis, A.B., A.O.-P., M.Ś.-S. and J.P.; investigation, M.J.N.; resources, M.J.N.; data curation, A.B., A.O.-P. and M.Ś.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J.N.; writing—review and editing, A.B., A.O.-P., M.Ś.-S. and J.P.; visualization, M.J.N.; supervision, A.B., A.O.-P., M.Ś.-S. and J.P.; project administration, M.J.N.; funding acquisition, M.J.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Municipalities with adopted spatial plans for wind power plants.

Figure A2.

Municipalities whose representatives responded to the research questions.

References

- Hersperger, A.M.; Ioja, C.; Steiner, F.; Tudor, C.A. Comprehensive consideration of conflicts in the land-use planning process: A conceptual contribution. Carpathian J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2015, 10, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Anup, K.C.; Whale, J.; Urmee, T. Urban wind conditions and small wind turbines in the built environment: A review. Renew. Energy 2019, 131, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaszke, M.; Foryś, I.; Nowak, M.J.; Mickiewicz, B. Selected Characteristics of Municipalities as Determinants of Enactment in Municipal Spatial Plans for Renewable Energy Sources—The Case of Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 7274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaszke, M.; Nowak, M.; Śleszyński, P.; Mickiewicz, B. Investments in Renewable Energy Sources in the Concepts of Local Spatial Policy: The Case of Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 7902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milczarek-Andrzejewska, D.; Wilkin, J.; Marks-Bielska, R.; Czarnecki, A.; Bartczak, A. Agricultural land-use conflicts: An economic perspective. Gospod. Narodowa. Pol. J. Econ. 2020, 4, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstrom, J.C.; Goetz, S.J.; Shortle, J.S. Land Use Problems and Conflicts: Causes, Consequences and Solutions; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 0-415-70028-0. [Google Scholar]

- Duray, B. Spatial Conflicts of Land—Use Changes on the Rural Areas of South Great Plain Region. Eur. XXI 2008, 17, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Bromley, D.W. Property rights and land use conflicts: Reconciling myth and reality, In Economics and Contemporary Land Use Policy; Johnston, R.J., Swallow, S.K., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 64–78. ISBN 9781936331659. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M.; Petrisor, A.-I.; Mitrea, A.; Kovács, K.F.; Lukstina, G.; Jürgenson, E.; Ladzianska, Z.; Simeonova, V.; Lozynskyy, R.; Rezac, V.; et al. The Role of Spatial Plans Adopted at the Local Level in the Spatial Planning Systems of Central and Eastern European Countries. Land 2022, 11, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von der Dunk, A.; Grêt-Regamey, A.; Dalang, T.; Hersperger, A.M. Defining a typology of peri-urban land-use conflicts—A case study from Switzerland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 101, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, A.; Sabir, M.; Pham, H.V. Socioeconomic conflicts and land-use issues in context of infrastructural projects. Asia-Pac. J. Reg. Sci. 2021, 5, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, C.; Huang, B.; Gan, M. Identification of Potential Land-Use Conflicts between Agricultural and Ecological Space in an Ecologically Fragile Area of Southeastern China. Land 2021, 10, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papamichail, T. Spatial synergies—Synergies between formal and informal planning as a key concept towards spatial conflicts—the case of tourism-oriented railway railway development in the Peloponnese. Ph.D. Thesis, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Schweiz, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibenath, M.; Wirth, P.; Lintz, G. Just a talking shop?—Informal participatory spatial planning for implementing state wind energy targets in Germany. Util. Policy 2016, 41, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandy, D.M.; Mörtberg, U. Spatial Planning for Wind Energy Development Using GIS. In Proceedings of the Stand Up Academy Conference 2018 in Knivsta, Stockholm, Sweden, 18–19 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, B. Continuous spatial modelling to analyse planning and economic consequences of offshore wind energy. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Lemus, R.; de la Nuez, I.; González-Díaz, B. Rebuttal letter to the article entitled: “Spatial planning to estimate the offshore wind energy potential in coastal regions and islands. Practical case: The Canary Islands”. Energy 2018, 153, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, D.P.J. The Energy Transition in Dutch Spatial Planning: Two Case Studies of Implementing Wind Farms in The Netherlands. Bachelor’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cellura, M.; Cirrincione, G.; Marvuglia, A.; Miraoui, A. Wind speed spatial estimation for energy planning in Sicily: Introduction and statistical analysis. Renew. Energy 2008, 33, 1237–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, N.; Odell, K. Spatial Planning for Wind Energy: Lessons from the Danish Case; Roskilde Universitetscenter: Roskilde, Denmark, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, R.P.; Hamza, N.; Norton, C.; Efstathiades, C.; Marciukaitis, M. Urban Wind Energy: Social, Environmental and Planning Considerations. In Proceedings of the Wind Energy Harvesting, Focusing on exploitation of the Mediterranean Area, Catanzaro, Italy, 21–23 March 2018; pp. 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Mazloomi, M.; Farzam, A. Application of Wind Energy in Urban Regional Planning Toward Ecological Sustainability (Case Study: Hashtgerd). Space Ontol. Int. J. 2016, 5, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, P.; Wu, S.Y.; Zhou, X.X. Determination of regional renewable energy planning scheme for urban power grid containing wind farm and its important impacting factors. Power Syst. Technol. 2013, 37, 334–341. [Google Scholar]

- Nadin, V.; Fernández Maldonado, A.M.; Zonneveld, W.; Stead, D.; Dąbrowski, M.; Piskorek, K.; Sarkar, A.; Schmitt, P.; Smas, L.; Cotella, G.; et al. COMPASS—Comparative Analysis of Territorial Governance and Spatial Planning Systems in Europe. Applied Research 2016-2018 Final Report; ESPON: Luxembourg, 2018; ISBN 978-99959-55-55-7. [Google Scholar]

- Reimer, M.; Getimis, P.; Blotevogel, H. Spatial Planning Systems and Practices in Europe: A Comparative Perspective on Continuity and Changes; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 1-317-91910-6. [Google Scholar]

- Alterman, R. Takings International: A Cross-National. In Takings International. A comparative Perspective on Land Use Regulations and Compensation Rights; Alterman, R., Ed.; American Bar Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010; pp. 1–75. ISBN 978-1-60441-550-5. [Google Scholar]

- Tosics, I. Urban Machinery: Inside Modern European Cities Edited by Mikael Hard and Thomas J. Misa. J. Urban Aff. 2010, 32, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoch, P.H. Energy without pollution: Solar-wind-hydrogen systems: Some consequences on urban and regional structure and planning. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1989, 14, 903–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, W.; Guo, C. An urban multi-energy system planning method incorporating energy supply reliability and wind-photovoltaic generators uncertainty. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 2019, 34, 3672–3686. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.S.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M.; Degirmenci, K.; Liu, A.; Kane, M. Leveraging the opportunities of wind for cities through urban planning and design: A PRISMA review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Daly, G.; Gleeson, J. Congested spaces, contested scales–A review of spatial planning for wind energy in Ireland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 145, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolsink, M. Contested environmental policy infrastructure: Socio-political acceptance of renewable energy, water, and waste facilities. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2010, 30, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felber, G.; Stoeglehner, G. Onshore wind energy use in spatial planning—A proposal for resolving conflicts with a dynamic safety distance approach. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2014, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peker, Z. Integrating Renewable Energy Technologies into Cities through Urban Planning: In the Case of Geothermal and Wind Energy Potentials of İzmir. Ph.D. Thesis, İzmir Institute of Technology Pub, İzmir, Turkey, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gourgiotis, A.; Kyriazopoulos, E. Electrical energy production from wind turbine Parks: The Finistere wind turbine Chart (France) and the Greek spatial planning experience. In Proceedings of the INTERDISCIPLINARY Congress on “Education, Research, Technology. From Yesterday Till Tomorrow”, Athin, Greek, 21–25 July 2007. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Lee, V. The Spatial Planning of Australia’s Energy Land-scape: An Assessment of Solar, Wind and Biomass Potential at the National Level. J. Digit. Landsc. Archit. 2016, 1, 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Manson, K.; Milbourne, P. Constructing a ‘landscape justice’ for windfarm development: The case of Nant Y Moch, Wales. Geoforum 2014, 53, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loring, J.M. Wind energy planning in England, Wales and Denmark: Factors influencing project success. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2648–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyridonidou, S.; Sismani, G.; Loukogeorgaki, E.; Vagiona, D.G.; Ulanovsky, H.; Madar, D. Sustainable Spatial Energy Planning of Large-Scale Wind and PV Farms in Israel: A Collaborative and Participatory Planning Approach. Energies 2021, 14, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidwell, D. The role of values in public beliefs and attitudes towards commercial wind Energy. Energy Policy 2013, 58, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, T.; Ramisch, K.; Feucht, T.; Reif, C.; Suda, M. Visual evaluations of wind turbines: Judgments of scenic beauty or of moral desirability? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 226, 104509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swofford, J.; Slattery, M. Public attitudes of wind energy in Texas: Local communities in close proximity to wind farms and their effect on decision-making. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 2508–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enserink, M.; Van Etteger, R.; Van den Brink, A.; Stremke, S. To support or oppose renewable energy projects? A systematic literature review on the factors influencing landscape design and social acceptance. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 91, 102740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawlikowska, A.P. Renewable energy in urban planning on the example of wind energy. Kwart. Archit. I Urban. 2013, 2, 159–178. [Google Scholar]

- Śleszyński, P.; Kowalewski, A.; Markowski, T.; Legutko-Kobus, P.; Nowak, M. The Contemporary Economic Costs of Spatial Chaos: Evidence from Poland. Land 2020, 9, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowski, T. Polityka urbanistyczna państwa–koncepcja, zakres i struktura instytucjonalna w systemie zintegrowanego zarządzania rozwojem. Stud. KPZK 2018, 183, 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Śleszyński, P.; Nowak, M.; Brelik, A.; Mickiewicz, B.; Oleszczyk, N. Planning and settlement conditions for the development of renewable energy sources in Poland: Conclusions for local and regional policy. Energies 2021, 14, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foryś, I.; Nowak, M. The malfunction of public authorities in the spatial planning system. Argum. Oeconomica 2022, 1, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.J.; Śleszyński, P.; Ostrowska, A. Orzeczenia sądów administracyjnych dotyczące studiów uwarunkowań i kierunków zagospodarowania przestrzennego gmin. Perspektywa polityki publicznej i geograficzna. Stud. Reg. I Lokal. 2021, 2, 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Cotella, G. Spatial planning in Poland between European influence and dominant market forces, In Spatial Planning Systems and Practices in Europe. A Comparative Perspective on Continuity and Change; Reimer, M., Getimis, P., Blotevogel, H., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 255–277. [Google Scholar]

- Solarek, K.; Kubasińska, M. Local Spatial Plans as Determinants of Household Investment in Renewable Energy: Case Studies from Selected Polish and European Communes. Energies 2021, 15, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasecki, A.; Jurasz, J.; Kies, A. Measurements and reanalysis data on wind speed and solar irradiation from energy generation perspectives at several locations in Poland. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E.; Sobczak, A.; Soboń, D. Wind Energy Market in Poland in the Background of the Baltic Sea Bordering Countries in the Era of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Energies 2022, 15, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitelaar, E.; Sorel, N. Between the rule of law and the quest for control: Legal certainty in the Dutch planning system. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getimis, P. Comparing Spatial Planning Systems and Planning Cultures in Europe. The Need for a Multi-scalar Approach. Plan. Pract. Res. 2012, 27, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, D.; Nadin, V. Shifts in territorial governance and the Europeanization of spatial planning in Central and Eastern Europe. In Territorial Development, Cohesion and Spatial Planning; Adams, N., Cotella, G., Nunes, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 182–205. ISBN 9780203842973 182-205. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M.J.; Lozynsky, R.M.; Pantyleyy, V. Local spatial policy in Ukraine and Poland. Stud. Z Polityki Publicznej 2021, 8, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Śleszyński, P.; Nowak, M.; Sudra, P.; Załęczna, M.; Blaszke, M. Economic Consequences of Adopting Local Spatial Development Plans for the Spatial Management System: The Case of Poland. Land 2021, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savini, F.; Aalbers, M.B. The de-contextualisation of land use planning through financialisation: Urban redevelopment in Milan. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2016, 23, 096977641558588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni, S.; Buitelaar, E.; Sorel, N.; Cozzolino, S. Simple Planning Rules for Complex Urban Problems: Toward Legal Certainty for Spatial Flexibility. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2020, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.J.; James, V.U.; Golubchikov, O. The Role of Spatial Policy Tools in Renewable Energy Investment. Energies 2022, 15, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeglehner, G.; Neugebauer, G.; Erker, S.; Narodoslawsky, M. Integrated Spatial and Energy Planning: Supporting Climate Protection and the Energy Turn with Means of Spatial Planning; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-31870-7. [Google Scholar]

- Teschner, N.A.; Alterman, R. Preparing the ground: Regulatory challenges in siting small-scale wind turbines in urban areas. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 1660–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnatowska, R.; Wąs, A. Wind Energy in Poland—Economic analysis of wind farm. E3S Web Conf. 2017, 14, 01013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacejko, P.; Wydra, M. Energetyka wiatrowa w Polsce–realna ocena możliwości wytwórczych. Rynek Energii 2010, 6, 100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Cowell, R.; De Laurentis, C. Understanding the effects of spatial planning on the deployment of on-shore wind power: Insights from Italy and the UK. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 2021, 1987866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni, S.; Antoniucci, V.; Bisello, A. Local energy communities and distributed generation: Contrasting perspectives, and inevitable policy trade-offs, beyond the apparent global consensus. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hołuj, A.; Ilba, M.; Lityński, P.; Majewski, K.; Semczuk, M.; Serafin, P. Photovoltaic Solar Energy from Urban Sprawl: Potential for Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 8576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.J. Niesprawność władz publicznych a system gospodarki przestrzennej. Stud. KPZK 2017, 175, 1–256. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).