Abstract

Encouraged by the European Union, all European countries need to enforce solutions to reduce non-renewable energy consumption in buildings. The reduction of energy (heating, domestic hot water, and appliances consumption) aims for the vision of near-zero energy consumption as a requirement goal for constructing buildings. In this paper, we review the available standards, tools and frameworks on the energy performance of buildings. Additionally, this work investigates if energy performance ratings can be obtained with energy consumption data from IoT devices and if the floor size and energy consumption values are enough to determine a dwellings’ energy performance rating. The essential outcome of this work is a data-driven prediction tool for energy performance labels that can run automatically. The tool is based on the cutting edge kNN classification algorithm and trained on open datasets with actual building data such as those coming from the IoT paradigm. Additionally, it assesses the results of the prediction by analysing its accuracy values. Furthermore, an approach to semantic annotations for energy performance certification data with currently available ontologies is presented. Use cases for an extension of this work are also discussed in the end.

1. Introduction

Driven by the increasing concerns regarding climate change, the European Union developed a legal framework for energy efficiency measures [1], in the form of directives, to lower the impact on our environment. According to the statistics published in the “European Energy Efficiency Directive” almost 50% of the European Union’s final energy consumption is used for heating and cooling, of which 80% is used for residential and non-residential buildings [2]. This makes the building sector an important energy consumer. These numbers motivate the European Union to promote actions for the refurbishment of the European building stock to achieve higher energy efficiency values. The current European directives encourage near-zero energy consumption as a future essential requirement for construction. It has been proven, e.g., with the Passive House standard, that buildings can use much less energy.

The term energy efficiency stands for “using less energy inputs while maintaining an equivalent level of economic activity or service” [1]. In other words, efficiency is the ratio between a costly input and the desired outcome. In the case of buildings, desired outcomes may be:

- thermal comfort,

- adequate light levels, and

- air quality,

Whereas costly inputs may be:

- the amount of gas used by boilers,

- the amount of electricity used for lighting, and

- the amount of electricity used for mechanical ventilation systems.

This work along with the resulting application aims at helping building occupants, building owners and municipalities in properly classifying homes based on the available data of their buildings. The goal of this work is to create data-driven models, which help owners and future tenants to control their buildings. In order to reach this state, first of all, buildings must be investigated paying special attention to heating (heating and domestic hot water—DHV), electric energy consumption and possible solar energy gains (e.g., gathered from photovoltaic solar panels [PV] or passive solar systems).

These considerations have a significant influence on three main aspects:

- limitation of environmental impact,

- becoming more self-sufficient, and

- awakening the inhabitants’ awareness in terms of energy consumption.

They have an impact on each other and should be treated holistically. This research aims at finding a solution for these challenging problems.

In this regard, we analyze two aspects:

- Is there a correlation between building data and energy performance rating?

- Based on the available data, is it possible to predict a rating for an unknown, not yet rated dwelling?

According to the European Energy Efficiency Directive, each member state must renovate 3% of its building stock yearly to improve energy consumption. The goal by 2050 is to renew the building stock into near-zero energy buildings [2]. The above-mentioned considerations aim at aiding these initiatives of the European directives.

The paper is organized as below:

- In Section 2, the available standards, tools, and frameworks on the energy performance of buildings are reviewed comprehensively.

- Section 3 lays the groundwork for the research problem—if energy performance ratings are directly correlated to the energy consumption data and if the floor size and energy consumption values are enough to determine a dwellings’ energy performance rating. This follows the proposal of a data-driven kNN classification-based prediction tool for energy performance labels.

- In Section 4, an approach to semantic annotations for energy performance certification data with currently available ontologies is offered.

- In Section 5, results of proposed approach are presented emphasizing data analysis and prediction metrics.

- In Section 6, conclusions are made based on observations and future scope is provided for research community to follow.

2. Background and Related Work

Smart Buildings and the Smart Readiness Indicator are the current flagship towards energy-efficient buildings. With the usage of machine learning techniques and semantic modelling, the performance of the Smart Building’s technical equipment can be improved. The latter is shown by the projects SESAME [3] and Entropy, and the building modelling and simulation tools presented in this section.

2.1. Ontology and IoT

An ontology is a description of concepts for a specific knowledge domain and their relationship to each other. A semantic model uses these concepts and relations to describe the content and meaning of data. Semantic models enable semantic reasoning, meaning asking and answering questions about data in a natural way. Instead of thinking in queries by matching ids and table names, we reason in relations and links between data objects. The SESAME [3] project incorporates semantic models for the advance metering systems of Smart Buildings. The Entropy project tries to sensitize tenants to the consumed energy of their building by providing detailed information on their energy consumption. The Entropy project also shows that occupant behavior is crucial for the energy performance of dwellings. The latter leads to the question: if energy performance ratings are closely related to the energy measurements, then is the energy performance rating influenced by the tenants’ behavioral patterns?

By looking at the state-of-the-art, we can see the complexity of the topic of energy-efficient buildings. The Internet of Things (IoT) jumps on board in lowering the impact of human actions on the environment. One such technique that is already being exploited is home automation. Buildings incorporating smart meters, alongside sensors and actuators, record and even optimize the dwellings’ energy consumption. Smart meters drive automated measurement of the energy consumption of a building, thus providing capability to provide accurate and frequent billing details. In the European Energy Efficiency Directive on building energy, a minimum of 80% of energy consumers should be equipped with smart metering systems by 2020 [4]. In the future, artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies might enhance and create knowledge from data sourced from the smart meters to handle and improve energy consumption levels of buildings autonomously [5]. The interconnection of homes, offices, data centers, warehouses and the public infrastructure has made Smart Cities a reality. Major European cities are working on ideas and prototypes in an active manner to accomplish the vision of Smart Cities. An example is the city of Innsbruck, where “the vision of a holistic energy identity in 2050 is only possible by an overall consideration of the city as a system in which energy, buildings, supply networks, mobility, information and people are viewed in an integrated manner” [6].

2.2. Frameworks

Smart Homes are dwellings technically equipped to monitor and improve their energy consumption and provide smart services to their occupants. Extending this idea to buildings, we have the term Smart Buildings. Smart Buildings are energy-efficient, safe, technically integrated, and sustainable buildings that are constituents of larger energy grids. The following sub-sections discusses the existing frameworks/indicators in more detail.

2.2.1. Smart Readiness Indicator

The Smart Readiness Indicator (SRI) is a rating that reflects the capacity of a building to operate energy-efficiently, to be a valuable component of smart energy grids, and to adapt to the occupant’s needs. The SRI concept was introduced in the EU directive of 2018 [2] and enhanced in 2020 [7]. The SRI assessment procedure considers all the smart ready services available in a building. Each of these services is analysed and graded according to its smartness (integration, flexibility, performance). Some services might function better regarding the occupant’s needs or the grid situation, and some services might perform worse. These functionality levels describe how smart a service is. Therefore, the Smart Readiness Indicator is an addition to the already available energy performance ratings [8]. Further, a proposal for a methodology was presented in a technical study [8] commissioned by the EU. Eight viable criteria for determining the SRI were found to be of most significance, these are:

- saving capabilities (for instance—better control of room temperature settings),

- flexibility towards the energy grid,

- self-generation of energy,

- occupant’s comfort (thermal, acoustic, visual),

- convenience (e.g., less manual settings needed to be done by users),

- a healthy indoor climate,

- maintenance and fault detection, and

- user-friendly feedback to occupants.

2.2.2. Integration Framework for Smart Homes

The SESAME project facilitates an energy-aware home automation system by offering a plug-and-play solution enabling features such as integrating building automation systems with the advanced metering systems of a building [3]. Semantic Rules are exploited to depict how appliances within the environment will be operated. These rules enable reasoning on the measured data. For the SESAME Project, a total of three ontologies were designed [9]:

- The Meter Data Ontology facilitates communication protocols for data exchange with the metering equipment.

- The Automation Ontology comprises general concepts such as Resident and Location, but also concepts in the automation and the energy domain, such as Device (with consumption per hour, power on-of status, peak power), and Configuration (of appliances).

- The Pricing Ontology facilitates the optimal tariff model for a specified time and energy load by providing a weighted criteria which can then be used by the reasoning engine for choosing the best tariff model.

2.2.3. Energy Consumption Awareness Framework

The Entropy Project aims to sensitize occupants to the consumed energy of their dwellings. These dwellings are supplied with smart sensors that collect energy consumption data. A specially developed software helps tenants to be informed about their energy consumption. The project focuses on the tenants’ dynamic behaviour and suggested lifestyle changes to reduce energy consumption via their services by providing a user-friendly experience. As described in the article [10], the Entropy services collect and process real-time data from sensor nodes while managing previously sourced sensor data. Semantic Web technologies such as semantic models and ontologies are utilized for a unified data representation of the historical sensor data. On the one hand, the Energy Efficiency Semantic Model represents the energy consumption data collected from the sensors and on the other hand, the Behavioural Semantic Model has its focus on the energy consumption profile of end users. These two models facilitate the further management and exploitation of the collected sensor data. Using a LinDA workbench, the semantically annotated data from the semantic models are transformed into semantically linked data [11]. This method is useful to the building sector because it compares the collected data in exchange with other open linked data like meteorological data. The data is serialized in JSON-LD format, which is a lightweight linked data format. The recommender engine behind Entropy is based on the Drools framework [12]: a rule-based management system, where a rule is expressed by a condition element and a recommendation template.

2.2.4. Energy Consumption Prediction Framework

Building thermodynamics are complex non-linear phenomena, which are strongly influenced by building operating modes, building fabrics, weather conditions as well as occupant schedules [13]. There is a need for better prediction algorithms and tools. Some predictive data-driven models are presented in [13], which are formulated with machine learning (ML) techniques. The ML models are trained on a selected set of data and tested on another mutually exclusive set, and consequently, the algorithm applies what they learn during the training process. The predictive models are of two categories: on one side, the black-box [14], in contrast to white-box [15] models (e.g., SVR, Regression Forest [16]) and on the other side, the grey-box models (e.g., Gaussian). The mentioned research work proves that the black box model predictions, applied to temperature values outperform the grey-box models, which are applied to energy consumption values because the first ones captured human behaviour. Human behaviour has a greater impact on the energy consumption than the envelope of the building. Among the black-box methods, the Random Forest algorithm has the best prediction results as per conclusions in [13].

2.3. Tools

Some of the models and frameworks mentioned before are integrated into comprehensive set of tools and applications as discussed below:

2.3.1. Building Energy Simulation Software

A building energy simulation tool creates “a digital model representing a virtual building where the user can select and specify in detail the parameters that influence the building performance, with resulting performance predictions that are as close to reality as possible” [17] Most of the energy simulation software e.g., EnergyPlus [18] and the Transient System Simulation Tool (TRNSYS [19]), are based on white-box simulation. They simulate a building based on the explicitly introduced building details and calculate the building energy consumption by using complex mathematical formulae [13]. EnergyPlus is a mature and elaborated simulation software for buildings. It is targeted at expert users, engineers, architects, and researchers. EnergyPlus was used for evaluation of results, e.g., in the paper [20] and many more. With the help of EnergyPlus, a free, open-source, cross-platform software, expert users can model energy and water consumption, lighting, air quality and much more. The most important feature of EnergyPlus is that its use is possible in machine-to-machine communication. The building data are fed to the program with the help of input files, and the results of the program calculations are produced in output files [20]. TRNSYS is a wildly used simulation environment, developed mainly for thermal and electrical control systems, but it can also be used for other transient systems. In contrast to EnergyPlus, TRNSYS is a commercial tool. TRNSYS is a versatile component-based software system. Component models may be selected from the built- in libraries or written by the user and linked to the main TRNSYS simulation model. It also supports machine- to-machine communication since it can connect to the interface of other systems or simulation tools [21]. The most important capabilities of a simulation tool are accuracy, usability, data-exchange, and database support [22]. This kind of system requires detailed information of the simulated building, information that is not always available [13]. The lack of complete information is one of the causes of the so-called performance gap in buildings [23].

2.3.2. Building Certification Software

A building certification software calculates energy performance and ratings based on annual energy use, e.g., annual kilowatt-hours used per square meter (kWh/m2/year) or related CO2 emissions, measured in kilograms of CO2 per square meter (kgCO2/m2/year). Certification software ensures the quality of the certification as it facilitates standardised calculations. A comprehensive software system may also provide recommendations for upgrading the building to improve efficiency [24]. As an example, the EDGE-App is a comparative software and a certification utility. This application is location and climate aware. Additionally, it suggests possible certification companies, including their contact data, after the user enters the available building measurement values.

2.3.3. Building Management Systems

The information gathered from smart meters and the information displayed on the energy bills might be too technical for normal users; therefore, researchers are trying to find solutions for improved visualization methods which are more appealing to the end-user, with the end goal to motivate the user to save energy. The technical equipment is not aware of the interests or the technical expertise of the user.

Researchers have investigated which kind of visualization type tenants react to the most. As reported in [25], the behavior of tenants was observed in the form of a virtual game, where users could see the energy consumption of their virtual flats and define some rules (e.g., shut down the light after 22 o’clock). These rules were automatically applied to the virtual flat, and their effects on the energy consumption were inspected.

Among the researched visualizations for the consumed energy, some were:

- the amount of generated CO2,

- the number of trees needed to absorb the generated CO2,

- the amount of money spent, and

- comparison to other users of the game.

2.3.4. Energy Efficiency Testing Framework

Intending to increase the quality and the accuracy of energy analysis tools, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) in the US developed the Building Energy Simulation Test for Existing Homes (BESTEST-EX) [26]. It is a test method whereby an energy performance software program is tested against itself for its performance in modelling and prediction of energy consumption.

BESTEST-EX offers two types of test cases: building physics [27] and utility bill calibration [28].

In the building physics test cases, the model inputs, which includes the building data, is fixed by the test case. The resulting predictions for energy consumption are then compared to the NREL predictions.

The utility bill calibration test case uses empirical data from energy bills of buildings in the US. The software under test receives as input such data and then predicts energy savings. Again, the results are then compared to the NREL reference predictions. These reference predictions are calculated with state-of-the-art simulation tools such as EnergyPlus.

The tests comprised in BESTEST-EX are included in the ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 140, “Method of Test for the Evaluation of Building Energy Analysis Computer Programs”. BESTEST-EX can help diagnose why energy performance software has errors. The data format specially developed for this kind of energy data is called Home Performance Extensible Markup Language (HPXML). HPXML is an open data standard published by the Building Performance Institute (BPI) that makes it easier to collect and transfer home energy data among software tools [28]. HPXML comprises a standardized data dictionary and a standardized data transfer protocol [29], as presented in the following two paragraphs.

2.3.5. Building Assessment Simulation Software

Building simulation tools models include the important aspects of the physical behavior of buildings. A classification of building simulators can be found in [30]. The classification criteria are:

- How is the model created?

- What is the level of dynamism of the model?

- What is the complexity of the model?

The weather and the occupants’ behaviour significantly impact the comfort level of buildings; however, they are hard to predict. The designs that consider these uncertainties are more reliable [30]. Uncertainties are categorized as:

- environmental: climate variability;

- quality of building materials and the quality of finishes; and

- occupancy dynamics: windows openings, the use of appliances, heating and cooling preferences or occupancy.

The more detailed the recommendation, the better the chances that the owners would implement the advice. Recommendations provided by building professionals are costly as they require a building inspection. However, human interaction and details for the upgrading measures might motivate owners to act on the recommendations. The costs can be reduced if the recommendations are automatically generated by assessment software. However, such recommendations could be less specific, which could weaken the impact of the advice [24].

2.3.6. Collaboration on Energy Performance

The European Commission funded the BUILD UP platform to promote and facilitate energy consumption saving measures in buildings. This platform offers information on best practices, available technologies, and the current legislation for energy reduction. The BUILD UP platform is open to building professionals, local authorities, and citizens, who are encouraged to share their knowledge.

A complex collaboration research project funded by the International Energy Agency, the European Union and the European Interreg Alpine Space Project ATLAS namely, IEA-SHC Task 59, focuses on exchanging knowledge about energy and CO2 saving methods specifically in historical buildings. The outcome of this project will be the Historic Building Atlas, a database for best practice examples of energy performance measures in historical buildings.

2.4. Semantic Models

There are some gaps in the interoperability of Building Information Modelling (BIM) tools. Semantic Enrichment Engine for Building Information Modeling (See BIM) is a framework for enriching Industry Foundation Class (IFC) exchange files with semantic concepts, which are inferred by semantic rule-engines from the building model’s information [31]. The latter process is called semantic enrichment, where the semantics of a building object are composed of three components: their form, function, and behavior. The inference rules condense the subject matter knowledge of domain experts. The rules are defined as IF-THEN statements using a predefined set of object types and operators. The operators include functions for reading the existing building model, testing for geometrical and topological relationships, and for creating new objects, properties, and relationships. The rules are defined in a format understandable to domain experts [31]. These rules use two types of IF clauses:

- Clauses that test for features of a single object and

- Clauses that test for topological relationships between pairs of objects.

Rules used to identify object types often depend on the prior identification of other relevant, related objects. If the ruleset is set up improperly, some objects will not be identified, and the semantic meaning will be partially lost. Sometimes, interdependency within the rules can result in infinite loops. A method to define proper rule sets is presented in [31].

The rich data sets can be analysed, explored, and processed by a formal query language including geospatial languages [32], e.g., GeoSPARQL [33] or Spatial SQL [34], handling spatial data. However, these languages are not suited for 3D representations, specifically for the qualitative spatial predicates [35]. Consequently, a BIM query language was developed named QL4BIM (Query Language for 4D Building Information Models) [30]. QL4BIM includes new domain- specific operators for expressing topological, directional, and temporal aspects.

The semantic enrichment engine (SEE) uses forward chaining to infer new facts about a model.

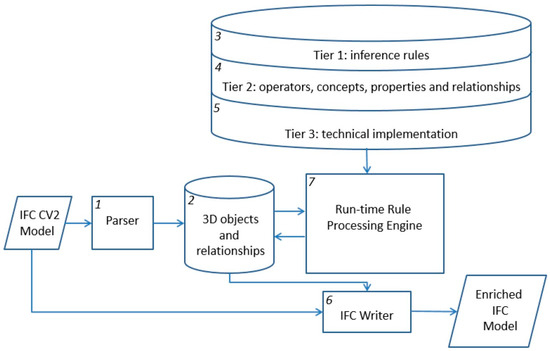

As presented in Figure 1, the components of the semantic enrichment engine include the following [31]:

Figure 1.

Semantic Enrichment Engine (SEE) architecture [9].

- (1)

- a parser, which reads IFC model instance files exported from BIM tools.

- (2)

- an internal run-time database that stores parsed objects, relationships, and their attribute values.

- (3)

- inference rules, which are edited by domain expert users and kept in a file storage system.

The rule processor uses forward chaining. In this way, a derivation of any new fact can trigger further new inferences. The processing ends when no further facts can be inferred. Rule-sets are described using a three-tiered architecture [31]:

Tier 1—the rule statements. The lexical components are logical and relational operators, constants (defined in Tier 2), domain-specific concepts and relationships and product model schema entities.

Tier 2—the vocabulary. It consists of concepts, properties, and relationships. It comprises the operators used for compiling the rules in Tier 1.

Tier 3—the machine-readable code of the Tier 2 operators.

3. Methodology

The purpose of our methodology is to offer predictions of energy efficiency ratings for dwellings. This is possible with the help of machine learning techniques (K-Nearest Neighbors classification method). For the prediction, the idea is to group the available dwelling data into 7 clusters (i.e., from A to G), according to the number of currently possible EPC ratings. Then, for each new dwelling, represented by the input tuple t, the closest cluster centre c is computed. The label of the closest cluster centre is then the EPC rating label r, appointed to the input tuple t (1).

| t = (floor_area, energy_consumption) |

| d(t): t → c |

| r(t): d(t) → c.label |

Clustering methods group a set of data into subsets, called clusters. The data entries grouped inside a cluster should be as similar as possible to each other. However, they should be as different as possible compared to other clusters’ data entries. The similarity in clustering methods is determined by the distance of the data points to each other. The data entries are represented as data points in an n-dimensional space. In our case, the data points were tuples (floor area and energy consumption) represented in a 2-dimensional space. The number of clusters (often marked as k) is called the cluster cardinality. For clustering methods, finding the right cardinality might be a wild guess, but there exist fitness methods (e.g., silhouette method) that approximate the right number of clusters. In both clustering methods, the goal is to find good centroids (cluster centers). The two clustering methods that were tried out were k-means and k-medoids. In k-means the aim is to minimize the average squared Euclidean distance [17] of each data point to its computed centroid, where the centroid is not necessarily one of the actual data points.

The k-medoids is a variant of k-means, but instead of computing the centroids, a data point is designated as the centroid to which the distance to the other data points in the cluster is kept minimal. K-medoids is less sensitive to outliers than k-means. In the case of predicting energy performance ratings, the above methods did not help us to achieve results and they were replaced by a different machine-learning method. Nevertheless, for the case of proving that fewer rating labels are appropriate, we continue with presenting the workflow and the data analysis performed at this stage.

Fitness methods measure how well the data points fit into the designated cluster. For calculating the optimal number of clusters, rating labels, the following fitness metrics [13] are used:

- the elbow method;

- the Silhouette Coefficient;

- the Calinski-Harabasz score.

The Silhouette Coefficient shows how similar a data point is to its own cluster. The higher the value, the more the data point fits into the assigned cluster. For each data point, the Silhouette Coefficient [18] is

where

- a: mean intra-cluster distance

- b: mean nearest cluster distance.

The Calinski-Harabasz Score [11] or Variance Ratio is the ratio between the within-cluster dispersion, and the between-cluster dispersion, where the dispersion is the sum of distances squared.

3.1. The Prediction Algorithm

In order to predict energy performance ratings, the kNN (k-Nearest Neighbours) classification algorithm is used in this work.

The kNN classification algorithm consists of assigning a new unseen data point to the majority classification class of its k nearest neighbours. The neighbours themselves are already classified and are part of the training data. The neighbours are computed using a similarity measure, representing the distance between data points; the smaller, the better.

The computing power is quite high, and a long response time for requests triggered by the user interface or by the REST calls is not feasible. In consequence, the prediction algorithm is split into two parts. These are presented in the next paragraphs.

In the first part of the prediction algorithm, we load the data from the database and prepare it. The preparation consists of:

- Feature scaling, where the data point values are transformed to the same value range. For this purpose, the StandardScaler is used, which subtracts the mean and scales it to unit variance, meaning it divides all values by the standard deviation.

- Splitting the data into training data (80%) and testing data (20%).

A classification model is created with the scikit-learn’s kNN algorithm, based on the prepared data. For calculating the similarity, the Euclidean distance is used. The resulting classification models are kept to be used on-demand in the second part of the prediction algorithm.

3.2. Semantic Annotation

The data model developed for the prediction algorithm may be used as a data model for energy performance certificates. Additionally, this data model can be enriched with semantic annotations and serve as the base for semantic reasoning. With a LinDA Workbench, data can be annotated with standard vocabularies and visualised as linked data. After some difficulties importing the needed dependencies and deploying the source code, the idea of using this promising tool was dropped, due to technical difficulties in setting up the application. We pursued a manual annotation instead.

At the time of writing, no dedicated ontology was available for energy performance certificates. Nevertheless, we tried two approaches:

- the schema.org vocabulary, and

- the PXL open standard.

4. Implementation

This section presents details about the implementation for our energy efficiency rating application including the data importer and the prediction logic.

The Data Import

For the basis of the prediction system, we looked for datasets that include energy performance data. Of particular interest were datasets with energy consumption measures and EPC ratings.

There were some open datasets available with energy consumption data; however, just a few of them included EPC rating data. For this work, we settled on the governmental open datasets containing energy consumption measures and EPC ratings from

- England

- France

- Scotland

- Ireland

These datasets are offered as CSV data files that contain a variety of building properties (e.g., building type, address, floor area, carbon emissions). Only the properties relevant to our purpose were extracted and imported into the applications’ database. A custom CSV-Importer accomplished the extraction, selection, and persistence of the data. This importer read each CSV file and imported the required fields into the database as a JSON formatted object. The database is a NoSQL MongoDB database, hosted on the MongoDB Cloud platform.

Since each country implements a different EPC rating scheme, i.e.,

- Scotland: RdSAP

- Ireland: BER, Dwelling Energy Assessment Procedure (DEAP)

it was considered appropriate not to mix the data and handle each country separately to have a better chance for a valid rating prediction.

Additionally, each country collected data for different dwelling properties. Consequently, this meant that for each country, a dedicated data mapper had to be implemented. As part of the importing algorithm, these mappers selected the required properties and mapped them into a global data structure. As a comparison, the number of building properties available in the original datasets for each country was:

- England: 83

- France: 21

- Scotland: 49

- Ireland: 202

In the first version of the application, the selected data field values for floor area and energy consumption were imported in a one-to-one ratio, meaning that the double values for floor area (e.g., 71.25 m2) and energy consumption (e.g., 228.78 kVh/m2/year) were imported as such. In a later iteration, to improve the prediction calculations, these values were converted into integer values (e.g., 71 resp. 228). The data accuracy was lowered to achieve a better prediction. Therefore, approximately 20% more data entries fit into the database than with the first version. The increase of imported data did not improve the prediction considerably, indicating that the originally imported data was representative of the whole dataset.

Additionally, further adjustments were made while importing the original data. For example, in the case of Ireland, the BER rating scheme offered granular ratings (i.e., A1, A2, A3, B1, B2, B3, C1, C2, C3, D1, D2, E, F, G). Consequently, our importer needed to map the granular ratings to the more generally used ones (i.e., A, B, C, D, E, F, G) as an effort to standardise the input data.

To sum up, for each country, an individual importer was developed to read the country-specific CSV files. For each country, a separate database was created to preserve the correlation between the rating values and the rating methodology and train the prediction model individually for each country and consequently offer country- specific predictions.

There were a few reasons why not all the original data were imported into the database:

- The freely available storage on the MongoDB Cloud platform is finite (i.e., 512 MB); in the case of England, this resulted in fewer imported data entries (Table 1).

Table 1. Imported data amount.

Table 1. Imported data amount. - The importer excluded dwellings with missing values for floor area, energy consumption, or EPC rating; this decreased the number of valid entries for France, Scotland, and Ireland.

- To achieve an evenly distributed dataset, sequentially every 3rd or every 10th valid entry (depending on the country) was imported (Table 2).

Table 2. Imported data distribution.

Table 2. Imported data distribution.

An overview of the number of imported dwellings is displayed in Table 1 below.

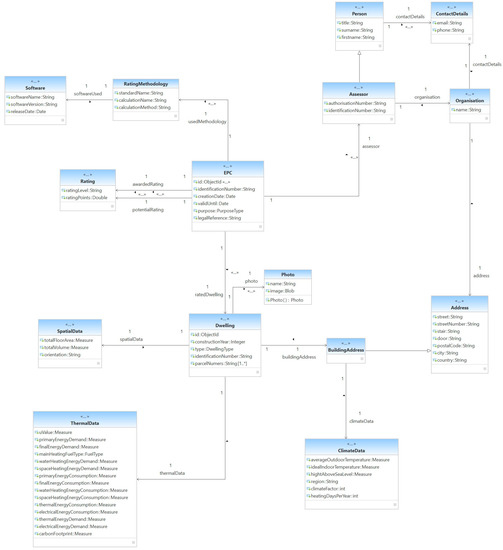

Although we have for each country a separate database, all databases have the same database schema based on our newly developed model. This model consists of 60 data fields and its data structure is presented as a UML class diagram in Figure 2. Our model comprises most of the information displayed on an energy performance certificate.

Figure 2.

UML class diagram for EPCs.

A list of the most important classes of our EPC model, grouped by domain is as follows:

- Energy Performance Certificate—modelled as the top-level class i.e., EPC, contains information such as identification details and the certification’s validity. It is linked to all other subclasses that represent details about the dwelling, the issued rating level, or the issuing authority.

- Energy Performance Rating—modelled as three classes: Rating, Rating Methodology and Software. On some certificates (e.g., for Ireland), the rating comprises two values: the rating label and the corresponding rating points. Additionally, the details of the used rating methodology or software are available in the open data (for Ireland and Scotland). Our database contains rating labels for each dwelling since they are essential for this work.

- Issuing Authority—modelled as classes: Assessor, Organization, Person, and Contact Details. A certified assessor issues an energy performance certificate. The information about the assessor (identification, contact data, and affiliation) are mandatory on an energy performance certificate; however, this data is mostly closed data and is not available in our imported datasets.

- Dwelling—details about the rated dwelling such as identification, construction year, type (e.g., house, flat), address, photograph, etc. Some datasets (e.g., France) offer geographical and climate data; this is useful, e.g., for future use cases where solar energy can be of importance.

- Energy Consumption—modelled as class ThermalData. It comprises measured or predicted energy consumption data. Some open datasets offer measurements for general energy consumption, whereas other datasets offer differential data for water and space heating energy and even electrical energy. Additional details such as heating fuel type or carbon footprint can be used for future use cases.

- Floor Area—is part of the class SpatialData. For our purpose, the dwellings’ floor area is of importance; nevertheless, we also modelled data for volume space and geographical orientation since it can be useful for future use cases.

The data structures for each domain are listed as an overview in Table 3.

Table 3.

EPC details mapped to the modelled data structure.

For our particular use case, the EPC rating prediction, the following listed properties (Table 4) were used in our prediction algorithm:

Table 4.

Dwelling properties used for estimating the energy performance rating.

Our machine-readable data structure can be used for data exchange purposes and other use cases and applications. Some certificates offer recommendations for dwelling improvements. Our data structure can be easily extended to cover this topic as well.

For the data import, some technical users are needed (one user per country/-database). During the import process, these users have written access, each user to its designated database. When the import has finished, all technical users receive read-only access for the further process (e.g., prediction calculation). They have no permission for CRUD operations on the database and cannot alter the permission matrix. The credentials for the technical users are available in cleartext in the applications’ source code. Since the imported data is open data, the credentials’ visibility is not considered a security issue.

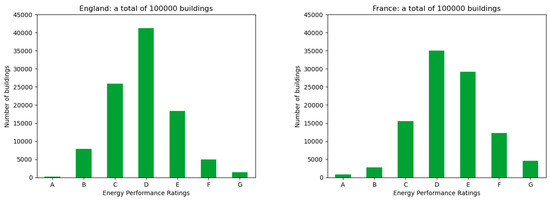

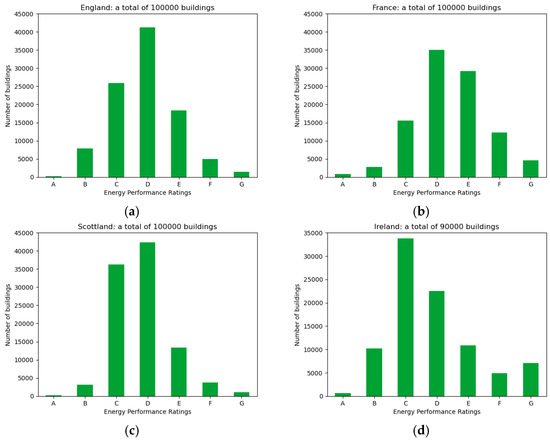

The small number of dwellings in the A, F and G groups raises the question of having too many labels in use. Since the A rating label is a goal to which the building sector aims, this rating needs to be kept. However, by putting labels F and G together as F, the latter label G could be dropped and in time even the F rating label. Judging by the clustering methods and frequency plot results, 5 labels are best. Moreover, it might make things even easier for the assessors of buildings, since the rating E, F and G are in the same “underperforming” category, and the European Union aims at enabling building renovations to achieve the best rating, A. Figure 3 below depicts idea of decreasing the number of clusters would have also come into the mind by analyzing the frequency plots below.

Figure 3.

Distribution plots for England and France.

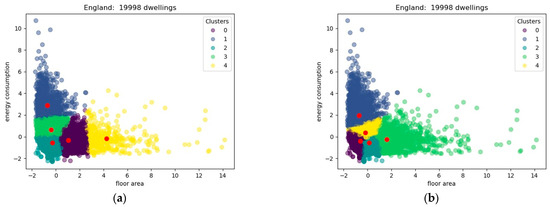

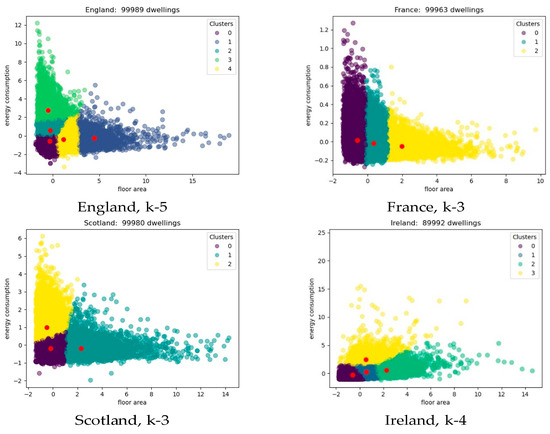

Further use of k-means is the visualization of clusters. Two preprocessing steps are conducted to improve the clustering. The first step is scaling the values to standardise the range. This is useful, especially in a situation like ours, where the values are measured in a different unit of measure (floor area: m2; energy consumption: kVh/m2). As a result, the values for floor area and energy consumption are scaled values. An example of actual and scaled values is presented in Table 5 below.

Table 5.

Actual versus scaled values.

The second pre-processing step is removing the outliers that influence the clustering algorithms. We removed the outliers in three steps: first, we plotted the clusters with all input data; secondly, we identified and removed the outliers from the input set; finally, we plotted the clusters again, only this time with the reduced input set. The clustering result is presented in (Figure 4a), where each cluster has a different colour, and the cluster centres are marked with red. Similar results can be obtained with the k-medoids method (Figure 4b). However, the k-medoids algorithm requires more computing memory than k-means, which resulted in reducing the input data considerably (only 19,998 dwellings in comparison to 100,000 dwellings used for other metrics and plots presented in this work).

Figure 4.

(a,b): Clustering methods for England (k = 5).

The effectiveness metrics of our algorithm for England are displayed in Table 6 where Rating Label D indicates highest F1-score and support values. This also indicates that predicted classes for rating Label D is highest in confusion matrix for England as depicted in Table 7.

Table 6.

Effectiveness metrics for England.

Table 7.

Confusion matrix for England.

Accuracy: How often is the prediction correct? 67% of the time.

Precision: How many data points are correctly predicted, out of all the predicted labels of a given class? Out of the times A was predicted, the algorithm was correct 80% of the time.

Recall: How many data points are correctly predicted, out of all the instances with the given label? Out of the data points with label A, 29% were correctly predicted.

F1-score: Combines the precision and recall into one measure

((2∗Precision∗Recall)).

Support: How many correctly labelled instances are in the class.

Since the prediction calculations consume quite some computing resources, not the whole database could be used as a base for the predictions. Nevertheless, the number of classified database entries were enough for a decent prediction. An overview of the number of imported entries versus the classified entries is displayed in Table 8.

Table 8.

Imported versus analysed entries.

The property mappings used in our annotated examples are listed in Table 9. The energy performance certificate properties, which did not find a correspondence in the schema.org vocabulary, are annotated as “additionalProperty” (marked with blue in Table 9) and are defined with the schema.org type “PropertyValue”.

Table 9.

EPC properties as schema.org classes.

The resulting annotated data represents an energy performance certificate model, presented as linked data in JSON-LD format. The annotated data can be used, among other uses, as rich content in websites for search engine optimisation. The validation was conducted with online tools such as JSON- LD Playgroundl2 and Google Rich Results Testl2l. These tools validated the example annotated with the Review type (however, not the example with the CreativeWork, due to issues for the type “AggregateRating”). This is fine since our model does not match conceptually to the currently available schema.org types.

The second approach was to format the EPC data with the open data standard HPXML. This standard leverages the exchange of energy performance data on buildings and appliances. The HPXML Data Dictionary comprises the concepts and constraints of building properties. A mapping of EPC properties to HPXML concepts [23] is presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

EPC properties as HPXML terms.

There are some EPC properties that were not matched to concepts of the PXL Data Dictionary, such as purpose, used methodology and carbonFootprint. The class Green-BuildingVerification is not a perfect match for our use case. Our EPC model is not restrictive on a specific certification type, and Green Building Certifications are a subtype of certifications.

5. Results

For the human user, the most interesting part and the main goal of the application is the rating prediction.From the perspective of the data analysis and prediction, the following results are of interest:

- the rating distributions of the datasets,

- the similarity scores of k-means and k-medoids, and

- the accuracy of the prediction algorithm kNN.

The frequency plots or distribution plots represent the number of dwellings assigned for a specific label. According to the plots displayed in Figure 5, most dwellings are rated as C or D in England, Scotland and Ireland; and D or E in France. The least of the dwellings are rated with label A. This fact supports the demand of the European Union to improve the energy performance of buildings.

Figure 5.

Distribution plots for each country. (a) England. (b) France. (c) Scotland. (d) Ireland.

Next, we observed the k-means and k-medoids and at the metrics elbow plot, Silhouette Coefficient and Calinski-Harabasz Score. These metrics are used to compute the optimal number of clusters. The theoretical details are presented in Section 3. Below, we looked at the results for all the four countries, presented in Table 11 and in Figure 5:

Table 11.

Cluster fitness score for countries.

We used these results for the optimal number of clusters as a basis for the discussion if the currently valid number of rating labels (a total of seven) was longer feasible.

Reducing the rating labels to k = 3, values (A, B, C), is extreme from the practical view of the EPC rating schemes and is not usable in the real world, but according to the data analysis, this small number of labels would also be fine.

The number of rating labels of k = 5 could work in the real world, having rating levels from A to E, by dropping F and G, or in other works by creating a new label E+ that comprises the old E, F and G ratings. This approach could make the EPCs easier to understand by the end user. Additionally, the assessor would not have to distinguish between E, F and G dwellings by fine-tuning their calculations for this category of dwellings, since this type of building is underperforming. For this category of building, a clear need for an energy performance upgrade is needed. If this endeavour is estimated to be too costly, demolition can be considered. However, this is for the owners of the buildings to decide. Here we try to present the idea of making the EPC rating schemes easier, by reducing the number of rating levels from seven to five. This approach aligns with the European Union’s endeavour to push the energy efficiency of buildings towards the best performing rating level A.

In the next figures and tables, we display the computed optimum number of clusters k for each country:

- England, optimum k ∈ {3, 5};

- France, optimum k ∈ {3, 4};

- Scotland, optimum k ∈ {4, 5}; and

- Ireland, optimum k ∈ {3, 4}.

Using the feasible number of clusters for each country, we visualised the clusters for the k-means clustering method (Figure 6). Since k-means is sensitive to outliers, as an optimization step, we removed some outliers from the dataset before applying the k-means algorithm. Each cluster is presented with a different colour, whereas the cluster centres are marked with red.

Figure 6.

k-means clusters for each country.

We skipped the k-medoids plot generation for each country due to computing memory issues.

The machine learning algorithm that finally led us to a result is the kNN classification method. The energy performance rating was predicted based on the input data: floor area and energy consumption. As a piece of additional information, five of the most similar dwellings were also computed. The similarity was based on two criteria, floor area and energy consumption.

Lastly, we present the prediction algorithms’ accuracy metrics for each country in the below in Table 12:

Table 12.

Effectiveness metrics for the prediction algorithm across countries.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

By using the near-zero energy building concept, we can lower energy consumption.

Smart energy devices are not yet clever enough to address building context or personal motivations. Nevertheless, the comfort of users should not be compromised in the desire to lower the carbon footprint of buildings [13,26].

This work aimed at providing a solution for reducing the demand for primary energy (heating, domestic hot water, and electric energy consumption) by offering a self-assessment tool for building tenants. This tool offers an approximation of the EPC rating of a dwelling, based on two properties: floor area and energy consumption. The prediction tool does not replace an EPC rating scheme or an energy performance certificate; it informs the users before they dive into a possibly costly certification. Simultaneously, the self-assessment tool can sensitize the users regarding their energy consumption. It can trigger thoughts about the renovation of their dwellings and enable tenants to lower their carbon footprint.

With regards to future work, the following ideas and use cases can be considered:

- More state-of-art similarity metrics and clustering algorithms can be researched and incorporated based on suitability with regard to available data.

- Semantic models for energy performance certificates (EPC) can be further integrated with semantic tools, which can help in reconciliation and alignment with cross domain semantic models. These tools can then be used for applying reasoning on EPC data.

- A tool for automated annotation of EPC data based on a newly developed ontology can be implemented further.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P., A.F. and A.P.R.G.; methodology, A.P. and A.F.; formal analysis, A.P.; investigation, A.P. and A.F.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.; writing—review and editing, A.P., G.J., A.F. and A.P.R.G.; visualisation, A.P.; supervision, A.F.; project administration, A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

UMU-CAMPUS LIVING LAB EQC2019-006176-P funded by ERDF funds, Horizon 2020 Project PHOENIX (grant number 893079) and project ONOFRE of the Ministry of Science and Innovation of the Government of Spain, with code: PID2020-112675RB-C44.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- European Commission. Energy Efficiency Plan 2011. 2011. Available online: https://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2011:0109:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Directive (EU) 2018/844 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 amending Directive 2010/31/EU on the Energy Performance of Buildings and Directive 2012/27/EU on Energy Efficiency. 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2018.156.01.0075.01.ENG (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Fensel, A.; Tomic, S. SESAME: Semantic Smart Metering–Enablers for Energy Efficiency. In Proceedings of the Poster and Demonstration Track at the 2nd Future Internet Symposium (FIS 2009), Berlin, Germany, 1–3 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Directive 2012/27/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 on Energy Efficiency, Amending Directives 2009/125/EC and 2010/30/EU and Repealing Directives 2004/8/EC and 2006/32/EC. 2012. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1399375464230&uri=CELEX:32012L0027 (accessed on 15 April 2019).

- Lanner Electronics Inc. 5 Ways the Internet of Things Could Help Combat Climate Change. 2018. Available online: https://www.lanner-america.com/blog/5-ways-internet-things-help-combat-climate-change (accessed on 25 May 2019).

- City of Innsbruck. Active Innsbruck-City Projects. 2018. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=LaTeX&oldid=413720397 (accessed on 25 May 2019).

- The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2020/2155 of 14 October 2020 Supplementing Directive (EU) 2010/31/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council by Establishing an Optional Common European Union Scheme for Rating the Smart Readiness of Buildings. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32020R2155&qid=1619285483046 (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Verbeke, S.; Waide, P.; Bettgenhäuser, K.; Uslar, M.; Bogaert, S. Support for Setting up a Smart Readiness Indicator or Buildings and Related Impact Assessment. August 2018. Available online: https://www.buildup.eu/sites/default/files/content/sri_1st_technical_study_-_executive_summary.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2020).

- Tomic, S.D.K.; Fensel, A.; Schwanzer, M.; Veljovic, M.; Stefanovic, M. Semantics for energy efficiency in smart home environments. In Applied Semantic Web Technologies; Auerbach Publications: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; pp. 429–454. [Google Scholar]

- Fotopoulou, E.; Zafeiropoulos, A.; Terroso-Saenz, F.; Simsek, U.; Vidal, A.G.; Tsiolis, G.; Gouvas, P.; Liapis, P.; Fensel, A.; Skarmeta, A. Providing personalized energy management and awareness services for energy efficiency in smart buildings. Sensors 2017, 17, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Calinski-Harabasz Score Calculation (Scikitlearn Module). 2019. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.metrics.calinski_ (accessed on 22 October 2019).

- Drools is a Business Rules Management System (BRMS). Available online: https://www.drools.org/ (accessed on 19 November 2019).

- Vidal, A.G.; Ramallo-Gonzalez, A.P.; Terroso-Saenz, F.; Skarmeta, A. Data driven modeling for energy consumption prediction in smart buildings. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Boston, MA, USA, 11–14 December 2017; pp. 4562–4569. [Google Scholar]

- Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Innovate UK. Building Performance Evaluation Programme: Findings From Non-Domestic Projects-Getting the Best From. January 2016. Available online: https://www.ukri.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/IUK-061221-NonDomesticBuildingPerformanceFullReport2016.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2019).

- IPEEC’s Building Energy Efficiency Task group (BEET). Building Energy Rating Schemes, Assessing Issues and Impacts. 2014. Available online: https://www.buildingrating.org/sites/default/files/1402403078IPEEC_BuildingEnergyRatingSchemesFinal_February2014_pdf.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2019).

- Fabi, V.; Andersen, R.; Corgnati, S.; Olesen, B.; Filippi, M. Description of Occupant Behaviour in Building Energy Simulation: State-of-Art and Concepts for Their Improvement. Building Simulation 2011, At Sydney, Australia, 11 2011. Building Information Modeling—Die neue Dimension der Planung. Available online: https://www.knauf.at/qr/bim.html (accessed on 18 November 2019).

- Transient System Simulation Tool (Features and Demonstration). Available online: http://trnsys.com (accessed on 25 May 2019).

- Ramallo-Gonzalez, A.; Blight, T.; Coley, D. Robust low energy design that accounts for occupant behavior. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Building Sustainability Assessment, Porto, Portugal, 23–25 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- de Vilde, P.; Jones, R.V.; Fuertes, A. The Gap between Simulated and Measured Energy Performance: A Case Study across Six Identical New-Build Flats in the UK. 2015. Available online: https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk/handle/10026.1/4320 (accessed on 9 October 2019).

- Imam, S.; Coley, D.; Valker, I. The building performance gap: Are modellers literate? Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2017, 38, 014362441668464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thermal Energy System Specialists. Trnsys 18, a Transient System Simulation Program. 2018. Available online: https://sel.me.wisc.edu/trnsys/features/trnsys18_0_updates.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2019).

- IEA. Energy Performance Certification of Buildings, a Policy Tool to Improve Energy Efficiency. 2010. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/policy-pathway-energy-performance-certification-of-buildings (accessed on 31 May 2019).

- Schwanzer, M.; Fensel, A. Energy consumption information services for smart home inhabitants. In Proceedings of the Future Internet—FIS 2010—Third Future Internet Symposium, Berlin, Germany, 20–22 September 2010; pp. 78–87. [Google Scholar]

- Mogles, N.; Valker, I.; Ramallo-Gonzalez, A.P.; Lee, J.; Natarajan, S.; Padget, J.; Gabe-Thomas, E.; Lovett, T.; Ren, G.; Hyniewska, S.; et al. How smart do smart meters need to be? Build. Env. 2017, 125, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzinger, T.; Osterreicher, D. Supporting the Smart Readiness Indicator: A Methodology to Integrate A Quantitative Assessment of the Load Shifting Potential of Smart Buildings. Energies 2019, 12, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neymark, J.; Roberts, D. Deep in Data: Empirical Data Based Software Accuracy Testing Using the Building America Field Data Repository. 2013. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy13osti/58893.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2019).

- Home Performance Coalition. HPXML Specifications. 2019. Available online: https://www.hpxmlonline.com/specifications/ (accessed on 22 October 2019).

- Ramallo-Gonzalez, A. Modelling Sirnulation and Optimisation of Low-Energy Building. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Exeter, Stocker, UK, April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky, M.; Sacks, R.; Brilakis, I. Semantic Enrichment for Building Information Modeling. Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering 2016, 31, 261274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, R.; Ma, L.; Yosef, R.; Borrmann, A.; Daum, S.; Kattel, U. Semantic Enrichment for Building Information Modeling: Procedure for Compiling Inference Rules and Operators for Complex Geometry. 2017. Available online: https://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/32807/1/Ling.Ma.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- Patroumpas, K.; Giannopoulos, G.; Athanasiou, S. Towards geospatial semantic data management: Strengths, weaknesses, and challenges ahead. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSPATIAL International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, Dallas/Fort Worth, TX, USA, 4–7 November 2014; pp. 301–310. [Google Scholar]

- The Association for Environment Conscious Building (AECB). 2016. Available online: https://www.aecb.net/about/about-the-aecb/aecb-history (accessed on 9 July 2019).

- Spatio-Temporal Query Language for Verifying and Analyzing 4D Building Information Models. Available online: https://www.cms.bgu.tum.de/en/research/17-research-projects/121-spatio-temporal-query-language-for-verifying-and-analyzing-4d-building-information-models (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- Cohn, A.G.; Hazarika, S.M. Qualitative spatial representation and reasoning: An overview. Fundam. Inform. 2001, 46, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).